#eremopezus

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Fossil Novembirb: Day 15 - Oasis in the Desert

During the Late Eocene and Early Oligocene, the environment of Jebel Qatrani formation of Faiyum, Egypt was as lush as you could imagine, with tropical forests, and a vast system of wetlands, lakes and rivers connecting to the warm Tethys Sea. As you would expect, such a place was teeming with birds. The birds living here would have no idea that 30 million years later, the Sahara desert would bury all this greenery. But for now, it is an oasis where birds of a feather flock together.

Goliathia: One of the earliest known relatives of the shoebill, arguably one of the most awesome birds alive today.

Nycticorax: An early member of the modern night-heron genus. It is not named, but can be assigned to the genus thanks to the shape of its limb bones.

Xenerodiops: An early member of the stork family with a short, recurved beak. It probably fed like modern wood storks, probing the water with the beak open, snapping it shut on passing fish.

Nuphranassa: A member of the modern jacana group, but much larger than any living species at about the size of a chicken.

Janipes: Another large jacana. Not as large as Nuphranassa, but still larger than any modern jacana. One must wonder what these guys were walking on.

Palaeoephippiorhynchus: An early stork well known from this period. It closely resembles the saddle-billed and black-necked storks, but was markedly smaller in size.

Eremopezus: A very poorly know flightless palaeognath known from a few fragmentary limb bones. Probably related to modern ostriches.

#Fossil Novembirb#Novembirb#Dinovember#birblr#palaeoblr#Birds#Dinosaurs#Cenozoic Birds#Goliathia#Nycticorax#Xenerodiops#Nuphranassa#Janipes#Palaeoephippiorhynchus#Eremopezus

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eremopezus eocaenus

By José Carlos Cortés on @quetzalcuetzpalin-art

PLEASE SUPPORT US ON PATREON. EACH and EVERY DONATION helps to keep this blog running! Any amount, even ONE DOLLAR is APPRECIATED! IF YOU ENJOY THIS CONTENT, please CONSIDER DONATING!

Name: Eremopezus eocaenus

Status: Extinct

First Described: 1904

Described By: Andrews

Classification: Dinosauria, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Palaeognathae, Eremopezidae

What is Eremopezus? A mystery. It is probably from the Jebel Qatrani Formation of Egypt, living about 30.2 - 29.5 million years ago, in the Rupelian age of the Oligocene of the Paleogene (it was once thought that this formation dated to the Eocene, but it has since been re-dated). This formation is notable for the significant number of transitional mammal and bird forms - between the early members of groups known from the Eocene and the close to modern forms from the Neogene. Eremopezus is mysterious both for its age - which makes finding its phylogenetic affinities more difficult than if it were, say, younger and more similar to modern forms - and its incompleteness - it is only known from very limited material of the leg, discovered in two batches, one at the beginning of the 1900s and the other more recently. It was originally considered to be a ratite - but it may, in fact, not be a ratite at all. Eremopezus has a lot of traits that actually aren’t found in ratites at all, but are unique or found in other birds (ie, the Neognaths - the group containing literally all other birds). In fact, it has similar traits to modern Secretarybirds and Shoebill, which are both from Africa as well (though it’s probably not related to either). Still, recent analyses have grouped it with the Elephant Birds - but the jury remains out.

By Jack Wood on @thewoodparable

It is entirely possible that Eremopezus is actually its own distinct lineage of ratite - since almost all ratites evolved flightlessness independently (apart from emu and cassowary which are very closely related), Since most ancestors of ratites and modern ratites are mainly known from recent fossil records, this marks a very early experiment in ratite-like body plan and lifestyle amongst Palaeognaths (given that most large flightless birds of the Paleogene were actually from other bird groups - see Gastornis and the early Terror Birds and Bathornithids). This would also make it a very unique and convergent sort of Paleognath, having evolved traits similar to other bird groups independently. Eremopezus was probably about the size of a modern large rhea or small emu, though it had very robust foot bones that would have been able to support a heavier body than those of the rhea. It probably stood as tall as a person. As such, it probably was flightless, though of course it is difficult to determine that without further fossils and it is possible that it could fly. Its toes flared out from the foot like that of a Cassowary, allowing for the weight to be supported over a larger surface area. The toes would also have been bulkily padded, allowing for the toes to be very flexible and mobile, so it moved around on foot a lot regardless of its flight status and may have used its feet for other activities.

