#Imrahil

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

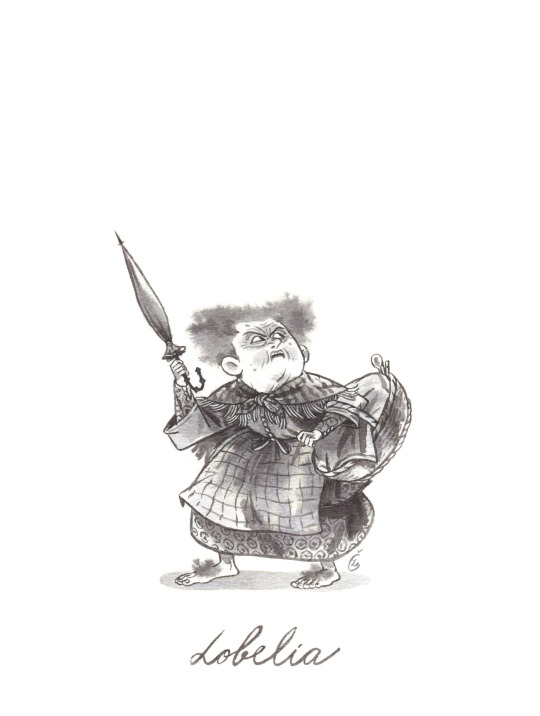

Seven more! Hehehe 🕷🕸 Probably the last few from LOTR (if I'm not tempted to draw Ghân-buri-Ghân, I may be) but because I'm continuing this project till Easter I'll draw few guys from Hobbit and Silmarillion in the days left. Also, I’ve decided I'll be selling the originals after I finish all the drawings. But if there is any character you'd like to have in particular you can start reserving them now. By messaging me here or on [email protected] :^)

Shelob, Wormtongue and King of the Dead are left from this bunch!

The size of the drawings is A6 and prices from 50 to 80USD (shipping included). Also as last year with the dog drawings this year too - all the earnings will be sent to charities. Thank you! 🌿

Rest of the characters are here and here and here and here!

#my art#illustration#ink#traditional art#character design#tolkien#lotr#theoden#shelob#treebeard#fangorn#lobelia sackville baggins#grima wormtongue#imrahil#king of the dead

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Maturity is recognising that all the men of LOTR are beautiful…but moving from a girlish crush on Orlando Bloom’s Legolas to a deep feminine appreciation for Karl Urban’s Eomer? That? That is true evolution.

And don’t get me started again on my head canon of Eric Bana as Imrahil of Dol Amroth. Because hot damn…

#don’t get me wrong#Legolas is lovely#but seriously#eomer#eomer of rohan#lotr#just girly things#eric bana#imrahil#tolkien

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oops, I forgot Ghân-Buri-Ghân, sorry.

#lotr#tolkien#lord of the rings#lotr movies#peter jackson#gildor inglorion#erkenbrand#beregond#halbrand#elladan#elrohir#radagast#tom bombadil#imrahil#glorfindel

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another Tolkien rant before I (finally!!) go back to BG3:

By and large, heredity and ethnicity in Tolkien cannot be understood through blood quantum logic. I don't think this is even seriously debatable, really—it does not work.

Yes, Imrahil of Dol Amroth is many generations removed from his nearest Elvish ancestor. Yes, he's still visibly part-Silvan to someone like Legolas, and is Silvan-style pretty to everyone else, and his sister was mystically susceptible to Mordor's miasma and died of sea-longing.

Yes, Théoden has as much Númenórean ancestry as Eldacar, a literal Númenórean King of Gondor, and has the same Elvish ancestor as Imrahil. No, Théoden is not a Dúnadan and does not inherit Silvan features. Tolkien specifically contrasted the visible Silvan Elvish heritage of Imrahil and his nephews Boromir and Faramir with Théoden and Éomer's lack of them, though in some versions, Éomer inherited remarkable height from his Númenórean ancestry (but not specifically Elvish qualities like beardlessness).

The only known member of the House of Eorl to markedly inherit the distinctive Elvish appearance of the House of Dol Amroth is Elfwinë, son of Imrahil's daughter Lothíriel as well as of Éomer, and Elfwinë's appearance is attributed firmly to Lothíriel-Imrahil rather than Théodwyn-Morwen.

Aragorn and Denethor are descendants of Elendil removed by dozens of generations, and Elendil himself was many generations removed from Elros. Aragorn and Denethor's common heritage and special status results in a strong resemblance and kinship between these incredibly distant cousins, including innate beardlessness and various powers inherited from Lúthien, and a connection to the Maiar presumably derived from Lúthien's mother Melian (great-great-grandmother of their very distant ancestor Elros).

Galadriel has one Noldo grandparent (half as much Noldorin heritage as Théoden has Númenórean). She has ties to her Telerin and Vanyarin kin and inherits some of their traits (most notably her silvery-gold hair), but she is very fundamentally a Noldo.

Túrin Turambar is a member—and indeed, heir—of the House of Hador via patrilineality. However, he's strongly coded as Bëorian in every other way because of his powerful resemblance to his very Bëorian mother, while his sister Niënor is the reverse, identified strongly with Hadorian women and linked to their father, whom she never met.

Elrond and Elros have more Elvish heritage than anything else, but are defined as half-Elves regardless of choosing mortality or immortality. In The Nature of Middle-earth, Tolkien casually drops the bombshell that Elros's children with his presumably mortal partner also received a choice of mortality vs immortality (and then in true Tolkien style, breezed onto other, less interesting points). Elrond and his sons with fully Elvish Celebrían are referred to as Númenóreans as well as Elves, with Elladan and Elrohir scrupulously excluded from being classed as Elves on multiple occasions. Their sister Arwen, meanwhile, is a half-Elf regardless of how much literal mortal heritage she has but also is identified with the Eldar in a way they never are.

There's a letter that Tolkien received in which a fan asks how Aragorn, a descendant of Fíriel of Gondor, could be considered of pure Númenórean ancestry when Fíriel was a descendant of Eldacar, the "impure" king whose maternal heritage kicked off the Kinstrife. Tolkien's response is essentially a polite eyeroll (and understandably for sure), but it's not like ancestry that remote (or far more so) doesn't regularly linger.

