#Augustin Barbaroux

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

And Their Children After Them (Leurs enfants après eux), Ludovic Boukherma and Zoran Boukherma (2024)

#Ludovic Boukherma#Zoran Boukherma#Paul Kircher#Angelina Woreth#Sayyid El Alami#Gilles Lellouche#Ludivine Sagnier#Augustin Barbaroux#Amaury Chabauty#Géraldine Mangenot#2024

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

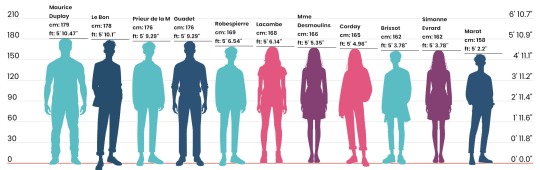

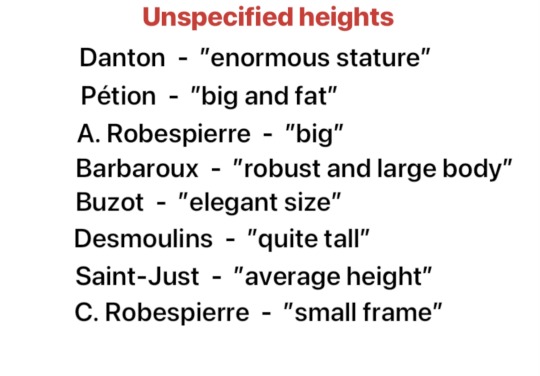

Frev appearance descriptions masterpost

Jean-Paul Marat — In Histoire de la Révolution française: 1789-1796 (1851) Nicolas Villiaumé pins down Marat’s height to four pieds and eight pouces (around 157 cm). This is a somewhat dubious claim considering Villiaumé was born 26 years after Marat’s death and therefore hardly could have measured him himself, but we do know he had had contacts with Marat’s sister Albertine, so maybe there’s still something to this. That Marat was short is however not something Villaumé is alone in claiming. Brissot wrote in his memoirs that he was ”the size of a sapajou,” the pamphlet Bordel patriotique (1791) claimed that he had ”such a sad face, such an unattractive height,” while John Moore in A Journal During a Residence in France, From the Beginning of August, to the Middle of December, 1792 (1793) documented that ”Marat is little man, of a cadaverous complexion, and a countenance exceedingly expressive of his disposition. […] The only artifice he uses in favour of his looks is that of wearing a round hat, so far pulled down before as to hide a great part of his countenance.” In Portrait de Marat (1793) Fabre d’Eglantine left the following very detailed description: ”Marat was short of stature, scarcely five feet high. He was nevertheless of a firm, thick-set figure, without being stout. His shoulders and chest were broad, the lower part of his body thin, thigh short and thick, legs bowed, and strong arms, which he employed with great vigor and grace. Upon a rather short neck he carried a head of a very pronounced character. He had a large and bony face, aquiline nose, flat and slightly depressed, the under part of the nose prominent; the mouth medium-sized and curled at one corner by a frequent contraction; the lips were thin, the forehead large, the eyes of a yellowish grey color, spirited, animated, piercing, clear, naturally soft and ever gracious and with a confident look; the eyebrows thin, the complexion thick and skin withered, chin unshaven, hair brown and neglected. He was accustomed to walk with head erect, straight and thrown back, with a measured stride that kept time with the movement of his hips. His ordinary carriage was with his two arms firmly crossed upon his chest. In speaking in society he always appeared much agitated, and almost invariably ended the expression of a sentiment by a movement of the foot, which he thrust rapidly forward, stamping it at the same time on the ground, and then rising on tiptoe, as though to lift his short stature to the height of his opinion. The tone of his voice was thin, sonorous, slightly hoarse, and of a ringing quality. A defect of the tongue rendered it difficult for him to pronounce clearly the letters c and l, to which he was accustomed to give the sound g. There was no other perceptible peculiarity except a rather heavy manner of utterance; but the beauty of his thought, the fullness of his eloquence, the simplicity of his elocution, and the point of his speeches absolutely effaced the maxillary heaviness. At the tribune, if he rose without obstacle or excitement, he stood with assurance and dignity, his right hand upon his hip, his left arm extended upon the desk in front of him, his head thrown back, turned toward his audience at three-quarters, and a little inclined toward his right shoulder. If on the contrary he had to vanquish at the tribune the shrieking of chicanery and bad faith or the despotism of the president, he awaited the reéstablishment of order in silence and resuming his speech with firmness, he adopted a bold attitude, his arms crossed diagonally upon his chest, his figure bent forward toward the left. His face and his look at such times acquired an almost sardonic character, which was not belied by the cynicism of his speech. He dressed in a careless manner: indeed, his negligence in this respect announced a complete neglect of the conventions of custom and of taste and, one might almost say, gave him an air of ressemblance.”

Albertine Marat — both Alphonse Ésquiros and François-Vincent Raspail who each interviewed Albertine in her old age, as well as Albertine’s obituary (1841) noted a striking similarity in apperance between her and her older brother. Esquiros added that she had ”two black and piercing eyes.” A neighbor of Albertine claimed in 1847 that she had ”the face of a man,” and that she had told her that ”my comrades were never jealous of me, I was too ugly for that” (cited in Marat et ses calomniateurs ou Réfutation de l’Histoire des Girondins de Lamartine (1847) by Constant Hilbe)

Simonne Evrard — An official minute from July 1792, written shortly after Marat’s death, affirmed the following: “Height: 1m, 62, brown hair and eyebrows, ordinary forehead, aquiline nose, brown eyes, large mouth, oval face.” The minute for her interrogation instead says: “grey eyes, average mouth.”Cited in this article by marat-jean-paul.org. When a neighbor was asked whether Simonne was pretty or not around two decades after her death in 1824, she responded that she was ”très-bien” and possessed ”an angelic sweetness” (cited in Marat et ses calomniateurs ou Réfutation de l’Histoire des Girondins de Lamartine (1847) by Constant Hilbe) while Joseph Souberbielle instead claimed that ”she was extremely plain and could never have had any good looks.”

