#gare de la ciotat

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Après le repas chez isa, le retour par la gare de la Ciotat mondialement connue pour être le lieu de tournage d'un des premiers films au monde à avoir été tournés - par les frères Lumière, inventeurs du cinématographe, et projetés !

Retour à Marseille en train, donc, en passant par Saint-Marcel et son noyau villageois...puis de grands ensembles et la gare de la Blancarde...

#la ciotat gare#gare de la ciotat#louis lumière#frères lumière#cinématographe#marseille#la blanarde#saint-marcel

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

me and the boys (both circumcised) on movie night

#wwdits#what we do in the shadows#nandor the relentless#l'arrivée d'un train en gare de la ciotat#(we’re about to run away in terror) (the train is coming right at us)

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Time travel to 1896.

Replace the L'arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat film reel with a copy of Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse.

Leave.

#l’arrivée d’un train en gare de la ciotat#the arrival of a train at la ciotat station#the arrival of a train#spider-man: across the spider-verse#spider-man#spider-verse#across the spider-verse#atsv

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

if a bunch of films are getting remakes, can i request a remake of the l'arrivée d'un train en gare de la ciotat?? it's such a sound film, and the new generation are really missing out getting to see it on the big screen. i think hugh dancy would really fit the main role.

#/satire#classic film#l'arrivée d'un train en gare de la ciotat#film remakes#the arrival of a train#the lumière brothers

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's so cool how the new Genshin event has references to actual French film-makers!!

Melies is from Georges Méliès who made Le Voyage Dans La Lune (A Trip To The Moon), Petit Lumiere and his brother are the Lumière brothers who made La Sortie des ouvriers de l'usine Lumière (Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory) and L'Arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat (The Arrival of a Train in the Ciotat Station) which he both references when he talks to the Traveler and Paimon!!

This is so cool hehehe

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Demons [Dèmoni] (1985)

When the movie starts on a scare the likes of which filmgoers hadn’t seen since “L’Arrivée d’un train en Gare de La Ciotat,” you know you’re in for a treat. Lamberto Bava’s pulpy gore-fest gets the scene-setting, if it could be called that, through quickly enough: folks show up at a new cinema in Berlin, and the shit hits the fan pronto. It’s easy to ridicule the film for a lack of interior logic or sense of continuity. For one thing, a quartet of punks exist solely to add to the already staggering body count, and because someone thought that the image of a person snorting coke out of a Coke can would be hilarious. And the late reveal of a helicopter crashing through the roof of the cursed cinema makes absolutely no goddamn sense until well after it’s happened and all is revealed that things have escalated to outright In the Mouth of Madness tier apocalypse outside these walls. But aside from stating the obvious (nobody gave a shit about silly little details like that during the production), it’s funny how on one level Demons is a jarringly stark commentary on society’s fundamental inability to respond to emergency situations. After they find themselves to be trapped in the cinema, all of the disposable stereotypes assembled almost immediately sign their own death certificates. General chaos is the rule of thumb, with everyone working against one another in their panic. Try to assert yourself and take control of the situation? Sorry, still gonna meet an ignominious end. Go into a state of catatonia? Not helping. The real trick is simply to ooze main character energy. Also having a sweet katana bequeathed to you by your dying friend and a motorcycle that is on exhibit and yet apparently totally gassed up certainly helps.

But let’s be real, this is about the gore. This earns top marks in its intent and, well, maybe we should grade on a curve for execution. The ideas, the sheer number of ways that people are horribly maimed and killed, are relentlessly creative and fucked up. Even if Dario Argento produced this, the effects more align themselves with father Mario Bava’s proto-slashers or Lucio Fulci’s depravity: eyes are gouged on multiple occasions, fingernails split and deformed, teeth displaced, demons sent bursting from distorted backs. But for all of the glorious cringes and winces it inspires, there are a few moments when… well, now her face looks mostly like plastic so I guess something fucked up is about to happen. At least they warned us. Now we just need a nice boyfriend to tell us when it’s safe to look back at the screen, and to promise he’s not lying.

THE RULES

SIP

A song starts.

Someone drinks Coke with a straw (or starts bumpin' that).

A named character dies.

BIG DRINK

The Metropol Theatre logo appears.

Silver mask features in a scene.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hugo (2011)

Martin Scorsese is not known for his family films. You associate the name with gritty crime stories. So what drew him to Hugo? Perhaps he wanted to try something different? On top of being suitable for the whole family, the picture makes impressive use of 3D and special effects. If you’ve seen Hugo the whole way through, you’ll know why. I suspect Scorsese connected to this story on a deeply personal level.

In 1931 Paris, 12-year-old Hugo Cabret (Asa Butterfield) maintains the clocks at Gare Montparnasse railway station. His alcoholic uncle Claude officially does the work but he’s been gone for months and as long as the machines keep the time, Station Inspector Gustave Dasté (Sacha Baron Cohen) won't ask any questions. This means Hugo is free to focus on the automaton he and his father were repairing before he became orphaned. Hugo keeps to himself, occasionally stealing parts from a toy store owner, Georges (Ben Kingsley). After he is caught and his book on the automaton is confiscated, Hugo befriends the toy maker’s goddaughter, Isabelle (Chloë Grace Moretz). He hopes she can help him get his book back.

There’s no way you can guess where this movie is going. The surprises along the way are a big part of the fun and the screenplay by John Logan (based on The Invention of Hugo Cabret by Brian Selznick) is in no hurry to get to its big reveals. As Hugo goes about his day, we meet all the characters who frequent the station. Richard Griffiths plays a man pining for a dog owner (played by Frances de la Tour) whose pooch can’t stand him. Shy Inspector Dasté wants to approach a beautiful flower saleslady (Emily Mortimer) but is embarrassed by an old war injury. Christopher Lee plays the owner of a book store who probably knows more than he lets on, Papa Georges is hiding something from Isabelle. And then there’s the automaton Hugo is repairing. How is it tied to his father? There’s enough going on with these characters that it doesn't matter if you don't know where the plot is going. You’re having a great time simply getting to know them, admiring the performances (Moretz does a flawless accent) and enjoying Scorsese's direction. Check out the way the camera moves down chutes, through crowds and then into the secret openings into Hugo’s home or the breathtaking shots of a long-gone Paris.

Ultimately, this is a small, personal story. The world’s fate does not rest in the hands of Hugo. The secrets we uncover deal with very human tragedies but it’s shot like all of reality hinges on the lonely boy finding a friend. After Hugo is over, you remember specific shots, specific characters and the emotions you felt while watching them. These would attract any director but I suspect Scorsese wanted this project specifically because the film contains numerous references to specific events in the history of cinema. We see a clip of Harold Lloyd’s Safety Last! and the film’s most iconic shot is re-imagined later on. The Montparnasse derailment of 1895 is reimagined and Scorsese gives us to opportunity to relive the shocked reaction audiences would’ve had while viewing “L'Arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat” - that famous shot of a train coming towards the camera that supposedly had audiences falling out of their seats in terror - by shooting it in 3D - literally having the train come right towards the screen and frighten us. There are many other references to the history of cinema throughout. If you love movies, you’ll get an extra kick out of these scenes.

Hugo is moving, warm, romantic, tragic and exciting. It goes in unexpected directions and the surprises make the movie feel big while also keeping it small and intimate. The performances are excellent, the characters fully realized. The only mark against it comes from the presentation. This movie is meant to be seen on the big screen and in 3D. Few people will be able to see it that way now. If that’s the only flaw you can find in a movie, it's doing a lot of things right. (On Blu-ray, September 25, 2020)

#Hugo#movies#films#movie reviews#film reviews#Martin Scorsese#John Logan#Brian Selznick#Ben Kingsley#Sacha Baron Cohen#Asa Butterfield#Chloe Grace Moretz#Ray Winstone#Emily Mortimer#Jude Law#2011 movies#2011 films

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rip the audience for L'Arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat they would have loved subway surfers

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

January 1, 2024: The Great Train Robbery (1903)

I LIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIVE

So. It's been a while. Life has been busy for the last couple of years, lemme tell you. I love this blog and I love movies, but writing can be...time-consuming for me. Anyway, I figure, why not start this whole thing over again, huh? Well, mostly. Am I gonna get to 365 movies this year? Frankly, that's unlikely, for a number of reasons. BUT! I can at least start small. And, since doing action films in January is a bit of a blast from the past...why not go all the way back this time? Plus, hey - it's a good way for me to get back into the swing of things.

Film history time!

Without going too far into it, the modern film industry began in the 1890s. The first moving pictures were mostly short documentaries, showing live as captured through multiple successive images. L'arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat is often called the first film publicly shown, but that's a misconception. What is true, however, is that the film was made by two luminaries in film history: the Lumiere brothers. Their invention, the cinématographe, was essentially an early film camera, and the brothers used it to document real life.

However, for every good 19th century inventor, there's got to be a rival. And honestly, when you're talking about the 1890s, there's only one real rival to speak of for a given inventor: the Wizard of Menlo Park.

Edison, of course, is legendarily one of the biggest assholes in American history. However, to his credit, the man was genuinely brilliant. Coming up with or perfecting various contraptions and inventions, Edison was a dynamo. In 1889, he had the idea for a device that could capture and display visuals to accompany sounds from the phonograph (which he'd, of course, invented). He had a member of his think tank, William Kennedy Dickson, develop the device, and they created their own early video camera of sorts. With the combination of these two teams, amongst others here and there, the first films began distribution around 1893.

However, again, these were mostly capturing real-life footage. The first narrative films began around 1896, likely with La Fée aux Choux in that year. A minute-long film, this is arguably the first non-documentary to be produced, and would be the first of a new industry. And, fun fact, the first film to be directed by a woman, Alice Guy! After this, the Edison Manufacturing Company released the first commercially available film, The Kiss, and made buckets of cash. The film industry is born.

But to really hit the head on narrative film, you have to go back to France. There, illusionist Marie-Georges-Jean Méliès expanded the genre with creative sets and productions that took film into the realm of the fantastic. Inventing a number of basic tricks like dissolves and multiple exposures, Georges is the true pioneer of early film. His 1902 film, Le Voyage Dans La Lune (you know, the one where they land a ship in the Moon's eye) is considered a classic to this day, amongst other Méliès staples like Cendrillon and Le Manoir du Diable.

However, Georges isn't alone. The UK has a slew of filmakers entering the scene with their own efforts, while in the US, Edison's company is continuing their work as well. Most prominently for this story, perhaps, is the work of one of Edison's early cameramen, and therefore one of his first directors, Edwin S. Porter. Porter started with Edison in 1901, and was one of the first real film scholars. Taking from the other prominent directors of the day, he injected craft into the films he worked on for the company. At this point, one of the big things in American cinema was the brand new Western genre.

This is the point to clear up a bit of a misconception about Western films: The Great Train Robbery was in no way the first one. OK, so, the Western has its origins in Wild West shows, like Buffalo Bill's Wild West, which would travel around the world to show off the adventure and action of the American West. In fact, that GIF up above is Annie Oakley, who was filmed by Edison's Kinetoscope as an early film doing her sharpshooting act, which was a part of the show! Anyway, these exhibitions also traveled to the UK, where they made a massive impact. America was the land of the Wild West, and it arguably wouldn't shake that image until around World War II.

Because of this, the first Western films were actually filmed in England, not the United States! The first was Kidnapping by Indians in 1899, followed by A Daring Daylight Burglary in 1903. That film in particular inspired Potter, alongside an 1896 play called The Great Train Robbery, to make...well, you read the title of the review. That film is sometimes called the first Western film by mistake, but is usually forgotten in favor of Porter's film. In any case, though, the Western genre was born in the silent film era.

From that point, of course, history is made. Stars like Tom Mix, John Wayne, and Jay Silverheels make their way into the public zeitgeist. Characters like Bronco Billy, or the Lone Ranger and Tonto become household names. Classic films like Stagecoach and more bring the genre to new heights, while even comedians like Laurel and Hardy (above) get into the game with Way Out West. Even actual Western figures like Wyatt Earp became a part of the industry briefly, consulting on how things were in those wild days. It was a new dawn for film, and a unique era.

Of course, I've talked about Westerns before. Didn't get to cover much that month, but I covered a few films like Stagecoach. I even got some facts wrong in that recap about the first Western! Go figure. Anyway, that's a brief history of the Western film genre up to this point. But why cover this now? Well, this is also, for all intents and purposes, one of the first action films in cinema history. Ironically, the idea of action on screen would kick off an entirely different genre. Rather than spinning off into the Western, which became its own thing, the first iteration of the action genre was the adventure film, and guns were supplanted by another weapon.

...I really wanna talk about this film on this blog, because I adore it so much. Anyway, the swashbuckler was the next real action film genre to emerge, but that's a question for the next review, I think. In the meantime, let's get to The Great Train Robbery! This post is a little bit of a return to form for me, writing a recap and review with my 5 categories of criticism. This format might not be maintained with every film I talk about this year (however many that'll be), but I'll play it by ear depending on the film! And, so, without further ado...

SPOILERS AHEAD!!!