The point, I guess, is that there's no hard and fast rule here that determines "real" ethnicity in Middle-earth or who inherits what narrative identification. It's clearly not dependent on purebloodedness (gross rhetoric anyway, but also can't be reconciled with ... like, anything we see). It's not based on upbringing or culture alone. Túrin and Niënor, for instance, are powerfully identified with the Edain narratively despite their upbringings. Their double cousin Tuor, however, is a more ambiguous figure in terms of the Elves, whom he loves and lives among and possibly even joins in immortality—yet Tuor's half-Elf son Eärendil, whose cultural background is overwhelmingly Elvish, is naturally aligned with Men and only chooses immortality for his wife's sake.

Elladan and Elrohir, as mentioned above, are sons of an Elf, Celebrían, and of Elrond, a half-Elf who chose immortality and established a largely Elvish community at Rivendell. But the twins have a centuries-long affinity with their mortal Dúnadan kin and delay choosing a kindred to be counted among long after Arwen's choice.

Patrilineal heritages are more often than not given priority, which has nothing to do with how much of X blood someone has, only which side it comes from. Queen Morwen's children and descendants are emphatically Rohirrim who don't ping Legolas's Elvishness radar (though Elfwinë might, later on; we're not told). King Eldacar is firmly treated as a Dúnadan with no shortening of lifespan or signs of Northern heritage. Finwë's children and grandchildren are definitionally Noldor.

But this is by no means absolutely the case. The Elvishness of the line of Dol Amroth is not only inherited from Mithrellas, a woman, but passes to some extent to Boromir and Faramir through their mother Finduilas. Denethor and Aragorn's descent from Elros primarily comes through Silmariën, a woman (and also through Rían daughter of Barahir and Morwen daughter of Belecthor for Denethor, and Fíriel daughter of Ondoher for Aragorn). And of course, Elros's part-Maia heritage that lingers among his descendants for thousands of years derives from women, Lúthien and Melian.

So there's not some straightforward system or rule that will tell you when a near or remote ancestor "matters" when it comes to determining a character's identity, either to the character or to how they're handled by the narrative. Sometimes a single grandparent, or great-grandparent, or more distant ancestor, is fundamental to how a character is treated by the story and understands themself. Sometimes a character is so completely identified with one parent that the entire other half of their heritage is negligible to how they're framed by the story and see themself. It depends!

#anghraine rants#anghraine babbles#legendarium blogging#legendarium fanwank#imrahil#finduilas of dol amroth#théoden#eldacar#boromir#faramir#long post#éomer#elfwinë#aragorn#denethor#elendil#elros tar minyatur#galadriel#túrin turambar#niënor níniel#húrin thalion#morwen eledhwen#elrond#elladan#elrohir#arwen undómiel#tuor#eärendil#anghraine's meta

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

"For he and his knights still held themselves like lords in whom the race of Númenor ran true. Men that saw them whispered saying: ‘Belike the old tales speak well; there is Elvish blood in the veins of that folk, for the people of Nimrodel dwelt in that land once long ago.’ And then one would sing amid the gloom some staves of the Lay of Nimrodel, or other songs of the Vale of Anduin out of vanished years." - J.R.R. Tolkien, The Return of the King, "The Siege of Gondor"

@arwenindomiel's tolkien south asian week ☸︎ day 5: lineages ☸︎ THE HOUSE OF DOL AMROTH

[ID: an edit comprised of six posters, the main hues of which are light brown and cream.

1: An oval-shaped image of Trinette Lucas, a pakistani model with brown skin and straight black hair pulled back with a garland of white flowers. She is shown facing left, with a neutral expression, and wears large jeweled earrings. Curved text above the image reads "the foundress" in all caps, while cursive text below reads "Mithrellas." Smaller serif text below this reads "/grey leaf/" / 2: An image of sunlight falling in bars through trees, overlaid with a brown shape in the middle. Text over this block reads "the vanished" in all caps, and below in cursive, "Enigmatic," and, in serif text, "But in this tale it is said that Imrazor harboured Mithrellas, and took her to wife. But when she had borne him a son, Galador, and a daughter, Gilmith, she slipped away by night and he saw her no more." / 3: Same format as Image 2, but the background shoes white and beige buildings in an indian style, and the shape in the middle is reversed in orientation. Serif text reads "They were a family of the Faithful who had sailed from Numenor before the Downfall and had settled in the land of Belfalas. . .it is said that according to the tradition of their house the first Lord of Dol Amroth was Galador," and below in cursive "Pious," and in all caps, "the architect" / 4: Same format as Image 1, but the oval portrait shows indian model Deepak Lakshmi. He is a young man with brown skin, short, straight black hair, and a small mustache, facing to the right. He wears a red scarf and a garland of orange blossoms. Text reads "the first," "Galador," and "/tree lord/" / 5: Same format as Images 1 and 4, but the portrait shows sri lankan model Rishi Robin, a young man with brown skin and wavy black hair cut short. He wears a black shirt and faces the viewer, those his gaze is directed out of frame. Text reads "the fair," "Imrahil" and "/heir of Imra/" / 6: Same format as Image 1, but the background shows seabirds flying over blue water. Text reads "the soldier," "Noble," and "And last and proudest, Imrahil, Prince of Dol Amroth, kinsman of the Lord, with gilded banners bearing his token of the Ship and the Silver Swan, and a company of knights in full harness riding grey horses." //End ID]

#tsaw25#mithrellas#galador#imrahil#dol amroth#house of dol amroth#princes of dol amroth#lord of the rings#lotr#the silmarillion#tolkienedit#silmedit#lotredit#oneringnet#tolkiensource#sourcetolkien#fandomaesnet#litedit#fantasyedit#mepoc#edits with the wild hunt#brought to you by me#posters#described#fc: trinette lucas#fc: deepak lakshmi#fc: rishi robin#perennial prince imrahil enjoyer... he shows up for his mentions in rotk and i'm like !!!!#i've been like this since i first read it :o)

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

May I take a moment to be utterly predictable and give my defense of the Rohirrim for failing to understand that Éowyn was not yet dead on the Pelennor Fields?

