#byzantine art

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Gold earrings, Byzantine, 7th century

from The Benaki Museum, Athens

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Byzantine Gold Collier with Emeralds, Sapphires, Amethysts and Pearls, from a workshop in Constantinople (late 6th-7th Century AD).

#byzantine history#byzantine art#byzantine#gold jewelry#antique jewelry#antique#gold#gold necklace#necklace#constantinople#toya's tales#style#toyastales#toyas tales#fashion#art#clothing#november#fall#artifact#antiquities#art history#jewelry#jewellery#jewelry history#world history#emeralds#amythest#sapphire#pearls

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Jacob wrestling with the Angel, byzantine bronze door, Monte Sant'Angelo, ca. 1070

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

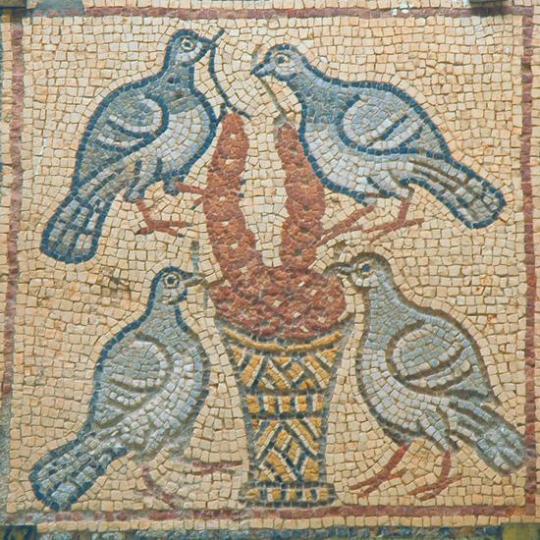

birds from the Theodorias, East Church mosaics in the Qasr Libya museum, ca. 540 CE, via livius.org.

#mosaics#byzantine art#also one uhm. large lizard. there's also a lizard#on which that duck is standing#libya#north africa

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Byzantine Gold Necklace with Amethyst Beads Byzantine, 6th century A.D. Gold and Amethyst

#Byzantine Gold Necklace with Amethyst Beads#Byzantine#6th century A.D.#gold and amethyst#jewelry#ancient jewelry#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#byzantine history#byzantine empire#eastern roman empire#byzantine art#ancient art#byzantine jewelry

568 notes

·

View notes

Text

⚜️ the hughes saga ⚜️

explanation below!

in the first drawing quinn is portrayed as a saint, which are regarded as the closest thing a normal human can be to holy. i think the canucks fanbase and the nhl in general definitely see quinn in a similar lens. saints are also usually figures of guidance (captain!), wonder workers (self explanatory), and martyrs/bearers of heavy burdens (he's carrying fr 😭). the tear of blood is a nod to the statues of mary that cry blood, which are taken as an indication that repentance is needed. i figured that would be appropriate given the state of our team right now (😞).

jack is portrayed with the devil behind him like he's a pawn being steered by the devil, but a lot of people misconstrued the visual and thought the horns were HIS, thus him being the devil. i am actually obsessed with this and how the narrative is just writing itself here. there's a lot to be said about public perception when it comes to jack, and i feel like somehow this captured that.

luke!! luke's idea was not the original plan funnily enough. i just want to reiterate that he is NOT meant to be jesus but i really like the lamb of god imagery. The lamb being born with a specific purpose as an agent of god felt like the best representation for someone who is the youngest in a long legacy of hockey. born into expectation, destined for something big from the get-go. also attributes like purity and obedience. yeh. (also i am a third sibling projecting)

i am potentially out of my element here but i really enjoyed making these and reading and planning all the details!! rlly fond of this style so expect many others to come.

also! there's an homage to jack and quinn in luke's drawing! see if u can find it :3

#art#ween art#artists on tumblr#portrait#digital art#quinn hughes#jack hughes#luke hughes#hughes brothers#hughes bowl#jh86#qh43#lh43#nj devils#new jersey devils#canucks#vancouver canucks#nhl#hockey#nhl fanart#hockey fanart#hockey players#canucks hockey#devils hockey#byzantine#byzantine art

182 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lakewood Cemetery Chapel, domed ceiling

Minneapolis

#lakewood cemetery#byzantine art#mosaic#lensblr#imiging#photographers on tumblr#original photographers#luxlit#isu#minneapolis#convex concave

162 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sardonyx cameo by an unknown Byzantine artist of the 14th century, depicting St. Theodore Stratelates ("Army Commander"). Theodore (281-319) was a Roman soldier, said to have been martyred during the persecution of Christians by the emperor Licinius. Here, Theodore is shown in full military dress, a spear in his right hand and a round shield on his left shoulder. The accompanying inscription invokes him and his namesake, Theodore "the Recruit," as protectors; the cameo would likely have been suspended from a chain and wore around the neck as a protective amulet.

Now in the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. Photo credit: Walters Art Museum.

