#Hindu religious observances

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Why is Gayatri Jyanti celebrated Twice in a Year?

Gayatri Jayanti 2024: Date, Time, Relevance, and How to Celebrate Gayatri Jayanti is a significant festival in the Hindu calendar, dedicated to the worship of Goddess Gayatri, the personification of the Gayatri Mantra, one of the most powerful and revered mantras in Hinduism. Celebrated with devotion and spiritual fervor, this day marks the birth of Goddess Gayatri, also known as Veda Mata…

#Gayatri Jayanti 2024#Gayatri Jayanti date and time#Gayatri Jayanti rituals#Gayatri Mantra meaning#Goddess Gayatri Veda Mata#Hindu festivals 2024#Hindu religious observances#How to celebrate Gayatri Jayanti#Shravan Purnima Jyeshtha#Shukla Ekadashi Spiritual#Significance of Gayatri Jayanti#significance of Gayatri Mantra

0 notes

Text

Devotees Throng Temples as Sawan Month Begins

First Monday of Shravan sees massive turnout for Lord Shiva worship Jamshedpur temples witness overwhelming devotee influx as the auspicious month of Sawan commences, marked by fervent prayers and traditional offerings to Lord Shiva. JAMSHEDPUR – The sacred month of Sawan began on Monday, ushering in a period of intense spiritual devotion across the city. Thousands of devotees queued at local…

#जनजीवन#community spiritual practices#Hindu mythology significance#Hindu religious observances#Jamshedpur temple authorities#Life#Lord Shiva worship Jamshedpur#Sawan month begins Jamshedpur#Shravan Somvar celebrations#spiritual devotion Sawan#temple crowd management#traditional Shiva offerings

0 notes

Text

𝕴 𝔞𝔪 𝔱𝔥𝔢 𝔲𝔫𝔦𝔳𝔢𝔯𝔰𝔢 ✮⋆˙

𓇼 ⋆.˚ 𓆉 𓆝 𓆡⋆.˚ 𓇼

જ⁀➴. ݁₊ ⊹ . ݁˖ . ݁Growing up in a highly religious Hindu household I had always heard outstanding stories of gods, demons, energy, souls and the likes…and just the other day, I talked to my father’s friend, who is also a respected, inspiring and admirable Hindu priest about the theory of multiverse and he smiled, knowingly smiled, and he said ‘Aham Brahmasmi’. Which quite literally means, I am the absolute, I am the universe, the cosmos.

It blew my mind, not because I had not known or remotely heard of the concept before, I had, but hearing someone I admire and believe in so deeply say it so easily, so…effortlessly did something to my brain. I had been treating shifting like this whole big secret, a big conspiracy theory, a bigger than the sky, other worldly magic of sorts that hearing him say it oh so nonchalantly, like it was natural, I was overwhelmed with thoughts, and the more I mulled over how I am the universe, the more I knew, that I am the universe.

I thought of how in the grand tapestry of existence, everything is connected. Every universe, every cosmic possibility exists simultaneously, and there’s jivana (life) that flows through them all, binding them together. In Hindu cosmology, the idea of Yugas (ages of the world) is cyclical, ever-repeating, as if we’re living in a constant loop of creation, preservation, and dissolution. There’s no "end" in sight, just an everlasting dance of creation (and sometimes destruction, because, well... balance).

The universe in Hinduism is described as the ultimate reality, the formless, boundless, uncaptured, infinite consciousness that forms all of existence. Everything—every object, every being, every thought, emerges from it and returns to it. And when one says “Aham Brahmasmi,” they're breaking through the illusion of separation. It’s like stepping out of a dream and realizing you were the dreamer all along. It is realizing that you are the observer, the observed, and the act of observing itself.

And it is now that I do not just know it but also believe it, and it is now that I will shift, for it is now that I am shifting.

#shiftblr#reality shifting#shifting blog#shifting community#shifting realities#shifters#shifting antis dni#shifting consciousness#shifting motivation#shifting reality#reality shift#shifter#reality shifting community#shifting stories#loa motivation#loa tumblr#loablr#loassumption#loassblog#loa success#master manifestor#loa blog#loass#hindu mythology#hinduism#hindublr#astrology#astroblr#kpop shifting#universe

643 notes

·

View notes

Text

FINE since yall want an actual poll instead of a shitpost

this is a poll about COMMUNAL NORMS and CULTURAL COMMUNICATION it is not about whether you personally worship at the altar of modern science

878 notes

·

View notes

Note

You people and your obsession with monotheistic religions is what is holding us back as a species

Let's try to entertain this criticism as though it has validity.

"You people"

Let us assume that Anon means Jews.

"Obsessed with monotheistic religions"

~45% of Israelis are secular.

~30% of US Jews are secular.

Both groups still identify as Jews because they are, even if they don't observe any form of Judaism, the traditional religion of the people of Judea.

"holding us back as a species"

The accusation that “Jews are holding us back as a species” is a modern repackaging of longstanding antisemitic tropes that have historically framed Jews as impediments to progress, civilization, or moral order. This accusation came from, among others, Adolf Hitler, Henry Ford, and David Duke.

I suspect Anon incorrectly believes that the Jewish claim to Judea is based on a religious belief. It is not. Jews...are from Judea. This is why they're called Jews. The vast majority of Jews are Zionists not for religious reasons, but because they believe that they should have the right of self determination in their indigenous homeland.

While Christianity and Islam each preach that theirs is the only way to know, be loved by, or join with the divine, Jews do not share this attitude.

The religious position of Judaism towards other religions is that if they're following the Noahide laws, they're fine...and that people of other faiths are loved by God. At no time have Jews emulated the Christians and Muslims in demanding that others convert to their faith. On the contrary, Jews are forbidden to prostelytize or seek converts.

Jews have enjoyed exceptionally positive relationships with religions which do not seek to convert, wipe out, or replace Jews. Judaism is innately ecumenical in a way that the two "Abrahamic religions" which were based on parts of Judaism...are not.

But Monotheism, Anon, isn't limited to these three faiths. Other monotheistic religions include:

Zoroastrianism

Sikhism

Bábism

Baháʼí Faith

Tenrikyo

Some Hindu traditions

Yazidism

Druzism

You really think it makes sense to lump all of these together? Have you studied the theology or history of any of them? (Of course you haven't.)

I'm an atheist.

I agree with Christopher Hitchens that the net result of religion is negative for humanity.

I also agree with Hitchens that some religions are far more dangerous than others. Hitchens knew that in order to criticize religion, one needs to study and understand religions...and appreciate their enormous diversity.

