#DIET VERTICAL MIGRATION

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

just saw a tiktok clip that said that every dino boy needs a shark boy. so true. whos gonna be my dino boy.

#guys i love sharks did u know that#do i talk abt it enough skjdfhjskdf#like!!! thresher sharks r so cool!!!#theres three species that we know of but a lot of professionals think theyre might be four??? thats sick????#ALSO ALSO ALSO theyre endoderms!!!! thresher sharks have special thermoregulation so they produce heat internally which like helps with-#-their metabolism and muscle shivering!!!#shoutout to the bigeye thresher btw their eyes r in keyhole shaped socket things so their eyes can rotate up its so sick#they have their bigger eyes so they can hunt in the dark!!!!#they also have like a. whats it called.#DIET VERTICAL MIGRATION#so they stay deeper underwater during the day then at night they come up closer to the surface to feed!!!#since its a thresher it still has thermoregulation too OH YEAH I FORGOT TO MENTION threshers are warm blooded!!! so their body temp is-#-higher than the water temp that they usually stay in#anyway. those r my shark facts for the day. did not mean to just ramble there JKGHSKJGHKJS#mlm#mlm yearning#mlm post#mlm love#gay mlm#trans mlm#t4t#mlm blog#mlm thoughts#t4t yearning

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fish of the Day

Happy Tuesday, everyone! Today's fish of the day is the strawberry squid!

The strawberry squid, also known as the cockeyed squid, and scientific name Histioteuthis heteropsis is known for their distinctive eyes. Living in the twilight zone (mesopelagic zone) of the ocean, stretching the depths of 200 meters to 1,000 meters, these squid have a unique method for the intake of light in their native range and ability to spot prey and predators. But first, let's go over their range and habitat. The strawberry squid lives exclusively within the twilight zone from 200-1000 meters, undergoing diel vertical migration (a daily migration taking place at night where deep sea animals move upward to predate on various plankton and active nekton) when most predators in shallower waters rest. During the day these squid can be found anywhere from 500-700m, but during the night they are found from 300-400m. Range wise, they can be found in the California and the Humboldt currents, which border the Western coast of the United states, and then further South to the Equator, with the squid living out past the continental shelf.

With an entire name focusing on it, the strawberry squid is best known for the unique eyes they have developed. Due to living in the mesopelagic twilight zone of the ocean, only 1% of all sunlight that is present at the water surface can be visible at even the shallowest sections of the zone. These different eyes are designed for seeing better in light/darker areas of water, with the larger eye focusing on looking upward to spot the shadows of prey cast in the water above them. The smaller eye looks downward in the water column to focus on flashes of bioluminescence that could warn of prey or predators. These eyes are the same size when young, but develop as the squid ages. The other, and more common name for the strawberry squid is focused on their general coloration, and the photophores scattered around the body, which are visually similar to strawberry seeds. Photophores can be found on many different deep sea animals, and are small light producing organs, which are only found in the Histioteuthis family of squids, which contains only the strawberry squid and a close relative. These photophores are used for counter illumination, to hide from both predators and prey.

The diet of the squid is made up of shrimps, fishes, and other deep sea squid. These prey are captured by ambush, as the squid very carefully searches for them visually before sneaking closer until it is in range to lunge, wrapping its tentacles around prey and biting down with the sharp beak. They can grow up to as long as 13cm, with only about 5 inches of mantle length. Very little is known about their reproduction or mating, but squids in the Histioteuthidae family lack a specialized mating tentacle, and rather rely on small packets of sperm masses it can send out, which will then find the female squid and meet eggs held within the single ovary. Other than this, the lifecycle of this squid is entirely unknown, leaving many things about them a mystery for now.

That's the strawberry squid! Have a wonderful Tuesday, everyone!

#Histioteuthis heteropsis#squid#strawberry squid#cockeye squid#fish#fish of the day#fishblr#fishposting#aquatic biology#marine biology#freshwater#freshwater fish#animal facts#animal#animals#fishes#informative#education#aquatic#aquatic life#nature#river#ocean#deep sea#seep#deep#twightlight zone#mesopelagic

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bluntnose Six-Gill shark

Felt like I should finally make a post about my favorite shark species (They are my everything)

Basics

Bluntnose Six-Gill sharks are the largest species in their order(Hexanchiformes), with males reaching lengths of 12 feet and females reaching lengths of 18 feet! Belonging to the cow shark family (Hexanchidae), this species has remained relatively unchanged since the early Jurassic period. Their name reflects their distinctive anatomy (extra gill slits) :3

Physical characteristics

The Bluntnose Six-Gill sharks have many distinctive features, such as their streamlined, elongated body, a blunt snout, and a small dorsal fin positioned towards the back of its body. It has grayish-brown skin that helps it blend into its dark surroundings, while a pale belly provides camouflage from below (Countershading). Many people don’t think that Bluntnose sharks have dorsal fins, but that’s untrue! Unlike most sharks, they only have one dorsal fin, however it’s located more posteriorly compared to others. This adaptation is common in bottom-dwelling species as they don’t require the same level of speed as pelagic species! With a dorsal fin that’s positioned closer to the caudal fin, it enables them to make sharper turns and increases maneuverability.

Respiratory features/evolution

As we’ve previously noted, Bluntnose sharks have six gills, but why? The additional gill slit allows the Bluntnose shark to extract oxygen from the water more efficiently, which is a crucial adaptation in deep-sea environments where oxygen is scarce. Older species from the cow shark family have persistently remained unchanged, and continue to find success with a more primitive body.

Habitat

Bluntnose Six-Gill sharks are found all over the world on continental shelves, slopes, abyssal plains, seamounts, and mid ocean ridges. They reside in deep, cold waters between 200-1000 meters in temperate climates, but can be found in shallower waters in cooler climates. Scientists have primarily studied their behavior in shallower waters in high latitudes, but less is known about their behavior in deeper waters.

Migration

Bluntnose Six-Gill sharks exhibit diel vertical migration, which means they migrate vertically through the water column during the day and night. They stay in deeper depths around 600 meters during the day, and then move to shallower depths of around 200 meters during the night. Diel vertical migration isn’t uncommon among smaller marine organisms such as zooplankton, fish and squid. They travel deeper during the daytime to avoid predators, and migrate back to shallower depths at night to feed. Scientists are unsure why Bluntnose sharks exhibit this behavior, BUT I think it’s because they track the abundance of migrating prey items, as they feed on most of the smaller organisms I listed.

Diet

Bluntnose sharks feed on fish, squid, rays crustaceans, and agnathans (hagfish and sea lampreys). They also scavenge carrion and participate in feeding frenzies.

