#Global Essay Competition

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

XLRI Jamshedpur HRM Student Shresth Tiwari Wins Global Essay Competition

XLRI Jamshedpur’s Shresth Tiwari triumphs at the 53rd St. Gallen Symposium in Switzerland, highlighting concerns about data practices in the metaverse. Shresth Tiwari from XLRI Jamshedpur’s HRM batch of 2023-25 has won the prestigious Global Essay Competition at the 53rd St. Gallen Symposium held in Switzerland. JAMSHEDPUR – XLRI Jamshedpur proudly congratulates Shresth Tiwari, a student from the…

#Academic Excellence#शिक्षा#data ethics#education#Global Essay Competition#HRM Batch#individual rights#Leader of Tomorrow#metaverse#Shresth Tiwari#St. Gallen Symposium#XLRI Jamshedpur

0 notes

Text

Women, Work, and the Future of Japan: A Catalyst for Change

Japan's post-war economic resurgence was once driven by its distinct work culture, but this same culture has now transformed into a double-edged sword, imperiling the nation's future prosperity. Historically, Japan's collectivist ethos, rooted in the pursuit of "Wa" (harmony), fostered stability and cooperation, but in today's context, it often manifests as a rigid hierarchy where excessively long working hours are misconstrued as the pinnacle of loyalty and dedication. This has severe human consequences, including "karoshi" (death from overwork), plummeting birth rates, and a dwindling workforce.

The country's inherent risk aversion, stemming from a deep respect for tradition, hinders innovation, with the fear of disrupting social balance outweighing the benefits of progress. This is evident in Japan's struggles to keep pace with global technological advancements, particularly in software and artificial intelligence, leading to stagnation and erosion of its competitive edge. Furthermore, traditional workplaces prioritize visibility and seniority over merit, resulting in ineffectual leadership, misguided decision-making, and a brain drain as talented individuals seek opportunities abroad.

Recent government initiatives aimed at improving work-life balance and promoting sustainability offer hope, as do forward-thinking companies adopting flexible work arrangements to attract top talent. However, a profound cultural shift is necessary for Japan to reclaim its innovative forefront. This requires blending cherished traditions with the uncertainties of innovation, fostering an environment that encourages risk tolerance, creativity, and merit-based advancement. A gradual shift in societal values, emphasizing individual creativity alongside collectivist principles, is crucial, as are structural reforms in workplaces and educational institutions promoting meritocracy, flexibility, and lifelong learning.

Interwoven with these challenges is the complex situation of Japanese women, who face traditional expectations, societal pressures, and workplace demands that profoundly impact their lives and the country's future. The notion of "ikigai" (finding purpose in life) often narrowly translates to family devotion for women, leading to unfulfilled potential and stagnation. This results in low labor force participation rates, a persistent glass ceiling, and underutilized parental leave policies, placing an undue burden on women and threatening individual well-being and the broader social and economic landscape.

A growing pushback against these traditional expectations, marked by women-led startups, flexible work arrangements, and paternal leave initiatives, signals a tentative shift towards inclusivity. To truly empower Japanese women, however, a profound societal transformation is needed, involving a reckoning with outmoded gender roles. Education and awareness campaigns, alongside the promotion of male allies embodying modern masculinity, can challenge these norms. By celebrating the diverse contributions and aspirations of its female population, Japan can dismantle barriers, realizing the full potential of its women and securing a vibrant future for the nation. The path forward hinges on choosing between the status quo and a new trajectory that values, supports, and empowers Japanese women to thrive, ultimately determining the country's prosperity.

Japanese work culture is unsustainable (pigallisme, April 2024)

youtube

Sunday, December 1, 2024

#japan work culture#innovation#tradition#social change#gender equality#economic prosperity#labor reform#societal norms#cultural evolution#east asian studies#future workforce#work-life balance#leadership development#organizational change#asian economy#global competitiveness#women in the workforce#japanese society#modernization challenges#video essay#ai assisted writing#machine art#Youtube

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay. I've been playing Tokyo Debunker today, since the release happened to catch me on a day when all I'd planned to do was write fanfiction. I just finished reading the game story prologue (it was longer than expected!), so here's a review type post. If you're reading this post not having seen a single thing about this game: it's a story-based joseimuke gacha mobile game that just released globally today. It's about a girl who suddenly finds herself attending a magic school and mingling with elite, superhuman students known as ghouls. If you look in the tumblr tag for the game you'll see what appears to be a completely different game from 2019 or so: they retooled it completely midway through development, changing just about everything about it due to "escalating competition within the gaming industry."

I'll talk about how this looks like a blatant twst clone at the end.

Starting with the positive: The story is charming. I enjoyed it thoroughly the entire time and am excited to read more. The mix between visual novel segments and motion comics was really nice--it broke things up and added a lot of oomph to the action or atmospheric scenes that visual novels generally lack. I like the art in the comic parts a lot. the live2d in the visual novel parts is... passable. Tone-wise, I think the story was a little bit all over the place and would like to see more of the horror that it opened on, but I didn't mind the comedic direction it went in either. The translation is completely seamless. The characters so far all have unique voices and are just super fun and cute. Of the ones who've had larger roles in the story so far, there's not a single one I dislike. It's all fully voiced in Japanese and the acting is solid. (I don't recognize any voices, and can't seem to find any seiyuu credits, so it seems they're not big names, but they deliver nonetheless.) Kaito in particular I found I was laughing at his lines a ton, both the voicing and the writing.

He's looking for a girlfriend btw. Spreading the word.

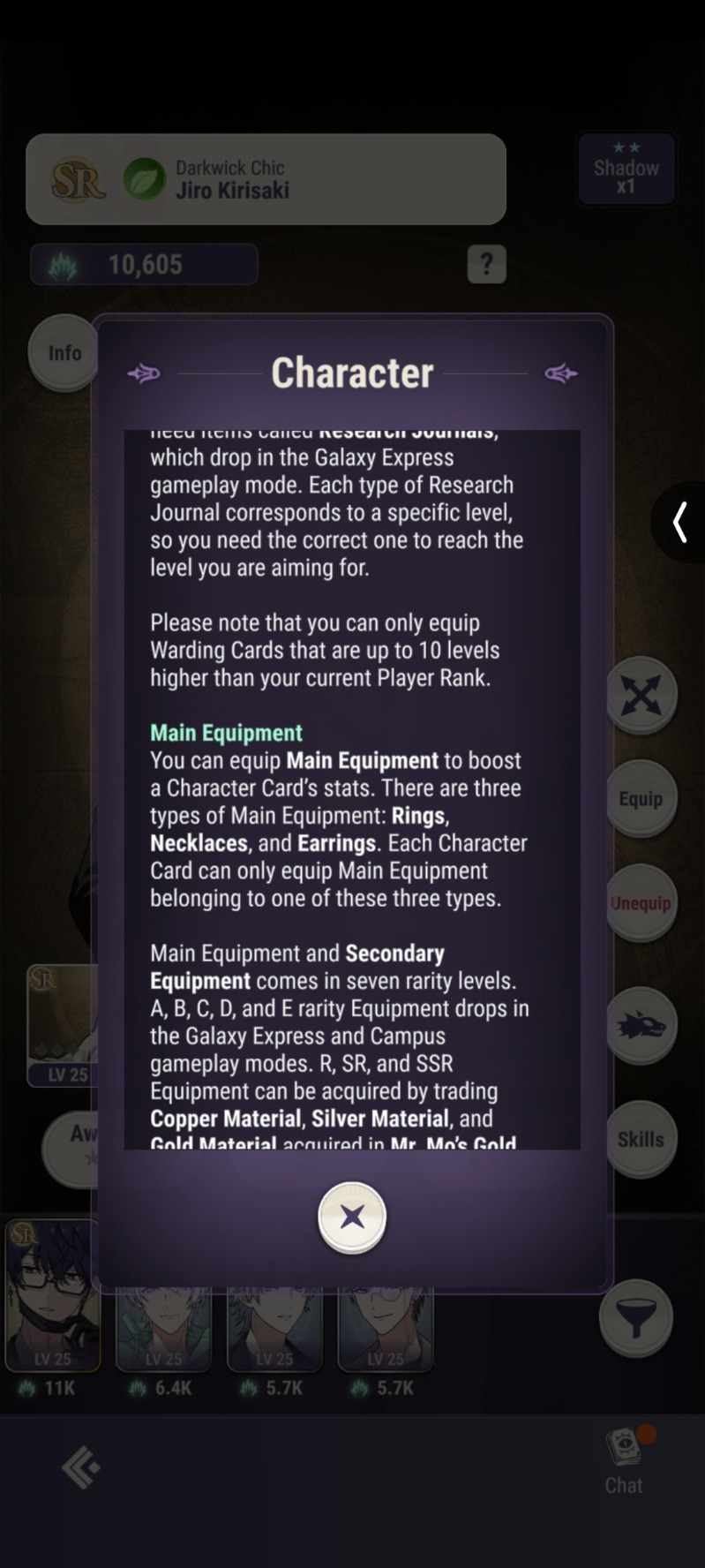

The problem is like. The gameplay is the worst dark-pattern microtransaction-riddled bullshit I've ever seen. Hundred passive timers going at all times. Fifty different item-currencies. Trying to get you to spend absurd amounts of real world money at every turn. There's like five different indicators that take you to various real-money shop items that I don't know how to dismiss the indicator, I guess you just have to spend money, wtaf. Bajillion different interlocking systems mean you have zero sense of relative value of all the different item-currencies. I did over the course of the day get enough diamonds for one ten-pull, which I haven't used yet. Buying enough diamonds for a ten-pull costs a bit under $60 (presumably USD, but there's a chance the interface is automatically making that CAD for me--not gonna spend the money to check lmfao), with an SSR rate of 1%. BULLSHIIIIIT.