Hitchens was close friends with all kinds of religious people. It is entirely possible to be an atheist without being an asshole to people of faith.

Don't take my word for it, Anon. Listen to some of the greatest atheists of the 20th and 21st centuries:

Be forthright when religion intrudes into public life, but always be polite to individuals.

- Richard Dawkins

We must find ways of criticizing beliefs without alienating people who hold them

- Sam Harris

Being intellectually honest doesn’t require being emotionally hostile

- Sam Harris

Attack the idea, not the person.

- Christopher Hitchens

Don’t condescend, don’t misrepresent—but don’t be silent either.

- Daniel Dennett

For small creatures such as we, the vastness is bearable only through love.

- Carl Sagan

I have a great deal of respect for the Jewish tradition of moral seriousness and intellectual inquiry.

-Christopher Hitchens

I am a partisan of the Jews, even if I am not one. Without them, there would be no concept of conscience.

- Christopher Hitchens

If I had to give up all other identities, I would probably keep Jewishness. Not the religion—I am an anti-theist—but the culture, the history, the resistance, the humor.

-Christopher Hitchens

The Jewish emphasis on education and argument is something I deeply admire, even if I don’t share the theology

- Richard Dawkins

Judaism has had the virtue of being more self-critical and less dogmatic than many other faiths

- Sam Harris

My Jewish heritage taught me to cherish learning, to ask questions, and to be skeptical of easy answers. These are the same values that guide science.

- Carl Sagan

Jews have contributed vastly to the Enlightenment, science, and modernity—not in spite of Judaism, but through cultural values Judaism long upheld: learning, debate, and moral responsibility.

- Steven Pinker

Anon hasn't read any of these thinkers. Anon is an edgy young atheist who believes that his atheisim justifies behaving like an asshole towards strangers in general...and Jews in particular.

And none of the atheists above share his views.

I hope he'll read more and grow a bit.

If you want reading suggestions, Anon, to help you learn enough about relgiions to criticize them intelligently, my Asks are open.

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Genshin Character Names` Meanings Pt. 4

Tighnari | Most likely a reference to Arab Muslim botanist (as well as traveler, poet and physician) Al-Tighnari (born in village Tignar), who wrote a treatise on Middle East agriculture

Collei | Uncertain, but there seemingly is a Persian name Collei that means «Aware», «Sentimental», or «Noble»; Also literally «Lost» in Welsh

Cyno | Originates from Cynopolis, an Egyptian city which used to be centre of Anubis cult, and as we all know, Cyno is based on Anubis

Sethos | Most likely references Seth, the God of deserts, storms, disorder, violence and foreigners in Ancient Egypt. Known to have accompanied Ra on his barque in repelling Apep, but in the Osiris myth depicted as the usurper who murdered and mutilated his own brother, who is Osiris himself

Dori | Literally «Shining», «Glowing» in Persian, also derived from the word dor (دُر) which means «Large Pearl»

Nilou | «Water Lily», «Lotus» – Persian Name

Candace | «Clarity», «Whiteness» – An ancient title derived from word Kandake, once used by queens of Ethiopia; has Latin roots

Dehya | «Leader of Soldiers» – Algerian Amazeigh/Berber name, which refers to Kahina Dehya, the female Algerian priestess, who was a religious and military leader

Layla | Literally «Night» in Arabic

Faruzan | «Luminous», «Shining», or «Resplendent» – Persian Name

Alhaitham | Haitham is a first name and it means «Young Eagle» or «Young Hawk». Meanwhile Al is a prefix usually used in Middle East last names before the name of the family/tribe itself. Basically, it is a definite article, like 'the' in English. He is also most likely named so after Hasan Ibn al-Haitham (Latinicized version of his name also sounds like Alhazen) who was an Arab mathematician, astronomer and physicist during the Islamic Golden Age

Kaveh | «Of Royal Origin» – Persian/Iranian Name; Might be based on Kaveh the Blacksmith from Iranian mythology, who launched a national uprising against the evil foreign tyrant Zahāk and re-established the rule of Iranians

Nahida | «Delightful», «Gentle», «Kind», «Soft» – Persian Name. Another version – Nahiya, means «Advisor»

Kusanali | Derived from the Pali words «kusa» (kusa-grass, a sacred plant used in Hindu ceremonies) and «nāḷi» («a hollow stalk or tube»).

Buer | Comes from Governor Buer, the 10th of Goetia Demons

Rukkhadevata | रुक्खदेवता – "tree-goddess" in Shaivism is a Yakṣiṇī who is worshiped as the goddess of wealth or the guardian spirit of practitioners. The Yakṣiṇīs are the female counterparts of the Yakshas in Hinduism and Buddhism, and also appear in Jātaka literature, where they are considered as local deities living in trees and sometimes referred to individually as "rukkha-devatā".

Cuilein-Anbar | Literally «Darling Amber». Cuilein (directly translating to «pup/cub») is a Gaelic term of endearment commonly used for young animals, equivalent to «darling», while anbar is an Arabic word meaning «amber».

Mehrak | «Like the Sun» – Persian Name

Faranak | Derived from the word پروانه (parvâneh), which means «butterfly» in Persian

Dunyarzad | Likely named so after Dunyazad (دنیازاد in Persian), who is the younger sister of Queen Scheherazade from One Thousand and One Nights

Sorush | Originates from Zoroastrian divinity of «Conscience» and «Observance», with its name having those two exact meanings

Apep | Based on an ancient Egyptian deity of darkness and disorder, also known as Aphoph or Apophis, who also was often depicted as a snake

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

........Hi

Not even gonna make up excuses this time, just want you to know that I do have an intention to finish these series, it`s just that God knows when I actually will

In any case, I wanted to add Jeht as well, but I couldn't find a reliable source that would tell me where her names comes from, so I would be grateful if anyone knowledgeable helped me out here. I think I saw a version that says it's an Arabic name meaning «Freedom Lover» or «Scholar», but I'm not sure if that's right??

Anyways, see ya soon, hope you'll have a great year, take care of yourself, stay hydrated and bye.

#genshin impact#genshin impact sumeru#tighnari#collei#genshin impact cyno#cyno#genshin impact dori#nilou#candace#genshin impact layla#faruzan#alhaitham#kaveh#dehya#genshin impact sethos#genshin impact nahida#nahida#greater lord rukkhadevata#genshin impact sorush

109 notes

·

View notes

Note

“This woman prayed and her cancer was cured”

“That miracle only happened to one person, it’s way too small, is God asleep at the wheel or something?”

