#Australavian

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Danielsraptor vs Heracles

Factfiles:

Danielsraptor phorusrhacoides

Artwork by @otussketching, written by @zygodactylus

Name Meaning: Michael Daniels’ Terror Thief Bird

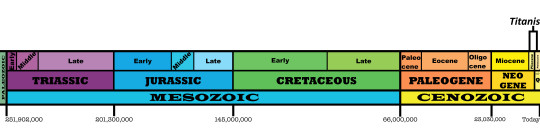

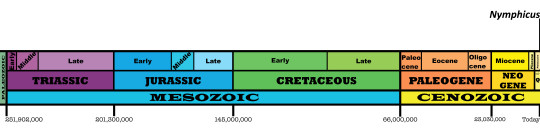

Time: 55 million years ago (Ypresian stage of the Eocene epoch, Paleogene period)

Location: Walton Member, London Clay Formation, England

While the Eocene fossil records of Seriemas, Passerines, and Parrots are fairly well known, the last remaining group of Australavians - the Falcons - remains something of a mystery. Danielsraptor helps to put together this puzzle a little more. Along with Masillaraptor, these birds show an early radiation of falcon-relatives from the Eocene in which they tried out a more terrestrial lifestyle! Danielsraptor had long legs, allowing it to forage and hunt on the ground like modern caracaras. It had a very large pygostyle, giving it long tail feathers - and with strong wing bones, it was able to fly in addition to hunt on the ground. It had a beak very similar to living caracaras and the extinct Terror Birds, further corroborating the idea that it was a bird of prey (and also potentially indicating a more complex evolutionary story for the early-derived Australavians). Living in the London Clay, Danielsraptor would have been one of the top predators, easily hunting the small mammals as well as the birds it shared its environment with - aided by both its terrestrial stalking abilities as well as its flying capability. Living in the London Clay, it shared its environment with the early loon Nasidytes, early owls, trogons, paleognaths, tropicbirds, duck-screamers, other diurnal raptors, the pseudotoothed bird Dasornis, and many parrot-passerine relatives. Crocodilians, snakes, turtles, fish, sharks, and a handful of mammals (including a primate) also lived in this rich post-Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum environment.

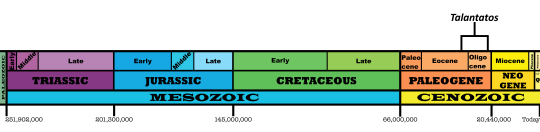

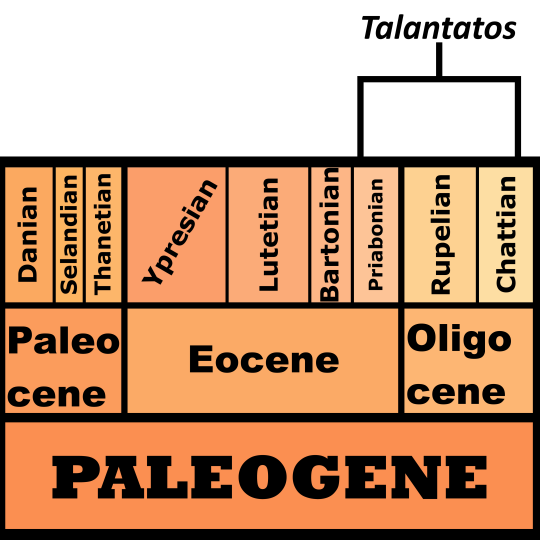

Heracles inexpectatus

Artwork by @otussketching, written by @zygodactylus

Name Meaning: Unexpected Herculean Parrot

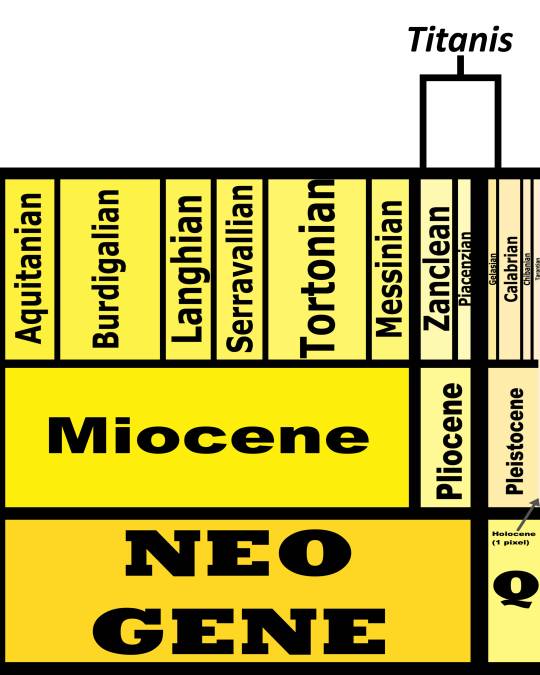

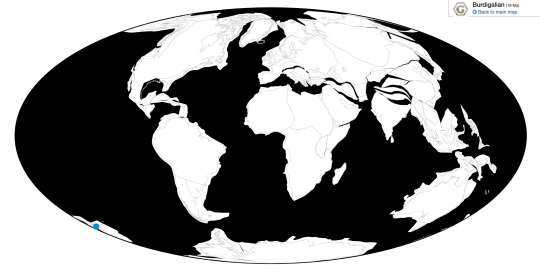

Time: 16 to 19 million years ago (Burdigalian stage of the Miocene epoch, Neogene period)

Location: St. Bathans Fauna, Bannockburn Formation, Aotearoa

Heracles was a truly alarmingly large parrot, related to modern day Kea, Kaka, and Kakapo, known from the fantastic avifauna of St Bathans. Standing more than two feet tall and weighing about fifteen pounds, this animal was much larger than any expected from the St Bathans fauna, which represented the initial colonization of Aotearoa (Zealandia) after it returned above sea level. Heracles is also the largest known species of parrot, ever. It was presumably flightless, though it is uncertain if it was nocturnal like its living relative the Kakapo. Its exact ecology is still uncertain, given the material known from Heracles is limited and its living relatives have very disparate ecologies, though it is possible it was omnivorous similar to the Kea and Kaka today. The St Bathans fauna lived in a freshwater lake system, in a subtropical emergent rainforest. Separated from land bridges, the fauna was dominated by birds, with early relatives of the Kiwi, New Zealand Wrens, Adzebills, and Wedge-Tailed eagles found in the fauna, as well as somewhat modern looking Moas. Smaller flamingos, large fruit pigeons, and a huge variety of geese and other waterfowl are known. In addition, frogs, tuataras, other lizards, crocodilians, turtles, and many different types of fish are known from this fascinating ecosystem.

DMM Round One Masterpost

#dmm#dinosaur march madness#dmm round one#dmm rising stars#palaeoblr#dinosaurs#paleontology#bracket#march madness#danielsraptor#heracles#polls

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

hang on this is techically a reply to joelle abt owl metazooa but its my own. More information than needed quick wiki look up soooo

looks like. tyto and strigidae. both owls. within strigiformes. and thats still owls. and the only thing between that and just. Aves. is

Telluraves (also called land birds or core landbirds) is a recently defined[2] clade of birds defined by their arboreality.[3] Based on most recent genetic studies, the clade unites a variety of bird groups, including the australavians (passerines, parrots, seriemas, and falcons) as well as the afroavians (including the Accipitrimorphae – eagles, hawks, buzzards, vultures etc. – owls and woodpeckers, among others).

^which. guessing on that its recent genetic thing. and that i did guess vultures and it didnt connect them as related. im assuming metazooa just doesnt yet reflected the relation!

#some shit#wifi at the zoo#I WILL. continue to talk about the metazooa WITHOUT knowing what family. genus. clade. and etc means. btw. sorry.#they are just points of relation that branch out to me. sorry. i didnt take bio i took chem.#only think i know about is pundit sqaures cause im friends with funny ppl who like horses

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Titanis walleri

By Scott Reid

Etymology: Titan

First Described By: Brodkorb, 1963

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Australaves, Cariamiformes, Phorusrhacoidea, Phorusrhacidae, Phorusrhacinae

Status: Extinct

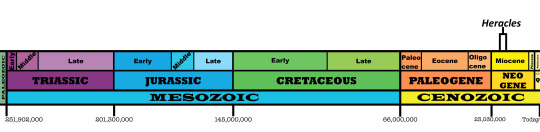

Time and Place: Between 5 and 1.8 million years ago, from the Zanclean to the Gelasian ages of the Pliocene through Pleistocene

Titanis is known from the Santa Fe River and Nueces River Formations of Florida and Texas

Physical Description: Titanis was a Terror Bird, one of the largest known Terror Birds, a group of large flightless predatory birds that terrorized the Americas during the Cenozoic Era, right up until humans would have appeared on the scene. Titanis is one of the latest members of this group, and the one that made the journey up to North America - most Terror Birds are from South America. It would have been 2.5 meters tall - much taller than a person - and would have weighed 150 kilograms. There was a lot of variance in size and height, however, indicating that Titanis may have had at least some sexual dimorphism. It had a short tail and round body, with long and powerful legs. In fact, it also had very robust toes - and one of the strongest middle toes known for a Terror Bird. It had very small, useless wings, that were very much locked in against the body - they didn’t have a lot of folding power compared to other birds. This indicates the wings really were… useless. They didn’t use them for raptor prey restraint or anything else, making them distinctly different from the Dromaeosaurids of long past. Titanis had a very thick neck, which would have supported a large head with a very impressive and terrifying hooked bill - complete with extensive crunching power!

