#Indian Emperor

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

On Dryden's "Indian" Plays

November is Native American History Month; next year (2025) will mark the 350th anniversary of King Phillip’s War, the beginning of the end for the native people as the dominant polity on this continent. I’m marking the occasion with a series of daily posts related to the history of the Native Americans and their interactions with encroaching Europeans. Some will have to do with pop culture;…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

insect drawings inspired by artists 1/2: Vincent Van Gogh (emperor caterpillar) and Mary Blair (indian lily moth) 🐛🦋

#my art#study#art studies#art style study#style study#vincent van gogh inspired#moth#caterpillar#emperor caterpillar#indian lily moth#art#insect#insect art#entomology#bug#bug art

159 notes

·

View notes

Text

{Amor Omnia Vincit-Lucius Verus Aurelius}

Chapter 2-Omnes viae Romam ducunt: All roads lead to Rome

SUMMARY: Tillotama's strenght is forced upon her by her aunt, she is tired but dares not to show it, yet her mother seems to see right through the cracks of Tillo's resolve. Geta and Caracalla are awaiting their gift while Macrinus makes sure that a quarrel will happen either way between the brothers.

PAIRING: Lucius Verus Aurelius x South Indian OC

WORD COUNT: 5,5K

WARNINGS: bit of mistreatment, Tillo debuted to young as a dancer

The horizon shifted, the vast expanse of blue turning into a dimming canvas as the first outlines of the Roman coast appeared on the distant edge of the world. Jagged cliffs and rocky promontories emerged from the darkening sky, their shapes unfamiliar, their presence both imposing and distant. The winds carried a new scent—earthy and strange, tinged with the salt of the sea but also something sharper, a promise of the unknown. For those aboard the fleet, it was a moment pregnant with anticipation and unspoken fear.

In her cabin, Tillotama stood still by the narrow window, her golden-blue eyes locked on the land that had grown nearer with each passing moment.The only thing she felt was a gnawing unease, a tightening in her chest that felt too tight for breathing.

Her fingers tightened around the edge of the wooden frame, the faint creak of her grip the only sound in the room. She held on as though the ship might carry her away from the land, away from the future waiting for her on those foreign shores.

A soft knock at the door pulled her from her thoughts. Rambha stepped inside, her face composed but her eyes betraying the concern she couldn’t hide. Despite the calm exterior, her sister carried a storm of emotions just beneath the surface—just like Tillotama.

“They say we’ll reach the harbor by morning,” Rambha said quietly, stepping inside, her hands clasped tightly in front of her. Her voice was soft, but the tension in it was unmistakable. She hesitated before moving closer, her presence grounding. “Are you ready?”

Tillotama didn’t turn from the window. Her voice was low, distant, as if the land before her could somehow absorb her words. “Ready?” She repeated, her lips curling into a bitter half-smile. “I don’t think I’ve ever been ready for anything they’ve demanded of me.”

Rambha stepped forward, her hand resting gently on Tillotama’s shoulder. The warmth of it anchored Tillotama, but it also reminded her of the weight she carried—how everything had always been her responsibility. The weight of her people, the weight of their expectations.

“You’ve always found a way, Tillo,” Rambha said softly, her voice thick with conviction. “You’re stronger than they think.”

Tillotama exhaled a sharp, bitter laugh. “Strength? Do you know what strength has brought me, Rambha?” She spoke without turning to face her sister, her gaze still locked on the horizon. “It’s made me a jewel for their amusement. A prize for them to play with. A symbol they can parade around. Strength... it’s never felt like strength to me.”

Rambha’s hand tightened on her shoulder, her voice unwavering. “Strength brought you here, yes. But it will carry you through this. You’re not just walking into their world as some victim. You’re Tillotama. The woman who can turn kings into poets, soldiers into dreamers. They will see that. They will see you.”

Tillotama turned then, her expression softening, but her heart still heavy. She searched her sister’s face, the fierce determination that never wavered in her words a balm to the storm inside her. “And yet…” she murmured, a shadow passing across her gaze, “I wonder if they’ll see anything more than a prize. Something to conquer. Something to own.”

Rambha stepped closer, her voice low but firm, a promise wrapped in every syllable. “They might not see it. But that’s their blindness, not yours. If they see a jewel, then blind them with your brilliance. If they see a prize, then make them pay for it in ways they can’t even imagine.”

Tillotama studied her sister, feeling the storm inside her calm just slightly. She reached for the steady presence of Rambha’s words, though she didn’t entirely believe them. “You make it sound so simple,” she said, a faint smile tugging at the corner of her lips.

“It’s not simple,” Rambha replied, a quiet fire in her eyes. “But nothing about you ever has been.”

Before Tillotama could respond, the door opened again, and Ezhili entered, her small frame hesitant in the doorway. She darted her eyes between her two sisters, sensing the tension hanging like a cloud between them. “The captain sent me,” she said, her voice quivering with nervousness. “He says… he says we’ll need to prepare. The Romans will send representatives to meet us at the harbor.”

Rambha nodded sharply, her posture straightening as she absorbed the news. “Then we should be ready. The Romans will expect perfection.”

“They always do,” Tillotama muttered, her smile fading as she turned her gaze back to the window. The coast was much closer now, the details of the land sharpening in the dimming light. The Roman capital was just beyond the horizon, a place filled with both wonder and peril, a place that promised to change everything.

Ezhili stepped forward, her small hands trembling as they gripped Tillotama’s. “I’m scared,” she confessed, her voice breaking, barely a whisper in the heavy air. “What if they’re cruel? What if... what if we can’t go home? What if this is forever?”

Tillotama pulled her close into an embrace. The feel of Ezhili’s delicate frame against her own made her chest tighten, the protective instincts she had always carried rising to the surface. “We won’t go home,” she said softly, but with certainty. “Not in the way we knew it. But listen to me, Ezhili, whatever happens, we’ll endure. We’ve survived worse, haven’t we?”

Ezhili’s body shuddered as she nodded, her cheek resting against Tillotama’s shoulder. “Yes…” she whispered. “But this... this feels different.”

“It is different,” Tillotama admitted, her voice steady despite the turmoil inside her. “But we’re different, too. Stronger. And no matter what they see when they look at us, we know the truth. We know who we are. And no one can take that from us.”

The three sisters stood in silence for a moment, the weight of the journey pressing on them, the weight of everything that was to come. Then, after a long pause, Rambha stood, her voice resolute as she spoke, more to herself than to the others. “We’ll show them,” she said, the fire of determination rekindled in her eyes. “We’ll make them see us for who we truly are.”

Tillotama stood, her chin lifting slightly, her shoulders square with resolve. “If they want a spectacle, then that’s what they’ll get. But on our terms. Not theirs.”

As the ship swayed gently in the sea’s rhythm, and the Roman coast drew nearer, the sisters began their preparations. Tillotama’s jewels glinted in the soft light of the cabin’s lamp, each one fastened carefully into her hair. Her sari shimmered like flames against her skin, every fold and pleat an intricate work of art, meticulously woven to capture the light. Beneath the layers of opulence, though, there was something much more powerful—a quiet, unyielding strength that could not be seen, but could always be felt.

The harbor was close now, the outlines of Roman soldiers and dignitaries barely visible in the gathering dusk, their presence a reminder of the spectacle that awaited them. Tillotama’s heart beat steadily, each thud matching the rhythm of the ship, her resolve growing with each passing moment.

She whispered to herself, her voice barely audible in the quiet cabin. “I’ll meet their stares,” she said, her voice firm and clear. “And I’ll make them remember my name.”

