#Cinématographe

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

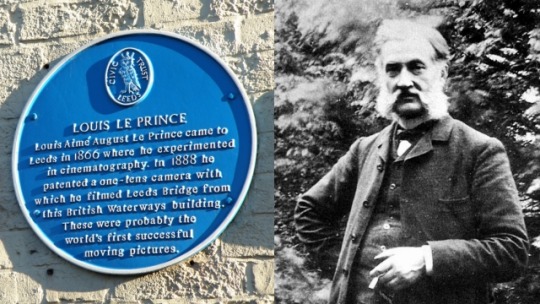

14 octobre 1888 : tournage du premier film de l’histoire par Louis Le Prince ➽ http://bit.ly/Premier-Film Si la date mémorable du 28 décembre 1895 est celle de la première séance publique et payante du cinématographe organisée par les frères Lumière, on peut considérer que le premier « film » fut obtenu, grâce au procédé de chronophotographie, sept ans plus tôt par l’inventeur Louis Aimé Augustin Le Prince

#CeJourLà#14Octobre#Film#Cinéma#Cinématographe#LePrince#Inventeur#Chronophotographie#Photographies#Animation#Techniques#Technologie#Inventions#histoire#france#history#passé#past#français#french#news#événement#newsfromthepast

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Après le repas chez isa, le retour par la gare de la Ciotat mondialement connue pour être le lieu de tournage d'un des premiers films au monde à avoir été tournés - par les frères Lumière, inventeurs du cinématographe, et projetés !

Retour à Marseille en train, donc, en passant par Saint-Marcel et son noyau villageois...puis de grands ensembles et la gare de la Blancarde...

#la ciotat gare#gare de la ciotat#louis lumière#frères lumière#cinématographe#marseille#la blanarde#saint-marcel

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I saw this t-shirt and had to have it.

0 notes

Text

Laurent Delmas - Jean-Paul Belmondo

A ceux qui croivent que Belmondo n’est que l’acteur agité de ses films de gangsters, qu’ils passent leur chemin. L’essai de Laurent Delmas n’est pas fait pour eux ! Plutôt qu’une biographie chronologique, Laurent Delmas, le cinéphile reconnu, animateur de l’émission, On aura tout vu sur France inter, propose de découvrir l’ampleur de sa carrière cinématographique par chapitres thématiques…

View On WordPress

#Artiste#Artiste français#Beaux livres#Billet littéraire#Biographie#Chronique littéraire#Chronique livre#Chroniques littéraires#Cinématographe#cinema#Comédien#Essai#Film#Film français#Films#Littérature francaise#Litterature contemporaine

0 notes

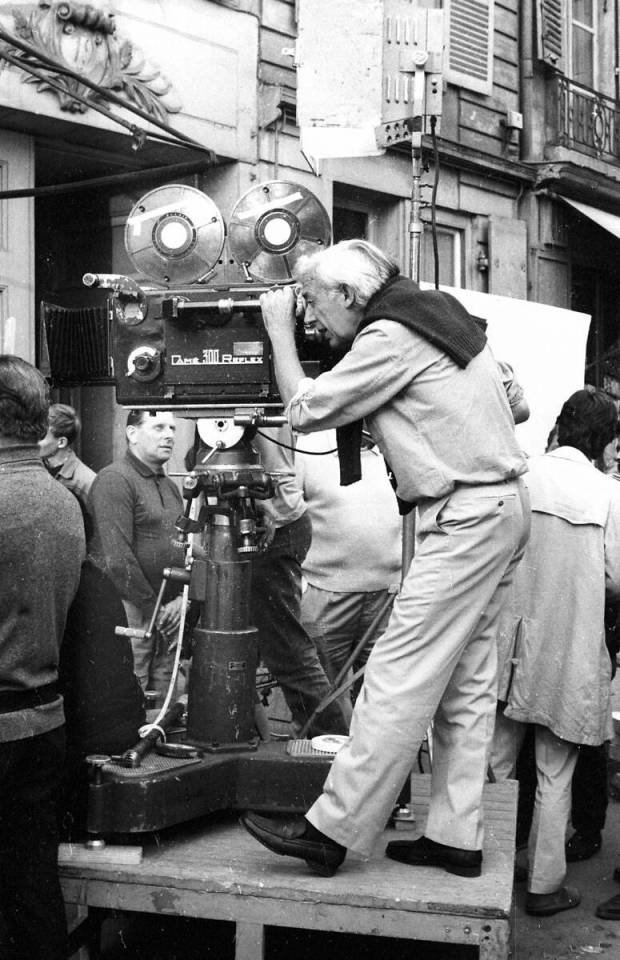

Photo

Photos S. B. : Bordeaux, rive droite - 2023 Montage. Passage d'images mortes à des images vivantes. Tout refleurit. « Notes sur le cinématographe », Robert Bresson.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Corot : Il ne faut pas chercher, il faut attendre. Robert Bresson, Notes sur le cinématographe, Gallimard, 1975

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Notes sur le cinématographe

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cinématographe Lumière par Marcellin Auzolle, 1895.

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

14 octobre 1888 : tournage du premier film de l’histoire par Louis Le Prince ➽ http://bit.ly/Premier-Film Si la date mémorable du 28 décembre 1895 est celle de la première séance publique et payante du cinématographe organisée par les frères Lumière, on peut considérer que le premier « film » fut obtenu, grâce au procédé de chronophotographie, sept ans plus tôt par l’inventeur Louis Aimé Augustin Le Prince

#CeJourLà#14Octobre#Film#Cinéma#Cinématographe#LePrince#Inventeur#Chronophotographie#Photographies#Animation#Techniques#Technologie#Inventions#histoire#france#history#passé#past#français#french#news#événement#newsfromthepast

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

La Ciotat, fin août.

L'Eden Théâtre est la plus vieille salle de cinéma au monde, qui a vu les premiers films des frères Lumière.

Sur la 2, c'est la Chapelle des Pénitents Bleus.

#la ciotat#éden théâtre#cinéma#cinématographe#frères lumière#louis lumière#chapelle des pénitents bleus#provence

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Lumière and Company (1995, original title "Lumière et Cie") was a collaboration between 41 international film directors in which each made a short film using the original Cinématographe camera invented by the Lumière brothers. Shorts were edited in-camera and abided by three rules: 1. A short may be no longer than 52 seconds 2. No synchronized sound 3. No more than three takes

(via Lumière and Company - David Lynch - YouTube)

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Next movie recommendation: "The Wizard of Oz."

The castle is dead and dark in the middle of the night, even Lumiere and Plumette long gone to bed, but Cogsworth cannot sleep.

He patters downstairs, his brown slippers dragging down low at the heel, the dark windows staring at him as he slips from hall to hall to hall. Each long mirror feels like an eye: he seems himself resting in the center, a small and moving pupil, walking into the gaze and out of it. His brown robe is knotted tight around him. He descends into the palace, each step darker than the last, losing the moon as he goes deeper inside.

The fight with Lumiere is still plaguing on his mind. He hasn’t felt right, since the curse. He still feels himself ticking away, and he’s infuriated by the idea that now that everything is normal again, he should just let time move on, not say, wait, hold on, there were ten years of grief and sadness there. Lumiere is dancing and laughing and it drives him mad, to see him human again, to remember all those years waiting stuck in metal and brass, to think that all the color has come rushing back when he just feels old, and old, and old. This palace doesn’t belong to him anymore. Lumiere doesn’t belong to him anymore. The curse is broken, and everything is new—too new for an old man, who always wanted everything to stay the same; who always wanted to keep to a certain beat, never too strange, never too colorful.

There is a small den, in the lower South wing, that no one really frequents much, beyond Lumiere in one of his recumbent moods. (Wild man, maniac, too colorful to be endured, thinks Cogsworth, soaked in the dark of the palace.) There’s a small white screen of canvas, here, and an odd contraption Lumiere calls a cinématographe. There’s a stack of old tapes, little ratty boxes, stacked high next to the machine. Cogsworth’s eyes take in titles: Rebecca, The Lady Vanishes, The 39 Steps.

He isn’t ready for those kind of movies tonight. He picks up an old favorite, The Wizard of Oz, and puts it in.

Nobody knows he watches this.

But he knows every beat, every refrain. Watching Dorothy run down the road, brown and grey and windblown, he thinks I know that feeling. That feeling of having to run away and toward every single problem that comes his way. You try to escape and you run into your problems anew, just in different forms: a witch is a witch, a fool a fool. The three farmhands go tumbling and Cogsworth shakes his head.

It isn’t fair an old dusty movie, brown and grey for its first ten minutes, should have so much meaning in it. For god’s sake, he thinks, as Dorothy touches down in Wonderland and has Munchkins coming out of every corner, you can practically see the glitter being dusted down on those children before they’re shoved out in front of camera. It’s all just Hollywood glitz and glitter. A little vaudeville shenanigans and some aging jokesters; this thing is a relic.

Cogsworth, tucked tight in his brown bathrobe, holding the popcorn he heated up in the dusty brown corner microwave, feels a bit like a relic.

But to laugh at how old the movie is to forget how enchanting Oz remains, despite of it all—no, because of it all. It is a joy to watch the Scarecrow’s dancing, old-school soft-shoe nonsense, and the gags that wore out before Lincoln was born, and to melt before Dorothy as she trembles and stumbles and remains oh, so brave—well, to laugh at the old would be to laugh at the joy, and Cogsworth will not have that. He will not give up on something he loves.

So he eats his popcorn, and mumbles along with the songs (“…if I only had a heart…”), and tells himself he isn’t tearing up when Dorothy breaks down, I’m frightened, Auntie Em, I’m frightened, and Auntie Em doesn’t hear her through the glass. An old man has no right to still feel so childish, so sad, so frightened. An old movie sits with him, in the dark, and glows ruby red and cornfield yellow and a green more green than emeralds.

I want to go home.

This is a movie all about home, though we spend precious little time in the version Dorothy speaks of. She speaks of it, often, and her voice is never far from the cry I want to go back home—but vivid under that sincere wish to run back to dust, and brown, and the old broken things that were loved so much, is a clear and obvious counterpoint: Dorothy is already home. She’s home the second she finds her friends again, never mind their enchanted forms, never mind they don’t look quite the same or remember her exactly. Dorothy makes a home in Oz without even realizing it, because home doesn’t have a shred to do with the old brown chicken coop or the broken iron bed—the home she wants to go back to, the home she already has, is the one she made with her friends, those weird and wild characters, who love her as she is, whether in dusty brown or glorious Technicolor. Home was waiting for her all along, and though Glinda thinks it’s the shoes that take her there, he can’t help feeling it’s her feet—her feet that carry her out of one home into another, into one bright and honest and oh, I think I’ll miss you most of all.

“I missed you most of all,” says Lumiere, over his shoulder, and Cogsworth would be furious if he wasn’t reaching up to hold his hand.

"You know I missed you most of all," says Lumiere, sliding over the couch and into his lap, "you know that didn't change when we were back to our old selves, didn't you?"

"I thought..." I don't know what I thought, thinks Cogsworth. "I thought maybe the ten years didn't matter. All the things we...we thought in those ten years. That maybe...maybe now that we're human again, we can't..can't feel the things we...."

"You are an old fool," says Lumiere, kissing him softly on the head.

"I guess some things never change," Cogsworth chuckles, and Dorothy is home again, home again free.

#who cares if it's old who cares if we're crying. we finally got home after so long away. We were here all along looking like this.#We’re home we're home we're home#batb fanfic#beauty and the beast#lumiere#cogsworth#lumiworth#movie nights <3 yes they watch it again. yes they kiss more. perfect movie perfect love

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Printemps 1919 - Champs-les-Sims

3/4

J'en suis d'autant plus heureuse pour vous alors que je mesure chaque jour que des rivalités peuvent persister entre des enfants issus des mêmes parents et qui ont toujours vécu ensemble, alors même que je poursuis mes efforts.

Je ne suis pas sure que Madame Eugénie se rende compte de ce qu'elle fait. Depuis toujours, Cléo est jalouse de sa grande soeur qui reçoit de leur père plus d'attention. Cléo est une jeune fille fantasque, bruyante et assez impulsive, plus sensible et impressionnable qu'elle ne veut bien l'admettre, alors que Noé est le type même de la fille modèle au sens où l'entend son aïeule : douce, gentille, obéissante, et assez effacée. Elle ne cesse de dire qu'elle lui rappelle sa petite Lucrèce, comme si je n'en avais déjà pas assez qu'elle compare Antoine à Maximilien !

Il y a peu, j'ai emmené les enfants à une projection dans notre petit théâtre local. J'ai souvent négligé d'en parler, car il s'agissait du dernier projet de ma chère Marie, qui voulait amener la magie du cinématographe jusque chez nous. Depuis son décès, c'est son fils Alexandre qui a religieusement repris le flambeau. Bref, il a obtenu le mois dernier une copie du film Le Calvaire d'une reine et nous sommes allés le voir. Cléo a été transfigurée par les interprétations de Gabrielle Robinne et Léontine Massart. Depuis, sa vie semble être un long film. Elle se noircit les yeux comme dans les films et a coupé ses cheveux courts comme ceux de Massart. Madame Eugénie désapprouve, bien sur, et ne cesse d'enjoindre ma fille à imiter son aînée. Cela met ma Cléo dans des états de colère intenses, et Sélène m'a confié qu'elle pensait que toutes ces transformations ont avant tout pour motivation de se différencier complètement de sa jumelle sur le plan physique. Ma Cléo se cherche, comme tant de jeunes filles de son âge avant elle, et j'aimerai tant que Madame Eugénie ait sur elle un regard un peu plus bienveillant.

Transcription :

Eugénie « ... »

Cléopâtre « Qu’y a-t-il encore Grand-Mère ? SI vous soupirez autant, c’est que vous avez quelque chose à dire non ? »

Eugénie « Tu sais bien que tu es trop jeune pour ce genre de maquillage. Tout ce noir autour de tes yeux, c’est si laid ! »

Cléopâtre « Maman dit que ça me va bien. Cela met en valeur mes yeux justement, et ça me vieillit un peu. »

Eugénie « Quelle jeune fille de treize aurait besoin de se vieillir ainsi ? Ce n’est pas de cette façon que l’on atteint la maturité. Prends donc exemple sur ta sœur ! »

Cléopâtre « Oui, Grand-Mère. Comme toujours, Grand-Mère... »

#lebris#lebrisgens4#history challenge#legacy challenge#decades challenge#nohomechallenge#sims 3#ts3#simblr#sims stories#eugénie le bris#Albertine Maigret#Eugénie Bernard#Cléopâtre Le Bris#Arsinoé Le Bris#Lucrèce Le Bris#Marc-Antoine Le Bris#Maximilien Le Bris#Marie Ribeaucourt#Alexandre Barbois

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

January 1, 2024: The Great Train Robbery (1903)

I LIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIVE

So. It's been a while. Life has been busy for the last couple of years, lemme tell you. I love this blog and I love movies, but writing can be...time-consuming for me. Anyway, I figure, why not start this whole thing over again, huh? Well, mostly. Am I gonna get to 365 movies this year? Frankly, that's unlikely, for a number of reasons. BUT! I can at least start small. And, since doing action films in January is a bit of a blast from the past...why not go all the way back this time? Plus, hey - it's a good way for me to get back into the swing of things.

Film history time!

Without going too far into it, the modern film industry began in the 1890s. The first moving pictures were mostly short documentaries, showing live as captured through multiple successive images. L'arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat is often called the first film publicly shown, but that's a misconception. What is true, however, is that the film was made by two luminaries in film history: the Lumiere brothers. Their invention, the cinématographe, was essentially an early film camera, and the brothers used it to document real life.

However, for every good 19th century inventor, there's got to be a rival. And honestly, when you're talking about the 1890s, there's only one real rival to speak of for a given inventor: the Wizard of Menlo Park.

Edison, of course, is legendarily one of the biggest assholes in American history. However, to his credit, the man was genuinely brilliant. Coming up with or perfecting various contraptions and inventions, Edison was a dynamo. In 1889, he had the idea for a device that could capture and display visuals to accompany sounds from the phonograph (which he'd, of course, invented). He had a member of his think tank, William Kennedy Dickson, develop the device, and they created their own early video camera of sorts. With the combination of these two teams, amongst others here and there, the first films began distribution around 1893.

However, again, these were mostly capturing real-life footage. The first narrative films began around 1896, likely with La Fée aux Choux in that year. A minute-long film, this is arguably the first non-documentary to be produced, and would be the first of a new industry. And, fun fact, the first film to be directed by a woman, Alice Guy! After this, the Edison Manufacturing Company released the first commercially available film, The Kiss, and made buckets of cash. The film industry is born.

But to really hit the head on narrative film, you have to go back to France. There, illusionist Marie-Georges-Jean Méliès expanded the genre with creative sets and productions that took film into the realm of the fantastic. Inventing a number of basic tricks like dissolves and multiple exposures, Georges is the true pioneer of early film. His 1902 film, Le Voyage Dans La Lune (you know, the one where they land a ship in the Moon's eye) is considered a classic to this day, amongst other Méliès staples like Cendrillon and Le Manoir du Diable.

However, Georges isn't alone. The UK has a slew of filmakers entering the scene with their own efforts, while in the US, Edison's company is continuing their work as well. Most prominently for this story, perhaps, is the work of one of Edison's early cameramen, and therefore one of his first directors, Edwin S. Porter. Porter started with Edison in 1901, and was one of the first real film scholars. Taking from the other prominent directors of the day, he injected craft into the films he worked on for the company. At this point, one of the big things in American cinema was the brand new Western genre.

This is the point to clear up a bit of a misconception about Western films: The Great Train Robbery was in no way the first one. OK, so, the Western has its origins in Wild West shows, like Buffalo Bill's Wild West, which would travel around the world to show off the adventure and action of the American West. In fact, that GIF up above is Annie Oakley, who was filmed by Edison's Kinetoscope as an early film doing her sharpshooting act, which was a part of the show! Anyway, these exhibitions also traveled to the UK, where they made a massive impact. America was the land of the Wild West, and it arguably wouldn't shake that image until around World War II.

Because of this, the first Western films were actually filmed in England, not the United States! The first was Kidnapping by Indians in 1899, followed by A Daring Daylight Burglary in 1903. That film in particular inspired Potter, alongside an 1896 play called The Great Train Robbery, to make...well, you read the title of the review. That film is sometimes called the first Western film by mistake, but is usually forgotten in favor of Porter's film. In any case, though, the Western genre was born in the silent film era.

From that point, of course, history is made. Stars like Tom Mix, John Wayne, and Jay Silverheels make their way into the public zeitgeist. Characters like Bronco Billy, or the Lone Ranger and Tonto become household names. Classic films like Stagecoach and more bring the genre to new heights, while even comedians like Laurel and Hardy (above) get into the game with Way Out West. Even actual Western figures like Wyatt Earp became a part of the industry briefly, consulting on how things were in those wild days. It was a new dawn for film, and a unique era.

Of course, I've talked about Westerns before. Didn't get to cover much that month, but I covered a few films like Stagecoach. I even got some facts wrong in that recap about the first Western! Go figure. Anyway, that's a brief history of the Western film genre up to this point. But why cover this now? Well, this is also, for all intents and purposes, one of the first action films in cinema history. Ironically, the idea of action on screen would kick off an entirely different genre. Rather than spinning off into the Western, which became its own thing, the first iteration of the action genre was the adventure film, and guns were supplanted by another weapon.

...I really wanna talk about this film on this blog, because I adore it so much. Anyway, the swashbuckler was the next real action film genre to emerge, but that's a question for the next review, I think. In the meantime, let's get to The Great Train Robbery! This post is a little bit of a return to form for me, writing a recap and review with my 5 categories of criticism. This format might not be maintained with every film I talk about this year (however many that'll be), but I'll play it by ear depending on the film! And, so, without further ado...

SPOILERS AHEAD!!!

Recap

This recap is gonna be kinda weird, since as far as I can tell...there are no dialogue cards in this movie. A lot of what I'm writing here is a combination of inference and observation, as well as coordinating it with other synopses online after I'm done writing. So, yeah, this is an interesting one. Completely silent, as well.

A pair of bandits enter the room of a telegraph office, holding the clerk at gunpoint, and ordering him to write a missive of some kind before tying him up. The entire team of four bandits wait outside of the water tower used to refuel this old steam train, then sneak aboard. They immediately enter a firefight with a mail clerk on the train (who's apparently packing, damn), and kill him, then use a stick of dynamite to open a box that I assume contains valuables.

