#Architectures du Bauhaus

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

A Brno (Tchéquie), la villa Tugendhat tient la vedette auprès de tous ceux qui s'intéressent à l'architecture du XXe siècle, en particulier à l'architecture de l'entre deux guerres, moment d'émergence de l'architecture moderne, avec notamment l'école du Bauhaus. Ludwig van der Rohe, qui en fut l'un des directeurs, l'a conçue en 1930.

Son inscription au patrimoine mondial de l'UNESCO a permis une belle rénovation en 2001, mais pour la visiter (en petit groupe), il faut s'y prendre plusieurs mois à l'avance. A défaut, comme nous, vous pourrez l'admirez de l'extérieur puisque l'accès au jardin reliant la villa Löw-Beer en contre-bas est libre.

Quoi qu'il en soit, vous vous consolerez sans difficulté avec pas moins de 760 constructions référencées sur ce site :

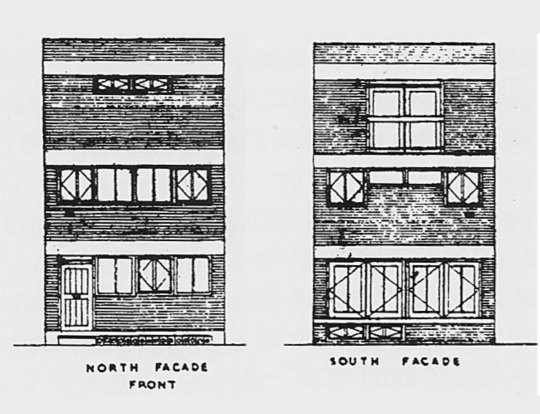

Parmi elles, cette villa a titillé ma curiosité par son nom : "villa pour deux jeunes hommes". L'architecte Otto Eisler l'a faite construire pour lui et son frère Mořic, une maison pensée parfaite pour deux jeunes passionnés de sport, de musique et collectionneurs, recevant en nombre intellectuels et artistes.

youtube

R.A. Dvorský et ses Melody boys

Je ne fus guère étonné de lire dans la fiche wikipédia d'Otto Eisler qu'il a été persécuté par les nazis pendant l'occupation allemande de la Tchécoslovaquie parce qu'il était à la fois juif et présumé homosexuel. "En avril 1939, il fut arrêté par la Gestapo et incarcéré à la prison de Špilberk, où il fut apparemment torturé. Lorsqu'il fut mis en congé, il s'enfuit en Norvège, où il arriva le 21 février 1940. Après l'invasion de la Norvège par l'Allemagne, il tenta de fuir vers la Suède mais fut blessé par balle à quelques mètres seulement de la frontière, puis déporté à Auschwitz à bord du SS. Donau. Là, il retrouve son frère Mořic (Moriz), avec qui il survit à la marche de la mort vers Buchenwald."

“Les frères” Rudolf Koppitz, 1928.

Ces deux frères qui vivaient ensemble m'ont rappelé une visite à l'hôtel Martel dans le XVIe arrondissement de Paris, construit peu avant, par un autre grand architecte du "Mouvement moderne", Robert Mallet-Stevens :

#brno#tchéquie#cz#villa tugendhat#mies van der rohe#bauhaus#architecture moderne#xxe siècle#otto eisler#maison pour deux jeunes hommes#fonctionnalisme#robert mallet-stevens#musique#jazz#R.A. Dvorský#melody boys

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Les femmes du Bauhaus

Les femmes du Bauhaus ont assuré l'économie du Centre d'art, design, architecture etc. Elles étaient fondamentalement et irrévocablement des créatrices.

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

L'Allemagne a produit de nombreux architectes

L'Allemagne a produit de nombreux architectes de renommée mondiale qui ont eu une influence significative sur l'architecture moderne et contemporaine. Voici quelques-uns des architectes allemands les plus connus :

Walter Gropius (1883-1969) : Fondateur du Bauhaus, Gropius est une figure centrale de l'architecture moderne. Il est connu pour ses idées novatrices sur la relation entre l'art, l'architecture et la technologie. Parmi ses œuvres célèbres, on trouve le bâtiment du Bauhaus à Dessau.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886-1969) : Un des maîtres du modernisme, Mies a popularisé des concepts tels que « moins c'est plus » et « la peau et les os » de l'architecture. Ses œuvres incluent le Pavillon de Barcelone et la Neue Nationalgalerie à Berlin.

Frei Otto (1925-2015) : Connu pour ses structures légères et ses tentes architecturales, Otto a conçu le toit du Stade olympique de Munich pour les Jeux olympiques de 1972. Il a reçu le prix Pritzker en 2015.

Peter Zumthor (né en 1943) : Bien que suisse, Zumthor a travaillé et influencé l'architecture en Allemagne. Il est connu pour ses œuvres minimalistes et émotionnelles comme les Thermes de Vals en Suisse et le Musée Kolumba à Cologne.

Gottfried Böhm (1920-2021) : Premier architecte allemand à recevoir le Prix Pritzker (1986), Böhm est connu pour ses églises en béton et ses bâtiments sculpturaux, tels que l'Église de pèlerinage de Neviges.

Hans Scharoun (1893-1972) : Connu pour son architecture organique, Scharoun a conçu la Philharmonie de Berlin, célèbre pour son auditorium en forme de vignoble.

Axel Schultes (né en 1943) : Célèbre pour son design du Chancelieramt (bâtiment de la chancellerie fédérale) à Berlin, Schultes est un architecte important de la période post-réunification.

Daniel Libeskind (né en 1946) : Bien que né en Pologne, Libeskind a grandi en Allemagne et est considéré comme un architecte influent dans le pays. Il est connu pour son design du Musée juif de Berlin et du One World Trade Center à New York.

Egon Eiermann (1904-1970) : Connu pour ses bâtiments fonctionnels et modernes, Eiermann a conçu des bâtiments emblématiques comme l'Église du Souvenir Kaiser Wilhelm à Berlin et le siège social de l'entreprise Olivetti à Francfort.

Ole Scheeren (né en 1971) : Connu pour ses conceptions audacieuses et innovantes, Scheeren est l'architecte du gratte-ciel CCTV à Pékin et du projet résidentiel MahaNakhon à Bangkok.

Ces architectes ont laissé une marque indélébile sur le paysage architectural mondial et continuent d'inspirer de nouvelles générations avec leurs conceptions novatrices et leurs visions uniques.

0 notes

Text

BCM116 - Week Three Journal Entry (Case Study)

youtube

For the case study, I have chosen to research the Pulse Room work by Rafael Lorenzo-Hemmer. I was very fascinated with the concept of symbolising many different people’s lives in a room full of flickering lights.

What is it?

