Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Kitchen culture makes organizing an uphill — but necessary — battle for restaurant workers.

I was extremely heartened to hear that the Chicago restaurant Lula Cafe is closing today in support of its workers who are participating in the general strike for International Women’s Day. As a male line cook in a small from-scratch restaurant, I think of the ridicule, stigma, and resistance I would face from owners and fellow workers alike if I were to strike today (I happened to have the day off anyway), and I can only imagine how much worse it would be if I were a waitress or female line cook.

Part of what makes this industry so unique and compelling is its deep and long-established culture of discipline, camaraderie, and passionate enthusiasm. All too often, however, that culture becomes a tool used by owners and management for the exploitation of their workers. Never mind voluntarily striking — even calling out sick in a restaurant is widely considered a personal failure, as a way of letting one’s team down, when in reality it is a failure on the part of management to adequately staff the restaurant taking into account the obvious fact that human beings sometimes fall ill. Suggesting that such understaffing is unavoidable, owners constantly remind us of the tight profit margins inherent to the restaurant industry — it’s a “labor of love” — and alternately cozy up to us by making small talk about their vintage car collections.

On the other hand, owning a restaurant should be an extremely easy task for a capitalist because restaurant workers — at least serious cooks — tend to self-discipline (I think of an anecdote about a line cook who cauterized his own wound on a frying pan to keep cooking a busy service). We regard the success of the restaurant as a measure of our own artistic worth. We take masochistic pride in being overworked and understaffed: working 60–80 hour weeks leaves little time to develop class consciousness, unionize, or organize solidarity with other social movements. For this reason cooks often remain apolitical, or rather de-politicized, and frustratingly tolerant of casual racism, sexism, and homophobia in the workplace. Any resentment we might feel against the owners who extract the value of our labor is mediated by our intense loyalty to our chefs and teammates. When we sacrifice our physical and mental health, our personal relationships, our holidays, weekends, and leisure time, we think of it as a tribute to them and not as a direct deposit into the owners’ bank accounts.

Gestures like Lula Cafe’s closure today, the (moderate at best) discussions of a better kitchen culture among celebrity chefs like Rene Redzepi, and the strength of the Fight for 15 and fast food workers’ unions are important steps toward establishing social and political struggle in the restaurant. But the restaurant itself will have to undergo radical structural change if it is ever to become a livable, inclusive, and just institution for the workers who produce its value. Not only fast food workers, but chefs, line cooks, bartenders, and waitstaff must organize and form unions together. Too often the (typically gendered) division between front and back of house is an obstacle to restaurant worker solidarity which benefits only the owners. Harassment, sexism, racism, homophobia, and transphobia must be rooted out not as a matter of finger-wagging political correctness but as a matter of resisting the ongoing and historical structural violence waged by elites against marginalized groups. We should always do our best to support and establish restaurants and kitchens that are collectively worker-owned and democratically governed, where the wealth produced by our labor is distributed fairly among the workers and not squandered by owners whose only qualification is providing the capital to open the business (which simply means they happened to be rich or to schmooze with someone rich at some point).

The culture of the kitchen is deeply entrenched and, with its reverence for discipline, hierarchy, and tradition, in some ways very conservative. The struggle for socialism in the restaurant will not be an easy one by any means, but until we give it a shot our passion, artistry, livelihood and health are extracted and wasted on some car parked in the owner’s hobby shop garage.

0 notes

Text

acnl

Before the veil of this world on the train I gave it its name - Hell. There I spoke to Rover, who is Janus who shaped my face with which I greeted upon arriving the folk there.

They made me forthwith mayor.

The tent to which I was indentured —Nook (industrious monopolist, of whose nepotism the old shop stank) would not leave his debtors to the elements— frayed and permitted insects.

Luckily here wild Peaches weigh down the boughs I have shaken every trunk in Hell for fruit Which I offer to bottomless Reese who produces Bells

My down payment to Nook who has been patient a serpent

then next door to the only store where his nephews sell me the only net at the only price

it is suitable for the roaches which Reese the liquidator swallows

though one of each kind I offer to Blathers who holds them in time his sleepless obsession already mine.

