#Giant South American River Turtle

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

World Turtle Day

Get in touch with the American Tortoise Rescue to see how you can do your part to protect and preserve the wonderful turtles and tortoises in the world.

We hear about them in parables of being slow and plodding, steady and methodical, and being occasionally obsessed with Ninjitsu, news reporters, and pizza. We are, of course, talking about Turtles!

Turtles are a type of reptile that exists in many environments throughout the world and have found their way into literature, poetry, and parable throughout the world’s history.

World Turtle Day celebrates these noble reptiles and their place in the world and encourages people to take action to help protect both the common pet turtle and the ever endangered.

How to Celebrate (or “Shellebrate”) World Turtle Day

Get Connected

Contact American Tortoise Rescue and find out what you can do in your area to help promote the protection of turtles. If there are no activities in your area, work with them to find out what you can do to coordinate with local aquariums, pet stores, and nature groups to focus on the species of this reptile that live in your area.

Support the Turtles

Wherever you are, you can donate online to turtle causes, or even arrange your own charity and awareness campaigns to help support your favorite species.

You might want to spare your time rather than your money by getting involved in these events, or simply volunteer at your local pet shop to help out their turtles and tortoises. You don’t have to be near a local conservation area to do your bit to help our reptilian friends.

Visit a Turtle Habitat

If you do want to visit a local habitat, why not book a trip and go safely through your local charity to see how they support and help the local wildlife? Across the globe, there are hundreds of places you can visit to help support turtles and tortoises with a licensed charity.

Enjoy Your Pet Turtle

If you have your own tortoise or turtle, why not show it some appreciation on its very own special day? Why not buy your turtle a new rock for its terrarium, or build its very own private basking beach if they don’t have one yet.

Why not give their tank an early spring deep clean to make sure they’re lounging in the best possible environment for them.

Studies show that tortoises can respond to the sound of their owner’s voice (might be because you feed them, or they love you, it’s hard to tell). Why not treat them to some of their favorite broccoli, or even give them a good soak when needed to keep them living their best life.

Keep the Beaches Clean

If you’re not near a turtle or tortoise hub, keeping your nearby beaches clean is equally important for local wildlife and their ecosystem. Keeping your local sandy summer spot free from plastic bags or water bottles will keep the surrounding sea and land life happy. Don’t live near a beach?

Plastic can endanger your local wildlife even in an urban environment, and animals from foxes to fish can get caught up in plastic. Why not do a local recycling drive or clear out in your local park as a big thank you to our two, four, and no-legged friends.

Turtles are amazing creatures, with certain varieties making great pets and others helping to preserve the ecosystem in the waters they live in.

Of course, if you live where snapping turtles haunt the waters, it’s probably a good idea that people know how to avoid them, where to find them, and how not to lose a toe! Happy World Turtle Day!

History of World Turtle Day

Well, the first thing to know is that Turtles and Tortoises are not the same thing, though this day is dedicated to celebrating and protecting both.

Founded in 1990 by American Tortoise Rescue, World Turtle day recognizes that some species of our hard (and soft!) shelled friends are suffering and almost on the edge of extinction due to environmental hazards, issues with hunting and harvesting of their eggs.

American Tortoise Rescue was created by Susan Tellem and Marshall Thompson, a married pair of animal activists who had a particular passion for tortoises.

We all have to have something that drives us in this life, and for these two it was bonding over animal right’s activist work. Don’t think these two are just closet hippies with an overwhelming adoration for all things shelled and scaly.

Susan is deeply involved with television arts & sciences and the public relations society of America while being a partner in Tellem Grody Public Relations Incorporated.

They organize charity collections and works around the world to help protect these amazing critters, and created World Turtle Day to get everyone involved and spread awareness of the shrinking habitat and declining numbers of these sensitive creatures.

Learn More About Turtles

So what is the difference between turtles and tortoises? Although they are both reptiles, the main difference between the two is that turtles live in the water at least some of the time, while tortoises live on the land.

Because they live in the water, turtles have streamlined and mostly flat shells, while tortoises often have larger and more domed ones.

Our tortoise friends can also live longer than their reptilian cousins. Tortoises can live over 300 years, although their average lifespan can go up to around 150 years. Turtles live up until the age of 40, although one record-breaking turtle almost lived to the age of 90!

Learning the differences between our reptile friends is just one of the educational activities that World Turtle Day helps promote.

The Turtle and Tortoise Preservation Group (The TTPG) is open to all turtle and tortoise lovers and creates educational material to help teach kids and adults about these reptilian creatures.

The TTPG helps those who are breeding turtles to keep them safe from extinction, by providing advice to turtle and tortoise keepers. From anyone who has a faithful four-legged tortoise friend to expert breeders, the TTPG is there to help.

World Turtle Day FAQs

How did the idea of a ‘World Turtle’ carrying the Earth influence cultures?

Many cultures feature myths of a giant turtle supporting the world. In Hindu mythology, the World Turtle, known as Kurma, supports the Earth.

This symbolizes stability and endurance. Such myths highlight the turtle’s role in human imagination.

What unique traditions exist worldwide to honor turtles?

In some African cultures, turtles symbolize wisdom. Stories often depict them as clever tricksters.

In Polynesia, warriors tattoo turtle symbols for protection. These traditions reflect the turtle’s cultural significance.

Is it true that turtles can breathe through their rear ends?

Yes, some turtles can absorb oxygen through their cloaca, an opening used for excretion and reproduction. This adaptation allows them to stay underwater longer, especially during hibernation.

How do temperature changes affect turtle populations?

For many turtle species, the incubation temperature of eggs determines the sex of hatchlings.

Warmer temperatures tend to produce females, while cooler ones produce males. Climate change could thus skew sex ratios, impacting future populations.

Why do some cultures associate turtles with creation myths?

In certain Indigenous South American myths, turtles play a role in creation stories.

For example, some tales describe humans emerging from eggs laid by a World Turtle. These stories emphasize the turtle’s perceived role in the origin of life.

What are some common misconceptions about turtles?

A common myth is that turtles can leave their shells. In reality, a turtle’s shell is part of its skeleton, fused to its spine and ribs. They cannot exit it without fatal consequences.

How do turtles contribute to their ecosystems?

Turtles help maintain healthy ecosystems by controlling jellyfish populations and aiding in seagrass bed health. Their nesting activities also contribute nutrients to beach ecosystems, supporting plant life.

What role did turtles play in ancient Greek symbolism?

In ancient Greece, turtles symbolized fertility and were associated with the goddess Aphrodite. Artifacts often depict her with a turtle, emphasizing its connection to love and fertility.

How do turtles navigate during long migrations?

Sea turtles possess a remarkable ability to navigate using Earth’s magnetic fields. They detect magnetic signatures unique to different coastal areas, guiding them back to their natal beaches to nest.

What are some unusual threats that turtles face today?

Beyond habitat loss and pollution, turtles face threats from the illegal pet trade and being caught as bycatch in fishing gear. These factors contribute significantly to the decline of turtle populations worldwide.

Source

#Red-eared Slider#World Turtle Day#WorldTurtleDay#Shellebrate#23 May#Bronx Zoo#Zoo Zürich#Zurich#Schweiz#Switzerland#flora#fauna#water#original photography#Aldabra giant tortoise#Radiated tortoise#USA#Giant South American River Turtle#Galápagos tortoise#everything is Due South#Spider tortoise#reptile#New York City#animal#reflection#travel#vacation#tourist attraction#I really love the first pic#wildlife

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Newly discovered fossil of giant turtle is named after Stephen King novel character

Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum

An international research team led by Dr. Gabriel S. Ferreira from the Senckenberg Center for Human Evolution and Paleoenvironment at the University of Tübingen has described a new species of giant turtle from the late Pleistocene. Peltocephalus maturin is between 40,000 and 9,000 years old and comes from the Brazilian Amazon. With a shell length of about 180 centimeters, the species is one of the largest known freshwater turtles in the world. The armored reptile was named after the giant turtle "Maturin," a fictional character created by best-selling author Stephen King. With a maximum shell length of 140 centimeters, the Asian narrow-headed softshell turtle (Chitra chitra) together with the approximately 110-centimeter-long South American river turtle (Podocnemis expansa) is one of the largest freshwater turtles alive today...