Reproduction

Bluntnose sharks reproduce through ovoviviparity. This means that the eggs hatch inside the female, where embryos develop until they’re ready to be born. Scientists believe their gestation periods last longer than two years. Litter sizes range from 20-110 pups, however it suggest that mortality rates for the pups may be high. Each pup is around 70 cm at birth.

Conservation status

The Bluntnose shark is listed as near threatened on the IUCN list. Its popularity as a sport fish makes it vulnerable to exploitation.

That’s pretty much it :3 all of this is why, you too should love the Bluntnose-Six gill shark 🦈

#ocean#marine biology#science#stemblr#nature#birdblr#oceanblr#micaelyn info dumps#sharks#hehe i love sharks#Bluntnose six gill#my beloved#Bluntnose six-gill

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

tell me about the sunfish

OH BOY DO YOU KNOW HWAT YOU HAVE DONE??? HERE I GO:

(IDs in alt text.)

So there's this family of fish called molidae, yeah? and in molidae there's three families, Mola, Masturus, and Ranzania, and five species.

All of them have weirdo tails, in that their tails are like, gone. Their caudal fin is very stunted and used like a rudder, while anal and dorsal are used to propel. See below.

That's a Mola alexandrini and Mola tecta (drawn by yours truely), aka gian sunfish and hoodwinker sunfish! Molidae start their life as teeny tiny larva only a few cells large, and only a few of the thousands eggs released make it to adulthood. Molas are also the largest boney fish. The largest recorded Mola is M. alexandrini, with the most recent record breaker being about 11 feet long and weighing 6,000 lbs. Thats about 3.4 meters & 2700 kg! !!! WILD.

Despite being ginormous, Molidae as a whole are actually really low in nutritional value. See, the fish of Molidea's diet is soft squishy low calorie things they can inhale. They inhale because they can't close their mouths; they're always open, looking extremely surprised. So they eat things like jellyfish, zooplankton, and squid.

And how they go about eating is really cool, too. All the genus Mola dives thousands of feet in the ocean! Durring the day, most of their prey is down there due to the "diurnal vertical migration"--zooplankton travel up at night and down durring the day. Mola's eyesight isn't the best, so they dive durring the day to have better light.

Funny thing is, they don't have swim bladders. How do they move through the changing pressure? Their bone's and flesh just happen to be about the same density as water, so they just hang out wherever they stop swimming.

Another funny thing, Molidae are cold blooded. And the ocean is cold! this limits how long they can dive for. Older, larger adults can dive for much longer than smaller ones. Regardless, when they come up they have to warm up again, which they do by lying parallel and sunning themselves. Which where the Mola mola's common name comes from! Ocean Sunfish!

The larvea don't sun themselves, though, because they are not the same shape as all. Observe the bean!

The larvae try their best to survive, but most of them die. Thats why Molidae adults produce so many eggs---they (read: have evolved to) to essentially cross their fingers and hope some of them survive to adulthood.

Once adults, their survival chances greatly increase for a lot of reasons. One, their skin is mostly tough cartilage, hard to bite through, though sea lions and orcas do try. Then, like said before, they are pretty low in nutritional value. And finally, that I know of, they are open ocean fish. It doesn't always feel like it, but the ocean is very big. It's not often that molidae come across predators.

They do come across reefs fairly often though, and there are some interesting behaviors they exhibit. Like many other fishes, they let cleaner fish clean them. For more pesky parasites, they float at the very surface of the water and let seabirds eat the parasites off their skin.

Speaking of skin, i most recently learned that M. alexandrini changes color, and it can do it quite rapidly. It seems like when they are startled they can make their patterns more bold, a display showing just how large they really are. These patterns remain relatively stable & can be used for identification.

#moliae#inbox#sunfish#facts facts facts#i love ocean sunfish#if you know other stuff PLEASEEEE tell me#taropost#science#facts#science facts#!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

very tired but my brain suddenly decided i needed to learn red panda facts. anyways theyre not related to pandas and are mostly closely related to raccoons with some genetic similarities to mustelids (weasels, otters, and wolverines), their diet consists primarily of bamboo but they also eat flowers, eggs, birds, and small mammals, they migrate vertically, have six digits on their front paws, give birth in the wild from june-september, and make noises similar to duck quacks

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here's every Eurostrate family

Actaeonulus martus

The Actaeonulidae are the most basal Tachyungulate family. They’re part of a once widespread superfamily, the Acteonuloidea, that is now restricted to only the Western continent’s tropical and temperate rainforests, having been mostly outcompeted in drier environments by the Ovopilosan Leporicaudidae. They are mostly generalist herbivores, although they supplement their diet with Micropods from time to time, eating low vegetation, underground tubers, rhizomes, roots, fallen leaves and sometimes aquatic plants.

Myophrys parvotorosus

The Sciurungulatidae are an arboreal family of Notalungulates, a group that rafted from the Western continent to Notalia. They are folivorous and granivorous, often relying to coprophagy to gather the latter.

Cerafrons striatus

The Notalungulatidae are the most common herbivores of Notalia. They inhabit humid forests, rainforests, shrubland, taiga, the steppe and the desert. They are extremely diverse and include a vast range of diets and specialisations.

Algorhynchus rubeatus

The Algylotheridae are a family of relatively small Apterygotherians that inhabit the underwater forests of Phycophorans and unicellular macroalgae like organisms. Their mode of swimming is reminiscent of anguilliform and sub-carangiform locomotion, although done vertically. They are mostly herbivores, although some may supplement their diets with soft bodied marine invertebrates.

Euthycampus xanthoparia

The Gymnoapteridae are family of big and medium-sized Apterygotherians, mostly present in tropical and temperate waters. They live and forage in herds, along the borders of the underwater forests. They are specialised for speed, but when in herds they are capable to mob predators, either scaring them away or downright killing them.

Thorakitacampus cynthiae

The Oploapteridae are the biggest marine herbivores of the planet. They have on average a slower metabolism than most Tachyungulates, since they are particularly present on the poles. Most live in either small herds or family groups.

Tholotragus jubatus

The Tholocephalidae are a clade of medium-sized mountain and desert dwelling herbivores inhabiting the Eastern continent’s mountain range and its southern desert, the two minor eastern mountain ranges of the Western continent and the southernmost part of the main western mountain range. They live in herds and males compete seasonally for mates and harems through headbutting.

Ennateleutoceros alienoris

The Actaeonidae are a family of medium-sized herbivores that inhabit the temperate forests, shrubland and savanna. They wrestle with their single antler, that they shed after mating season, and form seasonal harems.

Rhomphaeoceros nigris

The Ceratidae are a medium to big herbivores with a range similar to Actaeonids. They form harems and either stab, fence or wrestle their opponents for mates.

Microungulodon pygmaeus

The Anoceratidae are a family of small to big herbivores inhabiting the taiga and tundra of the Western and Eastern continent. They compete for mates through biting, or in some species penis fencing. Many species exhibit migrating behaviours, but most of the smaller members live in the same area all year round.