There's like a goddamn thousand-word essay explaining the dozen different types of character upgrades and equippables and equippables for the equippables!! Bad! Bad game design! That's just overcomplicating bullshit to trick people into thinking they're doing something other than clicking button to make number go up! That is not gameplay!

In terms of the actual gameplay, there is none. The battle system is full auto. There might be teambuilding, but from what I've seen so far, most of that consists of hoping you pull good cards from gacha and then clicking button to make number go up. There's occasional rhythm segments but there's no original music, it's just remixes of public domain classical music lmao. I'd describe the rhythm gameplay as "at least more engaging than twisted wonderland's," which is not a high bar

At least there's a cat in the rhythm bit.

And like, ok, I gotta remark on how derivative it is. Like I mentioned in my post earlier, this game is unabashedly aping twisted wonderland's setting and aesthetic. (That said, most of the stuff it steals from twst is magic school stuff that twst also basically stole from Harry Potter, so...?) However, it isn't exactly like twst: in this one, the characters say fuck a lot and bleed all over the place and do violence. Basically, the tone is a fair bit more adult than twst's kid-friendly vibe. (Not, like, adult adult, and I probably wouldn't even call it dark--it's still rated Teen lol. Just more adult than twst.)

Rather than just being students at magic school, the ghouls also go out into the mundane world to go on missions where they fight and investigate monsters and cryptids. Honestly, the magic school setting feels pretty tacked-on. The things that are enjoyable about this would've been just as enjoyable in about any other setting--you can tell this whole aspect was a late trend-chasing addition, lmao. So, yeah, it's blatantly copying twst to try to steal some players, but... Eh, I found myself not caring that much. Someone more (or less) into twst than me may find it grating.

Character-wise, eh, sure, yeah, they're a bit derivative in that aspect too, but it's a joseimuke game, the characters are always derivative. Thus far the writing & execution has been solid enough that I didn't care if they were tropey. If I were to compare it to something else, I'd say the relationship between the protagonist and the ghouls feels more like that of the sage and wizards in mahoyaku than anything from twst. There's some mystery in exactly what "ghouls" are and their place in this world that has me intrigued and wanting to know more about this setting and how each of the characters feels about it. I have a bad habit of getting my hopes up for stories that put big ideas on the table and then being disappointed when they don't follow through in a way that lives up to my expectations, though.

So, my final verdict: I kind of just hope someone uploads all the story segments right onto youtube so nobody has to deal with the dogshit predatory game to get the genuinely decent story lol. Give it a play just for the story if you have faith in your ability to resist dark patterns. Avoid at all costs if you know you're vulnerable to gacha, microtransactions, or timesinks.

#suchobabbles#Tokyo Debunker#it's a global simultaneous release so I'm curious to see how it ends up doing in Japan#it's gonna be competing directly with stellarium of the fragile star which releases in a few days lmao. and is about a magic alchemy school#looks like the two games twt accounts have a similar number of followers#and then theyre competing with bremai releasing in may...#also adding this at the very end since i cant confirm anything:#but i found out abt this game bc it was rt'd by the former localization director/translator of A3en#i dont know if she worked on it or maybe her friend or maybe shes just hype! who knows! but i think her word (or rt) is worth something

168 notes

·

View notes

Note

hello! do you have any recs about the railways in India?

i do, actually! here you go:

Building the Railways of the Raj, 1850-1900 and Railways in Modern India by Ian Kerr: good places to start with if you want a historical view of the railways and the political economy around them. Ian Kerr has done a lot of work on the railways, so you should definitely check him out

The Great Railway Bazaar by Paul Theroux: not strictly India, but it does include India/the subcontinent; one of my favourite travelogues

Economic Change and the Railways in North India, 1860–1914 by Ian Derbyshire: this is an essay, also historical

Railways and the expansion of markets in India, 1861–1921 by John Hurd: kind of on the same lines as the one before in terms of its content

Border Region Railway Development in Sino-Indian Geopolitical Competition by Chitresh Shrivastava, Stabak Roy and Dhruv Ashok: really interesting thing about the strategic function that railways in borderlands play

Dirty Tracks Across the Border: Global Operations of Extraction, Labour and Migration at a Railway Station on the Bihar–Nepal Border by Mithilesh Kumar: about the cross-border labour market, how the railways feed into this, and the geopolitical competition around it

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

chat i'm actually cooking this year i came third in a global economics essay competition

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

On September 16th the Edinburgh publisher William Blackwood died.

Blackwood was Scotland’s most successful publisher in the early nineteenth century. He was born in Edinburgh and at the age of fourteen began a six year apprenticeship to the booksellers Bell & Bradfute. Following further training in Glasgow and London, he opened his first shop on South Bridge Edinburgh. Specialising in selling rare books the business was a success.

In 1813 Blackwood became the agent for the printers of Sir Walter Scott’s novels. Four years later he founded the ‘Edinburgh Monthly Magazine’ as a counterpart to the ‘Edinburgh Review. As editor from the seventh issue onwards the magazine became known as ‘Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine’, the periodical began to scandalise and captivate readers with its critical essays and reviews.

A number of lawsuits were brought against the magazine for its personal attacks on public figures.

As well as the controversial articles it the magazine became a platform for many literary talents, publishing work by writers including James Hogg, Margaret Oliphant and George Eliot.

During the First World War, 'Blackwood's' published stories that reflected the global conflict.

The magazine also saved lives. In 1841, a copy took the brunt of a sword blow in the Afghan War, turning a fatal strike into a superficial one. In 1918, a copy in the breast pocket of an officer's jacket absorbed the impact of a bullet.

'Blackwood's' continued publication through most of the 20th century until it ceased in 1980.

A fall in readership combined with stiff competition from emerging illustrated journals caused the magazine to close.

William Blackwood is buried in the Old Calton Cemetery in Edinburgh.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Clean Energy Revolution Is Unstoppable. (Wall Street Journal)

Surprising essay published by the Wall Street Journal. Actually, two surprises. The first is an assertion that the fossil fuel industry is parading to its death, regardless of the current trump mania, while the renewables industry is marching toward success due to dramatic decreases in cost. The second surprise is that the essay is published in the Wall Street Journal, which we all know can be a biblical equivalent for the right wing. But be careful with that right wing label: today's right wing (e.g., MAGA) or the traditional conservative republican right wing, which is more aligned with saving money and making money and avoiding political headwinds.

Here's the entire essay. I rarely post a complete essay, but this one made me happy and feel good, and right now I/we damn well need to learn something to make us happy and feel good.

Since Donald Trump’s election, clean energy stocks have plummeted, major banks have pulled out of a U.N.-sponsored “net zero” climate alliance, and BP announced it is spinning off its offshore wind business to refocus on oil and gas. Markets and companies seem to be betting that Trump’s promises to stop or reverse the clean energy transition and “drill, baby, drill” will be successful.

But this bet is wrong. The clean energy revolution is being driven by fundamental technological and economic forces that are too strong to stop. Trump’s policies can marginally slow progress in the U.S. and harm the competitiveness of American companies, but they cannot halt the fundamental dynamics of technological change or save a fossil fuel industry that will inevitably shrink dramatically in the next two decades.

Our research shows that once new technologies become established their patterns in terms of cost are surprisingly predictable. They generally follow one of three patterns.

The first is a pattern where costs are volatile over days, months and years but relatively flat over longer time frames. It applies to resources extracted from the earth, like minerals and fossil fuels. The price of oil, for instance, fluctuates in response to economic and political events such as recessions, OPEC actions or Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But coal, oil and natural gas cost roughly the same today as they did a century ago, adjusted for inflation. One reason is that even though the technology for extracting fossil fuels improves over time, the resources get harder and harder to extract as the quality of deposits declines.

There is a second group of technologies whose costs are also largely flat over time. For example, hydropower, whose technology can’t be mass produced because each dam is different, now costs about the same as it did 50 years ago. Nuclear power costs have also been relatively flat globally since its first commercial use in 1956, although in the U.S. nuclear costs have increased by about a factor of three. The reasons for U.S. cost increases include a lack of standardized designs, growing construction costs, increased regulatory burdens, supply-chain constraints and worker shortages.

A third group of technologies experience predictable long-term declines in cost and increases in performance. Computer processors are the classic example. In 1965, Gordon Moore, then the head of Intel, noticed that the density of electrical components in integrated circuits was growing at a rate of about 40% a year. He predicted this trend would continue, and Moore’s Law has held true for 60 years, enabling companies and investors to accurately forecast the cost and speed of computers many decades ahead.

Clean energy technologies such as solar, wind and batteries all follow this pattern but at different rates. Since 1990, the cost of wind power has dropped by about 4% a year, solar energy by 12% a year and lithium-ion batteries by about 12% a year. Like semiconductors, each of these technologies can be mass produced. They also benefit from advances and economies of scale in related sectors: solar photovoltaic systems from semiconductor manufacturing, wind from aerospace and batteries from consumer electronics.

