This blog features content from archival and manuscript collections at Pitt’s Archives & Special Collections, one of the largest repositories for information on western Pennsylvania and Pittsburgh history. It is also the home for historical records for the University of Pittsburgh. Be sure to check out our other blog, Rare Books @ Pitt, for posts on rare books and student projects.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Life and Business in 19th Century Allegheny County, Pennsylvania: The Daily Diaries of Moses Chess

This post was written by Ben Snyder, a graduate Library and Information Sciences student in the School of Computing and Information Sciences and 2021-2022 Pitt Partner Graduate Intern for Archives & Special Collections.

Moses Chess (1820-1895) was a farmer, businessman, and land surveyor who lived in Chartiers Township, Allegheny County (now the Westwood & Oakwood neighborhoods of Pittsburgh). Chess had a busy life, filled not only with his work and business, but also with meetings for the various societies he was a member of, including the Western Pennsylvania Exposition Society and the Allegheny County Agricultural Society, and visits with many friends and family. As a means of keeping track of and recording all this, Chess consistently kept a daily diary for most of his adult life, beginning a new one each year at least as early as 1853 and continuing until the year of his death in 1895.

Chess’s diaries typically follow a routine form, briefly recording anyone who’s visited, society meetings, transactions, work, and the daily weather. While often businesslike, his personal life also enters his writings; in his younger years in the 1850s he typically records his regular church attendance, including who preached at the service and what Bible verses were used. He’ll also note such events as picnicking on the 4th of July and his children’s first day of school. These diaries thus offer a unique perspective on Pittsburgh and its surrounding areas in the latter half of the 19th century—in relation both to its economic conditions and the rhythms of daily life for someone in Chess’s social position.

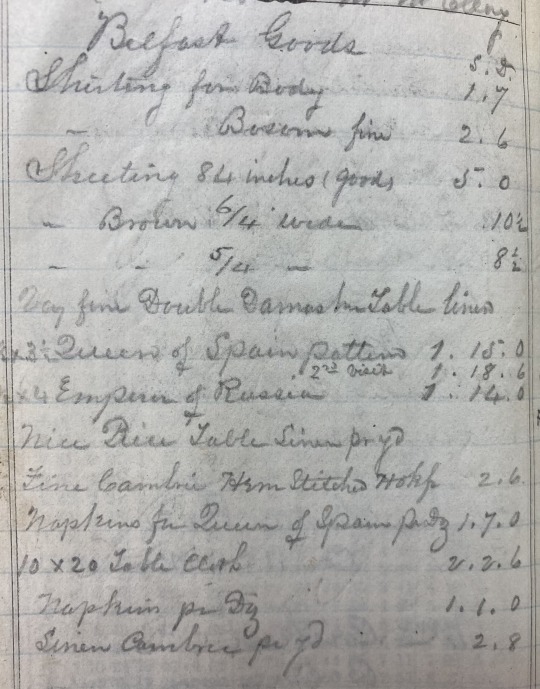

A more unique diary in this collection is the one Chess kept specially for a trip he took to Europe in the summer of 1867. After his initial voyage across the Atlantic, he was able to travel quickly by train (representing a still fairy early example of this industrial-era tourism), visiting cities and towns in Ireland, England, Scotland, France and Switzerland over the course of three months. During his trip Chess showed his commercial mindset, recording information on the commodities he encountered in cities like Belfast, Liverpool, or London, with special attention to textile goods.

(Above) A list of goods and their prices that Chess took note of in Belfast, from “European Travel Diary, April 2, 1867 - August 25, 1867,” Moses Chess Diaries and Papers, AIS.2021.04, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Chess stayed for a few weeks in Paris during the Exposition Universelle of 1867, the second world’s fair in the city. The international character of the event inspired some reflection on Chess’s part, writing on June 14th: “One peculiarity I sensed was that each nation (except perhaps Americans) admired the productions of their own country more than that of any other.” In an earlier entry, on June 12th, he complains of the lack of English speakers in Paris and the high prices charged at restaurants, sounding not too different from a modern-day tourist.

1867 wasn’t the only time Chess recorded his travels. In 1855, he took multiple trips sailing the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, transporting freight. These trips would often culminate in Chess staying in New Orleans for a couple days, where he’d record some observations. On January 19th of 1855, during one of these stays in New Orleans, he notes attending a slave auction and minstrel show: brief reminders of the racist society he was operating within.

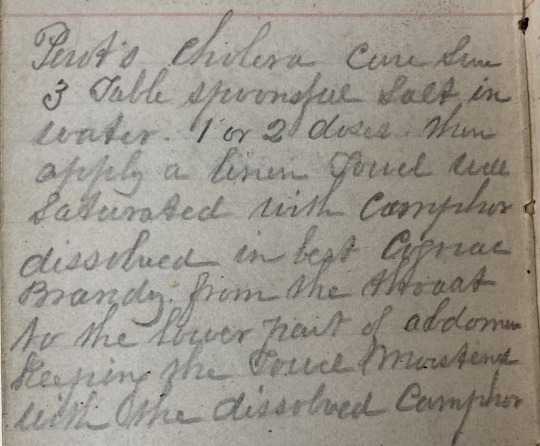

While much of Chess's diary during these sailing trips represents his typical attention to work and business—mostly dedicated to noting how adventitious sailing conditions are and when and where he’s discharging freight—his diary also has brief moments that indicate some of the real risks involved in such mercantile undertakings at the time. In a series of entries from May 24th to the 26th he notes burying many people due to a cholera outbreak. At the end of the diary for that year, in the “Memorandum” section, he would write down the directions for a cholera treatment.

(Above) A treatment for cholera, from “Daily Diary, 1855,” Moses Chess Diaries and Papers, AIS.2021.04, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

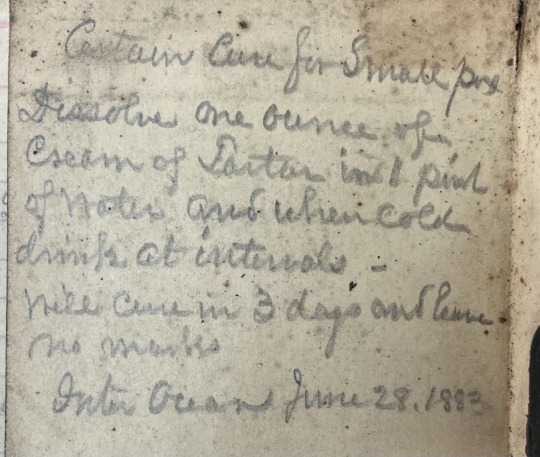

His diaries over the years contain many similar recipes and directions for medical treatments, for such things as diarrhea, smallpox, and diphtheria. These could be valuable evidence for popular medical treatments in the U.S. in the latter half of the 19th century—but they also give hints of the more human vulnerabilities and struggles lying behind these otherwise routine diaries.

(Above) A treatment for smallpox, from “Daily Diary, 1883,” Moses Chess Diaries and Papers, AIS.2021.04, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Evidence of illness can appear in other ways as well. One of the unexpected interests of these diaries for me has been when Chess wasn’t writing any entries—sometimes for over a month, although only rarely. These incidents often seem to represent a period of illness. For instance, his diary for 1889 suddenly ends early on December 11, with next year’s diary only picking back up on January 27th with Chess noting a doctor had advised him “to make a trip south as soon as possible.” Chess didn’t seem to heed this advice, continuing with his business—and writing 6 more years’ worth of diaries in the process. In 1895, however, the gaps in entries became larger again, with his final entry being written on November 20th. In it, he notes that someone visited in the afternoon: “No business transacted as I remember.”

These diaries can be a valuable primary source for researchers interested in these topics, offering a wealth of daily information and some unique observations. They can be found in the Moses Chess Diaries and Papers collection, which is housed and available for researchers to access at the Archives & Special Collections at our Archives Service Center location on Thomas Boulevard.

Works Cited

Moses Chess Diaries and Papers, AIS.2021.04, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

40th Anniversary of the 1982 Sugar Bowl

This post was written by Jon Klosinski, Archives Assistant for Archives & Special Collections.

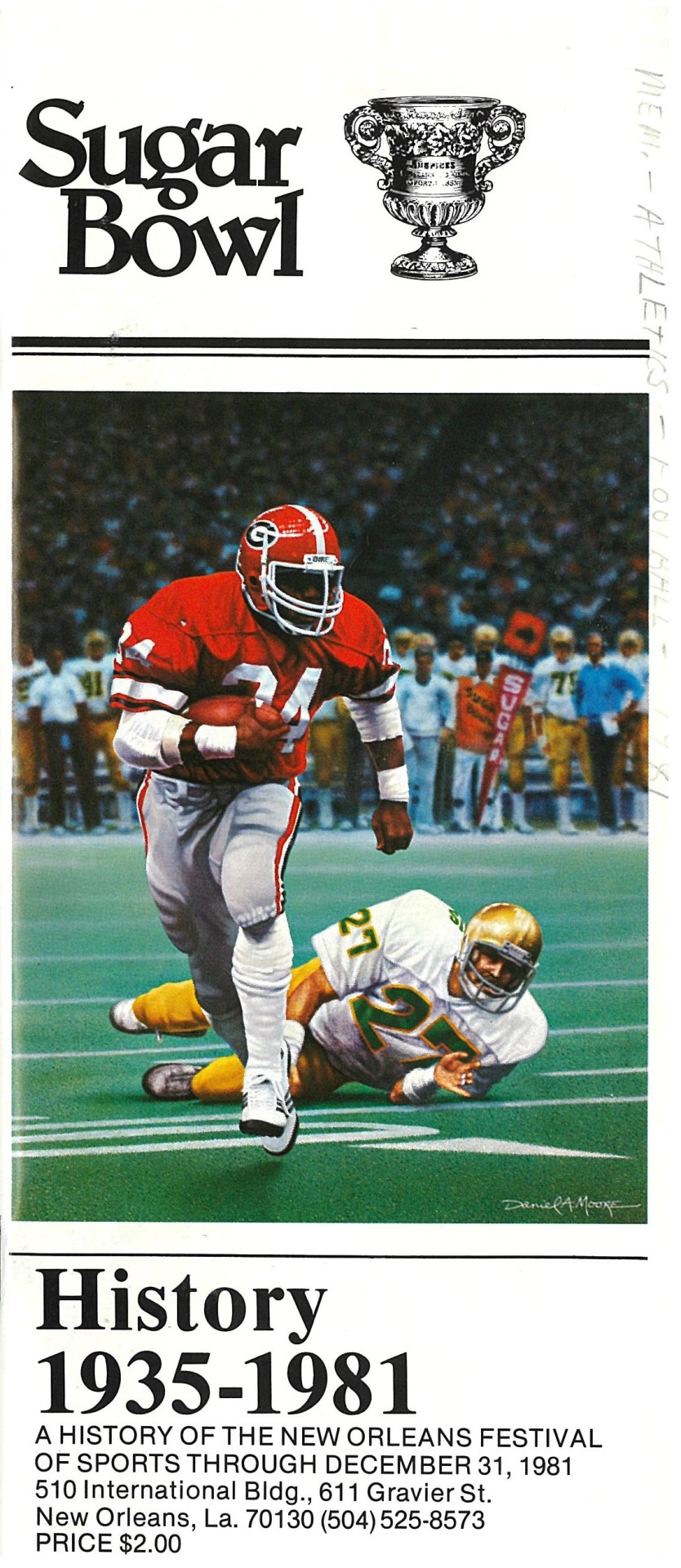

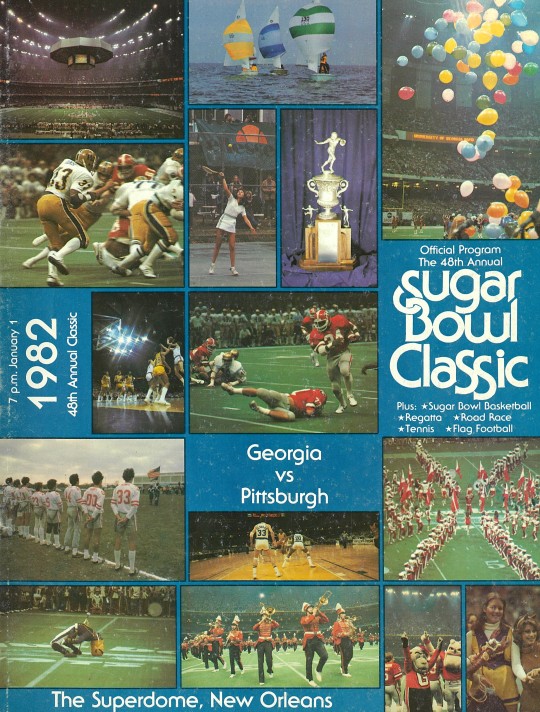

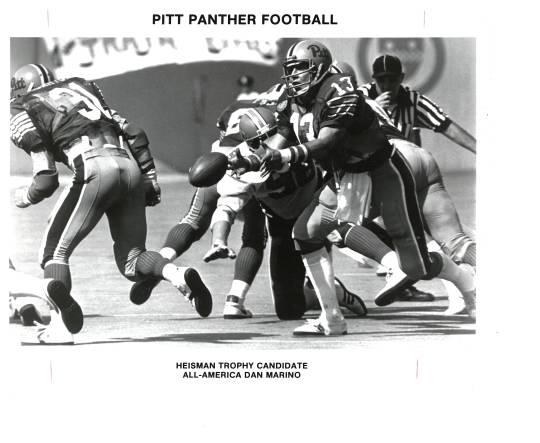

January 1, 2022, marks the 40th Anniversary of Panther Football's victory in the 1982 Sugar Bowl game. Led by Coach Jackie Sherrill and Quarterback and future College and Pro Football Hall of Famer Dan Marino, the #8 ranked Panthers defeated the #2 ranked Georgia Bulldogs (both with 10-1 season records) 24-20 in New Orleans Louisiana before a nationally televised audience.

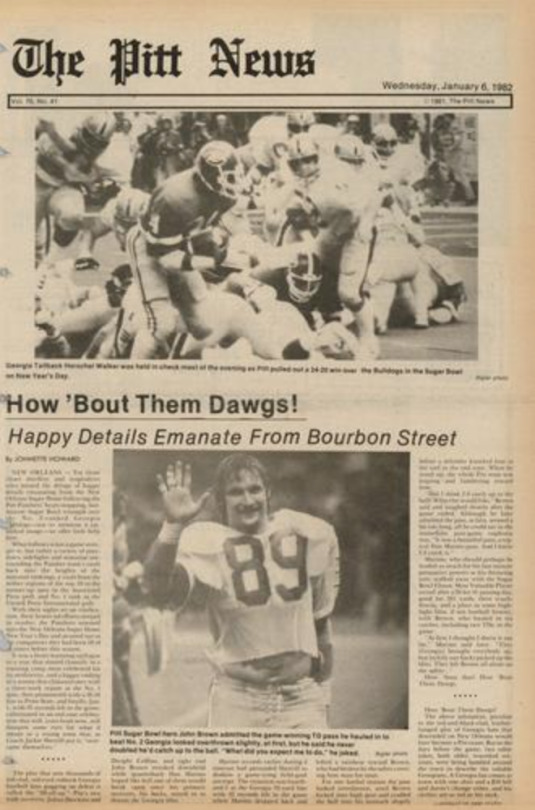

The game will be remembered forever for its dramatic finish. On 4th down and down 3 points with 42 seconds remaining in the game, Marino completed a game winning touchdown pass to tight end John Brown in what is among the greatest moments in college sports history:

youtube

Video courtesy of University of Pittsburgh on YouTube.

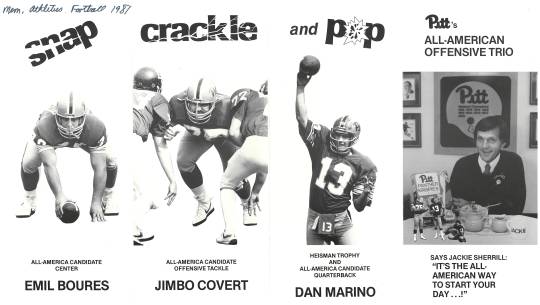

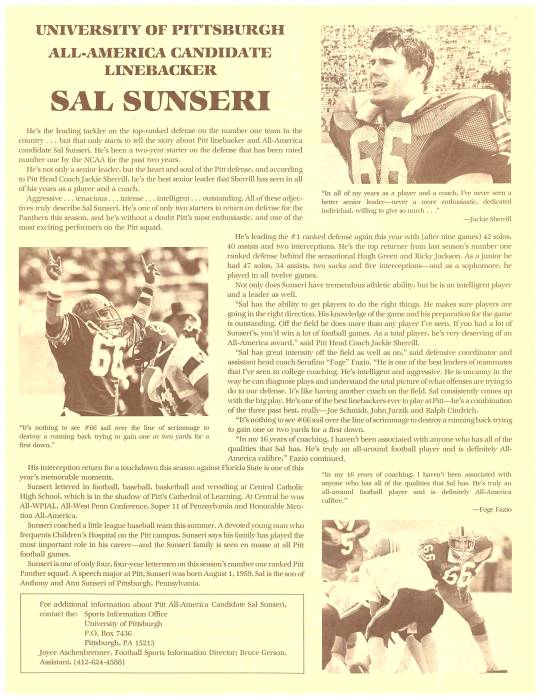

The Sugar Bowl victory completed a dominant three year run which saw Panther Football achieve a combined record of 33 wins and 3 losses with victories in three straight College Football bowl games, one of the longest sustained runs of success in Pitt Football history. The 1981 Panther Team also included three 1982 NFL draftees- Center Emil Boures, Linebacker Sal Sunseri and Defensive End Sam Clancy. Coach Sherrill, after a 6-season tenure at Pitt achieved a 50-9-1 record. Marino departed Pitt for the NFL after the 1982 season, having led the Panthers to four consecutive Top Ten AP Poll finishes and four total bowl game appearances. His #13 jersey was retired by Pitt in 1982.

The Archives & Special Collections Department of the University of Pittsburgh Library System is proud to share artifacts in our collections from that historic Sugar Bowl game and 1981-82 Football season:

(Above) Official Sugar Bowl 1982 Game Program and Media Guide University Archives Record Group 9/10-A Athletics-Football. Box 4 FF 16. Archives and Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

(Above) The Pitt News from January 6, 1982, celebrating Panther victory in the Sugar Bowl. Full issues of the Pitt News are available on the Archives and Special Collections Documenting Pitt Website. Pitt News, Vol. 76 No. 41, Archives and Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

(Above) Dan Marino and Coach Jackie Sherrill, c. 1981. On 4th down with 42 seconds left in the game, Marino famously told Coach Sherrill he didn't come all the way to New Orleans to tie the game. University of Pittsburgh Historic Photographs. FTBL05.UA. Archives and Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

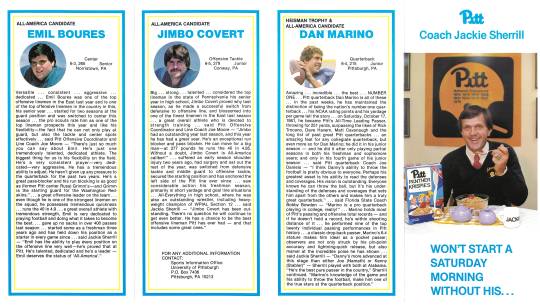

(Above) Marino was a 4th place finalist in Heisman Trophy voting for the 1981 season, receiving a total of 286 votes. He was opposed at the Sugar Bowl by 2nd place finisher, Georgia Running Back Herschel Walker (who would win the honor the following season). University Archives Personal File: Marino, Dan. Archives and Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

(Above) Coach Jackie Sherrill never started a pre-game Saturday morning without his "Snap, Crackle and Pop." University Archives Record Group 9/10-A Athletics-Football. Box 4 FF 16. Archives and Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

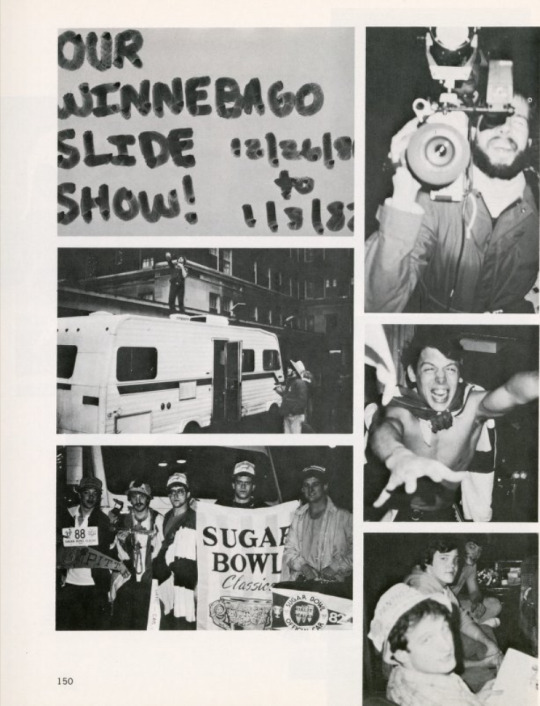

(Above) The 1982 Panther Prints yearbook displays a photo collage of the student trek to the 1982 Sugar Bowl in New Orleans, Louisiana. Pitt yearbooks are available online through the Documenting Pitt website. Panther Prints 1982. Archives and Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

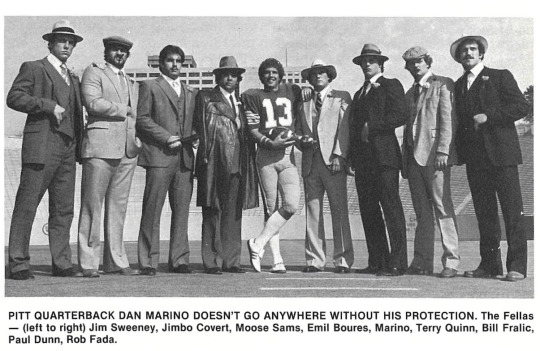

(Above) Marino never went anywhere during the 1981 season without his "protection". Official Football Publications. Pitt qLH1.P69V3.1981 Archives and Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

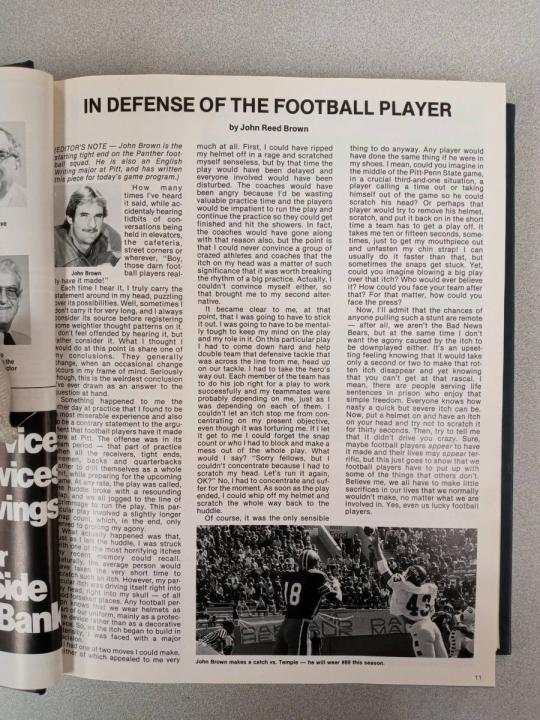

(Above) John Brown, Starting Tight End and English Writing major composed original essays for inclusion in Panther gameday programs during the 1981 season. Official Football Publications. Pitt qLH1.P69V3.1981 Archives and Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

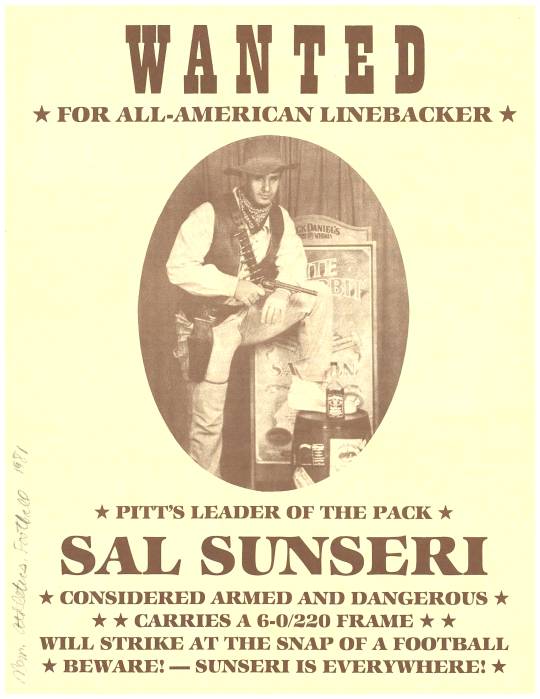

(Above) "Wanted "for NCAA All-American recognition in 1981: Pitt Linebacker Sal Sunseri (He received the honor) University Archives Record Group 9/10-A Athletics-Football. Box 4 FF 16. Archives and Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

(Above) Pitt Football bumper stickers from the 1981 season. University Archives Record Group 9/10-A Athletics-Football. Box 4 FF 16. Archives and Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

(Above) The 1981-82 Pittsburgh Panthers Football Team. University Archives Record Group 9/10-A Athletics-Football. Box 4 FF 16. Archives and Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jacob Bates Abbott and the United States Wilderness

This post was written by Meara “Yara” Makasakit, (Fall 2021 Undergraduate Intern)

Though environmental conservation awareness seems like a relatively new historical phenomena, the idea of protecting wildlife has existed for thousands of years. Many Indigenous cultures have held the natural world up with great respect. One of the Tlingit Tribe of Alaska’s core beliefs is to “build on the foundation of respect for... the bounty of the land and waters, and the land itself.” In contrast, the United States government began the crusade for conservation during the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt and continues to make environmental legislation to this day.

The early 1900s proved to be an exciting and tension-filled time for European-descended conservationists in the United States. At this time, conservationists sought to protect the great wonders of the United States from being exploited due to a lack of land regulation after the removal of Native Americans and transfer of their land to the United States government. People like Theodore Roosevelt, John Muir, and George Bird Grinnell fought for the protection of these lands and the wildlife it was home to. Through these efforts, the American public was able to learn and find avenues for themselves as individuals to take a stance and speak out. One artist who dedicated an entire career and body of work to the cause Jacob Bates Abbott. Abbott was an American artist whose work focused on US wildlife and had a career in creating art for publication in magazines and books.

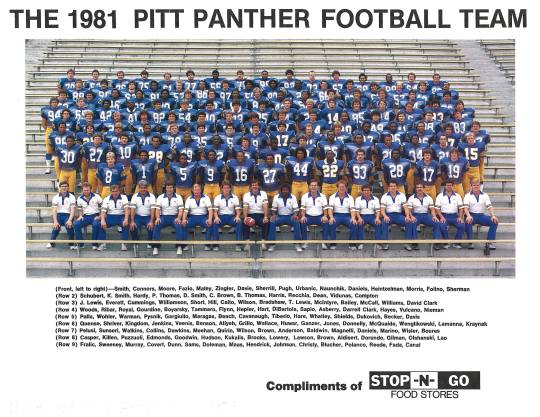

In the Jacob Bates Abbott Papers at the University of Pittsburgh Library System Archives & Special Collections, which I processed this semester, you can see evidence that Abbott had a longstanding relationship with the Pennsylvania Game News magazine. This was a hunting publication with a heavy focus on conservation and safe hunting practices. Abbott created the covers for the magazine’s monthly publications for almost ten years and wrote several articles for the magazine. The themes of these covers typically followed the holiday or season for that month, but always depicted a scene from nature.

In his June 1947 cover, Abbott illustrated a scene of a family of ducks wading in a stream with a curious deer beside them. In this work, and others, it can be inferred that Abbott did not actually witness this exact scene while out observing nature, but the skill and detail he includes gives the work life-like qualities. Though Abbott’s paintings were not hyper-realistic, the nature observations that he was constantly conducting shows in the detail of his work: the physical anatomy of the creatures, color patterns of the different animal’s fur and feathers, reflections in the water, and the surrounding greenery.

(Above) Image from folder “Pennsylvania Game News,” Jacob Bates Abbott Papers, AIS.2018.03, Box 12, Folder 8, Archives and Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System. Pennsylvania Game News cover from July 1947 depicting a family of ducks wading in a stream accompanied by a deer.

He was able to accomplish this by carrying out his own research and studies of the natural world. Abbott’s field notes are filled with his sketches and notes of what he had seen in places such as Pennsylvania, California, New Hampshire, and more. Abbott was dedicated to observing the world as it was, spending a great deal of time in the Pennsylvania wilderness watching and taking note of everything and anything he came across. It is incredibly apparent that Abbott cared a great deal for the work he was doing and found it to be important enough to commit most of his life and career to.

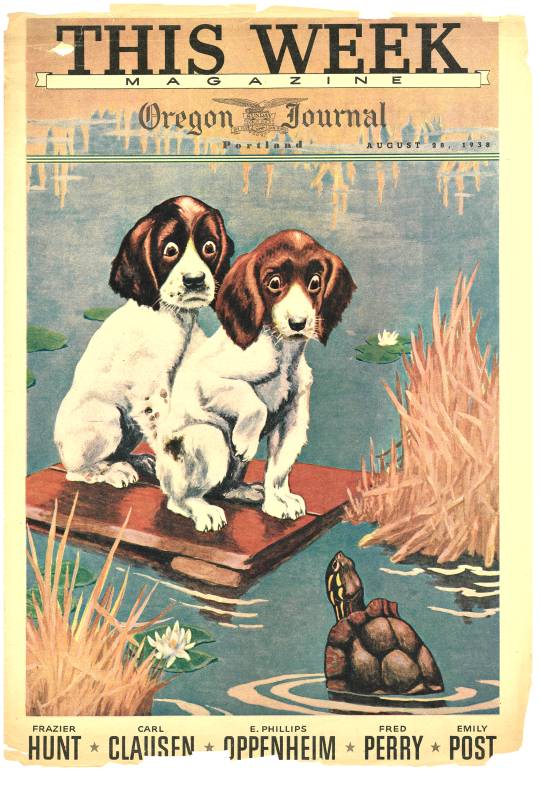

It was through observations that Abbott was able to re-imagine nature and its inhabitants to fit the themes of his covers. His re-interpretations of nature were, at times, more direct than the June 1947 magazine. In a cover he created for This Week Magazine: Portland, Oregon, Abbott illustrates a humorous scene of two puppies floating on a piece of wood, scared of an approaching turtle. This obviously is not a realistic scene, but it demonstrates how Abbott was able to adjust his style depending on the subject matter of his work.

(Above) Image from folder “This Week Magazine, Oregon Journal,” Jacob Bates Abbott Papers, AIS.2018.03, Box 14, Folder 19, Archives and Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

This Week Magazine Cover from August 28, 1938, depicting two puppies being frightened by an approaching turtle.

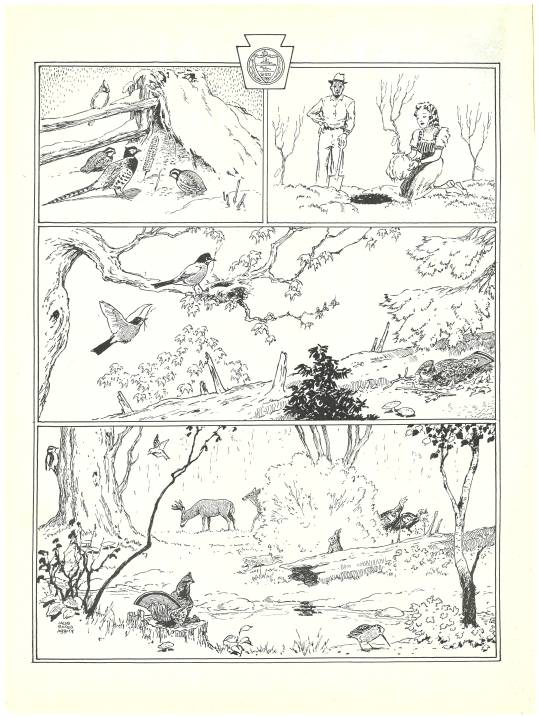

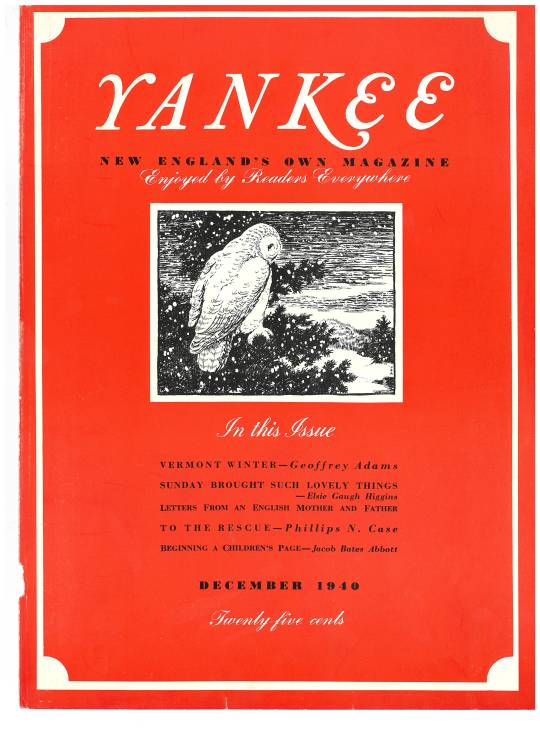

Many of Abbott’s most known publication cover designs were originally paintings. He was incredibly skilled in other mediums such as ink and graphite. Abbott’s cartoons and ink drawings can be found in most issues of the Pennsylvania Game News magazines that he also created covers for. Here, he provided illustrations and cartoons for articles that were being published, usually of the different species that are being discussed in the writing. Building on these simple drawings, he created covers for the Yankee magazine that were detailed line drawings. Though he was not as prominent of a figure at the Yankee as he was at the Pennsylvania Game News, the same principles of observation applied for the work he did there.

(Above) Image from folder “Pennsylvania Game News,” Jacob Bates Abbott Papers, AIS.2018.03, Box 11, Folder 3, Archives and Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System. Pennsylvania Game News magazine, March 1945, page sectioned into 4 parts depicting different scenes of wildlife and one with a Pennsylvania trooper and woman planting a tree.

(Above) Image from folder “Pennsylvania Game News,” Jacob Bates Abbott Papers, AIS.2018.03, Box 11, Folder 3, Archives and Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System. Pennsylvania Game News magazine, March 1945, article, “Woodchuck Defense,” illustration of a hunter and woodchuck holding a flag of surrender.

(Above) Image from folder “Yankee,” Jacob Bates Abbott Papers, AIS.2018.03, Box 12, Folder 13, Archives and Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System. Yankee magazine cover from December 1940 depicting an owl standing on a tree branch during a winter snowfall.

Though Abbott has not been well-documented historically, the entirety of his artistic career is now housed in his papers at the University of Pittsburgh Library System Archives & Special Collections, which includes most of his original work. This collection is important because it shows the ongoing history of the fight for conservation, particularly on the side of conservation awareness. Abbott was able to bring the United States wilderness to people’s homes, offices, and schools. This allowed the entire country, particularly Pennsylvanians, to see the beauty of nature and to garner support for its care. The natural world continues to need people to defend, protect, and speak up for it. From the earliest Indigenous people, to politicians, to private business, and now to the individual, conservation is still a present-day concern that cannot be given up.

Citations:

“About Us.” Tlingit & Haida - About Us - Overview, http://www.ccthita.org/about/overview/index.html.

Burns, Ken, director. The National Parks: America's Best Idea, The Last Refuge: 1890-1915, Public Broadcasting Service, n.d..

“Conservation Timeline 1901-2000.” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 26 Feb. 2015, https://www.nps.gov/mabi/learn/historyculture/conservation-timeline-1901-2000.htm.

Jacob Bates Abbott Papers, AIS.2018.03, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Pittsburgh Musicians’ Union Merger: “It Revolves Around Representation”

This post was written by Char Pyle (Fall 2021 Undergraduate Intern).

(Above) Pages from the program of the AFM’s 1962 Annual Convention, hosted at the Civic Arena in Pittsburgh. American Federation of Musicians, Local 60-471, Pittsburgh, Pa. Records, 1906-1996, AIS.1997.41, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

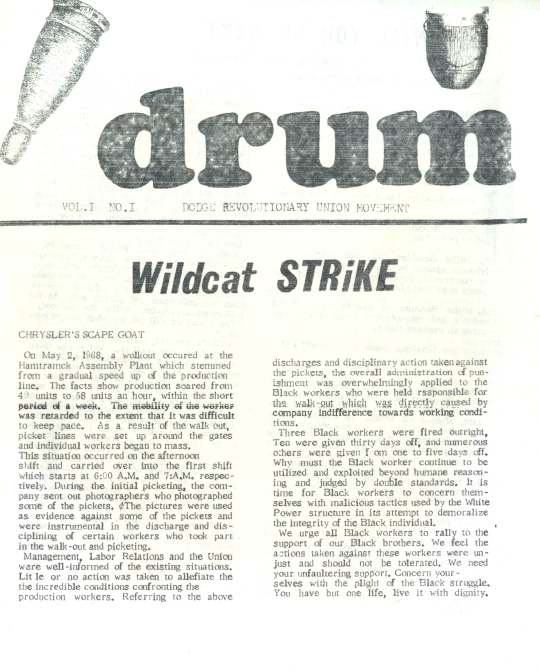

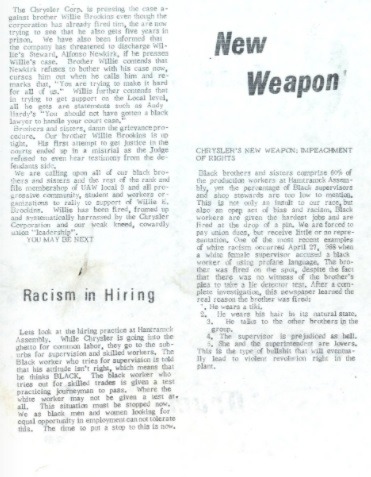

The American Federation of Musicians (AFM) is a labor union representing musicians across the country. The Pittsburgh Musicians’ Union, Local 60-471 of the AFM, has a particularly storied history. Local 60 was formed in 1897, one year after the AFM was founded. In 1908, Local 471 was created for black musicians in Pittsburgh. The two locals merged in 1966 following an integration order from the AFM. While the integration seems like it could be a positive thing, this only meant it would be more difficult for black musicians to advocate for themselves and be heard. This is evident even in the meeting minutes between both locals surrounding the merger. This interaction is noted at the beginning of the meeting:

“Before considering items, Pres. Davis asks: ‘How can we meet on common ground? What do we need? (to effect agreeable merger)’ Pres. Westray answers: ‘It revolves around representation.’”

This emphasis on representation is visible in Local 471’s proposals during the merger. Policies proposed by Local 471 included suggestions of affirmative action, shown in “Exhibit D” under “Negro Representation in Elective Offices of the Merged Union”. They sought out guaranteed representation in elected office, as they were likely not hopeful that they would truly be perceived as equals by the majority-white membership base of the merged union. Unfortunately, this has proved to be true. Since the merger, and still today, leadership of Local 60-471 is primarily white. Based on these minutes, it appears these suggestions were heavily contested and subsequently dismissed by members of Local 60. One of their arguments was that this was “a type of segregation in reverse”. This shouldn’t be an unfamiliar idea, as similar arguments are still echoed today in the realms of employment and education.

(Above) Exhibit D in the merger meeting minutes between the executive boards of both locals. American Federation of Musicians, Local 60-471, Pittsburgh, Pa. Records, 1906-1996, AIS.1997.41, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

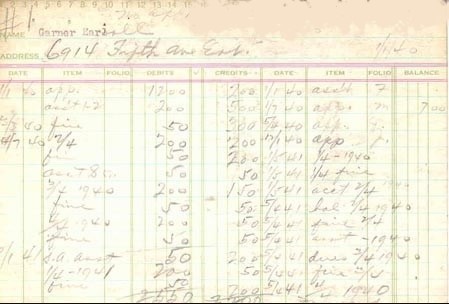

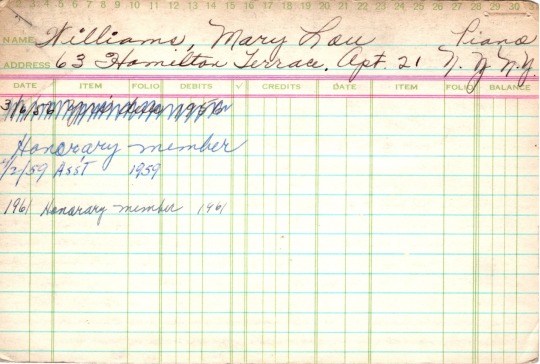

Another result of the merger is the lack of records from Local 471. There is significantly more material available for Local 60, including film reels, publications, meeting minutes, photographs, and various booklets. It’s not clear why this discrepancy exists, but Local 471’s records may have simply been overshadowed as the merged union was mostly made up of former Local 60 members. This could have led to the merged local being viewed as simply a continuation of the white local, devaluing the preservation of artifacts related to Local 471. The merger also caused many black members to become disillusioned with the union, so there wouldn’t have been many people interested in preserving those records anyway. The effects of this lack of preservation were apparent almost immediately, as membership cards for many Local 471 members were lost in the merger. This led to a discontinuation of seniority benefits (even though the opposite was promised in the merger minutes), which caused many to cancel their memberships.

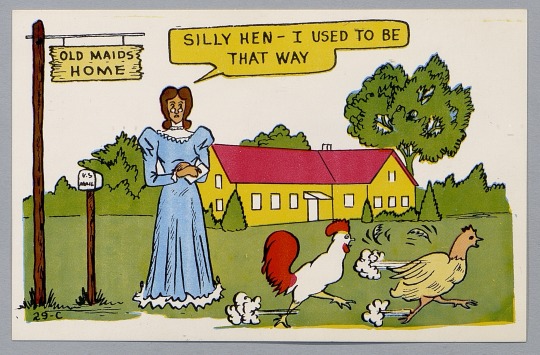

It’s difficult to say whether much would have changed had these policies been approved. Perhaps with more of a presence in the administration of the union, Local 471 would have retained more of its membership and its history would have been better preserved. When so many former Local 471 members resigned, they lost the ability to play music in Pittsburgh. The city may have missed out on countless performances and talented artists because of this. Unfortunate as it may be, this event was a milestone for black musicians in Pittsburgh, and greatly shaped the landscape of Pittsburgh music as a whole. This collection would be of use to those researching local musicians from the 20th century. Prominent figures that were members of Local 471 include the following, and membership cards are available for each:

Carl Arter (President)

George Benson

Art Blakey

Ray Brown

Roy Eldridge

Erroll and Linton Garner

Walter Harper

Joe Harris

Earl Hines

Roger Humphries

Ahmad Jamal

Grover Mitchell

Horace Parlan

Stanley Turrentine

Joe Westray (President at time of merger)

Mary Lou Williams

Ruby Younge Hardy (Secretary-Treasurer)

(Above) Membership cards (from top to bottom) of Art Blakey, Erroll Garner, and Mary Lou Williams. American Federation of Musicians, Local 60-471, Pittsburgh, Pa. Records, 1906-1996, AIS.1997.41, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Additional Sources:

http://jazzburgher.ning.com/profiles/blogs/old-mon-music-pittsburgh-blog

https://www.afm.org/about/history/

https://www.afmpittsburgh.com/a01-aboutus.html

http://exhibit.library.pitt.edu/labor_legacy/MusiciansHistory471.htm

American Federation of Musicians, Local 60-471, Pittsburgh, Pa. Records, 1906-1996, AIS.1997.41, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Another Level of Consciousness": Black Excellence in Theatre

This post was written by Sean Hale, Undergraduate student of Theatre Arts and Linguistics and student assistant on the CLIR Recordings at Risk grant “Preservation and Access to Pittsburgh’s Black Arts Movement Performance Organizations: The Legacy Media of the Bob Johnson Papers and Kuntu Repertory Theatre Collection”.

The University of Pittsburgh Archives & Special Collections is home to a wide array of artifacts, sources, and stories just waiting to be explored. Over the summer, I have been reviewing and creating descriptive metadata for VHS and U-Matic tapes from the Kuntu Repertory Theatre Collection and Bob Johnson Papers for digitization. During my time here, I was able to view and closely study the works of the Kuntu Repertory Theatre (KRT) and their contributions to the black community. A theatre group that had a timeless and vital message that not only swayed Pittsburgh, but reached national notoriety.

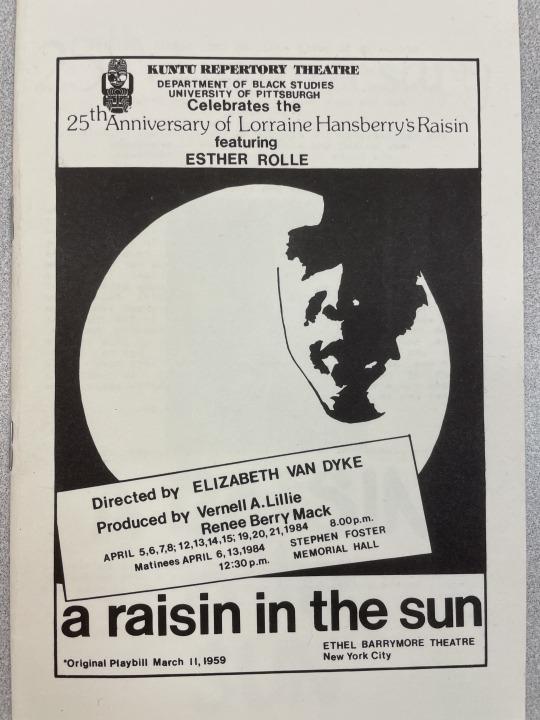

KRT was able to host a number of outstanding and provocative stage pieces. One such event was the phenomenal performance of Lorraine Hansberry's "A Raisin in the Sun" for its 25th anniversary. This production was truly an event to be seen, with special guest Esther Rolle (known for her role as "Florida Evans" in the television show Maude) in the roll of Lena Younger. It can be seen to what extent KRT planned and crafted the telling of this story to their audience.

No small detail was left untouched, ranging from the performers' careful voice and movement, to the fine characteristics and formation of the set. The action of the play revolves around a two-bedroom apartment in Chicago's Southside. The design for stage was a captivating construction that took what should have been imagined as a three-dimensional home and splayed it out in a two-dimensional view. The choice outlined the run-down, dull, and flat feeling of the apartment and illustrated the struggle of the characters feeling trapped in their space.

(Above) Marcia Jones, in the role of Ruth Younger, and Esther Rolle, in the role of Lena Younger, performed by Kuntu Repertory Theatre in Stephen Foster Memorial Hall, 1984.

The recording, seemingly professionally shot, was able to capture close-up imagery of the performers, highlighting the delicate work and dedication they invested into portraying such dynamic characters. Marcia Jones, in the role of Ruth Younger, demonstrated a noticeably exhausted and worn figure in her portrayal through her tone and posture. She also carried an exceptional energy that she passed back and forth in scenes with Walter Lee, played by Donus Crawford. Rolle's depiction of Lena was also truly exceptional, with the tape perfectly capturing her tight and rigid body that was held with teary eyes and a shaky voice during the scene following Walter Lee's heartbreaking mistake.

(Above) Donus Crawford, in the role of Walter Lee Younger.

Kuntu Repertory Theatre was grounded in two important ideals. In terms of mission, they ensured that black artists and technicians could tell the stories that often went overlooked, highlighting the black experience by a black arts collective. In terms of art, they created spaces and performances that emphasized the experience of art, rather than the object of art itself. KRT found its roots for these objectives in the Black Arts Movement and the artistic traditions that were embedded in African culture and its continuum. This piece exquisitely underlined this goal with grand detail, even so much that the program used for this production was only slightly edited from the original premiere in 1959.

(Above) Kuntu Repertory Theatre’s program for its production of A Raisin in the Sun, April 1984.

The combination of performance, design, and overall elements of production detailed the struggle that black people in America have experienced for generations. Kuntu Repertory Theatre's production of "A Raisin in the Sun" exemplifies the story's undying message, whether that be 1959, 1984, or even today.

#blacktheatre#blackart#black#theatre#art#civilrightsmovment#araisininthesun#lorrainehansberry#kunturepertorytheatre

0 notes

Text

Dick Thornburgh: An Inspection of Politicians’ Core Beliefs across their Careers

The post was written by Caleb Tsai, an Undergraduate Computer Science major at the University of Pittsburgh and a student in the Honors College’s Foundations of Research and Scholarship course in the Spring of 2021

Dick Thornburgh was an extremely influential figure in both the United States and the greater Pittsburgh region, serving as U.S. Attorney for the Western District of Pennsylvania, Governor of Pennsylvania, and U.S. Attorney General. In 1998, the Dick Thornburgh Papers, the archive upon which this research is founded, was donated to the University of Pittsburgh Library System. I chose to research Dick Thornburgh because I was intrigued by both the depth and breadth of Thornburgh’s actions throughout his career. Initially, I did not know what specific areas I wanted to delve into, but the Thornburgh Papers provided an abundance of resources to aid me during my search.

Figure 1 (above): Formal picture of Dick and Ginny Thornburgh with their four sons, 1972. Dick Thornburgh Papers, Series XVIII. Photographs, 1932-2004. Dick Thornburgh Papers, 1932- , AIS.1998.30, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

My motivation for this proposal is mainly due to an interest in whether political figures are trustworthy in following through on their campaign agendas prior to being elected. At the time of this publication, the 2020 Presidential election between incumbent Republican Donald Trump and Democrat Joe Biden has recently concluded, and I want to learn more about whether ideas and beliefs held by political figures change or remain consistent over the entirety of their careers.

Thus, my research question is defined as follows:

As Attorney General of the United States, how was Dick Thornburgh’s focus on criminal justice and environmental reform tied to his preceding title of Governor of Pennsylvania?

I felt that this initial question could then introduce a larger problem statement:

Discover trends across two ends of Thornburgh's political career to identify continuity and change regarding criminal and environmental reform.

Finally, I constructed my significant statement, which can be tied back to my initial interests in Dick Thornburgh and his career:

Uncover insight into the inner workings of prominent political figures and how their ideas developed throughout their career.

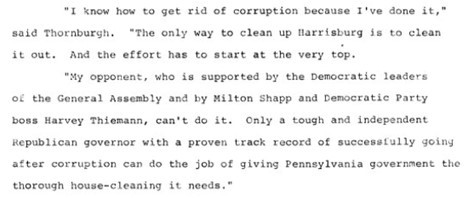

In terms of archival material, I concluded that Thornburgh remained most aligned with issues regarding criminal reform during his role as both Governor of Pennsylvania from 1978-1987 and Attorney General of the United States from 1988-1991. In September 1978, his first year as governor, Thornburgh published an “Outlined 7-point plan for "cleaning up" corruption in PA's General Assembly, Harrisburg, PA.” I identified from Thornburgh’s direct quotes (Figure 2) that he utilized very confident and passionate language in describing the sheer frequency and need to reduce corruptions within government: ‘I know how to get rid of corruption because I’ve done it… The only way to clean up Harrisburg is to clean it out. And the effort has to start at the very top.’ In terms of context, it is also important to note that this news release was published by Thornburgh and his running mate William Scranton for their campaign, which explains why Thornburgh is portrayed in this manner.

Figure 2 (above): Outlined 7-point plan for "cleaning up" corruption in PA's General Assembly, Harrisburg, PA, 1978. Dick Thornburgh Papers, Series IX. Campaign for Governor of Pennsylvania, 1978. Dick Thornburgh Papers, 1932-, AIS.1998.30, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

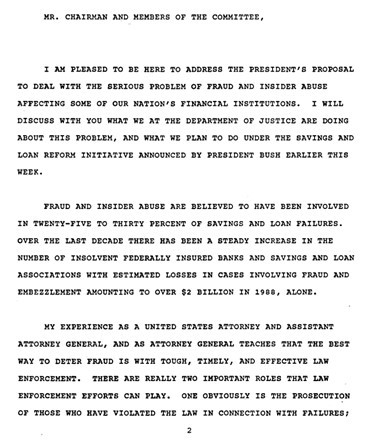

Later in Thornburgh’s career as Attorney General of the United States, I found that a very similar sentiment in combating corruption remained at the forefront of Thornburgh’s mind in his “Statement Before the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs Concerning Fraud in the Savings and Loan Association Area” in February 1989. From the initial paragraphs of this document (Figure 3), one can tell that Thornburgh maintains his strict stance against corruption regardless of the institution, the party in question now a financial rather than government body. In a position of greater influence, Thornburgh then effectively uses his power by addressing and insisting the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs take action, conveying Thornburgh’s genuine desire to combat the same corruptions he addressed early in his political career.

Figure 3 (above): Statement Before the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs Concerning Fraud in the Savings and Loan Association Area, 1989. From the U.S. Department of Justice. Dick Thornburgh Papers, 1932-, AIS.1998.30, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Thus, Dick Thornburgh did in fact represent continuity in his vision for reforming the corruption that readily existed at the beginning of his career, the end of his career, and still exists in the present. However, one must understand that not every political figure may be as forthcoming or stay true to their initial agendas. To reinforce the results of this study, the next steps moving forward will be to examine political figures from a vast array of backgrounds and political systems. In this manner, incorporating a wide range of diverse variables will lead to stronger and more reliable results. Ultimately, we will then continue to uncover more and further appreciate these gifted men and women in our history who have and continue to pave the institutions we view as places of authority and influence.

Works Cited

Unknown Photographer. “Formal picture of Dick and Ginny Thornburgh with their four sons”, 1972. University of Pittsburgh, Dick Thornburgh Papers, Series XVIII. Photographs, 1932-2004. Dick Thornburgh Papers, 1932-, AIS.1998.30, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Press Release. “Outlined 7-point plan for "cleaning up" corruption in PA's General Assembly, Harrisburg, PA,” 1978. University of Pittsburgh, Dick Thornburgh Papers, Series IX. Campaign for Governor of Pennsylvania, 1978. Dick Thornburgh Papers, 1932-, AIS.1998.30, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Thornburgh, Dick. “Statement Before the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs Concerning Fraud in the Savings and Loan Association Area,” 1989. From the U.S. Department of Justice. Dick Thornburgh Papers, 1932-, AIS.1998.30, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

1 note

·

View note

Text

John Hammond and Martha Glaser: A Cold Correspondence

This post was written by Adam Lee, graduate student, Jazz Studies.

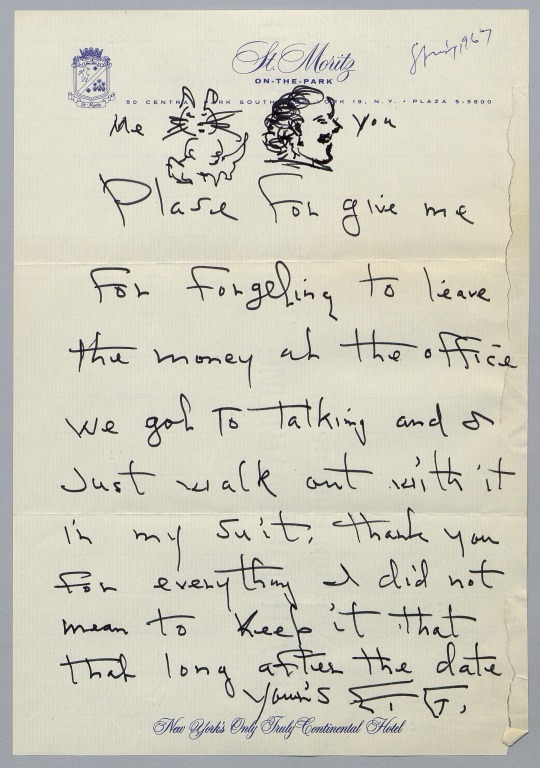

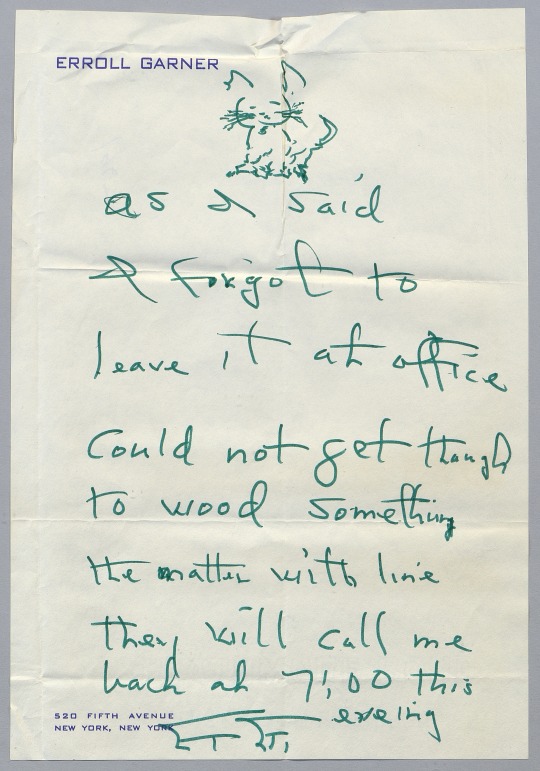

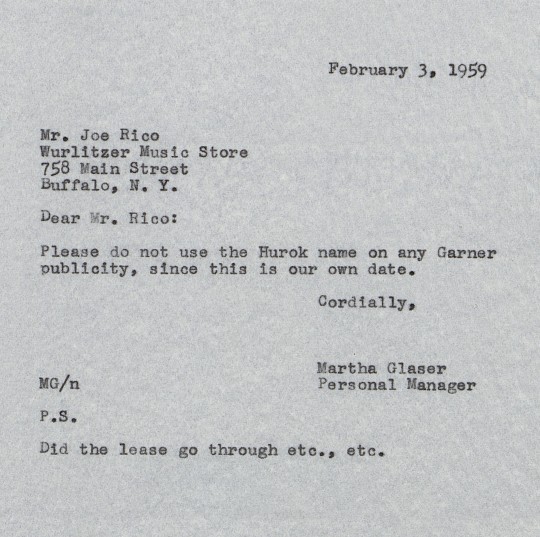

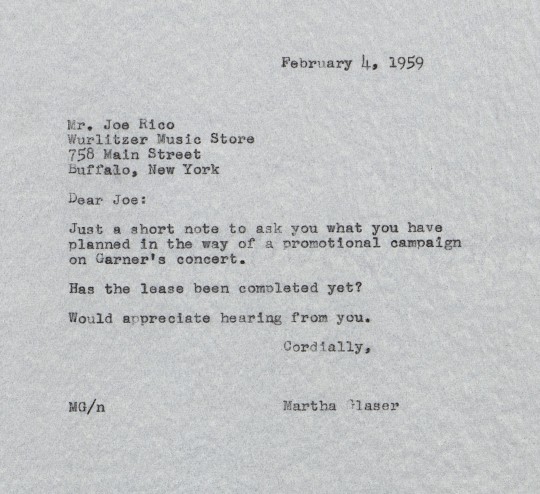

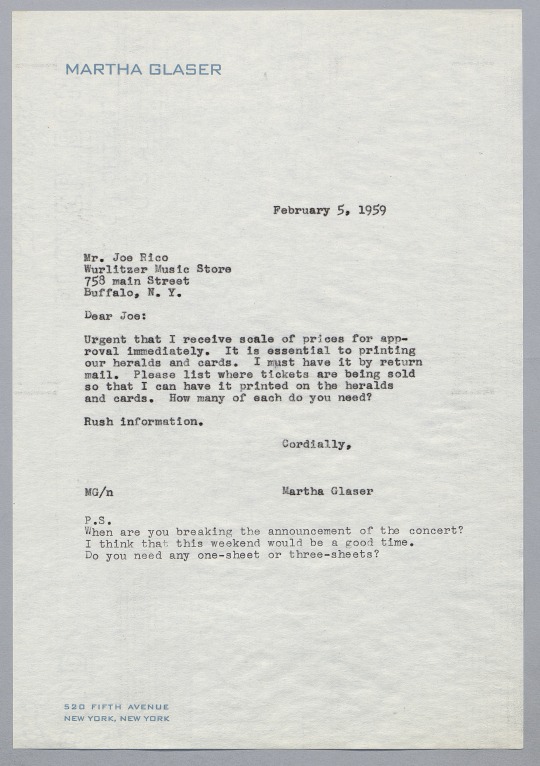

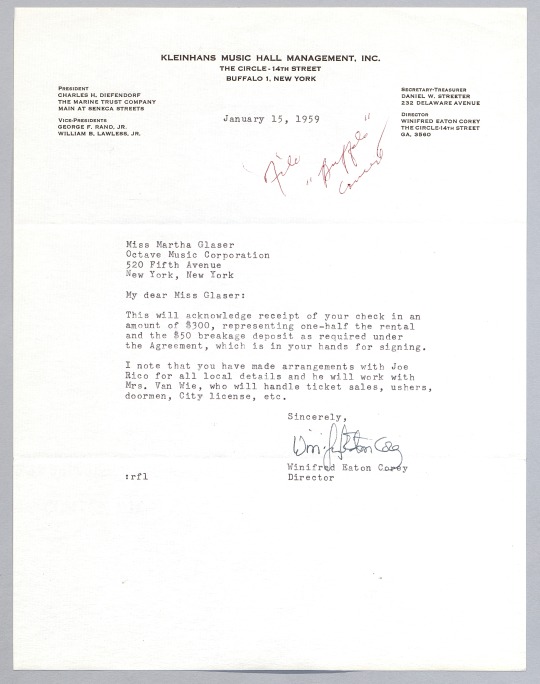

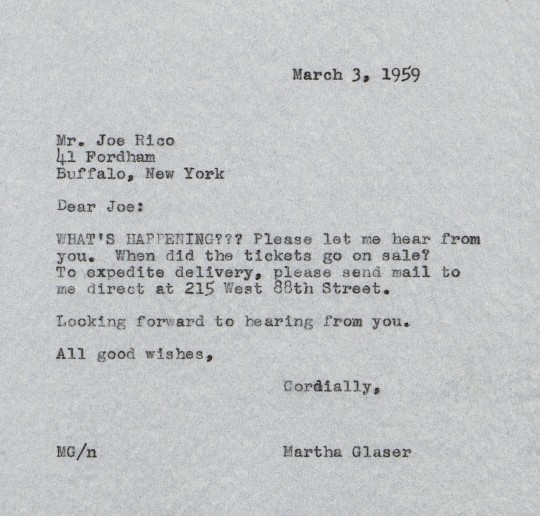

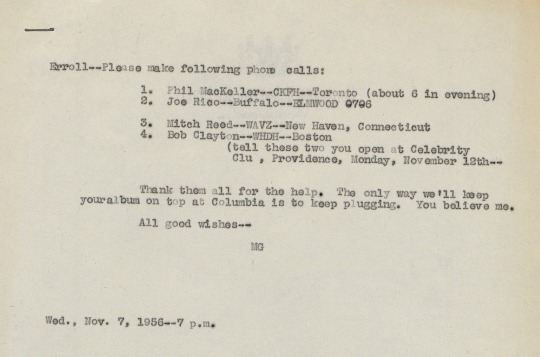

Erroll Garner famously won a lawsuit against record production titan Columbia Records in the early 1960s, which allowed him to launch his own label Octave records. While the details of this lawsuit have been covered by news outlets such as Variety (The True Story of Erroll Garner, the First Artist to Sue a Major Label and Win), the fallout of this suit would continue to echo throughout history in the form of a feud between Garner’s manager Martha Glaser and Columbia Records producer John Hammond.

John Hammond was a scion of the Vanderbilt family through his mother and by the 1930s had become one of the most influential promoters and producers of jazz, acting as a patron to such jazz legends as Count Basie, Billie Holiday, and Benny Goodman (who became his brother-in-law in 1942). He is often lauded for his staunch stance against racism through his promotion of jazz in a time in which it was considerably less common to find white people of status working to promote Black artists. Not all jazz artists would receive Hammond’s full support, however, as is made clear with his lukewarm response to Erroll Garner’s work.

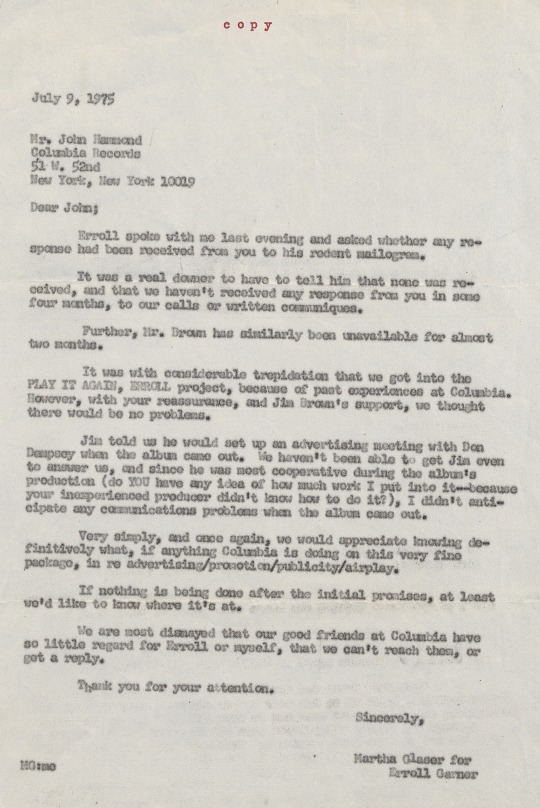

Hammond was the producer working for Columbia when the events that led to Garner’s lawsuit came about, and later would become involved again in a Garner reissue project in 1975. Martha Glaser, writing on behalf of Garner, wrote to Hammond expressing her disdain for the way Columbia, and thus Hammond himself, was handling this project in the last few years of Garner’s life.

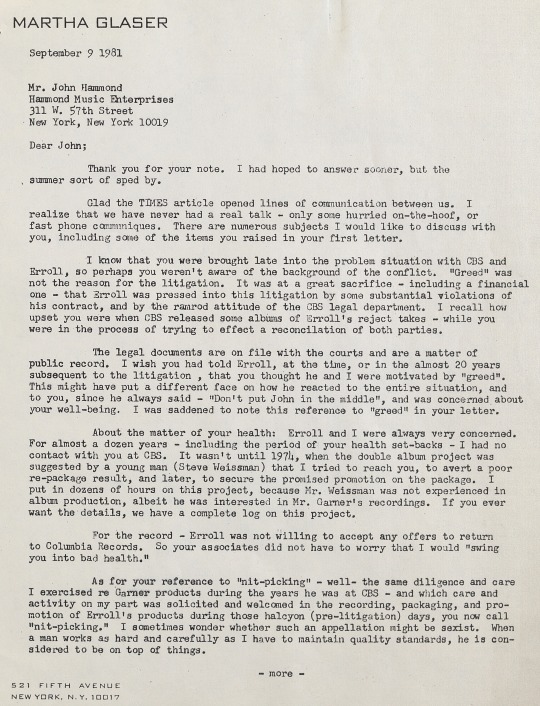

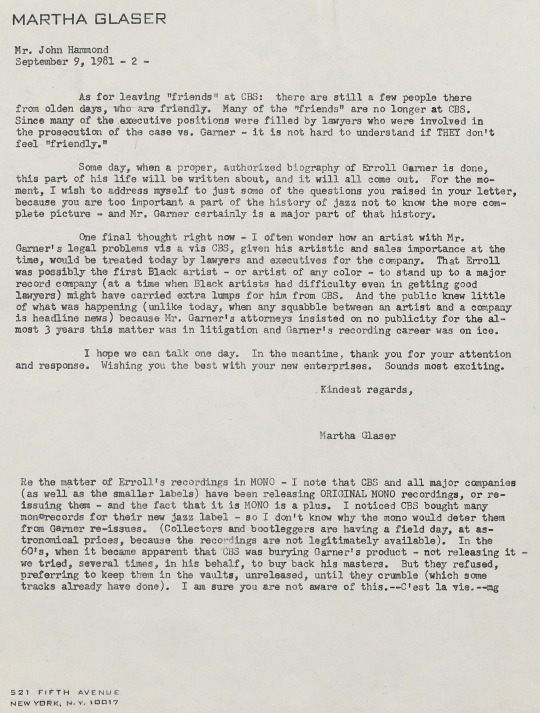

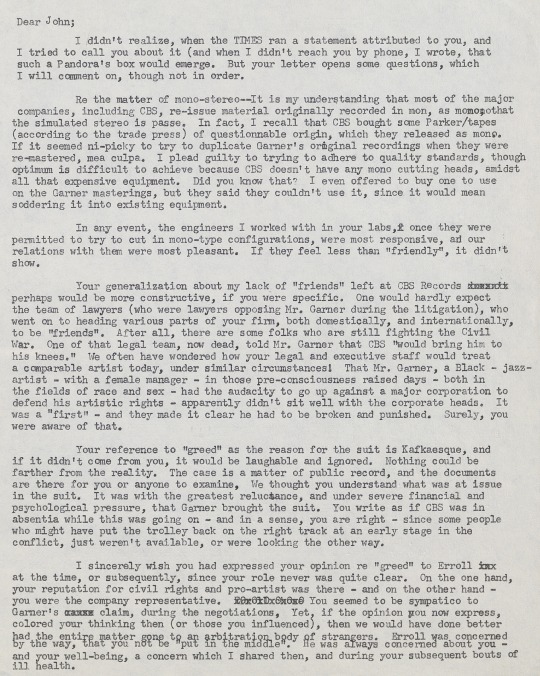

Image from folder “Correspondence from John Hammond,” Erroll Garner Archive, 1942-2010, Box 1, Folder 62, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Glaser writes that Garner and she were reluctant to be involved in a Columbia production, understandable from their previous contentious relationship, but initially thought that Hammond would be supportive of the project: “It was with considerable trepidation that we got into the PLAY IT AGAIN, ERROLL project, because of past experiences at Columbia. However, with your reassurance, and Jim Brown’s support, we thought there would be no problems.” Clearly, there were problems and Glaser had no reservations expressing her feelings later in the letter writing: “We are most dismayed that our good friends at Columbia have so little regard for Erroll or myself, that we can’t reach them, or get a reply.” The venom in her language is clear, the Columbia producers are no friends of theirs.

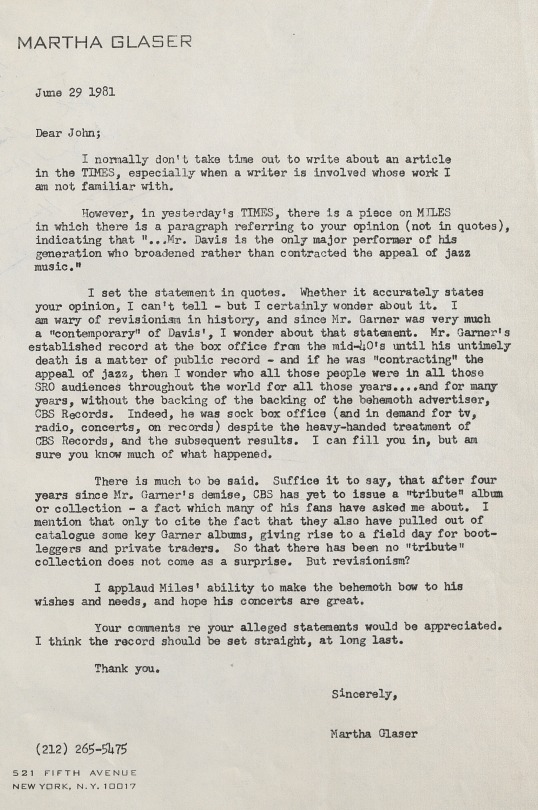

Image from folder “Correspondence from John Hammond,” Erroll Garner Archive, 1942-2010, Box 1, Folder 62, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Several years later, after Garner’s passing, Glaser and Hammond got into another conflict via letters sent between them. We do not have every record in the archive of this correspondence, but by looking at the letters we do have we can extrapolate some of the content, and it is increasingly hostile. The conflict seems to begin with Glaser’s objection to a quote in George Goodman Jr.’s June 28, 1981 article about Miles Davis titled ”Miles Davis: I Just Pick Up My Horn And Play.” In the article, Goodman attributes a statement to Hammond (which Glaser notes is not written as a quote, but more as a statement of fact): “To John Hammond, the authoritative critic and jazz patron credited with the ‘discovery’ of such greats as Bessie Smith and Louis ''Satchmo'' Armstrong, Mr. Davis is the only major performer of his generation who broadened rather than contracted the appeal of jazz music.” Glaser vehemently objects to this characterization, and overtly questions Hammond on it in a letter dated the next day, June 29, 1981: “Whether it accurately states your opinion, I can’t tell – but I certainly wonder about it.” Glaser goes on to contradict the assertion that only Davis expanded jazz appeal, referring to Garner’s public success with scathing and sarcastic language: “… if he was ‘contracting’ the appeal of jazz, then I wonder who all those people were in all those SRO audiences through the world for all those years…,” and “Indeed, he was sock box office…despite the heavy-handed treatment of CBS Records, and the subsequent results. I can fill you in, but I am sure you know much of what happened.” Obviously Hammond knows what happened, as he was the head of A&R (Artists and Repertoire) for CBS/Columbia Records at that time.

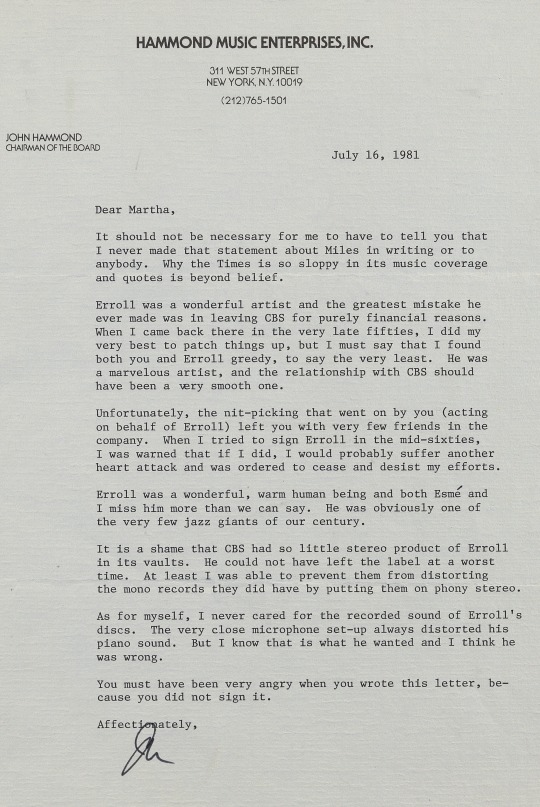

Image from folder “Correspondence from John Hammond,” Erroll Garner Archive, 1942-2010, Box 1, Folder 62, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Hammond’s response is dated July 16, 1981 and specifically refutes the Goodman article for the Times, attempting to redirect the ire against him to the Times itself saying, “Why the Times is so sloppy in its music coverage and quotes is beyond belief.” While he could have continued to play diplomat, he instead doubles down on the conflict and writes some very specifically cruel things about Garner and Glaser “…the greatest mistake he ever made was in leaving CBS for purely financial reasons. When I came back there in the very late fifties, I did my best to patch things up, but I must say that I found both you and Erroll greedy, to say the very least.” He follows this with an attack on Glaser alone: “Unfortunately, the nit-picking that went on by you (acting on behalf of Erroll) left you with very few friends in the company. When I tried to sign Erroll in the mid-sixties, I was warned that if I did, I would probably suffer another heart attack and was ordered to cease and desist my efforts.”

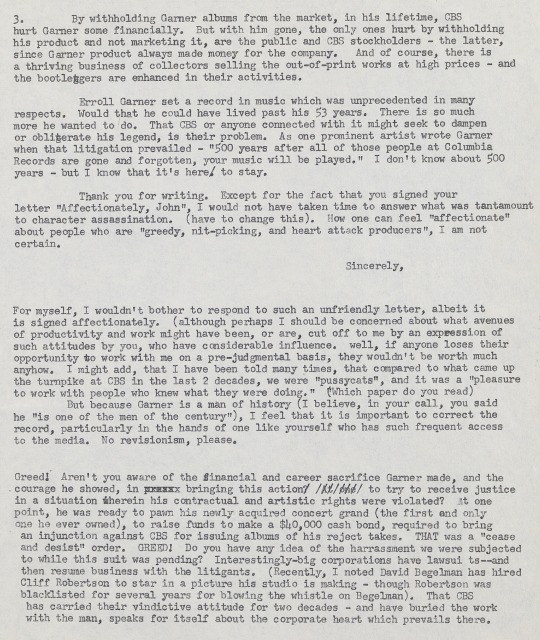

Images from folder “Correspondence from John Hammond,” Erroll Garner Archive, 1942-2010, Box 1, Folder 62, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

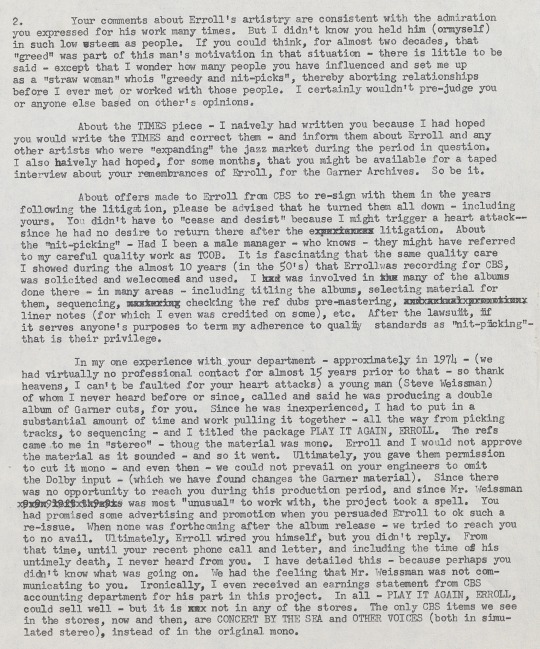

Glaser counters the attacks directly: “’Greed’ was not the reason for the litigation. It was at a great sacrifice – including a financial one – that Erroll was pressed into this litigation by some substantial violations of his contract.” Ever the stalwart defender of Garner, Glaser accuses Hammond of hiding this opinion from Garner behind a smiling face: “I wish you had told Erroll, at the time, or in the almost 20 years subsequent to the litigation, that you thought he and I were motivated by ‘greed’. This might have put a different face on how he reacted to the entire situation, and to you, since he always said – ‘Don’t put John in the middle’, and was concerned about your well-being.” Glaser continued to take issues with Hammond’s specific phrase “nit-picking,” and notes the implications of such language: “I sometimes wonder where such an appellation might be sexist. When a man works as hard and carefully as I have to maintain quality standards, he is considered to be on top of things.” The jarring final statement is loaded with a sarcastic feel, like Glaser is writing pleasantries because these things are included in letters by practice but not by meaning: “I hope we can talk one day. In the meantime, thank you for your attention and response. Wishing you the best with your new enterprises. Sounds most exciting.”

Image from folder “Correspondence from John Hammond,” Erroll Garner Archive, 1942-2010, Box 1, Folder 62, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

To this letter we do have Hammond’s response, dated September 19, 1981. And once again, venomous statements are bookended with pleasantry. Hammond first apologizes about the greed comment, but by the third paragraph he outright tells Glaser that Garner would have been more financially and professionally successful if they had stuck with him and Columbia Records.

(Above) Images from folder “Correspondence from John Hammond,” Erroll Garner Archive, 1942-2010, Box 1, Folder 62, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

The final document in this record appears to be a draft of a letter typed by Glaser before the final version dated September 9,1981. While this document does not have a date, it does follow many of the same points of the dated letter and responds point by point to Hammond’s July 16, 1981 document. This draft has numerous redactions and corrections, and the language in it is much stronger than the one that eventually replaced it, (including one parenthetical where Glaser notes “have to change this” after expressing that Hammond’s letter was “character assassination.”) And it is perhaps for the best that it wasn’t sent, but in it we can see the rage that Glaser had for Hammond and the industry, and the vigor by which she was ready to protect Garner’s reputation and status. This draft letter too shows some significant insight into the things that Glaser thought were important, but (in contrast with the final letter) chose to hold back, almost certainly as a result of professional considerations. She writes “That Mr. Garner, a Black – jazz – artist – with a female manager – in those pre-consciousness raised days – both in the fields of race and sex – had the audacity to go up against a major corporation to defend his artistic rights – apparently didn’t sit well with the corporate heads. It was a ‘first’ and they made it clear he had to be broken and punished. Surely, you were aware of that.”

All in all, through these letters, we can see the conflict between Glaser and Hammond, and the not-so-subtle attempts by both of them to conceal resentment and animosity. Hammond’s position of power and reputation in the industry allowed him to feign magnanimity, but Glaser had neither the luxury nor the desire to sugar coat her arguments, although we can see from the differences in her brutal draft letter from her significantly more (but not entirely) diplomatic final letter version that she did take these things into consideration. In the end, Glaser once again proved that she would stand up for Garner against even industry giants like John Hammond, in a way that was uniquely her own.

Works Cited

Erroll Garner Archive, 1942-2010, AIS.2015.09, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Goodman, George. "MILES DAVIS: 'I JUST PICK UP MY HORN AND PLAY'." The New York Times. June 28, 1981. Accessed April 27, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/1981/06/28/arts/miles-davis-i-just-pick-up-my-horn-and-play.html.

Ouellette, Dan. "The True Story of Erroll Garner, the First Artist to Sue a Major Label and Win." Variety. December 02, 2019. Accessed April 27, 2021. https://variety.com/2019/music/news/the-true-story-of-erroll-garner-the-first-artist-to-sue-a-major-label-and-win-1203413083/.

#erroll garner#erroll garner tuesdays#jazz#martha glaser#correspondence#music business#columbia records#octave records

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

His Old Tribulations, Our Current Struggle: Remembering Garner in the Current Call to Reform Cannabis Laws

This post was written by Warner Sabio Sr., Graduate Student, Jazz Studies, University of Pittsburgh.

Recently, on April 7th, Virginia’s legislature passed a bill legalizing the possession of small amounts of marijuana, making it the 16th state to do so. Under Virginia’s law, adults can possess an ounce or less of marijuana beginning July 1. Several weeks before, New York passed the Marijuana Regulation and Taxation Act, legalizing the recreational use of marijuana in the state. New York’s legislation also expunges the records of people convicted on marijuana-related charges that are no longer criminalized. These two drug-policy reforms concerning marijuana are a few of the many looking to respond to the disproportionate and often tragic impact previous legislation has had on communities of color.

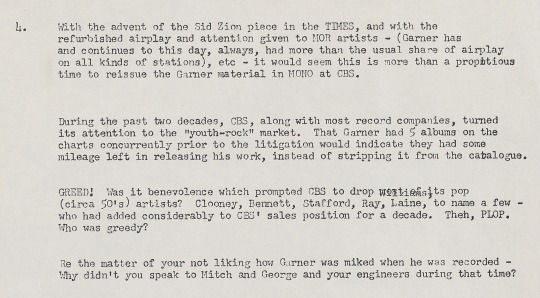

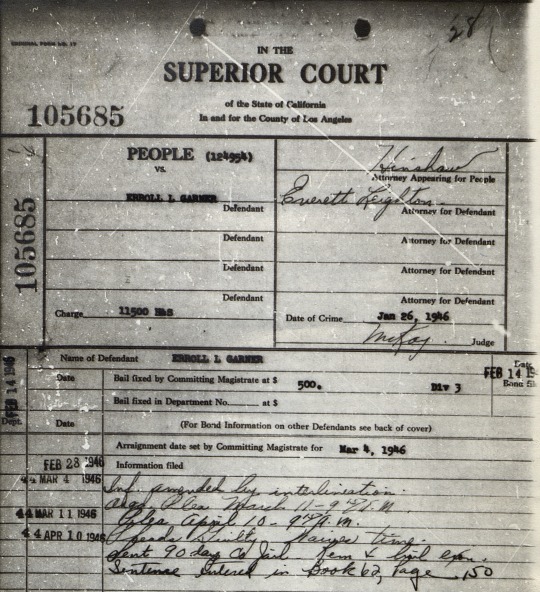

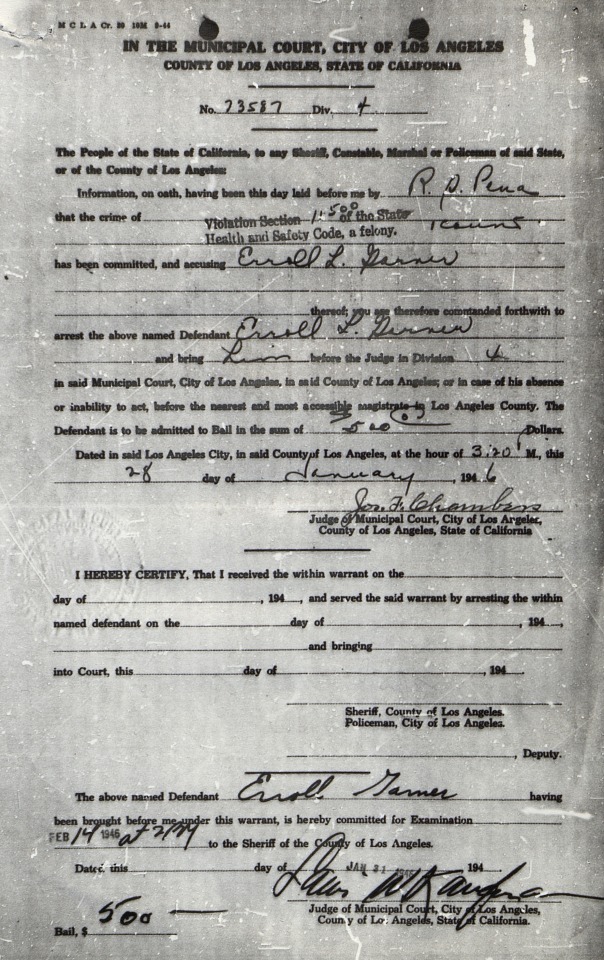

For Erroll Garner, the drug policies regarding marijuana and the enforcement of those laws affected him personally and professionally. On January 26, 1946, Garner was arrested in Los Angeles and charged with violating section 11500 of the California Health and Safety Code—a felony at the time. The State accused Garner of possessing “flowering tops and leaves of Indian Hemp (Cannabis Sativa)” and set bail at $500. According to dollartimes.com, adjusted for inflation, $500 in 1946 is equal to $7,156 in 2021. An excessive amount, it seems, for the non-violent crime he was accused of committing. Nevertheless, on April 10, 1946, Garner pled guilty to the charge and was sentenced to 90 days in the county jail. This incident would mark Garner as a felon and a “dope addict,” in the problematic wording of the language that circulated in press accounts. The distinction would continue to cast its shadow and haunt the pianist for at least another decade, if not the rest of his life.

(Above) Page 1, (Below) Page 2, Page 3, Page 4, and Page 11 from folder “Erroll Garner Personal,” Erroll Garner Archive, 1942-2010, AIS.2015.09, Box 3, Folder 18, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

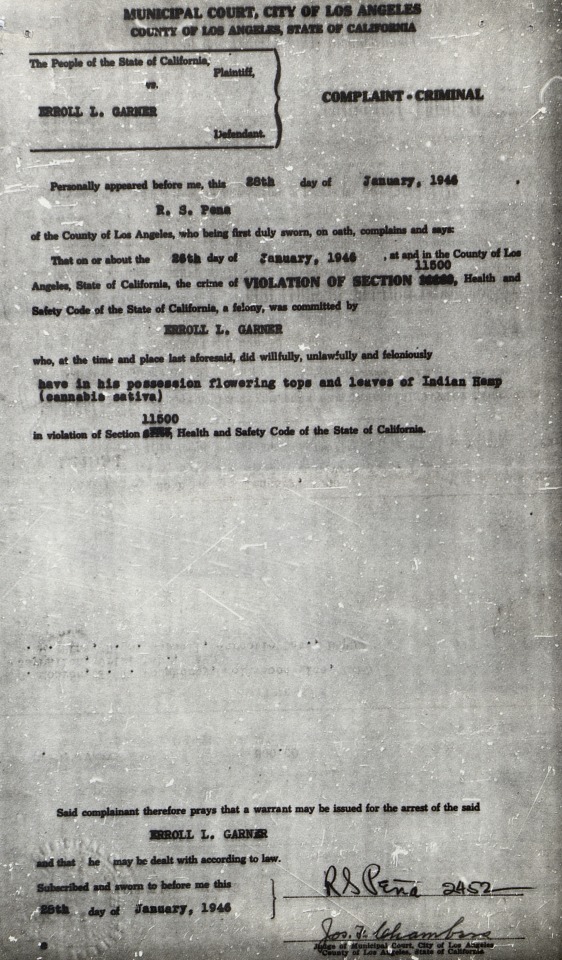

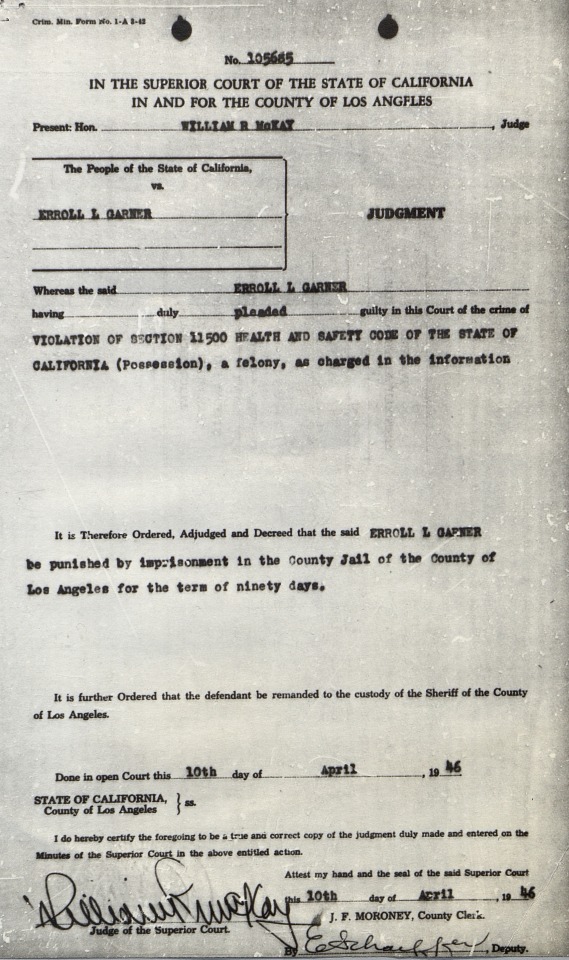

Six years later, after a performance at Mack’s Tavern in Atlantic City on September 12, 1952, the pianist was again arrested and brought up on charges surrounding a marijuana-related drug bust. According to The Baltimore Afro-American, Garner was held “for failure to register as a convicted addict under the state’s narcotics registration law and not for being an actual user of narcotics.”[1] The conviction referred to by New Jersey law-enforcement authorities was based on Garner’s 1946 Los Angeles arrest, which he reportedly informed authorities of at the time. Interestingly, Garner, convicted of possessing marijuana in the initial Los Angeles case, was now branded a “dope addict” in press coverage revolving around the Atlantic City incident.

(Above) Image of the article from The Baltimore Afro-American, Sept. 13, 1952.

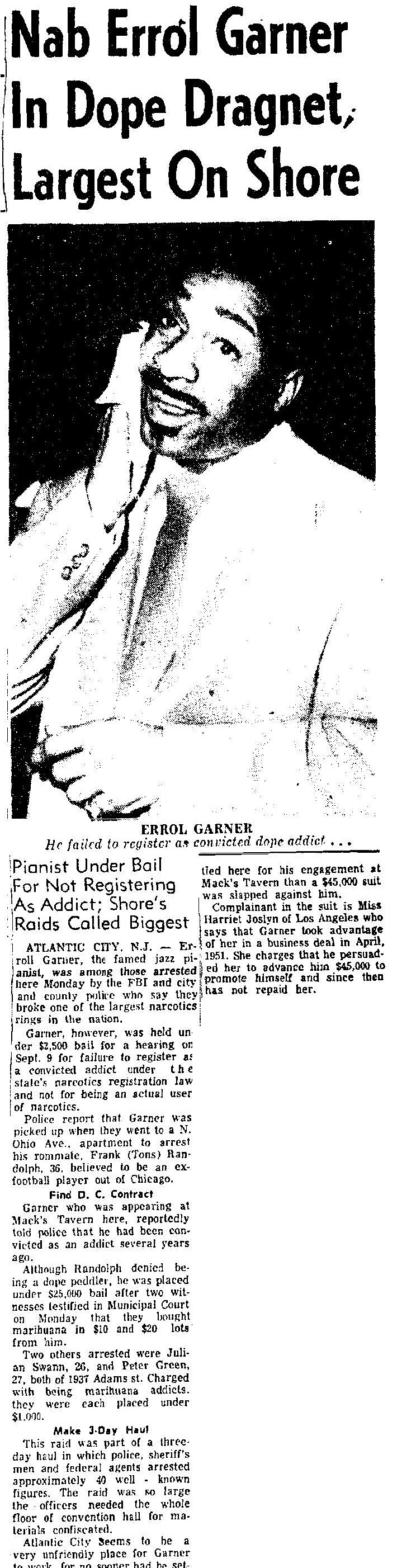

The headline on the front page of September 13, 1952, Pittsburgh Courier read: “ARREST ERROLL GARNER FOR DOPE.” The subhead for the article noted that Garner was “Part of Big-Time Roundup.” The lede stated:

ATLANTIC CITY – Erroll Garner, Pittsburgh’s significant gift to jazz and dexterous piano-playing, was nabbed here in a post-Labor Day roundup of alleged dope addicts and suspects.”[2]

(Above) The Pittsburgh Courier, Sept. 13, 1952.

The Courier also reported that forty-one other suspects were also arrested. One of those arrested included Garner’s roommate and valet, Frank (Tons) Randolph, who was accused of “being a dope peddler.” The Afro-American reported Randolph “was placed under $25,000 bail after two witnesses testified in Municipal Court on Monday that they bought marihuana in $10 and $20 lots from him.” According to dollartimes.com, adjusted for inflation, $25,000 in 1952 is equal to $245,730 in 2021. From the reports, it does not appear that authorities found any weed on Garner or Randolph. Nevertheless, it seems the testimony was enough to warrant the arrests.

It is also interesting to note that the Courier report hinted at a possible ulterior motive for the arrest. Perhaps stemming from the practice of racial profiling of Black men driving nice cars, the paper reported, “police are alleged to have stated that Garner has been driving around Atlantic City in a 1952 Cadillac and a woman, described by some as his wife has been driving a Chrysler.”

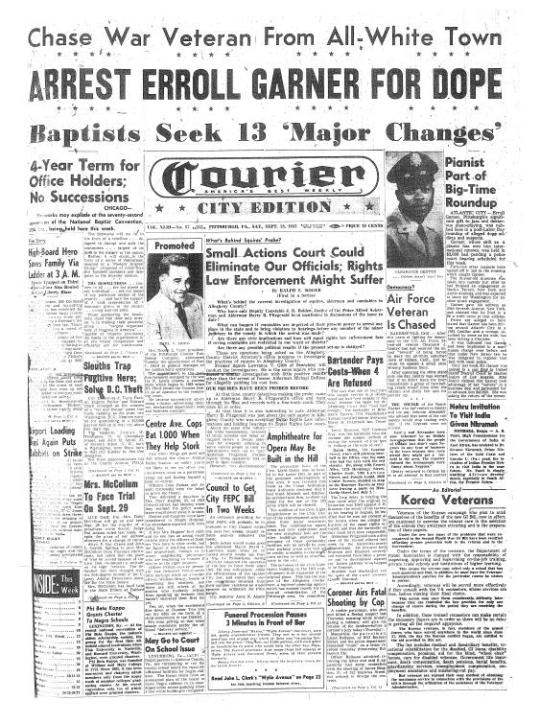

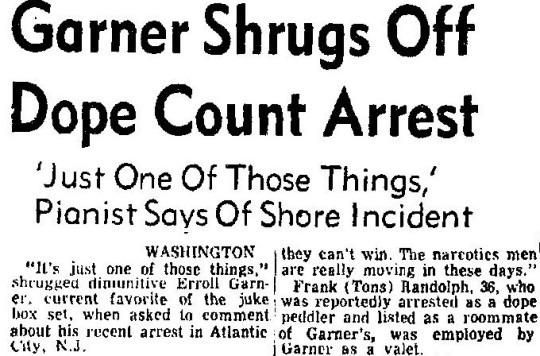

In a follow-up story on September 20, The Afro-American interviewed Garner about the arrest. The headline read: “GARNER SHRUGS OFF DOPE COUNT ARREST: ‘Just One Of Those Things,’ Pianist Says of Shore Incident.”[3] Garner discusses the Los Angeles case in the piece, affirming his conviction (saying it took place in 1943) and stating he was “sentenced to 45 days to an honor farm.” Garner elaborated:

“It was all a ‘frame.’ I was turned in by a fellow whose job I took in a night club in which I was playing. The guy was salty and squealed. But I am not complaining because it did happen. At the time, I was a youngster and went around with a bunch of wild guys.”

(Above) Headline from The Baltimore Afro-American, Sept. 20, 1952.

As for the Atlantic City incident, Garner was quoted as saying he “was through with that kind of stuff now” and had “too much to lose.” However, he was critical of the publicity, stating, “the only thing is that I was the least involved and got most of the publicity. This is one time that I wished I was digging ditches.”

Almost a month after the Atlantic City arrest, on October 11, 1952, The Afro-American reported that Garner was fined $50 for failure to register as a dope addict.[4] The case was thereafter dismissed, and Garner “filed the necessary registration forms in compliance with the local ordinance. According to the paper, the incident had left Garner feeling “disturbed” and “embarrassed.” Garner was forced to cancel several weeks of bookings “in order to permit him to rest” because he was “suffering from nervous exhaustion.” As for Randolph and the others arrested that night, my limited search came up empty as to how they fared.

On Jan.17, 1953, the Courier reported that a case involving Garner’s arrest in St. Louis on New Year’s Eve was tossed. Garner was charged with possession of narcotics.[5] The paper said, “Garner’s case was thrown out of court because the officers did not have a warrant when the arrest was made.” Garner’s attorney, however, clarified that the basis of the arrest was “a crank telephoned St. Louis police that the pianist had carried narcotics from New York to St. Louis in his automobile. It was revealed that Garner had arrived in this city by plane.”

For Pittsburgh-born Garner, professional success could not shield him from the insatiable appetite to punish that has driven much of the nation’s drug policies for decades. Major players in the formation of these early policies are uniquely linked to Garner geographically. Harry J. Anslinger, who served as the first commissioner of the U.S. Treasury Department’s Federal Bureau of Narcotics, was an Altoona, PA native. Pittsburgh’s-own Andrew Mellon, the uncle of Anslinger’s wife, appointed him to the post. Mellon, at the time of Anslinger’s appointment, was the Treasury Secretary.

According to The Economist:

“The drafters of the Harrison Act of 1914, the first federal ban on non-medical narcotics, played on fears of ‘drug-crazed, sex-mad negroes.’ And the 1930s campaign against marijuana was coloured by the fact that Harry Anslinger, the first drug tsar, was appointed by Andrew Mellon, his wife’s uncle. Mellon, the Treasury Secretary, was banker to DuPont, and sales of hemp threatened that firm’s efforts to build a market for synthetic fibers. Spreading scare stories about cannabis was a way to give hemp a bad name. Moral outrage is always more effective if backed by a few vested interests.”[6]

According to law professor Michael Vitello, “while the Harrison Act did not include a prohibition against marijuana, its framework would become the model for Congress’s first efforts to criminalize marijuana.”[7]

(Above) Harry J. Anslinger served as the first commissioner of Treasury Department’s Federal Bureau of Narcotics. Image from the Associated Press.

Driven by stereotypes, some framers of early U.S. drug policies linked the usage of both marijuana and cocaine to marginalized communities and racialized “fringe groups like pimps, prostitutes, and day laborers” and “uppity Southern blacks and race-mixing drug parties.”[8] Concerning Anslinger’s beliefs, Vitello states:

“Finding racist quotations attributed to Anslinger is easy and a reminder of how ingrained racist language was in this country. Here are a few choice quotations: “Reefer makes darkies think they’re as good as white men”; “Marihuana influences Negroes to look at white people in the eye, step on white men’s shadows and look at a white woman twice”; and “There are 100,000 total marijuana smokers in the U.S., and most are Negroes, Hispanics, Filipinos and entertainers. Their Satanic music, jazz and swing result from marijuana use. This marijuana causes white women to seek sexual relations with Negroes, entertainers and any others.”[9]

These antiquated and racist beliefs would vibrantly pulsate through the heart of drug laws for generations. Unfortunately, Garner’s experience was not isolated or rare. For Garner, the arrests and court cases must have been taxing. His experience speaks for many people caught up in the web of draconian drug laws pervading the justice system. The growing frustration has led to calls for change.

As previously mentioned, recent efforts have yielded changes to drug policy concerning marijuana across the United States. To date, sixteen states, two territories, and the District of Columbia have legalized small amounts of marijuana for adult recreational use. Twenty-seven states have decriminalized weed, meaning, “small, personal-consumption amounts are a civil or local infraction, not a state crime (or are a lowest misdemeanor with no possibility of jail time).”[10] However, more needs to be done to undo the gross injustice that lopsided enforcement has produced. It is a flawed system of policies and laws that impacted Garner then and thousands today. We must resolve the discordant tones struck by the framers of foundational drug war policies, the effects of which still resonate and impact civil society today.

Works Cited

Erroll Garner Archive, 1942-2010, AIS.2015.09, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

“Arrest Erroll Garner For Dope: Pianist Part of Big-Time Roundup.” Pittsburgh Courier (Pittsburgh, Pa.), September 13, 1952: 1.

Bender, Steven W. “Joint Reform? The Interplay of State, Federal, and Hemispheric Regulation of Recreational Marijuana and Failed War on Drugs.” Albany Law Environmental Outlook 6, no. 2 (2013): 359–.

“Errol Garner Case Thrown Out of Court.” Pittsburgh Courier (Pittsburgh, Pa.), January 17, 1953: 1.

“Errol Garner Pays $50 Fine: Failed To Register As Dope Addict.” Baltimore Afro-American (Baltimore, Md), October 11, 1952: 9

“Garner Shrugs Off Dope Count Arrest: ‘Just One Of Those Things,’ Pianist Says Of Shore Incident.” Baltimore Afro-American (Baltimore, Md), September 20, 1952: 3

Gootenberg, Paul. Andean Cocaine: The Making of a Global Drug. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

“‘How did we get here?’ A Survey of Illegal Drugs.” Economist, July 28, 2001, p. 4. The Economist Historical Archive, 1843-2015 (accessed April 13, 2021). https://link-gale-com.pitt.idm.oclc.org/apps/doc/GP4100323851/ECON?u=upitt_main&sid=ECON&xid=779492d4.

“Pianist Under Bail For Not Registering As Addict; Shore’s Raids Called Biggest.” Baltimore Afro-American (Baltimore, Md), September 13, 1952: 1

National Conference of State Legislatures website, https://www.ncsl.org/research/civil-and-criminal-justice/marijuana-overview.aspx

Vitiello, Michael. “Marijuana Legalization, Racial Disparity, and the Hope for Reform.” Lewis & Clark Law Review 23, no. 3 (2019): 789-822.

[1] “Pianist Under Bail For Not Registering As Addict; Shore’s Raids Called Biggest,” Baltimore Afro-American (Baltimore, Md), September 13, 1952.

[2] “Arrest Erroll Garner For Dope: Pianist Part of Big-Time Roundup,” Pittsburgh Courier (Pittsburgh, Pa.), September 13, 1952.

[3] “Garner Shrugs Off Dope Count Arrest: ‘Just One Of Those Things,’ Pianist Says Of Shore Incident,” Baltimore Afro-American (Baltimore, Md), September 20, 1952.

[4] “Errol Garner Pays $50 Fine: Failed To Register As Dope Addict.” Baltimore Afro-American (Baltimore, Md), October 11, 1952.

[5] “Errol Garner Case Thrown Out of Court.” Pittsburgh Courier (Pittsburgh, Pa.), January 17, 1953: 1.

[6] “‘How did we get here?’ A Survey of Illegal Drugs,” Economist, July 28, 2001.

[7] Michael Vitiello, “Marijuana Legalization, Racial Disparity, and the Hope for Reform,” Lewis & Clark Law Review 23, no. 3 (2019), 794.

[8] Paul Gootenberg, Andean Cocaine: The Making of a Global Drug, Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2008, 193.

[9] Vitiello, “Marijuana Legalization,” 799.

[10] National Conference of State Legislatures website, https://www.ncsl.org/research/civil-and-criminal-justice/marijuana-overview.aspx

#erroll garner tuesdays#erroll garner#criminalization#newspapers#cannabis laws#drug policy#harry anslinger#racism

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mementos of Exhaustion

This post was written by YuHao Chen, graduate student in ethnomusicology, University of Pittsburgh.

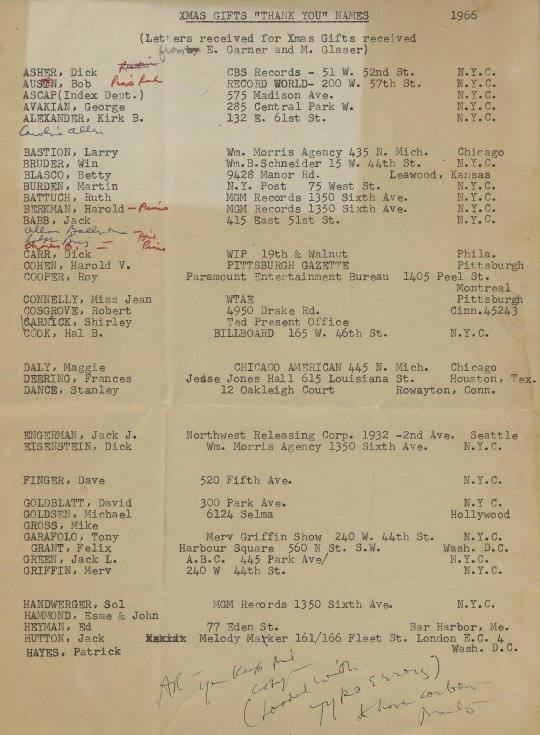

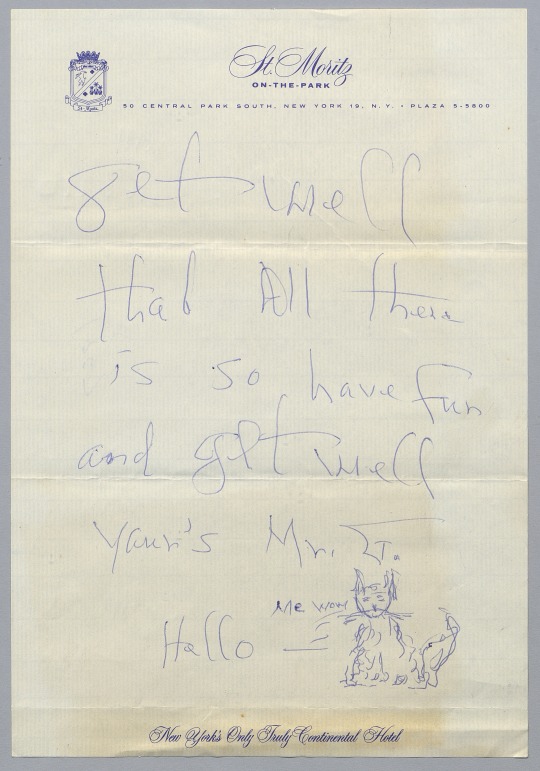

Christmas season at Martha Glaser’s management office was quite a juggling act. It was colored by the daunting task of preparing gifts for a plethora of business correspondence and services all over the country that, in one way or another, supported the success of Erroll Garner's jazz career and Octave Records, his joint enterprise with Glaser. From big-name news press, record companies, and piano dealers to behind-the-scenes personnel such as bellmen, operators, desk clerks, and maids, the names went on and on. Lists like this one permeate Glaser’s daily notes around Christmastime, revealing the extent to which the acrobatics of professionalism must be carried into the New Year, even when the corporate world seemed to doze off momentarily. As the year would wind down, Glaser’s firm hummed with business as usual.

Image from folder “Martha Glaser Daily Notes,” Erroll Garner Archive, 1942-2010, Box 73, Folder 5, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

However, the 1968 Christmas season was unlike any other.

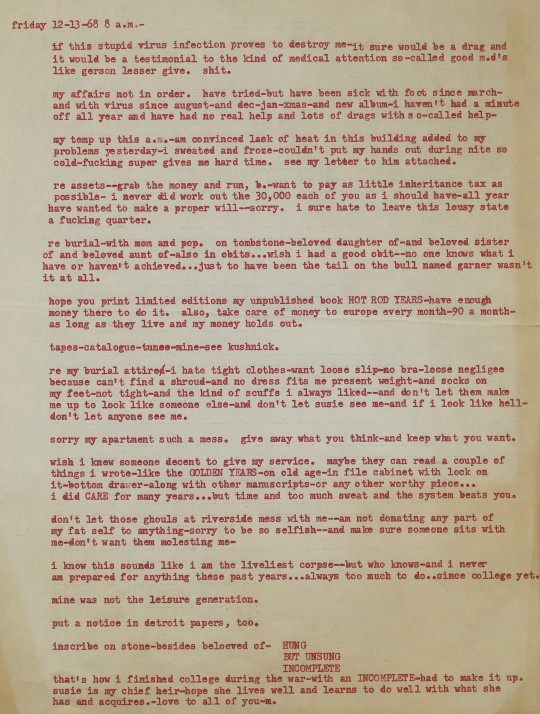

Glaser was ill. In fact, she had been sick “with [a] virus since August.” By December she had run out of steam and was teeming with spite, fury, pride, repentance, and remorse among other complicated feelings—all shoved up against the uncomfortable truth that she had been overworking with pain since college. Her complex interiority spilled out onto a note dated Friday December 13th, 1968 that cracked open a crevice for an unsung voice. With fumbling steps, she appeared exhausted by her own heroism. For a moment, she loosened her posture as a staunch businesswoman, whose shadow was cast so laboriously onto the career of “the bull named Garner.”

Image from folder “Martha Glaser Daily Notes,” Erroll Garner Archive, 1942-2010, Box 73, Folder 5, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Readers familiar with Glaser’s writing will likely recognize her idiosyncratic voice in this personal note. Previous blog posts have commented on the distinctly brisk, unapologetically blunt, and stubbornly snappy tone that is Glaser’s. See, for example, The “Swinging City Revolution”: Garner in the Land of the Rolling Stones, Martha Glaser Fights for Garner’s ASCAP Holdings, Martha’s Private Writings, and Three Shades of Martha. In the face of the still discriminatory American music industry, Glaser’s fierceness was indeed what it took for her in the mid-twentieth century to procure the professional recognition she deserved.

In comparison, the December 13th private note appears markedly different from Glaser’s other writings in the archive in that it seems to withdraw from the career game that she is so adept at playing. Under what normal circumstance would we ever expect lamentation like “but time and too much sweat and the system beats you” coming from a powerhouse like Glaser? At the same time, her vehement verbal attack against a line of adversaries—the virus, lousy medical attention, state tax, tight clothes, and “those ghouls at riverside”— is reminiscent of her typical professional demeanor. It is as if the prospect of dying, or her realization of an existential pushback, only inspired her to remain the witty fighter—or “the liveliest corpse,” as she puts it—up to her last dying breath.

Glaser seems undeterred by the collapse between the professional and the private amidst high fever and shivering hands. Within the space of a single typed page, she sprints across a variety of contexts: her illness, business, assets, complaints, relationship with Garner, wishes, worth, tombstone, afterlife, and younger self. And she does so with such speed and abandon, as though affirming the cliché that upon dying one’s entire life would flash before one’s eyes. If that is indeed the case, what does Glaser’s note tell us about her life? Should the note be considered a heart-wrenching meditation on death? Or a tongue-in-cheek commentary on the capitalist hold that monetizes her last fragments of unfulfilled dreams?

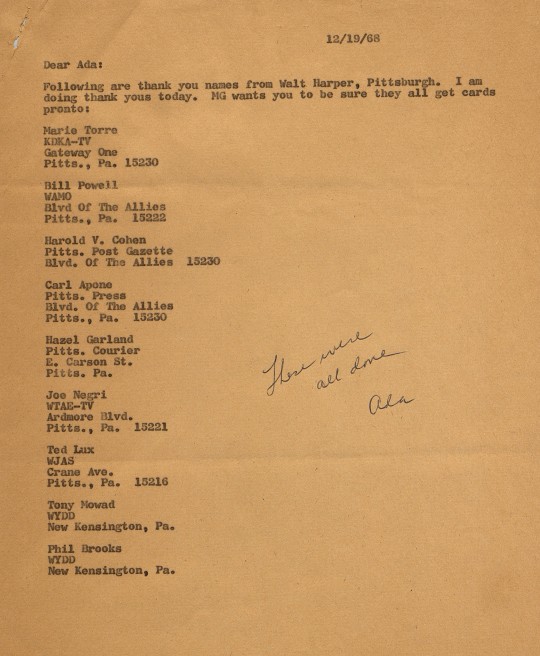

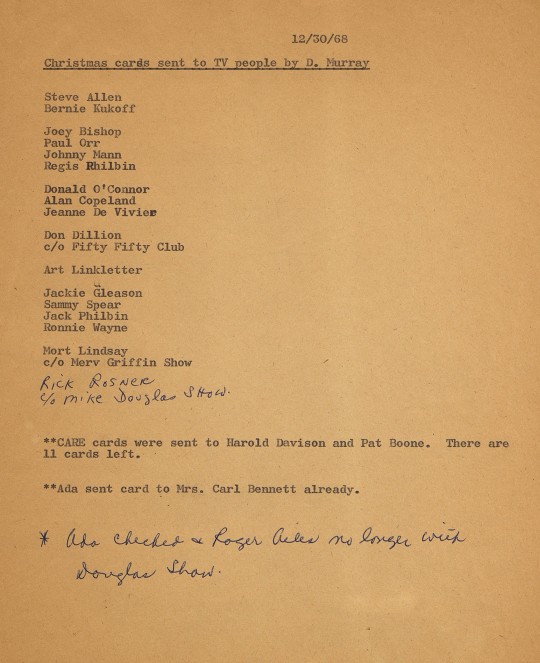

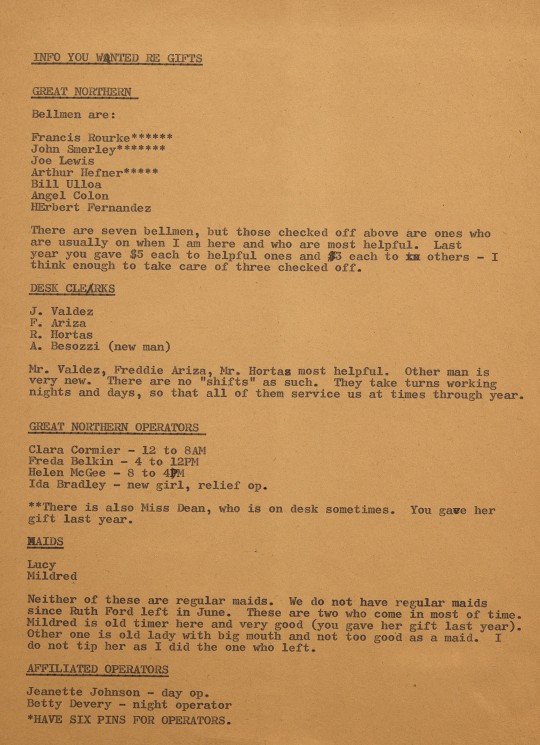

But even as Glaser undertook such ruminations, the holiday season marched on. Her office memos around Christmas illustrate the kind of professional responsibilities that she typically bore as an unwavering advocate for Garner’s music. Piles of thank-you cards and gifts stuffed her Christmas season, waiting to be mailed out. Archival materials from 1968 show that the seasonal business ritual began around December 7th and lasted all the way to the 30th, with Glaser’s assistants Ada Roeter and D. Murray reporting throughout the month on their progress of sending out holiday greetings in addition to managing routine tasks like handling contracts, calls, and files.

Image from folder “ Martha Glaser Incoming Correspondence 1966-1969,” Erroll Garner Archive, 1942-2010, Box 69, Folder 12, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Image from folder “ Martha Glaser Incoming Correspondence 1966-1969,” Erroll Garner Archive, 1942-2010, Box 69, Folder 12, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Image from folder “ Martha Glaser Incoming Correspondence 1966-1969,” Erroll Garner Archive, 1942-2010, Box 69, Folder 12, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

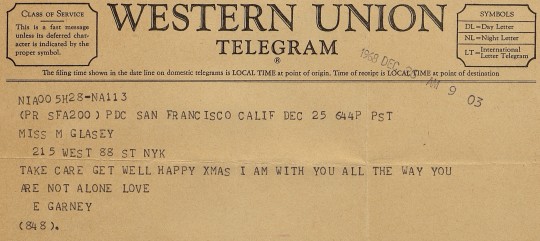

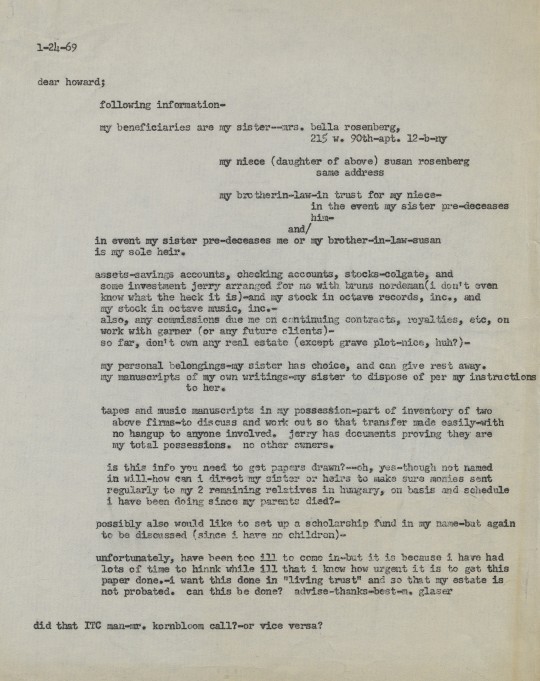

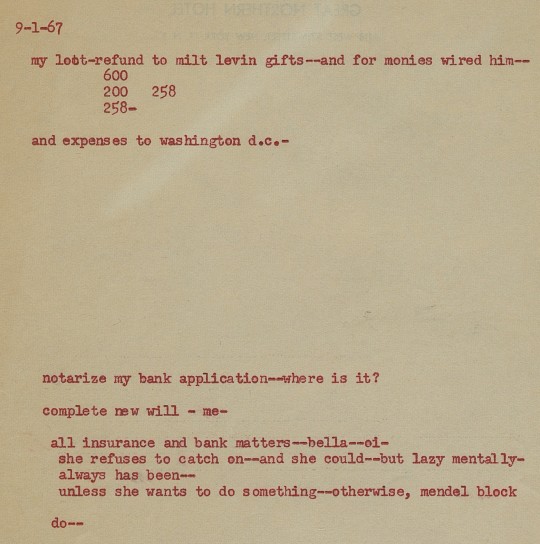

The materials held in the archive seem to suggest that Glaser composed very few business memos that Christmas, likely because she was too ill to work. On Christmas Day, she received the following telegram from Garner: “TAKE CARE GET WELL HAPPY XMAS I AM WITH YOU ALL THE WAY YOU ARE NOT ALONE.” On January 24th the following year, she wrote to Howard (presumably Howard Beldock, one of her attorneys in the late 1960s) to convey details about her own personal beneficiaries and assets, a process which was already on her mind as early as September 1st, 1967, when she wrote in her daily notes “complete new will – me –.”

Image from folder “Correspondence between Erroll Garner and Martha Glaser,” Erroll Garner Archive, 1942-2010, Box 3, Folder 5, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Image from folder “Martha Glaser Daily Notes,” Erroll Garner Archive, 1942-2010, Box 73, Folder 5, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Image from folder “Martha Glaser Daily Notes,” Erroll Garner Archive, 1942-2010, Box 73, Folder 5, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

With these surrounding events in mind, we might begin to see Glaser’s note of December 13th as an outburst of exhaustion irritated by her longstanding battles in the professional arena. Glaser’s feistiness seems so well-rehearsed in this note because dying, like other events in life, was so bound up with professional responsibilities that it demanded her to navigate mortality with the business strategies she mastered. Her sarcastic remark at her own dying does not necessarily neutralize its possibility but, rather, exaggerates its poignancy, exposing the range of expression available to her through rounds after rounds of tough negotiation in music industry and in life.

Which leaves us with one final question: who was Glaser writing for? While this note is intensely private, there is also a sense of dialogue and an implied audience. She wrote sentences like “hope you print limited editions my unpublished book” and “sorry my apartment such a mess. give away what you think—and keep what you want.” Who is the “you”? Is it the nosey neighbor who might discover the hypothetically dead body of Glaser? The unnamed relative to whom she gave burial instructions? Or anyone who might stumble upon her death note? Glaser lived well into the millennium; she died in 2014. Yet her note from 1968 continues to lay silently among the mass of the Erroll Garner Archive, like a corpse waiting to be found. As readers of Glaser’s memento, we are not unlike that unnamed relative, that coincidental reader who, upon entering her embalmed past, expected to rescue a yellowed body—only to catch lines upon lines of redness, inscribing an undying voice gregariously ruminating different life endings, suspended within the tomb of time forever pivoting.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The “Swinging City Revolution”: Garner in the Land of the Rolling Stones

This post was written by Deanna Witkowski, pianist-composer, graduate student in Jazz Studies at the University of Pittsburgh, and author of Mary Lou Williams: Music for the Soul (Liturgical Press, August 2021).

In May and June of 1966, Erroll Garner played in London for several weeks with his longtime triomates, bassist Eddie Calhoun and drummer Kelly Martin. Leslie (Les) Perrin and Associates, publicity firm for the Rolling Stones and other big name pop acts, served as Garner’s publicist for his English tour dates. In many photos from 1966-1970, Perrin is seen with the Stones, Frank Sinatra, and Joni Mitchell. Mitchell’s website includes a feature page on Perrin with this article from a tabloid-looking paper entitled “Weekend— Feb. 25-Mar. 3, 1970.”

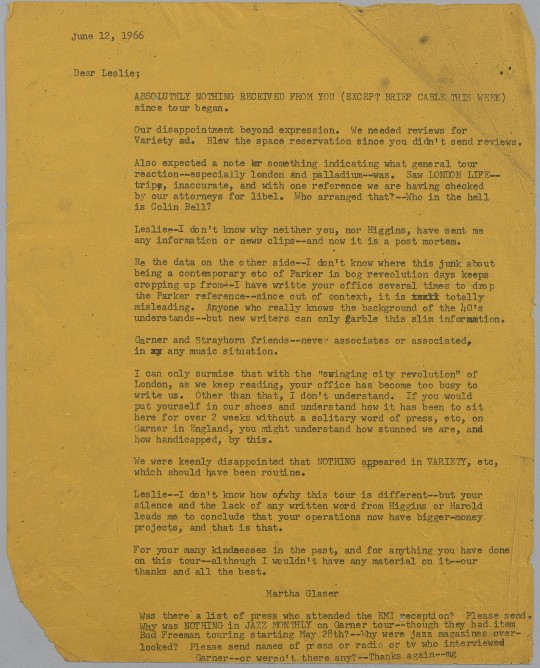

On June 12, after Garner had already been in England for over two weeks, Glaser typed a letter to Perrin, chastising him for not contacting her with any press coverage of Garner’s tour dates thus far—or, for that matter, with any news at all. Dispensing with formal niceties, Glaser begins her correspondence using all capital letters: “ABSOLUTELY NOTHING RECEIVED FROM YOU (EXCEPT BRIEF CABLE THIS WEEK) since tour began. Our disappointment beyond expression. We needed reviews for Variety ad. Blew the space reservation since you didn’t send reviews.”

Image from folder “Correspondence from Leslie Perrin (Associated LTD. UK Bookers),” Erroll Garner Archive, 1942-2010, Box 1, Folder 119, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

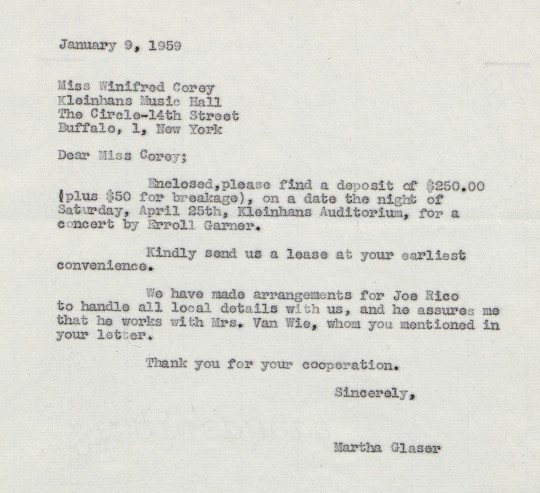

As in my earlier post on his 1959 date at Kleinhans Music Hall in Buffalo, Glaser’s letter shows the interdependence of multiple behind-the-scenes players in shaping Garner’s career. Glaser cannot move forward with future publicity needs until Perrin generates publicity for the current tour and communicates the results of that publicity with her.

Glaser pulls no punches in her critique of Perrin—and is compelled to fight these battles so that Garner can focus on his own labor: creating music. Two-thirds of the way through her letter, she writes, “I can only surmise that with the ‘swinging city revolution’ of London, as we keep reading, your office has become too busy to write us . . . Leslie—I don’t know how or why this tour is different—but your silence and the lack of any written word from [Jack] Higgins or Harold [Davison] leads me to conclude that your operations now have bigger-money projects, and that is that.”

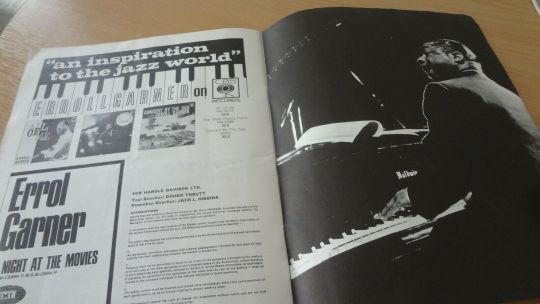

The two other names that Glaser mentions, Jack Higgins and Harold Davison, are additional players in Garner’s British tour production and publicity. Both names appear on the final page of this program from June 11, 1966:

(Above) “Erroll Garner Souvenir Brochure London, November 6, 1966.” PicClick UK. Accessed April 5, 2021. https://picclick.co.uk/1966-Erroll-Garner-Souvenir-Brochure-London-11-06-1966-373506567730.html.

Davison is listed as being the concert presenter, with Higgins handling “promotion direction” and Dougie Tobutt handing “tour direction.”

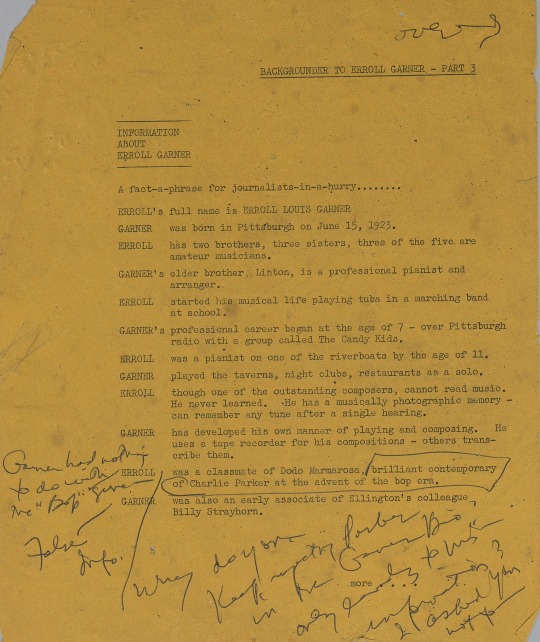

Enclosed with her letter Glaser includes a marked-up copy of a document titled “Backgrounder to Erroll Garner,” a one-sheet apparently created by Perrin for local press reporters. Claiming to provide “a fact-a-phrase for journalists-in-a-hurry,” the document is a list of twelve bullet-point facts about Garner.

Image from folder “Correspondence from Leslie Perrin (Associated LTD. UK Bookers),” Erroll Garner Archive, 1942-2010, Box 1, Folder 1119, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

In response to two of the points, Glaser pens handwritten corrections:

Where the one-sheet reads: “ERROLL was a classmate of Dodo Marmarosa, brilliant contemporary of Charlie Parker at the advent of the bop era.”

Glaser responds:

“Garner had nothing to do with the “bop” scene—“ and “Why do you keep repeating Parker in the Garner bio?’” The truth is that Garner was indeed a childhood friend of bop pianist Marmarosa, who recorded with Parker on numerous occasions. Garner recorded with Parker as well, but was not a bop pianist, while Marmarosa was closely identified with that musical style.

And where the sheet reads:

“GARNER was also an early associate of Ellington’s colleague Billy Strayhorn.”

Glaser simply writes: “False info.”

In her letter, she goes into further detail on each point, writing, “I don’t know where this junk about being a contemporary etc of Parker in bog (sic) reveolution (sic) days keeps cropping up from . . .out of context, it is totally misleading.” And to the second point: “Garner and Strayhorn friends—never associates or associated, in any music situation.”

Perrin did respond to Glaser. Although his reply is undated, it likely followed soon after, as he references recent British concert dates and signs off promising “more tomorrow.” Most importantly, he sends ten quotes on Garner’s appearances from press including Melody Maker, the Evening News, and New Musical Express. He only includes this material, however, after making a snide comment: “My dear Martha, It is a warm afternoon, the shadows are creeping across the desk, and I am asking myself, “Do you think that Martha came to the Albert Hall after all? Because the concert was at the Royal Festival Hall?”

Image from folder “Correspondence from Leslie Perrin (Associated LTD. UK Bookers),” Erroll Garner Archive, 1942-2010, Box 1, Folder 119, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Snide comment or not, Perrin produced the results that Glaser was asking for. This snapshot of two documents shows how sharp and direct she had to be in order to acquire the material she needed to continue her own work in moving Garner’s career forward.

————————

For additional listening:

Check out some of the the Garner albums included on the final page of the concert ad shown in the concert program shown above:

CBS ad: Concert by the Sea 1955 https://www.errollgarner.com/listen-new (scroll down)

The Most Happy Piano 1956

youtube

(Above) Audio for “Full Moon and Empty Arms” off The Most Happy Piano by Erroll Garner, originally released in 1957 by Columbia Records.

EMI ad: A Night at the Movies 1965— original liner notes and audio samples at https://www.errollgarner.com/anightatthemovies-ors

Listen to the all-of-five-seconds “Newsreel Tag (Paramount on Parade)”

youtube

(Above) Audio for “Newsreel Tag (Paramount on Parade)” off A Night at the Movies by Erroll Garner, re-relseased by Octave Records in 2019.

Works Cited:

Erroll Garner Archive, 1942-2010, AIS.2015.09, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Erroll Garner - Topic. “Full Moon and Empty Arms.” YouTube Video, 4:19. July 30, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dxlVnUXJApY.

Erroll Garner - Topic. “Newsreel Tag (Paramount on Parade).” YouTube Video, 0:08. October 17, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s0hqVABcPSk

prettyjohn888. “1966 Erroll Garner Souvenir Brochure London 11/06/1966 • £4.00.” PicClick UK. Accessed April 5, 2021. https://picclick.co.uk/1966-Erroll-Garner-Souvenir-Brochure-London-11-06-1966-373506567730.html.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Martha Glaser fights for Garner’s ASCAP holdings

This post was written by Adam Lee, graduate student, Jazz Studies, University of Pittsburgh.

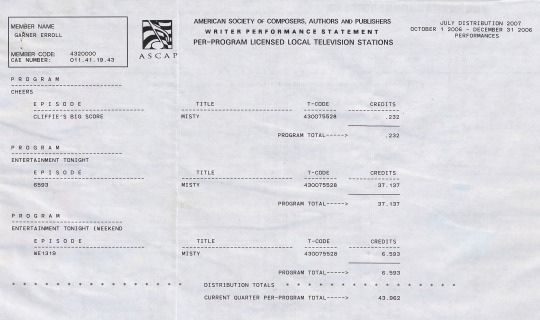

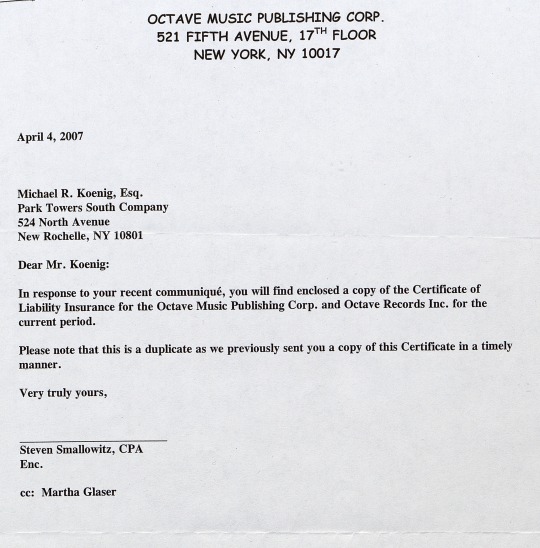

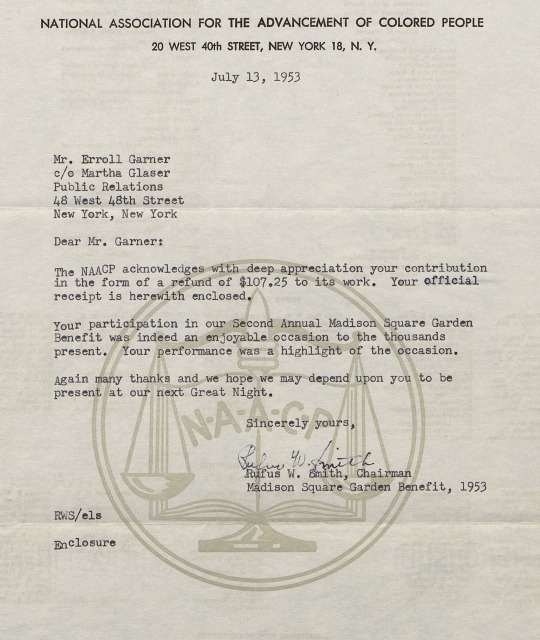

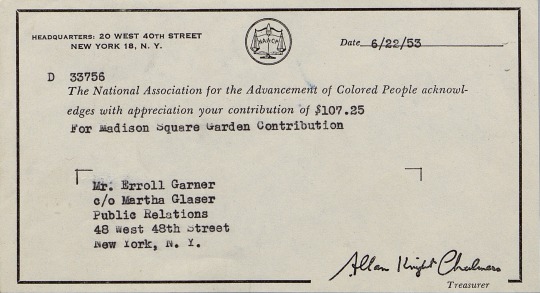

Martha Glaser continued to manage Erroll Garner’s business affairs long after the pianist’s death in 1977. Contained in the Erroll Garner Archive are records of correspondence between Garner and the American Society of Composers, Authors, & Publishers (ASCAP), many of which cover decades of rights management for Garner’s estate. Many of these records are handwritten notes referencing which compositions are held by which rights management companies, and what the exact reference numbers are. Others are official typed documents with similar information addressed to or from Martha Glaser in reference to the legal copyright standing of various Erroll Garner compositions. These all show a carefully hands-on approach that Glaser took to managing the rights and royalties of these pieces for Garner, she knew exactly which pieces were held by ASCAP down to their catalog number and kept records of this information. Other documents exist in the archive that support Glaser’s protection of these rights pertaining to companies other than ASCAP, although in the interest of focus I have only chosen to use ASCAP documents for today’s post.

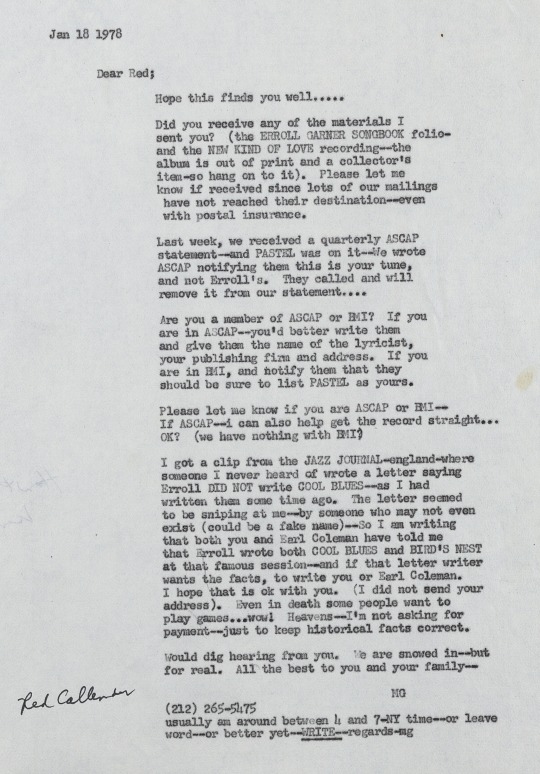

Glaser not only managed Garner’s works, but on at least one occasion, she protected another artist, Red Callender, when his composition “Pastel” was misattributed to Garner in an ASCAP copyright statement. Glaser reached out to ASCAP and had them attribute the piece correctly, and corresponded with Callender on January 18, 1978 about the mistake, inquiring if he was registered with ASCAP or not. This same document reveals that, at least as of 1978, no Garner pieces were held by rival rights company Broadcast Music Inc. (BMI).

Image from folder “Correspondence from Red Rodney,” Erroll Garner Archive, 1942-2010, Box 1, Folder 126, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

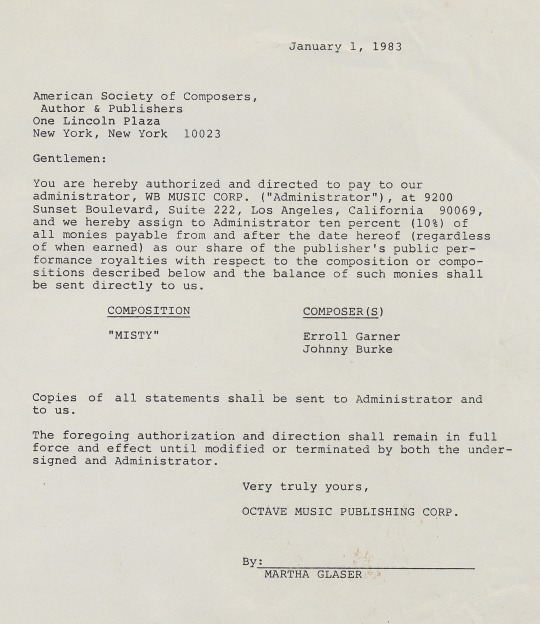

Glaser not only protected Garner’s holdings during his life, but also posthumously managed and protected his copyright ownership. Take for example, this notice to ASCAP assigning rights administration to “WB MUSIC CORP.” from January 1, 1983 of what is most certainly Garner’s most famous composition “Misty”:

Image from folder “Correspondence from ASCAP,” Erroll Garner Archive, 1942-2010, Box 1, Folder 5, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

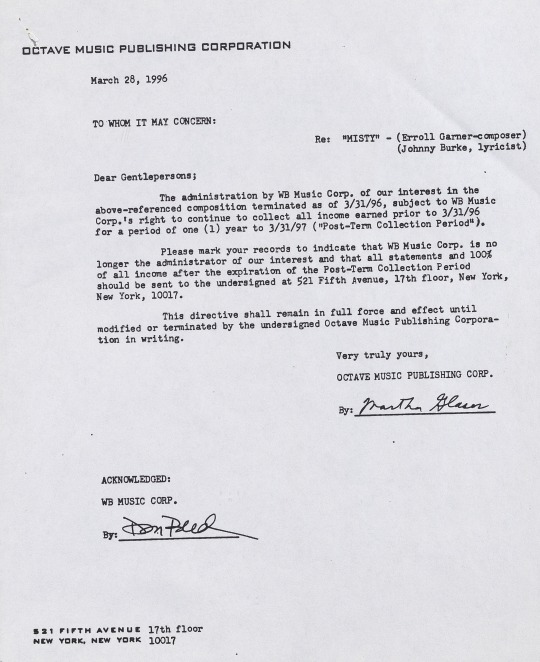

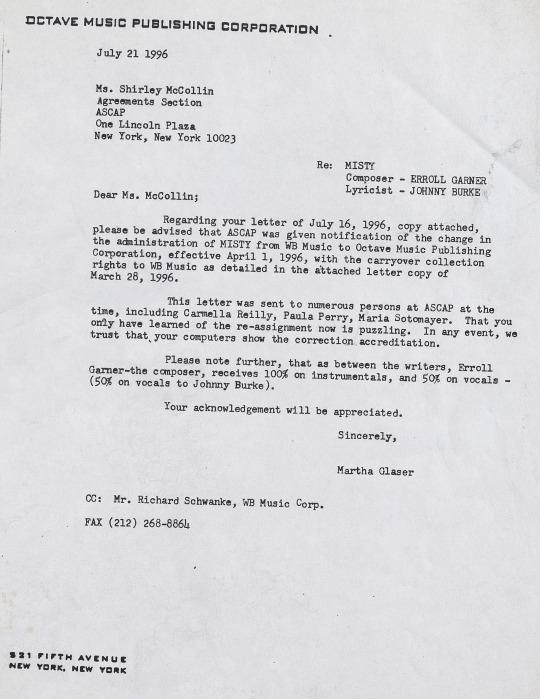

Glaser also oversaw the termination of that above agreement with WB Music Corp a full fifteen years later, with correspondence detailing the cessation of the contract going to both WB Music and ASCAP effective March 31, 1996.

Image from folder “Correspondence from ASCAP,” Erroll Garner Archive, 1942-2010, Box 1, Folder 5, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.