#Harlem in Depression

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Depression in Harlem, ca. 1934.

Photo: Aaron Siskind via the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

#vintage New York#1930s#Aaron Siskind#vintage Harlem#Harlem in Depression#hunger#Great Depression#unemployment councils

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Self-Portrait (Malvin Gray Johnson, 1934)

#self portrait#harlem renaissance#modernism#art#painting#1930s art#1930s aesthetic#great depression#american art#american artist#african american artist#black art#black artist

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cab Calloway and his band in a sleeper car, 1933

#Cab Calloway#musicians#photographs#jazz history#1930s#20th century#great depression#gelatin silver prints#american#north america#Harlem renaissance

256 notes

·

View notes

Text

also. interesting that the main argument for social darwinism and denying black people personhood was that black people couldn't produce art to the same quality and capacity as white artists. and now--a century later--that racism shows up instead as 1. stealing from/not crediting black artists and 2. denying and dismissing all forms of black art

#emyrs.txt#i love history so much genuinely. if only it weren't so fucking depressing.#also i'm over generalizing here. can't remember when the social darwinism arguments were happening i think it was the 1860s?#but i said a century later bc i was specifically thinking about the harlem renaissance/great migration.#bc that's really when black culture started to seep into the greater overall american culture.#due to radios. and also just due to the great migration.

1 note

·

View note

Text

summary: your estranged grandmother left you exactly one thing in her will: a sprawling luxury apartment in the heart of seoul — the kind of place that could singlehandedly cover your entire college tuition if you ever decided to sell it. now you had a penthouse all to yourself, a pink-tiled kitchen you weirdly adored, and a hopeless, slow-burning crush on the absurdly attractive neighbor who barely looked your way.

authors note: banner credits to the talented rockwsesx on pinterest, i loved this. this is very self indulgent and not your typical vamp!au. pls read the tags before starting this one. this is the prologue, just to set the vibe. this story is seen better in dark mode!

warnings and tags: soulmates concept • mentions of sex • dark themes such as depression, melancholy, killing • enhypen live together and are mentioned all the time • vampire!enhypen • vampire!sunghoon x collegestudent!reader • HEAVY ANGST • poor attempt at comedy • fluff if you squint • bad writing • sunghoon is 633-years-old and reader is 23 LMAO.

word count: 5.8k

previous chapters: series masterlist.

it had been theirs for so long. the whole floor. silent, still, untouched by anything that could interrupt the quiet sunghoon’d learned to rely on.

he’d forgotten what it felt like to have someone this close. and being the creature that he was, with the privileges he’d earned long before this city was ever built, sunghoon couldn’t help but be curious. tired, but curious — about the human life brought so suddenly, so carelessly, within reach.

about you.

sometimes he thought curiosity was the only thing left in him that hadn’t turned to stone. when you are six hundred and thirty-three years old, at some point, the news, the wars, the seasons — all of it stops meaning anything. life ends up being nothing but a blur.

some of his mates still lived like there was a tomorrow they didn’t know, like there were things left to feel surprised about.

but he had seen everything. the wars, the loves, the taste of absinthe in 1880s paris, watching jazz get born in a basement in harlem, affairs with queens, duels at dawn, crimes.

niki would joke that it was because he was the oldest — the supposedly strongest vampire among them and the most experienced. even though heeseung, jake and jay had lived longer human lives, it was sunghoon who carried the weight of stronger suits and deeper stories to tell.

he didn’t care for that, along with the many other things he didn’t care on his vampiric life, each of them filled their days differently.

jay still walked through the city like it belonged to him — expensive coats, sharp shoes, always returning just before dawn with the smell of cigarette smoke clinging to him, though he never smoked.

heeseung worked in a gallery in gangnam, all clean lines and polished marble floors, standing quietly among paintings that cost more than most people’s lives. he said it passed the time.

niki was always moving — fixing the things no one else cared to fix. the old elevators that still shuddered on their way up, the tangled network of wires behind the walls. sometimes he disappeared for days, slipping into parts of seoul sunghoon no longer bothered to map.

they had found ways to pass the time.

sunghoon, on the other hand, had stopped trying.

the seonghyeon building remained the same. the long hallways, the locked doors, the windows that watched over a city none of them had been born in.

and now there was you across the hall. a girl. young, human, carrying with her the soft, fragile scent of something that had not yet been broken by time.

your first encounter was an accident. your mail had been delivered to their door by mistake, and sunghoon was the one chosen to return it. why? because his brothers were rarely seen at home during the nights.

he rang the doorbell five times before you opened it, a towel wrapped loosely around your body, hair still wet and clinging to your skin. he felt a little bad. you were visibly uncomfortable with the unexpected visitor, shifting your weight, one hand gripping the towel tighter — but he was just doing a favor.

“oh you must be the neighbor next door”, you thanked him with shy eyes and pink cheeks. “i kept hearing noise during nights but never seen anyone at the corridors”.

“we’re noisy sometimes, i apologize”. sunghoon said and left, clearly unbothered by the way you eyed him and seemed interested in starting a conversation. he delivered your package and went back to the coven.

he didn’t pay much attention to the way you eyed him, the way your gaze lingered longer than it should have, tracing the sharp lines of his face with something close to disbelief.

he didn’t notice that, for you, it was the first time you had been struck silent by beauty. not admiration, not attraction — but something closer to awe.

you wanted to ask his name, ask what did he mean by saying “we”, but he left before you could ask that.

sunghoon was used to the curious eyes following him. he was a vampire, after all — people tended to have that reaction around them. they looked at them as something too ethereal for humanity, even though, over the years, some humans had begun to approach that same untouchable beauty.

the human world was getting bigger, louder, messier — while the covens quietly disappeared. aesthetic procedures had become more common, more seamless, blurring the line between natural beauty and something manufactured.

it made recognizing a vampire — one truly blessed with longevity — harder than it used to be.

their history was reduced to bullet points in textbooks and museum exhibits. he didn’t blame you for the curiosity, most humans lived entire lives without ever meeting one.

the politics, the power, the endless cycle of protecting what was theirs — it didn’t feel urgent for sunghoon anymore. it just felt old.

and you — you seemed like the kind of person who knew about their kind in the same way everyone did now.

you’d learned about vampires in school, probably. seen the documentaries, skimmed the news articles, maybe overheard a story once about someone who claimed to have met one.

but you didn’t really bother looking up, thinking you’d never meet one in real life.

that was exactly what sunghoon had in mind the second time he saw you — when you appeared at their door, shivering, apologizing, not realizing what you were walking into.

your dried hair was long, the color pretty enough to draw sunghoon’s attention. your voice was the same he remembered from two nights ago, shy and jovial.

sunoo jumped from the couch at the sound of your voice, nearly spilling his glass of hibiki — the rare whiskey he kept for nights when his favorite mexican telenovela reprise was on. his mouth turned into an “o” before his features contorted into a frown, the fact that they never had visitors making him scared.

sunghoon watched from where he always did, leaning just out of the light, letting the others fill the space first.

you explained — almost freezing in your apartment, standing there in your blue pajamas, shivering, no idea how to work the thermostat.

niki was the one who helped, eager, slipping on his sneakers before anyone could stop him. he seemed more than willing to visit your apartment, bright-eyed at the sight of your silky hair, your warm skin, the way you smiled in gratitude.

he left their sight and heeseung tsked at him, knowing he was in for a ride if he decided to get involved with their neighbor, of all people. niki was young and naive, just turned into a vampire 65 years ago, but none of them could pinpoint exactly what was wrong with that, not really.