As the ship surged toward its final destination, the first step into a world she could never undo, Tillotama stood with her sisters, her heart a mixture of fear and fierce pride. She would not break. Not for them. Not for anyone.

Whatever came next, she would face it—head held high, eyes unflinching—and she would make them see her for what she was. She was no mere prize to be claimed. She was Tillotama. And they would remember her name.

ROME:

The Roman night cloaked the imperial chambers in a soft, restless silence, broken only by the faint crackle of oil lamps and the occasional murmur of waves against the distant harbor. The golden light from the lamps carved sharp contrasts in the opulent room, painting shadows that flickered over the intricate mosaics and marble columns.

Geta reclined in his chair with practiced indolence, his goblet dangling loosely from his fingers. The elder son of Severus had the air of a man who had already seen too much, his sarcasm as finely honed as a gladiator’s blade. Across from him, Caracalla paced like a restless lion, his youthful energy bouncing off the walls. His expressions shifted rapidly, irritation giving way to excitement, then to frustration, all with the volatility of a summer storm.

Macrinus, standing near the window, was the calm eye of that storm. The former slave turned master of Rome’s gladiatorial stables, his demeanor was as smooth as the polished marble floors, his sharp gaze like a predator’s assessing its prey. He watched the brothers with faint amusement, his expression unreadable save for the glint of cunning in his eyes.

“So,” Geta drawled, swirling the wine in his goblet, “the famed jewel of the East arrives tomorrow. I wonder if she sparkles in the dark or only in the light of her own myth.”

Caracalla stopped pacing, throwing his brother a glare. “You’re insufferable, you know that? the messenger said she’s a gift of unmatched value. Do you have to sneer at everything?”

“Oh, forgive me,” Geta replied, leaning forward and resting his chin on his hand, his voice dripping with mock sincerity. “How thoughtless of me to question the virtue of parading a woman halfway across the world to entertain the mighty Caesars. Truly, an act of benevolence.”

Caracalla’s jaw tightened, and he rounded on Macrinus. “Say something to him, Macrinus! He’s always like this.”

Macrinus’s lips curved into a slow, measured smile, his voice low and deliberate. “And why should I? Your brother has a point, young Caesar.” He stepped away from the window, his hands clasped loosely behind his back. “A woman of her caliber—if we’re to believe the tales—is no mere gift. She’s a weapon, a message, a game piece placed on the board. The real question is, who’s playing, and who’s being played?”

Caracalla frowned, his brow furrowing as he considered Macrinus’s words. “What are you saying?”

“I’m saying, my dear Caracalla,” Macrinus replied, his tone sharpening just enough to slice through the younger man’s confusion, “that gifts like this are rarely free. She’s been trained, molded, and sent here for a reason. The East doesn’t part with its treasures lightly.”

“She’s a woman, not a chessboard,” Caracalla retorted, his irritation flaring. “You speak as if she’s nothing but a pawn.”

“A pawn can become a queen, if moved correctly,” Macrinus countered, his eyes narrowing slightly. “And courtesans, my Caesars, are far more dangerous than pawns. Never forget that.”

Geta smirked, raising his goblet in a mocking toast. “Ah, the wisdom of Macrinus, ever the voice of doom and intrigue. Tell me, does everything come with a conspiracy in your world, or do you occasionally allow for simple pleasures?”

Macrinus tilted his head, his smile growing bolder. “Pleasures are never simple when you rule an empire, Geta. And if you think otherwise, perhaps it’s best that your younger brother is the one who takes the lead.”

The air in the room shifted, a sudden tension sparking between the three men. Caracalla, ever the hothead, stepped forward, his voice rising. “What’s that supposed to mean?”

“Nothing you’re ready to hear,” Macrinus replied smoothly, his tone just shy of condescending. “But enough of this. You’ll both meet her tomorrow, and the truth will reveal itself soon enough. The question is, are either of you clever enough to see it?”

Geta chuckled darkly, leaning back in his chair. “Cleverness isn’t the issue. It’s whether she’s worth the effort of playing along. If she’s just another pretty face with a knack for flattery, well…” He shrugged. “We’ve seen a thousand like her before.”

Caracalla’s fists clenched, but he stayed silent, his thoughts clearly racing. Macrinus watched him with quiet satisfaction, his words having planted seeds of doubt and ambition in equal measure.

“Sleep on it, young Caesars,” Macrinus said, turning toward the door. “Tomorrow will come soon enough, and with it, your answers. Or your undoing.” He left the room with a faint bow, the sound of his footsteps fading into the hall. Geta and Caracalla were left in a silence heavy with unspoken thoughts. Finally, Geta sighed, lifting his goblet in another lazy toast.

“To tomorrow,” he murmured, his tone tinged with resignation and irony. “May the goddess of the East live up to her legend.” Caracalla didn’t respond, his eyes fixed on the doorway through which Macrinus had disappeared. The young emperor’s mind churned, torn between the innocence of his youthful excitement and the darker, more dangerous currents stirred by his companions’ words.

Outside, the night deepened, and the harbor winds carried whispers of what was to come.

The Roman harbor gleamed under the moon’s pale light, a mirage of flickering lanterns and distant voices blending into the gentle lap of waves against the ship. In the cabin, the faint scent of sandalwood mingled with the salt air, the golden glow of a single lamp casting its light over silken cushions and the polished brass mirror. Tillotama sat in its reflection, her golden-blue eyes shadowed by thoughts too deep for words.

The adornments she wore—a cascade of glittering stars around her neck, earrings that swayed like bells with every movement—felt heavier than usual. The sari, its folds perfect and intricate, hugged her like a second skin, a layer she couldn’t shed. She tilted her head slightly, catching her own gaze in the mirror. How many others had gazed upon her this way, searching for a glimpse of something divine in her human frame? They all called her the Nagarvadhu, the goddess of arts, but tonight she felt far removed from anything celestial.

A soft knock came at the door. Tillotama’s lips curved into the barest semblance of a smile—she already knew who it was.

“Come in, Ammi,” she said, her voice soft but steady.

Amrapali entered, her movements graceful, the muted colors of her sari a stark contrast to her daughter’s radiance. She closed the door with a quiet click and approached Tillotama, her eyes taking in every detail of her daughter’s posture, the subtle tightness of her shoulders, the way her hands rested just a touch too stiffly on her lap.

“You’ve been staring at yourself for too long,” Amrapali said gently, sitting beside her. “You’ll find no answers in the mirror tonight.”

Tillotama let out a small, weary laugh, leaning back against the cushions. “Maybe not answers. But at least the mirror doesn’t talk back.”

Amrapali chuckled softly, reaching out to adjust the pallu of Tillotama’s sari. Her touch was gentle, familiar, the kind that soothed wounds deeper than the skin. “No, but it also doesn’t know you the way I do. What’s troubling you, Tillo?”

Tillotama hesitated, her gaze dropping to the intricate embroidery on her lap. “Do you ever wonder, Ammi, what it might have been like if… if things had been different? If I hadn’t been… chosen?”

Amrapali’s hand paused, but only for a moment. “You were not chosen, Tillo. You were born to this.” She brushed a strand of hair from her daughter’s face, her fingers lingering. “You became the Nagarvadhu because no one else could have been. You’ve carried it all so beautifully, even when you were a child.”

Tillotama’s lips tightened, and she looked away. “A child,” she murmured. “I was thirteen when they first called me that. Do you remember? The day they said I was to represent the arts, the soul of our kingdom, the pride of our people. They put me on a pedestal so high I could barely breathe.” She met her mother’s gaze again, her voice softening. “Did I ever have a choice, Ammi? Or was I always meant to be a symbol instead of myself?”