I know everyone likes to poke fun at my guys. “Oh, if Éowyn was so important, how is it that they didn’t even think to check whether she was really dead? Why did they need Imrahil to set them straight? What a bunch of goofs!”

But, really, I think this was entirely understandable. Éowyn’s critical injury wasn’t (just) some common battlefield wound. She was suffering from the Black Breath, a malady brought on by the Witch King and which puts someone into a “deadly cold” sleep until they pass in silence to death. And she had it BAD — it lays on her “heavily,” and given her one-on-one direct contact with the Witch King, she may very well have had a bigger dose of it than anyone else ever did.

The Black Breath was well known in Gondor. There were “many” sick with it in Minas Tirith’s Houses of Healing, as the forces of Gondor had been tangling with the Nazgûl since the taking of Osgiliath nine months earlier and who knows how often in other instances. They didn’t have a cure for it, but they certainly recognized it. Imrahil would have known about it and even seen it himself in Faramir and perhaps in others in the Houses of Healing when he brought Faramir in.

But you know who had never seen a case of Black Breath before? The Rohirrim! They weren’t used to having Nazgûl up in their business. There’s no long established history of the Fell Riders parading around in Rohan, fighting with the Rohirrim. The few Nazgûl that are sighted there in the lead up to the War of the Ring are in the sky, not landing and engaging directly with the people. So how should the Rohirrim be able to easily spot the difference between the (death-like) effects of the Black Breath and actual death? How should they even know that the Black Breath is a thing that exists? They shouldn’t!

Did they screw up by not taking the time to do a comprehensive check of Éowyn’s various vital signs? Yes. But is it ridiculous that their cursory check of her didn’t clue them in to her unique and previously-unknown-to-them sickness that had all the appearance of death? I don’t think it is. Éomer and his men aren’t dummies. They were just non-healers with no relevant expertise who were experiencing massive emotional distress while in the middle of an active battlefield. Imrahil, by contrast, knew what to look for, had no emotional investment in Éowyn to cloud his judgment, and came upon her much closer to the city, where things were quieter and less chaotic. OF COURSE he did better! The Rohirrim made mistakes, but they were understandable mistakes! So let’s all cut Éomer some well deserved slack, yes?

#éomer#éowyn#imrahil#yes éowyn was still alive#but those rohirrim did the best they could#and deserve a break#meta

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

Look, I know this is kind of conjecture, but there is just something about Éomer adjusting to a life after the War of the Ring with Théoden and Théodred gone, and knowing that Éowyn will be moving on to live her own life far away from him, and then meeting Lothíriel and through her becoming adjacent (more so than just as a friend of Imrahil) to her Amrothian family, gaining a father-in-law and no less than three brothers, and all that comes with being a part of such a company. It must be so strange and yet so comforting for him. He wonders about how Théoden would have got along with Imrahil. And before he knows it Imrahil has adopted him and Éowyn.

I have this mental image of Éomer nearly weeping in relief after his and Lothíriel's engagement is made. Finally, he has a family.

#Éomer#Eomer#Lothíriel#Lothiriel#Imrahil#House of Eorl#House of Dol Amroth#Eorlingas#Rohirrim#Gondor#Tolkien#Lord of the Rings

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

Boromir Week Day 2: Maternal Family, Grief/Loss

Written for Boromir Week 2025 (@boromir-week), for the day 2 prompts ‘maternal family’ and ‘grief/loss.’ I’ve been a lurker in the LotR fandom for about a decade but have always been too intimidated by the prospect of actually writing fic for it, but Boromir is The Guy Of All Time and I couldn’t resist crawling out of the woodwork for this event. Couldn't manage to do something for the full week, but this is the most fic writing I've done in almost two years, so that feels like progress!

Just one night. Just one night alone, unseen, unasked for, unneeded. Just one night, when no one needed him to be strong, or cheerful, no one needed him to be anything at all, that he might break apart in peace, and piece himself back together with none the wiser once his hands grew steady again. Make himself whole again, that he might be of use. For broken pieces left only mess, and he had to clean up the mess. He could not, would not let the dream come to pass.

Just one night. Surely it was not so gross a sin, to not be strong for just one night.

A tale of nightmares, grief, and late-night conversations.

Long Nights and Lone Soldiers

The Houses of Healing. Warped. Halls stretched, an impossible, impassable distance, light at each end like two mirrors placed at odds. A pallor, moon-bright, beyond the shadowed corridor; a bustle of faceless folk in Healers’ robes, wicked knives in hand.

His mother, lying upon a small cot. Dirty, dingy. Fraying linen. No good for a sick woman. No good for even the most wretched swine.

The Healers that were not surrounded her, a murder of crows at a carrion feast, and their hands were no more, they were only knives. Knives in and of them, cutting his mother open. All up the veins of her arms, down her legs, but she did not bleed, for those veins disgorged a black stuff like pitch as they cried to be opened, cried when it dripped, splattered, crumbled over the floor, like wet ash. Shadow inside her, screaming its death throes on the filthy floor.

At the end of the corridor, a small washroom. The black stuff welled up in the cistern in great heaving clumps, endless. He tried to shove it down: first with his hands, but it broke apart beneath them, clinging to his skin, a second skin, in and of him, too, and no matter how he clawed at himself he could not cast it off.

In one corner of the room there was a well, and there was too much mess to question why. Bucket after bucket of moss-filmed, brackish water he drew up from its depths, to try and wash the ash away, but when the water touched it it only grew as some foul beast, like a tick gorging itself on blood, and clogged up the works. Clogged up the works, and clung to his skin, spattered over his white shirt and his bloodied lips, and tasted not of Mordor-ash but sweet rot, meat gone off, dead flesh. He spit, retched, tried to rid himself of the taste, but blood spilled from his mouth when he opened it, painting his chest all awash in red, marred by clumps of black.

Back to the well. His arms burned. His whole body burned. But he had to fetch more water.