they all had their phases, after all.

jake had a partner now — a human girl he swore was his soulmate, like that made it any less predictable.

heeseung used to have one, too, years ago, but now he mostly kept to himself, reading philosophy books and drinking overpriced wine like he wasn’t still haunted by it.

sunoo was practically celibate at this point — voluntarily, or so he claimed, though they all suspected it was just laziness.

jungwon had chosen power over companionship. he had made peace with the sharp, necessary parts of what they were. he didn’t look for softness, didn’t ask for it. he carried the weight of all of them — their violence, their survival — like it was just another tailored coat he’d thrown over his shoulders before stepping out for the night.

and then there was jay.

jay burned through life like he thought he could outpace the centuries by moving fast enough, killing often enough, fucking hard enough. he liked the blood. liked the ritual of it, the power, the intimacy. that was why jungwon kept him close — a weapon that knew how to wield itself, but only just.

sunghoon was the opposite of it, wanting to keep it calm after years of forcing his strength on mankind. he liked things peaceful, that was his trait for being the most experienced and unbothered.

sunghoon was still thinking about that — about their lives, their loves, and how it always went with their kind — when niki’s voice cut through the apartment, bright and human in a way none of them really were anymore.

he came back from your apartment, shrugging off his shoes and grinning like he’d just come back from a field trip.

he dropped onto the couch next to sunoo, who was still nursing his glass of hibiki, eyes fixed on the muted telenovela playing across the screen.

for a second, niki just sat there, catching his breath, hands drumming against his knees like he wasn’t sure what to do with all his leftover energy.

then, finally:

“her kitchen tiles are all pink,” he said, like it was the most fascinating thing in the world.

sunghoon didn’t look up, not really interested in the younger one’s shenanigans.

niki kept talking — about your apartment, your kitchen tiles, your laugh — until sunoo finally complained that he wanted to watch his novela in peace.

the youngest rolled his eyes, muttered something under his breath, and left the room, already talking about some party he needed to get ready for.

sunghoon stayed where he was, silent, still, as the bright sounds of the television filled the space, too loud for how late it was — but no one told sunoo to turn it down.

your shivering figure kept replaying on his head, curious of how a young soul like you could end up in a place like seonghyeon.

——

being the owner of a luxury apartment complex had its perks. one of them was that the rules didn’t apply to them. no noise complaints, no curfews, no awkward meetings with building management about renovations or guest policies.

they just did what they wanted.

sunghoon supposed that was part of why they’d stayed in seonghyeon so long — not just the history, not just the privacy, but the simple fact that here, no one told them what they could or couldn’t be. they owned it. the whole floor. the garden. the elevators. the library. the sauna.

it meant sunghoon could spend hours tending to the greenhouse on the rooftop without anyone asking questions — without anyone asking why a creature who didn’t need air or light or warmth would care about something as fragile as plants. but he did. he always had.

the garden had been his for decades now, shaped slowly by his hands and his moods, a place that had nothing to do with survival and everything to do with the quiet practice of control. rows of white camellias stood in perfect symmetry along the inner walls, their waxy petals always immaculate, while midnight violets sprawled low in the corners where the light softened in the late afternoon. a line of blood-red amaryllis stretched defiantly across the back wall, always blooming too early, too violently, as if they’d learned impatience from him. climbing wisteria looped lazily over the old wrought-iron trellises, hanging in pale lavender sheets that dripped scent and memory.

watering them wasn’t about necessity. it was about the fact that they could still die if he wasn’t careful. about knowing there was still something in this place — in this life — that required attention, precision, presence. he liked that. maybe more than he should have.

and maybe that was why, on your second week in the apartment, he noticed you standing there in the garden, just beyond the misting system he had just adjusted, your figure soft and unexpected against the geometric order of the plants. he hadn’t heard you come in. one minute, he was watching the fine spray bead on the thick green leaves of the orchids, admiring the slow accumulation of moisture, and the next — you were there. you stood in that tentative way humans always did when they weren’t sure if they were trespassing, your gaze moving from the camellias to the violets to the amaryllis like you didn’t quite know where to settle.

the doors to the rooftop were usually supposed to be locked, but being the owner of the building made sunghoon never lock anything. he hadn’t thought anyone would find their way in — no one had for years — but here you were, standing in the one space he’d kept mostly to himself, looking around like you didn’t quite know if you were allowed to stay, but too curious to leave.

you wore a grey puff jacket, zipped up carelessly like you’d just come in from outside — and you probably had — with a pair of clear-washed jeans that shaped your body in the kind of effortless way sunghoon knew wasn’t really effortless, but still looked like it was. your hair was tied back, loose strands falling against your cheek, and your phone was in your hand, its pink case bright and stupidly soft-looking, practically begging for attention even as your eyes stayed elsewhere, lost somewhere in the rows of flowers you didn’t yet understand.

you noticed sunghoons presence seconds after you almost tripped over a ceramic vase tucked near the base of the trellis, your body pausing mid-step, that quick human flicker of embarrassment crossing your face before you steadied yourself. sunghoon didn’t move. he waited, curious in that quiet, distant way he always was, just to see if you would stay when you saw him or if you’d do what most did — apologize quickly and rush off, pretending you hadn’t intruded.

sunghoon didn’t mean this in a bad way, but you didn’t look like you belonged in seonghyeon, not in the way the others did. the residents here wore discreet wealth and predictable detachment. he wondered, absently, how you’d ended up in a luxury complex like this, being so young and, from the look of it, so alone. you didn’t wear your money, if you had any. your clothes were simple, practical, none of the curated casual that most of the residents draped themselves in.

they knew the old owner of your apartment, of course. everyone did. a grey-haired woman with a sharp tongue and a perpetual scowl who’d refused to rent the place out, even when she could’ve made a small fortune doing so. stubborn as hell, but private, always private.

sunghoon hadn’t seen her in years, not since the last time she’d walked through the hallway, muttering about the elevators being too slow. she must’ve sold it to a distant relative, or maybe she’d passed, and her family sold it off to make their clean exit. he didn’t know, hadn’t asked.

either way, now you were here. standing there, looking nothing like the old woman he knew was the previous owner, staring right back at the man dressed in all black and with dirt in his hands.

the awe in your face made sunghoon suppress what might’ve been an annoyed frown, barely, keeping his expression as blank as it always was, waiting — with the same tired patience he carried everywhere — for your voice to make its debut in the quiet space he hadn’t intended to share.

“are those… hydrangeas?”

your voice broke the silence, flat but curious, as you stared at the pale clusters blooming stubbornly near the base of the trellis, their soft petals full and heavy in a season where nothing should be.

you frowned, shifting your weight like the flower itself was personally offending you.

“what the hell are they doing alive right now?” you muttered, then glanced at him, squinting. “pretty sure these things are supposed to give up by, like… october.” you paused, then, after a second, added, quieter, “wish i had that kind of energy.”

sunghoon’s eyes drifted to the small crease at the edge of your jacket sleeve, the way your fingers kept fidgeting against the fabric, tightening and releasing like you couldn’t quite decide whether to stay or go. your voice, too, had that persistent edge — soft but insistent, pushing through the silence he offered like you refused to be ignored, even though most people would’ve walked away by now.

he could’ve told you the hydrangeas weren’t real — not in the way you meant — but he didn’t.

he just stood there, perfectly still, expression unreadable, like he hadn’t even heard you at all.