Amrapali’s eyes glistened with unshed tears, but she didn’t look away. “It was never fair,” she said quietly. “But you took what could have crushed you and turned it into something unbreakable. That is your strength, Tillo. Not the title. Not the admiration. You.”

Tillotama swallowed, her chest tightening. “Strength,” she echoed. “Sometimes it feels more like endurance. Like survival.”

“And what is survival if not the foundation of strength?” Amrapali countered gently. “You have given so much of yourself, I know. But you are not just what they see. You are my daughter, my Tillo. And no matter how heavy the world feels, you are never alone in carrying it.”

Tillotama exhaled shakily, her hand finding her mother’s and squeezing it tightly. For a moment, the silence between them was warm, comforting, and the storm inside her began to quiet.

Then came a sharp, deliberate knock on the door, breaking the stillness like a snapped thread. Tillotama tensed, her fingers slipping from her mother’s as she straightened her back.

“Enter,” she said, her voice cool and composed once more.

The door opened to reveal Korravai, her figure framed in the lamplight like an imposing sentinel. Her presence filled the room, the air thickening as she strode inside, her dark eyes sharp and assessing.

“Amrapali,” Korravai said curtly, nodding to her sister. “Leave us.”

Amrapali rose slowly, smoothing her sari with calm deliberation. She glanced at Tillotama, her gaze lingering with unspoken reassurance. “Do not let her harden you, Tillo,” she murmured before walking past Korravai, her steps unhurried despite the tension.

Once the door closed behind her, Korravai turned to Tillotama, her eyes narrowing as she approached. “You’re restless,” she said bluntly. “Good. You should be.”

Tillotama met her aunt’s gaze with quiet defiance. “And why is that, Korravai? Because the Romans expect to see perfection? Or because you do?”

“Both,” Korravai replied without hesitation. “You bear the weight of your title, Tillotama. The Romans will look at you and see not a woman, but a symbol. They will test you. Probe for weakness. And if they find even the slightest crack, they will exploit it.”

Tillotama stood, her movements slow and deliberate, her golden-blue eyes blazing as she stepped closer to her aunt. “I know what they expect. I’ve lived my entire life under the gaze of expectations. Do you think I’ve forgotten what it means to stand in the light of scrutiny?”

Korravai’s expression softened, though her voice remained firm. “No. But the stakes are higher now. This is not your court, where admiration comes easily. These are the Romans—calculating, ruthless. You must not simply meet their expectations. You must exceed them.”

Tillotama’s jaw tightened, but she nodded. “And if I do? If I surpass even their understanding, what then?”

“Then,” Korravai said, a rare hint of a smile touching her lips, “you will become something they cannot conquer. Something they cannot forget.”

The words hung in the air like a challenge, and Tillotama felt the weight of them settle over her like a mantle. Her gaze didn’t waver, her voice steady as she replied, “I will not falter. Not before them. Not before anyone.” Korravai inclined her head, satisfaction flickering in her dark eyes.

“Good. Because you are not just a courtesan. You are our weapon. And the world will kneel before you, whether it knows it or not.”

With that, she turned and left, the sound of her footsteps fading into the night. Tillotama stood in the silence, her reflection catching her eye in the brass mirror once more. But now, her gaze was sharper, her resolve unshakable.

“I am not their weapon,” she whispered to herself, her voice firm. “I am my own.”

The morning sun painted the horizon in hues of amber and rose as Tillotama’s fleet came to rest at the shores of Rome. The grand city, with its towering structures and sprawling streets, lay just beyond the calm waters. But within the stillness of her cabin, Tillotama knelt in quiet prayer before a small idol of Krishna. The figure, carved from sandalwood and adorned with delicate golden accents, radiated a sense of serenity that mirrored her own.

Her hands were clasped together, her slender fingers adorned with rings that caught the flickering light of a nearby oil lamp. Words of devotion spilled silently from her lips as she sought strength for the challenges that awaited her. The creak of the ship’s timbers and the rhythmic lapping of waves were the only sounds accompanying her—until a sudden knock broke the peace.

Before she could respond, the door swung open, and Chanchal entered with her usual exuberance. Her long braid swung over her shoulder as she hurried toward Tillotama, her youthful energy filling the room. “Oh, Tillo!” she exclaimed, throwing her arms around her mistress in a warm embrace. “It feels as if we haven’t seen you in years.”

Without opening her eyes, Tillotama chuckled softly, still focused on her prayer. “It has only been three days, Chanchal,” she replied, her tone teasing. “Besides, you all knew she wouldn’t let you attend to me so close to Rome. Didn’t she say I must focus only on my ‘perfection’?”

Chanchal huffed, pulling back but staying close. “That she of hers thinks far too highly of herself.”

Kinjal entered next, moving with a quiet elegance that contrasted Chanchal’s lively demeanor. She took a seat on the edge of a wooden bench, crossing her legs with practiced ease. “Perfection? Please,” she said, her voice dripping with sarcasm. “She’s not so perfect herself. Just yesterday, I caught her spilling wine on her robe and blaming the wind. The wind!”

Tillotama smiled softly, finishing her prayer with one last whispered phrase. Rising gracefully, she turned to her companions, her crimson sari cascading like liquid fire around her. “Someone has to be perfect,” she said, the faintest hint of mischief in her voice.

Mataangi leaned against the doorframe, arms crossed, her sharp features betraying her disdain. “If she wants perfection so badly, maybe she should train herself and leave you be. Horrendous woman,” she muttered, earning a stifled laugh from Chanchal.

“Enough,” Tillotama said gently, though the authority in her voice was unmistakable. She approached Mataangi, resting a hand on her shoulder. “She means well, in her own way.”

“Does she?” Kinjal muttered, drawing a sidelong glance from Chanchal, who nudged her sharply.

Bulbul, the quietest of the group, had been watching Tillotama with a tender expression. She stepped forward, her dark eyes soft with concern. “Are you ready, love?” she asked, her voice barely above a whisper.

Tillotama hesitated for a moment, her gaze shifting to the small window. The grandeur of Rome lay just beyond, a world of power, expectation, and danger. Was she ready? The question lingered in the air, heavy with unspoken fears. Finally, she turned back to Bulbul, her golden-blue eyes resolute. “I am,” she said firmly. “We all must be.”

Chanchal reached for her hand again, squeezing it tightly. “Do you have to be?” she asked, her voice quieter now. “Why must it always be you, Tillo?”

“I’m not alone,” Tillotama replied softly, her gaze moving across the faces of her four companions. “I have you. And that is more than most can say.”

Kinjal frowned, folding her arms. “Then let us do more. Let us speak for you, fight for you. You’re not some goddess meant to carry the world on your shoulders.”

“And yet here I am,” Tillotama said with a wry smile. “Because the world doesn’t care who carries it, only that it is carried.”

Mataangi muttered something inaudible but allowed a faint smirk to cross her face. Chanchal, ever the optimist, leaned closer. “We just want you to know that we’re here,” she said, her voice brimming with sincerity. “Not for Rome, or for anyone else. For you.”

Tillotama’s expression softened, the weight of her role momentarily lifting. She reached up to brush a lock of Chanchal’s hair back into place. “And that,” she said quietly, “is why I can face whatever comes next.”

A sharp knock sounded at the door, followed by the voice of an attendant. “My lady, the Roman officials have gathered at the docks. They await your arrival.”