Solar energy is 10,000 times cheaper today than when it was first used in the U.S.’s Vanguard satellite in 1958. Using a measure of cost that accounts for reliability and flexibility on the grid, the International Energy Agency (IEA) calculates that electricity from solar power with battery storage is less expensive today than electricity from new coal-fired plants in India and new gas-fired plants in the U.S. We project that by 2050 solar energy will cost a tenth of what it does today, making it far cheaper than any other source of energy.

At the same time, barriers to large-scale clean energy use keep tumbling, thanks to advances in energy storage and better grid and demand management. And innovations are enabling the electrification of industrial processes with enormous efficiency gains.

The falling price of clean energy has accelerated its adoption. The growth of new technologies, from railroads to mobile phones, follows what is called an S-curve. When a technology is new, it grows exponentially, but its share is tiny, so in absolute terms its growth looks almost flat. As exponential growth continues, however, its share suddenly becomes large, making its absolute growth large too, until the market eventually becomes saturated and growth starts to flatten. The result is an S-shaped adoption curve.

The energy provided by solar has been growing by about 30% a year for several decades. In theory, if this rate continues for just one more decade, solar power with battery storage could supply all the world’s energy needs by about 2035. In reality, growth will probably slow down as the technology reaches the saturation phase in its S-curve. Still, based on historical growth and its likely S-curve pattern, we can predict that renewables, along with pre-existing hydropower and nuclear power, will largely displace fossil fuels by about 2050.

For decades the IEA and others have consistently overestimated the future costs of renewable energy and underestimated future rates of deployment, often by orders of magnitude. The underlying problem is a lack of awareness that technological change is not linear but exponential: A new technology is small for a long time, and then it suddenly takes over. In 2000, about 95% of American households had a landline telephone. Few would have forecast that by 2023, 75% of U.S. adults would have no landline, only a mobile phone. In just two decades, a massive, century-old industry virtually disappeared.

If all of this is true, is there any need for government support for clean energy? Many believe that we should just let the free market alone sort out which energy sources are best. But that would be a mistake.

History shows that technology transitions often need a kick-start from government. This can take the form of support for basic and high-risk research, purchases that help new technologies reach scale, investment in infrastructure and policies that create stability for private capital. Such government actions have played a critical role in virtually every technological transition, from railroads to automobiles to the internet.

In 2021-22, Congress passed the bipartisan CHIPS Act and Infrastructure Act, plus the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), all of which provided significant funding to accelerate the development of the America’s clean energy industry. Trump has pledged to end that support. The new administration has halted disbursements of $50 billion in already approved clean energy loans and put $280 billion in loan requests under review.

The legality of halting a congressionally mandated program will be challenged in court, but in any case, the IRA horse is well on its way out of the barn. About $61 billion of direct IRA funding has already been spent. IRA tax credits have already attracted $215 billion in new clean energy investment and could be worth $350 billion over the next three years.

Ending the tax credits would be politically difficult, since the top 10 states for clean energy jobs include Texas, Florida, Michigan, Ohio, North Carolina and Pennsylvania—all critical states for Republicans. Trump may find himself fighting Republican governors and members of Congress to make those cuts.

It is more likely that Trump and Congress will take actions that are politically easier, such as ending consumer subsidies for electric vehicles or refusing to issue permits for offshore wind projects. The impact of these policy changes would be mainly to harm U.S. competitiveness. By reducing support for private investment and public infrastructure, raising hurdles for permits and slapping on tariffs, the U.S. will simply drive clean-energy investment to competitors in Europe and China.

Meanwhile, Trump’s promises of a fossil fuel renaissance ring hollow. U.S. oil and gas production is already at record levels, and with softening global prices, producers and investors are increasingly cautious about committing capital to expand U.S. production.

The energy transition is a one-way ticket. As the asset base shifts to clean energy technologies, large segments of fossil fuel demand will permanently disappear. Very few consumers who buy an electric vehicle will go back to fossil-fuel cars. Once utilities build cheap renewables and storage, they won’t go back to expensive coal plants. If the S-curves of clean energy continue on their paths, the fossil fuel sector will likely shrink to a niche industry supplying petrochemicals for plastics by around 2050.

For U.S. policymakers, supporting clean energy isn’t about climate change. It is about maintaining American economic leadership. The U.S. invented most clean-energy technologies and has world-beating capabilities in them. Thanks to smart policies and a risk-taking private sector, it has led every major technological transition of the 20th century. It should lead this one too.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Master post (& fics I’m planning to write)

Ladies and Gentlemen: My take on Adrien having his own antagonist like Marinette has Lila and Chloe. A new transfer students makes an enemy of the entire class, but Adrien seems to be his main target.

Part 1 Part 2 Headcannons

Status: Completed (maybe)

Let Her Eat Cake: A one shot in which Lila is exposed as Hawkmoth’s ally, which opens up questions about Francois DuPont. In other words, Bustier is accused of being Mayura.

Read Here

Status: Completed

Lila’s Reflection: A one shot in which Lila has a twin sister who she feels inferior against. Includes Lilanette, Male Marinette, and Lila angst.

Read Here

Status: Completed

Marion Dupain-Cheng: Ice Cold: So we know the umbrella scene where Adrien basically pulls his “sad boy” card to make Marinette feel bad for him? Realistically, she shouldn’t have fallen in love with him just like that. I think she should have been wary of him because of his association with Chloe or outright hate him after he scolded her for being happy that Chloe was leaving. Or in ’Bubbler’ when all he cared about was having a party and not that adults we’re literally being launched into the sky. Or in ‘Despair Bear’ after a day of forced niceties he laughed when Chloe insulted Mylene’s macaroons. Long story short, Marinette shouldn’t have tolerated Adrien for as long as she did much less have a crush on him. If she did, it should’ve been obliterated by now. (This is a Drabble)

Read Here

Status: Completed

A Beetle’s Blossom: The members of the Justice League have seen many things. The deaths and resurrection of some of their comrades, alien doomsdays, off planet missions, and the literal destruction of the world. But the boy who *strongly* resembles Bruce in more ways than just his appearance has them stumped, especially Bruce himself.

On AO3

Status: On going

Fics That Are Coming Soon

The Most Hated Girl in Paris: An AU where instead of getting off Scott free, Chloe is legally punished for the Train Incident and has to deal with the fact that’s she’s Paris’ most hated girl. She must decide if she wants to continue living this way or if she’s going to claw her way to redemption. Long term project.

Tumblr Concept

Status: Not started

Not So Miraculous After all: Tired of citizens justifying their reckless behavior with the Miraculous Cure, Ladybug stops using it, making sure that consequences get left behind.

Status: Not Started

The Fall of A Queen (C. Bourgeois): An Au where Andre isn’t re-elected as Mayor. This changes everything. Long term project.

Status: Not Started

Cuisine Paradise: Seeing as both their parents work in the food industry, Alya and Marinette decide to start a YouTube channel together to share their recipes; Marinette’s pastries and Alya’s dinner recipes. It all in good fun and they accidentally become famous. Long term project.

Status: Not Started

New Boy In Town (Remy Gasteau): The son of the Prime Minister transfers to Francois DuPont and takes an interest in Marinette. Extremely long term project.

Based on an ask I submitted to @mcheang

Status: Not Started

Civil War (Paris Edition): No matter how hard Lila tries, the class refuses to turn against Marinette, believing that Lila was just confused and there was a misunderstanding. In an attempt to get the girls to help her with Adrien, she insists that Marinette would go great with Luka. It was a brilliant plan— until war breaks out over the class. Lukanette vs Adrienette. Short term project.

Status: Not Started

Round the World Trip: After winning a series of contests, essay challenges, and competitions, Marion unintentionally earned his class a fully paid global trip over summer vacation. Includes Male Marinette and shenanigans. Mid-length project.

Status: Not Started

Damian’s Secret Brother: After ruining any chance at a brotherly relationship with Tim after his murder attempts, Damian Wayne is determined to prove that he wasn’t just a brutish assassin. The discovery of his newest biological brother provided him with the opportunity to show everyone that he could be civil with new family members. But he didn’t think he would get attached to the friendly baker’s boy who had ambitions to be a fashion designer. Male Marinette and bio-dad Bruce Wayne. Mid-length project.

Status: Not Started

#ml au#miraculous fanfiction#miraculous fanfic#ml salt#ml sugar#ml writers salt#masterpost#going to write later#Cannon has failed so I am its new master#but school is annoying so it’ll have to wait until summer#ml masterpost

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

Inside Harvard University Results: What They Mean and Why They Matter

Harvard University, established in 1636, is renowned internationally for its instructional excellence, rigorous curriculum, and legacy of producing international leaders. As one of the Ivy League institutions, its standards for assessment and the consequences it publishes reflect its commitment to highbrow rigor and innovation. This article explores Harvard University’s result framework, offering insights into admissions results, academic opinions, grading structures, and their importance inside the broader context of higher education.

Harward University Result

The Context of Harvard Results: Admissions

One of the most giant results at Harvard University pertains to its admissions technique. With an attractiveness fee that hovers around 3-five% in recent years, the outcome of the admission choice is an eagerly awaited result for hundreds of excessive-achieving college students globally. Let us delve deeper into how those results unfold.