Two of the bandits climb to the top of the train, where one has a fist-fight with the fireman and...throws him off the train, damn! It's a dramatic throw, too. Anyway, once this happens, the train stops, and the bandits hold the passengers hostage aboard the train as the engine car is disconnected. The passengers are held up for their belongings, and...Jesus, guys, there are a LOT more of you than there are of the gunmen! Somebody just jump one of 'em!

Well, as if to answer my question, one of the passengers tries to run away, and gets shot in the back for his trouble. So, yeah, OK, I see the risk, but...I dunno, they only have so many bullets, I think you guys could take 'em. Anyway, the bandits escape, and the passengers immediately tend to the one who was shot. The bandits board the engine car and take off with their loot.

The party escapes into the woods a-ways down the train tracks, and meets up with their waiting horses. Meanwhile, the operator back at the station manages to get up and send out a message. His young daughter walks in and VERY smartly cuts her dad loose, making her the official hero of the film. She wakes him up, and we cut back to a dance party attended by some local lawmen. We get that Western trope where the lawmen shoot at a guy's feet to get him to dance, leading me to wonder if this is where that trope comes from?

The operator bursts in and tells the group of the trouble. They ride out to confront the bandits on horseback, but one of them gets shot in the process. Eventually, this leads to an all-out brawl in the woods, where the bandits are cut down as they count their loot. Good guys win, and the entire film ends with this classic shot of one of the bandits.

Review

So! Can I even review this one the way I would normally? I mean, probably; short films and silent films are still both films, after all, so it's not like it doesn't qualify. But there are some things obviously missing, or that need to be taken into context here. So, to go through it via bullet point method:

Cast and Acting - 7/10: Well, the actors are mostly forgotten, sorry to say; and while we know their names, none of them were actually credited in the film. The main character is arguably the bandit leader, as played by Justus Barnes, and possibly Gilbert Anderson as a few characters (including the dancer in the dance hall and the shot passenger), and Robert Milasch as the tied-up clerk (I think). Plus, it has arguably the first child actor in the form of Marie Snow, but that may need to be fact-checked. Still, they were all fine, especially for the time. Acting for no audience was sort of a new thing, after all. Hard to judge, this one.

Plot and Writing - 8/10: Hey, there is a plot, even if there's not really writing beyond a screenplay. Our writers here are director Edwin S. Porter and Scott Marble, who wrote the play this was based on. And for what it's worth, it's a simple plot. Men rob train, men get stopped. That's it. Not exactly Primer, this one.

Directing and Cinematography - 8/10: For what it's worth, I think Edwin S. Porter did a decent job in this outing. Again, this is a new doctrine entirely, so it's not like we're gonna find much creativity in either category here. Hell, according to some angles, Porter technically invented the concept of direction, but that's a very nuanced take on his role. At this point, directing just meant pointing the camera. Cinematographer (and yes, there was one) J. Blair Smith also did fine, as far as I'm concerned. Plus, hey...that last shot is iconic.

Production and Set Design - 9/10: Honestly, felt like I was watching a train robbery. So, it may feel a little Party City in terms of the bandit and lawmen costumes, but it also was authentic, so...yeah, high marks for this one.

Editing - 9/10: Normally, of course, I'd put music in this category, but...well, there's no music. So, it falls to editor...uh...oh. Shit. Wait, there's no actual editor for this one? I guess the closest I can get is Edwin S. Porter, who really carried this film. And there is editing, there has to be. After all, it managed to tell a story with literally no dialogue. No cards, no mouthed word, no music, nothin'. And yeah, I really wish that first or last one was in here at least, but the film still works without it.

So, yeah, in the end, that's an 84% for me! Which is probably causing some elderly film critic's tenderly cared-for stress-rage aneurysm to finally pop, but hey - it's how I feel. Great piece of history, completely free, and required cinephile viewing! Just go to Wikipedia or the Library of Congress.

OK, with that short-fill warm-up finally done, let's proceed through action film history! Good to be back!

Next: Captain Blood (1935); dir. Michael Curtiz

#user365#365 days 365 movies#365 movies 365 days#365 movie challenge#action january#action#action movie#western#western film#action film#action genre#edwin s porter#edwin s. porter#the great train robbery#the great train robbery 1903#365days365movies#silent film

5 notes

·

View notes