#European Quartet

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Ethereal Soundscapes of Jan Garbarek: A Journey Through Jazz

Introduction: Jan Garbarek, born seventy-seven years ago today on March 4, 1947, in Mysen, Norway, is a saxophonist and composer celebrated for his unique contributions to the world of jazz. His exposure to a wide range of music, from classical to folk, laid the foundation for his distinctive style, characterized by a hauntingly beautiful tone and a deep connection to his Scandinavian…

View On WordPress

#Dis#European Quartet#George Russell#Jan Garbarek#Jazz History#Jazz Saxophonists#Keith Jarrett#Witchi-Tai-To

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Karl Klaus (Austrian, 1889–after 1925) for Alexandra Porcelain Works, Vienna Charger, c.1911-12 Glazed earthenware w/ enamel & gilding, 15 1/2 x 1 5/8 in. (39.4 x 4.1 cm) Saint Louis Art Museum 13:2007

#animals in art#european art#20th century art#birds in art#bird#birds#peacock#peacocks#charger#decorative arts#ceramics#Saint Louis Art Museum#Austrian art#1910s#Karl Klaus#Alexandra Porcelain Works#quartet

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've spent almost the whole day preparing for a New Year's party, but inbetween I've also managed to finish this in time 🙏

First off, have a happy 2025 from both this blog and from myself! :D

If I were to give a recap of this year, I think I'd say it was quite good! I unfortunately ended up posting less than I've originally envisioned for 2024, but at least what I did show to the world were things I was quite happy with. Being fair, VROH's constant hiatus and classes getting on my ass also impacted by desire to post 🫠

For 2025 my goals will be the same for the most part; to keep working on my settings/headcanons for the "FFI Quartet" (Pictured above), aaand maybe actually finish doing the lineup for the fan-made ones. But at the end of the day, I just want to create more, y'know? 😭 These last months I have been feeling down due to some physical issues, but I like to use it as inspiration to share things to the world. Even if its something little.

On a more positive note, this year I've also noticed many new people doing FFI content, and my heart melts so much 🥺 It doesn't matter of which team, characters or ideas you have, if you got anything to share about these international kids, please do!!! Its always refreshing to see other takes on these characters than just mine ♥ Plus it makes the wait for VROH much pleasant.

My final note for this post is that the letters/numbers were all made recently, but the paper emblems for these four teams are many months old. I originally made them as a way to take some breaks from screens and just chill, but I wasn't sure which use I could give them or how to post them to this platform; till I got the idea of using it here. I'll soon post better closeups of each one.

Either way, thank you all so much for this year!! I love you all! (Or vi amo tutti, given many of my following speaks italian) 💕

#inazuma eleven#red matador#brockenborg#rose griffon#the great horn#FFI Quartet is a temporary name#...Or not 🤔#During all this time I've used Euro B to refer to RM/RG/BB in the context of European tourneys + the FFI block B#But in context of the *whole* FFI... How would I call the group?#Either way; I want to give more importance to the quartet this year too

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

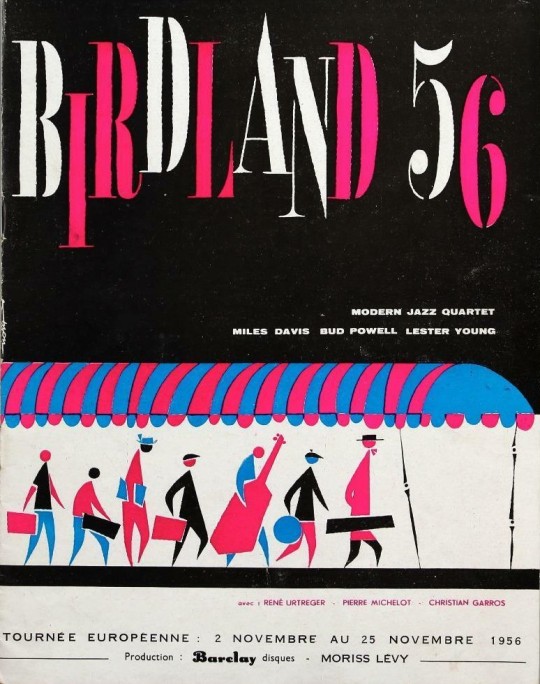

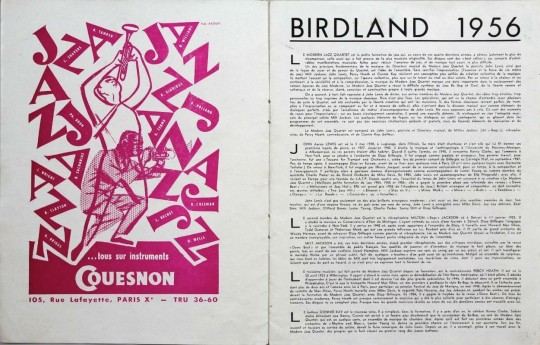

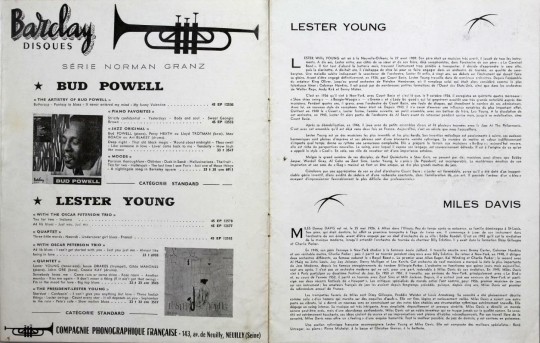

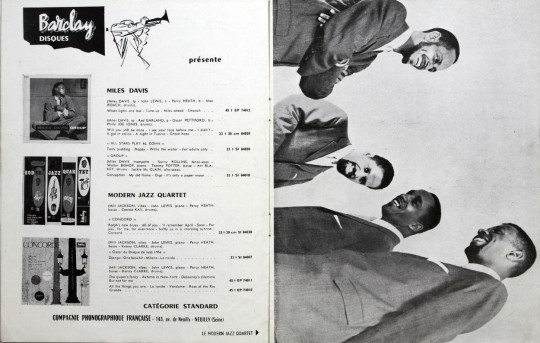

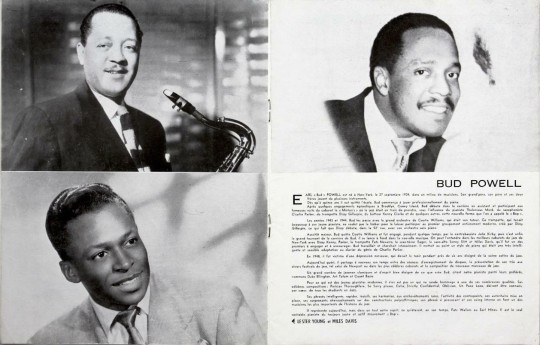

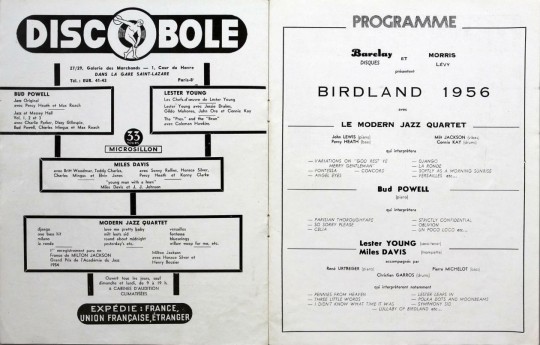

1956 - Birdland All Stars - Tournée européenne (programme en Français) - Lester Young, Miles Davis, Bud Powell, René Urtreger trio, Modern Jazz Quartet