Tillotama drew a steadying breath, her composure returning. “Very well,” she replied, her voice calm yet commanding. She turned to her ladies-in-waiting with a faint smile. “Shall we?”

Mataangi stepped forward to adjust the drape of Tillotama’s sari, her movements precise but deliberate. “Let them wait a little longer. It’ll remind them who’s in charge.”

Bulbul chuckled softly. “Careful, Mataangi. Tillo’s already dangerous enough without you feeding her ideas.”

Tillotama laughed, the sound light and melodic. Gathering her resolve, she moved toward the door, her companions falling in step behind her. “Rome may think it has me,” she said, her voice carrying a quiet strength. “But today, the Eternal City will learn that I arrive on my own terms.”

With that, she stepped out, the air electric with anticipation, as the shores of Rome prepared to witness her arrival.

With that, she turned toward the door, her four companions falling in step behind her. The air hummed with anticipation as they made their way to the deck. There, the Roman officials awaited, their gazes trained upon the ship, eager for the arrival of the living goddess from the East.

As Tillotama stepped onto the ship’s deck, her image hidden behind the silk paravan held by Kinjal and Chanchal, the crowd’s murmurs grew louder, the tension palpable. The Romans, who had eagerly awaited her arrival, now strained their eyes, trying to catch a glimpse of the legendary beauty they had been promised.

Waarangan, the Indian ambassador, stepped forward to announce her presence, his voice booming with pride. “My lords,” he said, his tone rich with reverence, “I present to you Tillotama Vyjayanthimala Saraswati Devi, the Queen of Arts, and a loyal gift from India.”

The officials exchanged intrigued glances, but one voice rose above the rest, skeptical and laced with challenge. “How are we to know she is as eternal in beauty as the stories claim?” the official asked, unable to see beyond the silk.

Waarangan’s smile was almost imperceptible as he met the Roman official’s gaze. “My lord,” he said with a slight bow, “A beauty as holy as hers cannot be perceived by mere mortals in such surroundings. She is a vision meant for higher eyes—eyes that can see beyond the earthly veil.”

The crowd fell into a hush, the tension thick with anticipation.

The procession of Tillotama’s palanquins advanced toward the grand imperial palace, the rhythmic sway of the bearers accompanied by the soft jingle of golden ornaments adorning the palanquin’s exterior. Inside the largest of the palanquins, Tillotama sat in serene composure, her hands resting lightly on her lap. Beside her, Kinjal and Chanchal peered out through the intricately carved latticework windows, their expressions a mixture of curiosity and unease as they observed the streets of Rome bustling with life.

Kinjal wrinkled her nose slightly and muttered, “The air here feels strange. Almost... not human.”

Chanchal glanced at her, brow arched. “Not human? You think the Romans breathe something else? Perhaps ambition and arrogance.”

Tillotama chuckled softly, her voice like a faint melody amidst the steady rhythm of the palanquin. “It is not the air, Kinjal,” she said, a playful lilt in her tone. “It is the weight of a city that has spent centuries convincing itself it is the center of the world.”

“Then let us show them another kind of center,” Chanchal quipped, earning a faint smirk from Kinjal. The palanquins slowed as they arrived at the vast marble steps of the imperial palace. The imposing structure loomed ahead, its grandeur a testament to Roman authority and ambition. The crowd that had gathered along the streets fell silent, anticipation thick in the air. At the top of the palace steps stood Macrinus, the imperial foe of Geta and Caracalla, his imposing figure draped in an embroidered toga. His dark eyes scanned the procession with a calculating gaze, a faint smirk tugging at the corner of his lips.

Waarangan, stepped forward from the head of the procession, his own robes flowing elegantly as he bowed low. His movements were deliberate, each one a reflection of the respect and poise Tillotama’s court carried with them.

Macrinus’s smirk deepened, his tone a mixture of civility and thinly veiled dominance. “We welcome you to Rome,” he said, his voice carrying over the silent crowd.

Waarangan straightened, his expression calm but with a glint of knowing in his eyes. “We thank you for your gracious welcome, Lord Macrinus,” he replied in Latin, his words measured and precise. “I present to you the pride of India.”

As he turned toward the largest palanquin, his voice softened with reverence. “Tillotama,” he called, and with that single name, the crowd’s murmurs grew to an eager hum.

The bearers set the palanquin gently on the ground. Kinjal and Chanchal moved to either side of Tillotama as she prepared to step out. With practiced grace, Tillotama emerged, her figure draped in exquisite silks that shimmered in the sunlight. A translucent veil covered her face, adding an air of mystery to her ethereal presence. Her movements were fluid, her bearing regal, as though the earth itself shifted to accommodate her steps.

Macrinus descended a few steps, his gaze fixed on her. His eyes roved over her form, taking in every detail—the way her sari flowed like water, the delicate gold chains adorning her wrists, the serene poise in her posture. She was more than he had anticipated, and yet he could not discern her entirely through the veil.

He paused, his smirk returning as he addressed Waarangan. “A veil hides much, Ambassador. Perhaps too much.”

Waarangan’s response was quick, his tone smooth. “A veil hides what is sacred, my lord. And some things are only meant to be unveiled when the moment is right.”

Macrinus chuckled, a low, rumbling sound, and inclined his head slightly in acknowledgment. “Indeed, Ambassador. Rome will wait for such a moment, though it is not accustomed to waiting.”

Tillotama’s gaze remained steady behind the veil, though her silence spoke volumes. She did not need to respond; her presence alone commanded the attention of all around her. Kinjal and Chanchal flanked her like loyal sentinels, their expressions unreadable but their movements perfectly in sync with their mistress.

Macrinus stepped closer, his tone shifting to one of calculated charm. “Lady Tillotama,” he said, his words slow and deliberate, “Rome has heard much of your beauty, your grace, and your artistry. Now, it seems, we are to witness it firsthand.”

Waarangan translated, his voice carrying the same measured cadence. Tillotama inclined her head slightly, a gesture that conveyed acknowledgment without submission. Her silence, coupled with her poised demeanor, seemed to unsettle Macrinus, though he quickly masked it with a fake smile. “The emperors await within,” Macrinus said, motioning toward the palace doors. “Rome is eager to welcome its honored guest.”

As the procession began to ascend the steps, Kinjal leaned slightly toward Chanchal, her voice barely audible. “Do you think they know how much they tremble beneath their own grandeur?”

Chanchal suppressed a smirk. “Let them tremble. It’s the least they can do.”

Behind them, Tillotama moved with an unhurried grace, each step a testament to the power of stillness amidst a sea of chaos. Though she spoke no words, her very presence seemed to reshape the narrative of her arrival. As they passed through the palace gates, the air grew heavier with expectation, the halls of Rome awaiting to witness the woman who had already begun to rewrite their story.

#gladiator ii#lucius verus#gladiator movie#lucius verus aurelius x south indian oc#macrinus#emperor geta#emperor caracalla

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

17th Century Emerald Cup Created With 252 Carats Of Emerald. Persian Verses Inscription. Belonged To Emperor Jehangir Of Mughal India

Source: Archaeology and Art via Facebook

#mughal india#mughal#emperor jehangir#indian jewellery#emerald#emerald cup#high jewelry#luxury jewelry#fine jewelry#fine jewellery pieces#gemville

580 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today, it's good to be online. Indian Election results are so heartening. Not a victory, yet not a defeat that was projected! It's been 10 years that I feel first time like I can take a breath! Good job I.N.D.I.A. Well played!