“you know, the pink ones don’t even look real,” you said, crossing your arms, staring at the hydrangeas like they’d personally wronged you. “like someone’s out here spray-painting flowers at midnight for instagram.”

you kept talking, which was… annoying, probably. but also maybe kind of charming, depending on the angle. “do you, like… spray-paint them?” you asked, glancing at him. “because honestly, that would be some next-level dedication to aesthetic.”

still nothing.

sunghoon crouched down beside the nearest planter, adjusting the soil with careful, practiced hands — like you weren’t even there. like you were part of the wind or the background noise. he could see you clear your throat, trying again.

“so… are you a florist or just a very intense hobbyist?”

again, silence. you were now officially having a one-woman conversation in a secret garden with the hot neighbor who either hated you or literally couldn’t hear you.

you hadn’t even decided what your next brilliant line was going to be when his voice finally cut through the stillness, low and even, almost like it wasn’t meant for you at all but just the space between you.

“you’re the new neighbor.”

simple. detached. obviously not what you were expecting.

“you remember me,” you said, grinning a little too wide, like an idiot, but whatever — small victories.

he didn’t say anything to that, didn’t confirm or deny it, just stood there like he always did, still as the damn hydrangeas.

“i’m sorry — i don’t want to sound ridiculous,” you said quickly, even though, at this point, you already absolutely did. “it’s just… i saw movement around here these days and kind of wondered what this place was. i mean— this building’s so big, i get lost sometimes…” you trailed off, gesturing vaguely at the flowers, like they might somehow back you up.

sunghoon didn’t say anything.

just kept standing there, quiet and still, watching you with that same unreadable expression that somehow made the whole thing feel even more absurd.

sunghoon was quietly enjoying your suffering, your ridiculousness — the way you stood there, talking about plants you didn’t even know the name of, trying so hard to say something that would make you sound interesting, or smart, or at least not completely unhinged.

hell, he might even start to feel bad for you at some point.

but right now, all he felt was… entertained.

and that, in itself, was surprising, considering the fact he always won the nonchalant competition among his brothers.

sunghoon watched you for another long, weighted second, letting the awkwardness sit there just a little longer — not because he wanted to make you uncomfortable, but because he didn’t feel any particular need to make you comfortable either. you’d come into his space, after all.

“you’re not from here,” he said, not a question, just an observation, as flat and certain as everything else he said.

if you’d been expecting something softer — comfort, maybe, or even mild curiosity — that wasn’t what you got. your expression shifted, barely perceptible, a micro-flicker he wouldn’t have caught if he weren’t so instinctively attuned to such things. disappointment, perhaps, but he didn’t bother parsing it further.

especially because you kept talking — as you always seemed to do.

“no… i’m not,” you said, shifting your weight, your fingers tightening reflexively around your phone, the pink case creaking softly under the strain. “it was… my grandmother’s place. she passed it down to me. not really her place, i guess, because she didn’t even live here, but… she was the owner. or something like that.” you let out a small breath, frowning at your own explanation. “i don’t really know. we weren’t… on talking terms. like… ever.

and then, as if suddenly realizing how that sounded, you rushed to clarify, gesturing vaguely in his direction — even though it made zero sense to be over-explaining your family drama to a stranger, here, now, at this hour.

“not that she was a bad person!” you blurted out, your hands lifting automatically like they could somehow catch the words before they fell. “we just didn’t have much contact. she… kind of didn’t like my father. and then made my mom divorce him and…”

you trailed off, finally hearing yourself, finally realizing how absurd it was to be standing here, next to a man you didn’t even know, unloading all this like he’d asked.

“i just moved in. i’m starting college this semester.” and then, because you couldn’t help yourself, because silence around him felt too heavy, too final, you added with a small, awkward laugh, “so… yeah. this place is huge. i get lost. a lot.”

sunghoon didn’t smile, but there was something almost like recognition in his eyes, some small flicker of understanding that passed before he looked away again, toward the hydrangeas, as if they were suddenly more interesting than your confession.

“it’s a big building,” he said simply, like that explained everything, like that was all the conversation you’d need — like you hadn’t just overshared half of your family trauma in a single breathless sentence.

you wanted to hide your face in the fucking dirt right then and there, to disappear between the neatly arranged hydrangeas and never be seen again, because congratulations — you’d just made a complete fool of yourself in front of the cute neighbor.

“yes, it’s big,” you blurted out, immediately wanting to die all over again, because what the fuck kind of recovery was that.

but sunghoon just stood there, silent as ever, his eyes flicking briefly to the hydrangeas, then back to you.

he wasn’t particularly interested, not really. not in your family — he’d gotten what he was curious about; you were Miss Han’s granddaughter and that was… fine, that was enough. not in your college status, not in your awkward over-explanations or your objectively terrible flirting attempts.

he just found you… weird. and, honestly, kind of a perfect match for naïve little niki, but he wasn’t about to get deeper on that.

but still, as he watched you standing there, fumbling through your stupid, nervous words about plants and getting lost and college, sunghoon felt it — that sudden, unfamiliar pull right in the center of his chest. not curiosity, not concern, but something quieter, something older, maybe even something he’d almost forgotten how to recognize.

the urge to not leave you alone with your own awkwardness, sunghoon felt the pull right as his eyes came in contact with your neck.

the ridiculousness of it — of you, of his weird and sudden fixation on that part of your skin — should have made it easy to let the conversation die, to turn away, to retreat back into the silence he’d always preferred.

but instead of leaving, he exhaled softly — almost imperceptibly — and shrugged out of his outer coat in one smooth, practiced motion, folding it over the back of the wrought-iron chair beside him like he wasn’t even thinking about it. then, without a word, he crouched down beside the neat row of haworthia at his feet — their dark green, ridged leaves fanning out in perfect, geometric spirals, small and sharp and quietly alive — and started tending to them, his long fingers moving methodically through the soil, checking the roots, adjusting the placement of a few stones that had shifted.

it was just past eight in the evening, the kind of quiet, transitional hour where the last traces of the day’s heat had already bled out of the air and the garden slipped into something softer, colder, more his.

sunghoon ignored your boots, even though they were tracking faint streaks of dirt across the polished stone floor, ruining the clean lines he’d so carefully maintained.

he ignored the fact that you were still standing there, hesitating like you weren’t sure whether you were meant to stay or leave.

he ignored the way he could distinctly hear your pulse from across the winter garden, could track the subtle rise and fall of your chest, and almost taste the scent of your plasma in the cold air.

why was it so distracting?

you shifted slightly, as if sensing his hyperfixation on your breathing, your boot scraping softly against the stone, the sound sharp in the otherwise muted space.

“do you… live here?” you asked, your voice careful, like you weren’t sure if it was a stupid question or not, but you had to say something, anything, to puncture the silence.

he didn’t look up right away, his focus still on the plants at his feet, his fingers moving absently through the soil as if your presence hadn’t already disturbed everything.

“yeah.”

simple. flat. like the answer wasn’t even worth more than that.

you nodded, swallowing a breath, your grip on your phone tightening again.