#jazz#poster flyer#birdland'56 european tour#lester young#miles davis#bud powell#rené urtreger#pierre michelot#christian garros#modern jazz quartet#mjq#john lewis#milt jackson#percy heath#connie kay#1956

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lord help me I’ve gotten nothing done on my assignments today but I am outlining a fic that’s more like a bloody novel

#ffffffuuck#in good news though it turns out that taking a break and reading a lot DOES rekindle your creative energy and inspiration#it is too soon for me to be in another manic writing phase though. three more weeks and then i'll be good..........#anyway uhhh... if anyone is interested in another one of my ultra-specific borderline-au queer quartet adventure fics.. you're in luck!#gotta finish it before 2old2guard comes out and proves that my interpretation of quynh is completely wrong#(daydreaming in the shower all wide-eyed) this one will have the elixir of life! and lepers! and deceit! and more made-up european lords!#and will probably require a sensitivity read or two actually#been planning it for about a year but it's only now actually forming into a real story#i'm really just playing with barbies but instead of modern aus it's vaguely historical escapades huh#i could turn it into original fiction but where's the fun in that and also the fact that they're immortal is always a key element

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

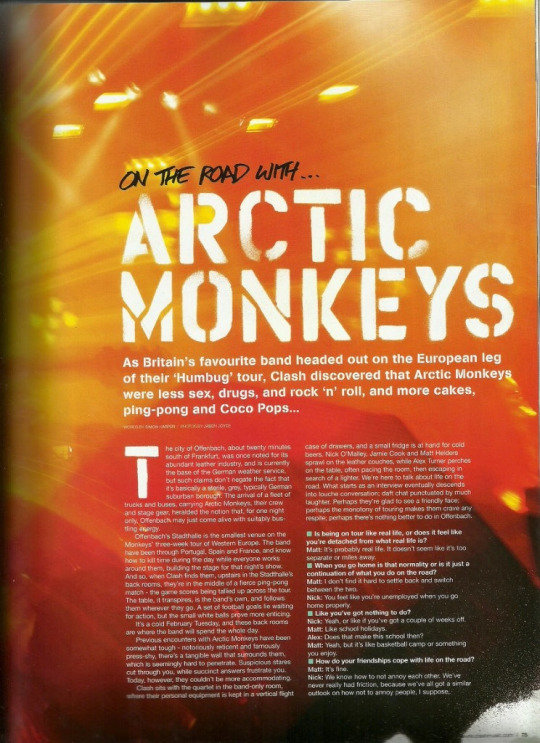

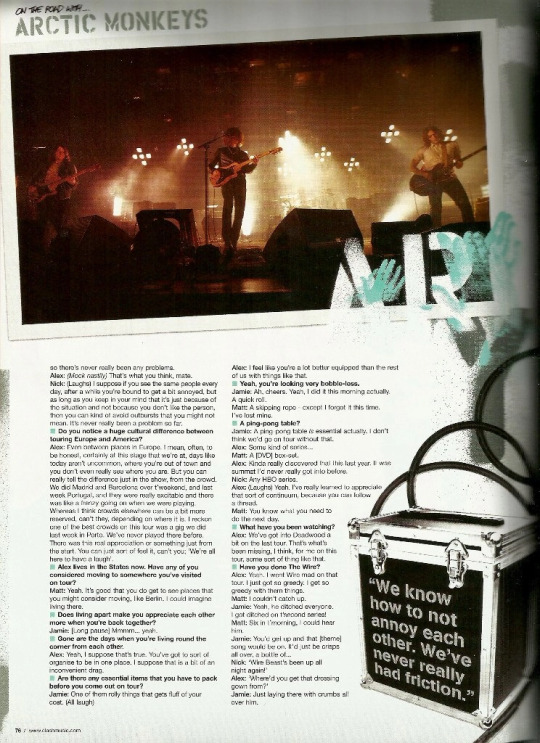

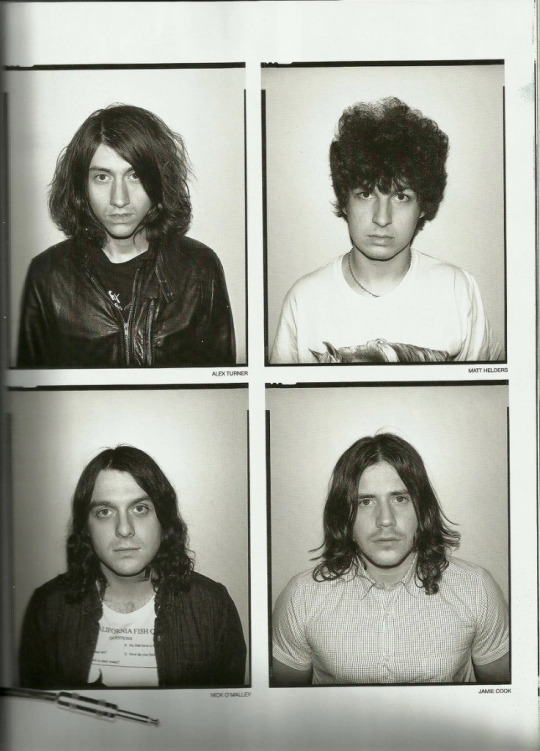

arctic monkeys for clash magazine, april 2010

ON THE ROAD WITH… ARCTIC MONKEYS

Words by Simon Harper Photos by Jason Joyce

As Britain’s favourite band headed out on the European leg of their ‘Humbug’ tour, Clash discovered that Arctic Monkeys were less sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll, and more cakes, ping-pong and Coco Pops…

The city of Offenbach, about twenty minutes south of Frankfurt, was once noted for its abundant leather industry, and is currently the base of the German weather service, but such claims don’t negate the fact that it’s basically a sterile, grey, typically German suburban borough. The arrival of a fleet of trucks and buses, carrying Arctic Monkeys, their crew and stage gear, heralded the notion that for one night only, Offenbach may just come alive with suitably bustling energy.

Offenbach’s Stadthalle is the smallest venue on the Monkeys’ three-week tour of Western Europe. The band have been through Portugal, Spain and France, and know how to kill time during the day while everyone works around them, building the stage for that night’s show. And so, when Clash finds them, upstairs in the Stadthalle’s back rooms, they’re in the middle of a fierce ping-pong match – the game scores being tallied up across the tour. The table, it transpires, is the band’s own, and follows them wherever they go. A set of football goals lie waiting for action, but the small white balls prove more enticing.

It’s a cold, February Tuesday, and these back rooms are where the band will spend the whole day.