#indian elections#indian politics#someone needed to say emperor has no clothes#bjpiss losing ayodhya seat it forever and ever the most ironic moment#let no one talk anymore about where is the strong opposition waah

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

every time a wuthering heights adaptation depicts heathcliff as a white guy an angel dies

#literally bronte never shuts up about him having dark skin#'who knows but your father was emperor of china and your mother an Indian queen' this man was NOT white#wuthering heights#emily bronte#emily brontë#bronte sisters#bronte#brontë sisters#brontë#heathcliff#heathcliff wuthering heights#classic literature#classic lit#literature#english literature#racism#whitewashing

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

#mike huttlestone#gif#Sorted Food#funny#lol#reaction gif#ignorance#ignorance gif#boom#Chef Reviews INDIAN Kitchen Gadgets#wise-emperor

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

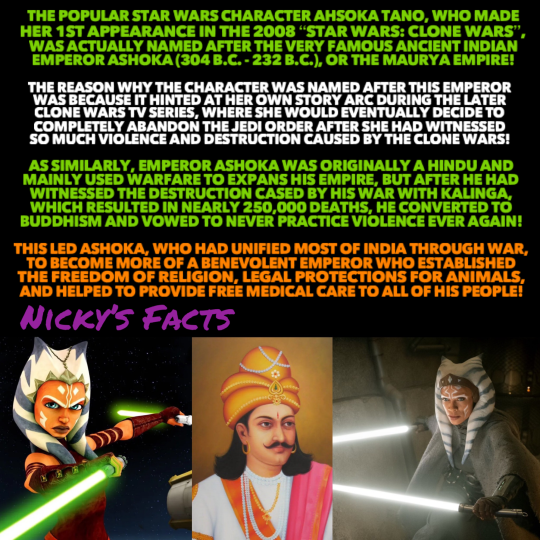

A long time ago two Ashokas went on a quest for moral redemption, changing their worlds forever!

🧡🇮🇳🤍

#history#ashoka tano#star wars#ashoka the great#emperor#indian history#star wars the clone wars#may 4th#maurya empire#kalinga war#movie history#female characters#jedi#hinduism#buddhism#ancient history#girl power#clone wars series#role model#women of star wars#historical figures#india#royalty#ancient#nickys facts

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

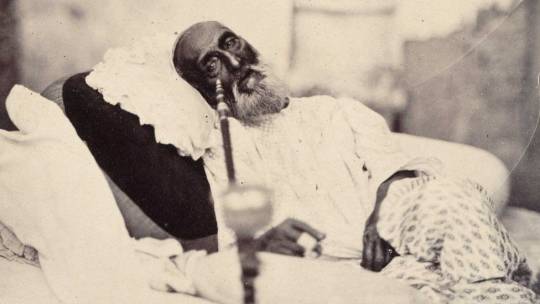

❝ ...In the early nineteenth century, the word Hindustan begins to fade from the colonial archive. The major histories of the subcontinent, written in the early parts of the nineteenth century, were now histories of "British India".

With the British East India Company (BEIC) ascendant, the Maratha or the Sikh polities did not invoke Hindustan in their political claims.

There was a brief last resurgence of Hindustan in 1857 CE. The rebels and revolutionaries who opposed the British East India Company (BEIC) rule rallied to the flag of the Mughal Sultan, Bahadur Shah Zafar. He was once again, hailed as the Shahanshah-i Hindustan (Emperor of Hindustan) - clearly there remained an idea of Hindustan.

After violently crushing the revolution, Queen Victoria took British India under her direct rule and assumed the title of Empress of India, sending Bahadur Shah Zafar to die in exile in Burma.

...And so, (as) per (the poet) Mirza Ghalib, Hindustan became the past. ❞

Source: The Loss of Hindustan | The Invention of India by Manan Ahmed Asif, Pages 1 to 2

Pictured is the one of the few photos of the aforementioned Bahadur Shah Zafar or Bahadur Shah II - the last Timurid-Mughal Sultan - after trial in court and prior to his exile to modern-day Burma, following the unsuccessful and brutally crushed Hindustani Revolt of 1857-1858 CE.

Photo Credit: The British Library

#islam#muslim#history#islamic history#history blog#hind#hindustan#indian subcontinent#india#pakistan#bangladesh#sri lanka#nepal#burma#myanmar#the british empire#the british invasion#mughal#mughal emperor#mughal empire#bahadur shah zafar

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sita is the archetypal form of Lakshmi, in one sense:

Out of all the avatars of Vishnu, Rama is the one who happens to have had the most direct impact on Hindu self-perception. The Ramayana, which includes the Bhavagad Gita, is considered by most Hindus to be the Indian national epic. As Rama is an avatar of Vishnu, so is Sita of Lakshmi. The role of Sita, taken captive by the Asura King Ravana, and the war fought over her between Rama and Ravana, is a woman who adhered to all the various aspects of Dharma asked of a noble Hindu woman.

She also dies unjustly and dies for her husband's honor, showing the idea behind Sati, if not quite Sati, is deeply interwoven into the warp and weft of Hinduism. And indeed, the greatest act of tyranny of colonizing and imperialist forces is not the mass murders and sacking of Hindu temples in the eyes of today's Hinduvta fascism, it's....Sati bans. That's why they hate the British, that's why they hate Aurangzeb.

Sati also illustrates a fundamental rule of Hindu ideology, one challenged by both Islamic-Indian culture (which stands unique in the Muslim world in permitting a role for women that doesn't even exist in theory elsewhere, let alone practice) and the future colonialism of European nations. Namely that a good Hindu woman, like the good Christian woman of times past, defines herself solely in the sight and in the shadow of men and has no existence outside of that.

#lightdancer comments on history#women's history month#india and women's history#the goddess in theory and practice#sita#as I said at the start in some cases the motifs of women in story take precedence over other aspects of history#because to put it very bluntly what little history there is is even more the history of men than elsewhere#Hindus wrote next to no history of their own and had no interest in doing so#the Greeks who wrote what little history of India exists outside the monuments of Emperors were as misogynist as ever#they didn't write about their own women unless they were dragged kicking and screaming into it#they weren't about to write about barbarian women any more than they did about Greek women#thus the first part of Indian history in recorded history is mostly mythological archetypes

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(via "Indian King" Magnet for Sale by MillionaireMF)

#findyourthing#redbubble#king#tamil#tamil king#chola#chera#pandy#pandya#tamil emperor#emperor#indian#indian king#south india

1 note

·

View note

Text

the martyrer than thou syndrome that reblogger had lmao

European history is not white

Someone commented this to a post I reblogged, which message is basically "we shouldn't venerate the Dead White Man HistoryTM and we should elevate other history too, but we still need to learn Dead White Man HistoryTM to understand the world today". It's basically a response to the attitude you sometimes come across in the internet that sees learning about those Dead White MenTM as not worth our time. And this person, who seems to be following this blog because they responded to my reblog, takes it as a personal attack against all white Europeans. For some reason. Well I take these comments as a personal attack against historical understanding.

Firstly, the post clearly didn't say you shouldn't venerate any European history, because not all European history is Dead White Man HistoryTM. Obviously this person thinks European history is white, which is not true, but surely, surely, they know it's not all men? Secondly, what is "west culture"? When did it start? There is not one western culture, not one European culture. The first concept of some shared Europeanness was the Christendom in Middle Ages, but it was not exactly the same as we think of Europe today, because it did not include the pagan areas, but it included a lot of Levant and parts of Central Asia, where there were large Christian areas. And Europe was not "very white" nor was the Christendom. The more modern concept of West was cooked in tandem with race and whiteness during colonial era and Enlightenment, around 17th to 18th centuries. And Europe was certainly not very white then. The western world also includes a lot of colonized areas, so that's obviously not white history. Thirdly, implying that asking white people to apologize for European history (which no one did ask) is as ridiculous as asking black people for African history is... a choice. Black people do exist in a lot of other places than Africa, which white people should be the ones apologizing for, and really white people also have a lot to answer for about African history. Lastly, if you think the quote "anyone who thinks those dead white guys are aspirational is a white supremacist" means you as an European are demanded to apologize for your existence, maybe - as we say in Finland - that dog yelps, which the stick clanks. (I'm sorry I think I'm the funniest person in the world when I poorly translate Finnish sayings into English.)

The thing is, there is no point in European history, when Europe was white, for three reasons. 1) Whiteness was invented in 17th century and is an arbitrary concept that has changed it's meaning through time. 2) Whichever standard you use, historical or current, Europe still has never been all or overwhelmingly white, because whiteness is defined as the in-group of colonialists, and there has always been the internal Other too. In fact the racial hierarchy requires an internal Other. 3) People have always moved around a lot. The Eurasian steppe and the Mediterranean Sea have always been very important routes of migration and trade. I've been meaning to make a post proving exactly that to people like this, since as I've gathered my collection of primary images of clothing, I've also gathered quite a lot of European primary images showing non-white people, so I will use this opportunity to write that post.

So let's start from the beginning. Were the original inhabitants of Europe white? Of course not. The original humans had dark skin so obviously first Europeans had dark skin. Whenever new DNA evidence of dark skinned early Europeans come out (like this study), the inevitable right-wing backlash that follows is so interesting to me. Like what did you think? Do you still believe the racist 17th century theories that white people and people of colour are literally different species? I'm sure these people will implode when they learn that studies (e.g. this) suggest in fact only 10 000 years ago Europeans had dark skin, and even just 5 000 years ago, when Egypt (an many others) was already doing it's civilization thing, Europeans had brown skin (another source). According to the widely accepted theory, around that time 5 000 years ago the Proto-Indo-European language developed in the Pontic-Caspian steppe, which extends from Eastern Europe to Central Asia. These Proto-Indo-Europeans first migrated to Anatolia and then to Europe and Asia. Were they white? Well, they were probably not light skinned (probably had brown skin like the other people living in Europe around that time), the Asian branch of Indo-European peoples (Persians, most Afghans, Bengalis, most Indians, etc.) are certainly not considered white today and a lot of the people today living in that area are Turkic and Mongolic people, who are also not considered white. I think this highlights how nonsensical the concept of race is, but I don't think Proto-Indo-Europeans would have been considered white with any standard.

Around Bronze Age light skin became common among the people in Europe, while in East Asia it had become wide spread earlier. This does not however mark the point when "Europe became white". During the Bronze Age there was a lot of migration back and forth in the Eurasian steppe, and the early civilizations around Mediterranean did a lot of trade between Europe, Africa and Asia, which always means also people settling in different places to establish trading posts and intermarrying. There were several imperial powers that also stretched to multiple continents, like the briefly lived Macedonian Empire that stretched from Greece to Himalayas and Phoenicians from Levant, who didn't built an empire but settled in North Africa, Sicily and Iberia. In Iron Age the Carthaginian Empire, descendants of Phoenician settlers in current Tunisia, build an Empire that spanned most of the western Mediterranean coast. Their army occupying that area included among others Italic people, Gauls, Britons, Greeks and Amazigh people.

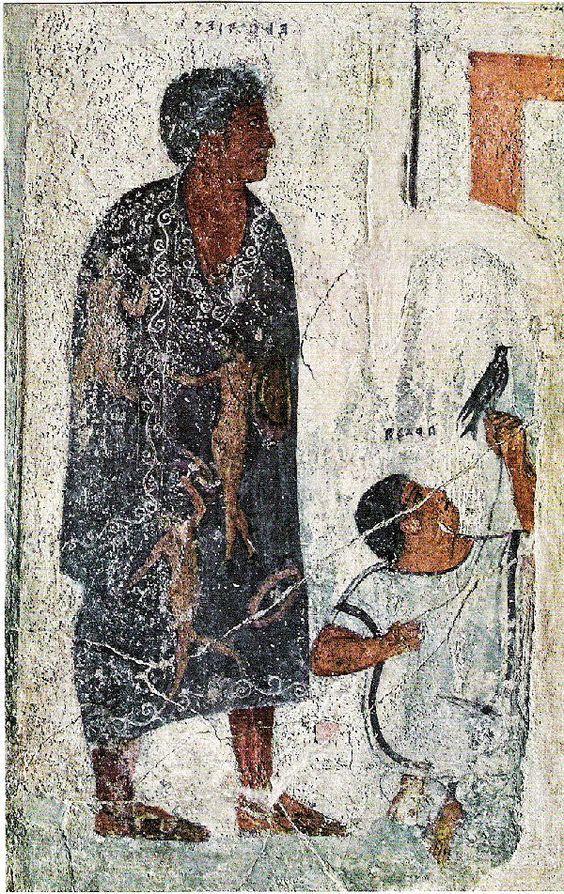

Iron Age also of course saw the rise of the Roman Republic, and later empire, but it was preceded by Etruscans, who populated Tuscan, and possibly preceded the Indo-European presence. However, weather through trade and migration with other Mediterraneans or the continuing presence of darker skin tones of the early Europeans, their art quite often depicts darker skin tones too, like seen below in first two images. Roman Empire at it's height spanned from Babylonia to the British Isles. They recruited soldiers from all provinces and intentionally used stationed them in different areas so they wouldn't be too sympathetic to possible rebels or neighboring enemies. Historical sources mention black Nubian soldiers in British Isles for example. They also built a lot of infrastructure around the empire to ensure protection and easy transportation through trade routes inside the empire. During this time Jewish groups also migrated from Levant to both North-Africa and Europe. Rome even had non-European emperors, like Septimius Severus who originated from Levant and was Punic (descendants of Phoenicians) from his father's side, and who was depicted with darker skin (third picture below). Various ethnicities with differing skin tones are represented all over Roman art, like in the fourth picture below from hunting lodge in Sicily.

Eurasian steppe continued to be important source of migration and trade between Europe and Asia. Scythians, Iranic nomadic people, were important for facilitating the trade between East Asia and Europe through the silk road during the Iron Age. They controlled large parts of Eastern Europe ruling over Slavic people and later assimilating to the various Slavic groups after loosing their political standing. Other Iranic steppe nomads, connected to Scythian culture also populated the Eurasian steppe during and after Scythia. During the Migration Period, which happened around and after the time of Western Rome, even more different groups migrated to Europe through the steppe. Huns arrived from east to the Volga region by mid-4th century, and they likely came from the eastern parts of the steppe from Mongolian area. Their origins are unclear and they were either Mongolic, Turkic or Iranic origin, possibly some mix of them. Primary descriptions of them suggests facial features common in East Asia. They were possibly the nomadic steppe people known as Xiongnu in China, which was significant in East and Central Asia from 3rd century BCE to 2nd century CE until they moved towards west. Between 4th and 6th centuries they dominated Eastern and Central Europe and raided Roman Empire contributing to the fall of Western Rome.