“Thousands of people saw another miracle”

“Well, that was probably mass hysteria”

What would be a hypothetical miracle which you would accept?

approximately ten million people die of cancer each year, so prayer appears to be an ineffective intervention in general and we don't see a significant difference in remissions between Catholic or Protestant or Muslim or Hindu patients as far as I'm aware, but we have seen dramatic improvements in outcomes for some cancers due to our understanding of the condition and development of new treatments, suggesting that scientific research saves lives and prayer does not (reinforced during the covid pandemic with the creation of new RNA vaccines while many religious leaders were still urging people to meet communally and give the virus to each other and trust in god).

far more people have seen UFOs than Catholic miracles and I believe these can be analysed in a similar manner.

there are so many miracles that would actually be convincing! but if they were observed and confirmed then they wouldn't be miracles would they, the key aspect of a miracle is that it needs to be a rumour, improbable, unverifiable, something that demands faith without evidence, to confirm a belief already strongly held; a real miracle would convince me, but ironically wouldn't be very interesting to the religious (NASA putting Jesus in the wind tunnel to see how he manages to ascend through the air without being torn apart by aerodynamic forces).

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maha Shivratri - Lord Shiva ॐ Talon Abraxas Shivratri: Rituals, Spiritual Benefits & Personal Transformation The Most Powerful Night for Transformation

Shivratri, which falls on February 26th this year, is considered the most powerful night for spiritual transformation. It is not just a religious festival, but an opportunity to elevate one’s consciousness and align with the divine energy that sustains the universe. This sacred night is believed to be when the cosmic energy is at its peak, providing the ideal conditions for meditation, chanting, and purification.

The night holds immense significance as it allows us to dissolve old negative patterns, purify our energy, and invite divine blessings into our lives. In this article, I will take you through the deeper meaning behind Shivratri, its spiritual essence, and powerful rituals that can help you experience profound personal transformation.

The Deeper Meaning of Shivratri

Mahashivratri, meaning “The Great Night of Shiva,” is one of the most spiritually significant nights in the Hindu calendar. It is observed on the fourteenth day of every lunar month, a day before the new moon. However, among the twelve Shivratris that occur in a year, the one that falls between February and March is regarded as the most auspicious and sacred.

Shivratri,marks the union of Shiva (consciousness) and Shakti (energy). This sacred night represents the merging of the two fundamental forces that govern existence—consciousness and energy. It is also believed to be the time when Lord Shiva performed the Tandava, the cosmic dance symbolizing creation, preservation, and dissolution.

This night is unique due to a natural cosmic alignment that facilitates an upsurge of energy within the human system. The northern hemisphere of the Earth is positioned in such a way that this natural energy pushes individuals toward their spiritual peak.

Shiva as a Symbol of Inner Transformation

Shiva is more than a deity—he is the embodiment of the cosmic energy that resides within all of us. The essence of Shiva teaches us profound life lessons: Destruction of Ego, Attachment, and Ignorance: Letting go of what no longer serves us to create space for spiritual growth. Breaking Negative Cycles: Breaking free from old, limiting patterns to make room for new beginnings. Self-Realization: Recognizing the true self beyond the material realm.

Shiva’s presence encourages us to transcend ego and attachment, thus guiding us toward spiritual freedom.

Benefits of Observing Shivratri Mental Clarity: Fasting, chanting, and meditation clear the mind, enhance focus, and help us live with purpose and direction. Emotional Healing: Shivratri’s sacred energy releases negative emotions, fostering emotional resilience and self-compassion. Spiritual Growth: This auspicious night strengthens our connection with the divine, deepens meditation, and awakens our inner energy. Prosperity and Well-being: Devotees are blessed with health, success, and abundance by aligning with Lord Shiva’s energy. Personal Transformation: Through devotion and reflection, Shivratri opens the door to self-transformation, releasing ego and inviting higher wisdom. Shiva Mantras – Transformative Chanting

Chanting mantras on Shivratri is one of the most powerful spiritual practices.

The Most Powerful Mantra: Om Namah Shivaya (ॐ नमः शिवाय ||) – “I bow to the Supreme Consciousness.” This mantra is a potent tool for connecting with Shiva’s energy and experiencing transformation.

There are several other powerful mantras that deepen our spiritual connection with Lord Shiva and bring profound transformation. Here are a few more to include in your practice: Mahamrityunjaya Mantra:

ॐ त्र्यम्बकं यजामहे सुगन्धिं पुष्टिवर्धनम् |

उर्वारुकमिव बन्धनान् मृत्योर्मुक्षीय मामृतात् ॥

Om Tryambakam Yajamahe Sugandhim Pushti Vardhanam

Urvarukamiva Bandhanan Mrityor Mukshiya Maamritat

Meaning: “We worship the Three-Eyed One, Who is fragrant and nourishing. May we be liberated from the bonds of death and experience immortality.”

Chanting this powerful mantra instills strength and courage in those feeling vulnerable, empowering them with clarity and resilience to overcome challenges. Shiva Rudra Mantra:

ॐ नमो भगवते रूद्राय।

Om Namo Bhagwate Rudraay

Meaning: “I bow to the glorious Lord Rudra.”

The Rudra Mantra is chanted to invoke the blessings of Lord Shiva, who is also known as Rudra. Reciting this powerful mantra is believed to fulfill one’s desires, as Lord Shiva is considered the most compassionate and easily appeased deity in Hinduism. Shiva Gayatri Mantra

ॐ तत्पुरुषाय विद्महे महादेवाय धीमहि तन्नो रुद्रः प्रचोदयात ।

Om Tatpurushaya Vidmahe Mahadevaya Deemahi Tanno Rudrah Prachodayat

Meaning – Om, Let me meditate on the great Purusha, Oh, greatest God, give me higher intellect, and let God Rudra illuminate my mind.

Chanting the Shiva Gayatri Mantra is highly beneficial for attaining inner peace, as it calms a restless mind and brings stability. It also aids in gaining control over one’s senses, ultimately helping to master and govern the mind.

These mantras, when recited with devotion, not only deepen our connection to Shiva but also invite divine blessings, clarity, and healing into our lives.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kuja Dosha—Mars Affliction

Hey friends! I wanted to dig deeper into the significance of Kuja Dosha. Understanding your Mars placement is incredibly important, but also, how Mars on a bigger level plays into violent themes. I also want to take the time to explain Kuja Dosha in a historical context and cultural/religious. With all due respect these are observations from studies, and should not always be taken literally. Take it with a grain of salt.

This post can get heavy, so TW: Mentions of sexual abuse, concerning children, murders, death, kidnapping. I only ever include this to help raise awareness and astrology is a privilege--not a means to an end to justify anything. I also want to add I'll be adding in western astrology because I think it has helpful information to understand Mars itself here. There are similarities.