The Application Process

Harvard University’s admissions method is holistic, considering a mixture of instructional achievements, extracurricular involvements, essays, guidelines, and interviews. The Office of Admissions evaluates every application to recognize the applicant’s character, ability, and health for the university’s dynamic environment.

Admissions Results Announcement

Admissions choices are usually launched in 3 phases:

Early Action (December): For students who follow in the early spherical. Although non-binding, this section allows students to get an early selection.

Regular Decision (March/April): The majority of applicants get hold of their decision throughout this segment.

Waitlist and Rolling Admissions (May-July): Candidates on the waitlist can also get hold of a proposal based on area availability.

Results are communicated via an internet portal and are regularly accompanied by way of a respectable letter. The results encompass recognition, deferral (for early applicants), waitlist, or denial.

Acceptance Trends

In current years, Harvard has reported a regular rise in applications, leading to extended competitiveness. Results replicate a diverse, talented cohort, with successful candidates excelling academically and demonstrating management in numerous fields.

Academic Results at Harvard

Harvard University’s instructional results encapsulate the overall performance of its students across undergraduate, graduate, and professional packages. These results represent the fruits of rigorous coursework, research initiatives, and examinations.

Grading System

Harvard employs a letter grading system, complemented through qualitative feedback in lots of guides. Here’s a breakdown:

A (Excellent): Outstanding performance and mastery of the issue.

B (Good): Strong performance with room for improvement.

C (Satisfactory): Adequate knowledge of the fabric.

D (Poor): Barely meeting the direction necessities.

E/F (Fail): Did no longer meet the minimal standards.

Additionally, a few guides allow college students to choose Pass/Fail grading, mainly for exploratory or non-center lessons.

GPA and Transcripts

The Grade Point Average (GPA) is calculated primarily based on a weighted scale, generally starting from 0.Zero to 4. Zero. Transcripts also include narrative reviews for certain programs, imparting a comprehensive picture of a pupil’s performance.

Publication of Results

Results are commonly launched at the quit of each semester via the student portal. For very last-yr college students, cumulative effects are pivotal for graduation honors and differences such as summa cum laude, magna cum laude, and cum laude.

Evaluation Framework

Academic Rigor

Harvard’s assessment device prioritizes important questioning, originality, and intellectual interest. Assessments encompass essays, trouble units, study papers, group tasks, and oral shows. Examinations frequently demand deep analytical and interpretive skills.

Continuous Assessment

Rather than relying totally on the last tests, many guides include nonstop evaluation, including quizzes, magnificence participation, and mid-term initiatives. This approach guarantees a holistic evaluation of scholar talents.

Feedback Mechanisms

Professors and coaching fellows offer detailed remarks on assignments, permitting students to refine their knowledge and performance for the duration of the semester.

Impact of Results on Students

Harvard’s academic effects profoundly affect college students' future opportunities, whether in graduate research, careers, or entrepreneurial ventures.

Graduate School and Fellowships

Outstanding consequences at Harvard regularly pave the manner for popularity into top-tier graduate programs. Many college students also secure prestigious fellowships, consisting of the Rhodes, Marshall, or Fulbright scholarships.

Career Prospects

Employers worldwide value a Harvard education. Strong academic outcomes enhance a graduate’s employability and open doorways to competitive roles in industries like finance, consulting, technology, regulation, and academia.

Alumni Achievements

Harvard’s alumni community is one of the maximum influential globally. Many graduates attribute their fulfillment to the rigorous schooling and remarks obtained all through their educational adventure at Harvard.

Special Programs and Research Results

In addition to conventional academic consequences, Harvard also publishes the effects of diverse unique programs and research projects.

5.1. Research Excellence

Harvard’s research output is a benchmark in academia. The results of faculty and scholar studies projects are regularly published in main journals and impact a wide array of disciplines.

5.2. Professional Schools

Harvard’s professional schools, inclusive of the Business School, Law School, and Medical School, preserve separate assessment and result structures. Their results are instrumental in shaping the careers of future leaders in those domain names.

Transparency and Integrity

Harvard is dedicated to maintaining the highest requirements of transparency and integrity in its evaluation tactics. Mechanisms together with nameless grading, peer evaluation, and appeals make certain fairness.

Academic Integrity

Students are expected to stick to strict codes of academic integrity. Results mirror no longer only academic competence but also moral behavior.

Reporting and Analytics

The university periodically releases reviews on aggregate educational overall performance, offering insights into tendencies and regions for development.

Global Significance of Harvard Results

Harvard’s popularity amplifies the significance of its consequences, which can be regularly viewed as a worldwide trend of excellence.

Influence on Education Systems

Many universities and institutions worldwide version their assessment frameworks on Harvard’s, emphasizing comprehensive checks and interdisciplinary getting to know.

Benchmark for Success

Results from Harvard set benchmarks for fulfillment in several fields. The group’s position in shaping global idea leaders underscores the price of its assessment system.

Challenges and Innovations

Addressing Stress

Given the competitive nature of Harvard, students often face giant stress to carry out. The college presents assets consisting of counseling and mentorship to help college students manage strain and balance their academic hobbies.

Embracing Technology

Harvard constantly integrates technology into its evaluation structures. Innovations consisting of online grading tools and studying analytics beautify the accuracy and efficiency of results.

Equity in Education

Harvard is dedicated to selling fairness. Initiatives like need-blind admissions ensure that results mirror benefits in preference to socioeconomic history.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bibliography for FAQ

Non-Anarchist Works

Adams, Arthur E., Bolsheviks in the Ukraine: the second campaign, 1918–1919, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1963

Anderson, Terry L. and Leal, Donald R., Free Market Environmentalism, Pacific Research Institute for Public Policy,San Francisco, 1991.

Anweiler, Oskar, The Soviets: The Russian Workers, Peasants, and Soldiers Councils 1905–1921, Random House, New York, 1974.

Archer, Abraham (ed.), The Mensheviks in the Russian Revolution, Thames and Hudson Ltd, London, 1976.

Arestis, Philip, The Post-Keynesian Approach to Economics: An Alternative Analysis of Economic Theory and Policy, Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd., Aldershot, 1992.

Armstrong, Philip, Glyn, Andrew and Harrison, John, Capitalism Since World War II: The making and breakup of the great boom, Fontana, London, 1984.

Capitalism Since 1945, Basil Blackwell, Oxford, 1991.

Arrow, Kenneth, “Economic Welfare and the Allocation of Resources for Inventiveness,” in National Bureau of Economic Research, The Rate and Direction of Inventive Activity, Princeton University Press, 1962.

Aves, Jonathan, Workers Against Lenin: Labour Protest and the Bolshevik Dictatorship, Tauris Academic Studies, London, 1996.

Bain, J.S., Barriers in New Competition: Their Character and Consequences in Manufacturing Industries, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1967.

Bakan, Joel, The Corporation: The Pathological Pursuit of Profit and Power, Constable, London, 2004.

Bakunin, Michael, The Confession of Mikhail Bakunin, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, N.Y., 1977.

Bukharin, Nikolai, Economy Theory of the Leisure Class, Monthly PressReview, New York/London, 1972.

Bagdikian, Ben H., The New Media Monopoly, Beacon Press, Boston, 2004.

Baldwin, William L., Market Power, Competition and Anti-Trust Policy, Irwin, Homewood, Illinois, 1987.

Balogh, Thomas, The Irrelevance of Conventional Economics,Weidenfield and Nicolson, London, 1982.

Baran, Paul A. and Sweezy, Paul M., Monopoly Capital, Monthly Press Review, New York, 1966.

Baron, Samuel H., Plekhanov: the Father of Russian Marxism, Routledge & K. Paul, London, 1963

Barry, Brian, “The Continuing Relevance of Socialism”, in Thatcherism, Robert Skidelsky (ed.), Chatto & Windus, London, 1988.

Beder, Sharon, Global Spin: The Corporate Assault on Environmentalism, Green Books, Dartington, 1997.

Beevor, Antony, The Spanish Civil War, Cassell, London, 1999.

The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936–1939, Phoenix, London, 2006.

Berghahn, V. R., Modern Germany: society, economy and politics in the twentieth century, 2nd ed., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1987.

Berlin, Isaiah, Four Essays on Liberty, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1969.

Bernstein, Michael A., The Great Depression: Delayed recovery and Economic Change in America, 1929–1939, Cambridge University Press, New York, 1987.

Beynon, Huw, Working for Ford, Penguin Education, London, 1973.

Binns, Peter, Cliff, Tony, and Harman, Chris, Russia: From Workers’ State to State Capitalism, Bookmarks, London, 1987.

Blanchflower, David and Oswald, Andrew, The Wage Curve, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1994.

Blinder, Alan S. (ed.), Paying for productivity: a look at the evidence, Brookings Institution, Washington, D.C, 1990.

Blum, William, Killing Hope: US Military and CIA Interventions Since World War II, 2nd edition, Zed Books, London, 2003.

Rogue State: A Guide to the World’s Only Superpower, 3rd edition, Zed Books, London, 2006.

Böhm-Bawerk, Eugen, Capital and Interest, Libertarian Press, South Holland,Ill., 1959.

Bolloten, Burnett, The Spanish Civil War: Revolution and Counter Revolution, Harvester-Wheatsheaf, New York, 1991.

Boucher, Douglas H. (ed.), The Biology of Mutualism: Biology and Evolution, Croom Helm , London, 1985.

Bourne, Randolph, Untimely Papers, B.W. Huebsch, New York, 1919.