Read more: https://phys.org/news/2024-03-newly-fossil-giant-turtle-stephen.html

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Caiman House in Yupukari Village, North Rupununi Guyana.

I think I may have found paradise on Earth.

I visited during the dry season, but in the wet, everything the light touches is flooded by one of two neighbouring river systems.

The Mapuke people were so welcoming and full of knowledge about their breathtaking environment. Caiman House EcoLodge was beautiful and super comfortable and activities were balanced by plenty of rest during the hottest part of the day and plentiful fresh food, tailored to guests’ preferences.

We went on a caiman capture trip to support research into black caiman populations, visited the village’s turtle conservation project, saw the blue backed manakin on a birdwatching walk, saw giant anteaters and giant otters and the Agame heron, and hundreds of other creatures I’ll never remember the names of.

If you’re looking for somewhere to go as a South American alternative to the African Safari, I cannot recommend the Rupununi region enough. And I’ll put in a special word for Caiman House - it’s run by and for the community and delivering training and opportunities to a community of around a thousand people. The guides are working to develop more remote and immersive opportunities and the money from the lodge is supporting programs to develop local artists and crafters into independent sellers, and supporting women to establish commercially successful cassava processing in nearby villages. The staff all rotate through from other roles in the village to share skills around and I did not meet a single person who wasn’t unbelievable generous, knowledgeable, and absolutely thrilled to share their home with tourists.

#brynn travels to latin america#first time backpacker#guyana#rupununi#region 9#Yupukari#black caiman#cassava

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

#birdlandjazz#centralparknewyork#eastvillagejournal#frauncestavern#nyuniversity#Openingnight.Reviews#westvillagelife#wspconservancy

0 notes

Text

Mythic Creatures by Culture & Region

Part 2: Settler (Colonial) & Diasporic Tales of Australia & the Americas

Overview here.

• Australian Settler Folktales Drop Bear; Easter Bilby; Oozlum Bird (oozlum bird also in Britain)

Canadian Settler Folktales

Cadborosaurus B.C.; Cressie; Igopogo Barrie; Manipogo; Memphre; Mussie; Red Lady; Thetis Lake Monster; Turtle Lake Monster

USAmerican Settler folktales including African diaspora

Agropelter, Maine & Ohio; Alfred Bulltop Stormalong Massachussets; Altamaha-ha in Georgia, U.S.A, see Muskogee; Anansi is Akan (which includes the Agona, Akuapem, Akwamu, Akyem, Anyi, Ashanti, Baoulé, Bono, Chakosi, Fante, Kwahu, Sefwi, Wassa, Ahanta, and Nzema) also found in African American lore; Red Ghost (Arizona camel with skeleton on its back); Augerino western USA, including Colorado; Axehandle hound Minnesota and Wisconsin; Ball-tailed cat; Beaman Monster; Bear Lake Monster; Beast of Bladenboro; Beast of Busco; Bell Witch; Belled buzzard American South; Bessie northeast Ohio and Michigan; Bigfoot; Black Dog; Blafard; Bloody Bones; Bloody Mary; Boo hag; Br'er Rabbit; Brown Mountain Lights; Cactus cat American Southwest; Calafia Amazon Queen (Caliph) that California is named after; Champ; Chessie; Dark Watchers; Demon Cat Washington D.C.; Dewey Lake Monster; Dover Demon; Dungavenhooter Maine, Michigan; Emperor Norton; Enfield Monster (NOT Enfield); Flathead Lake Monster; Flatwoods Monster; Flying Africans; Fouke Monster Arkansas; Fur-bearing trout; Gallinipper; Gillygaloo; Glawackus; Gloucester sea serpent; Golden Bear; Goofus Bird; Gumberoo; Hidebehind; Hillbilly Beast of Kentucky; Hodag; Honey Island Swamp Monster; Hoop Snake; Hudson River Monster; Hugag; Jackalope; Jersey Devil; Joint Snake; Jonathan Moulton; Lady Featherflight; Lagahoo; Lake Worth Monster; Lava bear Oregon, appear to have been real animals but not a unique species; Letiche (Cajun folktale, from descendants of the Acadian expulsion) Lizard Man of Scape Ore Swamp; Loveland Frog; Ludwig the Bloodsucker; Mãe-do-Ouro; Mami Wata also African; Maryland Goatman; Melon-heads; Michigan Dogman; Milton lizard; Mogollon Monster; Momo the Monster; Mothman; Nain Rouge Detroit, Michigan; New Jersey folktales; North Shore Monster; Onza; Ozark Howler; Pope Lick Monster; Proctor Valley Monster; Railroad Bill; Red Ghost; Red Lady; Reptilian; Resurrection Mary; Sharlie; Sidehill Gouger; Signifying monkey; Skunk Ape; Snallygaster; Snipe Hunt; Snow Snake; Splintercat; Squonk; Tahoe Tessie; Tailypo; Teakettler; The Witch of Saratoga; Tuttle Bottoms Monster; Two-Toed Tom; Walgren Lake Monster; Wampus Cat; White River Monster; Wild Man of the Navidad

Latin American Folklore

Aido Hwedo, Haiti & also in Benin; Alebrije (born from a dream, Mexican paper mache folk art); Baccoo could be based off Abiku of Yoruba lore; Bestial Beast bestial centaur; Boiuna; Boto and Boto_and_Dolphin_Spirits; Bruja; Bumba Meu Boi; Burrokeet; Cadejo; Camahueto; Capelobo; Carbuncle; Carranco; Chasca El Salvador; Chickcharney; Ciguapa Dominica; Cipitio; Damballa; Day of the Dead; Death; Douen; Duende; Duppy; El Sombrerón Guatemala; Folktales of Mexico; Headless Mule; Hombre Gato; Honduran Creatures; Huay Chivo; Ibo loa (also Igbo in West Africa); Jumbee; Kasogonagá (Toba in Argentina); La Bolefuego; La Diablesse; La Llorona; La mula herrada; La Sayona; Lang Bobi Suzi; Madre de aguas; Mama D'Leau; Minhocão; Mono Grande; Monster of Lake Fagua; Monster of Lake Tota; Muan; Muelona; Nahuelito; Obia also a word for a West African mythological creature (see article); Papa Bois; Patagon aka Patagonian Giant; Patasola; Phantome (Trinidad, Tobago, Guyana); Pishtaco; Princess Eréndira; Quimbanda; Romãozinho; Saci; Sayona ; Sihuanaba; Sisimoto; Soucouyant; Succarath; Tapire-iauara; Tata Duende; The Cu Bird; The Silbón; Tulevieja; Tunda; Zombie Bolivia; Abchanchu; Acalica; El Tío Colombia; Colombian Creatures; El Hombre Caimán; Tunda

Please note that some of these beings (those from Latin America or from diasporic African religions like Santeria, Vodun and Candomble) are sacred and be responsible about their use in art (writing etc.).

Notify me of any mistakes or to add disclaimers when something is considered sacred and off-limits.

#mythic creature list#mythic creatures#mythical creatures#legendary creature list#creature list#legendary creature#monster list#list of monsters#legendary being#legendary beings

1 note

·

View note

Video

vimeo

What are we seeing here?

