#semiotext(e)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

has this been done before?

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wednesday, July 26, 2023 Doors 7:30 pm The Complete Fear of Kathy Acker, w Jack Skelley

~ A Semiotext(e) book launch w readers, visuals and music.

Jack Skelley performing from The Complete Fear of Kathy Acker w videoz by Lydia Sviatoslavsky & soundz by Stephen Spera. Special guest readingz by Amy Gerstler, John Tottenham, Benjamin Weissman & Jackie Wang. MC Lily Lady.

Info: https://www.poeticresearch.com/events/the-complete-fear-of-kathy-acker

.

.

This will be my last reading in LA for a while since I'm leaving on July 30 to do a year-long fellowship at Harvard. Might try to perform with my harmonium! (It will be my first time!!)

#Jack Skelley#literature#poetry#event#events#semiotext(e)#Amy Gerstler#John Tottenham#Benjamin Weissman#Jackie Wang#performance

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Can the Monster Speak? by Paul B. Preciado

Paul B. Preciado's "Can the Monster Speak?" is a fantastic critique of the field of psychoanalysis and it's treatment of sexuality and gender.

Can the Monster Speak?: Report to an Academy of Psychoanalysts is exactly what the subtitle suggests. It is the publication of a speech that Paul Preciado, a non-binary trans man, was invited to give to a group of psychoanalysts at the École de la Cause Freudienne in 2019, and one he was not able to finish as the audience harassed him off the stage. The speech is both an effective criticism of…

0 notes

Text

what was and what cannot be

The first thing I noticed was the novel's style—the oscillation from many short sentences to long ones, compound in structure; the pivots from feeling to dispassion and back again—and the protagonist's use of “I guess”:

For the longest time I didn't call it turning tricks. When I'd leave work, cross the street to the train station, and if some guy—man I guess you'd call him—had come off the train, I'd take his money. We'd do it in his car. I'd work maybe twenty minutes. Get maybe twenty dollars, which was good compared to what I'd get at my job across the street. Besides, it's hard to get more in a car. At least I told myself this. Though I guess how much depends on what you'd do for it.

Such language can sometimes be a marker of youth. It can suggest uncertainty or diffidence. It can also represent the struggle to compass something—like feeling that is so large it fractures language. It's clear early on in Heather Lewis’s posthumous novel Notice that its young narrator grapples with secret, primal forces, certain deep currents that run under conscious, ordered life. “While it's true I needed the money,” she says, “that's not all I needed from it”:

I understand the need for telling people that, people outside it. But the thing is, I could never really see anyone as outside it. What the extra need is, the thing besides money? I've never pinned it down. I know it's there, though.

It's hard to describe Notice without dipping into Lewis's own story; her life shares so many features of her narrator's. As Melissa Febos describes it in the introduction to the novel's 2023 reissue by Semiotext(e), Lewis too was abused by her father, viciously, in ways that marked her whole life; she too was neglected by her wealthy family; she too turned tricks; she too found succor in the love of women. It's a truism to talk about people dying tragically young, but I think Lewis did: taking her own life, having been unable to find a publisher for Notice, and driven into relapse and breakdown by the criticism received for the other novel, The Second Suspect, into which she transposed many of Notice's details. I wish I could've read the novels she had yet to write.

It's a truism too to say that we write our stories to heal ourselves. A novel isn't therapy, and I don't think Lewis meant to heal; this novel's ending—a bleak one; "one of the hardest endings of any book I've read," as Febos puts it—proves as much. But to write one's story can represent an attempt to answer, through narrative and not facts, impossible questions: What is this thing inside me? Was it born with me or was I given it? Does everyone have it or am I alone born with it, condemned to it?

While working as a prostitute, Notice’s protagonist, “Nina”—her real name is never revealed—falls in with a couple, an unnamed man and his wife, Ingrid, who lock her into a sadomasochistic game. The man uses Nina to recreate the murder of his own daughter, at his own hands. Ingrid hovers in between, both victim—burned by her husband's cigarettes, kicked and beaten by him—and complicit, by virtue of her passivity and resignation.

