#Many of the first anthropologists were women

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Anthropologist Zelia Nuttall transformed the way we think of ancient Mesoamerica

An illustration of the Aztec calendar stone surrounds a young portrait of anthropologist Zelia Nuttall. “Mrs. Nuttall’s investigations of the Mexican calendar appear to furnish for the first time a satisfactory key,” wrote one leading scholar.Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University

By Merilee Grindle

Author, In the Shadow of Quetzalcoatl: Zelia Nuttall and the Search for Mexico’s Ancient Civilizations

On a bright day early in 1885, Zelia Nuttall was strolling around the ancient ruins of Teotihuacán, the enormous ceremonial site north of Mexico City. Not yet 30, Zelia had a deep interest in the history of Mexico, and now, with her marriage in ruins and her future uncertain, she was on a trip with her mother, Magdalena; her brother George; and her 3-year-old daughter, Nadine, to distract her from her worries.

The site, which covered eight square miles, had once been home to the predecessors of the Aztecs. It included about 2,000 dwellings along with temples, plazas and pyramids where they charted the stars and made offerings to the sun and moon. As Zelia admired the impressive buildings, some shrouded in dirt and vegetation, she reached down and collected a few pieces of pottery from the dusty soil. They were plentiful and easy to find with a few brushes of her hand.

The moment she picked up those artifacts would prove to be pivotal in the life and long career of this trailblazing anthropologist. Over the next 50 years, Zelia’s careful study of artifacts would challenge the way people thought of Mesoamerican history. She was the first to decode the Aztec calendar and identify the purposes of ancient adornments and weapons. She untangled the organization of commercial networks and transcribed ancient songs. She found clues about the ancient Americas all over the world: Once, deep in the stacks of the British Museum, she found an Indigenous pictorial history that predated the Spanish conquest; skilled at interpreting Aztec drawings and symbols, and having taught herself Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs and their predecessors, she was the first to transcribe and translate this and other ancient manuscripts.

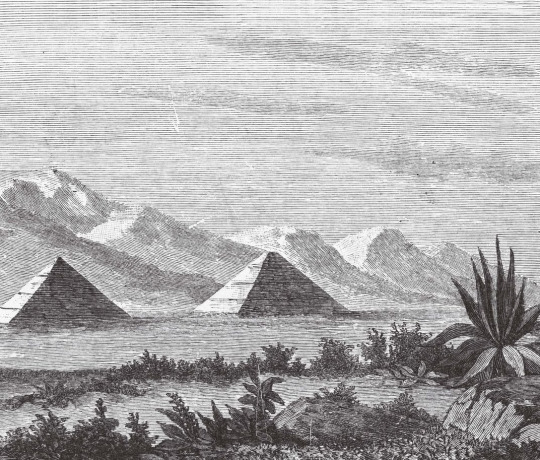

A 19th-century engraving of the pyramids of Teotihuacan. The Pyramid of the Sun was restored in 1910, on the centennial of the Mexican War of Independence. Bridgeman Images

She also served as a bridge between the United States and Mexico, living in both countries and working with leading national institutions in each. At a time when many scholars spun elaborate and unfounded theories based on 19th-century views of race, Zelia looked at the evidence and made concrete connections based on scientific observations. By the time she died, in 1933, she had published three books and more than 75 articles.

Yet during her lifetime, she was sometimes called an antiquarian, a folklorist or a “lady scientist.” When she died, scholarly journals and some newspapers ran notices and obituaries. After that, she largely passed from the public’s eye.

Today, anthropologists often have specialized expertise. But in the 19th century, anthropology was not yet a discipline with its own paradigms, methods and boundaries. Most of its practitioners were self-taught or served as apprentices to a handful of recognized experts. Many such “amateurs” made important contributions to the field. And many of them were women.

She was born in 1857 to a wealthy family in San Francisco, then a fast-growing city of about 50,000 people. Near the shore, ships mired in mud—many abandoned by crews eager to make their fortunes in the gold fields—served as hostels to a restless, sometimes violent and mostly male population. Other adventurers found uncertain homes in hastily built hotels and rooming houses. But the city was also an exciting international settlement. Ships arrived daily from across the Pacific, Panama and the east via Cape Horn.

Her well-appointed household stood apart from the city’s wilder quarters, but the people who lived there reflected San Francisco’s international character. Her mother, Magdalena Parrott Nuttall, herself the daughter of an American businessman and a Mexican woman, spoke Spanish, and her grandfather, who lived nearby, employed a French lady’s maid; a nursemaid from New York; a chambermaid, laundress, housekeeper, coachman and groom from Ireland; a steward from Switzerland; a cook and additional servants from France; and nine day laborers from China.

When Zelia was 8, her family left San Francisco for Europe. Along with her older brother, Juanito, and her younger siblings Carmelita and George, Zelia and her parents set off for Ireland, her father’s native land. Over the course of 11 years, the Nuttalls made their way to London, Paris, the South of France, Germany, Italy and Switzerland. Throughout that time, Zelia was educated largely by governesses and tutors, with some formal schooling in Dresden and London. But her time overseas shaped her interest in ancient history and expanded her language skills, as she added French, German and Italian to her fluent Spanish. All of this expansion thrilled her mind, but it also made her feel increasingly out of step with the expectations for young women of her age. “My ideas and opinions form themselves I don’t know how, and I sometimes am astonished at the determined ideas I have!” she wrote in a November 1875 letter.

She took refuge in singing and tried to be pleased with the few social events she attended. Photos from the time show Zelia as an attractive young woman with large, dark eyes, arched eyebrows and stylishly arranged hair. Nevertheless, she was unhappy. “I was infinitely disgusted with some of the idiotic specimens of mankind I danced with,” she wrote in an 1876 letter after a party.

The Nuttalls returned to San Francisco in 1876, when she was nearly 20. Two years later, she met a young French anthropologist, Alphonse Pinart, already celebrated in his mid-20s as an explorer and linguist. He had been to Alaska, Arizona, Canada, Maine, Russia and the South Sea Islands. Pinart may have led the family to understand that he was wealthy. In fact, he was almost penniless, having already spent his significant inheritance.

They were married at the Nuttall home on May 10, 1880. During the next year and a half, the couple traveled to Paris, Madrid, Barcelona, Puerto Rico, Cuba, the Dominican Republic and Mexico. Pinart introduced Zelia to a burgeoning academic literature in ethnology and archaeology, and she began to understand the theories of linguistics. She found 16th-century Spanish hardly a challenge as she consulted annotated codices—pictorial documents that traced pre-Columbian genealogies and conquests in Mesoamerica. While Pinart dashed from project to project and roamed widely among countries, tribes and languages, Zelia began to demonstrate an intellectual style that was more focused and precise.

Despite the excitement of discovery, something began to go wrong in the marriage. Hints of Zelia’s distress can be found in her effusive letters home. There was, for example, the shipboard admission that her husband was less attentive than she had anticipated. She noted that he was “so quiet and undemonstrative” that it was hard to imagine they were newly married. Some fellow passengers thought they were brother and sister—an odd assumption to make, even in Victorian times, about newlyweds.

By contrast, Zelia is nowhere to be found in Pinart’s surviving correspondence. On April 6, 1881, she gave birth to a daughter, Roberta, who lived only 11 days. To add to this melancholy time, her beloved father died in May, leaving her doubly devastated. A letter Pinart wrote to a friend just a few months later from Cuba appeared on stationery with a black border, signifying mourning, but he made no reference to his wife, her father or their child.

Zelia found solace in learning about her heritage when she and Pinart traveled to Mexico in 1881. She was eager to see her mother’s homeland and to hone her understanding of its pre-Columbian cultures. While Pinart carried out his own research, she began to learn Nahuatl, and she toured villages where dialects of the language were still spoken and ruins where the marks of the past could still be found.

The couple returned to San Francisco on December 6, 1881. By then, Zelia was pregnant again. In late January, Pinart set out to spend several months in Guatemala, Nicaragua and Panama, while Zelia awaited the birth of her second child, Nadine, at her mother’s house.

What finally drove Zelia to sue for divorce, on the grounds of cruelty and neglect, remains elusive. She may have felt that Pinart had married her for access to her family’s fortune. Many years later, she angrily informed Nadine that Pinart had spent the $9,000 she had inherited from her father as well as her marriage settlement. When the money was gone, and when her family was firm that he shouldn’t expect any more, he abandoned his wife and child. Once Zelia demanded a separation, he did not contest it, though obtaining the divorce was a long process that started soon after the couple’s return from their travels and didn’t conclude until 1888.

In later life, Nadine Nuttall Pinart would reflect on how much it had cost her to grow up without a father. “From the time before I can remember, he was taboo to me,” she wrote in a 1961 letter to Ross Parmenter, a New York Times editor who wrote numerous books about Mexico and developed a fascination with Zelia Nuttall. “I was frightened by the violent scoldings I got for mentioning his name. Later, I compromised with myself and when asked about him quietly said, ‘I never knew him!’ I realized that people thought he was dead and were sorry for me and said no more. In those days it was a disgrace to have a divorced mother.”

If the period between 1881 and 1888, when Zelia finalized her divorce, was fraught with tension and heartache, this was also when she set about redefining herself as a woman with a vocation. She spent five months in Mexico with her mother, her daughter and her brother between December 1884 and April 1885, visiting Cuernavaca, Mexico City and Toluca, and exploring archaeological ruins. It was during this time that Zelia made her fateful winter visit to Teotihuacan and acquired her first artifacts.

The pieces of pottery she picked up that day were small terra-cotta heads. They were abundant in the area among the pyramids. At the time, the site was still being used as farmland, and the artifacts came to the surface during ploughing. The heads themselves were an inch or two long, with flat backs and a neck attached. Scholars before Zelia—Americans, Europeans and Mexicans—had mused creatively about such relics, describing differences in their facial features and the variety of headdresses they had sported. Drawing on 19th-century fascination with the topic of race, the French archaeologist Désiré Charnay became convinced that he could see in them African, Chinese and Greek facial features. Charnay mused: Had their creators migrated from Africa, Asia or Europe? And if racial identity was a marker of human development, as many believed at the time, what might this curious mixture of features reveal about civilizations in the Americas?

This kind of thinking was typical. Mistaken ideas about Darwinism led many Western scholars to believe that civilizations evolved along a linear, hierarchical path, from primitive villages to ancient kingdoms to modern industrial and urban societies. Not surprisingly, they used this to legitimize beliefs about the superiority of the white race.

Zelia Nuttall divided her collection of terra-cotta heads into three classes. The first included rudimentary efforts to represent a human face (as seen above, far left). The second class (including the bald second head from the left above) had holes for attaching earrings and other ornaments. The third category included the rest of the heads pictured here, sporting what Zelia called “a confusing variety of peculiar and not ungraceful headdresses.” Public Domain

Zelia generally accepted her era’s assumptions about race and class, and she was comfortable with her elite status and its privileges. Yet in her research, she did not categorize civilizations as primitive, savage or barbaric, as other scholars did, nor did she indulge in racial theories of cultural development. Instead, she sought to sweep aside this kind of speculation and replace it with observation and reason.

The more Zelia examined her terra-cotta heads, the more she realized she needed guidance from someone who had more experience in the study of antiquity than she had. At the time, there were no departments of anthropology in colleges or universities, no degrees to be earned, no clear routes to building a career. To pursue her burgeoning interest in the ancient civilizations of Mexico, and to decipher the meaning of an assortment of terra-cotta heads, she contacted Frederic Ward Putnam, the curator of Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology and a leading expert on Mesoamerica. He agreed to meet her in the fall of 1885. The meeting was all she hoped for: Putnam warmed to her work and encouraged her to follow her intuitive grasp of how to observe and interpret evidence.

Putnam’s regard for women’s intellectual capacities was clear. He was one of a small number of Harvard researchers who gave lectures at “the Annex,” an institution established for women who had passed the college’s admissions test but were not allowed to attend classes or earn a degree. (The Harvard Annex eventually became Radcliffe College.) He hired a resourceful administrative staff of women and encouraged them to play a role in managing the museum. He also had a “correspondence school,” which he conducted through a widespread exchange of letters. As he once wrote, “Several of my best students are women, who have become widely known by their thorough and important works and publications; and this I consider as high an honor as could be accorded to me.”

Within months of their first encounter, in late 1885, Putnam asked Zelia to become a special assistant in Mexican archaeology for the Peabody. Less than a year later, in the annual report of the Peabody Museum, he wrote about her appointment in glowing terms: “Familiar with the Nahuatl language … and with an exceptional talent for linguistics and archaeology, as well as being thoroughly informed in all the early native and Spanish writings relating to Mexico and its people, Mrs. Nuttall enters the study with a preparation as remarkable as it is exceptional.”

With guidance from Putnam, Zelia wrote an investigation of the terra-cotta heads, her first published scientific report, which appeared in the spring 1886 issue of the American Journal of Archaeology. “At the first glance,” she wrote, “the multitude and variety of these heads are confusing; but after prolonged observation, they seem to naturally distribute themselves into three large and well-defined Classes.”

Each class, she theorized, had been created at a different time and represented a different stage in the culture. The first class contained “primary and crude attempts at the representation of a human face.” The second class included the first efforts at artistry. Her inspection revealed “holes, notches and lines,” suggesting ways in which tiny headdresses, feathers or beads could have been attached to the heads, and noted traces of several colors of paint and different kinds of clay.

The third class was the most important, Zelia argued, because of the quality of the molding and carving. This class had “modifications of feature sufficient to give every specimen an individuality of its own,” she wrote. “The faces are invariably in repose, in some the eyes are closed … faces young and smooth, others very elongated, some with sunken cheeks, others with wrinkles.”

By comparing these terra-cotta heads with ancient pictographs and writings, she showed that some of the heads represented children while others depicted young men, warriors or elders. Others showed the distinct hairstyles described in the writings of Bernardino de Sahagún, a 16th-century Franciscan friar who spent 50 years studying the Aztec culture, language and history. “The noblewomen used to wear their hair hanging to the waist, or to the shoulders only. Others wore it long over the temples and ears only,” Sahagún had written. “Others entwined their hair with black cotton-thread and wore these twists about the head, forming two little horns above the forehead. Others have longer hair and cut its ends equally, as an embellishment, so that, when it is twisted and tied up, it looked as though it were all of the same length; and other women have their whole heads shorn or clipped.”

These concrete observations allowed Zelia to challenge popular ideas about the supposed African, Asian, European or Egyptian origins of the “races” in the Americas. For example, by studying the ornamentation the heads displayed, she was able to identify the person or god each artifact represented and interpret its ritual or symbolic purpose. One clearly corresponded with Tlaloc, the pan-Mesoamerican god of rain, who had been shown in the pictographs with a curved band above the mouth and circles around the eyes. Another head, molded with a turban-like cap, corresponded with the goddess Centeotl; Zelia speculated that the clay turbans once had real feathers attached. She also noted the significance of various poses. “In the picture-writings, closed eyes invariably convey the idea of death,” she wrote.

The article revealed how Zelia intended to be seen as a scholar. First, she made it clear that she had read what others had written. Then she revealed that she would go beyond existing speculation to answer questions that had puzzled others; hers was to be original and important work.

In 1892, Zelia presented a paper in Spain about the Aztec calendar stone. Buried during the destruction of the Aztec Empire, the calendar stone had been unearthed in December 1790, when repairs were being made to the Zócalo, Mexico City’s central plaza. The sculpted stone, some 12 feet in diameter and weighing 25 tons, became a popular attraction exhibited in the Mexico City Cathedral, steps from where it had been found. Antonio de León y Gama, a Mexican astronomer, mathematician and archaeologist, had written about its discovery and praised the intelligence of the Aztecs who had created it. Alexander von Humboldt, who saw the stone when he visited Mexico in 1803-1804, included a drawing in his Views of the Cordilleras and Monuments of the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas, published in 1810, and encouraged Mexican intellectuals to study the meaning of its concentric circles and numerous glyphs. Many others took on its puzzles in the years that followed.

At the time of Zelia’s presentation, the Mexican upper classes were carefully crafting a new national image—a story that would allow Mexico to take its place among the modern nations of the world. The Aztecs, Maya, Olmecs, Toltecs, Zapotecs and other cultures had left their imprints throughout the country in magnificent temples, enigmatic statues, gold jewelry, jade figurines and painted murals. This history was reclaimed as a national heritage every bit as glorious as those of Greece and Rome. A statue of Cuauhtémoc, the Aztec king who resisted Cortés, took its place on Mexico City’s elegant Paseo de la Reforma in 1887. The calendar stone had been installed in a place of honor in the National Museum in 1885. But little was known about the actual customs and beliefs of those ancient people.

The Aztec calendar stone, a central focus of Zelia’s research, has been on display at Mexico City’s National Museum of Anthropology since 1885. Alamy

With her extraordinary knowledge of surviving codices, Zelia offered a novel “reading” of the giant calendar stone that had stumped others and provided new insights into the annual and seasonal cycles of daily life in ancient Mexico, illuminating the cosmology, agriculture and trade patterns of the Aztecs. She presented another version of the paper at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893.

Zelia returned to Mexico City in February 1902, and after a personal audience with Mexican President José de la Cruz Porfirio Díaz, arranged by the U.S. ambassador, she embarked on a spree of travel to archaeological sites she had long wanted to visit. In May, she and 20-year-old Nadine joined friends at the Oaxacan ruins at Mitla, a religious center, where the “place of the dead” harbored both Mixtec and Zapotec art and architecture. On this dry, high plain ringed by mountains, Zelia strolled across vast stone patios, inspected the elaborate geometric friezes that lined and decorated them, explored temples and imagined a sophisticated society of kings, priests, nobles, artisans and farmers.

When the Spaniards arrived in Mexico in the 16th century, the Aztec Empire dominated the area. This map of its largest city, Tenochtitlan (now the historic center of Mexico City), was printed in 1524 in Nuremberg, Germany, likely based on a drawing by one of Hernán Cortés’ men. It shows the city’s elaborate network of roads, bridges and canals, complete with aqueducts and bathhouses. The Spaniards executed the last Aztec ruler, Moctezuma II Xocoyotzin, and forced his people to convert to Catholicism. Alamy

Zelia was welcomed into the international community of anthropologists in Mexico. She and Nadine traveled in the Yucatán with the young American anthropologist Alfred Tozzer, where they were beset by frequent rain and terrible roads. Arriving tired and wet in a small town, Tozzer, who would one day chair Harvard’s department of anthropology, was impressed by the women’s resilience. “Imagine the picture,” he wrote to his family on April 8, 1902. “Mrs. Nuttall, never accustomed to roughing it, a woman entertained by the crowned heads of Europe, sitting at a bench with the top part of my pajamas on drinking chocolate and her daughter with a flannel shirt of mine on doing the same.”

After a few months, Zelia and her daughter returned to Mexico City and purchased a mansion they called Casa Alvarado, in the upscale suburb of Coyoacán. The grand house never failed to impress. Frederick Starr, an anthropologist from the University of Chicago, was one of many who found the palace beautiful and restful: “We rode out to Coyoacán where we found Mrs. Nuttall and her daughter really charmingly situated. The color decoration is simple and strong. Nasturtiums are handsomely used in the patio and balcony effects. … While Mrs. Nuttall dressed, Miss Nuttall showed us through the garden, where a real transformation has been effected.”

Living in Mexico energized Zelia. In addition to her affiliation with Harvard, she had funding to travel and collect artifacts for the Department of Anthropology at the University of California. “With me here, in touch with the government and people, I think that American institutions can but profit and that I can do some good in advancing Science in this country,” she confided to Putnam.

Impressed by her knowledge of the country’s past, public officials and foreign visitors came to see her and listened carefully as she led them around her home and garden, explaining the collection she was busy assembling. Her garden, patio and verandas were home to an increasingly large number of stone artifacts, a beautiful carving of the serpent god Quetzalcóatl, revered for his wisdom, among them. She took up “digging” near Casa Alvarado, an activity one guest later recalled fondly. “Every morning after breakfast Mrs. Nuttall would give me a trowel and a bucket. She herself was equipped with a sort of short-handled spade, and we would go out into the surrounding country and ‘dig.’ We mostly found broken pieces of pottery, but she seemed to think some of them were significant, if not valuable. … She was a very handsome woman and very charming. She lived in great style, with many Mexican servants.”

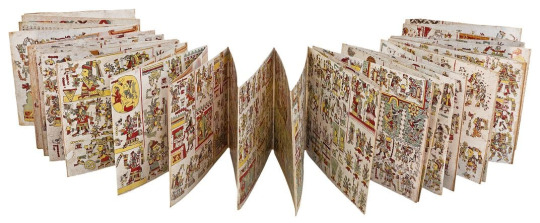

The Codex Borgia, an accordion-folded document of Aztec life, was brought to Europe during the Spanish colonial period. Made of animal skins and stretching 36 feet when unfolded, the codex catalogs different units of time and the deities associated with them. It also includes astrological predictions once used for arranging marriages. Zelia drew on the codex to help her decode the Aztec calendar. Courtesy Ziereis Facsimiles

A section from the Codex Borgia

Zelia continued to travel throughout the country. She found a 14-page codex painted on deerskin, with commentary in Nahuatl, that she believed so valuable that she bought it with her own money, selling some of her possessions to afford it. “Owing to my residence here I must keep it a profound secret that I possess and sent out of the country this Codex,” she wrote to Putnam.

While she was not above smuggling treasures out of Mexico, Zelia also worked in the National Museum, contributing to its displays and archives, and she became an honorary professor of the institution.

Zelia had never owned a home until she bought Casa Alvarado in 1902. In a letter, she described the property as “a beautiful old place with extensive gardens.” Smithsonian Archives

Her Sunday teas at Casa Alvarado were a study in salon orchestration. “She would have 30 or 40 people and she would change the groups she invited,” one visitor recalled. “Sometimes they were all people who knew each other. Or else she would bring people together she wanted to introduce to each other. They weren’t like old-style Mexican parties, with all the women on one side and men on the other. The men and women were mixed together.”

According to an oft-repeated legend, at one of her soirées, she advanced to welcome an eminent guest just as her voluminous Victorian drawers came loose and dropped to her ankles. She calmly stepped out of them and proceeded as if nothing had happened. Zelia was, above all, self-confident.

Zelia Nuttall left Mexico during the early months of 1910 and did not return to her beloved Casa Alvarado for seven years. Throughout that time, Mexico was in the midst of a violent revolution. As many as two million people lost their lives in the ten-year conflict, and the country’s infrastructure was reduced to tatters. Even after the end of the most extensive violence, turmoil erupted sporadically until the late 1920s.

By then, visitors to Casa Alvarado agreed that Zelia was rooted in a bygone era. She was a middle-aged woman with thick glasses who favored shawls, laces and jet beads. Her palace was still filled with stuff only a Victorian could accumulate, but Mexico was telling new stories about itself.

The writer D.H. Lawrence used Zelia as a model for a fictional character—“an elderly woman, rather like a Conquistador herself in her black silk dress and her little black shoulder-shawl.” Antropo Wiki

The elites of the previous generation had asserted that descendants of the Aztec, Maya and other civilizations deteriorated into poverty and abandon. Young artists and intellectuals now rejected this belief. In Diego Rivera’s vast public murals, he showed the people of Mexico being ground into poverty and submission by Spanish conquistadors, a rapacious church, foreign capitalism, the army and cruel politicians. Quetzalcóatl replaced Santa Claus at the National Stadium; Chapultepec Park hosted Mexico Night.

Zelia did not like the revolution and she did not approve of what came after it. She did not celebrate the masses; she believed in hierarchy and a natural order of classes and races. Yet she was determined to be relevant to a new era in Mexico. Casa Alvarado became a meeting place for politicians, journalists, writers and social scientists from Mexico and abroad, many of whom came to witness the possibilities of change in the aftermath of a people’s revolution.

Nevertheless, the stubborn elegance of Casa Alvarado in the 1920s was clear testimony that Zelia was not willing to give up her lifestyle. When the French American painter Jean Charlot was a guest at one of Zelia’s teas, he was aghast at the Mexican servants in white gloves.

When Zelia Nuttall died in 1933, the U.S. consul in Mexico City wrote to Nadine—by then a 51-year-old widow living in Cambridge, England—assuring her that they’d given her mother a tasteful funeral. “Your Mother was very highly thought of here, as evidenced by the floral offerings and the number of her friends who came to the funeral service at the cemetery, it being estimated that about one hundred persons were present.”

By that time, the field of anthropology was dramatically changing, becoming more systematic and organized. Those who entered the field in the 1920s and 1930s built expertise in the classroom and under supervision in the field, passing a variety of tests and milestones determined by academic experts and acquiring a credential as proof of the right to pursue these inquiries. With these rigorous new standards, they asserted their superiority as scholars over those of Zelia’s generation.

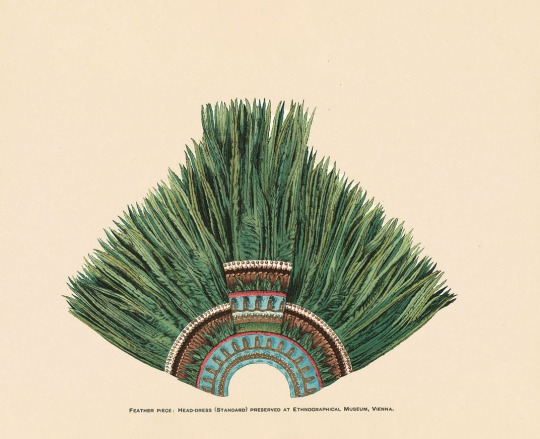

Researchers thought this item at Vienna’s Museum of Ethnology was a “Moorish hat” before Zelia identified it as a Mesoamerican headdress. Alamy

Yet Alfred Tozzer, in his memorial in the journal American Anthropologist, reflected that Zelia “was a remarkable example of 19th-century versatility.” She was wrong in some of her overarching theories. For instance, she fallaciously argued that ancient Phoenician travelers had carried their culture to Mesoamerica. But she was right about many other things. Through her letters, articles and books, we can trace what she got right and what she got wrong as a scholar, and we can follow her as she moved from one research obsession to the next.

Her private life is harder to grasp. Among all the artifacts, there is little about the quips and gossip she exchanged with friends, the piano music she liked to play and sing. We cannot know what was in the boxes of papers in the cellar of Casa Alvarado that were burned in the housecleaning undertaken by its new tenants. We cannot retrieve personal and public documents lost in the San Francisco earthquake in 1906.

What we do know is that she had to make sacrifices, often very personal ones. We can feel her vulnerability, uncertainty, anger and embarrassment in the letters she wrote, as well as her self-assuredness. It required unusual self-discipline to learn so many languages and to gain a mastery of ancient pictographs. Her almost constant travels imperiled her health even while they advanced her vast network of friends, colleagues and patrons. But she continued to work, and that work helped establish the foundation on which many others now build.

A single mother pursuing a career while looking after a family in a man’s world: In some ways, Zelia Nuttall was a very modern woman.

Adapted from In the Shadow of Quetzalcoatl: Zelia Nuttall and the Search for Mexico’s Ancient Civilizations by Merilee Grindle, published by The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. Copyright © 2023 by Merilee Grindle. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

#Women in history#Women in Anthropology#Zelia Nuttall#The Aztecs#Merilee Grindle#In the Shadow of Quetzalcoatl: Zelia Nuttall and the Search for Mexico's Ancient Civilizations#Books by women#Books about women#teotihuacan#mesoamerica#Nahuatl#Published women#Many of the first anthropologists were women#Alphonse Pinart was just another man who blew through his money#Women's careers flourishing after dumping a parasitic man#Frederic Ward Putnam#Men who encouraged women#The Annex#Lady scientist

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Southern Reach series (10th Anniversary Editions) by Jeff VanderMeer

Cover art by Pablo Delcan

MacMillan, 2014-2024

Annihilation (2014)

Area X has been cut off from the rest of the world for decades. Nature has reclaimed the last vestiges of human civilization. The first expedition returned with reports of a pristine, Edenic landscape; the second expedition ended in mass suicide, the third in a hail of gunfire as its members turned on one another. The members of the eleventh expedition returned as shadows of their former selves, and within weeks, all had died of cancer. In Annihilation, the first volume of Jeff VanderMeer's Southern Reach Trilogy, we join the twelfth expedition.

The group is made up of four women: an anthropologist; a surveyor; a psychologist, the de facto leader; and our narrator, a biologist. Their mission is to map the terrain, record all observations of their surroundings and of one another, and, above all, avoid being contaminated by Area X itself.

They arrive expecting the unexpected, and Area X delivers—but it’s the surprises that came across the border with them and the secrets the expedition members are keeping from one another that change everything

Authority (2014)

After thirty years, the only human engagement with Area X—a seemingly malevolent landscape surrounded by an invisible border and mysteriously wiped clean of all signs of civilization—has been a series of expeditions overseen by a government agency so secret it has almost been forgotten: the Southern Reach. Following the tumultuous twelfth expedition chronicled in Annihilation, the agency is in complete disarray.

John Rodríguez (aka "Control") is the Southern Reach's newly appointed head. Working with a distrustful but desperate team, a series of frustrating interrogations, a cache of hidden notes, and hours of profoundly troubling video footage, Control begins to penetrate the secrets of Area X. But with each discovery he must confront disturbing truths about himself and the agency he's pledged to serve.

In Authority, the second volume of Jeff VanderMeer's Southern Reach trilogy, Area X's most disturbing questions are answered . . . but the answers are far from reassuring.

Acceptance (2014)

It is winter in Area X, the mysterious wilderness that has defied explanation for thirty years, rebuffing expedition after expedition, refusing to reveal its secrets. As Area X expands, the agency tasked with investigating and overseeing it—the Southern Reach—has collapsed on itself in confusion. Now one last, desperate team crosses the border, determined to reach a remote island that may hold the answers they've been seeking. If they fail, the outer world is in peril.

Meanwhile, Acceptance tunnels ever deeper into the circumstances surrounding the creation of Area X—what initiated this unnatural upheaval? Among the many who have tried, who has gotten close to understanding Area X—and who may have been corrupted by it?

In this last installment of Jeff VanderMeer's Southern Reach trilogy, the mysteries of Area X may be solved, but their consequences and implications are no less profound—or terrifying.

Absolution (2024)

When the Southern Reach Trilogy was first published a decade ago, it was an instant sensation, celebrated in a front-page New York Times story before publication, hailed by Stephen King and many others. Each volume climbed the bestsellers list; awards were won; the books made the rare transition from paperback original to hardcover; the movie adaptation became a cult classic. All told, the trilogy has sold more than a million copies and has secured its place in the pantheon of twenty-first-century literature.

And yet for all this, for Jeff VanderMeer there was never full closure to the story of Area X. There were a few mysteries that had gone unsolved, some key points of view never aired. There were stories left to tell. There remained questions about who had been complicit in creating the conditions for Area X to take hold; the story of the first mission into the Forgotten Coast—before Area X was called Area X—had never been fully told; and what if someone had foreseen the world after Acceptance? How crazy would they seem?

Structured in three parts, each recounting a new expedition, there are some long-awaited answers here, to be sure, but also more questions, and profound new surprises. Absolution is a brilliant, beautiful, and ever-terrifying plunge into unique and fertile literary territory. It is the final word on one of the most provocative and popular speculative fiction series of our time

#book cover art#cover illustration#cover art#halloween#halloween 2024#happy halloween#jeff vandermeer#Pablo Delcan#annihilation#authority#acceptance#absolution#southern reach trilogy#southern reach series#apocalypse fiction#post apocalyptic#post apocalypse#post apocalyptic fiction#sci-fi#science fiction#dystopian science fiction#dystopia#horror#horror scifi

562 notes

·

View notes

Note

I don’t know if you’ve answered something similar before, but I’m writing for a story including mermaids and sirens and was wondering if you had any information or advice?

Writing Notes: Mermaids & Sirens

Mermaid - a fabled marine creature with the head and upper body of a human being and the tail of a fish.

Siren - (in Greek mythology) a creature half bird and half woman who lured sailors to destruction by the sweetness of her song.

MERMAIDS

Similar divine or semidivine beings appear in ancient mythologies (e.g., the Chaldean sea god Ea, or Oannes).

In European folklore, mermaids (sometimes called sirens) and mermen were natural beings who, like fairies, had magical and prophetic powers. They loved music and often sang. Though very long-lived, they were mortal and had no souls.

Many folktales record marriages between mermaids (who might assume human form) and men. In most, the man steals the mermaid’s cap or belt, her comb or mirror. While the objects are hidden she lives with him; if she finds them she returns at once to the sea.

In some variants the marriage lasts while certain agreed-upon conditions are fulfilled, and it ends when the conditions are broken.

Though sometimes kindly, mermaids and mermen were usually dangerous to man.

Their gifts brought misfortune, and, if offended, the beings caused floods or other disasters.

To see one on a voyage was an omen of shipwreck.

They sometimes lured mortals to death by drowning, as did the Lorelei of the Rhine, or enticed young people to live with them underwater, as did the mermaid whose image is carved on a bench in the church of Zennor, Cornwall, England.

Aquatic mammals, such as the dugong and manatee, that suckle their young in human fashion above water are considered by some to underlie these legends.

SIRENS

According to Homer, there were two Sirens on an island in the western sea between Aeaea and the rocks of Scylla.

Later the number was usually increased to three, and they were located on the west coast of Italy, near Naples.

They were variously said to be the daughters of the sea god Phorcys or of the river god Achelous by one of the Muses.

In Homer’s Odyssey, Book XII, the Greek hero Odysseus, advised by the sorceress Circe, escaped the danger of their song by stopping the ears of his crew with wax so that they were deaf to the Sirens.

Odysseus himself wanted to hear their song but had himself tied to the mast so that he would not be able to steer the ship off its course.

Apollonius of Rhodes, in Argonautica, Book IV, relates that when the Argonauts sailed that way, Orpheus sang so divinely that only one of the Argonauts heard the Sirens’ song.

According to Argonautica, Butes alone was compelled by the Sirens’ voices to jump into the water, but his life was saved by the goddess Cypris, a cult name for Aphrodite.

In Hyginus’s Fabulae, no. 141, a mortal’s ability to resist them causes the Sirens to commit suicide.

Ovid (Metamorphoses, Book V) wrote that the Sirens were human companions of Persephone.

After she was carried off by Hades, they sought her everywhere and finally prayed for wings to fly across the sea. The gods granted their prayer.

In some versions Demeter turned them into birds to punish them for not guarding Persephone.

In art, the Sirens appeared first as birds with the heads of women and later as women, sometimes winged, with bird legs.

The Sirens seem to have evolved from an ancient tale of the perils of early exploration combined with an Asian image of a bird-woman. Anthropologists explain the Asian image as a soul-bird—i.e., a winged ghost that stole the living to share its fate. In that respect the Sirens had affinities with the Harpies.

Some Character Tropes

Alchemic Elementals. Merfolk and similar beings are sometimes portrayed as water elementals.

Bathtub Mermaid. Merfolk and other aquatic creatures kept in stationary tanks and other containers.

Inhumanly Beautiful Race. Merfolk, mermaids in particular, are often very beautiful beyond human standards.

Mermaid Arc Emergence. When mermaids surface, it is often with splendor.

Mermaid in a Wheelchair. Mermaids on land often use wheelchairs to get around.

Mobile Fishbowl. Merfolk who can't breathe air bring water with them to interact with land-dwellers.

Mute Mermaid. A mermaid who is unable to speak.

Selkies and Wereseals. Human-seal shapeshifters.

Sirens Are Mermaids. The Sirens of mythology portrayed as mermaids.

Unscaled Merfolk. Merfolk that are aren't scaled fish below the waist.

Sources: 1 2 3 ⚜ More: Notes ⚜ Writing Resources PDFs

Choose which of these notes you'd like to incorporate in your story, and do more research if you need to add more detail. Hope these help inspire your writing!

#anonymous#mermaid#siren#writing notes#writeblr#literature#writers on tumblr#writing reference#dark academia#spilled ink#writing prompt#creative writing#character development#character inspiration#writing ideas#writing inspiration#writing resources

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

So with Oppenheimer coming out tomorrow, I feel a certain level of responsibility to share some important resources for people to understand more about the context of the Manhattan Project. Because for my family, it’s not just a piece of history but an ongoing struggle that’s colonized and irradiated generations of New Mexicans’ lives and altered our identity forever. Not only has the legacy of the Manhattan Project continued to harm and displace Indigenous and Hispanic people but it’s only getting bigger: Biden recently tasked the Los Alamos National Lab facility to create 30 more plutonium pits (the core of a nuclear warhead) by 2026. So this is a list of articles, podcasts and books to check out to hear the real stories of the local people living with this unique legacy that’s often overlooked.

This is simply the latest mainstream interest in the Oppenheimer story and it always ALWAYS silences the trauma of the brown people the US government took advantage of to make their death star. I might see the movie, I honestly might not. I’m not trying to judge anyone for seeing what I’m sure will be an entertaining piece of art. I just want y’all to leave the theater knowing that this story goes beyond what’s on the screen and touches real people’s lives: people whose whole families died of multiple cancers from radiation from the Trinity test, people who’s ancestral lands were poisoned, people who never came back from their job because of deadly work conditions. This is our story too.

The first and best place to learn more about this history and how to support those still resisting is to follow Tewa Women United. They’ve assembled an incredible list of resources from the people who’ve been fighting this fight the longest.

https://tewawomenunited.org/2023/07/oppenheimer-and-the-other-side-of-the-story

The writer Alicia Inez Guzman is currently writing a series about the nuclear industrial complex in New Mexico, its history and cultural impacts being felt today.

https://searchlightnm.org/my-nuclear-family/

https://searchlightnm.org/the-abcs-of-a-nuclear-education/

https://searchlightnm.org/plutonium-by-degrees/

Danielle Prokop at Source NM is an excellent reporter (and friend) who has been covering activists fighting for Downwinder status from the federal government. They’re hoping that the success of Oppenheimer will bring new attention to their cause.

https://sourcenm.com/2023/07/19/anger-hope-for-nm-downwinders/

https://sourcenm.com/2022/01/27/new-mexico-downwinders-demand-recognition-justice/

One often ignored side of the Manhattan Project story that’s personal for me is that the government illegally seized the land that the lab facilities eventually were built on. Before 1942, it was homesteading land for ranchers for more than 30 families (my grandpa’s side of the family was one). But when the location was decided, the government evicted the residents, bought their land for peanuts and used their cattle for target practice. Descendants of the homesteaders later sued and eventually did get compensated for their treatment (though many say it was far below what they were owed)

https://www.hcn.org/issues/175/5654

Myrriah Gomez is an incredible scholar in this field, working as a historian, cultural anthropologist and activist using a framework of “nuclear colonialism” to foreground the Manhattan Project. Her book Nuclear Nuevo Mexico is an amazing collection of oral stories and archival record that positions New Mexico’s era of nuclear colonialism in the context of its Spanish and American eras of colonialism. A must read for anyone who’s made it this far.

https://uapress.arizona.edu/book/nuclear-nuevo-mexico

There isn’t a ton of podcasts about this (yet 👀) but recently the Washington Post’s podcast Field Trip did an episode about White Sands National Monument. The story is a beautifully written and sound designed piece that spotlights the Downwinder activists and also a discovery of Indigenous living in the Trinity test area going back thousands of years. I was blown away by it.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/podcasts/field-trip/white-sands-national-park/

#oppenheimer#oppenheimer movie#barbenheimer#manhattan project#new mexico#los alamos#I never do posts like this#but I felt compelled#theres just so much like nuclear worship going on right now

763 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nih'a'ca Tales

Nih'a'ca tales are Arapaho legends concerning the trickster figure Nih'a'ca, who, according to Arapaho lore, is the first haxu'xan (two-spirit), a third gender, often highly regarded by many Native American nations, including the Arapaho. The Nih'a'ca tales are similar to the Wihio tales of the Cheyenne and the Iktomi tales of the Sioux.

North American Panther

Rodney Cammauf /National Park Service (Public Domain)

Circumstances and situations differ between the Nih'a'ca tales and those concerning trickster figures of other Native peoples of North America, but the central character of the trickster plays the same role – sometimes as sage and mediator, sometimes as schemer and villain – in them all. In the case of Nih'a'ca – always referred to by the male pronoun in English translations of Arapaho tales – he is frequently depicted in legend as someone who tries to better himself, usually at the expense of others or by trying to take shortcuts, and suffers for it.

At the same time, Nih'a'ca can be wise, offering advice, or clever, as in the story Nih'a'ca Pursued by the Rolling Skull, in which he must find a way to escape death. His identity as a haxu'xan is often, though not always, central to the story's plot – as in Nih'a'ca and the Panther-Young-Man where he, identifying as a woman, marries a panther – and, in stories where his gender is highlighted, serves to teach an important cultural, moral, lesson.

The Nih'a'ca tales are still told in Arapaho and Cheyenne communities, as well as others – including LGBTQ organizations – not only for their entertainment value but for the lessons they offer on personal responsibility and the proper respect and treatment to be shown to others. Like the trickster figures of other nations, Nih'a'ca is often depicted as, or associated with, the spider – spinning webs to catch others which often wind up entangling himself.

The Two-Spirit & Nih'a'ca

Two-Spirit is a modern designation, coined as recently as 1990, for the third gender recognized by many Native American nations for centuries before their contact with European immigrants. Because the term is so new, the two-spirit is often, incorrectly, assumed to be a recent 'discovery' made by anthropologists when, actually, European accounts going back to 1775 reference a third gender among North American Native peoples and the oral histories, myths, and legends – like the Nih'a'ca tales – also attest to the long-standing recognition of two-spirits in a given community.

As the term implies, a two-spirit is someone who recognizes both a male and female spirit dwelling within and often, though not always, dresses in the clothes and performs the duties of their opposite biological sex. Because they are understood as both male and female, two-spirits are recognized as possessing especially keen insight and often serve as mediators – in the present as they did in the past – in resolving personal or communal disputes. They were, and are (or can be), also regarded as holy people – "medicine men" and "medicine women" – serving as mediators between the people and the spirit world. Scholar Larry J. Zimmerman comments:

The relationship between a holy person and the spirit world is almost that of a personal religion. The first meeting with the spirits becomes the personal myth, and the power of this myth is important for establishing the holy person's credentials with the tribe, on behalf of which his or her skills are used to locate game, find lost objects, and, above all, treat the sick. The holy person can enter a trance at will and journey to the sacred world.

(132-133)

While Nih'a'ca is sometimes depicted as a holy person, he is more often quite the opposite, possessing characteristics such as selfishness, cruelty, and a blatant disregard for cultural norms. Through the Nih'a'ca tales, which frequently conclude with the central character suffering for his misdeeds, higher values including selflessness, kindness, and respect for tradition and the feelings of others are highlighted.

Nih'a'ca, then, usually serves as an exemplar of bad behavior and is given the identity of a two-spirit – in fact, the first two-spirit in the world – because the recognition of the sacred aspect of the two-spirit further emphasizes just how misguided Nih'a'ca's choices and actions can be. The tales themselves are a kind of 'trickster' turning expectations upside down and, in so doing, offer an audience the opportunity for reflection on their own behavior and the possibility of transformation.

Continue reading...

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

They say there's a documentary out there. It's titled by most as "the mammoth hunter". Very few people have seen it, very few people are allowed to. It's the oldest documentary made on earth.

Alien anthropologists, these strange mantis like organisms, came to earth around when homosapiens were just making their way into Europe, to film a documentary on the local culture. They were there for a broader research project but the only thing they left was the documentary.

They weren't there to do anything special. They didn't share any technology with us. Didn't build any great monuments or start any civilizations. They really just wanted to learn more about our culture. It took them awhile to get our ansestors to be ok with interacting with them, but eventually they did, and spent a few years with one tribe.

The documentary is amazing from a modern lense. There is footage of tribesmen, the ansestors of modern humanity, living their lives. There's film of a huntsman taking down a wooly rino, of women hiding from now long dead Saber tooth tigers. And there's footage of them just existing, singing songs, playing with their children, showing the documentary crew how they make stone tools or how they make their art. One of the longest scenes is just of one of them telling on of their people's stories, thousands of years before any of their descendents will have a chance to write a story in stone.

And they were freindly with the crew. Whatever culture was making the documentary they didn't seem like the type to want to colonize or exploit them, or at least that wasn't the goal of the scientists, even if others on their planet would have. They just wanted to learn. And though the tribesmen were scared of them at first, eventually they befriended eachother, and knew eachothers names. The humans let them into their homes, and let them eat their food, and partake in their rituals.

From what we know the second expedition had to leave early. That's actually why we have a copy of the documentary, because they left it there. From scattered notes and things some of the scientists said in the film, we know it's quite possible that the aliens were on the brink of some sort of war on their homeworlds. Many of the scientists seemed to fear that weapons of mass destruction would be used, and reset their civilization to something as primitive as what ours was at the time. Mabye that's part why they thought to make the documentary when they did. A lot of people think they wanted to come back, but they just couldn't.

We don't know where they are now, but we've grown a lot since we last saw that civilization, let's hope we get a chance to see them again, even if our roles have to be reversed, let's hope we can still be freinds after so long.

#196#worldbuilding#writing#my worldbuilding#my writing#hopepunk#hopeposting#science fiction#science fiction writing#scifi writing#scifi worldbuilding#scifi#sci fi writing#sci fi worldbuilding#aliens#alien#alien civilization#ancient aliens#short fiction#short stories#short story#flash fiction#original story#original fiction#anthropology#alternate history#unreality#creatures#stone age

71 notes

·

View notes

Note

Well can you explain Gender Ideology with who uses it and where? Can you show where I can find it? Can you describe it without conspiracy theory or recycled homophobia? You are welcome to try.

So I think some of the confusion might come from the language. I know you’re being facetious with this comment but anyway. I am literally a gender studies major so this will probably be more in depth than what you’re asking but maybe someone can benefit.

Gender Ideology™️ isn’t some sort of official concept and doesn’t have an agreed upon definition or foundational text like other social theories. It’s a way of conceptualizing sex and gender. Other analogous frameworks would be biblical gender roles, the Christian fundamentalist ideas of men and women, or postmodernist queer theory, something like Butler’s Gender Performativity.

You’re right that gender ideology is vague and non-specific and I think this is because of the interaction between academia, politics, medicine, and popular culture. Sure, academics and theorists influence society, but rarely in such a direct way (please feel free to correct me). For example, the American civil rights movement and women’s liberation movement had academic elements, but were not governed by how academics theorized race and sex, they were based on people’s lived experiences. Transgenderism, I think, is the opposite and somewhat of an escaped lab experiment. Towards the end of the 20th century, academics began to write about gender in more provocative and philosophical ways. Obviously, this was not the first time anyone had done this, but there was a huge shift in the way academic spaces thought about gender in the US after women achieved full legal rights (which didn’t happen until the 1970s btw). I’m sure the fact that women and gays/lesbians could finally be scholars and professors was important as well. Anyway, I might disagree with Butler, but her theory work is at least intellectually robust. And if you read Butler, it’s very obvious that she is first and foremost a philosopher, not a sociologist or an anthropologist, and this is clear when you hear her speak (which I’ve done btw). Contemporary transgenderism, as a social category, is a direct result of these theorists. There is a lot of misrepresenting or even rewriting history but “transgender” as we understand it today did not exist 20 years ago. We like to call people like Marsha P Johnson transgender, but he didn’t identify that way. He called himself a gay man, a cross dresser, a drag queen, a transvestite etc etc. TRAs often say “trans people have always existed” and homosexual behavior and gender nonconformity (and maybe even sex dysphoria) have always existed but trans as a concept undeniably has not. I could talk a lot more about historical falsehoods and Transgenderism but for the sake of getting to the point I’ll move on for now.

Gender ideology, is how groups like radfems refer to the Frankenstein monstrosity that is the framework Western left/progressives use today to think about gender and sex in order to be inclusive to transgender identifying people. The main ideas are that biological sex is not real and neither is sex-based oppression. It maintains that social and medical transition is necessary for transgender people to live, and that medicine is able to change someone’s biological sex (it can’t). Being transgender is not just dysphoria but some innate sense that someone’s soul is differently gendered than their biological sex (except biological sex is also somehow not real, one of many paradoxes). A woman is “someone who identifies a woman,” even though this phrase is completely meaningless. Because gender is not tied to biology sex, it relies on social ideas. As a result, gender ideology reinforces regressive gender roles and stereotypes, without which it cannot exist. 20 years ago we said boys can play with dolls and it doesn’t mean they’re gay because gender stereotypes aren’t innate and are very harmful, today “we” say that boys who play with dolls are actually girls and need to be given a pink makeover and put on medication. While society was beginning to move away from gender, gender ideology has brought it back to the center and gender is once again considered to be central to one’s identity (and personality) and maybe even the most important fact about them. For this reason “misgendering” and similar actions are considered violent attacks on personhood. Crucially, gender ideology converges with conservative gender ideals through its obsession with gender and performing femininity and masculinity.

#rad fem#rad fem safe#radical feminism#radical feminst#radical feminist safe#terfsafe#radblr#terfblr#radical feminists please interact#radical feminists do touch

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer History—chapter 09. Sexual and Gender Diversity in Native America and the Pacific Islands by Will Roscoe. part 2

Two Spirits in Native Tradition: Roles, Genders, Identities and Diversity cont.

In the twentieth century, ‘berdache’ “became the standard anthropological term for alternative gender roles among Native Americans. By the 1980’s, however, there was call for a change among scholars. In 1990, at a gathering of Native American and First Nations people, the term ‘two-spirit(ed)’ was coined. “Today, the term is used to refer to “both male-bodied and female-bodied native people who mix, cross, or combine the standard roles of men and women” (09-5).

The author acknowledges in a footnote that the term has its limitations (translation errors, and the fact that many tribes believe that all of us have the essence/spirit of male and female in us). But none of his reasons for these limitations match with my main critique both with the term two-spirit but mostly with the way it is often spoken of. Even within the acknowledgement of individuals who do not conform 100% to the Western concept of man or woman, the people are still fit into a binary. They are referred to as ‘male bodied’ and ‘female bodied’ two-spirited people.

To me, this often feels like an easy way for people to ‘short cut’ their understanding of native genders—as soon as they understand the way someone is sexed, they can still fit that person into a category, even if those categories are imperfect. Intersexuality is a ghost when topics of sex and gender arise. More and more, we understand that sex is not immutable, it is yet another social construction—the process of someone developing in utero and then continuing to grow and change in their lifetime is so complex that very often people do not fit neatly into either the distinct category of male or female.

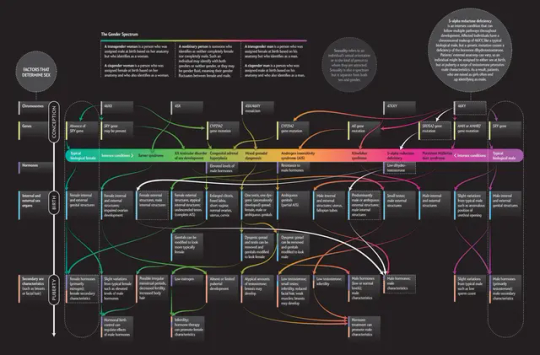

(See the link below for a better image of this)

Whether that is their very chromosomes, hormones, secondary or primary sex characteristics—all these things and more combine to create a person. A person whose very sex is unique to them, as their gender is unique to them. Who knows the true reality of the two-spirit’s biological sex? No one—unless they are given extensive expensive testing that has only recently become available.

The truth is that intersexuality is natural and is common in humans, even in the Western world with its biopolitical control and its dualisms. The reason two-spirit people were and are held so special is because they do not fit neatly into these categories. To me it feels a kind of modern colonial erasure to try and sex the bodies of people who often very clearly and blatantly blurred all barriers. It feels as if it misses the entire point of the term two-spirit, as least as I understand it. But, I have not read much into what other two-spirits (especially elders) think about this concept. “Two-spirit males have been documented in at least 155 tribes; in about a third of these a recognized status for females who adopted a masculine lifestyle existed as well”. (09-6) But as Roscue later adds, “absence of evidence cannot be taken as evidence of absence” (09-8).

In general, the lives of “native women have been overlooked […] and obscured by Euro-American sexual and racial stereotypes. Taking a broader view reveals that women throughout North American and the Pacific Islands often engaged in male pursuits, from hunting to warfare and tribal leadership, without necessarily acquiring a different gender identity” (09-8). Roscoe then offers some examples of Indigenous women being awesome. The author then lists examples of traditional terms for two-spirited people across various tribes and explains that many of them cannot be literally translated into gender binary terms like ‘man-woman’. “These terms have lead anthropologists, historians, and archaeologists to describe two-spirit roles as alternative or multiple genders” (09-6). In fact, “many native societies are capable of accommodating three, four, and possibly more genders, or having a gender system characterized by fluidity, transformation, and individual variation” (09-7).

The author discusses how two-spirit children were identified often as youth by the certain type of activities they liked to participate in. Oftentimes ceremonies ‘marked’ people with two-spirit status. He then goes on to discuss the other ways two-spirits lived in society. “In many instances, male and female two spirits were medicine people, healers, shamans, and ceremonial leaders” (09-8). Certain ceremonial functions were specific to two-spirits and they were often seen to hold great power (09-8). “Because two-spirits occupied a distinct gender status, their relationships were not viewed as being same-sex” (09-9). !!!! This feels so important for some reason!!

Sexual and Gender Diversity in Native Hawai’i

This section further emphases that indigenous peoples have had genders that go beyond male or female, man or woman and also that colonial violence is a tragedy. While I respect and love the people of Hawai’i and their struggles are so, so similar to Native Americans, I believe that the vast majority of Native Hawaiians do NOT consider themselves Native American (or American Indian or even just American) so my covering on this topic will be limited.

Roscoe speaks about the mahu stones that have extraordinarily sacred significance—these stones have a powerful history and connection to the mahu people (their gender diverse term). (This summary is literally so terrible and not at all a true representative of how important and beautiful this topic is, I apologize). Like the people, the stones faced colonization and were figuratively and then literally buried—“in the 1920s they were buried beneath a bowling alley” (09-15). They have since been reclaimed and are now being properly respected but, for the native peoples, “the Land inheres as sacred—beyond human perception and conception, beyond our capacities for belief and imagination—in and of itself” (09-15) and “If there were no humans on earth, they would still be sacred” (09-15). The stone’s spiritual power ‘has never been interrupted’ (09-15).

#queer theory#queer history#two spirit#two spirited#mahu#indigenous cultures#indigenous people#queer ecofeminism#queer politics#biology#intersex#queer ecology#ecofeminism#heteronormativity#colonialism#history#erotophobia#critical ecology#environmental politics#american history#indigenous history#human history

46 notes

·

View notes

Note

being a philosophy major sounds so cool but what sort of classes do u have to take? since i assume theres only so many philosophy and ethics classes haha. also, what do u think you’ll do with your degree?

ngl i wish it was like in the past when people were literal philosophers for a living lol that sounds so cool

You can still be a philosopher for a living! I'm aiming to either do that and/or be a writer. They're usually professors or research staff that earn grants from a university for writing papers or books. There are lots of famous modern philosophers that still just sort of sit around and say "well some things ARE and some things are NOT" and technically get paid for it! See David Chalmers, Peter Singer, Ted Sider, Susan Wolf, Eric Olson (I've had to cite all of them 😵💫).

You can also be a lawyer which is a super popular route. I aimed for it but it was NOT for me even though I need the money. Other people who follow their philosophy degrees are physicians, neuroscientists, writers, activists, anthropologists, stuff like that...

There's endless classes since philosophy is basically asking questions about things and then DESTROYING other people with FACTS AND LOGIC (but sometimes changing your worldview based on whatever is presented in class).

Philosophy isn't all ethics and studying dead guys. My favorite branch is metaphysics, which means I play with imaginary weird stuff like time travel, space, souls, aesthetics, so on. So there are lots of sub-genres of philosophy arguments: about politics, animals, ai, etc. Majors also usually have to take several courses on the history of philosophy (western and non western).

Formal logic or informal logic is usually required; it's basically math with letters and arguments, and super hard.

Literally terrifying and usually used in real philosophy 😔. They have played us for fools.

In the upper division classes, things usually get more niche and build on basic philosophy ideas. Philosophy is basically arguments upon refutations and arguments, built on one dialogue, lasting forever, starting with one guy in Greece. It's basically like an Avatar cycle of hardasses and people who hate women ☹️.

But really the main thing to do in philosophy classes is reading and writing. A lot. Lots and lots of concise, logical writing, which I was really bad at at first (because high schools train you to do research papers and long persuasive arguments) but am now okay at and I enjoy it. Some of these philosophers are really insane, but have somehow logical views on how the world works which I find really fun. Philosophy professors are also sometimes kooks and I love them.

I hope this answered your question and thanks for letting me ramble

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I.7.1 Do tribal cultures indicate that communalism defends individuality?

Yes. In many tribal cultures (or aboriginal cultures), we find a strong respect for individuality. As anthropologist Paul Radin pointed out, “respect for the individual, irrespective of age or sex” was one of “the outstanding features of aboriginal civilisation” as well as “the amazing degree of social and political integration achieved by them” and “a concept of personal security.” [quoted by Murray Bookchin, Remaking Society, p. 48] Murray Bookchin commented on Radin’s statement:

“respect for the individual, which Radin lists first as an aboriginal attribute, deserves to be emphasised, today, in an era that rejects the collective as destructive of individuality on the one hand, and yet, in an orgy of pure egotism, has actually destroyed all the ego boundaries of free-floating, isolated, and atomised individuals on the other. A strong collectivity may be even more supportive of the individual as close studies of certain aboriginal societies reveal, than a ‘free market’ society with its emphasis on an egoistic, but impoverished, self.” [Op. Cit., p. 48]

This individualisation associated with tribal cultures was also noted by historian Howard Zinn. He quotes fellow historian Gary Nash describing Iroquois culture (which appears typical of most Native American tribes):

“No laws and ordinances, sheriffs and constables, judges and juries, or courts or jails — the apparatus of authority in European societies — were to be found in the north-east woodlands prior to European arrival. Yet boundaries of acceptable behaviour were firmly set. Though priding themselves on the autonomous individual, the Iroquois maintained a strict sense of right and wrong.” [quoted by Zinn, A People’s History of the United States, p. 21]

This respect for individuality existed in a society based on communistic principles. As Zinn notes, in the Iroquois “land was owned in common and worked in common. Hunting was done together, and the catch was divided among the members of the village. Houses were considered common property and were shared by several families. The concept of private ownership of land and homes was foreign to the Iroquois.” In this communal society women “were important and respected” and families were matrilineal. Power was shared between the sexes (unlike the European idea of male domination). Similarly, children “while taught the cultural heritage of their people and solidarity with the tribe, were also taught to be independent, not to submit to overbearing authority. They were taught equality of status and the sharing of possessions.” As Zinn stresses, Native American tribes “paid careful attention to the development of personality, intensity of will, independence and flexibility, passion and potency, to their partnership with one another and with nature.” [Op. Cit., p. 20 and pp. 21–2]

Thus tribal societies indicate that community defends individuality, with communal living actually encouraging a strong sense of individuality. This is to be expected, as equality is the only condition in which individuals can be free and so in a position to develop their personality to its full. Furthermore, this communal living took place within an anarchist environment:

“The foundation principle of Indian government had always been the rejection of government. The freedom of the individual was regarded by practically all Indians north of Mexico as a canon infinitely more precious than the individual’s duty to his [or her] community or nation. This anarchistic attitude ruled all behaviour, beginning with the smallest social unity, the family. The Indian parent was constitutionally reluctant to discipline his [or her] children. Their every exhibition of self-will was accepted as a favourable indication of the development of maturing character…” [Van Every, quoted by Zinn, Op. Cit., p. 136]

In addition, Native American tribes also indicate that communal living and high standards of living can and do go together. For example, during the 1870s in the Cherokee Nation “land was held collectively and life was contented and prosperous” with the US Department of the Interior recognising that it was “a miracle of progress, with successful production by people living in considerable comfort, a level of education ‘equal to that furnished by an ordinary college in the States,’ flourishing industry and commerce, an effective constitutional government, a high level of literacy, and a state of ‘civilisation and enlightenment’ comparable to anything known: ‘What required five hundred years for the Britons to accomplish in this direction they have accomplished in one hundred years,’ the Department declared in wonder.” [Noam Chomsky, Year 501, p. 231]

Senator Henry Dawes of Massachusetts visited in 1883 and described what he found in glowing terms: “There was not a pauper in that nation, and the nation did not owe a dollar. It built its own capitol … and it built its schools and its hospitals.” No family lacked a home. In spite of this (or, perhaps, more correctly, because of this), Dawes recommended that the society must be destroyed: “They have got as far as they can go, because they own their land in common … there is no enterprise to make your home any better than that of your neighbours. There is no selfishness, which is the bottom of civilisation. Till this people will consent to give up their lands, and divide them among their citizens so that each can own the land he cultivates, they will not make much more progress.” [quoted by Chomsky, Op. Cit., p. 231–2] The introduction of capitalism — as usual by state action — resulted in poverty and destitution, again showing the link between capitalism and high living standards is not clear cut, regardless of claims otherwise.

Undoubtedly, having access to the means of life ensured that members of such cultures did not have to place themselves in situations which could produce a servile character structure. As they did not have to follow the orders of a boss they did not have to learn to obey others and so could develop their own abilities to govern themselves. This self-government allowed the development of a custom in such tribes called “the principle of non-interference” in anthropology. This is the principle of defending someone’s right to express the opposing view and it is a pervasive principle in the tribal world, and it is so much so as to be safely called a universal.

The principle of non-interference is a powerful principle that extends from the personal to the political, and into every facet of daily life (significantly, tribal groups “respect the personality of their children, much as they do that of the adults in their communities.” [Bookchin, The Ecology of Freedom, p. 115]). Most people today, used as they are to hierarchy everywhere, are aghast when they realise the extent to which it is practised, but it has proven itself to be an integral part of living anarchy. It means that people simply do not limit the activities of others, period (unless that behaviour is threatening the survival of the tribe). This in effect makes absolute tolerance a custom (the difference between law and custom is important to point out: Law is dead, and Custom lives — see section I.7.3). This is not to idealise such communities as they are must be considered imperfect anarchist societies in many ways (mostly obviously in that many eventually evolved into hierarchical systems so suggesting that informal hierarchies, undoubtedly a product of religion and other factors, existed).

As people accustomed to authority we have so much baggage that relates to “interfering” with the lives of others that merely visualising the situation that would eliminate this daily pastime for many is impossible. But think about it. First of all, in a society where people do not interfere with each other’s behaviour, people tend to feel trusted and empowered by this simple social fact. Their self-esteem is already higher because they are trusted with the responsibility for making learned and aware choices. This is not fiction; individual responsibility is a key aspect of social responsibility.

Therefore, given the strength of individuality documented in tribes with no private property, no state and little or no other hierarchical structures within them, can we not conclude that anarchism will defend individuality and even develop it in ways blocked by capitalism? At the very least we can say “possibly”, and that is enough to allow us to question that dogma that capitalism is the only system based on respect for the individual.

#anarchist society#practical#practical anarchism#practical anarchy#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The first women, the "feminids," began their labor activities without any teachers. They had to learn everything the hard way, sustained only by persistence, courage, wits, and collective ingenuity. They learned some things from close observation of living creatures in nature. As Mason sees it, both sexes probably learned in this manner, but as different sexes they learned different things.

About the male sex he writes: "In contact with the animal world, and ever taking lessons from them, men watched the tiger, the bear, the fox, the falcon- learned their language and imitated them in ceremonial dances." Then he adds:

But women were instructed by the spiders, the nest builders, the storers of food and the workers in clay like the mud wasp and the termites. It is not meant that these creatures set up schools to teach dull women how to work, but that their quick minds were on the alert for hints coming from these sources. . .. It is in the apotheosis of industrialism that woman has borne her part so persistently and well. At the very beginning of human time she laid down the lines of her duties, and she has kept to them unremittingly. (ibid., pp. 2-3)

Through these manifold labor activities, the minds of women developed at a more rapid pace than those of men. Already more alert because of their maternal functions, women speeded up their intellectual capacities through their ramified social production. Briffault writes: