#14 July 1789

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

For the average person, all problems date to World War II; for the more informed, to World War I; for the genuine historian, to the French Revolution.

Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn

#Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn#kuehnelt-leddihn#quote#french revolution#14 july 1789#bastille day#history#french history#world history#civilisation#western history#politics#historian#ideology#revolution#europe

302 notes

·

View notes

Text

14 Julliet 1789

Révolution dans les rues

Je vois le chaos en dessous

La justice est une rivière rouge

Je te cherche, où es-tu?

#assassin's creed#assassin's creed unity#arno dorian#ac unity#arno victor dorian#french revolution#14 july 1789#ubisoft games#ubisoft quebec#miracle of sound#Assassin's creed 4#elise de la serre#Arno x elise

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fête de la Fédération

Fete de la Federation was a massive festival celebrated on July 14, honoring the French Revolution. The day was the predecessor of Bastille Day, as celebrated today. The point of the festival was to celebrate both the Revolution and the spirit of National Unity. At the time, the Revolution had overthrown the excesses of the French monarchy and replaced it with a constitutional monarchy, led by an elected National assembly. The Fete de la Federation was organized to coincide with the first anniversary of the storming of the Bastille. The festival came at a time when people believed that the revolution was over, though turmoil would follow in the coming years.

History of Fete de la Federation

The French Revolution began in 1789 with that year’s Estates-General. The abolition of the reigning ‘Ancien Régime’ or Old Regime began on July 14, 1789, when a crowd of protesters stormed the Bastille prison. By 1790, the monarchy had been overthrown and a National Assembly was elected. Believing the Revolution to be over, a desire to celebrate national unity spread across the French people. The festival in Paris was to be the most prominent celebration of fraternity — it was to be attended by the royal family, the deputies of the National Assembly, and the general public. The event was organized on the Champ de Mars, which was outside Paris at the time.

The festival began with a feast as early as 4:00 A.M., and it continued to proceed despite downpours throughout the day. A parade of ‘federes’ organized under 83 banners marched their way to the place the Bastille once stood, and the members of the National Assembly, along with Louis XVI, all took an oath to protect the new Nation. The festival was also attended by delegates from countries across the globe. A popular feast followed the official celebration.

Unbeknownst to all those who attended the festivities, the stability that they foresaw was not what they had in store for them. The following years in France were of political turmoil that culminated in the people becoming disillusioned with the monarchy, leading to the execution of the royal family in 1973. Even with the French Republic finally established, peace did not follow. June 1973 saw an uprising that overthrew much of the National Assembly, sparking the Reign of Terror in the nation. The following year saw 16,000 at the hands of the Jacobins. To deal with the oppressive threat of the former, a fragile French Directory was formed, which was soon overthrown by Napoleon Bonaparte, marking the end of France’s revolutionary period.

Fete de la Federation timeline

June 13, 1789 Estates General of 1789

The Third Estate forms the National Assembly.

July 14, 1789 Storming of the Bastille

Revolutionaries storm the Bastille prison.

July 14, 1790 Fete de la Federation

The Fete de la Federation is organized to celebrate the French Revolution.

January 1793 Monarch beheaded

Louis XVI is beheaded.

Fete de la Federation FAQs

What is July 14 in France?

It is celebrated as Bastille Day.

When was the French Revolution?

May 5, 1789, to November 9, 1799.

What is the name of the flag of France?

It is called the ‘Tricolore.’

How to Observe Fete de la Federation

Read about the French Revolution

Watch a documentary

Look up related philosophy

The French Revolution was a turning point in history. Spend the day reading about it.

If reading isn’t your thing, pop in a documentary about the Revolution! You’re bound to find something entertaining. You can even try a movie or two, like “Les Miserables” or “Marie Antoinette.”

The French Revolution was built on a foundation of ideas like equality, liberty, and justice. Learn more about these abstractions and what philosophers have said about them.

5 Interesting Facts About France

Tourism

National motto

Inventions

Highest European mountain

Most visited museum

France is the world’s most popular tourist destination.

The national motto of France is “Liberté, égalité, fraternité” or “liberty, equality, fraternity.”

The French invented the hot air balloon!

The tallest mountain in Europe, Mont Blanc, is in France.

The Louvre is the world’s most visited museum.

Why Fete de la Federation is Important

It’s an important part of French history

It’s a reminder of humanity

It’s an opportunity to learn about the French Revolution

The French Revolution formed the basis of the modern state of France. Fete de la Federation is an important part of it.

The French Revolution often entailed sequences of violent events. An earnest celebration of what people thought would be a peaceful regime reminds us of how human everyone in history was.

The Revolution is a major part of world history. The Fete de la Federation is a perfect excuse to learn more about it.

Source

#travel#original photography#vacation#tourist attraction#landmark#cityscape#architecture#landscape#14 July 1789#anniversary#French history#French National Celebration#France#summer 2021#Fête de la Fédération#Cruseilles#Saint-Nazaire-en-Royans#Isère#French Alps#Triumphal Arch of Orange#Fitou#Camaret-sur-Aigues#Pont du Gard#French National Day#Bastille Day

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

🇫🇷🎇 [Special History] July 14: “Nothing”

King Louis XVI wrote “nothing” in his journal on July 14, 1789. This fact is quite popular but often misunderstood. The king wrote “nothing” when he had not been hunting that day.

🇫🇷🎇 [Spécial Histoire] 14 Juillet : “Rien”

Le roi Louis XVI avait noté “rien” dans son journal à la date du 14 juillet 1789. Ce fait est assez populaire mais souvent mal compris. Le roi notait “rien” lorsqu'il n’avait pas pratiqué la chasse ce jour-là.

#14 juillet#july 14#history#histoire#education#éducation#learning#apprendre#national holiday#fête nationale#french revolution#révolution française#revolution#révolution#bastille day#jour de la bastille#bastille#culture#fête#festival#fête de la fédération#1789#1790#french#français#english#anglais#fraternité#liberté#freedom

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's an important day here in france , so I wish you all a wonderful holiday and/or day if you don't celebrate it 😌

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Storming of the Bastille, 14 July 1789, unknown French artist, before 1794

#Bastille Day#France#French Revolution#art#art history#history painting#French art#18th century art#Musée Carnavalet

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

My View On The French Revolution:

Rating: 7.5/10 Based

(But with some VERY cringe moments…)

Based Elements (Why It’s a W)

"Liberty, Equality, Fraternity": The OG slogan that inspired democracies worldwide. Pure Enlightenment rizz.

Abolishing Feudalism: Tearing up medieval privilege charts and declaring "tax the rich" energy.

Declaration of Rights of Man (1789): Literally wrote the blueprint for human rights.