#spec evo#spec bio#speculative evolution#speculative biology#artwork#digital art#worldbuilding#planet opi

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today’s duck of the day is Eurasian green-winged Teal!

A small dabbling duck that’s really widespread in temperate Eurasia and is famous for its iridescent emerald green feathers! Its diet changes between seasons. Feeding on crustaceans,mollusks and insects during breeding season and switching to a seed based diet during winter. They’re strongly migratory and migrate to south during winter. And are known to be gregarious outside of breeding season,forming huge flocks

Previously it was considered that the American green winged teals and Eurasian winged teals were the same species due to their similar appearance but are actually quite different both on behavioural, molecular and morphological level and are now considered two distinct species.

The main physical difference between the two is a white stripe on their bodies. Eurasian teals have a horizontal stripe under their wings while American teals have a vertical stripe near the chest.

Did you know? The word for the color teal comes from the coloration of teal ducks!

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

IM SORRY FOR FORGETTING ABT THE FISH FOR YESTERDAY i was cleaning my closet out. :] my back hurts now. so heres a 2 for 1

The whale shark (Rhincodon typus) is a slow-moving, filter-feeding carpet shark and the largest known extant fish species. The largest confirmed individual had a length of 18.8 m (61.7 ft). The whale shark holds many records for size in the animal kingdom, most notably being by far the largest living nonmammalian vertebrate. It is the sole member of the genus Rhincodon and the only extant member of the family Rhincodontidae, which belongs to the subclass Elasmobranchii in the class Chondrichthyes. Before 1984 it was classified as Rhiniodon into Rhinodontidae.

The whale shark is found in open waters of the tropical oceans and is rarely found in water below 21 °C (70 °F).[2] Studies looking at vertebral growth bands and the growth rates of free-swimming sharks have estimated whale shark lifespans at 80–130 years. Whale sharks have very large mouths and are filter feeders, which is a feeding mode that occurs in only two other sharks, the megamouth shark and the basking shark. They feed almost exclusively on plankton and small fishes and pose no threat to humans.

The species was distinguished in April 1828 after the harpooning of a 4.6 m (15 ft) specimen in Table Bay, South Africa. Andrew Smith, a military doctor associated with British troops stationed in Cape Town, described it the following year. The name "whale shark" refers to the fish's size: it is as large as some species of whale. In addition, its filter feeding habits are not unlike those of baleen whales.

The frilled shark (Chlamydoselachus anguineus) also known as the lizard shark, and the southern African frilled shark (Chlamydoselachus africana) are the two extant species of shark in the family Chlamydoselachidae. The frilled shark is considered a living fossil, because of its primitive, anguilliform (eel-like) physical traits, such as a dark-brown color, amphistyly (the articulation of the jaws to the cranium), and a 2.0 m (6.6 ft)–long body, which has dorsal, pelvic, and anal fins located towards the tail. The common name, frilled shark, derives from the fringed appearance of the six pairs of gill slits at the shark's throat.

The two species of frilled shark are distributed throughout regions of the Atlantic and the Pacific oceans, usually in the waters of the outer continental shelf and of the upper continental slope, where the sharks usually live near the ocean floor, near biologically productive areas of the ecosystem. To live on a diet of cephalopods, smaller sharks, and bony fish, the frilled shark practices diel vertical migration to feed at night at the surface of the ocean. When hunting food, the frilled shark curls its tail against a rock and moves like an eel, bending and lunging to capture and swallow whole prey with its long and flexible jaws, which are equipped with 300 recurved, needle-like teeth.

Reproductively, the two species of frilled shark, C. anguineus and C. africana, are aplacental viviparous animals, born of an egg, without a placenta to the mother shark. Contained within egg capsules, the shark embryos develop in the body of the mother shark; at birth, the infant sharks emerge from their egg capsules in the uterus, where they feed on yolk. Although it has no distinct breeding season, the gestation period of the frilled shark can be up to 3.5 years long, to produce a litter of 2–15 shark pups. Usually caught as bycatch in commercial fishing, the frilled shark has some economic value as a meat and as fishmeal; and has been caught from depths of 1,570 m (5,150 ft), although its occurrence is uncommon below 1,200 m (3,900 ft); whereas in Suruga Bay, Japan, the frilled shark commonly occurs at depths of 50–200 m (160–660 ft).

really fond of the frilled shark i think it is lovelhy and a little ugly but that is what makes it lovely

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Formula One of the marine world

Swordfish, often referred to as the "Formula One of the sea," are renowned for their incredible speed and agility in the ocean. These magnificent creatures are built for fast, long-distance swimming, possessing a sleek, streamlined body that allows them to cut through the water with minimal resistance. Their powerful, crescent-shaped tails provide the thrust needed to reach speeds of up to 60 miles per hour, making them one of the fastest fish in the ocean. The swordfish's distinctive long, flat bill, resembling a sword, is not only a defining feature but also a formidable weapon. This bill can be used to slash at prey, stunning it and making it easier to capture, although recent studies suggest they more commonly use their speed and agility to catch prey rather than relying on their "sword."

Swordfish are pelagic predators, meaning they inhabit the open ocean rather than coastal waters. They are highly migratory, traveling across vast distances in search of food and optimal breeding conditions. These migrations often span thousands of miles and can include vertical movements from the surface to deep waters, sometimes diving to depths of over 2,000 feet. Their ability to thrive in such diverse environments is partly due to their unique physiological adaptations. Swordfish are among the few fish species capable of thermoregulation, allowing them to maintain a higher body temperature than the surrounding water. This adaptation provides them with a significant advantage in cold, deep waters, enabling faster swimming and enhanced hunting abilities.

The diet of a swordfish is as varied as their migratory patterns. They are opportunistic feeders, preying on a wide range of fish and squid. Their hunting strategy involves using their speed and agility to outmaneuver and capture fast-moving prey. Swordfish often hunt at night when many of their prey species migrate closer to the surface, making them more accessible. During the day, swordfish can be found at greater depths, where they are less visible to predators and able to conserve energy. This vertical migration pattern is a key aspect of their survival strategy, allowing them to exploit different ecological niches and reduce competition with other large predators.

Reproduction in swordfish is another fascinating aspect of their biology. They are oviparous, meaning they lay eggs, with females capable of producing millions of eggs in a single spawning season. These eggs are released into the open ocean, where fertilization occurs externally. The larvae that hatch are initially part of the plankton community, drifting with the currents until they develop the ability to swim actively. Juvenile swordfish grow rapidly, reaching significant sizes within a few years. This rapid growth rate is essential for their survival, as larger individuals are less vulnerable to predation.

Despite their impressive capabilities and adaptations, swordfish face several threats that have raised concerns among conservationists. Overfishing is a significant issue, driven by the high demand for swordfish in both commercial and recreational fisheries. Longline fishing, in particular, poses a major threat, as it not only captures large numbers of swordfish but also results in significant bycatch of other marine species, including sharks, turtles, and seabirds. This bycatch issue highlights the broader environmental impact of swordfish fisheries and the need for sustainable fishing practices.

Efforts to manage and conserve swordfish populations are ongoing, with various international and regional agreements in place to regulate fishing practices and protect critical habitats. The International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) is one such organization that oversees the management of swordfish stocks in the Atlantic Ocean. Measures implemented by ICCAT and other regulatory bodies include setting catch limits, enforcing minimum size requirements, and promoting the use of bycatch reduction devices in longline fisheries. These efforts aim to ensure the long-term sustainability of swordfish populations while balancing the economic interests of the fishing industry.

In addition to regulatory measures, scientific research plays a crucial role in informing conservation strategies for swordfish. Studies on their migratory patterns, reproductive biology, and population dynamics provide valuable data that can be used to assess the health of swordfish stocks and identify key areas for protection. Tagging and tracking programs, where individual swordfish are fitted with satellite tags, have provided insights into their movements and behavior, revealing important information about their habitat use and migration routes. This knowledge is essential for developing effective management plans that consider the full range of swordfish's ecological needs.

Public awareness and education are also vital components of swordfish conservation. By raising awareness about the importance of sustainable fishing practices and the ecological role of swordfish, conservation organizations can garner support for protective measures and encourage responsible consumer behavior. Choosing sustainably sourced seafood, supporting fisheries that adhere to best practices, and advocating for stronger regulations are ways in which individuals can contribute to the conservation of swordfish and other marine species.

In popular culture, swordfish are often depicted as symbols of strength and speed, reflecting their status as the "Formula One of the sea." This reputation is well-deserved, given their remarkable adaptations and prowess as predators. However, it is important to recognize that their survival depends on the health of the broader marine ecosystem and the actions we take to protect it. By appreciating the complexity and beauty of swordfish, we can better understand the importance of preserving our oceans and the incredible diversity of life they support.

0 notes

Text

Boar fish

boar fish

The boarfish, scientifically known as Capros aper, is a small and distinctive marine fish that belongs to the family Caproidae. Found in the Eastern Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea, and parts of the Western Indian Ocean, the boarfish has garnered attention not only for its unique appearance but also for its ecological role and occasional presence in commercial fisheries.

One of the most striking features of the boarfish is its appearance. It has a compressed, disc-shaped body with a distinctive upward-pointing snout, resembling the snout of a pig, which contributes to its common name, "boarfish." The body is typically silver or pinkish in color, and the scales are relatively large. The dorsal fin is elongated, and the anal fin has three spines. These physical characteristics make the boarfish easily distinguishable from other species in its habitat.

Boarfish are primarily found in deep waters, often dwelling at depths ranging from 200 to 800 meters (656 to 2625 feet). They prefer areas with rocky or sandy substrates, and their distribution is associated with continental slopes and seamounts. While they are generally considered a deep-sea species, they may migrate vertically in the water column, moving closer to the surface during the night for feeding.

In terms of diet, boarfish are opportunistic feeders. They primarily consume small invertebrates, such as crustaceans and zooplankton. The upward orientation of their mouth and snout allows them to feed efficiently on prey items above them in the water column.

The reproductive behavior of boarfish is not extensively documented, but it is known that they are oviparous, meaning they lay eggs. They likely release buoyant eggs into the water, where they drift until hatching. The larvae then undergo a pelagic phase before settling to the ocean floor.

While boarfish are not typically a target species for commercial fisheries, they are occasionally caught incidentally in deep-sea trawl fisheries targeting other species. Their flesh is considered edible, and some regions include them in their catch. However, due to their relatively small size and the depths at which they are found, they are not a primary focus of commercial exploitation.

Studies on the population dynamics and ecology of boarfish are ongoing, as the species plays a role in the complex deep-sea ecosystems it inhabits. The interactions between boarfish and their prey, as well as their role as prey for larger species, contribute to the overall biodiversity and ecological balance in their deep-sea habitats.

0 notes

Text

The Early Temperocene: 140 million years post-establishment

Not Quite Flight: Arboreal Gliders of the Temperocene

Since the Middle Rodentocene, the skies of HP-02017 had been filled with ratbats, quadrupedal flyers of distant relation to the squizzels and lemunkies, that had dominated the air for eons. And much more recently, they were joined in the air by the pterodents: airborne podotheres that, akin to the ratbats, would emerge from gliders, before truly taking to the skies on their own power.

That is not to say, however, that gliding was a prerequisite to true flight, as, in the Temperocene, several small lineages convergently had developed this form of half-flight-- and stayed there. Evolution, being a random process with no goal except survival, allowed these seemingly-transitional forms to become a niche all their own, and as long as this partial airborne ability allowed them to thrive in their environment there was little need to progress further: unless, by chance, changing ecosystems or unexploited niches goaded them in the right direction.

One such species is the eyespot parachu (Volaticosciurumys oculus), a gliding kiterat descended from the lineage that would give rise to the ratbats: unlike its relatives, however, it would only use this ability to move from tree to tree and not much further. This was an easy way to traverse the forest, where the parachu could easily seek out its favorite food-- insects in bark-- as well as the sugary tree sap it spills while gnawing for bugs, supplementing its protein-rich diet with carbohydrates. The parachu thus is well suited for its current niche, and thus, unlike its ratbat cousins, has not evolved its patagia into a proper wing. The patagia, while used for gilding, serves another practical purpose: it bears large spot markings resembling false eyes, which it uses in defense: when startled by a predator, it spreads its patagia instantly, creating the illusion of a larger and more deadly creature, halting the predator in shock and giving the parachu time to glide to safety.

While the parachu glides with membranes of furred skin, stretched between its ankles and wrists, another common arboreal glider uses entirely different structures to get airborne: the plumetail wingle (Squamopteromys caudopluma), a rattile of the shingle family, particularly the lineage of arboreal tree shingles. Equipped with scaly plates modified from hair, most shingles use them for armor: using hypertrophied hair erector muscles to raise their plates or clamp them down. This movability, however, allows the wingle to utilize its plates, now thin and papery with a hard central shaft, for a new purpose entirely-- spreading them out into a gliding surface, with its tail also adorned with plumes of its own that allow it to change direction. Wingles are omnivores, and use their skill to roam the forest quickly to find a meal: they are not picky eaters, and fruit, fungi, bark, sap, nectar, insects and occasionally smaller rattiles are well on the menu.