Though they reach up to 200 pounds at maturity, the Giant South American River Turtle starts small—and therefore vulnerable to predators. To improve their chances for survival, hatchlings in some areas use mass birth to increase their survival. That’s what happened in December in a protected nesting area along Brazil’s Purus River, a tributary of the Amazon. 71,000 hatchlings emerged from their nests on the sandy beach in just one day, followed by another 21,000 a few days later. And WCS Brazil conservationists were lucky enough to catch it on video. It’s truly awe-inspiring to see tens of thousands of newborn turtles joining together to make the journey to the water’s edge.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Turtle Tsunami; 92000 Giant South American River Turtles Hatched In Brazil River | ब्राजील में नदी किनारे आई कछुओं की सुनामी, 92 हजार से अधिक कछुए पैदा हुए; वीडियो में दिखा दुर्लभ नजारा

Turtle Tsunami; 92000 Giant South American River Turtles Hatched In Brazil River | ब्राजील में नदी किनारे आई कछुओं की सुनामी, 92 हजार से अधिक कछुए पैदा हुए; वीडियो में दिखा दुर्लभ नजारा

Hindi News Happylife Turtle Tsunami; 92000 Giant South American River Turtles Hatched In Brazil River Ads से है परेशान? बिना Ads खबरों के लिए इनस्टॉल करें दैनिक भास्कर ऐप रियो डी जेनेरियोएक घंटा पहले कॉपी लिंक इनकी देखभाल करने वाली ब्राजील वाइल्डलाइफ कंजर्वेशन सोसायटी ने जारी किया वीडियो अंडे और मांस की तस्करी के कारण इन साउथ अमेरिकन रिवर टर्टल्स की संख्या घट रही है ब्राजील में पुरुस नदी के…

View On WordPress

#arrau turtle#giant Amazon River turtle#Giant South American River turtle#Latest World News#South American river turtle#South American turtle#turtle tsunami#turtle tsunami in brazil#wildlife conservation society brazil#World Headline#World News#World News in Hindi#अबुफारी बायोलॉजिकल रिजर्व#ब्राजील में कछुओं की सुनामी#साउथ अमेरिकन रिवर टर्टल

0 notes

Video

tumblr

Those aren’t rocks, they’re turtles! More than 92,000 giant South American river turtles were just born in the Abufari Biological Reserve in Brazil. The giant South American river turtle can reach 3.5 feet and weigh as much as 200 lbs 🐢

follow @nowthisnews for daily news videos & more

226 notes

·

View notes

Text

Turtle Adoption Day

Turtle Adoption Day is a "day of action for the protection of endangered reptiles." Specifically, the day supports the welfare of turtles. It appears to have been created by a woman named Christine Shaw, who made a blog post on November 25, 2011, on the website of Found Animals, an animal welfare organization that works to find new homes for distressed and abandoned animals. The day was first observed two days later.

Having a turtle as a pet is a large undertaking and can be a lot of work. Turtles have a long lifespan, meaning having one as a pet is a long-term commitment. This may not be ideal for many prospective owners. Turtles also need specialized—and many times expensive—care when it comes to their food, water supply, and cages, which also may not make them ideal pets for many. Additionally, turtles are often carriers of salmonella. Generally, conservation organizations take the view that turtles belong in the wild, not in homes as pets.

Still, many people do get turtles as pets, and Turtle Adoption Day is about reacting positively to some negative decisions others have made in this regard. Some people who get turtles as pets treat them like throw-away pets: they purchase baby turtles, view them as mini-turtles, and give them away or release them into the wild when they grow. When turtles are released into the wild, their chances of survival are slim. Additionally, many turtles are endangered species and are hunted by humans and have threatened habitats. Turtles released in the wild can also become invasive species. They can multiply, and may then damage flora and fauna. But, some turtle owners take them to animal shelters when they get bigger and they don't know how to care for them, instead of releasing them into the wild. It is these turtles that Turtle Adoption Day works to protect.

Turtles live in almost all climates around the world, and are found on every continent except Antarctica. Most species are found in southeastern North America and South Asia. Only five species can be found in Europe. Turtles are part of the order of Testudines, an order that also includes tortoises and terrapins. Testudines are split into two suborders: Cryptodira and Pleurodira. Most turtles are Cryptodira. The main difference between the two is that Cryptodira retract their heads straight back into their shells, while Pleurodira fold their necks to the side when they retract their heads. However, sea turtles, which are Cryptodira, are unable to retract their heads into their shells. Turtles are then split into 13 families and 75 genera, and there are over 300 species in total.

Turtles spend most of their time in the water. Freshwater turtles live in ponds and lakes, coming on land to bask in the sun. Sea turtles spend most of their time in the ocean, coming onshore to lay eggs on the sand. Most of these webbed-feet reptiles have hard shells that protect them from predators. The top part of their shell is called a carapace and the bottom is called a plastron. The carapace is made up of about 60 bones, and is covered with plates made of keratin called scutes. Besides hard-shelled turtles, there are are also soft-shelled turtles and leatherbacks, which have a thick skin covering their carapace.

Turtles are not very social animals. They are most active during the day, when they spend their time searching for food. Most are omnivores, eating animals such as fish, insects, mollusks, crayfish, snakes, frogs, worms, clams, and other turtles, as well as grasses, algae, and other plants. Their diet varies depending on their species, with some subsisting on a mostly vegetarian diet.

Like birds, turtles have beaks and no teeth. They also are egg-laying animals. After digging a nest on land in sand or dirt, they lay their eggs and leave; they don't nurture their young once they are born. Turtles lay between 20 and 200 eggs at a time, depending on their species. Most of their eggs are eaten by carnivores before they hatch, and many are eaten after they are hatched, as the baby turtles do not yet have fully-developed shells to protect themselves.

Turtles vary in size, but some may grow very large. The largest freshwater turtle in North America is the alligator snapping turtle, which can grow up to 2.5 feet in length and weigh up to 200 pounds. The largest sea turtle is the leatherback turtle, which can grow to about 4.5 to 5.25 feet in length and weigh between 600 and 1500 pounds. The largest soft-shelled turtle is the Yangtze giant softshell turtle, which can grow up to 3.6 feet across and weigh as much as 309 pounds.

Many species of turtles are threatened, endangered, or critically endangered. Additionally, many turtles who were once pets have ended up in shelters because their owners weren't able to properly care for them. This makes it even more necessary that there is a day dedicated to caring for and protecting turtles. Today, on Turtle Adoption Day, we do our part to protect turtles by adopting those without homes.

How to Observe Turtle Adoption Day

The most appropriate way to observe the day is to adopt a turtle that was once someone's pet. Turtles can be adopted through Found Animals or Petfinder, or through a reptile rescue organization. They can also be found in local listings such as Craigslist, as well as at local animal shelters. By giving them a new and proper home, you can help preserve one turtle's life, and help protect turtles in general, many species of which face endangerment. If you can't provide a home for a turtle, you could donate to a reptile rescue organization.

Before you adopt a turtle, it is imperative that you are prepared to do so. You must make sure you know what type of environment turtles need in order to live in captivity, and you must have a large enough habitat for your new turtle to live. For example, turtles need at least ten gallons of water per one inch of shell, and for each additional turtle, you need another ten to twenty gallons of water. They need a dry basking area where they can crawl around and dry off, they need access to lamps that give off heat and UVA and UVB rays, they need a submersible heater to keep water at a warm enough temperature, and they need a water conditioning solution and a filter. When adopting a turtle you must also remember that having one as a pet is a long-term commitment, they can be a lot of work, they can take up a lot of your time, and they can be expensive.

Source

#aldabra giant tortoise#Masoala Hall#Zoo Zürich#Zurich#New York City#animal#reptile#original photography#day trip#travel#vacation#tourist attraction#Red-eared Slider#Bronx Zoo#my favorite zoo#USA#TurtleAdoptionDay#TurtleSponsorshipDay#27 November#Giant South American River Turtle#Radiated tortoise#Spider tortoise#Florida#Florida Softshell Turtle#Green Cay Nature Center & Wetlands#East African black mud turtle

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

life.

(source: reuters | 13 jan 2023)

The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) released video footage showing hundreds of thousands of baby giant South American river turtles emerging from nesting beaches along the Guapore/Intenez River, along the border of Brazil and Bolivia.

#giant south american river turtles#world biodiversity#baby turtles#brazil's biodiversity#bolivia's biodiversity

0 notes

Text

In 1979, the Brazilian government moved to protect flora and fauna here, including the turtles, and set up the Trombetas Biological Reserve (REBIO Trombetas), a highly restrictive form of conservation unit, where at first virtually no economic activity was permitted. The area selected, covering 385,000 hectares (1,486 square miles) on the left bank of the Trombetas River, was not, however, uninhabited, for it included two communities of quilombolas — Afro-Brazilians, many of them descendants of runaway slaves. The creation of the REBIO Trombetas in an area occupied by those two traditional communities (the Último Quilombo do Erepecu and Quilombo de Nova Esperança) has created complications and ongoing conflicts that have rippled down through the years to the present day. [...] At the time REBIO Trombetas was founded, many conservationists erroneously believed the Amazon to be a pristine Garden of Eden, best left untouched by humans. As a result, the quilombos were seen as intrusive, and REBIO managers worked hard to prevent long-time traditional inhabitants from using and impacting the rainforest and rivers. Some quilombolas were evicted after 1979, but most remained. They clung tenaciously to their homes, despite draconian [...] restrictions. At the time, it was a criminal offense for local residents to hunt, fish or collect forest products. [...] The two tradtional communities [say] that the government has unfairly penalized them for conducting forest and river livelihoods including Brazil nut collecting [...]. Local residents also contend that while they’re fined for such minor infractions, MRN, the world’s fourth largest bauxite mining company, located near the REBIO, has done extensive ecological damage due to ore ship traffic and water pollution, which severely impacts turtle populations

Since the REBIO was created, many ecologists have changed their Edenic view of the forest and of the impacts traditional communities have on it. The dominant view today is that the vast Amazon rainforest was long ago shaped by humans, and the large concentrations of Brazil nut trees found along Amazonia’s rivers may be an excellent example of the way ancient peoples shaped the forest to better serve human occupation.

As the dry season gets underway in July, the water levels in most Amazon basin rivers fall. As river beaches are exposed, millions of river turtles begin creeping ashore in an eons-old ritual to lay their eggs, burying them in sand dunes flooded half the year.

Among these far traveling chelonians are the Giant South American turtle (Podocnemis expansa). One of the world’s largest freshwater turtles; it can grow to 90 centimeters (nearly three feet) in length, and weigh up to 65 kilograms (145 pounds). [...]

One place they particularly thrive, and a prime spawning spot, is found on the flat dunes along the Trombetas River. Many mating turtles head for Erepecu, an immense lagoon that opens along the left-hand river bank. Between the months of September and November, the Giant South American turtle and other species, such as Yellow-spotted river turtles (Podocnemis unifilis) and the Six-tubercled Amazon river turtle (Podocnemis sextuberculata), arrive and nest. They lay between 15 and 130 eggs on average, depending on species.

The REBIO Trombetas encompasses a large, densely clustered number of Brazil nut trees and those trees are an important source of income for traditional people. [...]

More recently families gained the right to carry out small-scale subsistence farming. “Today we can plant an area of 10,000 square meters [108,00 square feet],” explained [redacted], who lives in the Último Quilombo.

In one important program, local quilombolas are now seen as a vital component of REBIO protection. Today, they protect the nesting sites of the much lauded Trombetas River Turtle Programme, launched in 1979 and continued under IBAMA and ICMBio. Local inhabitants became involved in 2003, in partnership with the environmental agencies.

Under the program, 27 families living in the Último Quilombo and Nova Esperança Quilombo protect the turtles during the breeding season, watching over the beaches and nests during incubation and hatching, keeping poachers and predators away. [...] Researchers say that their work is crucial to the Giant South American turtle [...].

Meanwhile, MRN continues benefiting from the status quo. [...] Ten years after the creation of REBIO Trombetas, Brazilian President José Sarney flew over the region and saw that MRN was directly discharging waste from its huge bauxite mine into once pristine Batata Lake — a notorious Amazon environmental disaster. [...]

“Before the mining company arrived, we just hunted and fished to get food for ourselves ...”

---

Thais Borges and Sue Branford. “Life among the turtles: Traditional people struggle inside an Amazon reserve.” Mongabay. 10 August 2020.

302 notes

·

View notes

Text

Call it a Turtle Tsunami! Thousands of Turtles Appear Together in Brazil

A baby turtle (hatchling) crawling its way up to the surface on a sandy patch is among the most adorable sights one can hope for. Imagine thousands of such hatchlings coming out one on top of another like the waves of a tsunami.

The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) Brazil recently released breathtaking footage showing tens of thousands of Giant South American River turtle hatchlings (Podocnemis expansa) emerging from a sandy beach in a protected area along the Purus River—a tributary of the Amazon River in Brazil.

Calling it a turtle tsunami, WCS Brazil conservationists said the emergence occurred over several days, with around 71,000 hatchlings emerging on one day alone, followed by another 21,000 a few days later. Turtles often lay eggs in batches of 80-120 per individual and prefer an undisturbed region for an approximately 60-day incubation period.

Continue reading.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Titanis walleri

By Scott Reid

Etymology: Titan

First Described By: Brodkorb, 1963

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Australaves, Cariamiformes, Phorusrhacoidea, Phorusrhacidae, Phorusrhacinae

Status: Extinct

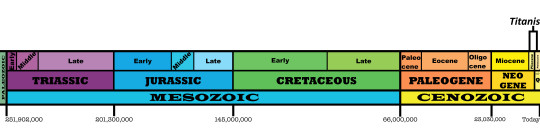

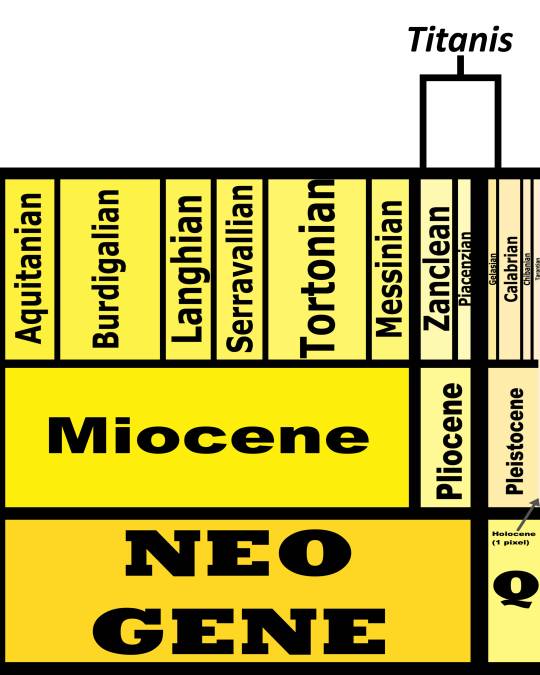

Time and Place: Between 5 and 1.8 million years ago, from the Zanclean to the Gelasian ages of the Pliocene through Pleistocene

Titanis is known from the Santa Fe River and Nueces River Formations of Florida and Texas

Physical Description: Titanis was a Terror Bird, one of the largest known Terror Birds, a group of large flightless predatory birds that terrorized the Americas during the Cenozoic Era, right up until humans would have appeared on the scene. Titanis is one of the latest members of this group, and the one that made the journey up to North America - most Terror Birds are from South America. It would have been 2.5 meters tall - much taller than a person - and would have weighed 150 kilograms. There was a lot of variance in size and height, however, indicating that Titanis may have had at least some sexual dimorphism. It had a short tail and round body, with long and powerful legs. In fact, it also had very robust toes - and one of the strongest middle toes known for a Terror Bird. It had very small, useless wings, that were very much locked in against the body - they didn’t have a lot of folding power compared to other birds. This indicates the wings really were… useless. They didn’t use them for raptor prey restraint or anything else, making them distinctly different from the Dromaeosaurids of long past. Titanis had a very thick neck, which would have supported a large head with a very impressive and terrifying hooked bill - complete with extensive crunching power!

By Dmitry Bogdanov, CC BY-SA 3.0

Diet: As a Terror Bird, Titanis primarily ate large mammals - and some medium and small sized mammals, of course, but basically it was able to cronch anything around it.

