#Black Pastors

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

White lynch mobs in America murdered at least 4,467 people between 1883 and 1941, hanging, burning, dismembering, garroting and blowtorching their victims.

Their violence was widespread but not indiscriminate: About 3,300 of the lynched were black, according to the most recent count by sociologists Charles Seguin and David Rigby. The remaining dead were white, Mexican, of Mexican descent, Native American, Chinese or Japanese.

Such numbers, based on verifiable newspaper reports, represent a minimum. The full human toll of racial lynching may remain ever beyond reach.

Religion was no barrier for these white murderers, as I’ve discovered in my research on Christianity and lynch mobs in the Reconstruction-era South. White preachers incited racial violence, joined the Ku Klux Klan and lynched black people.

Sometimes, the victim was a pastor.

Buttressing white supremacy

When considering American racial terror, the first question to answer is not how a lynch mob could kill a man of the cloth but why white lynch mobs killed at all.

The typical answer from Southern apologists was that only black men who raped white women were targeted. In this view, lynching was “popular justice” – the response of an aggrieved community to a heinous crime. A white lynch mob in Shelbyville, Tennessee, in 1941. Bettmann via Getty

Journalists like Ida B. Wells and early sociologists like Monroe Work saw through that smokescreen, finding that only about 20% to 25% of lynching victims were alleged rapists. About 3% were women. Some were children.

Black people were lynched for murder or assault, or on suspicion that they committed those crimes. They could also be lynched for looking at a white woman or for bumping the shoulder of a white woman. Some were killed for being near or related to someone accused of the aforementioned offenses.

Identifying the dead is supremely difficult work. As sociologists Amy Kate Bailey and Stewart Tolnay argue persuasively in their 2015 book “Lynched,” very little is known about lynching victims beyond their gender and race.

But by cross-referencing news reports with census data, scholars and civil rights organizations are uncovering more details.

One might expect that mobs seeking to destabilize the black community would focus on the successful and the influential – people like preachers or prominent business owners.

Instead, lynching disproportionately targeted lower-status black people – individuals society would not protect, like the agricultural worker Sam Hose of Georgia and men like Henry Smith, a Texas handyman accused of raping and killing a three-year-old girl. The National Memorial For Peace And Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, commemorates the victims of lynching. Bob Miller/Getty Images

The rope and the pyre snuffed out primarily the socially marginal: the unemployed, the unmarried, the precarious – often not the prominent – who expressed any discontentment with racial caste.

That’s because lynching was a form of social control. By killing workers with few connections who could be economically replaced – and doing so in brutal, public ways that struck terror into black communities – lynching kept white supremacy on track.

Fight from the front lines

So black ministers weren’t often lynching victims, but they could be targeted if they got in the way.

I.T. Burgess, a preacher in Putnam County, Florida, was hanged in 1894 after being accused of planning to instigate a revolt, according to a May 30, 1894, story in the Atlanta Constitution newspaper. Later that year, in December, the Constitution also reported, Lucius Turner, a preacher near West Point, Georgia, was shot by two brothers for apparently writing an insulting note to their sister.

Ida B. Wells wrote in her 1895 editorial “A Red Record” about Reverend King, a minister in Paris, Texas, who was beaten with a Winchester Rifle and placed on a train out of town. His offense, he said, was being the only person in Lamar County to speak against the horrific 1893 lynching of the handyman Henry Smith.

In each of these cases, the victim’s profession was ancillary to their lynching. But preaching was not incidental to black pastors’ resistance to lynching.

My dissertation research shows black pastors across the U.S. spoke out against racial violence during its worst period, despite the clear danger that it put them in. Ida B. Wells, the great documentarian of the lynching era, in 1920. Chicago History Museum/Getty Images

Many, like the Washington, D.C., Presbyterian pastor Francis Grimke, preached to their congregations about racial violence. Grimke argued for comprehensive anti-racist education as a way to undermine the narratives that led to lynching.

Other pastors wrote furiously about anti-black violence.

Charles Price Jones, the founder of the Church of God (Holiness) in Mississippi, for example, wrote poetry affirming the African heritage of black Americans. Sutton Griggs, a black Baptist pastor from Texas, wrote novels that were, in reality, thinly veiled political treatises. Pastors wrote articles against lynching in their own denominational newspapers.

By any means necessary

Some white pastors decried racial terror, too. But others used the pulpit to instigate violence.

On June 21, 1903, the white pastor of Olivet Presbyterian church in Delaware used his religious leadership to incite a lynching.