Previous encounters with Arctic Monkeys have been somewhat tough – notoriously reticent and famously press-shy, there’s a tangible wall that surrounds them, which is seemingly hard to penetrate. Suspicious stares cut through you, while succinct answers frustrate you. Today, however, they couldn’t be more accommodating.

Clash sits with the quartet in the band-only room, where their personal equipment is kept in a vertical flight case of drawers, and a small fridge is at hand for cold beers. Nick O’Malley, Jamie Cook and Matt Helders sprawl on the leather couches, while Alex Turner perches on the table, often pacing the room, then escaping in search of a lighter. We’re here to talk about life on the road. What starts as an interview eventually descends into louche conversation; daft chat punctuated by much laughter. Perhaps they’re glad to see a friendly face; perhaps the monotony of touring makes them crave any respite; perhaps there’s nothing better to do in Offenbach.

Is being on tour like real life, or does it feel like you’re detached from what real life is?

Matt: It’s probably real life. It doesn’t seem like it’s too separate or miles away.

When you go home is that normality or is it just a continuation of what you do on the road?

Matt: I don’t find it hard to settle back and switch between the two.

Nick: You feel like you’re unemployed when you go home properly.

Like you’ve got nothing to do?

Nick: Yeah, or like if you’ve got a couple of weeks off.

Matt: Like school holidays.

Alex: Does that make this school then?

Matt: Yeah, but it’s like basketball camp or something you enjoy.

How do your friendships cope with life on the road?

Matt: It’s fine.

Nick: Yeah. We know how to not annoy each other. We’ve never really had friction, because we’ve all got a similar outlook on how not to annoy people, I suppose, so there’s never really been any problems.

Alex: (Mock nastily) That’s what you think, mate.

Nick: (Laughs) I suppose if you see the same people every day, after a while you’re bound to get a bit annoyed, but as long as you keep in your mind that it’s just because of the situation and not because you don’t like the person, then you can kind of avoid outbursts that you might not mean. It’s never really been a problem so far.

Do you notice a huge cultural difference between touring Europe and America?

Alex: Even between places in Europe. I mean, often, to be honest, certainly at this stage that we’re at, days like today aren’t uncommon, where you’re out of town and you don’t even really see where you are, as I’m sure you’re aware. But you can really tell the difference just in the show, from the crowd. We did Madrid and Barcelona over t’weekend, and last week Portugal, and they were really excitable and there was like a frenzy going on when we were playing. Whereas I think crowds elsewhere can be a bit more reserved, can’t they, depending on where it is. I reckon one of the best crowds on this tour was a gig we did last week in Porto. We’ve never played there before. There was this real appreciation or something just from the start. You can just sort of feel it, can’t you; ‘We’re all here to have a laugh’.

Alex lives in the States now. Have any of you considered moving to somewhere you’ve visited on tour?

Matt: Yeah. It’s good that you do get to see places that you might consider moving, like Berlin. I could imagine living there.

Does living apart make you appreciate each other more when you’re back together?

Jamie: [Long pause] Mmmm…yeah.

Gone are the days when you’re living round the corner from each other.

Alex: Yeah, I suppose that’s true. You’ve got to sort of organise to be in one place. I suppose that is a bit of an inconvenient drag.

Are there any essential items that you have to pack before you come out on tour?

Jamie: One of them rolly things that gets fluff of your coat. (All laugh)

Alex: I feel like you’re a lot better equipped than the rest of us with things like that.

Yeah, you’re looking very bobble-less.

Jamie: Ah, cheers. Yeah, I did it this morning actually. A quick roll.

Matt: A skipping rope – except I forgot it this time. I’ve lost mine.

Nick: DVDs, stuff like that.

A ping-pong table?

Jamie: A ping-pong table is essential actually. I don’t think we’d go on tour without that.

Alex: Some kind of series…

Matt: A box-set.

Alex: Kinda really discovered that this last year. It was summat I’d never really got into before.

Nick: Any HBO series.

Alex: (Laughs) Yeah. I’ve really learned to appreciate that sort of continuum, because you can follow a thread.

Matt: You know what you need to do the next day.

What have you been watching?

Alex: We’ve got into Deadwood a bit on the last tour. That’s what’s been missing, I think, for me on this tour, some sort of thing like that.

Have you done The Wire?

Alex: Yeah. I went Wire mad on that tour. I just got so greedy. I get so greedy with them things.

Matt: I couldn’t catch up.

Jamie: Yeah, he ditched everyone. I got ditched on t’second series!

Matt: Six in t’morning, I could hear him.

Jamie: You’d get up and that [theme] song would be on. It’d just be crisps all over, a bottle of…

Nick: ‘Wire Beast’s been up all night again!’

Alex: ‘Where’d you get that dressing gown from?’

Jamie: Just laying there with crumbs all over him.

Have you ever had any scares at customs?

Nick: I got searched yesterday actually.

Matt: It was your squeaky wheels, just as I’d said. I said, ‘Them wheels are gonna attract attention.’

Nick: In Germany. A very thorough search, but luckily no glove action.

Jamie: They probably wanted to mend your wheels for you.

Matt: ‘I’ve got summat for that, some GT85.’

Nick: They were really suspicious of me. They really took everything apart and didn’t put it back as neat as I’d put it in.

Alex: At this end, yesterday?

Nick: Yeah, when we arrived in ‘Munchen’.

Alex: They’re quite, like, strict, aren’t they, Bavarian authorities.

Nick: Yeah. They had a look at me belt, everything. All me case and bag. Took everything apart. Then he were like, ‘Where have you come from?’ I went, ‘Barcelona’. He were like, ‘Have you had any contact with drugs in Barcelona?’ I went, ‘No.’ He went, ‘What do you do?’ I said, ‘I’m in a band.’ And he went, ‘Ah’, and then, like, swabbed everything.

Alex: When I got in t’car yesterday, the fella were like, [German accent] ‘If you like to do drugs, do not try and do it in Bavaria.’

American customs scare me most.

Matt: Yeah, it’s a load of questions.

Alex: ‘What are you doing here?’

Jamie: New Zealand were quite funny. We all got pulled…

Matt: We had to sit in them chairs for a bit…

Jamie: And this guy was asking us directly the last time we ever did drugs. Then someone came over who worked for us…and he soon disappeared rather fast. We were fine. (All laugh)

Alex: I’ve come to quite enjoy the American customs people. (All laugh)

Matt: They’ve always got weird names.

Alex: They’re like, [American accent] ‘So you’re in a band, huh?’ You go, ‘Yeah, yeah.’ ‘What do you do in the band?’ ‘Oh, I’m the singer.’ ‘Yeah? You don’t look like a singer to me.’

Nick: ‘Do you sound like Coldplay?’

Alex: Yeah, ‘What kind of music do you guys play?’

Jamie: ‘Do you sound like Staind?’ I went like, ‘Staind? I know them… Fuckin’ hell!’ It took me ages. ‘Yeah, yeah, we sound a bit like Staind.’ When he said it I were like, ‘Yeah, a bit.’

You’ve said before that you wanted to try and get an album out this year. Do you get any time on the road to do any work on that?

Alex: Not really. That’s a bit of a pain in the arse, not being able to rehearse and work stuff out. I don’t think I write very good songs on t’road. They’re all a bit wonky. You get back and you’re like, ‘Hmmm’.