Created in 2006 by Rafael Lorenzo-Hemmer, Pulse Room is a large immersive media installation with over one hundred 300W light bulbs hanging 3 metres from the ceiling, covering the entirety of the exhibition room. At the side of the room, there is an interface that has the ability to read a human’s pulse. When a participant touches the sensor, their palpitations get recorded and transferred to the lightbulb closest to them (which is hanging slightly lower than the rest), and it flashes in time with the rhythm of their pulse. This information is stored and when new participants enter, the previous recordings are pushed forward, so that the new pulse can be recorded. Each new participant can see the previous heartbeats of people who entered before them, as they flicker all over the ceiling of the room. The flashing light bulbs together produce a chaotically flickering light environment by various layers of repetitive rhythms, creating a vibrant and pulsating “room”. This interaction creates a unique and personal experience for each participant, blurring the lines between the artwork, the viewer, and the surrounding space.

Who is Rafael Lorenzo-Hemmer?

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer is a Mexican-Canadian installation artist who was born in 1967 in Mexico City. He graduated from Concordia University in Montréal, Canada in 1989 with a Bachelor of Sciences in Physical Chemistry. Despite his qualification in chemistry, he chose to pursue a career in interactive art, using his scientific skills and creativity to create immersive works. His works usually mix technology, performance, architecture, sound, and light to produce fascinating exhibitions that aim to influence audience participation. They also are most commonly showcased in public spaces and they are heavily inspired by phantasmagoria, carnival, and animatronics, his light and shadow works are "anti monuments for alien agency". Over the years, Lozano-Hemmer has received many awards across the globe for his works, such as:

Two BAFTA British Academy Awards for Interactive Art (London, England)

Golden Nica at the Prix Ars Electronica (Austria)

"Artist of the year" Rave Award from Wired Magazine

Rockefeller fellowship

The Trophée des Lumières (Lyon, France)

International Bauhaus Award (Dessau, Germany)

The title of Compagnon des Arts et des Lettres du Québec (Québec, Canada)

Governor General's Award (Canada).

Inspirations, Context and History

Pulse Room belongs to a genre of art known as new media art. New media art is a broad term that covers art forms that are either created, edited, and showcased through new media or digital technologies. There are many types of media art, but some examples of popular ones include:

virtual reality

digital

game

computer animation and graphics

interactive

In this case, Lozano-Hemmer’s work falls under the “interactive art” category. Interactive art takes on the form and shape of an event, where people attending the piece interact with the piece in order to make it come to life. This genre emerged in the late 19th to mid-20th century as artists started to incorporate the ever fast growing technologies into their creative processes. The recent establishment of the internet around this time also provided artists a place to reach large audiences across the globe that were previously inaccessible. Artists began to experiment with various mediums such as video, audio, digital graphics, and interactive installations.

Lozano-Hemmer's work aligns with this tradition by using technology, in this case light and sensors, to create an immersive and participatory experience for the audience. Pulse Room inspired by Macario, directed by Roberto Gavaldón in 1960, a film that features the protagonist suffering from a hunger-induced hallucination and that each person is represented by a lit candle in a cave. These lit candles symbolised the duration of individual lives, which inspired Rafael to create a similar experience. The piece was also influenced by minimalist and serial music, as well as cybernetic research on the process of cardiac self-regulation carried out by the Instituto Nacional de Cardiología in Mexico.

How was it created?

Materials used in Pulse Room:

Computer (any)

Incandescent light bulb

Metal heart sensor stand

DMX Dimmer pack/circuit board

Lorenzo-Hemmer demonstrates the integration of art and technology through using a computer programming interface. This computer is used to collect the pulse signals from the metal bar sensor and has the ability to control every single light bulb in the room. Data is updated through USB connection to a DMX circuit board, and then it gets sent to the dimmer packs (which controls the amount of power of the bulb) where the bulbs are. There are two cables in the installation, one of which boots up the computers and sensors while the other translates signals to the dimmer pack. Lorenzo-Hemmer has made use of these technologies in order to create an aesthetically pleasing room full of sparkling lights, each representing a human being, leaving visitors pondering their experience after departing.

Significance

Pulse Room is a creative way of representing the human body's uniqueness. Everyone in the world has their own story, either individually or in the form of friends, family or romance. These people of all ages together help create the artwork of our world. In Pulse Room, each individual bulb represents an individual life. Likewise the pulse itself is symbolic of the rhythm of life. Each pulse has a different rhythm, much like how every person has a different look and personality. The all-encompassing immersive environment simultaneously transforms and translates energy from one source to another. The light bulbs register a human life and compose layers of repetitive rhythms as well as a vibrant and pulsating room. the installation will affect his or her sense of space and time. The visitor's experience within the installation is an index of the living organism. The light occupies the visitor's field of vision intensifying the contrast between light and darkness and the beating effect represents his or her actual heart pattern.

How does this help me?

This inspires me for my final work as I would like to do something interactive with lights, colours as well as have something that leaves the audience pondering the meaning or questioning their view on a certain topic, but I haven’t come up with any ideas at this point. I still need to brainstorm, so we shall see what I come up with in the future!

0 notes

Photo

Shelving Unit

#charlotte perriand#shelving unit#maison du bresil#le corbusier#pierre jeanneret#bauhaus#parisian architecture#clean#minimalist#lovefrenchisbetter#parisian style#parisian vibe#parisian mood#Parisian#parisian homme

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

NEUBAUTEN

Jeanne QUEHEILLARD / Walter Gropius, Bauhaus Dessau, 1925-1926 © Hans Engels

BAUHAUS

À l’occasion du centenaire du mouvement artistique, le Goethe-Institut se fait le témoin de cette histoire.

la sortie de la Première Guerre mondiale en 1919, la jeune République progressiste de Weimar nommait l’architecte Marcel Gropius à la tête du Bauhaus (maison de la construction). Cette nouvelle école d’enseignement de l’art et de l’architecture allait révolutionner et modéliser l’enseignement artistique du xxe siècle.

Le Bauhaus défendait la synthèse de tous les arts – architecture, peinture, sculpture, cinéma – ainsi que le rapprochement de l’art et du peuple à travers l’alliance de l’artiste avec l’artisanat et l’industrie. Les débats esthétiques, sociaux et politiques qui l’ont traversé (dont témoigne plus gravement sa fermeture définitive en 1933 par les forces nazies) ont un rayonnement mondial encore à l’oeuvre.

L’exposition « Architectures du Bauhaus » de Hans Engels (25 photos tirées d’un inventaire de 58 projets) présente, dans leur état actuel, des immeubles construits par des architectes du Bauhaus de 1919 à 1933. Les éléments au fondement du mouvement moderne en design et en architecture, matériaux et conceptions industrielles, plans libres, approche fonctionnaliste, libération de l’espace, traversée de la lumière, sont mis en exergue.

