#“this appears to be an Aztec Quetzalcoatl”

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

white people shut the everloving fuck up about what appropriating peoples culture means challenge and just enjoy your goddamn sparkle dragons

#the road to hell is paved with good intentions#do not be offended for us#“this appears to be an Aztec Quetzalcoatl”#you idiot there were no people who even called themselves that if you want to get to the brass tracks of it#and its not a fucking lakota headress#have you ever seen a peacock or a turkey#yes this is about flight rising#shut uP shut UP and just LISTEN i promise it doesnt fucking hurt#you do not know enough about what you are “defending” to correct people!!#We do not actually want you correcting people for us#“eurocentric misconception”#the feathered serpent is OLDER than the temples its EVERYWHERE and its been depicted a thousand ways#shut up#fucking come back to sparkle dragon game and this immediately happens#its like that fucking white idiot who wanted to lecture about appropriate biracial representation#cloWN

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ouroboros Ouroboros meaning and origin The ouroboros symbol, often depicted as a snake eating its tail to form a circle, is one of the oldest and most recurring motifs in the mythology and iconography of various cultures around the world. Next, I will tell you about some of the most notable origins and meanings of ouroboros in different cultures: Ancient Egypt: One of the first known records of the ouroboros comes from ancient Egypt, where it was associated with the serpent Uraeus, a protective deity represented as a cobra. Ouroboros was related to the cycle of life, death and renewal, and was often found in amulets and funerary jewelry. It was also linked to the idea of eternity and the unity of time. Ancient Greece: In Greek mythology, the ouroboros is sometimes associated with the serpent Ladon, who guarded the Garden of the Hesperides and is often depicted as a serpent eating its own tail. This symbol is related to the idea of constant regeneration and the infinite cycle of nature. India: In Hindu tradition, the ouroboros is found in the image of the Ouroboros Ananta Shesha, the cosmic serpent that supports the god Vishnu as he floats in the cosmic ocean. This snake represents eternal time and the infinite cycle of creation and destruction in the universe. Alchemy: During the Middle Ages and Renaissance, the ouroboros became an important symbol in alchemy. It represented the union of opposites, such as the masculine principle (the Sun) and the feminine principle (the Moon), and symbolized transmutation and the search for the philosopher's stone, which conferred immortality. Other cultures: The ouroboros also appears in Chinese mythology, where it is known as the "Jade Dragon." Additionally, it is found in Mesoamerican cultures such as the Aztec, where it is associated with the feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl. The general meaning of the ouroboros is the idea of an eternal cycle, renewal, the unity of opposites and eternity. It is also interpreted as a symbol of self-reflection and self-transcendence, where the individual seeks understanding and wisdom by exploring their own limitations and potentials. Overall, the paradox of the ouroboros challenges our conventional understanding of time, renewal, and the relationship between opposites. It invites contemplation and reflection on the interconnectedness of all things and the complex nature of existence. The paradox inherent in the symbol has made it a powerful and enduring motif in various cultures and philosophical traditions. In summary, the ouroboros is an ancient and universal symbol that has evolved throughout human history and culture, representing profound concepts related to the cyclical nature of life and the pursuit of wisdom and transcendence. His legacy endures to this day as a reminder of the richness and depth of human symbolic thought.

629 notes

·

View notes

Note

Stop me if you've answered these kinds of questions before:

I loved reading the graphic novel adaptation of American Gods. I was wondering if there were any particular reasons why there were no indigenous spiritual figures that to make an appearance in the story, like Glooskap or Nanabozho from Wabanaki/Anishinaabe legends, or Mexican deities like the Aztec Quetzalcoatl, or the Mayan Kinich Ahau?

Was it due to a lack of available research material at the time of writing? Concerns about presentation? Time constraints? Did they just not fit into the story you were trying to tell?

I hope this doesn't come off as leading or accusative, it's not meant to be. I was just curious. I would love to hear your perspective on this, as the author.

I think you may have missed Wisakedjak, who is there and vital to the story.

There are a number of Mexican and Mayan deities in the book, but they are described and not named.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Aztec Pantheon drawn in Hades style.

Cōātlīcue

Cōātlīcue, or "She who wears skirts made of snakes" is the mother Goddess of fertility, patroness of life and death, and rebirth. She is said to birth the stars known by the Mexica as the Centzonhuītznāhua, the moon goddess Coyolxāuhqui, and the Aztec sun god Huītzilōpōchtli.

Tezcatlipoca

Tezcatlipoca is the Aztec God of the Night, Storms, and Obsidian. He wields his Obsidian Mirror (his name meaning Smoking Mirror) and is the 'Tezcatlipoca' (A title for the Four Central Gods of Aztec Culture) of the North. He is said to have a youthful appearance with skin dark like obsidian and yellow striped paint across his face. His rival is Quetzalcōātl, the Tezcatlipoca of the West and fellow Creator God.

Mictlantecutli

Mictlāntēcutli is the Aztec God of the underworld. Like Hades, who styles his realm after himself, Mictlāntēcutli is known as the Lord of Mictlān and is associated with death, decay and ritual cannibalism. As Tōnatiuh, the God of the Sun is associated with light, Mictlāntēcutli is associated with darkness, with animals like Owls, Bats, and Spiders being attributed to him. As an antagonist in the Tale of Creation, Mictlāntēcutli was a major obstacle against Quetzalcōātl who escaped the underworld with bones he used to create the first humans.

Xipe Totec

Xipe Totec is the Aztec God of Flayed Rebirth, Spring, and Agriculture (among many other aspects). He was said to have flayed his own fetid skin to make way for a new body, like the changing seasons, and the way maize (corn) lose their layers. As one of the Four Tezcatlipocas (the others being Quetzalcoatl (Feathered Serpent), Huitzilopochtli (Left-Handed Hummingbird) and Tezcatlipoca (Smoking Mirror) himself) Xipe Totec (Our Lord the Flayed One) claims dominion over the East.

Xochipilli

Xōchipilli is the Aztec god of art, music, poetry, flowers, and games. Similar to the Greek God Dionysus, Xōchipilli (Flower Prince) is associated with celebration and a bit of debauchery. Various psychoactive plants including Tobacco, mushrooms, and a variety of psychedelic flowers are taken during his festivals or in prayer to him. Xōchipilli is also associated with male sex work and homosexuality. His female counterpart/sister is Xōchiquetzal, who has a similar portfolio, and was associated with love beauty and fertility.

#hades fanart#hades game#hades supergiant#artists on tumblr#digital art#hades#hades 2#supergiant hades#hades art#oc art

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tyneen as Cipactli

Cipactli, literally translated as “alligator”, is a gigantic sea monster that appears in the Aztec creation myth. From her body the four Tezcatlipocas made the earth, the thirteen heavens, and the underworld.

“Cipactli” is the first day symbol on the Aztec calendar. Here are a few illustrations of her in different codices. In Codex Magliabechiano there is a section of the calendar day signs in detail, where the Cipactli day sign looks very similar to Tyneen’s design (page 11)

The bright colors, the forked tongue, the parting of the teeth, the spikes on her head, even the goofy look of the eyes.

I'm sure this could be a subtle reference to Cipactli as well. In a version of this myth, Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca are the ones who take care of the beast in order to create the world. Tezcatlipoca lured her out into the surface using his foot as bait. As a result, the reptile bit Tezcatlipoca’s foot off, and that’s why he’s usually seen with a mirror or a bone where his foot should be.

Tyneen didn't bite anyone's limb off (that we know of lol) but she did cut off her own hand to replace it with a more functional robot hand

Cipactli is also considered an insatiable beast. Everything the four brothers created, she would eat. It's possible that they wrote Tyneen's personality based on this. She's never satisfied, she always wants more. Like she wasn't satisfied with Kara's unfinished autograph for example

As an additional note, Cipactli lived in the primordial ocean, when there wasn't any land yet. Tyneen is a pirate, associated with the ocean.

There's another version of this myth where this earth monster is called Tlaltecuhtli, and he/she has a different iconography, and they made him a different character, Maybach. But it's gonna be a hot minute until we get to that

List

#monkey wrench#monkey wrench theory#tyneen#five sun theory#aztec mythology#cipactli#this one may be short but I have things to say about the cats next

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

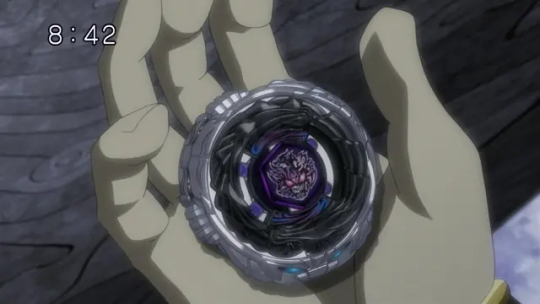

The Cosmic Names of MFB Beys.

