#Bathornithid

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

New #Palaeontology short on the diet of the large, flightless bird Gastornis

youtube

#prehistoriclife#prehistoric#prehistory#fossil#nature#Gastornis#Eocene#birds#Paleogene#didyouknow#isotopes#Phorusrhacos#Bathornithids#birds of prey#europe#north america#Asia#Youtube#Palaeontology

0 notes

Text

spectember: Day 2 Heir

With the cataclysmic end of the era of the great alioramids, each continent of makai had a theropod that climbed to the top, on the plains of the continent of Gna'kai oviraptors analogous to bathornithids began to exchange the skies for the land, their descendants would one day become the sophont known as katel.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bathornis

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: Tall Bird

First Described by: Wetmore, 1927

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Australaves, Cariamiformes, Bathornithidae

Referred Species: B. celeripes, B. cursor, B. fax, B. fricki, B. geographicus, B. grallator, B. minor, B. veredus

Status: Extinct

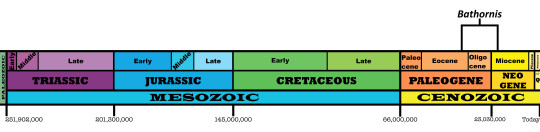

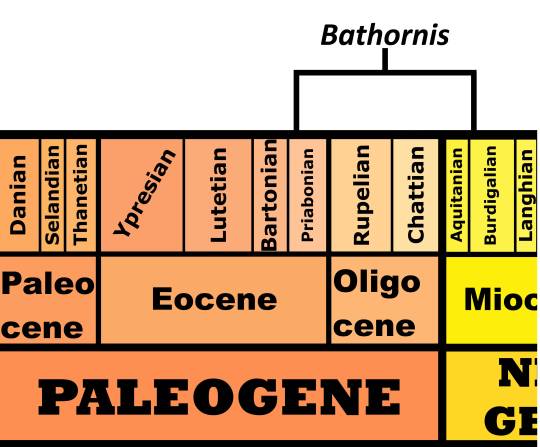

Time and Place: From 37 to 20 million years ago, between the Priabonian of the Eocene of the Paleogene and the Burdigalian of the Miocene of the Neogene

Bathornis is known from a very wide number of formations - which makes sense, given how many species have been referred to the genus. Bathornis is known from the Chadron Formation, the Brule Formation, the Willow Creek Site (not Formation, that’s from the Cretaceous because people keep reusing names), the Washakie Formation, and the Willwood Formation - and it is possible that it is also known from other locations throughout North America. It appears to have concentrated on the western half, however, being known from formations in Colorado, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Wyoming.

Physical Description: Bathornis was a large, flightless predatory dinosaur from the Cenozoic - and, despite being in the same general group of birds as they, it isn’t a terror bird! Bathornis, unlike the Terror Birds, still had decently sized wings (even though they couldn’t be used in flight) and, more importantly, it had a well-developed hind toe, whereas the Terror Birds had reduced hind toes. Still, it was doing essentially the same thing, but in North America. It had long, thin legs, built well for running; a squat body; small-ish wings; reduced musculature in the shoulder and chest area; large heads, and long, sharp beaks. These beaks weren’t as tall as those found in the Terror Birds, but that didn’t take away from their ability to pack a devastating bite. The variety of species ranged widely in size, with some as short as 60 centimeters, and some as tall as 2 meters (though it is possible the smaller species were just juveniles).

By Julio Lacerda

Diet: Bathornis was a terrestrial carnivore, able to utilize its large beak to grab and crush large prey - even large mammals. It is even possible that in many environments, Bathornis was one of the primary large predators, similar to the Terror Birds of the south.

Behavior: Bathornis, being a very large terrestrial predator, would have spent a good portion of its time on the move. Its long, strong legs were good for running, as well as probably kicking. Not being able to fly, they would have relied on their legs to get around and chase prey. Powerful kicks of the legs would have aided Bathornis in killing its prey, however, it would have primarily relied upon its beak to deliver the final blows. The powerful crushing action of the beak would have allowed it to break apart extremely tough prey, potentially even crushing bone. It may have still used its wings in some flapping action to aid in hunting, though it doesn’t seem likely it used them as much as the earlier terrestrial raptors of the Mesozoic era. Being a predator, it doesn’t seem likely that Bathornis was very social; modern Seriemas hunt primarily alone, and there’s no evidence Bathornis did otherwise. Still, it probably did care for its young in some capacity.

By Nix, CC BY-NC 4.0

Ecosystem: Bathornis is known from a variety of ecosystems across Northwestern America in the Cenozoic Era; it seems, however, it favored wetlands to open savanna and grassland. It may have also been found in more sparse woodland. This means that, while it was fast, running great distances across open habitat wasn’t its usual activity. It may have even used its long legs to aid in wading through the water towards sources of food. That doesn’t mean it never inhabited open areas, of course - just that it probably preferred bogs and swamps to prairies. Bathornis often lived alongside large mammals, including large mammalian predators such as Haenodonts, Entelodonts, and Nimravids. Odd-toed ungulates like Megacerops and Merycoidodon were often found closely associated with Bathornis, indicating that they were common sources of prey for this dinosaur. It also was often found with its close relative, Paracrax, which would have been direct competition for it. Many other dinosaurs are known to have lived alongside Bathornis, more than I can reasonably list; but it probably encountered the fowl Procrax, the flighted predator birds Phasmagyps and Palaeoplancus, the tody Palaeotodus, the flighted ratites Lithornis and Paracathartes, the large herbivorous bird Gastornis, the flightless wading birds Geranoides and Palaeophasianus, the owl Eostrix, the mousebirds Anneavis and Eobucco, and the Sandcoleid sandcoleus. It’s interesting that Bathornis quite probably encountered Gastornis, given that Gastornis used to be thought to have Bathornis’ job, and is now known to have been a similarly-sized large herbivore instead.

By José Carlos Cortés

Other: Bathornis was very closely related to the contemporaneous (but Southern) Terror Birds, but it actually evolved for the same niche independently. This happened all over their group of dinosaurs, the Cariamiformes (Seriemas and their many, many extinct relatives). This indicates that the long-legged terrestrial predatory lifestyle of the Seriema group made them especially prone to growing larger, and losing their flight capabilities. The common nature of Bathornis and its relatives in the Northern Hemisphere is also important biogeographically. Many think that the Terror Birds went extinct due to the influx of large mammal predators after North and South America combined. However, Bathornis lived alongside these North American Large Mammals - and even thrived in its environment. So, clearly, large avian predators and large mammalian predators were perfectly capable of coexisting. So why did Bathornis - and then, later, their southern Terror Bird cousins - go extinct? Jury is, sadly, still out.

By Scott Reid

Species Differences: There are a wide variety of species of Bathornis, though some may not be the same species, and it is entirely possible that these animals shouldn’t be grouped under one genus from a phylogenetic standpoint. B. veredus is known from the Eocene and Oligocene of the Chadron Formation, and was about the size of a living emu. B. cursor is different from B. veredus primarily because of differences in the ankle, and it was slightly larger and earlier in time. B. geographicus is known from South Dakota, Nebraska, and Wyoming, and it may be a descendant of B. veredus; it was larger than both veredus and cursor, and it is possibly the largest species in the genus. B. fax is the smallest species known, but it also lived with B. veredus and is probably just the juvenile form. B. celeripes is known from the end of the Oligocene, and it was about the same size as B. cursor, so a mid-sized species of the genus. B. fricki is from the Early Miocene, making it one of the youngest species of all; it may have been a direct descendant of B. celeripes, to which it was very similar. B. minor lived in the same time and place as B. fricki, and they differ due to small changes in the leg bones. B. grallator, finally, is the best known form; coming from the Eocene, it was originally called Neocathartes before being combined into Bathornis by Mayr in 2016. It was originally thought to be flighted, but further research has shown it was also flightless. It was actually first thought to be a vulture! Life is funny like that.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Angolin, F. L. 2009. Sistemática y Filogenia de las Aves Fororracoides (Gruiformes, Cariamae). Fundación de Historia Natural Felix de Azara: 1 - 79.

Benton, R. C., D. O. Terry, E. Evanoff, H. G. McDonald. 2015. The White River Badlands: Geology and Paleontology. Indiana University Press.

Carroll, R. L. 1988. Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution 1-698

Cracraft, J. 1968. A review of the Bathornithidae (Aves, Gruiformes) with remarks on the relationships of the suborder Cariamae. American Museum Novitates 2326: 1 - 46.

Cracraft, J. 1971. Systematics and evolution of the Gruiformes (Class Aves). 2, Additional comments on the Bathornithidae, with descriptions of new species. American Museum Novitates 2449: 1 - 14.

Galbreath, E. C. 1953. A contribution to the Tertiary geology and paleontology of northeastern Colorado. University of Kansas Paleontological Contributions Vertebrata 4:1-120.

Lambrecht, K. 1933. Handbuch der Palaeornithologie. 1-1024

Mayr, G. 2009. Paleogene Fossil Birds. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

Mayr, G., J. Noriega. 2013. A well-preserved partial skeleton of the poorly known early Miocene seriema Noriegavis santacrucensis (Aves, Cariamidae). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica.

Mayr, G. 2016. Osteology and phylogenetic affinities of the middle Eocene North American Bathornis grallator - one of the best represented, albeit least known Paleogene cariamiform birds (seriemas and allies). Journal of Paleontology 90 (2): 357 - 374.

Mayr, G. 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance. Topics in Paleobiology, Wiley Blackwell. West Sussex.

Olson, S. L. 1985. Farner, D. S., ed. The Fossil Record of Birds, section X. A. I. b. The Tangle of the Bathornithidae. Avian Biology 8. New York: Academic Press. 146 - 150.

Wetmore, A. 1927. Fossil birds from the Oligocene of Colordao. Proceedings of the Colorado Museum of Natural History 7 (2): 1 - 14.

Wetmore, A. 1944. A new terrestrial vulture from the Upper Eocene deposits of Wyoming. Annals of the Carnegie Museum 30: 57 - 69.

Wetmore, Alexander (1950). "A Correction in the Generic Name for Eocathartes grallator". Auk. 67 (2): 235.

#Bathornis#Bird#Dinosaur#Australavian#Prehistoric Life#Paleontology#Prehistory#Palaeoblr#Birblr#Factfile#Dinosaurs#Birds#Bathornithid#Carnivore#Terrestrial Tuesday#Paleogene#Neogene#North America#Bathornis celeripes#Bathornis cursor#Bathornis fax#bathornis fricki#Bathornix geographicus#Bathornis grallator#Bathornis minor#Bathornis veredus#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day

218 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Many modern predatory birds have enlarged claws on their second toes, similar to those of their paravian dinosaur ancestors – with seriemas being a particularly good example.

Seriemas are part of a lineage known as cariamiformes, highly terrestrial birds that were widespread across most of the world but are today represented today by only two living species in South America. During the Cenozoic this group repeatedly evolved into large predatory flightless forms like the the phorusrhacids and bathornithids, and were probably the closest avians ever got to recreating the "carnivorous theropod" body plan and ecological niche.

And yet none of them ever seem to have experimented with more dromaeosaurid-like claws.

…With one known exception.

Qianshanornis rapax here lived in East China during the mid-Paleocene, about 63 million years ago. It was a small cariamiform, probably around 30cm tall (1"), and is only known from fragmentary fossil material – but part of those fragments was a fairly well-preserved foot. And the bones of its second toe were unlike any other known Cenozoic bird, shaped incredibly similarly to those of dromaeosaurids and suggesting it may have had the same sort of big hyperextendible "sickle claw".

While it had sturdy legs and short wings, and probably spent a lot of time walking on the ground like other cariamiformes, it was probably also still a fairly strong flier based on the known anatomy of its arms and shoulders.

Unfortunately, though, its head and claws were entirely missing, so without more fossil discoveries it's hard to say anything definite about its ecology. I've restored it here based on other predatory cariamiformes, but since it was also closely related to a herbivorous species it's not clear whether Qianshanornis was truly a dromaeosaur-mimic or if something else was going on with that unique second toe.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Pillowfort | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#qianshanornis#cariamiformes#bird#dinosaur#art#convergent evolution#actual pointy birbs

513 notes

·

View notes

Note

Had an idea for a WWB reboot: Paleocene episode in NA with Taeniolabis and other multies, Eocene episode in Turkey with Necromantis ("Killer Bat"), Oligocene midwest episode with nimravids and bathornithids, Miocene episode in Australia, Pliocene episode in Antarctica and Pleistocene episode in Vietnam with Palaeoloxodon namadicus

Have fun with that.

0 notes

Text

Eremopezus eocaenus

By José Carlos Cortés on @quetzalcuetzpalin-art

PLEASE SUPPORT US ON PATREON. EACH and EVERY DONATION helps to keep this blog running! Any amount, even ONE DOLLAR is APPRECIATED! IF YOU ENJOY THIS CONTENT, please CONSIDER DONATING!