Recap

This recap is gonna be kinda weird, since as far as I can tell...there are no dialogue cards in this movie. A lot of what I'm writing here is a combination of inference and observation, as well as coordinating it with other synopses online after I'm done writing. So, yeah, this is an interesting one. Completely silent, as well.

A pair of bandits enter the room of a telegraph office, holding the clerk at gunpoint, and ordering him to write a missive of some kind before tying him up. The entire team of four bandits wait outside of the water tower used to refuel this old steam train, then sneak aboard. They immediately enter a firefight with a mail clerk on the train (who's apparently packing, damn), and kill him, then use a stick of dynamite to open a box that I assume contains valuables.

Two of the bandits climb to the top of the train, where one has a fist-fight with the fireman and...throws him off the train, damn! It's a dramatic throw, too. Anyway, once this happens, the train stops, and the bandits hold the passengers hostage aboard the train as the engine car is disconnected. The passengers are held up for their belongings, and...Jesus, guys, there are a LOT more of you than there are of the gunmen! Somebody just jump one of 'em!

Well, as if to answer my question, one of the passengers tries to run away, and gets shot in the back for his trouble. So, yeah, OK, I see the risk, but...I dunno, they only have so many bullets, I think you guys could take 'em. Anyway, the bandits escape, and the passengers immediately tend to the one who was shot. The bandits board the engine car and take off with their loot.

The party escapes into the woods a-ways down the train tracks, and meets up with their waiting horses. Meanwhile, the operator back at the station manages to get up and send out a message. His young daughter walks in and VERY smartly cuts her dad loose, making her the official hero of the film. She wakes him up, and we cut back to a dance party attended by some local lawmen. We get that Western trope where the lawmen shoot at a guy's feet to get him to dance, leading me to wonder if this is where that trope comes from?

The operator bursts in and tells the group of the trouble. They ride out to confront the bandits on horseback, but one of them gets shot in the process. Eventually, this leads to an all-out brawl in the woods, where the bandits are cut down as they count their loot. Good guys win, and the entire film ends with this classic shot of one of the bandits.

Review

So! Can I even review this one the way I would normally? I mean, probably; short films and silent films are still both films, after all, so it's not like it doesn't qualify. But there are some things obviously missing, or that need to be taken into context here. So, to go through it via bullet point method:

Cast and Acting - 7/10: Well, the actors are mostly forgotten, sorry to say; and while we know their names, none of them were actually credited in the film. The main character is arguably the bandit leader, as played by Justus Barnes, and possibly Gilbert Anderson as a few characters (including the dancer in the dance hall and the shot passenger), and Robert Milasch as the tied-up clerk (I think). Plus, it has arguably the first child actor in the form of Marie Snow, but that may need to be fact-checked. Still, they were all fine, especially for the time. Acting for no audience was sort of a new thing, after all. Hard to judge, this one.

Plot and Writing - 8/10: Hey, there is a plot, even if there's not really writing beyond a screenplay. Our writers here are director Edwin S. Porter and Scott Marble, who wrote the play this was based on. And for what it's worth, it's a simple plot. Men rob train, men get stopped. That's it. Not exactly Primer, this one.

Directing and Cinematography - 8/10: For what it's worth, I think Edwin S. Porter did a decent job in this outing. Again, this is a new doctrine entirely, so it's not like we're gonna find much creativity in either category here. Hell, according to some angles, Porter technically invented the concept of direction, but that's a very nuanced take on his role. At this point, directing just meant pointing the camera. Cinematographer (and yes, there was one) J. Blair Smith also did fine, as far as I'm concerned. Plus, hey...that last shot is iconic.

Production and Set Design - 9/10: Honestly, felt like I was watching a train robbery. So, it may feel a little Party City in terms of the bandit and lawmen costumes, but it also was authentic, so...yeah, high marks for this one.

Editing - 9/10: Normally, of course, I'd put music in this category, but...well, there's no music. So, it falls to editor...uh...oh. Shit. Wait, there's no actual editor for this one? I guess the closest I can get is Edwin S. Porter, who really carried this film. And there is editing, there has to be. After all, it managed to tell a story with literally no dialogue. No cards, no mouthed word, no music, nothin'. And yeah, I really wish that first or last one was in here at least, but the film still works without it.

So, yeah, in the end, that's an 84% for me! Which is probably causing some elderly film critic's tenderly cared-for stress-rage aneurysm to finally pop, but hey - it's how I feel. Great piece of history, completely free, and required cinephile viewing! Just go to Wikipedia or the Library of Congress.

OK, with that short-fill warm-up finally done, let's proceed through action film history! Good to be back!

Next: Captain Blood (1935); dir. Michael Curtiz

#user365#365 days 365 movies#365 movies 365 days#365 movie challenge#action january#action#action movie#western#western film#action film#action genre#edwin s porter#edwin s. porter#the great train robbery#the great train robbery 1903#365days365movies#silent film

5 notes

·

View notes

Video

L'Arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat (1895)

It's famous for frightening moviegoers, although that might just be a story to make past times people look silly. It's a pretty impressive thing to see out of nowhere, though! The whole clip is available at the link (it's not a full length movie, just a short shot).

70K notes

·

View notes

Text

fuuuuuuck they're doing a remake of l'arrivée d'un train en gare de la ciotat and chris pratt is playing the train

1 note

·

View note

Text

gonna steal @relevant-wikipedia-articles's thing for a second here

38K notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 04- Lighting in Films

Earliest Lighting in Film

In the late 1800s films were usually filmed during the day, as they purely used sunlight/ natural light. Indoor sets were built without a roof, or with a glass ceiling. As they did not utilize any artificial light (was introduced in 1900s) Light sources like Tungsten (1903) could not be used as the light rays it produced were predominantly from the red end of the spectrum. To which orthochromatic films of the era was relatively insensitive to.

L'Arrivee d'un train en gare de La Ciotat (1896) Train Pulling into a Station

Train pulling into a station, is a cinema legend where the audience, according to legend, were so startled by the realism that they ran out of the cinema.

La Fee Aux Choux (1896)

the first female director, Alice Guy-Blache, made her debut with La Fee Aux Choux fully utilized natural light only

Earliest use of (artificial) lighting in film

However D.W. Griffith changed the precedence by using soft artificial lighting in his work Enoch Arden by using a technique called bouncing or diffusing the light source of a shot.

Rembrandt Lighting Technique; Rembrandt lighting technique was inspired by Rembrandt’s oil paintings. This technique mimics the Tenebrism style, especially evident in Baroque era, that contains elements of dramatic lighting and violent contrasts of light and darkness. particularly created inverted triangled underneath the eye

Types of Lighting

Films lighting falls under one of two categories such as natural and artificial,

Sun, moon, fire, or fireflies fall under Natural light

Streetlights, neon lights, flashlights fall under Artificial light

However there are other categories such as 'Ambient light' which can either be artificial or natural, as it refers to any light the crew didn't bring on set (available lights). examples of this light can be streetlamps, sunlight, overhead lights at a restaurant, etc etc...

Although Ambient lights existence are an uncontrolled variable, you can still control how it hits the subject and what purpose it serves to your image, making it a motivated light.

Ambient light vs Natural light

Since these two terms will often be used interchangeably, there is a key difference between these two type of lights is that.

Not all ambient light is natural light, but all natural light is ambient light.

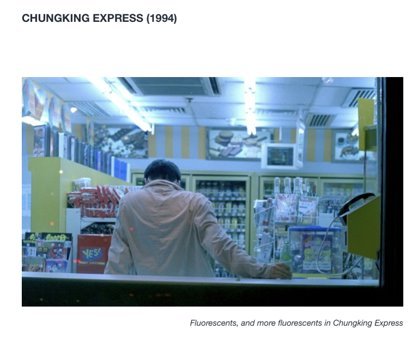

Chlose Zhao's work The Rider contains her signature visual palette on heavily relying on natural ambient light. Wong Kar Wai, director of Chungking express, on the other hand is known for his distinctive style of using artificial ambient light.

ambient light can also fall under a separate category, as seen in the above image, it can be referred to as 'Practical Lighting'; it is any light source that appears in the frame of a shot.

however, practical light doesn't have to be ambient, as it can be placed by a Gaffer.

Gaffer; head lighting electrician on set, who runs the entire electrical department of the crew and helps the director of photography achieve the desired shot

Practical Lighting is also closely related to Motivated Lighting. Motivated Lighting follows an approach which has logical reasoning for appearing the way it does in a shot.

George Miller's work fully utilizes this approach as explained; As the lamps serve as practical lights on either side of the character, the right lamp provides some edge light on her back and the left provides a diffused red glow on her face (so it seems) its likely that the red light on her face may be provided by another less aesthetically pleasing light off frame.

the harsh blue spotlight shining down on the object of the character's attention. we can also safely assume that the red light on her face maybe coming through the window in the bizarre. therefore the light being motivated as well.

3 point lighting

this is the most basic lighting set up used in film and photography. It usually consists of Key light, Back light, and Fill light.

this method is the most standard method used in visual media, where they can illuminate the subject in any way they want while also controlling shadows produced by direct lighting

1 note

·

View note

Text

Top horror game of 2024: L'arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat

0 notes

Text

Group of trans girls about to run the train on a girl call it L’Arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat the way she’s gunna be scared of the train that’s coming

0 notes

Text

The Competition of Early Cinema

To understand where we are, it is imperative to understand where we came from. As a film student, that means diving into the works of Thomas Edison, the Lumière Brothers, and Georges Méliès. Movies, movie cameras, and movie theaters as we know them would be completely different without these and other founding fathers of cinema, and so knowing about them is completely relevant. But how did these four push the world of moving pictures so far so fast? Competition.

All of these different early players, from Edison to the Lumières to Méliès, were all working at the same time: the mid 1890s. The Lumières’ Cinematographe was inspired by Edison’s Kinetoscope, and Méliès bought his own camera-projector after watching the Lumière Brothers in Paris. It’s like as Erkki Huhtamo said, “When presenting something ‘new’, both inventors and publicists often search support from existing technologies and cultural forms.” So, as stated previously, this created the most important thing when it comes to technological innovation: competition. Each of these filmmakers were trying to one-up the others, attempting to make their own films the most desirable. So, each of them looked to find ways to revolutionize what was being filmed. In “L'Arrivée d'un train en gare de la Ciotat,” the Lumières used a dynamic camera angle, rather than the straight-on filming from a distance that Edison used, to make the train appear as if coming straight towards the audience. As the latest arrival of the three to the cinematic circuit, Méliès pushed cinema forward even more, creating narrative films complete with special effects, brand new ideas like dissolves and multiple exposures, linear editing, and a killer production design to captivate audiences. After the hayday of those three, the cycle continued with directors like Hepworth and his stop motion effects and Porter with his continuity editing. This need to continuously beat your competition became the driving force behind countless cinematic innovations.

https://www.tumblr.com/qu-film-history-to-1968/727734263799316480/adaptation-is-needed-in-the-film-industry-the?source=share

One of the biggest problems that all of these filmmakers had was the difficulty of showing these films to the general public. There were numerous issues surrounding this, including but not limited to the high cost of attending screenings, the lack of easily accessible places to screen, and the fact that many of the screening methods were limited to one viewer at a time. But, when the Nickelodeon became commonplace, the vast majority of these problems were resolved, and our movie theaters today are direct descendants of these revolutionary buildings. This was mainly because, as Huhtamo writes, the screen becomes “a surface for collective viewing, although this by no means excludes the possibility of individual spectatorship.”

https://www.tumblr.com/qu-film-history-to-1968/727749972349648896/the-cultural-history-of-television?source=share

Take, for example, the famous opening of Scream 2. The first “Stab” movie is being shown, and Jada Pinkett Smith’s character is terrified by what she’s seeing on screen while the vast majority of the audience is excited by and even seem to be rooting for the masked killer. Of course, we find out pretty quickly that Smith’s character is having the proper reaction to this situation once she herself gets stabbed, but this intro is a great example of what Huhtamo describes when talking about viewing movies on a screen. The crowd is feeding into one another, the more one person cheers, the more everyone else cheers, until the screening becomes a cacophony of hoots and hollars as more and more blood is spilled. But that doesn’t stop Smith’s character from having her own terrified reaction to what’s occurring on the screen.

https://youtu.be/fnTckzsYgg0?si=6xq3Ng7DKL6ZdEgE

All of this can be traced back to the beginning. So, no matter how long ago their works were, no matter how outdated their actions, Edison, the Lumières, Méliès, and everyone else who helped make cinema what it is today will always be relevant. -Haley Ruccio

Huhtamo, Von Erkki. “Screenology; or, Media Archaeology of the Screen.” The Screen Media Reader, 2017.

Cook, D. A. and Sklar, . Robert. "History of Film." Encyclopedia Britannica, August 18, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/art/history-of-the-motion-picture.

Moss, Yelizaveta, and Candice Wilson. “Film Appreciation.” OpenALG. Accessed September 8, 2023. https://alg.manifoldapp.org/read/film-appreciation/section/2a69a38b-dfac-4dd1-91f5-e52f768efbd0.

0 notes