By Dmitry Bogdanov, CC BY-SA 3.0

Diet: As a Terror Bird, Titanis primarily ate large mammals - and some medium and small sized mammals, of course, but basically it was able to cronch anything around it.

Behavior: Terror Birds are most closely related to modern Seriemas, and so a lot of their behavior has been guessed based on Seriemas today. As such - and given that it didn’t have much in the way of wings - Titanis probably mainly relied on its feet in kicking its prey to death. It would chase its food down, kick it, and potentially pin it down. Then, final death blows would have been delivered with the powerful cronch of its beak, though of course the hook on the beak would have allowed increased tearing and shredding. While modern Seriemas are solitary, it is possible that Titanis and other Terror Birds may have used groups to take down larger prey, though they probably would have been more groups of convenience than formal packs. It is possible they had similar breeding habits to living Seriemas, but even that is a question - their larger size, different niche, and general different time periods would provide large differences. And we don’t even know the actual breeding habits of Seriemas very well! So, that being said, Titanis would have probably been fairly territorial over their nests, and both parents were probably involved in the care of the nest and then the young, even after fledging. The young would follow the parents around until reaching maturity. As such, it’s possible that the parents may have hunted for the young, and brought food back for them until they were old enough to hunt for themselves. Then, upon leaving the parents, they probably would have been fairly solitary until finding a mate of their own.

By José Carlos Cortés

Ecosystem: Titanis primarily lived in open grassland habitats in the southern parts of the United States, clearly extending from Texas through to Florida and probably found all over that range. It stuck to warmer, probably wetter habitats, though the exact environments it lived in aren’t very well studied in terms of general flora. Fauna, however, is well known. Titanis lived alongside a wide variety of other animals - in Citrus County, it was found with a variety of frogs, turtles, lizards, rabbits, horses, shrews, bears, dogs, mustelids, and cats (including Smilodon), armadillos, sloths, the Mastodon, cows, peccaries, camels, and deer. There were, of course, many dinosaurs as well - in addition to Titanis, there were waders (indicating a non-insignificant amount of water in this ecosystem, possible coastline, swamps, or lakes), vultures, pheasants, ducks, falcons, owls, pigeons (including the passenger pigeon), woodpeckers, blackbirds, corvids, sparrows, finches, flycatchers, cardinals, rails, grebes, herons, bitterns, and buzzards. Basically, a fairly typical array of North American birds! In Gilchrist County, Titanis also lived alongside similar creatures, including Smilodon, though without the Mastodon - though there was Rhynchotherium! Unfortunately, its Texan relatives aren’t well known, though it stands to reason that it would have been similar to other locations.

By Ripley Cook

Other: Titanis is one of the largest known Terror Birds, and one of the largest known ones discovered early in our understanding of Terror Birds. In fact, we knew about Titanis so early on that there are a lot of old depictions of it - including ones where it has… hands. Clawed hands. That is very much wrong and cringy, but hey, there are pictures of it! Titanis is also fascinating because of its place in Earth’s History - it is one of the (only?) known Terror Birds from North America. This occurred due to the Great American Interchange, a sort of mini-columbian exchange where North America and South America combined, leading to the mixing of animals from both continents together. The traditional narrative says that Terror Birds went extinct because sabre-toothed cats came in from North America, but this is flawed for three very big reasons: 1) there were already Sabre Toothed animals filling that niche in South America, they were just Marsupials; 2) Terror Birds stuck around for a long time after the Interchange, and 3) Terror Birds reached North America in return! So Titanis helps to showcase that Terror Birds were doing just fine during this ecological exchange. So why did it - and other Terror Birds - go extinct? Probably the Ice Age, though for now, we can’t be sure. Regardless, they went extinct… probably before people got there. There are fossils that might be Titanis from 15,000 years ago, which would indicate they were still there when people got there. Which is terrifying. And also might point to humans being the cause of their extinction. Still, that seems unlikely, and they were definitely on the decline before then - so the Ice Age seems like the most logical explanation.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Alroy, John, Ph.D. Synonymies and reidentifications of North American fossil mammals, 2002. John P. Hunter, Ohio State University, Mammalian Paleontology.

Alvarenga, H. M. F.; Höfling, E. (2003). "Systematic revision of the Phorusrhacidae (Aves: Ralliformes)". Papéis Avulsos de Zoologia. 43 (4): 55–91.

Alvarenga, H.; Jones, W.; Rinderknecht, A. (May 2010). "The youngest record of phorusrhacid birds (Aves, Phorusrhacidae) from the late Pleistocene of Uruguay". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen. 256 (2): 229–234.

Baskin, J. A. (1995). "The giant flightless bird Titanis walleri (Aves: Phorusrhacidae) from the Pleistocene coastal plain of South Texas". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 15 (4): 842–844.

Bertelli, S., L. M. Chiappe, and C. Tambussi. 2007. A new phorusrhacid (Aves: Cariamae) from the Middle Miocene of Patagonia, Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 27(2):409-419.

Brodkorb, P. (1963). "A giant flightless bird from the Pleistocene of Florida". Auk. 80 (2): 111–115.

Carroll, R. L. 1988. Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution 1-698

Chandler, R.M. (1994). "The wing of Titanis walleri (Aves: Phorusrhacidae) from the Late Blancan of Florida". Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History, Biological Sciences. 36: 175–180.

Cracraft, Joel, A review of the Bathornithidae (Aves, Gruiformes), with remarks on the relationships of the suborder Cariamae. American Museum Novitates ; no. 2326.

De Iuliis, G., and C. Cartelle. 1999. A new giant megatheriine ground sloth (Mammalia: Xenarthra: Megatheriidae) from the late Blancan to early Irvingtonian of Florida. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 127:495-515

Degrange, Federico J.; Tambussi, Claudia P.; Moreno, Karen; Witmer, Lawrence M.; Wroe, Stephen; Turvey, Samuel T. (18 August 2010). "Mechanical Analysis of Feeding Behavior in the Extinct "Terror Bird" Andalgalornis steulleti (Gruiformes: Phorusrhacidae)". PLoS ONE. 5 (8): e11856.

Ehret, D. J., and J. R. Bourque. 2011. An extinct map turtle Graptemys (Testudines, Emydidae) from the Late Pleistocene of Florida. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 31(3):575-587

Emslie, S. D. 1998. Avian community, climate, and sea-level changes in the Plio-Pleistocene of the Florida Peninsula. Ornithological Monographs (50)1-113

Emslie, S. D., and N. J. Czaplewski. 1999. Two new fossil eagles from the late Pliocene (late Blancan) of Florida and Arizona and their biogeographic implications. Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology 89:185-198.

Franz, R., and I. R. Quitmyer. 2005. A fossil and zooarchaeological history of the gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus) in the Southeastern United States. Bull. Fla. Mus. Nat. History 45(4):179-199.

Gibbons, J. W., and M. E. Dorcas. 2004. North American Watersnakes: A Natural History. 1-438.

Gould, G.C. & Quitmyer, I.R. (2005). "Titanis walleri: bones of contention". Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History. 45: 201–229.

Hulbert, R. C. 1995. Equus from Leisey Shell Pit 1A and other Irvingtonian localities from Florida. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History 37(17):553-602.

Hulbert, R. C. 2010. A new early Pleistocene tapir (Mammalia: Perissodactyla) from Florida, with a review of Blancan tapirs from around the state. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History 49(3):67-126.

MacFadden, Bruce J.; Labs-Hochstein, Joann; Hulbert, Richard C.; Baskin, Jon A. (2007). "Revised age of the late Neogene terror bird (Titanis) in North America during the Great American Interchange". Geology. 35 (2): 123–126.

Marsh, O. C. (1875). "On the Odontornithes, or birds with teeth". American Journal of Science. 10 (12): 403–408.

Mayr, G. 2009. Paleogene Fossil Birds. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

Mayr, G. 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance. Topics in Paleobiology, Wiley Blackwell. West Sussex.

McDonald, H. G. 1995. Gravigrade xenarthrans from the early Pleistocene Leisey Shell Pit 1A, Hillsborough County, Florida. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History 37(11).

Meachen, J. A. 2005. A new species of Hemiauchenia (Artiodactyla, Camelidae) from the late Blancan of Florida. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History 45(4):435-447.

Meylan, P. 2001. Late Pliocene anurans from Inglis 1A, Citrus County, Florida. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History 45(4):171-178.

McFadden, B.; Labs-Hochstein, J.; Hulbert, Jr., R. C.; Baskin, J. A. (2006). "Refined age of the late Neogene terror bird (Titanis) from Florida and Texas using rare earth elements". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (3): 92A (Supplement).

Morgan, G. S., and R. B. Ridgway. 1987. Late Pliocene (late Blancan) vertebrates from the St. Petersburg Times site, Pinellas County, Florida, with a brief review of Florida Blancan faunas. Papers in Florida Paleontology 1:1-22.

Morgan, G. S. 1991. Neotropical Chiroptera from the Pliocene and Pleistocene of Florida. In T. A. Griffiths, D. Klingener, (eds.), Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 206:176-213.

Morgan, G. S., and R. C. Hulbert. 1995. Overview of the geology and vertebrate biochronology of the Leisey Shell Pit Local Fauna, Hillsborough County, Florida. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History 37(1).

Morgan, G. S., and J. A. White. 1995. Small mammals (Insectivora, Lagomorpha, and Rodentia) from the early Pleistocene (early Irvingtonian) Leisey Shell Pit Local Fauna, Hillsborough County, Florida. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History 37(13).

Robertson, J. S. 1976. Latest Pliocene mammals from Haile XV A, Alachua County, Florida. Bulletin of the Florida State Museum 20(3):1-186.