Global Impact: Inspired Haiti’s revolution (first successful slave revolt) and scared monarchs everywhere.

Napoleonic Code: Turned "equality before the law" into a legal flex.

Peak Based Moment: Storming the Bastille (July 14, 1789) — the ultimate "eat the rich" vibe check.

Cringe Elements (Why It’s an L)

Reign of Terror (1793–94): Robespierre went full "chaotic good" and guillotined ~40k people, including his own allies. "Oops, I became the tyrant I swore to destroy."

De-Christianization Edgelords: Replacing Jesus with the Cult of Reason and renaming months to "Brumaire" or "Thermidor"? Tryhard atheist phase.

The Directory (1795–99): A corrupt government that made the Star Wars prequel Senate look competent.

Marie Antoinette Memes: "Let them eat cake" (probably fake) became the original viral dunk — but the monarchy’s disconnect was real.

Peak Cringe Moment: Louis XVI’s Flight to Varennes (1791). Bro tried to flee France in a fancy coach but got caught because someone recognized his face… from coins.

Neutral Chaos (It’s Complicated)

Napoleon’s Coup: Ended the Revolution by becoming Emperor. Sigma male grindset or betrayal of the republic? Yes.

Sans-culottes: Working-class heroes demanding bread… but also executing people for not being radical enough.

Verdict

The Revolution was 75% based because it dismantled feudalism, spread democratic ideals, and gave us iconic art/memes (see: Liberty Leading the People). But the 25% cringe—hyper-violence, ideological purity spirals, and Napoleon’s audacity—keeps it from being a flawless 10.

Final Tier: "Messy but iconic. Would revolution again."

67 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Storming of the Bastille was a decisive moment in the early months of the French Revolution (1789-1799). On 14 July 1789, the Bastille, a fortress and political prison symbolizing the oppressiveness of France’s Ancien Régime was attacked by a crowd mainly consisting of sans-culottes, or lower classes. The anniversary is still celebrated in France as the country’s national holiday. The event was the culmination of multiple different causes. Although the catalyst for the attack was the dismissal of popular Genevan commoner Jacques Necker (1732-1804) from the ministry of King Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792), societal imbalances and financial hardships had been pressuring the French people for years. The perceived efforts of the king to undo the work of the Estates-General of 1789, which had resulted in the formation of a National Assembly dominated by members of the Third Estate, combined with rising bread prices to send the people of Paris into a panic, causing them to lash out against symbols of royal authority, including the ever-looming Bastille. While the storming of the Bastille was significant in that it saw the first large-scale intervention by the sans-culottes in the Revolution, it was also one of the first instances of bloodshed and mob rule committed by revolutionaries in what had previously been a relatively peaceful and orderly affair. Still, the event marked a major turning point in which the powers of the king were diminished and the process of dismantling the monarchy began.

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

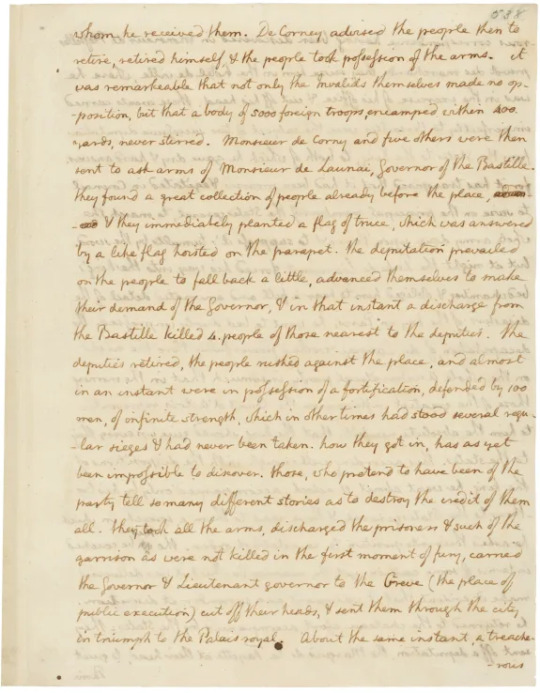

Letter from Thomas Jefferson to John Jay

Record Group 360: Records of the Continental and Confederation Congresses and the Constitutional ConventionSeries: Papers of the Continental CongressFile Unit: Letters from Thomas Jefferson

Paris July 19 1789.

Dear Sir

I am become very uneasy lest you should have adopted some channel for the conveiance of you letters to me which is unfaithful. I have none from you of later date than Nov. 25. 1788. and of consequence no acknolegement of the receipt of any of mine since that of Aug. 11. 1788. since that period I have written to you of the following dates 1788. Aug. 20 Sep. 3. 5. 24. Nov. 14. 19. 29. 1789. Jan. 11. 14. 21. Feb 4. Mar. 1. 12. 14. 15. May. 9.11.12 Jun 17.24.29. I know through another person that you have received mine of Nov. 29. that you have written an answer; but I have never received the answer, and it is this which suggests to me the fear of some general source of miscarriage.

The capture of three French merchant ships by the Algennes under different pretexts has produced great sensation in the seaports of this country, and some of it's government. They have ordered some frigates to be armed at Toulon to punish them. There is a possibility that this circumstance, if not too soon set to rights by the Algennes, may furnish occasion to the States general. Then they shall have leisure to attend to matters of this kind to disavow any future tributary treaty with them. These pyrates respect still less their treaty with Spain, and treat the Spaniards with an insolence greater than usual before the treaty.

The scarcity of bread begins to lessen in the Southern parts of France where the harvest is commenced. Here it is still threatening because because we have yet two or three weeks to the beginning of harvest and I think there has not been three days provision beforehand in Paris for two or three weeks past. Monsieur de Mirabeau, who is very hostile to Mr Necker wished to find a ground for censuring him in a proposition to have a great quantity of flour furnished from the United States which he supposed me to have made to Mr. Necker, & to have been refused by him; and he asked time of the states general to furnish proofs.The Marquis de la Fayette immediately gave me notice of this matter and I wrote him a letter to disavow having ever made any such proposition to Mr Necker, which I desired him to communicate to the states. I waited immediately on Mr. Necker and Monsieur de Montmorn, satisfied them that what had been suggested was absolutely without foundation from me, and indeed they had not needed this testimony. I gave them copies of my letter to the Marquis de la Fayette, which was afterwards printed. The Marquis, on the receipt of my letter, shewed it to Mirabeau, who turned then to a paper from which he had drawn his information. I found he had totally mistaken it. He promised immediately that he would himself declare his error to the States general and read to them my letter, which he did. I state this matter to you, tho' of little consequence in itself, because it might go to you mistated in in the English papers-our supplies to the Altantic ports of France during the months of March, April, & May were only quintals 12,220 - 33 of flour and quintals 44,115 - 40 of wheat, in 21 vessels.