No one could see him. No one could hear him. And it was better they couldn’t, he needed to clean up the mess. The ash was in the pipes and on the floor and in the water and all over him, and it would only make his mother sicker, if it welled up faster than they could cut it out of her, and no one could see him, to know he was making it worse. No one would help him, if they knew he was making it worse.

He had to fetch more water. Had to get up, to fetch more water. Had to clean up the mess.

He staggered the few steps, the few miles, to the door. Slammed it shut. None turned to mark the noise. That was good.

To the well. To the rope. His hands burned, flayed open on the rope, and the ash stung him, where it touched his skin. His hands shook too badly to bear the bucket aloft, he could only drag it, and now the whole of him was shaking, too much strain on weary limbs, and the water slopped out. Hissed where it touched the ash and the blood upon the floor. The whole of him, what was left of him, shaking from the inside out, and it’s all he could do to keep hold of the bucket as he retched again, innards wrenched up out of him with the blood that burned his skin. But he does not let go of the bucket. Cannot let go of the bucket. For the water was filthy, unfit for even a dog to drink, but it was all he had left, to try and wash away the stink of Shadow.

Boromir blinks awake.

Too loud. Too bright.

For a moment he doesn’t know where he is, or when. Knows only that he’s trapped, suffocating, weight and heat pinning him down, and he cannot breathe as he ought, and whatever he’s lying in is damp, salt-damp, like he was one of the bloody crabs they had buried beneath sand and seaweed to steam the way Imrahil dátheg taught them, Valar above, but he was being cooked alive–

Breathe. Breathe as the soldiers did. In four hold four out four hold four. Until the breaths stop jabbing needles down the back of his throat, stop sticking in his chest and shivering on the air. Like he’d caught his finger in a door frame, or beneath the blow of a hammer, everything in his chest clutched up tight. Blood rushes in his right ear, in time with the thundering of his heart. Out of time with the rush and roar of the waves, that never stopped, the crashing push-pull he could feel tugging at his limbs, his very blood, even now, some days since they’d disembarked.

Dol Amroth. Prince Adrahil’s hold. His mother’s home.

There’s nails piercing his skull. Just above his ear on the left side. Above his right eye. Nails piercing his skull, a yawning pit in his stomach, hollow hunger and swirling sickness killing the itch under his skin that never went away, to move, to do, to be. He does not think he could move even if he tried. Does not think he wants to. Not here, where the cold light of the moon shone brighter than even the summer sun back home in Minas Tirith, burning away the shadows he longed to hide in, that none might trouble themselves to look on the mess of him. The shadows where the fading vestiges of the dream tried to hide themselves, but they could find no purchase there, and so slunk back to him, where shadow lay curled round him, the only thing left in this world that would hold him.

His head hurts. Everything hurts.

It might be hours, that he lies there. Might be but minutes. Maybe just seconds. Just…breathing. Breathing, breathing, until his heart slows, and the rushing in his ear with it, but never in time with the waves. It would be better, if they beat in time. His body in tune with nature, not pulled every which way away from it, it would be better if they sounded as one. He could sleep, then. But they remain out of time, out of tune, ever out of line, and it makes him…

It should make him angry. Would have, before. But nothing had felt real, since their mother had last taken to her bed, nothing had–felt. It was all just…dim. Muffled. Like sea-fog, that crept in out of nowhere until all the world was grey and cold, and you felt the only soul in the world, adrift, because the fog covered all, and you could see nothing, touch nothing, and nothing could touch you. Until you forgot what it was to see, to touch, to be touched, because the fog covered all, and you forgot it had ever been else.

The ship had run afoul of a storm on the way. A squall. Everything shrouded in fog, the weight of lightning in the air like chains winding all round his limbs, freezing him in place. That was how the world was, now. And it was better that way. Better to live outside himself, locked away from himself. He could stay standing, if he didn’t look at the way the ground under his feet had been torn away. Could stay strong, if he told himself he had always been cold, and couldn’t reach for the memory of what it was to be warm. Everything that had burned, now a mere itch. Everything that had hurt, now a dull ache. Like an old bruise, half-healed, nigh-forgotten, that you had to press on to feel.

But now everything hurts.

A part of him wishes his brother were here. Though Boromir had not slept in the nursery in Minas Tirith for months, for it was no fit place for one already a squire, too soon to be a man, for as many months Faramir had been sneaking into his room a-nights, or Boromir back into the nursery, and he would hold it in himself till he died that he preferred it that way. But Faramir was in the nursery with baby Elphir, and though there was room enough for Boromir there, too, he had spent the past nights there, he could not bear the thought of any eyes on him, tonight, could not bear the weight of another being in the room, that ever-present pressure to be in the presence of any other, and in any case if Faramir had had nightmares of his own he would have snuck in by now. Not that he wanted his brother to have nightmares. If he had his way nothing would ever harm the little one: not man nor Orc nor foul sickness nor fell dream. But his way was not the world’s way, if he had no power to change it, he could at least fight it. Strike a blow against it with one arm, and bear his shield in the other, to shelter those he loved from the worst of the pain he would fain they never knew at all. Let the lad hide himself from the world in his arms, that he might see with his own eyes that he was, if not wholly well, at least unharmed.

And naught would harm him, while Boromir was there to protect him. So he had vowed from the moment of his birth, standing by his mother’s side as she looked down upon the babe in her arms, eyes too bright with fever and tears like jewels and a kind of love so desperate it frightened him.

This is your brother, Boromir, she had said, when he held the babe in his own arms, and marvelled at how this little person, not yet an hour old, was a soul all his own, who had buried himself deep in Boromir’s heart where he would live beyond death. No matter what poison the years of toil and trial work on you both, he will always be your brother. You must protect him; you must guide his hands and feet, and ever walk beside him, though the years would bid you walk before. Do not let the shadows claim him.