“alone?” you asked, like an idiot, like there was anything cool about standing in a winter garden awkwardly interviewing your neighbor. “i just… moved in,” you tried again, your voice a little too high, a little too eager to fill the space he left open. “across the hall.”

he knew that, obviously.

but he didn’t say it.

just made this quiet, non-committal sound — something between acknowledgment and indifference — before brushing a bit of soil off his palm and shifting the smallest succulent in the arrangement by half an inch, like that was somehow more important than responding to you.

you were just standing there, shifting your weight, fidgeting with your stupid pink phone case, breathing too fast, smelling like soap and cold air and something he couldn’t quite name but could almost taste in the back of his throat.

god, he could literally taste you. why was that?

that quiet, metallic sweetness of human blood — not sharp, not urgent, but there, unmistakable, teasing the edge of his senses in a way he hadn’t let it in years.

and it wasn’t just that.

it was the way you smelled different.

not perfume, not anything artificial. just warm skin, faint nerves, the clean press of cotton from your jacket, and underneath all of it, that subtle, unavoidable pulse — your body doing what human bodies always did, announcing itself in ways it didn’t even know how to hide.

it was distracting.

unnecessary.

sunghoon couldn’t remember the last time his body reacted like this to anyone, let alone someone so… ordinary.

you weren’t doing anything special — just standing there, awkward, fidgeting, your breath fogging faintly in the cold air.

and yet, something in him was already responding, already tuning itself to the rhythm of your pulse, already marking the way your warmth cut through the sharp edge of the winter air like you belonged here, like you’d always been part of this place.

he didn’t like that.

he didn’t like that his focus was slipping — that this old, instinctive part of him, the part that was supposed to be dormant, was sharpening, waking up, paying attention.

he hadn’t let it in for years.

he hadn’t needed to.

he could hear every beat, every shift in your breath, every flicker of hesitation as you started moving, walking slowly, carelessly, past the rows of carefully arranged plants, getting closer to him like you thought maybe he wouldn’t notice.

you stopped just beside him, close enough that he could feel the faint change in temperature, the heat radiating from your body cutting through the cold air that clung to the winter garden.

you tilted your head, curious, peering down at what he was doing, your hands tucked awkwardly into the sleeves of your jacket.

“are you deaf?”

your voice broke the quiet again, small and casual, like this was just another normal interaction, like you hadn’t just crossed some invisible boundary neither of you knew how to name.

sunghoon didn’t answer right away, finding your question hilarious.

he didn’t move, didn’t even look up, didn’t give you anything to read.

but inside —

his hands had gone still, fingers curling slightly into the cold edge of the pot he’d been tending, anchoring himself in the familiar texture of the soil because the simple fact of your proximity — the smell of your skin, the sound of your breathing — was enough to send a low, sharp pulse through his body that he hadn’t felt in decades.

sunghoon adjusted the last pot in the arrangement, brushing a trace of soil from his fingers with a practiced efficiency, then finally straightened up to his full height, his eyes flicking to you — not with interest, not even with annoyance, but with that same quiet, unreadable detachment he wore like armor.

“you shouldn’t be in here.”

his voice was calm, even — not accusatory, just factual, like you’d accidentally wandered into an employees-only section at a museum.

then, without waiting for your response, he stepped past you, moving down the narrow path between the plants with the kind of smooth, controlled grace that only made you feel even more awkward for still standing there.

you hesitated for half a second, then — stupidly, impulsively — followed.

he didn’t acknowledge it, didn’t turn, just kept moving, stopping at the old stone basin tucked into the corner, turning on the cold water with a smooth twist of the brass tap and rinsing the soil from his fingers like this was just another routine moment, like you weren’t trailing quietly behind him.

“why shouldn’t i?” you asked finally, your voice lighter than you felt, more curious than confrontational. you glanced around, gesturing vaguely at the space. “isn’t this a… common area of the building?”

he dried his hands on the edge of his coat, not looking at you, not offering anything more than a simple, quiet:

“not really.”

“what do you mean?” you asked, frowning slightly, still trailing after him as he dried his hands. “are you… the owner or something? i thought this was a common area, and, as a resident, shouldn’t this be ok?”

sunghoon didn’t pause, didn’t even look at you when he answered, just kept walking toward the exit, his voice calm and detached, like he was reading from some impersonal list of facts.

“i’m the owner.”

then, after a beat, almost as an afterthought, he added:

“the seven of us live in the penthouse. this is our building. we have our rules.” another pause as he pushed open the door, the cold air slipping through. “one of them is to not circle around after nine p.m. without previous notice.” and then, with the same offhand finality, like it didn’t even matter: “and yes. this area is privately mine. i bought it. it’s my part of the deal.”

your breath caught for half a second — not because of what he said exactly, but how casually he said it, like it wasn’t the most intimidating thing in the world.

you blinked, following him out the door like some stubborn ghost of your own embarrassment, still trying to catch up with everything he’d just revealed.

“oh,” you said, brilliantly. then, after a beat: “oh my god, i didn’t know… i thought you were just— i don’t know— some guy who lived with his roommates or something. i mean— there is seven of you?”

sunghoon finally glanced at you then, and for the first time, really looked.

his gaze wasn’t unkind — sharp, yes, unreadable, yes, but something in it softened just slightly at your flustered panic. the corner of his mouth twitched, not quite a smile, but close enough to pass for one if you weren’t being too picky.

“we are strangers, so it’s not a surprise you don’t know,” he said simply, like that settled it. “what happened to your grandma?” he asked right after, almost flatly, but the question hung heavier than he meant it to. that was the only curiosity left in him.

you shifted, hesitating.

“she died,” you said, voice quieter now, not sure about his sudden interest about your family after ignoring you for the last ten minutes. still, stupidly, you answered. “a few months ago. no one told me until after the funeral. i think… i think she left the apartment to me just to spite my mom. she never mentioned seven guys living in this area, she actually rarely was here or so i thought...”

you tried to laugh, but it came out too small, too hollow to be anything but a ghost of amusement.

sunghoon didn’t press further. he just nodded, slow and deliberate.

he didn’t stop walking. didn’t turn. just kept moving toward the last exit with that same smooth, unbothered rhythm, like you hadn’t just trespassed on his private space and asked him a string of questions he had no intention of answering properly.

and maybe it was that — the sheer fact that he was just going to leave, that he hadn’t even given you the basic politeness of his name — that made you blurt the next thing without thinking, desperate to catch at least one thread before it all slipped through your fingers completely.

“what’s your name?” you called after him, your voice softer now, but still stretched tight with nerves — like the words had to fight their way out of your chest. and then, as if some part of you panicked at the silence he left in his wake, you added the kind of thing people say when they’re trying too hard to seem casual, even though it only made you feel more ridiculous the second it left your mouth:

“i’m sorry. i don’t really know anyone in seoul yet. i thought maybe… i could make friends here.”

you winced internally as soon as it was out there, like hearing it aloud confirmed how pitiful it sounded. but it was also the truth — raw and a little embarrassing, hanging between the two of you like a thin thread waiting to snap.

sunghoon paused at the door, his hand still resting lightly against the iron handle, fingers curled like he was weighing whether to just keep going, to let you stand there with your awkward apology and your too-late question hanging uselessly in the cold air.

but then, without any particular urgency, he turned.

for the first time, really turned — not that distant, impersonal glance he’d given you earlier, but a full, deliberate look, his dark eyes cutting through the space between you like he was finally seeing you, not just another tenant or a passing distraction, but something else entirely.

and then —

he smiled.

small, barely there, more reflex than intention, like his body had decided to acknowledge you even if his mind hadn’t fully signed off on it yet.