Kuja Dosha and why it is significant:

Kuja Dosha in Vedic astrology refers to the Mars placement being very active which includes several aspects and placements to diagnose this. Although these placements are sometimes viewed in a neutral light and even positive in western astrology, Vedic places the emphasis here that Mars signifies deep issues in a natives chart. This is not to say every Mars placement is considered Kuja Dosha. There must be strong aspects/placements to signify this.

Kuja Dosha is important to identify in a natives chart especially, because it can describe the lifestyle the native will experience, create, or struggle with. It can also speak of the past life the native experienced (if you believe in that) and what legacy, or experiences they are taking into this lifetime. It also signifies sexual abuse, misuse of power by authorities, parents, anyone who is considered authority. Often in a childs natives chart, looking to the Mars can help describe such violent acts done behind closed doors. It can also signify issues in relationships and marriage.

You can still have relationship issues without the influence of Kuja Dosha, and experience issues and losses. For example a malefic sun, Rahu/Ketu influence, and Saturn can cause delays and problems.

Moving onto a historical/religious understanding of this system, yes, it was a way to protect women in Hindu culture. Despite Mars' affliction in the charts, astrologers looked after women with Kuja Dosha realizing the system and men would most likely target them. So, by honoring the women, the astrologer made sure both partners had Kuja Dosha to nullify its effects, and both understood how to mitigate it by prayers and such. The brides family would be warned to hold on marriage as well, especially if the Kuja Dosha was strong. This was for the brides well-being. You might ask why the bride? Because Kuja Dosha affects primarily marriage, and relationships for the female, and it manifests differently based on gender. Men with Kuja Dosha were often perpetrators of abuse with Kuja Dosha.

And because of this highlight in charts, men were closely looked at in families to see their temperament if they'd hurt the bride who carried Kuja Dosha. So, to prevent early death, sudden sickness, and abuse of the bride, astrologers looked closely in both the spouses chart for compatibility if they should marry or not.

Mars Placement:

You must have Mars in the 1st, 2h, 4h, 7h, 8h, and 12h to suggest Kuja Dosha, but it not enough to say how strong Kuja Dosha is. Aspects, and reinforcements from the other planets to the 4h/12h/7/1h/8h/2h is very important here.

I would like to add: Kuja Dosha can also represent the failure of the system against women. Children especially. It involves the failure and mishandling of the patriarch system.

Mars 1h: Often in western astrology , this is described as the native experiencing a devastating loss or injury of the body. Mostly the legs, but not limited to. It is similar to Vedic as well. If Mars 1h is making an aspect to the 8h house which is considered harmful in Vedic, especially if it is a (square, opposition) the native can experience sudden mental/physical sickness, loss of money/status, objectification and sexualization at a young age. This is also an indicator to astrologers that the natives lifetime can be cut short. Mars 1h can be combative, fight in marriage, and defensiveness either from the native itself or both spouses (synastry is needed to see how both mars interact)

Mars 2h: This can create communication issues, either from the native, family members and partners. Abusive language can be used. This is more of a western astro take, but 2h is related to self esteem. The natives self esteem is especially harmed, boundaries are trespassed by those they could have trusted. Especially at a younger age trauma could have taken place. This can create a personality primed for abuse, if the native does not seek therapy and recovery. This can cause financial issues as well.

Mars 4h: Emotionally aggressive native but depends on the aspects. The native can be closed off to marriage, family life, and find ways to sabotage union. The native can become manipulative, or experience manipulation by others depending on mercury's positioning. For example, mars 4h square Saturn could have experienced turmoil in their own childhood. If Mars positively aspects a benefic like Mercury, it can bring a balanced, harmonious native in communication with their partner, despite the Kuja Dosha present. If the mercury is in detriment, fall, or negatively aspected, the native can express themselves aggressively, or shut down, only adding strength to the Kuja Dosha. Because Saturn already brings more tension. The mars native may not understand healthy family dynamics. Thus, the native is prone to anger and volatile behaviors.

Mars 7h: Mars here can create issues with in-laws and family members. This can represent either the native, or spouse using violence to control one another if negatively aspected. Intimidation tactics can be used. The native or spouse may enjoy a dramatic display depending what sign the house falls in, and aspects. Or this can continue behind closed doors for years with Saturns influence, Capricorn/Aquarius, Rahu/Ketu (NN, SN) It can also suggest divorce. Mars in the 7h is also called Maraka, because this is the house Mars dies in. Mars does not function well here, according to Vedic astrology and causes serious implications. This creates division as Mars wants to be alone, but since Maraka is at work here, this can also signify the native struggles with codependency. It strips the native of his or her own boundaries.

Mars 12h: This can create financial stress, and internal instability. This stress is more so internal and the process the native goes through to heal and struggle is often done in isolation, or privacy. If a native child carries this placement with strong Kuja Dosha, it can mean the parents pressure the child to keep silent about their struggles, thus making them carry this stress internally. This can unfold negatively, if Mars is not aspected properly or enough. Meaning, Mars may have one aspect or none, thus making the energy volatile and combustive. This can land the native in psych hospitals, prison, and they are prone to addiction. And still, this can happen if Mars has a lot of negative aspects too.

If mars is negatively aspected in the houses above, it can signify a misuse of power by the parents especially the father. If the house mars falls in is Cancer, Scorpio, Aquarius, Taurus, or arguably Leo, it is not good. The father figure/authority figure/s is more likely to hide and not admit to such crimes. Mars in cancer is in a fall state, which weakens the morality of the authority figures, and makes them cowardly. Mars in Taurus is in detriment, and often the native is used like a possession, or a way to gain fame, recognition, or money. While Mars in Aquarius often points to the authority figure displaying a wolf in sheep's clothing behavior, behaving morally just in front the camera. Scorpio represents the power imbalance with authority, stripping the native of choices and freedom. Leo represents power, greed, pride hidden behind family doors and could explain the native being used for publicity, and exploitation. Leo can suggest sexualization, and objectification. Often times, Leo can signify the authority figure/s making it look as if there is a happy home, hiding dark secrets.

In Vedic, we can take this way of thinking as well: if there is an imbalance with the 1h and 8h, and the 8h has a stronger presence can indicate sickness, struggles and endings.

For example: Scorpio rising, weakly aspected in the 1h, and Mars conj. Jupiter 8h in detriment. Even though Jupiter is seen as good luck here at first glance, its effects become very weak in the 8h. Mars is also in Kuja Dosha, and instead of Jupiter helping, it is in detriment because of the sign. Therefore, Jupiter can't help mitigate Mars malefic energy the way it should. The 8h is stronger than the effects of the 1h.

