#Animal Reproduction

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Dawn of the Deed by John A. Long

Cover art by Isaac Tobin

University of Chicago Press, October 2012

We all know about the birds and the bees, but what about the ancient placoderm fishes and the dinosaurs? The history of sex is as old as life itself—and as complicated and mysterious. And despite centuries of study there is always more to know. In 2008, paleontologist John A. Long and a team of researchers revealed their discovery of a placoderm fish fossil, known as “the mother fish,” which at 380 million years old revealed the oldest vertebrate embryo—the earliest known example of internal fertilization. As Long explains, this find led to the reexamination of countless fish fossils and the discovery of previously undetected embryos. As a result, placoderms are now considered to be the first species to have had intimate sexual reproduction or sex as we know it—sort of.

Inspired by this incredible find, Long began a quest to uncover the paleontological and evolutionary history of copulation and insemination. In The Dawn of the Deed, he takes readers on an entertaining and lively tour through the sex lives of ancient fish and exposes the unusual mating habits of arthropods, tortoises, and even a well-endowed (16.5 inches!) Argentine Duck. Long discusses these significant discoveries alongside what we know about reproductive biology and evolutionary theory, using the fossil record to provide a provocative account of prehistoric sex. The Dawn of the Deed also explores fascinating revelations about animal reproduction, from homosexual penguins to monogamous seahorses to the difficulties of dinosaur romance and how sexual organs in ancient shark-like fishes actually relate to our own sexual anatomy.

The Dawn of the Deed is Long’s own story of what it’s like to be a part of a discovery that rewrites evolutionary history as well as an absolutely rollicking guide to sex throughout the ages in the animal kingdom. It’s natural history with a naughty wink.

#book cover art#cover illustration#cover art#The Dawn of the Deed#John A. Long#Isaac Tobin#paleontology#evolutionary biology#creative nonfiction#nature writing#history of sex#zoology#evolution#biology#natural history#nature#science writing#biology and evolution#animal reproduction#dinosaurs#dinosaur#placoderm#nonfiction

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mature eels will literally liquefy their stomachs to make room for sexual organs to develop. It was once believed eels reproduced asexually because lack reproductive organs found through dissection.

There are 800 known eel species in the world.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some pelagic trapjaws reproducing next to a dog

The way they do this Is rather complicated

So, trapjaws descend from trichochelids who could move their shell, and those dudes would reproduce like any other trichochelid, by detaching an arm and having swim off in search of another arm, while it slowly dissolves into gametes. If it does find another arm, which they usually do as they all release their arms at the same time, the two arms will tangle and dissolve each other and then become free swimming larvae.

The benthic trapjaws will also release their tentacles, but because these pelagic trapjaws are, well, pelagic, releasing one of their arms into the open ocean would be a waste energy, so, if they meet a trapjaw of the opposite sex, they will link up their 4 jaws and their 4 tongue like arms will emerge and they will wriggle and tangle around each other till they are fully dissolved and each trapjaw has taken a bit of the slurry of sperm and eggs into their body; where they will later on puke out small babies.

#erythra#speculative biology#speculative evolution#erythra art#spec evo#original species#erythra trapjaws#trapjaws#fish#pelagic#pelagic trapjaw#animal reproduction#alien animals#alien species#reproduction#alien sex

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

I saw you say the breeding ban was also passed down by corporate instead of by the caretakers, but I guess I don’t see anything bad with it, at least when it comes to orcas.

I'm more than happy to be wrong, but when it comes to captive orcas, they seem to have a lot of trouble breeding and having calfs that live more than a few years. Their population is very small, and without being able to get wild caught orcas, it'd just become more shallow and imbred. Like they'd have to stop breeding at some point just because of how connected genetically they all are, so isn't it fine to stop breeding them sooner rather than later? Especially with the poor outcomes?

I'm just curious because even as someone who is very positive about captive bred animals, I didn't see an issue with stopping orcas breeding. Or did this also affect bottlenose dolphins because those guys breed pretty great and have a bigger captive pop from what I've heard?

You are right that the genetic pool was becoming quite limited for captive orcas. However, through artificial insemination, I believe it could have gone on for quite a while longer, as this allowed the exchange of genetics across continents. This is what's still being done for bottlenose dolphins, since it reduces the need to transfer animals between facilities to maintain genetic diversity. Unfortunately, activists convinced the public that AI is "sexual abuse," which is honestly a really disgusting comparison to make. Semen collection and the insemination itself are, like all medical procedures, voluntary husbandry behaviors.