Nina and Ingrid develop a connection, despite their shared degradation and because of it: Ingrid mother, Nina daughter; both lovers, too; both victims of this unnamed man who tortures them. Nina isn't the first woman Ingrid and her husband have brought into their game, but she's the first to incite to Ingrid to leave. When she does, the man responds by arranging Nina's arrest by authorities, after her violent violation by the officers. From jail, Nina moves to an asylum, and the care of a counselor, Beth, who becomes Ingrid's counterpart in yet another awful triad. The rest of the novel charts Nina's struggle between Beth on the one side, and what she represents, and Ingrid on the other. Beth seeks to care for Nina and to know he; Ingrid haunts Nina, first by her absence and then her return from wherever it was she'd run to, bringing the threat of her husband with her.

This description may suggest that Nina's quest is to choose Beth over Ingrid: to choose salvation over misery. And Nina does choose Beth, letting Ingrid return to her husband. That choice does not bring healing. The relationship with Beth doesn't last. And what, in a different novel, would have been a moment of triumph—the moment, in the second-to-last time they sleep together, when the “howling place” inside of Nina “that'd been so sore, sore from my very beginnings,” transforms, by virtue of the permission Beth gives her to just rest, to a state that’s “not huge and crazed now, but quiet and ageless...hushed and tranquil and endless”—here, that moment brings Nina's most pronounced degradation, at the hands of two men hired by Ingrid's still-vengeful husband. The scene goes on for pages. At the end of it, one of Nina's assailants, Burt, tosses a bullet from the gun they've used to menace her at her crumpled body. The novel ends with that bullet in Nina's pocket, where she keeps it always.

Including at the bar where she sees the other assailant, Jeremy, again. By this time she's living more or less a normal life. Ingrid and her husband are both gone. The relationship with Beth is conventional and antiseptic; Beth’s experience, finding Nina after Burt and Jeremy have done with her, has ended something vital in it, and they don't talk about any of what happened between them. Nina works to keep her life within the bounds of the conventional, and to all appearances she succeeds. But the sight of Jeremy makes her confront a truth: What she has always wanted is death. Her lifestyle has been a way as to seek death while pretending to flee it. Being with Beth has shown her the way toward something greater than this, but to truly choose that way, to choose life, requires an even greater strength that she does not possess:

And so, with it too soon for doing things differently and too late to do them the same, all I could do was stay in this stasis... The familiar heaviness crept into my limbs as I thought these things... The blackness came behind the heaviness. Came on comforting and big as always. But not deathly. Not exactly. Not for tonight at least. And this let me believe I could maybe just dip into it. For little bits of time. Go to it without that eerie pull to stay and, in this way, maybe get some rest. Get some actual sleep that might start me mending. So I went to it, greedy as always. But, even with that slumber taking me over, and then taking me under, I knew that leviathan thing slept in this same darkness. Lay with me, too. Resting, biding its time.

One of the hardest endings of any book I’ve read.

This novel is so clearly a depiction of trauma, but something about that word feels lame next to this novel, written as it was in the early 1990s, before that word became a part of our lexicon so normal you could joke about it, if you wanted to. This is such a close and careful and painful depiction of it. Sometimes Nina’s so watchful, so intently calculating risk (how far will this man go?), and so incredibly aware of threat: knowing immediately, for instance, that her attraction to Ingrid poses a terrible danger. Other times she's not nearly watchful enough, caught off-guard by things that don't register until it's too late. Currents of dread would run through me as I read this book—for instance, when Nina recounts the first time Ingrid's husband strangles her. She speaks in a register like that of police testimony—dispassionate, so careful about distinguishing what she remembers from what she cannot recall and can only assume:

This meant I could scream but then I don't think I tried it. I think maybe I cried, though I'm not sure of it. I know what he did lasted a long time...

I was struck too by the description of the sensation that takes hold of Nina when, in the course of a session with Beth, she comes close to thinking seriously about her own situation, in a deliberate and concerted fashion and not a fleeting one. It's a terrible heaviness, an “inability to get on with it,” this “tremendous pull to give in, to give up.” I know enough about trauma now, with what feels like every third millennial reading The Body Keeps the Score, to know this can happen when you face it: the emergence of this massive exhaustion, the body's attempt to shut down feeling it knows you can't take. Perhaps when Lewis was writing, this was all new. Perhaps that's why this novel was rejected by editors eighteen times before Lewis shelved it altogether.

Or take Nina's repeatedly returning to the parking lot where she picks up clients—including Ingrid's husband—even when one would assume the punishment of her experience with Ingrid or in the asylum or the promise of something different in Beth would warn her against it. One could say she should've known better, but some things go beyond common sense. It's the same with the decision that Beth makes to get Nina off, after finding her wrecked by Burt and Jeremy's assault, in what one can only assume is an attempt to comfort, to speak to Nina in the only language Beth thinks she might understand. It feels like horror.