Ruez, D. R. 2001. Early Irvingtonian (latest Pliocene) rodents from Inglis 1C, Citrus County, Florida. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 21(1):153-171.

Tambussi, Claudia P.; de Mendoza, Ricardo; Degrange, Federico J.; Picasso, Mariana B.; Evans, Alistair Robert (25 May 2012). "Flexibility along the Neck of the Neogene Terror Bird Andalgalornis steulleti (Aves Phorusrhacidae)". PLoS ONE. 7 (5): e37701.

Tedford, R. H., X. Wang, and B. E. Taylor. 2009. Phylogenetic Systematics of the North American Fossil Caninae (Carnivora: Canidae). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 325:1-218.

Webb, S. D. 1974. Chronology of Florida Pleistocene mammals. In S. D. Webb (ed.), Pleistocene Mammals of Florida 5-31.

Webb, S. D., and K. T. Wilkins. 1984. Historical Biogeography of Florida Pleistocene Mammals. In H. H. Genoways and M. R. Dawson (eds.), Carnegie Museum of Natural History Special Publication 8:370-383.

White, J. A. 1991. A new Sylvilagus (Mammalia: Lagomorpha) from the Blancan (Pliocene) and Irvingtonian (Pleistocene) of Florida. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 11(2):243-246.

#Titanis walleri#Titanis#Bird#Terror Bird#Dinosaur#Dinosaurs#Raptor#Bird of Prey#Birds#Palaeoblr#Birblr#Factfile#Australavian#Cariamiform#Theropod Thursday#North America#Neogene#Quaternary#Carnivore#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

471 notes

·

View notes

Text

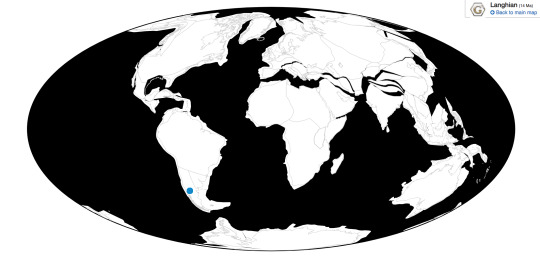

Heracles inexpectatus

By Scott Reid

Etymology: For the Greek Demigod Heracles

First Described By: Worthy et al., 2019

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Australaves, Eufalconimorphae, Psittacopasserae, Psittaciformes, Strigopoidea

Status: Extinct

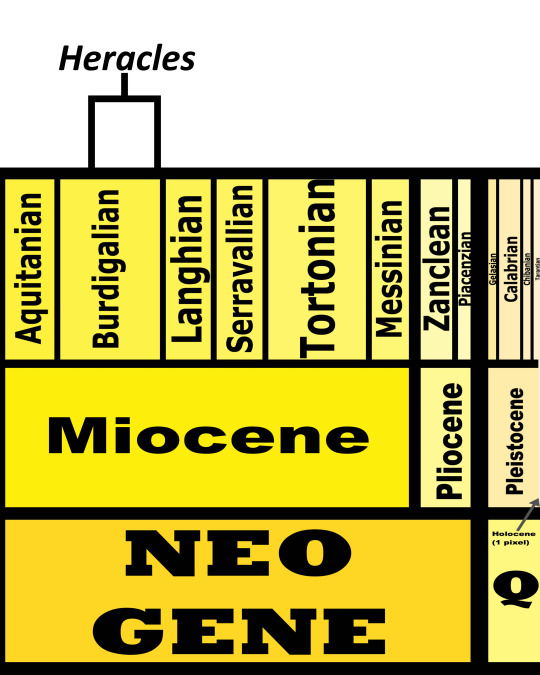

Time and Place: Between 19 and 16 million years ago, in the Burdigalian of the Miocene

Heracles is known from the Bannockburn Formation of the South Island of New Zealand

Physical Description: Heracles is an utterly fascinating recent dinosaur discovery, both for its inherent qualities and those due to the circumstances of its discovery. This was a large, Kākāpō-like parrot, about the height of a shorter adult or a child. It is the largest known parrot, and it would have been about one meter tall and weighing about seven kilograms. Given this size, it was flightless, and probably mostly terrestrial. It had a very strong beak, and probably resembled in many ways a giant version of the modern-day Kākāpō, Kaka, and Kea. As such, it would have been quite fat looking, probably greenish in color, and very fluffy as well.

By Brian Choo, Press Release Image

Diet: As a parrot, Heracles is most likely to have fed on seeds and nuts, though the fact that it was closely related to the living Kea means there is a non insignificant chance it was carnivorous. For now, we’ll say it was most likely an omnivore.

Behavior: It is logical to presume that Heracles resembled its modern relatives, which means it would have been a loosely social animal, spending most of its time on the ground in groups of about a dozen animals. It would have been able to use tools to get at sources of food, especially difficult to reach ones. It possibly would have also used its sharp beak to attack other dinosaurs on the island, chasing them with a hopping gait until they were isolated and then killed. An intelligent animal, it would have been able to solve puzzles and work together to get at sources of food or shelter. As a member of the New Zealand Parrot Group, it probably would have been polygamous, with the males having multiple mates at a time. They would have made nests on the ground, and since they never came across with mammalian predators, they probably would have been fine in terms of reproduction rate.

By Ripley Cook

Ecosystem: The Saint Bathans Fauna was a unique ecosystem filled with almost entirely birds, and other creatures that could float or fly over to New Zealand after it emerged from having flooded. This meant that birds were filling niches that, in the rest of the world, were being taken up by mammals. In short, this was a weird sort of Jurassic Park - with dinosaurs wreaking havoc as echoes of their former reign. Dinosaurs of the Saint Bathans Fauna included another New Zealand Parrot, Nelepsittacus, a bittern Pikaihao, herons like Matuku and Pikaihao, the swimming flamingo Palaelodus, flightless rails such as Priscaweka and Litorallus, the early Adzebill Aptornis proasciarostratus, the pigeon Rupephaps, the stiff-tailed duck Dunstanneta, the early Kiwi Proapteryx, the small Manuherikia duck, and the early New Zealand Wren Kuiornis - just to name a few! Given that only sparse remains are known from some unnamed birds of prey, this points to Heracles being at least somewhat carnivorous and fulfilling that role in its ecosystem. This was a series of extensive lakes, filled with cycad and palm trees, and there were also a wide variety of geckos, skinks, crocodilians, turtles, tuatara, and bats. There was one other mammal present - but, for now, we have no idea what it was.

By José Carlos Cortés

Other: The Saint Bathans Fauna is one of the most fascinating ecosystems of fossil birds of the Cenozoic Era. The unique ecosystem of New Zealand, with its almost complete lack of mammals before human interference. Heracles is an extremely important fossil find, as it may help us to piece together how the weird New Zealand Parrots evolved - previously, little was known in the way of fossil members of this group beyond recent history. The more we research it, the more we will be able to understand one small piece of the evolutionary puzzle that is this unique island. Also, it’s common name is Squawkzilla.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Mather, Ellen K.; Tennyson, Alan J. D.; Scofield, R. Paul; Pietri, Vanesa L. De; Hand, Suzanne J.; Archer, Michael; Handley, Warren D.; Worthy, Trevor H. (2019-03-04). “Flightless rails (Aves: Rallidae) from the early Miocene St Bathans Fauna, Otago, New Zealand”. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 17 (5): 423–449.

Scofield, R. Paul; Worthy, Trevor H. & Tennyson, Alan J.D. (2010). “A heron (Aves: Ardeidae) from the Early Miocene St Bathans Fauna of southern New Zealand.” (PDF). In W.E. Boles & T.H. Worthy. (eds.). Proceedings of the VII International Meeting of the Society of Avian Paleontology and Evolution. Records of the Australian Museum. 62. pp. 89–104.

Tennyson, Alan J. D.; Worthy, Trevor H.; Scofield, R. Paul (2010). “A heron (Aves: Ardeidae) from the Early Miocene St Bathans fauna of southern New Zealand. In Proceedings of the VII International Meeting of the Society of Avian Paleontology and Evolution, ed. W.E. Boles and T.H. Worthy”. Records of the Australian Museum. 62: 89–104.

Worthy, Trevor H.; Lee, Michael S. Y. (2008). “Affinities of Miocene Waterfowl (anatidae: Manuherikia, Dunstanetta and Miotadorna) from the St Bathans Fauna, New Zealand”. Palaeontology. 51 (3): 677–708.

Worthy, Trevor H.; Tennyson, Alan J. D.; Hand, Suzanne J.; Scofield, R. Paul (2008-06-01). “A new species of the diving duck Manuherikia and evidence for geese (Aves: Anatidae: Anserinae) in the St Bathans Fauna (Early Miocene), New Zealand”. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 38 (2): 97–114.