After disintegration of the Hun Empire, the Huns assimilated likely to the Turkic arrivals of the second wave of the Migration Period. Turkic people originate likely in southern Siberia and in later Migration period they controlled much of the Eurasian steppe and migrated to Eastern Europe too. A Turkic Avar Khagenate (nation led by a khan) controlled much of Eastern Europe from 6th to 8th century until they were assimilated to the conquering Franks and Bulgars (another Turkic people). The Bulgars established the Bulgarian Empire, which lasted from 7th to 11th in the Balkans. The Bulgars eventually adopted the language and culture of the local Southern Slavic people. The second wave of Migration Period also saw the Moor conquest of Iberia and Sicily. Moors were not a single ethnic group but Arab and various Amazigh Muslims. Their presence in the Iberian peninsula lasted from 8th to 15th century and they controlled Sicily from 9th to 11th century until the Norman conquest. During the Norman rule though, the various religious and ethnic groups (which also included Greeks and Italic people) continued to live in relative harmony and the North-African Muslim presence continued till 13th century. Let's be clear that the Northern Europe was also not white. Vikings also got their hands into the second wave migration action and traveled widely to east and west. Viking crews were not exclusively Scandinavians, but recruited along their travels various other people, as DNA evidence proves. They also traded with Byzantium (when they weren't raiding it) and Turkic people, intermarried and bought slaves, some of which were not white or European. A Muslim traveler even wrote one of the most important accounts of Vikings when encountering them in Volga.

By this point it should already be clear that Medieval Europe was neither white, but there's more. Romani people, who originate from India and speak Indo-Aryan language, arrived around 12th century to Balkans. They continued to migrate through Europe, by 14th century they were in Italy, by 15th century in Germany and by 16h century in Britain and Sweden. Another wave of Romani migration from Persia through North-Africa, arrived in Europe around 15th century. Then there's the Mongol Empire. In 13th century they ruled very briefly a massive portion of the whole Eurasian continent, including the Eastern Europe. After reaching it's largest extent, it quickly disintegrated. The Eurasian Steppe became the Golden Horde, but lost most of the Eastern-Europe, except Pontic-Caspian Steppe. They ruled over Slavs, Circissians, Turkic groups and Finno-Ugric groups till early 15th century. The Mongolian rulers assimilated to the Turkic people, who had been the previous rulers in most of the steppe. These Turkic people of the Golden Horde came to be known as Tatars. Golden Horde eventually split into several Tatar khagenates in 15th century, when the khagenates, except the Crimean Khagenate, were conquered by the Tsardom of Moscovy. Crimean Khagenate was annexed by the Russian Empire in 1783. Crusades were a movement from Europe to Levant, but they also meant intermarriage in the the Crusader kingdoms especially between the European and Levant Christians, and some movement back and froth between these kingdoms and Europe, trade and a lot of movement back after the Crusader kingdoms were defeated in 13th century. Generally too trade across the Mediterranean sea was extensive and led to migration and intermarriage.

And here's some example of people of colour in Medieval European art, shown as part of the majority white European societies. First is from a 15th century French manuscript depicting Burgundy court with dark skin courtier and lady in waiting. Second one is from a Flemish manuscript from 15th century of courtiers, including a black courtier, going for a hunt. Third is a 15th century Venetian gondolier with dark skin.

In Renaissance Era Europe was only increasing it's trade and therefore had even more connections outside Europe. The first picture below is Lisbon, which had strong trade relationship with Africa, depicted in late 16th century. People with darker skin tones were part all classes. Second image is an Italian portrait of probably a seamstress from 16th century. Third one is a portrait of one of the personal guards of the Holy Roman Emperor. Fourth image is a portrait of Alessandro de' Medici, duke of Florence, who was noted for his brown complexion, and the modern scholarly theory is that his mother was a (likely brown) Italian peasant woman.

Colonialism begun in the Renaissance Era, but the wide spread colonial extraction and slavery really got going in the 17th century. Racial hierarchy was developed initially to justify the trans-Atlantic slave trade specifically. That's why the early racial essentialism was mostly focused on establishing differences between white Europeans and black Africans. Whiteness was the default, many theories believed humans were originally white and non-whites "degenerated" either through their lives (some believed dark skin was basically a tan or a desease and that everyone was born white) or through history. Originally white people included West-Asians, some Central-Asians, some North-Africans and even sometimes Indigenous Americans in addition to Europeans. The category of white inevitably shrank as more justifications for atrocities of the ever expanding colonial exploitation were required. The colonial exploitation facilitated development of capitalism and the industrial revolution, which led to extreme class inequality and worsening poverty in the European colonial powers. This eventually became an issue for the beneficiaries of colonialism as worker movements and socialism were suddenly very appealing to the working class.

So what did the ruling classes do? Shrink whiteness and give white working classes and middle classes justifications to oppress others. Jews and Roma people had long been common scapegoats and targets of oppression. Their oppression was updated to the modern era and racial categories were built for that purpose. The colonial powers had practiced in their own neighborhoods before starting their colonial projects in earnest and many of those European proto-colonies were developed to the modern colonial model and justified the same way. In 19th century, when racial pseudoscience was reaching it's peak, Slavs, others in Balkan, the Irish (more broadly Celts), Sámi (who had lost their white card very early), Finns, Southern Italians, the Spanish, the Southern French and Greeks all were considered at least not fully white. The Southern Europeans and many Slavs were not even colonized (at least in the modern sense, though with some cases like Greeks it's more complicated than that), but they looked too much and were culturally too similar to other non-white Mediterraneans, and they were generally quite poor. In many of these cases, like Italians, the French and Slavs, it was primarily others belonging in the same group, who were making them into second class citizens. All this is to highlight how very malleable the concept of race is and that it's not at all easy to define the race of historical people.

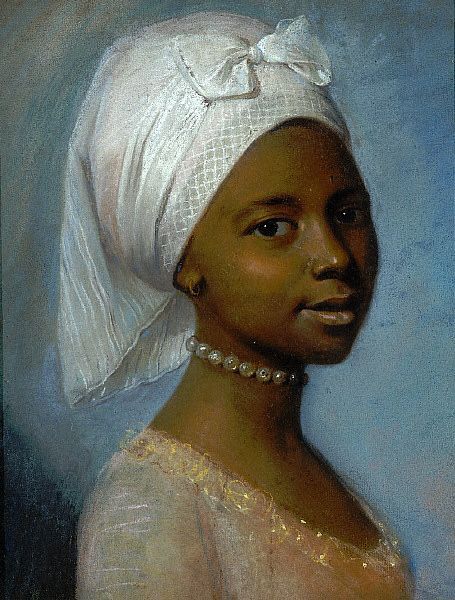

However, even if we would go with the racial categories of today, Europe was still far from being all white in this period. You had Roma, who certainly are not included in whiteness today, and European Jews, whose whiteness is very conditional, descendants of Moors in Southern Europe and Tatars and Turks in Eastern Europe and Turkey, which today is often not thought of as part of Europe, but historically certainly was. And then colonialism brought even more people into Europe forcibly, in search of work because their home was destroyed or for diplomatic and business reasons. There were then even more people of colour, but they were more segregated from the white society. Black slaves and servants are very much represented in European art from 17th century onward, but these were not the only roles non-white people in Europe were in, which I will use these examples to show. First is a Flemish portrait of Congo's Emissary, Dom Miguel de Castro, 1643. Second is a 1650 portrait of a Moorish Spanish man Juan de Pareja, who was enslaved by the artist as artisanal assistant, but was freed and became a successful artist himself. Third is a 1768 portrait of Ignatius Sancho, a British-African writer and abolitionist, who had escaped slavery as a 20-year-old. Fourth painting is from 1778 of Dido Elizabeth Belle, a British gentlewoman born to a slave mother who was recognized as a legitimate daughter by her father, and her cousin. The fifth portrait is of an unknown woman by (probably) a Swiss painter from late 18th century. Sixth is a 1760s Italian portrait of a young black man.