Not the Shadow in the East, that devoured more of their home with every passing year; nor Boromir’s shadow, for when the ash and the haze bloodied the sun, their people looked to him instead. The winter babe, the miracle child, who had railed against the Shadow from the very moment of his own birth, so all the folk of the houses said. Twisted round in the arms that held him, for babes were born in chambers facing West, and screamed, and kicked out at the black stain marring his sight, as though he had any hope of striking some lasting blow against it. It was a fair omen, the people whispered. Born to fight, the land’s born protector. A beacon of hope, a light in a darkness without end. He would shine, he would burn, for the people wished it of him, and their father needed something bright in the world he drew dark curtains over in his despair, and someone had to. Why not him, he who was older, stronger, he whose duty was to serve Gondor to the last, even if it meant the last of his lifeblood might water her fallow fields just that bit longer? Why not him, if it meant Faramir could step out of the shadow he cast and into the peace he had fought to give him?

It was the least he could do, when he had failed to protect Faramir now. Better that he die, if it meant Faramir could live. Better that he leave Faramir to sleep now, if it meant he might find reprieve from the sickness of grief for a little while, and none might be by to see Boromir’s weakness. For his hands still shake, when he tries to shift the choking covers off. And everything still hurts.

Just one night. Just one night alone, unseen, unasked for, unneeded. Just one night, when no one needed him to be strong, or cheerful, no one needed him to be anything at all, that he might break apart in peace, and piece himself back together with none the wiser once his hands grew steady again. Make himself whole again, that he might be of use. For broken pieces left only mess, and he had to clean up the mess. He could not, would not let the dream come to pass.

Just one night. Surely it was not so gross a sin, to not be strong for just one night.

X X X

So much their mother’s sons.

Imrahil of Dol Amroth had wasted no time after his sister had been laid to rest in the Silent Street, to ask whether he might bring her sons back with him to spend the summer as they had every year ere the last, when Finduilas had been too weak to travel. In part because Finduilas would have wished it, but in larger part because it would do them well, to have at least one thing that was familiar in which they could take comfort, amidst such terrible upheaval. So he had said to Denethor, pleading his case in the small hall. Had said, too, that it might serve Denethor better if he could mourn and marshal himself without the need to coddle the children’s tears, though the words burned like bile in his throat to utter. But he knew they would sway the intractable Steward, who had no patience for his own sentiment, that he was ever quick to deem weakness, and less for the like in any other. Even his own children, who for all their eyes were dark with grief as those of men grown, were still so young.

How could he leave them in Minas Tirith, when Denethor’s eyes fair burned with hatred to look on them? They who carried so much of their mother in them: Faramir with Finduilas’ eyes, her probing questions, her sensitive spirit and way of seeing deeper into men’s hearts than they knew what to do with, so much sharper yet so much kinder than Denethor’s own Sight; Boromir with her sea-carved features, her gentle heart, her fiery passion that burned too bright, burned out too quickly. He could hardly even blame their father for being wary to look on them, when just the sight of them brought the image of Finduilas back to fractured life.

They had tried so hard, that wretched day. To be small. To be good. Faramir buried his sobs in his brother’s tunic, thumb in his mouth as though he wished to silence himself, the questions that were ever wont to pour from him as clear water welling up from a mountain spring, muddied now by this storm of feeling he might not even remember, in the years to come. He had followed the procession like a faithful shadow, though his legs grew evermore unsteady with the unaccustomed toil, and when he stumbled, Boromir was there to steady him; when he fell, there to catch him. Boromir had had one hand up to help bear the bier, though his child’s strength, too great for his age though it was, could do little that the six grown pallbearers, his father among them, could not. And with his other hand he had carried the little one, when he could walk no longer. Had carried him down through all seven levels and back again, and stood at his father’s shoulder as if to guard Denethor from the weight of a thousand tearful eyes, or perhaps to guard the people from the poison of their Steward’s silent grief, and all the while had shed no tear, nor spoke a word but to comfort his brother, and stood rigidly upright. Unbowed, though the weight of the broken yoke of his family would have borne a lesser man to the ground.

No. Better they come to Dol Amroth, and be among those would would give place to their grief; would weather the storms of confusion and rage and sorrow that would sicken them to keep inside themselves, the way their father would counsel them. The way such things had sickened that father, such that his heart had turned to stone, and he looked at his sons as though he wished to cast them and himself into the grave with his wife, for the light of his world had been buried with her.

Imrahil grieved with him. No matter than Ivriniel and Adrahil their father could not bear to look on him, and railed that he and his city and heart of stone had killed Finduilas, even as the vase killed the wildflower no matter what care he who tore it from the free earth lavished on it. But Denethor had loved Finduilas as best he could, and she had loved him, as much as he would let her, and for all he felt they all had failed her, to let her go, she had had her own pride. Would never have countenanced leaving Minas Tirith when the greatest shares of her heart were there.

He grieved with Denethor. But more than that he grieved for the boys. So he had pleaded, and cajoled, and Denethor had not protested quite so much as he had expected. The grey weeks aboradships had passed in a haze, unmarked by them all, but once the squall had blown over the skies had cleared, and it felt a great weight off his heart, to breathe clean air again, and to see the blue of the true sky.

The air smells like summer, Faramir had whispered when they pulled into port. The first words he had spoken since he had asked his brother in the tomb whether their mother’s spirit would disappear from Mandos’ Halls after her body rotted.

Faramir, at least, slept peacefully this night. Curled up upon the cushions of the window-seat like a little cat, his book of wonder tales carefully closed. He did not wake, when Imrahil bent to gather him up: only hummed softly, and cuddled closer to the body that held him, clinging like a limpet when he tried to set him down in bed. So he sits himself down, instead, and rocks the boy gently in his arms, and tries to ignore the way his heart feels too large, of a sudden, for his chest, digging into the cage of his ribs with a sharp pain like the bone was splintering into the soft tissue.

Finduilas, too, had always slept better by the sea. Soothed by the song of wind and sea and stars. And neither of the boys slept much on the ship, and they had not slept at all the first night here, nor the night prior. Idhreniel had gone both nights to check on them, and reported that they had sat up together the whole night in the window-seat: Faramir curled up in Boromir’s arms as the elder talked himself hoarse, too low to disturb Elphir or to make out any words from the doorway, though he had fallen silent when he’d marked the shadow upon the threshold. Silent and grave as the stone of his home, and Idhreniel had wept, a little, when she had told Imrahil the boy had glared at her like he wished to run her through, before he had realised who she was. Like a wary guard dog, hackles raised against the slightest hint of a threat to what was his to protect, a look no child ever ought to wear. And it was only in deference to that look, that terrible, red-eyed, cold resolve, that she had left them without a word.