Worthy, T. H., S. J. Hand, M. Archer, R. P. Scofield, and V. L. De Pietri. 2019. Evidence for a giant parrot from the Early Miocene of New Zealand. Biology Letters 15:20190467

#Heracles#heracles inexpectatus#Parrot#New Zealand Parrot#Dinosaur#Dinosaurs#Birds#Bird#palaeoblr#birblr#psittaciformes#Australavian#factfile#Terrestrial Tuesday#Omnivore#Australia & Oceania#Neogene

248 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nymphicus hollandicus

By Jim Bendon, CC BY-SA 2.0

Etymology: Nymph Birds

First Described By: Wagler, 1832

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Australaves, Eufalconimorphae, Psittacopasserae, Psittaciformes, Cacatuoidea, Nymphicinae

Status: Extant, Least Concern

Time and Place: Within the last 10,000 years, in the Holocene of the Quaternary

Cockatiels are originally known from the bulk of Australia

Physical Description: Cockatiels are medium sized birds, ranging between 29 and 33 centimeters in total body length. Wild Cockatiels are grey all over their bodies, with white patches on their wings. The males have bright yellow heads with orange cheek patches, and long yellow crests of feathers coming off of the tops of their heads. The females are usually more grey in the head region, with a duller orange cheek patch, and a grey crest. They have extremely long tail feathers and very large, broad wings. They usually weigh between 80 and 100 grams. Semi-domesticated individuals of this species can come in a wide variety of color morphs that are based on the wild-type colors, but not exactly the same: some will be yellow-ish all over, some will be entirely white; some will lack the orange cheek patches and have grey or white heads; some will be more spottled, and so on. There are an estimated 22 color mutations in cockatiels, with many being very distinctively different. In general, males are more brightly patterned than females, and have bigger crests; there are exceptions to this rule, of course, all over the color spectrum.

By Ben Cordia, CC BY-SA 4.0

Diet: In the wild, Cockatiels feed mainly on seeds and grain, especially from crops and native fields and plains, where grass seeds are fed upon. In captivity, Cockatiels should be fed a varied diet of pellets, fresh vegetables, whole grains, some fruit, and the occasional seed for treats.

By Jim Bendon, CC BY-SA 2.0

Behavior: Cockatiels in the wild will feed twice a day by foraging on the ground, scurrying about in a waddling fashion to look for the seeds and grains they prefair. Large flocks of tens to hundreds or even thousands of birds will gather depending on how much food is available in any given spot, and are occasionally joined by budgies at especially fertile lands. Their waddle walk is offset by the fact that they are extraordinarily powerful fliers, able to move very fast and powerfully with rapid flaps of their wings, using the tail to steer. They will migrate nomadically, following the presence of seeds and - thus - usually following rain patterns. Because they follow water, they oftentimes will reach the coast in their migrations. At night, they will sleep in available trees, perched in branches with no real preference as to what sort of tree they sleep in.

BY Jim Bendon, CC BY-SA 2.0

Cockatiels are extraordinarily loud birds, making a variety of calls to one another to ensure that the flock stays together. To just chirp at each other, they’ll make sort of yipping calls as they go about their day. When a member of the flock is lost, they will scream extremely loudly to find them again, calling out “EEP” at the top of their lungs until the flock member is located. While flirting, they will unfurl their wings ever so slightly, forming a heart shape; sticking their neck out, they will perform a flirtatious call (which can vary somewhat) at the object of their affections. They often bob their heads and bodies while doing this. Sometimes they’ll practice their singing into the air, and will hold up one of their feet to do so, singing at it like they’re holding a microphone. They will extend their crest out all the way while curious, and cluck while exploring a specific environment. When alarmed, their body will go extremely taught, their neck stuck out all the way; if danger is present, they’ll fly away quickly and make very loud sounds to the rest of the flock to promote everyone escaping from the situation.

By Jim Bendon, CC BY-SA 2.0

In the wild, cockatiels breed usually in the late autumn or winter, nesting within tree hollows. They are very protective of their nesting sites and will scream at any intruders. They can form lifelong pairs or be polygamous in terms of breeding behavior. Both sexes will protect the eggs and bring each other food; the clutches are usually one to seven eggs in size, and are incubated for twenty days. The chicks are usually very naked with some yellow down, and are largely altricial; they will stay protected for five weeks and are guarded by the parents. They then mature and become part of the nomadic flocks, sticking close to their family members for the first month or so. Cockatiels reach sexual maturity at around 1 year old, and full skeletal maturity at 2 years. They can live up to 25 years on average, though many individuals have reached past 30 years of age with proper care.

By Meig Dickson

Ecosystem: In the wild, Cockatiels live in arid and semi-arid open habitats such as savanna, scrubland, open woodland, grassland, and more outback habitats. They will stay close to sources of water but do not need them as much as other parrots; and they are often found associated with extensive cropland and farms. They are usually not found in the most fertile and wet corners of Australia, or the deepest parts of the Australian desert, or the Cape York Peninsula.

By Meig Dickson

Other: Cockatiels are some of the most common birds in Australia, with an estimated population of around one million individuals; this, plus them showing no real drops in population, makes them not vulnerable to extinction at this time. They are occasionally regarded as pests, especially by farmers. However, the main interaction humans have with Cockatiels is via aviculture.

By Meig Dickson

Cockatiels are the second most popular pet parrot after budgies, and one of the most common pet caged birds out there. While individuals are occasionally imported from Australia from time to time, most Cockatiels sold or adopted at this point are descended from many generations of breeding programs. Breeding efforts have turned pet cockatiels into nearly domesticated animals, inhabiting that weird grey area between tame and domestication. As such, at-home species have different colors and behaviors. They tend to trust humans more, especially when they are hand-fed by their breeders. They are extremely intelligent animals and are able to learn tricks. They require extensive space, toys, and out-of-cage time to live happy lives, and need a varied diet to avoid biological problems such as fatty liver disease. Though not an easy companion animal to own by any stretch of the imagination, cockatiels (and budgies) are well on their way to being truly domesticated, rather than just an exotic animal that’s at home in human spaces. Extremely social animals, they do best with other members of their species in a large cage, rather than being alone in a smaller space. Cockatiels are kept entirely for companionship; they are not bred for any other purpose, though with their powerful and agile flight style they may be shown off in bird shows.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Adams, M; Baverstock, PR; Saunders, DA; Schodde, R; Smith, GT (1984). "Biochemical systematics of the Australian cockatoos (Psittaciformes: Cacatuinae)". Australian Journal of Zoology. 32 (3): 363–77.

Astuti, Dwi (2011). "Phylogenetic relationships within Cockatoos (Aves: Psittaciformes) Based on DNA Sequences of The Seventh intron of Nuclear β-fibrinogen gene" (PDF). Jurnal Biologi Indonesia. 7 (1): 1–11.

Rowley, I. & Kirwan, G.M. (2019). Cockatiel (Nymphicus hollandicus). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Flegg, Jim (2002): Photographic Field Guide: Birds of Australia. Reed New Holland, Sydney & London.

Martin, Terry (2002). A Guide To Colour Mutations and Genetics in Parrots. ABK Publications.

#Nymphicus#nymphicus hollandicus#Cockatiel#Bird#Dinosaur#Parrot#Cockatoo#Birds#Dinosaurs#factfile#Birblr#Australavian#Flying Friday#Quaternary#Australia & Oceania#Granivore#a-dinosaur-a-day#a dinosaur a day#dinosaur of the day#science#nature#biology#aviculture

340 notes

·

View notes

Text

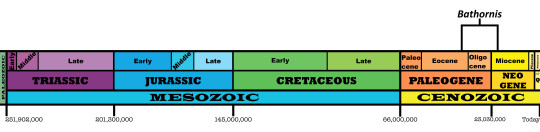

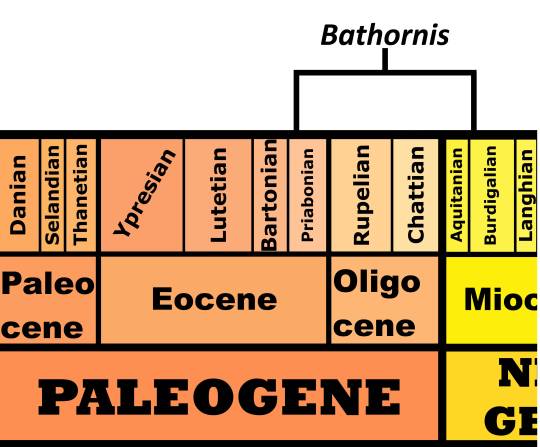

Bathornis

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: Tall Bird

First Described by: Wetmore, 1927

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Australaves, Cariamiformes, Bathornithidae

Referred Species: B. celeripes, B. cursor, B. fax, B. fricki, B. geographicus, B. grallator, B. minor, B. veredus

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: From 37 to 20 million years ago, between the Priabonian of the Eocene of the Paleogene and the Burdigalian of the Miocene of the Neogene

Bathornis is known from a very wide number of formations - which makes sense, given how many species have been referred to the genus. Bathornis is known from the Chadron Formation, the Brule Formation, the Willow Creek Site (not Formation, that’s from the Cretaceous because people keep reusing names), the Washakie Formation, and the Willwood Formation - and it is possible that it is also known from other locations throughout North America. It appears to have concentrated on the western half, however, being known from formations in Colorado, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Wyoming.

Physical Description: Bathornis was a large, flightless predatory dinosaur from the Cenozoic - and, despite being in the same general group of birds as they, it isn’t a terror bird! Bathornis, unlike the Terror Birds, still had decently sized wings (even though they couldn’t be used in flight) and, more importantly, it had a well-developed hind toe, whereas the Terror Birds had reduced hind toes. Still, it was doing essentially the same thing, but in North America. It had long, thin legs, built well for running; a squat body; small-ish wings; reduced musculature in the shoulder and chest area; large heads, and long, sharp beaks. These beaks weren’t as tall as those found in the Terror Birds, but that didn’t take away from their ability to pack a devastating bite. The variety of species ranged widely in size, with some as short as 60 centimeters, and some as tall as 2 meters (though it is possible the smaller species were just juveniles).

By Julio Lacerda

Diet: Bathornis was a terrestrial carnivore, able to utilize its large beak to grab and crush large prey - even large mammals. It is even possible that in many environments, Bathornis was one of the primary large predators, similar to the Terror Birds of the south.

Behavior: Bathornis, being a very large terrestrial predator, would have spent a good portion of its time on the move. Its long, strong legs were good for running, as well as probably kicking. Not being able to fly, they would have relied on their legs to get around and chase prey. Powerful kicks of the legs would have aided Bathornis in killing its prey, however, it would have primarily relied upon its beak to deliver the final blows. The powerful crushing action of the beak would have allowed it to break apart extremely tough prey, potentially even crushing bone. It may have still used its wings in some flapping action to aid in hunting, though it doesn’t seem likely it used them as much as the earlier terrestrial raptors of the Mesozoic era. Being a predator, it doesn’t seem likely that Bathornis was very social; modern Seriemas hunt primarily alone, and there’s no evidence Bathornis did otherwise. Still, it probably did care for its young in some capacity.

By Nix, CC BY-NC 4.0

Ecosystem: Bathornis is known from a variety of ecosystems across Northwestern America in the Cenozoic Era; it seems, however, it favored wetlands to open savanna and grassland. It may have also been found in more sparse woodland. This means that, while it was fast, running great distances across open habitat wasn’t its usual activity. It may have even used its long legs to aid in wading through the water towards sources of food. That doesn’t mean it never inhabited open areas, of course - just that it probably preferred bogs and swamps to prairies. Bathornis often lived alongside large mammals, including large mammalian predators such as Haenodonts, Entelodonts, and Nimravids. Odd-toed ungulates like Megacerops and Merycoidodon were often found closely associated with Bathornis, indicating that they were common sources of prey for this dinosaur. It also was often found with its close relative, Paracrax, which would have been direct competition for it. Many other dinosaurs are known to have lived alongside Bathornis, more than I can reasonably list; but it probably encountered the fowl Procrax, the flighted predator birds Phasmagyps and Palaeoplancus, the tody Palaeotodus, the flighted ratites Lithornis and Paracathartes, the large herbivorous bird Gastornis, the flightless wading birds Geranoides and Palaeophasianus, the owl Eostrix, the mousebirds Anneavis and Eobucco, and the Sandcoleid sandcoleus. It’s interesting that Bathornis quite probably encountered Gastornis, given that Gastornis used to be thought to have Bathornis’ job, and is now known to have been a similarly-sized large herbivore instead.

By José Carlos Cortés

Other: Bathornis was very closely related to the contemporaneous (but Southern) Terror Birds, but it actually evolved for the same niche independently. This happened all over their group of dinosaurs, the Cariamiformes (Seriemas and their many, many extinct relatives). This indicates that the long-legged terrestrial predatory lifestyle of the Seriema group made them especially prone to growing larger, and losing their flight capabilities. The common nature of Bathornis and its relatives in the Northern Hemisphere is also important biogeographically. Many think that the Terror Birds went extinct due to the influx of large mammal predators after North and South America combined. However, Bathornis lived alongside these North American Large Mammals - and even thrived in its environment. So, clearly, large avian predators and large mammalian predators were perfectly capable of coexisting. So why did Bathornis - and then, later, their southern Terror Bird cousins - go extinct? Jury is, sadly, still out.

By Scott Reid

Species Differences: There are a wide variety of species of Bathornis, though some may not be the same species, and it is entirely possible that these animals shouldn’t be grouped under one genus from a phylogenetic standpoint. B. veredus is known from the Eocene and Oligocene of the Chadron Formation, and was about the size of a living emu. B. cursor is different from B. veredus primarily because of differences in the ankle, and it was slightly larger and earlier in time. B. geographicus is known from South Dakota, Nebraska, and Wyoming, and it may be a descendant of B. veredus; it was larger than both veredus and cursor, and it is possibly the largest species in the genus. B. fax is the smallest species known, but it also lived with B. veredus and is probably just the juvenile form. B. celeripes is known from the end of the Oligocene, and it was about the same size as B. cursor, so a mid-sized species of the genus. B. fricki is from the Early Miocene, making it one of the youngest species of all; it may have been a direct descendant of B. celeripes, to which it was very similar. B. minor lived in the same time and place as B. fricki, and they differ due to small changes in the leg bones. B. grallator, finally, is the best known form; coming from the Eocene, it was originally called Neocathartes before being combined into Bathornis by Mayr in 2016. It was originally thought to be flighted, but further research has shown it was also flightless. It was actually first thought to be a vulture! Life is funny like that.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Angolin, F. L. 2009. Sistemática y Filogenia de las Aves Fororracoides (Gruiformes, Cariamae). Fundación de Historia Natural Felix de Azara: 1 - 79.

Benton, R. C., D. O. Terry, E. Evanoff, H. G. McDonald. 2015. The White River Badlands: Geology and Paleontology. Indiana University Press.

Carroll, R. L. 1988. Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution 1-698

Cracraft, J. 1968. A review of the Bathornithidae (Aves, Gruiformes) with remarks on the relationships of the suborder Cariamae. American Museum Novitates 2326: 1 - 46.

Cracraft, J. 1971. Systematics and evolution of the Gruiformes (Class Aves). 2, Additional comments on the Bathornithidae, with descriptions of new species. American Museum Novitates 2449: 1 - 14.

Galbreath, E. C. 1953. A contribution to the Tertiary geology and paleontology of northeastern Colorado. University of Kansas Paleontological Contributions Vertebrata 4:1-120.

Lambrecht, K. 1933. Handbuch der Palaeornithologie. 1-1024

Mayr, G. 2009. Paleogene Fossil Birds. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

Mayr, G., J. Noriega. 2013. A well-preserved partial skeleton of the poorly known early Miocene seriema Noriegavis santacrucensis (Aves, Cariamidae). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica.

Mayr, G. 2016. Osteology and phylogenetic affinities of the middle Eocene North American Bathornis grallator - one of the best represented, albeit least known Paleogene cariamiform birds (seriemas and allies). Journal of Paleontology 90 (2): 357 - 374.

Mayr, G. 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance. Topics in Paleobiology, Wiley Blackwell. West Sussex.

Olson, S. L. 1985. Farner, D. S., ed. The Fossil Record of Birds, section X. A. I. b. The Tangle of the Bathornithidae. Avian Biology 8. New York: Academic Press. 146 - 150.

Wetmore, A. 1927. Fossil birds from the Oligocene of Colordao. Proceedings of the Colorado Museum of Natural History 7 (2): 1 - 14.

Wetmore, A. 1944. A new terrestrial vulture from the Upper Eocene deposits of Wyoming. Annals of the Carnegie Museum 30: 57 - 69.

Wetmore, Alexander (1950). "A Correction in the Generic Name for Eocathartes grallator". Auk. 67 (2): 235.

#Bathornis#Bird#Dinosaur#Australavian#Prehistoric Life#Paleontology#Prehistory#Palaeoblr#Birblr#Factfile#Dinosaurs#Birds#Bathornithid#Carnivore#Terrestrial Tuesday#Paleogene#Neogene#North America#Bathornis celeripes#Bathornis cursor#Bathornis fax#bathornis fricki#Bathornix geographicus#Bathornis grallator#Bathornis minor#Bathornis veredus#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day

218 notes

·

View notes

Text

Herpetotheres cachinnans

By Ken Erickson, in the Public Domain

Etymology: Reptile Hunter

First Described By: Vieillot, 1817

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Australaves, Eufalconimorphae, Falconiformes, Falconidae, Falconinae

Status: Extant, Least Concern

Time and Place: Since 10,000 years ago, in the Holocene of the Quaternary

The Laughing Falcon is known from Central and South America, in the Tropical regions

Physical Description: The Laughing Falcon is an odd bird of prey, with distinctive markings and a fluffy head to make it stand out from others in the Falcon group! Ranging between 45 and 53 centimeters, the females usually weigh more than the males, and they have wingspans of up to 91 centimeters in length. They wings are short and round-tipped, and they have long distinctive tails. They have large heads, with fluffy tops to the heads. The tops are white, and the necks are white, but they have a dark brown patch around the eye. Their beaks are small and yellow, with black tips. They have dark-brown backs and wings, and white bellies; their tails are dark brown with white patches. They also have small feet for birds of prey.

By Allan Sobral, CC BY-SA 4.0

Diet: Laughing Falcons feed primarily on snakes, including very large venomous ones - even rattlesnakes! They will also supplement their diet with lizards, snakes, fish, and birds.

By Andreas Trepte, CC BY-SA 4.0

Behavior: This is a very slow falcon, mainly perching noticeably in trees where they will search the ground carefully for sources of food. It will also move around the branches with slow, cautious, tiny steps. They will then fly very quickly down to the prey. Other than that they fly slowly, and rarely soar through the air. They also don’t hunt other birds, so they’re quite peaceful by falcon standards. It will pounce on its prey from flight and bite it just behind the head, then carrying it back to the perch to eat in its claws like an osprey, and then tears it to pieces. This method often beheads the snakes prior to consumption, especially when given to young.

By Félix Uribe, CC BY-SA 2.0

Laughing Falcons have extremely distinctive calls, hence their names - in fact, the cries are so weird that natives to the area will call the bird evil (though, of course, it is anything but). It makes long, far-carrying “wah wah” calls that start out bubbly and increase in pitch. Mated pairs will often create loud duets together at dawn and dusk near the nest. They will make soft laughs and “Ha has” as well, and the chicks also make little laughing sounds!

by Bernard DuPont, CC BY-SA 2.0

These birds will breed in rock crevices, tree cavities, and the abandoned nests of other birds of prey; they don’t really gather nesting material, but just use the space and a little bit of vegetation to keep the eggs nestled. They usually lay one egg, which is incubated by the female for a month and a half, while the male brings food and keeps watch. Mating and breeding can occur any time of the year, with different populations starting at different times. The chicks are small and covered in brown fluff; they’re fed by both parents, though mostly by the mother, for two months. For up to a year after leaving the nest, the young will stay with the parents and not stray too far while getting used to life in the jungle. They have very large home ranges, but do not migrate beyond that range.

Laughing Falcon by Francesco Veronesi, CC BY-SA 2.0

Ecosystem: Laughing Falcons are mainly known in tropical and subtropical rainforests, especially along forest edges and in more disturbed second-growth forest (rather than unbroken rainforest). They are also commonly found along rivers and in swamp forests.

By Francesco Veronesi, CC BY-SA 2.0

Other: Laughing Falcons are not considered threatened with extinction at this time; they range from uncommon to common throughout their range (though there are some patches with more rarity) and - while some places have seen a decline, especially in response to deforestation - they seem to remain fairly common and stable in populations in most of their range.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Becker, J. J. 1987. Revision of "Falco" ramenta Wetmore and the Neogene evolution of the Falconidae. Auk 104(2):270-276.

Bierregaard, R.O., Jr & Kirwan, G.M. (2019). Laughing Falcon (Herpetotheres cachinnans). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Cuervo, Andrés M.; Hernández-Jaramillo, Alejandro; Cortés-Herrera, José Oswaldo & Laverde, Oscar (2007): Nuevos registros de aves en la parte alta de la Serranía de las Quinchas, Magdalena medio, Colombia [New bird records from the highlands of Serranía de las Quinchas, middle Magdalena valley, Colombia]. Ornitología Colombiana 5: 94-98.

Howell, Steven N.G. & Webb, Sophie (1995): A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Central America. Oxford University Press, Oxford & New York.

Jiménez, Mariano II & Jiménez, Mariano G. (2003): El Zoológico Electrónico – El Halcón Guaicurú Herpetotheres cachinnans. Version of 2003-AUG-01. Retrieved 2007-FEB-22.

Remsen, J. V., Jr.; Cadena, C. D.; Jaramillo, A.; Nores, M.; Pacheco, J. F.; Robbins, M. B.; Schulenberg, T. S.; Stiles, F. G.; Stotz, D. F.; and Zimmer, K. J. Version (2008-12-22). A classification of the bird species of South America. American Ornithologists' Union.

Woodhouse, S.C. (1910): English-Greek Dictionary – A Vocabulary of the Attic Language. George Routledge & Sons Ltd., Broadway House, Ludgate Hill, E.C.

#Herpetotheres cachinnans#Laughing Falcon#Herpetotheres#Falcon#Dinosaur#Bird#Birds#bird of Prey#Raptor#Dinosaurs#Factfile#North America#South America#Australavian#Quaternary#Carnivore#Theropod Thursday#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

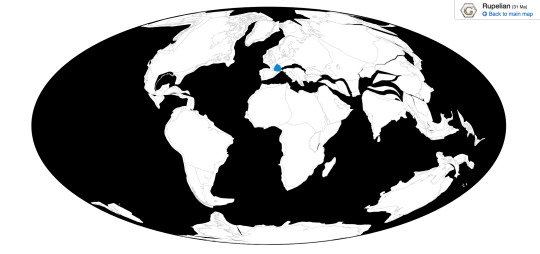

Xenopsitta fejfari

By Scott Reid

Etymology: Strange Parrot

First Described By: Mlikovsky, 1998

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Australaves, Eufalconimorphae, Psittacopasserae, Psittaciformes, Psittacoidea, Psittacidae, Psittacinae, Psittacinae

Status: Extinct

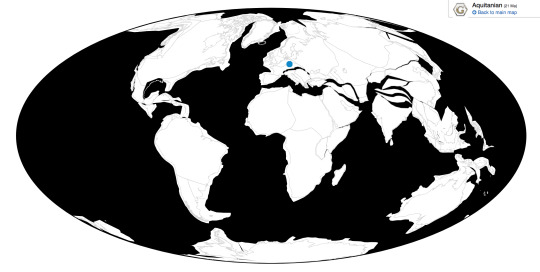

Time and Place: 22 million years ago, in the Aquitanian of the Miocene

Xenopsitta is known from the Merkur site of Cheb County in Czechia

Physical Description: Xenopsitta was a small parrot, with very robust feet similar to living African parrots. Despite this, it was probably much smaller than most of them, probably only about half the size as living African Greys or Senegal Parrots. This would mean it is probably somewhere around 16 centimeters in total body length, though that is a rough estimate. Still, in a lot of ways it was a miniature version of a living African Grey Parrot, with similarly short ligaments and strong feet. Xenopsitta also had fairly stout and short wings compared to other parrots, though not to the point of being flightless. We can’t say much more about this parrot, as it has shapes in its feet and wings similar to quite a few different kinds of parrots, though African varieties seem most likely; it would have resembled living parrots in most ways too, with a similarly large head, big and distinctive beak, and possibly colorful feathers.

Diet: As a parrot, Xenopsitta would have been mainly herbivorous, feeding on a wide variety of nuts, leaves, and fruit; though they would have probably supplemented their diet with animal matter such as insects when needed.

Behavior: It is reasonable to suppose, as a bird closely related to a very specific group of living parrots, Xenopsitta would have been an intelligent forager much like they are today, using its large and curved beak to dig around and find food, as well as to make nests in cavities it would create in trees. It would have used its flexible feet to interact extensively with its environment, reaching out to grab things and to manipulate objects. In addition, Xenopsitta would have been very social, living in decently sized flocks and family groups, and talking to each other with squawks and calls aplenty. They would have taken care of their young, probably for a decent amount of time before the young left the nest.

By Ripley Cook

Ecosystem: Xenopsitta lived in a heavily forested environment, probably sub-tropical in terms of temperature with a bit of seasonal variation. There were many types of plants present in the area, including beeches and oaks, walnuts and birches, maples and chestnuts and mangos and mahoganies, citrus, magnolias, roses, and some coniferous trees. Little is known in the way of mammals here, but there were plenty of birds - including the Swift Procypseloides, the owl Mioglaux, the cormorant Phalacrocorax, the loon Petralca, ducks like Nettion and Mionetta, and the giant swimming-flamingo Palaelodus. The present of so many water birds indicates that there was a decent system of rivers and lakes present in the area as well. As for predators, Xenopsitta probably mostly had to watch out for Mioglaux!

Other: Xenopsitta is one of many fossil parrots known from the Miocene of Europe, a location that doesn’t have natural parrots today. This showcases that parrots occurred in a wide diversity in the forests of Europe prior to the Ice Age glaciations, with many different kinds of living groups represented within the sub-continent. Furthermore, it is one of the earlier ones known, which helps to clear up some of the murkiness of parrot evolution - stem-parrots disappear from the fossil record in the Oligocene, with modern-form parrots showing up seemingly out of nowhere in the Miocene. This is then followed by a dramatic extinction of parrots and other later tropical birds from Europe, sometime in the late Miocene, from which Xenopsitta and its descendants would have been affected.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Čerňanský, A., M. Venczel. 2011. An amphisbaenid reptile (Squamata, Amphisbaenidae) from the Lower Miocene of Northwest Bohemia (MN 3, Czech Republic). Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen 260 (1): 73 - 77.

Göhlich, U. B. 2003. The avifauna of the Grund Beds (Middle Miocene, Early Badenian, northern Austria). Annalen des Naturhistorischen Museums in Wien Serie A 104:237-249.

Mayr, G., U. B. Göhlich. 2004. A new parrot from the Miocene of Germany with comments on the variation of hypotarsus morphology in some Psittaciformes. Belgium Journal of Soozology 134 (1): 47 - 54.

Mayr, G. 2010. Mousebirds (Coliiformes), parrots (Psittaciformes), and other small birds from the late Oligocene/early Miocene of the Mainz Basin, Germany. N. Jb. Geol. Paläont. Abh. 257 (2): 129 - 144.

Mayr, G. 2011. Two-phase extinction of “Southern Hemispheric” birds in the Cenozoic of Europe and hte origin of the Neotropic avifauna. Palaeobiology Palaeonevironment 91: 325 - 333.

Mayr, G. 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance. Topics in Paleobiology, Wiley Blackwell. West Sussex.

Manegold, A. 2012. Two new parrot species (Psittaciformes) from the early Pliocene of Langebaanweg, South Africa, and their palaeoecological implications. Ibis 155 (1): 127 - 139.

Mlikovsky, Jiri (1998). "A new parrot (Aves: Psittacidae) from the early Miocene of the Czech Republic". Acta Soc. Zool. Bohem. 62: 335–341.

Pavia, M. 2014. The parrots (Aves: Psittaciformes) from the Middle Miocene of Sansan (Gers, Southern France). Paläontology Z. 88: 353 - 359.

Svec, P. 1981. Lower Miocene birds from Dolnice (Cheb basin), western Bohemia, part II. Casopis pro mineralogii 26(1):43-56

Waterhouse, D. M. 2013. Parrots in a nutshell: the fossil record of Psittaciformes (Aves). Historical Biology 18 (2): 227 - 238.

Xelenkov, N. V. 2016. The first fossil parrot (Aves, Psittaciformes) from Siberia and its implications for the historical biogeography of Psittaciformes. Biology Letters 12: 20160717.

