#Fantasy food

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Last dnd session my silly little nomad was spoiled with a lot of tasty goods! She hasn't eaten this good in months...

#oc - sheng#my art#artists on tumblr#artist#artists#oc#ocs#doodle#doodle sheet#dnd campaign#dnd art#dnd#dnd character#dnd oc#dndads#dungeons and dragons#dnd 5e#dungeons and dragons art#ranger#food#fantasy food#satyr#satyr oc#dnd satyr

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

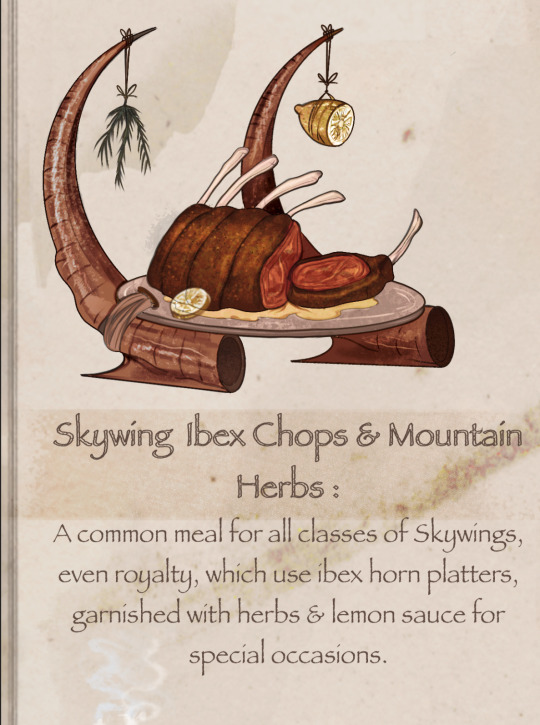

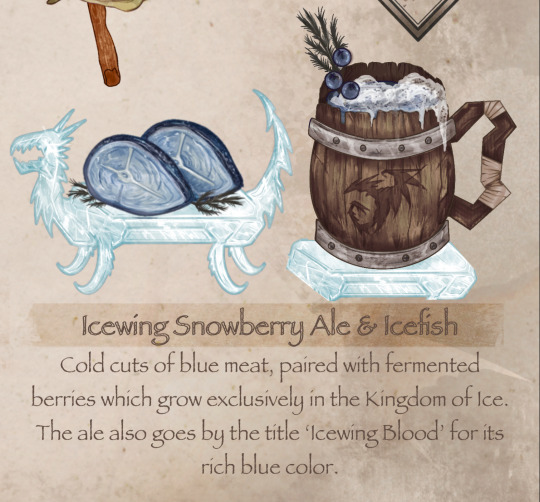

WOF tribe delicacies / treats concepts:

Hey folks! This one was the recent winner of the WOF poll, so here’s my concept art that headcannons foods each tribe is most recognized for!

We know Dragons can hunt on the go, but a prepped meal shared amongst clawmates is more cherished than picking fur out of your teeth!

Not a ton of lore undercut this time. It was super fun drawing fantasy dishes, as I rarely ever draw food or dishware. It was truly a good challenge in creativity and recounting types of the foods mentioned in the series!

#art#illustration#bookart#rainwing#icewing#nightwing#nightwing wof#skywing#mudwing#wof art#wof#seawing#sandwing#food art#fantasy food#concept art#dragon#dragon art#wings of fire art#wings of fire#wings of fire fanart#wof fanart#fantasy concept art

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

*sets a bottle of sky sauce on your levatable*

“Your main courses will be out in a few days.”

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Minecraft nether chicken lore 😭

Finger lickin’ good

#art#my art#spec bio#speculative biology#spec evo#speculative evolution#speculative worldbuilding#specbio#speculative fiction#speculative zoology#nether lore#lore#food worldbuilding#worldbuilding#world building#headcanons#minecraft headcanons#minecraft food#Minecraft#minecraft nether#minecraft chicken#chicken#chickens#idek anymore#food art#fantasy food

264 notes

·

View notes

Text

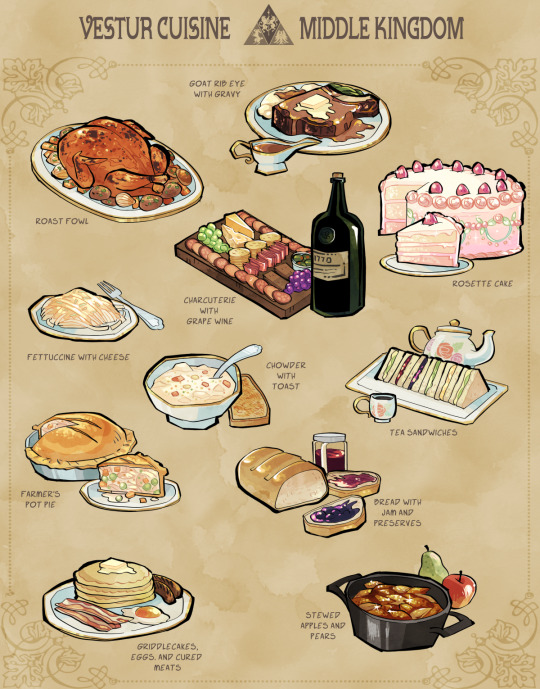

Foods of Vestur

@broncoburro and @chocodile provoked me into doing some illustrated worldbuilding for Forever Gold ( @forevergoldgame ), an endeavor I was happy to undertake. Unbeknownst to me, it would take the better part of a week to draw.

In the process, I conjured about an essay's worth of fantasy food worldbuilding, but I'm going to try and keep things digestible (pardon my pun). Lore under the cut:

The Middle Kingdom

The Middle Kingdom has ample land, and its soil, landscapes, and temperate climate are amenable to growing a variety of crops and raising large quantities of livestock. The Midland palate prefers fresh ingredients with minimal seasoning; if a dish requires a strong taste, a cook is more likely to reach for a sharp cheese than they are to open their spice drawer. Detractors of Middle Kingdom cuisine describe it as bland, but its flavor relies on the quality of its components more than anything.

KEY CROPS: wheat, potatoes, carrots, green beans, apples, pears, and grapes KEY LIVESTOCK: Midland goats, fowl, and hogs

ROAST FOWL: Cheap and easy to raise, fowl is eaten all over Vestur and by all classes. Roasted whole birds are common throughout, but the Middle Kingdom's approach to preparation is notable for their squeamish insistence on removing the head and neck before roasting, even among poorer families. Fowl is usually roasted on a bed of root vegetables and shallots and served alongside gravy and green beans.

