#*evolution

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

My professor introduced us to a very niche type of climate proxy in lab today, and now that’s all I can think about.

The lab was about tree rings, and he mentioned the word “pollen” along a list of other commonly proxies used. But pollen???? That’s unnecessarily interesting to me and is eating at my brain. He spent almost an hour talking about it to me after lab bc omg no that’s so cool and I have so many questions

#guys you don’t get it#that can be used to not only trace the paleoclimate#but also the migration of plants#wanna know what follows plants???#animals.#wanna know what I super want to study???#the push and pull of plants and animals through revolution#*evolution#like it will only go back so far on the time scale#but!!!!!!#it’s still part of what I want to do#like doing the edge peices of a puzzle#or the corners

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

“In all timelines, in all possibilities

Only you can show me this.”

#happy 2025 jayvik nation!#jayvik#arcane#arcane jayce#jayce talis#my art#arcane viktor#viktor arcane#jayce x viktor#artists on tumblr#the glorious evolution of jayce and viktor

30K notes

·

View notes

Text

….well, she’s got the spirit!

#sylveon#pokemon gifs#animated gif#pokemon#eeveelution#funny#silly#stupid#tap water#drinking#fairy type#cute#the silly#blep#mlem#eevee evolutions#kalos#pokemon art#atompalace art#she’s so stupiiiii#love her tho I’ve been intending to depict sylveon doing silly cat behaviours#this is popping off on twt btw omg

48K notes

·

View notes

Text

glorious evolution

#arcane#jayvik#arcane s2#jayce talis#viktor arcane#fanart#based on the vitruvian man#shout out to my friend for encouraging me to post this#you know who you are. love you#my favorite part in arcane was when viktor said its evolution time and then evolved all over the place#jayce fuck your hammer#not literally#unless#still dont know how to tag properly#hell yeah

34K notes

·

View notes

Text

hehe they are so happy and freaky and not dead full in my telegram <3 тгк: венька

24K notes

·

View notes

Text

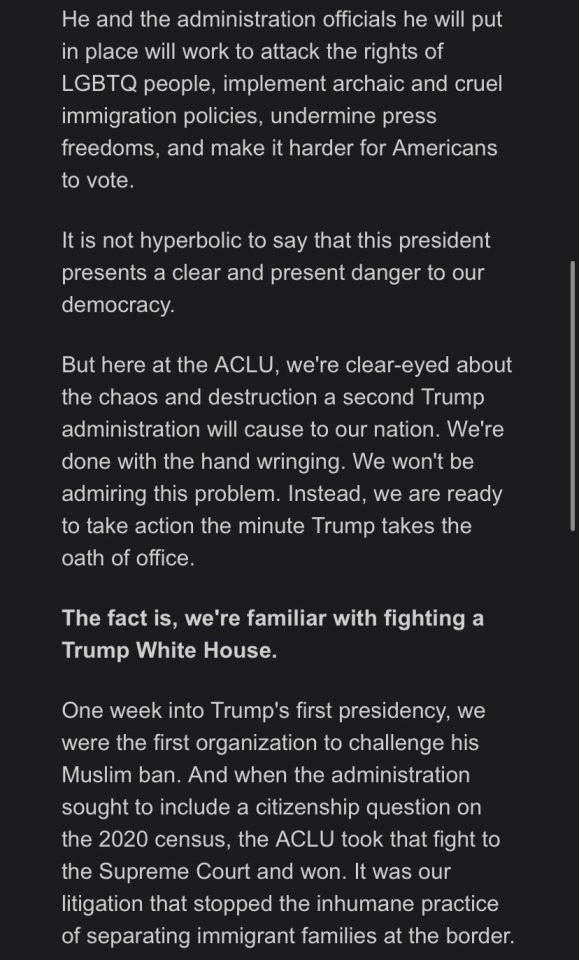

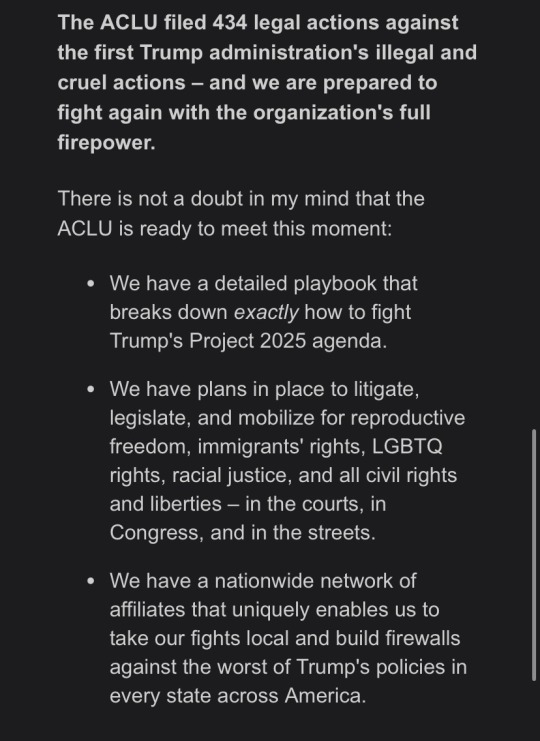

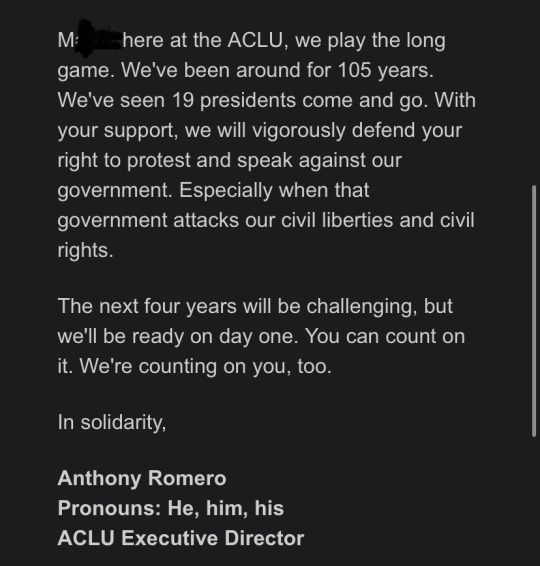

A Pragmatic and surprisingly comforting perspective about the Trump 2nd Presidency from the ACLU

***Apologies if this is how you found out the 2024 election results***

Blacked out part is my name.

I’m not going to let this make me give up. It’s disheartening, and today I will wallow, probably tomorrow too

AND

I will continue to do my part in my community to spread the activism and promote change for the world I want to live in. I want to change the world AND help with the dishes.

And I won’t let an orange pit stain be what stops me from trying to be better.

A link to donate to the ACLU if able and inclined. I know I am

#us politics#donald trump#election 2024#aclu#a promise to myself#how is this comforting you May ask#bc we are not fighting alone or uninformed#we have good and strong groups in our corners defending what we believe in#it’s not over yet#we have to try and pushback#added Alt image descriptions since this is leaving containment#happy to see many engaging with this to either donate time or money or both#really warms the cold heart of mine#wow this broke containment#overall it’s been pretty nice seeing people engaging with it ready to roll up their sleeves and get to work#they did the travel ban right at the beginning of the previous presidency too#also every major civil battle in the last century#brown V board of education- the one that desegregated schools#loving V Virginia- legalized interracial marriage#roe V wade- legalized abortion#United States V Nixon- watergate scandal WHICH LIMITED US PRESIDENTAL POWER#Edwards v. Aguillard- helped allow schools to teach evolution#Planned Parenthood v. Casey- another abortion case#ACLU v. NSA- to stop the NSA spying on wikipedia users#Ingersoll v. Arlene's Flowers- fought to stop LGBTQ discrimination from businesses#Obergefell v. Hodges- case that legalized gay marriage#literally WAY MORE GUYS#so don’t fall into dispair! these are literally one of the good ones!

26K notes

·

View notes

Text

All roads lead to Rome, all lineages evolve to CRAB 🦀🦀

34K notes

·

View notes

Text

Viktor x Jayce - Arcane: League Of Legends - Artist: 6_teh

#arcane#league of legends#glorious evolution#heart of the hex#hexcore#jayce talis#viktor machine herald#jayvik#jayce x viktor#vikjayce#viktor nation#arcane league of legends#viktor arcane#arcane jayce#hextech#arcane meta#arcane fandom#jayce league of legends#jayce lol#viktor league of legends#viktor lol#viktor fanart#arcane season 2

13K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Lancetfish is a species that looks like it comes straight out of a realistic fantasy world building project.

#speculative biology#speculative ecology#speculative evolution#speculative zoology#traditional art#traditional sketch#spectember#specposium#paleontology#fanart#paleo meme#paleo art#paleontologist#paleostream#paleobird#paleomedia#paleoblr#paleoillustration#paleoart#worldbuilding#world#fishing#world building#fantasy#realistic fantasy#fish#lancet fish#lancetfish

70K notes

·

View notes

Text

Am I late to the party ?

#arcane#arcane season 2#fanart#meme#ah yes. me. my girlfriend.#jayvik#jayce x viktor#meljayvik#glorious evolution#the machine herald#I love this meme#haven't see this one already so here's my brick in our nation#meme redraw

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

I love you speculative biology. I love you worldbuilding projects. I love you creature design. I love you fantasy biology. I love you speculative evolution. I love you science fiction.

#speculative biology#speculative evolution#creature design#scifi#rosie rambles#all tomorrows#the birrin#subnautica#humanity lost#the epic of serina

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

Grounded Flight

2024, decolorant screenprint on quilted cotton

20K notes

·

View notes

Text

You come across a family on your hike

28K notes

·

View notes

Text

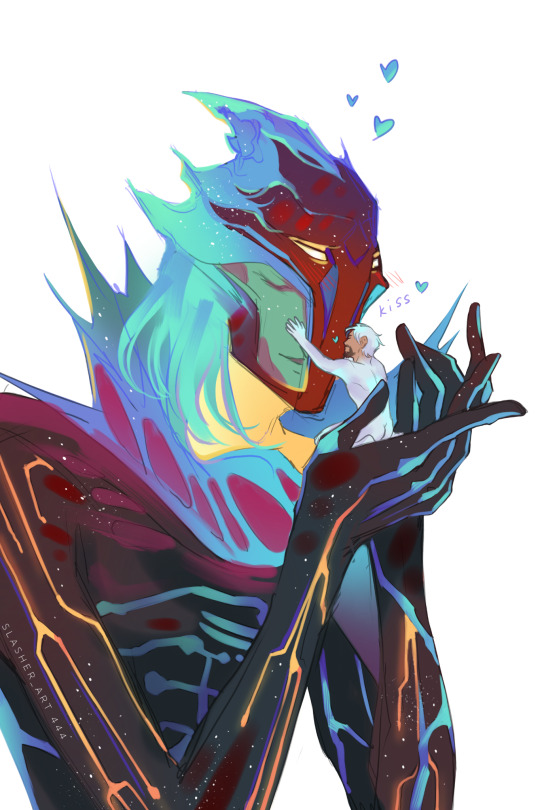

I love the dynamic of *smol guy and his big chthonic boyfriend* so much. 🥺💖

#them#smol guy and his big chthonic boyfriend#jayvik#arcane#jayvik fanart#arcane 2#arcane fanart#arcane 2 fanart#jayvik art#jayce talis#arcane jayce#jayce x viktor#arcane viktor#viktor arcane#viktor league of legends#jayce league of legends#league of leguends#riot games#artists on tumblr#glorious evolution#the machine herald

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

you're going about your normal day when, suddenly, surprise! you've been pokémon mystery dungeon'd!

unfortunately, due to budget cuts, the pokémon assigning quiz has been canceled. instead, you must spin THE WHEEL, assigning you a random, unevolved, non-legendary and non-mythical pokémon. you must now go on some sort of world-saving adventure as this pokémon. good luck!

tell me in the tags what you rolled, and how you feel about it - for bonus points, you can spin the wheel again for (or just take your pick of) a pokémon to be your partner.

bonus rules:

you're not shiny unless the wheel tells you you're shiny

take your pick of regional forms and evolutions (for example, if you roll vulpix, it's up to you whether that means normal or alolan vulpix)

apply whatever logic you like with regards to gender

have fun and be yourself!

#pokemon#pkmn#pokemon mystery dungeon#pmd#tag games#someone might've done this concept already but i had a worm in my brain you know.#i thought itd be fun to list all the unevolved pokemon... now i know there's only around 400 evolution lines total!#.. not counting mythicals legendaries ultra beasts or paradoxes#by the way! alongside the shiny result there are two other bonus results: an obligatory pikachu and... a surprise!!!#finally feel free to let me know if i misspelled something or accidentally included an evolved mon (other than pikachu)#sorry long tags ha 😅 i'm done now#tw flashing#<- 2025 edit: meant to add this a while back whoops! the wheel spinning is a bit flashy. stay safe!

34K notes

·

View notes