Maximilien Robespierre — The hostile pampleth Vie secrette, politique et curieuse de M. J Maximilien Robespierre… released shortly after thermidor by L. Duperron, specifies Robespierre’s hight to have been ”five pieds and two or three pouces” (between 165 and 170 cm). He gets described as being ”of mediocre hight” by his former teacher Liévin-Bonaventure Proyart in 1795, ”a little below average height” by journalist Galart de Montjoie in 1795, ”of medium hight” by the former Convention deputy Antoine-Claire Thibaudeau in 1830 and ”of middling form” by his sister in 1834, but ”of small size” by John Moore in 1792 and Claude François Beaulieu in 1824. The 1792 pampleth Le véritable portrait de nos législateurs… wrote that Robespierre lacked ”an imposing physique, a body à la Danton,”supported by Joseph Fiévée who described him as ”small and frail” in 1836, and Louis Marie de La Révellière who said he was ”a physically puny man” in his memoirs published 1895. For his face, both François Guérin (on a note written below a sketch in 1791), Buzot in his Mémoires sur la Révolution française (written 1794), Germaine de Staël in her Considerations on the Principal Events of the French Revolution (1818), a foreign visitor by the name of Reichardt in 1792 (cited in Robespierre by J.M Thompson), Beaulieu and La Révellière-Lépeaux all agreed that he had a ”pale complexion.” Charlotte does instead describe it as ”delicate” and writes that Maximilien’s face ”breathed sweetness and goodwill, but it was not as regularly handsome as that of his brother,” while Proyart claims his apperance was ”entirely commonplace.” The foreigner Reichardt wrote Robespierre had ”flattened, almost crushed in, features,” something which Proyart agrees with, writing that his ”very flat features” consisted of ”a rather small head born on broad shoulders, a round face, an indifferent pock-marked complexion, a livid hue [and] a small round nose.” Thibaudeau writes Robespierre had a ”thin face and cold physiognomy, bilious complexion and false look,” Duperron that ”his colouring was livid, bilious; his eyes gloomy and dull,” something which Stanislas Fréron in Notes sur Robespierre (1794) also agrees with, claiming that ”Robespierre was choked with bile. His yellow eyes and complexion showed it.” His eyes were however green according to Merlin de Thionville and Guérin while Proyart insists they were ”pale blue and slightly sunken.” Etienne Dumont, who claimed to have talked to Robespierre twice, wrote in his Souvernirs sur Mirabeau et sur les deux premières assemblées législatives (1832) that ”he had a sinister appearance; he would not look people in the face, and blinked continually and painfully,” and Duperron too insists on ”a frequent flickering of the eyelids.” Both Fréron, Buzot, Merlin de Thionville, La Révellière, Louis Sébastien Mercier in his Le Nouveau Paris (1797) and Beffroy de Reigny in Dictionnaire néologique des hommes et des choses ou notice alphabétique des hommes de la Révolution, qui ont paru à l’Auteur les plus dignes d’attention… (1799) made the peculiar claim that Robespierre’s face was similar to that of a cat. Proyart, Beaulieu and Millingen all wrote that it was marked by smallpox scars, ”mediocretly” according to Proyart, ”deeply” according to the other two. Proyart also writes that Robespierre’s hair was light brown (châtain-blond). He is the only one to have described his hair color as far as I’m aware.

For his clothes, both Montjoie, Louis-Sébastien Mercier in 1801, Helen Maria Williams in 1795, Duperron, Millingen and Fiévée recall the fact that Robespierre wore glasses, the first two claiming he never appeared in public without them, Duperron that he ”almost always” wore them, and Millingen that they were green. Pierre Villiers, who claimed to have served as Robespierre’s secretary in 1790, recalled in Souvenirs d'un deporté (1802) that Robespierre ”was very frugal, fastidiously clean in his clothes, I could almost say in his one coat, which was was of a dark olive colour,” but also that ”He was very poor and had not even proper clothes,” and even had to borrow a suit from a friend at one point. Duperron records that ”[Robespierre’s] clothes were elegant, his hair always neat,” Millingen that ”his dress was careful, and I recollect that he wore a frill and ruffles, that seemed to me of valuable lace,”Charlotte that ”his dress was of an extreme cleanliness without fastidiousness,” Williams that he ”always appeared not only dressed with neatness, but with some degree of elegance, and while he called himself the leader of the sans-culottes, never adopted the costume of his band. His hideous countenance […] was decorated with hair carefully arranged and nicely powdered,” Fiévée that Robespierre in 1793 was ”almost alone in having retained the costume and hairstyle in use before the Revolution,” something which made him ressemble ”a tailor from the Ancien régime,” Thibadeau that ”he was neat in his clothes, and he had kept the powder when no one wore it anymore,” Germaine de Staël that ”he was the only person who wore powder in his hair; his clothes were neat, and his countenance nothing familiar,” Révellière writes that Robespierre’s voice was ”toneless, monotonous and harsh,” Beaulieu that it ”was sharp and shrill, almost always in tune with violence,” and Thinadeau that his ”tone” was ”dogmatic and imperious.”

Augustin Robespierre — described as ”big, well formed, and [with a] face full of nobility and beauty” in the memoirs of his sister Charlotte. Charles Nodier did in Souvenirs, épisodes et portraits pour servir à l'histoire de la Révolution et de l'Empire (1831) recall that Augustin had a ”pale and macerated physiognomy” and a quite monotonous voice.

Charlotte Robespierre — an anonymous doctor who claimed to have run into Charlotte in 1833, the year before her death, described her as ”very thin.” Jules Simon, who reported to have met her the following year, did him too describe her as ”a very thin woman, very upright in her small frame, dressed in the antique style with very puritanical cleanliness.”

Camille Desmoulins — described as ”quite tall, with good shoulders” in number 16 of the hostile journal Chronique du Manège (1790). Described as ugly by both said journal, the journal Journal Général de la Cour et de la Ville in 1791, his friend François Suleau in 1791, former teacher Proyart in 1795, Galart de Montjoie in 1796, Georges Duval in 1841, Amandine Rolland in 1864 (she does however add that it was ”with that witty and animated ugliness that pleases”) and even himself in 1793. Proyart describes his complexion as ”black,” Duval as ”bilious.” Both of them agree in calling his eyes ”sinister.” Duval also claims that Desmoulins’ physiognomy was similar to that of an ospray. Montjoie writes that Desmoulins had ”a difficult pronunciation, a hard voice, no oratorical talent,” Proyart that ”he spoke very heavily and stammered in speech” and Camille himself that he has ”difficulty in pronunciation” in a letter dated March 1787, and confesses ”the feebleness of my voice and my slight oratorical powers” in number 4 of the Vieux Cordelier. In his very last letter to his wife, dated April 1 1794, Desmoulins reveals that he wears glasses.

