#30 April 1885

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Governor of New York David B. Hill signed legislation creating the Niagara Reservation, New York’s first state park on April 30, 1885, ensuring that Niagara Falls will not be devoted solely to industrial and commercial use.

#Governor of New York#legislation#Niagara Reservation#Niagara Falls#30 April 1885#anniversary#US history#Ontario#Canada#travel#summer 2018#Horseshoe Falls#American Falls#Bridal Veil Falls#water#landmark#tourist attraction#landscape#cityscape#original photography#flower#flora#nature#Goat Island Bridge#Niagara River#waterfall#vacation#2009#2012#USA

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE WORLD'S FIRST ELECTRIC ROLLER COASTER

Granville T. Woods (April 23, 1856 – January 30, 1910) introduced the “Figure Eight,” the world's first electric roller coaster, in 1892 at Coney Island Amusement Park in New York. Woods patented the invention in 1893, and in 1901, he sold it to General Electric.

Woods was an American inventor who held more than 50 patents in the United States. He was the first African American mechanical and electrical engineer after the Civil War. Self-taught, he concentrated most of his work on trains and streetcars.

In 1884, Woods received his first patent, for a steam boiler furnace, and in 1885, Woods patented an apparatus that was a combination of a telephone and a telegraph. The device, which he called "telegraphony", would allow a telegraph station to send voice and telegraph messages through Morse code over a single wire. He sold the rights to this device to the American Bell Telephone Company.

In 1887, he patented the Synchronous Multiplex Railway Telegraph, which allowed communications between train stations from moving trains by creating a magnetic field around a coiled wire under the train. Woods caught smallpox prior to patenting the technology, and Lucius Phelps patented it in 1884. In 1887, Woods used notes, sketches, and a working model of the invention to secure the patent. The invention was so successful that Woods began the Woods Electric Company in Cincinnati, Ohio, to market and sell his patents. However, the company quickly became devoted to invention creation until it was dissolved in 1893.

Woods often had difficulties in enjoying his success as other inventors made claims to his devices. Thomas Edison later filed a claim to the ownership of this patent, stating that he had first created a similar telegraph and that he was entitled to the patent for the device. Woods was twice successful in defending himself, proving that there were no other devices upon which he could have depended or relied upon to make his device. After Thomas Edison's second defeat, he decided to offer Granville Woods a position with the Edison Company, but Woods declined.

In 1888, Woods manufactured a system of overhead electric conducting lines for railroads modeled after the system pioneered by Charles van Depoele, a famed inventor who had by then installed his electric railway system in thirteen United States cities.

Following the Great Blizzard of 1888, New York City Mayor Hugh J. Grant declared that all wires, many of which powered the above-ground rail system, had to be removed and buried, emphasizing the need for an underground system. Woods's patent built upon previous third rail systems, which were used for light rails, and increased the power for use on underground trains. His system relied on wire brushes to make connections with metallic terminal heads without exposing wires by installing electrical contactor rails. Once the train car had passed over, the wires were no longer live, reducing the risk of injury. It was successfully tested in February 1892 in Coney Island on the Figure Eight Roller Coaster.

In 1896, Woods created a system for controlling electrical lights in theaters, known as the "safety dimmer", which was economical, safe, and efficient, saving 40% of electricity use.

Woods is also sometimes credited with the invention of the air brake for trains in 1904; however, George Westinghouse patented the air brake almost 40 years prior, making Woods's contribution an improvement to the invention.

Woods died of a cerebral hemorrhage at Harlem Hospital in New York City on January 30, 1910, having sold a number of his devices to such companies as Westinghouse, General Electric, and American Engineering. Until 1975, his resting place was an unmarked grave, but historian M.A. Harris helped raise funds, persuading several of the corporations that used Woods's inventions to donate money to purchase a headstone. It was erected at St. Michael's Cemetery in Elmhurst, Queens.

LEGACY

▪Baltimore City Community College established the Granville T. Woods scholarship in memory of the inventor.

▪In 2004, the New York City Transit Authority organized an exhibition on Woods that utilized bus and train depots and an issue of four million MetroCards commemorating the inventor's achievements in pioneering the third rail.

▪In 2006, Woods was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

▪In April 2008, the corner of Stillwell and Mermaid Avenues in Coney Island was named Granville T. Woods Way.

519 notes

·

View notes

Text

I figured out what train Mikoto takes in Double

But before I get into the meat of this, let me explain how I'm doing this post. First, I'll be going over the basics. I will be then going over everything that has been bolded.

There will be a part 2 to this post where I try to triangulate his actions through out MeMe.

So I started at Shibuya Station since the image on his mugshot board was taken in Shibuya.

I then narrowed it down to the Saikyō Line or the Yamanote Line. Both of which are standard commuter lines operated by JR East. So then I looked at what the trains look like and the train that is currently in use for the Yamanote Line looks almost identical to the one in Double.

The train that is currently in use is the E235 series which was first rolled out on November 30th 2015 and recalled the same day due to a number of issues including problems with door close indicators. It was later reintroduced on March 7th 2016. As of January 20th 2020, it has been the only type on train in service on the Yamanote Line.

The line is known to be overcrowded due to being a circle and hitting all of the major locations in Tokyo. It starts and ends most commonly at Ōsaki Station in Shinagawa but can also start/stop at Ikebukuro Station in Toshima. Some trains start from Tamachi Station in Minato in the mornings and end at Shinagawa Station in Minato in the evenings. Trains run from 04:26 to 01:04 the next day and there are a total of 30 stations in the loop. The outside of the loop gose clockwise and the inside goes counter clockwise.

Yamanote roughly translates to foothills. After WW2, all of the train place cards were romanized, and because 山手 reads as Yamate, the line was mistranslated until the 70s.

All of the stations located in the Shibuya Ward are Ebisu, Shibuya, Harajuku and Yoyogi. Part of the line is shared with the Tōhoku and Tōkaidō Main Lines. From Tabata Station in Kita to Tōkyō Station in Chiyoda are shared by the Tōhoku Main Line. From Yūrakuchō Station in Chiyoda to Takanawa Gateway Station in Minato are shared by the Tōkaidō Main Line.

The line was first was opened on March 1st 1885, operating between Shinagawa Station in Minato and Akabane Station in Kita. The second part was opened on April 1st 1903, operating between Ikebukuro Station in Toshima and Tabata Station in Kita as a seperate line. On October 12th 1909, the 2 lines were merged, which created the present day Yamanote line. The full loop was completed in 1919 with the addition of Tōkyō Station in Chiyoda, and 1925 with the addition of Akihabara Station in Chiyoda.

The picture on his card is specifically from Ebisu. But the station seen in Double doesn't match up with the Yamanote Line platforms as they are island platforms, not side platforms. If he was at Ebisu Station, He would likely be at JR platform 1. This one is directed to Shibuya, Shinjuku and Ikebukuro. Shibuya only has island platforms and one of Yoyogi's and Harajuku's platforms are also islands. Out of the remaining platforms in the Shibuya portion of the line, Harajuku platform 2 looks the closest. It would also make sense that he would be in Harajuku due to his interests.

The line being a circle makes sense with the theme of Double; a never ending train that never stops. And the technical issues with the doors adds to this feeling of being trapped. The train also being overcrowded matches up with what it's like in the beginning of Double. However, the train soon is completely empty.

#milgram#ミルグラム#milgram project#mikoto kayano#kayano mikoto#milgram analysis#fools mate research#milgram theory

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Titus Flavius and his indelible traces.

Titus Flavius was born in Rome on December 30 of the year 39. He was a direct descendant of a loyal soldier of Pompey the Great during the Civil War against Julius Caesar. After Pompey's defeat at the Battle of Pharsalia, his life was spared by Julius Caesar, returned to home and became a Publicanus (tax collector). In an incredible twist of fate, the Flavians, a family of peasants, who came from the defeat of the past, ended up occupying the throne founded by Caesar's heir.

During reign of 'Caligula' (37-41) Vespasian, father of Titus, was Aedile of Rome. According Suetonius, Emperor passed by a street that was very dirty, ordered Vespasian to be brought and the garbage thrown on him, and then told him "Do your job well, keep the city clean."

During the reign of Claudius (41-54) Vespasian obtained the position of praetor and the command of one of the legions that went to the conquest of Britannia. In 51 was Consul.

After rebellion in Judea in the year 66, emperor Nero chose the experienced general Vespasian to put an end to the conflict. Vespasian went with his son, Titus, who was then 26 years old, and was an excellent army's officer.