Does it detach you from what we were talking about earlier, ‘real life’? Does it detach you from the things that you want to be writing about?

Alex: I dunno. You can still use your imagination, but I just think, yeah, in your surroundings there’s always about to be something that’s going to happen. You can’t think. I always write wherever I am, but I dunno if the things that come out when you’re touring around always have the shelf life that the other things do.

Have you got any songs earmarked for the next album?

Alex: Yeah. I mean, there’s some ideas, but we haven’t really had the chance to get out the fine toothed comb.

‘Humbug’ was a departure in sound from your previous albums – do you think you’ll continue in that direction, maybe bring Josh Homme in again?

Alex: Not sure, really. We would like to do something with Josh again – it was terrific for us to go on that adventure – but whether or not it’s this next thing, I’m not sure. And also, like, he’s busy! (Laughs) He’s got a schedule himself, doesn’t he?

You went to record over in his place, so do you think next time you’ll have him over to...

Alex: High Green? (Laughs) Homme in High Green? I quite fancy that.

Nick: He’d look like a superhero in High Green, all the bad genetics there are in High Green. He’d look amazing.

Matt: He’d be the biggest man there.

You’ve released a couple of singles exclusively through Oxfam. What made you decide to do that?

Jamie: Laurence and Jonny at Domino came to us with that idea – a great idea for the charity reason, and then cos Woolworths and stuff had shut down, but there were always an Oxfam.

Alex: Like, in towns where there perhaps aren’t, like, an Our Price or something.

Do you have to think of more creative ways to get your records out there?

Jamie: Yeah, rather than just sat at home.

Matt: They should think about making the journey exciting – paint paths a nice colour to the record shops.

Alex: The yellow brick road.

Matt: Something that makes people want to walk to a record shop. Even if it’s just free parking. (All laugh)

Jamie: It’s just too easy to buy music now.

How do you feel as artists about the devaluing of music? Does it annoy you that you’re working hard to make something, but people can just pick it up from their friends?

Jamie: I suppose we were never in the industry when it were big money, when people used to sell twenty million albums. Has that ever happened since we’ve been around?

Probably someone like Dido has.

Jamie: Yeah, that were probably the last.

Matt: It’s like, we wouldn’t expect anything like that to happen to us, so…

Alex: I do think there is people that always will want to go and get records.

Matt: Yeah, it won’t change everybody.

Alex: I was reading a couple of months ago about there’s an idea where you won’t even have – you know like you pull songs off iTunes or whatever – but they were saying you subscribe to a database and pay to get ’em…

Jamie: Spotify, that’s what that was.

Alex: Yeah. But you can’t get them on…

It streams the music – you can’t download them.

Alex: But you can’t do that on your phone, can you?

Matt: Yeah, you can do Spotify on your phone if you pay about £10 a month. Nokia did that thing where you can just pay a monthly thing and you can have as many as you want…

Alex: The fella had a quote, he’s like, ‘There’s nothing sexy about an MP3 on your desktop’. (Laughs) He’s like, ‘There’s nothing sexy about having a subscription to a database’. (All laugh) But then you could just sort of buy a record and stand it up against your wall. Not that that’s particularly sexy, but, you know what I mean… I like things that you can stand up.

Jamie: Like you said the other day, everyone’s just gonna have an empty house.

Matt: Yeah, there’s gonna be nothing on t’shelves. Not even books now.

Jamie: No one’s got any photos anymore, no ones’s got any CDs or records…

Matt: You’ll just have a screen and a chair.

Jamie: You’ll just go, ‘Sound. This is sound.’

Matt: With nowt on your wall.

Jamie: You can just have everything [at your fingertips]; turn your fire on, open your curtains…

Alex: You’d get in it for your bath. (All laugh)

[Alex goes into the band’s equipment drawer, pulls out a giant figure of Freddie Mercury in full-on rock pose. “See, he said he likes things that stand up,” Matt says.]

Does being on an independent label give you the freedom to experiment with your marketing or promotions?

Matt: Yeah. They [Domino] have as many ideas as us for stuff like that, like the Oxfam thing. They tend to think on a similar level, and, at the same time, if we have a suggestion, they’re open to it. It sometimes is a good thing to have a label like Domino, cos they’re experienced in doing weird stuff, and have obviously signed things that aren’t necessarily to make any money or anything, so we’ll listen to them if they have a suggestion, and vice versa. They’d put records out on tins of beans and all sorts. (All laugh)

Jamie: I wanted to do it on a conifer. I wanted to put an MP3 out on a conifer.

Matt: Or just seeds. Christmas tree seeds.

Alex: Yeah. What did they actually do?

Matt: There’s a Jewish guy, I forgot what his name is, and they did it on a kosher chicken noodle soup or something. You buy the soup and you get the code [for the MP3]. Which is good in a way, because he’s just poo-pooing the fact that there’s not much point. It’s an incentive, but it doesn’t get it in the chart, you see. It’s a give-away. So you can sell anything and just have an MP3 code on it. You can sell a car and you’d just get one song.

Jamie: But then it doesn’t count towards t’charts?

Matt: No. The Oxfam thing don’t either, does it. Only the download bit does. You’re not allowed to give away incentives like free stuff, because that’s obviously encouraging people. See, that’s the thing – people might buy the soup and not download the song. ‘I wonder if they make good soup?’

Jamie: When you see a good cover sometimes…

Matt: Yeah, you buy it for the cover.

Alex: Perhaps the epitome of that is you buying a Lady Gaga picture disc. (Laughs)

Matt: Yeah, I did. I’ve been a fool.

Alex: It’s great, cos she’s wearing like a fuckin’ box of Coco Pops or something. (Laughs)

Matt: You could buy that Freddie Mercury thing and get a Queen album, for instance. You don’t need to put it on or owt.

Jamie: You want to make it awkward.

Matt: Buy a chair. Buy a flat pack piece of furniture and you get a code for an album.

Jamie: You have to put your furniture up and send a picture to someone, then they send you the MP3.

Alex: That would make a good video: playing in a bowl of Coco Pops. (All laugh) Remember that kids programme where they used to have to go swimming in a bowl of cereal…

Jamie: Ah yeah. Didn’t they used to do something like that on The Big Breakfast?

Matt: They did, yeah.

Jamie: It were a massive cup of tea and you used to have to get the sugar lumps…

Matt: Yeah, yeah, that was it: One Lump Or Two.

Jamie: One Lump Or Two, yeah!

Alex: It would be great: kid comes down, he’s having his breakfast – Coco Pops – and then, like, Arctic Monkeys are in his cereal. (All laugh)

Jamie: Hot milk, though.

Matt: Hot milk in t’afternoon.

Alex: (Laughs) ‘Why not try Coco Pops after school?’

Jamie: (Laughs) I love that advert!

Alex: It’s the best!

Do your fans give you CDs of their bands?

Matt: They throw them on t’stage! Imagine if you got one of them in t’eye! Fuckin’ hell! Remember in America, a kid got on stage and he had a handful [of CDs] and someone had to grab him to get him off, but he threw them. So he were getting pulled away and he threw them.

Alex: I’ve been getting less CDs though…

Matt: Now they’re throwing download cards at you!