Lucile Desmoulins — The concierge at the Sainte-Pélagie prison documented the following when Lucille was brought before him on April 4 1794: ”height of five pieds and one and a half pouce (166 cm). Brown hair, eyebrows and eyes. Middle sized nose and mouth. Round face and chin. Ordinary front. A mark above the chin on the right.” Cited in Camille et Lucile Desmoulins: un rêve de république (2018). Described as beautiful by the journal Journal Général de la Cour et de la Ville in 1791 (it specifies her to be ”as pretty as her husband is ugly”), former Convention deputy Pierre Paganel in 1815, Louis Marie Prudhomme in 1830, Amandine Rolland in 1864 and Théodore de Lameth (memoirs published 1913).

Georges Danton — Described as having an ugly face by both Manon Roland in 1793, Vadier in 1794, the anonymous pamphlet Histoire, caractère de Maximilien Robespierre et anecdotes sur ses successeurs in 1794, Louis-Sébastien Mercier in 1797, Antoine Fantin-Desodoards in 1807, John Gideon Millingen in 1848, Élisabeth Duplay Lebas in the 1840s, the memoirs (1860) of François-René Chateaubriand (he specifies that Danton had ”the face of a gendarme mixed with that of a lustful and cruel prosecutor”) as well as the Mémoires de la Societé d’agriculture, commerce, sciences et arts du department de la Marse, Chalons-sur-Marne (1862). As reason for this ugliness, Millingen lifts his ”course, shaggy hair” (that apparently gave him the apperance of a ”wild beast”), the fact he was deeply marked with small-poxes, and that his eyes were unusually small (”and sparkling in surrounding darkness”), while Chateaubriand instead underlines that he was ”snub-nosed,” with ”windy nostrils [and] seamed flats.” Mercier writes that Danton’s face was ”hideously crushed.” The former Convention deputy Alexandre Rousselin (1774-1847) reported in his Danton — Fragment Historique that Danton developed a lip deformity after getting gored by a bull as a baby, had his nose crushed by another bull, got trampled in the face by a group of pigs and finally survived ”a very serious case of smallpoxes, accompanied by purpura.” In 1792, John Moore reported that ”Danton is not so tall, but much broader than Roland; his form is coarse and uncommonly robust,” while Vadier claims that Danton possessed a ”robust form, colossal eloquence,” the anonymous pamphlet that ”he was very strong, he said himself that he had athletic forms,” Desodoards that he ”held the nature of athletic and colossal forms,” Chateaubriand that he was ”a vandal in the size of Goth” (don’t know who he’s referring to), Pierre Paganel (in Essai historique et critique sur la révolution française: ses causes, ses résultats, avec les portraits des hommes les plus célèbres (1815)) that he was of an ”enormous stature,” while the pamphlet described him as a ”gigantic orator” whose voice ”shook the vaults of the hall.” René Levasseur in 1829, John Moore, Millingen, Paganel and Desodoards all agreed with this, the first four writing that Danton possessed a ”stentorian voice,” the latter that he had ”a very strong voice, without being sonorous or flexible.” In her memoirs (1834) Charlotte Robespierre claims that ”[Danton] did not at all conserve the dignity suited to the representative of a great people in his manners; his toilette was in disorder.”

Louis Antoine Saint-Just — In Saint-Just (1985) Bernard Vinot writes that Saint-Just’s childhood friend Augustin Lejeune recalled his “honest physiognomy,” and that his sister Louise would evoke her brother’s ”great beauty” for her grandchildren (I unfortunately can’t find the original sources here). The elderly Élisabeth Le Bas too stated that ”he was handsome, Saint-Just, with his pensive face, on which one saw the greatest energy, tempered by an air of indefinable gentleness and candor” (testimony found in Les Carnets de David d’Angers (1838-1855) by Pierre-Jean David d’Angers, cited in Veuve de Thermidor: le rôle et l'influence d'Élisabeth Duplay-Le Bas (1772-1859) sur la mémoire et l'historiographie de la Révolution française (2023) by Jolène Audrey Bureau, page 127). In Souvenirs de la révolution et de l’empire, Charles Nodier (who was twelve years old when he met Saint-Just…) agrees in calling him ”handsome,” but adds that he ”was far from offering this graceful combination of cute features with which we have seen it endowed by the euphemistic pencil of a lithograph,” had an ”ample and rather disproportionate chin,” that ”the arc of his eyebrows, instead of rounding into smooth and regular semi-circles, was closer to a straight line, and its interior angles, which were bushy and severe, merged into one another at the slightest serious thought that one saw pass on his forehead” and finally that ”his soft and fleshy lips indicated an almost invincible inclination to laziness and voluptuousness.” How would you know what his lips were like, Nodier. In Essai historique et critique sur la révolution française (1815) Pierre Paganel writes that Saint-Just had ”regular features and austere physiognomy.” He describes his complexion as ”bilious” while Nodier calls it ”pale and grayish, like that of most of the active men of the revolution.” Similar to Élisabeth’s description, Nodier writes that Saint-Just’s eyes were big and ”usually thoughtful,” while Paganel instead writes they were ”small and lively.” Saint-Just was of ”average height” according to Paganel, but ”of small stature” according to Nodier. According to Paganel, Saint-Just had a ”healthy body [and] proportions which expressed strength,” while Saint-Just’s colleague Levasseur de la Sarthe instead wrote in his memoirs that he was ”weak in body, to the point of fearing the whistling of bullets.” Finally, Paganel also gives the following details: ”large head, thick hair, disdainful gaze, strong but veiled voice, a general tinge of anxiety, the dark accent of concern and distrust, an extreme coldness in tone and manners.” In Lettre de Camille Desmoulins, député de Paris à la Convention, August général Dillon en prison aux Madelonettes (1793) Desmoulins jokingly writes that ”one can see by [Saint-Just’s] gait and bearing that he looks upon his own head as the corner-stone of the Revolution, for he carries it upon his shoulders with as much respect and as if it was the Sacred Host.” In Histoire de la Révolution française(1878), Jules Michelet claims that Élisabeth Le Bas had told him that this portrait, depicting Saint-Just as having ”a very low forehead, [with] the top of his head flattened, so that his hair, without being long, almost touched his eyes,” was similar to what he had looked like.