“sunghoon,” he said simply, his voice quieter now, stripped of the earlier indifference, just… plain.

and for a second — just one — his eyes stayed on yours, steady, almost curious, like he was letting you take the name, hold it, decide what to do with it.

then, just as easily, he turned back, pushed the door open, and stepped out into the hall without another word, the sound of his boots fading smooth and even against the marble floor until it was like he’d never been there at all.

author's note: this wasn’t proofread yet, so i’m sorry if the mood is a little weird. i still don’t know where this is going, but already started the first chapter. if you read this, pls tell me what you think of it. i'm sorry if this is trash, just give it a shot pls. nonchalant sunghoon until he is obsessed with reader hehe. send me a request • my masterpost

#★ zrcdd works !#🏛️ the seonghyeon jaega fic ✩#enhypen#enhypen fluff#enhypen smut#enhypen lore#enhypen x reader#enhypen fanfic#enhypen fanfiction#enhypen fanart#enhypen fantasy au#enhypen fandom#enhypen vampire au#enhypen vampire#vampire!au#supernatural#park sunghoon x reader#park sunghoon smut#sunghoon fluff#sunghoon x reader#sunghoon imagines#sunghoon#sunghoon vampire#vampire#vampire!sunghoon

320 notes

·

View notes

Text

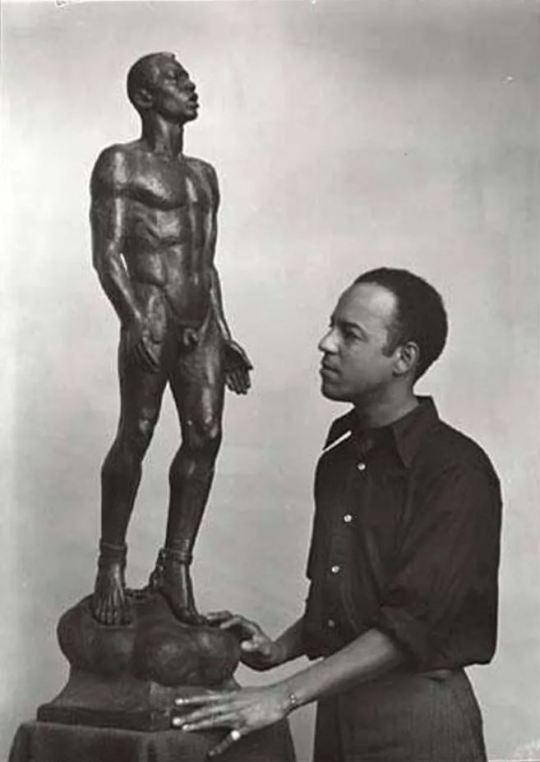

Richmond "Jimmie" Barthe (1909-1989) was an African-American sculptor and a key figure in the Harlem Renaissance in the 1930s. That he was also a gay man who expressed his orientation in his work is most likely why he fell into obscurity by the 1940s.

Much of his art depicted African-American men in sensual poses, often nude. Today, his work seems not that confrontational, but in a basically racist, sexually nervous America of the middle of the last century, it is remarkable that his work received the acclaim that it did.

Barthe was born to Creole parents in Bay St. Louis, Miss., and his art brought him out of poverty. A beautiful, bright boy, he was already winning awards for his drawings by the age of 12. Inspired by the neoclassical art he saw in the homes of the wealthy folks he worked for as a houseboy in New Orleans, he developed a lifelong interest in Greek and Roman mythology.

Funded by his local church, he attended school at the Art Institute of Chicago and began to have adult affairs with men who sometimes became patrons. He also had a brief affair with author and actor Richard Bruce Nugent, who was a cast member in Dubose Heyward's play Porgy.

In 1930 he relocated to New York and attended A'Leila Walker's "Dark Tower" gatherings, known as a venue where black and white men and women, often gay, mingled. The photographer and writer Carl Van Vechten was deeply involved with the black community of New York in the '30s and was an ardent supporter of Barthe's work. His reputation grew and his work was included in a 1935 exhibit of African-American art at the Museum of Modern Art.

He had success and fame. He even had a female patron who set up a trust for him that gave him the freedom to work without financial worries. But he was still an outsider in many ways. He was not a part of the white art world, and his uncompromising homosexuality kept him distanced somewhat from other artists of the Harlem Renaissance. His love life was a series of short affairs that never developed further.

Constantly searching for community, he moved to Jamaica only to find himself even more estranged from others. He fell into deep depression and mental illness. Commissions came sporadically, and he met them with varied results, teetering on the edge financially and emotionally.

In 1975 he moved to Pasadena, Calif., and a year later curators at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art included his work in "Two Centuries of Black American Art." The attention to his work, the growing respect of a younger audience to artists of the Harlem Renaissance, and the support of his friends brought Barthe stability once again. He lived out his later years as a treasured part of the art community, dying in Pasadena March 6, 1989.

(The Advocate)

333 notes

·

View notes

Text

Midnight Pals: D&D

Elon Musk: mama mia Musk: life, itsa seems so empty Musk: [touching a framed portrait of Stephen King] since my-a best frienda moved away

Musk: i'm-a so depressed Musk: grok, what shoulda i do Grok: [slur] Musk: mama mia, you are righta,grok! Musk: i SHOULD buy Hasbro to secure the rights to dungeons anna dragons!

Stephen King: submitted for the approval of the- Elon Musk [rising out of bushes] eyyyy Stephano king King: elon? are we still doing this?! King: i'm gone from twitter now! King: i'm finally… King: clean

Musk: maybe you heard i tweeted ima gonna buy hasbro Barker: christ why would we hear that Musk: eyyy i tweeta it, itsa news! MusK: datsa how da lasangna is made, paisano!

August Derleth: okay welcome to another call of Cthulhu game Derleth: what are your characters this time? Victor LaValle: i'm sweet sweetbreads, the harlem hustler Brian Keene: i'm dr. batcountry, the gonzo journalist Nick Mamatas: i'm groovio daddy, the freaky deaky beatnik Elon Musk: ima da paladin!

Derleth: excuse me? i don't think you're part of this group Musk: eyyy i buy Hasbro, so now ima member of EVERY D&D group! Derleth: this isn't D&D! it's call of Cthulhu! Derleth: its owned by chaosium! Musk: Musk: not for longa!

Musk: i owna all ropleplaying games now, as a concept Musk: data mean, you hafta let me play! Derleth: ok ok fine Derleth: what's your character? Musk: ima da elfin paladin Derleth: this isn't that kind of game! Musk: mama mia you betta MAKE It datta kind of game or i breaka you face, pedodungeonmaster!

Derleth: guys, look i think we're gonna have to make some changes in the game to accommodate elon Derleth: i know this is unpopular but if we don't he's going to be crying all night Derleth: he is very rich, after all Keene: oh yeah very rich LaValle: very rich Mamatas: the richest Mamatas: like literally, i read he was

Derleth: ok so Cthulhu appears, role for sanity check Elon Musk: da elf paladin, he stabba da Cthulhu with a sword! Derleth: you can't do that!! Derleth: you need at least a boat to stab Cthulhu! Brian Lumley: no wait i like the cut of this elon's gib Musk: oooo disruptiano!

Musk: i stabba da Cthulhu Derleth: ok roll to see if you can kill an elder god by stabbing Musk: eyyy i don't need to roll no dice Musk: i buya da game, so i maka da rules Musk: it works, i win, Cthulhu i killa him Musk: also my character name? issa X.