Alex: I got a pair of underpants…

Jamie: People are chucking downloads at you. You’re like, ‘What the fuck?’

Matt: People are throwing zeroes and ones at you – it’s like the credits of The Matrix!

Jamie: You can’t get any flick on a download.

Alex: They’re chucking Spotifys at me. Maybe that’s what them pants were – some sort of code.

I think it’d be a totally different sort of code! Do you listen to the music that fans give you?

Matt: I listened to one that someone gave me the other day. It just were at home though, he just gave it me.

Alex: No more than I’d wear that pair of pants! (Laughs)

Matt: It were just convenient – I were getting in me car and there’s a CD player there.

What’s the strangest thing a fan has given you?

Matt: Just in Japan – everything you get is weird! Like, a monkey hat – it left your own face in but it’s got ears and a tail.

Jamie: And sweets.

Matt: A lot of sweets.

Jamie: We once said, ‘Oh, we like these sweets’ in an interview…

Nick: There’s someone that makes baked goods.

Matt: You got a good one, where it were like a picture of you…

Alex: Yeah, I got like a diagram of myself…

Matt: A diagram, pointing at every bit, and then asking to fill in, like, what his favourite brand of jeans were.

Alex: Hand it back, and then she’d sort of kit me out.

Matt: She’d buy it all! So, like, ‘Favourite shoes? Trainers or boots?’ It would be like that. He’d fill it in and send it back and then she’d buy it. ‘Will this do?’

Alex: Back it came with this jumper that were perfect actually. She really knew me better than I knew meself.

Nick: With baked goods, I know it’s not [spiked], but you never know… It’s probably fine – it’s more than likely fine – but it is a gamble.

Matt: It’s innocent, but someone might have seen that opportunity.

Jamie: I don’t think I’m ever gonna eat a baked good that some stranger’s made. You learn about that. There is a story there…

What’s the first thing you do when you get home after the tour is finished?

Nick: See your friends and family that you’ve not seen.

Matt: I go and get my photos developed. That’s actually one of the first things I do.

Alex: I usually pick up me guitar. Honestly. It’s a deep breath.

Later that evening, Clash is back in the ping-pong room. The tour manager comes to break bad news to the band - the curtain at the front of the stage is broken. They won't be able to make their usual grand entrance. "Ah, we've got to do it," grins Alex. Do what? "We've been saying on this tour if ever the curtain doesn't work, we've got to go on to this song." Which song? "Black Eyed Peas’ ‘I Gotta Feelin’’," Alex beams. The band are giddily bouncing around, electrified by the prospect of taking the stage to the song that's soundtracked many a menopausal vodka-stained Saturday evening's preparatory gathering.

“But when do we go on?" Matt asks.

"The rap. We gotta wait for the rap," Alex asserts.

"We should wait until "Mazel tov”,” Jamie smirks.

Ten minutes later, Clash is amidst the Offenbach crowd when the lights go out and the song bursts from the PA. A wave of euphoria swells, the irony not lost, and right on cue, just as the Peas declare, "I know that we'll have a ball", the four Monkeys stride towards their instruments.

The nineteen-song set covers their three albums - with Nick Cave's 'Red Right Hand’ thrown in for good measure. The last song before their encore is 'Secret Door’ from 'Humbug’. Just as Matt cracks the snare drum that launches the song's long psychedelic outro, cannons on the roof blast out gold and silver confetti over the joyous crowd below, proving that the Monkeys aren't averse to a bit of showmanship every now and then.

The after party is a subdued affair (well, in Offenbach it's bound to be!), with just the band, some friends, crew, and Clash, diving into the beer and nibbles on offer. A fairly drunken chat with Alex about Johnny Cash, Billie Holiday and Gram Parsons rounds off our time with the band, as they retreat back to the confines of their bus, about to depart for Dusseldor and their next gig.

Such a welcome and warm atmosphere is often rare backstage, especially with a band as celebrated as this, but the Monkeys - ever changing and ever surprising - are beginning to make a habit of defying expectations. Growing up has never been such fun.

#arctic monkeys#alex turner#matt helders#nick o'malley#jamie cook#humbug era#clash magazine#interviews#not my scans#bands#screenshots from vk#in another universe they wouldve started a four white men talking podcast#eye contact#my image id

190 notes

·

View notes

Note

May I have thy opinion on the old man quartet? (Byron/Mortis/Gray/Chuck)

Married.

Honestly I love the dynamic, I don't care if they're husbands or good pals, these four have my heart‼️‼️

I love them all together or separated. Although I may have a preference over Byron x Mortis (I remember the first time I was in this fandom like 2020-21, these two were my parents) and Gray x Chuck. BUTTT I'd like any combination or them just kissing together lol.

Okay, now I'll give some HCS about this poly-relationship:

-Byron calls all of them "twats"

-Mortis, Gray and Chuck are latin European while Byron stands there with his English-Germanic accent lmao (he's very bullied lmao)

-Chuck and Mortis are the most extroverted in that relationship. (They're so chaotic)

-Meanwhile, Gray and Byron are very calm and quiet. They usually drink tea together.

-They all have rings with a gemstone. (Byron has an emerald, Mortis has an amethyst, Gray has a ruby and Chuck has a yellow zircon)

-I don't care, I know they all smoke. Especially Nobel, Winston or Virginia.

#brawl stars#fanart#brawl stars fanart#brawl stars chuck#brawl stars gray#brawl stars mortis#brawl stars byron

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not gonna lie, Juno was a hard one to design for. Unlike the other Quartet, she doesn’t have any objects she’s uniquely associated with, and her main canon attribute is being an acrobat 😂 Even her Greco-Roman counter part was a bit of a challenge. Hera/Juno is the patron goddess of marriage, and some people claim calla lilies are associated with her. However, I find this a bit of a stretch, as calla lilies originate from southern Africa and was first described by European botanists in the 18th century 🤣

In the end I tried to show case Juno’s acrobatic abilities with a dynamic pose. I tried to incorporate peacock colors for the background as Hera was associated with peacocks. And though the “myth” of calla lilies originating from Hera/Juno might be just that, a myth someone cooked up, their long stems do remind one of Juno’s rather unusual hair style 😉

97 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Béla Bartók

Béla Bartók (1881-1945) was an innovative Hungarian pianist and composer most famous for his classical works for piano and orchestra, string quartets, and songs, many of which present traditional Hungarian and other European folk themes. Bartók, a prodigious scholar and collector of folk songs, is widely considered one of the greatest musicians Hungary has ever produced.

Early Life

Béla Bartók was born on 25 March 1881 in Nagyszentmiklós (now called Sânnicolau Mare), then located in the Hungarian part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (but today located in Romania). Béla's father was a teacher in the local agricultural college, and his mother was a piano teacher. Béla's father died when he was seven years old, and so mother and son moved to Pressburg (called Pozsony by the Hungarians), today's Bratislava in the Slovak Republic. Béla's mother taught him to play the piano from the age of five. He showed a rare talent and was already performing in public by the age of eleven; he had started composing his own pieces even earlier, at the age of nine.