In June 68, after of the death of Nero, the first civil war of the imperial era broke out, which would last until December of the following year. In the chaotic year 69, known as The Year of the 4 emperors: the first ,Galba was assassinated; the second, Otho committed suicide; the third, Vitellius, was executed, the fourth, Vespasian was proclaimed emperor by the army, ending the civil war. Titus was left in command against the rebellion in Judea.

The war in Judea was halted for a year- while Vespasian waged civil war against Vitellius- and resumed in early 70, when Vespasian had secured his position as emperor.

During his father's reign, Titus served as consul seven times and also assumed the command of the praetorian guard.

A historical event of mystical relevance.

After months of bloody fighting, on August of the year 70, the Temple of Jerusalem was looted, burned and demolished by Titus's troops.

'The destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem', By Francesco Hayez 1867

Titus along his father and brother had a triumphal parade in Rome. Years later, in the place where they passed, his younger brother, the Emperor Domitian, ordered the construction of the Triumphal Arch. One of its extraordinary relief depicts the Triumph with the treasures of the Temple. It should be noted that Vespasian and his two sons had the name TITUS FLAVIUS, so emperor Domitian (Titus Flavius Domitian) built the famous Arch of Titus not necessarily in honour of his brother - as is popularly believed - but rather in honour of the Triumph of the Flavians.

Some modern historians agree that such a Triumph was not due to what happened in Jerusalem, since the First Jewish–Roman War did not really end completely in August 70, but in April 73 at Masada. The real reason was the accession to the throne of Vespasian, and the presentation of Titus as heir. As Dio Cassius recounts, with Vespasian declared emperor, Titus and his brother Domitian received the title of Caesar in the name of the Senate.

But Vespasian become emperor by defeating other Romans in a civil war. Triumphal parades could not be held by defeating other Romans, so the rebellion in Judea was just a perfect excuse for the celebration.

'The Triumph of Titus: The Flavians' By Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1885)

The central figure in white (pontifex maximus) is not Titus but his father Vespasian. Behind him we see his youngest son Domitian, holding the hand of his wife Domitia Longina, and behind them is Titus, dressed as his father. She looks romantically at Titus, and he returns a knowing look. Lawrence Alma-Tadema thus portrayed the historical rumour that Emperor Titus Flavius was having an affair with his sister-in-law.

Vespasian decided to tear down the Domus Aurea, the palace that Nero had ordered to be built for his own enjoyment, and build "a palace for the enjoyment of the people". He saw his work almost completed but died of illness on June 23, 79, at his estate. The next day Titus Flavius succeeded him.

A mess with the gods.

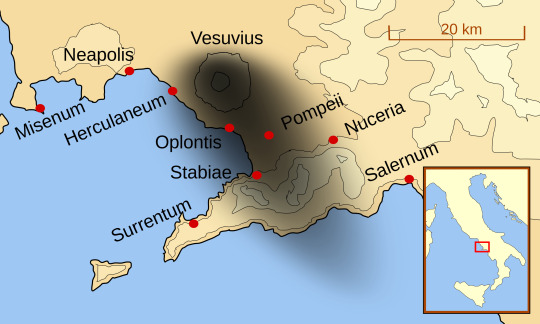

Four months later a tragic event occurred. The peaceful mount Vesuvius exploded. Among the dead was the prestigious writer and Naval Commander Pliny the Elder, a close friend of the imperial family, who had dedicated his book 'Naturalis historia' to Titus.

"There were some dreadful disasters during his reign, such as the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in Campania, a fire at Rome which continued three days and as many nights, and a plague the like of which had hardly ever been known before. In these many great calamities he showed not merely the concern of an emperor, but even a father's surpassing love, now offering consolation in edicts, and now lending aid so far as his means allowed. He chose commissioners by lot from among the ex-consuls for the relief of Campania; and the property of those who lost their lives by Vesuvius and had no heirs left alive he applied to the rebuilding of the buried cities." -Suetonius (The Lives of the Twelve Caesars ;Titus).

Soon rumors began to circulate that the gods had a personal problem with Titus because of his forbidden love for Princess Berenice, great-great-granddaughter of Herod the Great.

Although he was a very popular emperor, he did not want to risk those tragedies affecting his image, so he decided in the year 80 to accelerate his father's work, which still had to wait to be completed. And so began the inauguration of the most famous amphitheater in history.

Very soon the people of Rome forgot about Vesuvius, the conflagration, the plague, and Berenice. There were 100 days of games: Recreations of naval battles, with that monumental site full of water, exhibitions of wild animals and the legendary gladiator fights. Those shows were free for the people.

They had never seen an amphitheater of such grandeur.

Its height and shape were a real architectural novelty, something completely different from the classic Roman amphitheatres. Because of the sculpture, Nero's Colossus, the only thing that Vespasian did not order to be demolished and that remained imposing next to the amphitheatre, over time people began to say "let's go to the Colossus" (the Colosseum). Ironically, the great work that Vespasian ordered to be built to replace the Domus Aurea, and Titus officially inaugurated, instead of being known as the Amphitheatre Flavius, went down in history with the name of the sculpture that Nero ordered to be built.

A sesterce from the time of Emperor Titus.

The pseudo-Nero

After Nero's death, rumors began to circulate that his suicide was not real. Years later, this rumor had spread throughout the empire and even beyond its borders. Suetonius wrote about an event that he experienced during the reign of Domitian: "Twenty years after his death, when I was young, a man of obscure origin appeared, who claimed he was Nero; And the name Nero was still in such favour with the Parthians that they supported him vigorously and surrendered him with great reluctance."

The Parthians were happy believing that Nero was alive because during his reign he signed the peace treaty.

Titus had to face the rebellion of a guy called Terentius Maximus, another Pseudo-Nero that according Dio Cassius "He resembled Nero in voice and appearance and, like him, he played the lyre." The impostor had a lot of followers in the eastern Roman provinces. The Parthian king received this man and made preparations for him to return to Rome as legitime emperor but he was executed when his true identity was revealed.

On September 13, 81, Titus died at the age of 41 on his father's farm, due to fever. His brief reign was very prosperous and popular and free of military and political conflicts. Having only a daughter (Julia Flavia), his successor was his brother Domitian who ruled for 15 years.

According to Roman writers, his last words were: "I regret nothing except one thing"; And some believe that he regretted not marrying Berenice.

The Colosseum and the Wailing Wall are undoubtedly the two indelible traces of Titus Flavius.

230 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rudolf Klein-Rogge, November 24, 1885 - April 30, 1955.

Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927).

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE WORLD'S FIRST ELECTRIC ROLLER COASTER

Granville T. Woods (April 23, 1856 – January 30, 1910) introduced the “Figure Eight,” the world's first electric roller coaster, in 1892 at Coney Island Amusement Park in New York. Woods patented the invention in 1893, and in 1901, he sold it to General Electric.

Woods was an American inventor who held more than 50 patents in the United States. He was the first African American mechanical and electrical engineer after the Civil War. Self-taught, he concentrated most of his work on trains and streetcars.

In 1884, Woods received his first patent, for a steam boiler furnace, and in 1885, Woods patented an apparatus that was a combination of a telephone and a telegraph. The device, which he called "telegraphony", would allow a telegraph station to send voice and telegraph messages through Morse code over a single wire. He sold the rights to this device to the American Bell Telephone Company.

In 1887, he patented the Synchronous Multiplex Railway Telegraph, which allowed communications between train stations from moving trains by creating a magnetic field around a coiled wire under the train. Woods caught smallpox prior to patenting the technology, and Lucius Phelps patented it in 1884. In 1887, Woods used notes, sketches, and a working model of the invention to secure the patent. The invention was so successful that Woods began the Woods Electric Company in Cincinnati, Ohio, to market and sell his patents. However, the company quickly became devoted to invention creation until it was dissolved in 1893.

Woods often had difficulties in enjoying his success as other inventors made claims to his devices. Thomas Edison later filed a claim to the ownership of this patent, stating that he had first created a similar telegraph and that he was entitled to the patent for the device. Woods was twice successful in defending himself, proving that there were no other devices upon which he could have depended or relied upon to make his device. After Thomas Edison's second defeat, he decided to offer Granville Woods a position with the Edison Company, but Woods declined.

In 1888, Woods manufactured a system of overhead electric conducting lines for railroads modeled after the system pioneered by Charles van Depoele, a famed inventor who had by then installed his electric railway system in thirteen United States cities.