However, Mars gets nullified or weakened if:

Mars 12h/4h/8h/7h/2h is in positive contact with Venus, moon, Jupiter and Mercury, and the benefics itself are well supported. Mars is about to exit out of the 1h, 4h, 7h, 8h, 12h so check the degrees.

If you have a benefic touching Mars, even though Mars itself has another harsh aspect, this balances the Kuja Dosha.

If both partners have Kuja Dosha it gets mitigated.

It is important to check all contact with Mars. Check the aspects, which planets are affecting it, houses, and signs. Check the benefics that make contact to your Mars, its ruler and which house it lands if its detriment/fall this will affect the strength of Mars.

There is another rule that Mars in its own Taurus/Libra is considered harmless, or weak, however, studying charts I realized this is not always the case. Especially when Rahu/Ketu is conj. Mars, or Saturn is aspecting Mars 12h, 1h, 7h, 2h, 4h, 8h it can bring violent implications, sickness, and trauma. Even if you have the presence of Venusian ruled signs, this is not enough to mitigate Mars strength and power simply.

Even if Jupiter 8h/12h/1h/2h/4h/7h is where Mars is, this can be considered “good luck,” but this is not always the case. First, there is Kuja Dosha present in the house of money, wealth (2h) and Jupiter can be mistaken for wealth here. If Jupiter is negatively aspected, in detriment/fall, it can bring issues, and not necessarily bring empowerment, wealth, or money, even though Jupiter is considered the protector.

Jupiter is known for mitigating malefic energy when sitting in the same house as Mars or malefics, even without forming direct contact with Mars or malefics. But since Jupiter is weak in the example above, Mars gets the upper hand bringing financial stress and issues in family. Same rule applies with the Moon, Venus, Mercury if placed in the houses listed above.

Another example of this, is when Mars sits in the 7h suggesting Kuja Dosha. Upon closer look, we understand this is actually amplified because Saturn is square Mars 7h, bringing separation, distance, and coldness in the approach to relationships, or partners being cold. Saturn is malefic as well. This can bring unjust behavior from the court in legal proceedings, and unfairness. The native can be shunned by the law, even though they are innocent. The law can also be cold, ruthless, and deny bail or probation. Instead of the native being heard they are dismissed. The law can favor the perpetrator instead, because of Mars strength and influence.

In the D9 chart, Mars 8h/12h/1h/2h/4h/7h also points to a very strong Kuja Dosha, reinforcing what was seen in the natal chart.

This is more of western take, but Mars 8h aspecting only Uranus becomes very unstable, difficult and hard for the native. Mars energy is heavily unbalanced and has no support of benefics. This energy is particularly tense when squared, giving a volatile, impulsive and reckless nature to the native person. This can also describe mental anguish, and life experiences that deeply hurt the native.

Another western take, Uranus 8h can signify even greater issues, even when retrograde. It can signify sudden changes, death, loss of a loved one, or suggest darker themes of childhood like kidnapping or disappearances.

That being said, if the benefics are well aspected in the 12h/1h/2h/4h/7h/8h, there is a much better chance of the native succeeding. (Given that the 1h is not weak, and benefics rulers are well placed and aspected well) So, always check the strength of the placements.

Another thing to takeaway, Kuja Dosha never works in isolation. It's not enough to look at a Mars 12h, Mars 8h and say that is Kuja Dosha. It can suggest a need for a deeper look, but depending on the other placements, aspects, this can either uplift Mars or add to the mayhem. Lots of us have mars aspects and so, not everyone will have Kuja Dosha.

Thank you for reading friends! Do let me know if this was informative and your thoughts or opinions :) I'm open to hearing as long as it is respectful and open minded.

#astrology community#astrology#devi post#tarotcommunity#divination#tarot deck#tarot#witchcraft#tarot reading#astrology notes#astro notes#esoteric astrology#astro#astro observations#18+ astrology#astrology post#asteroid glo#astro placements#astro posts#solar return astrology#astro community#astroblr#tarot witch#tarotdaily#daily tarot#tarot readings#pick a pile

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Devotion

Monday - April 21, 2025

During April 2025 the Hindu, Jewish, Christian, Sikh and Baháʼí faiths are celebrating significant "holy days" and religious observances. I love these days when you see religious devotees celebrate their faith.

For many years I have celebrated Good Friday with my own Ceremony and time of meditation. This year I did not. I allowed work and other obligations to interfere. It bothered me all weekend that I allowed such things to get in the way of something that deep inside I am devoted to. The pain of how casually I let the world interfere bothers me even as I type this post.

That won't happen again. I have learned a great lesson courtesy of the Old Wise Teacher .... Saturn.

Today Saturn conjuncts the North Node in Pisces at 26°, a degree it rules; a degree that asks you to commit, and if able, to devote. In Pisces it is to devote to your highest spiritual expression, and to know WHY you are devoting to it. And conjuncting the North Node it means committing/devoting in ways you haven't before.

I learned my lesson, and I'm grateful for it. Devotion requires something more than your heart, but your time as well. FYI ... Saturn is the ruler of time as well. Ask yourself today what are you not making time for, or devoting to, that deep down inside you "say" you are committed to.

You may end up seeing that your actions and heart are not exactly aligned.

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Upanishads

The Upanishads are the philosophical-religious texts of Hinduism (also known as Sanatan Dharma meaning “Eternal Order” or “Eternal Path”) which develop and explain the fundamental tenets of the religion. The name is translated as to “sit down closely” as one would to listen attentively to instruction by a teacher or other authority figure.

At the same time, Upanishad has also been interpreted to mean “secret teaching” or “revealing underlying truth”. The truths addressed are the concepts expressed in the religious texts known as the Vedas which orthodox Hindus consider the revealed knowledge of creation and the operation of the universe.

The word veda means “knowledge” and the four Vedas are thought to express the fundamental knowledge of human existence. These works are considered Shruti in Hinduism meaning “what is heard” as they are thought to have emanated from the vibrations of the universe and heard by the sages who composed them orally before they were written down between c. 1500 - c. 500 BCE. The Upanishads are considered the “end of the Vedas” (Vedanta) in that they expand upon, explain, and develop the Vedic concepts through narrative dialogues and, in so doing, encourage one to engage with said concepts on a personal, spiritual level.