#midnight pals#the midnight society#midnight society#stephen king#clive barker#elon musk#august derleth#brian lumley#victor lavalle#brian keene#nick mamatas

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

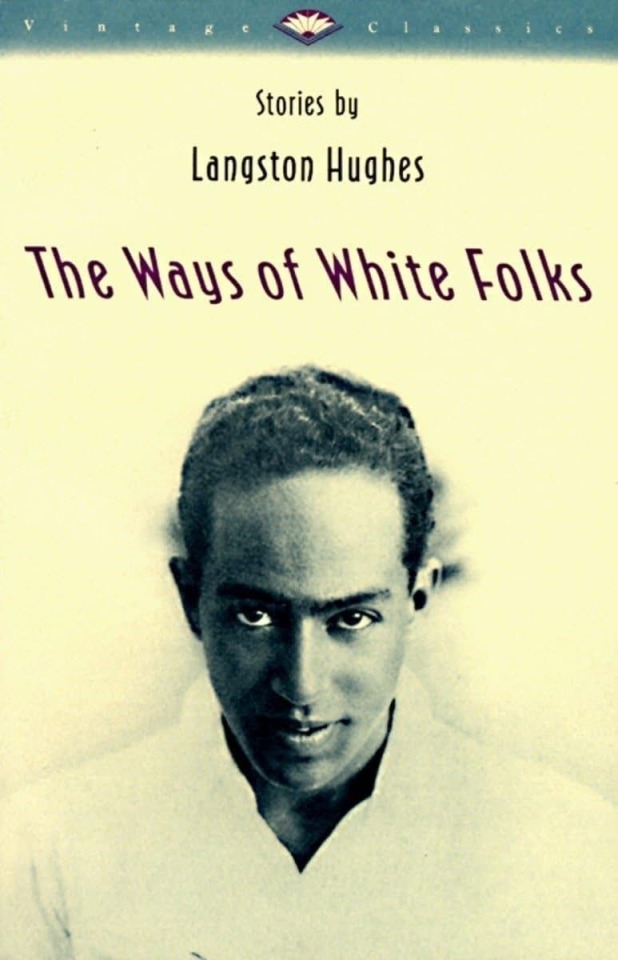

"The Ways of White Folks" is a collection of short stories by Langston Hughes, published in 1934. The book explores the complex relationships between black and white people in America during the 1930s.

🟠Key Themes

Racial Tensions:

Hughes examines the tensions and contradictions between black and white people, highlighting the ways in which racism and prejudice are embedded in American society.

White Supremacy:

The stories critique the ways in which white people maintain their power and privilege, often through subtle and insidious means.

Black Identity:

Hughes explores the complexities of black identity, including the ways in which black people navigate and resist white-dominated society.

Social Commentary:

The book offers commentary on issues like lynching, segregation, and economic inequality.

🟠Notable Stories

"The Blues I'm Playing":

A story about a black musician who becomes embroiled in a complicated relationship with a wealthy white patron.

"Father and Son":

A tale of a black man who is forced to confront his own identity and sense of self-worth in the face of white racism.

"A Good Job Gone":

A story about a black man who loses his job due to the machinations of a white coworker.

🟠Style and Significance

Hughes' Writing Style:

The stories are written in Hughes' characteristic lyrical and expressive style, which blends elements of jazz, blues, and poetry.

Social Realism:

The book is an example of social realism, a literary movement that focuses on depicting the harsh realities of everyday life.

Influence and Legacy:

"The Ways of White Folks" is considered a significant work in the Harlem Renaissance, a cultural and literary movement that celebrated African American art and identity.

🟠Context and Author

Langston Hughes:

A prominent poet, novelist, and playwright, Hughes was a key figure in the Harlem Renaissance.

Historical Context:

The book was written during the Great Depression, a time of significant social and economic change in America.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the twilight of the Roaring Twenties, a curious and dazzling phenomenon lit up the speakeasies, cabarets, and nightclubs of America’s urban underworld: the Pansy Craze. For a brief, glorious moment—between the end of Prohibition and the rise of the Hays Code’s censorship clampdown—the queers took center stage. Literally.

The Pansy Craze was a cultural moment in the late 1920s and early 1930s when openly gay performers—referred to as "pansies" in the slang of the time—became unexpected stars of nightlife entertainment, particularly in New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. The term “pansy” was both pejorative and empowering, depending on who was saying it and how. But these performers, many of whom were effeminate men or gender nonconforming in some way, were magnetic. They turned queerness into an act, a rebellion, a razzle-dazzle spectacle. And the crowds couldn’t get enough.

Imagine it: A smoky basement club, gin flowing under the counter, and the crowd pressed in tight as a slender, sharply-dressed man in a satin tuxedo and rouge sings torch songs with a wink and a knowing smirk. He might banter with the audience in a nasal drawl, lacing his monologue with double entendres, swishing and swooning with deliberate flair. And the audience? They weren’t gay—at least not openly. They were a mix of flappers, bohemians, slumming socialites, and businessmen looking for a thrill. Watching the "pansy" perform was like watching a forbidden fruit dance—titillating, transgressive, and in fashion.

This era birthed legends like Gene Malin, one of the first openly gay performers in American entertainment, who headlined clubs in drag and out, dazzling the crowd with biting wit and bold sexuality. Malin wasn’t hiding behind coded language—he strutted through the front door in full bloom, proud and polished. In a world where homosexuality was criminalized, his very presence was revolutionary.

Another notable figure was Karyle Norman, known as “The Creole Fashion Plate,” whose sultry voice and extravagant gowns earned him acclaim on the vaudeville circuit. Then there was Bruz Fletcher, a satirical cabaret performer whose songs were as biting as they were beautiful, often lampooning the hypocrisy of polite society with a wink to the crowd that got it.

The Pansy Craze wasn’t just limited to men. Drag kings and gender-bending women took the stage as well, especially in Harlem, where queer nightlife thrived in clubs like the Clam House, frequented by luminaries like Bessie Smith and Gladys Bentley—a tuxedo-wearing, piano-playing lesbian who brought down the house with her booming voice and bawdy lyrics.

It was a moment when queerness was briefly commodified and celebrated—not entirely accepted, but undeniably in vogue. There was a kind of unspoken contract: the straight audience got to peek behind the curtain of the so-called “degenerate,” and the queer performers got visibility, applause, and—if they were lucky—a paycheck. Of course, it didn’t last. The Great Depression brought with it a shift toward conservatism, and the Pansy Craze was soon snuffed out by stricter policing, moral outrage, and eventually Hollywood's infamous Production Code, which scrubbed gay characters (and actors) from the silver screen and shoved them back into the closet.

But the legacy lingered.

For those of us who remember the coded winks of Paul Lynde, the flamboyant brilliance of Liberace, or even the sly subversion of Charles Nelson Reilly on daytime television, there’s a direct line back to those smoky clubs of the 1930s. The Pansy Craze laid the groundwork for future generations of queer performers. It showed that our presence could be magnetic. That queerness could sell out a nightclub. That we had style, wit, and something to say—long before Stonewall, long before RuPaul.

It’s easy to forget that queerness was never truly hidden; it just shimmered in plain sight, dressed in sequins, singing torch songs under the klieg lights of a cabaret stage. And for a glorious moment, the world applauded.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

LOUISE JENKINS MERIWETHER

(May 8, 1923 – October 10, 2023)

Louise Jenkins Meriwether, a novelist, essayist, journalist, and social activist, was the only daughter of Marion Lloyd Jenkins and his wife, Julia. Meriwether was born May 8, 1923, in Haverstraw, New York, to parents from South Carolina.

