#Amba Alagi

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

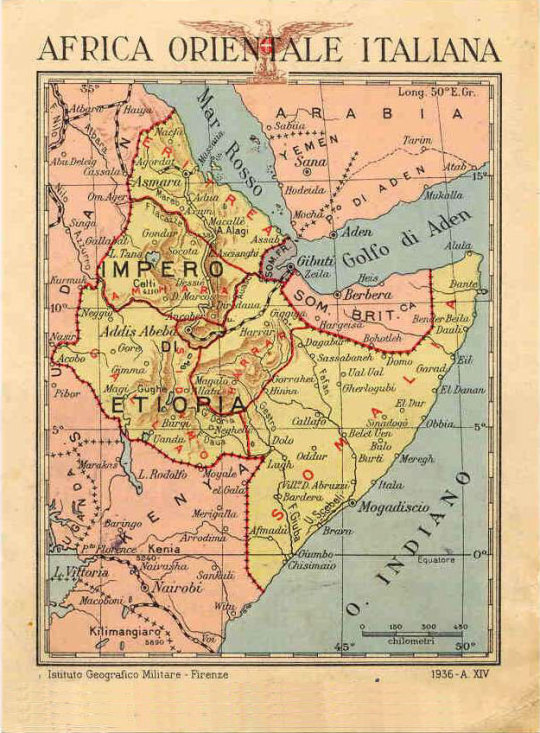

Pillole di Seconda Guerra Mondiale: 9 maggio

1940 – Paesi Bassi. L’U-Boot U-9 affonda il sommergibile francese Doris al largo di Den Helder. 1940 – Gran Bretagna. La coscrizione viene estesa agli uomini di 36 anni. 1940 – Fronte occidentale. L’OKW il Comando Supremo germanico emana le direttive per l’attacco sull’intero fronte, previsto per la mattina del giorno dopo. 1940 – Belgio. Dalle 23,15, in previsione dell’attacco tedesco viene…

View On WordPress

#19 maggio 1941#9 maggio 1940#9 maggio 1941#9 maggio 1942#9 maggio 1943#9 maggio 1944#9 maggio 1945#Africa Orientale Italiana#Amba Alagi#Bombardamento di Brema#Campagna di Francia#second world war#Seconda guerra mondiale#Wordl War Two

0 notes

Text

Ethiopian troops charge into battle against Italy during the second battle of Amba Alagi, Ethiopia, February 1936

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

The WW2 East African Campaign was won at Amba Alagi:

A recurring factor of the Italian campaigns of WW2 was that huge quantitative numbers of well-supplied Italian troops on paper were routed by far smaller numbers of British and associated forces. Amba Alagi, where 70,000 British and Ethiopian troops smashed 300,000 Italian forces and broke the core of Italian power in Ethiopia beyond repair, is a classic illustration of what this meant. Highly motivated British and associated forces conducted masterful pincer strikes against disgruntled Italian troops led by defeatist generals who'd long since lost faith in Mussolini who after a few token shots threw their hands up and surrendered en masse, preserving their lives for the duration while their counterparts in the major Axis states died for nothing.

One can make one's own conclusions on what the merits of horrors like the Siege of Budapest or Iwo Jima actually did for Japan and Germany versus 'well we're fucked, time to give up' for the Italians and the respective wisdom of masses and states.

#lightdancer comments on history#black history month#african history#world war 2#east african campaign of ww2#military history#ethiopian history#black history

0 notes

Text

"Aiutare l’Africa, con passione" la lettera del 2018 di Amedeo d'Aosta al Corriere della Sera

“Aiutare l’Africa, con passione” la lettera del 2018 di Amedeo d’Aosta al Corriere della Sera

Il Duca Amedeo di Aosta, nipote dell’eroe dell’Amba Alagi, scrisse il 25 giugno 2018 una lettera al Corriere della sera dove narra le vicissitudini della sepoltura di suo prozio Luigi Amedeo Duca degli Abruzzi, morto nel 1933 e sepolto secondo le sue volontà in Somalia. Una riflessione interessante anche sulla sua opera in quelle terre come la costituzione del Villaggio che porta il suo…

View On WordPress

#aiutiamoli a casa loro#Amba Alagi#Amedeo di Aosta#colonialismo#colonie#Duca degli Abruzzi#fascismo#immigrazione#luigi di savoia#somalia#villaggio duca degli abruzzi

0 notes

Text

• Amedeo Guillet

Amedeo Guillet was an officer of the Italian Army, he was one of the last men to have commanded cavalry in war. He was nicknamed Devil Commander, and was famous during the Italian guerrilla war in Ethiopia in 1941, 1942 and 1943.

Guillet was born in Piacenza, Italy on February 7th, 1909. Descended from a noble family from Piedmont and Capua. His parents were Franca Gandolfo and Baron Alfredo Guillet, a colonel in the Royal Carabinieri. Following his family tradition of military service, he enrolled in the Academy of Infantry and Cavalry of Modena at the age of 18, thus beginning his career in the Royal Italian army. He served in the Second Italo-Ethiopian War that prevented him from competing in equestrian events in the 1936 Summer Olympics Berlin Olympics. Guillet was wounded and decorated for bravery as commander of an indigenous cavalry unit. Guillet next fought in the Spanish Civil War serving with the 2nd CCNN Division "Fiamme Nere" at the Battle of Santander and the Battle of Teruel.

In the buildup to World War II, Prince Amedeo, Duke of Aosta gave Guillet command of the 2,500 strong Gruppo Bande Amhara, made up of recruits from throughout Italian East Africa, with six European officers and Eritrean NCOs. The core was cavalry, but the force also included camel corps and mainly Yemeni infantry. For Guillet to be given command of such a force while still only a lieutenant was a singular honour. In 1940, he was tasked to form a "Gruppo Bande a Cavallo". The "Bande a Cavallo" were native units commanded by Italian officers. Amedeo Guillet succeeded in recruiting thousands of Eritreans. His "Band", already named in the history books as "Gruppo Bande Guillet" or "Gruppo Bande Amahara a Cavallo", was distinguished for its absolute "fair play" with the local populations. Amedeo Guillet could boast of having never been betrayed, despite the fact that 5,000 Eritreans knew perfectly well who he was and where he lived. It was during this time, in the horn of Africa that the legend of a group of Eritreans with excellent fighting qualities, commanded by a notorious "Devil Commander", was born.