Jacques-Pierre Brissot — The following was documented after Brissot had been arrested at Moulins on June 10 1793 — ”height of five pieds (162 cm), a small amount of flat dark brown hair, eyebrows of the same color, high forehead and receding hairline, gray-brown, quite large and covered eyes, long and not very large nose, average mouth, long chin with a dimple, black beard, oval face narrow at the bottom” (cited in J.-P. Brissot mémoires (1754-1793); [suivi de] correspondance et papiers (1912)). In Journal During a Residence in France, from the Beginning of August, to the Middle of December, 1792 John Moore described Brissot as ”a little man, of an intelligent countenance, but of a weakly frame of body” and claimed that a person had told him that Brissot had told him that he is ”of so feeble a constitution” that he won’t be able to put up any resistance was someone try to assassinate him.

Jérôme Pétion — described as ”big and fat” (grand et gros) by Louis-Philippe in 1850 (cited in The Croker Papers: the Correspondence and Diaries of the late right honourable John Wilson Croker… (1885) volume 3, page 209). Manon Roland wrote in her memoirs that Pétion ”had nothing to regret physically; his size, his face, his gentleness, his urbanity, speak in his favor” as well as that he ”spoke fairly well,” a descriptions which Louis Marie Prudhomme partly agreed with, himself recording that Pétion ”had a proud countenance, a fairly handsome face, an affable look, a gentle eloquence, movements of talent and address; but his manners were composed, his eyes were dull, and he had something glistening in his features which repelled confidence” in Paris pendant le révolution (1789-1798) ou le nouveau Paris (1798). In Quelques notices pour l’histoire, et le récit de mes périls depuis le 31 mai 1793 (1794) Jean-Baptiste Louvet reported that, while on the run from the authorities after the insurrection of May 31, the less than forty years old Pétion already had a white hair and beard. This is confirmed by Frédéric Vaultier, who in Souvenirs de l'insurrection Normande, dite du Fédéralisme, en 1793 (1858) described Pétion during the same period as ”a good-looking man, with a calm and open physiognomy and beautiful white hair,” as well as by the examination of his mangled courpse on June 26 1794, which states he had ”grayish hair” (cited in Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées (1872) by Charles Vatel, volume 2, page 154.

François Buzot — according to the memoirs (1793) of Manon Roland, he had ”a noble figure and elegant size.” In the examination made of Buzot’s body after the suicide there is to read that he had black hair (cited in Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées (1872) by Charles Vatel, volume 2, page 153)

Charles Barbaroux — his son wrote in Jeunesse de Barbaroux (1822) that ”nature had richly endowed Barbaroux; a robust and large body; a charming, fine and witty physiognomy.” In 1867, François Laprade, who had witnessed Barbaroux’ execution as a thirteen year old, recollected that ”he was a brown man - that is to say he had brownish skin, black hair and beard, reclining figure” (cited in Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées, volume 3, page 728)

Marguerite-Élie Guadet — According to his passport (cited in Charlotte de Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées, volume 3, page 672): ”height of 5 pieds, 5 pouces (176 cm) middle sized mouth, black hair and eyebrows, ordinary chin, blue eyes, big forehead, thin face, upturned nose.” According to Frédéric Vaultier’s Souvenirs de l'insurrection Normande, dite du Fédéralisme, en 1793(1858), ”Guadet was a man of fine height, meagre, brown, bilious complexion, black beard, most expressive face.”

Joseph Le Bon — his passport description (cited in Louis Jacob, Joseph Le Bon, (1932) by Louis Jacob, volume 1, page 63) gives the following information: ”Height of five pieds six pouces (178 cm), light brown hair and eyebrows, high forehead, average nose, blue eyes, medium-sized mouth, smallpox scars.”

Claire Lacombe — the concierge of the Sainte Pélagie documented the following about the imprisoned Lacombe: ”height of 5 pieds, 2 pouces (168 cm). Brown hair, eyebrows and eyes, medium nose, large mouth, round face and chin, plain forehead” (cited in Trois femmes de la Révolution : Olymps de Gouges, Théroigne de Méricourt, Rose Lacombe (1900) by Léopold Lacour)

Charlotte Corday — according to her passport, ”height of five pieds one pouce (165 cm), brown hair and eyebrows, gray eyes, high forehead, long nose, medium mouth, round, forked (fourchu) chin, oval face.” (cited in Dossiers du procès criminel de Charlotte Corday, devant le Tribunal révolutionnaire(1861) by Charles-Joseph Vatel, page 55)

Prieur de la Marne — a passport dated October 1 1793 gives the following details: ”age of 37 years, height of 5 pieds 5 pouces (176 cm), blondish brown hair and eyebrows, receding hairline, long nose, grey eyes, large mouth.”

Maurice Duplay — ”height of 5 pieds 6 pouces (179 cm), blondish brown hair and eyebrows, receding hairline, grey eyes, long, open nose, large mouth, round, full chin and face.” Descriptions given in 1795 and cited in Les deniers montagnards (1874) by Jules Claretie.

Jean Lambert Tallien — Both a spy report written in 1794 found among Robespierre’s papers and Mme de la Tour du Pin, a noblewoman who met Tallien in late 1793, describe Tallien’s hair as blonde. Mme de la Tour du Pin adds that said hair was curly and that he had a pretty face.

