#Śūnya

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Untold Status of Women in the Institution of Marriage: Understanding through the Philosophical Lens

Dr. Jayanti P Sahoo and Dr. Aparna Dhir Khandelwal (Continued..) ‘लड़की लोगों के लिए पूरी दुनिया सोचती है, बस यह नहीं पूछते कि वो क्या सोच रही है’ (A dialogue from the movie ‘Pagglait’ released in 2021) Passing through the 21st century, women feel more confident and independent in terms of thoughts, choices, and finances but when it comes to the institution of marriage why our own traditional…

View On WordPress

#Advaita Vedanta#Ananda#Culture#Dharma#Mahabharata#Nyaya#purana#Rama#Ramayana#Shruti#Sita#Smriti#Svadharma#Vedas#Śūnya

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ted Lasso: All right, guys, listen up. The things in the world originate only because of their relation to other things. That means they have no essence or existence of their own. Their true nature is that they are “śūnya" or "empty”.

Coach Beard: Emptiness isn’t their true nature, either.

Ted Lasso: Say what now?

Coach Beard: Emptiness isn’t truer than the false natures of the things that are empty.

Ted Lasso: Now how the hell does that work?

Coach Beard: Emptiness did not arise independently, either. Its existence is also dependent upon its relation to other things. If there was nothing to be empty, then there would be no emptiness.

Dani Rojas [excitedly, like a little kid with a new toy]: if all things are empty, then emptiness itself must be empty, too!

Ted Lasso: now that right there is what we call “insight beyond insight” back in Kansas

Higgins: Er, wouldn’t that make nirvana empty as well? And if it’s empty, doesn’t that mean there’s no reason to try to achieve it?

Jan Maas [unfiltered Dutchman]: Thoughts like those are why you’re still stuck in samsara.

#ted lasso#nagarjuna#buddhism#commit to the bit#original post#please don’t expect my satirical ted lasso post to give you complete and contextualized information#my educational nonfiction is thoroughly researched#but my bits are just bits#if anyone wants introductory level info about buddhist emptiness#watch the video on nagarjuna by let’s talk religion#you can find intermediate information on the stanford encyclopedia of philosophy#and the nichiren library entry on non-substantiality

943 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ecumenismo e Diversidade Religiosa no Laghu-Yoga-Vāsiṣṭha

Em vários pontos ao longo do Laghu, se encontra a afirmação autorreflexiva e explícita de que todas essas escolas filosóficas e teológicas distintas, e até mesmo concorrentes, estão ensinando uma e a mesma verdade ou realidade em suas próprias maneiras, embora utilizando seus próprios vocabulários distintos. “[há] um certo ser… que é quieto, profundo, nem luz nem escuridão, onipresente, não manifesto, sem nome. Para os propósitos práticos da fala (vyavahārārthaṃ), o nome desse eu exaltado (ātman) é imaginado pelos sábios como sendo ‘verdade/ordem cósmica’ (ṛta), ‘ātman’, ‘o Altíssimo’ (para), ‘brahman’, ‘realidade’ (satyam), e assim por diante.”

Além desses termos particulares para a Realidade última, todos os quais são rotineiramente empregados em vários contextos hindus, o Yoga-Vāsiṣṭha também estende as referências ao reino do pensamento budista (e até mesmo jainista e materialista carvāka): Esta [consciência (cit)] que escapa à designação positiva e que não está dentro do alcance das palavras… é o que é śūnya (“vazio”) para os proponentes [budistas] de śūnya (ou seja, praticantes de Madhyamaka), o mais excelente brâmane entre os conhecedores [Vedāntin] de brâmane (brahmavid), aquilo que é “somente consciência” (vijñāna-mātra) para os conhecedores de vijñāna (ou seja, budistas Yogācāra), puruṣa para aqueles que sustentam a visão Sāṃkhya, o Senhor (īśvara) para os professores de Yoga, [e] Śiva para os Śaivas.