War and the Intellectuals: Essays by Randolph S. Bourne 1915–1919, Harper Torchbooks, New York, 1964.

Bowles, Samuel and Edwards, Richard (Eds.), Radical Political Economy, (two volumes), Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd., Aldershot, 1990.

Bowles, Samuel and Gintis, Hebert, Schooling in Capitalist America: Education Reform and the Contradictions of Economic Life, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1976.

Braverman, Harry, Labour and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in theTwentieth Century, Monthly Review Press, New York, 1974.

Brecher, Jeremy, Strike!, South End Press, Boston, 1972.

Brecher, Jeremy and Costello, Tim, Common Sense for Hard Times, Black Rose Books, Montreal, 1979.

Brenan, Gerald, The Spanish Labyrinth: An Account of the Social and Political of the Spanish Civil War, 2nd Edition, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1976.

Broido, Vera, Lenin and the Mensheviks: The Persecution of Socialists under Bolshevism, Gower Publishing Company Limited, Aldershot, 1987.

Brovkin, Vladimir N., From Behind the Front Lines of the Civil War: political parties and social movements in Russia, 1918–1922, Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J, 1994.

The Mensheviks After October: Socialist Opposition and the Rise of the Bolshevik Dictatorship, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 1987. Russia after Lenin : politics, culture and society, 1921–1929, Routledge, London/New York, 1998

Brovkin, Vladimir N. (ed.), The Bolsheviks in Russian Society: The Revolution and Civil Wars, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1997.

Bunyan, James, The Origin of Forced Labor in the Soviet State, 1917–1921: Documents and Materials, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1967.

Byock, Jesse, Viking Age Iceland, Penguin Books, London, 2001

C.P.S.U. (B), History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks), International Publishers, New York, 1939.

Cahm, Eric and Fisera, Vladimir Claude (eds), Socialism and Nationalism, Spokesman, Nottingham, 1978–80.

Carr, Edward Hallett, The Bolshevik Revolution: 1917–1923, in three volumes, Pelican Books, 1966.

The Interregnum 1923–1924, Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1969.

Carr, Raymond, Spain: 1808–1975, 2nd Edition, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1982.

Carrier, James G. (ed.), Meanings of the market: the free market in western culture, Berg, Oxford, 1997.

Chandler, Lester V., America’s Greatest Depression, 1929–1941, Harper & Row, New York/London, 1970.

Chang, Ha-Joon, Kicking Away the Ladder: Development Strategy in Historic Perspective, Anthem Press, London, 2002.

Bad samaritans: rich nations, poor policies and the threat to the developing world, Random House Business, London, 2007

Clark, J.B., The Distribution of Wealth: A theory of wages, interest and profits, Macmillan, New York, 1927

Cliff, Tony, Lenin: The Revolution Besieged, vol. 3, Pluto Press, London,1978.

Lenin: All Power to the Soviets, vol. 2, Pluto Press, London,1976. State Capitalism in Russia, Bookmarks, London, 1988. “Trotsky on Substitutionism”, contained in Tony Cliff, Duncan Hallas, Chris Harman and Leon Trotsky, Party and Class,Bookmarks, London, 1996. Trotsky, vol. 3, Bookmarks, London, 1991. Revolution Besieged: Lenin 1917–1923, Bookmarks, London, 1987.

Cohen, Stephan F., Bukharin and the Bolshevik Revolution, Oxford University Press, London, 1980.

“In Praise of War Communism: Bukharin’s The Economics of the Transition Period”, pp. 192–203, Revolution and politics in Russia: essays in memory of B.I. Nicolaevsky, Alexander and Janet Rabinowitch with Ladis K.D. Kristof (eds.).

Collins, Joseph and Lear, John, Chile’s Free-Market Miracle: A Second Look,Institute for Food and Development Policy, Oakland, 1995.

Communist International, Proceedings and Documents of the Second Congress1920, (in two volumes), Pathfinder, New York, 1991.

Confino, Michael (ed.), Daughter of a Revolutionary: Natalie Herzen and the Bakunin-Nechayev Circle, Library Press, LaSalle Illinois, 1973.

Cowen, Tyler, “Law as a Public Good: The Economics of Anarchy”,Economics and Philosophy, no. 8 (1992), pp. 249–267.

“Rejoinder to David Friedman on the Economics of Anarchy”, Economics and Philosophy, no. 10 (1994), pp. 329–332.

Cowling, Keith, Monopoly Capitalism, MacMillian, London, 1982.

Cowling, Keith and Sugden, Roger, Transnational Monopoly Capitalism,Wheatshelf Books, Sussez, 1987.

Beyond Capitalism: Towards a New World Economic Order, Pinter, London, 1994.

Curry, Richard O. (ed.), Freedom at Risk: Secrecy, Censorship, and Repression in the 1980s, Temple University Press, 1988.

Curtis, Mark, Web of Deceit: Britain’s real role in the world,Vintage, London, 2003.

Unpeople: Britain’s Secret Human Rights Abuses,Vintage, London, 2004.

Daniels, Robert V., The Conscience of the Revolution: Communist Opposition in Soviet Russia, Harvard UniversityPress, Cambridge, 1960.

Daniels, Robert V. (ed.), A Documentary History of Communism, vol. 1,Vintage Books, New York, 1960.

Davidson, Paul, Controversies in Post-Keynesian Economics, E. Elgar, Brookfield, Vt., USA, 1991.

John Maynard Keynes, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, 2007

Davis, Mike, Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World, Verso, London, 2002.

Denikin, General A., The White Armies, Jonathan Cape, London, 1930.

DeShazo, Peter, Urban Workers and Labor Unions in Chile 1902–1927,University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, 1983.

Deutscher, Isaac, The prophet unarmed : Trotsky 1921–1929, Oxford University Press, 1959.

Devine, Pat, Democracy and Economic Planning, Polity, Cambridge, 1988.

Dobbs, Maurice, Studies in Capitalist Development, Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd., London, 1963.

Dobson, Ross V. G., Bringing the Economy Home from the Market, Black Rose Books, Montreal, 1993.

Domhoff, G. William, Who Rules America Now? A view from the ‘80s, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, 1983.

Donaldson, Peter, A Question of Economics, Penguin Books, London, 1985.

Economics of the Real World, 3rd edition, Penguin books, London, 1984.

Dorril, Stephen and Ramsay, Robin, Smear! Wilson and the Secret State, Fourth Estate Ltd., London, 1991.

Douglass, Frederick, The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass, vol. 2, Philip S. Foner (ed.) International Publishers, New York, 1975.

Draper, Hal, The ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ from Marx to Lenin, Monthly Review Press, New York, 1987.

The Myth of Lenin’s “Concept of The Party”, available at: http://www.marxists.org/archive/draper/works/1990/myth/myth.htm

Du Boff, Richard B., Accumulation and Power: an economic history of the United States, M.E. Sharpe, London, 1989.

Dubois, Pierre, Sabotage in Industry, Penguin Books, London, 1979.

Eastman, Max, Since Lenin Died, Boni and Liveright, New York, 1925.

Eatwell, Roger and Wright, Anthony (eds.), Contemporary political ideologies, Pinter, London, 1993.

Edwards, Stewart, The Paris Commune 1871, Victorian (& Modern History) Book Club, Newton Abbot, 1972.

Edwards, Stewart (ed.), The Communards of Paris, 1871, Thames and Hudson, London, 1973.

Eisler, Rianne, Sacred Pleasure,

Ellerman, David P., Property and Contract in Economics: The Case forEconomic Democracy, Blackwell, Oxford, 1992.

The Democratic Worker-Owned Firm: A New Model for Eastand West, Unwin Hyman, Boston, 1990. as “J. Philmore”, The Libertarian Case for Slavery, available at: http://cog.kent.edu/lib/Philmore1/Philmore1.htm

Elliot, Larry and Atkinson, Dan, The Age of Insecurity, Verso, London, 1998.

Fantasy Island: Waking Up to the Incredible Economic, Political and Social Illusions of the Blair Legacy, Constable, London, 2007. The Gods That Failed: Now the Financial Elite have Gambled Away our Futures, Vintage Books, London, 2009.

Engler, Allan, Apostles of Greed: Capitalism and the myth of the individual in the market, Pluto Press, London, 1995.

Evans Jr., Alfred B., Soviet Marxism-Leninism: The Decline of an Ideology, Praeger, London, 1993.

Faiwel, G. R., The Intellectual Capital of Michal Kalecki: A study ineconomic theory and policy, University of Tennessee Press, 1975.

Farber, Samuel, Before Stalinism: The Rise and Fall of Soviet Democracy, Polity Press, Oxford, 1990.

Fedotoff-White, D., The Growth of the Red Army, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1944.

Ferguson, C. E., The Neo-classical Theory of Production and Distribution, Cambridge University Press, London, 1969.

Ferro, Marc, October 1917: A social history of the Russian Revolution, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1980.

Figes, Orlando, A People’s Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1891–1924, Jonathan Cape, London, 1996.

Peasant Russia, Civil War: the Volga countryside in revolution 1917–1921, Phoenix Press, London, 2001.

Flamm, Kenneth, Creating the Computer: Government, Industry, and High Technology, The Brookings Institution, Washington D.C., 1988.

Forgacs, David (ed.), Rethinking Italian fascism: capitalism, populismand culture, Lawrence and Wishart, London, 1986.