#might eventually reblog a part 2 i ran out of links for the moment#frev#french revolution#robespierre#georges danton#jean paul marat#albertine marat#simonne évrard#maximilien robespierre#augustin robespierre#camille desmoulins#desmoulins#lucile desmoulins#charlotte robespierre#charlotte corday#brissot#pétion#prieur de la marne#maurice duplay#jean lambert tallien#joseph lebon#charles barbaroux#françois buzot#saint-just#louis antoine de saint just#yes robespierre was taller than brissot this is no drill#i like this beauty and the beast thing camille and lucile seemed to have going tho…

235 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Nothing out of the ordinary has happened here, and it is to be hoped that the evil-doers will not succeed in their maneuvers this time. Panic terror is gripping many minds, and the crowds at the bakers' are considerable. Marat's death will probably be useful to the Republic because of the circumstances surrounding it. It's a cy-devant from Caen, deliberately sent by Barbaroux and other scoundrels, addressed first to a member of the right wing in Paris, that fanatic Duperrey who twice drew the saber in the Assembly and repeatedly threatened Marat. We have indicted him as an accomplice to the assassination. You will see the details of this affair in the newspapers, and it will not be difficult for you to judge the men we were dealing with. The Minister of the Interior had, it seems, been singled out for the dagger of this monstrous woman who brought Marat down under her blows; Danton and Maximilien are still threatened; one remarkable thing is the means this infernal female used to gain access to our colleague's home. While Marat was being painted as a monster, in such a terrible way that the whole of France was fooled into believing that there was no cannibal comparable to that citizen, that woman nevertheless begged for his commiseration by writing to him: "It's enough to be unhappy to be heard". This circumstance is well suited to demaratizing Marat and opening the eyes of those who see us as bloodthirsty men. You should know that Marat lived like a Spartan and gave everything he had to those who came to him. On several occasions he said to me and my colleagues: "I can no longer satisfy the wretched crowd that comes to me, I will send some of them to you", and he did so on many times. Judge our political situation, a situation brought about by slander. Ardent but unenlightened patriots are currently agreeing with the conspirators to Pantheonize Marat. Such are the circumstances, that this proposal may eternalize the calumnies, that the hatred which seems to abandon a corpse will attach itself to Marat in the grave, and that the system of the enemies of liberty will resume with greater force than if our colleague were still among us. The most astute observer must be astonished that the most terrible weapon of the enemies of liberty is slander, and must groan at the ignorance and credulity of a people who constantly disregard it. A slander, no matter how absurd, cannot be erased, and Paris, which sees its most ardent defenders slaughtered and is content to shed tears over their graves, will still have to defend itself for centuries to come against its detractors, while Evreux, Caen, Lyon and Marseille will enjoy an almost immortal glory, because these cities will have the most skilful of conspirators and the most wicked of men as their defenders."

Augustin Robespierre in a letter to Antoine-Joseph Buissart, July 15th, 1793. From Maximilien et Augustin Robespierre, Correspondance recueillie et publiée par M. Georges Michon [p. 174-175].

#marat#jean paul marat#my translation !!#marat assassiné#frev#french revolution#the death of marat#la mort de marat#my posts

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

FREV SEXYMAN (AND WOMAN) POLL!

The pairings for round 1 are:

ROBESPIERRE VS DANTON

BRISSOT VS LEPELETIER

MARAT VS DESMOULINS

HEBERT VS COLLOT

TALLIEN VS FOUCHE

BONAPARTE VS BILLAUD-VARENNE

CARNOT VS CARRIER

BARBAROUX VS CHARLOTTE ROBESPIERRE

SAINT-JUST VS COUTHON

BARERE VS VADIER

AUGUSTIN ROBESPIERRE VS LACOMBE

PETION VS COUTHON

HEURALT VS FABRE

LE BAS VS MME. ROLAND

DAVID VS CONDERCET

LAFAYETTE VS LEON

One Red Group round and one Blue Group round will be posted daily.

#frev#french revolution#robespierre#marat#desmoulins#danton#saint just#not tagging everyone thats too much#frev sexyman poll

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

I sweAR TO GOD- If there’s one thing makes me question if I’m really aroace, it’s 18th century French men. Let me say it again…

EIGHTEEN CENTURY MFING FRENCH MEN-

LIKE WHY ARE THEY SO- AUUUUGGGHH

I know this is aesthetic attraction, BUT IMMA KEEP IT REAL WIT Y’ALL- Some of these mfs sLAP! LIKE THEY CAN HIT. ME. UP.

PUHLEASE!

Hand in marriage, Citoyen. HAND IN MARR- Nah I’m joking.

But seriously, why make them this fine bruh, like- oh my God…

IF I MISSED SOME OF YOUR FAVS OR FLOPS, PLEASE DO MENTION THEM!

#also joseph bologne (middle bottom pic) is actually a guadeloupean creole#however his father is french i believe…#probably my first post on frev#frev#french revolution#maximilien robespierre#louis antoine de saint just#camille desmoulins#georges couthon#herault de sechelles#augustin robespierre#barbaroux#joseph bologne#collot d'herbois

63 notes

·

View notes

Photo

CALIFICACIÓN PERSONAL: 7 / 10

Título Original: HHhH AKA The Man with the Iron Heart

Año: 2017

Duración: 120 min

País: Francia

Director: Cédric Jimenez

Guion: Audrey Diwan, David Farr, Cédric Jimenez. Novela: Laurent Binet

Música: Laurent Tangy

Fotografía: Augustin Barbaroux

Reparto: Jason Clarke, Rosamund Pike, Jack O'Connell, Mia Wasikowska, Jack Reynor, Geoff Bell, Volker Bruch, Noah Jupe, Barry Atsma, Kosha Engler, Krisztina Goztola, Björn Freiberg, Luca Fiorilli, James Fred Harkins Jr., Kristóf Ódor, Stephen Graham, Gilles Lellouche, Adam Nagaitis

Productora: Coproducción Francia-Bélgica-Reino Unido-Estados Unidos; Légende Films, Echo Lake Productions. Distribuidora: The Weinstein Company

Género: Action, Biography, Thriller

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt3296908/

TRAILER:

youtube

1 note

·

View note

Video

tumblr

Hey, My name is Oren Gerner, I make and love short films. you can find me here: https://www.facebook.com/groups/ShortFilmsSociety/ SYNOPSIS A teenager is walking through the forest with his classmates, looking for Gabriel, a kid from his boarding school who went missing. After a violent incident, he separates from the rest of group and starts to wander alone. He slowly drifts away from the searching crew, deeper into the forest. Starring: Thomas Doret, Eliott Le Corre. Directed and written by Oren Gerner Produced by Mélissa Malinbaum (WHY NOT PRODUCTIONS) Director of photography: Adi Mozes Assistant director: François-Xavier Dupas Edited by Juliette Alexandre Casting director: Julia Malinbaum Light Design: Georges Harnack Sound Recording and sound design by Colin Favre-Bulle Sound mix by Clément Laforce Color by Augustin Barbaroux and Yoav Raz Art Director: Marie-Cerise Bruel Directeur de production: Thomas Hakim Special effects by Daniel Falik Short Film Society: https://www.facebook.com/groups/ShortFilmsSociety/