#Xenopsitta fejfari#Xenopsitta#Parrot#Dinosaur#Bird#Birds#Prehistoric Life#Paleontology#Prehistory#Dinosaurs#Birblr#Palaeoblr#Factfile#Australavian#Neogene#Flying Friday#Herbivore#Eurasia#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

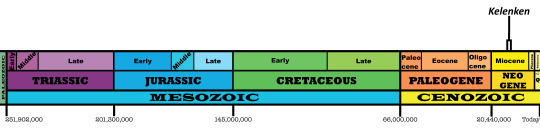

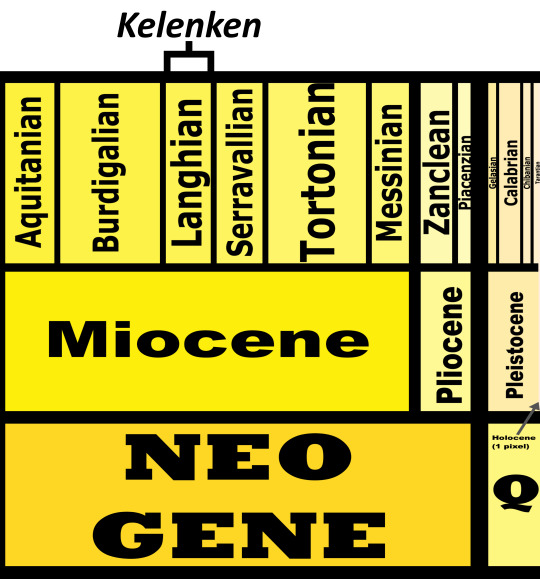

Kelenken guillermoi

By Scott Reid

Etymology: For Kélenken, the Bird of Prey Spirit of the Tehuelche Tribe

First Described By: Bertelli et al., 2007

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Australaves, Cariamiformes, Phorusrhacoidea, Phorusrhacidae, Phorusrhacinae

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Between 15.5 and 13.8 million years ago, in the Langhian age of the Miocene of the Neogene

Kelenken is known from the Collón Curá Formation of Rio Negro Province, Argentina

Physical Description: Kelenken was a Terror Bird, a type of large flightless terrestrial dinosaur from the late Cenozoic era, mostly in South America though a few reached North America when the continents collided. These were some of the top predators of their environments, built for chasing down food over long distances and then using their monstrous beaks to tear into flesh. Kelenken was one of the biggest members of the group, about two meters tall, and it had one of the largest known skulls of any bird, with fused bones to give it significant strength in its head and strong bire force. Its limbs were very robust, probably allowing for powerful movements of the legs. It had very small wings, as other Terror Birds did, and as such they probably weren’t used very much (think of the arms of Carnotaurus but the bird version). It had a long, winding neck, and its head was mostly beak. The beak was hooked at one end. It had a short tail, though we don’t have any feather impressions to know if it had any sort of feather decoration at the end of it. It would have had a huge bite force, and it possibly was a faster runner than other Terror Birds.

Diet: Kelenken primarily fed on large animals, especially faster moving ones such as hoofed mammals

Behavior: Kelenken probably spent most of its time chasing down its prey, though it’s uncertain how. It’s possible that it would chase down prey, catch it, and shatter its bones with its beak by repeatedly pecking at it (if… pecking is an accurate word to use with such a huge beak doing the pecking). It’s also possible that it would chase down smaller prey, pick it up, and shake it vigorously to break the prey’s back. It also possibly scavenged off of prey. Honestly, it seems likely that Kelenken would utilize all these strategies, and those not even come up with, to get any prey it could in an opportunistic fashion.

By Michael B. H.

Kelenken was a fairly fast animal, and probably able to run for longer distances. As its environment was transitioning to an open grassland rather than a forest, this ability to run moreso than its earlier relatives was probably a direct adaptation for that open habitat. As such, Kelenken would have been extremely alert and on the lookout, both for food and for potential dangers, as it was tall enough to poke out above the grass and be visible to anything looking for it. Kelenken could fight with others of its species and against other animals both with its beak and with its feet, as it had very robust legs that would have been good for kicking, possibly very rapid and sharp kicks.

As only a few specimens of Kelenken are known, it’s difficult to determine its social behavior, especially since its closest living relatives are the Seriemas - a much smaller sort of dinosaur. Still, it’s possible to at least glean some behavioral patterns from seriemas. It’s possible that, like living seriemas, Kelenken only spent its time in pairs and small groups, which may have worked together cooperatively to take down larger mammalian sources of prey. It’s also possible that it may have been territorial over its nests, with breeding pairs avoiding other Kelenken and fighting with those they come across. This is all speculative, but would make sense given the environment and size of the animals. Kelenken, being a bird, almost decidedly took care of its young, though we cannot know if both parents took care of the young as in modern Seriemas, or if only one parent did the job at a time as in modern flightless birds. More fossils might be able to clear up this picture, though of course, it’s possible we’ll never know.

By Ripley Cook

Ecosystem: Kelenken lived in the part of the Miocene that was the hottest, called the Middle Miocene Climatic Optimum. This was immediately followed by drastic cooling. Thus, Kelenken lived in a uniquely warm period of the time in which Terror Birds dwelled. The formation was surrounded by extensive rivers and lakes, as basins formed in South America due to tectonic plates separating. This environment was a growing grassland, with the pampa overtaking the old deciduous forest that had once been there.

Kelenken is the only dinosaur known from the formation, but there were many different types of mammals present. There were the heavy-bodied hoofed mammals Protypotherium, Epipatriarchus, and Interatherium; the smaller hoofed mammals Hegetotherium and Pachyrukhos; the weird fast hoofed mammal related to Macrauchenia, Theosodon; armadillo relatives such as Proeutataus, Paraeucinepeltus, Peltephilus, Prozaedyus, and Stenotatus; the anteater relative Neotamandua; the rodents Galileomys, Guiomys, Maruchito, Microcardiodon, Neosteiromys, Protacaremys, Acarechimys, Alloiomys, Megastus, Neoreomys, Prolagostomus, and Stichomys; the new-world monkey Proteropithecia; the sabre-toothed marsupial Patagosmilus; and the extinct shrew opossum relative Abderites. There were also reptiles such as boa relatives like Waincophis, lizards, and turtles like Chelonoidis. There was also the horned frog Wawelia.

Kelenken probably would have hunted a variety of these things, especially the hoofed mammals, though some would have been too big for it to eat. It definitely would have been in direct competition with Patagosmilus, which probably would have specialized on different prey than Kelenken.

Other: Kelenken is most closely related to phorusrhacids such as Phorusrhacos and Titanis, two of the other more famous genera in this group.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Abello, María Alejandra, and David Rubilar Rogers. 2012. Revisión del género Abderites Ameghino, 1887 (Marsupialia, Paucituberculata). Ameghiniana 49. 164–184. Accessed 2019-02-15.

Albino, A.M. 1996. Snakes from the Miocene of Patagonia (Argentina) Part I: The Booidea. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen 199. 417–434. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Angolin, F. L., P. Chafrat. 2015. New fossil bird remains from the Chinchinales Formation (Early Miocene) of Northern Patagonia, Argentina. Annales de Paleontologie 101: 87 - 94.

Baez, A. M., S. Peri. 1990. Revision de Wawelia gerholdi, un anuro del Mioceno de Patagonia. Ameghiniana 27(3-4):379-386

Bertelli, S., L. M. Chiappe, C. Tambussi. 2007. A new phorusrhacid (Aves: Cariamae) from the middle Miocene of Patagonia, Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 27(2): 409 - 419.

Bondesio, P.; J. Rabassa; R. Pascual; M.G. Vucetich, and G.J. Scillato Yané. 1980. La formación Collón-Curá de Pilcaniyeú Viejo y sus alrededores (Río Negro, República Argentina) su antiguedad y las condiciones ambientales según su distribución su litogenesis y sus vertebrados. Actas del Segundo Congreso Argentino de Paleontología y Bioestratigrafía y Primer Congreso Latinoamericano de Paleontología 3. 85–99.

De Broin, F., and M. De la Fuente. 1993. Les tortues fossiles d'Argentine: synthese (The fossil turtles of Argentina: synthesis). Annales de Paléontologie (Invertebrés-Vertebrés) 79. 169–232. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Forasiepi, A.M., and A.A. Carlini. 2010. A new thylacosmilid (Mammalia, Metatheria, Sparassodonta) from the Miocene of Patagonia, Argentina. Zootaxa 2552. 55–68. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Gonzaga, L. P., A. Bonan. 2017. Seriemas (Cariamidae). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

González Ruiz, Laureano Raúl; Flavio Góis; Martín Ricardo Ciancio, and Gustavo Juan Scillato Yané. 2013. Los Peltephilidae (Mammalia, Xenarthra) de la Formación Collón Curá (Colloncurense, Mioceno Medio), Argentina. Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia 16. 319–330. Accessed 2019-02-27.

González Ruiz, Laureano Raúl; Alfredo Eduardo Zurita; Gustavo Juan Scillato Yané; Martín Zamorano, and Marcelo Fabián Tejedor. 2011. Un nuevo Glyptodontidae (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Cingulata) del Mioceno de Patagonia (Argentina) y comentarios acerca de la sistemática de los gliptodontes "friasenses". Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas 28. 566–579. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Kay, R.F.; D. Johnson, and J. Meldrum. 1998. A new Pitheciin Primate from the Middle Miocene. American Journal of Primatology 45. 317–336. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Kramarz, Alejandro; Alberto Garrido; Analía Forasiepi; Mariano Bond, and Claudia Tambussi. 2005. Estratigrafia y vertebrados (Aves y Mammalia) de la Formación Cerro Bandera, Mioceno Temprano de la Provincia del Neuquén, Argentina. Revista Geológica de Chile 32. 273–291. Accessed 2017-10-20.