My body wanted her, while the rest of me didn't. My body maybe even needed her, needed what she was doing. And so this was another time it left me down... She had to work at it but she did finally bring me off, though it happened in a dead, overdue way, not satisfying either of us.

Notice contains some of the most lucid analysis of sex and power I've ever encountered in a novel. Their conventional outlines are present in Nina’s experience with men: Ingrid’s husband, or Burt and Jeremy. But Lewis also charts, with painful and even exhausting exactness, the holds Ingrid and Nina have on each other, and the shifts of power from Beth to Nina and back again as the two of them try to make genuine contact—which requires openness, openness that can feel indistinguishable from victimhood. There’s the "purring" sensation Nina feels when she first begins to bond with Beth—a feeling that permeates her whole body, marking the emergence of true desire, lesbian desire, distinct from sex with men—which one is tempted to read as a force of liberation, though it also has an intensity that registers as terrifying for Nina, so long objectified and objectifying. There are also these places Nina discovers inside herself as her relationships with Beth and Ingrid continue. One place "[feels] early, as in ancient, but still very young," and becomes palpable when Beth is inside her, as she begs Beth for more; another is a place of "deadness" that—in a moment that should be tender—renders Nina altogether unable to engage. When Beth tries to comfort her, holding her, whispering soothing things she can't make out:

She kept on this way and the urge I felt was to cry. To finally let myself do this because it seemed I'd needed to for a very long time. But having no knowledge of what I would be crying about stopped me. It bewildered me to feel something so strongly but without content.

There's something annihilating in this—in the way that the form of feeling can emerge before the content of it can. And it's annihilating too to see the moment Nina does finally allow this emotion to emerge, “to cry from [a] place so big and so old I didn't know where it began or what it concerned.”

As I read all this, I came to think that Notice was working to offer an alternate ethics to that of power and the presumptions and exertions of force on which power depends. Characters like Beth and Nina and even Ingrid—whose relation to Nina, upon her reappearance in Nina's life, is tender, though ultimately unsustainable—they wait until moments are right, and they make progress slowly as they unlearn old codes. Take for instance Nina's reunion with Ingrid, the moment she sees Ingrid's body, and the bruises, dealt by her husband, that run up and down her side:

The sight of them caught me up, nearly stopped me. For an instant it ran through my mind to ask how it had happened. But I knew this, too, was about me, about keeping me from myself. And I knew it wouldn't work. Besides, I knew exactly how she'd come to be hurt in this way. I could see it all—her on the floor and him kicking her. And I knew that the times I'd had this done to me I'd felt the least human of all. To make her revisit it just to spare myself, this seemed close to something he'd do.

“Who did this to you?” is the question asked by someone who's never been a victim themselves and thus must keep themselves from knowledge of victimhood as though victimhood is an aberration, something that could never happen to them. Nina's refusal to ask the question—the decision to simply be there, with Ingrid, in silence—is what allows Ingrid to weep, to ask her to stay, to “look young and afraid” and yet be comforted, not punished. It allows Ingrid to do the opposite of what trauma conditions.

And yet the new ethics—discovered by trial, bravely but clumsily, and at great cost—can't outlast despair. Nina’s relationship with Ingrid ends because Nina recognizes—even in the sweetest moment they’ve yet shared—that there's an “emptiness”: “Ingrid and I weren't so very alike, or weren't anymore. What worked for her seemed now to fail me. Couldn't keep pace with what Beth had begun...” Which is to say: Nina’s relationship with Beth brings a consciousness of what is necessary that renders the life of the victim, Ingrid’s life, her own life, unsupportable. And yet the relationship with Beth, which one would assume represents healing, ends in a kind of betrayal, or is frustrated not long after it’s begun. Perhaps it's when the only language Beth can find to speak to Nina, after her assault at Burt and Jeremy’s hands, is the sexual. Or it's the existential state that Nina's ultimate failure with Beth reveals to her. “I'd been left with two courses,” she says: “do it myself”—that is, die—“or undo the things that had put the desire in me to begin with”: that is, be with Beth. “I knew I wasn't up to offing myself,” Nina adds, “and I couldn't see a way to start toward the other passage.”

