#sportshistory

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Jason Williams was a magician with the 🏀

On this day in 1999, he hit a cutting Chris Webber with this beautiful behind-the-back dime 🔥

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mean Joe Green. 9" x 12" acrylic on canvas board. https://jschulerart.etsy.com/listing/1399732176

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Celebrating tennis legend Althea Gibson, the first Black woman to win a Grand Slam Championship. In 1956 Gibson won the French Open, and in 1957 and 1958, Gibson won at Wimbledon and the US Open. #womenshistorymonth #goodblacknewscalendar #sportshistory #tennis (📸: @librarycongress collection; Flushing Meadows statue via @usopen) https://www.instagram.com/p/CqIqtz5rq6W/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

70 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Women's World Games, held in 1922, were a groundbreaking response to the exclusion of women from the Olympics. A pivotal moment in sports history! 🏅💪

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pakistan's Bronze Medal Journey in the Asian Champions Trophy 🇵🇰🏅

The Pakistan hockey team has done it! They’ve secured a bronze medal in the Asian Champions Trophy with a phenomenal 5-2 victory over South Korea. This match was a testament to their resilience and teamwork. With standout performances from Sufyan Khan and Hannan Shahid, the team has reignited national pride in hockey.

This win is not just about the medal; it’s about inspiring future generations and bringing hockey back into the spotlight in Pakistan. Let’s celebrate our champions! 🎉