But Faramir slept, this third endless night, and Boromir was not here.

Idhreniel and Ivriniel had argued hotly against giving him his own room. It mattered not what the custom was in Minas Tirith, it would be better for both boys to be near each other. And on the ship Boromir himself had said that he was a soldier of Gondor, he would know far worse billets soon enough, and he would sooner sleep on the rug before the hearth like a dog than leave Faramir on his own in a strange place. None had had the heart to dissuade him. But Imrahil had argued, instead, that it would do them both well to have some private place to retreat to, if they needed it, and so they had made up the little anteroom adjacent to the nursery for Boromir, not expecting it would see much use. But it was to that room that he had retired after supper, after eating too little and saying less. Faramir, with a strange glint in his eyes that bespoke of knowing far beyond his years, had laid a hand on Imrahil’s arm, and whispered that they were best leave him alone till morning, he would be alright by then. He always was.

Faramir had scowled, as he’d said it. Like he couldn’t quite believe anyone could always be alright, not even his bold brother. Which meant it was Boromir who believed it. Boromir who felt he had to be so, and Faramir who let him wrap himself in the falsehood like armour, for to try to be otherwise after so long being only strong would break him.

Ai, sister, what has become of your boys? But she would never again answer him.

The barred nursery window had been opened as wide as it could go, though no breath of wind off the sea stirred the heavy air this night. The window in Boromir’s room, though, was shut up tight, though Boromir had ever been the one to throw open the windows of any chamber he found himself penned up in; to run to escape the confines of those chambers, because he claimed he could not breathe, in places where nothing moved. The window had no curtains, and in the bright moonlight the blanket-covered lump huddled up on the bed makes Imrahil frown. It was far too close in here, far too warm, for what seemed to be every spare blanket from the sea-chest at the foot of the bed. But Boromir had always been thus, preferring to sleep half-crushed beneath weight that would have suffocated a less robust child. Well Imrahil remembers Finduilas writing them of this peculiarity of her firstborn: how he had used to curl up under his father’s hauberk in those distant tender years before Denethor had taken to wearing it beneath his robes like a second skin, training his body and mind wholly for war and hardening himself to all in the world that was gentle.

Imrahil had asked Boromir once, why he did it. Boromir had said only that he needed something to keep his soul from drifting out of his body, because he feared he might fly too far from himself and not be able to come back, and his family needed him here. He had not met Imrahil’s eyes as he said it, and Imrahil had never asked again.

The lump on the bed lies still. Too still. Even when Imrahil sits gingerly on the edge of the bed, Boromir does not stir at all. Boromir who was never still, not even in sleep: too much energy in him, too hot a fire burning under his skin. And he was not asleep now. His breathing betrayed him. Too shallow, too measured, as one fighting with all his strength to keep silent. But when Imrahil reaches out to lay a hand over his brow, he flinches away. Buries his face in the sweat-soaked pillow so not a bit of him remains exposed to the air, as though the world were too much to bear unarmoured.

“Your brother fell asleep over his books,” he says quietly, drawing his hand back. Clenching it into a tight fist, pressing it hard into the meat of his thigh, letting the sting of it draw his mind away from the way his heart feels as though it were cracking in two. “Wonder Tales of Sea and Stone. I think they must have brought some wonder to his dreams, for he was smiling when I left him.”

“Good.” Boromir relaxes, just a shade. Ever the elder brother. Seeking reassurance of the wellbeing of the younger, heedless of his own. But there’s something faintly bitter in the word, muffled though it is. As though he begrudged Imrahil the knowledge that should have been his–or berated himself, that he had not been there to gentle Faramir into sleep himself.

“He said we ought to leave you be.” Never before had Imrahil felt himself so at a loss. But never before had Boromir closed himself off so deep inside himself he could not be reached, either. “It can be our secret, that I did not heed him.”

Boromir breathes in, long and slow. Silent, but Imrahil watches the way his back heaves, beneath the mess of blankets. Watches the way it shudders a little, as he breathes out. “You should have.”

“He sees much.”

“More than anyone ought.”

The gifts of the blood of Númenor ran true in Faramir, as they did in Denethor. So, too, did the clear Sight of Mithrellas’ line, that Imrahil himself knew something of, that had so weighed on Finduilas’ heart. Boromir, as far as any of them could tell, had no such gift, no Sight, and Imrahil’s heart breaks for him, so caught between forces and powers he knew nothing of, except that they seemed a curse upon those he loved, with no power of his own to wield against them but the meagre strength of wretchedly mortal hands and heart.

“It is a gift of a hollow sort,” Imrahil says carefully, feeling as though he were but a youth again, new learning to swim, trying not to gasp as the seafloor fell out from under his feet. “A heavy burden to bear, yet it is a gift all the same.”

“It is a curse,” Boromir snaps. Fabric rustles sharply, crumpled between a suddenly clenched fist. Yet still he does not rise. “How can you of all people call it a gift, when I know you dream as Faramir does? Is it not enough he suffers to see in sleep what he cannot comprehend when he wakes, that he must dream of drowning, too, and a horror of a future he doesn’t even have the words to name?”

“And so you watch the nights out, that you might shield him from that horror?” Drawing in an unsteady breath, Imrahil carefully settles a hand over Boromir’s back, instead. Hoping the weight of it might prove a comfort, with enough layers between it and the boy’s skin not to chafe. “A lone soldier cannot hold a picket, lad.”

Boromir sighs, weary as a man four times his age, and curls in a little on himself. Defensive. As though he were tucking the soft heart of himself away, deep within where naught could touch it.

“Not all foes bear weapons,” he mutters through gritted teeth. “The least I can do for him is try.”