0 notes

Text

why vine died

Each social media platform encourages slightly different behaviors. We might be more reserved on networks like Facebook where posts may be visible to extended family and employers, and bolder on networks like Twitter which tend to be used mostly by smaller peer groups. These tendencies accumulate to give each platform its own distinct feeling, but for the most part these distinctions are superficial. Every major social media platform works the same way: each delivers a feed of heterogeneous content. Largely in chronological order, but with some algorithmic intervention, we receive a potpourri of news, jokes, art, advertisements, and personal updates from friends, family and acquaintances.

Reading the feed requires a kind of dispersed attention—an openness to the shift from a colleague’s vacation photos to a news article reporting hundreds of deaths to a Kermit meme. Shifting our attention rapidly between vastly different types of content conveniently makes us more open to viewing advertisements, and correspondingly ads are adapting to resemble other kinds of content. We not only have trouble distinguishing ads from the content we voluntarily subscribe to, we also voluntarily subscribe to view ads. The feed demands a porous readership in the sense that the reader readily absorbs whatever they are immersed in.

Vine could never be successfully monetized because, unlike other platforms, it was never able to build a sufficiently porous (and thus vulnerable to advertisement) audience. The six-second looping video was a perfect format for a quick setup and punchline. Because the format was so perfectly suited to jokes, the Vine feed only ever delivered this one type of content. And since Vine users knew exactly what to expect, it was much more difficult to slip in ads undetected. In this sense we were always much less distracted when binge-watching six second videos on Vine than we are reading headlines on Facebook.

(In McKenzie Wark’s framework, we can say that Vine died because it was not useful too the vectoralist class.)

The death of Vine made explicit what we already knew—that somewhere along the line there was a paradigm shift where we stopped thinking of actions like reading the news, shopping, reading and writing correspondence, and appreciating art as distinct activities, and instead collapsed them into the one monolithic activity of “looking at my phone,” and that shift is critical for generating ad revenue. We tend to speak as if it is the sheer volume of information and our struggle to keep up with it that overwhelms us, but perhaps the more crucial point is our relinquishing control over the organization of that information.

Before the feed was the blogroll - a list of bookmarked publications that the reader would check individually and manually for new content. The feed purported to eliminate this supposedly tedious task by becoming the one-stop-shop for all the reader’s content consumption. But at the same time that we consolidated our consumption to the feed, we also became much less methodical in our reading habits. Before the feed, if I wanted to find new music I would check a few of my preferred music blogs. If I wanted to read the news I would check the websites of two or three newspapers. Though this method seems archaic now, it never produced the same kind of regret that I feel when I open Twitter with the intention of catching up on politics, only to realize an hour later that I’ve mostly been thumbing through memes.

If social media feeds numb and scatter our attention, restoring intentionality to our reading habits might go a long way toward mitigating the damage.

0 notes

Text

gamification

Gamification is not about making work into play but about making everything (including play) into finance or consumption. Scores are not essential to games but they are essential to finance. Step counts (fitbit), likes (facebook), and high scores are all meant to feel like a credit score or a bank statement and not the other way around. The more our experiences can be quantified the more concretely they belong to us. Under finance, wealth and correspondingly everything else becomes quantitative rather than qualitative. Therefore what is tangible is not what can be touched but what can be counted. If it’s not on the ledger, it didn’t happen.

1 note

·

View note

Text

[Porousness] in 7CV [Part 2 of ?] Intertextuality

7CV is not only diffuse or permeable or porous in the sense that its boundaries [membrane] are non-static, but also in that they allow for intertextual diffusion. 7CV is permeated throughout by other texts via appropriation, allusion, citation, and photocopy. Here, intertextuality surpasses or evades its usual purposes. As with the overabundance of formats and editions, hyperbolic intertextuality destabilizes assumptions about the static nature of the book. Lin says:

My interest with HEATH and 7CV was to treat the book as a distinct medial platform through which a lot of ancillary information passes, much like a broadcast medium like TV or a narrow-cast medium like Twitter or Tumblr.

(Interview with Angela Genusa for Rhizome, Oct. 2012)

Like a TV broadcast or a social media feed, 7CV aggregates a wide variety of information from many sources and authors. This creates a reading experience which is hypertextual and discursive in a way that feels similar to channel surfing or browsing the web.

In one illustrative instance, a passage of dense critical prose analyzing the architecture of Walmart is interrupted with the non-sequitur, “#pilsner is my favourite kind of #beer” (128), set apart not only by its diction and subject matter but also by capitalization scheme and typeface as if it were copy-and-pasted from another source. The hashtags, of course, allude to Twitter, and indeed by causing the reader’s attention to flit momentarily to something completely unrelated, this passage mimics the experience of reading an article on a phone or computer and receiving a notification from Twitter in the corner of the screen. Throughout the book images (mostly photographs and scanned images of book backs and packaging) appear beside text to which they bear no (or indecipherable) relevance, interrupting attention much like popups or other advertisements. To read Lin’s ambient review of Wylie Dufresne’s modernist restaurant WD-50 on page 88 and then happen upon the scanned image of a toothpick package from that restaurant on page 101 feels like stumbling on Google Ads for a product you’ve been recently Googling.

Allusions and citations permeate the book like hyperlinks on the internet. Citations like “1935 ‘The present situation in quantum mechanics’ in Naturwissenschaften, 23, pp. 823-828” (103) and allusions like “The book is James Beard’s Theory and Practice of Good Cooking. The only other book I kept in that apartment at the time was a copy of Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror by John Ashbery” (112) refer the reader directly to other texts outside of the book. Or consider the literal hyperlinks in the PDF 7CV Critical Reader, of which there are more than 100. 7CV even makes use of internal links—the note “(continued on page 222)” (123) physically sends the reader to another location in the book, like a hyperlink which sends the reader to another area of the same website. Of course, such hypertextual connections are present in any text with endnotes, citations, or allusions, and that is precisely the point. 7CV exaggerates and proliferates hypertextual connections in order to emphasize how hypertext always informs reading experiences, even in non-digital formats. A book, as much as a website, is a networked object.

#tan lin#7cv#seven controlled vocabularies and obituary 2004#the joy of cooking#rhizome#john ashbery#james beard#quantum mechanics#hyperlink#hypertext fiction#hypertext criticism#thesis#network culture#intertextuality#beer#pilsner

0 notes

Text

IRL [glossary entry]

IRL (acronym: ‘in real life’) is an oppositionally-defined [intuitive] term referring to the version of something that is not digital or online. Use of the term is intriguing because it points to a fallacious, yet commonly-shared sense of dimensional divide; although the electrical signals which comprise our digital lives take place on physical circuitry, and are thus very much a part of ‘real life,’ we almost unilaterally discuss what happens online as if it were a world apart from what happens IRL.

(IRL’s endearing synonym ‘meatspace’ further emphasizes this fallacy by implying that the division between the digital and IRL is somehow spatial.)

