#6th June 1944

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

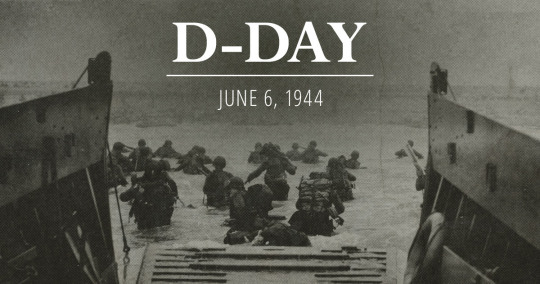

On this day, 79 years ago, 326,547 troops and 54,186 vehicles were deployed to the beaches of Normandy.

This day is better known as The Day of Days or D-day, codenamed "Operation Overlord."

#D-day#day of days#june 6 1944#June 6th#Invasion of Normandy#Normandy#Utah#Omaha#Juno#Gold#Sword#allied forces#band of brothers#hbo war#Ww2#ww2 veterans#wwii history#wwii germany#Douglass C-47#Hi ho silver!#the pacific#america

277 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Ms. Forster enlisted over 1,000 knitters via Facebook from the U.K., the United States, Australia, and New Zealand to complete the 3D tapestry. The result is 80 meters (88 yards) of 80 3D panels of knitted and crocheted scenes of the D-Day invasion."

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have no words that have not already been said about the men and women who embarked on this endeavor, but I still thank them. I thank them from a place very few will ever know.

“We’ll start the war from right here!”

Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., assistant division commander of the 4th Infantry Division, first wave on Utah Beach. He would die 5 weeks later from a heart attack at 56 yo.

"You get your ass on the beach. I'll be there waiting for you and I'll tell you what to do. There ain't anything in this plan that is going to go right."

Colonel Paul R. Goode, in a pre-attack briefing to the 175th Infantry Regiment, 29th Infantry Division, Omaha Beach

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

D-Day, designed by Charles S Roberts for Avalon Hill, 1961 -- Credited as the first "hex and chit" wargame, D-Day was published only 17 years after the events of June 6, 1944. My copy of D-Day appears to be the 1962 first revision, aka "1961B." The annual Charles S Roberts awards are named for the pioneering designer and founder of Avalon Hill.

#D-Day#D Day#Charles S Roberts#Avalon Hill#wargame#board game#WWII#wargaming#1960s#June 6 1944#June 6th 1944#6 June 1944

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

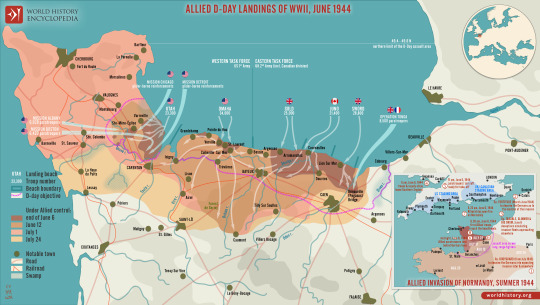

A mission map of that fateful day 6th June 1944

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

D Day

6th June 1944

All gave some. Some gave all.

1 note

·

View note

Text

US soldiers give cover on Omaha beach - 6th June 1944

#world war two#ww2#worldwar2photos#history#1940s#ww2 history#wwii#world war 2#wwii era#ww2history#normandie#normandy landings#normandy#1944#dday#Omaha#omaha beach

577 notes

·

View notes

Text

To commemorate the anniversary of D-Day, a short thread of photos colourised by DBColour (Colourising History on Facebook). Descriptions run from top-to-bottom.

Piper Bill Millin, seen here landing on Sword Beach with his bagpipes with Lord Lovat’s Commandos of 1st Special Service Brigade. IWM B 5103.

Commandos of 1st Special Service Brigade after landing on Queen Red beach, Sword area, 6 June 1944. British Airborne troops smile from the door of their Horsa glider as they prepare to fly out as part of the second drop on Normandy on the night of 6th June 1944. LCI(L) 135 of the 2nd Canadian (262nd RN) Flotilla carrying personnel of the North Nova Scotia Highlanders and the Highland Light Infantry of Canada en route to France on D-Day, 6 June 1944. (Library and Archives Canada Photo, MIKAN Nº. 3205043) Film still from the D-Day landings showing commandos aboard a landing craft on their approach to Sword Beach, 6 June 1944.

LCA (Landing Craft Assault) containing soldiers from the Winnipeg Rifles head for the Normandy Juno beach - June 6, 1944.

Commandos approach Sword Beach in a Landing Craft Infantry (LCI). Ahead, the beach is crowded with tanks and vehicles of 27th Armoured Brigade and 79th Armoured Division.

Troops of 3rd Infantry Division on Queen Red beach, Sword area, circa 0845 hrs, 6 June 1944. In the foreground are sappers of 84 Field Company Royal Engineers. Behind them, medical orderlies of 8 Field Ambulance, RAMC, can be seen assisting wounded men.

A Horsa glider near the Caen Canal bridge at Benouville, 8 June 1944. No. 91 (PF800), carried Major John Howard and Lieutenant Den Brotheridge of No.1 Platoon, 'D' Co., 2nd Battalion Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry in the early hours of D-Day. © IWM B 5232

#d-day#d-day anniversary#ww2#world war 2#second world war#history#military history#british army#lest we forget#remembrance

304 notes

·

View notes

Text

May 1944

White stripes painted on B-26 in preparation of the D-Day landings on June 6th at Normandy

@WW2Today via X

218 notes

·

View notes

Text

• Jake McNiece

James Elbert "Jake" McNiece was a US Army paratrooper in World War II. Private McNiece was a member of the Filthy Thirteen, an elite demolition unit. McNiece practiced in several operations throughout world war 2 with the 101st Airborne Division.

James McNiece was born on May 24th, 1919, in Maysville, Oklahoma, the ninth of ten children born to Eli Hugh and Rebecca McNiece, and of Irish American and Choctaw descent. During the Depression, the family moved to Ponca City, Oklahoma in 1931. In 1939, he graduated from Ponca City High School and went to work in road construction, and then at the Pine Bluff Arsenal, where he gained experience in the use of explosives. McNiece enlisted for military service on September 1st, 1942. He was assigned to the demolition saboteur section of what was then the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment. This section became the Filthy Thirteen, first led by Lieutenant Charles Mellen, who was killed in action on June 6th, 1944, during the Invasion of Normandy. Following Mellen's death, Private McNiece became acting leader of the unit. McNiece is iconically recognized by wearing Native American–style "mohawk" and applying war paint to himself and other members of his unit which, excited the public's interest in this unit. The inspiration for this came from McNiece, who was part Choctaw.

McNiece's deliberate disobedience and disrespect during training prevented him from being promoted past Private when most Paratroopers were promoted to Private First Class after 30 days. McNiece would act as section sergeant and first sergeant through various missions. His first sergeant and company commanders knew he was the man the regiment could count on during combat. McNiece went on to make a total of four wartime combat jumps, the first as part of the Invasion of Normandy in 1944. In the same year he jumped as part of Operation Market Garden in the Netherlands. McNiece would see action again at the Siege of Bastogne, part of the larger Battle of the Bulge. During fighting in the Netherlands, he acted as demolition platoon sergeant. He volunteered for pathfinder training, anticipating he would sit out the rest of the war training in England, but his pathfinder stick was called upon to jump into Bastogne to guide in resupply drops. McNiece received a Bronze Star, Purple Heart, and French Legion of Honor medals for his service and deeds during the war.

His last jump was in 1945, near Prüm in Germany. In recognition of his natural leadership abilities, he ended the war as the acting first sergeant for Headquarters Company, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment. McNiece would be kicked out of the military in February 1946 after fighting with MP’s. In 1949, McNiece returned to live in Ponca City. He began a 28-year career with the United States Postal Service. His first wife Rosita died in 1952 and, a year later, he married Martha Beam Wonders. They had two sons and a daughter and remained married until his death at age 93.

#second world war#world war 2#world war ii#wwii#military history#american military#army airborne#native american#biography#normandy#market garden

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

D-Day was 80 years ago today!

D-Day was the first day of Operation Overlord, the Allied attack on German-occupied Western Europe, which began on the beaches of Normandy, France, on 6 June 1944. Primarily US, British, and Canadian troops, with naval and air support, attacked five beaches, landing some 135,000 men in a day widely considered to have changed history.

Where to Attack?

Operation Overlord, which sought to attack occupied Europe starting with an amphibious landing in northwest France, Belgium, or the Netherlands, had been in the planning since January 1943 when Allied leaders agreed to the build-up of British and US troops in Britain. The Allies were unsure where exactly to land, but the requirements were simple: as short a sea crossing as possible and within range of Allied fighter cover. A third requirement was to have a major port nearby, which could be captured and used to land further troops and equipment. The best fit seemed to be Normandy with its flat beaches and port of Cherbourg.

The Atlantic Wall

The leader of Nazi Germany, Adolf Hitler (1889-1945), called his western line of defences the Atlantic Wall. It had gaps but presented an impressive string of fortifications along the coast from Spain to the Netherlands. Construction of gun batteries, bunker networks, and observation posts began as early as 1942.

Many of the German divisions were not crack troops but inexperienced soldiers, who were spending more time building defences than in vital military training. There was a woeful lack of materials for Hitler's dream of the Atlantic Wall, really something of a Swiss cheese, with some strong areas, but many holes. The German army was not provided with sufficient mines, explosives, concrete, or labourers to better protect the coastline. At least one-third of gun positions still had no casement protection. Many installations were not bomb-proof. Another serious weakness was naval and air support. The navy had a mere 4 destroyers available and 39 E-boats while the Luftwaffe's (German Air Force's) contribution was equally paltry with only 319 planes operating in the skies when the invasion took place (rising to 1,000) in the second week.

Neptune to Normandy

Preparation for Overlord occurred right through April and May of 1940 when the Royal Air Force (RAF) and United States Air Force (USAAF) relentlessly bombed communications and transportation systems in France as well as coastal defences, airfields, industrial targets, and military installations. In total, over 200,000 missions were conducted to weaken as much as possible the Nazi defences ready for the infantry troops about to be involved in the largest troop movement in history. The French Resistance also played their part in preparing the way by blowing up train lines and communication systems that would ensure the defenders could not effectively respond to the invasion.

The Allied fleet of 7,000 vessels of all kinds departed from English south-coast ports such as Falmouth, Plymouth, Poole, Portsmouth, Newhaven, and Harwich. In an operation code-named Neptune, the ships gathered off Portsmouth in a zone called 'Piccadilly Circus' after the busy London road junction, and then made their way to Normandy and the assault areas. At the same time, gliders and planes flew to the Cherbourg peninsula in the west and Ouistreham on the eastern edge of the planned landing. Paratroopers of the 82nd and 101st US Airborne Division attacked in the west to try and cut off Cherbourg. At the eastern extremity of the operation, paratroopers of the 6th British Airborne Division aimed to secure Pegasus Bridge over the Caen Canal. Other tasks of the paratrooper and glider units were to destroy bridges to impede the enemy, hold others necessary for the invasion to progress, destroy gun emplacements, secure the beach exits, and protect the invasion's flanks.

The Beaches

The amphibious attack was set for dawn on 5 June, daylight being a requirement for the necessary air and naval support. Bad weather led to a postponement of 24 hours. Shortly after midnight, the first waves of 23,000 British and American paratroopers landed in France. US paratroopers who dropped near Ste-Mère-Église ensured this was the first French town to be liberated. From 3.00 a.m., air and naval bombardment of the Normandy coast began, letting up just 15 minutes before the first infantry troops landed on the beaches at 6.30 a.m.

The beaches selected for the landings were divided into zones, each given a code name. US troops attacked two, the British army another two, and the Canadian force the fifth. These beaches and the troops assigned to them were (west to east):

Utah Beach - 4th US Infantry Division, 7th US Corps (1st US Army commanded by Lieutenant General Omar N. Bradley)

Omaha Beach - 1st US Infantry Division, 5th US Corps (1st US Army)

Gold Beach - 50th British Infantry Division, 30th British Corps (2nd British Army commanded by Lieutenant-General Miles C. Dempsey)

Juno Beach - 3rd Canadian Infantry Division (2nd British Army)

Sword Beach - 3rd British Infantry Division, 1st British Corps (2nd British Army)

In addition, the 2nd US Rangers were to attack the well-defended Pointe du Hoc between Utah and Omaha (although it turned out the guns had never been installed there), while Royal Marine Commando units attacked targets on Gold, Juno, and Sword.

The RAF and USAAF continued to protect the invasion fleet and ensure any enemy ground-based counterattack faced air attack. As the Allies could put in the air 12,000 aircraft at this stage, the Luftwaffe's aerial fightback was pitifully inadequate. On D-Day alone, the Allied air forces flew 15,000 sorties compared to the Luftwaffe's 100. Not one single Allied aircraft was lost to enemy fire on D-Day.

Packing Normandy

By the end of D-Day, 135,000 men had been landed and relatively few casualties were sustained – some 5,000 men. There were some serious cock-ups, notably the hopeless dispersal of the paratroopers (only 4% of the US 101st Air Division were dropped at the intended target zone), but, if anything, this caused even more confusion amongst the German commanders on the ground as it seemed the Allies were attacking everywhere. The defenders, overcoming the initial handicap that many area commanders were at a strategy conference in Rennes, did eventually organise themselves into a counterattack, deploying their reserves and pulling in troops from other parts of France. This is when French resistance and aerial bombing became crucial, seriously hampering the German army's effort to reinforce the coastal areas of Normandy. The German field commanders wanted to withdraw, regroup and attack in force, but, on 11 June, Hitler ordered there be no retreat.

All of the original invasion beaches were linked as the Allies pushed inland. To aid thousands more troops following up the initial attack, two artificial floating harbours were built. Code-named Mulberries, these were located off Omaha and Gold beaches and were built from 200 prefabricated units. A storm hit on 20 June, destroying the Mulberry Harbour off Omaha, but the one at Gold was still serviceable, allowing some 11,000 tons of material to be landed every 24 hours. The other problem for the Allies was how to supply thousands of vehicles with the fuel they needed. The short-term solution, code-named Tombola, was to have tanker ships pump fuel to storage tanks on shore, using buoyed pipelines. The longer-term solution was code-named Pluto (Pipeline Under the Ocean), a pipeline under the Channel to Cherbourg through which fuel could be pumped. Cherbourg was taken on 27 June and was used to ship in more troops and supplies, although the defenders had sunk ships to block the harbour and these took some six weeks to fully clear.

Operation Neptune officially ended on 30 June. Around 850,000 men, 148,800 vehicles, and 570,000 tons of stores and equipment had been landed since D-Day. The next phase of Overlord was to push the occupiers out of Normandy. The defenders were not only having logistical problems but also command issues as Hitler replaced Rundstedt with Field Marshal Günther von Kluge (1882-1944) and formally warned Rommel not to be defeatist.

Aftermath: The Normandy Campaign

By early July, the Allies, having not got further south than around 20 miles (32 km) from the coast, were behind schedule. Poor weather was limiting the role of aircraft in the advance. The German forces were using the countryside well to slow the Allied advance – countless small fields enclosed with trees and hedgerows which limited visibility and made tanks vulnerable to ambush. Caen was staunchly defended and required Allied bombers to obliterate the city on 7 July. The German troops withdrew but still held one-half of the city. The Allies lost around 500 tanks trying to take Caen, vital to any push further south. The advance to Avranches was equally tortuous, and 40,000 men were lost in two weeks of heavy fighting. By the end of July, the Allies had taken Caen, Avranches, and the vital bridge at Pontaubault. From 1 August, Patton and the US Third Army were punching south at the western side of the offensive, and the Brittany ports of St. Malo, Brest, and Lorient were taken.

German forces counterattacked to try and retake Avranches, but Allied air power was decisive. Through August 1940, the Allies swept southwards to the Loire River from St. Nazaire to Orléans. On 15 August, a major landing took place on the southwest coast of France (French Riviera landings) and Marseille was captured on 28 August. In northern France, the Allies captured enough territory, ports, and airfields for a massive increase in material support. On 25 August, Paris was liberated. By mid-September, the Allied troops in the north and south of France had linked up and the campaign front expanded eastwards pushing on to the borders of Germany. There would be setbacks like Operation Market Garden of September and a brief fightback at the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944, but the direction of the war and ultimate Allied victory was now a question of not if but when.

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

On 17th August 2010 Bill Millin, piper to Lord Lovat at D Day, died, aged 88.

Millin had left Sandyhills near Glasgow to join the Highland Light Infantry, Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders, No. 4 Commando.

On June 6th 1944, the 21-year-old had been ordered to play against the wishes of the top brass. He was the personal piper to Lord Lovat - who, despite there being a ban on pipers being allowed on the frontline, defied the War Office's orders and brought him to Sword Beach.

Pipers were banned from being on the frontline during the Second World War because of the number of casualties seen during the First World War. The enemy figured out that the piper helped boost morale to the Allied troops, and they were slaughtered because of this. This led the War Office to restrict their presence in camps as well as on the frontline.

After the war Bill settled in the lovely wee devon town of Dawlish, the museum there has his pipes on display as seen in the second pic, the first shows Bill at Edinburgh Castle in 2003.

The first pic is Bill, reunited with Josette Gouellain in Ranville, Normandy. The two met 50 years ago when Josette asked bill to play something just for her. The Scot complied with "The Nut Brown Maiden" in admiration of the little girl's hair and eyes.

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Tunison Foundation's 1943 Douglas C-47 Skytrain "Placid Lassie" - Oshkosh 2022

Unlike many warbirds operating today, she is a real war hero. She is not a replica, or a deep restoration based upon parts from multiple separate airplanes. These same rivets crossed the English Channel on June 6th, 1944 and continued across Europe in service of our country.

#Douglas#C-47#Skytrain#cargo plane#transport#troop carrier#vintage aircraft#WW2 transport#airshow#Oshkosh#AirVenture#Placid Lassie#plane#aircraft#Historic aircraft#warbird

96 notes

·

View notes

Note

what's the timeline regarding when tom opened the chamber of secrets vs when he killed his father? it's around the same time right? do we hav exact sequence in canon? do you. have ideas about it?

Okay, so let's go through the timeline of Tom Riddle's life at Hogwarts:

(I love talking about Tom Riddle, can you tell?)

So, Tommy was born on December 31st, 1926.

This means he'd celebrate his 11th birthday on December 31st, 1937, so he'd start his first year at Hogwarts on September 1st, 1938.

And Tom says this:

I thought someone must realize that Hagrid couldn’t possibly be the Heir of Slytherin. It had taken me five whole years to find out everything I could about the Chamber of Secrets and discover the secret entrance . . .

(CoS, 288)

So, he would be in his 5th year when he first opened the Chamber of Secrets. From the math above, his 5th year started in September 1942 and ended in June 1943.

We know Myrtle died on June 13th, 1943, so right at the end of Tom's 5th year at school (fitting the "five whole years" statement). When Tom shows Harry the memory of Myrtle's death it's on the diary page for June 13th:

The pages of the diary began to blow as though caught in a high wind, stopping halfway through the month of June. Mouth hanging open, Harry saw that the little square for June thirteenth seemed to have turned into a minuscule television screen

(CoS, 225)

Tom then asks Dippet to stay at Hogwarts, which Dipept declines. I also assume June 1943 is when Tom turns the diary into a Horcrux.

Now, we know that the summer Tom is sixteen (he turned sixteen in December 1942), the summer between his 5th and 6th year (July-Agust of 1943), is when he killed his father and stole the Gaunt ring:

Finally, after painstaking research through old books of Wizarding families, he discovered the existence of Slytherin’s surviving line. In the summer of his sixteenth year, he left the orphanage to which he returned annually and set off to find his Gaunt relatives. And now, Harry, if you will stand . . .”

(HBP, 363)

We see that by 6th year (1943-1944), Tom already has the Gaunt ring:

Half a dozen boys were sitting around Slughorn, all on harder or lower seats than his, and all in their mid-teens. Harry recognized Voldemort at once. His was the most handsome face and he looked the most relaxed of all the boys. His right hand lay negligently upon the arm of his chair; with a jolt, Harry saw that he was wearing Marvolo’s goldand-black ring; he had already killed his father.

(HBP, 369)

This means by the time he had his talk with Sughorn he had two Horcruxes: the diary and the ring. In the scene with Slughorn Harry mentions Tom isn't the oldest student and he's referred to by Slughorn as a prefect, not a head boy, so it's not his 7th year.

I have a whole series about Tom Riddle and I talked more about this timeline situation there. But this is an overview of his Hogwarts timeline.

#harry potter#hp#hp thoughts#hp meta#harry potter meta#voldemort#lord voldemort#tom riddle#tom marvolo riddle#voldemort analysis#hollowedtheory

87 notes

·

View notes