A boy’s voice. A man’s words. But Boromir had held a sword in his hand even before he could walk; had wielded that sword with skill far beyond his years before he could read. He knew his duty to his house, to his kin, to his land, better by far than he knew his own wants and needs, and he had not been a child since he had taken it upon himself to bear up father and brother both. Blinding himself gladly to his own grief, that he might better see and serve theirs.

Little wonder it reared up to bite him now. There was no shadow here to steal his sight.

“And what of you, sweet bear?” Imrahil murmurs, almost too low for Boromir to hear. “Who will try for you?”

Who will you let near enough that they might take you in their arms as you would comfort your brother, when your own dreams go ill? Who will you let see what you would bury within your heart as you bury your body now, shrouded and armoured so naught might touch you? Who will you let hold you, lest you forget you, too, are but human?

He cannot bring himself to speak. But the least he can do is try.

“It is no weakness, to grieve,” he whispers, holding himself stiff against the flood of tears that stream unbidden from burning eyes. He tastes salt upon his lips. Wishes, so much it hurts, that it were the salt of the sea. “To weep. Will you think your men weak, when they shed tears over their fallen comrades in arms, when the fever of battle drains from their limbs and leaves them trembling and raw like green squires again? Do you think your brother weak, when he seeks you out night after night, fearing the dreams that plague him? Your father, when he could not bring himself to rise from your mother’s side, even when the doors to the tomb would have closed on him? Your uncle, who weeps before you now? Why, then, call you it weakness in yourself? Is it not a sort of arrogance, instead, to hold yourself so far above every other person in your life, to whom you would extend such grace, to fall so much harder?”

Boromir lies silent for a long time. Long enough Imrahil thinks he must have overstepped; wonders, desperately, if he might have dropped into sleep at last. But all at once the boy uncurls himself just long enough to grab hold of Imrahil’s arm and huddle up close to it as he had not since he was but a babe, and Imrahil realises too late that he is sobbing: great, heaving cries, so hard he fears he might make himself sick with it, utterly silent. Weeping still himself, Imrahil shifts to lie atop the covers: curling up around Boromir, making his own body into a shield, that his nephew might finally cry, finally feel, without fear of the weight of eyes against his back. No longer upright, nor unbowed, that proud back. It had borne too many blows.

By the morrow he would stand tall again. Force himself to it. But just for tonight, he let himself be held.

Boromir’s nightmare was based pretty much beat for beat on a nightmare I had the night before I wrote the draft of this, although it was either a stranger or another manifestation of myself, not my mother, in the bed, and it took place in family home’s basement (so the cistern was a bathroom sink and we needn’t go into detail about what was clogging the pipes).

The process of writing this was absolutely CURSED: I handwrote about half of it in a park while dissociated as hell, then didn’t manage to write the other half for several weeks. I never wound up finishing the handwritten draft at all, and was resigned to winging the rest. Typed up the first half: I edit as I type, so much was added/changed from the handwritten text; this will prove significant. Brought my fanfic notebook to work yesterday (Friday), intending to type up the rest, and managed to do that, up to where I’d stopped writing. Amazing, I think to myself! I have a whole Friday evening free to finish it! Only to get home from work and realise that NOTHING of what I had typed during the entirety of the day had saved (I was typing it into a draft email in Outlook Web because that’s what I use for work, and this isn’t even the first time it’s happened, but I forgot to send the draft to myself because normally it Does succeed in auto-saving and I was banking on that happening this time). Because I hadn’t deleted the draft, I couldn’t recover it, so I’ve had to now retype the entire second half pretty much from memory. Fun times.

I stole the name of Imrahil’s wife (Idhreniel) from the_ocean_weekender’s fics; go check them out on Ao3, they’ve written some absolutely top-tier LotR fic.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

New prince Imrahil miniature revaled by Games Workshop for Middle Earth Strategy Battle Game.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dol Amroth and their Swan Knights will never not be funny to me. Because yes, swans are elegant, of course the famously noble, very Numenorean family would have that as their banner. You know what swans also are? Territorial and absolutely feral if you approach their home and nesting site. (Mute swans are particularly vicious, many swans are just aggressively defensive, mute swans are actively dicks.)

I love the idea of of Imrahil and his family meeting important people and they're so put together and regal, and then you see them in battle and they are... so scary. I love a Lothiriel who seems so smooth and demure and then will absolutely punch the throat of anyone who touches her without permission, no hesitation, you should have known better than to the touch the Princess of Dol Amroth. I love this family of beautiful noble people who defend their home so viciously that they can bring the most troops of the principalities. What? Like it's hard? A family that will not hesitate to cut you but they'll also be the symbol for nobility and honour, with a Prince that even elves know is a pretty impressive person.

Give me the family of Dol Amroth who are loving and calculated and cold and deeply efficient at dealing with threats. Ones who surprise their enemies by being three steps ahead at all times, but 'Elphir could not have done this, he is so noble,' yeah buddy, but you hoarded grain during a siege so I hope you have fun in the Dol Amroth prisons until after Morannon when we can be bothered to deal with you.

Turncoats? Hard to turn a coat without any of the correct information and each and every one of your sources rounded up before you can warn them.

Slimy advisors? Eaten for dinner, Denethor; sad but we planned for this, Mordor and certain death? Sure, not a part of the plan but our knights are renowned for their battle prowess, let's go and tear Sauron a new one.

Give me noble, coldly efficient, wildly territorial and very slightly feral Dol Amarothians. I beg you. Make their swan a symbol of their absolutely unhinged defense of their beautiful, elegant home.

(But like wild oceans and massive mountains? I have a whole post about how this also gives us insight into Imrahil and his kids, or like, my version of them. Water and stone, commanding oceans and navigating massive peaks. The children of Dol Amroth grow up walking uphill both ways, their knees are scarred and bloody from slipping down sharp mountain paths and they are honed to their lands.)