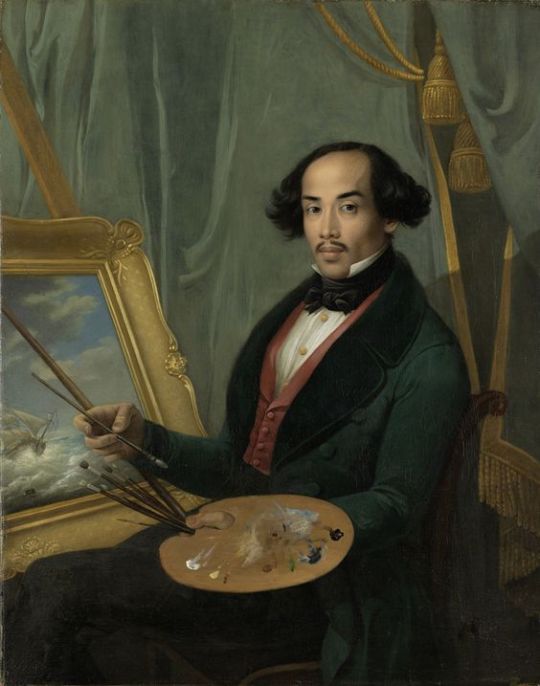

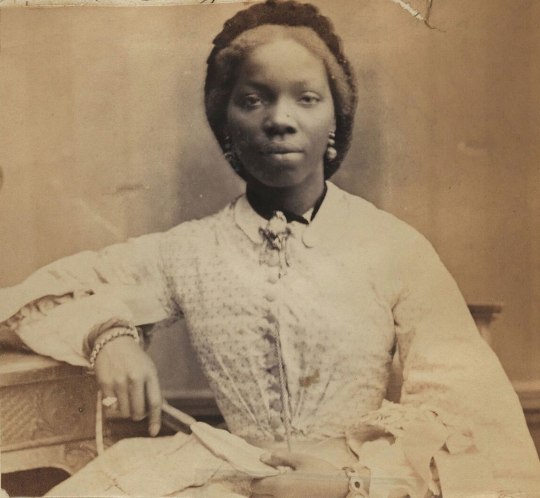

In late 18th century England abolished slavery in British Isles first, then in early 19th century in the whole British Empire, thanks to the continuous campaign of free Black people and some white allies, notably Quakers. Around the same time slavery was abolished in France (briefly till Napoleon got to power) after the French revolution. This meant there were a lot more free black people in Europe after that. In 18th century the Europeans, British especially, were colonizing Asia as much they could, which meant that in 19th century there started to also be a lot more Asian, especially Indian people in Europe. First picture below is of Thomas Alexander Dumas, who was son of a black slave woman and a white noble French man and became a general in the French revolutionary army. His son was one of the most well-known French authors, Alexander Dumas, who wrote The Count of Monte Cristo and The Three Musketeers. Second portrait is of Jean-Baptiste Belley, a Senegalese former slave, who became French revolutionary politician. Third portrait is from 1810 of Dean Mahomed, an Indian-British entrepreneur, who established the first Indian restaurant in London. Forth is Arab-Javanese Romantic painter Saleh Syarif Bustaman, who spend years in Europe. Fifth is a 1862 photo of Sara Forbes Bonnetta, originally named Aina, princess of Edbago clan of Yoruba, who was captured into slavery as a child, but later freed and made Queen Victoria's ward and goddaughter. She married a Nigerian businessman, naval officer and statesman, James Pinson Labulo Davies (sixth picture).

So any guesses on at what point was that "very white Europe" when the "west culture" begun? It kinda seems to me that it never actually existed.

#People forget that Dumas father was literally the first black man to become a brigadier general in Francs#“Slavery is an all black thing; and wealth / nobility an all white thing” ALLOW ME TO DIFFER. Wealth and slavers wasn’t an all race thing.#Also the “we need to make queen Charlotte black because there are not enough black royals / noblemen” is wrong#Like what about the kings and emperors of Haiti? The kingdom of Ndongo?#Also Indian royalty is sooo erased from Hollywood and when represented is soooo stereotypical

201 notes

·

View notes

Text

Top 10 Shah Rukh Khan Films Which Prove That He Is The King Of Versatality!

Shah Rukh Khan at his best! Dive into 10 films that prove why he's the King Of Versatility!

Here are our top 10 picks: https://www.theomenmedia.com/post/shah-rukh-khan-the-versatile-king-celebrating-his-cinematic-legacy-on-his-birthday

#SRK Birthday Special#Bollywood Legend#King Of Versatality#Versatality King#King#Emperor#Shah Rukh Khan#SRK#Bollywood#Indian Cinema#Iconic Actor#Film Legacy#Cinema Celebration#Actor Versatility#SRK Films#Bollywood Star

1 note

·

View note

Text

Rakhi Purnima: A Tale of Threads, Bonds, and Promises

Rakhi Purnima: Origin, Legends, & Modern Traditions of Sibling Bond.

In the heart of India, when the monsoon clouds gather, and the air hums with anticipation, a magical thread weaves its way into our lives. It’s called Rakhi, and it’s more than just a piece of silk or silver—it’s a promise, a bond, and a celebration. So, gather around the virtual campfire, my fellow adventurers, as we embark on a journey through time and tales to unravel the origins of Rakhi…

#ancient tales#Draupadi#Emperor Humayun#Indian traditions#Krishna#panvel#Rakhi festival#Raksha Bandhan#Rani Karnavati#sibling bond#Yama#Yamuna

0 notes

Text

2024 Baltimore Orioles Famous Relations

#64 Dean Kremer: Great-nephew of investor Haim Saban & writer Cheryl Saban. #46 Craig Kimbrel: Brother of former Rome Braves P Matt Kimbrel. #47 John Means: Husband of former Orlando Pride G Caroline Means. #35 Adley Rutschman: Grandson of Linfield University football kick return coach Ad Rutschman. #29 Ramón Urías: Brother of Seattle Mariners 3B Luis Urías. Assistant coach José Hernández: Son-in-law of former Frederick Keys manager Juan Gómez and cousin of former Sugar Land Skeeters 2B Luis Figueroa. 3B coach Tony Mansolino: Son of former Atlanta Braves field coordinator Doug Mansolino. Assistant pitching coach Mitch Plassmeyer: Brother of Indianapolis Indians P Michael Plassmeyer.

#Celebrities#Sports#Baseball#MLB#Baltimore Orioles#Money#Egypt#Books#Alabama#MiLB#Rome Emperors#Rome Braves#Kansas#Soccer#Florida#Missouri#Oregon#Football#Mexico#Seattle Mariners#Puerto Rico#Maryland#Sugar Land Space Cowboys#Sugar Land Skeeters#Atlanta Braves#New Jersey#Indianapolis Indians

0 notes

Text

#one world one smile#razia sultana#first woman ruler of india#biography of razia sultana#sultana razia: empress of india#first muslim woman ruler of india#raziya sultana#razia sultan biography in hindi#real history of razia sultan#indian history#razia sultan history#first turk woman ruler of a muslim sultanate#razia sultan 1st female ruler of delhi sultanate#south asia's first female monarch#the rise of razia sultana#first and last emperor of delhi sultanate#smile

0 notes