#Aeneas the Foreigner

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

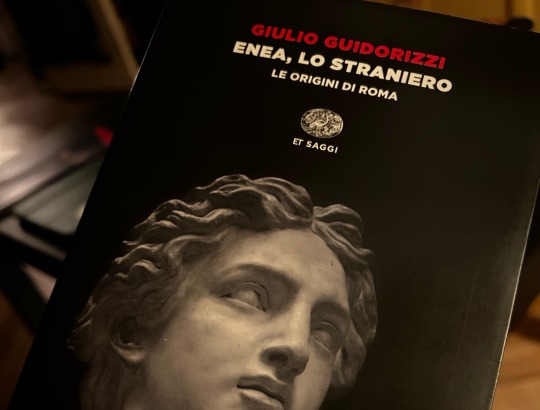

Ok so October is nearly over and my self imposed reading list was way too ambitious for a burnt-out pseudo intellectual with multiple bullshit jobs who hasn’t seriously used her “school brain” in a decade, but I DID finish this one off my list. (I also read a few trashy novels and a bit of Maurizio Bettini, doomscrolled the news, and played Pentiment three times.) It’s in Italian, but I’m posting about it in English because I’m tired and this is the internet. Hey Einaudi editore, pay me to translate it and everyone goes home happy.

Anyway, I - mostly liked it? Appreciated it? Am glad for its existence? It’s basically a prose retelling of the Aeneid, fairly short and very accessible, which is something we don’t really have many examples of. (Contrast that with the Odyssey - I remember reading about ten different kids’ and YA retellings of it back in the day.) It’s a good introduction to the story, especially for someone who hasn’t read the poem, doesn’t remember it from school or (hi) didn’t get to go to a school where they cared to teach Latin literature.

The author emphasizes that Aeneas is a refugee, that war is hell, that all this suffering and bloodshed is a tragedy - and that he and the Trojans are “foreign invaders” on the shores of Latium. He doesn’t make the slightest excuse for him regarding what he did to Dido, but also doesn’t step in as the author to moralize about it: he just focuses his lens on Dido and gives her dignity and agency, and lets her speak for herself. Similarly, he describes Turnus and Lavinia’s early courtship in a very sweet and charming way, and gives the spotlight later to Amata as she expresses her abject horror at the way Latinus has simply bartered Lavinia away to some random foreigner. He writes with a light touch, a spare style, telling the story simply and letting it speak for itself. Often this works well, other times I wish he sank his teeth in a bit more.

He almost completely removes the gods and their machinations and bickering from the plot. That’s a deliberate artistic choice to focus on the human element of the story, which I respect. It forces us to see pius Aeneas as more man than demigod, which is probably necessary for the modern mind and a useful perspective on the story, a corrective even. But I’m not sure I *like* it.

When I bought this book I expected it to be more of a critical essay on the idea of Aeneas-as-foreign-refugee and its implications for Virgil’s intentions with the poem and its reception from Augustan times until today. It is not that. I like what it is, I think?

But sometimes it left me feeling unsatisfied - so much of the Aeneid is lost when you translate it, either from Latin to another language or from poetry to prose. And this is me talking - I can *barely* read Latin right now, I’ve only had a few little tastes of the real Aeneid and have read several translations, and have still fallen head over heels in love with it - I can’t imagine the impact it will have on me when I can completely read it in the original. I might never recover, and I’ll just turn into some sort of ecstatic mystic madwoman, wandering the banks of the Tiber for centuries, accosting passersby to harangue them about no, but actually listen to the SOUND of this line!

Anyway. Good book, enjoyed it, glad it exists, appreciate its focus on the human element, good place to re-boot my rusty brain, makes me want to study and read more. EXCEPT:

One unforgivable thing.

He changes the bloody ending.

We don’t see Aeneas murder Turnus. We don’t get that shocking, abrupt, “Virgil throws down his pen in disgust and walks away” ending. The author doesn’t even do one of his inline professorial digressions about it that he has previously used to great effect.

Instead he does this cheesy Hollywood zoom-out and pan-over, describing concentric circles of Latins and Trojans and Rutulians and Etruscans who have all stopped fighting to watch the duel between Aeneas and Turnus. Ok, fine, cool visual. But then Aeneas doesn’t kill him “on-screen.” He raises his sword in the air and yells “Now we are one people!” which is just……not in the text.

I liked this book. I appreciated this book. It has moments of real beauty, interesting digressions on Roman rituals and pre-Roman Italy, and the removal of the “divine” element from the story adds enough back to our modern perspective that it’s worth it, even if I might not have done the same thing - the author is also a famous and successful classicist and I’m some schmuck on the internet, so whaddya gonna do. But the ending feels like a huge cop-out and left a weird taste in my mouth.

Now back to Caecelius in his horto so maybe I can read the real thing someday before I fucking die.

#laeta takes herself to school#publius vergilius maro#aeneidblogging#I enjoyed this book and it also disappointed me#Italian books#Aeneas the Foreigner#enea lo straniero

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The humans in Greek Mythology are the mega rich and powerful:

In my college classes people are often shocked when I tell them my favorite part of Greek mythology is the gods themselves and I'm not a big fan of the humans.

99% of my classmates prefer the humans in mythos, especially the ones that stick it to the gods like Sisyphus and feel bad for humans like Kassandra and Helen who have been wronged by the gods because "they're just like us." My classmates and teachers hate the gods and don't understand why anyone in modern times would want to worship such violent and selfish beings whenever I point out there are still people who worship them. They hold onto the idea that people in mythology embody the human experience of being oppressed by terrible gods and fate and we should feel bad for them because "they're human just like us" but they forget that the people in Greek Mythology are NOT just like us. They are more relatable to medieval royalty, colonizers and ultra rich politicians who make laws and decisions on wars and the fates of others, especially the poor and the very vulnerable.

Every hero or important human in Greek Mythology is either some form of royalty or mega rich politician/priest-priestess (of course this is with the exception of people who are explicitly stated to be poor like the old married couple in the myth where Zeus and Hermes pretend to be panhandlers). All of them have an ancient Greek lifestyle more relatable to Vladimir Putin, Donald Trump, and especially to British royalty during the British empire, than the average person.

All of them.

Odysseus, Patroclus, Theseus, Helen of Troy, Kassandra, Diomedes, Agamemnon, Perseus, Hercules, Aeneas, Paris, Any human who has a divine parent or is related to one, etc. Although sometimes the story omits it, it is heavily implied that these are people who own hundreds or even thousands of slaves, very poor farmers and the tiny barely there working class as royal subjects.

They are the ones who make laws and whose decisions massively affect the fates of so many people. So no, they can't just be forgiven for some little whim, because that little whim affects the literal lives of everyone under their rule. By being spoiled they've just risked the lives of thousands of people and possibly even gotten them killed like when Odysseus' audacity got every single slave and soldier in his ships killed or when Patroclus as a kid got upset and killed another kid for beating him at a game. (A normal person wouldn't kill another person just for winning a game but royalty and those who think they're above the law do it all the time, plus the class status of the child wasn't mentioned but the way he didn't think he'd get in trouble implies the kid was of lower class, possibly the child of a slave or a foreign merchant.)

The gods get a bad reputation for punishing the humans in mythology but, if not them, who else is going to keep them accountable when they are the law?

And whose to say the humans beneath them weren't praying to the gods in order to keep their masters in check?

Apollo is the god in charge of freeing slaves, Zeus is the god of refugees, immigrants and homeless people, Ares is the protector of women, Artemis protects children, Aphrodite is the goddess of the LGBT community, Hephaestus takes care of the disabled, etc. It wouldn't be surprising if the gods are punishing the ultra rich and powerful in these myths because the humans under their rulership prayed and sent them as they did historically.

Every time someone asks me if I feel bad for a human character in a myth, I think about the many lives affected by the decision that one human character made and if I'm being completely honest, I too would pray to the gods and ask them to please punish them so they can make more careful decisions in the future because:

They are not just like us.

We are the farmers, a lot of our ancestors were slaves, we are the vulnerable being eaten by capitalism and destroyed by the violence colonialism created. We are the poor subjects that can only pray and hope the gods will come and correct whatever selfish behavior the royal house and mega rich politicians are doing above us.

And that's why I pray to the gods, because in modern times I'm dealing with modern Agamemnons who would kill whatever family members they have to in order to reach their end goal, I'm dealing with everyday modern Achilles who would rather see their own side die because they couldn't keep their favorite toy and would gladly watch their subjects die if it means they eventually get their way. The ones that let capitalism eat their country and it's citizens alive so long as it makes them more money. These are our modern "demigods," politicians who swear they are so close to God that they know what he wants and so they pass laws that benefit only them and claim these laws are ordained by God due to their close connection just like how Achilles can speak to the gods because of his demigod status via his mother.

Look at the news, these are humans that would be mythical characters getting punished by Greek gods which is why anything Greco-Roman is jealousy guarded by the rich and powerful and is inaccessible to modern worshippers because Ivy League schools like Harvard and Cambridge make sure to keep it that way. That's what we're dealing with. These are the humans these mythical beings would be because:

In our modern times the humans in mythos would be the politicians and mega rich that are currently ruining our society and trying to turn it into a world where only the rich can manipulate wars and laws, just like they do in mythology.

Fuck them.

I literally have so much more to add about my disdain for them and I didn't even touch on the obvious ancient Greek propaganda.

544 notes

·

View notes

Note

I HAVE ARRIVED TO PUSH THE DIOMEDES AND AENEAS ITALY FLING AGENDA

Idk smth abt the second strongest Achaean and the second strongest Trojan meeting again in a place of refuge after both have been driven from their respective countries and finding solace in each other is, dare I say it, kinda tender. Like these r guys who have fought each other for years on the battlefield, in a way they know the other intimately in a way not many do. They were seen as each other's counterpart, and only knew the other in an environment of battle and bloodshed. Now they relearn who the other is in a tempestuous peace, except Diomedes has never truly known peace and still seeks out the warm, familiar comfort of war. Meanwhile Aeneas is "going through it" ™️ and has the weight and hopes of his people resting on his shoulders. It is up to him to ensure the remaining Trojans do not simply become a remnant of a war long past, a cautionary tale about the ephemeral nature of the gods (waitt Aeneas x Apollo, lowkey let me cook but that's for another ask).

Then they meet again years later in a place neither of them would have imagined they'd be.

And both of them r so angry, and grieving, and there's so much emotion and maybe not all of its negative. They have seen each other's worst, they look into the other's eyes and know that there is zero expectation for grandeur or dependability. They can be messy, and upset, and cruel and the other person would react with the same exact intensity and maybe that's what they need. They don't want the soft touches of love and care (bez deep down it hurts for someone to treat them preciously), but for someone to dig their nails into and scar to leave proof of their existence, someone they can press into until they don't know where one of them begins and the other ends. Except they're soo similar, and the longer they spend together the more they begin to notice and cherish those differences.

Also the angst of Diomedes driving Aeneas from his home, only for Diomedes to be driven to exile by Aphrodite's vengeance. Except Diomedes stabbed Aphrodite after she saved Aeneas from death by Diomedes's hand (Aeneas is very babygirl coded, like he rlly was getting the princess treatment getting carried by Aphrodite and Apollo- HEAR ME OUT 😳) and

Diomedes helped burn his city to the ground.

They both lost everything and the other person had a hand in it. Do Diomedes and Aeneas look into eachothers eyes and see all they lost staring back at them? Do their failures haunt them through the contours of the other's face? Is every scar they run a gentle hand across a reminder of all they couldn't save?

Most importantly, it's funny. Like Aphrodite rily did all that for what. Like she systematically planned this man's downfall, causing Diomedes' wife to be unfaithful, which in turn made him lose his throne and be exiled to some foreign land. And then he shows up years later in a romantic relationship with her baby boy, and she's the GODDESS OF LOVE but didn't see this coming. And she has a moment where she goes

"..wait why does it kinda eat tho" and instantly hates herself for it bez she can tell Diomedes and Aeneas genuinely care for eachother in some kinda messed up way, and Aeneas has already lost so much and she can't be the reason he loses even more, and so she doesn't do anything except silently seethe in the corner.

It's that one consent meme where it's like "isn't there someone you forgot to ask." EXCEPT THAT SOMEONE IS APHRODITE AND AENEAS SHE EXPECTED BETTER. Also Diomedes stole Aeneas' horses 🫶.

Thank you for attending my ted talk.

THANK YOU FOR THIS

(I saw this when I was half asleep, and for some reason I ended up dreaming of diomedes and aeneas as cats fighting in Italia, so i was really confused when i was re-reading this and couldn't find the cats😭😭😭)

aeneas is such an angsty character, every mention of him i come across is sorrow after sorrow - his wife dies, his city burns down, hera is hunting him - like does he get a break?

i really really like them meeting in Italia, which like you said has become a place of refuge, and naturally both of them have so much pent up rage and grief within them, the deep down it hurts for someone to treat them preciously breaks my heart but it makes so much sense with these two, they are shouldering so much rn. and they're literally the definition of enemies to lovers, and naturally aphrodite sees this, her only problem is that diomedes javelin threw a spear at her, and she in turn broke his marriage for it.

I mean for me personally it always feels like the two of them would be such a poigant reminder for each other of the war and what they lost because of it - but i do see the vision, you're winning me over with this one i fear.

also i love the idea of aphrodite just seething in a corner its so funny to me.

also this is literally how I pictured them btw:

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another point to add on my "why Numenor is actually Troy” + Rome

ENEIAS(Aeneas)/ELENDIL

Eneias(Aeneas) was a survivor from Troy, also from a "noble line" and he was said to be Aphrodite's son. He was one of the most famous Trojan leaders, he was also married to one of the princess of Troy. He got saved by the gods in many occasions and was advised by his mother to leave Troy with his family because the city would fall and his destiny was to carry Troy's greatness to other lands. Sounds way too much like Amandil and Elendil. It also sound too much like what Miriel said on season one "Numenor will return" and what she said in the previous episode about him being kinda like the future of Numenor.

On the Roman sequel, Eneias(Aeneas) left Troy with his family, wife, father and son, some soldiers and religious figures. During the trip, his wife disappeared without leaving any signs but he decided to continue the journey. Eneias(Aeneas) then decides to ask for Apollo's help, and Apollo says to him that he should go to the original land of his family.

Eneias, later, also turns the lover of a Queen, but he leaves her in order to build the city.

TAR PALANTIR/TAR MIRIEL/ CASSANDRA

Cassandra was one of the princess of Troy, who had been gifted and cursed with the power of prophecies. She saw the fall of Troy, was considered crazy and they locked her in a tower. She also predicted that Troy would return. Both of them, father and daughter, resemble Cassandra on the

"I see it, I try to warn people about it and they lock me in a tower, saying that I am crazy" and that was kinda of what happened to Palantir. They were both gifted in terms of seeing it, but people don't believe them and they can't act on it.

Cassandra and Eneias Aeneas) are also said to be cousins...we know that both Miriel and Elendil are from the same lineage.

CREUSA/MIRIEL

Creusa was one of the princess of Troy, married to Eneias (Aeneas) and there are three (at least that I know about) versions of her after the fall of Troy.

1 - Left the city, but disappeared.

Aeneas went out to look for her even though it was a risk, but she was dead and appeared to him as a ghost, saying that she was happy to be free and to have escaped slavery, and that he would find his Reign and a regal wife. She also said she was happy to follow the goddess.

2 - Was held captive and turned into a slave by the Greeks.

3 - Never left Troy and died there.

LAVINIA/MIRIEL/ESTRID

Lavinia was also a princess, but from another country. Her hand was promised to a man, but the oracle that her father had told her that she should marry a foreigner. A war started be of this and Lavinia and Eneias(Aeneas) created a city with the survivors.

LAVINIA/CREUSA MEANING

Creusa means Princess, Queen or the one that rules.

Lavinia means mother (or Legendary Mother) of the Roman people...

Yeah, I'm spiraling.

#lord of the rings#rings of power#the rings of power#elendil x miriel#mirendil#elendil#miriel x elendil#miriel#numenor#tar miriel#elendil the tall#amandil#isildur#estrid#tar palantir#cassandra of troy#Troy#rome#Aeneas#creusa#lavinia

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Read a paper on the third Homeric Hymn (Aphrodite's long hymn) the other day, and I've been musing on Aphrodite, her ability to 'cast sweet desire' into the hearts of people, and agency. Not sure this will have any insight, I'm just trying to think out loud, basically, but -

On the one hand, obviously the instances we know of where someone or other gets cursed/deliberately struck with desire is a specific and forcible/foreign sort of experience.

On the other, where does the line (is there a line?) go between Aphrodite as the origin and cause of all sexual(-romantic) feelings and desire, in general, and Aphrodite as deliberately forcing someone to fall in love/desire with another person?

Is each and every case of such a spell a wholly foreign-to-the-person desire, something they wouldn't have at all felt otherwise, or is it (sometimes) bringing out what could be/is there and making it impossible to ignore?

In the hymn, Zeus first strikes Aphrodite with desire for Anchises, and then Aphrodite herself does the same to Anchises, for her.

The layers to the question of agency and consent and whatnot are of course many, here, if we should strictly look at this from a modern lens (at the very least Aphrodite commits rape by deception). On the other hand it'd be somewhat wrong to look at it in such terms, I think.

Neither Aphrodite nor Anchises are turned into unthinking sex beasts who fall upon the object of their desire with the need to screw, and nothing more. Aphrodite plans out her approach, and goes to very deliberate effort to gain what she (now) wants in a way that will be as free of stress/fear for Anchises (in the moment, before her revealing herself) as it possibly can be. Anchises, in turn, also takes steps to assure himself this strange "girl" is someone he actually is "allowed" to have sex with - that is, that she is mortal, and not divine. (Even if we allow that he does want the answer to be 'yes', and thus is probably an even easier target for Aphrodite's deceptions than he might otherwise have been.)

The paper I read points out that we have a possibility that Anchises is actually asking for immortality (and thus to be able to keep having a relationship with Aphrodite), and that Aphrodite might want this too (and thus mirroring Anchises desire) but then steps away from that. And this is after they have satisfied each of their love/desire "delusions". And the Bibliotheke gives her and Anchises a second son, who, given that Aphrodite names only Aeneas in the Hymn, must have been conceived at a later date if we acknowledge this variant, so they clearly still desire each other. Is it natural, at this point, then?

Zeus' part in this is his act of turning Aphrodite's powers against her (the paper suggested he might be able to do this not just because he's the current ruler of the cosmos, but, as the Hymn uses that genealogy, because he's Aphrodite's father), as revenge for her doing the same to him, many times. This is probably meant in a general sense, but - later tradition had Zeus be forcibly induced to at least some of his liaisons, as the Dionysiaca shows.

But is he helpless, someone who is being used and have no agency?

I think I can begin to see what is meant by that even if a character is under divine compulsion, they have responsibility for themselves. What matters is what they do, not whether the desire is entirely natural to them or not.

We're not talking sex pollen or omegaverse-levels of heat/rut need to have sex, really.

Basically all characters we see impelled in this way still have agency to (attempt to) resist, to reason with themselves and to decide how to act.

Phaedra in (the surviving version) Euprides' Hippolytus' play has been suffering for months, maybe more than a year, before the tragedy goes down - and this because Aphrodite meddles more, not from her initial awakening of that desire. (And, as a side point, considering that Euripides has Hippolytus raised by Pittheus, so Phaedra hasn't even spent every day for however many days around a small child who's grown up into a beautiful young man. She's seen him only briefly, if at all, until the moment she sees him when she's struck - is it impossible that even a sliver of that attraction is her own entirely?) Seneca's version of this play has Phaedra shameless instead of struggling, already having given in, and that does lend a different look, but given that we know it's perfectly possible to resist and even choose death (Phaedra is just pre-empted out of her chance to do this before tragedy strikes and she still also goes through with it).

Pasiphae does not launch herself at the bull, either. (Though here it's usually Poseidon, and not Aphrodite, striking her with the desire.) She may have resisted, and we don't know how long she might have been thought of as doing so, since we don't have any (surviving) text that touches on this. If one wants to look at it that way, she even makes sure her indiscretion might have gone unnoticed, thanks to Daidalos' contraption. Unfortunately she sleeps with an animal sent by a god, so it's not odd her precaution is foiled by a result that would otherwise be impossible.

We don't actually know how the oldest sources that did/might have touched on Helen and her meeting with Paris portrayed this. We don't know what sort of influence Aphrodite exerted, or in what way, and this is quite necessary to be able to say anything about it. The later sources that actually show this either have no gods involved (because it's "realistic"), or if the gods still exist, no obvious divine interference (like Ovid's Heroides and Colluthus' Abduction of Helen).

Helen talking of delusion/madness in the Odyssey doesn't really tell us anything, since this could be either actual forcible influence of some kind, or just a generalized way to talk about love-desire given the way the Ancient Greeks conceived of it. The Iliad is ambiguous on the matter, and there is certainly no divine influence of the sort we're talking about here at play in Helen and Aphrodite's scene - at best, simple wingmanning and flirting-by-proxy, in the way Aphrodite presents Paris and Helen acknowledges this is exactly what it is (seduction) and she reacts to it, too.

Going back to Zeus and the Iliad, where he unquestionably actually is under a forcible influence that cannot be denied (Aphrodite's belt/girdle), that is one of the closest of "unthinking sex beast" reaction we have. He is singularly focused on getting Hera to sleep with him right then and there, and while it shares some similarities with the versions where Phaedra has abandoned her inhibition/shame, she's more aware of that than Zeus is, while under the influence of the girdle.

The possibility of self-awareness and resistance, and ability to reason and plan, even in the grip of being struck by a deliberate influence makes the whole thing a lot more nuanced than we might first think it is, I feel like.

(Not really touching on Medea here in the versions of the Argonautica we have; I have no idea if we should categorize Eros/Cupid's influence as somehow different in kind/degree/ability from Aphrodite's or not, first of all. Second, the fact that Aphrodite seems to "lose" the ability to strike desire into people by herself and needs Eros/Cupid to do so in later sources is curious, and, again, feels like it'd be needed to be looked at as a separate thing.)

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm going to have to leave Tumblr to go do something, but first I want to share this before I forget:

By the side of what is called the Hippodamium is a semicircular stone pedestal, and on it are Zeus, Thetis, and Day entreating Zeus on behalf of her children. These are on the middle of the pedestal. There are Achilles and Memnon, one at either edge of the pedestal, representing a pair of combatants in position. There are other pairs similarly opposed, foreigner against Greek: Odysseus opposed to Helenus, reputed to be the cleverest men in the respective armies; Alexander and Menelaus, in virtue of their ancient feud; Aeneas and Diomedes, and Deiphobus and Ajax son of Telamon.

Description of Greece, 5.22.2. Translation by W.H.S Jones.

As Pausanias' description of this work by Lycius, the son of Myron suggests, they are complementary pairs!

He himself explains that Achilles and Memnon represent warriors (probably meant specifically to represent very strong warriors, as their duel seems to have been Achilles' hardest duel because Memnon was so similar in strength), Odysseus and Helenus represent wisdom, albeit of a different sort (Odysseus generally tends towards the strategy side of things built around his ability to be cunning, while Helenus tends towards the counsel type more based on his authority as someone in connection with the divine), and Paris and Menelaus represent feuding (as if Paris is supposed to represent Troy and Menelaus is supposed to represent the Achaeans, I suppose). He doesn't explain Aeneas and Diomedes or Deiphobus and Big Ajax. Personally, I assume Deiphobus and Big Ajax represent a warrior type who wields brute strength, though in role Big Ajax is more similar to Hector in that he is primarily a defensive fighter. Aeneas and Diomedes I can only think of the whole thing where Diomedes, having been empowered by Athena, injuresAphrodite while she defends Aeneas. Maybe indirectly they represent the patron goddesses/divine protection of each side in the war? I don't know.

The depiction of Thetis and Eos pleading to Zeus because of Achilles and Memnon not only represents Zeus’s aspect as ruler of Olympus, but I imagine it also references his being responsible for balance, in The Iliad he is often associated with the scales. That the scene with Zeus is in the middle and the complementary pairs are on the edges, I think, perhaps points to this idea of the scales in which each is being weighed against their complementary enemy.

Anyway, I find this interesting because it gives some insight into how these characters might have been viewed in the past. It's interesting to know, for example, that Helenus and Odysseus may have been seen as complementary in their roles in each army.

#Helenus of Troy#Odysseus#Thetis#Eos#Achilles#Memnon#Diomedes#Aeneas#Big Ajax#Deiphobus#Menelaus#Paris of Troy#Birdie.txt

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

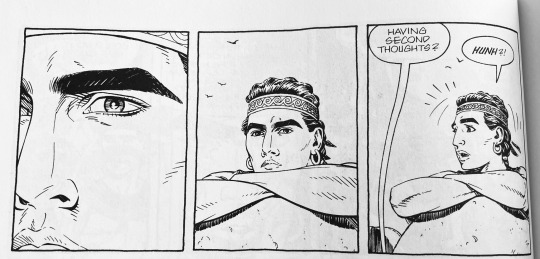

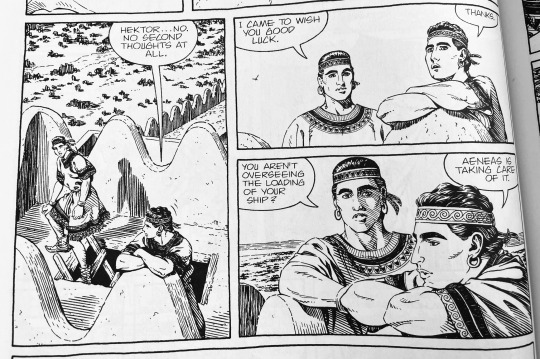

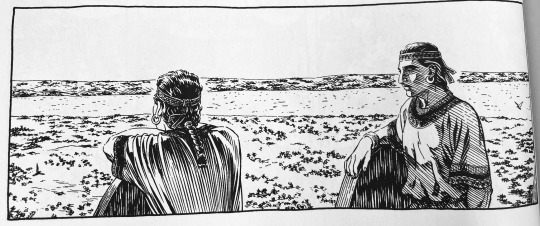

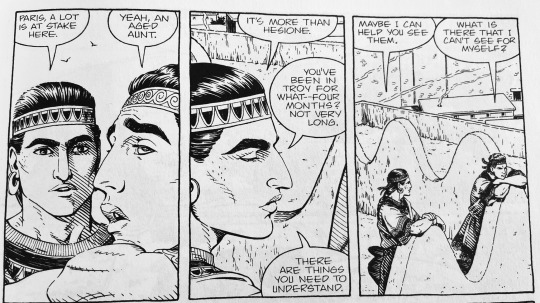

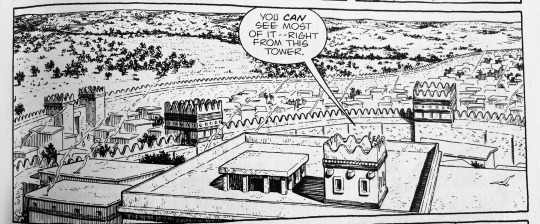

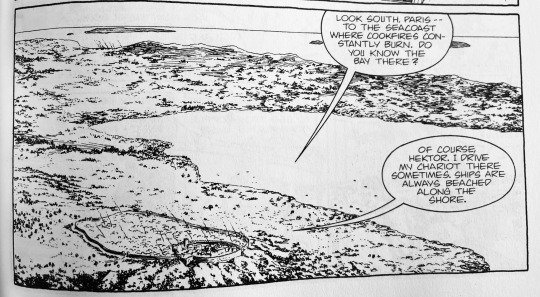

Excerpt from Eric Shanower’s epic comic series, Age of Bronze. I love how this sequence shows what Troy really looked like, and how it seemed like the center of the world in terms of trade.

Here we see two princes of Troy, Paris (impulsive long-lost prick), and Hektor (responsible eldest), discussing the latter’s mission to get the king’s sister back.

“Having second thoughts?”

“Hunh?”

“Hektor…no. No second thoughts at all.”

“I came to wish you good luck.”

“Thanks.”

“You aren’t overseeing the loading of your ship?”

“Aeneas is taking care of it.”

“Paris, a lot is at stake here.”

“Yeah, an aged aunt.”

“It’s more than Hesione. You’ve been in Troy for what — four months? Not very long. There are things you need to understand. Maybe I can help you see them.”

“What is there that I can’t see for myself?”

“You can see most of it — right from this tower.”

“Look south, Paris — to the seacoast where cookfires constantly burn. Do you know the bay there?”

“Of course, Hektor. I drive my chariot there sometimes. Ships are always beached along the shore.”

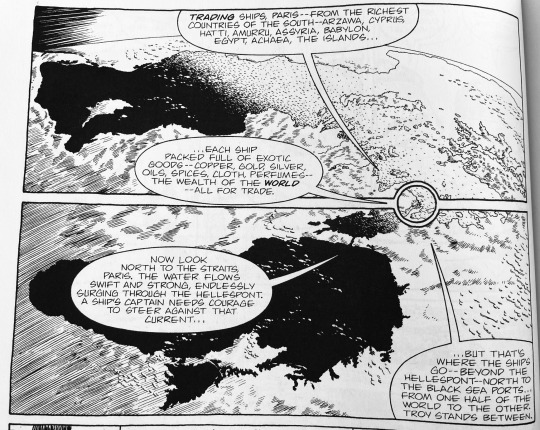

“Trading ships, Paris — from the richest countries of the south — Arzawa, Cyprus, Hatti, Amuru, Assyria, Babylon, Egypt, Achaea, the islands…

“…each ship packed full of exotic goods — copper, gold, silver, oils, spices, cloth, perfumes — the wealth of the world — all for trade.

“Now look north to the straits, Paris. The water flows swift and strong, endlessly coursing through the Hellespont. A ship’s captain needs courage to steer against that current…

“…but that’s where the ships go — beyond the Hellespont — north to the Black Sea ports…from one half of the world to the other. Troy stands between.”

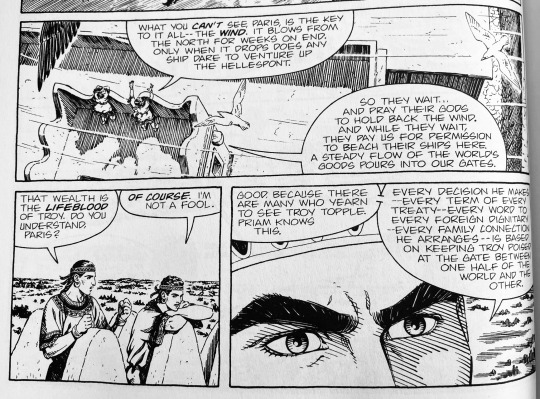

“What you can’t see, Paris, is the key to it all — the wind. It blows from the north for weeks on end. Only when it drops does any ship dare to venture up the Hellespont.

“So the wait…and pray their gods hold back the wind. And while they wait, they pay us for permission to beach their ships here. A steady flow of the world’s goods pours into our gates.

“That wealth is the lifeblood of Troy. Do you understand, Paris?”

“Of course. I’m not a fool.”

“Good because there are many who yearn to see Troy topple. Priam knows this. Every decision he makes — every term of every treaty — every word to every foreign dignitary — every family connection he arranges — is based on keeping Troy poised at the gate between one half of the world and the other.”

(Pt 2 here)

This is from volume 1, A Thousand Ships, available from Image Comics or Hungry Tiger Press 📚

#the iliad#age of bronze#eric shanower#paris of troy#hector of troy#helen of troy#epic tale#classics#historical fiction#eisner awards

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

@chrumblr-whumblr Day Six: Alternate prompt--Betrayal

Fandom: Original work/Greek Mythology. I've been vaguely developing a sci-fi take on the Odyssey focusing on Telemachus because I love my boy. It's also tying in Ascanius, Aeneas' son from the Aeneid, and Antgone, from the play of that name. This particular scene is set reasonably late in the picture, after Odysseus's return and the main characters have met up. Also pulling in some aspects of the Telegony

Word count: 1,319

__

“Can you teach me how to fly?”

Telemachus glanced sideways at the young boy, hands clasped neatly behind his back, dark eyes staring up at him hopefully. He glanced back to the window, at the stars glowing around them.

“No,” he said simply. Out of the corner of his eye, he could see the Telegonus’ shoulder’s slump. For a moment, he couldn’t help but feel a little guilty--he remembered being that age. He remembered how desperately he wanted to learn all of the things a warrior should know. He remembered no one being willing to teach him. “Not right now,” he amended.

The boy immediately brightened at that, moving forward to lay a hand on the back of Telemachus’ chair.

“What does that do?” he asked, pointing towards a series of buttons on the dashboard. Telemachus glanced at them, then back at the boy.

“I said not right now,” he said. He barely knew how to pilot this ship himself, it was all mostly made up as he went. Teaching this boy did not seem appealing. “Go find Ascanius.”

“But I want you to teach me.”

Telemachus didn’t say anything, just continued staring at the stars in the far distance around them.

“It’s your bedtime,” he said finally.

“I don’t have a bed time!” Telegonus protested.

“You do now.” Making sure the ship was on its programmed course, he stood. “Come on.”

“You’re not serious,” Telegonus cried.

Telemachus knew he was being unfair. The boy was not really a boy anymore, bordering on manhood. And he remembered being that age, being so determined to be grown up, so eager to be an adult.

But he had little patience for this young man, and for the reminders he received every time he saw him. The familiarity of his face, the foreignness of his eyes.

“Then go find someone else to bother,” he said finally, crossing his arms. Telegonus stared at him for a long time, then crossed his own arms and echoed Telemachus’ stance. The effect was diminished somewhat by being half the size and twelve years old.

“We’re supposed to be brothers, aren’t we? That’s what my mother said.

“Get out of my cockpit,” Telemachus said, reaching the end of his patience. Telegonus let out an angry huff and threw his hands in the air.

“Isn’t family supposed to look out for each other!” he cried.

“You’re not my family,” Telemachus said. Telegonus fixed him with a long, watery stare. Then he let out a long huff of air and turned to storm out of the cockpit. Telemachus leaned against his chair and covered his face with his hand.

He stood there for a long moment and then decided he needed something to drink. With one last look at the flight controls, confirming he wouldn’t be needed, he made his way out of the cockpit and towards the small kitchen galley on the ship.

They were almost out of coffee he noted mournfully. If they could manage it, they needed to do a supply run soon. He regretfully made a half strength coffee, not in bad enough a mood to use so much of it and deprive someone else.

“You’re hard on the kid.”

A voice came from behind him and he started, turning to see Antigone, leaning against the wall beside the door. A mug was in her hand--presumably her signature tea blend.

“I don’t have to be nice to him,” Telemachus said. He stared at the pale coffee dripping into his mug.

“Yeah, but you’re not this hard on Ascanius, and he’s not that much older.” She stepped forward, taking a sip of tea. “You’re mean.”

Telemachus didn’t answer for a long moment, waiting until his coffee had finished being made. Then he retrieved it and took a long sip. Far too weak.

“There’s nothing in life that says I have to be nice,” he said finally, turning around. She raised an eyebrow.

“Telemachus, I’ve known you barely a month. But I know the way you behave around that kid--it’s not you.”

He sighed, wrapping his hands around his mug and leaning against the kitchen counter. The ship was humming under them, a familiar background song.

“He’s just a kid--more than that,” Antigone tapped her knuckles on the table that spanned the center of the kitchen. “He’s your brother.”

“Not really,” Telemachus said automatically. Antigone shrugged.

“Yeah, people said that about my brother. You share the same father. You have the same blood.”

Telemachus took another long sip of his coffee, not caring that it burned his tongue on the way down.

“Yeah. Father,” he said bitterly. The word felt heavy on his tongue, tasted of shattered dreams and broken promises. Antigone didn’t say anything, just waited, mug in one hand, the other resting on the table.

He tapped a finger against the top of his mug, turning to stare across the room at the screen showing the stars outside.

“Every time I look at that kid, I think about everything my father wasn’t,” he said finally. And now that he had started talking, he felt the need to speak more, to say everything. “I spent my childhood hearing stories about him, building him up in my mind. The great Odysseus, hero of Troy, Star-sailer. I spent my life expecting him home, waiting to know who he was. I spent my life watching my mother wait for him.

“And then he came home and he was everything I expected him to be. Great, heroic, a warrior. He swept all my problems away and my mother into his arms and I saw her happy for the first time in my entire life. Actually happy, happy and in love. Joyful and hopeful. I saw her waiting rewarded. And I had a chance to know my father.”

He sighed, staring down at his coffee, watching the too-pale liquid reflect his face back at him.

“And then he betrayed that. I had an image of him, a perfect hero. And he wasn’t that. He was a paranoid, broken old man who had neglected his family and betrayed my mother. And everytime I look at that boy, I remember twenty years of waiting and a man who shattered my entire life.”

He looked up at Antigone, who had been listening silently, a fact he was immensely grateful for.

“He exiled me for a crime I might commit. He betrayed my mother, who waited so loyaly for him, gave up twenty years of her life for him. And she doesn’t even care.”

He gripped his mug, knuckles turning white around it, remembering a childhood of stories and promises and an adulthood of those stories and promises turning to ash around him.

“It’s not the kid’s fault,” Antigone said quietly.

“I know,” Telemachus said. “But I can’t look at him without remembering, and I can’t remember without being so angry.”

“Fathers,” Antigone said dryly. Telemachus nodded in agreement and they both took a long sip of their drinks. “But don’t punish Telegonus for something he hasn't done.” She fixed him with a long expression and Telemachus sighed heavily.

“I hate how much I’m like him,” he said softly. Antigone laughed at that, a soft, bitter laugh.

“You’re like him in good ways as well,” she said. “Find those.”

“I can try.” He gave another long breath, pushing himself off the counter and taking a long swallow to finish his coffee. It wasn’t very good anyway. “I guess I can start by apologising to Telegonus.”

“That’s the spirit,” Antigone said. She took another sip of her tea and settled herself into a seat at the table. “You and the kid together, now that’ll give your old man some nightmares.”

“I’m not sure I want that,” Telemachus said, almost to himself. Maybe part of him was still ten years old and wanted the warrior hero father to come home.

Maybe part of him always would be.

#wren writes#chrumblr whumblr challenge#oc: Space Greek Mythology#<- need a better name#telemachus#antigone#telegonus#the odyssey#the telegony#i really need to do a LOT more reading of greek epics and stuff before I actually write this#but i have some fun ideas#no real plot concept at the moment#and need to finalise a BUNCH of worldbuilding#liek WHAT are the gods in this#things to CONSIDER

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Both Scipio Africanus and Hannibal are cast with aspects of Aeneas…. Turning a foreign war into a civil one….

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lupa and other Roman Founding Myths in the Riordanverse.

Including Romulus, Remus, and Lupa; Aeneas fleeing Troy; and archeological evidence on the founding of Rome. (And the Mist in the Riordanverse)

Chapter 2, In The Beginning, covers the founding myths of Rome.

The first is on Remus and Romulus, the twins that were born to virgin priestess Rhea Silvia who claimed Mars had raped her. Her uncle Amulius, who was the current king of Alba Longa after his brother was taken off the throne. Not wanting children with a more legitimate claim to the throne than him, he ordered his servants to drown the babies in the river Tiber. Before they were washed away to their death by an incoming flood, a wolf came to the rescue and nursed them. When they grew up, they then set out to establish their own city. They disagreed on where to build the foundations and chose different hills. When Remus later tried jumping over Romulus’ defenses, Romulus killed his brother.

After Remus’ death, the city needed more citizens. Romulus declared Rome an asylum for all runaway slaves, criminals, wanderers, and refugees. The problem was that all of their new citizens were men, and they lacked women. So, they stole young women from neighboring towns. Most fought back, and Rome defeated them, but the Sabines in particular did not stop fighting until the abducted women came out and put a stop to their fighting, claiming they had come to love their new husbands and couldn’t bear to see either side die.

In order to keep his new citizens from fleeing from these fights, however, Romulus had constructed a statue temple of Jupiter and prayed to it to give his men courage. It would later turn into the Temple of Jupiter Stator. Cicero later stood in front of said statue while dismantling Catiline’s plot.

Later Romans had different variations of this story. Some claimed the fight for the women was a ‘just war’ because the other sides had denied their request for intermarriage. Some claimed that Rhea Silvia’s claims were a cover for a mortal affair. Some avoided the point of Romulus killing Remus, usually by altering the story so Remus lived past Romulus or by fading him out of the story once they first established Rome’s foundations.

Whatever the case, Beard points out that all of the different versions reflect the culture later Romans had at the time, especially after Catiline’s plot. There were themes in both their myths and culture at the time revolving around fratricide and the nature of Roman marriage, the former being an extreme source of discomfort for Roman citizens at the time.

Aeneas’ myth is also covered in this chapter. Aeneas, a Trojan hero, escaped Troy during the Trojan War with his son and father. He reached Italy, bringing with him some artifacts of his past life.

There are several other versions of his story, often intertwined with Greek literature, where Aeneas had visited Delos at one point or another. Some say his tomb was found in Lavinium, a town not far from Rome. Some versions said Aeneas brought the statue of the goddess Pallas Athena from Troy to be kept in the temple of Vesta in the Roman Forum.

Considering the story of Aeneas was just as heavily a part of Roman culture as Romulus’, Some Romans attempted to validate both at once by saying Aeneas was Romulus’ grandfather. One version states that Aeneas founded Lavinium while his son, Ascanius, founded Alba Longa, the city that Remus and Romulus were later exiled from, and “a shadowy and, even by Roman standards, flagrantly fictional dynasty of Alban Kings was constructed to bridge the gap between Ascanius and the magic date of 753 BCE” (page 77).

In these founding myths, Beard points out that the Romans are always the foreigners whether it be riff-raff coming to Rome as an asylum or Aeneas fleeing Troy and either establishing Rome himself or finding settlers already there in exile from another land.

Archeology can provide other evidence as well. Romans had a tendency to hold onto articles of the past from physical items to rituals and politics. Some evidence suggested there had been two civilizations living in the hills of Rome because they called two of them colles instead of montes despite them effectively being synonyms in Latin. Beard points out how in the story of Romulus the Sabines and Romans lived in relative proximity, and questions if these differences in words reflect the myth based on who occupied what hills.

Physical evidence, such as graves and excavation sites, leave other implications. Early burial sites and pottery evidence have been predicted to be from 1000 BCE, while radiocarbon dating suggests they're all too young by about a hundred years. There is also enough evidence from the Middle Bronze Age, between 1700 and 1300 BCE, that point to people having already settled down rather than passing through.

There is also more evidence that directly contradicts earlier myths. There are few archeological remains to suggest the Temple of Jupiter Stator had been built so early, “which must have in any case been rebuilt by Cicero’s time, especially if its roots really did go back to the beginning of Rome” (page 53).

There was also a set of black stone slabs in the pavement of the Forum, making it distinct from the rest of the flooring in the area. When the stone below it was excavated, an early shrine, possibly to the god Vulcan was found, along with Athenian pottery, early Latin written in stone, and every day trinkets such as cups and jewelry. Some Romans at the time believed it to be an unlucky spot, others believed it to be Romulus’ grave.

In the Riordanverse, some of these myths have already been established as true, such as Romulus and Remus’ given by the presence of Lupa. Obviously, in fiction, some truth is going to be bent. But how much? I’m assuming that the rest of the world knows about as much about Rome as we do from archeological evidence to myths.

However, in the Riordanverse mythological events witnessed by mortals are disguised as non-mythological thanks to the Mist. How much, in a fantastical setting like this, would be either hidden away from or shown to the rest of the world? When would these myths have transitioned from fact to fiction, and how much could we attribute to the Mist? Could different people believe in different stories thanks to the Mist? How do we establish which one is the ‘true’ myth in this setting?

It’s established that both Greek and Roman myths exist because of the belief put into them. It’s what causes two different pantheons entirely, with each Greek god having their very real Roman counterpart while still technically existing as one entity. How true does this make each of their myths? Based on chronology, Greek myths would have a certain superiority to the truth than Roman ones.

But how do we know?

Much of history is written in the eyes of the victor which tends to distort it. Would New Rome, for the sake of their pride, hold on to the more appealing myths? If so, it further blurs the line of whether the Greek or the Roman version of a myth is the ‘right’ one.

We don’t.

There are several versions of the Roman founding myths in Heroes of Olympus: Lupa, who raised Remus and Romulus, as previously mentioned and Aeneas.

“‘Romans.’ Clarisse tossed Seymour a Snausage. ‘You expect us to believe there’s another camp with demigods, but they follow the Roman forms of the gods. And we’ve never even heard of them.’ Piper sat forward. ‘The gods have kept the two groups apart, because every time they see each other, they try to kill each other.’ ‘I can respect that,’ Clarisse said. ‘Still, why haven’t we ever run across each other on quests?’ ‘Oh yes,’ Chiron said sadly, ‘You have, many times. It’s always a tragedy, and always the gods do their best to wipe clean the memories of those involved. The rivalry goes back to the Trojan War, Clarisse. The Greeks invaded Troy and burned it to the ground. The Trojan hero Aeneas escaped, and eventually made his way to Italy, where he founded a race that would someday become Rome. The Romans grew more and more powerful, worshipping the same gods but under different names, and with slightly different personalities.’” – Page 549, The Lost Hero

And I can’t find the quote at the moment, but I believe Lupa talks about Remus and Romulus in the series. The fandom wiki says “She can also be a loving mother, as Percy claimed that she frequently tells her role in Remus and Romulus' fates, implying that she still is proud of them” under the personality tab.

To choose between them would be a relatively simple choice: while Chiron, as a normally reputable source, spoke of Aeneas’ tale, Lupa is a character we directly interact with in the text, having lines of her own. (Chiron even references her as his Roman counterpart a page or two later.) Of course, if you went with the theory Beard stated that Aeneas was actually the twins’ grandfather, both could be true.

But only choosing one to be ‘right’ brings up the Mist: Could the story Chiron told them only be to disguise Lupa’s mythological role?

Prior to Jason announcing the presence of Roman mythology, the demigods at Camp-Half blood genuinely did not know that there were Roman counterparts to their Greek gods, let alone Roman demigods. There has previously been divine interference to make sure the two groups don’t cross paths, as stated by Chiron. The mist could be one of the tools the gods used to be sure of this, which includes covering up evidence of Roman myths being not so… mythological. This could lead to several myths existing at once, each with their own evidence.

But does this make the story Chiron told of Aeneas false? I still think not. While not a thing found in traditional Greek mythology, a god can fade when people’s belief in them fades.

“‘But gods can’t die,’ Grover said. ‘They can fade,’ Pan said, ‘When everything they stood for is gone. When they cease to power, and their sacred places disappear.” – Page 314, The Battle of the Labyrinth.

I would have used a quote from Trials of Apollo because I’m sure there are quotes more explicitly on the rise to power thanks to Caligula, Commodus, and Nero, but I cannot find it for the life of me without rereading the series which I do not have time for at the moment.

But this shows how belief of a being can cause both the rise and fall to and from being a deity. Lupa is explicitly stated to be a wolf-goddess in the books (Despite not being one in the original myth, but once again Percy Jackson isn’t the most adherent to those. Perhaps she was made immortal to train all future demigods, like Chiron.) and while I’m pretty sure Aeneas would have to exist first in order to become immortalized, I’m sure enough people would have believed in his story and the spirit of Rome (his would-be sacred place, I imagine) that it could plausibly happen in that universe.

Furthermore, there are 4 known and confirmed pantheons in the Riordanverse: Greek, Roman, Norse, and Egyptian. They are bound to have overlapping myths, from the soul of the sun to the creation of the world. And when you confirm that these pantheons exist, you are by extension confirming that their individual myths are true.

This is quite possibly the most long winded way I could have said that because the Riordanverse has weird laws of divinity and magic, multiple myths can exist at the same time even if they directly contradict each other. Did I take you for a ride? Because I took me for a ride too. My opinion changed several times on this matter as I was writing out my thoughts and looking for quotes. I think I’ve spent too long with my head buried in technical history books based in fact that I forgot I was working with a fantastical universe here where plenty of things defy laws of existence in general, let alone physics lmao.

Back to Jason, this time in relation to Lupa. (Because when I talk about Rome, chances are it’s because Jason is at the root of my thoughts.) In The Son of Neptune, she trains new Romans before they end up in Camp Jupiter.

“Lupa had taught him about demigods, monsters, and gods. She explained that she was one of the guardian spirits of Ancient Rome. Demigods like Percy were still responsible for carrying out Roman traditions in modern time — fighting monsters, serving the gods, protecting mortals, and upholding the memory of the empire. She’d spent weeks training him, until he was as strong and tough and vicious as a wolf. When she was satisfied with his skills, she’d sent him south…” – Page 36, The Son of Neptune

But when Jason was 16, he had 12 lines on his arm, representing 12 years of service. We know one scenario where a year doesn’t quite represent a full year of service:

“Congratulations, Percy Jackson. You now stand on probatio. You will be given a tablet with your name and your cohort. In one year’s time, or as soon as you complete an act of valor, you will become a full member of the Twelfth Legion Fulminata. Serve Rome, obey the rules of the legion, and defend the camp with honour. Senatus Populusque Romanus!” – Reyna to Percy, Page 89, The Son of Neptune

Considering neither Frank nor Hazel received a line for the act of valor, it only counts as a qualification to become a full member as opposed to an act of valor being worth a year of service in general. To get his 12th mark by 16, even if he had managed to complete an act of valor on his very first day, he would have still been only 4 or 5. Somehow, I highly doubt a 5 year old would be capable of doing that and will be working off the assumption that he completed an entire year of probatio.

This means that Jason must have joined when he was 4 years old at the latest in order to get his 12th mark by 16. (And he would have been 16 at the max. He turned 17 in HoO, around 8 months after his disappearance from Camp Jupiter. He could have received his 12th mark at 15 and received his 13th sometime in that 8 month gap had he been there, meaning he could have been as young as 3 when he arrived on the younger side of things.) He would have spent a year or two with Lupa, having been abandoned by his mom at the Wolf House when he was 2.

Jason is also a special case, though, being both a son of Jupiter (in a house with a daughter of Zeus; probably one of the reasons he was taken away so young, because Thalia knew their dad, and when a demigod knows about the mythological world, it’s harder to hide from it.) and champion of Juno. I highly doubt that Lupa receives anyone that young. Even if she did, would they have survived?

“Assuming I passed all their tests—aka, didn’t die a horrible, wolf-inflicted death—I’d then trek southward through a monster infested wilderness (second-worst campout ever) to Camp Jupiter, where I’d present your letter of recommendation to whoever was in charge and hope I’d be accepted into the ranks of the Twelfth Legion Fulminata. Which brings me to this question: How much would it suck to go through all that and not get into a cohort? Answer: A lot. Not that new recruits need to worry about rejection these days. According to my centurion, Leila, the legion’s numbers were badly depleted last summer.” – Camp Jupiter Classified: A Probatio’s Journal

It’s heavily implied here that Lupa (or her wolves) kills whoever fails her tests. I’m assuming that Lupa was under orders to make sure Jason lived, because I’m pretty sure a 3 year old would not be able to pass her standard tests. That being said, most kids she trains are in fact kids, children by all definitions of the word.

“At a certain age, one way or another, we find our way to the Wolf House. If Lupa thinks we’re worthy, she sends us south to join the legion… You’re old for a recruit. You’re what, sixteen?” – Reyna to Percy, Page 37, The Son of Neptune

This implies that legacies such as Octavian must go through Lupa to join the legion as well, even if they grew up in New Rome. They all spend an indeterminate time with her; Percy spent a vague ‘few weeks’ while Jason spent at least a year with her. While it’s hard to guess what the average age is, we can take a guess.

“Octavian stepped off the dais. He was probably about eighteen, but was so skinny and sickly pale he could’ve passed for younger.” – Page 55, The Son of Neptune

“Percy noticed seven lines on Octavian’s arm — Seven years of camp, Percy guessed.” – Page 58, The Son of Neptune

This would put Octavian at roughly 11 when he would have gone to the Wolf House. Frank was 16, but was most likely an odd case because he was part of the 7, and 16 was already previously stated to be rather old for a newcomer. I tried finding ages on other people like Dakota and Gwen but once again, I don’t have time to read the entire book at the moment. (Even then, from the pages I skimmed I don’t think they’re mentioned.) I’m treating Reyna as a special case as well, considering her history with Circe’s island.

So I would guess that most kids wind up at the Wolf House around 11 or 12, give or take a few years.

Regardless, Lupa probably hasn’t had to deal with many other (if any) kids as young as Jason in a very long time. But she has dealt with young kids before: Remus and Romulus who she is quite fond of.

Despite her harsh nature, Percy allegedly described her as motherly when she wants to be. I think that when faced with baby Jason who was just two years old when he was left at her mercy, she would have a soft spot. In The Lost Hero when appearing in his dreams, she makes a joke about him being their ‘Saving Grace’ to make a pun out of his name. She’s clearly familiar with Jason, considering this is 12 years after he would have left the Wolf House.

I personally think Lupa would have taken on a much more nurturing role for Jason than she does for other recruits. She’s clearly capable of it, given her founding myth and continued fondness of Remus and Romulus despite her repeated harshness toward most recruits. I think that in order for a two year old to survive at all, it would have been necessary. A two year old would not be capable of most things it takes to survive in the wild (with wolves no less), especially at the beginning when he had just arrived. A four year old, even, would not be capable of most things it takes to survive in the wild, let alone make the trek to Camp Jupiter when it took Percy 3 weeks. In order to survive, Jason would have had to have gotten special from Lupa.

Maybe it’s the wolf!Jason lover in me, whether it’s werewolf!Jason or just plain feral!Jason (oh Jason, you could never be plain to me. Not when one of my most used tags is literally “Jason Grace is not boring and in this essay I will” and damn do I essay about him.) but I firmly believe that Lupa plays favourites and that Jason is one of them.

Also, I’d like to point out that the heavily militaristic legion that prides itself in its rules literally sends every single one of their recruits to learn the ways of the wolf before being authorized to actually join. Ironic, is all, especially when it would probably be a lot more effective to just… train the kids at Camp Jupiter from the get-go.

New Rome, what are you doing?

I guess I’m going to have to figure that out for myself, aren’t I? It’s literally the entire reason I am reading this book and writing this post in the first place: for the sake of some fan fiction. (And self enjoyment because the history of Rome is insanely fascinating, but in the name of comedy go with me here.) I’ll get there in the end, but for now… One step at a time.

For now, I’d like to go back to my summary on chapter 2 of SPQR. Beard mentions how all of these founding myths all end up back at the same square: Rome has always been a safe haven for outsiders. In Son of Neptune, we see how most of the cohorts look down upon newcomers and underdogs alike. It’s what makes the cohort Percy joins unique: They root for newcomers and underdogs, which are what Percy, Frank, and Hazel all are.

Jason is also mentioned to be a part of this cohort. In fact, he notes Dakota (and others) as a friend in his own PoV. I enjoy playing with having Jason adhere to the ‘true, traditional Roman way’ as part of his gig as ‘Perfect Son of Jupiter, Praetor of the Twelfth Legion.’ However, I also enjoy slipping in Jason having underlying doubts, which in the end lead to his eventual love for the culture Camp Half-Blood creates.

I think that having Jason be welcoming to outsiders to morally elevate him in a way (and I mean this loosely: As a society as a whole we have descriptive and injunctive norms; The norms we should adhere to and the norms we do adhere to respectively. For example, people should avoid littering, but people tend to do it anyway. Being the one to break a norm and do what everyone should be doing gives a sense of having the moral high ground. In this case following the descriptive norm and going against the grain will morally elevate Jason as a protagonist to the reader — When I talk about morality when it comes to characters, it is not a commentary on my own moral beliefs, even when I do believe them to some extent. I could make a separate post entirely on the topic of Jason and descriptive vs injunctive norms if I’m being honest here.) from other cohorts. He could be the reason the fifth cohort is so welcoming: Because Jason would be one of the oldest, if not the the oldest, one there and he would set the precedent for that behaviour and attitude.

That would be one that adheres to more traditional Roman beliefs. New Rome could have other older traditions, but they contrast with a more modern, more objective moral norms such as the belief that everyone deserves some sense of creative liberation. (Think private school uniforms and the main debate against them being that sense of self is an important factor in expressing oneself and developing one’s identity. Not entirely the same, but it’s close to what I’m going for.) Because obviously ancient Rome would have some traditional takes that we as a society have aged out of for blatantly obvious moral reasons. For example, tying someone in a bag with weasels and throwing them in the Little Tiber would probably be considered cruel and unusual punishment in most cases.

Posing Jason as someone who sticks to old Roman beliefs to support his rise to position of praetor, but also posing him as someone who cares about moral beliefs outside of a predetermined list in the name of tradition would juxtapose his own character against itself in a way that foreshadows his inner turmoil about not being able to choose between a Greek or Roman lifestyle is fascinating to me. And by every god to have ever existed I need to do it. Does this even make any sense?

Ugh. And here I thought this post was going to be a lot shorter because I took significantly less notes on it. Clearly I had more commentary on this than I realized.

Jason Grace & Cicero Parallels || Chapter 1 on Cicero (and Catiline) Lupa || Chapter 2 on Roman Founding Myths Kings Of Rome || Chapter 3 on the Regal Period

#SPQR#SPQR fic#rome#ancient rome#roman history#roman mythology#jason grace is not boring and in this essay i will#jason grace#heroes of olympus#hoo#pjo hoo toa#percy jackson and the olympians#percy jackson#lupa pjo#camp jupiter#new rome#rick riordan#riordanverse#pjo fandom#pjo series#pjo#riordan universe

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

wait wait is dido and aeneas an antony and cleopatra callout? so was it just a well cleopatra is admittedly cool but antony failed at being a roman who does his job sort of thing

anon i may or may not have written a 25-page paper on vergil's aeneas/dido versus shakespeare's antony/cleopatra so this ask set fire to at least one circuit of my brain.

short version: yes, vergil's choice to write roman hero x foreign african queen immediately after the battle of actium is very weighted (cleopatra at this time was considered one of the main enemies of rome, more so than antony himself). aeneas leaving dido, choosing his fated duty and the creation of empire over love (and over the Effeminate Wiles Of An Exotic Woman, read that with the proper amount of dripping sarcastic disdain), is the exact opposite of the choice antony made in real life, so, yeah! exactly what you said! antony is a loser who gets pegged and aeneas is a proper proto-roman man who got his job done even though he is so so miserable and traumatized and a shell of himself.

notably, dido is also a much more morally upstanding figure than cleopatra (according to the morals of the time, at least), and carthage is shown in a shockingly positive light. when cleopatra does appear in the aeneid (for a few lines in book 8), she's in full enemy-of-rome-with-dangerous-foreign-gods mode. but dido gets a noble death! the narrative seems to accept that she's been wronged! what does it mean publius what does it all mean

of course there are a thousand complexities to this because vergil is vergil (25 pages. i died) but that's the shortest version i can give you. i think cleopatra and dido should have gay sex

#max.txt#asks#along with my paper i also wrote a one scene play where they have gay sex. because i'm normal?

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Laeta's reading list: October

Starting my Classics self-study where it always begins and ends for me: with the Aeneid. Not the actual text just yet, I'm circling around it and warming up and getting back in the game with a couple pieces of reception. Book-length appetizers, main course coming in November. Below the drop so my rambling monologue doesn't clutter anyone's feed.

Enea, lo straniero (Aeneas the Foreigner), by Giulio Guidorizzi. In progress. (In Italian.) Basically a very nicely done prose novelization of the Aeneid with occasional "professor mode" asides from the author for context or historical background. Good way to ease my brain back into this stuff.

Darkness Visible, by W.R. Johnson. The infamous monograph that launched a thousand arguments and the "Harvard School" of Vergil scholarship. Might as well, right? Just get straight into the Discourse. This one is going to be my melancholy dark academia book of the fall. Eheu, poor long-suffering Aeneas, poor heartbroken Parthenias, poor Rome, poor us.

La lezione di Enea (The Lesson of Aeneas), by Andrea Marcolongo. (In Italian.) I...have started this book three times and never finished it because I keep getting annoyed at it for being twee/not highbrow enough idk, but I keep going back to it because the book's reason for being is a nearly identical experience to my own: during the early days of the pandemic, after never really liking or understanding the Aeneid before, the author found herself drawn to it while the world was crumbling around her and finally Got It. Which is exactly when, how and why I also picked up the Aeneid seriously for the first time in 2021. So go figure. I should honor this book's existence enough to finally finish it. I'm also diving headlong, again, into Lingua Latina Per Se Illustrata, the legendary/infamous LLPSI, because I have to be real here: my Latin is actually GARBAGE. My fatal flaw with Latin is that I am C2 in Italian as a second language, and my brain is weirdly fast and intuitive at languages specifically (my one and only genuine talent.) So I learned Italian in that deliberate, conscious, adult-brain way that shines a light on all the similarities it has to its related languages. When it comes to Latin, this is a Problem. I can literally breeze through reading the first third of LLPSI, understanding absolutely everything while having studied nothing, absorbed nothing of the grammar, and acquired no ability to reproduce anything in Latin because it just sounds right and I know what it means already (or can puzzle it out) without having to work too hard at it. Then, abruptly, I hit a wall where I understand precisely Nothing anymore, and I haven't been able to build enough of a ladder of understanding in the first part of the book to get me to the lofty heights of chapter 25 or so. When this happens, I try again and try to be a good disciplined student and spend ages on each chapter starting from "Roma in Italia est," and copy it all out, and do all the supplemental exercises and Legentibus, and cross-reference concepts in Wheelock's etc., and that lasts for about two weeks before I throw the entire project out the window because I get so bored forcing myself to drill the stuff I already know. This time, my one-month experiment is in working with my weird brain instead of against it: the firehose method. I am just going to fucking barge my way through this book, just reading it straight through for comprehension/semi-comprehension/gist/exposure, then going back and doing it again, and sort of bashing its contents into my brain and trusting in my own not-quite-conscious ability to start getting used to patterns and structures and idioms. I am going to read the parts of the book I don't understand yet, and I'm going to keep reading them until I start to understand them. If this doesn't jump-start anything, eh, it was only one month wasted. And I'm going back to grammar and exercises in November. But I've got to just....start. As a little side treat, I've also just started Dante in Love by Harriet Rubin, because I saw it on the shelf at the library and it looked fun. There are two very non-serious reasons for me to be adding Dante to the mix, and neither of them are a carefully considered argument for how the Divina Commedia is actually also Aeneid reception. One is that I'm about to start leading my very first tabletop RPG as DM, and we're doing a play through of Inferno: Dante's Guide to Hell. Second, me and Dante have bonded over a shared, agonizing experience: a gigantic, head-spinning, life-ruining parasocial crush on a poet who died two thousand years ago. I feel you, Dante.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Adding a few things:

Myths change with time, and even between cities. For example, in the early cult Aphrodite was also a war goddess, though as the Ionian version spread only Sparta and a few other places continued to worship "Aphrodite Areia", and when it comes to Medea most cities asserted it was the Corinthians who killed her child, with only the Corinthians and Euripides claiming it was her.

The Amazons and Medea aren't Greek. Them being foreigners with strange traditions is a critical part of their myth (the whole point with the Amazons).

For the Trojans, they started out as foreigners, but in time they became Greeks.

Speaking of the Trojans, they were objectively in the wrong, as Paris kidnapped Helen and stole Sparta's treasure while a guest (a divine law guarded by Zeus himself) and the moral course of action would have been to send him back to Greece in chains alongside Helen, the treasure, and some more as an apology. That said, Hector is still a good person fighting to defend his city and family, and Aeneas is known as possibly the most pious individual on either side of the war.

If you find a mentions of "Aethiopians", they can be from anywhere south or east of Anatolia (the ones that tried to rescue Troy, for example, came explicitly from Susa, in modern day Iran, and would have been Elamites).

The Romans didn't copy Greek religion. They had their own religion of Italic origin, that was both highly syncretic and influenced by the Etruscans from the start, with Etruscan religion being itself heavily influenced by the Greek colonies in southern Italy. And since they REALLY admired Greek culture, they for the most part identified their own gods with similar Greek ones but still kept their own spin (for example, Mars was also a guardian of AGRICOLTURE, and Venus' immense portfolio included prosperity and victory (also, she remained married to Vulcan, even if their relationship was strained).

a quick psa to anyone recently getting into greek mythology and is a victim of tumblr and/or tiktok misconceptions:

-there is no shame in being introduced to mytholgy from something like percy jackson, epic the musical or anything like that, but keep in mind that actual myths are going to be VERY different from modern retellings

-the myth of medusa you probably know (her being a victim of poseidon and being cursed by athena) isn't 100% accurate to GREEK mythology (look up ovid)

-there is no version of persephone's abduction in which persephone willingly stays with hades, that's a tumblr invention (look up homeric hymn to demeter)

-as much as i would like it, no, cerberus' name does not mean "spot" (probably a misunderstanding from this wikipedia article)

-zeus isn't the only god who does terrible things to women, your fav male god probably has done the same

-on that note, your fav greek hero has probably done some heinous shit as well

-gods are more complicated than simply being "god of [insert thing]", many titles overlap between gods and some may even change depending on where they were worshipped

-also, apollo and artemis being the gods of the sun and the moon isn't 100% accurate, their main aspects as deities originally were music and the hunt

-titans and gods aren't two wholly different concepts, titan is just the word used to decribe the generation of gods before the olympians

-hector isn't the villain some people make him out to be

-hephaestus WAS married to aphrodite. they divorced. yes, divorce was a thing in ancient greece. hephaestus' wife is aglaia

-ancient greek society didn't have the same concepts of sexuality that we have now, it's incorrect to describe virgin goddesses like artemis and athena as lesbians, BUT it's also not wholly accurate to describe them as aromantic/asexual, it's more complex than that

-you can never fully understand certain myths if you don't understand the societal context in which they were told

-myths have lots and lots of retellings, there isn't one singular "canon", but we can try to distinguish between older and newer versions and bewteen greek and roman versions

-most of what you know about sparta is probably incorrect

-reading/waching retellings is not a substitute to reading the original myths, read the iliad! read the odyssey! i know they may seem intimidating, but they're much more entertaining than you may think

greek mythology is so complex and interesting, don't go into it with preconcieved notions! try to be open to learn!

37K notes

·

View notes

Text

So grieving, and in tears, he gave the ship Her head before the wind, drawing toward land At the Euboian settlement of Cumae. Ships came about, prows pointing seaward, anchors Biting to hold them fast, and rounded sterns Indented all the water's edge. The men Debarked in groups, eager to go ashore Upon Hesperia. Some struck seeds of fire Out of the veins of flint, and some explored The virgin woods, lairs of wild things, for fuel, Pointing out, too, what streams they found. Aeneas, in duty bound, went inland to the heights Where overshadowing Apollo dwells And nearby, in a place apart--- a dark Enormous cave -- The Sibyl feared by men. In her the Delian god of prophecy Inspires uncanny powers of mind and soul, Disclosing things to come. Here Trojan captains Walked to Diana of the Crossroads' wood And entered under roofs of gold. They say That Daedalus, when he fled the realm of Minos, Dared to entrust himself to stroking wings And to the air of heaven- unheard of path- On which he swam away to the cold North At length to touch down on that very height Of the Chalcidians. Here, on earth again He dedicated to you, Phoebus Apollo, The twin sweeps of his wings; here he laid out A specious temple. In the entrance way Androgeos' death appeared, then CeCrops children Ordered to pay every in recompense each year The living flesh of seven sons. The urn From which lots were drawn stood modeled there.

something something ...

Then he fell silent. But the prophetess Whom the bestriding god had not yet broken Stormed about the cavern, trying to shake His influence from her breast, while all the more He tired her mad jaws, quelled her savage heart And tamed her by his pressure. In the end The cavern's hundred mouths all of themselves Unclosed to let the Sibyl's answers through: "You, sir, now quit at last of the sea's dangers, For whom still greater are in store on land, The Dardan race will reach Lavinian country -- put that anxiety away -- but there Will wish they had not come. Wars, vicious wars I see ahead, and Tiber foaming blood. Simois, Xanthus, Dorians encamped-- You'll have them all again, with an Achilles, Child of Latium, he, too, goddess-born. And nowhere from pursuit of Teucrians Will Juno stray, while you go destitute, Begging so many tribes and towns for aid. The cause of suffering here again will be A bride foreign to Teucians, a marriage Made with a stranger.

Never shrink from blows. Boldly, more boldly where your luck allows, Go forward, face them. A first way to safety Will open where you reckon on it least, From a Greek City."

These were the sentences In which the Sibyl of Cumae from her shrine Sang out her riddles, echoing in the cave, Dark sayings muffling truths, the way Apollo Pulled her up raging, or else whipped her on, Digging the spurs beneath her breast. As soon As her fit ceased, her wild voice quieted.

-The Aeneid by Virgil tr. by Robert Fitzgerald

0 notes

Text

A bit of history of religion in Roman Empire

Have you ever wondered about the intricate tapestry of beliefs that served as the spiritual backbone of the mighty Roman Empire? Enter the world of the Religio Romana, the main religion of ancient Rome, a polytheistic belief system honoring a diverse pantheon of gods and spirits. This exploration delves into the multifaceted aspects of Religio Romana, its role in shaping Roman society, and the transformative influence of Christianity.