In MFB, Beys are named after constellations like Pegasus and Leone and sometimes celestial bodies such as Jade Jupiter. However, there are some cases that do not seem as straightforward, and even some Beys that can find multiple origins for their names. I decided to take a look at them.

Vulcan Horuseus

Horuseus represents Horus, the god of the sky, and as a result, he encompasses both the sun and the moon as his eyes. So, he has a connection to Earth's satellite, the moon and with the sun, our star.

There is also an asteroid named after Horus: 1924 Horus.

The Fusion Wheel also plays a role, as Vulcan references a hypothetical planet closer to the sun than even Mercury.

Hades Kerbecs

Kerbecs actually refers to a constellation, Cerberus, which is now an integral part of the Hercules constellation.

However, like Horuseus, there is also an asteroid named after the three-headed dog: 1865 Cerberus.

Similarly, a moon of Pluto is named after the god’s loyal companion as well—Kerberos.

Mercury Anubius

Anubius is the Bey of the Legendary Blader of Mercury, Yuki, and as such, he represents the planet with his Fusion Wheel of the same name.

Anubis is the god of mummification and guided souls to the afterlife, a task also taken by Hermes, with whom he was associated with. Hermes is considered the Greek equivalent of the Roman Mercury.

Anubis is depicted as a man with a jackal head. This canine form can create a link with constellations such as Canis Minor, and some scholars claim there was a connection between the two for the ancient Egyptians. Some also say that Anubis was connected with Sirius, the brightest star in the sky, which is part of Canis Major. However, some of these claims are more modern interpretations. Regardless, I can see MFB using that interpretation.

Anubis also gave its name to an asteroid (1912 Anubis).

Forbidden Ionis

Ionis is depicted as a heifer and, as such, can be associated with the bull constellation, much like Dark Bull—they even share a similar color scheme.

However, it can also and mainly be associated with Jupiter’s satellite Io, named after one of the god’s mistresses, who was changed into a cow.

Omega Dragonis

Omega Dragonis represents a dragon and, as such, can be associated with the Draco constellation, much like L-Drago.

In addition, the complete name Omega Dragonis can be seen as a pun, since one of the stars in the Draco constellation is named Omega Draconis.

Death Quetzalcoatl

Quetzalcoatl represents the Aztec god of the same name, who often took the appearance of a feathered snake, just like in the anime. As a result, it can be associated with the Serpens constellation.

There is also 1915 Quetzálcoatl, an asteroid named after the Aztec god.

But more importantly, in Aztec mythology, Quetzalcoatl is often associated with the morning star, aka Venus.

Diablo Nemesis

As many of you probably know, Nemesis was the name given to a hypothetical star (a red or brown dwarf) once speculated to orbit around the Sun, but it doesn't actually exist.

However, Nemesis does have an asteroid with the same name: 128 Nemesis.

Additional Beys

Here are some Beys that didn’t make it into the anime but seem to have names disconnected from the overall theme:

Divine Chimera

I couldn’t find anything concrete for Chimera, other than an asteroid named 623 Chimaera.

I think the reason why Kakeru’s Bey seems a little far from the classic constellation naming theme is because it was the result of the "CoroCoro Design a Beyblade Contest," with bladers creating their own designs.

Nightmare Rex

There are asteroids named after dinosaurs, notably 9951 Tyrannosaurus.

The name dinosaur ("terrible lizard") and Tyrannosaurus ("tyrant lizard") both derive from the greek word for lizard, meaning that they could represent Lacerta (the lizard constellation). It wouldn’t be the first time that a constellation ends up with a Bey having a different design—like Gill, which represents Carina Keel as the motif but has the spirit of a sea monster instead.

Bakuushin Susanow

Bakuushin Susanow was honestly more complicated. However, it is noteworthy that he is the god of the sea and storms and the brother of Amaterasu, the goddess of the sun, and Tsukuyomi, the god of the moon. One day, he went on such a rampage that it caused Amaterasu to hide in a cave until the other gods convinced her to come out. This myth is believed to be a representation of a solar eclipse, with Susanow being the cause. Some modern interpretations suggest that Susanoo represents solar eclipses (in this myth), though this is not a central aspect of his traditional Shinto mythology. Interestingly, Takara Tomy released an all-black version of this Bey called Lunar Eclipse.

There is also an asteroid named after him: 10604 Susanoo.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kukulkan (Quetzalcoatl): Feathered Serpent And Mighty Snake God

Known under a number of different names, Kukulkan, the Feathered Serpent was one of the most important gods in Mesoamerica.

The Aztecs called him Quetzalcoatl and the ancient Maya referred to him as Kukulkan. The K’iche’ group of Maya named him Gukumatz.

Was this mighty snake deity a real historical person?

It is not easy to trace the ancient history of Kukulkan. Like all of the feathered serpent gods in Mesoamerican cultures, Kukulkan is thought to have originated in Olmec mythology and we still know very little about the mysterious Olmec civilization.

The true identity of the god Kukulkan becomes an even greater problem due to the confusing references to a man who bore the name of the Mayan god. Because of this, the distinction between the two has become blurred.

Around the 10th century, a priest or ruler appeared in Chichen Itza, a sacred site that was one of the greatest Mayan centers of the Yucatán peninsula, Mexico where we also find El Castillo, also known as the Temple of Kukulkan.

Kukulkan has his origins among the Maya of the Classic Period, (200 AD to 1000) when he was known as Waxaklahun Ubah Kan, the War Serpent.

Maya writers of the 16th century describe Kukulkan as a real historical person, but the earlier 9th-century texts at Chichen Itza never identified him as human and artistic representations depicted him as a Vision Serpent entwined around the figures of nobles.

According to ancient Maya beliefs, Kukulkan - popularly known as the Feathered Serpent - was the god of the wind, sky, and the Sun. He was a supreme leader of the gods, depicted, just like Quetzalcoatl. Kukulkan gave mankind his learning and laws. He was merciful and kind, but he could also change his nature and inflict great punishment and suffering on humans.

According to Maya legend, the Maya were visited by a robed Caucasian man with blond hair, blue eyes, and a beard who taught the Maya about agriculture, medicine, mathematics, and astronomy. This being was Kukulkan – the Feathered Serpent.

Kukulcan warned the Maya of another bearded white man who would not only conquer the indigenous people of Central America but would also enforce a new religion upon them before he was to return. Despite the warning, the Maya mistakenly welcomed the invading Cortes as Quetzalcoatl.

The cult of Kukulkan spread as far as the Guatemalan Highlands, where Postclassic feathered serpent sculptures are found with open mouths from which protrude the heads of human warriors.

Hundreds of North and South American Indian and South Pacific legends tell of a white-skinned, bearded lord who traveled among the many tribes to bring peace about 2,000 years ago. This spiritual hero was best known as Quetzalcoatl.

Some of his many other names were:

Kate-Zahl (Toltec)

Kul-kul-kan (Maya)

Tah-co-mah (NW America)

Waicomak (Dakota)

Wakea (Cheyenne, Hawaiian and Polynesian)

Waikano (Orinoco)

Hurakan

the Mighty Mexico

E-See-Co-Wah (Lord of Wind and Water)

Chee-Zoos

the Dawn God (Puan, Mississippi)

Hea-Wah-Sah (Seneca),

Taiowa, Ahunt Azoma

E-See-Cotl (New Guinea)

Itza-Matul (Yucatan)

Zac-Mutul (Mayan)

Wakon-Tah (Navajo)

Wakona (Algonquin)

Kukulkan emerged from the ocean, and disappeared in it afterward. Before he left, he promised that he will return one day in the future, but he never revealed when…

Image: Kukulkan (Quetzalcoatl) Mahaboka

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heroes & Villains The DC Animated Universe - Paper Cut-Out Portraits and Profiles

Justice League Supplemental - Aztek & Starman

The Q Foundation, a secret society of religious outcasts and renegade scientists foretold the return of the Aztec primary god, Quetzalcoatl and the final battle between him and his brother Tezcatlipoca. In preparation, the Foundation created war suits to be worn by specially trained operatives. Uno was the latest to take on the Aztek mantle and relocated to Vanity City under the alias of Dr. Curt Falconer.Powered by fourth dimensional energies, the Aztek war suit is a conglomeration of magic and technology giving its bearer an array of powers such as super strength, super speed, super hearing, telescopic vision, x-ray vision, infrared vision, invisibility and flight.

Aztek was recruited into the Justice League when the team expanded its roster in the wake of the Thanagarian Invasion. As a member of the League, Aztek aided in fighting Mordru, the Dark Heart, and the Ultimen.

Born into the ruling monarchy of the alien planet of Throneworld, Price Gavyn chose to roam the cosmos in search of adventure so that he might learn humility and valor. On earth he came to be known as Starman and possessed the abilities to absorb and redirect solar radiation. He was asked to join the Justice Lesgue when the team expanded its ranks and he gladly accepted.

Starman participated in the battle against the Darkheart as well as the defense of earth from the invading armies of Darksied.

The two heroes both first appeared in the debut episode of the first season of Justice League Unlimited, ‘Initiation.’

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interview with Sofia Alexander - Onyx Equinox Season 2 Revelations

So, as indicative of the title, recently, Ryuyin Ovi of Crunchyroll Latin America sat down with Onyx Equinox creator and executive producer Sofia Alexander for a juicy, THREE-HOUR LONG INTERVIEW regarding "what would have been" during season 2 of the series, as well as other behind the scenes tidbits. The interview was entirely in Spanish (but Sofia hopes to do another one someday in English), and also starred Cecelia Guerrero (LA voice of Izel), Amanda Hinojosa (LA voice of Xanastaku), and Alessia Becerril (LA voice of Zyanya). Below are a multitude of bullets containing the big points revealed during the live stream. Sit back, [try to] relax, and enjoy!

• Color was a showcase of symbolism throughout the series. Mexican pink represented Olmec technology, turquoise represented the Underworld, and red was indicative of the mortal realm. There was no consensus on a single meaning for yellow. For example, Zyanya's yellow was that of the cempaxúchitl, honoring her family and the people [of Daani Baán] who died and are trapped in the Underworld.

• Huitzilopochtli already made his appearance in season 1 as the possessed Daani Baán elder who's body was consumed by light, and who's heartbeat increased the longer he was possessed. As for season 2, Sofia played with the idea of him being the youngest of the principal Gods. His King form was going to be like a child, not as young as Izel but more like a shonen protagonist. He was going to be very smart and impulsive, like “I’m more open to supporting,” with a more explosive vibe.

• Quetzalcoatl had a plan for losing the bet in season 1, essentially giving a vibe of "Okay, I lost, but I actually won."

• As indicated at the very last scene of season 1, Nelli is the heron emissary of Quetzalcoatl we see on occasion. Before Izel was going to be the potential sacrifice at Uxmal, Nelli prayed to Quetzalcoatl, telling him she would give her life for her brother; in exchange, he would take care of Izel. That brotherly power, the love of a sister for her brother, is what Quetzalcoatl sees as valuable in humanity, as something that must be protected. With Neli's request, and already being aware of the other Gods' displeasure with humans, he began to move pieces in a game of 4D chess.

• Nelli WAS going to return in season 2. How exactly, and in what form, is unknown to the audience.

• "Yunzel" is canon, and was going to be fully established in season 2 🏳️🌈

• Izel and Nelli are children of an eagle warrior and a woman from Tenochtitlan. They had to flee the city because their father was accused of being a traitor, as someone tried to kill the Tlatoani, and used him as a scapegoat. The children went ahead to escape, but got lost in the jungle, eventually being saved by Maak, who was a pochteca (professional, long-distance traveling merchant in the Aztec Empire). In season 2, Izel was going to find his parents alive.

• Season 2 would have also focused more on Xanastaku. Her red wings indicate that her power came from a human sacrifice. Akapun (the former high priest, who was her teacher), physical abused her. The Gods in the world of Onyx give people like the flyers in Tajín their powers. Akapun's mental state was declining, and that connection was affecting him. Xanastaku was going to be the high priestess, but Akapun didn't want to give her that responsibility yet, as she was too young. Xanastaku insisted on being ready, and fought with Akapun, resulting in the former nearly killing her, and the latter killing him in self-defense, and gaining his power. There was the idea that Akapun would have survived and search for her [after she flees Tajín], or that she has to return to Tajín to solve something that came up.

• A character named Ollin (meaning "movement" in Nahuatl) was going to be introduced, who would help Xanastaku with regard to astronomy. At first he was going to be Xanastaku's twin. Before that, the idea of twins wasn't even thought of for the series. Originally, there would have been a character named Steia (sp.), who eventually became K'in. Then, this character became the twins Xanastaku and Ollin, who was previously going to be called Citlali (as for who Citlali was the original name for remains unclassified at the moment), and in the end, only Xanastaku was used.

• Xanastaku wants to save Zyanya from her curse given by Mictlantecuhtli. The reason Zyanya used her obsidian amulet on Xanastaku after the latter absorbed a dangerously HUGE amount of energy from Mictecacihuatl during the final episode's climatic battle was to save her from being destroyed by the power that ultimately killed Akapun. Xanastaku's biggest plot was going to be related to Zyanya.

• Coyolxauhqui was also going to be introduced in season 2, as an ally of Izel. This alliance is not because she's inherently good, but because she greatly admires Mictecacihuatl, and doesn't like her brother, Huitzilopochtli (if you know the mythology, can you blame her?)

• Besides Coyolxauhqui and Huitzilopochtli appearing, the only other God planned to make a proper appearance was Xipe Totec

• If Quetzalcoatl had chosen someone other than Izel as his champion, it would have been Zyanya.

• K'in and Yun are not actually full-blooded Mayan, but Purépecha! One of their parents was Mayan, while the other was Purépecha. It was thought that by being twins, they ran the risk of being sacrificed. Taking into account the date they were born, they were destined to be Ulama players. Maak, their adoptive caretaker, and the former brief caretaker of Izel and Nelli, was a very famous former Ulama player. There was no consideration of introducing the twins' parents, although there was the idea that K'in would have wanted to meet them.

• K'in's trauma of being alone and away from Yun: The twins' souls are very tied together, mostly because of their symbolism, and the destiny that unites them in order to help Izel. Sofia wanted to play with the idea of the difference in needs between them--K'in needs Yun very differently than Yun needs K'in. Another thing to consider is that K'in, because of his personality, needs people, his brother, more than he could admit.

• Plans with Yaotl: He was going to return. Mictecacihuatl brings him back to life (as a jaguar), but he is more connected to the Underworld than to the mortal world. He seeks his purpose, and wants to teach Izel how to be a warrior, and he also wants to protect him as he feels he should have done. He was going to have to make a journey in the Underworld before returning with a physical form, and at the same time, feel worthy of protecting Izel. Mictecacihuatl and Yaotl, despite being a couple when the latter was human, were not going to be endgame in season 2.

• Considering all of the events that happened in season 1 thanks to her, Mictecacihuatl feels a very strong obligation to humanity. She was going to be a kind of adoptive mother to Izel.

• Izel and Yaotl reunion: Taking place in Tenochtitlan, it was going to be emotional and full of drama. Yaotl doesn't trust the Tlatoani, even though Izel admires him greatly.

• There was going to be a time skip of several years, and Izel (now aged around 17-19) would be part of the Tlatoani's elite guard in Tenochtitlan. Rather than end the world in the blink of an eye, Tezcalipoca was also going to partake in some 4D chess. The Tlatoanis Sofia was going to use are fictional, but their names would come from historical, real-life figures (e.g., Huitzilíhuitl, Itzcoatl). The Tlatoani that we see at the end of season 1 was already working with Tezcatlipoca, and not only did he already know everything about Izel, but he even knew of everything that was going to transpire before the series officially started, or before Izel was even born! This Tlatoani (Huitzilíhuitl) tried to kill his brother (Iztcoatl); Izel's father protected the latter (likely the event that led to Nelli and Izel fleeing Tenochtitlan).

• As mentioned previously, Izel admires Huitzilíhuitl, as he was one of the only ones who "believed" in all of the events that transpired in season 1, the end of the world, etc. Izel felt safe, with the advantage of being in such a great city filled with warriors, not knowing that they were "in the nest of snakes." His story was going to lead him to Itztcoatl, and bring him back as the true Tlatoani.

• Graphic novel? Art book? Other products?: A graphic novel was planned, but it requires time and money, which is currently unavailable. Sony still has the rights to Onyx, and it is not known when they will be able to release any additional merchandise. The soundtrack, however WILL be released on Spotify by Gustavo Farias!

• The outcome for Tezcatlipoca: Shocker--Quetzalcoatl is the main antagonist, despite wanting to "free humanity" from the wrath of the Gods! His main goal was for Izel to challenge the Gods, and for him to somehow use his power in exchange for sacrificing his life. The Olmecs were going to come in and be used with that power to face Tezcatlipoca. Quetzalcoatl is... chaotic, like "Okay, we did our (the humans) plans and that's it, they don't need us anymore, not even me." Tezcatlipoca was going to be defeated in a tragic and sad way. He feels betrayed by his brother, and doesn't want to be forgotten. Both would eventually be destroyed by humanity, and the only survivor would be Mictecacihuatl!