GOAT RIBEYE: Vestur does not have cattle – instead it has a widely diversified array of goats, the most prominent being the Middle Kingdom's own Midland goat. The Midland goat is a huge caprid that fills the same niche as cattle, supplying Vestur with meat and dairy products. Chevon from the Midland goat is tender with a texture much like beef, though it retains a gamier, “goat-ier” taste. It is largely eaten by the wealthy, though the tougher and cheaper cuts can be found in the kitchens of the working class. Either way, it is almost always served with gravy. (You may be sensing a pattern already here. Midlanders love their gravy.)

FETTUCCINE WITH CHEESE: Noodles were brought to the Middle Kingdom through trade with the South and gained popularity as a novel alternative to bread. The pasta of Midland Vestur is largely eaten with butter or cream sauce; tomato or pesto sauces are seldom seen.

CHARCUTERIE WITH WINE: Charcuterie is eaten for the joy of flavors rather than to satiate hunger, and therefore it is mainly eaten by the upper class. It is commonly eaten alongside grape wine, a prestigious alcohol uniquely produced by the Middle Kingdom. The flavor of grape wine is said to be more agreeable than the other wines in Vestur, though Southern pineapple wine has its share of defenders.

BREAD WITH JAM AND PRESERVES, TEA SANDWICHES, & ROSETTE CAKE: Breads and pastries are big in the Middle Kingdom. The Middle Kingdom considers itself the world leader in the art of baking. Compared to its neighbors, the baked goods they make are soft, light, and airy and they are proud of it. Cakes in particular are a point of ego and a minor source of mania among nobility; it is a well-established cultural joke that a Middle Kingdom noble cannot suffer his neighbor serving a bigger, taller cake. The cakes at Middle Kingdom parties can reach nauseatingly wasteful and absurdist heights, and there is no sign of this trend relenting any time soon.

CHOWDER, FARMER'S POT PIE, GRIDDLECAKES, EGGS, CURED MEATS: If you have the means to eat at all in the Middle Kingdom, you are probably eating well. Due to the Midland's agricultural strength, even peasant dishes are dense and filling. Eggs and cured meats are abundant, cheaper, and more shelf stable than fresh cuts and provide reprieve from the unending wheat and dairy in the Midland diet.

STEWED APPLES AND PEARS, JAM AND PRESERVES: The Midland grows a number of different fruits, with apples and pears being the most plentiful. In a good year, there will be more fruit than anyone knows what to do with, and so jams and preserves are widely available. Stewed fruit has also gained popularity, especially since trade with the Southern Kingdom ensures a stable supply of sugar and cinnamon.

NORTHERN KINGDOM - SETTLED

The Northern Kingdom is a harsh and unforgiving land. Historically, its peoples lived a nomadic life, but since the unification of the Tri-Kingdom more and more of the Northern population have opted to live a settled life. The “settled North” leads a hard life trying to make agriculture work on the tundra, but it is possible with the help of green meur. The Northern palate leans heavily on preserved and fermented foods as well as the heat from the native tundra peppers. Outsiders often have a hard time stomaching the salt, tang, and spice of Northern cuisine and it is widely considered “scary.”

KEY CROPS: potatoes, beets, carrots, tundra pepper KEY LIVESTOCK: wooly goats, hares*

GOAT POT ROAST: Life up north is hard work and there is much to be done in a day. Thus, slow cooked one-pot meals that simmer throughout the day are quite common.

VENISON WITH PICKLES: Game meat appears in Northern dishes about as much as farmed meat – or sometimes even more, depending on the location. Even “classier” Northern dishes will sometimes choose game meat over domesticated, as is the case with the beloved venison with pickles. Cuts of brined venison are spread over a bed of butter-fried potato slices and potent, spicy pickled peppers and onions. The potatoes are meant to cut some of the saltiness of the dish, but... most foreigners just say it tastes like salt, vinegar, and burning.

MINER STEW: While outsiders often have a hard time distinguishing miner stew from the multitude of beet-tinged stews and pot roasts, the taste difference is unmistakable. Miner's stew is a poverty meal consisting of pickles and salt pork and whatever else is might be edible and available. The end result is a sad bowl of scraps that tastes like salt and reeks of vinegar. The popular myth is that the dish got its name because the Northern poor began putting actual rocks in it to fill out the meal, which... probably never happened, but facts aren't going to stop people from repeating punchy myths.

RYE TOAST WITH ONION JAM: Rye is hardier than wheat, and so rye bread is the most common variety in the North. Compared to Midland bread, Northern bread is dense and gritty. It is less likely to be enjoyed on its own than Midland bread, both because of its composition and because there's less to put on it. Unless you've the money to import fruit spreads from further south, you're stuck with Northern jams such as onion or pepper jam. Both have their appreciators, but bear little resemblance to the fruit and berry preserves available elsewhere in Vestur.

HARE DAIRY: Eating hare meat is prohibited in polite society due to its association with the haretouched and heretical nomadic folk religions, but hare dairy is fair game. Hare cheese ranges from black to plum in color, is strangely odorless, and has a pungent flavor akin to a strong blue cheese. It is the least contentious of hare milk products. Hare milk, on the other hand, is mildly toxic. If one is not acclimated to hare milk, drinking it will likely make them “milk sick” and induce vomiting. It is rarely drunk raw, and is instead fermented into an alcoholic drink similar to kumis.

MAPLE HARES AND NOMAD CANDY: Maple syrup is essentially the only local sweetener available in the North, and so it is the primary flavor of every Northern dessert. Simple maple candies are the most common type of sweet, though candied tundra peppers – known as “nomad candy” – is quite popular as well. (Despite its name, nomad candy is an invention of the settled North and was never made by nomads.)

TUNSUKH: Tunsukh is one of the few traditions from the nomadic era still widely (and openly) practiced among Northern nobility. It is a ceremonial dinner meant as a test of strength and endurance between political leaders: a brutally spiced multi-course meal, with each course being more painful than the last. Whoever finishes the dinner with a stoic, tear-streaked face triumphs; anyone who cries out in pain or reaches for a glass of milk admits defeat. “Dessert” consists of a bowl of plain, boiled potatoes. After the onslaught of tunsukh, it is sweeter than any cake.

NORTHERN KINGDOM – NOMADIC NORTH

Although the Old Ways are in decline, the nomadic clans still live in the far North beyond any land worth settling. They travel on hareback across the frozen wasteland seeking “meur fonts” - paradoxical bursts of meur that erupt from the ice and provide momentary reprieve from the harsh environment. The taste of nomad food is not well documented.

KEY CROPS: N/A KEY LIVESTOCK: hares

PEMMICAN: Nomadic life offers few guarantees. With its caloric density and functionally indefinite “shelf life,” pemmican is about as close as one can get.