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

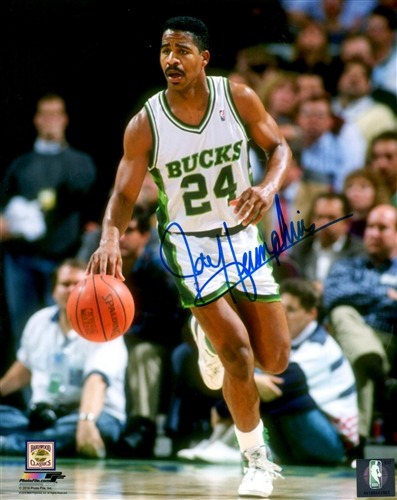

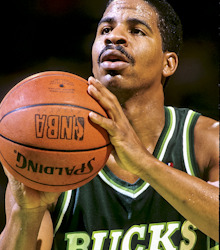

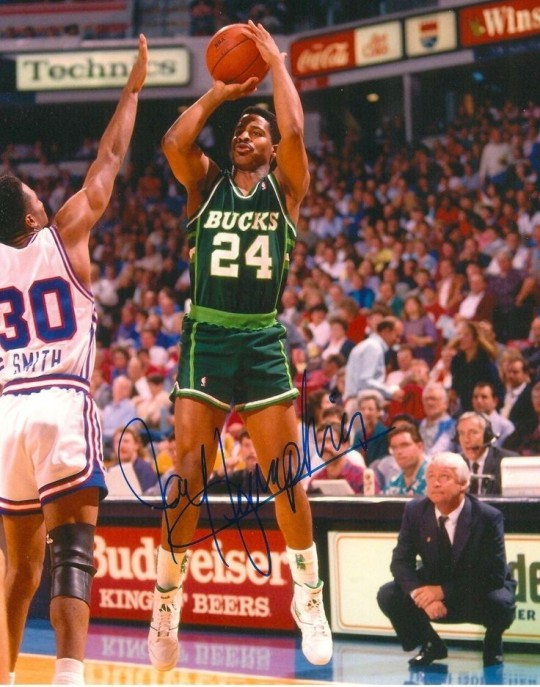

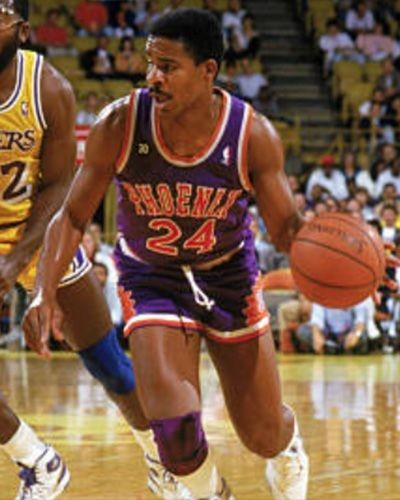

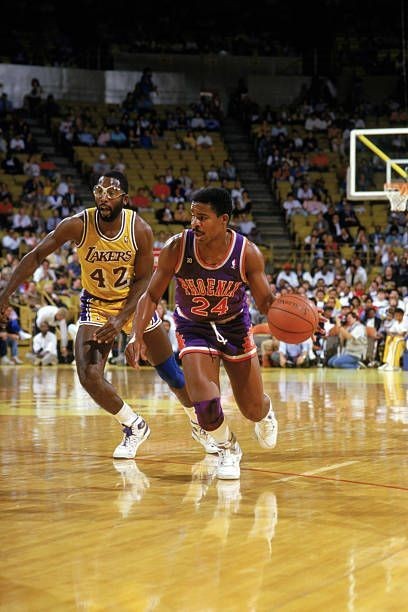

Jay Humphries Stills

Born: Los Angeles, CA

Height: 6'3"

Weight: 185lbs

College: Colorado

Drafted: 1st Round - 13th Pick

#nba#basketball#nba history#sports#carmelo anthony#magic johnson#uncle drew#charlotte hornets#hornets#green bay wisconsin#green bay packers#utah jazz#milwaukee bucks#vintage hoops#vintage basketball#vintage#micheal jordan#80s basketball#basketball cards#collectibles#cool#sportshistory#sports girl#sports nerd#basketball nerd#wnba#jay humphries

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tennis Queens: Top 10 Greatest Female Players of All Time

Picking the greatest of all time is always a tough call, and women's tennis is no exception. From power hitters to baseline masters, this list celebrates the best the sport has ever seen:

1. Serena Williams: Queen of the court, Serena's 23 Grand Slams, unmatched power, and global impact solidify her GOAT status.

2. Martina Navratilova: With a whopping 59 Grand Slams across all disciplines and a relentless serve-and-volley style, she dominated the 80s.

3. Steffi Graf: This German powerhouse holds the record for most weeks at #1 (377!) and boasts a Golden Slam (winning all majors and the Olympics in a year).

4. Chris Evert: A baseliner legend, Evert won 18 Grand Slams, including a record 7 French Open titles, and had epic rivalries with Navratilova.

5. Monica Seles: A teenage prodigy, Seles won 8 Grand Slams before 20 and could have been even greater if not for a shocking on-court attack.

6. Billie Jean King: On and off the court, King revolutionized tennis. She won 39 Grand Slams and fought for equal prize money and women's tennis rights.

7. Margaret Court: Holding the most Grand Slams ever (24), Court dominated the pre-Open Era with her imposing serve-and-volley style.

8. Venus Williams: A pioneer and Serena's fierce rival, Venus paved the way for generations and holds 7 Grand Slams, with 5 at Wimbledon.

9. Martina Hingis: The youngest Open Era champion at 16, Hingis had a magical touch but injuries cut short her potential.

10. Justine Henin: This Belgian champion won 7 Grand Slams in the early 2000s with a unique one-handed backhand and mental toughness.

These remarkable women have not only shaped tennis history with their on-court brilliance but have also become influential figures both within and beyond the sport. Each one has left an enduring legacy, contributing to women's tennis

#tennislegends#womeninsports#tennisicons#grandslamchampions#goatintennis#trailblazingwomen#tennisroyalty#sportshistory#globalicons#athleteinspiration#gamechangers#tennisgreats#legendaryathletes#womenempowerment#tennisheroes

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forgotten for Football: The Horrific Thanksgiving Day Disaster of 1900

Since the late 1800s Thanksgiving and football have gone hand in hand with the fevered fanbase and anticipation staying strong over the centuries. The first college football game was played on Thanksgiving Day 1876 as part of the Intercollegiate Football Association Championship, and it did not take long for fans to choose their sides. By the time 1900 appeared on calendar pages the University of California Berkeley and Stanford University were already fierce rivals, playing against each other every Thanksgiving since 1892 in a clash that became affectionately known as simply “The Big Game.” People always had high expectations for the game, but no one walking into the event ever expected to encounter tragedy.