0 notes

Video

vimeo

Hey, My name is Oren Gerner, I make and love short films. you can find me here: https://www.facebook.com/groups/ShortFilmsSociety/ SYNOPSIS A teenager is walking through the forest with his classmates, looking for Gabriel, a kid from his boarding school who went missing. After a violent incident, he separates from the rest of group and starts to wander alone. He slowly drifts away from the searching crew, deeper into the forest. Starring: Thomas Doret, Eliott Le Corre. Directed and written by Oren Gerner Produced by Mélissa Malinbaum (WHY NOT PRODUCTIONS) Director of photography: Adi Mozes Assistant director: François-Xavier Dupas Edited by Juliette Alexandre Casting director: Julia Malinbaum Light Design: Georges Harnack Sound Recording and sound design by Colin Favre-Bulle Sound mix by Clément Laforce Color by Augustin Barbaroux and Yoav Raz Art Director: Marie-Cerise Bruel Directeur de production: Thomas Hakim Special effects by Daniel Falik Short Film Society: https://www.facebook.com/groups/ShortFilmsSociety/

0 notes

Video

vimeo

Hey, My name is Oren Gerner, I make and love short films. you can find me here: https://bit.ly/2Z0Yqni SYNOPSIS A teenager is walking through the forest with his classmates, looking for Gabriel, a kid from his boarding school who went missing. After a violent incident, he separates from the rest of group and starts to wander alone. He slowly drifts away from the searching crew, deeper into the forest. Starring: Thomas Doret, Eliott Le Corre. Directed and written by Oren Gerner Produced by Mélissa Malinbaum (WHY NOT PRODUCTIONS) Director of photography: Adi Mozes Assistant director: François-Xavier Dupas Edited by Juliette Alexandre Casting director: Julia Malinbaum Light Design: Georges Harnack Sound Recording and sound design by Colin Favre-Bulle Sound mix by Clément Laforce Color by Augustin Barbaroux and Yoav Raz Art Director: Marie-Cerise Bruel Directeur de production: Thomas Hakim Special effects by Daniel Falik Short Film Society: https://bit.ly/2Z0Yqni

0 notes

Video

Dans les Yeux

Selection : San Sebastian Film Festival // Premiers Plans Angers Film Festival // Melbourne Queer Film Festival // Zinegoak Bilbao Film Festival // Torino Film Festival // Creteil Film Festival

Production : Jerome Blesson & Claudia Schebesta Image : Augustin Barbaroux Montage : Heloise Pelloquet Son : Gael Eleon, Olivier Voisin & Victor Praud

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

vimeo

Hey, My name is Oren Gerner, I make and love short films. you can find me here: https://ift.tt/2D9fuPr SYNOPSIS A teenager is walking through the forest with his classmates, looking for Gabriel, a kid from his boarding school who went missing. After a violent incident, he separates from the rest of group and starts to wander alone. He slowly drifts away from the searching crew, deeper into the forest. Starring: Thomas Doret, Eliott Le Corre. Directed and written by Oren Gerner Produced by Mélissa Malinbaum (WHY NOT PRODUCTIONS) Director of photography: Adi Mozes Assistant director: François-Xavier Dupas Edited by Juliette Alexandre Casting director: Julia Malinbaum Light Design: Georges Harnack Sound Recording and sound design by Colin Favre-Bulle Sound mix by Clément Laforce Color by Augustin Barbaroux and Yoav Raz Art Director: Marie-Cerise Bruel Directeur de production: Thomas Hakim Special effects by Daniel Falik Short Film Society: https://ift.tt/2D9fuPr

0 notes

Text

Frev nicknames compilation

Maximilien Robespierre – the Incorruptible (first used by Fréron, and then Desmoulins, in 1790).

Augustin Robespierre – Bonbon, by Antoine Buissart (1, 2), Régis Deshorties and Élisabeth Lebas. Élisabeth confirmed this nickname came from Augustin’s middlename Bon.

Charlotte Robespierre – Charlotte Carraut (hid under said name at the time of her arrest, also kept it afterwards according to Élisabeth Lebas). Caroline Delaroche (according to Laignelot in 1825, an anonymous doctor in 1849 and Pierre Joigneaux in 1908).

Louis Antoine Saint-Just – Florelle (by himself), Monsieur le Chevalier de Saint-Just (by Salle and Desmoulins)

Jean-Paul Marat – the Friend of the People (l’Ami du Peuple) (self-given since 1789, when he started his journal with the same name)

Georges-Jacques Danton – Marius (by Fréron and Lucile Desmoulins).

Éléonore Duplay – Cornélie (according to the memoirs of Charlotte Robespierre and Paul Barras. Barras also adds that Danton jokingly called Éléonore “Cornelie Copeau, the Cornelie that is not the mother of Gracchus”)

Élisabeth Duplay – Babet (by Robespierre and Philippe Lebas in her memoirs)

Jacques Maurice Duplay – my little friend (by Robespierre), our little patriot (by Robespierre)

Camille Desmoulins – Camille (given by contemporaries since 1790. Most likely a play on the Roman emperor Camillus who saved Rome from Brennus in the 4th century like Camille saved the revolution on July 12, and not a reference to Camille behaving like a manchild to the people around him like is commonly stated.) Loup (wolf) by Fréron and Lucile (1, 2), Loup-loup by Fréron (1, 2), Monsieur Hon by Lucile.

Lucile Desmoulins – Loulou (by Camille 1, 2), Loup by Camille, Lolotte (by Camille (1, 2), Rouleau by Fréron (1, 2) and Camille, the chaste Diana (by Fréron), Bouli-Boula by Fréron (1, 2).

Horace Desmoulins – little lizard (Camille), little wolf (Ricord), baby bunny (Fréron).