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Storming of the Bastille and arrest of the Governor Marquis de Launay, 14 July, 1789

#storming of the bastille#paris#france#french revolution#art#fortress#armoury#prison#medieval#castle#french#history#europe#european#unknown artist#anonymous artist#marquis de launay#bernard rené jordan de launay

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Camille Desmoulins and Antoine-François Momoro

Antoine-François Momoro Camille Desmoulins

I couldn't say exactly how, but I have the impression that the printer-bookseller Antoine-François Momoro and the pamphleteer Camille Desmoulins had very opposite paths and were very different despite having similarities, if you know what I mean. Camille Desmoulins was a republican from the start, while Momoro was cautious on the matter and hesitated to publish Desmoulins' pamphlet "La France Libre" in June 1789, only releasing it on July 17, 1789. However, Momoro increasingly engaged in the revolution, eventually becoming one of its key figures and a regular at the Cordeliers Club. He was arrested after the Flight to Varennes, having signed the Champ de Mars petition. Desmoulins, on the other hand, had to go into exile. In this regard, they shared the common ground of being among the harshest critics of the monarchy, although Desmoulins had been vocal much earlier, opposing the property-based suffrage in 1789 and circulating 3,000 copies of his journal "Les Révolutions de France et de Brabant." During the Varennes episode, Momoro ensured that many issues of the Cordeliers Club Journal, which became virulent towards the king due to his escape, were distributed.

Both Camille Desmoulins and Momoro participated in the events of August 10, 1792. While Desmoulins left his mark as a key figure of July 14, 1789, Momoro, alongside Mayor Pache, inscribed the words "Liberty, Equality, Fraternity" on public buildings in the summer of 1793. Both played roles in the expulsion of the Girondins. Desmoulins was elected to the Convention, whereas Momoro, though not elected, played a significant role in the Paris Commune, overseeing supplies and soldier morale, among other tasks. He recruited volunteers from various departments and regions and was sent to Vendée alongside Charles Philippe Ronsin. Both men remained actively involved in what was considered a faction until the end, in contrast to their leaders Danton and Hébert, who were less ardent or coherent (although there were no real leaders, if you understand my point).

Their wives played more significant political roles alongside their companions than often portrayed in films. Lucile Desmoulins' journal shows her as a fervent critic of the monarchy, writing dark texts about Marie-Antoinette, approving the King's execution, and defending Camille when the future Marshal Brune asked him to temper his critiques in "Le Vieux Cordelier." Sophie Fournier, Momoro's wife, played a crucial role in her husband's dechristianization campaign, representing the Goddess of Reason armed with a pike at each ceremony (when you consider the struggle of the women of the Revolution to bear arms, in my opinion, it only demonstrates her great determination ). Both Momoro and Desmoulins had only one son from their marriages, and their wives were subject to sexist attacks, similar to Manon Roland, Louise Gély, Marie Françoise Goupil, and even Marie-Antoinette.

However, their paths diverged significantly. Initially cautious, Momoro became increasingly revolutionary, ultimately considered an ultra-revolutionary, while Desmoulins became more moderate. Momoro began to advocate for property rights redistribution, a stance not shared by Desmoulins or many Montagnards, who were moderate on this issue. Momoro supported de-Christianization, while Desmoulins opposed it. Momoro called for harsher measures against counter-revolutionary suspects, whereas Desmoulins, in "Le Vieux Cordelier," called for leniency (except for approve the mock trial of the Hébertists) and advocated for the mass release of counter-revolutionary suspects, many of whom were innocent. During the harsh winter of 1793-1794, Momoro prioritized the suffering of the Parisian masses, a concern Desmoulins did not share.

Despite this, Momoro and many considered Hébertists were sent to the guillotine. It is said that Momoro died bravely, like most of his colleagues except Hébert (his bravery was remarkable given that his wife Sophie was arrested ten days after him, and he knew she could die, yet he refused to show fear in public). Desmoulins, calm when preparing for death, panicked when Lucile was arrested (as unjustly as the arrests of the Hébert and Momoro wives) and expressed his despair all the way to the scaffold. The most horrifying part is that Desmoulins and Momoro learned of their wives' arrests the day before their execution.

My personal reflections: Honestly, I believe there is a golden legend about Camille Desmoulins, which he does not deserve, and a black legend about Momoro's faction, which is also undeserved . As I mentioned in this post https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/744960791081631744/the-difference-in-treatment-between-the-indulgents?source=share, in my eyes, Camille Desmoulins is highly overrated. While I do not deny his talents, I do not think he was fit for great responsibilities, unlike men he mocked, like Ronsin, Saint-Just, or Momoro, who worked tirelessly during the revolution's most challenging period. I must say in my eyes that once Desmoulins became a Convention deputy, he seemed to rest more than other revolutionaries. Consider Sonthonax, labeled a Girondin, who accepted a mission to Saint Domingue to better fight against colonizers who denied equal rights between people of color and whites, or Condorcet, who worked with Carnot on women's education with Pastoret and Guilloud, or Charles Philippe Ronsin. Many members of the Committee of Public Safety had grueling schedules in addition to their missions. Other Convention deputies, unlike Desmoulins, were sent on missions, such as Charles Gilbert Romme (and many others). While Desmoulins advocated leniency in "Le Vieux Cordelier," he approves the mock trial that led to the Hébertists' guillotining and said nothing about their wives' arrests (perhaps he planned to call for their release to be fair, but I don't know). Besides being partly responsible for the fall of the Brissotins, he remained silent on the illegal harassment Jacques Roux faced, leading to his suicide, and once said he understood the need to curb liberty for the people's salvation. Nonetheless, Camille Desmoulins should never have been arrested, let alone executed, as he only wrote articles.

In comparison, Momoro, a victim of a black legend, was clearly more honest about following a consistent line. Initially more cautious than Desmoulins in 1789, he ultimately advocated for more social rights. Despite not being elected to the Convention, he played a significant role in the Paris Commune, carrying out various missions during the revolution's most challenging period, from late 1792 to early 1794. During the Convention's invasions, he was among those who demanded vital laws for the revolution, such as the maximum or the revolutionary army's levy. His attempted insurrection was mainly due to the severe suffering of the Parisian masses in the winter of 1793-1794 and the frequent attacks on the Hébertists by the Convention (the arrests of Ronsin and Vincent in 1793), while dubious characters like Danton were free. Momoro was never rehabilitated, unlike Desmoulins, who was falsely accused of sabotaging supplies and destroying his reputation by accumulating 190,000 livres in cash, although he always refused to elevate himself, leaving behind only 26 livres and 400 livres in assignats. As Mathiez Albert, a historian harsh on Robespierre's opponents, said, "One of the main leaders of this Hébertist party, who first tried to translate and represent the popular aspirations against the wealthy bourgeois of the Convention [...] He died poor, as he had lived."