#imrahil#lothiriel headcannons#lothiriel#dol amroth#meta#I am very normal about Prince Imrahil the fair and his four wild children#i'm so committed to vicious clinical effective rulers#who are also good and fiercely loving and warm#but among their own#among the people they consider 'theirs'#(and of course eomer and eowyn are considered theirs#of *course* they are)#give me a family who contrasts Rohan and balances them#a clash of cultures where the clash is positive and open and still a bit unnerving#i have a fever dream memory of getting taken to a water-fowl enclosure at our local petting zoo#a gang of 20 third graders#it had just rained and we were slipping and sliding in the mud and two kids got bit by swans#I narrowly avoided a duck getting two of my fingers#there was a lot of crying that day

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

#sorry i haven’t read the hobbit as much as the other books#so i’m kinda behind on good dwarf trios#lotr#jrr tolkien#lotr books#lord of the rings#the silmarillion#the hobbit#lotr poll#tolkien legendarium#first age#third age#beren and luthien#huan#frodo x sam x rosie#aragorn#legolas#gimli#thorin oakenshield#fili and kili#merry and pippin#treebeard#boromir#faramir#eomer#imrahil#gollum#gandalf#elrond#galadriel

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

#tolkien#lord of the rings#lotr#lord of the rings movies#gamling#helms deep#imrahil#cirdan#tom bombadil

393 notes

·

View notes

Text

Re-listening to LOTR again and I’m at the section where everyone is cleaning up after the Battle of Pelennor Fields, and I just listened to Legolas and Gimli telling the hobbits about the Paths of the Dead. Gimli immediately refuses to talk about it, doesn’t even want to think about how horrifying the experience of walking into the lair of the unquiet hostile dead was for him, meanwhile Legolas is over here, “Didn’t bother me a bit! Let me tell you all about it! 😁”

Like, Legolas, you silvan jerk.

But even funnier was the way everyone talks about Prince Imrahil, who everyone immediately comments must have some elvish ancestry.

Now, I don’t remember every passage written by JRRT, but I’m pretty sure there were specifically three big unions of elves and humans throughout history, and every one produced some crazy-famous lineage that could live five hundred years or had some kind of incredible elven power or otherwise went on to make a giant impact on the world.

But apparently, some ancient Nimrodel elf back in the day hooked up with one of the locals in Gondor and the whole family just went on to…quietly mind their own relative business at Dol Amroth?

Now, we know that Nümenor’s kings technically had elven ancestry via Elros, but the thing is that several other characters in Gondor are also pretty directly descended from Nümenor (Denethor, Faramir, Aragorn), and apparently people make the distinction when it comes to them. All the descriptions talk about their relationship to the old kings of men and their ancient empire, with basically no mention of elves.

Imrahil, though? Had to be the result of that Fëanorian Frickle-Frack!

#lotr#tolkien#imrahil#numenor#seriously everyone takes one look and knows his great-great-great ancestor fucked an elf

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Till Freitag

Concept Designer

artstation bsky.app instagram twitter

More from «Artstation» here

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

@flashfictionfridayofficial

TA 2980

"A weed is just a plant which is slightly out of place." The swordsman crouches by the spikey cloud of white flowers, reaching out to touch them with the tips of his fingers. He glances over at his companion, "It does not mean it is not something of value in its own way - so says my father."

He watches the older man's gentle reverence, how rare these tidbits of information were, "Your Father is a gardener?"

"A herb-master, and a healer." Thorongil rises to his feet, turning his face towards the sea. "That plant, Aeglos. the High Elves will leave it where it grows, even if it is right in their way."

"Because they do not want to hurt living things."

"Partly," Thorongil says with a tip of his head, But partly in remembrance to their last high king, who's spear was named after it."

"Gil-Galad, one of the leaders of the Last Alliance."

"You know your lore." Thorongil almost seems surprised as well as pleased.

"It is a part of our History, he was our king in Gondor as well as Arnor."

Indeed."

-----

3019

"I thank you, Lord Aragon, for my Nephew." Imrahil stands in the corridor of the Houses of Healing, as the healers bustle around to their tasks. "It has been a hard day indeed, but, forgive me my selfishness, I would have been heart-torn to lose Faramir."

The king dips his head "He is a good, brave man, and he will recover. For now, will you stand Steward-Regent untill he does? For the White City cannot be without a leader"

"Of course, Lord." He bows his head, silent salute.

"Raise your head, Prince of Dol Amroth," Aragorn says gently but with the same steadiness of tone that could not be denied "we have fought together, and we stand together. Perhaps one day I will be King of this land, in truth, but that must wait until this evil is vanquished." His gaze has gone distant Now I must go, help where I may, but I will be beyond your city walls before dawn." He begins to move to where Mithrandir has waited; out of mortal Man's earshot, but who knows with a Wizard.

Imrahil turns with him "Wait. Lord Aragorn, Athelas?" Lord Aragorn turns back towards him. "Lady Ioreth was right, but to many of us, it has merely been a pretty plant, a weed or a headache cure at most."

Lord Aragorn smiles a touch ""A weed is just a plant which is slightly out of place. It does not mean it is not something of value in its own way."

Imrahil feels himself go utterly still, "Someone once said those words to me before." He holds the other man's gaze, searching the face. and finds it in the slight shift of the eyes, the tip of the head. He says it simply, "Welcome back, Thorongil."

Aragorn, Thorongil's eyes seem to lose a layer of their guardedness. "Well done, Prince Imrahil - although you were not the first, Theoden King also knew me, even though he had only been a boy when I was in Rohan." The dark eyes glaze with quiet greif.

"May he ride in good fields, and sup with his Fathers, untill the world is re-made." Imrahil offers the words softly.

Aragorn, Thorongil, simply nods everso slightly, then reaches out with one hand, they clasp forearms, just for a moment. And then the man draws away, and strides up the corridor to where Mithrandir still waits.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Amroth for Gondor!" they cried. "Amroth to Faramir!"

Imrahil of Dol Amroth and Gandalf fighting the Nazgûl to bring a wounded Faramir back to Minas Tirith.

#lord of the rings#lotr#the lord of the rings#tolkien#tolkien fanart#lotr fanart#lotr books#the return of the king#faramir#imrahil of dol amroth#imrahil#gandalf#fanart#echo's drawings#i started this back in april i think#i didn't have the skills to finish it then#i'm happy to see the progress!#blood cw#injury cw

136 notes

·

View notes