Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Something Borrowed || Alien: Romulus

My lord is it hot in Texas. I think its quaint that people used to live in this state without a hint of air conditioning, in full jeans, boots, shirts, frocks, bonnets, hats, and anything else you think they might wear on the range. And then some time passed, people were tired of boiling, and the modern movie theater offered a respite from the terrible burden of the hot August sun. You can sit down and blast off to colder climates, like the north pole, the moon, or the dark reaches of space. You may not know this but many of the Christmas or winter classics we adore today came out in the summer. But today, we are in the cold reaches of space in the grip of an all too familiar monster. I went to today's showing of Alien: Romulus with almost no excitement. Almost. This franchise has burned us all too many times ever since James Cameron put down the camera at the end of the unnecessary and beloved sequel to what could be one of the best films of the 20th century. Alien and Aliens have an undeniable gravity and we are stuck in their orbit. Like the fictional Weyland-Yutani corporation, studios greenlight return trips to these worlds. They know we still can’t turn down the journey, and they can’t leave the chance to profit off visiting these creatures over and over again. But a body with gravity is hard to fell and no film in the franchise has been able to truly kill the beast. Alien: Romulus instead chooses to worship at the feet of the masters in hopes of gaining ground, despite the treacherous nature of standing upon giants.

There are no spoilers in space. You will see them coming like the story of Star Wars, marked as it flies through space. A quick synopsis: Romulus takes place 20 years after Ripley defeats the original terror in Alien. Miners working for the Weyland-Yutani corporation toil in a mine on the far side of a planet that never sees the sun. Rain (Caliee Spaeny) and Andy (David Jonsson) are two orphans whose parents died of cancer breathing in the fumes in the mine. After finishing her required hours of her contract on the planet, she decides to put in for a transfer to a planet with a sunrise. The corporation decides to double all miners required contract time due to the continued loss of people due to cancer. With nothing left to lose and goaded by other orphaned children, they choose to try and rob an unmanned spaceship that happened to drift into the mine planet's orbit before anyone at the company realizes. The prize? A series of cryopods needed for the 9 year flight to the closest planet outside of the corporation's grasp. But will the cost be worth the price?

In a series that spans hundreds of years, it was quite the surprise that we would land within 20 years of the origin of the franchise. Certainly a bold choice. At this point, it's probably in your best interest to know the timeline. From the earliest in the series timeline to the latest (series year /release year / director):

Prometheus (2093 / 2012 / Ridley Scott)

Alien Covenant (2104 / 2017 / Ridley Scott)

Alien (2122 / 1979 / Ridley Scott)

Alien Romulus (2142 / 2024 / Fede Alvarez)

Aliens (2179 / 1986 / James Cameron)

Alien 3 (2179 / 1992 / David Fincher)

Alien Resurrection (2381 / 1997 / Jean-Paul Jeunet)

Bold choices, bold rewards. The greatest thing about Alvarez’ turn at the helm is that before anything happens, before the title card runs, we see the wreckage of the Nostromo, as if it were a promise of things to come. Just a day before seeing this film, I asked why the newer films, Prometheus and Covenant, abandoned the now low-tech futurism of the original film? The small tube screens, grainy communications, big mechanical keyboards, switchboards, heavy levers, and basically anything the early 80’s would have used to communicate science fiction future. Ridley Scott himself already perfected the tactile feel of working in space with his origin story, Alien. More than likely, it was simply a stylistic choice of the time. The human future looks different now. Our corridors are stark white, our screens flat, our interfaces button-free. But so much of the grit left the screen when our spacefarers traded buttons that click with finger swipes and hand motions. Romulus returns to form and brings that tactile nature back to the screen, and with it, a real sense that people live and work there. The world is lived in, not designed.