However, evolution is ever ongoing, and different species respond differently to changing pressures: forcing them to either become more specialized or remain generalist. With the abundance of ratbats equipped with true flight, the parachu does well staying in such a niche. The wingle, on the other hand, is pressured to migrate further and further by competition from other rattiles diversifying in the Temperocene: and gradually, the modified erector muscles that once just folded and spread their plates developed brief vertical twitches to prolong their glides to access new trees-- in ever increasing distances. Soon, in time, the ratbats and pterodents will be joined by new company in the sky ever more crowded and diverse: by something completely unlike anything that had ever flown before.

▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fish of the Day

today's fish of the day is the cookiecutter shark!

The cookiecutter shark, also known as the cigar shark, scientific name Isistius brasiliensis, is well known for their distinctive bite marks. Often referred to as "the leach of the shark world" the cookiecutter shark has an extensive diet. Any animal that is large enough to support a bite from a cookiecutter shark, can and will be bit. prey includes, but is not limited to: whales, dolphins, seals, dugongs, almost every shark that shares a range with cookie cutter sharks (great white, blue, megamouth, tigar, etc), bony fishes, squids and other soft bodied animals. That includes humans, and biting of humans by cookiecutter sharks rises every year.

The cookiecutter shark is parasitic, leaving carter wounds that measure about 2 inches across and about 7cm deep into its prey. The shark can make these marks through several adaptations of the mouth. The spiracles, behind the eyes, close, and the tongue is retracted, to create a suction to their prey, sealing them together. Then, the shark will twist around, rotating the body in a circle, aided by a saw-like movement of the jaw, which moves the teeth back and forth. This is how they feed. This diet supports them getting as large as 17-22 inches in length.

The range for these fish stretches from the latitude of 20 degrees North to 20 degrees South all across the world, although in the warmer seasons for each hemisphere they can migrate as far as 30 degrees North and South respectively. The cookiecutter shark prefers living near the equator, in tropical or warmer temperate areas. This shark takes place in diel vertical migration, a kind of daily migration that occurs at night where animals that tend to live in deeper waters come to the surface. The cookiecutter shark can travel up to 2 miles up and down in the migration each day!

A smaller known fact other than this shark's feeding habits, is based on its bioluminescence! The cookiecutter shark has the strongest bioluminescence of any shark species known. A darker collar on the underside of the shark is thought to act as a lure for attracting prey. Their life is similar to that of other dogfish sharks, despite their many adaptations. A litter of pups bore at a time is between 6-12 and are gestated in the female by sustaining off of the yolk until birth. When born the bioluminescent collar is yet to form, and they are only 6-6 inches in length. Sexual maturity is achieved once they reach 14-15 inches in length, and it is unknown how long their lifespans are.

Have a wonderful Monday, everyone!

#ish#fish of the day#fishblr#fishposting#aquatic biology#marine biology#animal facts#animal#animals#fishes#informative#education#aquatic#aquatic life#nature#river#ocean#shark#sharks#cigar shark#cookiecutter shark#cookie cutter shark#Isistius brasiliensis

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

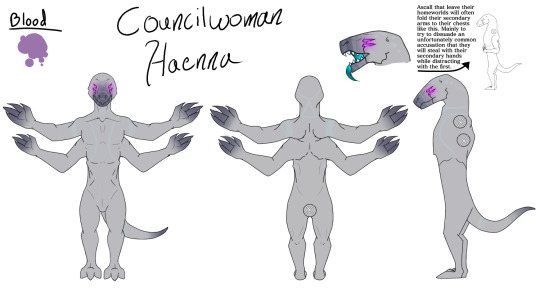

This is about as far as I got for their society and stuff, cause I got tired, but feel free to ask any questions if I left something out that you wanna know about!

Also, I’ll draw some clothing for the Aschall later.

Thiery is a doctor turned field medic. She is niece to Councilwoman Haenna. Her aunt took her in after her parents disappeared while she was little.

Councilwoman Haenna is a prominent figure in Ascall Society. Despite not being one of the representatives of her clan, she is often asked to attend meetings via holo/comm. She is very protective of her son, and of Thiery, having lost her other two children.

Teyrdok “Tayer” is the Ascall Councilor’s only child, and is cousin to Thiery. He and his small family of three are some of the few on the Citadel who haven’t taken the Vow of Silence. In his hometown, he helps mentors train young Aschall who have turned 17.

Average 5′6″ Human compared to an Ascall.

[Homeworlds]

- Their homeworlds, Annivus and Davos, orbit in close proximity to a very powerful sun. One that burns most to a crisp if they aren’t adapted to living on the planets’ surfaces. So, very very early on in their evolution, the Ascall moved underground, into caverns and caves.

- The size of the planets is comparable to Neptune (Davos), and Uranus (Annivus).

- Nowadays, there are vast cities built into the dense stone. The cities and towns span across the entirety of their planets, and have different levels beneath the first you enter in. Some of the largest populations can have thousands of feet worth of levels.

- Although the cities have elevators and escalators to help span the distance, smaller towns will have ramps and stairs, and even smaller villas will have vertical tunnels between each level, with foot and hand holds dug into the walls. The tunnels are large enough to fit a Krogan, and often require you to wear some sort of harness and tether in case you aren’t used to the structures or can’t hold onto the holds. The tether attaches to a sturdy metal pipe off to the left of the ‘ladder’, and can be clamped tightly to stop one from falling.

- Most of the planets’ surfaces is completely barren, mostly stone valleys, plains, and mountains. But there are large oases (oasis plural), dotted where the sunlight touches least. And there, hardy plants grow. The plants are largely inedible to Ascall, but not to the Betrite that frequent the oases and migrate to find more.

- Underground fresh water rivers, springs, and aquifers are primarily how the Ascall get hydrated. Their largest cities were built near the aquifers, and the towns are closer to rivers and springs.

- The oases evaporate when the sun is in direct contact with them, causing local wild fauna to migrate daily to more shady areas of the planet to find better water sources. The bodies of water refill rapidly when the sun is not in direct contact with them. It storms at night, the evaporated water refilling the empty pools.

- On occasion, the storms can get to be so bad, that thick metal storm doors will close over the entrances to the cities and towns.

- There are few entrances to the underground. Possibly four at most. Vast tunnels with an occasional shop in the walls connect all of the populations.

[Society]

- Generally, they are a rather friendly people. They are very fond of Found Family and will often adopt others into their family. If you ever go to visit the Ascall homeworlds, you can find people of most species, either visiting, or having been raised there.

- Because of this eagerness to include others, there is a stark lack of clan names, or group identifying names. Usually, when talking about a specific clan, the entirety will be referred to as [Insert Name]’s Clan. Generally, the clans are old enough, and their leaders are recognized enough that they can easily avoid tacking a name onto a clan.

- While there are no IDs for the clans, there are prominent 3 leaders. Chosen by the clans themselves to represent them when decisions must be made for either an individual clan’s problems, or for the species as a whole. One leader is selected for their knowledge of the clan’s current agricultural/cultural representation, another is selected for the medical representation, and the third is selected for the Protection representation.