Guillet's most important battle happened towards the end of January 1941 at Cherù when he attacked enemy armoured units. At the end of 1940, the Allied forces faced Guillet on the road to Amba Alagi, and specifically, in the proximity of Cherù. He had been entrusted, by Amedeo Duca d'Aosta, with the task of delaying the Allied advance from the North-West. The battles and skirmishes in which this young lieutenant was a protagonist (Guillet commanded an entire brigade, notwithstanding his low rank) are highlighted in the British bulletins of war. The "devilries" that he created from day to day, almost seen as a game, explains why the British called him not only "Knight from other times" but also the Italian "Lawrence of Arabia". Horse charges with unsheathed sword, guns, incendiary and grenades against the armoured troops had a daily cadence. Official documents show that in January 1941 at Cherù "... with the task of protecting the withdrawal of the battalions... with skillful maneuver and intuition of a commander... In an entire day of furious combats on foot and horseback, he charged many times while leading his units, assaulting the preponderant adversary (in number and means) soldiers of an enemy regiment, setting tanks on fire, reaching the flank of the enemy's artilleries... although huge losses of men,... Capt. Guillet,... in a particularly difficult moment of this hard fight, guided with disregard of danger, an attack against enemy tanks with hand bombs and benzine bottles setting two on fire while a third managed to escape while in flames."

In those months many proud Italians died, including many brave Eritreans who fought without fear for a king and a people who they never saw or knew. To the end of his life, the "Devil Commander" used words of deep respect and admiration for that proud population to whom he felt indebted as a soldier, Italian, and man. He never failed to repeat that "the Eritreans are the Prussians of Africa without the defects of the Prussians". His actions served their intended purpose and saved the lives of thousands of Italians and Eritreans who withdrew in the territory better known as the Amba Alagi. At dawn, Gulliet charged against steel weapons with only swords, guns and hand bombs at a column of tanks. He passed unhurt through the British forces who were caught unaware. This action was the last cavalry charge that British forces ever faced, but it was not the final cavalry charge in Italian military history. A little more than a year later a friend of Guillet, Colonel Bettoni, launched the men and horses of the "Savoia Cavalry" against Soviet troops at Isbuchenskij. Guillet's Eritrean troops paid a high price in terms of human losses, approximately 800 died in little more than two years and, in March 1941, his forces found themselves stranded outside the Italian lines. Guillet, faithful until death to the oath to the House of Savoy, began a private war against the British. Hiding his uniform near an Italian farm, he set the region on fire at night for almost eight months. He was one of the most famous Italian "guerrilla officers" in Eritrea and northern Ethiopia during the Italian guerrilla war against the Allies occupation of the Italian East Africa.

Later in early 1942, for security reasons he changed his name in Ahmed Abdallah Al Redai, studied the Koran and looked like an authentic Arab: so when British soldiers came to capture him, he fooled them with his new identity and escaped on two occasions. After numerous adventures, including working as a water seller, Guillet was finally able to reach Yemen, where for about one year he trained soldiers and cavalrymen for the Imam's army, whose son Ahmed became a close friend. Despite the opposition of the Yemenite royal house, he succeeded in embarking incognito on a Red Cross ship repatriating sick and injured Italians and finally returned to Italy a few days before the armistice in September 1943. As soon as Guillet reached Italy he asked for Gold sovereigns, men and weapons to aid Eritrean forces. The aid would be delivered by aeroplane and enable a guerrilla campaign to be staged. But with Italy's surrender, then later joining the Allies, times had changed. Guilet was promoted to Major for his war accomplishments and worked with Major Max Harari of the 8th King's Royal Irish Hussars who was the commander of the British special unit services that tried to capture Guillet in Italian East Africa. At the end of the war, the Italian monarchy was abolished. Guillet expressed a deep desire to leave Italy. He informed Umberto II of his intentions, but the King urged him to keep serving his country, whatever form its government might take. Concluding that he could not disobey his King's command, Guillet expressed his desire to teach anthropology at university.

Following the war, Guillet entered the Italian diplomatic service where he represented Italy in Egypt, Yemen, Jordan, Morocco, and finally as ambassador to India until 1975. In 1971, he was in Morocco during an assassination attempt on the King. On June 20, 2000, he was awarded honorary citizenship by the city of Capua, which he defined as "highly coveted". On 4 November 2000, the day of the Festivity of the Armed Forces, Guillet was presented with the Knight Grand Cross of the Military Order of Italy by President Carlo Azeglio Ciampi. This is the highest military decoration in Italy. Guillet is one of the most highly decorated (both civil and military) people in Italian history. In 2001, Gulliet visited Eritrea and was met by thousands of supporters. The group included men who previously served with him as horsemen in the Italian Cavalry known as Gruppo Bande a Cavallo. The Eritrean people remembered Gulliet's efforts to help Eritrea remain independent of Ethiopia. In 2009, his 100th birthday was celebrated with a special concert at the Palazzo Barberini in Rome. Amedeo Guillet died on June 16th, 2010, in Rome at the age of 101.

#ww2#second world war#world war 2#world war ii#wwii#military history#history#italy in ww2#italian history#calvary#equestrian#guerilla warfare#eritrea#lawrence of arabia#biography

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

Battaglia di Adua

La battaglia di Adua, combattuta il 1° marzo 1896, fa parte della cosiddetta Guerra d’Abissinia, durante la quale il Regno d’Italia tentò di allargare i propri possedimenti in Africa, partendo dalla colonia Eritrea.

Grazie al deliberato fraintendimento del Trattato di Uccialli, il primo Ministro Francesco Crispi accusò Menelik II, imperatore d’Etiopia, di aver tradito i patti tra le due nazioni, trovando così il pretesto per un’aggressione.

L’esercito italiano inanellò varie sconfitte (Amba Alagi, Makallè), culminate nella disfatta di Adua, che pose fine al tentativo di invasione, a causa del quale morirono, in quel solo scontro, quasi 15mila persone.

L’intitolazione delle strade a quella località, risale in genere alla dittatura fascista, perché durante l’attacco di Mussolini all’Etiopia, nel 1936, Adua venne occupata dall’esercito italiano, e la propaganda di regime descrisse l’evento come un “riscatto” dell’umiliazione subita quarant’anni prima.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Battle of Adwa: Ethiopia deflates the myth of African inferiority on the battlefield and checks European colonialism.