On y reconnaît aussi les polémiques qui ont eu cours. L’école du Bauhaus à Dessau (1925-1926) conçue par Walter Gropius reste exemplaire. Cette construction en plans horizontaux, verre et béton, se décompose en trois corps fonctionnels, dortoirs, salles de cours et ateliers qui se glissent au coeur de la vie citadine et s’adaptent au plan urbain. L’inscription verticale BAUHAUS conçue par Herbert Bayer, responsable de l’imprimerie, préconisait une typographie élémentaire.

À la même époque, alors que Gropius défendait les ossatures d’acier et les murs en béton, la Stahlhaus (maison d’acier) de Georg Muche et Richard Paulick pour la cité Torten à Dessau revendiquait la conception industrielle et de série d’une maison tout en acier.

À Brno (République tchèque), la villa Tugendhat de Ludwig Mies van der Rohe est le témoin des conflits politiques du xxe siècle en Europe, comme le relate le film documentaire de Dieter Reifarth. Spoliée par les Nazis, réquisitionnée sous le régime communiste, elle renvoie au problème crucial de la restitution des oeuvres, question à laquelle le musée d’Aquitaine et le Goethe-Institut consacreront un colloque en mai.

Le Bauhaus, c’est aussi le théâtre, le cinéma, les textiles, la mode et les objets domestiques. Il est à la naissance du design, en lien avec le développement industriel. Des conférences avec le musée des Arts décoratifs et du Design de Bordeaux seront l’occasion, avec l’historienne d’art Kristina Lowis, de revenir sur la conception, la réalisation et la réception d’objets issus du Bauhaus. L’invitation faite à la styliste Ayzit Bostan ou aux designers allemands Axel Kufus, Stefan Diez ou Konstantin Grcic permettra de connaître leur filiation avec le Bauhaus. À travers leur influence notable dans le design à l’heure actuelle, ils témoignent d’un rayonnement du Bauhaus toujours et combien ses principes continuent d’agir dans une grande partie de la production contemporaine.

« Architectures du Bauhaus », Hans Engels, jusqu’au lundi 22 avril, Goethe-Institut. www.goethe.de du samedi 20 avril au lundi 27 mai, avec le soutien de l’Institut Heinrich Mann, Médiathèque d’Este, Billère (64140). www.mediatheque.agglo-pau.fr

Cycle sur le design allemand #2 « Le design du Bauhaus », conférence de Kristina Lowis (curatrice de l’exposition « Bauhaus Chicago » au musée du Bauhaus à Berlin), jeudi 14 mars, 19 h, musée des Arts décoratifs et du Design.

Cycle sur le design allemand #3 « Présentation des créations et dialogues », Ayzit Bostan designer textile, jeudi 28 mars, 19 h, musée des Arts décoratifs et du Design. madd-bordeaux.fr

0 notes

Photo

2:04 pm : L'exposition "L'esprit du Bauhaus" aux Arts Décoratifs : "Balcons de la Prellerhaus en contre-plongée, nouveau bâtiment du Bauhaus, photographiés par Irene Bayer" par Inconnu - Paris, novembre MMXVI.

(© Sous Ecstasy)

#art#art therapy#art daily#art show#art blog#art account#art paris#art of week#art of tumblr#art community#art lover#art addict#art work#art exhibition#l'esprit du bauhaus#arts décoratifs#architecture#sous ecstasy#mes illusions sous ecstasy#Prellerhaus

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Brutalism Post Part 3: What is Brutalism? Act 1, Scene 1: The Young Smithsons

What is Brutalism? To put it concisely, Brutalism was a substyle of modernist architecture that originated in Europe during the 1950s and declined by the 1970s, known for its extensive use of reinforced concrete. Because this, of course, is an unsatisfying answer, I am going to instead tell you a story about two young people, sandwiched between two soon-to-be warring generations in architecture, who were simultaneously deeply precocious and unlucky.

It seems that in 20th century architecture there was always a power couple. American mid-century modernism had Charles and Ray Eames. Postmodernism had Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown. Brutalism had Alison and Peter Smithson, henceforth referred to simply as the Smithsons.

If you read any of the accounts of the Smithsons’ contemporaries (such as The New Brutalism by critic-historian Reyner Banham) one characteristic of the pair is constantly reiterated: at the time of their rise to fame in British and international architecture circles, the Smithsons were young. In fact, in the early 1950s, both had only recently completed architecture school at Durham University. Alison, who was five years younger, was graduating around the same time as Peter, whose studies were interrupted by the Second World War, during which he served as an engineer in India.

Alison and Peter Smithson. Image via Open.edu

At the time of the Smithsons graduation, they were leaving architecture school at a time when the upheaval the war caused in British society could still be deeply felt. Air raids had destroyed hundreds of thousands of units of housing, cultural sites and had traumatized a generation of Britons. Faced with an end to wartime international trade pacts, Britain’s financial situation was dire, and austerity prevailed in the 1940s despite the expansion of the social safety net. It was an uncertain time to be coming up in the arts, pinned at the same time between a war-torn Europe and the prosperous horizon of the 1950s.

Alison and Peter married in 1949, shortly after graduation, and, like many newly trained architects of the time, went to work for the British government, in the Smithsons’ case, the London City Council. The LCC was, in the wake of the social democratic reforms (such as the National Health Service) and Keynesian economic policies of a strong Labour government, enjoying an expanded range in power. Of particular interest to the Smithsons were the areas of city planning and council housing, two subjects that would become central to their careers.

Alison and Peter Smithson, elevations for their Soho House (described as “a house for a society that had nothing”, 1953). Image via socks-studio.

The State of British Architecture

The Smithsons, architecturally, ideologically, and aesthetically, were at the mercy of a rift in modernist architecture, the development of which was significantly disrupted by the war. The war had displaced many of its great masters, including luminaries such as the founders of the Bauhaus: Walter Gropius, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Marcel Breuer. Britain, which was one of the slowest to adopt modernism, did not benefit as much from this diaspora as the US.

At the time of the Smithsons entry into the architectural bureaucracy, the country owed more of its architectural underpinnings to the British architects of the nineteenth century (notably the utopian socialist William Morris), precedent studies of the influences of classical architecture (especially Palladio) under the auspices of historians like Nikolaus Pevsner, as well as a preoccupation with both British and Scandinavian vernacular architecture, in a populist bent underpinned by a turn towards social democracy. This style of architecture was known as the New Humanism.

Alton East Houses by the London County Council Department of Architecture (1953-6), an example of New Humanist architecture. Image taken from The New Brutalism by Reyner Banham.

This was somewhat of a sticky situation, for the young Smithsons who, through their more recent schooling, were, unlike their elders, awed by the buildings and writing of the European modernists. The dramatic ideas for the transformation of cities as laid out by the manifestos of the CIAM (International Congresses for Modern Architecture) organized by Le Corbusier (whose book Towards a New Architecture was hugely influential at the time) and the historian-theorist Sigfried Giedion, offered visions of social transformation that allured many British architects, but especially the impassioned and idealistic Smithsons.

Of particular contribution to the legacy of the development of Brutalism was Le Corbusier, who, by the 1950s was entering the late period of his career which characterized by his use of raw concrete (in his words, béton brut), and sculptural architectural forms. The building du jour for young architects (such as Peter and Alison) was the Unité d’Habitation (1948-54), the sprawling massive housing project in Marseilles, France, that united Le Corbusier’s urban theories of dense, centralized living, his architectural dogma as laid out in Towards a New Architecture, and the embrace of the rawness and coarseness of concrete as a material, accentuated by the impression of the wooden board used to shape it into Corb’s looming, sweeping forms.

The Unité d’habitation by Le Corbusier. Image via Iantomferry (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Little did the Smithsons know that they, mere post-graduates, would have an immensely disruptive impact on the institutions they at this time so deeply admired. For now, the couple was on the eve of their first big break, their ticket out of the nation’s bureaucracy and into the limelight.

The Hunstanton School

An important post-war program, the one that gave the Smithsons their international debut, was the expansion of the British school system in 1944, particularly the establishment of the tripartite school system, which split students older than 11 into grammar schools (high schools) and secondary modern schools (technical schools). This, inevitably, stimulated a swath of school building throughout the country. There were several national competitions for architects wanting to design the new schools, and the Smithsons, eager to get their hands on a first project, gleefully applied.

For their inspiration, the Smithsons turned to Mies van der Rohe, who had recently emigrated to the United States and release to the architectural press, details of his now-famous Crown Hall of the Illinois Institute of Technology (1950). Mies’ use of steel, once relegated to being hidden as an internal structural material, could, thanks to laxness in the fire code in the state of Illinois, be exposed, transforming into an articulated, external structural material.

Crown Hall, Illinois Institute of Technology by Mies van der Rohe. Image via Arturo Duarte Jr. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Of particular importance was the famous “Mies Corner,” consisting of two joined exposed I-beams that elegantly elided inherent problems in how to join together the raw, skeletal framing of steel and the revealing translucence of curtain-wall glass. This building, seen only through photographs by our young architects, opened up within them the possibility of both the modernist expression of a structure’s inherent function, but also as testimony to the aesthetic power of raw building materials as surfaces as well as structure.

The Smithsons, in a rather bold move for such young architects, decided to enter into a particularly contested competition for a new secondary school in Norfolk. They designed a school based on a Miesian steel-framed design of which the structural elements would all be visible. Its plan was crafted to the utmost standards of rationalist economy; its form, unlike the horizontal endlessness of Mies’ IIT, is neatly packaged into separate volumes arranged in a symmetrical way. But what was most important was the use of materials, the rawness of which is captured in the words of Reyner Banham:

“Wherever one stands within the school one sees its actual structural materials exposed, without plaster and frequently without paint. The electrical conduits, pipe-runs, and other services are exposed with equal frankness. This, indeed, is an attempt to make architecture out of the relationships of brute materials, but it is done with the very greatest self-denying restraint.”

Much to the upset and shock of the more conservative and romanticist British architectural establishment, the Smithsons’ design won.

Hunstanton School by Alison and Peter Smithson (1949-54). Photos by Anna Armstrong. (CC BY NC-SA 3.0)

The Hunstanton School, had, as much was possible in those days, gone viral in the architectural press, and very quickly catapulted the Smithsons to international fame as the precocious children of post-war Britain. Soon after, the term the Smithsons would claim as their own, Brutalism, too entered the general architectural consciousness. (By the early 1950s, the term was already escaping from its national borders and being applied to similar projects and work that emphasized raw materials and structural expression.)

The New Brutalism

So what was this New Brutalism?

The Smithsons had, even before the construction of the Hunstanton School had been finished, begun to draft amongst themselves a concept called the New Brutalism. Like many terms in art, “Brutalism” began as a joke that soon became very serious. The term New Brutalism, according to Banham, came from an in-joke amongst the Swedish architects Hans Asplund, Bengt Edman and Lennart Holm in 1950s, about drawings the latter two had drawn for a house. This had spread to England through the Swedes’ English friends, the architects Oliver Cox and Graeme Shankland, who leaked it to the Architectural Association and the Architect’s Department of the London County Council, at which Alison and Peter Smithson were still employed. According to Banham, the term had already acquired a colloquial meaning:

“Whatever Asplund meant by it, the Cox-Shankland connection seem to have used it almost exclusively to mean Modern Architecture of the more pure forms then current, especially the work of Mies van der Rohe. The most obstinate protagonists of that type of architecture at the time in London were Alison and Peter Smithson, designers of the Miesian school at Hunstanton, which is generally taken to be the first Brutalist building.”

(This is supplicated by an anecdote of how the term stuck partially because Peter was called Brutus by his peers because he bore resemblance to Roman busts of the hero, and Brutalism was a joining of “Brutus plus Alison,” which is deeply cute.)

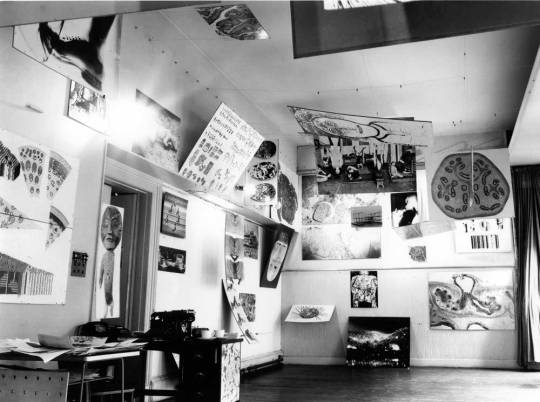

The Smithsons began to explore the art world for corollaries to their raw, material-driven architecture. They found kindred souls in the photographer Nigel Henderson and the sculptor Edouardo Paolozzi, with whom the couple curated an exhibition called “Parallel of Life and Art.” The Smithsons were beginning to find in their work a sort of populism, regarding the untamed, almost anthropological rough textures and assemblies of materials, which the historian Kenneth Frampton jokingly called ‘the peoples’ detailing.’ Frampton described the exhibit, of which few photographs remain, as thus:

“Drawn from news photos and arcane archaeological, anthropological, and zoological sources, many of these images [quoting Banham] ‘offered scenes of violence and distorted or anti-aesthetic views of the human figure, and all had a coarse grainy texture which was clearly regarded by the collaborators as one of their main virtues’. There was something decidedly existential about an exhibition that insisted on viewing the world as a landscape laid waste by war, decay, and disease – beneath whose ashen layers one could still find traces of life, albeing microscopic, pulsating within the ruins…the distant past and the immediate future fused into one. Thus the pavilion patio was furnished not only with an old wheel and a toy aeroplane but also with a television set. In brief, within a decayed and ravaged (i.e. bombed out) urban fabric, the ‘affluence’ of a mobile consumerism was already being envisaged, and moreover welcomed, as the life substance of a new industrial vernacular.”

Alison and Peter Smithson, Nigel Henderson, Eduoardo Paolozzi, Parallels in Life and Art. Image via the Tate Modern, 2011.

A Clash on the Horizon

The Smithsons, it is important to remember, were part of a generation both haunted by war and tantalized by the car and consumer culture of the emerging 1950s. Ideologically they were sandwiched between the twilight years of British socialism and the allure of a consumerist populism informed by fast cars and good living, and this made their work and their ideology rife with contradiction and tension.

The tension between proletarian, primitivist, anthropological elements as expressed in coarse, raw, materials and the allure of the technological utopia dreamed up by modernists a generation earlier, combined with the changing political climate of post-war Britain, resulted in a mix of idealism and post-socialist thought. This hybridized an new school appeal to a better life - made possible by technology, the emerging financial accessibility of consumer culture, the promises of easily replicable, luxurious living promised by modernist architecture - with the old-school, quintessentially British populist consideration for the anthropological complexity of urban, working class life. This is what the Smithsons alluded to when they insisted early on that Brutalism was an “ethic, not an aesthetic.”

Model of the Plan Voisin for Paris by Le Corbusier displayed at the Nouveau Esprit Pavilion (1925) via Wikipedia (CC BY-SA 4.0)

By the time the Smithsons entered the international architectural scene, their modernist forefathers were already beginning to age, becoming more stylistically flexible, nuanced, and less reliant upon the strictness and ideology of their previous dogmas. The younger generation, including the Smithsons, were, in their rose-tinted idealism, beginning to feel like the old masters were abandoning their original ethos, or, in the case of other youngsters such as the Dutch architect Aldo van Eyck, were beginning to question the validity of such concepts as the Plan Voisin, Le Corbusier’s urbanist doctrine of dense housing development surrounded by green space and accessible by the alluring future of car culture.

These youngsters were beginning to get to know each other, meeting amongst themselves at the CIAM – the International Congresses of Modern Architecture – the most important gathering of modernist architects in the world. Modern architecture as a movement was on a generational crash course that would cause an immense rift in architectural thought, practice, and history. But this is a tale for our next installment.

Like many works and ideas of young people, the nascent New Brutalism was ill-formed; still feeling for its niche beyond a mere aesthetic dominated by the honesty of building materials and a populism trying to reconcile consumerist technology and proletarian anthropology. This is where we leave our young Smithsons: riding the wave of success of their first project as a new firm, completely unaware of what is to come: the rift their New Brutalism would tear through the architectural discourse both then and now.

If you like this post, and want to see more like it, consider supporting me on Patreon!

There is a whole new slate of Patreon rewards, including: good house of the month, an exclusive Discord server, monthly livestreams, a reading group, free merch at certain tiers and more!

Not into recurring donations or bonus content? Consider the tip jar! Or, Check out the McMansion Hell Store! Proceeds from the store help protect great buildings from the wrecking ball.

#brutalism#architecture#architectural history#brutalism post#smithsons#alison and peter smithson#british architecture#modern architecture#le corbusier#concrete#brutalist architecture

933 notes

·

View notes

Text

Banhaus

Logo du Bauhaus, créé en 1922 par Oskar Schlemmer. Le courant Banhaus (littéralement construire une maison) est à la fois un axe architectural mais aussi de décoration et d’ameublement. Ce style est né après la première guerre mondiale en Allemagne. La vidéo ci dessous en retrace à la fois l’historique et les différents aspects. Principes Les principes fondamentaux sont : Ne pas considérer un…

View On WordPress

#Ameublement#Architecture#art#Art allemand#Art du XXè siècle#Bric à brac de culture#Bric à brac de culture en vrac#Design#Minimalisme#Mouvement#Style

1 note

·

View note

Text

La Marenda / Una mirada entrecruzada a un lado y a otro de la frontera francoespañola

Nota de intenciones en cuatro actos para la candidatura a una residencia de arquitectos en la frontera francoespañola, en Cerbère y Culera. Maison d’Architecture Occitanie-Pyénnées. Escrito a tres manos junto a Candela Carroceda y César García.

Artículo original en francés, Marzo 2020

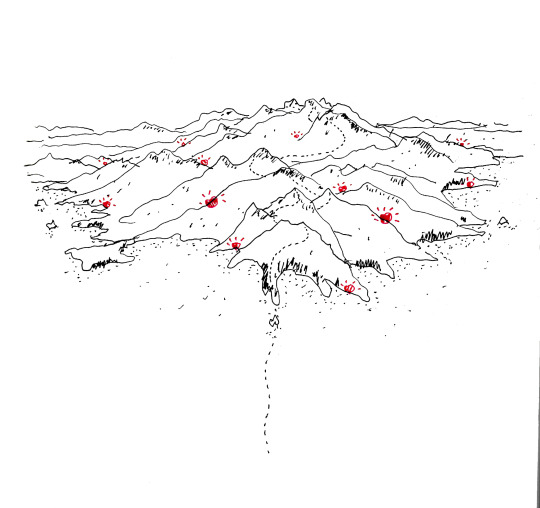

Acte 1 - Constater la frontière / Un élément qui sépare

La frontière franco espagnole s’étale sur 656,3 kilomètres, au sud ouest de la France et au nord est de l’Espagne. Cette ligne mouvante, souvent modifiée au fil de l’histoire, sera établie pour la première fois en 1659 lors du traité des Pyrénées et ensuite de manière plus définitive par Napoléon III et Isabelle II en 1856 lors du traité de Bayonne, affirmant la séparation de la péninsule ibérique du reste du continent. 602 bornes, numérotées d’ouest en est, sillonnent le terrain: la première située au bord de la Bidasoa et la dernière, au Cap Cerbère. Dorénavant l’abstraction d’une marque hispanique atavique en tant que bande ou zone de frontière sera réduite à une ligne fonctionnaliste et cartésienne. Ce fait prémonitoire annonce la séparation définitive du radeau de pierre (1), divisant un territoire ancestral côtoyé par l’histoire et les relations culturelles transpyrénéennes.

Valerio Vincenzo, Borderlines. Frontiers of Peace. 2007-2019. Frontière francoespagnole

Cette cicatrice (2) commence à l’ouest sur la Mer Cantabrique à la ville française d’Hendaye et la ville espagnole de Fuenterrabía et continue vers l’est, suivant la ligne de crêtes du massif pyrénéen avec des exceptions ponctuelles présentant un changement de versant comme la vall d’Aran ou la vallée du Querol. Des anomalies géopolitiques telles que l’île des faisans (condominio francoespagnol) le pays Quint (sur le sol du pays basque espagnol mais administré par la France), le Principauté d’Andorre (minuscule pays véritable Suisse ibérique) ou finalement, Llivia, commune espagnole isolée dans le territoire français de la Cerdagne depuis plus de quatre siècles,témoignent d’une certaine flexibilité et ambivalence octroyées par le temps. Cette frontière vivante présente des altérations et des contradictions exceptionnelles.

Profil de la chaîne des Pyrénées de Perpignan à Bayonne. Versant français. Gravure anonyme du XXéme siècle.

Acte 2 - Effacer la frontière / Un élément qui questionne

Le mot frontière trouve sa racine dans le substantif front, apportant une notion d’opposition entre deux zones séparées par ce même front, comme une troupe qui, se mettant en bataille pour combattre, fait frontière (3). Loin des temps de guerres virulentes entre les deux pays, c’est la notion de réalité physique d’une opposition qui nous intéresse aujourd’hui. Ce sentiment d’opposition et de différence qui est renforcé et intensifié par des aspects plus concrets dérivés de l’engrainage et la présence de l’Etat (usage d’une langue officielle, respect du code civil et législation, structure du système éducatif, installation des bornes, douanes et postes de frontière, etc) ainsi que ceux appartenant au terrain de l’intangible et du patrimoine populaire (référents littéraires, chaînes de télévision ou radio, les marques commerciales des produits de consommation massive, etc). La place de la République devient plaça Pi i Margall et la rue Anatole France se transforme en carrer del Mar. En un clin d’oeil, tout paraît changer. Mais malgré les harangues nationalistes, s’agit-il d’une déclaration honnête? Sommes-nous si différents et homogènes de ce que l’on affirme?

Des cartographies mentales en transition. Saul Steinberg. View of the world from 9th Avenue, 1976

D’un point de vue scientifique cette frontière constitue la limite qui sépare deux régions caractérisées par des phénomènes physiques ou humains différents. Tenant compte de la nature nomade et changeante de notre espèce et de l’impact que cela entraînerait aux phénomènes humains dont la frontière fait une sorte de contention, nous ne pouvons que constater la contradiction de ces lignes statiques, imposées souvent de manière autoritaire dans un monde complexe en changement constant. Les frontières sur nos cartes sont irrémé- diablement destinées à perdre leur légitimité a n de laisser la place aux nouvelles frontières liquides, plus abstraites et polymorphiques, re et du procès en continu de la construction des identités individuelles et collectives.

Faisons devenir la frontière un point de rencontre, un espace flexible libéra- teur et amusant, instable, abstrait et déplaçable. Convertissons les mètres linéaires d’un ligne rigide dans un nouveau volume désirable et changeant chargé de mètres cubes disponibles et fédérateurs.

La frontière comme outil d’exploration du territoire. Convertissons les mètres linéaires d’un ligne rigide dans un nouveau volume désirable et changeant chargé de mètres cubes disponibles et fédérateurs.

Acte 3 - Elargir la frontière / Atlas patrimonial transfrontalier de La Marenda

Des expériences inédites de gestion de ressources locales et organisation autonome telles que les faceries, permettant un usage consensuel et pacifique des pâturages transfrontaliers, révèlent la capacité de résilience d’un territoire de vallées insensibles aux nombreux changements politiques subis dans les deux versants pyrénéens. En 1906, la révolution des transbordeuses de Cerbère constitue un des premiers mouvements de lutte ouvrière dans un acte d’émancipation féminine et sauvegarde du capital humain local. A l’image de l’Angelus novus (4) de Walter Benjamin, figure majeure dans la construction de ce territoire de mémoire, nous proposons de tourner le regard vers le territoire, son histoire et son présent, et fouiller dans les sédiments culturels des populations locales adoptant une perspective d’absence d’une frontière séparatrice.

Les couches d’identité nationale exclusives seront supprimées. De cette manière, nous ferons revenir à la surface d’autres facteurs primaires et fondamentaux tels que le rapport avec le paysage, les pratiques vernaculaires d’autosuffisance (la pêche, l’élevage, l’agriculture) et ses manifestations ethnoculturelles communes (danses et coutumes traditionnels, outils vernaculaires, vocables et proverbes locaux, recettes typiques, odeurs, fêtes populaires, épisodes his- toriques, réseaux de chemins, typologies architectonique, etc). Par le biais de cet exercice analytique de spéculation transfrontalier, nous questionnons le concept de frontière actuelle pour ensuite l’élargir et estomper le tout en créant des nouveaux liens et histoires pour un nouveau territoire qui manque d’un récit contemporain.

Travail de documentation. Atlas d’outils typiques du territoire intérieur de l’état de Bahia, collectés par Lina Bo Bardi. Exposition Bauhaus Imaginista. Learning from / Aprendizajes reciprocos. Sao Paulo. 2019. SESC Pompei, Sao Paulo. Brasil

Avec le soutien et la connaissance du territoire des acteurs locaux (Hôtel du Belvédère du Rayon Vert, Fundación Angelus Novus de Portbou, Galeria Horizon) et en phase avec les programmes et activités qui arpentent cette nouvelle vision du territoire transfrontalier (Rencontres Cinématographiques de Cerbère et Portbou, Ecole d’été et 80e anniversaire de la mort de Walter Benjamin, résidences artistiques, etc) nous envisageons un processus de recherche en quête de tout type d’éléments identitaires a n de composer une image inédite du territoire. Nous mènerons un processus de registre hybride du territoire, mêlant information et proposition, a n de d’ouvrir le débat et d’impliquer les acteurs dans la construction des nouvelles cartographies mentales de l’espace trans- frontalier qui seront enrichies par les habitants.

Des actions marquant les esprits dans l’espace public déployant un riche catalogue d’outils de communication, tels que le dessin, la photographie, la vidéo, des enregistrements sonores ainsi que des émissions radiophoniques, nous permettrons d’interpeller les habitants, de les inviter à la discussion et la com- position du nouveau portrait de territoire. Nous cherchons la mise en contact des différents villages, établir une nouvelle conversation tout en promouvant les activités réalisés dans chaque endroit, a n de provoquer des réponses et créer des attentes autour de l’acte final, rencontre et projet communautaire: la première fiesta.

Étude d’un espace public au fil d’une journée. Architecture Reading Air Ahmedabad. Niklas fanelsa, Marius Helten, Björn Martenson, Leonard Wertgen. Ruby Press, Berlin

Acto 4 - Transposer et sublimer la frontière / La fiesta

Un appel à la convivialité, une fête transfrontalière sur la frontière, qui repose sur l’engagement des participants qui deviennent à leur tour organisateurs, hôtes, et hommenagés. Les habitants sont invités à collecter les objets nécessaires pour la composition d’un projet collectif: outils et outillage mais aussi des objets délirants,bizarres, absurdes. L’hospitalité surmonte la division territoriale. Nous dansons sur cette ligne imaginaire que nous ’agrandissons car en elle, nous fêtons notre réunion, notre rencontre corps à corps avec les autres, connues et inconnus. La fiesta (5) est le moment de faire tomber les frontières, les préjugés nationalistes et de partager le processus collectif entamé et les premiers pas d’une nouvelle identité.

La fête est accompagnée de la table, et cela est construit en cuisine. Cette conjunction ont lest l’excuse parfaite pour se rapprocher des gens et analyses ses formes d’agir avec l’environnement, l’espace public et le paysage. Les matières premiéres, la façon de les avoir, les transformer et manger créent une carte de différences et connexions transfrontalières. Cuisine participative, Cocook Madrid, 2014.

Ce n’est plus une frontière qui sépare, c’est une frontière qui rapproche. Elle n’est plus traversée en tant que ligne fictive mais vécue comme espace du possible. Elle n’est plus strictement limitée à un tracé linéaire sinon incarnée dans l’in ni des nouveaux rapports personnels, transfrontaliers ou non, issus de ce processus de redéfinition identitaire. Des nouveaux projets, de l’intensification des échanges commerciels à niveau local, des nouveaux liens économiques.

Une nouvelle frontière, façonnée de manière collective revit en nous, le bruit de la conversation retourne.

(1) Jose Saramago, Le radeau de pierre, traduit par Claude Fagues, Seuil, 1990. (2) Roberto Abínzano, les frontières sont les cicatrices de l’histoire. (3) Définition frontière. Dictionnaire Larousse du Français. (4) Walter Benjamin,Thèses sur la philosophie de l’histoire, éd. Denoël, 1971. (5) Natalia Matesanz, Asco y performance crítica. (...) Les dîners et les différents connotations aux repas, utilisées hors son contexte conventionnel constituent protocoles critiques d’action directe. Appliquées dans la ville, elles altèrent les imaginaires du public (de lo público) questionnant les démarches habituelles établies.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week 6 Bauhaus Around Me

Bauhaus - “Less is more”

To think of the Bauhaus design around us now, I will think first about Apple and MUJI, they all pretty close to Bauhaus design. Very simple lines, colours can form a product. Actually, before the Bauhaus design came out. Design is for those high class, rich people, they used heavy and complicated way to show people’s power, status, and money. However, the Bauhaus design advocate that design should serve the broad proletariat, removing all the complicated forms, and only meet the basic functional needs. It is made with simple geometric shapes, simple color combinations and technological processes to satisfy the people with lower consumption-ability

Bauhaus Architecture

The Pilgrimage Chapel of Notre Dame du Haut at Ron-champ.

Of course, this building was shocked the world at that time and was hailed as the most expressive building of the 20th century. The most impressive thing is its shape, which is as natural as a sculpture like a human hand made it! The thickness of the outer wall is very simple, and it feels like returning to the original. The light inside is also amazing. Corbusier ’s late architectural style is biased towards divine, sacred, and seclusion architecture. After masters like him, their heart has grown tired of the modern stereotyped style. Explore this kind of architecture that returns to the heart and has a sense of time.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

László Moholy-Nagy on the balcony of the Prellerhaus in Dessau (1927)

Architects, sculptors, painters, we all must return to the crafts,” the architect Walter Gropius wrote in his Bauhaus manifesto. Founded in 1919 in Weimar and forced under Nazi pressure to close in Berlin in 1933, the Bauhaus was an art school that established itself as a major influence on 20th-century art. It was created by Gropius to improve our habitat and architecture through a synthesis of the arts, crafts and industry.

Musée des Arts Décoratifs 2017 : L’ Esprit du Bauhaus

The History of the Bauhaus Reconsidered : An exhibition at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris suggests that the school's evolution is more complex and contradictory than it first appears - Joseph Giovannini

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Le Bauhaus, école et mouvement

Le Bauhaus est une école d'architecture et d'arts appliqués, fondée en 1919 à Weimar en Allemagne par Walter Gropius, architecte, designer et urbaniste allemand. Ce terme désigne par extension un courant artistique comportant architecture, design, modernité, photographie, peinture, danse et costume. Ce mouvement posera des bases autour de la réflexion de l’architecture moderne sur un style international. C’est durant la période troublée par l’après-guerre que ce mouvement artistique avant-gardiste s’inscrit dans l’histoire au début du XXème siècle.

En 1933, le Bauhaus à l’époque installée à Berlin est fermé par les nazis, considérant l’école comme enseignante d’un “art dégénéré”. L’objectif du mouvement ne consistait pas en effet en la réalisation d’un style concret, d’un canon ou d’un système. Il n’était pas question d’une quelconque préscription. Cet art est connu pour ses réalisation en matière d’architecture qui a exercé une forte influence dans le domaine des arts appliqués à travers des objets usuels. Ce mouvement est largement précurseur du design contemporain et de l’art de la performance. C’est un art contemporain avant garde.

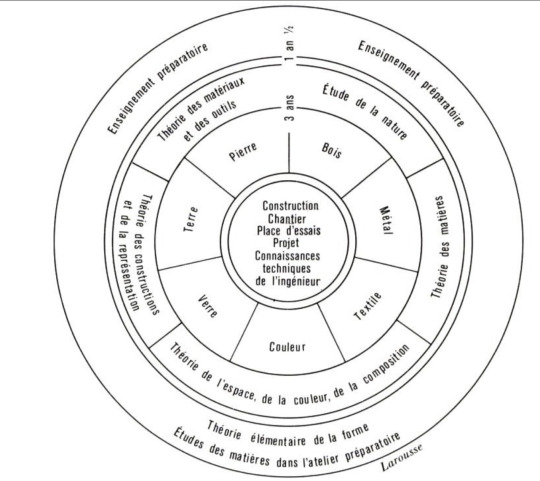

Le Bauhaus appuie sur la pluridisciplinarité et la faculté de tous les artistes à êtres de bons artisans. L’école se compose de différents cycles. Il y a une partie de connaissance théorique portant sur la couleur, la forme et les matériaux (verre /bois/sculpture/peinture/etc.). Elle a pour but de confronter les courants avant-gardistes d’alors comme l’abstraction, l’expressionnisme ou le constructivisme. Des cours de dessin de perspective et d’architecture intérieur. L’école proposait une formation artisanale sur trois ans qui mène à un examen et un diplôme de compagnon.