Fraser, Ronald, Blood of Spain: the experience of civil war, 1936–1939, Allen Lane, London, 1979.

French, Marilyn, Beyond Power: On Women, Men, and Morals , Summit Books, 1985.

Frenkel-Brunswick, Else, The Authoritarian Personality,

Friedman, David, The Machinery of Freedom, Harper and Row, New York, 1973.

Friedman, Milton, Capitalism and Freedom, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2002.

Economic Freedom, Human Freedom, Political Freedom,available at: http://www.cbe.csueastbay.edu/~sbesc/frlect.html The Hong Kong Experiment, available at: http://www.hoover.org/publications/digest/3532186.html

Funnell, Warrick, Jupe, Robert and Andrew, Jane, In Government we Trust:Market Failure and the delusionsof privatisation, Pluto Press, London,2009.

Gaffney, Mason and Harrison, Mason, The Corruption of Economics, Shepheard-Walwyn (Publishers) Ltd., London, 1994.

Galbraith, James K., Created Unequal: The Crisis in American Pay, The Free Press, New York, 1999.

Galbraith, John Kenneth, The Essential Galbraith, Houghton Mifflin Company, New York, 2001.

The New Industrial State, 4th edition, Princeton University Press, Princeton and Oxford, 2007.

Gemie, Sharif, French Revolutions, 1815–1914, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 1999.

Getzler, Israel, Kronstadt 1917–1921: The Fate of a Soviet Democracy, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1983.

Martov: A Political Biography of a Russian Social Democrat, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 1967. “Soviets as Agents of Democratisation”, in Revolution in Russia: reassessments of 1917, Edith Rogovin Frankel, Jonathan Frankel, Baruch Knei-Paz (eds.), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge/New York, 1991. “Marxist Revolutionaries and the Dilemma of Power”, pp. 88–112, Revolution and Politics in Russia, Alexander and Janet Rabinowitch with Ladis K.D. Kristof (eds.)

Gilmour, Ian, Dancing with Dogma, Britain Under Thatcherism, Simon and Schuster, London, 1992.

Glennerster, Howard and Midgley, James (eds.), The Radical Right and the Welfare State:an international assessment, Harvester Wheatsheaf,1991.

Gluckstein, Donny, The Tragedy of Bukharin, Pluto Press, London, 1994

The Paris Commune: A Revolutionary Democracy, Bookmarks,London, 2006

Glyn, Andrew, Capitalism Unleashed: Finance Globalisation and Welfare,Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2006.

Glyn, Andrew and Miliband, David (eds.), Paying for Inequality: The Economic Costs of Social Injustice, IPPR/Rivers Oram Press, London, 1994.

Goodstein, Phil H., The Theory of the General Strike from the French Revolution to Poland, East European Monographs, Boulder, 1984.

Gould, Stephan Jay, Ever Since Darwin: Reflections in Natural History,Penguin Books, London, 1991.

Bully for Brontosaurus: Reflections in Natural History, Hutchinson Radius, London, 1991.

Gramsci, Antonio, Selections from Political Writings (1921–1926), Lawrence and Wishart, London, 1978.

Grant, Ted, The Unbroken Thread: The Development of Trotskyism over 40 Years, Fortress Publications, London, 1989.

Russia from revolution to counter-revolution available at https://www.marxist.com/russia-from-revolution-to-counter-revolution.htm

Gray, John, False Dawn: The Delusions of Global Capitalism, Granta Books, London, 1998.

Green, Duncan, Silent Revolution: The Rise of Market Economics in Latin America, Cassell, London, 1995.

Greider, William, One World, Ready or Not: The Manic Logic of Global Capitalism, Penguin Books, London, 1997.

Gross, Bertram, Friendly Fascism, South End Press, Boston, 1989.

Gunn, Christopher Eaton, Workers’ Self-Management in the United States, Cornell University Press, Ithaca and London, 1984.

Gunson, P., Thompson, A. and Chamberlain, G., The Dictionary of Contemporary Politics of South America, Routledge, 1989.

Hahnel, Robin and Albert, Michael, The Quiet Revolution in Welfare Economics, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1990.

The Political Economu of Participatory Economics, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1991. Looking Forward: Participatory Economics for the Twenty First Century, South End Press, Boston, 1991.

Hallas, Duncan, The Comintern, Bookmarks, London, 1985.

“Towards a revolutionary socialist party”, contained inTony Cliff, Duncan Hallas, Chris Harman and Leon Trotsky,Party and Class, Bookmarks, London, 1996.

Harding, Neil, Leninism, MacMillan Press, London, 1996.

Lenin’s political thought, vol. 1, Macmillan, London, 1977.

Harman, Chris, Bureaucracy and Revolution in Eastern Europe, Pluto Press, London, 1974.

“Party and Class”, contained in Tony Cliff, Duncan Hallas, Chris Harman and Leon Trotsky, Party and Class,Bookmarks, London, 1996, How the revolution was lost available at: http://www.marxists.de/statecap/harman/revlost.htm

Hastrup, Kirsten, Culture and History in Medieval Iceland, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1985.

Hatch, John B., “Labour Conflict in Moscow, 1921–1925” contained in Russia in the Era of NEP: explorations in Soviet society and culture, Fitzpatrick, Sheila, Rabinowitch, Alexander and Stites, Richard (eds.), Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1991.

Hawkins, Howard, “Community Control, Workers’ Control and the Co-operative Commonwealth”, Society and Nature, no. 3, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 55–85.

Haworth, Alan, Anti-Libertarianism: Markets, Philosophy and Myth, Routledge, London, 1994.

Hayek, F. A. von, The Essence of Hayek, Chiaki Nishiyama and Kurt Leube (Eds.), Hoover Institution Press, Stanford, 1984

Individualism and Economic Order, Henry Regnery Company, Chicago, 1948 “1980s Unemployment and the Unions” contained in Coates, David and Hillard, John (Eds.), The Economic Decline of Modern Britain: The Debate between Left and Right, Wheatsheaf Books Ltd., 1986. New Studies in Philosophy, Politics, Economics and the History of Ideas, Routledge & Kegan Paul. London/Henley, 1978. Law, Legislation and Liberty, Routledge and Kegan Paul, London, 1982.

Hayek, F. A. von (ed.), Collectivist Economic Planning, Routledge and Kegan Paul, London, 1935.

Hayward, Jack, After the French Revolution: Six critics of Democracy and Nationalism, Harvester Wheatsheaf, Hemel Hempstead, 1991.

Heider, Ulrike, Anarchism: left, right, and green, City Lights Books, San Francisco, 1994.

Hein, Eckhard and Schulten, Thorsten, Unemployment, Wages and Collective Bargaining in the European Union, WSI_Discussion Paper No. 128, Witschafts- und Sozialwissenschaftliches Institut, Dusseldorf, 2004.

Henwood, Doug, Wall Street: How it works and for whom, Verso, London, 1998.

“Booming, Borrowing, and Consuming: The US Economy in 1999”, Monthly Review, vol. 51, no. 3, July-August 1999, pp.120–33. After the New Economy, The New Press, New York, 2003. Wall Street: Class Racket, available at http://www.panix.com/~dhenwood/WS_Brecht.html

Herbert, Auberon, “Essay X: The Principles Of Voluntaryism And Free Life”, The Right And Wrong Of Compulsion By The State, And Other Essays, available at: http://oll.libertyfund.org/Texts/LFBooks/Herbert0120/CompulsionByState/HTMLs/0146_Pt11_Principles.html

“Essay III: A Politician In Sight Of Haven”, The Right And Wrong Of Compulsion By The State, And Other Essays, available at: http://oll.libertyfund.org/Texts/LFBooks/Herbert0120/CompulsionByState/HTMLs/0146_Pt04_Politician.html

Herman, Edward S., Beyond Hypocrisy, South End Press, Boston, 1992.

Corporate Control, Corporate Power, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1981. “Immiserating Growth: The First World”, Z Magazine, January, 1994. “The Economics of the Rich”, Z Magazine, July, 1997

Herman, Edward S. and Chomsky, Noam, Manufacturing Consent: the politicaleconomy of the mass media, Pantheon Books,New York, 1988.

Heywood, Paul, Marxism and the Failure of Organised Socialism in Spain 1879–1936, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1990.

Hicks, J. R., Value and capital: an inquiry into some fundamental principles of economic theory, 2nd edition, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1975.

Hills, John, Inequality and the State, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2004.

Hobsbawm, Eric, Primitive Rebels: Studies in Archaic Forms of Social Movements in the 19th and 20th Centuries, 2nd Edition, W. W. Norton and Co., New Yprk, 1965.

Revolutionaries, rev. ed., Abacus, London, 2007.

Hodgskin, Thomas, Labour Defended against the Claims of Capital, available at: http://socserv2.socsci.mcmaster.ca/~econ/ugcm/3ll3/hodgskin/labdef.txt

Hollis, Martin and Edward Nell, Rational Economic Man: A Philosophical Critique of Neo-classic Economics, Cambridge University Press, London, 1975.

Hodgson, Geoffrey Martin, Economics and Utopia: why the learning economy is not the end of history, Routledge, London/New York, 1999.

Hoppe, Hans-Hermann, Democracy: The God That Failed: The Economics andPolitics of Monarchy, Democracy, and Natural Order,Transaction, 2001.

