#Demosthenes Athenian General

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Demosthenes the Athenian General - a Few Notes

I don't know if anyone cares, but - there's so little out there about Demosthenes' background and life outside of his actions during the Arkhidamian War that I thought it might be worth sharing what I've learnt recently.

It's only because I'm currently researching the lives of both Demosthenes (the orator makes my research life so freaking vexed) and Thucydides the historian that I stumbled across the interesting tit-bit that there's a possible familial connection between them.

I've spent some time since tracing down the actual source for this belief and this is the footnote that is most often referenced:

‘He [Thucydides] may even have been connected to Demosthenes by marriage, since a "Θουκυδίδης Ἀλκισθένους Ἀφιδναῖος· [Thucydides Alkisthenous Aphidnaios]" (the patronymic [Alkisthenous] and deme [Aphidnaios] are the same as those of Demosthenes) is attested in an inscription from the second half of the fourth century.'

[From Individuals in Thucydides by HD Westlake, p.97.]

This is the specific inscription: IG ii2 1678. Line 31. I couldn't find a translation of the whole inscription, so I remain uncertain what this document actually is.

If we follow this lead, and assume that Demosthenes was related to Thucydides, then we can perhaps add some interesting, Thracian, flavour to his background.

Kimon's father was Miltiades, but his mother, Hegesipyle, was a Thracian by birth, the daughter of Kong Oloros, as we read in the poems of Archelaus and Melanthius addressed to Kimon himself. This also explains why the father of Thucydides the historian, who was related by birth to Kimon's family, was called Oloros, since the father took the name from the ancestor, and owned gold-mines in Thrace. He is said to have died there too, murdered in a place called Scapte Hyle, but his remains were brough back to Attika and one is shown his tombstone in the Kimoneia alongside the grave of Kimon's sister, Elpenike. Thucydides however was from the deme Halimus, while Miltiades was from Laciadae.

[Plutarch, Life of Kimon. 4]

I have much further to go with all this (everything - the thinking, the ever enlarging sea of things I don't know, the things I should read, the facts or theories I need to process...) - but these two excerpts already suggest interesting perspectives to me - especially around Thucydides' approach to/ writings about Demosthenes' career (which is a whole thing that is blowing my mind lately); but also Thucydides' connection to Thrace/the north, and how that might have affected his feelings at Eion when he was facing Brasidas.

May the gods grant me enough years.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Demosthenes: Athens’ Fierce Voice Against Macedonia

Demosthenes (c. 384–322 BCE) was a powerful Athenian statesman and orator who passionately opposed the rise of Macedonian power under King Philip II. Renowned for his stirring speeches, he became one of ancient Greece’s greatest patriots, defending Athenian democracy against Macedonian expansion. His surviving speeches are still celebrated today for their rhetorical power and historical insight.

Key Facts

Lived from approximately 384 to 322 BCE in Athens.

Known primarily for opposing Macedonian King Philip II.

Famous for his influential and passionate speeches.

Not to be confused with an earlier Athenian general of the same name.

His oratory helped shape Athenian political resistance.

Considered among the finest ancient Greek rhetoricians.

Historical Context

Demosthenes lived during a period when Macedon was growing stronger and threatening the independence of Greek city-states, especially Athens. Philip II’s military conquests and political maneuvers aimed to unify Greece under Macedonian control, challenging the traditional power balance.

Historical Significance

Demosthenes symbolizes the fight for Athenian freedom and democracy in the face of Macedonian dominance. His speeches rallied Athenians to resist Philip’s expansion and remain politically independent. Beyond politics, his works have influenced the art of rhetoric and public speaking through the centuries.

Demosthenes’ legacy endures not just as a political figure but as a master of persuasion, reminding us how words can powerfully defend liberty.

Learn More: Demosthenes

#HistoryFacts#History#Phocion#Nicias#GreekGovernment#Demosthenes#BattleOfChaeronea#AthenianDemocracy#WHE

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

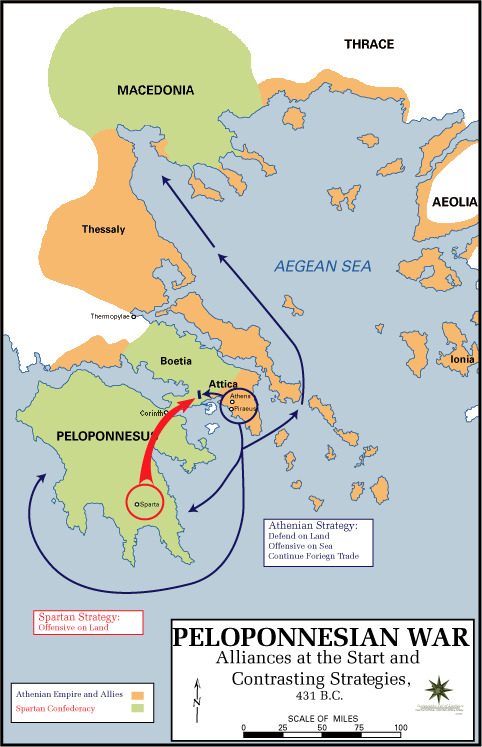

What, in your personal opinion, would you say are the main mistakes made by Athens during the Pelopennesian War? What could they have done to win?

This is not my area of expertise at all (I would recommend @warsofasoiaf or Bret Devereaux) so I'm going to be going back to the couple of classes I took on ancient Greece in my undergrad days.

I would argue that the Athenians' initial defensive strategy under Pericles and then its more aggressive successor under Cleon and Demosthenes was in general quite successful against the Spartans. The Battle of Amphipolis was very much a close-run thing that still resulted in Athens being able to challenge Spartan hegemony on the Peloponnese for the first time.

However, I think Alcibiades was the most significant factor in the Athenian defeat. Having squandered Athens' opportunity to crack Spartan land power at Mantinea, Alcibiades went all-in on his Sicilian expedition - and then promptly defected to the Spartans, fracturing Athenian political unity. The Sicilian expedition all but destroyed Athens' naval hegemony, and even after they were able to somewhat recover, the mounting losses and internal conflict meant that Athens could not fight both Sparta and the Persians at the same time.

37 notes

·

View notes

Note

Dr. Reames!! Oftentimes I see it mentioned that Alexander’s Persian campaign was framed at the time as a revenge against Persia for previous wars against Greece. And so, for example, the burning of Persepolis could be interpreted as payback for the burning of Athens.

But how accurate is that actually? I can only suppose that the top echelons of the Macedonian military establishment didn’t really feel that strongly about Greece as a whole (as Greece wasn’t a unified country like today), but had to frame it as such to disguise what could be seen as a shameless offensive land grab.

Even so, Alexander knew his propaganda. Was there a general feeling among the people of Greece and the rank and file troops that this campaign was a revenge for the previous wars Persia waged against Greece? Some sort of unifying spirit, ideal? And Alexander exploited this for his benefit? Or is this idea of a Greece vs Persia conflict a complete fabrication of misinterpretation?

Alexander's Conquest as "Revenge Campaign"

The idea of a “Revenge against Persia” campaign was part of 4th century political discourse before Alexander, or even Philip. The question was who would lead such a campaign? Naturally, Athens thought they should, but after their defeat in the Peloponnesian War, didn’t have the military mojo. And even if Sparta had opposed the Persian invasion (alongside Athens), she owed her success in the Pel War to Persian assistance, so that was a problem. Thebes as a potential leader was even worse, as she’d Medized (went over to the Persians), so hell-to-the-no would she be appropriate.

Isokrates was probably the first to suggest it be Philip, as his star was rising. Yes, Macedon had also Medized, but Alexander I had been a clever man who played both sides against the middle and was able to burnish his rep after the war as “having no choice, and see? I helped Athens by providing her with timber for the Greek fleet”…if at, we’re sure, a substantial sum that benefited Maceon. But Macedon resented Persia too and had been a victim! It provided the plausible deniability needed to elevate Philip as leader of the Go-and-get-Persia campaign.

Of course Athens was not keen on this. She still thought SHE should be leading the vengeance war, as she won the two most significant battles of the Greco-Persian Wars (Marathon in #1 and Salamis in #2). That Philip was out-maneuvering her at every turn for the hegemony of greater Greece was additionally galling.

When Philip decided to invade Persia is a point of great contention, but I think he had it in mind by the time of his extensive Balkan campaign (c. 341/40/39. when Alexander was left in Pella as regent). Much of that was to secure the Black Sea coast and conquer Perinthos and Byzantion (Athenian allies) in order to secure a bridgehead to Asia. He may have believed that the Athenian Isokrates’s oration letter to him was indicative that Athens could be won over as an ally, in order to provide the ships he needed but didn’t have. He knew Demosthenes a problem, but may not have believed fear of/resentment against Philip himself would unite Thebes and Athens (inveterate enemies) to oppose him at Chaironeia.

But that’s how it went. Philip won anyway and created the Corinthian League, whose purpose was the invasion of Persia and vengeance for the earlier Persian invasion of Greece. Was that Philip’s primary motivation? Oh, hell no. He wanted the MONEY/loot (and glory). But a campaign of retribution put a better face on it, and justified his usurpation of the Athenian navy, which he absolutely had to have to be successful.

When Philip was assassinated, Alexander simply took up where his father left off. He literally told the Corinthian League (when he reconvened them not long after Philip’s death), “Only the name of the king has changed….”

So yes, the propaganda wasn’t invented by Alexander, or even by Philip, but they used it to very good effect, as it allowed them to demand allies (and BOATS). Alexander didn’t dissolve the alliance and release those troops until after Darius’s death. And even then, he offered good pay to stay on with the rest of his conquests (which many did).

#asks#philip ii of macedon#Philip of Macedon#Alexander the Great#ancient Macedonia#Greco-Persian Wars#Alexander's campaigns#Isokrates#Isocrates#ancient Athens#Greek revenge campaign against Persia#Classics

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

After he had settled everything in the assembly, and the Athenians had voted him the command of the expedition, he chose as his colleague Demosthenes, one of the generals at Pylos, and pushed forward the preparations for his voyage. His choice fell upon Demosthenes because he heard that he was contemplating a descent on the island; the soldiers distressed by the difficulties of the position, and rather besieged than besiegers, being eager to fight it out, while the firing of the island had increased the confidence of the general. He had been at first afraid, because the island having never been inhabited was almost entirely covered with wood and without paths, thinking this to be in the enemy's favour, as he might land with a large force, and yet might suffer loss by an attack from an unseen position. The mistakes and forces of the enemy the wood would in a great measure conceal from him, while every blunder of his own troops would be at once detected, and they would be thus able to fall upon him unexpectedly just where they pleased, the attack being always in their power.

Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War

0 notes

Text

Reading the speeches of Alcibiades in Thucydides outloud and changing all the Rs into Ls to get the full experience.

#alcibiades#tagamemnon#our general speaks like a toddler but we love him - the athenians probably#and then you have people like demosthenes who was gurgling pebbles to fix his lisping problem#but do you think alcibiades would be like demosthenes and practice his speeches in front of a mirror? i think he would

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recently read through Kate Elliott's Unconquerable Sun and Furious Heaven, the first two parts of a trilogy described as genderbent Alexander the Great in space. Excellent books, but I didn't have the knowledge of Alexander's life necessary to draw the historical parallels. Fortunately, the author has a few essays up on tor.com explaining it. Unfortunately, she doesn't spell out all the connections, so here's what I have, ones stated by the author bolded:

(some spoilers, I guess)

Sun: Alexander the Great

Eirene: Phillip II of Macedon (Alexander's father)

Joao: Olympias (Alexander's mother)

Persephone "Perse" Lee: Ptolemy I Soter (Alexander's companion, later pharaoh of Egypt, noted for keeping memoirs and sponsoring mathematics)

Hestia "Hetty" Hope: Hesphaistion (Alexander's companion and lover)

Alika Vata: Perdiccas (Alexander's companion and general)

James Samtarras: does not have a historical analog, since he apparently fulfills multiple roles

Makinde Bo: Lysimachus (Alexander's general)

Razin Nazir: don't know, she hasn't shown up much, presumably one of Alexander's other companions/generals

Jade Kim: Craterus (Alexander's general, often distrusted for his ambition)

Tiana: Thais (courtesan who later became Ptolemy's consort)

Solomon: Seleuccas (Alexander's general, later founded the Seleucid Empire)

Octavian: no historical analog

Zizou: no historical analog

Crane Marshal Zaofu Samtarras: Parmenion (cautious older general contrasted against Alexander)

Anas Samtarras: Philotas (Parmenion's oldest son)

Angharad Black: Cleitus the Black (soldier who saved Alexander's life)

Moira Lee: Attalos (friend of Phillip's who arranged his marriage to Attalos's yougner relative)

Marduk Lee: Antipater (Alexander's regent in macedonia while he was away on campaign)

Nona Lee: Antigonus? I'm hesitant about this, but Nona is the only character I can think of who fits the description of "one of Philip’s old guard who unlike most of the rest of the older generation retained his importance long into and past the Alexander era"

Dimitar: Demetrius (Antigonus's son, the names match which supports the Nona=Antigonus theory)

Soaring Shan: Cleopatra (Alexander's sister)

Metis: Phillip Arhiddaeus (Alexander's half brother, deemed mentally unfit to rule)

Beau Qiang: Callisthenes (Alexander's historian)

Baron Voy: amalgamation of Demosthenes and Aeschines (athenian orators)

Baragesi: Darius III (ruler of the persians)

Jejomar Os Cook: Sisygambis (Darius's mother, captured by Alexander)

Bartholomew: Barsine (persian noblewoman who knew Alexander as a child, and later married him)

Manu: Memnon (greek mercenary who fought for persia)

Apama: this one I struggled with, Kate Elliott says, "She has an historical counterpoint and in some ways I consider her my most important gender spin in the entire story." But I couldn't find any corresponding person she could be genderbent from. Then I realized that "gender spin" could be referring, not to making a historically male figure female, but to giving a female figure the agency and role in this narrative that she didn't get in the historical record. So my guess is Apama I, a persian noblewoman from a region whose leaders were later referred to as Sabao, whose wikipedia page basically just lists her father, husband, and children.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

OKAY SO I RAN THE 14 JULY 1779 LAMS LETTER THROUGH GOOGLE TRANSLATE IN A TON OF LANGUAGES THEN BACK TO ENGLISH AND THE RESULT IS FUCKING HILARIOUS IM CRYING OH MY GOD

@the-reynolds-pamphlet LINCOLN HERE IT IS

From Lieutenant Colonel John Lawrence to Alexander Hamilton, July 14, 1779 Lieutenant Colonel John Lawrence Charles Wiley. [South Carolina] July 14, 79.

Ternant will tell you the level of violence between my responsibilities and tendencies. My heart is with you because you seem to work more actively here, but in my opinion, it is unforgivable from a citizen's point of view , And not the slightest hope of success exists, but his noble efforts to complete the black tax plan did not continue. With the departure of the virgins, our army was almost reduced to zero; the arrival of the Scots would hardly bring us back to our original numbers. If the enemy is near here, G.B. should be like this politically. This number is not enough for the security of our country. Among other things, the governor would like to propose that the end of our continental war be submitted to Parliament in preparation for the next election. Recruitment of militia; I was told that this measure is so unpopular that there is no hope of success: Either it must be accepted or a black tax must be levied, or the country may be lenient and careless by its residents. Due to the large number of representatives on the scene, the House of Representatives has more time than usual-although it will be held in a few days-I intend to qualify-and make the final efforts. Oh, if I were Demosthenes, the Athenians would never deserve more severe criticism than my compatriots.

General Moultrie led our remnant army in Storno and the observation mission at Beaufort Ferry. In his last letter, he told us that the enemy was preparing to accept their patients in Beaufort’s court and prison and proposed The planning area where supplies are provided. The Clinton movement and subsequent parade inspired me to be with you; if there is any important shd. I may be near your home because I am confessing every day, without successful persecution, cursing my stars, and disagreeing with this world. My dear friend, please write to me and explain what is happening when circumstances permit. Goodbye, my love for my dear friend. I'm afraid I was too careless. The last letter gave me a memory of Gibbs. Bye again John Lawrence You know my opinion on the value of ternants, their health and their business. I call them the North; if you can provide the services they deserve, we just have the enthusiasm and talents they haven't used. Colonel Hamilton

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Famous people

Tag list of famous people from Ancient Rome and Greece. A few hellenistic rulers and some Etruscans are also included.

And for some reason the page is not working properly. The HTML code is there, but it only works on my dashboard. On this page links are inactive. I figure that page only understands “/tagged/Agrippina-the-Elder” - versions, but I’m too lazy / busy to rewrite the code. So if you want to check a tag, you’ll have to copy and paste it after the word “ .../tagged/”. And same goes for all the lists below.

URLs + copy&paste:

https://romegreeceart.tumblr.com/tagged/

https://romegreeceart.tumblr.com/archive/tagged/

A

Aelia Flaccilla- Pillar of the Church

Agrippina the Elder

Agrippina the Younger

Aemilia Lepida and her descendants v emperor Nero

Aeschylus

Aetius

Alaric

Alcibiades

Alexander the Great

Ancus Marcius

Antinous

Antiochus I Soter

Antiochus III the Great

Antisthenes (philosopher, cynic school)

Antonia Minor - mother of Claudius and Germanicus

Antoninus Pius

Apicius

Apollodorus of Damascus

Apollonius of Tralles (Greek sculptor)

Aristotle

Arsinoe II

Arsinoe III

Artemisia II of Caria

Aspasia

Atticus (Cicero’s friend)

Attila

Augustus

Aulus Rustius Verus (Pompeian politician)

Aurelianus

B

Baltimore painter (Apulia, 4th century BCE)

Berenike II

Britannicus

Brygos Painter

Brutus (liberator, founder of the republic)

Brutus (assassin)

C

Caesarion

Caligula

Callimachus

Caracalla

Carausius (Roman Britain, emperor)

Carinus

Cassius Dio

Catiline

Cato the Elder

Cato the Younger

Cicero

Claudia Antonia (emperor’s daughter)

Claudius

Claudius Gothicus

Cleopatra

Cleopatra Selene

Cleopatra III

Clodius Albinus

Commodus

Constantine the Great

Constantius II

Constantius Chlorus

Corbulo

Cornelia Africana

Cornelia Minor (Caesar’s wife)

Crispina

Crispus (Constantine’s eldest son)

Croesus

Cynisca (Spartan princess, olympic winner)

D

Darius III

Decius

Demosthenes

Didia Clara (daughter of Didius Julianus)

Didius Julianus

Diocletianus

Dioscorides Pedanius (physician, botanist)

Diva Claudia (daughter of Nero)

Domitianus

Drusus Caesar (son of Germanicus)

Drusus the Younger (son of Tiberius)

Drusus the Elder (son of Livia)

E

Elagabalus

Eumachia (Pompeian priestess and patroness)

Euripides

F

Fabius Maximus Cunctator (”The Shield of Rome”)

Faustina Maior

Faustina Minor

Female painters

Flavian dynasty

G

Gaius Caesar

Galerius

Galba

Galen

Galla Placidia

Gallic emperors

Gallienus

Germanicus

Gelon

Gens Aemilia

Gens Cornelia

Gens Calpurnia

Geta

Gordian I

Gordian II

Gordian III

Gracchi Brothers

Gratian

Greek tyrants

H

Hadrianus

Hannibal

Hegias (Greek sculptor, 5th century BCE

Hellenistic kings

Herennius Etruscus (co-emperor)

Hermione Grammatike

Herodes Atticus

Herodotus

Hippocrates

Historians

Homeros

Honorius

Hostilianus

I

Iaia of Cyzicus (female painter)

Jovianus

Juba II

Julia (Augustus’ daughter)

Julia Aquilia Severa (Vestal virgin and empress)

Julia Domna

Julia Drusilla

Julia Felix (Pompeian business woman)

Julia Flavia (Titus’ daughter)

Julia Maesa

Julia Soaemias

Julian the Apostate

Julio-Claudian family (julioclaudian)

Julio-Claudian dynasty

Julio-Claudian

Julio-Claudian dynasty

Julius Caesar 1

Julius Caesar (2)

Julius Vindex

K

Kings

Kresilas (Athenian sculptor)

Kritios (Athenian sculptor)

L

Lady of Aigai

Lady of Vix (Celtic woman, late 6th century BCE)

Lassia (priestess of Ceres, Pompeii)

Lepidus

Leonidas

Livia

Livilla

Livius

Lucilla (daughter of Marcus Aurelius)

Lucius Appuleius Saturninus

Lucius Caecilius Jucundus (Pompeian banker)

Lucius Caesar

Lucius Herennius Flores (Boscoreale Villa, real owner ?)

Lucius Verus

Lysippos

Lysippos 2

M

Maecenas

Macrinus

Magnus Maximus

Mamia (Pompeian priestess and patroness)

Marcellus (Augustus’ heir)

Marcus Agrippa

Marcus Antonius

Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Claudius Tacitus (emperor)

Marcus Licinius Crassus

Marcus Terentius Varro

Marius

Martialis

Masinissa

Maussollos of Halicarnassos

Maxentius

Maximianus

Maximinus Daia

Maximinus Thrax

Members of imperial families

Menander

Miami painter

Milonia Caesonia

Miltiades (Greek general)

Mona Lisa of Galilee

Myron

N

Nero

Nero Julius Caesar (son of Germanicus)

Nerva

Nerva-Antonine family

Numa Pompilius

O

Octavia the Younger (Augustus’ sister)

Octavia (Claudius’ daughter)

Optimates

Otho

Ovidius

P

Paionios (Greek sculptor)

Patronesses

Penthesilea painter

Pericles

Pertinax

Pescennius Niger

Pheidias

Philip the Arab

Philosophers

Philip II of Macedonia

Phryne (Greek courtesan)

Plancia Magna

Plato

Pliny the Elder

Pliny the Younger

Poets

Polykleitos

Pompeius

Poppaea Sabina

Populares

Postumus Agrippa

Postumus (Gallic emperor)

Probus

Ptolemy of Mauretania

Praxiteles

Ptolemy I

Publius Clodius Pulcher

Publius Fannius Synistor

Publius Licinius Crassus (triumvir’s younger son)

Publius Sittius

Publius Quinctilius Varus

Pythagoras

Pyrrhus

Pytheas (a greek explorer)

Q

Queens

R

Roman Caesars (= princes, heirs to the throne)

Roman Civil War Commanders

Roman client kings

Roman consuls

Roman dictators

Roman emperors

Roman empresses

Roman generals

Roman gentes

Romans who declined the throne

Romulus Augustulus

Romulus and Remus

S

Sabina

Sallustius

Sappho

Scipio Africanus

Scopas

Sejanus

Septimius Severus

Seven sages

Severan dynasty

Severus Alexander

Sextus Pompeius

Shuvalov painter

Silanion ( Greek sculptor)

Socrates

Solon

Sophocles

Stilicho

Strabo

Sulla

Sulpicia (Roman female poet)

T

Tacitus

Tarpeia

Tarquinius Superbus

Themistocles

Theodosius

Theophrastus

Thucydides

Tiberius

Tiberius Claudius Verus (Pompeian politician)

Tigranes the Great

Titus

Titus Labienus

Titus Tatius

Titus Quinctius Flaminius

Trajanus

Trebonianus Gallus

Tribunes of the plebs

U

Ulpia Severina (interim sovereign in 275 CE)

Urban prefects

Usurpers

V

Vaballathus (Palmyran king)

Valens

Valentinianus I

Valentinianus III (murderer of Aetius)

Valerianus

Valeria Messalina

Vel Saties

Velia Velcha (“Mona Lisa of antiquity”)

Velimna family (Hypogeum, Brescia)

Vercingetorix

Vergilius

Vespasianus

Vibia Sabina

Vipsania Agrippina

Viriathus (Lusitanian freedom fighter)

Vitellius

Volusianus

X

Xenophon

Y

Z

Zenobia

189 notes

·

View notes

Text

so i’ve been doing research on the word hubris lately because ancient greek philology and translation is a special interest of mine, and i’m posting the results under a cut here because it’s a little long, but the tl;dr of it is that hubris is no more of a religious term than theft or assault is, and it would be better to just say impiety if you mean impiety (or asebeia if you want a greek word)

tw in here because i do mention violence, sexual assault, and one instance of suicide in a tragic play

(prefacing this with sorry if i keep switching between hubris and hybris, they’re both two ways to transliterate ὕβρις, they mean the same thing)

I’ll start with the Liddell-Scott ancient-greek-to-english dictionary definition, which translates hubris as “wanton violence, arising from the pride of strength or from passion, insolence, freq. in Od., mostly of the suitors.” Hubrisma is an outrage, hubristes is a violent, overbearing man. There is also a verb form, hubrizō, to do hubris. I very intentionally say to *do* hubris, rather than to *be* hubristic, because while hubris was associated with a certain attitude, in practice the word indicated one’s resulting actions. Demosthenes uses forms of hybrizō in his speech “Against Midias”, to describe the man punching him in the head during a festival. Nowhere in this is mention of piety, because the opposite of hubris is sophrosyne (sound-mindedness, self-restraint). The opposite of eusebeia is asebeia, an absence of piety.

Next I’m mostly going to summarize an article called “'Hybris' in Athens.” by Douglas MacDowell, because it’s quite a nice exploration of how hubris is used in both literary and legal contexts. He actually argues that there’s no evidence or reason to believe definitions change between either setting.

He begins with a discussion of all the ways hybris can be used in texts, including its use describing rowdy and loud animals. Sound seems to be an important factor, because he also cites a legal document where hubris could have been charged against the defendant (rather than just assault) for jeering and clucking at the man he struck. The myth of the Lapiths and the Centaurs is a fitting example of a hubristic dinner party, considering uses of hubris to compare people to horses (an especially hubristic animal). Hubris for men involves eating and drinking too much, being loud and making rude jokes, being sexually inappropriate, engaging in useless pursuits, doing violence and murder, and being disobedient to name just a few acts.

This disobedience is where one might get accused for hubris toward the gods, but in this sense it would be the same severity of crime as disobeying a king or stealing from a temple, because as MacDowell states, “...hybris is not, as a rule, a religious matter” (22) and also that “there is nothing to show that the Athenians generally thought that hybris had any more to do with the gods than any other kind of misconduct.” (22-23) Denying the existence of gods might be another example of religious hybris, at a time when atheism and antitheism were not separable, but this was also during a time when impiety was punishable by death, so take that as you will.

The definition of hubris that MacDowell comes to is self-indulgent misuse of energy or power. The exact reasons for hubristic actions are unclear, whether it arises from the arrogance of tyranny, or having enough wealth to be disruptive in public, or simply the energy of youth. Kambyses does hubris to his subjects by killing them without trial. Aeschylus in “Suppliants” uses hubris to mean lust and entitlement of men toward women’s bodies. Plato says a child is the most hubristic of animals, and hubris is definitely associated with teenagers and rich people, but not exclusive to them. A case appears in Athenian law where a father had to defend his son from accusations of hubris for killing another student with a javelin while messing around and not taking training seriously, and the defense was that the act was unintentional. Hubris is something done knowingly, without care for whom it may harm.

On that note, hubris very often has an identifiable victim. Victimless hubris does show up in texts, such as a story of a party of rowdy young men traipsing into the desert simply to explore, but is less common as what most texts are concerned with is the *crime* of hubris. Aristotle differentiates the crime from simple assault by saying hubris is doing harm for the pleasure of feeling superior. Other scholars have defined hubris as treating another as one would an enslaved person, but it’s interesting to note that Athens specifically had a law protecting enslaved people from hybris.

In literature, the term is sometimes used meaning “depriving someone of a prize or privilege which he has earned” (MacDowell 19), such as Agamemnon’s seizure of Briseis, or Menelaos’ refusal to bury Aias. Yet, hubris can also be done to oneself against other’s wishes, as with the case of Deianeira killing herself with a sword. “If committing suicide in sorrow, shame, and despair can be called hybris, that shows that hybris does not necessarily involve pride or arrogance, or setting oneself above the gods, or a desire to disgrace another person” (MacDowell 19).

So, to summarize, hubris in ancient Greek is not the same as hubris as it’s used in English, and it does not carry religious connotations. Hubris in ancient Greek referred to unruly behaviour without care for authority or those around you that could get hurt. Hubris can be attempting to control or disobey the gods, but thinking yourself on the same level as the gods is more accurately described as impiety or asebeia, a separate crime that could be of similar severity.

Sources:

LSJ definition: http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0057:entry=u(/bris1

MacDowell, Douglas M. “'Hybris' in Athens.” Greece & Rome, vol. 23, no. 1, 1976, pp. 14–31.

Further Reading:

Cohen, David. “Sexuality, Violence, and the Athenian Law of 'Hubris'.” Greece & Rome, vol. 38, no. 2, 1991, pp. 171–188.

Filonik, Jakub. “Athenian Impiety Trials: A Reappraisal” https://riviste.unimi.it/index.php/Dike/article/view/4290

156 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sooo.... With lots of AC:O actors in Fenyx Rising

Eagle Bearer to War Goddess...nice But then...

Spartan general (and an Athenian general because Demosthenes) to the God of War

I find it fucking HILARIOUS that these two go from voicing a pair with an awesome friendship and Drift Compatibility; to two gods with an infamous rivalry.

#immortals fenyx rising#Assassins Creed Odyssey#Also Ares gets turned into a rooster and that's fucking hilarious.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 3rd Messenian War happens in Sparta - A force of Athenians are sent to help - led by Kimon - who was (probably) related to Thucydides and (possibly) Demosthenes - the latter is said to have "had a special relationship with the Messenians" of Naupaktos - even in his first season of war he's clearly tight with them - the Messenians were settled in Naupaktos by Athens at the end of the 3rd Messenian War - Demosthenes sheltered at Naupaktos after he messed up in Aetolia - and it's generally agreed they prompted him to undertake the fortification of Pylos - two ships of Messenians who arrived "by chance" with necessary supplies to make those fortifications happen -

And I'm back to the lynch-pin - the situation around the battles of Sphakteria and Pylos, central to the Arkhidamian War and the culmination of forces that had been moving - fomenting - for at least thirty years. They are the continuation of the 3rd Messenian War.

What I'm trying to say is - in a really direct way, Demosthenes is the conduit that brings all of this to a head.

What I want to know is: Did he know that? Did he see it? How radicalised was he? Did he see himself as fighting for the freedom of the Messenian Helots or was he simply fighting a war by any means necessary?

#demosthenes general of athens#greek history#ancient history#when your synapses are like please please we need rest

10 notes

·

View notes

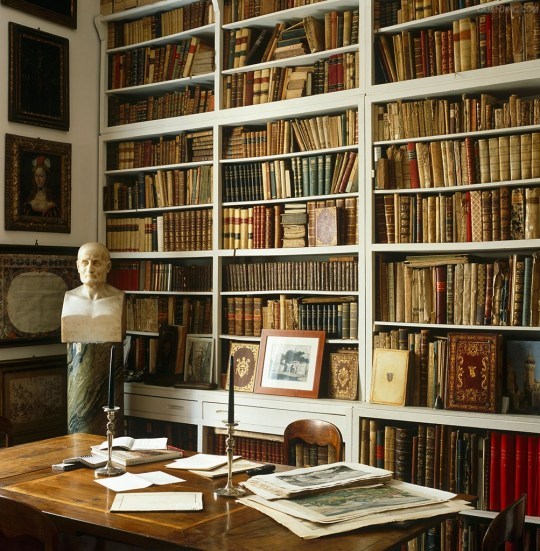

Photo

Demosthenes

Demosthenes (c. 384 - 322 BCE) was an Athenian statesman who famously stood against Macedonian king Philip II and whose surviving speeches have established him as one of the greatest patriots and powerful orators from ancient Greece. He is not to be confused with the 5th century BCE Athenian general of the same name.

Early Life & Works

Born in c. 384 in Athens, Demosthenes' parents died while he was still only seven years old, and so he then lived under guardianship. Famously, at the age of 18, he prosecuted his guardians for wasting his inheritance, delivered his own speeches in court, and won the case. Studying under Isaeus and working as a speech writer (logographos) like his master, his first experience in court was as a prosecutor's assistant. We also know that in 358 BCE he was a grain-buyer (sitones). Then, from c. 355 BCE, he came to wider attention when he started to deliver his own speeches in the assembly of Athens.

61 speeches of Demosthenes - both public and private - have survived, along with the rhetorical openings (prooimia) for around 50 speeches and 6 letters. Probably, some of that number were speeches given by another orator by the name of Apollodorus but it is, nevertheless, a substantial amount of material. That is, even if, Demosthenes would have given many more speeches than that in his long and illustrious political career. Those that survive show a speaker who could use plain language and lucid argument to devastating effect. He was a master of metaphor but never overused it and, perhaps his greatest and most enduring quality, his work shows an absolute and convincing sincerity.

Continue reading...

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anonymous asked: I hugely appreciate how educated you are with your education in the Classics (at either Oxford or Cambridge I think) but I ask with sincere respect how does any of it inform your privileged life in this day and age? It’s easy to say how much we should value our European traditions and heritage it is quite another to live it out don’t you agree? What do you personally get from it?

This is a very relevant question and I apologise if I have stalled in answering it as I was busy with work and life to formulate a worthy reply. But your question is an important one indeed for anyone who harkens to the past as a guide for the present and the future.

I won’t waste space here and tick box all the purely academic reasons why the Classical world is still relevant for us today. I think you can find that in easy to read books and articles written by eminent Classicists who do an admirable service in making the Classical World come alive for the general public (Mary Beard, Bettany Hughes, Emily Wilson, Edith Hall, Peter Jones, Bernard Knox, Robin Lane Fox, Paul Cartledge, and Donald Kagan amongst others that come to mind). But it’s an uphill battle to be sure.

