#Classic period MesoAmerica

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

- Sol De MesoAmerica

Did a slight retouch on Tonatiuh! I’ll try to do more content with him!

Background ☀️

#aph#hws#ヘタリア#hetalia#aph mexico#hws mexico#hws teotihuacan#aph teotihuacan#teotihuacan#mesoamerica#Classic period MesoAmerica#hetalia oc

217 notes

·

View notes

Text

c. 1540 CE: a young man from Chalco, and his dragon.

#em draws stuff#em is posting about temeraire#temeraire#temeraire worldbuilding collection#⚬⚬⚬⚬⚬𐂂#<- tag for organizing when I'm drawing stuff that is temeraireVerse but not in the line of the plot of the books themselves#for school reasons I have been reading a lot about 14th-17th century mesoamerica#and thus am Interested in how that would have potentially played out in temeraireverse...#anyway! not sure if I'll draw these two again but I Have given the lad a day sign name (five deer) so I could Potentially. who can say.#haven't come up with a name for the dragon yet... maybe cipachcoatzin would work if can't think of anything else#<- Please Forgive My Dubious Command of Classical Nahuatl Grammar I Am But A Student#on that note zoomorphic interlace is not very much a style from this period/region but it helps me with composition things#five deer himself is mostly based on the illustration of the tlacuilo's son in the codex mendoza#the dragon is drawn more from a fusion of older scribal styles (ie. the codex borgia) and my own shorthands for dragon anatomy

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

~ Brazier in the Form of the Old God.

Place of origin: Teotihuacan, Mexico

Period: Early Classic period (250 B.C.–A.D. 600)

Date: ca. A.D. 400–500

Medium: Basalt

#ancient#ancient art#history#museum#archeology#ancient sculpture#ancient history#5th century#6th century#Teotihuacan#mexico#mesoamerica#early classic period#basalt#a.d. 400#a.d. 500

617 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maya, Early Classic 300-400 CE 10.16 cm x 5.72 cm x 0.64 cm (4 in. x 2 1/4 in. x 1/4 in.) jadeite

A pendant that may have been worn as part of a Maya ruler’s belt assemblage, this jadeite belt plaque offers intriguing clues to the process of reworking objects for different purposes. In its original form, the piece was lightly incised with two hieroglyphs, which were carefully framed by a double cartouche. A hole for suspending the plaque slightly overlaps the outer cartouche, as if placed with no regard for the incised line. The line of the cartouche has also been ground away along the bottom of the plaque, which now shows a slightly beveled edge.

At some point in its history, the plaque was deliberately reshaped with grinding and cutting tools into a figural form. The object was inverted so that the ground “eyes” of the figure are located in the middle of the lower hieroglyph. The cut marks on each side and from the edge of the plaque to the suspension hole imply limbs, and these alterations may indicate that the object was recarved in the shape of an axe god, an ancient Costa Rican form. The cut that defines the legs does not extend all the way to the suspension hole, although cut marks are visible on either side of it.

A remarkable object in terms of its material and inscription, the Dumbarton Oaks plaque is particularly interesting in the context of changes in its meaning and function, evidenced in its modifications. These changes are especially intriguing because this work may have belonged to a set of six inscribed belt plaques. Three plaques, possibly from this set, were discovered in the Early Classic tomb at Calakmul. Together, glylphs on the six plaques would have formed a text—whose meaning was lost once the plaques went their separate ways. As this objetc was modified and reworked, its initial textual significance was apparently replaced by other narratives and symbolism related to its value as a precious gift and heirloom.

Belt Plaque

Maya, Early Classic, 300-400 CE

#history#clothing#jewellery#art#carving#languages#classic period#mesoamerica#maya#mexico#costa rica#campeche#calakmul#belts#jade#jadeite#maya hieroglyphs

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Ball Game of Mesoamerica

The sport known simply as the Ball Game was played by all the major Mesoamerican civilizations and the impressive stone courts became a feature of many cities. More than just a game, it could have a religious significance and featured in episodes of mythology. Contests even supplied candidates for human sacrifice and became literally a game of life or death.

Origins

The game was invented sometime in the Preclassical Period (2500-100 BCE), probably by the Olmec, and became a common Mesoamerican-wide feature of the urban landscape by the Classical Period (300-900 CE). Eventually, the game was even exported to other cultures in North America and the Caribbean.

In Mesoamerican mythology the game is an important element in the story of the Maya gods Hun Hunahpú and Vucub Hunahpú. The pair annoyed the gods of the underworld with their noisy playing and the two brothers were tricked into descending into Xibalba (the underworld) where they were challenged to a ball game. Losing the game, Hun Hunahpús had his head cut off; a foretaste of what would become common practice for players unfortunate enough to lose a game.

In another legend, a famous ball game was held at the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan between the Aztec king Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin (r. 1502-1520 CE) and the king of Texcoco. The latter had predicted that Motecuhzoma's kingdom would fall and the game was set-up to establish the truth of this bold prediction. Motecuhzoma lost the game and did, of course, lose his kingdom at the hands of the invaders from the Old World. The story also supports the idea that the ball game was sometimes used for the purposes of divination.

Continue reading...

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

Below are 10 featured Wikipedia articles. Links and descriptions are below the cut.

The election in 1860 for the position of Boden Professor of Sanskrit at the University of Oxford was a competition between two candidates offering different approaches to Sanskrit scholarship. One was Monier Williams, an Oxford-educated Englishman who had spent 14 years teaching Sanskrit to those preparing to work in British India for the East India Company. The other, Max Müller, was a German-born lecturer at Oxford specialising in comparative philology, the science of language.