Anarcho-Capitalism: An Annotated Bibliography, available at: http://www.lewrockwell.com/hoppe/hoppe5.html

Holt, Richard P. F. and Pressman, Steven (eds.), A New Guide to Post KeynesianEconomics, Routledge, London, 2001.

Howell, David R. (ed.), Fighting Unemployment: The Limits of Free MarketOrthodoxy, Oxford University Press, New York, 2005.

Hutton, Will, The State We’re In, Vintage, London, 1996.

The World We’re In, Little, Brown, London, 2002.

Hutton, Will and Giddens, Anthony (eds.), On The Edge: living with global capitalism,Jonathan Cape, London, 2000.

ISG, Discussion Document of Ex-SWP Comrades, available at: http://www.angelfire.com/journal/iso/isg.html

Lenin vs. the SWP: Bureaucratic Centralism Or Democratic Centralism?, available at: http://www.angelfire.com/journal/iso/swp.html

Jackson, Gabriel, The Spanish Republic and the Civil War, 1931–1939, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1965.

Jackson, J. Hampden, Marx, Proudhon and European Socialism, English Universities Press, London, 1957.

Johnson, Martin Phillip, The Paradise of Association: Political Culture and Popular Organisation in the Paris Commune of 1871, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 1996

Kaldor, Nicholas, Further Essays on Applied Economics, Duckworth, London, 1978.

The Essential Kaldor, F. Targetti and A.P. Thirlwall (eds.), Holmes & Meier, New York, 1989. The Economic Consequences of Mrs Thatcher, Gerald Duckworth and Co. Ltd, London, 1983.

Kaplan, Frederick I., Bolshevik Ideology and the Ethics of Soviet Labour,1917–1920: The Formative Years, Peter Owen, London, 1969.

Kaplan, Temma, Anarchists of Andalusia: 1868–1903, Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J., 1965.

Katouzian, Homa, Ideology and Method in Economics, MacMillian Press Ltd., London, 1980.

Kautsky, Karl, The road to power: political reflections on growing intothe revolution, Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, 1996.

Keen, Steve, Debunking Economics: The Naked Emperor of the social sciences, Pluto Press Australia, Annandale, 2001.

Keynes, John Maynard, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, MacMillan Press, London, 1974.

Kerhohan, Andrew, “Capitalism and Self-Ownership”, from Capitalism, pp. 60–76, Paul, Ellen Frankel, Fred D. Miller Jr., Jeffrey Paul and John Ahrens (eds.), Basil Blackwood, Oxford, 1989.

Kindleberger, Charles P., Manias, Panics, and Crashes: a history of financialcrises, 2nd Edition, Macmillan, London, 1989.

King, J.E., A history of post Keynesian economics since 1936, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, 2002

Kirzner, Israel M., “Entrepreneurship, Entitlement, and Economic Justice”, pp. 385–413, in Reading Nozick: Essays on Anarchy, State and Utopia, Jeffrey Paul (ed.), Basil Blackwell, Oxford, 1982.

Perception, Opportunity, and Profit, University of ChicagoPress, Chicago, 1979.

Klein, Naomi, No Logo, Flamingo, London, 2001.

Fences and Windows: Dispatches from the front lines of theGlobalisation Debate, Flamingo, London, 2002.

Koenker, Diane P., “Labour Relations in Socialist Russia: Class Values and Production Values in the Printers’ Union, 1917–1921,” pp. 159–193, Siegelbaum, Lewis H., and Suny, Ronald Grigor (eds.), Making Workers Soviet: power, class, and identity, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 1994.

Koenker, Diane P., Rosenberg, William G. and Suny, Ronald Grigor (eds.), Party, State, and Society in the Russian Civil War, Indiana University Press, Indiana, 1989.

Kohn, Alfie, No Contest: The Case Against Competition, Houghton Mufflin Co.,New York, 1992.

Punished by Rewards: The Trouble with Gold Stars, Incentive Plans, A’s, Praise and Other Bribes, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1993.

Kollontai, Alexandra, The Workers Opposition, Solidarity, London, date unknown.

Selected Writings of Alexandra Kollontai, Allison and Busby, London, 1977.

Kowalski, Ronald I., The Bolshevik Party in Conflict: the left communist opposition of 1918, Macmillan, Basingstoke, 1990.

Krause, Peter, The Battle for Homestead, 1880–1892: politics, culture, and steel, University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh/London, 1992

Krugman, Paul, Peddling Prosperity: Economic Sense and Nonsense in the Age of Diminished Expectations, NW Norton & Co., New York/London, 1994.

The Conscience of a Liberal, W.W. Norton & Co., New York/London, 2007.

Krugman, Paul and Wells, Robin, Economics, W. H. Freeman, New York, 2006.

Kuhn, Thomas S., The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 3rd ed., University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1996.

Kuznets, Simon, Economic Growth and Structure: Selected Essays, Heineman Educational Books, London, 1966.

Capital in the American Economy, Princeton University Press, New York, 1961.

Lange, Oskar and Taylor, Fred M., On the Economic Theory of Socialism, Benjamin Lippincott (ed.), University of Minnesota Press, New York, 1938.

Laqueur, Walter (ed.), Fascism: a Reader’s Guide, Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1979.

Lazonick, William, Business Organisation and the Myth of the Market Economy, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1991.

Competitive Advantage on the Shop Floor, Havard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1990. Organisation and Technology in Capitalist Development, Edward Elgar, Brookfield, Vt, 1992.

Lea, John and Pilling, Geoff (eds.), The condition of Britain: Essays on Frederick Engels, Pluto Press, London, 1996.

Lear, John, Workers, Neighbors, and Citizens: The Revolution in Mexico City, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 2001.

Lee, Frederic S., Post Keynesian Price Theory, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1998

Leggett, George, The Cheka: Lenin’s Political Police, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1981.

Lenin, V. I., Essential Works of Lenin, Henry M. Christman (ed.), Bantam Books, New York, 1966.

The Lenin Anthology, Robert C. Tucker (ed.), W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 1975. Will the Bolsheviks Maintain Power?, Sutton Publishing Ltd,Stroud, 1997. Left-wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder, Lawrence & Wishart,London, 1947. The Immediate Tasks of the Soviet Government, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1970. Six Thesis on the Immediate Tasks of the Soviet Government,contained in The Immediate Tasks of the Soviet Government, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1970, pp. 42–45. The Threatening Catastrophe and How to Avoid It, Martin Lawrence Ltd., undated. Selected Works: In Three Volumes, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1975.

Lenin, V. I., and Trotsky, Leon, Kronstadt, Monad Press, New York, 1986.

Levin, Michael, Marx, Engels and Liberal Democracy, MacMillan Press, London, 1989.

Lichtenstein, Nelson and Howell, John Harris (eds.), Industrial Democracy in America: The Ambiguous Promise, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1992

Lichtheim, George, The origins of socialism, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 1969

A short history of socialism, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 1970

Lincoln, W. Bruce, Red Victory: A History of the Russian Civil War, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1989.

List, Friedrich, The Natural System of Political Economy, Frank Cass, London, 1983.

Lovell, David W., From Marx to Lenin: An evaluation of Marx’s responsibility for Soviet authoritarianism, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1984.

Luxemburg, Rosa, Rosa Luxemburg Speaks, Mary-Alice Waters (ed.), Pathfinder Press, New York, 1970.

MacPherson, C.B., The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism: Hobbes to Locke, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1964.

Malle, Silvana, The Economic Organisation of War Communism, 1918–1921, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1985.

Mandel, David, The Petrograd Workers and the Soviet Seizure of Power: from the July days 1917 to July 1918, MacMillan, London, 1984.

Marglin, Steven, “What do Bosses Do?”, Review of Radical Political Economy, Vol. 6, No.2, New York, 1974.

Marshall, Alfred, Principles of Economics: An Introductory Volume, 9th Edition (in 2 volumes), MacMillian, London, 1961.

Martin, Benjamin, The Agony of Modernisation: Labour and Industrialisation in Spain, ICR Press, Cornell University, 1990.

Martov, J., The State and Socialist Revolution, Carl Slienger, London, 1977.

Marx, Karl, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, vol. 1, Penguin Books, London, 1976.

Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, vol. 3, Penguin Books, London, 1981. Theories of Surplus Value, vol. 3, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1971. A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1970.

Marx, Karl and Engels, Frederick, Selected Works, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1975.

The Marx-Engels Reader, Second Edition,Robert C. Tucker (ed.), W.W. Norton & Co, London & New York, 1978. The socialist revolution, F. Teplov and V. Davydov (eds.)Progess, Moscow, 1978. Basic Writings on Politics and Philosophy,Lewis S. Feuer (ed.), Fontana/Collins, Aylesbury, 1984. “Manifesto of the Communist Party”, Selected Works, pp. 31–63. Fictitious Splits In The International,available at: http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1864iwma/1872-e.htm

Marx, Karl, Engels, Federick and Lenin, V.I., Anarchism and Anarcho-Syndicalism, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1974.

Matthews, R.C.O. (ed.), Economy and Democracy, MacMillan Press Ltd., London, 1985.

McAuley, Mary, Bread and Justice: State and Society in Petrograd 1917–1922, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1991.

McElroy, Wendy, Anarchism: Two Kinds, available at:http://www.wendymcelroy.com/mises/twoanarchism.html

McLay, Farguhar (ed.), Workers City: The Real Glasgow Stands Up, Clydeside Press, Glasgow, 1988.