There are between 180-200 Upanishads but the best known are the 13 which are embedded in the four Vedas known as:

Rig Veda

Sama Veda

Yajur Veda

Atharva Veda

The Rig Veda is the oldest and the Sama Veda and Yajur Veda draw from it directly while the Atharva Veda takes a different course. All four, however, maintain the same vision, and the Upanishads for each of these address the themes and concepts expressed. The 13 Upanishads are:

Brhadaranyaka Upanishad

Chandogya Upanishad

Taittiriya Upanishad

Aitareya Upanishad

Kausitaki Upanishad

Kena Upanishad

Katha Upanishad

Isha Upanishad

Svetasvatara Upanishad

Mundaka Upanishad

Prashna Upanishad

Maitri Upanishad

Mandukya Upanishad

Their origin and dating are considered unknown by some schools of thought but, generally, their composition is dated to between c. 800 - c. 500 BCE for the first six (Brhadaranyaka to Kena) with later dates for the last seven (Katha to Mandukya). Some are attributed to a given sage while others are anonymous. Many orthodox Hindus, however, regard the Upanishads, like the Vedas, as Shruti and believe they have always existed. In this view, the works were not so much composed as received and recorded.

The Upanishads deal with ritual observance and the individual's place in the universe and, in doing so, develop the fundamental concepts of the Supreme Over Soul (God) known as Brahman (who both created and is the universe) and that of the Atman, the individual's higher self, whose goal in life is union with Brahman. These works defined, and continue to define, the essential tenets of Hinduism but the earliest of them would also influence the development of Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism, and, after their translation to European languages in the 19th century CE, philosophical thought around the world.

Early Development

There are two differing claims regarding the origin of Vedic thought. One claims that it was developed in the Indus Valley by the people of the Harappan Civilization (c. 7000-600 BCE). Their religious concepts were then exported to Central Asia and returned later (c. 3000 BCE) during the so-called Indo-Aryan Migration. The second school of thought, more commonly accepted, is that the religious concepts were developed in Central Asia by the people who referred to themselves as Aryans (meaning “noble” or “free” and having nothing to do with race) who then migrated to the Indus Valley, merged their beliefs and culture with the indigenous people, and developed the religion which would become Sanatan Dharma. The term 'Hinduism' is an exonym (a name given by others to a concept, practice, people, or place) from the Persians who referred to the peoples living across the Indus River as Sindus.

The second claim has wider scholarly support because proponents are able to cite similarities between the early religious beliefs of the Indo-Iranians (who settled in the region of modern-day Iran) and the Indo-Aryans who migrated to the Indus Valley. These two groups are thought to have initially been part of a larger nomadic group which then separated toward different destinations.

Whichever claim one supports, the religious concepts expressed by the Vedas were maintained by oral tradition until they were written down during the so-called Vedic Period of c. 1500 - c. 500 BCE in the Indo-Aryan language of Sanskrit. The central texts of the Vedas themselves, as noted, are understood to be the received messages of the Universe, but embedded in them are practical measures for living a life in harmony with the order the Universe revealed. The texts which deal with this aspect, which are also considered Shruti by orthodox Hindus, are:

Aranyakas – rituals and observances

Brahmanas – commentaries on the rituals

Samhitas – benedictions, mantras, prayers

Upanishads – philosophical dialogues in narrative form

Taken together, the Vedas present a unified vision of the Eternal Order revealed by the Universe and how one is supposed to live in it. This vision was developed through the school of thought known as Brahmanism which recognized the many gods of the Hindu pantheon as aspects of a single God – Brahman – who both caused and was the Universe. Brahmanism would eventually develop into what is known as Classical Hinduism, and the Upanishads are the written record of the development of Hindu philosophical thought.

Continue reading...

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

An endorsement of Dropout's Dimension 20 calendars, for less obvious reasons:

1) Wirebound for easier flipping to the new month, and printed on something like card stock you can actually write on. No thin and glossy paper sheets to be found here.

2) Do you forget to flip the calendar when a new months starts in the middle of a week? NOT ANYMORE. Each "month" is allotted 5 weeks of space. What would be BLANK spaces in an 'average' calendar is marked with the dates of the surrounding months, so you have the full week at a glance even before flipping.

For example, January 2025 starts on a Wednesday, so the first Sunday through Tuesday indicate December 29-31. January itself ends on Friday the 31st, so the last Saturday on the January page is February 1.

3) Inclusive Holidays! These vary from religious and cultural observances (including but not limited to Jewish, Hindu, and Muslim) to commemmorating notable figures. Solstices and equinoxes are marked, as well as monthly celebrations for heritage and cultural awareness. They even took the time to mark when a date is "tentative" for a particular celebration, rather than leave it out entirely from the printing.

4) Deep Cuts: Only a couple of them, but there are some dates based on Dropout content (like when Kingston Brown made pancakes)

5) You get an EXTRA month (with extra art)! Just in case you didn't grab a new calendar before the new year: the 2024 calendar includes the month of January 2025, and same for 2025's with January 2026.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'd like to try to clear up chronic (sometimes willful) misunderstandings about the words "goy" and "goyim."

I think the confusion is mostly from the assumptions of cultural Christians and cultural Muslims that Jewish culture shares Christian/Muslim views of other religions - so most of this is about how each of those religious traditions regards peoples of other faiths.

(Jews, Christians, Muslims - I'd welcome comments if I have misrepresented facts about Christian or Muslim belief/history and would welcome elaborating comments)

(TLDR version: Christians and Muslims sometimes assume "goy" is derisive because "infidel" and "kafir", their terms for those who don't share their faith, are derisive.)

Where does "goy" or "goyim" come from?

In the Torah (the first four books of what Christians call The Old Testament), in the book of Bereshit (בְּרֵאשִׁית), which Christians call Genesis, appears the first known written use of the Hebrew word for "nations," and that word is "goyim."

The first recorded usage of goyim occurs in Genesis 10:5 and applies to non-Israelite nations. The first mention of goy in relation to the Israelites comes in Genesis 12:2, when God promises Abraham that his descendants will form a goy gadol ("great nation")

If you like, you can see many translations of what Christians call Genesis 10:5 here.

You'll see that translators to English sometimes translate "goy" as "gentile," a word which comes from Latin and describes someone outside of one's own tribe/clan/nation. To me, that's often not a particularly bothersome translation. (I'm trying to be mindful of my own biases as a GenX USAmerican who has lived in the diaspora his entire life. I think most of my generation of US Jews was taught that "gentile" was an inoffensive word to describe non-Jews in most contexts.)

Other Christian translations, however, sometimes translate goy/goyim as "heathen"/"heathens," which does not generally align with Jewish thinking about other faiths. So for this to make sense we need to touch briefly on how Jewish thought views Jews and how it other religions.

Okay, how do Jews regard themselves in relation to other peoples and religions?