Béla turned down a free scholarship to study at the music academy in Vienna and instead decided to attend the Royal Hungarian Academy of Music in Budapest from 1898. Bartók graduated in 1903. First earning a living as a concert pianist, from 1907, Bartók worked as a piano professor at the Academy. Although the post gave Bartók some financial stability, it was not quite what he had hoped for; he remarked that he was, in truth, "a reluctant teacher and would have preferred a research post" (Steen, 722). Bartók continued to compose, with early influences coming from the works of Franz Liszt (1811-1886), Johannes Brahms (1833-1897), Richard Strauss (1864-1949) – particularly his symphonic poem Also sprach Zarathustra –, and Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971).

Bartók's character and drive is here summarised by the music historian H. C. Schonberg:

Bartók was a tiny, frail man with explosive psychic force, prepared to go his own uncompromising way even if his music was never played. A stubborn integrity and an all-encompassing humanism animated the man, and he would not swerve from his ideal of truth.

(656)

Béla Bartók, 1903

Unknown Photographer (Public Domain)

Continue reading...

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

quartet night's schtick is "haha we don't go well together" and yeah a lot of characters comment on it

one thing i love about qn is how they look like they belong in completely different franchises, especially ai and camus lol. we have a sci-fi, impossibly high-tech robot and a european fantasy character who uses magic

#yet they complete each other!!#i want to make a post about each qn relationship#utapri#quartet night

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lee Konitz: The Eternal Innovator of Jazz

Introduction: The jazz world is filled with instrumentalists who have left indelible marks on the genre, but few have maintained the breadth of creative exploration throughout their careers like Lee Konitz. Born ninety-seven years ago today on October 13, 1927, in Chicago, Konitz became one of the most influential alto saxophonists in jazz history. He was a central figure in the birth of cool…

#Benny Goodman#Bill Frisell#Birth of the Cool#Charles Mingus#Charlie Parker#Chet Baker#City of Glass#Elvin Jones#European Episode#Gerry Mulligan#Gil Evans#Jazz History#Jazz Saxophonists#John Lewis#Johnny Hodges#Kenny Werner#Lee Konitz#Lee Konitz Plays with the Gerry Mulligan Quartet#Lennie Tristano#Live at Birdland#Live at the Berlin Jazz Days#Martial Solal#Michel Petrucciani#Miles Davis#Organic-Lee#Paul Bley#Stan Kenton#Warne Marsh

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

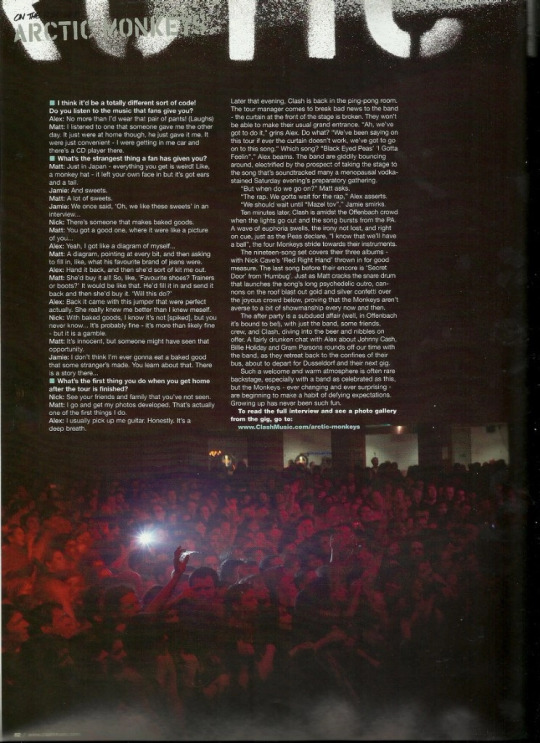

Quincy Jones

Musician, producer and arranger who had global hits with Michael Jackson, was the first black composer to find acceptance in Hollywood and won 28 Grammys

From the 1980s onwards, Quincy Jones, who has died aged 91, was best known for his production and arranging work with Michael Jackson, not least because his efforts on Jackson’s album Thriller helped make it one of the bestselling albums in pop history. But the superstar glare surrounding his work with Jackson tended to conceal the fact that there were many more layers to Jones’s abilities.

He worked with jazz stars such as Count Basie and Dizzy Gillespie, became a friend and collaborator of Frank Sinatra, and developed a flourishing career as a composer of soundtracks for film and TV. He enjoyed success under his own name in styles ranging from big-band jazz and swing to pop, soul and funk. He became an influential music business executive, a successful entrepreneur in film and TV production and launched the music magazine VIBE.

He was born in Chicago, the son of Quincy Jones Sr, a carpenter and semi-pro baseball player, and his wife, Sarah (nee Wells), a building manager. His parents divorced, Quincy Sr remarried, and the family moved to Bremerton, Washington, during the second world war, then to Seattle. Quincy Jr began playing the trumpet and singing in a gospel quartet at the age of 12, and when he met up with the teenaged Ray Charles, also based in the Seattle area, Charles encouraged him to take an interest in arranging. A course at the Berklee College of Music in Boston set Jones up for his first professional job, in 1951, with the bandleader Lionel Hampton.

His experiences on the road with the Hampton band were an eye-opener. “You couldn’t stay in white hotels, and to me, coming from Seattle, a lot of this stuff was like a slap in the face,” he said. “Back then, all the black bands had white bus drivers so they could eat, ’cos you couldn’t go into white restaurants. Even in Philadelphia, they had segregated hotels.” Jones left Hampton in 1953, having accompanied the band on a European tour and rubbed shoulders with a remarkable lineup of musicians including the trumpeters Clifford Brown and Art Farmer.

He set about making a living writing arrangements for jazz luminaries including Basie and Tommy Dorsey. Although Jones put in a stint as musical director for Gillespie’s ensemble in 1956, he was aware that the days of the big bands were numbered, and rock’n’roll was coming. “In a funny way, Lionel Hampton was one of the bands that was serious with a rock’n’roll sensibility, before we even knew what the word meant,” Jones said.

During 1957 and 1958, Jones based himself in France and Scandinavia. He continued to study composition – notably with Nadia Boulanger, mentor of Leonard Bernstein and Aaron Copland, among others – and took a job with Barclay Disques, the Paris-based subsidiary of Mercury Records. While in Europe he formed a star-studded big band of his own, and spent two years touring Europe and the US. He wrote material for Count Basie, and during the late 1950s and early 60s worked as an arranger and music director on recording sessions for vocalists including Billy Eckstine, Ella Fitzgerald, Dinah Washington and Sarah Vaughan.

In 1964, Jones won his first Grammy award, for his arrangement of Basie’s song I Can’t Stop Loving You. He also produced four million-selling singles for Lesley Gore, including the US chart-topper and UK Top 10 hit It’s My Party (1963). His hectic career was matched by an equally eventful private life. In his memoir Q: The Autobiography of Quincy Jones (2001), he described how at one point he was dating five women at the same time.

His burgeoning profile was boosted by collaborations with Sinatra, Sammy Davis Jr and Andy Williams. Jones’s association with Sinatra produced the albums It Might As Well Be Swing (1964) and Sinatra at the Sands (1966), both featuring Basie’s band. Jones and Sinatra became close friends, Jones later writing that Sinatra was “hip, straight up and straight ahead, and above all, a monster musician”.