It's agonizing to contemplate where Nina ends the novel—frozen in limbo, suspended so cruelly between what was, her past, and what cannot be, what feels impossible to claim or make real: a future; a joyful life. Confronting conditions Lewis herself perhaps faced and simply could not get clear of. What justice is there in such a condition? Why are some of us awakened to that leviathan thing, constantly sent to it, paralyzed by it, unable to live free?

When I was younger and stupider, I would sometimes lament my conventional, middle-class life for its lack of artistic material. I have long since relinquished this, but novels like Notice teach me all over again the vanity and stupidity of that desire. They remind me, too, that what I can offer is witness.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Earlier (2023)

Sasha Frere-Jones

Semiotext(e)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Now that 2024 is circling the drain, I’ll start regaling you with my “Favourites of the Year!” Most noteworthy passing: American author, playwright, actor, essayist, art critic and all-round bête noire Gary Indiana (né Gary Hoisington, 16 July 1950 – 23 October 2024) died of lung cancer aged 74. (As Indiana told an interviewer in 2014 “I’ve been smoking since I was practically two years old.” His brand of choice was Camel Filters. It’s amazing the dissolute Indiana lasted this long, considering his peers were people like David Wojnarowicz and Cookie Mueller). Anyway, words like “lacerating” and “scathing” barely suffice when discussing Indiana’s oeuvre. When I was in my twenties, buying each new work by Indiana and Dennis Cooper was de rigueur. (I probably purchased them at the long-defunct radical Compendium bookstore in Camden Town). I moved around a lot and wound up re-selling them to used bookstores for a pittance. Then Indiana’s books mostly lapsed out of print! (In more recent years, they’re gradually being reissued by Semiotext(e)). It didn’t help that Indiana gleefully burnt bridges throughout his life. As one of his associates noted almost admiringly, “He went through agents the way I go through t-shirts.” Some of his most noteworthy books were speculative fiction inspired by true crime figures like the Menendez brothers (Resentment: A Comedy (1997) and Andrew Cunanan (Three Month Fever (1999). (The viewers who clutched their pearls over Ryan Murphy’s recent Menendez miniseries would REALLY lose their shit over Indiana’s book. Indiana would have swooned over Luigi Mangione). For anyone interested in investigating Indiana, his memoirs I Can Give You Anything But Love is available in paperback. And his interview with Butt in July 2024 is essential. As its intro summarizes: “Gary earned his notorious reputation over the course of his unflinching, decades-long career. He writes about addiction, alienation, corruption, exploitation, obsession, perversion, power and sexuality with unfiltered candour, leaving no room for politeness … His tendency toward destructive obsession was kept in check by his brilliance, cutting humor and heart.” Pic: “Gary Indiana Veiled” by Peter Hujar, 1981.

#gary indiana#peter hujar#lgbtqia#bete noire#bad boy#lobotomy room#queer#i can give you anything but love#three month fever#resentment a comedy#the menendez brothers#andrew cunanan#the village voice#horse crazy#rent boy#avant garde#art critic#lacerating#art criticism#filth elder#role model

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Before you are allowed to enter the MIT Press Bookstore they make you swear eternal loyalty to noam chomsky and also every random french guy published by semiotext(e). Anyway look at this cool haul 😎

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bibliography / further reading

Andrew X (2001) “Give up Activism.” from Do or Die, issue 9

Anonymous (2001) At Daggers Drawn with the Existent, its Defenders and its False Critics (London: Elephant Editions)

Anonymous (2003) Call

Anonymous (2011) Desert (St. Kilda, UK: Stac an Armin Press)

Anonymous (2006) Down with the Empire, Up with the Spring! (Wellington: Rebel Press)

Anonymous (2003) “Insurrectionary Anarchy: Organising for Attack!” from Do or Die, issue 10

Anonymous (2013) The Issues are not the Issue

Anonymous (2015) “The Veil Dops.” from Return Fire, issue 3

Bari, Judi. (1995) “Revolutionary Ecology: Biocentrism & Deep Ecology.” from Alarm

Best, Steven, & Nocella, Anthony J. II (2006) “A Fire in the Belly of the Beast: The Emergence of Revolutionary Environmentalism.” from Igniting a Revolution: Voices in Defense of the Earth, ed. Best, Steven, & Nocella, Anthony J. I (Oakland: AK Press)

Best, Steven (2014) The Politics of Total Liberation: Revolution for the 21st Century (New York: Palgrave Macmillan)

Bey, Hakim (2003) TAZ: The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism (New York City: Autonomedia)