After the 1929 stock market crash, Louise’s family migrated from Haverstraw to New York City. They moved to Brooklyn first and later to Harlem. The third of five children, Louise grew up during the Great Depression, a time that would deeply affect her young life and ultimately influence her as a writer.

Louise Jenkins attended Public School 81 in Harlem and graduated from Central Commercial High School in downtown Manhattan. In the 1950s, she received a B.A. in English from New York University before meeting and marrying Angelo Meriwether, a Los Angeles teacher. Although this marriage and later marriage to Earle Howe ended in divorce, Louise continued to use the Meriwether name. In 1965, Louise earned an M.A. in journalism from the University of California at Los Angeles. Her first book, Daddy Was a Number Runner, a fictional account of the economic devastation of Harlem in the Great Depression, appeared in 1970 as the first novel to emerge from the Watts Writers’ Workshop.

The circumstances surrounding this photo are largely unnatributed to larger context but some citation indicates that Jenkins-Merriwether was being questioned by police at a protest.

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bootblacks in Harlem, ca. 1937-40.

Photo: Aaron Siskind via the Jewish Museum

#vintage New York#1930s#Aaron Siskind#vintage Harlem#bootblacks#Great Depression#street photography#b&w photography

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Louise Jenkins Meriwether, a novelist, essayist, journalist and social activist, was the only daughter of Marion Lloyd Jenkins and his wife, Julia. Meriwether was born May 8, 1923 in Haverstraw, New York to parents who were from South Carolina where her father worked as a painter and a bricklayer and her mother worked as a domestic.

After the stock market crash of October 24, 1929, Louise’s family migrated from Haverstraw to New York City. They moved to Brooklyn first, and later to Harlem. The third of five children, Louise grew up in the decade of the Great Depression, a time that would deeply affect her young life and ultimately influence her as a writer.

Despite her family’s financial plight, Louise Jenkins attended Public School 81 in Harlem and graduated from Central Commercial High School in downtown Manhattan. In the 1950’s, she received a B.A. degree in English from New York University before meeting and marrying Angelo Meriwether, a Los Angeles teacher. Although this marriage and a later marriage to Earle Howe ended in divorce, Louise continues to use the Meriwether name. In 1965, Louise earned an M.A. degree in journalism from the University of California at Los Angeles.

Meriwether was hired by Universal Studios in the 1950’s to became the first black story analyst in Hollywood’s history. Beginning in the early 1960’s, Meriwether also wrote and published articles in the Los Angeles Sentinel on African Americans such as opera singer Grace Bumbry, Attorney Audrey Boswell, and Los Angeles jurist, Judge Vaino Spencer. In 1967, Meriwether joined the Watts Writers’ Workshop (a group created in response to the Watts Riot of 1965) and worked as a staff member of that project.

Her first book, Daddy Was a Number Runner, a fictional account of the economic devastation of Harlem in the Great Depression, appeared in 1970 as the first novel to emerge from the Watts Writers’ Workshop. It received favorable reviews from authors James Baldwin and Paule Marshall. Daddy Was a Number Runner, is a fictional account of the historical and sociological devastation of the economic Depression on Harlem residents.

#racisminamerica#hatred#policebrutality#policeviolence#racialprofiling#racialtrauma#injustices#policemurders#corruptpoliticians

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

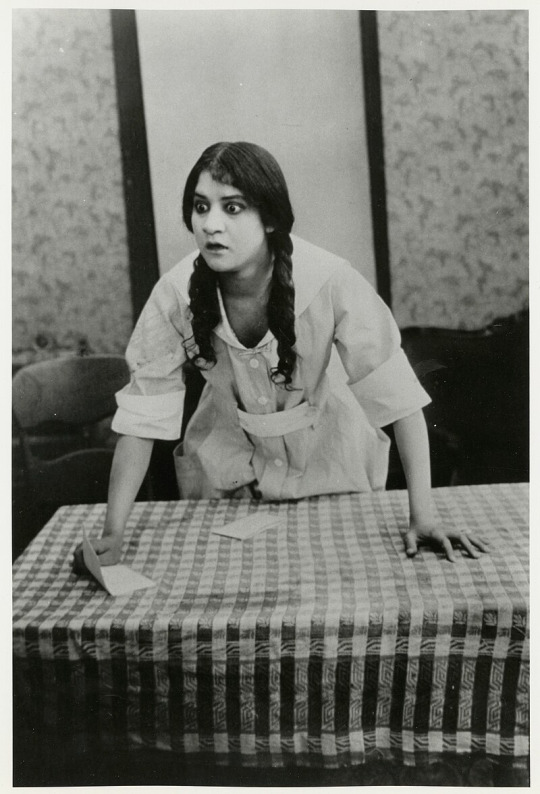

Evelyn Preer

Evelyn Preer (née Jarvis; July 26, 1896 – November 17, 1932), was an African American pioneering screen and stage actress, and jazz and blues singer in Hollywood during the late-1910s through the early 1930s. Preer was known within the Black community as "The First Lady of the Screen."

She was the first Black actress to earn celebrity and popularity. She appeared in ground-breaking films and stage productions, such as the first play by a black playwright to be produced on Broadway, and the first New York–style production with a black cast in California in 1928, in a revival of a play adapted from Somerset Maugham's Rain.

Evelyn Jarvis was born in Vicksburg, Mississippi, on July 26, 1896. After her father, Frank, died prematurely, she moved with her mother, Blanche, and her three other siblings to Chicago, Illinois. She completed grammar school and high school in Chicago. Her early experiences in vaudeville and "street preaching" with her mother are what jump-started her acting career. Preer married Frank Preer on January 16, 1915, in Chicago.

At the age of 23, Preer's first film role was in Oscar Micheaux's 1919 debut film The Homesteader, in which she played Orlean. Preer was promoted by Micheaux as his leading actress with a steady tour of personal appearances and a publicity campaign, she was one of the first African American women to become a star to the black community. She also acted in Micheaux's Within Our Gates (1920), in which she plays Sylvia Landry, a teacher who needs to raise money to save her school. Still from the 1919 Oscar Micheaux film Within Our Gates.

In 1920, Preer joined The Lafayette Players a theatrical stock company in Chicago that was founded in 1915 by Anita Bush, a pioneering stage and film actress known as “The Little Mother of Black Drama". Bush and her troupe toured the US to bring legitimate theatre to black audiences at a time when theaters were racially segregated by law in the South, and often by custom in the North and the interest of vaudeville was fading. The Lafayette Players brought drama to black audiences, which caused it to flourish until its end during the Great Depression.

She continued her career by starring in 19 films. Micheaux developed many of his subsequent films to showcase Preer's versatility. These included The Brute (1920), The Gunsaulus Mystery (1921), Deceit (1923), Birthright (1924), The Devil’s Disciple (1926), The Conjure Woman (1926) and The Spider's Web (1926). Preer had her talkie debut in the race musical Georgia Rose (1930). In 1931, she performed with Sylvia Sidney in the film Ladies of the Big House. Her final film performance was as Lola, a prostitute, in Josef von Sternberg's 1932 film Blonde Venus, with Cary Grant and Marlene Dietrich. Preer was lauded by both the black and white press for her ability to continually succeed in ever more challenging roles, "...her roles ran the gamut from villain to heroine an attribute that many black actresses who worked in Hollywood cinema history did not have the privilege or luxury to enjoy." Only her film by Micheaux and three shorts survive. She was known for refusing to play roles that she believed demeaned African Americans.

By the mid-1920s, Preer began garnering attention from the white press, and she began to appear in crossover films and stage parts. In 1923, she acted in the Ethiopian Art Theatre's production of The Chip Woman's Fortune by Willis Richardson. This was the first dramatic play by an African-American playwright to be produced on Broadway, and it lasted two weeks. She met her second husband, Edward Thompson, when they were both acting with the Lafayette Players in Chicago. They married February 4, 1924, in Williamson County, Tennessee. In 1926, Preer appeared on Broadway in David Belasco’s production of Lulu Belle. Preer supported and understudied Lenore Ulric in the leading role of Edward Sheldon's drama of a Harlem prostitute. She garnered acclaim in Sadie Thompson in a West Coast revival of Somerset Maugham’s play about a fallen woman.

She rejoined the Lafayette Players for that production in their first show in Los Angeles at the Lincoln Center. Under the leadership of Robert Levy, Preer and her colleagues performed in the first New York–style play featuring black players to be produced in California. That year, she also appeared in Rain, a play adapted from Maugham's short story by the same name.

Preer also sang in cabaret and musical theater where she was occasionally backed by such diverse musicians as Duke Ellington and Red Nichols early in their careers. Preer was regarded by many as the greatest actress of her time.

Developing post-childbirth complications, Preer died of pneumonia on November 17, 1932, in Los Angeles at the age of 36. Her husband continued as a popular leading man and "heavy" in numerous race films throughout the 1930s and 1940s, and died in 1960.

Their daughter Edeve Thompson converted to Catholicism as a teenager. She later entered the Sisters of St. Francis of Oldenburg, Indiana, where she became known as Sister Francesca Thompson, O.S.F., and became an academic, teaching at both Marian University in Indiana and Fordham University in New York City.

Still from the 1919 Oscar Micheaux film Within Our Gates.

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Human AU Blade Headcanons No One Asked For

This guy has been listening to AC/DC since he was a kid in the late 70s. The records in tower are his, and Patch takes very good care of them.

Mayday encouraged Blade to keep his pilot's license and choose a career in fire where he could use it. He also helped Blade out of a grief spiral after Nick died, and Blade thinks of him as a mentor figure.

Blade has a natural intelligence for problem solving.

While Blade wants nothing to do with his fame or acting career, he still appreciates acting as an art form. He enjoys watching movies with other people to discuss afterwards, but he struggles to invite others to do it with him.

He might not wear it outwardly, but Blade is a total aviation nerd. That man loves rotary aircraft and anything else that flies.

(more depressing stuff below the cut)

Blade grew up in San Fran and became familiar with American West Coast culture at an early age. Like many young men in the 80s, he was involved in gay nightlife. Unfortunately, Blade chose to pull away from the community when more and more of his buddies were falling ill. It was difficult for him to stay around that despair, and he'd also need that separation in case his acting career blew up.

The only people who knew about Blade's relationship with Nick were Nick's parents, who accepted him as a member of their small family. Nick's parents suffered from health issues, so Blade would pitch in around their house like second son during visits. He even learned some of their family recipes.

See this post.

Blade spent so much time with Nick that he picked up small pieces of his East Harlem dialect, like his use of the word "ain't." He also learned a couple Spanish phrases from being around Nick's family, but they're specific to the Caribbean variant that's spoken in Puerto Rico.

Blade has a collection of Polaroid photos that feature his relationship with Nick.

Lot's of people in Hollywood, and even at Piston Peak, speculate about what went on with Blade and Nick. Blade wants to reveal more about their relationship, but first, he needs to think of a plan. He wants it to special and on his own terms.

#disney planes#blade ranger#planes human au#planes fire and rescue#planes headcanons#planes with nebbs#nebbs's headcanons

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black History Month:Day 06

So I drew Dora Lee Jones-She was born in 1890.She was at first a maid and a housekeeper that had very awful working conditions.At the time only few employment options being available during the Great Depression,Black women would gather and wait in certain places and wait for white middle class women to hire them for horrible wages,and so to fight against the slave market in 1934.She helped found the Domestic Workers Union in Harlem,New York (She was the director and the lead orgainzier of DWU) and the union would call for a minimum wage,overtime and inclusion in Social Security and 2 week termination notice.The Union's contracts set rates ane boundaries for each domestic work job.And the union was very highly politically involved and would collaborate with labour focued political parties.DWU also affiliated with Services Employees International Union.

She died in 1972.

Her motto was 'Every Household worker a union worker)

Materials used:Soft pastel crayons , HB pencil and 8B pencil

Honestly I was surprised I couldn't find much more about her,at least she helped the black employees get better work treatment...and it's sad to see history trying to repeat itself in the present.

#black history month 2025#black history#black history month#equal rights#job rights#black lives matter#Dora Lee Jones

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I saw something today that really pissed me off and hurt my feelings and it's probably going to be my supervillain or origin story. I don't know how much y'all know about what happened to my dog Harlem. I mentioned how much I miss her but she's not dead. She was rehomed to a lovely guy and he's spoiling the hell out of her so now she gets three meals a day rather than the two that I was giving her. I know where she is I know she's happy and getting all the walks and love and food she needs. He adores the hell out of her and is always happy to update me on how she's doing. It's not the same but at least it's the best outcome from having to rehome her. The reason I rehomed her was because there was some issues with the landlord and they said that she was unauthorized as the excuse to say I had to either remove my dog or remove myself from the house. And because at the time I had just got a new job and had no savings or no way to move, Harlem unfortunately had to find a new place to go. Realistically I knew that I couldn't hope somebody would Foster her until I can move out into a new place because I know how hard it is to move anywhere and where I live is already low income housing and it takes up half of my paycheck every month. Anyway I just saw a picture of my apartment complex showing that they are leasing new apartments and there is a sign on there say that pet stay for free. When they claim that she was unauthorized it was due to my lease being 6 months at first and then it went to a month-to-month lease but I didn't see the new month to month lease and it's possible that the least didn't have Harlem on there as my pet because I did pay the pet deposit when I moved in. And my 6 month lease that I initially signed didn't specify that the amount of money I paid included but pet deposit and it did not specify that Harlem was going to be in the home with me as my pet. So I could not fight it that I pay the deposit nor could I fight to get the money back after she was gone cuz they claim that she wasn't on the lease at all to begin with. I just could not fight it because I didn't have any paper trail to protect me and Harlem and unfortunately I was in the process of trying to get some kind of paperwork that showed that she was my emotional support companion dog due to my depression and stuff but that didn't go through at the time. So long story short I lost her. Fast forward today I see that they are leasing and they're showing that pets stay free. So now it feels like I lost Harlem for nothing. I'm so upset and angry but I'm mostly just so sad and I can't stop crying cuz I miss her and this has fucked me up from wanting to ever get a pet again because I feel like I failed her. I had promised Harlem that I would be her last human when I adopted her as a senior dog 8 years ago and I had her for 7 years and I thought I was going to be her last human. I thought she was only going to live another three four years after I adopted her because her breed is 15 years and the shelter told me she was 12, so when she turned 16 17 18 I was like hell yeah baby girl go. It's fucked me up from getting another dog. I won't for a long time if ever and definitely not while Harlem is still alive.

I could really use a friend right now.

Hey Death Note I got some names for you...

9 notes

·

View notes