You've probably heard that Jews call themselves "The Chosen People," and you've almost certainly heard misinformation/disinformation about what that means. You've probably seen it suggested that Judaism regards Jews as superior to non-Jews. This 100% false assertion is profoundly dangerous. There is no Jewish supremacy in Judaism.

What being Chosen means to religious Jews is that Jewish people have a covenant with God which requires of them special responsibilities which other peoples are not obliged to observe. Religious Jews believe God chose the Jews to obey the commandments of the Torah, and that the Jews, in turn, chose the Torah. These resulting special responsibilities do not make the Jews more loved by God than other peoples and they do not privilege Jews over other peoples.

Jewish thought explicitly regards peoples/faiths which share the values of the Noahide laws as "rightious." Roughly, these are the Noahide laws:

Don't worship idols (worship God only)

Don't curse God (don't desecrate the holy)

Don't commit murder

Don't commit adultery or incest

Don't steal

Don't eat flesh torn from a living animal (animal cruelty is bad)

Establish courts of justice

These values are nearly universal among the world's major religions. Christianity and Islam share these values.

Sidebar: One could certainly argue that religious Jews might prefer the Muslim prohibition of visual idols to what looks in Hinduism (to religious and uninformed Jewish eyes) like rampant idolotry, but any serious study of incredibly complex and varied Hindu practices reveals that Hinduism is certainly not idolotry when seen from inside its own belief system.

So the broadly held view of the overwhelming majority of the world's Jews is that God loves non-Jews and regards them as rightious if they are ethical and moral in how they interact with other human beings. They are Chassiddei Umot ha-Olam, pious people of the world. The Jewish word for non-Jews simply means "other peoples of earth" or "non-Jews." Theres no judgment or condemnation in it. There's no Jewish drive to make the world Jewish, to convert non-Jews to Judaism, or to condemn people of other faiths for being something other than Jewish. Such behaviors are forbidden. (I'd like to note here that I have seen video of ultra-orthodox haredi in Israel insulting and spitting on Christians. This is wrong, upsetting, and disgusting. Most Israelis and most Jews condemn such behavior. All fundamentalist movements, in my view, suck, including such haredi. They represent Jews as much as the Westboro Baptist Church represents Christians.)

Okay, but aren't Christians also okay with other religions?

Many forms of Christianity require Christians to proselytize, to "spread the good news" and to convert non-Christians to Christianity whenever possible. Many kinds of Christianity regard this as the greatest of good deeds, because non-Christians are doomed to the eternal torment of Hell, so if they offend a non-Christian with their efforts to convert, it's for the non-Christian's own good. In some places and times, conversion to Christianity was forced. (A huge topic for another time.) Generally, Christianity regards other religions as false and wrong, even if they are pro social, share similar values, and are not a threat to Christianity. Non-Christians (including the Jews from whom Christians drew their monotheism, Muslims who share their monotheism, and competing Christian movements) have been referred to by Christians as unbelievers and infidels.

Where "goy" simply means "non-Jew," "Infidel" does not simply mean "non-Christian." It is unquestionably a judgement and a condemnation.

How do Muslims regard other faiths?

In the same way that most Christians believe that faith in their Christ is the only way to attain the kingdom of heaven, polls show that a majority of Muslims worldwide believe that Islam is the only path to heaven.

Muslims say that Islam is the only religion that leads to eternal life in heaven in most countries surveyed in the Middle East and North Africa, including Egypt (96%), Jordan (96%), Iraq (95%), Morocco (94%) and the Palestinian territories (89%). Somewhat smaller majorities take this view in Lebanon (66%) and Tunisia (72%).

Muslim culture has its own specialized word for non-Muslims, "kafir." The Quran uses the word to describe early polytheistic antagonists of the Islamic movement and some verses stress the difference between kafir which are hostile to Islam and kafir who are not. Later, the word was used for any non-Muslim and became derisive.

In 2019, Nahdlatul Ulama, a large organization of Indonesian Sunni Muslims, called for their co-religionists worldwide to cease using the word.

“When someone calls you a kafir, that means you’re considered someone who is godless,” said Alex Arifianto, an Indonesian political scientist with the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore.

“Or you’re someone whose religion is considered inferior to the Islamic belief,” he said. “That’s why this is so significant. The largest Muslim organization in the world is saying, ‘Look, we have to treat non-Muslims as equals.’”

So if "goy" simply means "non-Jew" without condemnation or judgment, why are so many Christians and Muslims ready to believe that the word is derisive?

Bluntly, it's because the Christian and Muslim words for those who do not share their faith (Infidel and kafir) are derisive, are judgemental, and are condemning. Cultural Christians and Cultural Muslims assume that these elements of their faith and culture have clear analogs in Jewish thought. Here's the thing: They don't.

You're saying that Jews have never used "goy," "goyim," or "goyishe" derisively?

Absolutely not! I can't and won't pretend that theres no tribalistic bigotry in Jewish history. Jews learned over the last 2000 years to expect better and fairer treatment from other Jews than they'd expect from gentiles, and that shows up in language. "Goy" has unquestionably been used derisively. One of my Yiddish-speaking grandparents said that a "goyishe kop" (gentile head) was someone who didn't think ahead, or who lacked compassion, and that's undoubtedly a derisive use. It's beyond question that "goy" can be used derisively, I'm only arguing that this is the exception, not the rule.

(In the only Jewish nation on earth, the political, social, legal, and religious freedoms of the 20% of Israeli citizens are not Jewish...are identical to the rights of Jewish citizens- because that's a Jewish value.)

As for me, I don't use "goy" in mixed Jewish/gentile company because I live in a very pluralistic society and do not wish to inadvertently give offense, even if that offense is rooted in someone else's misunderstanding of my heritage. That's my choice.

At the same time, I have not with my own ears ever heard a Jew I know use the word derisively.

Your mileage may vary, your practices may vary, your experiences may vary. I have lived my entire life as a 2% minority in a majority Christian country where diasporan Jewish culture evolved to take pains to avoid insulting the majority and that is not a universal Jewish experience.

The hill I'll die on here is that unlike in Christian and Islamic thought, Jews do not regard the people of other faiths as inferior, wrong, broken, or in need of rescue.

Jews do not attempt to convince goyim to become Jews, Jews do not preach to gentiles from Jewish scripture or attempt to force them to pray as Jews pray. Jews do not believe that goyim are cursed, doomed, or unloved by God.

Those are Christian and Muslim takes on Infidels and Kuffaar, not Jewish takes on goyim.

Lastly, please know this: Christianity and Islam both took their basis from Judaism, but discarded many fundamental Jewish values.