However, Momoro also had his faults, and Desmoulins was right on some points. Nothing is entirely black or white, especially among revolutionaries. The dechristianization campaigns often caused problems for the French Revolution. I understand the anger of incorruptible revolutionaries like Momoro, given the religious intolerance of that time, but intolerance cannot be fought with more intolerance. These campaigns also alienated many French people.

Moreover, if Desmoulins had dubious political allies in Danton, Momoro could be worst. He counted as an ally the horrible Nantes drowner, Carrier (Momoro didn't drown people by the way, but still a bad point for him...). Many French Revolution characters made alliances with dubious figures (like Robespierre, who knew the criticisms against Danton were well-founded but largely allied with him until a certain point), but it's still a big no for me for the alliance with Carrier. Not with one of the most hateful characters of the French Revolution. His last insurrection attempt, which led to his guillotining, was understandable, but the Convention was at a critical point and could not afford a new insurrection. Unlike Hanriot and Chaumette, he was not lucid enough on this point. He should have been more lenient with the suspect laws. Plus let's not forget that the faction call hebertist who after denunce the faction call enragés took them petition.

Even if I am harsh on Camille Desmoulins, I must acknowledge his great courage and contributions to the French Revolution, and like Momoro, he never betrayed his principles. Moreover, I fully agree with him on press freedom and often highlight his reasoning on freedom of expression. It's worth noting that Camille Desmoulins' father died shortly after his son's execution, heartbroken by his loss, just as Momoro's mother, a servant in Besançon, died a week or two after her son's death. Regardless of what one might say, both revolutionaries earned the right to be considered important figures in the 1789-1794 period.

I would like to end with two phrases these two revolutionaries reportedly said shortly before their deaths:

Momoro, during his condemnation: "I am accused, I who gave everything for the Revolution!"

Camille Desmoulins in jail : "I had dreamed of a republic that everyone would have adored."

P.S.: I have searched everywhere for a biography of Sophie Fournier, Momoro's wife. I found it in PDF and French, but I don't know its value.

Here is the link : https://www.sh6e.com/images/publications/Lettre_d_information/2023_05_Lettre_info_Sh6.pdf

#frev#french revolution#camille desmoulins#lucile desmoulins#momoro#sophie momoro née Fournier#cordeliers#hébertistes#indulgents

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

“France is in the throes of violent birth”: Thomas Jefferson and the 1789 French Revolution

"The deputies retired, the people rushed against the place, and almost in an instant were in possession of a fortification, defended by 100 men, of infinite strength..."

• Ambassador Thomas Jefferson report on the events on 14 July 1789.

The excerpt shown here is from a letter in Jefferson’s own hand to Secretary of Foreign Affairs John Jay. In great depth, he describes the events of July 14, 1789, including the storming of the Bastille in Paris. The Bastille was a symbol of the old regime, and housed arms, gunpowder, and prisoners.

On 14 July 1789, the U.S. Ambassador to France, Thomas Jefferson, was a witness to the events of a day in Paris that is commonly associated with the beginning of the French Revolution. Jefferson recorded the events of the day in a lengthy and detailed letter to John Jay, then Secretary of Foreign Affairs.

The American Revolutionary War began as a conflict between the colonies and England. In time, what began as a civil disturbance turned into a world war drawing France, Spain, and the Netherlands into the hostilities. France would send troops, ships, and treasure to support the American effort. During the war, one of the first priorities of the French government and its allies was to raise funds to fight the war.

When the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1783, France was virtually broke and on the edge of social catastrophe, the result of decades of war with England and other countries. The poor suffered hunger and privation. By 1789, revolution would come to France.

In 1785, Thomas Jefferson arrived in Paris to replace Benjamin Franklin, who was retiring as ambassador to France. At the age of 81, Franklin returned to the United States where he would serve as President of the Pennsylvania Assembly and also participated in the Constitutional Convention of 1787.

John Adams was reassigned to London where he would be the first American ambassador to the Court of St. James. Jefferson remained on duty in France until late 1789 when he returned to the United States. While in France, Jefferson reported on developments at the court of King Louis XVI, the country at large, and the rest of Europe.

Jefferson was sympathetic to the revolution, opening his home in Paris to its leaders and assisting his friend the Marquis de Lafayette with drafting the Declaration of the Rights of Man. As the first Secretary of State under the Constitution and George Washington, his support for France and the revolution continued.

His friendship to the Marquis de Lafayette, who served in the War of Independence and lived almost 10 years in the USA, became very important in the beginning of the French revolution. The Marquis was the General of the french forces 1789 and tried to prevent a civil war and turmoil. He corresponded with Jefferson, who came from a country with the same experiences. Jefferson and the Marquis agreed that France was not mature to become a republic but a constitutional monarchy, like in Great Britain. However, this was the decision of the national assembly, of which the Marquise was a member. Jefferson went daily to Versailles to inform himself about the decisions. During Jefferson’ s visits, they passed the following laws:

1. Freedom of the person by habeas corpus 2. Freedom of conscience 3. Freedom of the press 4. Trial by jury 5. A representative legislature 6. Annual meetings 7. The origination of laws

This totally fit to Jefferson’s principles. In addition, there was passed a bill, which was prepared by Lafayette and Jefferson and which abolish any title or rank to make all men equal.

Thomas Jefferson also helped his friend Lafayette to bring the different opinions in his party about the constitution to an agreement. France should become a constitutional monarchy.

However, after this, Jefferson recognised that he is not allowed to interfere in the French domestic affairs and that he should be neutral and represent his country. He left France in the thinking that the Revolution was over and that France would grow to a constitutional monarchy. Jefferson was proud of the achievements in France and after his return to USA he declared: “ So ask the travelled inhabitant of any nation, In what country on earth would you rather live? - Certainly, in my own where are all my friends, my relations, and the earliest and sweetest affections and recollections of my life. Which would be your second choice? France."

For all his francophile fervour, as the chief American diplomatic representative, Jefferson’s Enlightenment had been a conventionally English one, dominated above all by John Locke. And Jefferson’s first impressions of America’s principal ally in the Revolution were not positive ones. “The nation,” he confided to Abigail Adams in 1787, “is incapable of any serious effort but under the word of command.”

The stars of the French Enlightenment - Voltaire, Diderot, d’Holbach - were frivolous and useful only for manufacturing “puns and bon mots; and I pronounce that a good punster would disarm the whole nation were they ever so seriously disposed to revolt.”

The events of the spring of 1789 soon changed all of that before Jefferson’s very eyes. “The National Assembly,” he excitedly wrote to Tom Paine, “having shewn thro’ every stage of these transactions a coolness, wisdom, and resolution to set fire to the four corners of the kingdom and to perish with it themselves rather to relinquish an iota from their plan of a total change of government” had excited Jefferson’s imagination as nothing before.

Even when the Paris mob seized the Bastille and beheaded the hapless officers of the Bastille, Jefferson shrugged it aside as a mere incident, since “the decapitations” had accelerated the king’s surrender. As Jefferson would write later, “in the struggle which was necessary, many guilty persons fell without the forms of trial, and with them some innocent.” But rather than seeing the French Revolution fail, “I would have seen half the earth desolated. Were there but an Adam and an Eve left in every country and left free, it would be better than as it now is.”

Jefferson’s admiration for the French Revolution seemed to increase in direct proportion to his distance from it. And once he returned to America at the end of 1789, one of his chief motives for taking the post of Secretary of State was to observe and encourage the French eruption, when the National Assembly seized and redistributed the lands of the Catholic Church, when the king foolishly attempted to flee France, only to be captured, placed on trial and executed.

And when a Committee of Public Safety began a national purge - the “reign of terror” - Jefferson continued to describe the French Revolution as part of “the holy cause of freedom,” and sniffed that “the tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants. It is its natural manure.”

There is no question that Jefferson’s influence in the beginning of the French Revolution was very important. His initial moderate counsels and ideas helped in the beginning to prevent a civil war. His opinion that France was not mature to become a republic is probably right, because after 600 years of monarchy and aristocracy they people were not used to have any rights or take part in political matters. Jefferson thought that a republic had to develop from a constitutional monarchy. When you look to the cruel end of the French Revolution, Jefferson’s assessment was right up to a point.

Jefferson’s time as Secretary of State coincided with the most explosive phase of the French Revolution. What started as an attempt to dismantle the Ancien Régime and institute a constitutional monarchy blossomed into a radical experiment in creating an entirely new republican society. As his correspondence with Minister to France Gouverneur Morris and Minister to the Netherlands William Short during the emergence of the Jacobin Terror reveals, Jefferson responded to the violent radicalisation of the Revolution with enthusiastic support.

His advocacy for the French Revolution did not signify his emergence as a disruptive insurrectionist in favour of purposeless violence, anarchy and unbridled populism. Instead, he advocated for recognition and support of the Jacobin government as a successful international analog to the republican project he wanted to pursue at home at the expense of the “monarchical” aspirations of Hamilton and the Federalists.

In practice, the parallels he imagined between the ideal Jeffersonian and Jacobin republics were usually more apparent than real, as Jefferson often ignored the reports of Morris and Short in favour of fanciful idealising of his French counterparts – a problem Jefferson would only come to grips with in retirement.

Despite these dilemmas, Jefferson’s impassioned advocacy for the French Revolution proved effective, emerging as a cornerstone of the burgeoning Republican Party’s foreign policy and remaining important well into the early nineteenth century, until the Revolution ceased to be an important political issue. It was not until he became President in 1801 that Jefferson’s views toward France began to cool and became more pragmatic, highlighted by the Louisiana Purchase Treaty.

#thomas jefferson#jefferson#french revolution#14 july 1789#bastille day#america#france#french#monarchy#republic#history#politics#ideology#jacobin#essay#diplomacy#ambassador#jefferson in paris#paris

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fête de la Fédération

Fete de la Federation was a massive festival celebrated on July 14, honoring the French Revolution. The day was the predecessor of Bastille Day, as celebrated today. The point of the festival was to celebrate both the Revolution and the spirit of National Unity. At the time, the Revolution had overthrown the excesses of the French monarchy and replaced it with a constitutional monarchy, led by an elected National assembly. The Fete de la Federation was organized to coincide with the first anniversary of the storming of the Bastille. The festival came at a time when people believed that the revolution was over, though turmoil would follow in the coming years.

History of Fete de la Federation

The French Revolution began in 1789 with that year’s Estates-General. The abolition of the reigning ‘Ancien Régime’ or Old Regime began on July 14, 1789, when a crowd of protesters stormed the Bastille prison. By 1790, the monarchy had been overthrown and a National Assembly was elected. Believing the Revolution to be over, a desire to celebrate national unity spread across the French people. The festival in Paris was to be the most prominent celebration of fraternity — it was to be attended by the royal family, the deputies of the National Assembly, and the general public. The event was organized on the Champ de Mars, which was outside Paris at the time.

The festival began with a feast as early as 4:00 A.M., and it continued to proceed despite downpours throughout the day. A parade of ‘federes’ organized under 83 banners marched their way to the place the Bastille once stood, and the members of the National Assembly, along with Louis XVI, all took an oath to protect the new Nation. The festival was also attended by delegates from countries across the globe. A popular feast followed the official celebration.

Unbeknownst to all those who attended the festivities, the stability that they foresaw was not what they had in store for them. The following years in France were of political turmoil that culminated in the people becoming disillusioned with the monarchy, leading to the execution of the royal family in 1973. Even with the French Republic finally established, peace did not follow. June 1973 saw an uprising that overthrew much of the National Assembly, sparking the Reign of Terror in the nation. The following year saw 16,000 at the hands of the Jacobins. To deal with the oppressive threat of the former, a fragile French Directory was formed, which was soon overthrown by Napoleon Bonaparte, marking the end of France’s revolutionary period.

Fete de la Federation timeline

June 13, 1789 Estates General of 1789

The Third Estate forms the National Assembly.

July 14, 1789 Storming of the Bastille

Revolutionaries storm the Bastille prison.

July 14, 1790 Fete de la Federation

The Fete de la Federation is organized to celebrate the French Revolution.

January 1793 Monarch beheaded

Louis XVI is beheaded.

Fete de la Federation FAQs

What is July 14 in France?

It is celebrated as Bastille Day.

When was the French Revolution?

May 5, 1789, to November 9, 1799.

What is the name of the flag of France?

It is called the ‘Tricolore.’

How to Observe Fete de la Federation

Read about the French Revolution

Watch a documentary

Look up related philosophy

The French Revolution was a turning point in history. Spend the day reading about it.

If reading isn’t your thing, pop in a documentary about the Revolution! You’re bound to find something entertaining. You can even try a movie or two, like “Les Miserables” or “Marie Antoinette.”

The French Revolution was built on a foundation of ideas like equality, liberty, and justice. Learn more about these abstractions and what philosophers have said about them.

5 Interesting Facts About France

Tourism

National motto

Inventions

Highest European mountain

Most visited museum

France is the world’s most popular tourist destination.

The national motto of France is “Liberté, égalité, fraternité” or “liberty, equality, fraternity.”

The French invented the hot air balloon!

The tallest mountain in Europe, Mont Blanc, is in France.

The Louvre is the world’s most visited museum.

Why Fete de la Federation is Important

It’s an important part of French history

It’s a reminder of humanity

It’s an opportunity to learn about the French Revolution

The French Revolution formed the basis of the modern state of France. Fete de la Federation is an important part of it.

The French Revolution often entailed sequences of violent events. An earnest celebration of what people thought would be a peaceful regime reminds us of how human everyone in history was.

The Revolution is a major part of world history. The Fete de la Federation is a perfect excuse to learn more about it.

Source

#travel#original photography#vacation#tourist attraction#landmark#cityscape#architecture#landscape#14 July 1789#anniversary#French history#French National Celebration#France#summer 2021#Fête de la Fédération#Cruseilles#Saint-Nazaire-en-Royans#Isère#French Alps#Triumphal Arch of Orange#Fitou#Camaret-sur-Aigues#Pont du Gard#French National Day#Bastille Day

1 note

·

View note

Text

🗺️🇫🇷🎇 [Special History] The Men took the Bastille, and the Women took the King

“The revolution of October 6, necessary, natural and legitimate as it was, entirely spontaneous, unexpected, truly popular, belongs mostly to women - The men took the Bastille, and the women took the king.” (Jules Michelet)

🇫🇷🎇 [Spécial #Histoire] Les Hommes ont pris la Bastille, et les Femmes ont pris le Roi

“La révolution du 6 octobre, nécessaire, naturelle et légitime, s’il en fut jamais, toute spontanée, imprévue, vraiment populaire, appartient surtout aux femmes - Les hommes ont pris la Bastille, et les femmes ont pris le roi.”(Jules Michelet)

#14 juillet#july 14#history#histoire#education#éducation#learning#apprendre#national holiday#fête nationale#french revolution#révolution française#revolution#révolution#bastille day#jour de la bastille#bastille#culture#fête#festival#fête de la fédération#1789#1790#french#français#english#anglais#women rights#equal rights

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ms. Sans-Culotte and the obvious French Revolution symbolism

This episode is a field day for me, so I'll need to analyse it bit by bit. Let's first start with the obvious and less obvious French Revolution references in this episode. This will be especially obvious for French viewers, but I thought that it may be interesting for others.

Sans-culotte

I know that the term sounds funny to most, but sans-culottes are a key figure in the French history. Those were the commoners who revolted to the King and aristocracy, and undertook the French Revolution of 1789. As Mademoiselle Bustier explains in the beginning of the episode, the sans-culottes were called so because:

Contrary to rich aristocrats, they would wear simple pants.

So when Mlle. Bustier is akumatised, we see the following character design:

THE PANTS. Very obviously the pants. But there are more obvious symbols in this character design.

Marianne

Marianne is the national personification of the French Republic. She is very much synonymous with the free and republican spirit of France. Yes, that's also the name of Master Fu's girlfriend, and for good reason (she was a Résistance fighter during the German occupation of France!).

By the way this exact painting is in the background in the few seconds after Mlle. Bustier is akumatised:

Marianne is usually depicted with the following symbols:

the Phrygian cap

Greco-Roman clothes

Partial nudity

We see these signs in Mlle. Sans Culotte's character design.

Mlle. Sans Culotte's helmet has the unique shape of the Phrygian cap.

2. Mlle. Sans Culotte is dressed in a Greco-Roman armour. The usual depiction of Marianne is in flowy Greco-Roman clothes, but the helmet and armour really add to that fighter spirit of Mlle. Sans Culotte. Also, even though rarer, there are some depictions of Marianne with a Greco-Roman armour.

3. Partial nudity. Obviously they couldn't actually show that on a kids show. However, I think that the character design does hint to a type of nudity. The fact that the white of the French flag covers all of Mlle. Bustier's face and body make it seem like it is not actually her clothes but her skin. And other than the golden armour she wears, she has no other clothes on her.

The Guillotine

Mlle. Sans Culotte's weapon of choice is a freaking guillotine knife. This was a device used by the French revolutionaries to behead their opponents. To this day, it is associated with the violence of the French revolution.

Now to more implicit references:

Ça ira

When Mlle. Sans Culotte hits people, they turn into balloons that chant:

Ça ira, ça ira, ça ira!

Which is a song sang by the sans-culottes during the French Revolution (thanks to @2manyfandoms2count for helping out with this one!)

Other quotes and remarks

There are various quotes throughout the episode with a revolutionary lexicon.

Monarch: The power of Jubilation will help you show the people their dream of freedom, and as such gain partisans/supporters to your cause.

Monarch: To arms, citizens! Form batallions!

This one is especially striking for me, because it is very explicit call to violence (frequently used in French revolutionary history too).

Mlle. Sans Culotte: No one stops the revolution. Long live the revolution!

She quite literally says Vive la révolution. Seriously, it doesn't get any more obvious than that.

She literally runs head-first into a group of policemen, paralleling the Storming of the Bastille on 14 July 1789. And literally afterwards Chat Noir mentions this same event:

Chat Noir: It is not the 14th of July, my Lady. Do you think that this akuma victim wants to celebrate the Bastille Day early?

And later on:

Mlle. Sans Culotte: Ladybug, Chat Noir! Help the sans-culottes (plural!) to liberate Paris from its aristocratic Mayor!

Ladybug: Terror is not the solution!

Chat Noir: To get your voice heard there are the elections!

Ok, the word "terror" here is important. I had previously mentioned in my post on Felix's anarchist revolution that the French Revolution was followed by a period of violence where all those against the revolution were murdered. The name of the period is literally the Reign of Terror. We see that Ladybug's words is a reference to that.

Ladybug: (after receiving her lucky charm) Revolution, sans-culotte, and the Mayor of Paris who acts like the King?

The parallel is there. They're not even trying to be subtle. This is the retelling of the French Revolution.

Except that it doesn't turn out like the French Revolution. In the end, Mr. Bourgeois willingly steps down, Mlle. Sans Culotte rejects Monarch's powers (as in, she drops her weapons), so there is no revolution and no bloody reign of terror.

But still, the power dynamics end up shifting tremendously in the Miraculous Paris. How and why? I'll make a post specifically analysing this. Stay tuned for part two!

(Also, I have likely forgotten or omitted some other symbols, feel free to add them to the comments - if there are enough, I can make an addition to the post :))

297 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pauline Léon timeline

A timeline over the 70 year old life of Pauline Leclerc née Léon, based primarily on the article Pauline Léon, une républicaine révolutionnaire (2006) by Claude Guillon.

-

19 October 1767 — Mathurine Téholan and Pierre Paul Léon are married in the parish of Saint-Severin in Paris. Pierre Paul runs a small chocolate business on 356 rue de Grenelle. The couple settles on rue du Basq.

28 September 1768 — birth of Anne Pauline Léon, the couple’s first child. They later have four more children — Antoine Paul Louis (1772-1835), Marie Reine Antoinette, (1778), François Paul Mathurin (1779) as well as a child who’s sex and year of birth remains unknown. Pauline later describes her father as: ”a philosopher” and adds: ”If his lack of fortune did not allow him to give us a very brilliant education, at least he left us with no prejudices.”

1784 — death of Pierre Paul Léon. Pauline, aged sixteen, now starts helping her mother with keeping the chocolate business running in order to provide for the family.

14 July 1789 — Fall of the Bastille. Pauline claims to upon this event have felt ”the liveliest enthusiam, and although a woman I did not remain idle; I was seen from morning to evening animating the citizens against the artisans of tyranny, urging them to despise and brave aristocrats, barricading streets, and inciting the cowardly to leave their homes to come to the aid of the fatherland in danger.”

February 1791 — Pauline is introduced to several popular societies in Paris. She herself claims she would frequent the Cordelier Club up until 1794 (though there doesn’t seem to exist any trace of her in the debates held there), the Fraternal Society of Patriots of Both Sexes (where again, we have few documents that mention any direct activity from her part), as well as the section of Mucius Scaevola. The same month, Pauline defenestrates a bust of Lafayette “at Fréron’s”. It seems unlikey for this attack to have been aimed at the journalist Stanislas Fréron, who frequently denounced Lafayette in his l’Orateur du Peuple, but rather his mother Anne Françoise Fréron, who handled the publishing of the royalist paper L’Ami du Roi.

21 June 1791 — Pauline, her mother and their neighbor Constance Évrard are near the Palais Royal loudly protesting the king’s ”infamous treason” (his flight) when they, according to her, are ”almost assassinated by Lafayette’s mouchards” and are saved by other sans-culottes who manage to snatch them ”from the hands of these monsters” (National guardsmen)

17 July 1791 — Pauline takes part in the demonstration on the Champ-de-Mars. On the way home, she uses her fists to defend a friend against the family of a national guard. This last incident is witnessed by Constance Evrard, another sans-culotte woman and friend of Pauline, who reports it during an interrogation. This is the first conserved trace of any militant activities from Pauline.

Late February 1792 — l’Adresse individuelle à l’Assemblée nationale par des citoyennes de la capitale, a petition regarding women’s right to bear arms, is penned down. It was most likely written by Pauline herself, seeing as the first signature on the bottom of the handwritten version kept in the National Archives, as well as the only one appearing in the version printed by order of the Assembly, is “fille Léon.” After Pauline’s name about 310 more follow, including that of her mother and many other daughter-mother couples. The petition is first read out before the Society of Patriots of Both Sexes, which, under the presidency of Tallien, orders its printing and distribution.

March 9 1792 — the Patriotic Society of the Luxembourg section sends a delegation to the Fraternal Society of Patriots of Both Sexes to request affiliation. The latter club grants the request and appoints five auditors to attend the former’s next meeting, among which are three women: Pauline Léon, Constance Evrard and Marie-Charlotte Hardon. Pauline will actively participate in the recruitment of members for the Patriotic Society, personally presenting or supporting at least seven candidates between October 1792 and September 1793

June 1792 — Pauline, along with many other men and women, signs Pétition individuelle au corps législatif pour lui demander la punition de tous les conspirateurs that calls for ”a quick vengeance” against monarchist ministers.

10 August 1792 — Pauline takes part in the Insurrection of August 10. She describes her activities in the following way: "On August 10, 1792, after spending part of the night in the Fontaine-de-Grenelle section, I joined the next day, armed with a pike, the ranks of the citizens of this section to go and fight the tyrant and his satellites. It was only at the request of almost all the patriots that I consented to give up my weapon to a sans-culotte; I gave it to him, however, only on the condition that he would use it well.”

December 1792 — Pauline, together with 3 other women and 88 men, signs the Adresse au peuple par la Société patriotique de la section du Luxembourg which demands the death of the king and pronounces threats against eventual monarchist deputies.

2 February 1793 — During a session at the Fraternal Society of Patriots of Both Sexes, Pauline is welcomed as mandated by the Defenders of the Republic of the 84 departments. At the same session, Pauline’s future husband Théophile Leclerc (1771-1820) is charged with writing a petition against commodity money. This is the first known meeting between the two.

3 February 1793 — during the session at The Fraternal Society of Patriots of Both Sexes, ”Citoyenne Léon” takes the floor to continue a denounciation against Dumouriez that Hébert has just made. Le Créole patriote reports that ”she thinks, like him, that [Dumouriez] is nothing more than an intrigant; she accuses him of several things, notably the persecution he inflicted on two patriotic battalions unjustly accused by him.”

10 February 1793 — Le Créole patriote reports the following regarding the session at The Fraternal Society of Patriots of Both Sexes:

Citoyenne Léon informs of an important denunciation made to the Commune and to the society of defenders of the republic, one and indivisible of the 84 departments. This denunciation, signed, states that on the 6th of the month a dinner was held at the house of Garat, minister of justice, provisionally exercising the functions of minister of interior, where Brissot, Barbaroux, Louvet and other noirs, composing the great and famous right side of the National Convention; plus, Bournonville, new minister of war. She calls on the society to monitor the latter, and asks that two of its members be sent to that of the Jacobins to communicate to them this fact, to which the most serious attention must be paid. Boussard makes the motion that the president be instructed to write to Bournonville, so that he can give the company explanations on this subject. These three proposals are adopted.

At the Jacobin Club the same day, ”a citoyenne,” in the name of the Fraternal Society of Patriots of Both Sexes, makes the following intervention: ”Citizens, I denounce to you Garat, minister of justice, who last Wednesday had thirty people to dinner, among which were Brissot, Barbaroux, Louvet and Beurnonville. The patriots do not have entry to this minister, and Brissot comes and goes there all the time.” It is very likely this speaker was Pauline.

17 February 1793 — Le Créole patriote reports that, during the session at The Fraternal Society of Patriots of Both Sexes, ”citoyenne Léon reads a denunciation from Citizen Godchaux against General Félix Wemphen. Several members believe that this denunciation is well founded, and urge the society to tear off the mask from all the intriguers.”

10 May 1793 — Pauline is a co-founder of the Society of Revolutionary and Republican Women (Société des Républicaines révolutionnaires or Société des citoyennes républicaines révolutionnaires de Paris), a club which only admits women as members and holds its meetings at the libary of the Jacobins, rue Saint-Honoré. Claire Lacombe, who often gets mentioned as another co-founder, actually doesn’t have her first attested appearance as a member of the society until June 26. Already on May 12, the club presents itself at the Jacobins, proposing to arm patriotic women between ages 18 and 50 in order to organize them against the Vendée. A week later, May 19, a delegation made up of members from both the Cordeliers and Revolutionary and Republican Women present themselves before the Jacobins yet again, asking for the arrest of all suspect people, the establishment of both revolutionary tribunals in all departments and a revolutionary sans-culotte army in every town, an act of accusation against the girondins, the extermination of “the stockbrokers, the hoarders and the selfish merchants” who are responsible for a conspiracy attempting to starve the people, that the revolutionary army of Paris be increased to 40,000 men, that land be distributed to the soldiers, as well as the send forth of the petition to the Convention. Though Pauline’s presence can be supposed for both of these occasions, we don’t have any hard evidence for it.

2 June 1793 — Pauline leads a delegation from the Society of Revolutionary and Republican Women wishing to be admitted to the Convention, carrying a request in her own handwriting. They are however quickly forgotten in the tumult caused by the Insurrection of May 31, which this day ends with 22 girondins being put under house arrest. During this same insurrection, several Revolutionary and Republican Women are arrested, and Pauline, as president of the Society, signs a warrant by which they demand the liberation of one of them, detained for having threatened three men with a knife.

June 1793 — Pauline is the author of a denounciation against the grocer Le Doux, rue du Sépulcre, accused of “bad comments,” mainly consisting of complains about the looting. We don’t know if the denounciation had any consequences.

9 July 1793 — Le Réglement de la Société des citoyennes républicaines révolutionnaires de Paris is published. The document is signed by president Rousaud and four secretaires: Potheau, Monier, Dubreuil och Pauline Léon.

July 10 1793 — Pauline goes to the Jacobin club, where she, ”in the name of the Revolutionary and Republican Women, presents a petition demanding the exclusion of nobles from all employments.”

July 20 1793 — A Délibération de la Société des Républicaines révolutionnaires, relative à l’érection d’un obélisque à la mémoire de Marat, sur la place du Carrousel, is signed by Pauline. The text is read at the Jacobins on July 26, by a deputation from the Society of Revolutionary and Republican Women.

July 31 1793 — Réglement de la Société des citoyennes républicaines révolutionnaires de Paris is published. The document is signed by the president, Rousaud, and four secretaries: Potheau, Monier, Dubreuil and Pauline Léon.

15 August 1793 — At the Jacobin club, ”citoyenne Léon, at the head of a deputation from the Society of Revolutionary and Republican Women, comes to request assimilation and correspondence for said Society. She also asks that the Jacobins contribute to the costs of the obelisk erected in Marat’s honor.”

30 October 1793 — Jean Pierre André Amar, member of the Committee of General Security, announces the dissolution of the Society of Revolutionary Women to the National Convention.

12 November 1793 — the marriage contract between Pauline Léon and Théophile Leclerc is signed. Through it, we see that the husband brings property valued at 300 livres, while the wife holds 1000 livres consisting of both money and effects. Pauline was in other words richer than Leclerc. She declares to after her marriage have returned to the chocolate making business and ”devoted myself entirely to the care of my household and given the example of conjugal love and the domestic virtues which are the basis of love of the homeland.”

March 17 1794 — Pauline joins Leclerc at La Fère (Aisne), where the latter is mobilizing.

April 3 1794 — the Leclerc couple is arrested on orders given by the Committee of General Security. They are taken to Paris and locked up in the Luxembourg prison three days later.

4 July 1794 — At the Luxembourg prison, Pauline either writes or dictates Précis de la conduite révolutionnaire de dame Pauline Léon, femme Leclerc, which is adressed to the Committee of General Security. It is from this document we learn almost all the details regarding her militant activities and private life. Unfortunately, I’ve not been able to find it published in full.

5 August 1794 — Pauline writes to ”sensible Tallien” and pleads for the cause of ”800 imprisoned people.” One day later she adresses herself to to ”the representatives” and asks them to at least consider a prompt examination of their case. Pauline claims that Leclerc and Pierre-François Réal were imprisoned for having "collected evidence against the accomplices of the tyrant Robespierre who were to have their throats slit." The following day, the two men are brought before the Committee of General Security. Réal is immediately set free, Pauline and Théophile joins him on August 22.

22 July 1804 — Pauline writes the following letter (cited in full within the article Un sans-culotte parisien en l’an XII: François Léon, frère de Pauline Léon (1982) by Michael David Sibalis) to Réal, by now one of those in charge of the general police, asking for the liberation of her younger brother François Paul Mathurin, imprisoned since three and a half months back for having written and published leaflets critical of Napoleon. Through the letter, we learn about some things that have happened in her life during the ten years since the last trace of her:

4 Thermidor [year 12] Monsieur, A month ago I presented a petition to the Grand Judge; at the same time I had the honor of writing to you, to request the release of my brother, named François Léon, imprisoned in the Bicêtre for a bad verse; I would ask for your indulgence, today I appeal to your justice; four months of such harsh detention had to atone for his fault; moreover his friend guilty of the same extravagance, since of two verses, one wrote the first and the other the second, was released; my brother is not more guilty, perhaps he is less; his delicacy did not allow him to justify himself at the expense of his friend; which certainly does not deserve punishment. Based on this, Monsieur, I believe I have the right to ask for his release; and I have the firm confidence that you will grant it to us; if you could still deign to think of his mother, who is old and more punished than him. This poor woman is exhausted trying to help and console him. She who needs help for herself, I am not talking to you about the grief her family is experiencing at the loss of my time (which is precious since it must be used to feed my son and relieve my mother), having, Monsieur, the advantage of having known you, I think you will not disdain these considerations. Salut and respect, Femme Leclerc Teacher (Instritutrice) Rue Jean Robert No. 4

François will be set free and leave Paris, the police having labeled him as a ”pronounced anarchist, difficult to correct.” In his interrogation, held May 2 1804 (it too cited in full within Un sans-culotte parisien en l’an XII…) he reveals that he is a tailor living alone on rue du Vieux Colombier N. 744 and ”very republican.” François’ accomplice Jean Sorret did in his interrogation claim that his friend was ”a pronounced jacobin, as is the rest of his family.”

October 5 1838 — death of Pauline in Bourbon-Vendée, rue de Bordeaux, one week after her seventieth birthday. She had moved there to settle with her sister Marie Reine Antoinette and her family somewhere between 1812 and 1835.

47 notes

·

View notes