The late 19th century was the height of European colonialism. The leading European colonial powers were the British and French due to their longstanding colonial traditions spanning since the 17th century, maritime prowess and martial ability. By the late 19th century, two newly united European powers Germany and Italy sought to become colonial powers as well. The primary focus of their colonialism was Africa as part of the so called Scramble for Africa with Britain and France controlling most of the continent in addition to smaller powers like Portugal and Belgium, both Germany and Italy sought colonial possessions for themselves. Germany would acquire the colonies of German East Africa, German Southwest Africa and German West Africa: Encompassing the modern nations of Burundi, Cameroon, Namibia, Tanzania, Rwanda and Togo along with parts of various other nations.

The Kingdom of Italy was left to focus their control on modern day Somalia and Eritrea in Northeast Africa acquired in 1889. On their border was one of two independent nations in Africa, the Ethiopian Empire also known as Abyssinia, the other nation free of colonial rule was Liberia, which was set up by resettled former slaves from the United States and had the diplomatic support of the US. Ethiopia for its part was a land rich in history dating back to ancient times. The united kingdom that constituted the Ethiopian Empire was formed back in the late 13th century and had existed since that date. Ethiopia was unique not only for its unified longevity but its independence having fended off Muslim invasions from nearby Arab Sultanates and even the Ottoman Empire with its nominal control over part of North Africa. It also was a religious anomaly among African nations, it was a Christian nation since the 4th century in union with the Egyptian Coptic Church and not imposed by European colonists though later Catholicism was introduced Catholic missionaries from Portugal initially before a civil war ousted a Catholic ruler and expelled all Catholics from the country. The country maintained its own blend of Orthodox Christianity, known as Ethiopian Orthodox and is considered the largest of Oriental Orthodox churches in the world today.

Since the 18th century, Ethiopia though nominally unified was de-facto decentralized under several noble princes who held essentially petty kingdoms in an time called the Era of Princes or Zemene Mesafint. Ethiopia fell into a period of relative isolation during this time, not unlike Japan during the contemporary Shogunate period and like Japan in the mid-19th century it came back into the modern world removed from isolation and through the restoration of power in the hands of a central ruler, an emperor. In Ethiopia’s case under the reign of Tewodros II from 1855-1868. Tewodros sought to unite Ethiopia once more under and did so through military conquest, subjugating the various princes and nobles who held regional control as basically warlords. Tewodros eventually succeeded and his next mission was to modernize the country. Yet he faced continual threat of rebellion and external threats in the Ottoman Empire’s control over Egypt. Tewodros wrote to Queen Victoria hoping to appeal as one Christian ruler to another to have British assistance in defense against the Islamic threat presented by the Ottomans. Britain however had economic and political reasons to ignore Ethiopia’s plea. Britain had a majority stake in the Suez Canal in Egypt and considered this a vital link its colonial empire linking Europe with its prize possession, India and felt a new Christian crusade against Islam in the Middle East and North Africa would hurt the regional economy and threaten its trade routes, namely for cotton and this route became ever more important in the wake of the American Civil War and its impact on the cotton trade, the Southern US no longer exported cotton in the way it had through slave labor, now Britain relied on India for its cotton. Secondly, the British Empire supported the Ottomans as a buffer against the expansion of the Russian Empire as part of the so called Great Game, a geopolitical struggle between Russia and Britain for control of political influence the world over. Britain was concerned Russia would move from Central Asia into South Asia and invade India, it also feared Russian expansion into the Balkans and Mediterranean. In the 1850′s in a dispute between the Second French Empire and Russia over rights of Christians within the Ottoman Empire, the Crimean War broke out and a coalition of Britain, France, the Ottoman Empire and Kingdom of Sardinia (precursor to the united Kingdom of Italy) defeated Russia and denied it a naval presence on the Black Sea. For these reasons Britain refused to upset the Ottomans and instead it angered the Ethiopians, while Ethiopia never fell to the Ottomans, it did anger the British. A group of missionaries were imprisoned by Tewodros for the lack of a British reply in a request for military assistance. This lead to a punitive expedition of the British combining European and Indian troops of the British Empire, they invaded Ethiopia and besieged the fortress of Magdala in April 1868, defeating the Ethiopians and freeing the hostages and burning the fortress as well as confiscating some wealth and artifacts. Tewodros killed himself during the battle having shot himself in the head with a pistol that was an earlier gift from Queen Victoria herself.

The British did not stay and conquer Ethiopia, preferring to return to the status quo, Ottoman control of Egypt was nominal at best and soon other threats to the Ottoman Empire deterred it from actively being able to invade and conquer Ethiopia. Ethiopia may have not been conquered but Magdala had shown it was vulnerable to European power, namely in their superior military technology and the discipline of their troops. In the coming decades Ethiopia would need to modernize its weaponry and look to Allies outside of Britain, its one major ally from Europe was in fact the great Orthodox Christian power, the Russian Empire. Bonded by mutual Orthodox Christianity and more importantly as a counter balance to British and Ottoman interests in the region, Russia agreed to provide modern military aid and training to the Ethiopians, the French would also supply the Ethiopians during the 1870′s and 1880′s.

1889 saw Menelik II, former son in law of Tewodros II become Emperor Ethiopia. Menelik introduced further modern reforms and created a new modern capital, Addis Ababa and he expanded the size of the country conquering the various surrounding peoples and nobility that Tewodros had only begun to take back land from. The same year Menelik became Emperor he signed a treaty with the new imperial-colonial power from Europe that conquered land to his east, Italy and its colony of Italian Somaliland and Eritrea. The Treaty of Wuchale essentially designated Eritrea as Italian land and in exchange they recognized Menelik as ruler of Ethiopia and neither side would harass the other militarily. However, the treaty was in two languages and the differences in language would lead to different interpretations of a single but crucial clause. The Italian version claimed that Menelik forfeited foreign affairs control to Italy, making Ethiopia a protectorate while the Amharic version claimed Ethiopia retained control of its foreign affairs but would or could consult with Italy for assistance. The different interpretations was largely by Italian design, which sought to have a pretext for future annexation of Ethiopia so as to expand its colonial control.