Annette Duplessis (Lucile’s mother) — Melpomène (by Fréron), Daronne (by Camille)

Stanislas Fréron – Lapin (bunny) (by himself (1, 2, 3, 4, 5) and Lucile. According to Marcellin Matton, publisher of the Desmoulins correspondence and friend of Lucile’s mother and sister, Fréron obtained this nickname from playing with the bunnies at Lucile’s parents country house everytime he visited there, and Lucile was the one who came up with it). Martin by Camille and himself (likely a reference to the drawing ”Martin Fréron mobbed by Voltaire” which depicts Fréron’s father Élie Fréron as a donkey called ”Martin F”.)

Manon Roland — Sophie (by herself in a letter to Buzot).

Charles Barbaroux — Nysus by Manon Roland

François Buzot — Euryale by Manon Roland

Pierre Jacques Duplain — Saturne (by Fréron)

Guillaume Brune — Patagon (by Fréron)

Antoine Buissart (Robespierre’s pretend dad from Arras) — Baromètre (due to his interest in science)

Comment who had the best/worse nickname!

#french revolution#robespierre#danton#desmoulins#buzot#barbaroux#marat#fréron#maximilien robespierre#charlotte robespierre#augustin robespierre#camille desmoulins#lucile desmoulins#horace desmoulins#stanislas fréron#georges danton#manon roland#saint-just#louis antoine de saint just#élisabeth lebas#élisabeth duplay#éléonore duplay#fréron really likes nicknames…#frev compilation

165 notes

·

View notes

Note

Was suicide really seen as noble during the French Revolution? Was there any recorded tension regarding this cultural shift with more religious or less revolutionary people/groups? Thanks!

In the book La liberté ou la mort: mourir en député 1792-1795 (2015) can be found a list of all the deputies of the National Convention that died unnatural deaths between 1792 and 1799. Of the 96 names included on it, 16 were those of suicide victims, and to these must also me added a number of botched suicide attempts as well.

Only a single one of these suicides appears to have been driven by something outside of politics, that of the deputy Charlier, who shot himself in his apartment on February 23 1797, two years after the closing of the Convention. The rest of the suicides are all very clearly politically motivated, more specifically, deputies killing themselves just as the machinery of revolutionary justice was about to catch up to them. There’s those who killed themselves while on the run and unsheltered from the hostile authorities — the girondin Rebecqui who on May 1 1794 drowned himself in Old Port of Marseille, Pétion and Buzot who on June 24 1794 shot themselves after getting forced to leave the garret where they for the last few months had been hiding out, Maure who shot himself while in hiding on 3 June 1795 after having been implicated in the revolt of 1 Prairial, Brunel, who on May 27 shot himself after failing to quell a riot in Toulon, and Tellier, who similarily shot himself on September 17 1795 due to a revolt directed against him in the commune of Chartres. Barbaroux too attempted to shoot himself on June 18 1794 but only managed to blow his jaw off. He was instead captured and guillotined. There’s those that put an end to their days once cornered by said authorities — Lidon, who on November 2 1793 shot himself after having been discovered at his hiding place by two gendarmes (he did however first fire three shots at said gendarmes, one of whom got hit in the cheek) and Le Bas who shot himself in the night between July 27 and 28 1794 as National guardsmen stormed the Hôtel de Ville where he and his allies were hiding out (according to his wife’s memoirs, already a few days before this he had told her that he would kill them both right then and there wasn’t it for the fact they had an infant son). In an interrogation held two o’clock in the morning on July 28 1794, Augustin Robespierre too revealed that the reason he a few hours earlier had thrown himself off the cordon of the Hôtel de Ville was ”to escape from the hands of the conspirators, because, having been put under a decree of accusation, he believed his death inevitable,” and there’s of course an eternal debate on whether or not his older brother too had attemped to commit suicide at Hôtel de Ville that night or if he was shot by a guard (to a lesser extent, this debate also exists regarding Couthon). There’s those who committed suicide in prison to avoid an unfriendly tribunal — Baille who hanged himself while held captive in the hostile Toulon on September 2 1793, Condorcet who took poison and was found dead in his cell in Bourg-la-Reine on 29 March 1794 (though here there exists some debate on whether it really was suicide or if he ”just” died from exhaustion) and Rühl, who stabbed himself while in house arrest on May 29 1795. On March 17 1794, Chabot tried to take his life in his cell in the Luxembourg prison by overdosing on medicine (he reported that he shouted ”vive la république” after drinking the liquor) but survived and got guillotined. Finally, there’s those who held themselves alive for the whole trial but killed themselves as soon as they heard the pronounciation of the death sentence — the girondin Valazé who stabbed himself to death on October 30 1793 and the so called ”martyrs of prairial” Duquesnoy, Romme, Goujon, Bourbotte (in a declaration written shortly before his death he wrote: ”Virtuous Cato, no longer will it be your example alone that teaches free men how to escape the scaffold of tyranny”), Duroy and Soubrany who did the same thing on June 17 1795 (only the first three did however succeed with their suicide, the rest were executed the very same day).

To these 24 men must also be added other revolutionaries that weren’t Convention deputies, such as Jacques Roux who on February 10 1794 stabbed himself in prison, former girondin ministers Étienne Clavière who did the same thing on December 8 1793 (learning of his death, his wife killed herself as well) and Jean Marie Roland who on November 10 1793 ran a sword through his heart while in hiding, after having been informed of his wife’s execution, Gracchus Babeuf and Augustin Darthé who attempted to stab themselves on May 27 1797 after having been condemned in the so called ”conspiracy of equals,” but survived and were executed the next day, as well as two jacobins from Lyon — Hidins who killed himself in prison before the city got ”liberated,” and Gaillard who did the same thing shortly after the liberation, after having spent several weeks in jail.