Adolfo Farsari (Italian pronunciation: [aˈdolfo farˈsaːri]; 11 February 1841 – 7 February 1898) was an Italian photographer based in Yokohama, Japan. His studio, the last notable foreign-owned studio in Japan, was one of the country's largest and most prolific commercial photographic firms. Largely due to Farsari's exacting technical standards and his entrepreneurial abilities, it had a significant influence on the development of photography in Japan.

Girl Pat was a small fishing trawler, based at the Lincolnshire port of Grimsby, that in 1936 was the subject of a media sensation when its captain took it on an unauthorised transatlantic voyage. The escapade ended in Georgetown, British Guiana, with the arrest of the captain, George "Dod" Orsborne, and his brother. The pair were later imprisoned for the theft of the vessel.

Abu Muhammad Hasan al-Kharrat (Arabic: حسن الخراط Ḥassan al-Kharrāṭ; 1861 – 25 December 1925) was one of the principal Syrian rebel commanders of the Great Syrian Revolt against the French Mandate. His main area of operations was in Damascus and its Ghouta countryside. He was killed in the struggle and is considered a hero by Syrians.

Marjorie Cameron Parsons Kimmel (April 23, 1922 – July 24, 1995), who professionally used the mononym Cameron, was an American artist, poet, actress and occultist. A follower of Thelema, the new religious movement established by the English occultist Aleister Crowley, she was married to rocket pioneer and fellow Thelemite Jack Parsons.

Maya stelae (singular stela) are monuments that were fashioned by the Maya civilization of ancient Mesoamerica. They consist of tall, sculpted stone shafts and are often associated with low circular stones referred to as altars, although their actual function is uncertain. Many stelae were sculpted in low relief, although plain monuments are found throughout the Maya region. The sculpting of these monuments spread throughout the Maya area during the Classic Period (250–900 AD), and these pairings of sculpted stelae and circular altars are considered a hallmark of Classic Maya civilization.

The North Norfolk Coast Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) is an area of European importance for wildlife in Norfolk, England. It comprises 7,700 ha (19,027 acres) of the county's north coast from just west of Holme-next-the-Sea to Kelling, and is additionally protected through Natura 2000, Special Protection Area (SPA) listings; it is also part of the Norfolk Coast Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). The North Norfolk Coast is also designated as a wetland of international importance on the Ramsar list and most of it is a Biosphere Reserve.

Preening is a maintenance behaviour found in birds that involves the use of the beak to position feathers, interlock feather barbules that have become separated, clean plumage, and keep ectoparasites in check. Feathers contribute significantly to a bird's insulation, waterproofing and aerodynamic flight, and so are vital to its survival. Because of this, birds spend considerable time each day maintaining their feathers, primarily through preening.

The Wells and Wellington affair was a dispute about the publication of three papers in the Australian Journal of Herpetology in 1983 and 1985. The periodical was established in 1981 as a peer-reviewed scientific journal focusing on the study of amphibians and reptiles (herpetology). Its first two issues were published under the editorship of Richard W. Wells, a first-year biology student at Australia's University of New England. Wells then ceased communicating with the journal's editorial board for two years before suddenly publishing three papers without peer review in the journal in 1983 and 1985. Coauthored by himself and high school teacher Cliff Ross Wellington, the papers reorganized the taxonomy of all of Australia's and New Zealand's amphibians and reptiles and proposed over 700 changes to the binomial nomenclature of the region's herpetofauna.

Wulfhere or Wulfar (died 675) was King of Mercia from 658 until 675 AD. He was the first Christian king of all of Mercia, though it is not known when or how he converted from Anglo-Saxon paganism. His accession marked the end of Oswiu of Northumbria's overlordship of southern England, and Wulfhere extended his influence over much of that region.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day Ozomahtli (Monkey), known as Chuen in Maya is governed by Xochipili, the Flower Prince, as its provider of tonalli (Shadow Soul) life energy. Ozomahtli is a day for creating, for play, for celebrating. Xochipili Talon Abraxas

Xochipilli or the 'Prince of Flowers' was the Mesoamerican god of summer, flowers, pleasure, love, dancing, painting, feasting, creativity and souls. He is a benevolent manifestation of Piltzintecuhtli, the young sun god who was himself a manifestation of Tonatiuh, the supreme sun god of Mesoamerica. The god is closely associated with the corn (maize) god Centéotl and was sometimes referred to as the 'Corn-flower Prince' or Centéotl-Xochipilli, the 7th Lord of the Day. For the Aztecs he could also appear as Ahuiatéotl, the god of voluptuousness and he was also associated with butterflies, poetry and the 11th of the 20 Aztec days: Ozomatli (Monkey). He was considered one of the Ahuiateteo, the gods of excess, and for the Zapotec he was Quiabelagayo. Generally speaking, though, he was thought of as something of a youthful and care-free pleasure-seeker, perhaps with a playfully mischievous streak.

Xochipilli may have origins in the earlier Mesoamerican god worshipped at Teotihuacán during the Pre-Classic to Classic Period who is known simply as the Fat God. In Aztec mythology Xochipilli has two brothers Ixtlilton (the god of health, medicine and dancing) and Macuilxóchitl (the god of games). As a group this good-time trio represented health, pleasure and happiness. The god also has a sister (or female counterpart), Xochiquetzal.

Particularly worshipped at Xochimilco, the most common offering to the god was corn and during his festivals, which were held in the early growing season and during Tecuilhuitontli (the 8th Aztec month), pulque (the alcoholic beverage made from the maguey or agave plant) was copiously drunk. Statues of the god were also frequently decked out with flowers and even butterflies.

Perhaps the most famous representation of the god in art is the Late Post-Classical Period (1450-1500 CE) statue, a masterpiece of Aztec sculpture, now residing in the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. The statue is 1.2 metres high and has Xochipilli seated on a temple platform (or perhaps a drum) which is decorated with butterflies, flowers and clusters of four dots representing the sun. Xochipilli is wearing a mask and is himself covered in flowers from psychotropic plants, hallucinogenic mushrooms and animal skins. Cross-legged and care-free the god is portrayed happily singing and playing his rattles, a vibrant symbol of all the good things in life.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kukulkan (Quetzalcoatl): Feathered Serpent And Mighty Snake God

Known under a number of different names, Kukulkan, the Feathered Serpent was one of the most important gods in Mesoamerica.

The Aztecs called him Quetzalcoatl and the ancient Maya referred to him as Kukulkan. The K’iche’ group of Maya named him Gukumatz.

Was this mighty snake deity a real historical person?

It is not easy to trace the ancient history of Kukulkan. Like all of the feathered serpent gods in Mesoamerican cultures, Kukulkan is thought to have originated in Olmec mythology and we still know very little about the mysterious Olmec civilization.

The true identity of the god Kukulkan becomes an even greater problem due to the confusing references to a man who bore the name of the Mayan god. Because of this, the distinction between the two has become blurred.

Around the 10th century, a priest or ruler appeared in Chichen Itza, a sacred site that was one of the greatest Mayan centers of the Yucatán peninsula, Mexico where we also find El Castillo, also known as the Temple of Kukulkan.

Kukulkan has his origins among the Maya of the Classic Period, (200 AD to 1000) when he was known as Waxaklahun Ubah Kan, the War Serpent.

Maya writers of the 16th century describe Kukulkan as a real historical person, but the earlier 9th-century texts at Chichen Itza never identified him as human and artistic representations depicted him as a Vision Serpent entwined around the figures of nobles.

According to ancient Maya beliefs, Kukulkan - popularly known as the Feathered Serpent - was the god of the wind, sky, and the Sun. He was a supreme leader of the gods, depicted, just like Quetzalcoatl. Kukulkan gave mankind his learning and laws. He was merciful and kind, but he could also change his nature and inflict great punishment and suffering on humans.

According to Maya legend, the Maya were visited by a robed Caucasian man with blond hair, blue eyes, and a beard who taught the Maya about agriculture, medicine, mathematics, and astronomy. This being was Kukulkan – the Feathered Serpent.

Kukulcan warned the Maya of another bearded white man who would not only conquer the indigenous people of Central America but would also enforce a new religion upon them before he was to return. Despite the warning, the Maya mistakenly welcomed the invading Cortes as Quetzalcoatl.

The cult of Kukulkan spread as far as the Guatemalan Highlands, where Postclassic feathered serpent sculptures are found with open mouths from which protrude the heads of human warriors.

Hundreds of North and South American Indian and South Pacific legends tell of a white-skinned, bearded lord who traveled among the many tribes to bring peace about 2,000 years ago. This spiritual hero was best known as Quetzalcoatl.

Some of his many other names were:

Kate-Zahl (Toltec)

Kul-kul-kan (Maya)

Tah-co-mah (NW America)

Waicomak (Dakota)

Wakea (Cheyenne, Hawaiian and Polynesian)

Waikano (Orinoco)

Hurakan

the Mighty Mexico

E-See-Co-Wah (Lord of Wind and Water)

Chee-Zoos

the Dawn God (Puan, Mississippi)

Hea-Wah-Sah (Seneca),

Taiowa, Ahunt Azoma

E-See-Cotl (New Guinea)

Itza-Matul (Yucatan)

Zac-Mutul (Mayan)

Wakon-Tah (Navajo)

Wakona (Algonquin)

Kukulkan emerged from the ocean, and disappeared in it afterward. Before he left, he promised that he will return one day in the future, but he never revealed when…

Image: Kukulkan (Quetzalcoatl) Mahaboka

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Maya ball court, Coba, Quintana Roo, México. Major building construction seems to have occurred in Coba during the middle and late Classic period (500-900). Photo by Dennis Jarvis. "The Native American ball game was played with a rubber ball on a masonry court, and was widely known in Central America and Mesoamerica. Its range extended over an area of 2,500,000 square kilometers, from the U.S. Southwest into the Amazon region of South America. It was played for at least 2,000 years prior to European contact. The object of the game, as indicated by archaeological and ethnohistoric evidence, was to score a goal by propelling the ball into the ground of the opposing team’s end of the court, or through a ring or other marker along the side of the court. As in modern soccer, players could not use their hands to propel the ball, and the game in play may have resembled soccer, with considerable action." From "Archaeology of Ancient Mexico and Central America: An Encyclopedia." https://www.instagram.com/p/CpdXGlhNHLt/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

168 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mayan Mythology: Deities, Cosmology and Cultural Legacy

Mayan mythology is one of the richest and most intriguing traditions of pre-Columbian cultures, full of myths, legends and stories that explain the origin of the world, the nature of the gods and the relationship between humans and the cosmos. The Mayans, who inhabited the region of Mesoamerica (present-day Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador and Belize), developed a complex civilization marked by a deep understanding of astronomy, mathematics and religion. Mayan mythology, as a central part of the culture, is directly linked to these aspects and is expressed in texts, rituals, art and architecture.

Mayan Cosmology The Mayan worldview is structured in three main layers: the sky, the earth and the underworld, also known as Xibalba.

Heaven: This is the realm of the gods and deified ancestors. The sky is divided into several layers, and each of them is governed by different gods. The most important sky god is Itzamná, who is also the lord of wisdom and creation.

The Earth: This is the place where humans live and interact with the gods through rituals and sacrifices. For the Mayans, time on Earth is cyclical, meaning that cosmic and historical events repeat themselves in predictable cycles. The concept of cyclical time is fundamental to understanding the famous Mayan Calendar, which is based on complex astronomical calculations and rituals.

Xibalba: The Mayan underworld, ruled by gods of death and disease, is described as a place of suffering and darkness. However, it is also seen as a necessary stage on the spiritual journey. The myth of the Popol Vuh, one of the best-known stories in Mayan mythology, describes the twin heroes who descend to Xibalba, confront the lords of death and return triumphant, symbolizing the overcoming of death and rebirth.

2. Main Gods of Mayan Mythology The Mayans worshipped a large number of gods, each associated with specific aspects of life, nature and the cosmos. Many of these gods were personifications of natural forces, such as the sun, rain and vegetation. The main Mayan gods include:

Itzamná: The supreme god of creation, lord of the sky and wisdom. He was also associated with writing and knowledge, and was considered the patron saint of priests.

Kukulcán: Represented as a feathered serpent, Kukulcán is a highly venerated deity and is often compared to Quetzalcóatl of the Aztecs. He symbolizes the union of heaven and earth and was one of the main gods of the Mayan pantheon, especially in the post-classic period.

Chaac: The god of rain and thunder. Chaac was extremely important to the Mayans, as agriculture depended on rainfall, and therefore rituals were performed in his honor to ensure good harvests. Chaac is depicted with an axe and large tusks, symbolizing his power to cause storms.

Hun Hunahpú: One of the twin heroes of the Popol Vuh, who is killed in the underworld but is reborn as the god of corn. His story symbolizes the renewal of life and the cycle of crops, a central theme in Mayan mythology and culture.

Ix Chel: The goddess of the moon, childbirth, and medicine. Ix Chel is also associated with water, especially floods and fertility, and is an important figure for Mayan women. She often appears alongside Chaac, reinforcing the connection between rain and the fertility of the earth.

The Popol Vuh: The Sacred Book of the Mayans One of the most important sources for understanding Mayan mythology is the Popol Vuh, a sacred text that narrates the creation of the world, the story of the twin heroes, and the origins of the Mayan people. Written by the Quiché, one of the largest Mayan ethnic groups, the Popol Vuh was preserved during the Spanish colonization and contains a rich compendium of myths.

The Creation of the World: In the Popol Vuh, the gods create the world in several attempts, using different materials to form human beings. Only in the last attempt, when using corn to mold the first men, do they manage to create perfect humans, who begin to inhabit the Earth and worship the gods.

The Hero Twins: Hunahpú and Ixbalanqué, the hero twins, are central figures in the Popol Vuh. They challenge the lords of Xibalba in a series of trials, eventually triumphing and ascending to heaven. Their story is a metaphor for the victory of life over death and is deeply connected to agricultural cycles and the renewal of nature.

Ritual and Religion Rituals were a fundamental part of Mayan religious life. Many of the myths and sacred stories were intertwined with practices of sacrifice, divination, and offerings. Priests played a crucial role in interpreting the signs of the gods and conducting rituals to ensure harmony between the cosmos and humanity.

Sacrifices: The Mayans performed sacrifices, both of animals and humans, to appease the gods, especially in times of crisis, such as during droughts or battles. Blood was seen as a sacred offering, necessary to maintain the balance of the world.

Ball Games: The Mayan ball game (Pok-ta-Pok) was a ritualistic ceremony that also had deep roots in mythology. The game represented the battle between the Hero Twins and the lords of the underworld, and often had a symbolic outcome involving human sacrifice.

Legacy and Influence of Mayan Mythology Mayan mythology continues to have a profound impact on the indigenous cultures of Central America. Even after the Spanish conquest, many of the Mayan myths and traditions survived, being incorporated or reinterpreted within the context of Catholicism. Today, the descendants of the Mayans still maintain cultural and religious practices that reflect this rich mythological heritage.

In addition, Mayan cosmology and the Mayan calendar continue to fascinate scholars and enthusiasts around the world. The supposed “end of the world” predicted for 2012 was based on a misinterpretation of the Mayan calendar, which rekindled global interest in this ancient civilization.

Conclusion Mayan mythology is a reflection of the cultural and spiritual complexity of one of the most advanced peoples of Mesoamerica. Their myths not only explained the origin of the world and human beings, but also served as the basis for their religious practices, their view of time and the cosmos. Even today, Mayan mythology continues to be a source of fascination and study, connecting the present with a deeply spiritual and symbolic past.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mesoamerica

The precolonization time periods of Mesoamerica, which covers modern-day Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador and parts of Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica are divided into different periods than those in Europe and the Middle East. Part of this is simple separation, though other reasons include geography (that Mesoamerica has oceans on both sides and between two much larger north-south oriented land masses as well as the minerals available) and climate (a complex mixture of lowlands, highlands, and sub-tropical and tropical climates in the lowlands to cool and dry in the highlands).

Humans reached the area approximately 18000 BCE. From then until about 8000 BCE is known as the Paleo-Indian or, less commonly, the Lithic period, followed by the Archaic period which ended about 2000 BCE, followed by the Preclassical until about 250 CE, the Classical until 900 CE, then the Postclassical, which ended with the Spanish colonization around 1500 CE.

The Paleo-Indian era covers the time period from when people arrived in the area and began using agriculture, pottery, and other skills needed to maintain life. This time period covered hunter-gatherer civilizations and the development of field-based agriculture. This period is fairly similar to the Stone Age in Europe and the Middle East.

During the Archaic period, permanent settlements were established, followed by pottery and loom weaving, allowing class divisions to begin to appear. Trade networks also developed, within short distances at first, then further afield, for stones like obsidian and chert (a fine grained sedimentary rock formed of microcrystaline quartz).

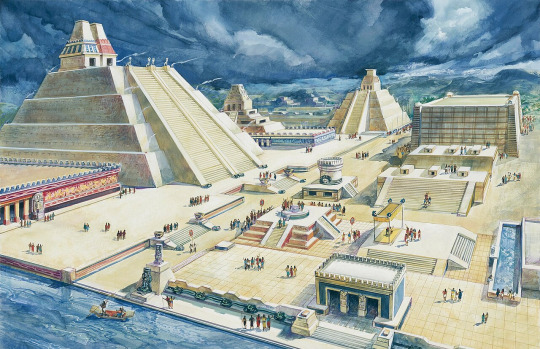

By Gary Todd - https://www.flickr.com/photos/101561334@N08/9764925512/, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=96186719

During the Preclassical period, large-scale ceremonial architecture, cities, states, and writing developed. With the development of writing, we can know what the groups of people called themselves. Some of these are the Olmec, who lived around La Venta and San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán, the Zapotec civilization, around the Valley of Oaxaca, Teotihuacan, in the Valley of Mexico, and the Maya, in the Mirador Basin.

By amslerPIX - https://www.flickr.com/photos/amslerpix/48762494738/, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=113266497

The Classical period was defined by the independent city-states of the Maya and the beginnings of political unification of central Mexico and the Yucatán. Differences in regional cultures manifested themselves until the city-state of Teotihuacan began to dominating the Valley of Mexico, though we don't know much about the culture of the area due to Teotihuacanos not having a culture of writing. The city-state of Monte Albán dominated the Valley of Oaxaca. Though we have some of their writing, we haven't been able to decipher it yet. They did leave a highly sophisticated artistic culture as well, which spread through the area.

By Attributed to Diego Rivera - TheSun.co.uk - https://www.thesun.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/NINTCHDBPICT000416684675.jpg, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=145523789

The Postclassical period saw the collapse of many of the great nations of the Classical period, though the Oaxaca, the Maya of Yucatan (such as the city of Chichen Itza and Uxmal), and the Cholula continued. This period is thought to have seen an increase in warfare, though there were technological advancements in engineering, weaponry, and metallurgy occurred. There was also a lot more movement and population growth during this time as well, especially after about 1200 CE, and experiments in government. The Toltec dominated in the 9-10th centuries then collapsed. The Maya united for a while under Mayapan and the Oaxaca under Mixtec rulers. The Aztec Empire rose in the 15th century and began conquering the Valley of Mexico. This was also the beginning of a renaissance of fine arts and sciences.

By Karnhack - karnhack.com, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24111651

The Spanish conquest of the area was aided by native people who wanted allies against the Aztec Empire. After this, much of the culture of the area and many of the people were destroyed by the Spaniards.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

🎶Amor prohibido murmuran por las calles🎶

#ヘタリア world stars#aph oc#hetalia oc#hws toltec#hws uxmal#hws chichen itza#hws mayapan#mesoamerica#Classic period MesoAmerica#I have a little joke that ms Uxmal here had a little crush on mr Toltec#this is a joke because Uxmal was the only city state out of the league of Mayapan not to be directly influenced by the toltecs#hence the caption choice#Toltec is dense and never noticed her crush#hws mexico

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

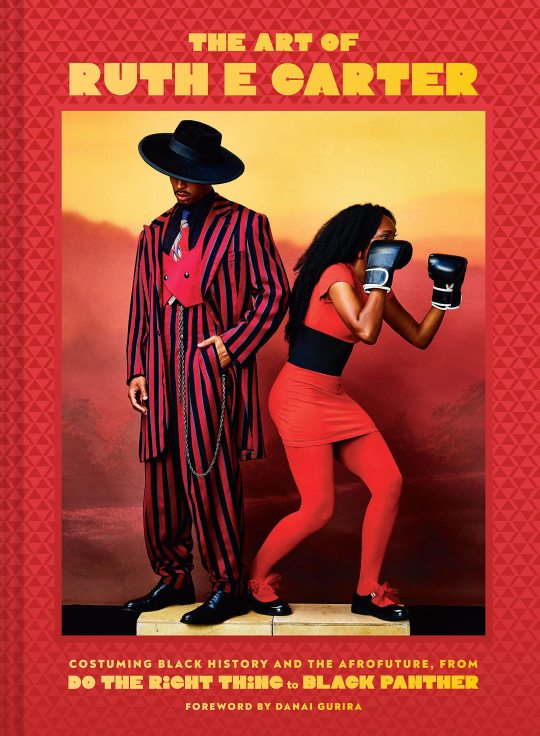

Monday MCU

ART OF RUTH E. CARTER

Brand new and just out now! A monograph of Ruth E. Carter's costuming work, including chapters on Wakanda Forever with pictures and sketches, including this one of Namora's dress.