- Ascall have no straight military. Rather each child born into a family is taught the basics of weaponry, protection, and guerilla tactics at age 17. If they so choose, when the need arises, they can volunteer to help protect their people (IE; The Reaper Invasion).

- Many Ascall do volunteer when necessary. But it is often a last resort. If they cannot see any way to reason with or calm their aggressor, they will take up arms.

- *Most Ascall that leave their homeworld to visit or live on the Citadel will often take a Vow of Silence. Their ability to copy a vast majority of voices leaves a lot of people unsettled, so in attempt to quell any suspicions, or accusations, the Vow of Silence is offered to those going to the Citadel, by an Ascall Ambassador. It can be refused, or accepted, but it is solely up to the recipient.

- The Vow of Silence is only in effect while on the Citadel, and the Ascall that accept it can speak when not on Citadel bound transport, or on the Citadel itself. The Vow in and of itself is just a strip of fabric often tied around the right wrist of their secondary arms.

- **While on their homeworlds, those that chose to walk on 4/6 of their limbs will have tough gloves for their secondary hands. It’s considered an offense to greet others while wearing the gloves, or to eat with them on, as it’s seen as eating/greeting with all of the dirt and filth left behind on the ground from people walking about.

- Ascall have adapted a lot of names from other species, you will commonly find Ascall with human, Turian, Quarian, Krogan, Salarian, Asari, etc. names.

[Flora and Fauna]

Betrite: Large thick plated herbivores, similar in weight and height to human draft horses. They travel in herds, and wild Betrite are largely aggressive, but easily fooled by mimicry. They will always investigate the sounds of other injured Betrite. They have heads similarly shaped to Varren, two small eyes, large nostrils, round disk shaped ears, and six thick legs with padded paws. Although they can’t curl up like Armadillos do, their plating patterns are quite similar to them.

Domesticated Betrite are far less aggressive, but also far less inclined to do anything other than what they want to do. They’re very stubborn creatures.

[Biology]

- First and foremost, the Ascall are an extremely flexible species. Soft flesh, and collapsible spines allow them to squeeze into places that would be hard to reach for most others, even despite their tall stature. Before they had the abilities to create cities and towns within the caverns they inhabited, when they were still primarily a hunter-gatherer society, they would force their way into whatever dark crevice they could, if they couldn’t make it back to their caves before sunrise.

- Also, an evolutionary trait that stuck with them through the generations, is a secondary larynx. When both larynxes are in use, they can mimic most if not all sounds, and most voices.* Some millennia before they had begun to farm the larger prey animals that could walk their planets’ surfaces, they would mimic cries of injured members of the Betrite. This in turn would lure prey to the cave/cavern openings to be ambushed. This saved them from having to go out into the damaging sunlight when their food stores began to run low.

- Due to a diet of mostly glowing fungi that grows in the caverns they live in, and what meat they can get, combined with often living in darkness, Ascall have developed Bioluminescent patterns. Each pattern is unique to that Ascall specifically. Although relatives may have similar markings and colors, no two will never ever be the same, like a human fingerprint. The glowing mouths are a side effect sort of evolution. Their mouths will always glow, regardless of whether in light. But their markings will only glow in low light or in complete darkness.

- Ascalls are often dark or muted colors, but fade to gray as they grow older. Councilwoman Haenna used to be a rich dark purple but has grayed out as she reached her fifties.

- The purpose of the secondary arms is a question that has largely gone unanswered, due to a lack of data and evidence. But on their homeworlds, most Ascall will either pick between walking bipedal, or using their secondary hands and their legs, while their first hands will remain free to grab things.**

- All reproductive organs, regardless of sex, are hidden in their bodies until time for their use.

- Ascall have rather durable internal organs, lengthened to enable their flexibility, but not resistant to being punctured.

- Ascall have litters of 2-4 young.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rissa

Red-Legged Kittiwake by the US Fish and Wildlife Service, in the Public Domain

Etymology: The Old Norse Name for the Black-Legged Kittiwake

First Described By: Stephens, 1826

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Aequorlitornithes, Charadriiformes, Lari, Larida, Laridae, Larinae

Referred Species: R. tridactyla (Black-Legged Kittiwake), R. brevirostris (Red-Legged Kittiwake), R. estesi

Status: Extinct - Extant, Vulnerable

Time and Place: Between 4.9 million years ago and today, from the Zanclean of the Pliocene until the Holocene of the Quaternary

The Kittiwake are known from ocean habitats all across the Northern Hemisphere, in both the Pacific and Atlantic oceans

Physical Description: The Kittiwake are large, gulls, ranging between 35 and 42 centimeters in length - the living Black-Legged Kittiwake is usually slightly larger than the Red-Legged Kittiwake. These birds have grey wings and backs, with white bodies and heads and tails. The tips of their tails are black, and they have small yellow beaks. The two species mainly differ how you’d think, based on the names: the Red-Legged species have orange legs, and the Black-Legged species has dark grey legs.

Black-Legged Kittiwake by the US Fish and Wildlife Service, in the Public Domain

Diet: Kittiwake eat fish, squid, and other small marine animals.

Red-Legged Kittiwake by Dick Daniels, CC BY-SA 3.0

Behavior: These bird will feed all throughout the day and night, soaring above the water and searching for sources of food in both deep sea and shoreline locations. Their preferred prey does vary based on location, and the prey they bring back to their young also varies extensively by location. They will also scavenge carcasses found along the shore. They tend to search for food in large flocks, soaring over the water together and finding sources of fish and critters in the water. They communicate with loud calls, for which they are named: “kitt-i-waake! Kitt-i-waake!” and the two species differ in the Red-Legged species having a higher-pitched call.

Black-Legged Kittiwake by Andreas Trepte, CC BY-SA 2.5

Kittiwake breed during the spring, nesting in late spring with most of the young hatching in the middle of the summer. They also tend to breed in similar locations - in the Pacific, where the ranges of the two species overlap, they’ll form large mixed nesting colonies. The nests are built out of mud and formed into cups that are placed on the cliffs. The clutches usually are between one to three eggs, which are incubated for a month. The chicks are very fluffy and grey when hatching, and they stay in the nest for about four weeks. After that, they stay with the parents for a little while after, and are aided in finding food and making it to the winter season. They tend to breed for the first time at four years of age. These birds will migrate between locations - for example, the Red-Legged species will stay near the Bering Sea in winter and then move to Japan in the summer - but these movements tend to be moving back and for the between breeding colonies and the open ocean during the winter non-breeding season. The migration patterns of these birds also tend to change from population to population - which makes some populations of Kittiwake more vulnerable to extinction than others, as they are more exposed to dangerous locations and storms than others.

