#1920s medicine

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I've been on one of my regular excursions down a JSTOR rabbit hole lately, mostly researching 1920s psychiatric medicine for a character. Sometimes when you're reading a bunch of papers about a narrow topic, you'll find yourself encountering specific names more than once.

In this case, it's Sir Maurice Craig.

I first encountered this guy when I read a bunch of letters back and forth to the British Medical Journal. It starts with Maurice writing in saying "Barbiturates are totally not addictive, I give them to all my patients with no problems."

Now you might be tempted to say "Oh well they probably all thought that back then, they didn't know better."

Nope! There follows a flurry of responses from other doctors saying “Uhhh, I don't think so mate.” One of them sarcastically points out that if Sir Craig has never tried reducing his patients’ doses, he might not have realised they were addicted.

This is met by response after response from Maurice telling them they were wrong.

I then later spot his name mentioned in a conference on treating insomnia, where he said “Look guys, even if barbiturates are addictive, insomnia is way worse.”

And then today, I find him again, speaking at a meeting of (wait for it) the National Temperance League.

Maurice: “Alcohol is bad cause it's addictive.”

Uh huh, yes that tracks.

Maurice: “Which is why everyone should take barbiturates instead!”

Okay Maurice, you lost me there.

And just to confirm that this was very much not the universal medical opinion at the time, there's another doctor at the same meeting who's recorded as saying pretty much that.

I can't tell if he was just really stubborn or getting some kind of kickback from the drugs manufacturers,but either way wherever he went Sir Maurice Craig was saying “THESE DRUGS ARE AWESOME”, followed by a small crowd of his peers doing their best to correct him.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spinal adjustment and mechanical treatment. 1922.

Internet Archive

509 notes

·

View notes

Text

antique bottles

#vintage#mine#antique#dark academia#academia#poison#light academia#jars#bottles#potions#indie#grunge#pale#pale blog#aesthetic#soft grunge#circa 1910#1920s#medicine#collectibles

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Electrotherapy department, Pázmány Péter Catholic University Clinic, Budapest, 1922. From the Budapest Municipal Photography Company archive.

91 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Source details and larger version.

Like a drug: my collection of vintage medicine can be habit forming.

#snake oil#medicine#silhouette#bear#1920s#vintage yearbook#vintage illustration#yearbook#illustration

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

eye holder for surgical education, surgical instruments and a glass eye, 1920

#old medicine#surgery#vintage medical#antique medical#medical models#anatomical#medical antiques#1920s#mine

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here's some medicines from around the Titanic time period in case anyone is as interested as I was 💝

#sicknario#sickfic prompts#sickfic#emeto prompt#titanic#cold medicine#medicine#1910s#1920s#tummy medicine#i love this

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m running on 1 Pellet Per Mile of Poop

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

It started with me trying to figure out roughly how much HAIR is exactly on Hackles in his human form and it turned into a joke about how his partner is MADE of the substance that they make condoms out of.

-

Slimes historically are made from a base of a laytex like substance which gives them their stretchy, rubbery, solid form, without it-they'd just be liquids.

#TSB Draws#Induction#New Chicago#Hackles#Peartree#Comic#Medical#Medicine#fun fact laytex condoms were invented in the 1920s#laytex is also a naturally occuring subtance in nature#it's a type of rubber made from rubber trees

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forfar Herald (Angus, Scotland) - Friday 12 September 1924

Source: British Newspaper Archive

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Source details and larger version.

They've had many lives and many ages: cats I've met in my time travels.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Medical educators recognized that the decision to study medicine had something to do with personal characteristics, cultural values, and the perceived attractiveness of medicine as a career, though no one could precisely explain medicine's growing popularity as a career or how premedical students might have differed from undergraduates who pursued other fields. Nevertheless, this was of little worry to medical schools, which now rejoiced at being able to conduct medical education on a far higher plane. Students entered medical school already knowing the alphabet of science, which allowed the four years of medical school to be preserved for purely medical subjects. Academic failure became much less common. By the 1930s the national attrition rate had fallen to 15%, most of which occurred during the first year of study. At elite schools that were highly competitive for admission, attrition rates were much lower still.

What course of study should students preparing for medicine undertake? This troublesome issue perplexed medical school and university officials alike. Everyone agreed that in an era of scientific medicine, a college education alone did not suffice. Rather, specific courses were required so that students could begin medical study without having to take remedial work. These consisted of biology or zoology, inorganic chemistry, organic chemistry, and physics. Most medical schools required or recommended courses in English, mathematics, and a foreign language as well.

Beyond these requirements, there was great confusion concerning the best preparation for medical school. Officially, medical school officials espoused the importance of a broad general education, not a narrow scientific training. However, faculties frequently sent the opposite message. This dilemma was illustrated at the University of Michigan. The medical school dean met repeatedly with premedical students to tell them “that the purpose of their preparation was to give them a broad general education.” Yet, the majority of individual faculty at the school believed that “science courses are still paramount for medical students.” James B. Conant, A. Lawrence Lowell's successor as president of Harvard University, summarized the dilemma in 1939: “I realize that many deans, professors, and members of the medical profession protest that what they all desire is a man with a liberal education, not a man with four years preloaded with premedical sciences. The trouble is very few people believe this group of distinguished witnesses. Least of all the students.” Accordingly, the overwhelming majority of applicants applied to medical school having majored in a scientific subject.

Though medical schools sought qualified students, most were not eager to increase the number admitted. Medical deans knew precisely how many students the school's dissection facilities, student laboratories and hospital ward could accommodate. The situation at the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University was typical. In 1918, to ensure that all students “can be adequately taught and trained” the school reduced the size of the first-year class by one-half. The faculty found this experience “infinitely more satisfactory” than trying to teach larger numbers of students as before. In emphasizing education quality, medical schools were thought to be acting in a socially responsible fashion. Virtually no one in the 1920s or 1930s, inside or outside the profession, thought the country was suffering from too few physicians.

Medical educators and admissions officers debated endlessly how to select the finest candidates from the growing applicant pool: whether to rely on grades, courses taken, letter of recommendation, or the personal interview. Virtually all admissions committees valued that elusive quality of “character,” though no one knew exactly how to define or measure it. To help makes their deliberations more “scientific,” some admissions committees began using the results of the Medical Aptitude Test, a standardized objective test introduced by medical educators and educational psychologists at George Washington University in the late 1920s and recommended for general use by the Association of American Medical Colleges in 1931. However, no instrument of measurement, alone or in conjunction with others, could allow them to determine with confidence which applicants would make the best practitioners or medical scientists. The Medical Aptitude Test could accurately predict which students would achieve academic success during the formal course work of medical school, but not future success at practicing medicine.'

– Time to Heal: American Medical Education from the Turn of the Century to the Era of Managed Care by Kenneth M. Ludmerer

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

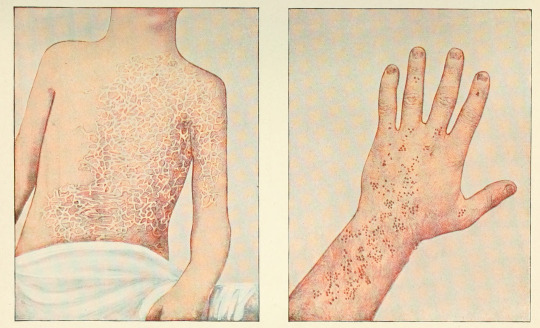

Eczema. Library of health. 1921.

Internet Archive

193 notes

·

View notes

Note

NAHH IMAGINE THE HISTORY GCSES (or hallownest equivalent of it) - 👹

Honestly if my history GCSE content was THAT interesting I'd probably have had a shit ton of fun

#we did 1920s America for some reason instead:((#im still salty about that it was SO BORINH#asks#rfds bad end#we did do ancient medicine tho and that was interesting

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The first ambulance serving the city of Pécs, 1927. From the Budapest Municipal Photography Company archive.

49 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Source details and larger version.

Vintage Native American art.

19 notes

·

View notes