Jones’s track record gained him entry into the lucrative fields of film and television, and he became the first black composer to find acceptance within Hollywood. Throughout the late 60s and 70s he was commissioned to write scores for more than 30 movies and hundreds of TV shows. Among his better-known film projects are In Cold Blood (1967), In the Heat of the Night (1967), The Italian Job (1969) and The Getaway (1972). The theme from Ironside is his most instantly recognisable effort for the small screen, but his compositions for The Bill Cosby Show, Sanford and Son and his Emmy-winning work for the miniseries Roots proved enduringly popular.

As the 70s wore on, Jones displayed his instinct for moving with prevailing musical trends by immersing himself in funk and disco music. His album Body Heat, from 1974, featured the Brothers Johnson as the rhythm section, and Jones subsequently produced bestselling albums by the Brothers Johnson themselves.

Despite undergoing surgery to deal with twin brain aneurysms in 1974, Jones continued to work at a furious pace. He produced chart-busting albums for the disco queen Donna Summer and soul diva Aretha Franklin, and he found another musical soulmate in the guitarist George Benson. Their collaboration on Give Me the Night (1980) – the debut release on Jones’s Qwest label – was another career benchmark, the album reaching No 3 on the US album chart while the title track was a No 4 single.

Meanwhile Jones had hits under his own name. He had a US Top 30 success with Stuff Like That (1978), and in 1981 scored a Top 10 album with The Dude, which spun off the Top 30 hit Ai No Corrida (No 4 in the UK), and the Top 20 hits Just Once and One Hundred Ways, both featuring James Ingram. In 1998, the hit movie Austin Powers prompted a revival of Quincy’s 1962 hip-shaker, Soul Bossa Nova; it was also used as a theme for the 1998 football World Cup in France.

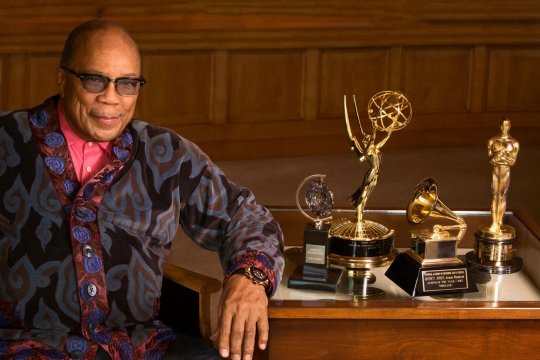

Jones first met Michael Jackson, then aged 12, at Davis Jr’s house, but it was not until Jones was working on the soundtrack for the film The Wiz (1978), starring Jackson and Diana Ross, that he was invited to produce a Jackson solo album. This was the 20m-selling Off the Wall (1979). Their collaboration continued with Thriller (1982) and Bad (1987), the trio selling 100m copies between them. In between, Jones was also the natural choice to produce the 1985 charity single, We Are the World, co-written by Jackson and Lionel Richie and performed by the all-star USA For Africa to benefit Ethiopian famine victims.

Jones was a pivotal figure in helping musicians take control of the business side of their work. Like most other musicians, he had grown accustomed in the early years of his career to having his royalties and copyrights appropriated by unscrupulous publishers or record labels. “If you write a song, the publishing is 50% of that,” Jones explained. “They would say: ‘I want 50% of your creation’, so that means you get 25%. That was normal.” He began to see the light when he took a job as A&R man at Mercury Records in New York in 1961. Within two years, he was made a vice-president, making him the first high-level black executive of a major record label. “I’d lost so much money when I had my band [the Jones Boys] in Europe that I had to go with a record company. That’s when I said: ‘I’d better pay attention to the other side, because it is a music business.’”

After moving from Mercury to A&M Records he launched Qwest, which became home to such varied artists as New Order, Milt Jackson, the Winans and Tevin Campbell. Qwest also did excellent business with the soundtracks to Malcolm X (1992) and the rap-generation movie Boyz N the Hood (1991).

Growing into the role of entertainment mogul, Jones co-produced Steven Spielberg’s film of The Color Purple in 1985 and produced its soundtrack. In 1990 he teamed up with Time Warner Inc to form Quincy Jones Entertainment; in 1991 he helped create the NBC television series The Fresh Prince of Bel Air, which launched Will Smith on the road to superstardom; and in 1993 he set up VIBE. He headed a consortium of businessmen that formed Qwest Broadcasting, which purchased TV stations in Atlanta and New Orleans.

Jones won an Emmy, 28 Grammys and three Special Grammy awards, including the Grammy Legend award in 1992, was given the Sammy Cahn lifetime achievement award from the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1989, and was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2013. He was showered with honorary doctorates, Time magazine declared him one of the most influential jazz musicians of the 20th century, and in 1990 he was made a chevalier of the Légion d’honneur, promoted to commander in 2001.

He was celebrated in the film Listen Up: The Lives of Quincy Jones (1990) and the documentary Quincy (2018), directed by his daughter Rashida.

Three marriages ended in divorce. He is survived by a daughter, Jolie, from the first, to Jeri Caldwell; a daughter, Martina, and son, Quincy, from the second, to Ulla Andersson; two daughters, Rashida and Kikada, from the third, to Peggy Lipton; and by a daughter, Kenya, from a relationship with Nastassja Kinski, and a daughter, Rachel, with Carol Reynolds.

🔔 Quincy Delight Jones Jr, musician, producer, composer and arranger, born 14 March 1933; died 3 November 2024

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ghostbusters AU with European Quartet

👻

#hetalia#hws hungary#hws poland#hws czechia#hws slovakia#hws#my art 2022#aph poland#aph czechia#aph slovakia#aph hungary

187 notes

·

View notes

Text

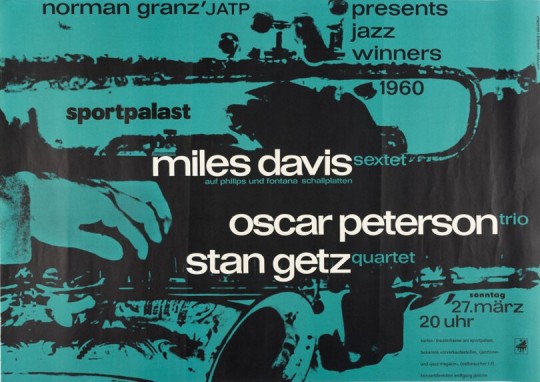

Jazz Winners 1960 - JATP European tour: Miles Davis Quintet + Stan Getz Quartet + Oscar Peterson Trio - Sportpalast in Berlin.

#jazz#poster flyer#miles davis#john coltrane#wynton kelly#paul chambers#jimmy cobb#oscar peterson#stan getz#jan johansson#ray brown#ed thigpen#1960#jatp

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

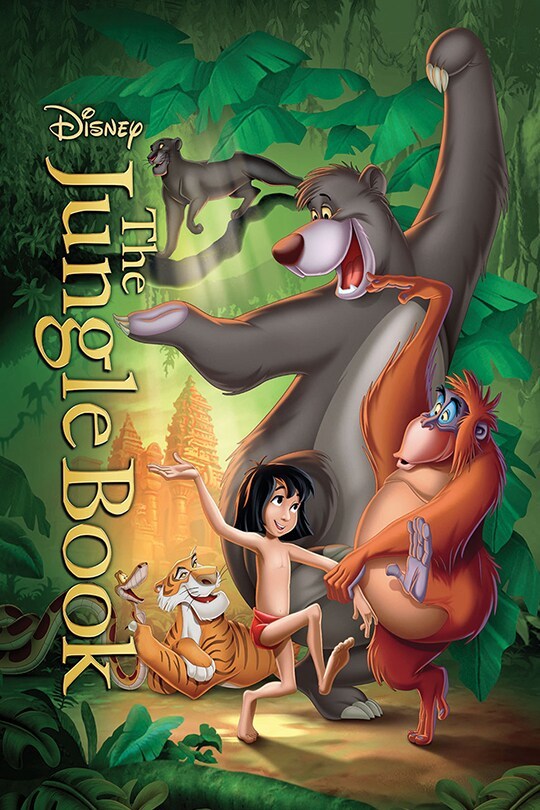

The Jungle Book (1967)

The Jungle Book is a wonderful coming of age animated musical film that follows Mowgli as he learns to grasp his identity of man. The music in this film is a combination of a rich score, songs lacking in cultural authenticity, and a framed structure that is easily interpreted.

In what ways does the film’s score situate the story with its narrative context?

Because the film is a coming of age story, while situated within a dangerous jungle where Mowgli's life is at stake, the score is composed of jazz that communicates four main emotions. Those are mystery, danger, curiosity, and happiness. Mowgli, making his way through the jungle with the help of Baloo and Bagheera, is either in a mysterious situation, in a dangerous situation, filled with curiosity, or completely blissful. This is communicated through the score which establishes that the jungle is a mysterious and dangerous place. It then goes on to communicate when Mowgli is not in danger and exploring or filled with happiness. The opening credits that show the darkness of the jungle combined with the mysterious score perfectly set the scene for Mowgli's trek through it.

youtube

How do songs use character performance to push cultural authenticity in the film’s diegesis?

The cultural authenticity in this film is lacking. Even though the film takes place in the jungles of India, the style of music performed by the characters and executed in the score is composed of jazz, Dixieland jazz, barbershop quartets and pop. Other than the small uses of snake charming music, which originates from India, the styles are all American or European. Although the film lacks this crucial cultural authenticity, the performances of the characters are upbeat which through the genre of the music, makes a fun film. The "Trust in Me" number, in which Kha the snake hypnotizes Mowgli, is a standout use of culturally authentic music to craft a scene of danger which leads Mowgli down his path of mistrusting everyone. After this plot point, Mowgli realizes he has to have his guard up at all times and additionally, he cannot rely on anyone to save him from Shere Khan.

youtube

In what ways does the film use musical "framing" to structure the score within familiarized styles?

The structure of the films score progresses from mystery and intrigue in the beginning, to curiosity and happiness in the middle, to danger and fear in the ending. This structure helps progress the narrative of the film and encompass the many emotions Mowgli feels as a result of the situations he's in. This rising and falling of conflict reflected in the score helps structure the film and relates to other styles as it is easily understood. In the final fight scene amongst Mowgli, Shere Khan, and Baloo, the dramatic crashes of the jazz score aid the emphasis on the climax.

youtube

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

what are/were the main colonial powers in the novomund? i remember morrack in the arcabil, vascony in ambrosia, provence in new provence and britain in british mendeva. but i don't think we know much about cappatia yet

Thanks for the great question! I'll take this opportunity to compile a bunch of the placenames I have for Mendeva and Cappatia [the Americas]. I'll go roughly from north to south.

The Novomund (briefly)

This term Novomund for the great landmasses of the western hemisphere is attested from the early sixteenth century, reflecting a univerbation of latin novus mundus "new world".

Mendeva [North America]

The name Mendeva was formed backwards from Latin Mendevalēnsis "from Mendeva", attested already on the maps made during the 1471 Landfall (the demonym was later rederived as Mendevānus "Mendevan" from the placename). This comes from Vask [Basque] mendeval "west", itself likely a borrowing from Vascon vent de val "valley wind".

Ambrosia [~Quebec, the Maritimes, New England] is a Vascony-settled polity named for King Ambrose III of Vascony (r. 1456–1518).

Zangathy [~the Dakotas, Minnesota, Iowa, Wisconsin, Winnipeg, Ontario] is a landlocked polity occupying the upriver Bahassassin [Mississippi] directly west of the Five Seas [Great Lakes]. Its name reflects Daccotan [Dakota] zaŋathi "flint region".

New Provence [~New England, New York, and south as far as South Carolina] is a coastal polity extending westward to the Sturgovan Mountains [Appalachians] which grew from a series of trading post established by Provence merchants.

Hasiny [~Louisiana, Texas, Mississippi, Arkansas, Oklahoma] is the largest polity in so-called British Mendeva, a few states along the Gulf settled by the Kingdom of Britain [~Wales, etc]. It takes its name from the Ractish [Caddo] name Hasíne "our people" for one of the previous nations the modern polity is descended from.

Taisha [~Texas, Coahuila] is a minor polity of Gulf Mendeva at the crossroads of British and Morrack [Moroccan] influences. Its name comes via Arabic Tayisha' from Ractish taísha' "welcome".

Mivock [~northern California] is a minor coastal polity on the Lovaqua [Pacific] known for its congenial climate. Of exceedingly sundry influence, its name reflects the name miwoc of the local Mendeva peoples and languages.

Mashick [~Mexico, southern California, New Mexico, Arizona] is the largest polity in Lower Mendeva, the descendant of the Mashick [Aztec] Empire with heavy Morrack influence. Its name derives via Arabic from the Nawat [Nahuatl] meshi'ca' "Mashick people".

The Arcabil [~the Caribbean] are a collection of islands in the Atlantic, east of Mashick. They have a complicated history of influences from various Vetomundine powers. The name probably comes via the Arabic cognate of "archipelago".

Cocain [~Cuba] is the largest of the islands of the Arcabil. Its name comes from the European folk tradition of a "land of plenty" (compare pays de Cocaigne, país de Cucanna, paese della Cuccagna).

Cappatia [South America]

European languages take the name Cappatia of this continent from Latin Cappātia, which comes via Arabic from Run'allo [Quechua] cappacha "this world".

Tavancy [~Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Boliva, northern Chile] is major polity on the western coast, descended from the Tavancine [Inca] Empire. Its name comes from the Latin imperium tavantīnum, which was borrowed via Arabic as a partial calque from the Run'allo tawantin-suyu "the quartet of provinces".

Staddomains, rather small polities, dot the eastern coast. These grew out of individual trading posts and have many different influences. Examples abound from Dutch influence in Neuwillem, Parnaven and Waronøu to Borlish influence in Monçating.

Dowahine [~southern Patagonia, Tierra del Fuego] is a minor polity at the southern tip of Cappatia. Its name comes from the Arabic word for "smoke", after the smoke-towers sighted there by Captain al-Casmi in 1513.

11 notes

·

View notes