Following the Great Blizzard of 1888, New York City Mayor Hugh J. Grant declared that all wires, many of which powered the above-ground rail system, had to be removed and buried, emphasizing the need for an underground system. Woods's patent built upon previous third rail systems, which were used for light rails, and increased the power for use on underground trains. His system relied on wire brushes to make connections with metallic terminal heads without exposing wires by installing electrical contactor rails. Once the train car had passed over, the wires were no longer live, reducing the risk of injury. It was successfully tested in February 1892 in Coney Island on the Figure Eight Roller Coaster.

In 1896, Woods created a system for controlling electrical lights in theaters, known as the "safety dimmer", which was economical, safe, and efficient, saving 40% of electricity use.

Woods is also sometimes credited with the invention of the air brake for trains in 1904; however, George Westinghouse patented the air brake almost 40 years prior, making Woods's contribution an improvement to the invention.

Woods died of a cerebral hemorrhage at Harlem Hospital in New York City on January 30, 1910, having sold a number of his devices to such companies as Westinghouse, General Electric, and American Engineering. Until 1975, his resting place was an unmarked grave, but historian M.A. Harris helped raise funds, persuading several of the corporations that used Woods's inventions to donate money to purchase a headstone. It was erected at St. Michael's Cemetery in Elmhurst, Queens.

LEGACY

▪Baltimore City Community College established the Granville T. Woods scholarship in memory of the inventor.

▪In 2004, the New York City Transit Authority organized an exhibition on Woods that utilized bus and train depots and an issue of four million MetroCards commemorating the inventor's achievements in pioneering the third rail.

▪In 2006, Woods was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

▪In April 2008, the corner of Stillwell and Mermaid Avenues in Coney Island was named Granville T. Woods Way.

#granville t woods#black inventor#invented#world's first#electric roller coaster#1893#read about him#read about his invention#reading is fundamental#knowledge is power#black history

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

❤️𝕳𝖆𝖕𝖕𝖞 𝕭𝖎𝖗𝖙𝖍𝖉𝖆𝖞 𝕽𝖚𝖉𝖔𝖑𝖋 𝕶𝖑𝖊𝖎𝖓-𝕽𝖔𝖌𝖌𝖊! ❤️

(November 24, 1885 - April 30, 1955)

#rudolf klein-rogge#birthday remembrance#born on this day#1920s#cinema#german actor#silent era#silent film stars#dr. mabuse the gambler#metropolis (1927)#I adore him sm#my post

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Still liable to changes, but I have at last placed every single story into my chronology! I have also made some changes to the order of stories placed previously, based either on new information or their vibes. Comments and feedback are much appreciated.

The ‘Gloria Scott’ - Summer 1875 [1] (Framing: Winter 1882-3?)

The maths as stated don’t work, as 1855 + 30 = 1885, and these events can’t occur after A Study In Scarlet. 1875 would have to be Holmes’s second year of college.

The Musgrave Ritual - Spring 1879 (Framing: Winter 1882-3?)

It is stated to have been four years since Holmes last saw Musgrave. Holmes mentions telling Watson about the events of ‘Gloria Scott’. Watson must be living at 221b at the time, as his intro describes Holmes’s extremely messy habits in terms of lodging with him.

A Study In Scarlet - January to March 1881

Watson states the date he discovered Holmes’s profession explicitly as the 4th of March, which was several weeks after they moved in together. I find it likely that it was at most mid-January when they met, and that Watson spent February observing Holmes’s habits and trying to figure him out.

The Resident Patient - October 1881

Watson describes these events as being ‘towards the end of the first year during which Holmes and I shared chambers’, and then specifies that it was October.

The Valley Of Fear - January 1882 [2]

It is stated to be ‘in the late eighties’, but Holmes appears to still be getting used to Watson’s sense of humour, which he claims is ‘developing’, which points to it being earlier while Watson is still recovering from his illness. Any later and Holmes would already be very familiar with his closest companion’s personality. It cannot be any earlier than 1882 however, since January 1881 is taken up by the events of A Study In Scarlet.

The Speckled Band - April 1883

The Yellow Face - Summer 1883

The Beryl Coronet - February 1884

The Copper Beeches - Early Spring 1884

Charles Augustus Milverton - Winter 1884

I get the feeling this is an earlier case, as Watson’s attitude is oddly naïve when it comes to morality and the ability of the law to handle Milverton. I cannot see him behaving like this/holding these beliefs if he has already experienced Moriarty with Holmes for instance. He is also very jumpy while he and Holmes are performing their burglary.

The Hound Of The Baskervilles - October 1885 [3]

Mortimer’s stick is dated 1884, and Holmes notes this was five years ago (making it 1889), but Watson neither appears to be married nor in medical practice, and since this story was explicitly written as to have occurred before Holmes’s ‘death’, this precludes it being set after 1888.

The Greek Interpreter - Summer 1886?

The Reigate Squires - April 1887

The Sign Of Four - July 1887 [4]

It is stated to be July (later mistakenly stated as September) 1888, but this contradicts both SCAN (March 1888) and FIVE (September 1887). There also appears to be a pearl missing as Mary describes their delivery.

The Cardboard Box - August 1887

Holmes mentions both A Study In Scarlet and The Sign Of Four by name -- which implies that Watson is a very speedy writer, as this would be only a few weeks later. However, this may be taken as self promotion on Watson’s part.

The Noble Bachelor - Autumn 1887

This story is dated to 1887 via Lord St. Simon’s age, but Watson is soon to be married -- which is not possible if he has not yet met his fiancée. Dating SIGN to July 1887 fixes this discrepancy.

A Scandal In Bohemia - March 1888

Watson explicitly dates the start of this case to the 20th of March 1888, and states that he hasn’t seen Holmes for several months after his marriage (which would be in the late autumn to winter of 1887)

The Stockbroker’s Clerk - June 1888

Watson states that he acquired his practice ‘shortly after’ his marriage, and that he was too busy to visit Holmes at Baker Street for three months. Counting most of March as the first month (per SCAN), that takes us to the June he states, which is the first time Holmes has visited Watson at his practice.

The Naval Treaty - July 1888

[The Second Stain - July 1888**]

I take it that the story of this name is heavily if not entirely fictionalised. This is when the real events that inspired it occurred.

The Crooked Man - Summer (August?) 1888

The Five Orange Pips - September 1888 [5]

It is stated to be September 1887, but even if SIGN occurred in July of that year, Watson and Mary have not married yet for him to be ‘staying at Baker Street’ while she is away visiting her (dead) mother.

The Boscombe Valley Mystery - Spring 1889

The Man With The Twisted Lip - June 1889

I place this after BOSC, as Holmes takes it as a given that Watson’s wife will not object to him sending a note and running off on a case in the middle of the night. (I suspect he’s wrong and will be due a bollocking after breakfast)

The Engineer’s Thumb - Summer 1889

The Dying Detective - November 1889

Watson describes this as happening in his ‘second year of marriage’, which, 1888 being his first, works out as 1889.

A Case Of Identity - September 1890

Holmes comments in REDH that the case of Mary Sutherland occurred ‘the other day’.

The Red-Headed League - October 1890

The Blue Carbuncle - December 1890

Watson states it to be ‘the second morning after Christmas’, making it the 27th. When discussing cases that didn’t involve a crime, Holmes cites the events of SCAN, IDEN, and TWIS. This also lines up with the publication order, BLUE being the seventh short story, and Watson states that of the ‘last six cases’ he has written up, three of them were legally free of crime (morally however…)

The Final Problem - April to May 1891

Holmes has apparently been working in France since ‘the winter of 1890’ when he suddenly shows up in Watson’s consulting room on the 24th of April. His ‘death’ occurs on the 4th of May.

The Empty House - March 1894

The Norwood Builder - Summer 1894

Stated to take place ‘several months’ after Holmes’s return. Watson has moved back to Baker Street and sold his practice.

Silver Blaze - Late Summer 1894

(I would like to set Silver Blaze to be after NORW, since I think Holmes and Watson deserve a fun case after that one. I believe it to be post-hiatus since Watson is evidently resident in Baker Street and does not appear to be in practice at this time.)

The Golden Pince-Nez - November 1894

The Red Circle - Winter 1894

Watson is living at Baker Street, and Holmes refers to his medical practice in the past tense.

The Solitary Cyclist - April 1895

The Three Students - 1895

Black Peter - July 1895

The Bruce-Partington Plans - November 1895

The Veiled Lodger - Early 1896

The Shoscombe Old Place - 1896

The Missing Three-Quarter - February 1896-7?

Described as occurring ‘seven or eight years ago’ from the time of writing, presumably 1904.

The Devil’s Foot - March 1897

The Abbey Grange - Winter 1897

Wisteria Lodge - March 1898 [6]

It is stated to be March 1892, but this is impossible as Holmes is presumed dead at that time. It also can’t be March ‘91 as Holmes is too busy at that time, and referencing REDH eliminates March ‘90 or any year earlier. Further, Holmes complains of boredom due to a lack of cases, which eliminates 1894 due to a very high number of cases in that year (he also would only have been back about two weeks at that point). Holmes is also busy in March ‘95, ‘96, and ‘97. It is not until 1898 that there may be time to be bored by March.

The Six Napoleons - Late May/Early June 1898

It must be the end of May or the start of June, as Beppo was arrested and sentenced to a year in prison in late May of the previous year. (I’d like to set this one near DANC, since Holmes deserves the praise.

The Dancing Men - July 1898

Mr Cubitt says that he met his wife while in London ‘for the jubilee last year’, and that Elsie received a letter from America ‘about a month ago, at the end of June’.

The Sussex Vampire - November 1898

I date this story to after 1897, as that is the year vampires rose significantly in the public consciousness.

The Retired Colourman - Summer 1899

Amberley married his wife in 1897, and Holmes comments that the events that have resulted in their contact with him have occurred ‘within two years’.

The Priory School - May 1901?

Years listed with regard to Lord Holdernesse date the story post 1900, and wording makes it seem that that is not the present year.

The Disappearance of Lady Frances Carfax - Spring/Summer 1901?

The Problem Of Thor Bridge - October 1901

The Three Garridebs - June 1902

The Illustrious Client - September 1902

The Blanched Soldier - January 1903

Holmes claims that Watson has ‘deserted [him] for a wife’.

The Mazarin Stone - Summer 1903

Watson is visiting Baker Street, and comments that nothing has changed in his absence, which infers this to occur after his second marriage. He also comments that a dummy of Holmes has been ‘used before’, referencing the events of EMPT.

The Three Gables - 1903?

Watson has not seen Holmes ‘in some days’.

The Creeping Man - September 1903

As originally published, the date is stated as September 1902, but when collected in Case-Book, this changes to 1903. I place it in 1903 as Watson is not living at Baker Street at this time, having been summoned by a note from Holmes.

The Lion’s Mane - July 1907

Holmes is retired

His Last Bow: The War Service Of Sherlock Holmes - August 1914

Holmes has been undercover for the past two years.

Additionally:

This chronology was started in direct opposition to and due to frustration with Baring-Gould's chronology. Any comments or suggestions based on it will be disregarded.

It is my aim with this chronology to take into account all stated dates, and take them as correct except for where they blatantly contradict others. (e.g. SIGN being dated to either July or September 1888, when FIVE references Watson's wife in September 1887 and SCAN refers to his marriage in March 1888; Wisteria Lodge being dated to March 1892 when Holmes is 'dead' at this time)

It is also my intention that Watson is only married twice, the first time to Mary Morstan in late 1887 and the second to an unknown Mrs Watson in early 1903 (being strictly canonical, my own headcanons of him retiring to Sussex with Holmes aside)

I estimate that Holmes was born January 6th 1857, making him 18 at the time of GLOR and 24 at the time of STUD. Also by this estimate he would be 57 at the time of His Last Bow.

I estimate that Watson was born 23rd May 1853, making him 27 at the time of STUD. This would make him 61 at the time of His Last Bow.

#sherlock holmes#acd canon#acd holmes#i reject your chronology and substitute my own#watson's birthday is pure headcanon#i just thought it would be fun for it to be the day after acd's#i have not got my maths wrong for his age in study by the way - he just hasn't had his birthday yet

95 notes

·

View notes

Note

Has there ever been a time when we haven't had a vice president?

John Adams was sworn in as our first Vice President in 1789 and in the 234 years since then, we've gone without a VP for 37 years and 290 days.

Until the ratification of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment, there was no mechanism for filling a vacancy in the Vice Presidency, so in several instances we've gone almost entire Presidential terms without a Vice President.

7 Vice Presidents Died In Office: •George Clinton (Jefferson's second VP & Madison's first VP), died April 20, 1812, leaving the Vice Presidency vacant for 318 days. •Elbridge Gerry (Madison's second VP), died November 23, 1814, leaving a vacancy for 2 years, 101 days. •William Rufus DeVane King (Pierce's VP), died April 18, 1853, leaving a vacancy for 3 years, 320 days. •Henry Wilson (Grant's second VP), died November 22, 1875, leaving a vacancy for 1 year, 102 days. •Thomas A. Hendricks (Cleveland's first VP), died November 24, 1885, leaving a vacancy for 3 years, 99 days. •Garret A. Hobart (McKinley's first VP), died November 21, 1899, leaving a vacancy for 1 year, 103 days. •James S. Sherman (Taft's VP), died October 30, 1912, leaving a vacancy for 125 days.

2 Vice Presidents Resigned: •John C. Calhoun (VP under John Quincy Adams and Jackson's first VP), resigned on December 28, 1832, leaving a vacancy for 66 days. •Spiro Agnew (Nixon's first VP), resigned on October 10, 1973, leaving a vacancy for 57 days.

9 Vice Presidents Succeeded to the Presidency: •John Tyler (William Henry Harrison's VP), assumed office upon President Harrison's death on April 4, 1841, leaving a VP vacancy for 3 years, 333 days. •Millard Fillmore (Taylor's VP), assumed office upon President Taylor's death on July 9, 1850, leaving a VP vacancy for 2 years, 238 days. •Andrew Johnson (Lincoln's second VP), assumed office upon President Lincoln's death on April 15, 1865, leaving a VP vacancy for 3 years, 323 days. •Chester Arthur (Garfield's VP), assumed office upon President Garfield's death on September 19, 1881, leaving a VP vacancy for 3 years, 166 days. •Theodore Roosevelt (McKinley's second VP), assumed office upon President McKinley's death on September 14, 1901, leaving a VP vacancy for 3 years, 171 days. •Calvin Coolidge (Harding's VP), assumed office upon President Harding's death on August 2, 1923, leaving a VP vacancy for 1 year, 214 days. •Harry S. Truman (FDR's third VP), assumed office upon President Roosevelt's death on April 12, 1945, leaving a VP vacancy for 3 years, 283 days. •Lyndon B. Johnson (JFK's VP), assumed office upon President Kennedy's death on November 22, 1963, leaving a VP vacancy for 1 year, 59 days. •Gerald Ford (Nixon's second VP), assumed office upon President Nixon's resignation on August 9, 1974, leaving a VP vacancy for 132 days.

Only two Vice Presidential vacancies have been filled under the provisions of the 25th Amendment. Gerald Ford was appointed to the Vice Presidency by President Nixon following Spiro Agnew's resignation in October 1973 and was confirmed by Congress in December 1973 (a nominee to fill a Vice Presidential vacancy must be confirmed separately by a majority vote of both chambers of Congress). On August 9, 1974, Nixon resigned as President and Ford succeeded to the White House, leaving the Vice Presidency vacant for the second time in less than a year. President Ford nominated Nelson Rockefeller as Vice President on August 20 and he was confirmed by Congress in December 1974.

#History#Vice Presidency#Vice President of the United States#Vice Presidents#Vice Presidential Vacancies#Constitution#Twenty-Fifth Amendment#Vice Presidential nominees#VPs#VPOTUS#Vice Presidential History#Presidents#Presidency#Presidential History#Presidential Succession

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

what are some underrated boats that you dont think get enough love or appreciation and why?

sincerely,

#1 sailboat fan ⛵

For me, I'd say White Star Lines SS Germanic. She was 455 feet long and 5,008 Gross Registered Tons. She was delivered to the White Star Line in 1875 as the sister of the SS Britannic. These ships were largely considered to be a scaled up version of the Oceanic class from 1870, but her career is what makes her interesting to me. She had 1 propeller powered by compound steam engines, and a service speed of 16 knots (30 km/h, or 18 mph). At this speed, she and her sister won back the Blue Ribband for the White Star Line. Like the Oceanic class, she was rigged as a barque with sails in case of emergency, which came in handy when in January of 1883 her propeller shaft sheared at sea, and she had to make the rest of the journey by sail. She was the last White Star liner to be constructed primarily out of iron. After her, all of their ships were made from steel. In April of 1885, she encountered a rogue wave, which struck her and caused substantial damage. Six lifeboats had been torn away, the skylights to her engine rooms were smashed, and her pilot house was crushed. Water flooded into the boiler and engine rooms, a hole was torn into the side of the reading room, which quickly flooded (followed by the saloon and staterooms), and 13 people were injured, with one sailor being washed overboard. On 13th of February 1899, she was caught in a massive blizzard at her pier in New York. An estimated 1,800 Tons of snow and ice fell atop her superstructure. This added weight was enough to make her list enough that water could enter her open Coaling ports. She sank at her pier. She was refloated, repaired, and resumed service three months later. Starting around 1904, she changed hands numerous times, until finally landing in the Ottoman empire, and being renamed Gul Djemal / Gülcemal. She served as a troop transport until 1920, when she became a passenger ship again. She was retired from service in 1937, but wasn't scrapped until 1950. There were plans to convert her into a floating hotel (like the Queen Mary would be in 1970) but this never came to fruition. Having been in service for 75 years, she is the second longest serving ocean liner, behind Cunard Line's SS Parthia. She survived both World Wars (even though she played no part in the second World War). Her sister ship Britannic was scrapped in 1904, after serving in the Second Boer War as a troop ship.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

The napoleonic marshal‘s children

After seeing @josefavomjaaga’s and @northernmariette’s marshal calendar, I wanted to do a similar thing for all the marshal��s children! So I did! I hope you like it. c: I listed them in more or less chronological order but categorised them in years (especially because we don‘t know all their birthdays). At the end of this post you are going to find remarks about some of the marshals because not every child is listed! ^^“ To the question about the sources: I mostly googled it and searched their dates in Wikipedia, ahaha. Nevertheless, I also found this website. However, I would be careful with it. We are talking about history and different sources can have different dates. I am always open for corrections. Just correct me in the comments if you find or know a trustful source which would show that one or some of the dates are incorrect. At the end of the day it is harmless fun and research. :) Pre 1790

François Étienne Kellermann (4 August 1770- 2 June 1835)

Marguerite Cécile Kellermann (15 March 1773 - 12 August 1850)

Ernestine Grouchy (1787–1866)

Mélanie Marie Josèphe de Pérignon (1788 - 1858)

Alphonse Grouchy (1789–1864)

Jean-Baptiste Sophie Pierre de Pérignon (1789- 14 January 1807)

Marie Françoise Germaine de Pérignon (1789 - 15 May 1844)

Angélique Catherine Jourdan (1789 or 1791 - 7 March 1879)

1790 - 1791

Marie-Louise Oudinot (1790–1832)

Marie-Anne Masséna (8 July 1790 - 1794)

Charles Oudinot (1791 - 1863)

Aimee-Clementine Grouchy (1791–1826)

Anne-Francoise Moncey (1791–1842)

1792 - 1793

Bon-Louis Moncey (1792–1817)

Victorine Perrin (1792–1822)

Anne-Charlotte Macdonald (1792–1870)

François Henri de Pérignon (23 February 1793 - 19 October 1841)

Jacques Prosper Masséna (25 June 1793 - 13 May 1821)

1794 - 1795

Victoire Thècle Masséna (28 September 1794 - 18 March 1857)

Adele-Elisabeth Macdonald (1794–1822)

Marguerite-Félécité Desprez (1795-1854); adopted by Sérurier

Nicolette Oudinot (1795–1865)

Charles Perrin (1795–15 March 1827)

1796 - 1997

Emilie Oudinot (1796–1805)

Victor Grouchy (1796–1864)

Napoleon-Victor Perrin (24 October 1796 - 2 December 1853)

Jeanne Madeleine Delphine Jourdan (1797-1839)

1799

François Victor Masséna (2 April 1799 - 16 April 1863)

Joseph François Oscar Bernadotte (4 July 1799 – 8 July 1859)

Auguste Oudinot (1799–1835)

Caroline de Pérignon (1799-1819)

Eugene Perrin (1799–1852)

1800

Nina Jourdan (1800-1833)

Caroline Mortier de Trevise (1800–1842)

1801

Achille Charles Louis Napoléon Murat (21 January 1801 - 15 April 1847)

Louis Napoléon Lannes (30 July 1801 – 19 July 1874)

Elise Oudinot (1801–1882)

1802

Marie Letizia Joséphine Annonciade Murat (26 April 1802 - 12 March 1859)

Alfred-Jean Lannes (11 July 1802 – 20 June 1861)

Napoléon Bessière (2 August 1802 - 21 July 1856)

Paul Davout (1802–1803)

Napoléon Soult (1802–1857)

1803

Marie-Agnès Irma de Pérignon (5 April 1803 - 16 December 1849)

Joseph Napoléon Ney (8 May 1803 – 25 July 1857)

Lucien Charles Joseph Napoléon Murat (16 May 1803 - 10 April 1878)

Jean-Ernest Lannes (20 July 1803 – 24 November 1882)

Alexandrine-Aimee Macdonald (1803–1869)

Sophie Malvina Joséphine Mortier de Trévise ( 1803 - ???)

1804

Napoléon Mortier de Trévise (6 August 1804 - 29 December 1869)

Michel Louis Félix Ney (24 August 1804 – 14 July 1854)

Gustave-Olivier Lannes (4 December 1804 – 25 August 1875)

Joséphine Davout (1804–1805)

Hortense Soult (1804–1862)

Octavie de Pérignon (1804-1847)

1805

Louise Julie Caroline Murat (21 March 1805 - 1 December 1889)

Antoinette Joséphine Davout (1805 – 19 August 1821)

Stephanie-Josephine Perrin (1805–1832)

1806

Josephine-Louise Lannes (4 March 1806 – 8 November 1889)

Eugène Michel Ney (12 July 1806 – 25 October 1845)

Edouard Moriter de Trévise (1806–1815)

Léopold de Pérignon (1806-1862)

1807

Adèle Napoleone Davout (June 1807 – 21 January 1885)

Jeanne-Francoise Moncey (1807–1853)

1808: Stephanie Oudinot (1808-1893) 1809: Napoleon Davout (1809–1810)

1810: Napoleon Alexander Berthier (11 September 1810 – 10 February 1887)

1811

Napoleon Louis Davout (6 January 1811 - 13 June 1853)

Louise-Honorine Suchet (1811 – 1885)

Louise Mortier de Trévise (1811–1831)

1812

Edgar Napoléon Henry Ney (12 April 1812 – 4 October 1882)

Caroline-Joséphine Berthier (22 August 1812 – 1905)

Jules Davout (December 1812 - 1813)

1813: Louis-Napoleon Suchet (23 May 1813- 22 July 1867/77)

1814: Eve-Stéphanie Mortier de Trévise (1814–1831) 1815

Marie Anne Berthier (February 1815 - 23 July 1878)

Adelaide Louise Davout (8 July 1815 – 6 October 1892)

Laurent François or Laurent-Camille Saint-Cyr (I found two almost similar names with the same date so) (30 December 1815 – 30 January 1904)

1816: Louise Marie Oudinot (1816 - 1909)

1817

Caroline Oudinot (1817–1896)

Caroline Soult (1817–1817)

1819: Charles-Joseph Oudinot (1819–1858)

1820: Anne-Marie Suchet (1820 - 27 May 1835) 1822: Henri Oudinot ( 3 February 1822 – 29 July 1891) 1824: Louis Marie Macdonald (11 November 1824 - 6 April 1881.) 1830: Noemie Grouchy (1830–1843) —————— Children without clear birthdays:

Camille Jourdan (died in 1842)

Sophie Jourdan (died in 1820)

Additional remarks: - Marshal Berthier died 8.5 months before his last daughter‘s birth. - Marshal Oudinot had 11 children and the age difference between his first and last child is around 32 years. - The age difference between marshal Grouchy‘s first and last child is around 43 years. - Marshal Lefebvre had fourteen children (12 sons, 2 daughters) but I couldn‘t find anything kind of reliable about them so they are not listed above. I am aware that two sons of him were listed in the link above. Nevertheless, I was uncertain to name them in my list because I thought that his last living son died in the Russian campaign while the website writes about the possibility of another son dying in 1817. - Marshal Augerau had no children. - Marshal Brune had apparently adopted two daughters whose names are unknown. - Marshal Pérignon: I couldn‘t find anything about his daughters, Justine, Elisabeth and Adèle, except that they died in infancy. - Marshal Sérurier had no biological children but adopted Marguerite-Félécité Desprez in 1814. - Marshal Marmont had no children. - I found out that marshal Saint-Cyr married his first cousin, lol. - I didn‘t find anything about marshal Poniatowski having children. Apparently, he wasn‘t married either (thank you, @northernmariette for the correction of this fact! c:)

#Marshal‘s children calendar#literally every napoleonic marshal ahaha#napoleonic era#Napoleonic children#I am not putting all the children‘s names into the tags#Thank you no thank you! :)#YES I posted it without double checking every child so don‘t be surprised when I have to correct some stuff 😭#napoleon's marshals#napoleonic

77 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Governor of New York David B. Hill signed legislation creating the Niagara Reservation, New York’s first state park on April 30, 1885, ensuring that Niagara Falls will not be devoted solely to industrial and commercial use.

#David B. Hill#Niagara Reservation#Niagara Falls#Niagara River#New York#Ontario#Canada#Horseshoe Falls#American Falls#tourist attraction#USA#Bridal Veil Falls#original photography#nature#landscape#cityscape#landmark#detail#ship#30 April 1885#anniversary#US history#travel#vacation#summer 2018#US-Canada border

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 215 Trivia

I expected a rocket this chapter, but I didn't expect this many of them…

This is a Newtonian telescope based on the secondary mirror and spider supports. Here, these supports are entirely pointless since it seems to be embedded into glass anyways. The glass could mean it's a Schmidt-Newtonian telescope instead, but the design is still redundant.

The design here is a very generic "spy satellite", similar to how the Hubble Space Telescope looks. I don't think it matches any specific satellite.

If you want to know more about orbits, I highly recommend reading the Dr. Stone Reboot: Byakuya if you haven't already!

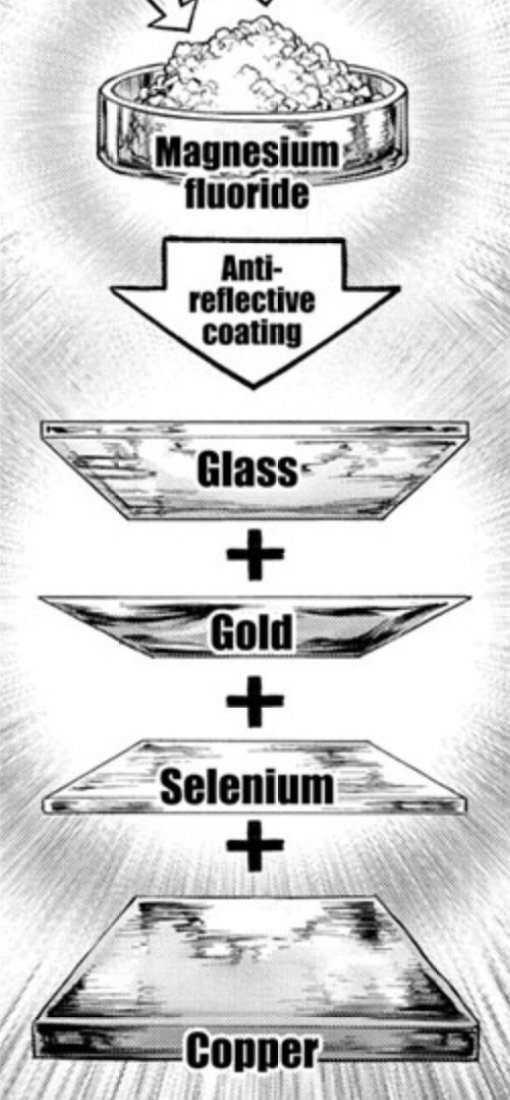

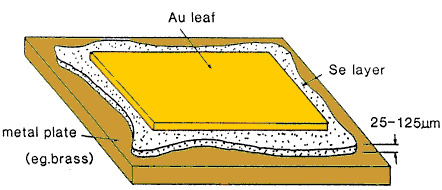

The first photovoltaic cells were layered brass/gold/selenium, created by Charles Fritts in 1885. Senku upgraded his with a layer of glass coated in magnesium fluoride, which prevents the sunlight "escaping", thus converting more of it to electricity. They're about 1% efficient.

The black cat post here is a reference to Yamato Transport, one of Japan's largest door-to-door delivery services. Their logo is a black cat holding a kitten, symbolizing that they take care of your items as if it were family.

The time between the first "level 1" rocket and the completed "level 99" rocket was 3 years according to Senku, meaning the first rocket test in this chapter was around April 5753.

For some reason this sound effect is in English. I guess it really needed that "M" sound at the end?

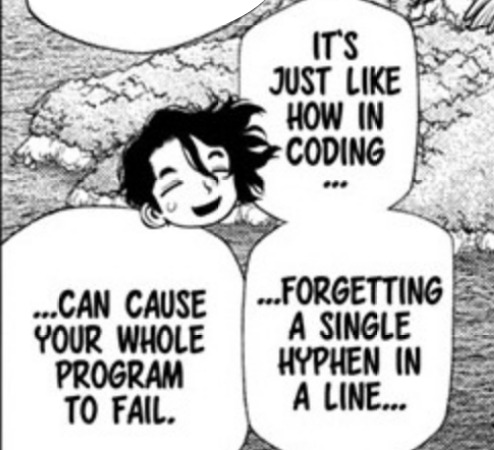

Sai mentions missing a hyphen in a line, however machine code tends to not use hyphens at all. That said, if we remember the trivia from chapter 204 then we know that the Mariner 1 was destroyed because of a missing hyphen, and the Mars Climate Orbiter was destroyed on landing because of a failure to convert units.

For the Mariner 1 specifically, the issue was a missing hyphen in the guidance program (redundant system). NASA called it the "devil's hyphen" and used it as a warning to focus on software.

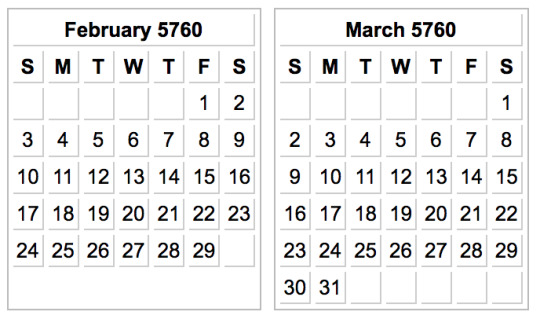

The calendar here is more helpful than you'd think: the arrangement of visible dates here is somewhat rare, happening only once every 28 years. The last confirmed year we had is 5750, making this…

…March, 5760.

The chapter isn't even over yet…

(Yes this means Senku is around 30 years old when they launch the second rocket, since he turned 20 in 5750.)*

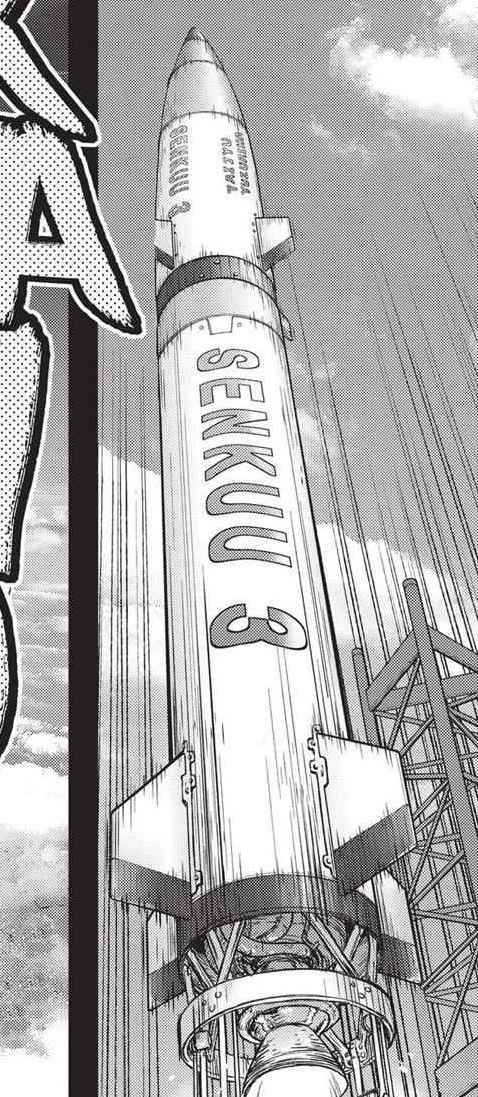

The Senku 3 rocket is similar to the one he made as a teenager, but looks a lot less refined thanks to stone world craftsmanship. After two failures, their name writing seems to have gotten lazier…

Most of the rocket problems are self explanatory, but the bubble one is a little less logical: it forms in the fuel tank, and when it pops, it creates a pressure wave that can erode metal from the fuel pump. Obviously having tiny pieces of metal in your fuel is a bad thing…

I don't know how this crowd isn't scared of how close they are to all these explosions and out-of-control rockets!?

This doesn't look right…

…Do Xeno and Senku not notice that Chrome and Suika seem to be watching them from the roof…? I guess there's no better way of learning if you're trying to be sneaky about it!

(*This ended up being unintentional on Inagaki's part, and he brought up a correction here.)

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Canonical Five: Mary Jane Kelly

April 02, 2023

Mary Jane Kelly is who is known as Jack the Ripper’s 5th and final canonical five victim, however, there is much less information known about her upbringing compared to the other four women.

It is believed by many that the information we do know about Mary Kelly is embellished, with her having fabricated details that are known about her early life.

The man Mary Kelly had most recently been living with before her murder was named Joseph Barnett, and he later claimed Mary had told him she was born in Limerick, Ireland around 1863 and her family had moved to Wales when she was a child.

Supposedly Mary Kelly had told an acquaintance that she had been disowned by her parents, but she was close with her sister. It was said from Joseph and Mary’s landlady that she had come from a somewhat wealthy, good family. Joseph also claimed Mary confirmed she had seven brothers and at least one sister.

Mary’s landlord, a man named John McCarthy claimed she had received mail from Ireland, but not regularly. It was also believed that Mary was illiterate, as Joseph claimed she would ask him to read her the newspaper reports of the Jack the Ripper killings.

Though it’s been reported Mary had blonde or red hair, she went by the nickname of “Black Mary” suggesting she actually had quite dark hair. She also had blue eyes and some claimed to have known her as “Fair Emma.” It is estimated that Mary stood at about 5′7″ tall, and some said she was quite attractive.

On November 10, 1888, the day after her murder,

the Daily Telegraph

described Mary as “tall, slim, fair of fresh complexion, and of attractive appearance.”

In 1879, at around the age of 16, Mary married a coal miner named Davis or Davies who ended up getting killed 2-3 years later in a mining explosion. After this, Mary lived with a cousin in Cardiff, and this is where it is believed she started being involved in sex work.

In 1884, Mary left Cardiff and moved to London, where she worked as a domestic servant while lodging in Crispin Street, Spitalfields. In 1885, it’s believed she moved to the district of Fitzrovia.

Mary eventually began working in a high class brothel in the West End of London, becoming one of the most popular girls. She did quite well for herself and bought expensive clothes and hired a carriage at this time. Supposedly Mary had met a client named Francis Craig who took her to France, but she returned to London two weeks later, not having liked the France life.

It is believed that in 1885 Mary Kelly began drinking heavily. She moved around quite a bit lodging with different women and different men around this time.

It was on April 8, 1887, that Mary Kelly met Joseph Barnett, with the pair agreeing to live with each other after only knowing one another for a day. They lived in George Street, and soon a place called Little Paternoster Row, but were evicted for not paying rent and of drunk and disorderly conduct.

In early 1888, the two moved into 13 Miller’s Court, a single room a the back of 26 Dorset Street, Spitalfields. Mary had lost her key to the door, so she would bolt and unbolt the door from outside, putting her hand through a broken window by the door. A neighbour claimed Mary had broken the window when she was drunk, and a man’s coat often was used to act as a curtain.

It was said by Mary’s friend Lizzie Albrook, that Mary was sick of how she was living in 1888 and wanted to go back to Ireland. Her landlord said that she was a quiet woman when she was sober but very noisy when drunk. When Mary was drunk she often could be abusive to people, and was nicknamed “Dark Mary.”

Joseph lost his job as a fish porter in July 1888 due to committing theft, and because of this, Mary turned back to sex work. Mary would often let other sex workers sleep in their room at night when it was really cold because she did not have it in her to refuse them shelter.

It is believed that on October 30, 1888, Joseph moved out as him and Mary got into a fight about a sex worker named Julia sharing their room with them. Between November 1 and November 8, Joseph visited Mary almost everyday, sometimes giving her money.

The last time Joseph visited Mary was between 7-8 pm on November 8, 1888. Joseph claimed Mary was with her friend, Maria Harvey and that he did not stay long. He also apologized to Mary for not having any money to give. It is reported that both Joseph and Maria left Miller’s Court at the same time.

Joseph went back to his lodging house and played cards, falling asleep around 12:30 am. Before Joseph left Mary that night, her friend Lizzie Albrook also visited. Lizzie claimed Mary was sober.

In the evening, Mary reportedly had one drink in the Ten Bells public house with a woman named Elizabeth Foster. Later on, Mary was seen drinking with two other people at the Horn of Plenty pub on Dorset Street.

A sex worker named Mary Ann Cox, who also was a resident of Miller’s Court claimed to have seen Mary going home drunk with a stout, ginger haired man, around the age of 36 at 11:45 pm. The man was wearing a black bowler felt hat, had a thick moustache, had blotches on his face and was holding a can of beer.

Mary Ann actually had spoken to Mary Kelly, they both said goodnight. Mary Kelly then entered the room with the man. Mary Ann heard her singing the song, “A Violet from Mother’s Grave.” She was still singing when Mary Ann left her place at midnight, and when she returned an hour later around 1 am.

Elizabeth Prater lived in the room directly above Mary Kelly. She reportedly went to bed at 1:30 am, and the singing had stopped.

A man named George Hutchinson who knew Mary, claimed he had met up with her around 2 am on November 9, 1888 on Flower and Dean Street. Mary had asked George for a loan of sixpence, though he claimed to be broke. George said Mary Kelly walked toward the direction Thrawl Street when she was approached by a man of “Jewish appearance.”

The man was looked to be about 34-35 years old and George said he was suspicious of him because while it did seem like Mary knew him, his appearance made him look suspicious in that particular part of town. It was also said that this man made an obvious effort to disguise his looks from George, having his hat covering over his eyes as he passed.

George provided police with a very detailed description of said man, and told them he had overheard Mary talking with the man, complaining she had lost her handkerchief, and the mysterious man gave her a red one that he had. George heard Mary say to the man, “Alright my dear, come along. You will be comfortable.” And then the two walked into 13 Miller’s Court with George following them, though George never saw either one of them again.

A laundress named Sarah Lewis also claimed she had been walking in the area to meet up with friends around 2:30 am, when she noticed two or three people standing near the Britannia pub, among the people was a nicely dressed young man with a dark moustache and he was talking to a woman.

Both the man and woman appeared to be drunk and there was a poorly dressed woman standing near them. Opposite from Miller’s Court, Sarah said she saw a stout looking shorter man standing at the entrance to the courtyard. Sarah also saw an obviously drunk woman with a man further up the courtyard.

Mary Ann returned to her room around 3 am that morning and claimed she did not hear or see any light coming from Mary Kelly’s room at the time. She did think she heard someone leaving at around 5:45 am.

Elizabeth Prater who lived in the room above Mary Kelly and Sarah Lewis who was sleeping at 2 Miller’s Court that night both reported hearing a faint cry that said “Murder!” between 3:30 and 4 am, but didn’t do anything about it because this was common to hear cries in the area. Sarah Lewis said it was only one scream so she did not think much of it. She also claimed she did not sleep that night and heard people coming and going out of the court throughout the night.

Elizabeth Prater said she left her room at 5:30 am to walk to the pub for a drink, but saw nothing out of the ordinary.

On the morning of November 9, 1888, Mary’s landlord sent his assistant to collect the rent. Mary herself was 6 weeks behind, owing 29 shillings. Shortly after 10:45 am, the assistant knocked on her door but got no response. He tried to then turn the handle, but the door was locked. He looked through the keyhole but did not see anyone in the room.

Using the broken window, he peered inside the room and found Mary Kelly, completely mutilated lying on the bed. She was estimated to have died 3-9 hours before she was discovered.

The assistant ran to tell the landlord, and then went to inform the police. The assistant immediately told the police it was the work of Jack the Ripper. A surgeon came to look at the body, and police gave orders to prevent anyone from entering or exiting the yard (I know, impressive for 1888 police work.)

Bloodhounds were sent in, but it appeared to be impractical. It appeared that women’s clothing had been burning, and authorities believed Mary Kelly’s clothes were burnt by the murderer to provide light so they could see what they were doing.

Joseph Barnett identified Mary Kelly’s body, he could only identify her by the ear and her eyes due to the severe mutilation.

The mutilation done to Mary Kelly was the most extensive of all of the Whitechapel murders, with many believing it’s due to the fact that the Ripper had more time to commit this one in a private setting.

During the autopsy it was noted that it most likely took 2 hours to perform all of the mutilations on Mary’s body, the death was further estimated to have occurred between 2 to 8 am.

Her body was found lying naked in the bed, her head turned on the left cheek. Her legs were left wide apart, the whole surface of the abdomen and thighs were removed and her abdominal cavity was emptied (but later said there was food found in it). Her breasts were cut off, her face was hacked beyond recognition, gashes occurring in all directions. Her ears were partly removed.

Her neck was cut through the skin and her other tissues were cut down to the vertebrae. Her air passage was cut at the lower part of the larynx. Her heart was taken. There was also blood splatters on the wall, lining up with her cut throat.

She had a superficial cut on her thumb, which some believe was caused while she tried to defend herself from her attacker.

It was believed during the autopsy that Mary Kelly had been killed from a slash to her throat, and the mutilations were performed after she had died. It was not believed that the murderer had any medical knowledge.

The inquest into Mary’s death began on November 12, 1888. After testimony, the jury had a short deliberation and the verdict was that Mary Kelly had been murdered by a person or persons unknown.

Police did house to house questioning trying to get answers as to who murdered Mary Kelly. A few people claimed to have seen Mary on the morning of November 9, after she had supposedly been murdered, though police could not find anyone to corroborate those sightings, as well as the descriptions of Mary didn’t match.

On November 10, 1888, Mary’s murder was linked to four other murders: Mary Ann Nicholas, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, and Catherine Eddowes. There was also an offender profile made, which stated the killer was an eccentric person, who was in an extreme state of satyriasis while performing the mutilations on Mary and the four previous victims.

There were no other similar murders after Mary Kelly’s and a lot of people believe she was the final victim of Jack the Ripper. Most believe these Whitechapel murders ended due to the killer dying or going to prison.

Over 100 years after the Whitechapel murders, two authors named Paul Harrison and Bruce Paley theorized that Joseph Barnett, Mary’s partner, had actually murdered her during a jealous rage. They took the theory farther, stating that perhaps Joseph also murdered the other 4 canonical five, trying to scare Mary from engaging in sex work.

Others believe Joseph did kill Mary, but only Mary and had tried to make it look like a Jack the Ripper killing to avoid being captured. The fact that Mary was found lying naked on her bed, with her clothes folded on a chair leads many to believe that her killer was someone she knew or who she thought was a client.

Some people do not believe Mary Kelly was a victim of Jack the Ripper at all. Mary was assumed to be around 25 years old, much younger than the other victims who had all been in their 40′s. Also, her mutilations were more extensive than the other four, she was killed in a private location and her murder occurred 5 weeks from the previous killings which had all occurred within a month.

In 1939, author William Stewart theorized that Mary might have been killed by a midwife, “Jill the Ripper” in which Mary was going to have an abortion. Stewart believed perhaps the midwife had burned her own clothes, putting on Mary’s and that’s why people the next morning believed they saw Mary after she had been killed.

Mary Kelly was buried on November 19, 1888 in St Patrick’s Roman Catholic Cemetery in Leytonstone. None of her family members could be found to attend her funeral. The inscription on her grave reads, “In loving memory of Marie Jeanette Kelly. None but the lonely hearts can know my sadness. Love lives forever.”

#unsolved#UNSOLVED MYSTERIES#unsolved crime#unsolved murder#unsolved case#murder#jack the ripper#london#canonical#five#last#victim#whitechapel#murders

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Possible Dates of Birth and Death for the Ashford Family

@geralddurden Part 1 of your request. For some historical context, I’ve calculated the possible birth and death dates of the Ashford family. The calculation does not directly fit your question, and I don’t want the post to become too long. That’s why I post it separately.

First, the official facts:

Alfred and Alexia were born in January(?)* 1971 and died in December 1998

Alexander turned into Nosferatu in March/April 1983 and died in December 1998

Edward died in July 1968

Veronica and Stanley lived in the 19th century

The head of the family stays in this position until death

The new head of the family receives a present from the butler, and a painting is drawn a while later

Alfred was head of the Ashford family from 1983 till 1998

Alexander was head of the Ashford family from 1968 till 1983

*I’m sure I read somewhere that Alfred and Alexia were born in late January, but I can’t find the source anymore. Now I’m unsure if this was official or from fan content. I still leave it here in case it was official.

Some general assumptions I used for the calculation:

Since Alfred is still a child in his painting, they were probably drawn shortly after (+1 year at max) the respective family member became the new head of the Ashford family. Therefore, the paintings equal roughly the date of death of the previous one.

Considering their status, all family members except for Alexander were married when their children were born and probably 20 or older.

Alexander: Alexander worked with his father before his father died. Therefore, he already graduated from a university. Also, in his video message in DC, Alexander looked still quite young. It is unlikely that he was younger than 25 in 1968, but he could not have been much older than 30 either. This places his date of birth between 1938 and 1943. So in 1983, when he turned into Nosferatu, Alexander was between 40 and 45.

Edward: In his painting, he is already an older man. I would estimate he was in his late 40s or early 50s (48-52). Also, I think he is somewhat of a similar age to Spencer and Marcus. Spencer was born in 1923, and Marcus in 1918. Edward is probably the oldest one of them, but not too much older. Therefore, he was presumably born between 1910 and 1915 and 53 to 58 when he died.

From here on, things become less clear and depend heavily on your interpretation. We know Arthur and Thomas were born around or before 1890 to 1895. You can use these years as a reference point, but I prefer another calculation. Let’s skip Arthur and Thomas for now and go to Stanley. But first, let me estimate how old these three are in the paintings. Thomas appears to be rather young. I'd say he was in his early 20s (20-25). Stanley looks older than his son, maybe 30-35. Arthur definitely appears to be the oldest, but his hair is still red and not graying (much?). He could be 35 to 40, 45 at max, but I will use 35-40.

Stanley: We know Stanley lived in the 19th century. If the years 1890 to 1895 were used as a date of birth for his children, a larger portion of his life would extend into the 20th century. That’s why I think it is more likely that he died around 1900. It can’t be too much before 1900 either since this would cause other problems. Let’s say he died between 1900 and 1905. Considering his and Thomas's age in the painting, he probably became head of the family between 1875 and 1885, which equals the birth of his children, and he was born between 1840 and 1855. Also, Stanley must have been at least 50 when he died.

Thomas and Arthur: So Stanley’s children were born between 1875 and 1885. Arthur became head of the family after the death of his brother. Therefore, Thomas died at the age of 35 to 40 between 1910 and 1925. As I’ve mentioned above, Edward appears to be in his late 40s or early 50s in the painting. This means Arthur presumably died between 1958 and 1963.

Veronica: We already have Veronica’s date of death: between 1875 and 1885. But when was she born? In the painting, she looks young, maybe in her mid-20s. I assume she married and became a mother after she got her title. Stanley was probably born quite late, when Veronica was between 30 and 35. This places her date of birth between 1805 and 1825. Also, she was at least 60 when she died.

I hope this wasn’t too confusing. Now here’s a summary of the final results:

Minimum estimation/Maximum estimation [Time as the head of the Ashford family] official and unofficial estimated dates

Alexia: January 1971 – December 1998 Age: 27 Alfred: January 1971 – December 1998 [1983 – 1998] Age: 27 Alexander: 1938/1943 – (March/April 1983)** or December 1998 [1968 – 1983] Age: 40/45** or 55/60 Edward: 1910/1915 – July 1968 [1958/63 – 1968] Age: 53/58 Arthur: 1875/1885 – 1958/63 [1910/1925 – 1958/63] Age: 73/88 Thomas: 1875/1885 – 1910/1925 [1900/1905 – 1910/1925] Age: 35/40 Stanley: 1840/1855 – 1900/1905 [1875/1885 – 1900/1905] Age: 50/65 Veronica: 1805/1825 – 1875/1885 [1830/1850 – 1875/1885] Age: 60/80

** Depending on whether you still count Nosferatu as Alexander or whether you say he is just an empty shell.

#resident evil#alexander ashford#alfred ashford#alexia ashford#edward ashford#veronica ashford#ashford twins#meta#🩸🌙#arthur ashford

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rudolf Klein-Rogge, November 24, 1885 - April 30, 1955.

Fritz Lang’s The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933).

10 notes

·

View notes