Behavior: Terror Birds are most closely related to modern Seriemas, and so a lot of their behavior has been guessed based on Seriemas today. As such - and given that it didn’t have much in the way of wings - Titanis probably mainly relied on its feet in kicking its prey to death. It would chase its food down, kick it, and potentially pin it down. Then, final death blows would have been delivered with the powerful cronch of its beak, though of course the hook on the beak would have allowed increased tearing and shredding. While modern Seriemas are solitary, it is possible that Titanis and other Terror Birds may have used groups to take down larger prey, though they probably would have been more groups of convenience than formal packs. It is possible they had similar breeding habits to living Seriemas, but even that is a question - their larger size, different niche, and general different time periods would provide large differences. And we don’t even know the actual breeding habits of Seriemas very well! So, that being said, Titanis would have probably been fairly territorial over their nests, and both parents were probably involved in the care of the nest and then the young, even after fledging. The young would follow the parents around until reaching maturity. As such, it’s possible that the parents may have hunted for the young, and brought food back for them until they were old enough to hunt for themselves. Then, upon leaving the parents, they probably would have been fairly solitary until finding a mate of their own.

By José Carlos Cortés

Ecosystem: Titanis primarily lived in open grassland habitats in the southern parts of the United States, clearly extending from Texas through to Florida and probably found all over that range. It stuck to warmer, probably wetter habitats, though the exact environments it lived in aren’t very well studied in terms of general flora. Fauna, however, is well known. Titanis lived alongside a wide variety of other animals - in Citrus County, it was found with a variety of frogs, turtles, lizards, rabbits, horses, shrews, bears, dogs, mustelids, and cats (including Smilodon), armadillos, sloths, the Mastodon, cows, peccaries, camels, and deer. There were, of course, many dinosaurs as well - in addition to Titanis, there were waders (indicating a non-insignificant amount of water in this ecosystem, possible coastline, swamps, or lakes), vultures, pheasants, ducks, falcons, owls, pigeons (including the passenger pigeon), woodpeckers, blackbirds, corvids, sparrows, finches, flycatchers, cardinals, rails, grebes, herons, bitterns, and buzzards. Basically, a fairly typical array of North American birds! In Gilchrist County, Titanis also lived alongside similar creatures, including Smilodon, though without the Mastodon - though there was Rhynchotherium! Unfortunately, its Texan relatives aren’t well known, though it stands to reason that it would have been similar to other locations.

By Ripley Cook

Other: Titanis is one of the largest known Terror Birds, and one of the largest known ones discovered early in our understanding of Terror Birds. In fact, we knew about Titanis so early on that there are a lot of old depictions of it - including ones where it has… hands. Clawed hands. That is very much wrong and cringy, but hey, there are pictures of it! Titanis is also fascinating because of its place in Earth’s History - it is one of the (only?) known Terror Birds from North America. This occurred due to the Great American Interchange, a sort of mini-columbian exchange where North America and South America combined, leading to the mixing of animals from both continents together. The traditional narrative says that Terror Birds went extinct because sabre-toothed cats came in from North America, but this is flawed for three very big reasons: 1) there were already Sabre Toothed animals filling that niche in South America, they were just Marsupials; 2) Terror Birds stuck around for a long time after the Interchange, and 3) Terror Birds reached North America in return! So Titanis helps to showcase that Terror Birds were doing just fine during this ecological exchange. So why did it - and other Terror Birds - go extinct? Probably the Ice Age, though for now, we can’t be sure. Regardless, they went extinct… probably before people got there. There are fossils that might be Titanis from 15,000 years ago, which would indicate they were still there when people got there. Which is terrifying. And also might point to humans being the cause of their extinction. Still, that seems unlikely, and they were definitely on the decline before then - so the Ice Age seems like the most logical explanation.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Alroy, John, Ph.D. Synonymies and reidentifications of North American fossil mammals, 2002. John P. Hunter, Ohio State University, Mammalian Paleontology.

Alvarenga, H. M. F.; Höfling, E. (2003). "Systematic revision of the Phorusrhacidae (Aves: Ralliformes)". Papéis Avulsos de Zoologia. 43 (4): 55–91.

Alvarenga, H.; Jones, W.; Rinderknecht, A. (May 2010). "The youngest record of phorusrhacid birds (Aves, Phorusrhacidae) from the late Pleistocene of Uruguay". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen. 256 (2): 229–234.

Baskin, J. A. (1995). "The giant flightless bird Titanis walleri (Aves: Phorusrhacidae) from the Pleistocene coastal plain of South Texas". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 15 (4): 842–844.

Bertelli, S., L. M. Chiappe, and C. Tambussi. 2007. A new phorusrhacid (Aves: Cariamae) from the Middle Miocene of Patagonia, Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 27(2):409-419.

Brodkorb, P. (1963). "A giant flightless bird from the Pleistocene of Florida". Auk. 80 (2): 111–115.

Carroll, R. L. 1988. Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution 1-698

Chandler, R.M. (1994). "The wing of Titanis walleri (Aves: Phorusrhacidae) from the Late Blancan of Florida". Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History, Biological Sciences. 36: 175–180.

Cracraft, Joel, A review of the Bathornithidae (Aves, Gruiformes), with remarks on the relationships of the suborder Cariamae. American Museum Novitates ; no. 2326.

De Iuliis, G., and C. Cartelle. 1999. A new giant megatheriine ground sloth (Mammalia: Xenarthra: Megatheriidae) from the late Blancan to early Irvingtonian of Florida. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 127:495-515

Degrange, Federico J.; Tambussi, Claudia P.; Moreno, Karen; Witmer, Lawrence M.; Wroe, Stephen; Turvey, Samuel T. (18 August 2010). "Mechanical Analysis of Feeding Behavior in the Extinct "Terror Bird" Andalgalornis steulleti (Gruiformes: Phorusrhacidae)". PLoS ONE. 5 (8): e11856.

Ehret, D. J., and J. R. Bourque. 2011. An extinct map turtle Graptemys (Testudines, Emydidae) from the Late Pleistocene of Florida. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 31(3):575-587

Emslie, S. D. 1998. Avian community, climate, and sea-level changes in the Plio-Pleistocene of the Florida Peninsula. Ornithological Monographs (50)1-113

Emslie, S. D., and N. J. Czaplewski. 1999. Two new fossil eagles from the late Pliocene (late Blancan) of Florida and Arizona and their biogeographic implications. Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology 89:185-198.

Franz, R., and I. R. Quitmyer. 2005. A fossil and zooarchaeological history of the gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus) in the Southeastern United States. Bull. Fla. Mus. Nat. History 45(4):179-199.

Gibbons, J. W., and M. E. Dorcas. 2004. North American Watersnakes: A Natural History. 1-438.

Gould, G.C. & Quitmyer, I.R. (2005). "Titanis walleri: bones of contention". Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History. 45: 201–229.

Hulbert, R. C. 1995. Equus from Leisey Shell Pit 1A and other Irvingtonian localities from Florida. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History 37(17):553-602.

Hulbert, R. C. 2010. A new early Pleistocene tapir (Mammalia: Perissodactyla) from Florida, with a review of Blancan tapirs from around the state. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History 49(3):67-126.

MacFadden, Bruce J.; Labs-Hochstein, Joann; Hulbert, Richard C.; Baskin, Jon A. (2007). "Revised age of the late Neogene terror bird (Titanis) in North America during the Great American Interchange". Geology. 35 (2): 123–126.

Marsh, O. C. (1875). "On the Odontornithes, or birds with teeth". American Journal of Science. 10 (12): 403–408.

Mayr, G. 2009. Paleogene Fossil Birds. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

Mayr, G. 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance. Topics in Paleobiology, Wiley Blackwell. West Sussex.

McDonald, H. G. 1995. Gravigrade xenarthrans from the early Pleistocene Leisey Shell Pit 1A, Hillsborough County, Florida. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History 37(11).

Meachen, J. A. 2005. A new species of Hemiauchenia (Artiodactyla, Camelidae) from the late Blancan of Florida. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History 45(4):435-447.

Meylan, P. 2001. Late Pliocene anurans from Inglis 1A, Citrus County, Florida. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History 45(4):171-178.