Our characters and their story leave little for our actors to chew on with one standout in David Johnson as Andy. What starts as a one note character doesn’t really grow per say, but like the xenomorph, he grows in you. Out of everyone, he is the one I want to see more work from. Sometimes its not the song, but the pitch perfect note that you remember. As for the film's story, without giving anything away, the forward momentum of the film builds in such a way that the rest of the actors never really get to shine the way the actors did in Alien and Aliens. Sigorney Weaver battles with a lack of control and only succeeds when she takes it. And we get to see her realize this as the people in power fall away. In Romulus, we have a different set of circumstances that you could imagine excuses this absence of growth. With an average age that feels far below any of the other films, Romulus creates an atmosphere of inexperience across the characters, which would be fine, but it doesn’t appear to be of any consequence to the story being told in the film. For instance, there is no other thematic purpose to the characters being orphans other than to chide the churn of human labor in capitalistic imperial enterprises like Weyland-Yutani. As far as I can tell, almost any thematic or metaphorical point born of Romulus is shallow. Worse than that, this single layer is reminiscent of another space franchise and certainly a cause for pause. I couldn’t help but feel a disturbance in the fabric of cinema, a feeling I have not felt since the release of Star Wars: The Force Awakens. But hold your groan folks, unlike the The Force Awakens, Romulus conceals itself better than most. Almost as if it was the Dark Side of The Force.

Under its dark shroud is an entertaining rebuild of both Alien and Aliens. The first half of the film is a homage to Ridley Scott, the back half to James Cameron. Alvarez uses his runtime to create something more unique than anything thought of in J.J. Abrhams turn with Star Wars. But like Abrhams turn, it’s a reconfiguration of the base model. It takes what we already are familiar with and constructs a version with a modern twist. Like the VW Bug of the 60’s and its 2000’s counterpart. There was no new lesson to learn, nothing to expand upon, just beautiful carnage and delicious retro sci-fi ships with interiors to match. The problem is that if this film is successful, will it spawn a spiritual Star Wars sequel? The Last Sith? Probably not, but in so much as this film has no original ideas, it does create a new branch to follow during its runtime. As much as the characters lack in richness, the inspection of the callous nature of Weyland-Yutani as an entity is much more clear in this film than any other. Specifically because we see both their heavy handed nature and the method of their control over the daily lives of people in their employ. Before this film, the company seemed to loom in the background, like the parent company of a conglomerate full of child companies who have never met their owner, bought from a financial broker before they learned to run. You can almost hear the takeover speech from the c-suite, “We have been bought, but nothing changes”.

I enjoyed my relief from the Texas sun, sitting aglow in another tale of how the universe is ultimately indifferent to humanity. Put another way, how lucky we are to be alive. Put one more way, how unlucky we are to recognize any of this at all. The dichotomy of being able to look into the abyss only to see it stare back at you is palpable in the Alien pantheon. Alien: Romulus is no different. Where the other films struck out striking out for something new, this film plays it close to home for better or worse. It is immensely entertaining and immediately engrossing, a heavy familiar coat. And while it leaves me with confidence in everyone who made it, I don’t have much confidence in its addition to the legacy that is Alien. This series has more swings for the fences than any other like it, and because of that, even its failures are notable and re-watchable. I re-watch films to see something new I didn’t see the last time, but I feel like that will be exhausted in the next couple of viewings, where films like Prometheus and Covenant will have me re-examining why they failed for years to come. What could they have done differently? Why did they make one choice over another? All of this is clear in Romulus from the first viewing. Because it looked damn good. Because they already know it will make for a good time at the theater. And you while you can blame them for not taking too many chances, you can’t say it wasn’t a good time.

#film#review#Alien#Alien Romulus#Cailee Spaeny#David Jonsson#Prometheus#Alien Covenant#Fede Alvarez#James Cameron#Ridley Scott

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ryan, Wade, Logan, and Hugh || Deadpool & Wolverine

I have been on a bit of hiatus from seeing films in the theater, but what always seems to bring me back is even the faintest hint of good action comedy or the glimmer of a return of some legacy. In Deadpool & Wolverine, you get the promise of both in a single package. But I waited so long because I was still apprehensive. It bothered me more as time went on because it was so well received, as of now I believe it's the highest grossing “R” rated film of all time. The public largely isn’t a good barometer of whether anything is good or not, certainly not the amount of money it brings in, and definitely not the collective critical conscience. Word of mouth from trusted sources. People you love to disagree with. When both of those sources agree you simply have to take a look. I brought one of those people I disagree with, my father. A man who claims to hate the profane, but indulges in all sorts of films with deeply profane language, especially ones starring cops or detectives. Still he has always had a love for the X-Men, for Wolverine, and the chance to see him in the iconic 90’s suit was enough of a draw despite his lack of interest in Deadpool. He sat through all the violence, all the gore, all the dirty innuendo, the implied buttsex, and the 4th wall nods to the camera. He was the balance to my indulgence, and as I glanced over at him, I saw in his stoic stare, fingers resting on his temples like he had a headache, just how much it bothered him to see the swearing and the gore, and I knew in that moment that we might have a home-run on our hand.