#art#art history#Byzantine#Byzantine Empire#Byzantine art#Byzantium#medieval#medieval art#Middle Ages#Eastern Orthodox#Orthodox Christianity#jewelry#jewellery#cameo#sardonyx#Walters Art Museum

261 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unknown Artist Triptych showing the Forty Martyrs

Ivory and silver, 18.5×24.2 cm, late 11th - early 12th century

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

#MetalMonday:

Lamp in the Shape of a Rooster

Early Byzantine (Egypt?), 6th-7th c.

Bronze, cast & chased, 11 x 13.5 cm (4 5/16 x 5 5/16 in.)

On display at Dumbarton Oaks

“The rooster is a rare shape and may not have any references beyond its similarity in shape to the peacock and its associations with sunrise - the start of daylight.”

More info:

“Lamps are among the most widely used & imaginatively conceived works in antiquity. They were made predominantly in terracotta, but many examples in bronze survive because of their durability. Artists drew inspiration from all aspects of ancient culture, from the mythological realm, illustrated by a lamp with a griffin-head handle in the Dumbarton Oaks collection (BZ.1962.15), to the natural world, reflected in this rooster lamp. Identified by its distinctive coxcomb & wattles, the head is tipped forward at an angle that is typical of this barnyard bird. The feathers on the body are chased (i.e. incised after the lamp was cast).

The rooster, or cock, is proverbially the harbinger of the new day. This connection with dawn and daylight may have been the inspiration for crafting the lamp. One mention occurs in the New Testament when Christ tells Peter that he will deny him three times before the cock crows (Matthew 26:34). It is more likely the former connection than the Biblical reference inspired the rooster of this lamp.”

info via http://museum.doaks.org/objects-1/info/27342

#animals in art#museum visit#bird#birds in art#rooster#Byzantine art#ancient art#Dumbarton Oaks#metalwork#bronze#lamp#domesticated animals in art#Metal Monday

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gold earrings with glass beads, pearls, and sapphires, Byzantine, 5th-6th century AD