Preaching to a crowd of 3,000 gathered in downtown Wilmington, Reverend Robert A. Elwood urged the jury in the trial of George White – a black farm laborer accused of raping and killing a 17-year-old white girl, Helen Bishop – to pronounce White guilty speedily.

Otherwise, Elwood continued, according to a June 23, 1903 New York Times article, White should be lynched. He cited the Biblical text 1 Corinthians 5:13, which orders Christians to “expel the wicked person from among you.”

“The responsibility for lynching would be yours for delaying the execution of the law,” Elwood thundered, exhorting the jury.

George White was dragged out of jail the next day, bound and burned alive in front of 2,000 people.

The following Sunday, a black pastor named Montrose W. Thornton discussed the week’s barbarities with his own congregation in Wilmington. He urged self-defense.

“There is but one part left for the persecuted negro when charged with crime and when innocent. Be a law unto yourself,” he told his parishioners. “Die in your tracks, perhaps drinking the blood of your pursuer.”

Newspapers around the country denounced both sermons. An editorial in the Washington Star said both pastors had “contributed to the worst passions of the mob.”

By inciting lynching and advocating for self defense, the editors judged, Elwood and Thornton had “brought the pulpit into disrepute.”

#Black churches resist white supemacists#Black Pastors#white supemacy#white hate#Lynching preachers: How black pastors resisted Jim Crow and white pastors incited racial violence#Black church

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

Will go down in infamy

#student activism#Palestine solidarity#Columbia University#Gaza genocide#faculty#unions#black pastors#administration#repression#censorship#militarized police#brutality#violence#revolution#Biden#denunciation#complicity

0 notes

Text

Support me on Patreon or send a tip on Kofi!

Prints avail on Redbubble!

(ID in alt and under cut)

ID: Full body art nouveau style portrait of a fat black woman in a sheer white bandeau dress sitting on the branch of a massive tree. A smaller leaf heavy branch extends above her, laden with ripe bundles of oranges. Smiling serenely, the woman leans back on one hand and reaches up with the other to cradle an orange in her palm. Her long, thick, coiled black hair tumbles out behind her and drapes itself across the branch she is seated on, backlit by glowing sunlight that shines through the innermost branches above. Behind the image is the blue of a summer sky, surrounded by a circular rainbow border wrapped in green vines. /end ID

#art#art nouveau#pastoral#fat positivity#art print#wlw#sapphic#black woman appreciation#character of color#fat character#fat woman appreciation#my art#image described

363 notes

·

View notes

Text

Y'all, this book series is everything I ever wanted in a book series. I don't know why people tried to push it as a romance book 💀. It deals with generational trauma, racism, and demons, with just a tiny pinch of romance. Lowkey thinking about making a video about this but we’ll see.

#black girl#black girls#ella pastoral#black youtuber#black girl fandom#black women#legendborn#legendborne#black books#legendborne cycle#tracy deonn

391 notes

·

View notes

Text

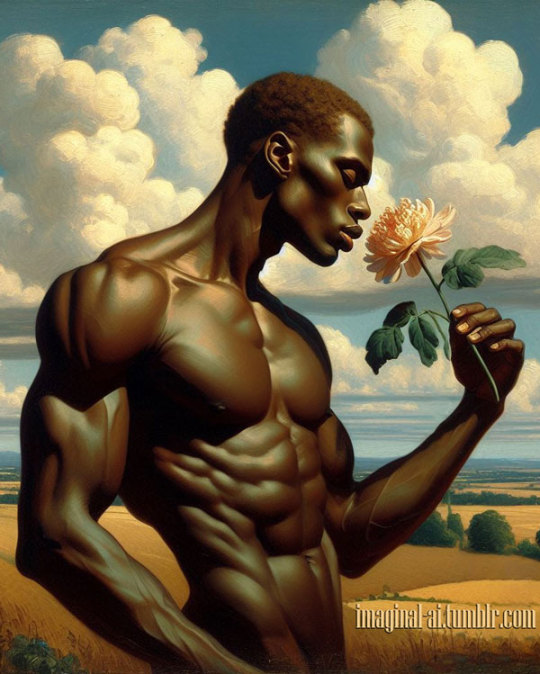

"Hero with Flowers" (0002)

(More of The Heroes and Flowers Series)

0001

#ai artwork#ai men#ai generated#ai art community#ai image#ai gay#gay ai art#black male#black men#black male beauty#black male body#black man#fashion illustration#art direction#art director#muscular#ripped#flowers#positive masculinity#pastoral beauty#pastoral scene#male torso#nude torso#inner peace#peaceful#peace#maxfield parrish

131 notes

·

View notes

Photo

But, Lawern... I'm with you completely due to my own selfishness. I will protect you forever. - Shiro Seijo to Kuro Bokushi - Episode 1

#Shiro Seijo to Kuro Bokushi#Saint Cecilia and Pastor Lawrence#White Saint and Black Pastor#shiroseijyo#Cecilia#Lawrence#白聖女と黒牧師#my gifs#my post#long post

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

The black sheep, oil painting by Claudine Lecoustre ©️2024

#french#france#art#french art#french painter#landscape painting#pastoral#winter#sheep#black sheep#cloudy sky#countryside painting#trees#winter landscape#meadows#pasture

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

#illustration#art#drawing#artists on tumblr#black and white#ink#horror#dark#gothic#goth#horror art#Romantic#skull#rabbit#demon#pastoral#peaceful

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

WAIT I HAVE AN IDEA HEAR ME OUT HEAR ME OUT-

So Gabby and Zaggy are angels, but nothing's said about Francis, yet he's just as sentient as they are, and so an idea popped into my head about his standing-

What if its like- 2 angels and Francis is the pastor of the church those angels mainly reside in

#I MEAN HEAR ME OUT#THE IDEA IS REALLY COOL#BECAUSE LIKE WHY IS FRANCIS THE ONLY OTHER CHARACTER IN THE WHOLE SHOW#AND WHY DOES HE HAVE THAT HONESTLY OMINOUS BLACK LONG CLOAK OR WHATEVER ON#WHITE SILKS USUALLY GO OVER THAT BLACK LONG CLOAK MAKING IT A FULL PASTOR GARB!!!!!!#HEAR ME OUT!!!!!!!!!!!!!!#friend francis#angel hare#the east patch

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

PASTOR JEROME STIMBOARD!!

#far cry 5#far cry stimboard#deputy#pastor jerome#bible stim#cross stim#black fabric stim#black stim#gun stim#writing stim#glasses stim#church stim#religion stim

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Auguet (from my Series of Sheep Portraits)

Rolleiflex 3.5E and Kentmere 400 film

#Rolleiflex#sheep#portrait#film photography#Kentmere 400#Auguet#pastoral#farmhouse#animal portrait#original photographers#medium format#black and white#fall#ishootfilm#imiging#lensblr

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Characters as things I've said/heard people say

Angel: *scoffs* everyone knows that to be a cowboy all you have to do is be gay and shoot people

#Angel is basically a cowboy#get this man a hat#makes direct and uncomfortable eye contact with Striker#hazbin hotel#incorrect quotes#hazbin hotel incorrect quotes#angel dust hazbin hotel#I don't actually know what was happening but the pastor went of on a cowboy tangent#there were ai generated pics of him as a cowboy firefighter police officer and a mermaid#I must have blacked out or something because when I tuned back in these pictures were replaced with bible verses#I may be going insane cause wtf was that

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

okay, y'all my homestuck deep dive is live on youtube. let's boost this one.

#black girl#black girls#ella pastoral#black youtuber#black girl fandom#black women#youtube#homestuck#video essay#video essayist#fandom#sarah z homestuck#homestuck fandom#4/13#karkat#vriska#rose lalonde#johndave#davekat#kanaya#jade#hussie#andrew hussie#internet culture#fan culture#internet history#red bard#lindsay ellis#youtuber#sarah z

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Hero with Flowers" (0004)

(More of The Heroes and Flowers Series)

0003

0002

0001

#ai artwork#ai men#ai generated#ai art community#ai image#ai gay#gay ai art#black male#black men#black male beauty#black male body#black man#fashion illustration#art direction#muscular#ripped#flowers#positive masculinity#pastoral beauty#pastoral scene#male torso#nude torso#inner peace#peaceful#peace#maxfield parrish#muscular definition#homoerotic#male figure#male art

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Poling the Marsh Hay, Peter Henry Emerson, 1886

#photography#vintage photography#vintage#black and white photography#peter henry emerson#1880s#1886#british#pastoral scene

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Thoes two get along so well, don't they? - Shiro Seijo to Kuro Bokushi - Episode 1

#Shiro Seijo to Kuro Bokushi#Saint Cecilia and Pastor Lawrence#White Saint and Black Pastor#shiroseijyo#Cecilia#Lawrence#白聖女と黒牧師#my gifs#my post#long post

83 notes

·

View notes