By Scott Reid on @drawingwithdinosaurs

Eremopezus lived in the Jebel Qatrani Formation, an environment of freshwater rivers and shallow low-lying lakes near the Tethys Sea. It was a very tropical environment with monsoon seasons and swamps, and while reed grasses that characterize Egypt today were present, they were much rarer. Many mammals were present including Creodonts and Anthracotheriids, two types of completely extinct mammal lineages that looked like squat felines and elongated hippos respectively; an ancient primate, some shrews and hyraxes and even a marsupial. When it comes to birds, there was a relative of the shoebill, a relative of storks, a relative of herons, as well as cormorants, jacanas, and turacos. There were also crocodilians, gharials, snakes, and turtles. In this environment, it is likely that Eremopezus was some sort of herbivore, even a fruit eater, though without actual fossils of the head or gut contents we can’t know for sure. It may have gone extinct due to habitat turnover as grasses began to spread further in Africa.

Source:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eremopezus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jebel_Qatrani_Formation

#eremopezus#eremopezus eocaenus#bird#dinosaur#birblr#palaeoblr#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature#factfile#Dìneasar#דינוזאור#डायनासोर#ديناصور#ডাইনোসর#risaeðla#ڈایناسور#deinosor#恐龍#恐龙#динозавр#dinosaurio

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shoebill stork diet

When flushed, shoebills usually try to fly no more than 100 to 500 m (330 to 1,640 ft). The pattern is alternating flapping and gliding cycles of approximately seven seconds each, putting its gliding distance somewhere between the larger storks and the Andean condor ( Vultur gryphus). Its flapping rate, at an estimated 150 flaps per minute, is one of the slowest of any bird, with the exception of the larger stork species. Its wings are held flat while soaring and, as in the pelicans and the storks of the genus Leptoptilos, the shoebill flies with its neck retracted. The bill becomes more noticeably large when the chicks are 23 days old and becomes well developed by 43 days. When they are first born, shoebills have a more modestly-sized bill, which is initially silvery-grey. The juvenile has a similar plumage colour, but is a darker grey with a brown tinge. The breast presents some elongated feathers, which have dark shafts. The plumage of adult birds is blue-grey with darker slaty-grey flight feathers. The wings are broad, with a wing chord length of 58.8 to 78 cm (23.1 to 30.7 in), and well-adapted to soaring. The neck is relatively shorter and thicker than other long-legged wading birds such as herons and cranes. The shoebill's feet are exceptionally large, with the middle toe reaching 16.8 to 18.5 cm (6.6 to 7.3 in) in length, likely assisting the species in its ability to stand on aquatic vegetation while hunting. The dark coloured legs are fairly long, with a tarsus length of 21.7 to 25.5 cm (8.5 to 10.0 in). As in the pelicans, the upper mandible is strongly keeled, ending in a sharp nail. The exposed culmen (or the measurement along the top of the upper mandible) is 18.8 to 24 cm (7.4 to 9.4 in), the third longest bill among extant birds after pelicans and large storks, and can outrival the pelicans in bill circumference, especially if the bill is considered as the hard, bony keratin portion. The signature feature of the species is its huge, bulbous bill, which is straw-coloured with erratic greyish markings. A male will weigh on average around 5.6 kg (12 lb) and is larger than a typical female of 4.9 kg (11 lb). Weight has reportedly ranged from 4 to 7 kg (8.8 to 15.4 lb). Length from tail to beak can range from 100 to 140 cm (39 to 55 in) and wingspan is 230 to 260 cm (7 ft 7 in to 8 ft 6 in). The shoebill is a tall bird, with a typical height range of 110 to 140 cm (43 to 55 in) and some specimens reaching as much as 152 cm (60 in). The shoebill's conspicuous bill is its most well-known feature All that is known of Eremopezus is that it was a very large, probably flightless bird with a flexible foot, allowing it to handle either vegetation or prey. It has been suggested that the enigmatic African fossil bird Eremopezus was a relative too, but the evidence for that is unconfirmed. So far, two fossilized relatives of the shoebill have been described: Goliathia from the early Oligocene of Egypt and Paludavis from the Early Miocene of the same country. A 2008 DNA study reinforces their membership of the Pelecaniformes. In 2003, the shoebill was again suggested as closer to the pelicans (based on anatomical comparisons) or the herons (based on biochemical evidence). Microscopic analysis of eggshell structure by Konstantin Mikhailov in 1995 found that the eggshells of shoebills closely resembled those of other Pelecaniformes in having a covering of thick microglobular material over the crystalline shells. Based on osteological evidence, the suggestion of a pelecaniform affinity was made in 1957 by Patricia Cottam. Traditionally considered as allied with the storks ( Ciconiiformes), it was retained there in the Sibley-Ahlquist taxonomy which lumped a massive number of unrelated taxa into their "Ciconiiformes". The genus name comes from the Latin words balaena "whale", and caput "head", abbreviated to -ceps in compound words. John Gould described it in 1850, giving it the name Balaeniceps rex. The shoebill was known to ancient Egyptians but was not classified until the 19th century, after skins and eventually live specimens were brought to Europe. Molecular studies have found the hamerkop to be the closest relative of the shoebill.

0 notes

Text

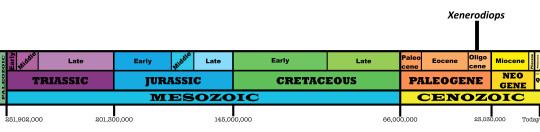

Xenerodiops mycter

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: The strangely appearing Heron

First Described By: Rasmussen et al., 1987

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Aequorlitornithes, Ardeae, Aequornithes, Pelecaniformes

Status: Extinct

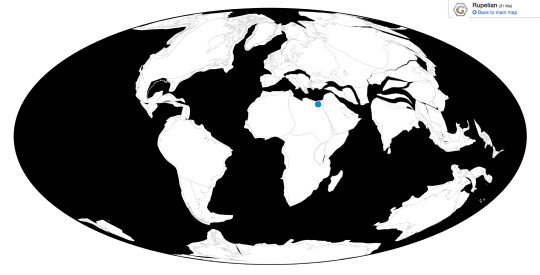

Time and Place: Between 30.2 and 29.5 million years ago, in the Rupelian of the Oligocene

Xenerodiops is known from the Jebel Qatrani Formation of Egypt

Physical Description: Xenerodiops is a strange intermediate bird, slightly smaller than the smallest living stork - probably no longer than 70 centimeters or so. Still, it was larger than most living species of herons - so this wasn’t a small bird. It was fairly similar to storks too, in terms of the shapes of the known bones, so it seems likely that Xenerodiops was a precursor to that modern dinosaur group. It had a very strong, pointed bill, though, more like herons than storks - adapted for biting and even stabbing prey, rather than snapping up food trapped in vegetation. This weirdly short, heavy bill was also curved downwards, so different from living herons and somewhat similar to living storks. Its wings were heavy and robust, and in general, this was a very sturdy sort of bird.

Diet: Xenerodiops probably fed on animals and, if it is a heron-stork like thing as supposed, it is logical to assume these animals were found in bodies of water.

Behavior: Without more fossils of Xenerodiops, it is difficult to piece together how it would have looked - especially without legs, which would point to whether or not this bird waded in the water as those birds it seems to be closely related to do. Still, for now, that is the simplest explanation for its general lifestyle. Its large beak would have been useful in reaching out into bodies of water and grabbing food sharply, possibly even stabbing it; being curved downwards, it could have been used similar to living stork bills in probing for food in the water. It is possible, then, that Xenerodiops did similar things, going into the water and grabbing as much food with its strong beak as possible, sensing food where it could not see. With its strong, robust wings, Xenerodiops would have been a powerful flier, able to gain a lot of movement from very few flaps of their wings. As with other dinosaurs, Xenerodiops would have probably taken care of its young; whether or not it did so in large colonies or in isolated nests is difficult to tell at this point.

Creatures of the Jebel Qatrani by Stanton F. Fink, CC By-SA 2.5

Ecosystem: The Jebel Qatrani Formation is a fairly famous ecosystem from the Oligocene, a time when the weird creatures of the Eocene and Paleocene were beginning to transition into animals similar to those we see today. In addition to almost-modern forms, of course, there were also the fun offshoots, which is probably where Xenerodiops lies. Jebel Qatrani is famous for its transitional fossils, especially among mammals. It was a thick swamp ecosystem, extremely warm and wet - a tropical wetland, filled with animals taking advantage of the lush plantlife. This place was filled with a variety of mammals - dugong relatives like Eosiren, a transitional primate Aegyptopithecus, a weird pointy heavyset mammal Arsinoitherium, the slightly more hippo-esque but still weird Bothriogenys, giant hyraxes, the lemur-like Plesiopithecus, the false ungulate Herodotius, the strange carnivores Ptolemaia and Qarunavus, a marsupial Peratherium, hyaenodonts like Metapterodon, and an alarming number of rodents. Turtles and crocodilians and other reptiles were plentiful too, like the turtle Albertwoodemys, the crocodile Crocodylus megarhinus, a gharial Eogavialis, and the snake Pterosphenus. As for fish, there were a variety of tetras, snakeheads, and catfish.

Xenerodiops wasn’t the only dinosaur in this environment, either. Many other weird birds were found here, some just as odd and unplaceable as Xenerodiops. For example, Eremopezus lived here - it was some sort of large, flightless bird. Beyond that, we have no idea. There was also the (iconic and large) swimming flamingo, Palaelodus. An even larger sort of shoebill than the living one, Goliathia, prowled the swamps. A giant true stork, Palaeoephippiorhynchus, was a major fixture of the landscape. There were Jacanas like Nuphranassa and Janipes, turacos like Crinifer, and even birds of prey. In a lot of ways, therefore, the birds of the area were even weirder than the mammals - and Xenerodiops was just one of many.

By José Carlos Cortés

Other: What exactly Xenerodiops is remains a mystery. Its weird combination of characteristics points to it being in the group of dinosaurs including a large number of living water birds - and both storks and herons. However, research has shown that storks and herons are actually somewhat removed from each other, with herons being more closely related to pelicans, shoebills, ibises, and even boobies than to storks. Is Xenerodiops, then, a weird, transitional, extinct member of this group of dinosaurs? Is it another evolutionary experiment altogether, with traits of many members of this group? Something else entirely? Only more fossils will help us to make the picture clearer. Some of these traits are shared in other weird waterbirds of the Paleogene (such as Mangystania), and it is entirely possible that there is an extinct clade of these animals, separate from all living members of the group.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Mayr, G. 2009. Paleogene Fossil Birds. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

Mayr, G. 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance. Topics in Paleobiology, Wiley Blackwell. West Sussex.

Mlíkovský, Jiří (2003), "Early Miocene Birds of Djebel Zelten, Libya" (PDF), Časopis Národního muzea, Řada přírodovědná, 172 (1–4): 114–120.

Rasmussen, D. T., S. L. Olson, E. L. Simons. 1987. Fossil Birds from the Oligocene Jebel Qatrani Formation Fayum Province, Egypt. Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology 62: 1 - 19.

Zvonov, E. A., N. V. Zelenkov, I. G. Danilov. 2015. A New unusual waterbird (Aves, ?Suliformes) from the Eocene of Kazakhstan. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology: e1035783.

#Xenerodiops mycter#Xenerodiops#Dinosaur#Aequorlitornithian#Bird#Birds#Ardeaen#Factfile#Dinosaurs#Birblr#Palaeoblr#Carnivore#Water Wednesday#Africa#Paleogene#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

219 notes

·

View notes