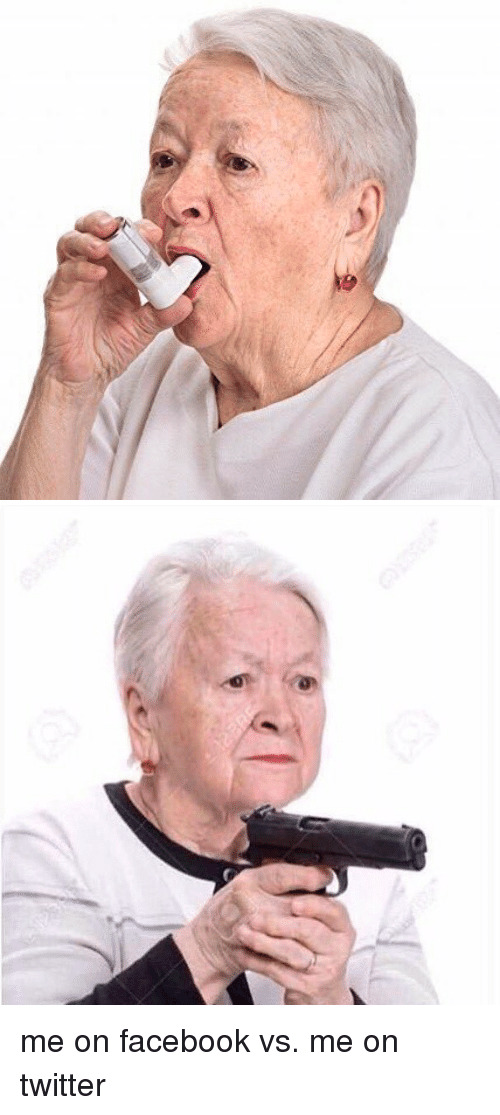

Because the term IRL is only necessary in distinguishing something from its digital counterpart, its use always invokes an existential doubleness. For instance, describing one’s behavior IRL as opposed to on social media assumes that one’s social media presence acts as a surrogate or doppelganger in a secondary plane of existence.

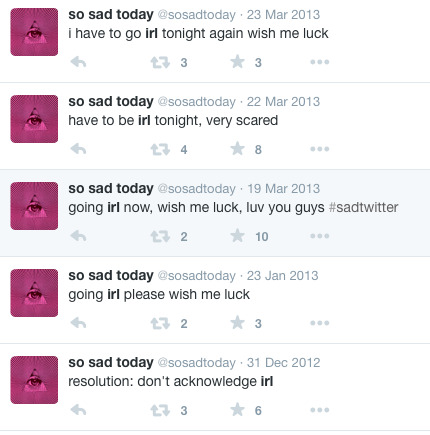

Poet Melissa Broder’s pseudonymous Twitter project @sosadtoday often subversively comments on this second life fallacy and its use as a form of escapism.

Broder’s speaker frequently describes an obligation to “go irl,” implying that her digital life has become primary, and that spending time IRL is a deviation from her habits. In other words, her escapism has progressed so far that her IRL existence has become the surrogate for her existence online.

The second life fallacy presents a convenient avenue for escapism because of the distance between digital life and the human body IRL. For Broder’s speaker, “going irl” represents the entangled precariousness of being an embodied woman in capitalist heteropatriarchy.

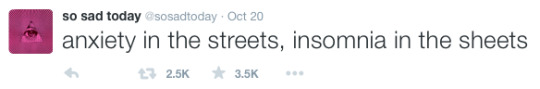

The tweet “anxiety in the streets, insomnia in the sheets” describes the intersection of embodiment and anxiety. “Anxiety in the streets” refers to social interaction IRL by invoking the physical, public space of “the streets.” Since the speaker identifies as a woman, the phrase “in the streets” also recalls the highly prevalent danger of street harassment. Unlike her social media presence, the speaker’s body experiences unmediated social interactions. Whereas social interactions online are mediated by pseudonyms (which may be blocked), text (which can be drafted, revised, deleted), and browser windows (which may be closed), social interactions IRL necessarily involve the body (which can twitch, stutter, become the object of gaze or of physical harm). “Insomnia in the sheets” highlights the IRL body’s physical needs, which become easy to neglect while bingeing on social media.

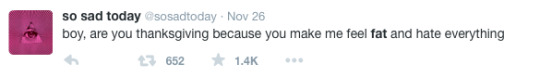

Ironically parsed in the form of a pickup line, the tweet “boy, are you thanksgiving because you make me feel fat and hate everything” posits the speaker’s embodied female subjectivity as the object of heterosexual male gaze and its capitalist, post-colonial American (”thanksgiving”) beauty standards. The conclusion, “and hate everything,” indicates that the speaker’s generalized depression and anxiety stems from these intersectional systems of oppression.

In order to escape the manifold systems of oppression to which she, as a woman with a body, is subject to, @sosadtoday attempts to renounce IRL altogether by existing primarily online. Of course, this escapism is tragic because it is ultimately insufficient. Not only is misogyny just as prevalent and dangerous online as it is IRL, but digital intimacy, though perhaps safer (or less anxiety-inducing), is just not satisfying.