Name: Eremopezus eocaenus

Status: Extinct

First Described: 1904

Described By: Andrews

Classification: Dinosauria, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Palaeognathae, Eremopezidae

What is Eremopezus? A mystery. It is probably from the Jebel Qatrani Formation of Egypt, living about 30.2 - 29.5 million years ago, in the Rupelian age of the Oligocene of the Paleogene (it was once thought that this formation dated to the Eocene, but it has since been re-dated). This formation is notable for the significant number of transitional mammal and bird forms - between the early members of groups known from the Eocene and the close to modern forms from the Neogene. Eremopezus is mysterious both for its age - which makes finding its phylogenetic affinities more difficult than if it were, say, younger and more similar to modern forms - and its incompleteness - it is only known from very limited material of the leg, discovered in two batches, one at the beginning of the 1900s and the other more recently. It was originally considered to be a ratite - but it may, in fact, not be a ratite at all. Eremopezus has a lot of traits that actually aren’t found in ratites at all, but are unique or found in other birds (ie, the Neognaths - the group containing literally all other birds). In fact, it has similar traits to modern Secretarybirds and Shoebill, which are both from Africa as well (though it’s probably not related to either). Still, recent analyses have grouped it with the Elephant Birds - but the jury remains out.

By Jack Wood on @thewoodparable

It is entirely possible that Eremopezus is actually its own distinct lineage of ratite - since almost all ratites evolved flightlessness independently (apart from emu and cassowary which are very closely related), Since most ancestors of ratites and modern ratites are mainly known from recent fossil records, this marks a very early experiment in ratite-like body plan and lifestyle amongst Palaeognaths (given that most large flightless birds of the Paleogene were actually from other bird groups - see Gastornis and the early Terror Birds and Bathornithids). This would also make it a very unique and convergent sort of Paleognath, having evolved traits similar to other bird groups independently. Eremopezus was probably about the size of a modern large rhea or small emu, though it had very robust foot bones that would have been able to support a heavier body than those of the rhea. It probably stood as tall as a person. As such, it probably was flightless, though of course it is difficult to determine that without further fossils and it is possible that it could fly. Its toes flared out from the foot like that of a Cassowary, allowing for the weight to be supported over a larger surface area. The toes would also have been bulkily padded, allowing for the toes to be very flexible and mobile, so it moved around on foot a lot regardless of its flight status and may have used its feet for other activities.

By Scott Reid on @drawingwithdinosaurs

Eremopezus lived in the Jebel Qatrani Formation, an environment of freshwater rivers and shallow low-lying lakes near the Tethys Sea. It was a very tropical environment with monsoon seasons and swamps, and while reed grasses that characterize Egypt today were present, they were much rarer. Many mammals were present including Creodonts and Anthracotheriids, two types of completely extinct mammal lineages that looked like squat felines and elongated hippos respectively; an ancient primate, some shrews and hyraxes and even a marsupial. When it comes to birds, there was a relative of the shoebill, a relative of storks, a relative of herons, as well as cormorants, jacanas, and turacos. There were also crocodilians, gharials, snakes, and turtles. In this environment, it is likely that Eremopezus was some sort of herbivore, even a fruit eater, though without actual fossils of the head or gut contents we can’t know for sure. It may have gone extinct due to habitat turnover as grasses began to spread further in Africa.

Source:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eremopezus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jebel_Qatrani_Formation

#eremopezus#eremopezus eocaenus#bird#dinosaur#birblr#palaeoblr#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature#factfile#Dìneasar#דינוזאור#डायनासोर#ديناصور#ডাইনোসর#risaeðla#ڈایناسور#deinosor#恐龍#恐龙#динозавр#dinosaurio

62 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bathornis grallator, a flightless bird about 75cm tall (2′6″) from the Late Eocene and Early Oligocene of Midwestern USA (~37-34 mya).

It was originally mistaken for a long-legged vulture (under the name Neocathartes) when first discovered in the 1940s, but later studies have shown it was actually one of the smaller members of the bathornithids -- close cousins of the more well-known South American “terror birds”, successfully occupying terrestrial predator niches alongside large carnivorous mammals.

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#bathornis#bathornithidae#neocathartes#cariamae#cariamiformes#bird#art#terror bird#sort of#terror birds. terror birds everywhere.