from The Benaki Museum, Athens

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

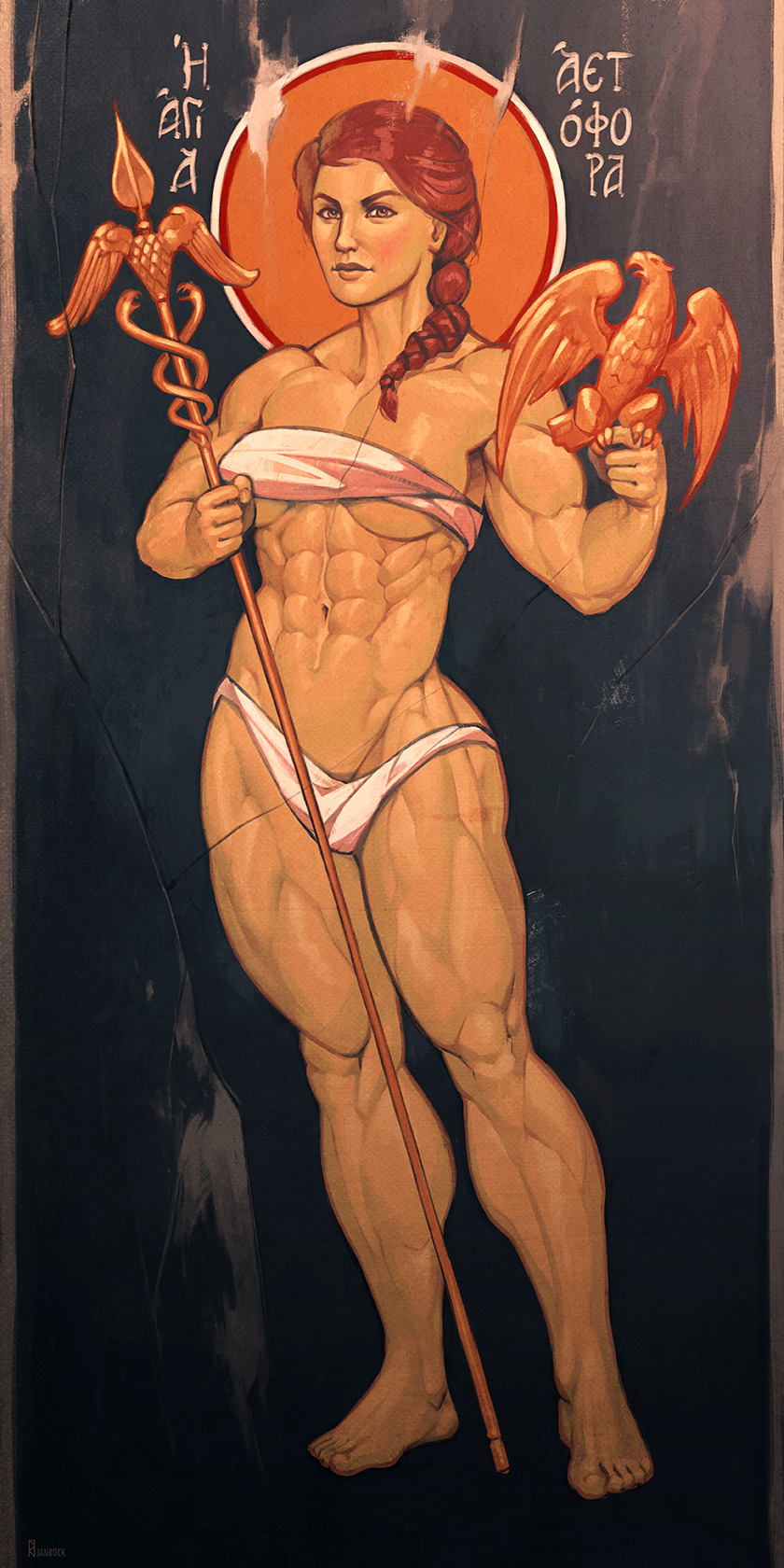

Saint Kassandra Aetophora

571 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dragon

In this panel, Saint Margaret is being swallowed by a dragon and then miraculously bursting out of its stomach. This story led to Margaret becoming the patron saint of childbirth

by Margarito d'Arezzo

#found#art#london#byzantine#Byzantine art#dragons#dragon#saint Margaret#patron saint#patron saint of childbirth#Margarito d'Arezzo#Tuscan art#Tuscany#religious art#christian art#icons

293 notes

·

View notes

Text

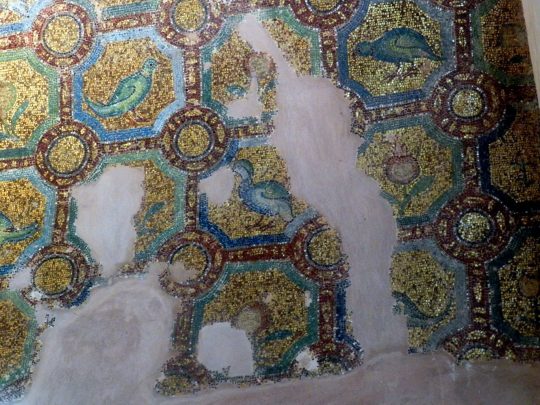

bird details from the incredible Byzantine Wall Mosaic in the Rotunda of St. George, Thessaloniki. photo source links in the pictures for the ones from twitter, the others by Helen Miles

#mosaic#Byzantium#byzantine art#this is sooo beautiful and i never heard of it! also yes i think that last one probably depicts a parrot despite the shape. not a lot of#green birds with neck bands around in this general area even if the beak shape is way off. well idk#thessaloniki

770 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rare Portrait of the Last Byzantine Emperor Discovered in Greece

The image of Constantine XI Palaiologos was probably painted from life.

A portrait of the final Byzantine emperor, Constantine XI Palailogos, has been discovered by archaeologists in Greece. The portrait was found on a mid-15th century fresco uncovered at a monastery in Aigialeia in the Achaea region of Western Greece.

Constantine XI Palaiologos ruled the Byzantine Empire for a short period between January 6, 1449 and May 29, 1453, dying in battle during the fall of Constantinople, when the capital was captured by the Ottomans. The Byzantine Empire had been steadily losing land since the 7th century and vanished entirely after the battle in 1453. The painting is the last known portrait of any Byzantine emperor created during their reign.

In the portrait, the emperor appears wearing regalia adorned with crowned double-headed eagles. These were symbols of the Palaiologos dynasty, which was the longest-ruling of the Byzantine Empire. It produced emperors and leaders for just shy of 200 years, between the 13th and 15th centuries.

He is also wearing a bejeweled crown and holding a cruciform scepter. His purple cloak would have been dyed from the liquid produced from the glands of the Bolinus brandaris sea snail, which was incredibly expensive and so was reserved for use only by royalty (said to be “born in purple”) during the Byzantine Empire. Following the fall of Constantinople, the harvesting farms of the snails were destroyed by the Ottoman Turks, but the association of purple with royalty lives on.

The fresco is believed to be the work of an artist from Mystras, a town south of the Aigialeian monastery, where a young Constantine lived and ruled for five years before his ascension to emperor. The Holy Monastery of Pammegiston Taxiarchon had once been the recipient of significant financial donations from Constantine’s brothers. It was during recent restoration of the monastery that the fresco containing the portrait of the Byzantine emperor was discovered.

The Greek Minister for Culture, Lina Mendoni, called the portrait “the only known depiction” of Constantine XI Palaiologos “created during his lifetime.” His short rule meant that few portraits of him have been discovered. Mendoni added that “the artist likely painted the emperor’s features from direct observation, rather than relying on an official imperial portrait, as was customary.”

In a statement, the Greek Ministry of Culture referenced the “authenticity” of the portrait, which “accurately renders the physiognomic features of the last Byzantine emperor.” It describes the likeness, calling the portrait a depiction of “an earthly figure, a mature man, with a delicate face and individualized features, who exudes calm and nobility.”

By Verity Babbs.

#Rare Portrait of the Last Byzantine Emperor Discovered in Greece#Constantine XI Palaiologos#painting#fresco#the Old Monastery of the Archangels#art#artist#art work#art world#art news#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#byzantine empire#byzantine art#ancient art

48 notes

·

View notes