Biehl, Janet (2007) “Bookchin Breaks with Anarchism.” from Communalism

Bookchin, Murray (2001) The Spanish Anarchists: The Heroic Years 1868–1936 (Oakland: AK Press)

–––. (2004) “Listen, Marxist!” from Post-Scarcity Anarchism (Montreal: Black Rose Books)

–––. (2005) The Ecology of Freedom: The Emergence and Dissolution of Hierarchy (Oakland: AK Press)

Bonanno, Alfredo (1977) Armed Joy (London: Elephant Editions)

–––. (2000) The Insurrectional Project (London: Elephant Editions)

–––. (2013) Let’s Destroy Work, Let’s Destroy the Economy (San Francisco: Ardent Press)

Dauvé, Gilles (2008) “When Insurrections Die: 1917–1937.” from Endnotes, issue 1

–––. (2015) Eclipse and Re-emergence of the Communist Movement (Oakland: PM Press)

Gelderloos, Peter. (2007) Insurrection vs. Organization: Reflections from Greece on a Pointless Schism

–––. (2010) An Anarchist Solution to Global Warming

Haider, Asad. (2018) Mistaken Identity: Race and Class in the Age of Trump (New York: Verso Books)

Invisible Committee. (2009) The Coming Insurrection (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e))

–––. (2015) To Our Friends (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e))

–––. (2017) Now (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e))

Næss, Arne. (1993) “The Deep Ecological Movement: Some Philosophical Aspects.” from Environmental Philosophy

Nibert, David (2002) Animal Rights/Human Rights: Entanglements of Oppression and Liberation (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield)

Öcalan, Abdullah (2013) Democratic Confederalism (Cologne: International Initiative Edition)

–––. (2017) Liberating Life: Woman’s Revolution (Cologne: International Initiative Edition)

Pellow, David Naguib (2014) Total Liberation: The Power and Promise of Animal Rights and the Radical Earth Movement (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press)

Pellow, David Naguib, & Brehm, Hollie Nyseth (2015) “From the New Ecological Paradigm to Total Liberation: The Emergence of a Social Movement Frame.” from Sociological Quarterly

Perlman, Fredy. (2010) Against His-tory, Against Leviathan! (Detroit: Black & Red)

ed. Schwartz, A. G., Sagris, Tasos; Void Network. (2010) We are an Image from the Future: The Greek Revolt of December 2008 (Oakland: AK Press)

Singer, Peter (2009) Animal Liberation (New York: Harper Perennial)

ed. Strangers in a Tangled Wilderness (2015) A Small Key can Open a Large Door: The Rojava Revolution (Strangers in a Tangled Wilderness)

Tiqqun. (2011) This is Not a Program (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e))

van der Walt, Lucien, & Schmidt, Michael (2009) Black Flame: The Revolutionary Class Politics of Anarchism and Syndicalism (Oakland: AK Press)

Zerzan, John (1999) “Agriculture.” from Elements of Refusal (Columbia, MO: C.A.L. Press)

#book lists#anti-civ#reading lists#anti-speciesism#autonomous zones#climate crisis#deep ecology#insurrectionary#social ecology#strategy#anarchism#climate change#resistance#autonomy#revolution#ecology#community building#practical anarchism#anarchist society#practical#practical anarchy#anarchy#daily posts#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

HUBBIE: It’s always my fault. Everything’s always my fault. When your dog died when you were four years old it was my fault. When Three Mile Island was leaking away Mother threw out her new General Electric microwave cause she said it was a UFO Martian breeding ground: I caused that one. Your commie actor friends’re always telling me I’m not political enough cause I won’t stand on streetcorners and look like a bum just to hand out that rag (SEMIOTEXT(e)) they call a newspaper a bum wouldn’t even use to wipe his ass with - some communism - and then they say I’m responsible for the general state of affairs. All I do is work every day! I never say anything about anything! I do exactly what every other American middle-aged man does. Everything’s my fault.

WIFE (soberly): Everything IS your fault. (The wife starts to cry again.)

Kathy Acker, Great Expectations

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

drawing from semiotext(e)'s schizo-culture volume compiled by sylvère lotringer; texts, from paul virilio' s collaboration with her, crepuscular dawn & pure war

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

A comrade captured a sneak peek of Robert Hurley's Tosquelles translation, forthcoming from Semiotext(e)--can't wait!!! Maybe I should call the anti-psychiatry/psychoanalysis reading group I've been hosting for the last few years The Ship of Fools!