With all that said, I think you could say taking your life was considered ”noble” in a way, if it allowed you to die with greater dignity than letting the imposition of revolutionary judgement take it instead did. It was at least certainly a step up compared to before 1789, when suicide (through the Criminal Ordinance of 1670) was considered a crime which could lead to confiscation of property, opprobium cast on the victim’s family and even subjection of the courpse to various outrages, like dragging it through the street. To nuance this a bit, it is however worth recalling that this was only in theory, and that in practise, most of these penalties had ceased to be carried out already in the decades before the revolution, a period during which suicide, in the Enlightenent’s spirit of questioning everything, had also started getting discussed more and more. The word ”suicide” itself entered the French dictionary in 1734. Most of the enlightenment philosophes reflected on suicide and the ethics behind it. There’s also the widely spread The Sorrows of Young Werther that was first released in 1774. Furthermore, most revolutionaries were also steeped in the culture of Antiquity, where suicide was seen as an admirable response to political defeat, perhaps most notably those of Brutus and Cato the younger, big heroes of the revolutionaries. Over the course of the revolution, we find several patriotic artists depicting famous suicides of Antiquity — such as Socrates (whose death is considered by some to have been a sort of suicide) (1791) by David, The Death of Cato of Utica (1795) by Guillaume Guillon-Lethière, and The death of Caius Gracchus (1798) by François Topino-Lebrun. According to historian Dominique Godineau, the 18th century saw ”the inscription [of suicide] in the social landscape, at least in large cities: it has become “public,” people talk about it, it is less hidden than at the beginning of the century,” and she therefore argues that the decision to decriminalize it in the reformed penal code (it didn’t state outright that suicide was now OK, but it no longer listed it as a crime) of 1791 wasn’t particulary controversial.

Furthermore, that committing suicide was more noble than facing execution was still far from an obvious, universal truth during the revolution. In his memoirs, Brissot does for example recall that, right after the insurrection of August 10, when he and other ”girondins” discussed what to do was an act of accusation to be issued against them, Buzot argued that ”the death on the scaffold was more courageous, more worthy for a patriot, and especially more useful for the cause of liberty” than committing suicide to avoid it. The feared news of their act of accusation did however arrive before the girondins had reached a definitive conclusion on what to do, leading to some fleeing (among them Buzot, who of course ironically ended up being one of the revolutionaries that ultimately chose suicide over the scaffold) and some calmly awaiting their fate. In her memoirs, Madame Roland did her too consider going to the scaffold with her head held high to be an act of virtue — ”Should I wait for when it pleases my executioners to choose the moment of my death and to augment their triumph by the insolent clamours of the mob to which I would be exposed? Certainly!” In his very last speech to the Convention, convinced that his enemies were rounding up on him, Robespierre exclaimed he would ”drink the hemlock,” a reference to the execution of Socrates. The girondin Vergniaud is also said to have carried poison on him but chosen to have go out with his friends on the scaffold, although I’ve not yet discovered what the source for this is. It can also be noted that the number of Convention deputies who let revolutionary justice have its course with them was still considerably higher than those who attempted to put an end to their days before the sentence could be carried out.

According to Patterns and prosecution of suicide in eighteenth-century Paris (1989) by Jeffrey Merrick, there was indeed tension regarding the rising amount of suicides in the decades leading up to the revolution. Merrick cites first and foremost the printer and bookseller Siméon Prosper Hardy, who in his journal Mes loisirs ou journal des evenements tels qu'ils parviennent a ma connaissance (1764-1789), documented a total of 259 cases of Parisian suicides. Hardy saw these deaths as an unwelcome import from the English, who for their part were led to kill themselves due to ”the dismal climate, unwholesome diet, and excessive liberty.” He also blamed the suicides on "the decline of religion and morals," caused by the philosophes, who in their ”bad books” popularized English ways of thinking and undermined traditional values. He was not alone in drawing a connection between the suicides and the new ideas. According to Merrick, the clergy in general ”denounced the philosophes for legitimizing this unforgiveable crime against God and society, which they now associated with systematic unbelief more than the traditional diabolical temptation.” In practice, many parish priests did however still quietly bury the bodies of persons who killed themselves. The future revolutionary Louis Sébastien Mercier did on the other hand blame the government and its penchant for inflated prices and burdensome taxes for the alleged epidemic of suicides in his Tableau de Paris (1782-1783).

In La liberté ou la mort: mourir en député, 1792-1795 it is also established that there weren’t that many participants of the king that killed themselves once the wind started blowing in the wrong direction, but that is not to say they didn’t exist. As example is cited the case of a man who in April 1793 shot himself on the Place de la Révolution, before having written ”I die for you and your family” on a gravure representimg the head of Louis XVI. There’s also the case of Michel Peletier’s murderer Philippe Nicolas Marie de Pâris, royalist and former king’s guard, who, similar to Lidon, blew his brains out when the authorities had him cornered a week after the murder.

Sources:

Patterns and prosecution of suicide in eighteenth-century Paris (1989) by Jeffrey Merrick

Pratiques du suicide à Paris pendant la Révolution française by Dominique Godineau

La liberté ou la mort: mourir en député, 1792-1795 (2015) by Michel Biard, chapter 5, ”Mourir en Romain,” le choix de suicide.

Choosing Terror (2014) by Marisa Linton, page 276-279, section titled ”Choosing how to die.”

#well. this is depressing 😀#frev#french revolution#ask#would tag everyone that (tried to) killed themselves but that would take ages

58 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Teddy, Ludovic Boukherma and Zoran Boukherma (2020)

#Ludovic Boukherma#Zoran Boukherma#Anthony Bajon#Christine Gautier#Ludovic Torrent#Guillaume Mattera#Noémie Lvovsky#Augustin Barbaroux#Amaury Chabauty#2020

0 notes

Photo

CALIFICACIÓN PERSONAL: 6.5 / 10

Título Original: Coming Home in the Dark

Año: 2021

Duración: 93 min

País: Nueva Zelanda

Director: James Ashcroft

Guion: James Ashcroft, Eli Kent. Historia: Owen Marshall

Música: Matt Henley

Fotografía: Augustin Barbaroux

Reparto: Daniel Gillies, Erik Thomson, Miriama McDowell, Matthias Luafutu, Billy Paratene, Frankie Paratene

Productora: Light in the Dark Productions

Género: Comedy, Drama, Horror

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt6874762/

TRAILER:

youtube

0 notes

Photo

CALIFICACIÓN PERSONAL: 5 / 10

Título Original: Teddy

Año: 2020

Duración: 89 min

País: Francia

Director: Ludovic Boukherma, Zoran Boukherma

Guion: Ludovic Boukherma, Zoran Boukherma

Música: Amaury Chabauty

Fotografía: Augustin Barbaroux

Reparto: Anthony Bajon, Christine Gautier, Ludovic Torrent, Noémie Lvovsky, Christine Gaillard, Jeannine Dufour

Productora: Baxter FIlms, Les Films Velvet

Género: Comedy, Drama, Horror

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt10469804/

TRAILER:

youtube

0 notes