From the Marvel.com article, an excerpt from the book.

ON THE DESIGN OF THE TALOKAN IN “WAKANDA FOREVER”:

"The most challenging costumes were built for the Talokanil. I immersed myself in studying Maya culture. Not only were the Maya colonized, but also the research about them contained many misrepresentations, and sometimes they were erased from the history books all together. It was imperative that we work closely with our historian to check our work and learn about a civilization that contributed to the culture of Mesoamerica as we know it today. Through resources like the Dresden Codex and the Maya Vase Database, we learned that the Maya wore ceremonial garments and that there were leaders and families whom you could identify through their dress and adornment.

We learned that Maya traditional costumes included sheer fabrics, prints, jewelry, adornments, wraps of all types, and headpieces. There were specific elements we used to stay authentic to the culture, one of which was the ear spool. The ear spool, or flare, was made of jade and at times mimicked a flower. Worn on the ear, it was considered a pathway to the gods, and there’s hardly a Maya painting or sculpture without this detail. Using ear flares throughout the Talokanil’s costumes helped achieve the right look.

We also printed our own sheer fabrics using images seen on Maya vases, painted by different artists and depicting many true-to-life scenarios of the post-classic Mesoamerican period. The vases were so incredible; using imagery from them was a way to have Maya history present in the costumes, even if, once the fabric was made into a garment, the effect was more abstract. The colors and patterns created a beautiful palette.

Then I was inspired by the Jaina figurines—a set of clay sculptures excavated on a pre-Columbian archeological dig on an island off the Yucatán Peninsula. We studied the adornments on these figurines, and they presented a plethora of ideas for clothing, jewelry, and headpieces. The sculptures were a significant help in creating the look for an underwater society that lived parallel to their relatives on land.

I needed to blend the rich culture of the Maya with the fact that the Talokanil were an underwater civilization, thousands of years old. This created an additional layer of difficulty. Ancient Maya costumes were made of natural fibers, jade, shells, and clay. These elements needed to be mimicked and made of materials that could withstand being submerged in water for hours. As we had seen with M’Baku’s costume, costumes underwater can be beautiful, but understanding the dynamics of buoyancy and color refraction is necessary when designing them. Fabrics float up. Weights are sometimes required to achieve a desired effect. Chlorinated water and salt water both wreak havoc on fabric dyes.

Namor, brought to life by the wonderful Tenoch Huerta, was to wear a ceremonial headpiece and shoulder piece designed to reference the feathered serpent, a Maya deity that is seen repeatedly wrapping the bodies of nobles in Maya art. The serpent symbolizes life above and below the earth and is associated with the underworld. Namor’s neck ring also contains two feathered serpents that meet at the center front, greeting a large pearl with open mouths. The pearl represents the ocean. The neck-ring design was inspired by the pyramid at Chichén Itza (also called Kukulkan), which has a staircase with two feathered serpents descending on each side; at the base the two heads face a cenote. We modeled the headpiece first in clay. The feathers were made to resemble kelp and fish fins. The serpent was cast and painted gold with elements inspired by blue and green jade and mother-of-pearl. The blue stone in the headpiece was to represent Talokan’s vibranium."

#Namor#Sub-Mariner#Namora#MCU Namor#MCU Namora#Wakanda Forever#Book#Merchandise#Monday#Monday MCU#Behind the Scenes#Costume#Ruth E. Carter#MCU

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Mezcala sculptural style of Guerrero emphasizes geometric abstraction in both human figures and architectural models. Few examples have been found in their original context, and thus the function, meaning, and even the length of time during which the style was in use remain ill defined. Contributing to the question of chronology is the fact that other Mesoamerican peoples, from the latter centuries of the Late Formative to the Late Postclassic periods (200-1500 CE), acquired and preserved these works as heirlooms. They have been found at sites throughout Mexico, and large numbers were excavated from ritual caches in the Templo Mayor, the main temple of the fifteenth-century Mexica (Aztecs) of Tenochtitlan (Mexico City). In the twentieth century, the minimalistic Mezcala artworks fascinated the Mexican artist and cultural historian Miguel Covarrubias, who compared them favorably to other sculptural traditions such as the celebrated Cycladic style of ancient Greece. This example features the typical Mezcala four-columned structure atop a pyramidal platform articulated by apron-moldings on the uppermost tier. A central staircase leads into the structure at the midpoint between the columns. A lone figure stands between the columns and inside the structure. No buildings of this type have survived in Guerrero, however, which leaves open the question of whether this carving faithfully represents the architectural traditions of the region during the Formative and Classic periods.

~ Temple Model.

Culture: Mezcala

Date: 300 B.C.-A.D. 500 (?)

Period: Terminal Formative-Early Classic

Medium: Stone

#history#sculpture#art#art history#architecture#preclassic era#classic period#postclassic period#mesoamerica#mezcala culture#aztec empire#tenochtitlan#mexico#guerrero#mexico city#templo mayor#miguel covarrubias

220 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient and distant dragons (part II)

Last time we saw what the Chinese, Sumerian and Slavic civilizations understood by ''dragon'', along with other groups related to those. So, let's see other examples of this idea, close coincidences and divergences!

I would talk in depth about the European dragon itself. However, and oddly enough, such mythical being is not entirely original, like the examples we're trying to gather, more like a very baroque conglomerate of influences that eventually came to be the winged lizard we all know. So let's talk, instead, about the roots behind it.

However, it's inspirations are quite curious. The European or Conventional Dragon, is a mixture of two different ''dragonlike beings'', both unaware of each other, as far as we know!

The first influence is, surprisingly the Sumerian Mušḫuššu we previously looked at. Told you that the idea of an animal with reptilian traits would stick around!

Second one is more obscure. It is believed the Dacian Drakon could be a major player. This creature has a very confusing genealogy, being on it's own the result of a lot of artistic depictions of beasts, streetching as far as the 8th century BCE, and for over a thousand years it suffered a great amount of changes, being consistently depicted as a mixture of a snake and another, different animal.

By the time the Roman Empire assimilated the Dacians (located where modern Romania is) at 2th c. AD and incorporated the creature into their own mythos, it was mostly a wolf headed, thick snake. It was quite important for the native Dacians, represented as a protecting spirit in both millitary vexilloids and wind instruments such as horns.

A ferocious Dacian Drako, engraved in the Roman Tracian column.

Those two creatures (Drakon and Mušḫuššu) loosely permeated, along with other influences such as local, folklore beasts of many sorts, and depictions of snakes as the root of evil (a consistent avatar of the Christian Devil, as soon as in the Genesis book of the Bible, but in many other occasions, such as Isaiah book [14:29]).

All those influences, after centuries of obscurity, were gradually sewn together during the Middle Ages (remember, most classical knowledge and folklore was reduced to residual traces during this historial period) into the big, bad dragon that the forces of good must defeat.

A winged snake, a somewhat popular heraldic symbol (this one in particular is from 17th century, though). A possible additional influence in this dense melting pot?

The slavic dragons we saw in the previous post most likely were a direct influence of this trend, one of the many types created by mixing chimeras and local beasts alike.

What we can safely say, is that the european dragons are a byproduct of many ideas of different ages and places colliding together. We all influence each other through the time!

Of course, there were many differing interpretations under the umbrella of dragonhood, here's a french one that incorporates particular body proportions, and devilish goat horns (from the 1410 manuscript The Crucifixion by a follower of Egerton Master). What an awe inspiring fiend!

But let's put the european ones aside, and take another loooong leap. How about... you guessed it...

Mesoamerica!

Mayas, Toltecs, and others do have, too, a remote tradition of dragonlike monsters who weren't mere beasts, but even reached the status of godhood!

The cosmology of many different groups in upper central america has in common the reverence of a being called ''the feathered snake'', adored since XV century BCE, and until the arrival of the Castillian crown, some 3000 years later. Wow!

The first peoples that depicted such a being were the Olmecs, considered as one of the first greater cultural identities in the Americas. Here's the first known feathered snake, in La Venta settlement:

A feather crested, giant snake with a man (who wears a fanged helmet), considered by some as his alter-ego. The bag the man holds appears to represent a ritual of sorts, and his earpiece implies high ranking status.

The Olmecs left, as we said, a long lasting legacy that affected cultures far away from their territories.

The serpent would later be adopted into the maya God Kꞌuꞌukꞌul Kaan (lit. Feathered Snake), represented in many royal steels (as we saw here) as the being that allows an ajaw (lord) to see his ancestors, and win their favor to be crowned. In the case of the Toltecs, it was named Quetzacoatl (both names sound vaguely similar)

A feathered serpent, found among the ruins of the maya Poqomam kingdom, with a human head pecking out, as per usual with maya iconography.

The Toltec, and later on Aztec Quetzacoatl, God of light, life, civilization and knowledge. Notice how this version was more birdlike, totally covered by feathers, but also with a mouth whose jaw contracted into a spiral, almost resembling a pair of twirled whiskers (not intended, but still curious).

That's some long lasting impression, to say the least!

In the following post, we'll see some more dragonlikes, also created fortuitously and with no connection with the rest of this really extended family. Remember that I only write small pieces of info, and usually I do skim over a lot when covering these topics, so if you want to know more, I encourage you to keep researching on ANYTHING that has caught your attention. (Or, well, ask me for an indepth post apart, which I would gladly investigate and redact).

Until next time!

#culture#anthropology#maya#mayan culture#aztec#aztec culture#aztec mythology#aztec gods#mexica#civilization#art#ancient history#mesoamerica#dragons#dragon#european dragon#religious art#history#folklore#mythology#mythical creatures#so much in common yet so much diferent

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Discovering Mexico: A Journey Through History, Attractions, and Seasons

Mexico’s history is as diverse and vibrant as the culture and people that define it. The story of Mexico begins with the ancient civilizations that flourished long before the arrival of Europeans. The Olmecs, often considered the mother culture of Mesoamerica, set the stage around 1200 BCE with their colossal head sculptures and advanced societal organization.

Following the Olmecs, the Maya civilization reached its peak during the Classic period (250-900 CE). Known for their impressive pyramids, sophisticated calendar, and written script, the Maya left a lasting legacy, particularly in the Yucatán Peninsula. Simultaneously, the Zapotec and Mixtec cultures thrived in the Oaxaca region, building the city of Monte Albán, which became a major center of influence.

The rise of the Aztec Empire in the late Postclassic period marked a significant chapter in Mexico’s history. By the early 16th century, the Aztecs had established their capital, Tenochtitlán, on the site of present-day Mexico City. The city was a marvel of urban planning, featuring intricate canals, grand temples, and bustling markets. However, the arrival of Spanish conquistadors led by Hernán Cortés in 1519 marked the beginning of the end for the Aztec Empire.

The Spanish colonization that followed brought profound changes to the region. Mexico became the Viceroyalty of New Spain, a critical part of the Spanish Empire. The Spanish introduced Christianity, built numerous churches, and integrated European culture with indigenous traditions, resulting in a unique mestizo identity. After nearly 300 years of colonial rule, Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821.

The 19th and 20th centuries saw Mexico undergoing significant political and social transformations, including the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920), which aimed to address deep-seated inequalities and resulted in substantial land reforms and the establishment of a more democratic government structure. Today, Mexico is a vibrant democracy, known for its rich cultural heritage, economic potential, and influence on the global stage.

Must-Visit Places in Mexico

Mexico City: Mexico City, the bustling capital, offers a blend of ancient and modern attractions. The historic center, a UNESCO World Heritage site, is home to the Zócalo, one of the largest public squares in the world, and the Metropolitan Cathedral. Nearby, the National Palace houses stunning murals by Diego Rivera depicting Mexico's history. Don’t miss the Templo Mayor, an Aztec temple unearthed in the heart of the city, and the Museo Nacional de Antropología, which showcases artifacts from Mexico's diverse civilizations.

Teotihuacán: Just outside Mexico City lies Teotihuacán, one of the most significant archaeological sites in Mesoamerica. The ancient city, known as the "City of the Gods," features the towering Pyramid of the Sun and Pyramid of the Moon, connected by the Avenue of the Dead. The sheer scale and architectural precision of Teotihuacán continue to awe visitors and scholars alike.

Chichen Itza: In the Yucatán Peninsula, Chichen Itza stands as a testament to the grandeur of the Maya civilization. The site is dominated by the El Castillo pyramid, also known as the Temple of Kukulkan. During the spring and autumn equinoxes, the pyramid casts a shadow that resembles a serpent descending its steps, a phenomenon that draws crowds from around the world. Other notable structures include the Temple of the Warriors and the Great Ball Court.

Palenque: Nestled in the jungles of Chiapas, Palenque is a smaller yet equally impressive Maya site. Known for its intricate architectural details and stunning bas-reliefs, Palenque’s Temple of the Inscriptions contains one of the longest hieroglyphic texts discovered in the Americas. The site's lush surroundings add to its mystical ambiance.

Oaxaca: The city of Oaxaca, and the nearby ruins of Monte Albán, offer a glimpse into the Zapotec and Mixtec cultures. Oaxaca is renowned for its vibrant arts scene, traditional crafts, and culinary delights. Visitors can explore the colorful markets, sample mole (a traditional Mexican sauce), and participate in the lively Day of the Dead celebrations.

Cancún and the Riviera Maya: For those seeking sun and sand, Cancún and the Riviera Maya offer pristine beaches, turquoise waters, and luxury resorts. Beyond the beaches, visitors can explore the underwater museum MUSA, dive in the Great Maya Reef, or visit the eco-archaeological parks Xcaret and Xel-Há.

Guadalajara: Guadalajara, Mexico’s second-largest city, is the birthplace of mariachi music and tequila. The city’s historic center boasts colonial architecture, including the Guadalajara Cathedral and the Instituto Cultural Cabañas. The nearby town of Tequila offers tours of agave fields and distilleries, providing an in-depth look at the production of Mexico’s iconic spirit.

Copper Canyon: In northern Mexico, the Copper Canyon (Barranca del Cobre) is a series of six interconnected canyons, deeper and larger than the Grand Canyon. The region is perfect for hiking, horseback riding, and taking the famous Chihuahua al Pacífico Railway, which offers breathtaking views of the rugged landscape.

Best Time to Visit Mexico

Mexico’s diverse climate means that the best time to visit varies by region and interest:

Coastal Areas: For beach destinations like Cancún, Puerto Vallarta, and Los Cabos, the dry season from November to April is ideal. Temperatures are warm, and there is little rainfall, making it perfect for water activities and sunbathing.

Central Highlands: Mexico City, Guadalajara, and Oaxaca enjoy a mild climate year-round. However, the best time to visit these areas is during the dry season from November to April. This period offers pleasant temperatures and minimal rain, ideal for exploring urban and archaeological sites.

Northern Mexico: In the desert regions and Copper Canyon, spring (March to May) and autumn (September to November) provide moderate temperatures suitable for outdoor activities. Summers can be extremely hot, while winters are cooler and sometimes snowy in higher elevations.

Southern Mexico: The southern states, including Chiapas and the Yucatán Peninsula, experience a tropical climate. The dry season from November to April is the best time to visit, offering warm temperatures and lower humidity. This is also an excellent time for exploring Maya ruins and natural attractions.

Conclusion

Mexico, with its rich historical heritage, diverse landscapes, and vibrant culture, offers a multitude of experiences for travelers. From the ancient ruins of Teotihuacán and Chichen Itza to the bustling streets of Mexico City and the serene beaches of the Riviera Maya, the country promises unforgettable adventures. Whether exploring its past, enjoying its natural beauty, or immersing in its cultural festivities, Mexico’s allure remains timeless, making it a destination worth visiting throughout the year. Additionally, check holidays in Mexico prior to travel to improve your overall tour experience.

1 note

·

View note