Como o Laghu é uma obra de “sabedoria” narrativa em vez de um tratado dialético sistemático, Abhinanda nunca é compelido a pensar ou elaborar as implicações filosóficas de declarações como essas. Como tal, é difícil saber exatamente o que tirar das afirmações de Abhinanda para esse efeito. Por um lado, elas emprestam ao Laghu um ar ecumênico pronunciado, de certa forma, sugerindo a possibilidade de que tradições religiosas divergentes ofereçam caminhos diferentes para o mesmo objetivo. Slaje, por outro lado, aponta as várias maneiras pelas quais o Yoga-Vāsiṣṭha eleva sua própria visão metafísica sobre aquelas de outras tradições, o texto em um ponto reivindicando para si o título de “posição final [abrangendo as] posições de todos [os outros Śāstras]” (ou então a “posição final das posições finais de todos [os outros Śāstras]”) (sarva-siddhānta-siddhānta); eu apenas acrescentaria que esta última observação não é necessariamente incompatível com a primeira. A noção de saṃkalpa mais uma vez se torna relevante a esse respeito, pois o Yoga-Vāsiṣṭha sugere em vários pontos que a principal razão para as visões e terminologias divergentes de diferentes pensadores e tradições filosóficas é que eles imbuem seus termos com “significados baseados em [as limitações de] sua própria imaginação (saṃkalpa)”, ou então, “não tendo [ainda] alcançado o conhecimento perfeito”, eles “baseiam sua disputa nas aparências [produzidas por sua] própria imaginação (sva-vikalpa)”.

Independentemente das conclusões limitadas que somos capazes de tirar dessas declarações relativamente isoladas, algumas tendências gerais são claras. Por um lado, apesar de qualquer "ecumenismo" que Abhinanda possa ou não ter pretendido com afirmações como essas, o Laghu não é um tipo de texto "vale tudo": ele tem uma visão metafísica e soteriológica clara, e uma noção distinta e consistente de verdade e falsidade, que de alguma forma coexiste com essas afirmações da legitimidade de outras tradições filosóficas e léxicos. Essa perspectiva metafísica, como observado acima, provavelmente ressoou com as inclinações wujūdī de muitos pensadores muçulmanos modernos primitivos dentro (e fora) da corte Mughal. Por outro lado, a simpatia geral do Laghu por alguma iteração de uma ideia de “múltiplas articulações de uma verdade compartilhada e universal” — mesmo que, em última análise, talvez, uma supersessionista — provavelmente também ressoou com certos objetivos e interesses políticos da corte Mughal, como exibido em iniciativas como o movimento de tradução Mughal. No entanto, mesmo o ecumenismo incipiente do Laghu carrega certas complementaridades discutíveis com a estrutura para conceituar a diversidade religiosa que prevalece dentro do Jūg Bāsisht persa e, portanto, pode muito bem ser uma parte do que atraiu o interesse muçulmano para o Laghu-Yoga-Vāsiṣṭha em primeiro lugar.

Translating Wisdom: Hindu-Muslim Intellectual Interactions in Early Modern South Asia - Shankar Nair

#laghu yoga-vasistha#hinduismo#budismo#traducao-en-pt#translatingwisdom-sn#shivaísmo#samkalpa#império mogol#islam#cctranslations

0 notes

Text

#1154 Where did 0 come from?