It’s possible they’d eventually have to stop, but I would rather that decision came from the veterinary department than from higher-ups looking to appease the masses. Animal care staff found out about the ban along with the rest of the general population, which was really bad form.

Reproduction and calf-rearing are just so vital to orca “culture.” As I’m sure you know, their society is matriarchal, centering around a mother and her offspring (and in certain ecotypes, like the famous Southern Residents, her offspring’s offspring and other close relatives). Activists often point out that SeaWorld’s orcas aren’t a true pod, but a hodgepodge of unrelated whales tossed together. This was true at one point, but after years of breeding, their social structure is far closer to a proper matriarchal pod (particularly in San Antonio and Orlando, and San Diego as well before Kasatka’s passing) than it once was.

A final point is that people in general seem to weirdly adverse to “breeding.” They see it as a sign of a zoo/aquarium/park being ��bad.” But reproduction is one of the two major goals of all animals (the other being survival), especially in highly social and highly sexual animals like dolphins, who rely on reproduction to maintain their social structure. Healthy animals have babies, with or without human assistance, and to be honest it’s more accurate to say that animals are “prevented from breeding” than to say they are “bred.”

At this point, I know it’s a lost battle. California literally made it illegal to breed orcas (and to move them or their “genetic material” in or out of the state), and nearly half of their whales live at the San Diego park. But killer whale breeding programs are alive and well in Asia, and likely will be for decades to come.

(One last salty comment— activists love to complain about captive animals being “drugged” but are strangely silent on the chemical birth control that must be used to prevent reproduction).

#I’m sorry if this one sounds bitter#it’s because I am#orcas#killer whales#cetaceans#marine mammals#seaworld#animal breeding#animal reproduction#answered asks#anonymous

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

caecilian mothers and their babies / photographed by Carlos Jared [X/X]

#caecilian#amphibian#weird animals#they're amphibians that look like worm snakes and reproductively act like mammals#and they're so fgucking cute

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Harrowing 5,000-Mile Flight of North America's Wild Whooping Cranes

Endangered Wild Whooping Cranes Must Soar Across the Continent Each Year to Ensure the Survival of Their Species—a Journey Packed with Obstacles like Power Lines and Poaching.

— By Rene Ebersole | Photographs By Michael Forsberg | March 19, 2024

Whooping Cranes Arrive at a Rain Water Basin Wetland in Nebraska to Roost for the Night.

We Were 800 Feet Up in the Air, Flying in a Helicopter with an International Team of Scientists over the vast boreal forest encompassing Canada’s Wood Buffalo National Park, when one of them shouted the alert. “Bird at nine o’clock!”.

Pilot Paul Spring circled the helicopter left, tilting for a clearer view of one of the countless pools of water stretching to the horizon. Rimmed in sand and tamarack trees, the surface glowed iridescent. In the middle of the wetland, we could make out a pair of snowy white specks, though they stood roughly five feet tall at ground level.

“There’s a chick,” said Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) wildlife biologist John Conkin, training his binoculars on a rust-colored bird, slightly shorter than its parents, high-stepping in the marsh. Spring spotted a semidry piece of land and brought us to the ground. Conkin, his ECCC ecologist colleague Mark Bidwell, and the other crane catchers, U.S. Geological Survey biologist Dave Brandt and Canadian wildlife veterinarian Sandie Black, piled out of the chopper.

They had only 12 minutes to track down and capture the elusive target: a wild whooping crane chick designed for traversing boot-sucking mud, woody brambles, and bulrushes. Any longer and the team would have to call off the chase to avoid stressing the birds too much.

A young whooping crane (center) and its parents high-step through wetlands in Wood Buffalo National Park, Canada.

As the researchers vanished into the bush, Spring and I eased off the ground and zoomed up to 500 feet for an aerial assist. Sensing the humans’ approach, the crane parents flapped their giant black-tipped wings and departed, no doubt reluctantly leaving their flightless offspring behind. “I’ve got eyes on the chick,” Spring said to the group, who could hear him through the walkie-talkies attached to their vests. “It’s just below the chopper. Come toward the chopper.”

The team crashed through the underbrush, trying to push forward faster than the soggy terrain could pull them down. In a well-practiced maneuver, Conkin approached the chick; got hold of its beak, head, and legs; and carefully tucked the bird under his arm.

Six minutes, 36 seconds: bird in hand. Now came the more technical part. Panting and sweaty, the group unpacked their gear. Brandt, a seasoned wildlife biologist who has banded at least 150 wild whooping cranes in his career, held the chick on his lap, supervising Conkin as he affixed a transmitter to one leg and color bands (blue, yellow, green) on the other.

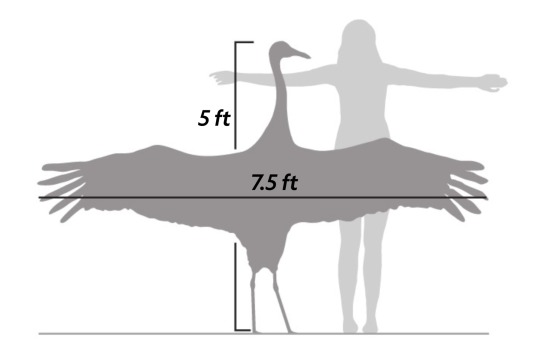

Massive Marvels! Whooping Cranes are North America's Tallest Birds. NGM Staff. Source: International Crane Foundation

Meanwhile, veterinarian Black performed a checkup, examining the bird’s eyes and taking stock of its body condition. She collected biological samples—blood, feathers, saliva, and oral and fecal swabs—for testing at the lab to reveal things such as the bird’s sex and if it had been exposed to harmful chemicals or diseases, including highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI). Then Bidwell moved in to help slip a camouflage Velcro harness around the chick and weigh it on a hanging scale.

They spoke in low voices. When their work was done, Brandt cradled the chick like a football and carried it to the edge of the marsh. There he gently set it down and dashed away. That chick—now known to the annals of science as 15J—fled in the opposite direction, pausing briefly to ruffle its feathers and shake its new leg jewelry before receding into the safety of the marsh, reuniting with its parents.

In Protected Areas of Northern Canada, whooping cranes build their nests from surrounding vegetation. Crane mothers most often lay two eggs, but usually only one chick survives.

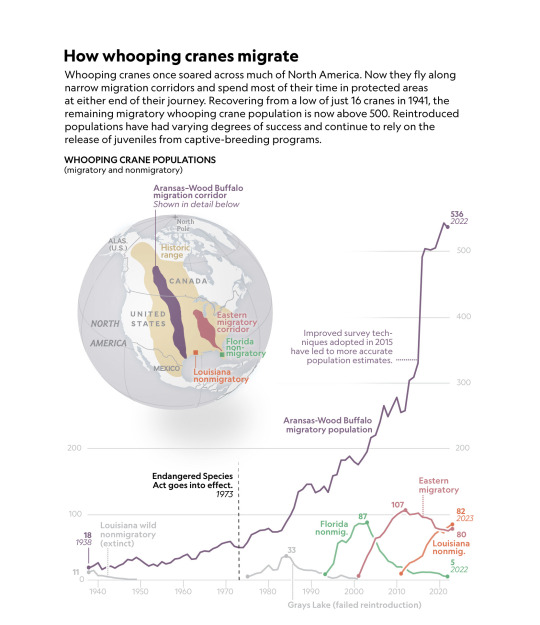

These whooping cranes embody one of North America’s greatest conservation success stories. Yet they remain the rarest of 15 crane species found throughout the world and are still endangered. Scientists estimate that more than two centuries ago, some 10,000 whooping cranes lived in North America. But they were no match for steady habitat loss and hunters in the 1900s who killed them for food, sport, and plumes to supply the millinery trade during the gilded age. By 1941, there were only 16 migratory whooping cranes left, all of them traveling a seasonal gauntlet of nearly 2,500 miles from northern Canada to the Texas Gulf Coast.

During the spring migration, whooping cranes mingle with hundreds of thousands of migrating sandhill cranes on Nebraska’s Platte River. The Platte and other wetlands in the Great Plains are vital bird stopovers.

Over the past 70 years, a raft of protections provided by grassroots conservation, legislation, habitat preservation, captive breeding, and research have slowly brought the population back. Today there are more than 800 birds, with over 530 in the central flyway migratory flock and much of the rest divided almost evenly between captivity and experimental reintroduction programs in Louisiana and Wisconsin. Still, many crane experts say it’s too soon to remove the birds from the endangered species list. The whooping crane recovery plan, written under the authority of the Endangered Species Act, has three main strategies to build both ecological and genetic stability. The first is to grow the migratory central flyway population large enough to survive a potentially catastrophic event, such as an outbreak of deadly bird flu. The second is to maintain a captive population to provide further insurance against calamity. And the third is to establish two additional self-sustaining wild flocks to help restore whooping cranes to other areas of the country where they lived historically.

Based on the current rate of population growth, some say the earliest we could plan for a victory party—albeit very tentatively—is about 2050. “The central flyway flock is halfway there,” George Archibald, co-founder of the International Crane Foundation, told me. “And neither of the experimental flocks are self-sustaining at this moment.”

Only about one-third of chicks like 15J survive to reach their breeding age of four or five years. They’re killed by predators such as bobcats or coyotes or die of fatigue and starvation during migration. They face man-made dangers including polluted wetlands, poaching, and power lines that kill millions of birds each year.

Last fall, four men pleaded guilty to shooting and killing four whooping cranes in Oklahoma in late 2021. At the crime scene, the ground was littered with feathers from the dead birds. (Top)

Two adults and a juvenile, identifiable by its rust-colored plumage, migrate south over the central plains in late autumn. Parents teach their young about reliable pit stops on the journey. (Bottom)

Considering the whooping cranes’ plight, I wanted to get a closer look at the efforts to save them. They are the polar bears of the bird world. If they disappear, we will have failed to save one of the planet’s most beautiful species, a symbol of hope and an ambassador for vanishing wilderness—and all of the species that live there. My visit to Wood Buffalo National Park sparked a monthslong journey—with several important detours—as I tracked 15J’s hazardous trip.

Even after more than a century of research, bird migration remains one of nature’s greatest mysteries. How do the animals navigate over long distances? Is their migration route encoded in their genes or learned? Can they adapt their migrations to avoid modern-day threats, including energy development and increasingly extreme weather?

Technological advances in satellite telemetry and long-term monitoring are helping crane biologists unravel some of these mysteries. Since 2009, 178 cranes from the central flyway flock have been fitted with solar-powered tracking devices that collect location data. In addition to being granted the rare opportunity to fly with crane biologists in Wood Buffalo National Park, I was given a chance to receive updates about 15J and the cohort of 17 other “J-birds” tagged in August 2022.

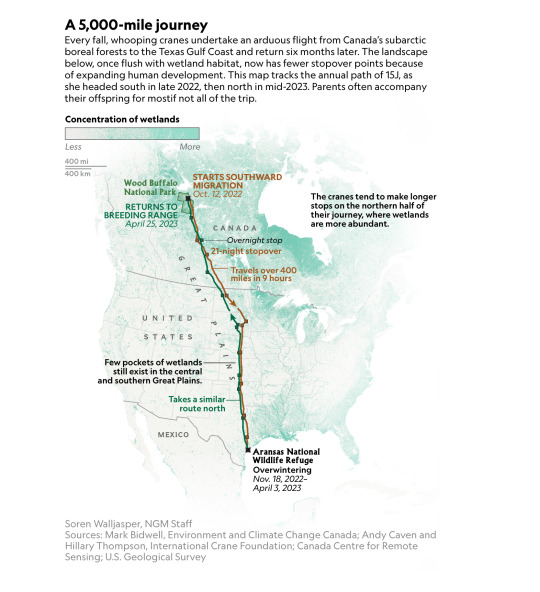

The first update arrived a few weeks later around lunchtime one day in mid-October. I was at my desk sipping a cup of soup in New York; 15J was airborne and moving south, beyond the park, an area larger than Switzerland, with no cell coverage. Likely motivated by cooling temperatures and high northwest winds, she and her parents departed from Wood Buffalo and arrived the next evening, more than 500 miles away, in Saskatchewan.

Like many other whooping cranes leaving the park, 15J and her parents took a long pit stop there, resting and refueling in the prairie potholes, shallow wetlands created by receding glaciers about 10,000 years ago, and on the northern edge of the Great Plains. Millions of birds stopping over in this region increasingly face threats such as runoff from farming chemicals including fertilizer and pesticides. But in early fall, it also provides birds with a buffet of leftover waste grain in the agricultural fields as well as insects, amphibians, and other small creatures in the wetlands. The cranes typically linger in these vital staging grounds for a few weeks.

On November 3, 15J and her parents crossed the U.S. border into North Dakota, starting their southbound push. Three days and 300 miles later, 15J’s transmitter pinged a tower in South Dakota. As the birds gradually worked their way down the flyway, they stayed in some places for days and barely touched down in others. On November 14, almost 300 miles and another state south, they stopped for a night along Nebraska’s Platte River, where cranes roost on shallow mid-river sandbars and forage in braided side channels, agricultural fields, and wet meadows.

Conservation photographer Michael Forsberg, who’s documented whooping cranes for the past four years, saw 15J there in the pale light of one morning, probing for food along the river with her parents and a lone sandhill crane. He texted me from the river: “I just spent the last two hours with 15J on the Platte. Can’t believe it. They just took off. They’re heading to where it’s warmer. It’s cold here. The river’s freezing up. It’s starting to snow.”

As the number of healthy whooping cranes increases, however, such pit stops may hold a more existential threat. A year earlier, biologists surveying birds on the Platte had counted a group of more than 46 whooping cranes—the biggest flock of migrating wild whoopers that anyone alive today has witnessed in the United States. Some experts said the sighting was a sign the cranes are learning to once again flock together in a large group, a natural tactic for survival, but one that also prompted concern. When such a large percentage of a population clumps in one place, there’s the risk that an extreme weather event or disease outbreak could severely knock their numbers back.

Recently, HPAI has killed millions of other birds in 81 countries. Wildlife managers are on high alert for outbreaks in critically endangered bird populations, including whooping cranes. In Baraboo, Wisconsin, the International Crane Foundation has taken biosecurity measures to protect the cranes in its captive facility from exposure to wild birds that could transmit the virus. Today the organization still raises whooping cranes to be released into the nearby wetlands. It also supplies some eggs to a promising project in Louisiana that is reintroducing cranes to the same wetland from which they vanished some 70 years ago after hunting wiped them out.

While 15J continued her November journey south, I boarded a plane to Louisiana to see the whooping crane class of 2022 graduate from the Freeport-McMoRan Audubon Species Survival Center in New Orleans, where the six-and-a-half-month-olds had become capable of flight, at which point they can be safely released into the wild.

Since the spring of 2011, the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries has been leading this reintroduction project. In the first season, biologists released 10 captive-bred youngsters at the White Lake Wetlands Conservation Area in Vermilion Parish, about a four-hour drive west of New Orleans. They’ve since added more juveniles to the flock, which lives in Louisiana year-round, because some bird populations don’t migrate if they’ve only ever known one place and their needs are met. The state closely monitors the birds, often with help from cooperative landowners who tolerate cranes foraging in their rice fields and crawfish ponds. Louisiana’s flock is currently composed of about 80 birds. The goal is to establish a self-sustaining population of approximately 120 individuals, including 30 reproductive pairs, for a decade without restocking.

I arrived before dawn to witness the reintroduction day, when the cranes are rounded up from their grassy enclosures at the Species Survival Center and trucked down to White Lake to be released into the marsh. Richard Dunn, the center’s assistant curator, met me inside the gate and laid out the plan. After catching 10 young cranes from their enclosures, a team of biologists would weigh them and do a health check. Then each bird would be tucked inside a cardboard box with breathing holes and loaded into a van for the drive to White Lake.

At White Lake, we were greeted by Eva Szyszkoski, a wildlife technician with the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries. Szyszkoski oversaw the birds as they were banded and fitted with tracking devices. Then the cranes in their boxes were shuttled onto a flat-bottom boat and ferried down a long canal to an area of the marsh enclosed with netting. A decoy crane stood inside the enclosure, welcoming the young birds to their new home.

One by one, each crane was removed from its box and carried by a white-costume-wearing biologist, disguised to prevent the birds from imprinting on people. As the humans waded into the muck, cradling the cranes, the birds’ heads bobbed on their long necks. Freed into the pen, they flapped their wings, stretching after a very long day.

In Louisiana, biologist Eva Szyszkoski interacts with birds that originated from a raise-and-release program, using a puppet to mimic adult crane behavior. (Top)

U.S. Geological Survey biologist Dave Brandt (left) and International Crane Foundation veterinarian Barry Hartup care for an injured whooping crane in Texas. (Bottom)

The next morning, Szyszkoski returned to find them all milling around, looking a little antsy to fly. Soon the nets would be opened, inviting them to disperse throughout the area. It’s not uncommon for many of these birds to die within their first year of being released. That may be partly because captive-raised cranes haven’t experienced the wild before—they’re naive, she said, and living in close proximity to people, which means a high chance of collision with power lines and fences. More than a dozen whooping cranes have been shot and killed over the course of the project. Occasionally, some just vanish without a trace.

More than 1,600 miles into her journey, 15J was flapping a route through America’s heartland. On November 15, her transmitter connected with a cell tower in Oklahoma, a state where one of the largest wind farms in the U.S. had recently come online.

As policymakers and the energy industry work to reduce the country’s carbon footprint, there are concerns about how eco-friendly energy advancements and habitat disturbance may affect migratory birds such as whooping cranes. A recent study showed these creatures avoid wind farm areas, preventing them from using some important stopover sites. At least 5,500 turbines have been erected in the birds’ migratory pathway, and over 18,000 more are planned. So far there’ve been no reports of whooping cranes being killed by turbines, but the accompanying increase in power lines is a major concern to conservation groups, who continue to advocate for careful site placements that may reduce the risk of potential collisions and for making power lines more visible with reflective markers.

In Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, Texas, whooping cranes prance alongside American white pelicans at sunrise. The nearly five- foot-tall birds need open spaces like this salt marsh pond to thrive.

One day and 260 miles later, 15J arrived in Texas near Fort Worth. By Thanksgiving, her transmissions went dark. USGS biologist Dave Brandt told me she was likely out of range of a cell phone tower in the state’s 115,000-acre Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, established in 1937 as a safe haven for migratory waterfowl and other wildlife. If so, that would mean her first fall migration was a success—she’d traveled some 2,500 miles over the course of about a month and could spend the winter resting along Texas’s Gulf Coast.

This picturesque vista of coastline, salt marshes, and tidal ponds is the winter stage where whooping cranes and their lifelong mates perform elaborate courtship dances, spinning in pirouettes, hopping and flapping, bobbing crimson-capped heads, and bugling their namesake calls.

But even on these wintering grounds there are threats, including coastal development and sea-level rise caused by climate change. Some scientists predict rising seas and subsequent saltwater intrusion will convert more than 50 percent of the Texas Gulf Coast’s freshwater wetlands to open water by 2100. Meanwhile, freshwater inflows are declining because of persistent drought and thirsty cities such as San Antonio upstream. Changes to salinity in the coastal estuaries pose problems for blue crabs and wolfberry plants—primary food sources for whooping cranes. Some conservation groups have warned that without more thoughtful conservation of this larger ecosystem, the whooping crane could lose its only wintering home before the end of the century.

In December I met Brandt in Texas to attempt to locate 15J and other J-birds in their winter grounds. Standing along the Intracoastal Waterway, we looked out over a salt marsh stretching at least a mile. It seemed like a large area but was a fraction of the historic marsh devoured by development in recent decades. Suddenly, two whooping cranes flew up from behind a grassy dune, white feathers gleaming in the sunlight. “They’re here because this just doesn’t exist anywhere along the coast anymore,” Brandt said of the rich habitat. “This portion of the peninsula has about 40 percent of the population wintering here.” Shortly after dawn the next morning, we boarded a fishing boat and spent eight hours fruitlessly searching for 15J along the Aransas refuge and nearby shorelines. We did, however, find several other whooping crane families, including a male bird, 11J, tagged around the same time the previous August. He was walking along the salt marsh begging—peep, peep, peep, peep—for his parents to share the blue crabs and wolfberries in their beaks. They seemed intent on teaching him to find his own food.

Next evening, on my way home to New York, I got a text from Brandt: 15J’s transmitter had “checked in,” revealing her location was within a mile of where we’d cruised along the coast.

Now another full migration cycle through spring and fall has passed. Each time, 15J has proved to be the most elusive traveler among the J-birds. I often receive updates about others almost daily, but I’ve heard about her only a handful of times. Whenever there’s been a long gap, I’ve worried: Did she collide with a power line? Get eaten by a coyote? Was she shot by a poacher? Or did she succumb to an illness?

If all goes well, 15J will be among the now 536 recorded whooping cranes preparing to depart Texas this spring, when their instincts signal it’s again time to arrow north. In the span of a month, they’ll travel 2,500 miles to Wood Buffalo National Park, where many of the adults will build nests and lay eggs. With luck, in a few more years it will be 15J’s turn to join that cycle too, helping her species continue its climb back from the edge of extinction.

#Whooping Cranes#Endangered#Endangered Species#Animal Migration#Wildlife Conservation#Watershed#Nests#Animal Reproduction#Wetlands

0 notes

Text

Leopard slugs penis’ are in their heads. And get each other pregnant.

And if they don’t find a mate; they’re male and female so they can reproduce with themselves.

The more you know I suppose

I’m watching Queer Earth. It’s pretty neat, it’s about queerness in nature.

0 notes

Text

#vote biden#vote blue#vote democrat#please vote#voting#election 2024#get out the vote#2024 elections#us elections#american politics#vote vote vote#politics#rock the vote#biden administration#joe biden#biden#president biden#us election#debate#2024 election#election#presidential election#general election#us politics#project 2025#women's rights#trans rights#human rights#reproductive rights#animal rights

762 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sleeptober day 24 — Saturate

his final form

#fuck it dawg my colour reproduction from my ipad to phone is so fucked#if its too dark lmk i am hhhhhh#anyways was gonna animate this but alas. very few spoons. the water is kinda :/ as it is so i dont wanna fuck with physics lol#sleep token#sleep token vessel#sleep token fanart#vessel sleep token#sleeptober#sleeptober 2024#elkk.art#cat nap#worshitposting

352 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yotici got another redesign (pictured here with tentacles dropped, which would usually be held flat under the body when not in use).

They still have no definitive place in the tree of life besides 'some kinda stem fish lineage that doesn't exist irl', loosely set within the lobe-finned fish. Their beaks are very similar to parrotfish in being formed of fused teeth, which are very tough and accommodate wear from sediment in their diet (mostly consisted of seagrass, but also including kelps/other seaweeds, algae, living corals, some invertebrates). The tentacles are derived from clasper-like reproductive organs and are functional, fairly strong manipulating limbs (though not built for heavy lifting).

They are large, slow moving animals, capable of delicate maneuvering and short bursts of speed but not continual fast pace. Size and community protection provides most of their defense from common predation, though they are very vulnerable to predation from People with Harpoons due to their slow speed and shallow water habitats.

#TOP 10 SADDEST ANIME DEATHS: these guys slowly transforming into just like normal fish#I'm not getting rid of their extremely improbable reproductive cycle though. Nothing exactly like it exists in fish but I think it can be#at least justified as extreme specialization into care for eggs (probably as a byproduct/driving factor of sapience and sociality)#The clasper tentacles also kind of feel like cheating but I think manipulating limbs derived from genitalia is a cool concept#yotici

213 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fuck EVERYONE that said Abortion would just be "left to the states" or saying we were "fear mongering" and had "Trump Derangement Syndrome".

#abortion#abortion rights#pro abortion#abortion is healthcare#abortion is a human right#abortion is essential#abortion is a right#women's health#women's healthcare#women's rights#pro choice#reproductive rights#reproductive health#reproductive justice#reproductive freedom#us politics#politics#non anime#fucking pieces of shit#CALL YOUR FUCKING REPRESENTATIVES

80 notes

·

View notes

Note

I don’t mean this to be snarky (just trying to learn more) but do you have a source for saying that preventing cetaceans/orcas from breeding in captivity harms their welfare? my thought was that allowing breeding would improve it but not allowing it wouldn’t decrease it, bc they can have other forms of enrichment.

Thank u 😊

Thank you for asking! Here's a few informal sources from current cetacean experts.

This quote is from Dr. Isabella Clegg, a PhD scientist specializing in dolphin behavior and welfare. She runs an organization that provides third party welfare checks to zoos, aquariums, and sanctuaries. It's also worth noting that she is neither explicity pro- nor anti-captivity.

"Reproduction is the most natural and fundamental life event for dolphins, and all animals, which means it is likely to be good for their welfare. The key factor that enhances welfare is the presence of young dolphins in the group, and for 3 main reasons. The presence of young cetaceans has been shown to 1) increase positive social behaviour in adults, 2) provide close social bonds for females, which they would not otherwise experience, and 3) reduce male coercive behaviour towards females with young. All of these factors would lead to improved welfare at the group level, and if breeding was banned, welfare would likely be reduced for the affected groups." (x)(x)

Below, you'll find an interview with Dr. Holley Muraco, the current Director of Research at the Mississippi Aquarium, speaking on the importance of reproductive behavior to the welfare of managed dolphins during her time at Dolphin Quest (a company founded and still owned by marine mammal veterinarians). Dr. Muraco's PhD is in dolphin reproductive physiology.

youtube

I hope you find this helpful!

#to go with my last ask#dolphins#cetaceans#marine mammals#animal behavior#animal breeding#animal reproduction#animal welfare#answered asks#anonymous

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dulphin giving birth

#animals#science#education#nature#photography#dolphin#sea#mammal#cute animals#funny#lol#wholesome#adorable#landscape#paradise#explore#travel#photographers on tumblr#gifs#ocean#reproduction#scientific research#mating#underwater#giving birth

181 notes

·

View notes

Text

Learning more about animals made me think about an interesting comparison on how we decide to reproduce, compared to how animals do it.

In the wild, animals will usually reproduce less, or simply survive less and thus do less populating, if the habitat isn't suitable for them, temperature is wrong, and if they don't have enough reliable food sources. Sometimes they will be able to adapt to a different habitat and temperature, like having their reproduction cycle delayed or done in a different time of year so that their young would survive, but if there's no food source, they'll reproduce in smaller numbers.

This is why sometimes animals will overpopulate the areas near humans, if they're able to access people's food storage, trashbags and pantries, it will give them a great, fulfilling source of food and thus an incentive to reproduce as much as they want to - after all, there's food for everyone.

But with humans, it's like we don't even pay attention to that. Or rather, our reproduction is governed by culture that isn't built around human needs and quality of life. We're taught that we need to reproduce, especially if we're women, because:

everyone else is doing it and it's the only normal thing to do

if we don't do it we're failing to contribute to future society

we're going to be an outcast if we don't do it

we're going to end up alone and unloved if we don't do it

there's a limited time frame in which we can do it, and if we don't we might regret it later

there's intense pressure all around us from our peers, relatives, family, cousins and others to do it, and they are all assuming we will and ask us why

if we don't we're contributing to extinction of the human species

we're supposed to want to do it

we're threatened of missing out on a fulfilled life if we don't do it

we're depicted as wasted potential if we don't do it

we're told it's what we exist for and it should be our only purpose to do it

And this fails to take into account absolutely everything that comes into being with creating human life. We aren't supposed to pay attention to the amount and quality of food that we have, to the state of the habitat all around us (if we can even access the information about it), the amount of energy, free time and willingness we have to nurture and raise a human child, or what kind of life this child can have in a world like this. It's almost like we're pushed to be more mindless than animals, reproducing simply because it's the thing that is done, rather than assessing the situation and making a reasonable call of whether someone should be living in a world in this state.

So whose idea was it to create a culture like this, who benefits from it? The answer is very simple, m*n. Just from looking at the culture they developed, it's obvious they don't care about the quality, length, or resources put into a new human's life, all they care about is producing as much offspring as possible, regardless of circumstances. All of the beliefs I've mentioned above, that are forced onto women, come from that simple-minded desire: let us multiply uncontrollably. That's also where the idea of taking away womens choices comes from; it makes it all male choice. They can decide for a woman, whether she'll have a child or not, giving them absolute control over human reproduction, while they clearly do not care what kind of society this builds or what are the consequences for the said children.

When this control is put into women's hands, all of these circumstances are taken into account. Quality of environment, available funds, food, energy, human influence, the amount of danger and threat to the child, the climate, the chance of that child having a safe and happy life, woman will be aware of all of this, because she is the one who will make sure that child stays alive and well. Fathers can ignore all of this because they know mothers will take on this labour on themselves if given no other options.

I've read recently, on how human lifespan increased so grandmothers would be able to take care of their grandchildren, giving the parents more time to work and care for themselves, and isn't it interesting? How only women were ever expected to do that. Every grandfather I've heard of was not only incapable of taking care of a child, but also incapable of taking care of himself, burdening his wife with his every need until his death. Often, they were also a danger to the children (not every single time, but often enough to be mentioned).

And we're stuck in the world where they're the ones making the calls to create more children endlessly, all while ignoring the circumstances of that child's life, and doing massive acts of violence, wars, terrorism, destruction and devastation of human life worldwide, ultimately killing both mothers and children.

It feels wrong on every level that anyone except women should have authority on human life, when to reproduce and in which circumstances. We have to endure devastating trauma and pain, intrusion in our own bodies and risk of death to make just one person. We evolved to live longer in order to take care of children, to create a better environment for them to live in, and we should let someone else make the call? It's insane.

Not only women should have the ultimate say in this, for the sake of quality of human life and the environment, but all of the culture surrounding reproduction should change. Making children in a world where we can't care for, feed and protect them isn't normal. Not paying attention to whether a creation of a child will only cause extra suffering to the child, is not how we create a future our children can live happily in. Males spreading their broken dna is not worth creating a human society that is built up on suffering, and will lead into more suffering.

#human reproduction#pro abortion#anti natalism#radical feminism#feminism#reproduction#humans vs animal reproduction

389 notes

·

View notes

Text

#vote biden#vote blue#vote democrat#please vote#voting#election 2024#get out the vote#2024 elections#us elections#american politics#vote vote vote#politics#rock the vote#biden administration#joe biden#biden#president biden#us election#debate#2024 election#election#presidential election#general election#us politics#project 2025#women's rights#trans rights#human rights#reproductive rights#animal rights

393 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Lion's Problem"

So last year the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs commissioned me to make an animation about birth control, so I did one about a trans lion taking birth control, though they underpaid me and never told me if they actually aired it so here it is

#animation#2d animation#reproductive health#trans health#testosterone#birth control#my art#art#lion#cute#procreate#my animation#project#commission#work art#lions problem

165 notes

·

View notes