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

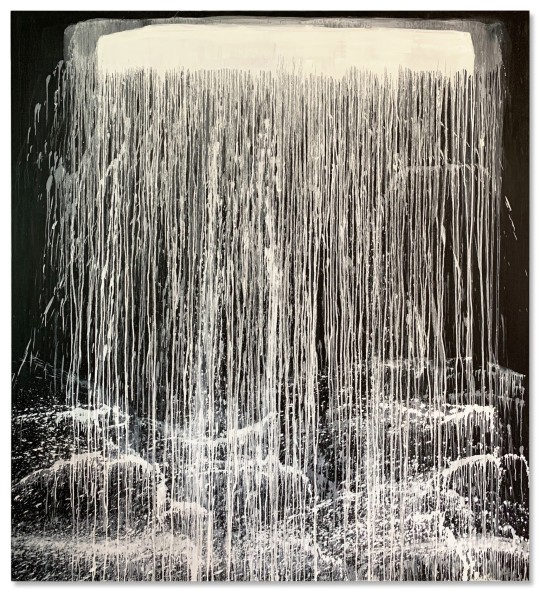

Pat Steir (born 1940) is an American painter and printmaker. Her early work was loosely associated with Conceptual Art and Minimalism, however, she is best known for her abstract dripped, splashed and poured “Waterfall” paintings, which she started in the 1980s, and for her later site-specific wall drawings.

"Over the course of her education at the Pratt Institute and then the Boston University College of Fine Arts, Pat Steir studied under Philip Guston and Richard Lindner. She first worked as an illustrator, graphic designer, and became friends with well-known conceptual artists such as Sol LeWitt, Lawrence Weiner, and others. Her meeting with Agnes Martin (1912-2004) left a deep impression on her, and as a result she turned to a brand of abstraction that did not exclude reality. Apart from her pictorial practice, she also worked in publishing: from very early on, she was hired by feminist magazines, including Heresies and Semiotext(e).

Her paintings act as an inquiry into the nature of painting itself. She creates series focused on landscapes and self-portraits that she periodically revisits. For example, Waves and Waterfalls (1982-1992), Summer Moon (2005), Gold and Silver Moon Beam (2006), Water & Stone (2010), are nods to the landscapes of Courbet, Turner, and Hokusai. Their numerous vertical lines, produced by as many evenly-spaced drips, echo Jackson Pollock’s dripping technique. In the famous Waterfalls series, the artist dilutes the oil paint, which streams down from the top of the painting to the ground. About Steir’s self-portraits, Denys Zacharopoulos wrote: “Self-Portrait is not a painting and does not depict a face, her face in any kind of way. This plural expression, reversible, equivocal, changing, at one with time, proliferates into an infinity of others in space, her shape-shifting and mercurial being, both enveloping and enveloped, is the “self-portrait (Pat Steir, 1990)”.

Marion Daniel

Translated from French by Toby Cayouette.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Faced with these inescapable facts, even the Marxist economist loses himself in professorial paralogisms, concluding that capitalist reason is thoroughly unreasonable. This is because the logic of the present situation is no longer of an economic but of an ethico-political kind. Work is the linchpin ofthe citizen factory. As such, it is indeed necessary, as necessary as nuclear reactors, city planning, the police, or television. One has to work because one has to feel one’s existence, at least in part, as foreign to oneself And it is the same necessity that compels THEM to take “autonomy” to mean “making a living for oneself,” that is, selling oneself, and in order to do so introjecting the requisite quantity of imperial norms. In reality, the sole rationality driving present-day production is the production ofproducers, the production of bodies that cannot not work. The growth of the cultural commodities industry, of the whole industry of the imagination, and soon that of sensations fulfills the same imperial function of neutralizing bodies, of depressing forms-of-life, of bloomification. Insofar as entertainment does nothing more than sustain self-estrangement, it represents a moment of social work. But the p icture wouldn’t be complete if we forgot to mention that work also has a more directly militaristic function, which is to subsidize a whole series of forms-of-life-managers, security guards, cops, professors, hipsters, Young-Girls(see “Preliminary Materials for a Theory of the Young Girl” [Semiotext(e): Intervention Series #12]), etc.-all of which are, to say the least, anti-ecstatic if not anti-insurrectional.

This is not a program, Tiqqun

4 notes

·

View notes