• Onyx was planned to have three seasons, and a movie which focused on the creation of the world à la the myth of Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcoatl vs. Cipactli.

• Four of the Olmec mechs were going to be used at some point (Yeah! Robot fight!)

• The outcome for Xolotl: At some point, Meque would become self-aware. He doesn't get angry at Quetzalcoatl, and he was going to have a "mega axolotl form", albeit with a smaller role. (MY BOY!!! 🩷)

• Was there any chaos in Mictlan (the Underworld) after Mictlantecuhtli died: No. Mictecacihuatl was already prepared to have the control.

• Quetzalcoatl was interested in Izel searching for Itztcoatl. He was going to give Izel a feather, and whoever has the twin feather is the true Tlatoani of Tenochtitlan. In order to fight the Gods, you need an alliance with the people of the Aztec Empire, and in order to have said alliance, you need to bring the true Tlatoani back to Tenochtitlan.

• The final battle would have been in Teotihuacan

• Izel was going to need help from Yaotl to be able to use the power of a God. Quetzalcoatl was going to die before the final battle, in a confrontation with Izel. This is how Quetzalcoatl could give Izel his power.

• The idea of Izel wearing green/turquoise is a nod to the Zelda games.

• Who tells the story at the end of the series?: There was the idea that Mictecacihuatl would tell Izel's story, although it was not confirmed.

• Sofia designed Mictecacihuatl with María Félix in mind

• How was K'in going to react to Yunzel's relationship?: First of all, K'in and Yun already had some friction. Starting with the time when Izel pushed Yun and broke his leg, even though it eventually got healed, it was never the same again. Yun still feels [physical] pain if he plays a lot. In fact, Yun never wanted to be an Ulama player, but rather, a diplomat. He took on the Ulama playing more for K'in. As for his reaction to Yunzel, K'in would be somewhat jealous, and he would feel that Izel would distract Yun from his goals.

• Speaking of K'in, he was going to have a romance with the princess of Tenochtitlan.

• Yunzel's first kiss was going to be "very serene, intimate, romantic. It wasn't that it happened soon, but it took years to consolidate itself." (Awwww!)

• Sofia was thinking about the idea of sacrificing K'in. She felt that it would be beautiful if he would give his life for Yuns happiness, but Anna (Sofia's wife) convinced her not to. At some point, the mystical Olmec ball the twins used throughout season 1 would have been destroyed. Sofia's idea was that K'in's head was going to be the new ball (YIKES!)

• Why doesn't Mictlantecuthli have a "human form"?: He never felt an affinity to humanity to present himself in a way that was pleasing to mortal eyes. He's not an evil being, he's a being from the Underworld.

• The end of Izel and his team: A happy ending was intended. Zyanya would return to being human. She wanted to continue being a warrior, but after all of the events of the series, she seeks a quieter life. She will always have a strong bond with the Underworld (Or rather, all of them, in some way). K'in was going to end up with the Tenochca princess.

• With regard to romantic relationships, Xanastaku is compared to Frieren.

And there you have it, folks! BIG shout-out to @voyagercocuyo3 for translating all of the content into English (because I only took a year's worth of Spanish in college... hahaohwell!) As always, if anything else comes up, you'll be in the know through me, whether here on Tumblr, or on the Onyx Equinox Discord server!

#onyx equinox#long post#behind the scenes#signal boost#izel#yun#k'in#nelli#xanastaku#zyanya#yaotl#quetzalcoatl#tezcatlipoca#mictecacihuatl#mictlantecuhtli

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

A little something I had on the backburner since December. As you guys know, The Casagrandes Movie was teased early last month, and it showed Ronnie Anne and a unnamed new character in a Mayan (or Aztec?) temple.

Naturally I was inspired to draw said character who, according to the rumormill, is named Punguari. But it did get me thinking, The Loud House movie had some fantastical elements in it, most prominently, the Loch Loud Dragon. So would it be a stretch to imagine that a mythical creature would appear in the Casagrandes Movie as well?

Well, that's the gist of this artwork: Ronnie Anne and Punguari encountering a Quetzalcoatl with the later defending the former with her magic. That's right, I'm willing to bet that the new girl is probably gonna have powers of some kind.

Anyway, this is just speculation on my part, and we won't know until a trailer of some kind is revealed. Watch as this post ages poorly. lol

And yes, I'll be making a bingo card just like the last movie.

#Ronnie Anne Santiago#Ronnie Anne#Punguari#The Casagrandes Movie#The Casagrandes#The Loud House#Artist On Tumblr#Digital Art#My Art#RaishaGS

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Xiuhtecuhtli - Day 87

Race: Yoma

Alignment: Neutral-Law

August 6th, 2024

Fire is a fact of life for many cultures around the globe- a source of heat and warmth may become a source of life in the coldest nights, and flame is needed to cook away the imperfections of food, per instance. This, naturally, would lead to the reverence of fire being a common idea in many old-world religions and traditions, as its importance cannot go understated. This was an especially important fact in the Mesoamericas, however, as food without fire was rare, and the arid climates made flames spread fast- it was as revered as it was feared. This, predictably, led to the lack of understanding regarding fire transforming into, what else, but a representation of that fire itself, as unpredictable as it was important. This deity, at least to the Aztecs, took the form of today's Demon of the Day: Xiuhtecuhtli, the Turquoise Lord.

Strangely in contrast to his role as a god of fire, Xiuhtecuhtli was a rather down-to-earth deity, though one filled with youthful vigor. This was likely due to the fact that he represented more than just fire, however- he represented several important aspects of light itself, such as the daytime, warmth, the hearth, the afterlife, volcanoes, and he was referred to with many names as well- Cuezaltzin and Ixcozauhqui, per instance. While typically portrayed as a young god, ironically he's one of the oldest gods in the Pantheon, typically portrayed alongside and identified with the elder god of fire Huehueteotl, one of the eldest gods in the Aztec pantheon.

Xiuhtecuhtli was a rather important god, though not one counted among the commonly cited main four of Huitzilopochtli, Tonatiuh, Tlaloc, and Quetzalcoatl. However, this doesn't make his role in many stories irrelevant, as he was still a figure who held great importance to the day-to-day life of many Aztecs. After all, as the creator of flame and light, he also was commonly cited as the creator of none other than life itself, though this appears to be rather contested- it may have been Huehueteotl who did so, and interpretations may change based on if one conflates Xiuhtecuhtli with Huehueteotl or not. What Xiuhtecuhtli also did, however, was protect human life from its end, and this one is far harder to dispute.

At the end of the Aztec calendar, Xiuhtecuhtli would preside over a great festival known as the New Fire Ceremony to ensure the sun could continue its cycle without being consumed by the darkness. During this festival, held to ensure the successful renewal of the sun (it's a long story), all fires were put out, all idols were cleansed, and a group of priests would reside atop Citlaltepec, waiting for the stars to align. When the stars did, and the Yohualtecuhtli star shone brightly in the middle of the sky, a priest would cut out a sacrifice's heart then set a flame in the now-empty chest cavity of the sacrifice. This is, rather obviously, a part of where the whole perception of sacrifices in Aztec culture came from, though it was far from the only sacrifice focused ritual, but I'm getting ahead of myself. After this fire would be lit, it would be used to relight all fireplaces throughout the city.

This was an incredibly important ritual, and one that Xiuhtecuhtli had reign over to ensure the next part of the Aztec cycle of life. This all points to a great amount of importance itself being placed upon this deity, as well as fire itself, as it was believed this ritual could be used, if successful, to prevent the incursion of monsters from the dark that would slaughter the Aztec people. Far more rituals throughout the culture did appear to be focused around sacrifice, though the Aztecs were far from a simple blood mongering group who killed for the sake of sacrificing. The importance of these rituals, these sacrifices, and the cost of human life actually shows that they had respect for their fellow man. Still, blood sacrifices weren't good, and I hope that isn't controversial, it's just that they were a product of their time.

Xiuhtecuhtli was also commonly represented with the color turquoise, and this ties into his design, oddly enough. In SMT, a great pillar of fire pierces through a turquoise mask to represent the deity, and this is a surprisingly faithful image to his depictions, especially in the form of the mask itself, though it does take some creative liberties. However, this design is fantastic, and I wish I got to see it in 3D. Maybe next game...

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi all -- I'm on vacation this week, and I wanted to share with you some shots of my trip earlier today to Roger Williams Park Zoo to look at their "Dragons & Mythical Creatures" exhibit! This is a special exhibit running until August 11th where they've set up a bunch of simple animatronics of various mythical creatures from around the world around their Wetlands Trail path. The animatronics are a bit goofy, as you can probably see from the above pictures, but they were still fun to look at, and I had a good time going through and looking at them all with my folks. :) In order of their appearance in the photoset above, we have --

-->An alicorn (winged unicorn) right at the entrance

-->A siren by the lake -- they actually had three mermaids, but the other two were the traditional lovely ladies, so I decided to prioritize getting a picture of the one with the goofiest smile XD

-->Your traditional European dragon, who roared with glowing eyes

-->The Aztec god Quetzalcoatl, depicted in feathered serpent form wrapped around a pyramid

-->The Ninki Nanka, a West African beast with the face of a horse, the neck of a giraffe, and the body of a crocodile, which lives in muddy mangroves and according to the Limba people in Sierra Leone, causes thunder and lightning -- as you can see, this one has a horn for extra value

-->An Egyptian Sphinx sporting the traditional Egyptian funerary mask for pharaohs -- honestly, between that technicolor mask and the way it was wiggling its head, it was one of the most off-putting exhibits there

-->A Japanese kappa, a mischievous creature that here appears as a turtle standing upright with a vicious-looking beak and a divot on the top of its head -- I believe that divot is supposed to hold water, and if you can trick them into bowing to you, the water will flow out and they'll lose a lot of their powers

-->A Japanese Kasa-obake, which is an old and neglected umbrella that has picked up a spirit and become a mischievous ghost with a long tongue and a single eye. ...I will admit, I immediately accused it of being a Pokemon. XD

-->A traditional griffin, with the white feathered head, wings, and talons of an eagle and the body of a lion -- I especially like this one because it includes feathered ears as well, something you don't see on a lot of griffins -- but that you do see on the GRYPHON in the original Alice books!

-->A yeti -- who you may recognize as Bumble from the Rankin-Bass stop motion Christmas films, because apparently the park couldn't resist

-->FUCKING CTHULHU. With his head out of proportion to the rest of his body. If you're wondering what the hell he's doing here, Roger Williams Park Zoo is in Providence, Rhode Island, which just so happens to be the birthplace of HP Lovecraft. I guess they felt they had to. XD

#pictures#vacation#zoo#mythical creatures#cthulhu#yeah I'd heard about this on the radio previously#and I wanted to see it#so we went around opening time this morning to check it out#(along with the rest of the zoo as we haven't been in ages#not since before COVID)#it was very silly but fun#I enjoyed seeing all the creatures#Bumble was a hilarious surprise#and then we got near the end of the trail and saw a sign for local legends#which included Cthulhu#and we were like 'amusing but they'd never put him on the--'#'OH MY GOD'#I mean it's Discount Cthulhu with those spindly facial tentacles#but still XD#and I'm sorry but if the kasa-obake has not yet become a Pokemon#Nintendo has clearly missed out#look at it#it deserves to be in a game

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ouroboros

Ouroboros meaning and origin

The ouroboros symbol, often depicted as a snake eating its tail to form a circle, is one of the oldest and most recurring motifs in the mythology and iconography of various cultures around the world. Next, I will tell you about some of the most notable origins and meanings of ouroboros in different cultures:

Ancient Egypt: One of the first known records of the ouroboros comes from ancient Egypt, where it was associated with the serpent Uraeus, a protective deity represented as a cobra. Ouroboros was related to the cycle of life, death and renewal, and was often found in amulets and funerary jewelry. It was also linked to the idea of eternity and the unity of time.

Ancient Greece: In Greek mythology, the ouroboros is sometimes associated with the serpent Ladon, who guarded the Garden of the Hesperides and is often depicted as a serpent eating its own tail. This symbol is related to the idea of constant regeneration and the infinite cycle of nature.

India: In Hindu tradition, the ouroboros is found in the image of the Ouroboros Ananta Shesha, the cosmic serpent that supports the god Vishnu as he floats in the cosmic ocean. This snake represents eternal time and the infinite cycle of creation and destruction in the universe.

Alchemy: During the Middle Ages and Renaissance, the ouroboros became an important symbol in alchemy. It represented the union of opposites, such as the masculine principle (the Sun) and the feminine principle (the Moon), and symbolized transmutation and the search for the philosopher's stone, which conferred immortality.

Other cultures: The ouroboros also appears in Chinese mythology, where it is known as the "Jade Dragon." Additionally, it is found in Mesoamerican cultures such as the Aztec, where it is associated with the feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl.

The general meaning of the ouroboros is the idea of an eternal cycle, renewal, the unity of opposites and eternity. It is also interpreted as a symbol of self-reflection and self-transcendence, where the individual seeks understanding and wisdom by exploring their own limitations and potentials.

Overall, the paradox of the ouroboros challenges our conventional understanding of time, renewal, and the relationship between opposites. It invites contemplation and reflection on the interconnectedness of all things and the complex nature of existence. The paradox inherent in the symbol has made it a powerful and enduring motif in various cultures and philosophical traditions.

In summary, the ouroboros is an ancient and universal symbol that has evolved throughout human history and culture, representing profound concepts related to the cyclical nature of life and the pursuit of wisdom and transcendence. His legacy endures to this day as a reminder of the richness and depth of human symbolic thought.

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

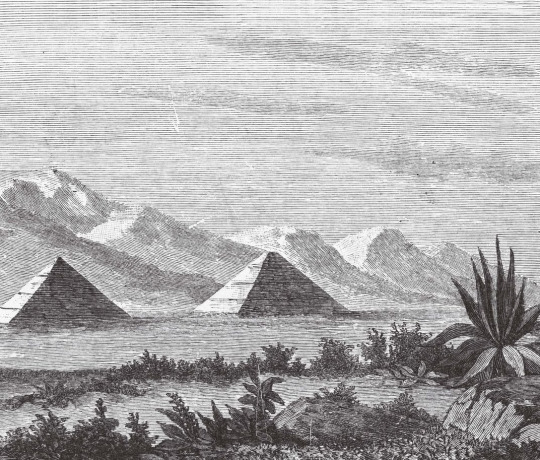

Anthropologist Zelia Nuttall transformed the way we think of ancient Mesoamerica

An illustration of the Aztec calendar stone surrounds a young portrait of anthropologist Zelia Nuttall. “Mrs. Nuttall’s investigations of the Mexican calendar appear to furnish for the first time a satisfactory key,” wrote one leading scholar.Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University

By Merilee Grindle

Author, In the Shadow of Quetzalcoatl: Zelia Nuttall and the Search for Mexico’s Ancient Civilizations

On a bright day early in 1885, Zelia Nuttall was strolling around the ancient ruins of Teotihuacán, the enormous ceremonial site north of Mexico City. Not yet 30, Zelia had a deep interest in the history of Mexico, and now, with her marriage in ruins and her future uncertain, she was on a trip with her mother, Magdalena; her brother George; and her 3-year-old daughter, Nadine, to distract her from her worries.

The site, which covered eight square miles, had once been home to the predecessors of the Aztecs. It included about 2,000 dwellings along with temples, plazas and pyramids where they charted the stars and made offerings to the sun and moon. As Zelia admired the impressive buildings, some shrouded in dirt and vegetation, she reached down and collected a few pieces of pottery from the dusty soil. They were plentiful and easy to find with a few brushes of her hand.

The moment she picked up those artifacts would prove to be pivotal in the life and long career of this trailblazing anthropologist. Over the next 50 years, Zelia’s careful study of artifacts would challenge the way people thought of Mesoamerican history. She was the first to decode the Aztec calendar and identify the purposes of ancient adornments and weapons. She untangled the organization of commercial networks and transcribed ancient songs. She found clues about the ancient Americas all over the world: Once, deep in the stacks of the British Museum, she found an Indigenous pictorial history that predated the Spanish conquest; skilled at interpreting Aztec drawings and symbols, and having taught herself Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs and their predecessors, she was the first to transcribe and translate this and other ancient manuscripts.

A 19th-century engraving of the pyramids of Teotihuacan. The Pyramid of the Sun was restored in 1910, on the centennial of the Mexican War of Independence. Bridgeman Images

She also served as a bridge between the United States and Mexico, living in both countries and working with leading national institutions in each. At a time when many scholars spun elaborate and unfounded theories based on 19th-century views of race, Zelia looked at the evidence and made concrete connections based on scientific observations. By the time she died, in 1933, she had published three books and more than 75 articles.

Yet during her lifetime, she was sometimes called an antiquarian, a folklorist or a “lady scientist.” When she died, scholarly journals and some newspapers ran notices and obituaries. After that, she largely passed from the public’s eye.

Today, anthropologists often have specialized expertise. But in the 19th century, anthropology was not yet a discipline with its own paradigms, methods and boundaries. Most of its practitioners were self-taught or served as apprentices to a handful of recognized experts. Many such “amateurs” made important contributions to the field. And many of them were women.

She was born in 1857 to a wealthy family in San Francisco, then a fast-growing city of about 50,000 people. Near the shore, ships mired in mud—many abandoned by crews eager to make their fortunes in the gold fields—served as hostels to a restless, sometimes violent and mostly male population. Other adventurers found uncertain homes in hastily built hotels and rooming houses. But the city was also an exciting international settlement. Ships arrived daily from across the Pacific, Panama and the east via Cape Horn.

Her well-appointed household stood apart from the city’s wilder quarters, but the people who lived there reflected San Francisco’s international character. Her mother, Magdalena Parrott Nuttall, herself the daughter of an American businessman and a Mexican woman, spoke Spanish, and her grandfather, who lived nearby, employed a French lady’s maid; a nursemaid from New York; a chambermaid, laundress, housekeeper, coachman and groom from Ireland; a steward from Switzerland; a cook and additional servants from France; and nine day laborers from China.

When Zelia was 8, her family left San Francisco for Europe. Along with her older brother, Juanito, and her younger siblings Carmelita and George, Zelia and her parents set off for Ireland, her father’s native land. Over the course of 11 years, the Nuttalls made their way to London, Paris, the South of France, Germany, Italy and Switzerland. Throughout that time, Zelia was educated largely by governesses and tutors, with some formal schooling in Dresden and London. But her time overseas shaped her interest in ancient history and expanded her language skills, as she added French, German and Italian to her fluent Spanish. All of this expansion thrilled her mind, but it also made her feel increasingly out of step with the expectations for young women of her age. “My ideas and opinions form themselves I don’t know how, and I sometimes am astonished at the determined ideas I have!” she wrote in a November 1875 letter.

She took refuge in singing and tried to be pleased with the few social events she attended. Photos from the time show Zelia as an attractive young woman with large, dark eyes, arched eyebrows and stylishly arranged hair. Nevertheless, she was unhappy. “I was infinitely disgusted with some of the idiotic specimens of mankind I danced with,” she wrote in an 1876 letter after a party.

The Nuttalls returned to San Francisco in 1876, when she was nearly 20. Two years later, she met a young French anthropologist, Alphonse Pinart, already celebrated in his mid-20s as an explorer and linguist. He had been to Alaska, Arizona, Canada, Maine, Russia and the South Sea Islands. Pinart may have led the family to understand that he was wealthy. In fact, he was almost penniless, having already spent his significant inheritance.

They were married at the Nuttall home on May 10, 1880. During the next year and a half, the couple traveled to Paris, Madrid, Barcelona, Puerto Rico, Cuba, the Dominican Republic and Mexico. Pinart introduced Zelia to a burgeoning academic literature in ethnology and archaeology, and she began to understand the theories of linguistics. She found 16th-century Spanish hardly a challenge as she consulted annotated codices—pictorial documents that traced pre-Columbian genealogies and conquests in Mesoamerica. While Pinart dashed from project to project and roamed widely among countries, tribes and languages, Zelia began to demonstrate an intellectual style that was more focused and precise.

Despite the excitement of discovery, something began to go wrong in the marriage. Hints of Zelia’s distress can be found in her effusive letters home. There was, for example, the shipboard admission that her husband was less attentive than she had anticipated. She noted that he was “so quiet and undemonstrative” that it was hard to imagine they were newly married. Some fellow passengers thought they were brother and sister—an odd assumption to make, even in Victorian times, about newlyweds.

By contrast, Zelia is nowhere to be found in Pinart’s surviving correspondence. On April 6, 1881, she gave birth to a daughter, Roberta, who lived only 11 days. To add to this melancholy time, her beloved father died in May, leaving her doubly devastated. A letter Pinart wrote to a friend just a few months later from Cuba appeared on stationery with a black border, signifying mourning, but he made no reference to his wife, her father or their child.

Zelia found solace in learning about her heritage when she and Pinart traveled to Mexico in 1881. She was eager to see her mother’s homeland and to hone her understanding of its pre-Columbian cultures. While Pinart carried out his own research, she began to learn Nahuatl, and she toured villages where dialects of the language were still spoken and ruins where the marks of the past could still be found.

The couple returned to San Francisco on December 6, 1881. By then, Zelia was pregnant again. In late January, Pinart set out to spend several months in Guatemala, Nicaragua and Panama, while Zelia awaited the birth of her second child, Nadine, at her mother’s house.

What finally drove Zelia to sue for divorce, on the grounds of cruelty and neglect, remains elusive. She may have felt that Pinart had married her for access to her family’s fortune. Many years later, she angrily informed Nadine that Pinart had spent the $9,000 she had inherited from her father as well as her marriage settlement. When the money was gone, and when her family was firm that he shouldn’t expect any more, he abandoned his wife and child. Once Zelia demanded a separation, he did not contest it, though obtaining the divorce was a long process that started soon after the couple’s return from their travels and didn’t conclude until 1888.

In later life, Nadine Nuttall Pinart would reflect on how much it had cost her to grow up without a father. “From the time before I can remember, he was taboo to me,” she wrote in a 1961 letter to Ross Parmenter, a New York Times editor who wrote numerous books about Mexico and developed a fascination with Zelia Nuttall. “I was frightened by the violent scoldings I got for mentioning his name. Later, I compromised with myself and when asked about him quietly said, ‘I never knew him!’ I realized that people thought he was dead and were sorry for me and said no more. In those days it was a disgrace to have a divorced mother.”

If the period between 1881 and 1888, when Zelia finalized her divorce, was fraught with tension and heartache, this was also when she set about redefining herself as a woman with a vocation. She spent five months in Mexico with her mother, her daughter and her brother between December 1884 and April 1885, visiting Cuernavaca, Mexico City and Toluca, and exploring archaeological ruins. It was during this time that Zelia made her fateful winter visit to Teotihuacan and acquired her first artifacts.

The pieces of pottery she picked up that day were small terra-cotta heads. They were abundant in the area among the pyramids. At the time, the site was still being used as farmland, and the artifacts came to the surface during ploughing. The heads themselves were an inch or two long, with flat backs and a neck attached. Scholars before Zelia—Americans, Europeans and Mexicans—had mused creatively about such relics, describing differences in their facial features and the variety of headdresses they had sported. Drawing on 19th-century fascination with the topic of race, the French archaeologist Désiré Charnay became convinced that he could see in them African, Chinese and Greek facial features. Charnay mused: Had their creators migrated from Africa, Asia or Europe? And if racial identity was a marker of human development, as many believed at the time, what might this curious mixture of features reveal about civilizations in the Americas?

This kind of thinking was typical. Mistaken ideas about Darwinism led many Western scholars to believe that civilizations evolved along a linear, hierarchical path, from primitive villages to ancient kingdoms to modern industrial and urban societies. Not surprisingly, they used this to legitimize beliefs about the superiority of the white race.

Zelia Nuttall divided her collection of terra-cotta heads into three classes. The first included rudimentary efforts to represent a human face (as seen above, far left). The second class (including the bald second head from the left above) had holes for attaching earrings and other ornaments. The third category included the rest of the heads pictured here, sporting what Zelia called “a confusing variety of peculiar and not ungraceful headdresses.” Public Domain

Zelia generally accepted her era’s assumptions about race and class, and she was comfortable with her elite status and its privileges. Yet in her research, she did not categorize civilizations as primitive, savage or barbaric, as other scholars did, nor did she indulge in racial theories of cultural development. Instead, she sought to sweep aside this kind of speculation and replace it with observation and reason.

The more Zelia examined her terra-cotta heads, the more she realized she needed guidance from someone who had more experience in the study of antiquity than she had. At the time, there were no departments of anthropology in colleges or universities, no degrees to be earned, no clear routes to building a career. To pursue her burgeoning interest in the ancient civilizations of Mexico, and to decipher the meaning of an assortment of terra-cotta heads, she contacted Frederic Ward Putnam, the curator of Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology and a leading expert on Mesoamerica. He agreed to meet her in the fall of 1885. The meeting was all she hoped for: Putnam warmed to her work and encouraged her to follow her intuitive grasp of how to observe and interpret evidence.

Putnam’s regard for women’s intellectual capacities was clear. He was one of a small number of Harvard researchers who gave lectures at “the Annex,” an institution established for women who had passed the college’s admissions test but were not allowed to attend classes or earn a degree. (The Harvard Annex eventually became Radcliffe College.) He hired a resourceful administrative staff of women and encouraged them to play a role in managing the museum. He also had a “correspondence school,” which he conducted through a widespread exchange of letters. As he once wrote, “Several of my best students are women, who have become widely known by their thorough and important works and publications; and this I consider as high an honor as could be accorded to me.”

Within months of their first encounter, in late 1885, Putnam asked Zelia to become a special assistant in Mexican archaeology for the Peabody. Less than a year later, in the annual report of the Peabody Museum, he wrote about her appointment in glowing terms: “Familiar with the Nahuatl language … and with an exceptional talent for linguistics and archaeology, as well as being thoroughly informed in all the early native and Spanish writings relating to Mexico and its people, Mrs. Nuttall enters the study with a preparation as remarkable as it is exceptional.”

With guidance from Putnam, Zelia wrote an investigation of the terra-cotta heads, her first published scientific report, which appeared in the spring 1886 issue of the American Journal of Archaeology. “At the first glance,” she wrote, “the multitude and variety of these heads are confusing; but after prolonged observation, they seem to naturally distribute themselves into three large and well-defined Classes.”

Each class, she theorized, had been created at a different time and represented a different stage in the culture. The first class contained “primary and crude attempts at the representation of a human face.” The second class included the first efforts at artistry. Her inspection revealed “holes, notches and lines,” suggesting ways in which tiny headdresses, feathers or beads could have been attached to the heads, and noted traces of several colors of paint and different kinds of clay.

The third class was the most important, Zelia argued, because of the quality of the molding and carving. This class had “modifications of feature sufficient to give every specimen an individuality of its own,” she wrote. “The faces are invariably in repose, in some the eyes are closed … faces young and smooth, others very elongated, some with sunken cheeks, others with wrinkles.”

By comparing these terra-cotta heads with ancient pictographs and writings, she showed that some of the heads represented children while others depicted young men, warriors or elders. Others showed the distinct hairstyles described in the writings of Bernardino de Sahagún, a 16th-century Franciscan friar who spent 50 years studying the Aztec culture, language and history. “The noblewomen used to wear their hair hanging to the waist, or to the shoulders only. Others wore it long over the temples and ears only,” Sahagún had written. “Others entwined their hair with black cotton-thread and wore these twists about the head, forming two little horns above the forehead. Others have longer hair and cut its ends equally, as an embellishment, so that, when it is twisted and tied up, it looked as though it were all of the same length; and other women have their whole heads shorn or clipped.”

These concrete observations allowed Zelia to challenge popular ideas about the supposed African, Asian, European or Egyptian origins of the “races” in the Americas. For example, by studying the ornamentation the heads displayed, she was able to identify the person or god each artifact represented and interpret its ritual or symbolic purpose. One clearly corresponded with Tlaloc, the pan-Mesoamerican god of rain, who had been shown in the pictographs with a curved band above the mouth and circles around the eyes. Another head, molded with a turban-like cap, corresponded with the goddess Centeotl; Zelia speculated that the clay turbans once had real feathers attached. She also noted the significance of various poses. “In the picture-writings, closed eyes invariably convey the idea of death,” she wrote.

The article revealed how Zelia intended to be seen as a scholar. First, she made it clear that she had read what others had written. Then she revealed that she would go beyond existing speculation to answer questions that had puzzled others; hers was to be original and important work.

In 1892, Zelia presented a paper in Spain about the Aztec calendar stone. Buried during the destruction of the Aztec Empire, the calendar stone had been unearthed in December 1790, when repairs were being made to the Zócalo, Mexico City’s central plaza. The sculpted stone, some 12 feet in diameter and weighing 25 tons, became a popular attraction exhibited in the Mexico City Cathedral, steps from where it had been found. Antonio de León y Gama, a Mexican astronomer, mathematician and archaeologist, had written about its discovery and praised the intelligence of the Aztecs who had created it. Alexander von Humboldt, who saw the stone when he visited Mexico in 1803-1804, included a drawing in his Views of the Cordilleras and Monuments of the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas, published in 1810, and encouraged Mexican intellectuals to study the meaning of its concentric circles and numerous glyphs. Many others took on its puzzles in the years that followed.

At the time of Zelia’s presentation, the Mexican upper classes were carefully crafting a new national image—a story that would allow Mexico to take its place among the modern nations of the world. The Aztecs, Maya, Olmecs, Toltecs, Zapotecs and other cultures had left their imprints throughout the country in magnificent temples, enigmatic statues, gold jewelry, jade figurines and painted murals. This history was reclaimed as a national heritage every bit as glorious as those of Greece and Rome. A statue of Cuauhtémoc, the Aztec king who resisted Cortés, took its place on Mexico City’s elegant Paseo de la Reforma in 1887. The calendar stone had been installed in a place of honor in the National Museum in 1885. But little was known about the actual customs and beliefs of those ancient people.

The Aztec calendar stone, a central focus of Zelia’s research, has been on display at Mexico City’s National Museum of Anthropology since 1885. Alamy

With her extraordinary knowledge of surviving codices, Zelia offered a novel “reading” of the giant calendar stone that had stumped others and provided new insights into the annual and seasonal cycles of daily life in ancient Mexico, illuminating the cosmology, agriculture and trade patterns of the Aztecs. She presented another version of the paper at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893.

Zelia returned to Mexico City in February 1902, and after a personal audience with Mexican President José de la Cruz Porfirio Díaz, arranged by the U.S. ambassador, she embarked on a spree of travel to archaeological sites she had long wanted to visit. In May, she and 20-year-old Nadine joined friends at the Oaxacan ruins at Mitla, a religious center, where the “place of the dead” harbored both Mixtec and Zapotec art and architecture. On this dry, high plain ringed by mountains, Zelia strolled across vast stone patios, inspected the elaborate geometric friezes that lined and decorated them, explored temples and imagined a sophisticated society of kings, priests, nobles, artisans and farmers.

When the Spaniards arrived in Mexico in the 16th century, the Aztec Empire dominated the area. This map of its largest city, Tenochtitlan (now the historic center of Mexico City), was printed in 1524 in Nuremberg, Germany, likely based on a drawing by one of Hernán Cortés’ men. It shows the city’s elaborate network of roads, bridges and canals, complete with aqueducts and bathhouses. The Spaniards executed the last Aztec ruler, Moctezuma II Xocoyotzin, and forced his people to convert to Catholicism. Alamy

Zelia was welcomed into the international community of anthropologists in Mexico. She and Nadine traveled in the Yucatán with the young American anthropologist Alfred Tozzer, where they were beset by frequent rain and terrible roads. Arriving tired and wet in a small town, Tozzer, who would one day chair Harvard’s department of anthropology, was impressed by the women’s resilience. “Imagine the picture,” he wrote to his family on April 8, 1902. “Mrs. Nuttall, never accustomed to roughing it, a woman entertained by the crowned heads of Europe, sitting at a bench with the top part of my pajamas on drinking chocolate and her daughter with a flannel shirt of mine on doing the same.”

After a few months, Zelia and her daughter returned to Mexico City and purchased a mansion they called Casa Alvarado, in the upscale suburb of Coyoacán. The grand house never failed to impress. Frederick Starr, an anthropologist from the University of Chicago, was one of many who found the palace beautiful and restful: “We rode out to Coyoacán where we found Mrs. Nuttall and her daughter really charmingly situated. The color decoration is simple and strong. Nasturtiums are handsomely used in the patio and balcony effects. … While Mrs. Nuttall dressed, Miss Nuttall showed us through the garden, where a real transformation has been effected.”

Living in Mexico energized Zelia. In addition to her affiliation with Harvard, she had funding to travel and collect artifacts for the Department of Anthropology at the University of California. “With me here, in touch with the government and people, I think that American institutions can but profit and that I can do some good in advancing Science in this country,” she confided to Putnam.

Impressed by her knowledge of the country’s past, public officials and foreign visitors came to see her and listened carefully as she led them around her home and garden, explaining the collection she was busy assembling. Her garden, patio and verandas were home to an increasingly large number of stone artifacts, a beautiful carving of the serpent god Quetzalcóatl, revered for his wisdom, among them. She took up “digging” near Casa Alvarado, an activity one guest later recalled fondly. “Every morning after breakfast Mrs. Nuttall would give me a trowel and a bucket. She herself was equipped with a sort of short-handled spade, and we would go out into the surrounding country and ‘dig.’ We mostly found broken pieces of pottery, but she seemed to think some of them were significant, if not valuable. … She was a very handsome woman and very charming. She lived in great style, with many Mexican servants.”

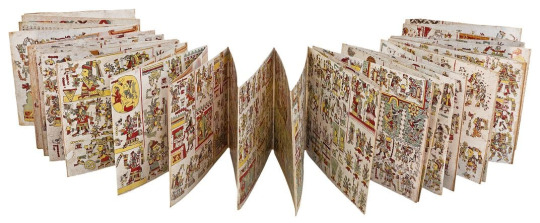

The Codex Borgia, an accordion-folded document of Aztec life, was brought to Europe during the Spanish colonial period. Made of animal skins and stretching 36 feet when unfolded, the codex catalogs different units of time and the deities associated with them. It also includes astrological predictions once used for arranging marriages. Zelia drew on the codex to help her decode the Aztec calendar. Courtesy Ziereis Facsimiles

A section from the Codex Borgia

Zelia continued to travel throughout the country. She found a 14-page codex painted on deerskin, with commentary in Nahuatl, that she believed so valuable that she bought it with her own money, selling some of her possessions to afford it. “Owing to my residence here I must keep it a profound secret that I possess and sent out of the country this Codex,” she wrote to Putnam.

While she was not above smuggling treasures out of Mexico, Zelia also worked in the National Museum, contributing to its displays and archives, and she became an honorary professor of the institution.

Zelia had never owned a home until she bought Casa Alvarado in 1902. In a letter, she described the property as “a beautiful old place with extensive gardens.” Smithsonian Archives

Her Sunday teas at Casa Alvarado were a study in salon orchestration. “She would have 30 or 40 people and she would change the groups she invited,” one visitor recalled. “Sometimes they were all people who knew each other. Or else she would bring people together she wanted to introduce to each other. They weren’t like old-style Mexican parties, with all the women on one side and men on the other. The men and women were mixed together.”

According to an oft-repeated legend, at one of her soirées, she advanced to welcome an eminent guest just as her voluminous Victorian drawers came loose and dropped to her ankles. She calmly stepped out of them and proceeded as if nothing had happened. Zelia was, above all, self-confident.

Zelia Nuttall left Mexico during the early months of 1910 and did not return to her beloved Casa Alvarado for seven years. Throughout that time, Mexico was in the midst of a violent revolution. As many as two million people lost their lives in the ten-year conflict, and the country’s infrastructure was reduced to tatters. Even after the end of the most extensive violence, turmoil erupted sporadically until the late 1920s.

By then, visitors to Casa Alvarado agreed that Zelia was rooted in a bygone era. She was a middle-aged woman with thick glasses who favored shawls, laces and jet beads. Her palace was still filled with stuff only a Victorian could accumulate, but Mexico was telling new stories about itself.

The writer D.H. Lawrence used Zelia as a model for a fictional character—“an elderly woman, rather like a Conquistador herself in her black silk dress and her little black shoulder-shawl.” Antropo Wiki

The elites of the previous generation had asserted that descendants of the Aztec, Maya and other civilizations deteriorated into poverty and abandon. Young artists and intellectuals now rejected this belief. In Diego Rivera’s vast public murals, he showed the people of Mexico being ground into poverty and submission by Spanish conquistadors, a rapacious church, foreign capitalism, the army and cruel politicians. Quetzalcóatl replaced Santa Claus at the National Stadium; Chapultepec Park hosted Mexico Night.

Zelia did not like the revolution and she did not approve of what came after it. She did not celebrate the masses; she believed in hierarchy and a natural order of classes and races. Yet she was determined to be relevant to a new era in Mexico. Casa Alvarado became a meeting place for politicians, journalists, writers and social scientists from Mexico and abroad, many of whom came to witness the possibilities of change in the aftermath of a people’s revolution.

Nevertheless, the stubborn elegance of Casa Alvarado in the 1920s was clear testimony that Zelia was not willing to give up her lifestyle. When the French American painter Jean Charlot was a guest at one of Zelia’s teas, he was aghast at the Mexican servants in white gloves.

When Zelia Nuttall died in 1933, the U.S. consul in Mexico City wrote to Nadine—by then a 51-year-old widow living in Cambridge, England—assuring her that they’d given her mother a tasteful funeral. “Your Mother was very highly thought of here, as evidenced by the floral offerings and the number of her friends who came to the funeral service at the cemetery, it being estimated that about one hundred persons were present.”

By that time, the field of anthropology was dramatically changing, becoming more systematic and organized. Those who entered the field in the 1920s and 1930s built expertise in the classroom and under supervision in the field, passing a variety of tests and milestones determined by academic experts and acquiring a credential as proof of the right to pursue these inquiries. With these rigorous new standards, they asserted their superiority as scholars over those of Zelia’s generation.

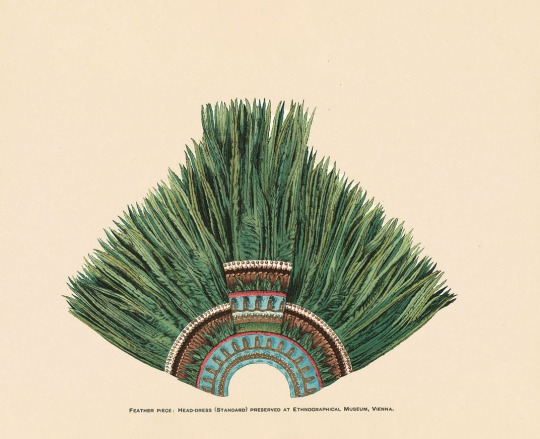

Researchers thought this item at Vienna’s Museum of Ethnology was a “Moorish hat” before Zelia identified it as a Mesoamerican headdress. Alamy

Yet Alfred Tozzer, in his memorial in the journal American Anthropologist, reflected that Zelia “was a remarkable example of 19th-century versatility.” She was wrong in some of her overarching theories. For instance, she fallaciously argued that ancient Phoenician travelers had carried their culture to Mesoamerica. But she was right about many other things. Through her letters, articles and books, we can trace what she got right and what she got wrong as a scholar, and we can follow her as she moved from one research obsession to the next.

Her private life is harder to grasp. Among all the artifacts, there is little about the quips and gossip she exchanged with friends, the piano music she liked to play and sing. We cannot know what was in the boxes of papers in the cellar of Casa Alvarado that were burned in the housecleaning undertaken by its new tenants. We cannot retrieve personal and public documents lost in the San Francisco earthquake in 1906.

What we do know is that she had to make sacrifices, often very personal ones. We can feel her vulnerability, uncertainty, anger and embarrassment in the letters she wrote, as well as her self-assuredness. It required unusual self-discipline to learn so many languages and to gain a mastery of ancient pictographs. Her almost constant travels imperiled her health even while they advanced her vast network of friends, colleagues and patrons. But she continued to work, and that work helped establish the foundation on which many others now build.

A single mother pursuing a career while looking after a family in a man’s world: In some ways, Zelia Nuttall was a very modern woman.

Adapted from In the Shadow of Quetzalcoatl: Zelia Nuttall and the Search for Mexico’s Ancient Civilizations by Merilee Grindle, published by The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. Copyright © 2023 by Merilee Grindle. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

#Women in history#Women in Anthropology#Zelia Nuttall#The Aztecs#Merilee Grindle#In the Shadow of Quetzalcoatl: Zelia Nuttall and the Search for Mexico's Ancient Civilizations#Books by women#Books about women#teotihuacan#mesoamerica#Nahuatl#Published women#Many of the first anthropologists were women#Alphonse Pinart was just another man who blew through his money#Women's careers flourishing after dumping a parasitic man#Frederic Ward Putnam#Men who encouraged women#The Annex#Lady scientist

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ticualtzincoatl, the “Beautiful Serpent”, an original character

This is my half-human, half-serpent character Ticualtzincoatl. The daughter of a mortal woman and the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl, this demigoddess lives in a cave outside of Tenochtitlan. She appears human from the waist up (aside from reptilian facial features), but has a black-and-gold snake tail instead of legs. She considers herself a “healer”, who kills and eats ailing humans. Many are also sacrificed to her, yet a clan leader later banished her for killing too many. However, she would return centuries later….

In her words, “A goddess never dies!”

She is cold, but respects humans who respect her. For example, she teams up with a human woman to find those who need “healing.” Her mother is her favorite human, even though she becomes a motherly figure to some human children. While she loves him, her father frustrates her with his strict expectations of her. She also loves being worshipped and is angry when the Spanish force her people to worship one god. When one conquistador tries to make a curiosity of her, she kills him.

I have written three stories about her— one set during the early Aztec period, one during the Spanish Conquest, and one during the modern era. She is special to me. (“Ticualtzin ” is a Nahuatl name meaning “you are beautiful” and “coatl” means serpent. As such, she is also called the “Beautiful Serpent.”)