McFadden, B.; Labs-Hochstein, J.; Hulbert, Jr., R. C.; Baskin, J. A. (2006). "Refined age of the late Neogene terror bird (Titanis) from Florida and Texas using rare earth elements". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (3): 92A (Supplement).

Morgan, G. S., and R. B. Ridgway. 1987. Late Pliocene (late Blancan) vertebrates from the St. Petersburg Times site, Pinellas County, Florida, with a brief review of Florida Blancan faunas. Papers in Florida Paleontology 1:1-22.

Morgan, G. S. 1991. Neotropical Chiroptera from the Pliocene and Pleistocene of Florida. In T. A. Griffiths, D. Klingener, (eds.), Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 206:176-213.

Morgan, G. S., and R. C. Hulbert. 1995. Overview of the geology and vertebrate biochronology of the Leisey Shell Pit Local Fauna, Hillsborough County, Florida. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History 37(1).

Morgan, G. S., and J. A. White. 1995. Small mammals (Insectivora, Lagomorpha, and Rodentia) from the early Pleistocene (early Irvingtonian) Leisey Shell Pit Local Fauna, Hillsborough County, Florida. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History 37(13).

Robertson, J. S. 1976. Latest Pliocene mammals from Haile XV A, Alachua County, Florida. Bulletin of the Florida State Museum 20(3):1-186.

Ruez, D. R. 2001. Early Irvingtonian (latest Pliocene) rodents from Inglis 1C, Citrus County, Florida. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 21(1):153-171.

Tambussi, Claudia P.; de Mendoza, Ricardo; Degrange, Federico J.; Picasso, Mariana B.; Evans, Alistair Robert (25 May 2012). "Flexibility along the Neck of the Neogene Terror Bird Andalgalornis steulleti (Aves Phorusrhacidae)". PLoS ONE. 7 (5): e37701.

Tedford, R. H., X. Wang, and B. E. Taylor. 2009. Phylogenetic Systematics of the North American Fossil Caninae (Carnivora: Canidae). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 325:1-218.

Webb, S. D. 1974. Chronology of Florida Pleistocene mammals. In S. D. Webb (ed.), Pleistocene Mammals of Florida 5-31.

Webb, S. D., and K. T. Wilkins. 1984. Historical Biogeography of Florida Pleistocene Mammals. In H. H. Genoways and M. R. Dawson (eds.), Carnegie Museum of Natural History Special Publication 8:370-383.

White, J. A. 1991. A new Sylvilagus (Mammalia: Lagomorpha) from the Blancan (Pliocene) and Irvingtonian (Pleistocene) of Florida. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 11(2):243-246.

#Titanis walleri#Titanis#Bird#Terror Bird#Dinosaur#Dinosaurs#Raptor#Bird of Prey#Birds#Palaeoblr#Birblr#Factfile#Australavian#Cariamiform#Theropod Thursday#North America#Neogene#Quaternary#Carnivore#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

471 notes

·

View notes

Text

Got To Be NC!

As you might know, I am a huge fan of parks. Some of my favorite public lands are the very ones in my home state of North Carolina. I have lived here my whole life and have been visiting these parks since I was a kid. Although I have not visited all of them, one day I know I will. So, enjoy this list (and review) of the beautiful parks of NC!

1. Carolina Beach

Fun Fact: Carolina Beach is one of the only places you can find the carnivorous Venus Flytrap and Pitcher Plant in the wild. This park is home to a subtropical wetland, which is the perfect ecosystem for these carnivorous plants. While you may be tempted to take one home with you, beware because the state of North Carolina made it a felony to poach Venus Flytraps in 2014. Also in the park is Sugarloaf Dune, which has been used as a navigational marker since 1633. In total, the park has 7 miles of trail, and is one I have visited many times during my stays in Wilmington.

2. Carvers Creek

3. Chimney Rock

This spire of rock is instantly recognizable to anyone within miles. Chimney Rock is 315 foot tall and overlooks Hickory Nut Gorge and Lake Lure. “Lake Lure?” you may ask, yes Lake Lure. The spot where they filmed the unforgettable lake scene in Dirty Dancing, as well as the scene of Baby dancing down the stairs. The town is also home to an annual Dirty Dancing festival, so you might want to plan your trip when Baby and Johnny are back in town. As well as Dirty Dancing, you may recognize this park from the climax scene in The Last of the Mohicans.

4. Crowders Mountain

5. Dismal Swamp

6. Elk Knob

7. Eno River

8. Falls Lake

9. Fort Fisher

Home to the Civil War-Era bunkers and one of the best aquariums in North Carolina. Fort Fisher is a hidden gem in ENC. As a student at UNC at Wilmington, I know all to well about the beach. I know where to find a dirty beach, a crowded beach, and I certainly know how to find a good beach. Fort Fisher is just that. You can sit on the sand and watch the pelicans fly overhead and the cargo ships come into port without the worry of trash and dirty water. Because it is a state park/recreation area, it is kept very clean and has nicer facilities than public beaches in the area. It also has 4 wheel drive access to the beach. If you are visiting, don’t forget to stop by and see Luna, the albino alligator at the aquarium.

10. Fort Macon

Fort Macon! This place is probably one of the most interesting places in North Carolina. I recently wen there with my little brother to have a little day trip. The park itself is a beautiful ecosystem, as the Musgrove trees are my favorite. We stopped first at the beach was had clear water and a great view of the Cape Lookout lighthouse from the shore. Next we went to the actual fort which was the best part of the trip. Walking throughout the fort you see rich stone works and manicured lawns. I got some really cool Insta and VSCO photos here as well. Highly recommen!

11. Goose Creek

12. Gorges

13. Grandfather Mountain

One of the windiest spots in the entire state. Grandfather Mountain is home to the famous mile-high swinging bridge. Walking across the bridge is both exhilarating and terrifying. As requested by the staff, hold on to your belongings, and even small children, to keep them form blowing into the valley below. It is also home to an amazing zoo that houses black bears and mountain lions.

14. Hammocks Beach

Hammocks Beach State Park is a park I visit quite often as it is only about 30 minutes from where I live. I have visited both the mainland site, which has an amazing visitors center and serene wooded trails, and the Bear Island site. Bear Island is a 3-mile long barrier island that is home to nesting sea turtles and clean beaches. A ferry, kayak, or personal boat can take you over to the island to enjoy the water!

15. Hanging Rock

16. Haw River

17. Jockey’s Ridge

My favorite! Jockey’s Ridge is located in Nags Head, North Carolina, right next to Kitty Hawk, the site of the first human flight. Jockey’s Ridge is the tallest active sand dune on the Atlantic Coast. Hiking through this park feels like you are in Star Wars! Some of my favorite activities to do are sandboarding down the giant dunes and paragliding. Jockey’s Ridge to me is the most fun and the most beautiful of all the parks I have visited.

18. Jones Lake

One of the two lakes formed by the geological phenomenon called Carolina Bays. This phenom creates lakes of varying pH levels, resulting in different coloration of the water. Jones Lake is colored a bright red color. This lake has great swimming and fishing. Beware alligators though!

19. Jordan Lake

Jordan Lake is like other lakes in my state, but the one things that makes it interesting: the Bald Eagle. Jordan Lake is the summertime home of this rare species. It is fascinating to watch this birds fly and hunt for prey. You can enjoy swimming and hiking, as there is 15 miles of trails throughout the park.

20. Kerr Lake

Another amazing park in the beautiful state of NC! Just like Jorden Lake, it is also home to a bald eagle. We have camped on the shore a few times and I love waking up early to watch the sun rise over the lake. We take our boat and pull our tubes. Another great thing this park has is rolling, smooth roads. Take your longboard and carve down these streets. There is also a really nice marina down the road who has killer ice cream.