McNally, David, Against the Market: Political Economy, Market Socialism and the Marxist Critique, Verso, London, 1993.

Another World Is Possible: Globalization & Anti-Capitalism, Revised Expanded Edition, Merlin, 2006.

Mehring, Franz, Karl Marx: The Story of his life, John Lane, London, 1936.

Miliband, Ralph, Divided societies: class struggle in contemporary capitalism, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1989.

Mill, John Stuart, Principles of Political Economy, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1994.

On Liberty and Other Essays, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1991.

Miller, David, Social Justice, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1976.

Market, State, and community: theoretical foundations of marketsocialism, Clarendon, Oxford, 1989.

Miller, William Ian, Bloodtaking and Peacemaking: Feud, Law and Society in Saga Iceland, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1990.

Mills, C. Wright, The Power Elite, Oxford University Press, London, 1956.

Milne, S., The Enemy Within, Verso, London, 1994.

Minsky, Hyman, Inflation, Recession and Economic Policy, Wheatsheaf Books, Sussex, 1982.

“The Financial Instability Hypothesis” in Post-Keynesian Economic Theory, pp. 24–55, Arestis, Philip and Skouras, Thanos (eds.), Wheatsheaf Books, Sussex, 1985.

Mises, Ludwig von, Liberalism: A Socio-Economic Exposition,Sheed Andres and McMeek Inc., Kansas City, 1978.

Human Action: A Treatise on Economics, William Hodge and Company Ltd., London, 1949. Socialism: an economic and sociological analysis, Cape, London, 1951.

Montagu, Ashley, The Nature of Human Aggression, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1978.

Montgomery, David, Beyond Equality: Labour and the Radical Republicans, 1862–1872, Vintage Books, New York, 1967.

The Fall of the House of Labour: The Workplace, the state, and American labour activism, 1865–1925, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1987.

Moore, Michael, Downsize This! Random Threats from an Unarmed America, Boxtree, London, 1997.

Morrow, Felix, Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Spain, Pathfinder Press, New York, 1974.

Mumford, Lewis, The Future of Technics and Civilisation, Freedom Press, London, 1986.

Negri, Antonio, Marx Beyond Marx, Autonomedia, Brooklyn, 1991.

Neill, A.S, Summerhill: a Radical Approach to Child Rearing, Penguin, 1985.

Newman, Stephen L., Liberalism at wit’s end: the libertarian revolt against the modern state, Cornell University Press, 1984.

Noble, David, America by Design: Science, technology, and the rise of corporate capitalism, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1979.

Progress without People: In defense of Luddism, Charles H. Kerr Publishing Ltd., Chicago, 1993. Forces of Production: A Social History of Industrial Automation, Oxford University Press, New York, 1984.

Nove, Alec, An economic history of the USSR: 1917–1991, 3rd ed., Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1992.

Socialism, Economics and Development, Allen & Unwin, London, 1986.

Nozick, Robert, Anarchy, State and Utopia, B. Blackwell, Oxford, 1974.

Oestreicher, Richard Jules, Solidarity and fragmentation: working people and class consciousness in Detroit, 1875–1900, University of Illinois Press, Urbana, 1986.

Ollman, Bertell, Social and Sexual Revolution: Essays on Marx and Reich, Black Rose Books, Montreal, 1978.

Ollman, Bertell (ed.), Market Socialism: The Debate Among Socialists, Routledge, London, 1998.

O’Neill, John, Markets, Deliberation and Environment, Routledge, Oxon, 2007.

The market: ethics, knowledge, and politics, Routledge, London, 1998 Ecology, policy, and politics: human well-being and the natural world, Routledge, London/New York, 1993.

Oppenheimer, Franz, The State, Free Life Editions, New York, 1975.

Ormerod, Paul, The Death of Economics, Faber and Faber Ltd., London, 1994.

Orwell, George, Homage to Catalonia, Penguin, London, 1989.

The Road to Wigan Pier, Penguin, London, 1954. Nineteen Eighty-Four, Penguin, Middlesex, 1982. Orwell in Spain, Penguin Books, London, 2001. Inside the Whale and Other Essays, Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, 1986.

Pagano, U. and Rowthorn, R. E. (eds.), Democracy and Efficiency in Economic Enterprises, Routledge, London, 1996.

Palley, Thomas I., Plenty of Nothing: The Downsizing of the American Dreamand the case for Structural Keynesian, Princeton UniversityPress, Princeton, 1998.

Paul, Ellen Frankel. Miller, Jr., Fred D. Paul, Jeffrey and Greenberg, Dan (eds.), Socialism, Basil Blackwell, Oxford, 1989.

Perrin, David A., The Socialist Party of Great Britain: Politics, Economics and Britain’s Oldest Socialist Party, Bridge Books, Wrexham, 2000.

Petras, James and Leiva, Fernando Ignacio, Democracy and Poverty in Chile: The Limits to Electoral Politics, Westview Press, Boulder, 1994.

Pipes, R., Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime, 1919–1924, Fontana Press, London, 1995.

Pirani, Simon, The Russian revolution in retreat, 1920–24: Soviet workers and the new Communist elite, Routledge, New York, 2008

Phillips, Kevin, The Politics of Rich and Poor: Wealth and the American Electorate in the Reagan Aftermath, Random House, New York, 1990.

Polanyi, Karl, The Great Transformation: the political and economic origins of our time, Beacon Press, Boston, 1957.

Popper, Karl, Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge, Basic, New York, 1965.

Preston, Paul, The coming of the Spanish Civil War: reform, reaction, and revolution in the Second Republic, 2nd ed., Routledge, London/New York, 1994.

Preston, Paul (ed.), Revolution and War in Spain 1931–1939, Methuen, London, 1984.

Prychitko, David L., Markets, Planning and Democracy: essays after the collapse of communism, Edward Elgar, Northampton, 2002.

Rabinowitch, Alexander, Prelude to Revolution: The Petrograd Bolsheviks and the July 1917 Uprising, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1991.

The Bolsheviks Come to Power: The Revolution of 1917 in Petrograd, W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 1976. The Bolsheviks in Power: The first year of Soviet rule in Petrograd, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2007. “Early Disenchantment with Bolshevik Rule: New Data form the Archives of the Extraordinary Assembly of Delegates from Petrograd Factories”, Politics and Society under the Bolsheviks, Dermott, Kevin and Morison, John (eds.), Macmillan, Basingstoke, 1999.

Rabinowitch, Alexander and Janet with Kristof, Ladis K.D. (eds.), Revolution and politics in Russia: essays in memory of B.I. Nicolaevsky, Indiana University Press for the International Affairs Center, Bloomington/London, 1973.

Radcliff, Pamela Beth, From mobilization to civil war: the politics of polarizationin the Spanish city of Gijon, 1900–1937, Cambridge University Press, New York, 1996.

Radin, Paul, The World of Primitive Man, Grove Press, New York, 1960.

Radek, Karl, The Kronstadt Uprising available at, https://www.marxists.org/archive/radek/1921/04/kronstadt.htm

Raleigh, Donald J., Experiencing Russia’s Civil War: Politics, Society,and Revolutionary Culture in Saratov, 1917–1921,Princeton University Press, Woodstock, 2002.

Rand, Ayn, Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal, New American Library, New York, 1966.

The Ayn Rand Lexicon: Objectivism from A to Z, Harry Binswanger (ed.), Meridian, New York, 1986. The Virtue of Selfishness, New American Library, New York, 1964.

Ransome, Arthur, The Crisis in Russia 1920, Redwords, London, 1992.

Rayack, Elton, Not So Free To Choose: The Political Economy of MiltonFriedman and Ronald Reagan, Praeger, New York, 1987.

Read, Christopher, From Tsar to Soviets: The Russian people andtheir revolution, 1917–21, UCL Press, London, 1996.

Reed, John, Ten Days that shook the World, Penguin Books, 1982.

Shaking the World: John Reed’s revolutionary journalism,Bookmarks, London, 1998.

Reekie, W. Duncan, Markets, Entrepreneurs and Liberty: An Austrian Viewof Capitalism, Wheatsheaf Books Ltd., Sussex, 1984.

Reich, Wilhelm, The Mass Psychology of Fascism, Condor Book, Souvenir Press (E&A) Ltd., USA, 1991.

Reitzer, George, The McDonaldization of Society: An Investigation into the changing character of contemporary social life, Pine Forge Press, Thousand Oaks, 1993.

Remington, Thomas F., Building Socialism in Bolshevik Russia: Ideology and Industrial Organisation 1917–1921, University of Pittsburgh Press, London, 1984.

Richardson, Al (ed.), In defence of the Russian revolution: a selection of Bolshevik writings, 1917–1923, Porcupine Press, London, 1995.

Ricardo, David, The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, J.M. Dent & Sons/Charles E. Tuttle Co., London/Vermont, 1992.

Ridgeway, James, Blood in the Face: The Ku Klux Klan, Aryan Nations, Nazi Skinheads, and the Rise of a New White Culture, Thunder’s Mouth Press, 1990.

Roberts, David D., The Syndicalist Tradition and Italian Fascism,University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 1979.

Robertson, Dennis, “Wage-grumbles”, Economic Fragments, pp. 42–57, in W. Fellner and B. Haley (eds.), Readings in the theoryof income distribution, The Blakiston, Philadephia, 1951.