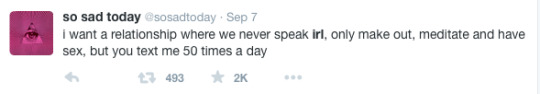

The speaker’s desire to conduct verbal communication with a lover through text messages points to the irony of her escapism: verbal communication is too fraught to conduct IRL, but physical desire can not be satisfied digitally. The futility of the second life fallacy is that digital life ultimately can not stand in for life IRL. Broder deftly highlights this futility by having her speaker figuratively apply the functions of IRL to digital life:

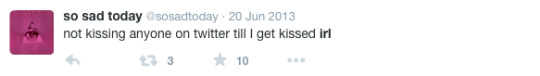

...or vice versa:

Just as one’s online presence can not be kissed, Broder implies, one can not fulfill their IRL desire for love and attention with favs, followers, and retweets. Suddenly “existential doubleness” falls away. One’s online presence is not a surrogate self experiencing a fully-fledged alternate reality; it is merely the sum of data one has written onto the cloud. We are always IRL, whether we are holding an iPhone or someone’s hand.

#@sosadtoday#melissa broder#irl#meatspace#social media poetry#glossary#second life#hikikomori#social anxiety#john oliver#male gaze#body image#poetry#criticism#close reading

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Footnote to [Porousness] in 7CV... [Part 1 of ?]

Can we consider the interviews Lin gave regarding 7CV as parts of 7CV? They do, after all, read a lot like the text of the book itself:

So SCV is a cross-pollinated ecosystem, an agrarian system with a very beautiful table of contents and pen and ink drawings of foods and the hands that make those foods. [...] Like all books, it is beautiful only in regard the decompressions it has been put to. [...] There is no real distinction between what I am writing now and what I will be writing next.

(Interview with Kathleen Elaine Sanders for BOMB).

In the same interview, Lin conflates reading interviews about a book with reading the book itself, saying, “A lot of the book has already been read long before we got to it. Context is more important than content.”

Further, the second abridged edition of Lin’s later project Heath includes the full text of an interview he gave following the publication of the first edition, thus conflating context and content.

Back to [Porousness] [Part 1].

0 notes

Text

[Porousness] in Tan Lin’s Seven Controlled Vocabularies and Obituary 2004: The Joy of Cooking [Part 1 of ?]

[note: Page numbers refer to the Wesleyan University Press edition (2010) unless I note otherwise. Generally subtract 4 from the page number to find the same content in the Lulu First Edition (2007).]

My principal aim in the past fifteen years has been to produce an “ambient" literature; really a mode of literature rather than a recognizable genre that would be permeable and could disable the rigid categorization of work into such categories as poetry, fiction, and literary criticism/poetics.

(Tan Lin, artist statement for the Foundation for Contemporary Arts, Dec. 2011. Emphasis mine.)

Seven Controlled Vocabularies and Obituary 2004: The Joy of Cooking may be thought of as permeable, porous, or diffuse in that its boundaries [synonym: membrane] are not static. 7CV is not so much a single book, but a sprawling conglomeration of documents, [videos, events, information, media]. At the center of this conglomeration is a 222 page-long text titled Seven Controlled Vocabularies and Obituary 2004, The Joy of Cooking, originally self-published in 2007 on Lulu.com, and subsequently updated and published in 2010 by Wesleyan University Press. According to a list included in this core text, the same book is available in 10 other “formats,” ranging from a hardcover edition to a “literary placemat” made from “thermal-lined plastic” to a $12,000 “plexiglass video installation” (168). The first Lulu edition also lists one of the formats as “THE AUTHOR AT [email protected]” (1st ed., 162). In addition, in 2010 Edit Publications released eleven more book-length, collaboratively-authored documents which expand 7CV, including four editions of Chinese translations of the original book, an Appendix, and a “Critical Reader” which refers the reader to downloads of more than a hundred full-length critical texts from other writers. These auxiliary [documents]—I mean the “other formats” as well as the expansion documents—serve to undermine the boundaries of 7CV. If the title 7CV refers not only to a first and second edition, but also to home goods, installations, and an email address, then where exactly does 7CV end?

In the title Seven Controlled Vocabularies and Obituary 2004: The Joy of Cooking, Lin alludes to the corrupt fifth edition of The Joy of Cooking as an earlier text whose complex publishing history also problematizes the assumption of stable boundaries. In an Interview with Katherine Elaine Sanders for BOMB, Lin refers to the corrupt fifth edition of the cookbook as “a porous and experimental text.” The Joy of Cooking is an expansive, multi-authored book with many editions, and the corrupt fifth edition spotlights these qualities. Published in 1962 without the author’s edits, consent, or contract, the corrupt edition shows the evidence of its fraught publishing history in its error-riddled text. The existence of an apocryphal edition makes it difficult to delineate exactly what we mean when we say The Joy of Cooking, thus predicting the scheme of 7CV’s many editions and formats. Yet whereas Joy’s publishing history makes its boundaries conspicuously diffuse by accident, the hyperbolic complexity of 7CV’s publishing history makes it diffuse as a feature.

0 notes

Text

Close Readings from Weird Twitter - @UtilityLimb

Although a sort of absurdist left-turn characterizes most of Weird Twitter and much of its literary progeny (like ClickHole), @UtilityLimb has perfected his own recipe and mastered its execution. @UtilityLimb’s signature move always takes something banal and familiar—a cultural reference or observation; a common turn of phrase—as its starting point. Whatever expectations the starting point sets up are then drastically betrayed or grotesquely inflated, invoking sublime horror, transgression, and often a sense of post-apocalypse or solipsism (think: Twilight Zone). This betrayal of expectations is always accomplished by a gesture of zooming out to reveal a fatal flaw in our assumptions about the world in which the action of the tweet takes place.

Largely unsung and yet hugely influential, @UtilityLimb’s work is among the most masterful in the Weird Twitter canon. The author published a modest total of 665 tweets between September, 2010 and May, 2012 then dramatically fell silent.

“how creative. the joy division album cover again,” - me, sarcastically, to the endless black & white lines pouring out the sky into the sea (@UtilityLimb, 5/3/12)

Like most @UtilityLimb tweets, this one begins in the same banal territory as more conventional tweets, with observations and commentary on millennial culture. By the time of this tweet’s publication, the iconic album artwork for Joy Division’s album Unknown Pleasures was already well established as a symbol for the millennial hipster’s vapid cultural capitalism. The sarcastic observation, “how creative. the joy division album cover again,” is exactly the kind of straight-laced, one-dimensional cultural commentary we might expect from any conventional Twitter account. But the obvious qualification, “me, sarcastically” suddenly undercuts the speaker. Only someone relatively new to being jaded would feel the need to point out the obvious sarcasm of the statement, “how creative. the joy division album cover again.” To sarcastically point out the ubiquity of the image is itself an exhausted cliché. The choice to undercut a jaded speaker with naivete represents a double irony. If @UtilityLimb’s speaker is jaded by one more hipster’s T-Shirt, @UtilityLimb is jaded by the very idea of hipsters and jadedness. Here @UtilityLimb is sarcastic toward sarcasm, jaded with jadedness, leading us to expect a reactionary embrace of sincerity. Instead the words, “to the endless black & white lines pouring out the sky into the sea” performs a second subversion, this time undercutting the reader. What we thought was a relatively innocuous symbol of consumer culture turns out to be a terrifying transgression on what we consider possible, literally swallowing the horizon. This is the transgressive zoom-out which is @UtilityLimb’s signature.

The transgressive zoom-out in this tweet absolutely relies on the order of operations. If the tweet had read “*endless black & white lines pouring out the sky into the sea.* how creative. the joy division album cover again,” the effect would be ridiculous rather than horrifying, because the transgression would be disclosed from the start. Instead the author allows us to assume it is deeply familiar (a tee shirt or a poster) before bringing it into the frame as something deeply unfamiliar. This uncanny effect of the familiar becoming very unfamiliar is doubly horrifying because it is set up to be the reader’s mistake—the “endless black & white lines” were already “pouring out the sky into the sea” when we started reading, but we hadn’t seen them yet.

The transgressive zoom-out in this tweet physically enacts jaded subjectivity as horror. The jaded subject figuratively sees cultural decay everywhere he goes, acting as if the ubiquity of one tastelessly commodified cultural symbol signals the end of civilization. @UtilityLimb literalizes this melodrama by placing his subject in a post-apocalyptic world where he literally cannot glimpse the sky without seeing the Joy Division album cover. By physicalizing the speaker’s tonal irony, @UtilityLimb transfigures it into atmospheric horror.

#utilitylimb#bandit#weird twitter#buzzfeed#clickhole#post-irony#new sincerity#joy division#unknown pleasures#dril

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

attention economy

0 notes

Text

A consequence of post-irony

Though obvious, it’s worth pointing out that post-irony is an ambiguous tonal register. By [my] definition, the post-ironic work problematizes the difference between satire and submission [to the object of would-be satire]. The meaning of an ironic statement is clear—it is the opposite of its literal meaning. A post-ironic statement leaves the reader with the dubious labor of deciding what or how much to take seriously. Did Andy Warhol love consumerism or hate it?

Graduate students Moira Weigel and Mal Ahern deftly critique the French leftist tract Preliminary Materials for a Theory of the Young-Girl by the anonymous collective Tiqqun as a post-ironically misogynist text. Imitating their source material’s style, Weigel and Ahern write,

The Man-Child wants you to know that you should not take him too seriously, except when you should. At any given moment, he wants to you to take him only as seriously as he wants to be taken. When he offends you, he was kidding. When he means it, he means it. What he says goes.

(Further Materials Toward a Theory of the Man-Child, Weigel and Ahern for @thenewinquiry)

Post-irony is a complex, multivalent tonal register (it leaves room for many conflicting interpretations) and thus it must be used with extreme care, especially as it intersects with privilege and violence.

#The new inquiry#critical prose#criticism#tiqqun#leftist#preliminary materials for a theory of the young-girl#semiotext(e)#post-irony#man-child#young-girl

0 notes

Text

Footnote to Post-irony

Faced with the obsolescence of irony, Wallace ends his essay by predicting a return to sincerity, saying, “The next real literary ‘rebels’ in this country might well emerge as some weird bunch of ‘anti-rebels,’ born oglers who dare to back away from ironic watching, who have the childish gall actually to endorse single-entendre values.” This passage is often brought up in discussions of the New Sincerity (indeed it has been quoted at length on the movement’s Wikipedia page since 2010)—a movement which rejects irreverence and instead self-consciously embraces sincerity, even at the risk of eye-rolls and dismissal as kitsch. Contemporary writers associated with the movement include Miranda July, Mira Gonzalez, and Steve Roggenbuck. Where these writers turn away from irony and back to sincerity with a renewed self-awareness, I argue that post-ironic works plunge deeper into irony.

[return to Post-irony]

#footnotes#infinite jest#david foster wallace#miranda july#mira gonzalez#steve roggenbuck#new sincerity#alt lit#post irony

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Post-irony

I think of post-irony as a tonal register in which straightforward satire becomes obsolete or irrelevant, and is therefore transcended or inverted. Often straightforward satire becomes obsolete because what would be the object of critique is so omnipotent as to preclude critique.

(Alternatively: post-irony darkly points to the omnipotence of its would-be object of critique by [partially] submitting to it.)

In his essay “E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction,” David Foster Wallace demonstrates how television precludes ironic critique. According to Wallace, contemporary (1990s) writers attempting to critique or remedy “addictive TV psychology” use “the same tone of irony or self-consciousness that their ancestors, the literary insurgents of Beat and postmodernism, used so effectively to rebel against their own world and context.” Yet, “the reason why this irreverent postmodern approach fails,” he says, “…is simply that TV has beaten [contemporary writers] to the punch.” As evidence, Wallace points to how TV shows and ads are themselves ironically self-conscious. He cites a Pepsi commercial in which a manic crowd of handsome beach bums flock to the amplified sound of a pepsi can opening, which is “utterly up-front about what TV ads are popularly-despised for doing: using primal, flim-flam appeals to sell sugary crud to people whose identity is nothing but mass consumption.” The ironic ad boost sales by inviting the individual viewer to participate in an in-joke at the expense of “the very crowd that defines him,” the Audience. For an artist or writer to satirize the TV ad becomes utterly irrelevant, since the successful TV ad already hyperbolically exaggerates its most fiendish qualities. [Footnote.]

By implying the exhaustion of satire, post-irony produces horror and humor in equal measure. The post-ironic work says: If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Traditional wisdom says that a good thesis must be soundly argued but must also leave room for a counter-argument. In other words, the argument’s evidence must be parsed infallibly; at the same time, if the reader can not disagree with the argument, then it is not argument at all but merely description.

Why is it that I reject the form and motives of the traditional academic essay but retain its tone and diction?

Do I have a complex?

1 note

·

View note

Text

Irony re: intellectual property in Tan Lin’s Seven Controlled Vocabularies and Obituary 2004: The Joy of Cooking

[note: Page numbers refer to the Wesleyan University Press edition (2010) unless I note otherwise. Generally subtract 4 from the page number to find the same content in the Lulu First Edition (2007).]

[note to people in my class: you have already read this section]

Tan Lin is sometimes mentioned in discussions of Conceptual Poetry, in part because he shares with its gatekeepers an interest in intellectual property and authorship. [Footnote: As in Kenneth Goldsmith’s New Yorker article, “The Writer as Meme Machine” (October 22, 2013), these discussions often gloss over the depth of Lin’s work in order to more concisely serve the discussion’s real purpose, which is to recapitulate and spread the doctrine of Conceptual Poetry.] The treatment of this subject in Seven Controlled Vocabularies comprises the book’s most straightforward use of irony. Lin treats the very idea of intellectual property as a joke.

In an early, telling gesture, the “Acknowledgements” page (9) appropriates the exact text of the acknowledgements page from Timothy Bewes’ Reification, or, the Anxiety of Late Capitalism (2002). Here Lin has plagiarized the very section of his book which traditionally deflects allegations of plagiarism by citing and thanking copyright holders and people who have provided help. Beyond the macro gesture to mock the institution of Acknowledgement, the way that this specific acknowledgement page grafts onto 7CV produces interesting ironies of its own. For example, Lin respectfully thanks the copyright holders of three illustrations which do not appear in the book. Page 45 does not contain a reproduction of Stanley Spencer’s famous modern biblical scene, The Resurrection: Cookham, but rather a vague and arbitrary photograph of a Nissen hut compound. The other two illustrations are said to occur on pages 237 and 256, while 7CV ends on page 222. A line break separates these ironic [mis]attributions from one more punchline—“The photograph on p. 182 is by the author” (9). The photo on page 182 is a tiny, nearly illegible, amateurish shot depicting an arbitrary slice of a street. The irony of this attribution, in contrast with the phony attributions above it, is that it is probably true—Lin likely did take this photograph, just as he likely took each of the 15 other vague, tiny, and arbitrary photographs occurring in the same chapter. Lin’s choice to assert his authorship of the photograph on page 182 is as arbitrary as the composition of the shot itself.

Lin continues to use the technique of flagrant plagiarization throughout the book. A photocopied reproduction of the index from Roland Barthe’s Image, Music, Text, followed immediately by a photocopy of the preface from Laura Riding’s Rational Meaning appears in the middle of 7CV (150-159). Within 7CV, Lin has promised us a foreword by Riding at least three times - on the back cover and on two of the book’s three title pages. Thus the appropriation of Riding’s preface represents a particular misdirection- 7CV does contain a preface by Laura Riding Jackson, but that doesn’t mean it was written for 7CV, or even that appears at the beginning of the book where a preface should be.

These repeated ironic gestures create a clearly antipathetic tone toward intellectual property. And yet, tucked away at the very end of the seventh “Controlled Vocabulary,” preceding “Part II,” (what we imagine must be the “Obituary”) is an earnest permissions page (165) citing the owners of many (though not all) of the images and texts included in the WUP edition. At the sight of such an obvious contradiction of what seemed to be Lin’s unwavering anti-intellectual property position, the reader may blanch. Since the genuine permissions page is absent from the first Lulu edition, we may wonder if Lin has simply sold out in order to be published by a legitimate press. In fact, he likely did. Here it is important to remember that this same book offers to sell itself to us as a “Home + Lifestyle” plastic placemat for $54 (168). Further examination of Lin’s tone toward late capitalism may reveal that for him, the idea of "selling out” is obsolete.

#intellectual property#appropriation#conceptual poetry#kenneth goldsmith#tan lin#irony#tone#the joy of cooking#seven controlled vocabularies and obituary 2004

1 note

·

View note