21. Lake James

22. Lake Norman

23. Lake Waccamaw

Just like Jones and Carolina Beach, these park is home to some cool species. The American alligator and the Venus Flytrap are easy to find in this swampy park. While the slews and backcountry of this park are full of blood-sucking mosquitos and alligators, the lake front dock is an amazing spot to swim. The pH level of this lake makes it perfectly clear. Not only is it clear, but it also is only about 4 feet deep which makes it perfect for younger or inexperienced swimmers to have fun without all the worry. I personally like driving around and seeing all the beautiful lakes houses after taking a swim, but there is also a really nice restaurant on the lake front that I’ve heard has amazing burgers.

24. Lumber River

Lumber River is the only black water river in North Carolina, and is also a National Wild and Scenic River. This park ahs great kayaking, but beware alligators.

25. Mayo River

26. Medoc Mountain

27. Merchants Millpond

28. Morrow Mountain

29. Mount Jefferson

It is our family tradition to go every Thanksgiving to get our Christmas tree from the mountains. So, last year we decided to go to West Jefferson and we visited Mount Jefferson State Park. It was approximately 17 degrees and there was ice everywhere, but we hiked to the top and enjoyed the view of the valley below. One of the coolest things about Mt. Jefferson is the Luther Rock. This rock juts from the side of the mountain and allows you to walk out on it and take in the beautiful scenery.

30. Mount Mitchell

Mount Mitchell is the tallest mountain east of the Mississippi River. The observation area at the top allows for you to see as far as 85 miles on a clear day. Just make sure as you head up, you layer up because it can drop temperature very quickly.

31. New River

32. Occoneechee

33. Pettigrew

34. Pilot Mountain

35. Raven Rock

Oh Raven Rock! We took this trip after a long day at the ball field on my mom’s 40th birthday. Needless to say we were tired, but we still decided to tackle the 4.2 mile hike to the Raven Falls. We were expecting a waterfall, but instead we got rapids. We did however cool off in the river before taking our long hike back. Despite this, the actual Raven Rock was beautiful and the park is still on of my favorites.

36. Singletary Lake

The best thing about this lake is how secluded it is. It is tucked away behind a tree line and barely visible from the road. The only people that frequent this are its junior campers. You can enjoy a peaceful evening fishing on its 500 foot peer and if you’re feeling lucky test your swimming skills with the alligators.

37. South Mountain

38. Stone Mountain

39. Weymouth Woods Sandhills

40. William B. Umstead

I just recently took my second trip to this park and it is still as beautiful as the first time. There are over 35 miles of hiking in this park so it is very unlikely you will see it all. While I do love hiking, I enjoy just driving through the park as well. The stone bridge over Sycamore Creek is one of my favorite spots as it has rolling fields of grass that you can lie down in and have a picnic if you please.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

300 Myth Horrors

These are all 300 mythology creatures in my project, when I add one, I must remove one

*name* = Another name for the same monster, so the Minotaur in my project is also known as Sarangay for example, they aren’t other creatures, they are exactly the same creature, just another name for it.

Bold-names mean that these creatures don’t evolve into a better form, most creatures have one evolution/upgrade, but the bold ones never evolve as I could not make up a cool new form for the creature, as most of them already have cool forms.

The creatures are collected on the mythology I took them from it goes from: Ancient Greek Mythology -> North European Myths -> East European Myths -> South and Central European Myths -> West European/Celtic Myths -> North American Myths -> South and Central American Myths -> African Myths -> Middle-Eastern & Arabian Myths -> Asian/Chinese Myths -> Japanese Myths -> Polynesian Myths -> Australian Myths