Classics - at least in United Kingdom - has been regressively marginalised with each passing generation starting from school up to university entry. It has an image problem. Few pay much attention to scholars of Latin and Greek. The impression is that Classicists are snobbish and is the education of privileged elitists who master languages that are not spoken. They learn to write them only to read them better. They slap your hands when you write a Latin word common in Sallust or Livy, rather than in Cicero. There is some truth to that sadly. To a large extent Classicists themselves have not been a good advertisement for why anyone should appreciate let alone study the classical world.

At one end those educated in the Classics can come across as encouraging elitism, snobbish pedantry and a sniffy social superiority and at the other end those not versed in Classics but through Hollywood (any sword and sandal film like Gladiator etc) and PC white washed TV series (BBC’s Troy is a good example) have formed a romantic attachment to the ‘heroic’ past by having blue pilled themselves into escapism. Both extremes makes Classics a fetish rather than a guide for life through the beauty and power of the language and culture of the singular Greeks and Romans.

The study of Classics can become the proverbial dog who can dance on two legs, but for what practical purpose? There is the rub. Classics, at its best, offers the historical, philological, and literary foundation and discipline to apply a critical method to every general aspect of learning - and living.

I was fortunate that I had Classicists - both within my family and also my teachers - who were cultured and had led such interesting lives and were able to marry their Classicist mind to their life experiences (often through the experience of war). So learning European languages was not just to get one’s head around arid esoteric articles by 19th-century Frenchmen on the Athenian banking system or Demosthenes’ use of praeteritio and apophasis, but also to appreciate the genius of Dante,Voltaire and Goethe. Classics should never just be about philology though because it can result in a life mostly missed.

Perhaps others might call it privileged but I consider my childhood blessed because I was surrounded by family members who were educated in the Classics - more rare than one might suppose. Through my great aunts and grandmother they instilled the discipline that the mastery of Latin and Greek fuelled the ability to speak and write good English -- and why the latter mattered as much or more than the former.

By the time I left both Cambridge and Oxford behind, I could cite passage numbers in Greek texts of what Thucydides and Plutarch thought of Nicias. But it was only when I went through Sandhurst to pass out as a commissioned army officer did it truly jump off the page and become alive for me.

Moreover having had long fire side conversations with both my grandfather and father - both Oxbridge educated Classicists and both served in distant different types of wars as swashbuckling officers - did I use that learning to understand why for example was Nicias such a laughably mediocre general of the Peloponnesian War. And this was essentially the practical point of reading Thucydides and Plutarch about Nicias in the first place.

I spent many hours in my down time during my service in Afghanistan between missions re-reading dog earred favourite Classicist texts. I began to see the ghosts of the Greeks in the characters of those with whom I was serving. Some began to resemble Sophoclean characters - especially the less well-known ‘losers’ like Ajax and Philoctetes - the sort of tragic heroes whom we root for but the odds are against them - think of any American Western film or the more pathological Tarantino films. Like Sophocles I saw majestic characters (some special forces operators) out of place in a modernising world who would rather perish than change - but in a context where their sacrifice schools the lesser around them about what the old breed was about and what was being lost.

A running thread from a childhood spent in many other countries - from South Asia to the Far East - to the present day is learning to appreciate our landscape as the Ancient world did. The cultivation of curiosity of cultures was seeded in childhood. Respecting and even admiring other cultures - Indian, Iranian, Chinese and Japanese primarily come to mind - led me to appreciate and treasure my own cultural heritage and traditions. The DNA of both the Roman and Greek world went far and wide and so teasing out their fingerprints was fun. In northern Pakistan, we came across ‘Alexander’s children’ - children with blonde and blue eyes who were said to be descended from Alexander the Great’s time in Afghanistan and India - and wandering around the banks of the Jhelum river imagining how Alexander beat his respected foe (later ally) King Porus at the Battle of Hydaspes in 326BC.

These days despite having a busy corporate career I help support running a French vineyard managed foremost by two exceptional cousins and their French partners. As such the Classics still resonate in how I look at the land beyond the vineyard - bridges, roads, towers, walls - and imagine the Greeks not with ink and papyrus but as men of action, farmers and hoplites, in a rough climate on poor soils. I suddenly envision them pruning and plowing in Laureion, the Oropos, and Acharnae, more like the rugged local farmers with whom come harvest time I roll my sleeves up and get my hands dirty in the vineyards than as the professors in elbow patches who had claimed them.

Knowing and learning about the Classical roots of our Western heritage isn’t just a question of culture it’s also about what personally motivates us in life and how that determines how we make consequential choices in life.

I live in fear of one Greek word ‘akrasia’. Ancient Greek philosophers coined the term to explain the lack of motivation in life. Most of the philosophical conundrums explored by contemporary philosophers were already explored in Ancient Greece. In fact, Ancient Greek philosophers laid the solid foundation for all philosophical approaches that appeared throughout history: theories of Kant, Hegel or Nietzsche would never exist without Socrates, Plato or Aristotle.

Among the many problems that baffled the Ancient Greeks, one of them gets quite a lot of attention today. Why don’t we always do what’s best for us? Why do we abandon good decisions in favour of bad ones? Why can’t we follow through on our plans and ideas?

Many people would say that the answer is simply laziness or decision fatigue, but Ancient Greek philosophers believed that the problem lay much deeper, in human nature itself. ‘Akrasia’ describes a state of acting against one’s better judgement or a lack of will that prevents one from doing the right thing. Plato believed that akrasia is not an issue in itself, because people always choose the solution they think is the best for them, and sometimes it accidentally happens that they choose the bad solution because of poor judgement. On the other hand, Aristotle disagreed with this explanation and argued that the fault in the human process of reasoning is not responsible for akrasia. He believed that the answer lies in the human tendency to desire, which is often far stronger than reason.

As with almost all philosophical concepts, a consensus has never been reached and akrasia remains open to interpretation. But its practical consequences are all too real in today’s world. Motivation is what makes us unpredictable and persistent, and the life circumstances of the modern world often make motivation disappear.

Today - regardless how old or young one is - many are more and more tempted to exchange a long-term goal for an immediately available pleasure in all its forms from the emotional band aid of porn from a lifeless relationship (or a lack of one) to escaping loneliness for the false intimacy of social media friendship. The lack of motivation can cause us to reduce ourselves to someone else’s standards when we know we can be or do better.

The Greeks felt that the way you think and feel about yourself, including your beliefs and expectations about what is possible for you, determines everything that happens to you. When you change the quality of your thinking, you change the quality of your life. I’ve been deeply influenced by Aristotle’s idea that virtue is a habit, something you practice and get better at, rather than something that comes naturally. “The control of the appetites by right reason,” is how he defined it. Another way to reframe this is to say, “Virtue is knowing what you really want,” and then building the intellectual, spiritual, and moral muscle to go after it.

To be cultured - as opposed to be merely educated - is how you put what you’ve learned to work in your own life, seeing the world around you more deeply because of the historical, literary, artistic and philosophical resonances that current experiences evoke. This is the privilege of being cultured. For me Classical stories come often to my mind, and some times provide guides to action (much as Plutarch intended his histories of famous men to be guides to morality and action). The classics then are a part of my mental toolset and the context I think with some of the time. I see that as the real blessing in my life.

Thanks for your question.

170 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I was curious about what your favourite modern biography of ATG is (if you've been asked this before I haven't found it). I have some time on my hands right now and I would love some new reading material. I've read Greens book and Conquest and Empire by Bosworth and liked both a lot. Would you recommend something specific or maybe more recent? I love reading your posts on here :)

Hmm. Some of the more prominent Macedoniasts haven’t actually written bios, unlike some of the earlier generations. Bosworth’s is good. I like it. Green’s...I take issue with some things, but he makes some really good points. It’s important to remember the original version on which the revised version is based, was written right around the time of the discoveries at Vergina. Similarly, I like Hammond’s ATG: King, Commander, and Statesman, but beware of whitewashing. Don’t bother with his later bio, imo.

Lindsay Adams has a fairly brief one Alexander the Great: Legacy of a Conqueror, that I use in my own ATG class, in part because it’s designed for college undergrads or advanced high school students. What I like about it, other than it’s short, is that it includes more information about Macedonia than some of the other earlier bios. I also use Carol Thomas’s Alexander the Great in His World, as it’s less bio than centering ATG in the larger Macedonian context for my students.

There have been some other more recent bios that I don’t really care for. Paul Cartledge isn’t a Macedonian specialist (he’s “Mr. Sparta”). Worthington...well, I disagree with a lot he’s said. And the Freeman one... he’s not a specialist, and he just turns out bios like a machine. There are a couple others that came out recently, and I don’t even recognize who the person writing it is.

I did just learn Ed Anson is coming out with a (sorta) bio on Philip later this year, Philip II: Father of Alexander the Great (Themes and Issues), which I expect to be very good, as Ed does a lot on Argead Macedonia. That said, and while it’s outdated in many ways, I still like Jack Ellis’s Philip II and Macedonian Imperialism.

Last, for pure analysis of ATG as military leader, John Keegan’s chapter on him in Mask of Command is quite good...but DON’T pay any mind to his description of Macedonian power structures, etc. It’s both simplistic and out of date/plain wrong. And he completely overlooks the role of religion for ATG and in ancient warfare.

One difficulty is just HOW fast things have been changing in our understanding of Macedonia itself, thanks to a rise in archaeology in the region. It should (and is) shifting some perspectives about when “Hellenization” of the region really began. Rather than Philip fulfilling what Archelaos started, it looks now like Philip just resurrected the kingdom after a slump, which had significant earlier contacts both east (via Euboia at Methone) and west (via Corinth at Aiani and Dodona/Epiros).

All that DECENTERS damn Athens. Our problem is that so MUCH of “Greek History” = “Athenian History” to the point that if Athens isn’t involved, it’s perceived as “not important” (in part because it’s not in the surviving historical written record). This gets back to my favorite “saw” in lectures: We’re prisoners of our evidence. And so much of that, especially written, has been dominated by Athens.

To add insult to injury, some of the Athenian narratives about Macedonia (especially by figures such as Demosthenes) worked well for a certain Roman literati writing about Alexander later.

Unfortunately, these narratives were picked up somewhat uncritically by former generations of historians. Increasingly in ATG/Philip/Macedonia studies, we’re trying to question both the Roman overlay, and the Athenian bias. So that’s why it’s important to look at the author of the bios of ATG, as to their awareness of what’s going on in Macedonia these days, both in textual studies, but also the archaeology.

Are they a Macedoniast, or just Joe Blow trying to make a buck writing (Yet Another) biography of Alexander?

Anyway, when it comes to bios on ATG, my best suggestion is to ask who wrote it, and what their specialization is? Does this person regularly write and publish articles in the field? That means do a quick CV (or resume) check. :-) So Green, Bosworth, Hammond (Hamilton, although that bio is now old), Adams, to a lesser degree Thomas, but certainly Anson and Ellis...even Worthington: all deal with Alexander (and Macedonia) regularly and keep up with what OTHER people are saying, in articles.

Joe Blow (I want some money) probably isn’t that aware of current, larger conversations in the field. Their bibliographies are almost always truncated.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think probably some of the most interesting characters in Odyssey are the Spartan and Athenian generals Lysander and Demosthenes and yet they don’t have any personality at all. Just 5 fetch quests each

7 notes

·

View notes