661 notes

·

View notes

Link

I highly recommend having this survey open on your browser, doing research, and filling it out slowly. Because, birds.

Palaeognaths

The first major division of modern birds (all the rest are Neognaths). Includes the Moa, Elephant Birds, Tinamous, Emus, Rheas, and Lithornithids. Casuarias and Struthio are ineligible, so don’t write in any Cassowaries or Ostriches.

Highlights include the Kiwi, an adorable small with a long snoot; Aepyornis, the largest Neornithean known; the Emu, who has one of the funniest ways of running; and Lithornis, an extinct flying member of the group.

Galloanserans

The earliest derived group of Neognaths. Includes Gastornis & the very similar Dromornithids, Geese, Screamers, Ducks, Swans, Curassows, Guans, Megapodes, Partridges, Quails, Junglefowl, and Pheasants. Genera Pavo and Gallus are ineligible, so don’t write in any peafowl or the four junglefowl under Gallus (which includes the chicken).

Highlights include Gastornis, which was actually a large herbivore rather than a super predator as thought; Vegavis, one of the earliest well-known Neornithes, being from the Cretaceous; Hooded Merganser, the duck with the very large crest that is quite impressive; and the Blue-billed Curassow, confirmed Friend and Curly Man.

Caprimulgiformes & Opisthocomiformes

These two groups aren’t actually closely related, I just had to stick Opisthocomiformes somewhere. Caprimulgiformes include Oilbirds, Owlet-Nightjars, Frogmouths, Nighthawks, and Nightjars. Opisthocomiformes include Hoatzin. Genera Nyctibius and Opisthocomus are ineligible, so no potoos or the only modern Hoatzin.

Highlights include the Satanic Nightjar, which looks exactly like you’d expect; the Tawny Frogmouth, who almost looks like a potoo if you squint; the Oilbird, which has some of the weirdest and spookiest eyes; and Hoazinoides, an extinct Hoatzin with feet like that of an owl.

Apodiformes

Swifts, Treeswifts, and Hummingbirds. Nothing is ineligible. All are precious.

Highlights include the Bee Hummingbird, the smallest dinosaur known to science; the Common Swift, which looks like a boomerang; Eocypselus, an early relative of all these groups; and anything of the genera Sappho and Lesbia, which are the best genus names I’ve ever heard of.

Columbaves

Cuckoos, Turacos, Bustards, Pigeons, Doves, Sandgrouse, and Mesites. Genus Columba is ineligible, so don’t write in any of the “typical pigeons.”

Highlights include the Dodo, which is not as dumb as we were lead to believe; the Bare-Faced Go-Away Bird, which represents Me at All Times; the Nicobar Pigeon, which has beautiful rainbow plumage; and the Kori Bustard, which has a really elegant neck and posture IMO.

Gruiformes

Cranes, Crakes, Rails, Limpkin, Trumpeters, Flufftails, Finfoots, and Sungrebes. Nothing is ineligible.

Highlights include the Whooping Crane, an endangered species with a distinctive call; the White-Spotted Flufftail, who has adorable spots on its butt; the Red-Legged Crake, which is red in lots of places besides its legs; and the Sungrebe, which has a nice blue cap on its head.

Mirandornithes & Charadriiformes

Flamingos, Grebes, Waders, Snipes, Sandpipers, Jacanas, Wanderers, Gulls, Skimmers, Terns, Puffins, Skuas, Plovers, Buttonquails, Thick-Knees, Sheathbills, Ibisbills, Avocets, Oystercatchers, and Lapwings. Nothing is ineligible.

Highlights include the Great Auk, an extinct large puffin that we as humans don’t deserve; the Ring-Billed Gull, whom I have a personal vendetta against; the Dovekie, a smol, adorable friend; and the Sanderling, one of the inspirations behind Pixar’s Piper.

Ardeae

Tropicbirds, Kagu, Sunbittern, Loons, Albatross, Petrels, Storkss, Boobies, Cormorants, Pelicans, Hamerkop, Ibises, Spoonbills, Herons, Egrets, and Penguins. The genus Balaeniceps is ineligible, so don’t write in the Shoebill.

Highlights include the Little Penguin, the smol adorable penguin of smol adorableness; the Least Bittern, who is indeed the Least Bittern; the Common Loon, against whom my partner Max (@plokool) has a personal vendetta; and the Emperor Penguin, which is the Pinnacle of Dinosaurian Evolution according to Thomas Holtz (well, okay, he said penguins in general were, but this is the emperor penguin, so...)