1: Amphisbaena (Beast) 2: Argus *Hyakume* (Aberration) 3: Celedon *Gold Golem* (Construct) 4: Centaur (Humanoid) 4,5: Centaur, Anggitay (Humanoid) 5: Cerberus (Demon) 6: Charybdis (Aberration) 7: Chrysaor (Humanoid) 8: Dactyl *Cabeiri* (Humanoid) 9: Empusa (Demon) 10: Erinyes *Fury* (Demon) 11: Gegenees (Humanoid) 12: Gorgon *Medusa* (Humanoid) 13: Griffon (Chimerae) 13,5: Griffon, Keythong (Chimerae) 14: Harpy *Siren* (Humanoid) 15: Hydra (Beast) 16: Kampe (Humanoid) 17: Karkinos *Saratan* (Beast) 18: Lampad (Fey) 19: Makhai (Demon) 20: Minotaur *Sarangay* (Humanoid) 21: Planctae *Symplegades* (Elemental) 22: Scorpios *Sandwalker* (Beast) 23: Scylla (Aberration) 24: Stymphalides (Construct) 25: Baldanders *Gardinel* (Aberration) 26: Berserker (Humanoid) 26,5: Berserker, Einherjar (Undead) 27: Buckrider (Humanoid) 28: Doppelganger *It* (Aberration) 29: Gloson *Gravso* (Undead) 30: Goblin (Humanoid) 31: Gulon *Taotie* (Beast) 32: Havhest (Beast) 33: Helhest (Undead) 34: Hrimpursar *Frost Giant* (Humanoid) 35: Iku-Turso (Aberration) 36: Kobold (Fey) 37: Landvaettir *Land Wight* (Elemental) 38: Mandragora *Mandrake* (Plant) 39: Morko *Groke* (Aberration) 40: Nidhogg (Dragon) 41: Osschaert (Fey) 42: Radande (Plant) 43: Salamander (Beast) 44: Swamfisk (Aberration) 45: Trolual *Leviathan* (Beast) 46: Valravn *Nachtkrapp* (Fey) 47: Ziphius *Sverdhvalur* (Chimerae) 48: Ankluz (Construct) 49: Arzhavennik (Demon) 50: Bagiennik (Fey) 51: Bolla *Kulshedra* (Dragon) 52: Bubak (Construct) 53: Bukavac (Chimerae) 54: Ebajalg *Ala* (Elemental) 55: Kikimora (Fey) 56: Leshy (Fey) 57: Likho (Demon) 58: Moroi *Strigoi* (Undead) 59: Nocnitsa *Night Hag* (Demon) 60: Poludnica *Lady Midday* (Fey) 61: Psoglav (Demon) 62: Rusalka (Undead) 62,5: Rusalka, Topielec *Draugr* (Undead) 63: Stuhac (Demon) 64: Vodyanoi *Bolotnik* (Humanoid) 65: Zirnitra (Dragon) 66: Zlatorog *Goldhorn* (Fey) 67: Zmey *Balaur* (Dragon) 68: Aatxe *Khalkotauroi* (Undead) 69: Agrippa (Construct) 70: Aproxis (Plant) 71: Barometz (Plant) 72: Basilisk *Cockatrice* (Chimerae) 73: Blemmyes *Xing Tian* (Aberration) 74: Butatsch (Aberration) 75: Caladrius (Beast) 75,5: Caladrius, Zhenniao (Beast) 76: Cerastes *Sierpa* (Beast) 77: Codrille (Dragon) 78: Colorobetch (Aberration) 79: Cuelebre (Dragon) 80: Echeneis *Remora* (Beast) 81: Egregore (Construct) 82: Gargoyle *Grotesque* (Elemental) 83: Gastarios (Beast) 84: Gaueko (Elemental) 85: Gold-Digging Ant *Formica Aurum* (Construct) 86: Imp *Skrzak* (Demon) 87: Incubus *Succubus* (Demon) 88: Lou Carcolh (Aberration) 89: Marabbecca (Aberration) 90: Muscaliet (Chimerae) 91: Myrmecoleon (Beast) 92: Odontotyrannus (Demon) 93: Phoenix *Firebird* (Elemental) 93,5: Phoenix, Psonen (Undead) 94: Pyrausta *Pyrallis* (Dragon) 95: Scytalis (Chimerae) 96: Stella (Aberration) 97: Tarasque (Chimerae) 98: Velue *Peluda* (Dragon) 99: Yale *Centicore* (Beast) 100: Afanc *Addanc* (Chimerae) 101: Alp-Luachra (Aberration) 102: Awd Goggie (Fey) 103: Banshee (Undead) 104: Barghest *Cadejo* (Undead) 105: Boobrie (Beast) 106: Brollachan *Fear Liath* (Elemental) 107: Bruch (Beast) 108: Buggane (Chimerae) 109: Burach Bhadi *Wizard Shackle* (Aberration) 110: Caorthannach *Ajatar* (Demon) 111: Clurichaun (Fey) 112: Cu Sith *Cwn Annwn* (Fey) 113: Dullahan *Coiste Bodhar* (Undead) 114: Fachen *Abaasy* (Aberration) 115: Fomorian (Humanoid) 116: Gancanagh (Fey) 117: Grindylow (Humanoid) 118: Kelpie *Ceffyl Dwr* (Fey) 119: Knucker (Dragon) 120: Lavellan (Beast) 121: Leanan Sidhe (Fey) 122: Lunantishee (Plant) 123: Marool (Demon) 124: Morgawr (Beast) 125: Muirdris (Aberration) 126: Nuckelavee (Fey) 127: Phooka *Puck* (Fey) 128: Redcap *Dunter* (Fey) 129: Sianach *Delgeth* (Beast) 130: Sluagh (Undead) 131: Stray Sod *Hungry Grass* (Plant) 132: Water Leaper *Llamhigyn Y Dwr* (Chimerae) 133: Will o Wisp *Luz Mala* (Elemental) 134: Agropelter (Fey) 135: Ahkiyyini (Undead) 136: Akhlut *Amarok* (Beast) 137: Amhuluk (Dragon) 138: Amikuk (Aberration) 139: Aniwye (Beast) 140: Baykok (Undead) 141: Cactus Cat (Plant) 142: Engulfer *Hinqumemen* (Elemental) 143: Ewah (Aberration) 144: Gaasyendietha (Dragon) 145: Haietlik (Dragon) 146: Hidebehind (Fey) 147: Ijiraq (Fey) 148: Kokogiak *Qupqugiaq* (Beast) 149: Mahaha (Demon) 150: Mishibizhiw *River Panther* (Chimerae) 151: Oniate (Undead) 152: Piasa (Chimerae) 153: Pukwudgie (Fey) 154: Qalupalik (Aberration) 155: Rock Bolter (Beast) 156: Roperite (Beast) 157: Rougarou *Skinwalker* (Humanoid) 158: Squonk (Aberration) 159: Tailypo (Fey) 160: Wendigo *Chenoo* (Elemental) 161: Ahuizotl (Chimerae) 162: Caleuche *Ghost Ship* (Construct) 163: Camazotz (Beast) 164: Camulatz (Beast) 165: Carbuncle (Fey) 166: Cherufe (Elemental) 167: Chon-Chon *Flying Head* (Undead) 168: Chupacabra (Aberration) 169: Cipactli (Chimerae) 170: Cuero (Aberration) 171: Eintykara (Fey) 172: Guarana (Plant) 173: Inulpamahuida (Fey) 174: Invunche *Flesh Golem* (Construct) 175: Itzpapalotl (Fey) 176: Kayeri (Plant) 177: Kori (Beast) 178: Lagahoo (Construct) 179: Lechuza *Strix* (Fey) 180: Mapinguari (Beast) 181: Nguruvilu (Chimerae) 182: Soucouyant *Candileja* (Elemental) 183: Stoa (Demon) 184: Tunche (Elemental) 185: Xan *Moskitto* (Beast) 186: Xhumpedzkin *Ix-Hunpedzkin* (Beast) 187: Adze (Fey) 188: Asanbosam (Humanoid) 189: Catoblepas (Beast) 190: Chipfalamfula (Beast) 191: Eloko *Biloko* (Humanoid) 192: Ga-Gorib (Chimerae) 193: Gbahali (Chimerae) 194: Grootslang (Chimerae) 195: Ichneumon (Beast) 196: Impundulu *Lightning Bird* (Demon) 197: Intulo (Humanoid) 198: Jba Fofi (Beast) 199: Kerit *Nandi Bear* (Aberration) 200: Kongamato *Ropen* (Beast) 201: Leucrotta *Crocotta* (Chimerae) 202: Makalala (Beast) 203: Mbielu-Mbielu (Plant) 204: Migas (Aberration) 205: Mngwa (Undead) 206: Popobawa (Demon) 207: Rompo (Chimerae) 208: Umdhlebi (Plant) 209: Ya-Te-Veo (Aberration) 210: Zombie *Aerico* (Undead) 211: Acheri *Drekavac* (Undead) 212: Ahl At-Trab (Elemental) 213: Ammut (Chimerae) 214: Asdeev (Dragon) 215: Bushyasta (Demon) 216: Caspilly (Beast) 217: Druj Nasu (Demon) 218: Dybbuk (Undead) 219: Fulad-Zereh (Demon) 220: Ghul (Undead) 221: Girtablilu *Aqrabuamelu* (Humanoid) 222: Ifrit (Elemental) 223: Juggernaut (Construct) 224: Karkadann *Indrik* (Beast) 225: Manticore (Chimerae) 226: Miraj *Almiraj* (Beast) 227: Mummy (Undead) 228: Salawa *Sha* (Beast) 229: Scarab *Khepri* (Beast) 230: Vish Kanya *Saapin* (Humanoid) 231: Death Worm *Olgoi-Khorkhoi* (Aberration) 232: Dijiang *Hundun* (Aberration) 233: Dragon Turtle *Longgui* (Dragon) 234: Gu (Elemental) 235: Jinmenju (Plant) 236: Kumiho (Fey) 236,5: Kumiho, Sessho-Seki (Undead) 237: Pixiu (Construct) 238: Qinyuan (Chimerae) 239: Shen (Aberration) 240: Tenaga-Jin *Ashinagatenaga* (Humanoid) 241: Terra-Cotta (Construct) 242: Akaname (Aberration) 243: Akashita (Demon) 244: Bakekujira (Undead) 245: Baku (Chimerae) 246: Dorotabo (Elemental) 247: Enenra (Elemental) 248: Garei (Construct) 249: Gashadokuro (Undead) 250: Heikegani (Demon) 251: Isonade *Akheilos* (Beast) 252: Ittan-Momen (Construct) 253: Jorogumo *Arachne* (Fey) 254: Jubokko (Plant) 255: Kamaitachi (Fey) 256: Kappa *Suiko* (Chimerae) 257: Keukegen (Construct) 258: Muramasa *Cursed Sword* (Construct) 259: Namazu (Beast) 260: Nekomata *Kasha* (Demon) 261: Nue (Chimerae) 262: Nurikabe (Aberration) 263: Omukade (Demon) 264: Raiju (Elemental) 265: Rokurokubi (Humanoid) 266: Sazae-Oni (Demon) 267: Tesso (Humanoid) 268: Tsuchigumo (Demon) 269: Umibozu (Undead) 270: Ungaikyo (Construct) 271: Wanyudo (Construct) 272: Yuki-Onna (Undead) 273: Zorigami (Construct) 274: A Bao A Qu (Aberration) 275: Abaia (Fey) 276: Abere *Xtabay* (Plant) 277: Adaro *Zitiron* (Humanoid) 278: Ahool (Chimerae) 279: Aswang *Manananggal* (Demon) 280: Batibat *Bangungot* (Demon) 281: Berberoka (Plant) 282: Bonguru (Fey) 283: Con Rit *Skolopendra* (Beast) 284: Dalaketnon (Fey) 285: Jenglot (Construct) 286: Kapre *Yehwe Zogbanu* (Fey) 287: Mandarangkal (Demon) 288: Nuno *Trenti* (Plant) 289: Polong (Elemental) 290: Sigbin (Demon) 291: Tikbalang (Fey) 292: Tiyanak *Myling* (Undead) 293: Bunyip *Dingonek* (Beast) 294: Burrunjor *Kasai Rex* (Beast) 295: Drop Bear (Beast) 296: Nadubi (Demon) 297: Papinijuwari (Aberration) 298: Porotai (Fey) 299: Wulgaru *Wood Golem* (Construct) 300: Yara-Ma-Yha-Who (Aberration)

33 notes

·

View notes