Menelik rejected the Italian interpretation of the treaty and after years of being unable to resolve this issue war would soon break out in 1894, starting the First Italo-Abyssinian War. Italy’s goal was to invade and annex Ethiopia, it started pressure on Ethiopia with the annexation of small territories along the border between Eritrea and Ethiopia, it also used the pretext of Eritrean rebels seeking refuge in Ethiopia as casus belli. The war began with Italian victories that lead to expeditions of conquest deep into Ethiopian territory. However, the Italians under Governor-General of Eritrea Oreste Baratieri ultimately would underestimate the Ethiopians resolve, army size and modern weaponry. At the Battle of Amba Alagi in December 1895 actually saw the Italians defeated by the Ethiopians but not completely. Nevertheless, Baratieri’s defeat led the Italian government to actually increase its spending on preventing a repeat disaster. The Italians, like most Europeans generally tended to consider all Africans as inferior to the Europeans for racial, cultural and military reasons. Generally speaking, European powers had advances in technology and full time professional armies that could defeat African tribal forces time and again with inferior technology and irregular military doctrine. Ethiopia however was relatively modern in its military stockpiles, gaining some the Russians, French and even the British and Italians themselves over the course of several years. These factors would lead to the Battle of Adwa, fought on March 1, 1896.

Baratieri resumed the campaign in 1896 and pressed toward Adwa in northern Ethiopia, Adwa was strategically vital because it controlled vital routes in that part of the country, the terrain which would a role in the upcoming battle was hilly and mountainous. The Italian forces would consist of 4 brigades a mix of Italian conscripts and colonial troops, along with African auxiliaries known as askaris from Eritrea. Their troops totaled 17,700 and 52 pieces of artillery all of which was antiquated by European standards. Their gear and logistics were also subpar for the tough terrain they were trekking. Nevertheless, the Italian leadership remained confident of victory. Baratieri was alone in thinking that as they marched and supplies dwindled it would be better to strategically retreat and fall back to Eritrea and resupply but his subordinate commanders stated this would be bad for morale, also pressure from Rome and the knowledge that he would soon be replaced for his failures led Baratieri to commit to a battle. Italians further frustrated their effort with poorly sketched and outdated maps of the region.

Menelik commanded an army of disputed size but ranging from 80,000-120,000 troops including infantry armed with modern rifles, cavalry and traditional sword and spear melee infantry along with Russian supplied artillery and a small number of Russian military advisers in their ranks under Nikolay Leontiev. With these numbers, weaponry and local knowledge of the terrain, the Ethiopians felt they could win. Though victory wasn’t a guarantee, the Italians movements weren’t exactly known and the supplies for Ethiopia’s army would soon dwindle as well forcing them to retreat or dissipate. Baratieri was aware of this and this factored into his assessment of waiting to press battle but ultimately he gave into the external pressures surrounding him.

The Italian plan called for marching three brigades supported by a reserve to press through the various mountain passes and set up on the high ground, getting a textbook military advantage where deadly crossfire would certainly undo the Ethiopians. The Italians marched out at dawn with the goal of pressing their attack that morning. The biggest concern was Italians being outflanked due to their superior numbers, so many Italians actually stayed in reserve on guard duty. Menelik was made aware of the Italian advance and he summoned his subordinates to organize their men and counter attack as soon as possible. The Italians due to the lack of good intelligence underestimated the size of the Ethiopian army and their poor maps lead to discombobulated marches of the brigades and rather than march to the high ground they hoped for, they marched straight into the Ethiopian counterattack. Furthermore, the rank and file had written letters home of bad morale prior to the battle and fear of disaster. It seems their leaderships confusion and rushed decision were now playing out their worst fears, outnumbered six to one and facing a surprisingly well equipped force caught the Italians off guard. The Ethiopians also launched their Russian mountain artillery from the very high ground the Italians had hoped would have been in their hands. Despite their poor equipment, morale and confused plans the Italians did fight bravely in many cases and inflicted many casualties repelling many Ethiopian advances over and over. However, the numbers became too great and many last stands took place, the reserves committed what they could but Baratieri himself panicked and left the battle, decreasing the morale of his troops. Overwhelmed the Italians began a confused retreat, pursued for nine miles, individual stragglers were picked off by Ethiopian troops and civilians. The defeat was resounding and Italy lost 6,000 killed, 1,500 wounded, 3,000 captured including the wounded. Many of the dead were the Eritrean askaris, who the Ethiopians considered as traitors to Ethiopia even if they were separate countries. The Ethiopians as punishment mutilated many Eritrean soldiers but cutting off a hand and foot as permanent punishment, heaps of these missing appendages were found at the battle site still months later. The Italian prisoners for their part were reputed to have been relatively well treated for the remainder of the war, despite some dying of their wounded later in captivity. Ethiopia lost nearly 4,000 killed and suffered over 8,000 wounded, meaning the battle was very bloody and costly for them as well.

The impact of the defeat would have both short term and long term consequences. In Italy, shock of its announcement resulted in protests from the general populace and riots had be to be put down by police, the Prime Minister resigned days later and Italy argued about whether to seek revenge or end the war. Menelik for his part could not pursue the Italians back to Eritrea due to his own losses and lack of supplies. He also had political foresight to see that an invasion of Italian Eritrea would galvanize Italian support for continuing the war and the likelihood was that Ethiopia couldn’t repeat Adwa and probably wouldn’t be able to sustain Italian reinforcements in greater numbers with better supplies, by maintaining a purely defensive strategy he and his nation would appear more sympathetic and political demands in Italy would switch to calls to end the war rather than gain revenge, this strategy payed off and in the October 1896 Treaty of Addis Ababa. Italy recognized the independence of Ethiopia and the Treaty of Wuchale’s repeal, meaning Ethiopia did not have to consult Italy on foreign affairs in exchange all Italian prisoners were released and Italy was actually allowed to keep some of their conquests from earlier in the war, giving the losing side some small territorial gains. Baratieri was court martialed for his performance but ultimately acquitted though he was judged incompetent for military leadership. In Russia, the victory was likewise celebrated and Russians viewed it as an act of solidarity with their fellow Orthodox Christians and as a small measure of revenge for Italian participation in the Crimean War 40 years earlier.

In the short term Ethiopia’s independence was assured, in the long term though both Europe and Africa reflected on Adwa’s implications. In Italy, Adwa became a rallying cry much like “Remember the Alamo” for Americans. In 1935, Fascist Italy was keen on expanding Italy’s colonial empire once more and under Benito Mussolini, the Italians launched a new invasion of Ethiopia, this time using modern weapons including tanks and planes, the Ethiopians stood no chance and once more their pleas for help fell to deaf ears in the League of Nations which stood powerless to stop Italy. Ethiopia would be conquered, annexed and incorporated into the new Italian Empire, to which Mussolini would say “Adwa had been avenged.” From 1936-1941, Ethiopia was occupied when the British in the midst of World War II defeated the Italians and liberated Ethiopia. In African historical memory though, especially popular among the Pan-African movement, the Battle of Adwa and Ethiopian independence by extension stands as a beacon of symbolic hope, shattering the long held myth of African inferiority to foreigners and proving that given the right circumstances, they too can triumph over colonial forces and preserve their freedom...

#ethiopia#italy#19th century#warfare#colonialism#africa#pan africanism#victorian era#military history#indepdence

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Amedeo of Savoy-Aosta, viceroy of Italian East Africa, having lunch with his staff while besieged in the mountain fortress of Amba Alagi, Ethiopia, April 1941 [2792 x 2092] Check this blog!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Amadeo de Saboya, el Duque de Hierro

ESTE ARTÍCULO FUE PUBLICADO POR PRIMERA VEZ EN EL NÚMERO 45 DE LA REVISTA ARES ENYALIUS

La siempre controvertida participación italiana en la Segunda Guerra Mundial tradicionalmente ha puesto en tela de juicio a sus generales. A diferencia de Gran Bretaña, Alemania, Estados Unidos o la Unión Soviética, Italia no ha proporcionado a la memoria colectiva un Montgomery, un von Manstein, un Patton o un Zhukov; los grandes héroes italianos de la contienda suelen ser buscados entre las filas de los soldados y los oficiales. Pero si hubiese que encontrar a uno entre los generales, el más recordado hoy en Italia probablemente sería el Príncipe Amadeo de Saboya, Duque de Aosta.

El Príncipe Amadeo de Saboya (Turín, 21 de octubre de 1898 - Nairobi, 3 de marzo de 1942) pertenecía a la segunda rama familiar de la Casa Real de Italia, la de los Duques de Aosta, de la que fue el titular durante buena parte del periodo fascista. El primer Duque de Aosta fue su abuelo Amadeo, efímero monarca español entre 1871 y 1873; su padre, Manuel Filiberto, fue durante ese breve periodo Príncipe de Asturias.

Cursó la Secundaria en el Colegio de San Andrés de Londres, y los estudios castrenses en la Nunziatella de Nápoles, la más antigua academia militar del mundo. Con dieciséis años se presentó voluntario para combatir en la Primera Guerra Mundial cuando Italia declaró la guerra al imperio de los Habsburgo. Su padre exigió que entrase en el Ejército como soldado raso, y dio instrucciones a su superior, el general Petitti di Roreto, para que no recibiese ningún privilegio. Combatió en la región del Carso, encuadrado en el Regimiento de Artillería a Caballo Voloire, y ascendió hasta el empleo de teniente al final de la contienda.

Finalizada la Gran Guerra se dedicó a explorar la Somalia Italiana en compañía de su tío Luis, Duque de los Abruzos, y el Congo Belga. También completó su formación académica, que había quedado interrumpida a causa del conflicto bélico, en Eton y Oxford, y se doctoró en Derecho por la Universidad de Palermo con una profética tesis titulada “Conceptos básicos de la relación jurídica entre los estados modernos y los pueblos indígenas de las colonias”, cuya conclusión era que la imposición de la soberanía de un estado sobre otro se justifica moralmente sólo por la mejora de las condiciones de vida del pueblo colonizado. Ya en Italia, se instaló en el bellísimo Castello di Miramare, a orillas del Adriático en Trieste, y tomó el mando del Regimiento de Artillería 29º, acuartelado en Gorizia. No obstante, descubrió que su verdadera pasión era el vuelo, y el 24 de julio de 1925 consiguió la especialidad de piloto militar.

Tras un breve servicio en las colonias como Inspector de los Grupos del Sahara, volvió a Italia y el 5 de noviembre de 1927 se casó con la princesa Ana de Orleans. Tres años después nació la primera hija, la princesa Margarita, y después de otros tres la segunda, la princesa María Cristina.

El 4 de julio de 1931 se convirtió en Duque de Aosta tras el fallecimiento de su padre (antes ostentaba el título de Duque de Apulia). Un año después se enroló en la Regia Aeronautica y participó en la Guerra de Abisinia como piloto de combate. Con el tiempo llegó a ser uno de los cuatro oficiales de la Regia Aeronautica que alcanzaron el grado de Generale d’Armata Aerea, inferior únicamente a los de Maresciallo dell’Aria (sólo hubo uno, Italo Balbo) y Primo Maresciallo dell’Impero (reservado para el Jefe del Estado y el Jefe del Gobierno, es decir, Víctor Manuel III y Benito Mussolini). En la Regia Aeronautica estuvo al mando de la 1ª División Aérea “Aquila”, cuyo cuartel general se encontraba también en Gorizia.

El 21 de octubre de 1937 abandonó su residencia de Trieste para sustituir al Mariscal Rodolfo Graziani como máxima autoridad civil y militar (Virrey) en el África Oriental, conjunto de territorios bajo soberanía italiana que incluía las colonias de Somalia y Eritrea, y el recién conquistado Imperio Etíope. Amadeo presentaba un perfil menos politizado que Graziani (un fervoroso fascista) y carecía de la fama de cruel represor que su antecesor se había ganado como “pacificador” de las colonias libias de Cirenaica y Tripolitania (no en vano fue apodado “el carnicero de Fezzan”). Es en estos meses cuando desde ciertos sectores fascistas se propone al General Franco, que casi tenía a su alcance la victoria en la Guerra Civil, que el Príncipe Amadeo fuese coronado Rey de España. El principal argumento de quienes defendían la iniciativa era que, de no haber abdicado Amadeo I en 1873, el trono español lo estaría ocupando precisamente él, como nieto primogénito. No obstante, la Casa de Saboya no respaldó esta postulación por respeto a Alfonso XIII, en ese momento exiliado en Roma bajo la protección de Víctor Manuel III. Además, en España había escaso interés en la restauración de la monarquía, y menos aún de la lejana Casa de Saboya.

El Duque de Aosta se ganó rápidamente en África el reconocimiento de los nativos, los colonos italianos y la guarnición militar. Cuando Italia declaró la guerra a Gran Bretaña y a Francia el 10 de junio de 1940, Amadeo se percató de la debilidad de las guarniciones británicas en los territorios vecinos, y lideró una ofensiva general con todas sus fuerzas disponibles sobre Sudán, Kenia y Somalia, en la que consiguió importantes avances en los dos primeros, y la conquista del tercero. Fue entonces cuando se ganó el apelativo de “el Duque de Hierro”. Contaba con unas fuerzas nada desdeñables, pero que tuvieron que combatir en varios frentes simultáneamente y completamente aisladas: unos 260.000 soldados (de los cuales casi el 70% eran tropas indígenas, incluidos los temibles askaris eritreos y dubats somalíes) organizados en dos divisiones de infantería (las mejores tropas disponibles; eran la 40ª “Cazadores de África” y la 65ª “Granaderos de Saboya”), treinta y tres brigadas coloniales, once batallones de Camisas Negras, dos compañías de tanquetas L3/35, dos de tanques medianos M11/37 y diez baterías de obuses; unos 240 aviones (los principales modelos eran bombarderos Ca.133, SM.79 y SM.81 y cazas CR.32 y CR.42); y la Flotilla del Mar Rojo, formada por siete destructores, ocho submarinos, cinco lanchas torpederas, un cañonero colonial y dos mercantes armados.

En enero de 1941 los británicos contraatacaron e hicieron retroceder a las tropas del Duque de Aosta hasta posiciones defensivas en el África Oriental. En la Batalla de Keren perdieron el control de Eritrea, incluida Massawa, la principal base naval italiana. Totalmente incomunicado con la metrópolis, mermado de suministros y rodeado por el enemigo, Amadeo ordenó la fortificación de los puntos estratégicos de Gondar, Dessie, Gimma y, especialmente, Amba Alagi, en cuyas montañas y cavernas fijó su cuartel general. Allí resistió el asedio de 9.000 británicos al mando del general Alan Cunningham y 20.000 etíopes fieles al recién llegado Haile Selassi, entre febrero y mayo, con apenas 7.000 hombres, incluidos soldados, carabineros, aviadores, marinos y tropas indígenas. El 14 de mayo recibió desde Roma la autorización para rendir la plaza, y envió al general Giovan Battista Volpini a negociar con Cunningham, pero Volpini fue asesinado por rebeldes etíopes al intentar atravesar el cerco. El día 17, con el agua y los alimentos agotados, se acordó finalmente la rendición. El Duque de Aosta dio permiso a las tropas indígenas para que regresasen a sus hogares, pero nadie abandonó Amba Alagi. El día 19 los italianos salieron finalmente de las cavernas; el Duque salió el último mientras se arriaba la bandera tricolor. Los británicos, como reconocimiento de su tenacidad, le concedieron honores militares antes de trasladarlo a un campo de prisioneros en Dònyo Sàbouk, cerca de Nairobi.

Por su tenaz resistencia recibió la más alta condecoración militar italiana, la Medalla de Oro al Valor, aunque no tuvo la posibilidad de que se la entregasen porque jamás volvió a su país: enfermo de tifus y malaria, a causa de las insalubres condiciones de la prisión, murió el 3 de marzo de 1942 en Nairobi. El título de Duque de Aosta pasó entonces a su hermano Aimón, que además era Duque de Spoleto y rey titular de Croacia con el nombre de Tomislav II, pues Amadeo, como dijimos, sólo había tenido dos hijas en su matrimonio. Fue enterrado en el Cementerio Militar Italiano de Nyeri junto a 676 de sus soldados que también perecieron en cautividad. Por lo que respecta a los que se habían quedado en África Oriental, siguieron resistiendo en sus fortalezas hasta que la última de ellas, Gondar, cayó el 11 de noviembre de 1941. No obstante, numerosos italianos (soldados que no habían sido capturados, camisas negras y colonos, apoyados por nativos eritreos y somalíes) mantuvieron una guerra de guerrillas contra los británicos hasta otoño de 1943, cuando se firmó el armisticio final entre Italia y los Aliados.

Inmediatamente después de su fallecimiento se instituyó una medalla como recompensa para todos aquellos militares, funcionarios civiles y de la Casa Real que sirvieron a sus órdenes. Como la mayoría de los receptores se encontraban prisioneros en África sólo pudo ser entregada tras la rendición italiana y el retorno de los cautivos a partir de 1945, pero no llegó concederse masivamente por dos motivos: las alusiones fascistas de su diseño (Mussolini había caído en julio de 1943) y el fin de la propia monarquía el 12 de junio de 1946. Así pues, muy pocas medallas realmente fueron entregadas. La pieza muestra en el anverso la efigie del Duque de Aosta, y en el reverso un extracto del decreto por el que se le concedía la Medalla de Oro al Valor. El texto completo decía lo siguiente:

Comandante Supremo de las Fuerzas Armadas en el África Oriental Italiana, durante doce meses de lucha feroz, aislado de la Madre Patria, rodeado por el enemigo abrumadoramente superior en fuerzas y medios, confirmó su capacidad ya probada de líder competente y heroico. Osado aviador, guía incansable de sus tropas, a las que condujo por cualquier lugar por tierra, mar y aire en victoriosas ofensivas y en tenaces defensas contra importantes adversarios. Asediado en Amba Alagi, al mando de su grupo de guerreros resistió más allá de los límites de las posibilidades humanas, en un titánico esfuerzo que se ganó la admiración del propio enemigo. Fiel continuador de las tradiciones militares de la Casa de Saboya e símbolo de la virtud romana de la Italia Imperial y Fascista en el África Oriental Italiana, desde el junio de 1940 hasta el 18 de mayo de 1941.

Amadeo, Duque de Aosta, es considerado uno de los generales italianos más brillantes no sólo de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, sino también de todo el siglo XX. Su impresionante hoja de servicios registra las siguientes condecoraciones:

- Caballero de la Orden de la Anunziata

- Gran Cruz de la Orden de San Mauricio y San Lázaro

- Gran Cruz de la Orden de la Corona de Italia

- Caballero de la Orden Civil de Saboya

- Oficial de la Orden Militar de Saboya

- Medalla de Oro al Valor Militar

- Medalla de Plata al Valor Militar

- Cruz al Mérito de Guerra

- Medalla por el mando prolongado en el Ejército (10 años)

- Medalla por el mando prolongado en la Aviación (10 años)

- Medalla conmemorativa interaliada de la victoria en la Primera Guerra Mundial.

- Medalla conmemorativa de la Guerra italo-austriaca, con pasador de 4 años en el frente.

- Medalla conmemorativa por la participación en la Guerra de Etiopía.

- Medalla por el Quincuagésimo Aniversario de la Unidad de Italia.

- Medalla de Oro al Mérito por la Salud Pública.

- Cruz de Guerra de la República Francesa

- Caballero de Honor de la Orden Militar y Hospitalaria de San Juan de Jerusalén, Rodas y Malta.

Más allá del plano militar, Amadeo fue un administrador colonial benevolente y respetuoso con la población nativa, y un gran impulsor del desarrollo de las infraestructuras en el África Oriental Italiana. Como reconocimiento por el buen trato otorgado a los etíopes durante su periodo como Virrey en Addis Abeba, Haile Selassie invitó a visitar Etiopía en los años sesenta a su sobrino Amadeo, actual Duque de Aosta, en un notable gesto de reconciliación.

En 1952 fue consagrada la Iglesia Memorial de Guerra de Nyeri, mandada construir por el Estado Italiano en Kenya. Su interior alberga los restos de los 676 soldados muertos en cautiverio, y frente al altar se situó el sepulcro del Duque de Aosta. En el exterior están enterrados los soldados somalíes y eritreos musulmanes que perecieron a su servicio, siguiendo los dictados del ritual islámico.

Y en Gorizia puede visitarse un monumento levantado en su honor en 1962. Fue inaugurado el 4 de noviembre de ese año por Antonio Segni, Presidente de la República, lo cual es una muestra del reconocimiento que el Duque se ganó en su país, incluso 14 años después del fin de la monarquía, estando incluso vigente la ley republicana que prohibía a los varones de la Casa de Saboya regresar a Italia.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Amba Alagi 16 maggio 1941, la morte del generale Giovan Battista Volpini

Amba Alagi 16 maggio 1941, la morte del generale Giovan Battista Volpini

Sono stato privato, dal destino, dell’amico, del saggio consigliere, del compagno che da sedici anni divideva con me la vita, con i suoi giorni tristi e lieti. La tragica sorte ha fatto cadere Volpini quando il silenzio delle artiglierie nemiche segnava già la fine della guerra. […] Non mi sono ancora riavuto dal colpo e non riesco a frenare il mio dolore. Mi sento terribilmente solo ed affronto…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

A proposito dell'adunata degli alpini a Rimini e delle denunce fatte da donne e ragazze per le molestie subite da questi, vi invito a leggere questo post sui crimini di guerra commessi dagli Alpini.

Il corpo degli alpini venne fondato il 15 ottobre 1872. L’alpino viene descritto come “valoroso difensore della Patria dal barbaro invasore austriaco”. Peccato che le cose erano al contrario: nel 1911-12, l’Italia partecipò alla guerra per la conquista della Libia contro la Turchia.

Nel 1915, quando l’Italia dichiarò guerra all’Austria-Ungheria, gli alpini della Divisione Pusteria occuparono il Sud Tirolo (l’attuale Trentino Alto-Adige).

L’Associazione Nazionale degli Alpini venne creata nel 1919 e l’associazione si associò direttamente alla dittatura fascista. Il regime creò il mito dell’alpino.

Nel 1935-36, l’Italia aggredisce l’Etiopia dove l’esercito utilizzò armi chimiche contro la popolazione locale. La Divisione Pusteria combatté battaglie più cruente di Tigrai, Amba Aradan, Amba Alagi e Tembien ed ai massacri di Mai Ceu e al lago Ashangi. Anche dopo la guerra, gli alpini di tale divisione commisero crimini odiosi. Il regime fascista creò a Bruneck, oggi Brunico, un monumento per glorificare gli alpini caduti in guerra, monumento ancora difeso ma ritenuto giustamente umiliante per i sudtirolesi.

Con lo scoppio della seconda guerra mondiale, la Divisione Pusteria aggredì la Francia e poi l’URSS. Il 26 gennaio 1943 si combatté la cruenta battaglia di Nikolaevka. Gli alpini appoggiavano l’occupazione nazista in Unione Sovietica. Dei 57 mila alpini ne tornarono solo 11 mila che non solo erano vittime, ma anche dei colpevoli dei crimini di guerra commessi lì. Il fascismo strumentalizzò il loro “sacrificio”, De Gasperi fece di tutto per non far processare i militari italiani, gli alpini compresi, per i loro crimini commessi.

Ancora oggi gli alpini non si pentono dei crimini commessi in tempi di guerra e mostrano ancora una volta i loro sentimenti nazionalisti e razzisti. Nel Sud Tirolo, gli alpini si comportano come forze di occupazione.

Matteo Salvini dice “Viva gli alpini!” alla notizia delle molestie da parte loro verso donne e ragazze al raduno a Rimini. Il Governatore dell’Emilia Romagna, del PD, li onora pure. Tali episodi si sono ripetuti nelle passate adunate degli alpini, ma i politici, di destra e di sinistra, non ne fanno un problema minimizzando o ipocritamente prendendo distanze senza prendere provvedimenti drastici.

E allora quando ci sono state violenze e molestie di massa verso ragazze nel capodanno a Milano dove figli di immigrati sono coinvolti hanno alzato la voce, perché se lo fanno dei militari italiani in un’adunata tutto viene minimizzato con giustificazioni e prese di distanza ipocrite o addirittura arrivare ad accusare di “esagerazione” e di “vilipendio” coloro che denunciano le molestie subite? Perché la donna deve essere sempre di “proprietà” dell’uomo italico, bianco, cristiano-cattolico, etero, cisgender. Perché gli italiani sono “brava gente”.

Intanto il governo ha istituito la giornata nazionale degli alpini da celebrare ogni 26 gennaio, data che ricorre la battaglia di Nikolaevka nel 1943 quando l'Italia affiancava la Germania nazista. Ciò significa che l'Italia è ancora un paese a memoria corta e che mai farà i propri conti con la storia.

#italia#molestie#alpini#guerra#crimini di guerra#Rimini#donne#maschilismo#sessismo#fascismo#razzismo#politica#Matteo Salvini#destra#sinistra#lega#PD#nazismo

1 note

·

View note

Quote

One could not better indicate the style which a true leader possesses, even when his own life is at risk. It is said that among the last words uttered by the Duke of Aosta, the hero of Amba Alagi, were these: 'I would have preferred to die fighting, out there among my men. But perhaps this is vanity. A man should know how to die even in a hospital bed.' There is no true greatness, save in an impersonality, devoid of vanity, of sentimentalisms, of exhibitionisms, and of rhetoric. Only that which is personal in a true, higher sense is liberated and permitted to shine. And wherever such a man must lead or serve as an example, it will be an entirely different kind of bond which so tightly unites the man who commands with the man who obeys -- bonds that no longer appeal only to the irrational, emotional part of the human soul, the part which is ever open to suggestion.

Julius Evola, “Hierarchy and Personality.”

#Ideal Man#Heroic Man#Heroic#individuality#Prince Amedeo Duke of Aosta#Kingdom of Italy#Viceroy of Italian East Africa

0 notes

Text

Appello dell'ass. Pinter per salvaguardare la tomba di Oreste Baratieri

Appello dell’ass. Pinter per salvaguardare la tomba di Oreste Baratieri

L’anniversario domenica 1° marzo del 125° del “disastro di Adua” (1896-2020/21), la più grande battaglia coloniale della storia moderna, richiama all’ordine il cimelio storico giacente in Arco: la tomba del comandante della spedizione nella colonia italiana, Oreste Baratieri, sepolto nel 1901 ad Arco. Oreste Baratieri, nato a Condino nel 1841, sfortunato comandante della spedizione italiana in…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Amedeo de Saboya-Aosta, virrey del África oriental italiana, almorzando con su personal mientras estaba asediado en la fortaleza de montaña de Amba Alagi, Etiopía, abril de 1941 https://www.instagram.com/p/B7yoLo2At1U/?igshid=d8s74bjh0brf

0 notes

Text

ADUA (1° marzo 1896)

New Post has been published on https://www.aneddoticamagazine.com/it/adua-1-marzo-1896/

ADUA (1° marzo 1896)

Ricorre oggi il 118° anniversario della battaglia di Adua, sicuramente il maggiore disastro subito da un esercito europeo in Africa, superiore anche a quello inglese di Isandlwana (1879). Il balbettante colonialismo italiano, che si era affacciato nel Corno d’Africa agli inizi degli anni Ottanta dell’Ottocento, privo di un’ideologia, di strumenti che lo sostanziassero e – come sempre nel nostro Paese – di una classe dirigente che fosse all’altezza del compito, si distinse soprattutto per miopia politica, modestia di obiettivi, grettezza di visioni. Fu una specie di “atto di presenza”, tanto per dimostrare alle altre potenze europee che anche noi avevamo un “piede in Africa”. Ottusa come sempre, la nostra classe dirigente non aveva altri obiettivi se non quello di tramandare se stessa e, se anche qua e là non mancavano le individualità di eccellenza, come lo stesso primo ministro Francesco Crispi, esse ovviamente sparivano nel “mare magnum” della sufficienza, del pressapochismo, della sottovalutazione razzista del nemico. Una presenza coloniale nel Corno d’Africa avrebbe dovuto guardare non verso l’interno, ma verso le vie d’acqua che collegavano i domini asiatici dell’impero britannico al Mediterraneo, ma per fare ciò sarebbe servita una cultura strategica che da noi non è mai esistita e, quando c’è stata, è stata disprezzata. Tutto si risolse così nella stracca imitazione di quello che facevano potenze coloniali più forti, le quali, ovviamente, non stettero con le mani in mano per cercare di bloccare le velleità italiane. La nostra presenza militare in Eritrea, mai troppo felice e incisiva, suscitò la reazione dell’impero etiopico, guidato da Menelik, quando cominciò a risultare troppo forte. Nessuno, a Roma, si rese conto che l’imperatore abissino era in grado di schierare un esercito di oltre centomila uomini e così, anche se le forze coloniali italiane continuarono a stuzzicarlo, raramente il nostro contingente arrivò a sfiorare le ventimila unità. Adua rappresentò il tragico punto di giunzione di tutti questi errori: per indurre gli abissini allo scontro, le forze italiane vennero fatte avanzare in modo scoordinato nella conca di Adua e, costrette ad affrontare il nemico in una proporzione di 5-6 a 1, andarono incontro a un tragico disastro: dei circa 18.000 partecipanti alla battaglia (tra reparti nazionali e indigeni), si dovettero registrare dai 5 ai 7.000 morti, 1.500 feriti, almeno 2.000 prigionieri. Un disastro di grandi proporzioni, che colpì al cuore il nascente colonialismo italiano e che ci espose a una pessima figura a livello europeo, dove confermammo il giudizio già molto diffuso su di noi: una classe politica non all’altezza, una classe militare misoneista e autoreferenziale, un “sistema Paese” incapace di “tenere” di fronte a una sconfitta, per quanto grave, e pronto a scagliarsi in recriminazioni, accuse e controaccuse, invece che fare fronte comune, riprendersi dalla sconfitta e migliorare la propria immagine. Adua viene dopo Custoza (1848 e 1866), dopo Lissa (1866), Dogali (1887), Amba Alagi (1895), e precede Caporetto (1917) e l’8 settembre 1943. Tutti i popoli, nel corso della loro storia, hanno subito sconfitte più o meno gravi, e ci hanno riflettuto su, per evitare che si ripetessero. Noi abbiamo continuato a fare tutto esattamente come prima, perché il nostro elevato livello di individualismo, nel mentre produceva eccellenze assolute, ha lasciato – a livello politico e culturale – troppo spazio ai mediocri, al formarsi di una metapolitica cialtronesca, autoreferenziale e soddisfatta di sé, desiderosa di tutto meno che di riflettere sui propri errori, anzi spesso addirittura incline a compiacersene. Così, le Adue, le Caporetto e gli 8 settembre tendono a riprodursi a infinito… “Quos perdere vult, Deus dementat”…

0 notes

Photo

The Duke of Aosta, viceroy of Italian East Africa, having lunch with his staff while besieged by Commonwealth and Ethiopian troops in Amba Alagi, Ethiopia, April 1941. Amba Alagi fell on 19 May 1941. [2792 x 2092] Check this blog!

6 notes

·

View notes