Accipitrimorphs

Vultures (both Old and New world), Ospreys, Hawks, Eagles, Kites. Genera Sagittarius and Gypaetus are ineligible, so don’t write in the Secretary Bird, or the Bearded Vulture. No, do not write in the Bearded Vulture, nor Lammergeier, nor Ossifrage. You will have wasted your vote. Do not do the thing. It doesn’t count.

Highlights include Haast’s Eagle, an eagle so large it hunted the Moa; the Harpy Eagle, which honestly when you see it if you aren’t convinced birds are dinosaurs there’s nothing more I can do; the Turkey Vulture, or as I like to call it, the Bare-Faced Come-Hither Bird; and the Red-Tailed Hawk, aka, that sound you hear when people try to ignore that Bald Eagles are actually huge dorks.

Strigiformes

Owls. Genus Tyto is ineligible, which is basically all barn owls and most of their close relatives, so just, don’t write that in.

Highlights include Palaeoglaux, one of the earliest derived forms and may have been diurnal; the Burrowing Owl, who likes to dig them holes; the Snowy Owl, aka Hedwig; and the Fearful Owl, who looks exactly like what you’d expect.

Coraciimorphs

Mousebirds, Cuckoo Roller, Trogons, Hornbills, Hoopoes, Rollers, Kingfishers, Woodpeckers, Toucans. Genus Dacelo is ineligible, which means no Kookaburras, none, do not write one in.

Highlights include Septencoracias, aka a Friend and Boy; the Hoopoe, aka the Most Jewish bird; the Resplendent Quetzal, which truly is magnificently colored; and the Keel-Billed Toucan, who just really loves fruit okay?

Falconiformes & Cariamiformes

Serimas, Terror Birds, Bathornithids, Caracaras, and Falcons. Genus Titanis is ineligible, as is Falco peregrinus, the peregrine falcon. Since most falcons are under Falco, the rest of the genus is eligible.

Highlights Include Phorusrhacos, one of the most Quintessential Terror Birds; the Red-Legged Seriema, who is just a very angry bird; the Pygmy Falcon, who is a Smol Ball of FURY; and the Northern Crested Caracara, who has distinctive purple-pinkish skin on its face.

Parrots

... Parrots. The Kakapo, genus Strigops, is ineligible.

Highlights include the Cockatiel, a common pet and soft friend; the African Grey Parrot, one of the smartest species of dinosaurs; Spix’s Macaw, a beautiful blue parrot on the brink of extinction; and the Mulga Parrot, a parrot with feathers that almost look like clay in certain lighting.

Passerines

Perching birds. The vast majority of birds. Most birds are in this group. I am so sorry. Includes, but is not limited to, Pittas, Broadbills, Cotingas, Sharpbills, Flycatchers, Antthrushes, Ovenbirds, Lyrebirds, Scrub-birds, Bowerbirds, Honeyeaters, Fairywrens, Whistlers, Orioles, Vireos, Birds of Paradise, Jays, Satinbirds, Wattlebirds, Rockfowl, Tits, Chickadees, Larks, Nicators, Wren-Babblers, Swallows, Warblers, Babblers, Waxwings, Treecreepers, Thrushes, Oxpeckers, Mockingbirds, Sugarbirds, Sunbirds, Sparrows, Finches, Buntings, Cardinals, Whistlers, Woodshrikes.

The genus Corvus is ineligible, which is a good portion of crows and ravens, so don’t write them in. There are so many passerines to choose from, you can pick another one.

It’s, nearly impossible to pick four highlights, but here we go. Highlights include the Blue Jay, one of the most famous and beautiful perching birds; the Superb Bird of Paradise, who has one of the most spectacular mating dances of birds; the Great Tit, who truly is an amazing soft sphere of birb; and the House Sparrow, a feature of almost every major city and one of the dinosaurs often used to define the clade.

Good luck. Have fun. Voting will close February 24 (possibly earlier if we get enough votes in).

#birds#dinosaurs#dinosaur march madness#dmm2017#palaeoblr#birblr#neornithes#this is Insanity#I am so sorry#maybe one year we should just have it be only birds#the Bird Year#an entire quadrant would be passerines#John and I came up with an idea to make this easier next year and I hope it works

209 notes

·

View notes