Where did 0 come from? The concept of the modern zero was invented in India, but the idea of a placeholder for numbers was thought up by the Mesopotamians. We take the idea of the number 0 for granted. We use it regularly throughout the day (probably) and many of the things we use would not function without it. It is a part of the programming for your phone and for the algorithm that pushes my articles down to the darkest parts of the web. However, that concept has only existed since relatively recently. That is not so strange when you think about it because zero means nothing, and why would you have a number that means nothing? The very concept of numbers is to count things. You would never count nothing because there is nothing there to count. Something similar to zero became necessary when counting systems changed. Early counting systems simply counted the number of things that there were. They used marks or symbols. One mark for one thing, two marks for two things, and so on. However, humans can only rapidly count groups of four things. Any more than that and we can’t do it quickly. That is why a lot of the early counting systems, like Roman numerals, use marks for one, two, three, and then change to other symbols. I, II, III, IV, V, VI etc. There is no need for a zero in a system that just counts what is there. The problem with these systems is that numbers get very long. An easier way is the system that we use today. You have the numbers 1 to 9, and then you have columns for the place values. The first column is for the units. Everything up to nine. The next column is for the tens. Everything up to 90. And the last column is for the hundreds. Everything up to nine hundred. This makes numbers shorter, but you have the problem of what to write when there is no value in that column. Today, we write a zero, but in the early days of counting, the Mesopotamians just left a space. This is not a zero, but it is the first instance of nothing being written. This was approximately 4,000 years ago. The Babylonians came next. They used two small wedges to indicate no values in one of the numerical columns. This is still not a number, though. The Mayans also used a symbol that looked like a zero as a placeholder, but this was also not a separate number. Zero as a placeholder spread through other civilizations as well, but it was never an actual number. The first time zero was used as a number was in 628 AD in India. It probably evolved in India independently and started out as a concept of emptiness, or of nothingness. It was called śūnya, and the idea first appears in India in 458 AD. The rules for the use of zero were set down in 628 AD by an astronomer and mathematician called Brahmagupta, but he talks about zero as though it is already known about, which implies that it appeared before his time. He just clarifies the rules. The concept of zero went from India to Arabia, where it was considered a regular number. In Arabic, zero was called sifir, which was a translation of the Hindi śūnya, which meant empty. From Arabia, it went into Europe via Venice. In Italian, sifir became zefiro, which later became zero. The symbol for zero also evolved over time. Early civilizations used hash marks or other marks to indicate a space. In Mayan, it was portrayed as a tortoise shell shape, which is roundish. In ancient Greece, it was written as a small circle underneath a horizontal line. It started out as the Greek letter omicron (ό), and ended up as a smaller circle and a longer line. In China, it was written as a O, but it might just have been a square with rounded corners. In the early Indian manuscripts, zero was written as a solid black dot. There are some examples of zero being written as a circle in India, but it was more often a dot. When zero travelled to the Middle East and then moved up into Europe it gradually became a larger circle. This was probably because a dot could be mistaken as punctuation or easily missed. Also, as zero became a number in its own right, it was written the same size as all of the other numbers. And this is what I learned today. If you liked that, try these: - #93 Is it possible to get absolute zero? - #569 What is the oldest stone circle in the world? - #610 Why do we say eleven and twelve, and first, second and third? - #650 Why is 0 longitude in London? - #499 How does computer encryption work? Sources https://www.history.com/news/who-invented-the-zero https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/what-is-the-origin-of-zer https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2017-09-14-earliest-recorded-use-zero-centuries-older-first-thought https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bakhshali_manuscript https://www.cbc.ca/radio/ideas/zero-number-series-ideas-cbc-1.6977700 https://www.livescience.com/27853-who-invented-zero.html https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/0 Photo by Jakub Zerdzicki: https://www.pexels.com/photo/calculator-20552602/ Read the full article

1 note

·

View note

Text

INVERARE IL VUOTO

di Luca Rudra Vincenzini “Śūnya-bhāvanāt parayā śūnyayā śaktyā”,”attraverso la suprema energia del vuoto (parayā śūnyayā śaktyā) si invera il vuoto (śūnya-bhāvanāt)”, Vijñānabhairavatantram. Quando scendi profondamente in meditazione, nel retro della coscienza, dietro i pensieri passeggeri che ballano sul palcoscenico, passa lenta la nuvola del vuoto: timida, calma, delicata, sottile. Se la fai…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

pṛṣṭa śūnyaṁ mūla śūnyaṁ yugapad bhāvayec ca yaḥ | śarīra nirapekṣiṇyā śaktyā śūnya manā bhavet || 44 ||

prishtha-shoonyam moola-shoonyam yuga-pad bhaavayet cha yah shareera nir-a-pekshinyaa shaktyaa shoonya–manaa bhavet

Your back is a gateway to the sky. The celestial dance, The story of space and time, Is coded in the spine. Attend simultaneously To the area around your tailbone, Vibrating with luminous space, And to the spine as a channel Gushing with radiant emptiness. Here, Where particles flash in and out of existence, Is the origin of mind.

Lưng của bạn là một cửa ngõ vào bầu trời. Vũ điệu thiên đường, Câu chuyện về không gian và thời gian Được mã hóa ở cột sống. Đồng thời chú ý Đến khu vực xung quanh xương cụt của bạn, Rung động không gian sáng suốt, Và đến cột sống như một nguồn nước Tràn ngập sự trống rỗng rạng ngời. Đây, Nơi các hạt lóe lên và biến mất, Là nguồn gốc của tâm trí.

0 notes

Text

"Eu sou essencialmente Brahman. De mim veio o mundo composto de Prakr̥ti e Puruṣa, o vazio (śūnya) e a plenitude (pūrṇa). [...] Eu sou o mundo inteiro [...] Eu sou incriado e o criado. Acima, abaixo e envolta são Eu."

~ Devī Upaniṣad.

0 notes

Text

O significado do Mahāmantra Hare Kṛṣṇa no Rādha Tantra.

Esse é o maior segredo do nome do Senhor Hari:

“HA” é Śiva. “R” é a Suprema Deusa Tripurā, a encarnação dos 10 Vidyā-s (conhecimentos). Ó, Aquele que é próspero na observância! “E” é o Akṣara-Yonī (Eterna Vulva da Deusa) em Si.

[…]

“HA” também significa Aquele que é da forma da vacuidade (śūnya-svarūpa) e “RE” é Ela que toma a forma de Saguṇa-Īśvara (Deus com Atributos). Hari é Tripurā em Si…

[…]

Ó, melhor dos filhos! “KR̥ṢṆA KR̥ṢṆA” é Mahāmāyā (a Grande Māyā), o mundo (Jagat) em Si! “HARE HARE” é a Deusa na forma de Śiva e Śakti (Śiva-Śakti-Svarupiṇī).

[…]

As palavras “HARE RĀMA” simbolizam a Suprema Deusa que concede a liberação (Mokṣā). “RĀ” é Tripurā acompanhada do néctar da Beatitude. “MA” é Mahāmāyā, a Eterna Yoginī de Rudra.

[…]

O Visarga é a Suprema Kuṇḍalinī-Śakti, as palavras “RĀMA RĀMA” são Śiva e Śakti. As palavras “HARE HARE” contém duas Śaktis.

[…]

- Śrī Śrī Rādha Tantraṁ.

0 notes

Text

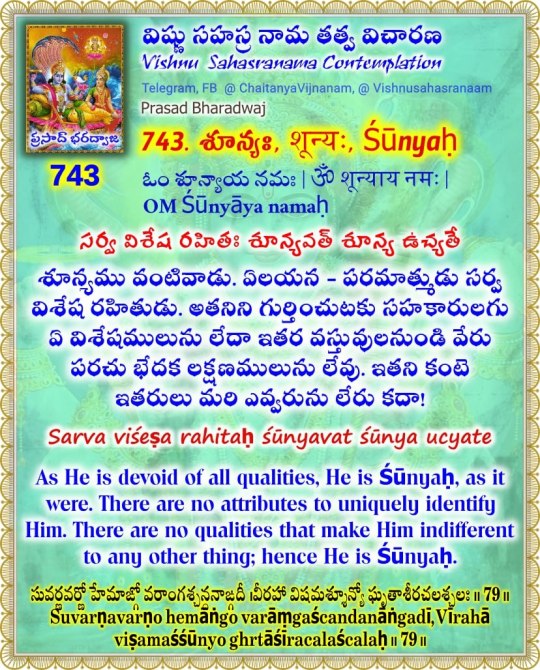

విష్ణు సహస్ర నామ తత్వ విచారణ - 743 / Vishnu Sahasranama Contemplation - 743

🌹. విష్ణు సహస్ర నామ తత్వ విచారణ - 743 / Vishnu Sahasranama Contemplation - 743🌹 🌻743. శూన్యః, शून्यः, Śūnyaḥ🌻 ఓం శూన్యాయ నమః | ॐ शून्याय नमः | OM Śūnyāya namaḥ

సర్వ విశేష రహితః శూన్యవత్ శూన్య ఉచ్యతే

శూన్యము వంటివాడు. ఏలయన - పరమాత్ముడు సర్వ విశేష రహితుడు. అతనిని గుర్తించుటకు సహకారులగు ఏ విశేషములును లేదా ఇతర వస్తువులనుండి వేరు పరచు భేదక లక్షణములును లేవు. ఇతని కంటె ఇతరులు మరి ఎవ్వరును లేరు కదా!

సశేషం...

🌹 🌹 🌹 🌹 🌹

🌹. VISHNU SAHASRANAMA CONTEMPLATION- 743🌹 🌻743. Śūnyaḥ🌻 OM Śūnyāya namaḥ

सर्व विशेष रहितः शून्यवत् शून्य उच्यते / Sarva viśeṣa rahitaḥ śūnyavat śūnya ucyate

As He is devoid of all qualities, He is Śūnyaḥ, as it were. There are no attributes to uniquely identify Him. There are no qualities that make Him indifferent to any other thing; hence He is Śūnyaḥ.

🌻 🌻 🌻 🌻 🌻

Source Sloka

सुवर्णवर्णो हेमाङ्गो वरांगश्चन्दनाङ्गदी ।

वीरहा विषमश्शून्यो घ��ताशीरचलश्चलः ॥ ७९ ॥

సువర్ణవర్ణో హేమాఙ్గో వరాంగశ్చన్దనాఙ్గదీ ।

వీరహా విషమశ్శూన్యో ఘృతాశీరచలశ్చలః ॥ 79 ॥

Suvarṇavarṇo hemāṅgo varāṃgaścandanāṅgadī,

Vīrahā viṣamaśśūnyo ghrtāśīracalaścalaḥ ॥ 79 ॥

Continues....

🌹 🌹 🌹 🌹🌹

0 notes

Text

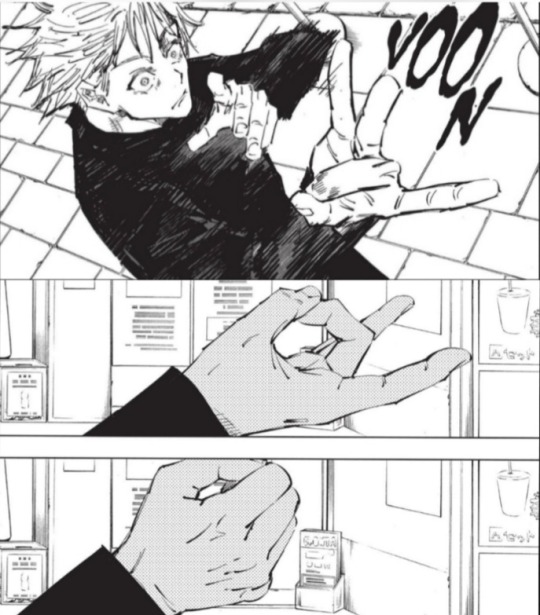

This hand gesture is called "shunya mudra"

Shunya (śūnya) means empty, void, nothing, zero, hollow and is also used to referred to the sky or heaven (mudra means gesture or seal)

#i refuse to believe its a coincidence#jjk#jujutsu kaisen#gojo satoru#jjk gojo#jjk satoru#still didnt find any Buddhism thing explaining sukuna and megumi's hand gesture domain expansion#but ive figured out hollow purple so im happy

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

"When we look at the meaning of emptiness [in Buddhism]..., the Sanskrit word is śūnyatā. One of the literal meanings of śūnya is 'empty' and another one is 'zero.' In Indian mathematics, the zero sign is śūnya, but it has quite a different meaning from 'zero' in the west. When we think of zero, we think 'nothing,' but in India the circle of śūnya, or zero, means 'fullness,' 'completeness,' or 'wholeness.' In the same way, 'emptiness' does not mean 'nothingness,' but rather 'fullness' in the sense of full potential — anything can happen in emptiness and because of emptiness...

In a sense, the teachings on emptiness have a lot of parallels with quantum physics. Quantum physicists tell us that there is really no world out there, nor a body. There is actually not much, if anything. They are still looking for something, because it sounds better and we do not have to be scared that there is really nothing at all to hold on to. When physicists talk about a quantum field, it almost entirely consists of space and some energy in it, not even particles. They may talk about 'particles,' but this term does not refer to any kind of substance anymore, just statistical probabilities of relationships.

This is also very much what emptiness is about, meaning that there is no single phenomenon whatsoever that exists independently on its own. The description of a quantum field is very much like the Heart Sūtra’s formula 'Form is emptiness. Emptiness is form. Emptiness is nothing other than form, and form is nothing other than emptiness.' Everything is interrelated and constantly changing in every moment, yet entirely ungraspable.

In quantum physics, they have found that if one electron or one subtle particle on one end of the universe changes, another one at the other end of the universe also changes. Thus, it is not that this principle of interdependence is limited to a certain domain or area in space; it is truly infinite and all-pervasive."

- Karl Brunnhölzl, from The Heart Attack Sutra: A New Commentary on the Heart Sutra

#karl brunnhölzl#quote#quotations#heart sutra#emptiness#sunyata#zen#science#physics#quantum mechanics#metaphysics#identity#philosophy#math#mathematics#zero#dependent origination

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Analisando o Laghu-Yoga-Vasistha

(Este trecho analisa uma citação do Laghu no contexto de Advaita Vedanta. Para informações básicas sobre o livro, clique aqui. Para a tag geral do Laghu, clique aqui.)

Quando, assim como o vento encena o poder pulsante da vibração (spanda-śakti), o eu (ātman), inteiramente por si só, de repente encena um poder (śakti) chamado “desejo/imaginação” (saṃkalpa), então [este] eu do mundo, fazendo-se como se estivesse na forma de uma aparência discreta (ābhāsa) que abunda no impulso em direção ao desejo/imaginação (saṃkalpa), torna-se mente (manas). Este mundo, que é apenas puro desejo/imaginação (saṃkalpa-mātra), desfrutando da condição de ser visto (dṛśya), não é real (satyam) nem falso (mithyā), ocorrendo como a armadilha de um sonho.

Abhinanda afirma aqui que o Ser/consciência puro sofre a aparência (ābhāsa) de uma transformação, mas sem suportar nenhuma transformação real, pois o poder da pulsação do ātman (spanda) o faz se manifestar “como se” em uma nova forma ou aparência, a saber, os objetos do mundo fenomenal. Agora, ābhāsa é um termo empregado tanto pelos Śaivas não-dualistas da Caxemira quanto pelos Advaitins, além de várias outras tradições sânscritas: as escolas budistas Yogācāra (e, em menor grau, Madhyamaka) foram talvez as primeiras a desenvolver o conceito em detalhes, enfatizando os ābhāsas do mundo como, de fato, falsas aparências, construídas pela mente (citta), que os dota com a aparência de substancialidade objetiva, quando na realidade tais objetos são apenas “vazios” (śūnya) ou “somente mente” (citta-mātra). Não pode haver dúvidas de que essas primeiras valências budistas do termo ābhāsa persistem na literatura Yoga-Vāsiṣṭha, que nunca se cansa de afirmar enfaticamente o mundo fenomenal como a construção de nossas próprias mentes (manas, citta) e nossas imaginações cognitivas (kalpa, saṃkalpa, vikalpa); de fato, o texto ecoa explicitamente o vocabulário budista do mundo como “somente mente” (manomātra, citta-mātra) em repetidas ocasiões. Por exemplo: “tudo o que surge é [apenas] a mente, como uma cidade nas nuvens. Tudo isso que aparece, uma autoexpansão chamada ‘o mundo’ (jagat), não é mais do que erro (bhrānti);” “este mundo inteiro é somente mente (manomātra) . . . a mente é o céu, a terra, o vento. De fato, a mente é grande;” “tudo isso é a mente (manas) que brilha (sphurati) dentro de [suas] criações (sṛṣṭi).”

Similarmente, a implantação do Advaita Vedānta de ābhāsa também enfatiza a “aparência” do mundo como, de fato, a falsa aparência (bhrānti) de um mundo imaginado, o produto da ignorância (avidyā) que não possui nenhuma realidade substancial própria. Talvez a diferença central entre os usos budistas e advaitianos do termo, no entanto, seja que, enquanto as invocações budistas de ābhāsa são primariamente destinadas a provocar um reconhecimento da natureza efêmera e dependente da mente dos objetos fenomenais, o Advaita acrescenta algo mais ao relato: uma vez que as semelhanças fenomenais são reconhecidas como ilusórias, o terreno é limpo para o reconhecimento de uma entidade adicional que é, em última análise, real, “escondendo-se atrás” dessas falsas aparências o tempo todo, a saber, o Eu puro (ātman) ou Realidade absoluta (brahman). Às vezes, o Laghu também habita um modo semelhante, varrendo o transitório e efêmero para deixar apenas o absoluto como remanescente, por exemplo: “todas essas coisas móveis e imóveis do mundo… são destruídas como um sonho é destruído em um sono profundo e sem sonhos (suṣupti). Então, um certo ser permanece que é imóvel, profundo, nem luz nem escuridão, onipresente, imanifesto, sem nome. Para os propósitos práticos da fala (vyavahārārthaṃ), o nome desse eu exaltado (ātman) é imaginado pelos sábios como ‘verdade/ordem cósmica’ (ṛta), ‘ātman’, ‘o Altíssimo’, ‘brahman’, ‘realidade’ (satyam), e assim por diante.”

E assim, para o Advaita Vedānta, as “semelhanças” (ābhāsas) que constituem os objetos do mundo fenomenal são, na melhor das hipóteses, meramente convencionalmente reais (vyāvahārika), mas não em última análise (pāramārthika), sendo ātman a única Realidade última; em vários momentos, o Laghu fica feliz em ecoar mais ou menos esse relato. Além disso, a insistência do Advaita Vedānta de que a Realidade/Eu último (brahman/ātman) é desprovida de toda mudança e transformação significa que essas falsas semelhanças do mundo não podem ser diretamente fundamentadas no imutável brahman, mas sim, devem ser fundamentadas na “ignorância” (avidyā). Agora, a ignorância em si é apenas tenuamente conectada com brahman, um pouco como luz e sombra, sendo a luz (brahman) aquilo que imediatamente destrói a sombra da ignorância ao contato. Portanto, os Advaitins predominantemente descrevem os dois como muito mais opostos do que relacionados; ābhāsas, portanto, não “vêm” realmente de brahman, por esse motivo, mas são, em vez disso, instanciações e produtos do oposto de brahman, a ignorância. Para os Śaivas da Caxemira não dualistas, em contraste, a noção de ābhāsa é empregada para um efeito notavelmente divergente: com a adoção de um “absoluto infinito que se manifesta ativamente por meio da finitude e transitoriedade dos fenômenos que mudam perpetuamente em consonância com a atividade do absoluto” — isto é, os “pulsos” ou “vibrações” (spanda) da Consciência pura — o resultado é uma concepção de ābhāsa “não… no sentido [Advaitin] de semelhança, mas como a forma manifesta do absoluto”, em outras palavras, menos como a relação entre luz e sombra, e mais como a relação entre o sol e os vários raios individuais que se espalham a partir dele. Nesta visão de Kashmiri Śaiva, há, portanto, uma continuidade ontológica muito mais pronunciada — na verdade, uma identidade — entre aparência e Realidade, uma percepção que a literatura Yoga-Vāsiṣṭha fica muito feliz em ecoar em repetidas ocasiões: “Aquele que considera a multidão de raios como sendo distinta do sol, para ele, essa multidão é de fato algo diferente do sol… [mas] aquele que considera os raios como sendo indistintos do sol, para ele, esses raios são [o mesmo que] o sol. Ele (ou seja, o último) é dito ser desprovido de dúvida;” “assim como a multiplicidade abundante, espalhando-se como ondas e semelhantes, aparece no oceano flutuante sem ser distinta dele… da mesma forma, este [mundo] abundante e multitudinário — que é consciência sozinha e indistinto dela — se manifesta no oceano da consciência;” “‘o mundo (jagat) é, de fato, brahman’, desta forma, todo este [mundo] é conhecido através do conhecimento da realidade (sattva).” O Laghu, consequentemente, em alguns momentos habita a concepção Advaitin de ābhāsas como fugazmente irreal como um sonho evanescente, e, em outros momentos, incorpora uma insistência semelhante à de Kashmir Śaiva nas aparências do mundo como as epifanias reveladoras da consciência pura.

Translating Wisdom: Hindu-Muslim Intellectual Interactions in Early Modern South Asia- Shankar Nair

#laghu yoga-vasistha#hinduismo#budismo#traducao-en-pt#translatingwisdom-sn#advaita vedanta#vedanta#sânscrito#shivaísmo#caxemira#abhasa#brahman#atman#cctranslations

0 notes

Text

Marathi Numbers, 0-10

The names of numbers in Marathi are derived from Sanskrit by way of Prakrit, so their pronunciations may be very familiar to speakers of other Indo-European languages.

Inspired by @bongboyblog‘s post on Bengali numerals.

० - शून्य [śūnya] zero

१ - एक [ek] one

२ - दोन [don] two

३ - तीन [tīn] three

४ - चार [cār] four

५ - पाच [pāč] five

६ - सहा [sahā] six

७ - सात [sāt] seven

८ - आठ [āṭh] eight

९ - नऊ [naū] nine

१० - दहा [dahā] ten

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

To reject delusion and accept truth is just another form of delusion, Yung Chia says later, for such discrimination between rejecting and accepting is still dualistic; one who practices in this way mistakes a thief for his own son. The Way is not a matter of escaping delusion, because there is nowhere to escape except to an equally delusive quietism. It is rather a matter of liberating delusion, as Dōgen might say. What distinguishes liberated delusion is the utter freedom of the mind to dance freely from one śūnya thing to another, from one set of concepts to a different and perhaps contradictory set. The difference is not necessarily in the concepts themselves—they may be the same—but how effortlessly the mind is able to play with them without getting stuck. To the extent that the mind thinks there is an objectifiable Truth (whether already grasped or not yet), or to the extent that it thinks dwelling in blankness of mind is the Truth, this freedom is not realized: the mind trips over itself, sticks at this, jumps to that, and doesn’t want to let go because it still understands its fundamental task as finding and dwelling in a secure “home” for itself.

David R. Loy, Nonduality in Buddhism and Beyond

#text#quote#David R Loy#Nonduality in Buddhism and Beyond#Buddhism#Dogen#Zen Buddhism#Zen#nonduality#duality#dualism#truth#delusion#quietism#sunya#nonattachment#insecurity

110 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Śūnyatā" (Sanskrit), or emptiness. -śūnya means "zero," "nothing," "empty" or "void" and derives from the root śvi, meaning "hollow" -tā means "-ness" This mode is called emptiness because it's empty of the presuppositions we usually add to experience to make sense of it: the stories and world-views we fashion to explain who we are and the world we live in. Although these stories and views have their uses, the Buddha found that some of the more abstract questions they raise — of our true identity and the reality of the world outside — pull attention away from a direct experience of how events influence one another in the immediate present. Thus they get in the way when we try to understand and solve the problem of suffering.

Thanissaro Bhikku

1 note

·

View note