La communauté artistique ne demeure pas figée et encore moins unanime dans le raisonnement. Les idées sont contradictoires selon les artistes ce qui a un impact considérable sur son évolution.

Les artistes les plus connus qui participent à ce mouvement sont:

Paul Klee, Kandinsky, Walter Gropius, Marianne Brandt, Max Bill et tant d’autres !

#Design graphique#design#eartsup#bauhaus#art#Couleurs#école#mouvement#matériaux#architecture#théorie

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Poetics Of Reason

The fifth edition of the Lisbon Architecture Triennale is out, after a careful evaluation of the 48 applications received from 16 countries. The French architect Éric Lapierre developed an inclusive and expanded program based on theoretical and practical activities of educators and researchers together with the team members Sébastien Marot, Mariabruna Fabrizi, Fosco Lucarelli, Ambra Fabi, Giovanni Piovene, Laurent Esmilaire and Tristan Chadney.

Since 2007, Lisbon Architecture Triennale has been developing its mission as a non-profit organization fostering debate, thinking and practice in Architecture. The chairman João Mateus mentioned that instead of producing catalogues, the aim is to produce books with the knowledge, which can be understandable and shareable by everyone and not just architects.

La Chambre d'écoute (the listening room) by René Magritte (1958).

The program propose five main exhibitions; Economy of Means curated by Éric Lapierre is an aesthetic and design tool for results imagination and evaluation, Agriculture and Architecture: Talking the Country's Side curated by Sébastien Marot aims to learn from agriculture scientist, activists and designers who have explored the hypothesis of a future of energy descent and its consequences for the redesign and maintain of living territories,

Reproduction of Hannes Meyer’s Co-op Zimmer (1926) after photograph courtesy of © Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau.

Inner Space is a part of an ongoing project by Mariabruna Fabrizi and Fosco Lucarelli, which identifies how architectural imagination is capable of nourishing other disciplines from art to video games, virtual reality, comic books and forensic investigation to be experienced and defined as a human ability which partly relies on a collective process,

Ambra Fabi and Giovanni Piovene’s question What is Ornament? for opening different angles of inquiry instead of calling for definitive answers and in such way blueing boundaries among disciplines and finally Natural Beauty curated by Laurent Esmilaire and Tristan Chadney gathers student project from the Lisbon Triennale Millennium bop Universities Award competition and works from architects from the 13th century to the present day.

More than ever before, The Poetics of Reason stands as a condition to define an architecture for our contemporary ordinary condition. As a result of massification of construction, such a condition implies that everybody is entitled to understand architecture without a specific background in the field.

Downtown Denise Scott Brown exhibition at the Architekturzentrum Wien | Photo © Lisa Rastl, © AZW

At the her 88th birthday Denise Scott Brown was awarded with the Lifetime Achievement Award, based on criteria of excellence in the contribution to architecture as hers is one of the indispensable voices in 20th century architecture.

youtube

---

Curatorial Team

Photo © Luisa Ferreira | Image Courtesy by the Lisbon Architectural Triennale

Éric Lapierre (FR) teaches design and theory of architecture at École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture in Marne-la-Vallée Paris Est, and in École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), and has been guest teacher at Accademia di Architettura di Mendrisio, Université de Montréal (UdM), Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM), and KU Leuven in Ghent.

Sébastien Marot (FR) holds a Master’s in Philosophy and a PhD in History. He has written extensively on the genealogy of contemporary theories in architecture, urban design and landscape architecture. He is currently a professor at the École d’Architecture de Paris-Est, and guest professor at the EPFL (Enac) and GSD Harvard (as part of a programme on the Countryside led by Rem Koolhaas and AMO). Editor-in-chief of Le Visiteur (from 1995 to 2002) and Marnes (since 2010), he has authored several books, such as Sub- Urbanism and the Art of Memory (AA Publications 2003) and the critical re-edition of Ungers and Koolhaas’s The City in the City: Berlin, A Green Archipelago (Lars Müller 2013).

Fosco Lucarelli (IT) and Mariabruna Fabrizi (IT) are architects, educators and curators. They are currently based in Paris where they have founded the practice Microcities and the website Socks-studio. They teach design studios and theory courses at the Éav&t, in Paris and at the EPFL in Lausanne. F.Lucarelli was 2017-18 Garofalo fellow at the UIC School of Architecture in Chicago; he is the recipient of a grant from the Graham Foundation and he is a fellow at the American Academy in Rome. M.Fabrizi is currently head of the Architectural Drawing and Representation Department at the Éav&t, in Paris. Fabrizi and Lucarelli have been guest-curators at the 2016 Lisbon Architecture Biennale. Theirs works have been awarded and exhibited in New York, Paris, Rome, Orléans, Seoul, Chicago.

Ambra Fabi (IT) graduated in Architecture in Mendrisio and has worked as art director and project leader at Peter Zumthor and as a freelance architect in Milan. In 2012, together with Giovanni Piovene, she founded PIOVENEFABI. She assisted at the Accademia di Architettura di Mendrisio and she is currently teaching at the KU Leuven in Brussels and at École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture in Marne-la-Vallée Paris Est.

Giovanni Piovene (IT) graduated in Architecture in Venice. In 2007 he co- founded the office Salottobuono, of which he has been partner until 2012. He co-founded San Rocco Magazine (2010) and curated the ‘Book of Copies’ book and exhibition (2014). He assisted at the Accademia diArchitettura di Mendrisio and he is actually part of the FORM teaching unit in École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL). He is currently teaching at École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture in Marne-la-Vallée Paris Est.

Laurent Esmilaire (FR) worked at the offices Bernard Tschumi and Fres. Since 2011, he works at the office Éric Lapierre Experience and as assistant teacher at the École d’Architecture de la Ville et des Territoires de Marne-la- Vallée since 2014.

Tristan Chadney (UK) works at the office Éric Lapierre Experience since 2013, and as assistant teacher at the École d’Architecture de la Ville et des Territoires de Marne-la-Vallée since February 2016.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Maison Du Brésil

#charlotte perriand#le corbusier#maison du bresil#daybed#clean#minimalist#minimalism#furniture design#lovefrenchisbetter#bauhaus#bauhaus furniture#bauhaus design#bauhaus movement#bauhaus interiors#modern furniture#vintage furniture#architecture#Architectural Digest

23 notes

·

View notes