McDonald, H.G.; S.F. Vizcaíno, and M.S. Bargo. 2008. Skeletal anatomy and the fossil history of the Vermilingua, 64–78. S. F. Vizcaíno, W. J. Loughry (eds.), The Biology of the Xenarthra. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Náñez, Carolina, and Norberto Malumián. 2019. Foraminíferos miocenos en la cuenca Neuquina, Argentina: implicancias estratigráficas y paleoambientales. Andean Geology 46. 183–210. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Oriozabala, C.; J. Sterli, and L. González Ruiz. 2018. Morphology of the mid-sized tortoises (Testudines: Testudinidae) from the Middle Miocene of Northwestern Chubut. Ameghiniana 55. 30–54. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Pardiñas, U.F.J. 1991. Primer registro de primates y otros vertebrados para la Formacion Collón Curá (Mioceno medio) del Neuquén, Argentina (First record of primates and other vertebrates from the Collón Curá Formation (middle Miocene) of Neuquén, Argentina). Ameghiniana 28. 197–199. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Pearson, Paul N., and Martin R. Palmer. 2000. Atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations over the past 60 million years. Nature 406. 695–699. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Pérez, M.E., and M.G. Vucetich. 2011. A new Extinct Genus of Cavioidea (Rodentia, Hystricognathi) from the Miocene of Patagonia (Argentina) and the Evolution of Cavoid Mandibular Morphology. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 18. 163–183. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Pérez, M.E.. 2010. A new rodent (Cavioidea, Hystricognathi) from the middle Miocene of Patagonia, mandibular homologies, and the origin of the crown group Cavioidea sensu stricto. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30. 1848–1859. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Rehr, D. 2007. Prehistoric Predators - Terror Bird. 5:40 - 11:40. National Geographic.

Silvestro, Daniele; Marcelo F. Tejedor; Martha L. Serrano Serrano; Oriane Loiseau; Victor Rossier; Jonathan Rolland; Alexander Zizka; Alexandre Antonelli, and Nicolas Salamin. 2017. Evolutionary history of New World monkeys revealed by molecular and fossil data. BioRxiv _. 1–32. Accessed 2017-09-24.

Tambussi, C. P. 2011. Palaeoenvironmental and faunal inferences based on the avian fossil record of Patagonia and Pampa: what works and what does not. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 103: 458 - 474.

Vera Nardoni, Bárbara; Marcelo Reguero, and Laureano González Ruiz. 2017. The Interatheriinae notoungulates from the middle Miocene Collón Curá Formation in Argentina. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 62. 845–863. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Vucetich, M.G., and A.G. Kramarz. 2003. New Miocene rodents from Patagonia (Argentina) and their bearing on the early radiation of the Octodontoids (Hystricognathi). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 23. 435–444. Accessed 2019-02-27.

Vucetich, M.G.; M.M. Mazzoni, and U.F.J. Pardiñas. 1993. Los roedores de la Formación Collón Curá (Mioceno Medio), y la ignimbrita Pilcaniyeú, Cañadón del Tordillo, Neuquén. Ameghiniana 30. 361–381. Accessed 2019-02-27.

#kelenken#kelenken guillermoi#terror bird#bird#dinosaur#birds#dinosaurs#birblr#palaeoblr#neogene#south america#carnivore#terrestrial tuesday#australavian#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#factfile#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

311 notes

·

View notes

Text

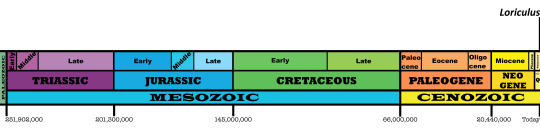

Loriculus

Sri-Lankan Hanging Parrot by Hafiz Issadeen, CC BY 2.0

Etymology: Lory

First Described By: Blythe, 1849

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Australaves, Eufalconimorphae, Psittacopasserae, Psittaciformes, Psittacoidea, Psittaculidae, Agapornithinae

Referred Species: L. amabilis (Moluccan Hanging Parrot), L. aurantiiforns (Orange-Fronted Hanging Parrot), L. beryllinus (Sri Lanka Hanging Parrot), L. catamene (Sangihe Hanging Parrot), L. camiguinensis (Camiguin Hanging Parrot), L. exilis (Pygmy Hanging Parrot), L. flosculus (Wallace’s Hanging Parrot), L. galgulus (Blue-Crowned Hanging Parrot), L. philippensis (Philippine Hanging Parrot), L. pusillus (Yellow-Throated Hanging Parrot, L. sclateri (Sula Hanging Parrot), L. stigmatus (Great Hanging Parrot), L. tener (Bismarck Hanging Parrot), L. vernalis (Vernal Hanging Parrot)

Status: Extant, Endangered - Least Concern

Time and Place: Within the last 10,000 years, in the Holocene of the Quaternary

The Hanging Parrots are known entirely from Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands

Physical Description: The Hanging Parrots are small, green parrots, ranging from 10 to 15 centimeters in length - essentially the same size as their close relatives, the Lovebirds. As parrots, they have small bodies, short tails, feet with two toes pointing forward and two backward, big heads, and strongly curved beaks. Also, as parrots, they are very intelligent and social creatures. These birds are green in general, with a variety of different patches of color on their heads, wings, and tails to distinguish them and look fancy for other hanging parrots. These colors are usually reds, oranges, and yellows; though at least a few have blue patches as well. These birds are usually sexually dimorphic, with the females having fewer patches of bright color than the males.

Diet: Flowers, fruits, nectar, and seeds from a variety of tropical trees.

Vernal Hanging Parrot by Raj Dhage, CC BY-SA 4.0

Behavior: These birds are notable from the fact that they hang down in trees and from other high surfaces, often upside down, to reach sources of food in the trees. They are also unique amongst parrots in not only foraging upside down, but also sleeping upside down - they’ll hang, more passively, from branches in order to sleep. This gives them a rather fruity look themselves - like they’re ripe for the harvest, and it’s perfectly adorable. These parrots range from being very social - living in large flocks - to being almost solitary, only ever foraging in pairs during the breeding season and alone during the off season. Very few of these birds will ever go back to the ground, but rather spend all of their time in trees.

These birds make a wide variety of calls, such as tzeet-tzeet-tzeet, squeaky warbles, and twitters. Overall, however, they’re not quite as vocal as other kinds of parrot. Though no species undertakes large-scale migrations, they are somewhat nomadic, moving from tree to tree in search of food, and sometimes going up and down mountains based on food availability.

Sulawesi Hanging Parrot by A.S. Kono, CC BY-SA 3.0

The Hanging Parrots generally begin breeding all throughout the year, based on the species - some will start their breeding season in September, others in January, and so on. It really depend son the parrot. They’ll place their nests in holes of bamboo and in tree trunks, anywhere they can keep it relatively high off of the ground. They usually lay only two eggs per breeding season, though at least a few species will lay up to three. They incubate the eggs for about three weeks, and the nestlings stay in the nest for five weeks.

Ecosystem: The Hanging Parrots live in tropical rainforest, throughout the forest itself - some species will be found in denser forests, others in the secondary growth, others at the edge, as well as in peatswamps, near rivers, in patches of bamboo, and mangrove forests. They usually live at lower elevations, though some will migrate to higher parts of the mountains in search of food. They rarely come down from the trees, and spend most of their time at least a few meters off of the ground. Some are also found in tropical dry forests.

Blue Crowned Hanging Parrot by Kee Yap, CC BY-SA 2.0

Other: These birds are mostly conservationally doing alright, except for some endangerment due to habitat loss. As rainforests and other tropical forests fragment, the Hanging Parrots lose range and ability to contact other parrots, making their populations more vulnerable. Still, only a few species have shown a marked decline in population. At least one parrot, the Camiguin Hanging-Parrot, is rarely ever found. These birds are not good pet parrots, given a wide number of requirements in captivity; however, they are still subject to the illegal pet trade, much to the chagrin of their vulnerable populations.

Species Differences: The Moluccan Hanging-Parrot has a bright red cap on its head and a bright red tail; it mainly lives on the island of Maluku. The Orange-Fronted Hanging Parrot has the same patterns as the Moluccan Hanging Parrot, except it is orange instead of red; it starts breeding in September, and lives in New Guinea. The Sri Lankan Hanging Parrot has an orange top of the head, brown back, and a blue patch on the throat; it begins breeding in January, and lives mainly in Sri Lanka. The Sangihe Hanging Parrot looks very similar to the Moluccan Hanging Parrot, but instead lives in Sulawesi and is a more yellowish green. The Camiguin hanging Parrot is a lighter green, with a light blue patch on its face; it breeds in September, and is known only from the island of Camiguin. The Pygmy Hanging Parrot is the smallest of them all, and only has a red patch on its neck; they breed in February, and live in Sulawesi.

Sri Lanka Hanging Parrot by Thimindu, CC BY-SA 3.0

The Flores Hanging Parrot has red patches on its back, and lives in Java. The Blue-Crowned Hanging Parrot has a distinctive blue patch on its head; it starts breeding in January, and lives throughout Indonesia and Southeast Asia. The Philippine Hanging Parrot has green and yellow orange patches all over, lives in the Philippines, and breeds in March or September. The Yellow-Throated Hanging Parrot has a bright yellow patch on its throat, breeds in April, and lives in Java. The Sula Hanging Parrot has an orange back and lives in Sulawesi. The Sulawesi Hanging Parrot is a lighter green with a brown back, and a red head patch; it breeds in January and April, and lives in Sulawesi. The Bismark Hanging Parrot is a more yellow green with a small red patch on its throat, and lives on the island of New Britain. Finally, the Vernal Hanging Parrot has a light blue throat patch, breeds in January, and lives throughout Southeast Asia and in some patches of the Indian Subcontinent.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut