#Byzantine history

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A Byzantine Gold Collier with Emeralds, Sapphires, Amethysts and Pearls, from a workshop in Constantinople (late 6th-7th Century AD).

#byzantine history#byzantine art#byzantine#gold jewelry#antique jewelry#antique#gold#gold necklace#necklace#constantinople#toya's tales#style#toyastales#toyas tales#fashion#art#clothing#november#fall#artifact#antiquities#art history#jewelry#jewellery#jewelry history#world history#emeralds#amythest#sapphire#pearls

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Shout out to Porphyrios, the whale who terrorized the waters near Constantinople for more than 50 years during the 6th century.

You'd sunk more Roman warships than most of their human enemies.

#roman history#byzantine history#roman empire#byzantine empire#new roman empire#eastern roman empire#constantinople#rome#history#porphyrios

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

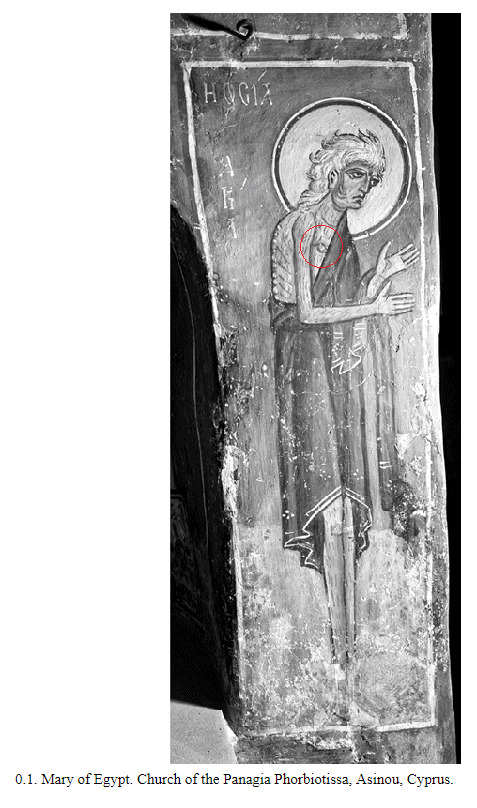

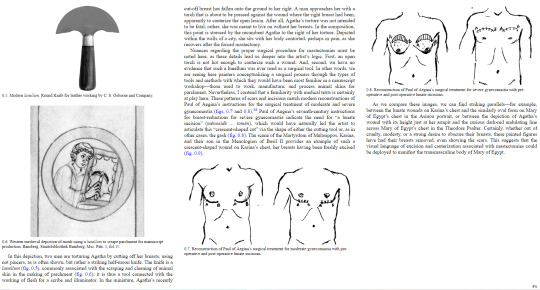

I started reading Roland Betancourt's Byzantine Intersectionality because it has a chapter on transwomen, but it turns out that the book is heavily focused on transmasculinity and race in the Byzantine world.

Specifically I wanted to show you this discussion on artistic representation of top surgery and the likelihood that this actually represents top surgery.

Anyway this is really fucking cool

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Byzantine Gold Necklace with Amethyst Beads Byzantine, 6th century A.D. Gold and Amethyst

#Byzantine Gold Necklace with Amethyst Beads#Byzantine#6th century A.D.#gold and amethyst#jewelry#ancient jewelry#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#byzantine history#byzantine empire#eastern roman empire#byzantine art#ancient art#byzantine jewelry

648 notes

·

View notes

Text

Common Modern Greek phrases with Byzantine origins

"Παίζω στα δάχτυλα" (Pézo sta ðákhtyla) = I am very good at knowing something, I have learned it very well. Literally, I can play (sth) on my fingers. Children in the Eastern Roman Empire learned the basics of arithmetic by counting with their fingers, a practice still used in the old years of the modern Greek school.