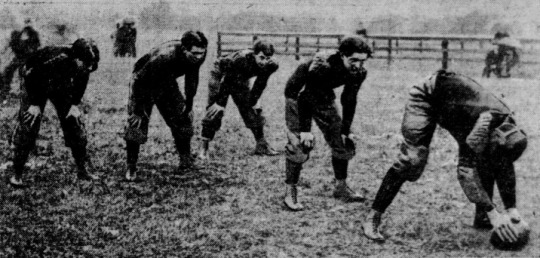

The Stanford University football team circa 1900. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

No one can say the warning signs were not there. In the early days of the game there were no stadiums and it was played in any large field or industrial area that could fit them. The last few Big Game events between University of California Berkeley and Stanford were played at Recreation Field in San Francisco and in 1897 grandstands were built to accommodate the crowds. These seats were not meant to last, they were built quickly to fit 10,000 people with meager roofs that were only put there to keep spectators dry and definitely not to be used for extra seating. But, that is exactly what happened in 1897. While over 15,000 people scrambled and squeezed into the stands to see the game many others looked for alternative means to watch. Contractor J.C. Weir saw the danger and tried to warn those in charge, but his words were ignored while waves of young boys climbed up the stands and crowded the roofs to set their eyes on the teams below. They almost made it through the entire game, but in the final moments the roofs began to buckle, and then they broke. Hundreds of children came crashing down onto those seated below them, intermingled with the wood and metal that was never meant to hold their weight. Some people were knocked unconscious, some were left bleeding but remarkably only one 10-year-old-boy was injured enough to seek medical care and everyone else was, for the most part, left unscathed. One witness to the collapse remarked that the fact that no one was killed or left with permanent injuries was “miraculous”, and indeed it was, but not enough for anyone to learn from it.

The collapse of the grandstands was the last thing on the minds of the attendees of the Big Game taking place on November 29th 1900. The games were always exciting and even though the tradition was fairly new, by 1900 the crowds were massive and the tempers hot despite the teams only having a history of nine Big Game encounters. Of the nine games, Stanford had won seven despite their football team only being founded the same year as their first game and tens of thousands of people couldn’t wait to see if University of California Berkeley would come roaring back. Like previous years, the game was to take place in San Francisco, and once again no one could have anticipated the sheer size of the crowd. It had rained earlier that morning, but when the weather passed the doors of the surrounding neighborhoods and the incoming train cars were swinging open leading to 19,000 people swarming Recreation Field by 10:30am. A ticket for the game cost one dollar, an amount that wasn’t an easy price for many younger fans that desperately wanted to watch the biggest event of their year. So, just as they did several years earlier, the fans got inventive. Some climbed water towers, others tried to dig under fences to get in, but there was one thing that seemed to be an obvious solution for those needing a bird's eye view of the Big Game.

Flyer for the Big Game on November 29th 1900. Image via Stanfordmag.org.

Across from Recreation Field was San Francisco and Pacific Glass Works, a brand new factory that was gearing up to open on December 3rd. Those putting up the makeshift grandstands remembered the collapse of 1897 and they told those in charge of the factory that they were required to do everything possible to prevent anyone from gathering on the roof. The Superintendent of the factory James Davis was in complete agreement with precautions being taken and he was given six tickets to the game for his compliance, but when the time came the workers that were stationed to prevent anyone from getting on the roof were simply overwhelmed. People dug under fences to get to the grounds, flung open the gates, and they poured in. According to one witness, “It was like trying to turn back the waves at the beach. The kids kept pouring through the fence anxious to see the kickoff." Factory workers who could sense the danger went into the streets, looking for police officers to help control the crowd and get the people off the roof but they could not find anyone who could assist. Soon between 500 and 1000 people were crammed onto the factory roof that was only built to withstand forty pounds per square inch. Even if someone wanted to escape it was impossible to move through the crowd to do so. They all gazed ahead, not paying any attention to the tell-tale signs around them signaling the danger they were all in.

Twenty minutes into the game the crowds in the stands were electric. Their voices were roaring and the bands for Stanford and University of California Berkeley were booming, beating the thousands into a frenzy. The atmosphere on top of the glass works building was just as ecstatic, but in a matter of seconds it shifted to chaos. A portion of the roof of the building gave way and in a scene that was unfortunately familiar the fans began to fall. But, unlike the collapse of 1897 that had relatively minor injuries, this time the spectators fell into an absolute nightmare.

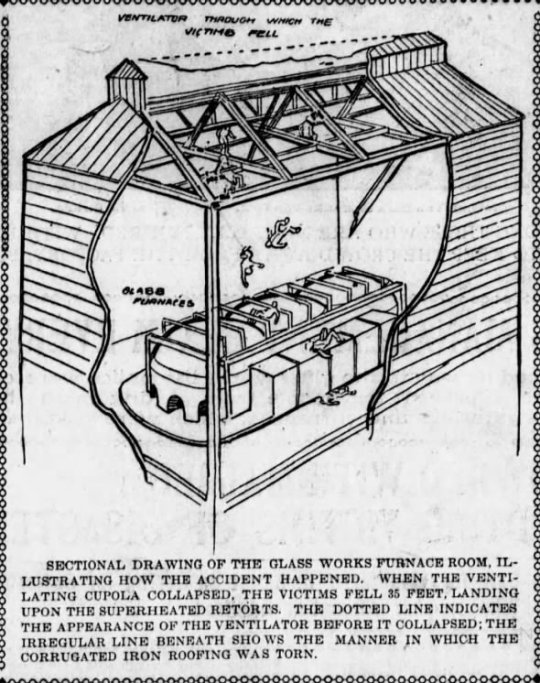

This building was a glass factory, and although it was not due to officially begin production just yet, it was partially operational in preparation for the opening day. One thing that was up and functional was a furnace, filled with fires strong enough to melt glass and with an exterior temperature of approximately 500 degrees. Working in the factory that day were Ignace Jocz and Clarence Jeter, and they could undoubtedly hear the roars of the crowd before humanity started to unexpectedly rain down on them from above. The hole in the roof opened at the worst possible spot and between sixty and one hundred people fell forty-five feet into the factory with some of them landing directly on top of the glowing furnace.

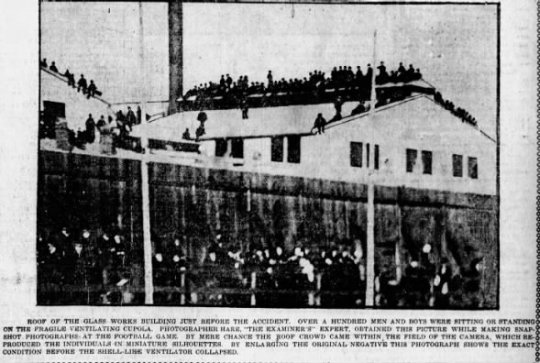

Image of the roof of the factory just before the accident. Image via 30 Nov 1900, Fri The San Francisco Examiner Newspapers.com

It's impossible to imagine the scene and the sounds that filled the factory as they all hit the metal or, if they were lucky, the brick floor. Once they hit most broke enough bones to render them immobile and those that hit the furnace stuck to the sizzling top. To make things even worse the furnace was encased by binding rods surrounding the machine in what was essentially a cage, trapping anyone who fell in the spaces. Those who missed the cage were just as unlucky, some of the falling bodies struck fuel pipes on their way down, severing them and sending boiling oil through the air and dousing the already burning bodies that then exploded into flame. Adding to this already unimaginable tragedy was the fact that almost everyone who plummeted through the ceiling that day were children, some boys as young as nine years old, that were the most likely to not have the dollar to buy a ticket and the least amount of concern about climbing to the roof of a building to watch the game.

Illustration of the inside of the factory showing the furnace and binding rods. Image via 30 Nov 1900, Fri The San Francisco Examiner Newspapers.com.

Jocz, Clarence, and some other employees of the factory jumped into action doing what little could be done to attempt to save some of the victims, grabbing bodies and throwing them out of the way and using long metal hooks that were normally used to stir molten glass to hook people that landed on the furnace and drag them down. Watching the horrific scene from above were approximately twenty-seven people who also fell through the ceiling but somehow were able to cling to the rafters and the walls to avoid being roasted alive. One witness, young Thomas Curran, survived the ordeal by grasping a ceiling joist with his legs, forced to hang upside-down while chaos erupted under him. He later stated: “As I clung there, I saw the poor fellow who had been chatting with me strike the furnace. He curled up like a worm in that heat.” The sound of the bands and cheers of the game could still be heard filling the air.

Incredibly, the crowds gathered to watch the Big Game were greatly unaware of the tragedy unfolding nearby. Spectators heard the crash but some believed it was simply a planned distraction by the opposing team, with one fan yelling “It’s a job!” Others believed it was just normal sounds coming from the industrial park and within moments the focus was back on the field. Those who did know that something was amiss were the residents of the surrounding towns and they quickly began to swarm the factory, screaming the names of their sons who had gone off that morning to enjoy a football game. The masses also ran to the morgue and toward the wagons being driven by the coroner, some filled with bodies burned and disfigured beyond recognition and others filled only with what remained such as socks, shoes, neck ties, and the contents of small pockets. Every possible vehicle was summoned to help, and a frantic search began for doctors that could be pulled away from their Thanksgiving meals to help the deeply wounded masses that lay on the factory floor in sheer agony while the smell of burning flesh filled the air. As the players from Stanford were marched out onto the street for an impromptu victory parade to the nearby Palace Hotel, other streets were filled with the screams and frenzy of the tragedy that seemed to have happened in another world from the game that happened only two blocks away.

As the news spread that day as to what happened and the numbers began to rise the city was plunged into a deep state of sorrow. Hospitals became overwhelmed and the official count declared that thirteen people had died in the factory with eighty-six others critically wounded. As more recovered, others still died and soon the funerals began. On the following Sunday alone there were nine burials that had to take place back-to-back from 9am to 4pm.

Newspaper story about the accident. Image via 30 Nov 1900, Fri The San Francisco Examiner Newspapers.com.

Amazingly, reactions to what happened remained as separated in the newspaper pages as they did on the streets the day of the tragedy. The cover of the New York Times talked about the horror of the deaths at the glass factory, but the Sports section beamed of the Stanford victory as if nothing else had happened that day, calling the game the “closest and most exciting game of football ever played by the elevens of the two California universities." No players or coaches commented on the unspeakable horror that unfolded within earshot of the game that day. The college publications from both Stanford and University of California Berkeley carried on as if it never even happened with the Stanford Daily writing a 1,500-word front-page story about the victory with no mention of the tragedy other than a casual mention of a potential rematch to raise money for the affected families that never ended up happening.

Although the city of San Francisco felt the deaths deeply, it seemed they too wanted to move beyond it as quickly as possible. When a grand jury was assembled to determine who was at fault for the Big Game disaster it had an air about it that seemed like it was purely for appearances. The blame was placed on James Davis as the Superintendent of the San Francisco and Pacific Glass Works and then it shifted to the police for not assigning enough people to the game. Shockingly, with no one to blame and people wanting to simply move on, the blame shifted to the dead. Seven days after the tragedy, and with victims still succumbing to injuries, the jury declared that “[T]he deceased had no business being there...No one can be held responsible for their deaths other than themselves." No one fought them on this. In the minds of most, the story of the collapse was over.

The newspapers and courts might have decided the case was closed, but for many what happened that day never went away. On December 4th 1900 young Fred Lilly died in the City and County Hospital after suffering for months from a fractured skull he sustained in the fall. He never fully regained steady consciousness but in moments of delirium he still acted as if he was watching and enjoying the football game that was playing in front of him before everything suddenly stopped. Three years after the roof collapse twenty-eight-year-old Thomas Pedler passed away after enduring spinal surgery, paralysis, and the amputation of both legs. His demise marked the twenty-third and last death resulting from the disaster, fifteen of which being children that died before their eighteenth birthday.

To this day the tragedy, known now as the Thanksgiving Day Disaster or The Big Game, is the deadliest accident to ever happen during an American sporting event. Now the glassworks building is gone, replaced with a building belonging to the University of California. The gravestones are also gone and most of the final resting places of victims disappeared from memory and fell into ruin after San Francisco introduced regulations forbidding new burials, also in the year 1900. One small reminder of the incredible catastrophe can be found in the Holy Cross Catholic Cemetery just south of the city. Here lies a tiny stone cross that was meant to only be a temporary marker. It is inscribed with the name Cornelius McMahon, a twelve-year-old boy who died in the Thanksgiving Day Disaster and now remains as the only physical reminder of the deadliest day in American sports history.

*****************************************************

Sources:

“The Big Game Disaster of 1900” by Sam Scott. Stanford Magazine November/December 2015.

“Big Game was marred by tragedy in 1900 contest” by Edvins Beitiks. November 17, 1997.

“The Thanksgiving Disaster that Most People Haven’t Heard About” by Marina Manoukian. November 19, 2022.

“Sudden Death: Boys Fell to Their Doom in S.F.'s Forgotten Disaster” by SR Weekly Staff. Aug 15, 2012.

“Thanksgiving Day Tragedy” ThePigskinDispatch.com

https://pigskindispatch.com/home/Football-Fun-Facts/Random-Football-Facts/Stadium-Disasters/Stanford-Vs-Cal-1900-Tragedy

#HushedUpHistory#featuredarticles#history#CaliforniaHistory#SportsHistory#tragichistory#horriblehistory#Footballhistory#TheBigGame#ThanksgivingDayDisaster#historyclass#strangehistory#forgottenhistory#tragictale#truestory

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

When you ask me how Sawai sensei explained how to fight using Taikiken, it comes close to the charging style of Mike Tyson with a quick knockout! "It's the feeling at work, learn by watching." ;-) Mike Tyson: All Knockouts of the Legendary Boxer Mike Tyson’s name resonates throughout the world of boxing like thunder during a storm. Born in Brooklyn, New York, Tyson burst onto the professional boxing scene in the mid-1980s, captivating the sports world with his ferocious style and unimaginable power. His meteoric rise from a troubled youth to the youngest heavyweight champion in history stands as one of the most inspiring and electrifying stories in professional sports. Yet it’s Tyson’s knockouts—sudden, staggering, and definitive—that truly define his legend. The Early Years and Rapid Ascent Under the guidance of the renowned trainer Cus D’Amato, Tyson developed a style that combined rare speed, uncanny timing, and relentless aggression. Starting his career with an awe-inspiring streak of victories, Tyson chalked up knockout after knockout, often within the first round. These early fights showed the sports world that Mike Tyson was not just another prospect—he was a phenomenon. Fans were drawn to the savage intensity he brought to the ring, crashing through opponents with razor-sharp combinations. Capturing the Heavyweight Title In 1986, at the age of 20, Tyson knocked out Trevor Berbick to become the youngest heavyweight champion in boxing history, solidifying his status as “Iron Mike.” The swiftness and power of his punches were the kind few boxers could muster, and the finishing blows usually left his challengers on the canvas, struggling to beat the count. Every knockout showcased his unique ability to close distance rapidly and throw short hooks and uppercuts with unstoppable force. The Signature Technique Tyson’s knockout repertoire was driven by his iconic peek-a-boo stance—hands high, head in constant movement, always looking for an opening to explode. His right hook to the body followed by a right uppercut to the chin was a classic combination that ended more than a few matches. Opponents found themselves overwhelmed, as there was simply no room to breathe in front of Tyson’s perpetual offense. Memorable Knockouts and Rivalries From his demolition of Michael Spinks in just 91 seconds to his rematch knockout over Frank Bruno, Tyson delivered adrenaline-filled moments that still thrill boxing enthusiasts. Even after facing setbacks—like the loss to Buster Douglas in Tokyo and eventual imprisonment—Tyson’s comeback fights were punctuated by formidable knockout power. His raw charisma and unpredictable persona added another layer of excitement to his career, making every bout a must-watch event. Legacy of a Knockout Artist Mike Tyson’s legacy extends beyond his record. He inspired a generation of fighters to combine skill with an intimidating presence. Watching his knockout highlights is like witnessing a whirlwind of skill, strength, and drive. Tyson’s impact on boxing remains undeniable—he paved the way for a new era of heavyweights who understood the value of speed, agility, and explosiveness. In reflecting on Tyson’s knockouts, one cannot help but admire how the sport of boxing is an intersection of discipline, strategy, and primal force. While Tyson’s career had its share of controversies, the sheer brilliance and energy he brought to the ring continues to captivate fans, young and old. Even now, when we look back on his knockouts, we see pure boxing artistry—the kind that made Mike Tyson a phenomenon recognized around the globe.

#MikeTyson#Knockouts#BoxingLegend#IronMike#HeavyweightChampion#BoxingHighlights#KOCompilation#CusD’Amato#PeekabooStyle#PowerPunching#LegendaryFights#BoxingHistory#GreatestBoxers#TysonKnockouts#AllKnockouts#BoxingIcons#SportsHistory#BoxingFans#IronMikeTyson#BoxingLegacy#Youtube

0 notes

Text

History Made! Indian Women Crowned First-Ever Kho-Kho World Cup Champions

Introduction

In a historic moment for Indian sports, the women's Kho-Kho team has etched its name in the annals of sporting history by clinching the first-ever Kho-Kho World Cup championship. The tournament, held in Delhi in 2025, saw the Indian team showcase unparalleled skill and determination, ultimately defeating Nepal in a thrilling final with a score of 78-40. This remarkable achievement not only brings glory to the nation but also marks a significant milestone in the journey of traditional Indian sports on the global stage.

The Road to Glory

The Indian women's Kho-Kho team's path to victory was nothing short of spectacular. Let's take a closer look at their journey through the tournament:

Group Stage

The team started strong, sweeping victories against formidable opponents:

Defeated Iran

Overcame South Korea

Triumphed over Malaysia

These initial wins set the tone for their dominant performance throughout the tournament.

Quarter-Final

In a crucial match, the Indian team faced Bangladesh. Despite the pressure, they maintained their composure and secured a decisive victory, propelling them into the semi-finals.

Semi-Final

The semi-final match against South Africa was a true test of skill and strategy. The Indian team rose to the occasion, dominating the game and securing their place in the final.

Final

The pinnacle of the tournament saw India facing Nepal in a high-stakes match. With unwavering focus and exceptional teamwork, the Indian women's team clinched a spectacular win with a score of 78-40, crowning them as the first-ever Kho-Kho World Cup champions.

Unbeaten Champions

One of the most remarkable aspects of India's victory was their undefeated streak throughout the tournament. The team demonstrated exceptional skill, strategy, and teamwork in every match they played. Their dominance was further highlighted by the massive margin difference of 551 points, setting a new standard for excellence in the sport.

This unbeaten run is a testament to the rigorous training, dedication, and mental fortitude of the Indian women's Kho-Kho team. It also speaks volumes about the coaching staff and support system that helped prepare the team for this global competition.

A Proud Moment for India

The victory of the Indian women's Kho-Kho team is more than just a sporting achievement; it's a moment of national pride. This historic win reflects India's rich sporting heritage and showcases the country's potential in traditional sports on the international stage.

Dr. Nowhera Shaik, MD & CEO of Heera Group of Companies, expressed her pride in the team's accomplishment, stating, "This victory is a proud moment for India, showcasing our talent and the importance of preserving and promoting our traditional sports on the global stage." Her words echo the sentiments of millions of Indians who are celebrating this momentous achievement.

Impact on Traditional Indian Sports

The Kho-Kho World Cup victory has far-reaching implications for traditional Indian sports:

Global Recognition: This win brings international attention to Kho-Kho, a sport deeply rooted in Indian culture.

Increased Popularity: The success of the Indian team is likely to spark increased interest in Kho-Kho among young athletes.

Investment in Infrastructure: The victory may lead to more investment in Kho-Kho facilities and training programs across the country.

Inspiration for Other Traditional Sports: This achievement could pave the way for other traditional Indian sports to gain recognition on the global stage.

Cultural Pride: The win reinforces the value of preserving and promoting India's rich sporting heritage.

Reactions and Celebrations

The victory of the Indian women's Kho-Kho team has sparked celebrations across the nation. Here are some notable reactions:

Sports Minister's Statement: The Indian Sports Minister hailed the victory as a "new dawn for traditional Indian sports" and promised increased support for Kho-Kho and similar games.

Social Media Frenzy: #KhoKhoWorldChampions trended on various social media platforms, with fans and celebrities alike sharing their congratulations.

Welcome Ceremony: Plans are underway for a grand welcome ceremony for the team upon their return to India.

Team Captain's Remarks: The captain of the Indian team expressed her joy, saying, "This win is for every girl who dreams of making it big in sports. We hope to inspire the next generation of Kho-Kho players."

The Future of Kho-Kho

The World Cup victory opens up exciting possibilities for the future of Kho-Kho:

International Tournaments: There's potential for more international Kho-Kho tournaments to be organized regularly.

Inclusion in Multi-Sport Events: This win could lead to Kho-Kho being considered for inclusion in major multi-sport events like the Asian Games.

Professional Leagues: The increased popularity might pave the way for professional Kho-Kho leagues, similar to those in cricket or kabaddi.

Grassroots Development: Expect to see more focus on developing Kho-Kho at the grassroots level, with schools and colleges promoting the sport.

Research and Innovation: As the sport gains traction, there might be increased research into training methods and equipment specific to Kho-Kho.

Conclusion

The Indian women's Kho-Kho team's victory in the first-ever Kho-Kho World Cup is a landmark achievement that will be remembered for years to come. It not only brings glory to the nation but also shines a spotlight on the potential of traditional Indian sports in the global arena.

This historic win serves as an inspiration for aspiring athletes across the country, proving that with dedication, skill, and the right support, Indian sports can reach new heights on the world stage. As we celebrate this momentous occasion, we look forward to a bright future for Kho-Kho and other traditional Indian sports.

#khokho#khokhoworldcup#nowherashaik#heeragroup#indiawins#womeninsports#indiansports#traditionalsports#worldchampions#teamindiatriumph#khokhochampions#sportsvictory#indianathletes#womenempowerment#sportshistory#globalkhokho#indianpride#khokhoskills#sportscelebration#indiaontherise#traditionalflair#sportingglory

0 notes

Text

Muggsy Bogues was DIFFERENT. Happy 60th birthday to a game-changer!

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roberto Clemente. Art Print. https://jschulerart.etsy.com/listing/1803119721

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Every game begins with an invitation to dream, and every play writes its story." "The magic of play is that it transforms the ordinary into the extraordinary—one move at a time." "Winning is fleeting, but the laughter and bonds formed in play last forever." "The rules of the game may guide us, but the freedom of play defines us." "In every game, there’s a moment where fun overtakes fear—that’s the sweet spot of play." "Play isn’t just a break from life; it’s a bridge to something bigger." "Games remind us that competition can coexist with connection." "In the playground of life, the real win is measured in smiles, not scores." "Play is the art of turning chaos into creativity." "No matter how old we grow, the joy of play keeps us forever young."

#sports#sportsblog#sportshistory#introductiontosports#athletics#historyofsports#sportsculture#discoversports#sportsfans#playtogether

0 notes

Photo

Did you know? 🏉⚽ Rugby and association football (soccer) became two separate sports in 1863 with the creation of the Football Association in England. A historic split in sports! 🏆

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Tiger Woods Through AI: A Visual Tribute to His Golf Legacy | Born December 30

🏌️ Tiger Woods: The Golf Legend Who Redefined the Game 🏆

Dive into the life and career of Tiger Woods, one of the greatest golfers in history! Born on December 30, 1975, Tiger Woods has won 15 major championships and inspired millions around the globe. From his early days as a prodigy to his record-breaking victories and incredible comeback stories, this video takes you through every milestone of his legendary journey.

🌟 This video features stunning AI-created images to bring Tiger Woods' incredible story to life, offering a unique perspective on his impact both on and off the course.

💬 Engage with us! Comment below: What’s your favorite Tiger Woods moment?

Subscribe to @Born_on_this_day for more amazing stories about iconic personalities!

0 notes

Text

🏸 The Fascinating Journey of Badminton 🏸

Did you know that badminton has a history spanning over 2,000 years? This fast-paced and thrilling sport has its roots in ancient civilizations, where people enjoyed early versions of the game.

🌏 Origins of Badminton

The earliest form of badminton was "Battledore and Shuttlecock," played in ancient Greece, China, and India.

In the 18th century, a game called "Poona" became popular in India. British officers stationed there loved it and brought it to England.

🏰 How Badminton Got Its Name In 1873, the Duke of Beaufort hosted a game at his estate, Badminton House in Gloucestershire, England. This historic moment gave the sport its name! By 1877, the first official rules were written, laying the foundation for the modern game.

🌍 Badminton Goes Global The sport’s popularity exploded, leading to the formation of the International Badminton Federation (IBF) in 1934, now known as the Badminton World Federation (BWF). Badminton made its Olympic debut in 1992 in Barcelona, becoming a global favorite. Today, it’s dominated by powerhouse nations like China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Denmark, and India.

🏆 Major Tournaments

All England Championships – One of the oldest and most prestigious badminton tournaments.

Thomas Cup – Men’s Team World Championship.

Uber Cup – Women’s Team World Championship.

World Championships – The pinnacle of individual success.

🔥 Why We Love Badminton Badminton isn’t just a game; it’s a test of speed, skill, and strategy! Whether you’re playing professionally or just for fun, it’s a sport that connects people across the world.

0 notes