Red-Legged Kittiwake Chick, by the US Fish and Wildlife Service, in the Public Domain

Ecosystem: These birds live on the coasts of Northern seas, and are often found soaring over the oceans; they tend to favor vertical cliffs on islands and other locations for breeding. They do need to find fresh water, especially in the breeding season; but beyond that they favor pelagic locations. Major storms do cause wrecks onto land. They are preyed upon by other birds, especially Gyrfalcons, Skuas, and other Gulls.

Black-Legged Kittiwake by Dick Daniels, CC BY-SA 3.0

Other: The Kittiwake are, sadly, vulnerable to extinction. Despite large increases in range and population during the 20th century, they have been on a very large-scale decline, especially in the Atlantic. Each species only has a small handful of viable breeding sites at this point, and the population is in sharp decline all over - though some populations have shown some recovery. This decline in population appears to be a reduction in food supply due to excessive commercial fishing. Climate change has also resulted in shifting of prey species, and the changing climate has also lead to habitat inviability for these birds. Diets poor in lipids and other substances - a side effect of these changes - also makes it difficult for the chicks to grow to adulthood. Oil spills and pollution, as well as bycatch, have lead to direct deaths of the Kittiwake across the globe. It also seems to be hunted extensively in certain places such as Greenland. Nesting areas are protected in some countries, but not in the United States, where the decline has been most dramatic.

Red-Legged Kittiwake by Dick Daniels, CC BY-SA 3.0

Species Differences: R. estesi is an extinct genus of this species, and differed from the living species in actually being bigger than the living ones - and having musculature different to match. It lived in the current range of the Black-Legged Kittiwake. Today, the Black-Legged Kittiwake is known from the Northern Pacific and Atlantic, and is larger than the Red-Legged variety; in addition, in the past it was known from northern Greenland. The Red-Legged Kittiwake is known from the northernmost part of the Pacific, and, of course, has different colored legs than its cousin.

Black-Legged Kittiwake by Yathin S. Krishnappa, CC BY-SA 3.0

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Bennike, O. 1987. Quaternary geology and biology of the Jorgen Bronlund Fjord area, North Greenland. Meddelelser om Gronland. Geoscience 18:1-23

Burger, J., Gochfeld, M., Kirwan, G.M., Christie, D.A., Garcia, E.F.J. & Sharpe, C.J. (2019). Black-legged Kittiwake (Rissa tridactyla). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive.

Burger, J., Gochfeld, M. & Garcia, E.F.J. (2019). Red-legged Kittiwake (Rissa brevirostris). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Chandler, R. M. 1990. Fossil birds of the San Diego Formation, Late Pliocene, Blancan, San Diego County, California. Ornithological Monographs 44:73-161

Clements, J. F., T. S. Schulenberg, M. J. Iliff, D. Roberson, T. A. Fredericks, B. L. Sullivan, and C. L. Wood. 2017. The eBird/Clements checklist of birds of the world: v2017

Guthrie, D. A. 1992. A late Pleistocene avifauna from San Miguel Island, California. Science Series (Los Angeles) 36:319-327

Harrison, C. J. O. 1987. Pleistocene and prehistoric birds of south-west Britain. Proceedings of the University of Bristol Spelaeological Society 18(1):81-104

Jobling, J. A. 2010. The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. Christopher Helm Publishing, A&C Black Publishers Ltd, London.

Smith, N. A. 2011. Taxonomic revision and phylogenetic analysis of the flightless Mancallinae (Aves, Pan-Alcidae). ZooKeys 91:1-116

#Kittiwake#Rissa#Dinosaur#Bird#Gull#birds#Prehistoric Life#Palaeoblr#Birblr#Factfile#Dinosaurs#Red-Legged Kittiwake#Black-Legged Kittiwake#Rissa estesi#Rissa tridactyla#Rissa brevirostris#Aequorlitornithian#Charadriiform#Quaternary#Neogene#North America#Eurasia#Piscivore#Water Wednesday#paleontology#prehistory#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day

119 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The frilled shark (Chlamydoselachus anguineus) and the southern African frilled shark (Chlamydoselachus africana) are the two extant species of shark in the family Chlamydoselachidae. The frilled shark is considered a living fossil, because of its primitive, anguilliform (eel-like) physical traits, such as a dark-brown color, amphistyly (the articulation of the jaws to the cranium), and a 2.0 m (6.6 ft)–long body, which has dorsal, pelvic, and anal fins located towards the tail. The common name, frilled shark, derives from the fringed appearance of the six pairs of gill slits at the shark's throat.

The two species of frilled shark are distributed throughout regions of the Atlantic and the Pacific oceans, usually in the waters of the outer continental shelf and of the upper continental slope, where the shivers usually live near the ocean floor, near biologically productive areas of the ecosystem. To live on a diet of cephalopods, smaller sharks, and bony fish, the frilled shark practices diel vertical migration to feed at night at the surface of the ocean. When hunting food, the frilled shark moves like an eel, bending and lunging to capture and swallow whole prey with its long and flexible jaws, which are equipped with 300 recurved, needle-like teeth.

Reproductively, the two species of frilled shark, C. anguineus and C. africana, are aplacental viviparous animals, born of an egg, without a placenta to the mother shark. Contained within chondrichthyes (egg capsules) the shark embryos develop in the mother's body; at birth, the infant sharks emerge from their egg capsules in the uterus, where they feed on yolk. Although it has no distinct breeding season, the gestation period of the frilled shark can be up to 3.5 years long, to produce a litter of 2–15 shark pups. Usually caught as bycatch in commercial fishing, the frilled shark has some economic value as a meat and as fishmeal; and has been caught from depths of 1,570 m (5,150 ft), although its occurrence is uncommon below 1,200 m (3,900 ft); whereas in Suruga Bay, Japan, the frilled shark commonly occurs at depths of 50–200 m (160–660 ft).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

TAFAKKUR: Part 127

The Hummingbird

Research on hummingbirds (also known as nectar birds or Colibris), the smallest of the 9,800 bird species living today, has revealed remarkable facts. The world’s smallest birds are equipped with mind-blowing structures and functions that push all physiological and anatomical boundaries. The bee hummingbird (Mellisuga helenae), considered to be the smallest bird in the world, is only 1.96-inch-long and weighs 0.06 ounces.

There are around 330-340 species of hummingbird and they live only in North and South America and the nearby oceanic islands. With their colorful feathers, they are some of the most beautiful birds.

How the hummingbird flies

A hummingbird flaps its wings so fast that the motion cannot be seen by the human eye but only detected through special cameras. The wings move at an incredible speed in a seemingly complex pattern, drawing circles back and forth 50 to 80 times per second, depending on the species. Under the genus Colibri, the horned Sungem (Heliactin bilophus) species flaps its wings 90 times per second; the purple amethyst Colibri (Calliphlox amethystina) flaps its 80 times per second. This speed increases up to 200 per second during a short spike while escaping from an enemy. Moving back and forth, the wings oscillate in the form of the figure 8 in the air. While in most other birds the movement of the wings produces the power to lift up and down, Hummingbirds, like helicopters, can perform movements such as hanging in the air or standing steadily as well as flying backward or rising in a vertical direction.

Metabolic rate and energy consumption

Flying requires a lot of energy. The amount of energy spent is related to the bird’s body size and flapping speed. In this regard, given that a colibri flaps its wings 80 times per second, it takes a great deal of energy to maintain such a rapid movement. The colibri’s chest muscles were perfectly created for flapping quickly and take up 40% of the hummingbird’s total body mass. Therefore, a colibri consumes more energy than other birds; it’s basically a fighter jet.

In order to meet this high energy demand, the amount of nectar a colibri consumes every day has to be equal to their body weight. Living at such a high metabolic rate requires a fine adjustment of food consumptions with precise calculations.

Such a high food intake requires a high metabolism – and thus, the need for oxygen increases dramatically. When the need for oxygen increases, there can be two kinds of conditions. Those animals with very large lungs can intake a lot of air at once. And those with smaller lungs can produce the required oxygen by breathing many times a minute. Colibri or Nectar birds are the ones that can breathe the most in one minute. The lungs of the world’s smallest birds breathe 250 times per minute to transfer oxygen to their hearts weighing a mere 0.003 ounces and beating 1,200 times per minute.

Toronto University’s Kenneth C. Welch Jr. studied the metabolism of hummingbirds for more than 10 years. He discovered that there is a relationship between the size of hummingbirds, energy efficiency, and oxygen consumption, and that larger hummingbirds are more efficient energy users than smaller ones. A hummingbird can take 2.44 cubic inches of oxygen per 0.03 ounces an hour. When a small weight is added to the bird, this amount increases to 3.66 cubic inches, and their tissues use oxygen very efficiently.

Energy requirements

A hummingbird’s metabolism is the fastest among all vertebrates. It needs to eat almost constantly to get the energy it needs to produce fuel for its breathtaking metabolism, which functions like a power plant. It receives nectar from 2,000 flowers every day. If we humans could work at this bird’s energy levels, we’d have to eat about 1,300 sandwiches a day to produce energy, and our body temperature would rise to 725 °F! Also, our hearts would have to beat 1,260 times per minute. Although nectar from flowers is the main fuel source driving the bird’s metabolic engines, it also occasionally eats insects, for protein needs.

During any given 30-minute period, hummingbirds burn the sugar they had taken in an hour ago. If we apply this rapid intake of sugar and the metabolic cycle in human beings, we would have to drink a large bottle of soda and burn the sugar in it every minute.

Unlike us, hummingbirds use both glucose and fructose from nectar in their intestines, circulatory systems, and muscle cells. However, we can support our bodies at urgent needs with an intake rate of 30% of glucose. Half of the nectar that hummingbirds take is glucose and half is fructose. In this modern age, high fructose derived from corn in our diets has paved the way for metabolic diseases and obesity – that is, people cannot metabolize high fructose.

Scientists are trying to determine how hummingbirds can process fructose. It is known that there is a carrier molecule different from glucose in fructose. This carrier is very rare in human muscle cells, but it is found in abundance in hummingbird’s muscle fibers; so we believe the mystery of how they utilize fructose so fast is about to be solved.

Hummingbirds have been equipped with mechanisms to increase the rapid introduction of nutrients such as fructose and glucose – which are basically small sugar molecules – or amino acids into their metabolisms. Their hearts and blood vessels work at a high speed to carry the sugar into their tissues as well as to transfer a lot of blood. In addition, a large number of capillaries have been implemented close to the muscle cells so that the blood can reach each and every cell.

Wing design

While humanity has not yet invented a machine that can move in a figure-8 pattern 80 times per second, including forward and backward, the ultra-flexibility of a hummingbird’s unique wing strokes demonstrates the special creation of its bones, muscles, and joints. The colibri’s brain and nervous system, which control these muscles and joints by transmitting signals, require infinite knowledge and power. The flexibility of the shoulder joint in the movement of the wings, which allows them to bend to extreme positions not found in other birds, gives us an idea of the wing’s unique design and architecture. Although biomimetic engineers have spent millions of dollars applying this complex system to technology, they have so far failed in their attempts to produce a similar machine.

Cooling the feathers due to the friction of the muscles and the tremendous movement of the wings is a problem in itself. While man-made machines need advanced cooling systems, the hummingbird has been created with a such a built-in system.

Unique tongue structure

Biologists from the University of Connecticut have discovered that hummingbirds’ tongues have a very special design and work like micro pumps. Tongues about twice the length of their beaks allow them to reach deep into flowers. The nectar is then pumped into the body in less than 1/20th of a second. This occurs thousands of times each day. Tai-Hsi Fan and Margaret A. Rubega, who for a long time examined how hummingbirds stick their tongues 15 or 20 times a second into the tubular part of a flower, said that they “could not clearly understand how they drink the nectar.” In their latest study, they showed that it was only possible for the birds to hold nectar through two channels in their tongues. It was once thought that the physical rule of the upward movement of liquids in capillary tubes, even without suction, worked in the hummingbird’s nectar intake; but when special video recordings of the movement of their tongues were examined, it became evident that the tongue first compressed the nectar in a series of movements, then sprung up very quickly and the nectar was suddenly sprayed into the channels.

It would seem that both the hummingbirds and the flowers they need for sustenance were created in perfect harmony.

Red hummingbirds migrate from Alaska to Mexico every year. They can fly 56 miles per hour. Prior to this journey, they feed for one or two weeks to fill their fuel tanks, forming a layer of fat equal to half their body weight. Since these activities cause a lot of heat loss on the body surfaces, they cannot provide enough energy to stay active for more than 12 hours at a time. To counter this, they fall into a deep sleep every night for 12 hours. The energy storage, flight endurance, long-distance migration, and returning with the young ones are each complicated factors that their coming together to make this journey possible cannot simply be explained by blind chance.

Of course, the smallest bird in the world would have the smallest egg size: a mere 0.5 x 0.3 inches, for a total weight of 0.007 ounces. Considering that this wonderful bird’s design is embedded into this egg, which is about the size of the nail of our little finger, it can be understood how perfect a creation it is.

#allah#god#prophet#muhammad#quran#ayat#islam#muslim#muslimah#hijab#help#hadith#sunnah#revert#convert#religion#reminder#dua#salah#pray#prayer#welcome to islam#how to convert to islam#new muslim#new revert#new convert#revert help#convert help#islam help#muslim help

1 note

·

View note