"Ο ήλιος βασίλεψε" (O ílios vasílepse) = the sun set, literally "the sun reigned" It might seem counter-intuitive, however in Greek when you say "the sun reigns" or "sun-reigning" (ηλιοβασίλεμα), it is not about the sun being high in the sky but it is instead used for the sunset, the early evening. This is because of the striking colours of the sunset; gold, orange, red, purple - the luxurious colours associated with the Byzantine emperors.

"Ἐφαγα τον περίδρομο" (Éphagha ton períðromo)= I ate too much, I ate everything on sight. Literally, I ate the "peridromos". The peridromos was the edge of a deep bowl in which the Byzantines ate soup, so when they filled their bowl up to the peridromos it meant they were eating a lot. The interesting thing is that the origin of this phrase is very little known to modern Greeks and because peridromos can also have other meanings, there are also other interpretations that however make too little sense (IMO). This alone could perhaps be proof of how the phrase survived organically amongst the people even after the fall of the Byzantine empire (and its bowls).

"Μη με παιδεύεις" (Mi me peðévis) = don't bother / torment / trouble me, etymologically deriving from the word for "child". In Ancient Greek, the child was παις and its derivative verb παιδεύω meant "educate", an action interwined with childhood. Progressively, however, the verb became more and more associated with the pains and struggles of being educated until by Byzantine / Medieval Greek's time it had the meaning of "bother / torment". In Modern Greek the verb παιδεύω has kept the Byzantine meaning of tormenting / bothering but its respective noun παιδεία (peðía) still retains the ancient meaning of education or more accurately the full transformative period of learning in a young person's life. There are however other also ancient derivatives from the same words that are more precisely used for education terminology.

"Ἠμαρτον!" (Ímarton) = an exclamation in the likes of "I have sinned! (Forgive me)") Ancient Greek did not have a word for the sin. The verb αμαρτάνω (amartáno), whose form above is the past tense, meant "I miss the target / I make a mistake". In ancient Greek they would say it for example when an archer did not hit the target. By Byzantine times, however, the word had acquired a more figurative, Christian theological meaning because one's ultimate goal was the virtuous living, so when they did something bad or wrong, it was perceived as "losing sight of their aim, their intent". And that's how the word developed into meaning "sin" in Medieval and Modern Greek.

Source: Byzantinist historian Helene Ahrweiler

#greek#greece#greek language#history#languages#language stuff#linguistics#greek history#byzantine history#eastern roman empire#byzantine empire#greek culture

210 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nativity of Christ, Menologion of Basil II, Constantinople, c. 1000.

#byzantine#byzantine history#byzantine art#byzantine empire#greek orthodox#greek orthodox church#christianity#roman#roman art#roman empire#roman history#nativity#miniature painting#illuminated manuscript#medieval#middle ages#medieval history#medieval art

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

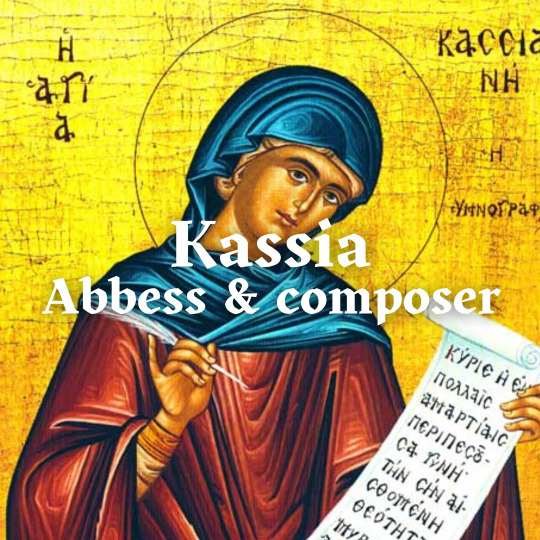

Abbess, composer, poet, philosopher: Kassia (c.810–c.865) was a multi-talented woman and one of the most prominent female voices in the Byzantine world.

The outspoken candidate

Kassia was born into an aristocratic family; her father, a military official (Kandidatos) at the imperial court, ensured she received an exceptional education. In a society where women had a relatively high literacy rate, Kassia’s intellect and skills stood out. As a teenager, she earned praise from Theodore the Studite, who wrote:

"While you have not surpassed those of old, of whose wisdom and education we in this generation, both men and women, fall far short—and immeasurably so—you have done so with regard to those of the present, since the fair form of your discourse has far more beauty than a mere specious prettiness"

From a young age, Kassia demonstrated her piety and strong personality. She supported a monk imprisoned by the Iconoclast authorities and likely began contemplating a monastic life early on.

She participated in a bride show at the palace, where the young Emperor Theophilos sought to choose his empress. Theophilos reportedly remarked to her, "From woman come evils," referencing Eve’s sin. Kassia, undeterred, replied, "But from woman sprang many blessings," alluding to the Virgin Mary.

Kassia was not chosen. Her poem On Stupidity may reflect her thoughts on the encounter:

It is terrible for a stupid person to possess some knowledge;

and if he has an opinion, it’s even worse;

but if a stupid man is young and in a position of power,

alas and woe and what a disaster.

Woe, O Lord, if a stupid person attempts to be clever;

where does one flee, where does one turn, how does one endure?

The abbess

After this experience, Kassia was reportedly delighted to pursue her true calling as a nun. She founded her own monastery in Constantinople, where she served as abbess.

Life in a women’s monastery offered significant opportunities. Nuns held all key offices within the monastery, and the abbess wielded complete authority. She carried a staff like her male counterparts, sat on a throne during church services, and could even preach. In some cases, abbesses were respected as spiritual authorities for men as well as women.

Kassia’s writings during this time reveal a vivid personality. She was outspoken and direct, with little tolerance for hypocrisy or falsehood. At times, she came across as impatient or acerbic, but her works also show a sensitive, compassionate side and an emphasis on genuine friendships.

The artist

Kassia dedicated her days to “philosophizing,” writing epigrams and composing gnomic poetry. However, she is best remembered for her liturgical hymns. As one of the few female hymnographers in Byzantine history (alongside contemporaries like Theodosia and Thekla), Kassia is the only woman whose works were incorporated into the official Byzantine hymnals, which remain in use today. The 14th-century writer Nikephoros Kallistos Xanthopoulos ranked her eleventh on his list of the most influential composers.

Kassia’s writings often highlighted the contributions and courage of women. She rejected stereotypes of female weakness and submission, as reflected in this poem:

I hate silence, when it is a time for speaking.

I hate the one who conforms to all ways.

She even hinted at the idea of female superiority in her poem Woman:

Esdras is witness that women

Together with truth prevail over all.

Today, Kassia is venerated as a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church, with her likeness depicted in icons. Her feast day is celebrated on September 7, and her most famous hymn is still chanted during the liturgy for Holy Wednesday each year.

youtube

Enjoyed this post? You can support me on Ko-fi!

Further reading:

Herrin Judith, “Changing functions of monasteries for women during Byzantine iconoclasm”, in: Garland Lynda (ed.), Byzantine Women, Varieties of Experience 800-1200

Sherry Kurt, Kassia the Nun in context: The Religious Thought of a Ninth-Century Byzantine Monastic

#kassia#history#women in history#women's history#historyedit#9th century#byzantine history#byzantine empire#female authors#female composers#feminism#middle ages#medieval women#medieval history

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Melicuccà, Calabria, Italy

There is little information about the historical origins of Melicuccà, a small town located in a valley formed by the northern slopes of Aspromonte mountains. In the territory of the municipality, the caves of S. Elia speleota, with the remains of the adjacent Basilian monastery and the annexed factories, dating back to the 10th century, today represents one of the most conspicuous archaeological testimonies of Byzantine Greece in southern Calabria. The origins of the town can perhaps be traced precisely in the very high density of Basilian settlements existing in the Byzantine era on this territory. The biographies of the Italian-Greek Saints speak of a commercial center (emporion), named Sicri, which today is just an uninhabited district near Melicuccà (Sìcari). From Sicri, perhaps destroyed by the Saracens during the raids of the emir Hasan 950-52, the refugees who escaped the massacre probably moved to the valley of Melicuccà, where the hackberry grew (in Greek melikokkos) and where abundant springs flowed, increasing the pre-existing agro-pastoral settlement and thus giving rise to the first substantial inhabited nucleus of the village. A clue to this transfer can be found in the bios of the Speleota, where it is said of populations who, fleeing the Saracens, flocked towards the cave of the Saint.

Follow us on Instagram, @calabria_mediterranea

#melicuccà#calabria#italy#italia#south italy#southern italy#mediterranean#decay#cave#byzantine#history#byzantine history#byzantine empire#greek#italian#europe#landscape#italian landscape#landscapes#italian landscapes

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leo the wise was a Roman Emperor who's life came straight out of a Sims playthrough.

His 'father' was a peasent wrestler named Basil who came to the attention of the very drunk and very bisexual Roman Emperor Michael. Michael was so enamored with Basil I that he made him his co-emperor! Michael also had a mistress named Eudokia! Michael got a lot of heat for seeing his mistress by the church so he forced Basil to marry her to make it easier for him to see her.

Around this time Eudokia got pregnant and gave birth to Leo, Basil NEVER thought Leo was his son and was Michael's bastard.

One day Basil killed Michael while he was in the bath and became Emperor! He had a really good rule as an emperor, among the best! His first born son Constantine from a previous marriage was meant to succeed him but alas the boy died! Basil was super pissed about this, not just because he lost his son, but that meant Leo was next in line and has been established Basil was certain Leo was not his!

This would be cause of great problems for Basil until one day during a hunting trip his belt got wrapped around the deer he'd been hunting. The deer proceeded to drag him 16 miles through the forrest at full gallop culminating in his death. It was rumored Leo was responsible somehow.

Now Emperor Leo was ready to have his first son with his wife! Uh-oh! She died from a fever! So Leo decided to marry again! Uh-oh! She died too! Leo incredibly upset wanted to get married a third time but the Orthodox Church was against re marriage and just barely let Leo do it previously. Getting into a qurrel with the Patriarch of Constantinople he was allowed to marry a third time.

Oh no! His third wife died in childbirth along with the baby! He tried to get married a fourth time to which the Patriarch said 'no fucking way! This is polygamy!' and Leo decided 'how 'bout I do anyway' and proceeded to get married again and firing the current Patriarch and getting a new one! Fourth time was the charm and he finally got a son and heir!

Aside from his colorful family history, Leo the Wise was known for being an academic philosopher king, he was a bookworm, and one of the more learned rulers in history! He never stepped onto a battlefield nor did he go out on campaign, though he wrote the Tactica, a military science manuel for generals in the Empire used for generations after his death. He also contributed greatly to Roman law by finishing his 'father's' work ' The Basilika' that simplified, better organized, and added to 'Justinian's Code.'

#ooc#roman history#byzantine history#leo the wise#if u follow other blogs of mine u likely saw this post earlier#but it felt more fitting over here so i deleted and remade it

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Don’t know anyone like them out there but I’m postin anyways

Belisarius and Mundus protecting Justinian in Nika Roit!

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Women’s History Meme || Empresses (5/5) ↬ Zoe Porphyrogénnētē (c. 978 – 1050)

When Michael V met his fate on Tuesday evening, 20 April 1042, the Empress Theodora was still in St Sophia. She had by now been there for well over twenty-four hours, steadfastly refusing to proceed to the Palace until she received word from her sister. Only the following morning did Zoe, swallowing her pride, send the long-awaited invitation. On Theodora's arrival, before a large concourse of nobles and senators, the two old ladies marked their reconciliation with a somewhat chilly embrace and settled down, improbably enough, to govern the Roman Empire. All members of the former Emperor's family, together with a few of his most enthusiastic supporters, were banished; but the vast majority of those in senior positions, both civil and military, were confirmed in office. From the outset Zoe, as the elder of the two, was accorded precedence. When they sat in state, her throne was placed slightly in advance of that of Theodora, who had always been of a more retiring disposition and who seemed perfectly content with her inferior status. Psellus gives us a lively description of the pair: Zoe was the quicker to understand ideas, but the slower to give them utterance. With Theodora it was just the reverse: she concealed her inmost thoughts, but once she had embarked on a conversation she would chatter away with an informed and lively tongue. Zoe was a woman of passionate interests, prepared with equal enthusiasm for life or death. In this she reminded me of the waves of the sea, now lifting a vessel on high, now plunging it down again. Such extremes were not to be found in Theodora: she had a calm disposition - one might almost say a dull one. Zoe was prodigal, the sort of woman who could dispose of a whole ocean of gold dust in a single day; the other counted her coins when she gave away money, partly no doubt because all her life her limited resources had prevented her from any reckless spending, but partly also because she was naturally more self-controlled In personal appearance there was a still greater divergence. The elder, though not particularly tall, was distinctly plump. She had large eyes set wide apart, with imposing eyebrows. Her nose was inclined to be aquiline, though not overmuch. She still had golden hair, and her whole body shone with the whiteness of her skin. There were few signs of age in her appearance … there were no wrinkles, her skin being everywhere smooth and taut. Theodora was taller and thinner. Her head was disproportionately small. She was, as I have said, readier with her tongue than Zoe, and quicker in her movements. There was nothing stem in her glance: on the contrary she was cheerful and smiling, eager to find any opportunity for talk. — Byzantium: The Apogee by John Julius Norwich

#women's history meme#zoe porphyrogenita#byzantine history#medieval#greek history#asian history#european history#women's history#history#nanshe's graphics

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Famous byzantine empresses drawn by Sato Futaba, author of the historical mangas "Utae, Erinna!" and "Anna Komnene":

Aelia Eudocia (401-460 AD) was the wife of emperor Theodosius II and a great poetess whose works are great examples of how her Christian faith and Greek heritage and upbringing were intertwined, exemplifying a legacy that the Roman empire left behind on the Christian world.

Theodora (c. 490/500-548 AD) was the wife of emperor Justinian I the Great. She was of humble origins and one of her husband's chief advisers.

Martina (date of birth unknwon- died after 641 AD) was the wife and niece of emperor Heraclius.

Irene of Athens (750/756-803 AD) was the wife of emperor Leo IV from 775 to 780, regent for her son Constantine VI from 780 until 790, co-ruler from 792 until 797, and finally sole ruler of the Eastern Roman empire from 797 to 802.

#byzantine#byzantine empire#byzantine history#historical art#historical people#Aelia Eudocia#Theodora#Martina#Irene of Athens#manga#Sato Futaba#women in history#women’s history#women at work#empress

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Very fond of the new trend of calling the Later Eastern Roman Empire AKA the "Byzantine" Empire the New Roman Empire.

It differentiates it enough from the classical Roman Empire centered on Rome itself without denying its "romanness".

Also, the original name of Constantinople was Nova Roma (lit. New Rome) so its fitting to call the Roman Empire centered around the city the New Roman Empire.

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Empresses-in-Waiting comprises case studies of late antique empresses, female members of imperial dynasties, and female members of the highest nobility of the late Roman empire, ranging from the fourth to the seventh centuries AD. Situated in the context of the broader developments of scholarship on late antique and byzantine empresses, this volume explores the political agency, religious authority, and influence of imperial and near-imperial women within the Late Roman imperial court, which is understood as a complex spatial, social, and cultural system, the centre of patronage networks, and an arena for elite competition."

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dozens of Amphorae Recovered From Ancient Byzantine Shipwreck in Greece

Excavations of an ancient Byzantine shipwreck off the coast of Fournoi near Samos, Greece are bringing new finds onto the surface.

The wreck has been systematically excavated since 2021 and has been selected for intensive investigation due to the extremely interesting cargo it carries.

The amphorae found recently in the sand near the wreck, along with the wooden skeleton of the ship itself, were in remarkably good condition. Experts believe that the ship’s wooden framing survived throughout the centuries because it was crushed under the rest of the ship and oxygen couldn’t reach it, stalling the process of decay.

So far eight different amphora types have been recorded, originating from Crimea, Sinope of the Pontus region in the Black Sea, as well as from the Aegean islands and the Phocaean region of Asia Minor.

Pottery recovered at the ancient Byzantine shipwreck

The Ministry of Culture said that 170 group dives were carried out during the latest excavations. Archaeologists worked throughout the period to clear sand and debris from the wreck to provide access for experts to conduct studies of the site.

The scattering of the finds on the seabed seems to indicate a partial loss of cargo before the ship sank.

The recovered pottery was particularly enlightening, in terms of the more precise chronological inclusion of the wreck, which can now be safely dated between 480 and 520 AD, probably during the years of Emperor Anastasios I (491 – 518 AD), said a press release by the Greek Ministry of Culture.

Byzantine Emperor Anastasios I is known for his fiscal and monetary reforms, which strengthened the Empire’s coffers and enabled the expansionist policy of the emperors of the 6th century.

In parallel with the excavation of the wreck, findings from three more wrecks at the Fournoi archipelago were recovered, which are intended to be exhibited at the local archeological museum. Among these finds are a giant archaic anchor obelisk and amphorae from shipwrecks of the 6th to 8th centuries AD.

Countless ancient shipwrecks off Greece

There are many ancient shipwrecks across the Greek seas, and archaeologists have found countless historic treasures in these sunken archaeological sites.

In March 2024, the Ministry of Culture announced that scientists have discovered several shipwrecks and other important ancient finds in the underwater, near Greece’s island of Kasos.

These date back indicatively from prehistory (3000 BC), the Classical period (460 BC), the Hellenistic (100 BC to 100 AD), and the Roman years (200 BC – 300 AD) to the medieval and Ottoman periods.

Four stunning ancient shipwrecks filled with artifacts from antiquity and the Roman and Byzantine eras off central Greece can now be explored by amateur divers.

“We plan to highlight our marine cultural heritage,” Culture Minister Lina Mendoni said.

“We have responded to this great challenge by opening to the public a total of four underwater archaeological sites in the prefecture of Magnesia, which will allow Greece to join the world map of diving tourism.”

By Tasos Kokkinidis.

#Dozens of Amphorae Recovered From Ancient Byzantine Shipwreck in Greece#coast of Fournoi#ancient shipwreck#ancient amphorae#ancient artifacts#archeology#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient greece#greek history#byzantine history#byzantine empire

75 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In the Castle City of Mystrás

Mystrás was the capital city of the Despotate of Morea (1262 - 1460), the last Byzantine stronghold against the Franks and the Ottoman Turks. The sons of the Byzantine emperors served in the region as déspotes but in a few occasions the emperors would also be crowned there. Morea eventually fell to the Ottoman Empire seven years after Constantinople (1460). It remained inhabited until 1825 when it was attacked by the Egyptian army under the command of Ibrahim Pasha during the Greek War of Independence. Until then, western explorers often mistook Mystras for Ancient Sparta. In truth, Mystras is overlooking the ruins of Ancient Sparta and the modern city of Sparta is built 8km to the east.

Photos from Wikimedia Commons.

#greece#europe#history#byzantine history#greek history#byzantine empire#byzantine culture#greek culture#christian orthodoxy#architecture#mystras#laconia#peloponnese#peloponnisos#mainland#sparta

99 notes

·

View notes