SEAL, MOOSE: Meat comprises the vast majority of the nomadic diet and is eaten a variety of ways. Depending on the clan, season, and availability of meur fonts, meat may be cooked, smoked, turned to jerky, or eaten raw. Moose and seal are the most common sources of meat, but each comes with its own challenges. Moose are massive, violent creatures and dangerous to take down even with the aid of hares; seals are slippery to hunt and only live along the coasts.

WANDER FOOD, WANDER STEW: When a green meur font appears, a lush jungle springs forth around it. The heat from red meur fonts may melt ice and create opportunities for fishing where there weren't before. Any food obtained from a font is known as “wander food.” Wander food is both familiar and alien; the nomads have lived by fonts long enough to know what is edible and what is not, but they may not know the common names or preparation methods for the food they find. Fish is simple enough to cook, but produce is less predictable. Meur fonts are temporary, and it's not guaranteed that you'll ever find the same produce twice - there is little room to experiment and learn. As a result, a lot of wander food is simply thrown into a pot and boiled into “wander stew,” an indescribable dish which is different each time.

CENVAVESH: When a haretouched person dies, their hare is gripped with the insatiable compulsion to eat its former companion... therefore, it is only proper to return the favor. Barring injury or illness, a bonded hare will almost always outlive its bonded human, and so the death of one's hare is considered a great tragedy among nomads. The haretouched – and anyone they may invite to join them – sits beside the head of their hare as they consume as much of its rib and organ meat as they can. Meanwhile, the rest of the clan processes the remainder of the hare's carcass so that none of it goes to waste. It is a somber affair that is treated with the same gravity as the passing of a human. Cenvavesh is outlawed as a pagan practice in the settled North.

HARE WINE: While fermented hare's milk is already alcoholic, further fermentation turns it into a vivid hallucinogen. This “hare wine” is used in a number of nomad rituals, most notably during coming of age ceremonies. Allegedly, it bestows its drinker with a hare's intuition and keen sense of direction... of course, truth is difficult to distinguish from fiction when it comes to the Old Ways.

SOUTHERN KINGDOM

The Southern Kingdom is mainly comprised of coast, wetland, and ever-shrinking jungle. While the land is mostly unfit for large-scale agriculture, seafood is plentiful and the hot climate is perfect for exorbitant niche crops. What they can't grow, they obtain easily through trade. Southerners have a reputation for eating anything, as well as stealing dishes from other cultures and “ruining” them with their own interpretations. KEY CROPS: plantains, sweet potato, pineapple, mango, guava, sugarcane KEY LIVESTOCK: fowl, marsh hogs, seals

GLAZED EEL WITH FRIED PLANTAINS: A very common configuration for Southern food is a glazed meat paired with a fried vegetable. It almost doesn't matter which meat and which vegetable it is – they love their fried food and they love their sweet and salty sauces in the South. Eel is a culturally beloved meat, much to the shock and confusion of visiting Midlanders.

NARWHAL STEW: Narwhal stew is the South's “anything goes” stew. It does not actually contain narwhal meat, as they are extinct (though the upper class may include dolphin meat as a protein) – instead, the name comes from its traditional status as a “forever soup,” as narwhals are associated with the passage of time in Southern culture. Even in the present day, Southern monasteries tend massive, ever-boiling pots of perpetual stew in order to feed the monks and sybils who live there. Narwhal stew has a clear kelp-based broth and usually contains shellfish. Beyond that, its ingredients are extremely varied. Noodles are a popular but recent addition.

FORAGE: The dish known as “forage” is likewise not foraged, or at least, it hasn't been forage-based in a good hundred years at least. Forage is a lot like poke; it's a little bit of everything thrown into a bowl. Common ingredients include fish (raw or cooked), seaweed, fried noodles, marinated egg, and small quantities of fruit.

HOT POT: Hot pot is extremely popular, across class barriers, in both the South proper and its enclave territories. This is due to its extreme flexibility - if it can be cooked in a vat of boiling broth, it will be. Crustaceans and shellfish are common choices for hot pot in the proper South, along with squid, octopus, mushrooms, and greens.

FLATBREAD: The Southern Kingdom doesn't do much baking. The vast majority of breads are fried, unleavened flatbreads, which are usually eaten alongside soups or as wraps. Wraps come in both savory and sweet varieties; savory wraps are usually stuffed with shredded pork and greens while sweet wraps – which are much more expensive – are filled with fruit and seal cheese.

GRILLED SKEWERS, ROAST SWEET POTATO: While a novel concept for Midlanders and Northerners, street food has long been a part of Southern Kingdom culture. You would be hard pressed to find a Southern market that didn't have at least three vendors pushing grilled or fried something or other. Skewers are the most common and come in countless configurations, but roast sweet potatoes are a close second.

CUT FRUIT AND SEAL CHEESE: Fresh fruit is popular in the South, both local and imported. While delicious on its own, Southerners famously pair it with seal cheese. Which leads me to an important topic of discussion I don't have room for anywhere else...

THE SOUTH AND CHEESE: Since the South doesn't have much in the way of dairy farming, cheese is somewhat rare in their cuisine – but it is present. And important. Cheese is the domain of the Church. Common goat dairy imported from the Middle Kingdom is turned to cheese by monks in Southern monasteries and sold to the Southern public, yes, but as you have noticed there is another cheese prominent in the Southern Kingdom diet: seal cheese. Seal cheese is unlike anything else that has ever been called cheese; the closest it can be compared to is mascarpone. It is is a soft, creamy cheese with a mild flavor and an indulgent fat content. It is used almost exclusively as a dessert, though it is only ever mildly sweetened if at all. It is extremely costly and held in high regard; the most religious Southerners regard it as holy. Dairy seals are a very rare animal and raised exclusively in a small number of Cetolist-Cerostian monasteries, where they are tended and milked by the monks. Due to their status as a holy animal, eating seal meat is forbidden. Eating their cheese and rendering their tallow into soap is fine though.

(HEARTLAND SOUTH) SOUTH-STYLE GOAT: The Heartland South is a Southern enclave territory in the Middle Kingdom. Visiting Midland dignitaries oft wrongly assume that because the Heartland South is in Middle Kingdom territory, Heartland Southerners eat the same food they do exactly as they do. They are horrified to find that familiar sounding dishes like “goat with potatoes” are completely and utterly unrecognizable, drenched in unfamiliar sauces and spices and served alongside fruit they've never eaten. Meanwhile, Heartland Southerners firmly believe that they have fixed the Middle Kingdom's boring food.

(BOREAL SOUTH) “TUNSUKH”: If Midlanders are afraid of Heartland Southern food, Northerners are absolutely furious about cuisine from the Boreal South - the most legendarily offensive being the Boreal South's idea of “tunsukh.” Southerners are no stranger to spice, so when Southern traders began interacting with the North, they liked tunsukh! It's just... they thought it needed a little Southern help to become a real meal, you know? A side of seal cheese soothed the burn and made the meal enjoyable. And because the meal was enjoyable, the portion sizes increased. And plain boiled potatoes? Well, those are a little too plain – creamy mashed sweet potato feels like more of a dessert, doesn't it? ...For some reason, Northerners didn't agree, but that's okay. The Boreal South knows they're just embarrassed they didn't think of pairing seal cheese with tunsukh sooner.

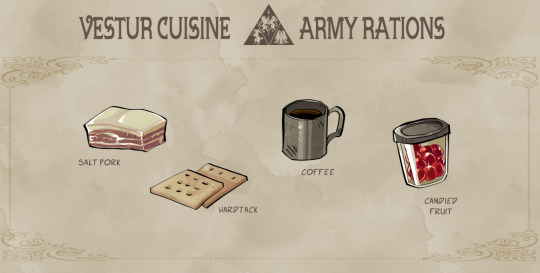

ARMY RATIONS

The food eaten by the King's Army is about what you would expect for late 1700s military; salt pork or salt chevon, hard tack, and coffee. The biggest divergence they have is also one of Vestur's biggest points of pride: they have the means to supply their troops with frivolous luxuries like small tins of candied fruit from the Midland. A love of candied fruit is essentially a Vesturian military proto-meme; proof that they serve the greatest Tri-Kingdom on the planet. Don't get between a military man and his candied fruit unless you want a fight.

#verse: forever gold#worldbuilding#fantasy worldbuilding#food worldbuilding#fantasy food#food art#animal death//#might have to proofread this later forgive any typos I am tired

768 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thought it would be fun to illustrate some Amaranthine cuisine from various regions (and time periods). Long writeups under the cut!

Western Kingdom Cuisine: Northern Upper Class

The cultural cuisine of the northern part of the Western Kingdom is shaped by the region's harsh, snowy climate. The cold meant that it was easier to keep food from spoiling, but hard to find it in the first place. During the warmer spring and summer months, food would be collected and then salted, dried, pickled, or otherwise preserved in order to last through the winter. Red meat is their primary dietary staple, and is served in a wide variety of ways, including raw and engastrated. Dairy is also common in all forms -- cheese, butter, milk, and as a component of common sauces and chowders (another cultural favorite, and great way to use up leftovers). Alcohol is also common, with a favorite cultural drink being a spiced, warmed fermented milk with a flavor similar to eggnog.

Northern dishes prioritize making use of all parts of the animal, especially nutrient-rich organ meats and fat. As a landlocked region with few rivers, fish is somewhat uncommon, but not unheard of, especially salted or pickled fish shipped in from the south. Also, as mentioned before, eating animals, including "one's own kind", is not taboo at all in this region. In such harsh climates, turning one's nose up at a filling meal is seen as ridiculous.

When good meat is available, though, presentation can get a little… creative. Or, as some might describe it, obscene. Feasts for nobles often involve whole roast hogs stuffed with turkeys stuffed with game birds stuffed with exotic, imported pickled fish, ground meat sculpted into strange and creative shapes, and other ostentatious displays. If a nobleman's chefs can do something artistic with the meat that his guests have never seen before, it's considered very impressive. Of course, to foreigners, a western kingdom noble's banquet can look rather nightmarish and grotesque. Such displays of excess are generally the realm of the wealthy, but most families will still celebrate with a "turducken" or similar engastrated roast once a year during winter feast.

Fresh fruits and vegetables make up only a small component of northern dishes. Berry preserves and pickled vegetables are prepared during the summer months, but the only "fresh" vegetables accessible during colder months are hardy root vegetables and tubers harvested from geothermal caves. Mushrooms, also harvested from the caves, are eaten in many forms.

Bread made in this region is typically very hard and dense. This "thickbread" is intended to be soaked in gravy, milk, or soup to soften it and make it more palatable. Attempting to eat the bread without softening it is a clear indicator that someone is a foreigner, or perhaps so poor that they can't afford a proper meal. Some "thinbread" is baked slightly softer and intended to be eaten in slices, but culturally, it's still expected that you put some sort of gravy or spread on it so that you don't look like a confused foreigner or destitute peasant.

For dessert, northerners often eat dessert breads soaked in sweetened, spiced cream and topped with berry preserves and candied mushrooms. Berry tarts are also made with preserves during colder months and fresh fruit during summer months, and are associated with spring, celebration, and hardship ending. These berry tarts are often eaten at celebratory dinners at the end of winter and given to students after finishing exams.

Many residents of other territories find traditional northerner food a little overwhelming due to how rich and dense it is. It can certainly take some getting used to. Eastern Kingdom residents tend to find northern cuisine especially nightmarishly grotesque and barbaric due to their cultural views around meat. However, with increased trade and travel over the last few decades, northerner food is beginning to look more like the food from the rest of the Western Kingdom, and some of the more offputting cultural practices like the ostentatious engastrated meatcraft and inedible-unless-softened bread are becoming somewhat less popular.

Eastern Kingdom Cuisine: Coastal Citydweller

The Eastern Kingdom's cuisine is similarly influenced by their climate. The desert that spans much of the region meant that, aside from its sparkling oasis cities and rim of fishing towns along the coast and major river, many residents traditionally lived a nomadic lifestyle. Additionally, unlike the Western Kingdom, they absolutely do view "eating your own kind" as tantamount to cannibalism, which meant that most red meat was only consumed during times of desperation or occasionally during holidays/rituals, though the latter is mostly seen as a weird unsavory rural thing.

The Eastern Kingdom's meat taboo generally does not extend to fish, shellfish, and insects. Fresh fish and shellfish are routinely consumed near the coast, often seared in olive oil and spices and served over a couscous-like grain base, and a salty paste made of fermented fish is smeared on bread in interior regions. Beetles coated in chopped nuts and chili powder and dried, and honeyed crickets are also popular snacks.

Eastern Kingdom cuisine also involves a lot of nuts, beans, and seeds as major dietary staples. These foods are long-lasting, spoilage-resistant, nutrient-rich, and grew easily along the banks of the kingdom's major waterway and oases even before cities settled there. These three food groups are found in nearly all of their cooking. Nuts and seeds are baked into bread and desserts but also mixed into stir fry-type dishes to add protein. A common dessert and trail snack consists of dried dates mixed with walnuts. Dates and figs are also made into jams and eaten spread over bread or as a component in sauces.

Vegetables and fruits, as well as olives, were grown in grand, sprawling, aqueduct-fed gardens in oasis cities and on riverbanks. Cacti, once cultivated extensively by ancient nomads, are served chopped and glazed with honey, another dietary staple.

Dairy, derived from pack animals used by nomads, is also somewhat common, though difficult to transport without spoilage. It is paradoxically seen as a practical, basic food by nomads and farmers, who can milk it directly from its source, something of a luxury by city-dwellers.

Additionally, the Eastern Kingdom's sprawling coastlines mean an extensive seafaring presence. As a result, they have brought back many novel plants from far afield to be cultivated in the Eastern Sultan's personal palace garden. Among these: cocoa beans, which are refined into a spicy energizing herbal drink similar to coffee. "Chocolate houses" serving this drink can be found throughout larger cites, sometimes mixing the cocoa drink with more familiar sweetened cactus juice to stretch the expensive cocoa powder further.

Post-Fall Cuisine: Ironfrost Middle Class

The society that eventually emerged after the fall of the Old Kingdoms was quite different from what came before. Though discovery of ironworking led to the rise of industrialization--processed food and automated canning, among other innovations-- the harsh, permanent winter that eventually consumed most of the continent meant that cuisine never reached the levels of decadence it had in the Old Kingdoms. This is especially true of the working class in Ironfrost, whose rather dreary cuisine is shown here.

Limited accessibility of fresh fruits and vegetables--grown in engineered greenhouses or shipped in from the far south over increasingly long distances as the cold spread southward--meant that nearly all vegetables are eaten canned. Many, especially those in rural northern towns that lacked greenhouses, may have never even seen a fresh tomato or head of lettuce before. (The City of the Sun produces fresh fruit and vegetables for the far north--including exotic apples in nigh-extinct Old Kingdom varieties--but cutting a trade deal with the reclusive city-state can be difficult due to the whims of its elusive cultish leader.)

The one exception? Mushrooms. Like the Western Kingdom northerners that lived there before them, Post-Fall societies came to rely heavily on harvesting edible mushrooms from the geothermal caves below the tundra. Mushrooms are a crucial dietary staple and can be roasted, pickled, fried, pureed, or even candied. Many of the more specialized cooking styles such as candying were passed down by survivors of the fallen Western Kingdom, thought the passage of time and changing availability of spices and other ingredients have rendered many recipes quite different from their ancestors.

Fresh meat is easier to access and easier to preserve with minimal loss of taste or texture thanks to the frigid weather providing easy "refrigeration" by way of outdoor iceboxes. However, a whole, freshly-cooked roast is still considered a rare treat for most, especially for the mine and factory workers living within the dense industrial labyrinths of Ironfrost. Canned and dried meats are popular due to being less sensitive to spoilage when kept indoors or transported across different climates.

Overall, the heavy reliance on dried and canned food means that most available ingredients are ugly, mushy, and lacking in natural taste due to the extensive preservation process. As a result, stews, loafs, and casseroles are common, as well as jellied aspic dishes. Any manner of preparation that can hide the appearance of limp, shriveled vegetables or disguise the taste of eating the same salted meat every day is useful. Creative meat presentation, such as sculpting ground meat into fun shapes, decorated meatloaf, and ornate aspic molds is another cultural holdover passed on by Western Kingdom survivors, though in the current day it's associated more with the middle or lower middle class rather than nobility. It is now more of a way to make the most out of poor circumstances than to impress fellow nobles at parties.

(Side note, not pictured: Modern day Ironfrost elite tend to favor very plain dishes made out of fresh food, garnished with sliced fruit--the mere fact that they can access such exotic fare makes their wealth self-evident! An aspiring elite with limited funds can choose to rent a bowl of Sun City apples or even an elusive pineapple to impress party guests instead.)

One of the few pieces of Eastern Kingdom food culture that survived to the present day is chocolate, though like Western Kingdom dishes, it is now quite different from its original form. These days, cocoa is blended with fat and sugar and eaten as a dessert: chocolate. This has caused its popularity to explode. Chocolate bars are incredibly popular for their delicious taste and portability, and cakes and cookies made with chocolate are coveted by the poor and wealthy alike. Of course, the cold climate means that cocoa beans can only be grown in specialized greenhouses, and the owners of these greenhouses are keen to charge a premium for access. Ironfrost and The City of the Sun are the two major cocoa producers and it's not unheard of for Ironfrost soldiers to bully smaller cocoa growers out of business to maintain their near-monopoly. Still, hidden cocoa grows scattered around the tundra ensure that a large supply of "bootleg" chocolate remains on the menu--just don't get caught with it in Ironfrost territory.

483 notes

·

View notes

Text

My boy Nalu made some delicacy from his home for his beloved crew mates while they were gone!

#digital art#drawing#fantasy#dragon#character design#dragonborn#dnd#dnd art#dnd character#dragonborn character#sketch#my art#my ocs#garden eels#garden eel noodles with scallop sauce <3#<3#himbo#people pleaser#artists on tumblr#art on tumblr#original art#food drawing#fantasy food

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

So my love of food worldbuilding has gotten the better of me.

I am writing a fantasy world cookbook.

#my own fantasy world to be concise lol#from the world of ocw#wip: on crimson wings#worldbuilding#food#high fantasy#fantasy#fantasy worldbuilding#fantasy food

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

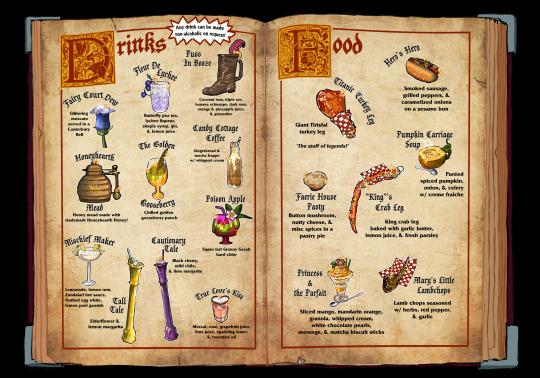

Our official menu for the STVBB24, created by @buttart !

#stvbb24#world of warcraft#stvbb#stranglethorn bonfire bash#roleplay event#rp event#stvbb2024#world of warcraft rp#epsilon rp#menu#rp menu#fantasy food#food#drink#alcohol

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 𝕭𝖔𝖌𝖑𝖊 𝕾𝖆𝖚𝖈𝖊𝖑𝖎𝖓𝖌 🥘

#illustration#artists on tumblr#my art#fantasy art#goblin#faerie#cooking#fantasy food#fantasy illustration#food#foodie#faerie food#goblin hill#watercolor#magic

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Recipe for Daropaka and a Korithian Meal

Hello everyone! (More than) A few days ago I said that, as a way to celebrate reaching 200 followers that I would make one of the dishes from the setting of my WIP. I did something similar for 100 followers which you can see here. This time around I put up a poll to see what dish you all would like to see based on the favorite dishes of my OCs. You voted for Otilia's favorite food, a cheesecake (Daropaka) from the land of Korithia.

However because I felt a bit bad about how long it took me to get to this and because I needed to make something for dinner anyway, I prepared an entire Korithian meal, specifically the last dinner Otilia ate before she left her homeland.

I will give a short description and some history for each component of the meal and will also provide recipes. These recipes come specifically from the Korithian city-state of Kalmanati.

BIG POST ALERT

The diet of Korithians is highly reliant on cereals, grapes, and olives. Barley is the most commonly consumed cereal and is used in the bread of most commoners. However, Kalmanati is famed for the quality of its wheat, and particularly among the wealthy, wheat is the cereal grain of choice. Legumes (Lentils, peas, vetch, beans, etc), vegetables (Cabbage, carrots, lettuce, seaweeds, artichokes, asparagus, onions, garlic, cucumber, beets, parsnips, etc.) and fruits/nuts (pomegranate, almond, fig, pear, plum, apple, dates, chestnuts, beechnuts, walnuts, rilogabo(Kishite regalu "Sunfruit"), bokigabo (Kishite botagalu "Northern fruit), etc.) also make up a significant portion of the Korithian diet, with meat (Cattle, lamb, pig, goat, goose, duck, horned-rabbit, game) and fish typically filling a relatively minor role except for in the diets of wealthy individuals (like Otilia).

Vinegar, oil, and garlic appear in almost all Korithian dishes and are an essential aspect of the Korithian palate.

Recipes below the cut!

The components of the meal are as follows:

Daropaka: (Korithian: Daro = cheese, paka = cake)

Karunbarono: (Korithian: Karun = meat, baro = fire (barono = roasted) )

Pasrosi Diki: (Korithian: Pasrosi = fish(es), Diki = small)

Psampisa : (Korithian: Psamsa = bread, episa = flat)

Akuraros : (Korithian: Akuraros = cucumber)

Ewisasi : (Korithian: Ewisasi = olives)

Funemikiwados: (Korithian: Funemiki = hill (mountain diminutive), wados = oil/sauce)

Wumos: (Korithian: Wumos = wine)

Daropaka aka Awaxpaka aka Korithian Cheesecake

Daropaka is a popular dessert in Korithia, however its origins predate Korithia by several thousand years.

The dish originates from a race of forestfolk living on the Minosa, known as the Awaxi. The Awaxi were a tall and powerful race, some rivaling even demigods in size. Aside from their size the Awaxi were also easily identifiable by the third eye which sat on their forehead and the porcupine like quills which grew from their shoulders, sometimes called the Awaxi mantle.

The Awaxi were a primarily pastoralist civilization, living in small semi-temporary communities where they raised cattle and goats. They are credited with inventing cheese.

The first humans that the Awaxi came into contact with were the Arkodians. The Arkodians introduced the Awaxi to metallurgy, and in exchange the Arkodians were given knowledge of the cheesemaking process. This early form of cheese was called darawa (Korithian: Daro) and was typically made from cow's milk and vinegar, the resulting cheese being soft and crumbly, similar to a ricotta.

Unfortunately peace would not last. The Awaxi settled disagreements and debates often through duels, rather than through war. While quite skilled duelists, their culture had no reference for strategy in battle and lacked the proper skills to fend off the organized assault from imperialistic Arkodians. The Awaxi were eventually driven to extinction, though they still appear as monsters in Korithian myth.

The Arkodians themselves would later fall, destroyed by the Kishites, however many of their recipes, including their recipe for cheesecake, would be passed down to their descendants, the Korithians.

Recipe

(Note that Korithia has no distinct set of measurements nor are recipes recorded. Recipes are typically passed down orally and differ greatly between regions and even families. Adjust ingredients to one's own liking) (Also note that this is not like a modern cheesecake, as it utilizes a ricotta like cheese the texture will not be as smooth and it doesn't use eggs as chickens have not yet been introduced to Korithia)

The Cheese

1/2 Gallon of Whole Cow or Goats Milk

1 Pinch of Sea Salt

2 Bay leaves

2 Tablespoons of White Vinegar

1 Large Ripe Pear

6 Tablespoons Honey

2 Tablespoons White Wheat Flour

1 Tablespoon Rilogabo Juice (substitute 1:1 Orange and Lemon juice)

The Crust

1 Cup White Wheat flour

Water, Warm

1 Pinch of Sea salt

The Topping

1 Sprig Rosemary

3 tablespoon honey

2 tablespoon rilogabo juice (see above)

1 Large pear (optional)

Fill a pot with milk. Stir in salt and add bay leaves. Heat over medium heat until milk registers around 190 F, do not allow to boil. Look for slight foaming on the surface, when the temperature has been reached, remove the bay leaves and add vinegar, the curds will begin to form immediately, stir to fully incorporate vinegar without breaking curds. Stop.

Take the pot off of the heat and cover, allow it to sit for 15 minutes.

Using cheesecloth, a fine mesh strainer or both, separate the curds from the whey. Allow the curds to cool and drain off excess liquid.

Preheat the oven to 410 F or 210 C. Grease the bottom and sides of an 8 inch cake pan with olive oil.

While cheese is draining, make the crust. Knead the white wheat flour with a pinch of salt and warm water for about 15-20 minutes, until obtaining a smooth consistency. Roll a thin circular sheet larger than the cake pan. Lay the dough inside, trim off any dough which hangs over the edge of the pan.

Skin and seed 1 large pear, using either a mortar and pestle or a food processor, break the pear down into a paste or puree, there should be no large visible chunks.

Combine drained cheese, 6 tbsp honey, pear puree, flour, and rilogabo juice. Using a food processor or other implement combine ingredients until a smooth texture is achieved. Taste and add honey accordingly

Pour the mixture into the pan, careful not to exceed the height of the crust. Top with a sprig of rosemary and place into the oven.

Cook for 25-30 minutes or until the filling has set and the surface is golden.

Make the topping by combining 3 tablespoons of honey and the remaining rilogabo juice.

Remove cake from the oven and pour the topping over the surface. Allow the cake to cool

Serve warm, cold, or room temperature with fresh fruit.

Karunbarono aka Roasted Meat

Cooking meat on skewers is a staple of Korithian cuisine, so much so that in certain regions the metal skewers or kartorosi, can be used as a form of currency. Meat is typically cooked over an open fire or on portable terracotta grills, though it is not unheard of to use a large beehive shaped oven or baros. The majority of the meat eaten by the lower classes comes in the form of small game such as rabbit or sausages made from the scraps of pork, beef, mutton, poultry, and even seafood left after the processing of more high-class cuts. The chicken has not yet been properly introduced to the islands, though some descendants of pre-Calamity chickens do exist, though they in most cases have drastically changed because of wild magic. Animals are rarely eaten young, lambs for example are almost never eaten as their potential for producing wool is too valuable. Most animals are allowed to age well past adulthood, except for in special circumstances. The practice of cooking meat in this style is prehistoric stretching back far before Korithia or Arkodai. What is newer however is the practice or marinading the meat before cooking it, this is a Korithian and later Kishite innovation.

Recipe

1 lb Mutton (meat used in this recipe), beef, lamb, venison, or horned-rabbit meat (in order to achieve this it is suggested to use wild hare meat in combination with pork fatback) chopped into bite sized pieces

4 Tablespoons Plain Greek Yogurt

4 Tablespoons Dry Red wine (Any dry red will work, for this recipe I used a Montepulciano d'abruzzo but an Agiorgitiko would work perfectly for this)

3 Tablespoons Olive Oil

4 Cloves of Garlic roughly chopped

1 Small onion roughly chopped

1 sprig fresh thyme

1 sprig fresh rosemary

1 tsp sea salt

1 tsp black pepper

1/2 tsp ground cumin

Gather and measure ingredients

Combine everything into a large bowl and stir, making sure that all pieces of meat are covered in the marinade.

Cover and allow meat to sit, preferably in the fridge for 2 hours or up to overnight.

Well the meat is marinating, if using wooden or bamboo skewers, soak in water for at least one hour to prevent burning.

Preheat the oven to 400 F or roughly 205 C. Or if cooking an open fire, allow an even coal bed to form.

Remove meat from the fridge, clean off excess marinade including any chunks of garlic or onion

Place meat tightly onto the skewers making sure that each piece is secure and will not fall off.

Brush each skewer with olive oil and additional salt and pepper to taste, optionally add a drizzle of red wine vinegar.

Place on a grate either in the oven with a pan below it to catch drippings or else over the fire. Allow to cook for 10-20 minutes depending on how well you want your meat cooked (less if using an open fire) Check every five minutes, flipping the meat after each check.

Remove from the oven and serve immediately.

Pasrosi Diki aka Little Fishes

Despite living by the sea, fish makes up a surprisingly small part of most Korithians' diet. The most valuable fish typically live far away from shore, where storms and sea monsters are a serious threat to ships. Much of the fish that is eaten are from smaller shallow water species, freshwater species, or shellfish. Tuna, swordfish, sturgeon, and ray are considered delicacies, typically reserved for the wealthy. Marine mammals such as porpoise are eaten on rare occasions, typically for ceremonial events. Pike, catfish, eel, sprats, sardines, mullet, squid, octopus, oysters, clams, and crabs are all consumed by the poorer classes. Sprats and sardines are by far the most well represented fish in the Korithian diet, typically fried or salted, or even ground and used in sauces. This particular recipe makes use of sprats. Unlike their neighbors in Baalkes and Ikopesh, Korithians rarely eat their fish raw with the exception of oysters.

Recipe

(Note that unlike modern recipes using whitebait, these are not breaded or battered as this particular cooking art has not yet been adopted in Korithia, though it is in its infancy in parts of Kishetal)

10-15 Sprats (other small fish or "whitebait" can also be used)

2 quarts of olive oil (not extra virgin)

Sea salt to taste

Black Pepper to Taste

Red Wine Vinegar to taste

Gather ingredients

Inspect fish, look for fish with clear eyes and with an inoffensive smell, avoid overly smelly or damaged fish.

Pour olive oil into a cast iron skillet or other high sided cooking vessel and heat to approximately 350 F or 177 C.

Fry the fish in batches of 5, stirring regularly to keep them from sticking. Cook for 2-4 minutes until the fish have started to crisp. Be careful, some fish may pop and spit.

Remove fish from the oil and allow them to drain.

Season fish with salt, pepper, and vinegar and serve.

Psampisa aka Flatbread

There are many varieties of bread eaten in Korithia and grain products make up anywhere from 50 to 80 percent of an average individuals diet. This particular variety of bread is most popular in the southern and eastern portions of Korithia, whereas a fluffier yeasted loaves are more commonly eaten in the west and north. This recipe is specifically made with wheat but similar breads can also be made with barley or with mixtures. If you do not want to make this bread yourself it can be substituted with most pita breads. Bread is served with every meal and some meals may feature multiple varieties of bread.

(Note for this recipe I only had self-raising flour at hand which gives a slightly puffier bread, if this is what you want add roughly 3 tsps baking powder)

Recipe

2 1/2 cups white wheat flour plus more for surface

1 1/2 teaspoons sea salt

1 cup whole fat greek yogurt

Olive oil for cooking

In a large bowl, mix together the flour, salt and baking powder. Add the yogurt and combine using a wooden spoon or hands until well incorporated

Transfer the dough to a lightly floured surface and knead by hand for 5 minutes until the dough feels smooth.

Cover the dough and allow to sit for approximately 20 minutes

Separate dough into desired number of flatbreads.

Add flour to each dough ball with your hands and then use a rolling pin to flatten out the dough on a lightly floured surface. Size is up to taste.

Heat a pan on medium high heat. Add the olive oil and cook the flatbreads one at a time for about 2-4 minutes, depending on thickness, per side until the bread is puffed and parts of it has become golden brown.

Akuraros aka Cucumber (Salad)

While the cucumber has become a relatively popular crop within Korithian agriculture it is not native and was all but unknown to their Arkodian predecessors. Cucumbers, which actually originated in Sinria and Ukar, were introduced by Kishite invaders during the Arko-Kishite war and were subsequently adopted by the survivors of that conflict. Cucumbers are associated with health and in particular with fertility. Cucumbers are typically eaten raw or pickled. They may be used in salads or even in drinks, ground into medicinal juices. Cucumbers are additionally believed to ward off disease carrying spirits and may be hung outside of the doors of sick individuals to ward off evil entities. Cucumbers are also fed to learning sages, as they are believed to strengthen the resolve and spirit. A potion consisting of the magical herbs wumopalo and lisapalo, wine, and cucumber juice has historically been used to temporarily induce in non-sages the ability to see spirits. Dill is additionally believed to produce positive effects, thought to ward of diseases of the stomach and cancers. Dill is often used in potions which may effect the physical nature of an individual, these potions are rarely used as their effects are most often permanent to some extent.

This particular cucumber salad recipe is a favorite in the region around Kalmanati, Bokith.

Recipe

1 large cucumber cleaned

2 cloves garlic roughly chopped

2 tablespoons fresh dill chopped

1/3 cup red wine vinegar

1/4 cup extra virgin olive oil

Salt to taste

Pepper to taste

Cumin to taste

Cut cucumber into thin slices (the actual width will vary dependent on taste)

Combine cucumber and all other ingredients in a non-reactive container and mix.

Cover and store the salad for at least 30 minutes and up to 12 hours.

Serve cold

Ewisasi aka Olives

The Ewasi or olive is in many ways the center of Korithian cuisine, as it is also in Baalkes and Knosh. Olive oil is used regularly and the olive fruit is consumed at all meals of the day including dessert. Olives are cured via the use of water, vinegar, brines, or dry salt in order to remove their innate bitterness. There are hundreds of varieties of olive in Korithia alone, their taste dependent on when they are harvested, how they are cured, the particular cultivar, and even the soil in which they are grown. Kalmanati is best known for two varities of olive, the kalmi, which is red fleshed and meaty, typically cured in red wine vinegar, and the prasiki, a small green olive which is firm and slightly nutty in flavor.

Recipe

Take your favorite olives, put them in a bowl. Optionally add vinegar and herbs

Funemikiwados aka Hill Sauce

Hill sauce is the condiment of choice for most Korithian households and the exact nature of the sauce will vary greatly from region to region. In the north it is most often composed of pine nuts, olive oil, onion, vinegar, salt, and garlic. In the south the sauce is typically far more marine in nature, composed of seaweed, fish, garlic, olive oil, and vinegar. In all cases the ingredients are combined and mashed or ground to produce a pourable/dipable sauce. The sauce itself originates from the center of Korithia around the city of Bokakolis. The sauce was originally used by shepherds to flavor dried meats which may otherwise be dry or flavorless. Its name derives from the ingredients used within these early versions of the sauce, many of which were herbs plucked from the hillside while the shepherds tended to their flocks. The Kalmanatian version of the sauce is similar to this original herb based variety however it adds salt-cured fish and tisparos (Tisi - tickle, paros- seed) , another Kishite import (there it is called lisiki). This sauce is often used with practically any savory food, poured on meat, fish, vegetables, and bread. Often a house may be judged by the quality of their funemikiwados. Among the Kalmanatians there is two varieties of the sauce, a fresh version (the one described here) and another which is typically made with dried herbs and has additional vinegar added to act as a sort of preservative.

Recipe

1/2 cup extra virgin olive oil

1/3 cup red wine vinegar

2 tbsps rilogabo juice (1:1 orange and lemon)

2 anchovies (or other small salt-cured fish)

1/4 cup fresh chopped dill

1/6 cup fresh chopped parsley

1/8 cup fresh chopped thyme

6-10 leaves of fresh chopped rosemary

2-3 leaves fresh basil

2 cloves of garlic

Black pepper to taste

Ground tisparos to taste (Substitue ground sichuan pepper)

Gather the ingredients.

Combine and grind anchovies, garlic, and herbs into a fine paste, using a mortar and pestle or with a food processor.

Combine the herb paste ialong with the rest of the other ingredients and mix until completely incorporated.

Allow to sit at least 30 minutes, allowing for flavors to develop and properly incorporate with each other.

Serve with meat or fish

Wumos aka Wine

Wine in Korithia predates both the Korithians and the Arkodians, and had already been developed by several cultures on the islands including the Awaxi mentioned earlier. Wine is one of the most commonly consumed beverages, only surpassed by water, and slightly more common than psamarla, a Korithian version of unfiltered beer. Wine has many social, religious, and economic uses and is essential in the trade of the plantbrew, making up the base of many kinds of potion. There are many varieties of wine, with some being viewed as better or worse than others. Red wine is typically preferred for later in the day as it is believed that it helps to induce sleep while white wine is preferred for the morning and afternoon. Wine is typically watered down at a ratio of 2 parts water to 1 part wine, this may be either with plain or salted water. Unwatered wine is saved for special occasions and certain religious ceremonies in which intoxication is the goal. Wine may be sweetened with honey, figs, or various fruit juices. Herbs and spices such as black pepper, tisparos, coriander, saffron, thyme, and even cannabis and opium and various magical herbs may be added to change the flavor of the wine and to promote other effects.

Recipe

Pick a wine that you like and put it in a glass or cup. You can water it down if you would like but I didn't because I am not Korithian and this was a special occasion.

I finally got this post done! If you decided to read through this whole thing, thank you! Let me know if you try any of these, most of these amounts are ultimately a matter of taste, you can change things and experiment if you want.

Now we'll see if I get to 300 followers and we'll do this all over again with the food from another part of the Green Sea.

Thank you all again for following me, I've really enjoyed sharing my WIP with y'all!

@patternwelded-quill , @skyderman , @flaneurarbiter , @jclibanwrites , @alnaperera, @rhokisb, @blackblooms , @lord-nichron , @kosmic-kore , @friendlyshaped , @axl-ul , @talesfromtheunknowable , @wylanzahn , @dyrewrites , @foragedbonesblog , @kaylinalexanderbooks , @mk-writes-stuff , @roach-pizza

#fantasy food#writeblr#writing#worldbuilding#fantasy#testamentsofthegreensea#fantasy writing#world building#creative writing#story writing#200 followers#thank you guys so much!#fantasy world

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Foods from my friend's pathfinder campaign

Fish sandwich and Mysterious Shawarma

Dhampiric chocolade and Cherry Mochi

A bowl of rice and a VERY overpriced cup of tea

Peach kakigori and Hyorogan

Evil pepper moonshine and Half-dark ale

Roastbeef sandwich and Mysterious fairy powder

Roasted kobold egg and Steak made of kobold's tail

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dragon books with disability reps that don’t magically get fixed? Yeah thats what I’m talking about.

Main character loving food and enjoying cooking? Yes love it.

Dragon rider fantasy where the villain isn’t some evil king somewhere? Heck yeah.

Dragons are common in this world. Food is a common theme in this series. Several characters have disabilities. The antagonists are interesting and unique for a dragon rider fantasy. The wholesome moments.

“Holt Cook was never meant to be a dragon rider. He has always served the Order Hall of the Crag dutifully, keeping their kitchen pots clean.

Until he discovers a dark secret: dragons do not tolerate weakness among their kin, killing the young they deem flawed. Moved by pity, Holt defies the Order, rescues a doomed egg and vows to protect the blind dragon within.

But the Scourge is rising. Undead hordes roam the land, spreading the blight and leaving destruction in their wake. The dragon riders are being slaughtered and betrayal lurks in the shadows.

Holt has one chance to survive. He must cultivate the mysterious power of his dragon’s magical core. A unique energy which may tip the balance in the battles to come, and prove to the world that a servant is worthy after all.”

Books 2 and 3 have gorgeous covers too.

Book 4 cover was recently revealed and I am extremely excited to see what comes next.

#flight rising#dragons#dragon#disability representation#food#fantasy food#fantasy books#books#wholesome#ascendant#ash

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Your final course, rising moon roe nigiri. It tastes either sweet or savory depending on your mood :) . Thank you for visiting the Dreamland Sushi-ya. Don't forget, fairies eat free!

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

heres the finished image of my dnd feast illustration. Enjoy

70 notes

·

View notes