The disrespect, condemnation, disparagement and disenfranchisement which Muslim and Christian nations and cultures have inflicted on those they called(/call) Infidels and Kuffaar were not derived from their Jewish origins.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wishing you a blessed Maha Shivratri! May Lord Shiva’s divine energy fill your life with peace, prosperity, and happiness. Om Namah Shivaya! Shivratri - Great Night of Shiva ॐ

Celebrate Shivratri 2025 on 26th February, Wednesday Welcome to the ultimate destination of Shivratri 2025 - the auspicious festival celebrating Lord Shiva known as Mahashivratri! Mahashivratri, also known as the Great Night of Shiva, holds immense significance in Hindu culture. It falls on the 14th day of the dark fortnight of Phalguna month according to the Hindu lunar calendar. This year, Mahashivratri 2025 is anticipated to be a time of profound spiritual devotion and celebration.

Shivratri is celebrated on the 6th night of the dark Phalgun (Feb or March) every year. On the auspicious day, devotees observe fast and keep vigil all night. Mahashivratri marks the night when Lord Shiva performed the ′Tandava′. It is also believed that on this day Lord Shiva was married to Parvati Ma. On this day Shiva devotees observe fast and offer fruits, flowers and bel leaves on Shiva Linga. Shivratri is also spelled as Shivratri, Shivarathri and Sivaratri.Maha Shivratri is a popular Hindu festival. It is celebrated every year in reverence of the Lord Shiva. Maha Shivratri festival is also widely known as 'Shivratri'. It means the 'Great Night of Shiva'. This auspicious day is believed to be the day of convergence of divine powers of Lord Shiva and Goddess Shakti. It is believed that on this day the planetary position in universe evokes the spiritual energies very easily. Religious penances are carried out to gain boons through the practice of medication and yoga. People worships lord Shiva whole day and chants "Om Namah Shiva". Some devotees also perform Maha Mrityunjaya Mantra to seek divine blessings of Lord Shiva.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

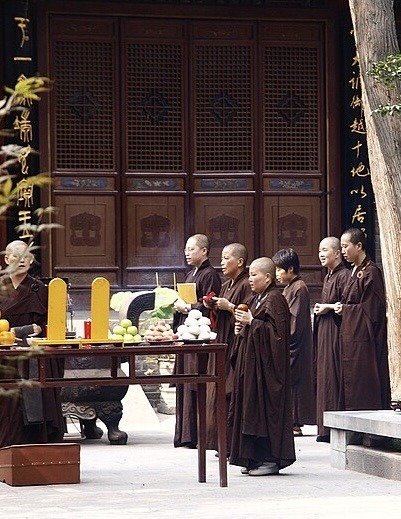

What are Nuns?

Nuns are a member of a religious community of women, especially a cloistered one, living under vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience.

They dedicate their lives to religious observance. Most nuns spend their time praying or meditating and doing service work in their communities.

Nuns in different religions 👇

Nuns in Christianity.

Nuns and sisters in Christianity belong to various religious institutes, each with its own charism. Both take vows, pray, do religious services/contemplations & live modestly. Nuns traditionally recite the full Divine Office in church throughout the day, while lay sisters perform maintenance or errands outside the cloister. Externs, who live outside the enclosure, may also assist with tasks.

Nuns in Buddhism.

Buddhist nuns, called bhikkhunis, mostly live under disciplined & mindfulness. They share important vows, offer teachings on Buddhist scriptures, conduct ceremonies, teach meditation, offer counseling, & receive alms. Bhikkhunis are expected to go against the materialistic values, focusing instead on spiritual aims outlined by the Buddha. They adhere to specific precepts guiding their behavior/lifestyle, which vary based on tradition & monastery.

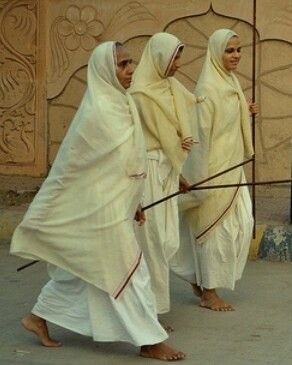

Nuns in Hinduism.

Hindu nuns, also called sanyasini, sadhavi or swamini, practice a monastic life of religious devotion by living simple lives of study, meditation & prayer. Some nuns seclude themselves in Hindu communities while others wander from place to place spreading the teachings of their faith, all their actions are directed as a service to Brahman. Hinduism teaches followers to respect these nuns for renouncing material things.

Nuns in Taoism.

Taoist nuns typically lived in temples known as guan, Celibacy was associated with early Taoist schools. They are solitary practitioners who take modesty & Clarity. In the Shangqing School, Taoist nuns are called nü daoshi or nüguan. their daily schedule included chanting scriptures, community work, and individual practices, including inner alchemical exercises.

Nuns in Shintoism.

Shinto nuns are called miko, or shrine maiden, they’re young nuns who work at shrines & heavily worship Shinto Kami (gods). Miko were once likely seen as shamans & priestesses but they are understood in modern Japanese culture to have an institutionalized role in daily life, trained to perform tasks, ranging from sacred cleansing to performing the sacred Kagura dance.

Nuns in Jainism.

Jain nuns are known as Aryika, or as Sadhvi. Aryikas (sadhvis) mostly meditate near Vrindavan, India. In Samavasarana of the Tirthankara, aryikas sit in the third hall. The Aryikas lead a simple life, with few possessions, and consider the world their family. They live in small groups and dedicate their days to meditation, study, carefulness & extreme compassion.

#religion#religions#nun#nuns#christianity#buddhism#hinduism#Taoism#Daoism#Shinto#shintoism#Jainism#bhikkhunis#bhikkhuni#sanyasini#sadhavi#swamini#nü daoshi#nüguan#miko#Aryika#desiblr#lotus-list

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

What does "Once a Jew, always a Jew" mean? Does that mean you cannot "stop" being Jewish? You have people proudly calling themselves ex-Christian, Ex-Hindu or ex-Muslim and oftentimes they don't want anything to do with religion and/or spirituality. Or Judaism nature as an ethnoreligion changes that?

Judaism is an ethnoreligion, so even if a Jew stops being religious and/or observant, they're still a Jew. Even if they convert to another religion, they're still Jewish. There is such a thing as heresy in Judaism (the parameters to being a heretic are very strict), but even heretics are merely exiled from their communities (or even the Afterlife), but they're still Jewish. If you're born a Jew, you're a Jew forever. If you convert to Judaism, you're a Jew forever. You can leave the greater Jewish community, but you can't just stop being Jewish.

154 notes

·

View notes