Out of the gate, I’ll go ahead and assure you that the spoilers for the film will be marked at the very end of the article, and the initial review will simply go over the main points and my thoughts on the film in general. All I can think about right now is how I wish I was clever enough to write a review in a voice that broke the 4th wall, if there is even such a thing.

I am not sure if it's worth explaining the plot of the film, because it feels as though by design that it hangs around in the background, simply a vehicle for the jokes. Going into most action comedies, the driving force is usually the plot with the attached jokes along the way. With a franchise like Deadpool, forced to merge his well thought out and narrow franchise with Marvel, limited as it was by the copyright protections and constricted access to characters outside the Fox owned universe, you would be wise to be concerned that this wouldn’t be handled well. Even though both previous Deadpool films should have proved this creative team is a well oiled machine, I was still surprised by how well they merged their ideas into the Disney Marvel conglomerate. This film is constructed upside down, with the jokes being the engine and the plot being the fuel. Comic moments are designed in which the plot flows through them to create the momentum instead of the plot having appropriate jokes to follow the action. When the comic moments collide with the plot, you get these uniquely Deadpool action moments, with his masked smirk, potty mouth, and penchant for splitting bodies apart starting at the taint. It's quite an elegant display of talent that you don't see too often. If I had to make one thing clear, this action comedy redesign is the shining crown on Deadpool’s tight ass.

To satiate the curious, let me pour out the fuel for you, though common sense would tell you not to huff fumes, but it's your funeral. Wade Wilson is having another downer moment. In a desire to prove to himself that Deadpool is an important cog in the new Marvel Cinematic Universe he has found his way into, he tries to join the big leagues at Marvel headquarters. When he doesn’t make the cut, he gets depressed and the love of his life, Venessa, decides he needs to grow before their relationship can continue and moves out. Deadpool is then recruited by an interdimensional agency that keeps the multiverse from unraveling, which he is genuinely excited about. Only, the agency decided that Deadpool is the only thing left in his home universe that can be useful and relay to him they plan to destroy it prematurely. They plan to destroy it because the central character from his universe, Logan, perished heroically in a completely unchangeable Fox story cannon. Realizing the now dead Wolverine is the center of his home universe, Deadpool sets out across the multiverse to find the perfect Wolverine to replace his own so he can thwart the multiverse administrator villains and stop the destruction of his universe. Unfortunately, the only one he can find is a Wolverine that failed to live up to the legend of any other Wolverine’s from any other universe. This exhaustive story presentation is brought to you by the people who overthink Deadpool.

Brilliantly, this setup appears to be born out of conversations with a possibly real Disney boardroom. Disney appears to have told Ryan Reynolds and the Deadpool team that when James Mangold, director of Logan, closed the door on the X-Men universe when he put Logan out to pasture, and that all the other characters and creative choices across the Fox cannon were now worthless. Except for him. Ryan and Deadpool radiate star power, and Hugh Jackman had already confirmed he was done playing the Wolverine. This transformation of real world conversations into compelling meta-narrative is the part that feels genius. Not only did they write a narrative to fit the world in which they were writing Deadpool, they found a way to make that an entertaining bedrock of their film. And then they flipped it one more time, made this narrative the background story, the fuel as it were, of the film instead of the engine. They made the comic moments the focus, the action the result, and their creative purpose the driving point. Like Deadpool on screen, the creative team wants to matter and maybe the only way for anyone to believe in them is for them to prove that all that creative work at Fox has more value than the Disney executives can possibly imagine. As a result, they spoke the one language any executive knows, that language translated to now 1 billion dollars in ticket sales. Creative work again saved by the power of capitalism. (I hope that hits with the irony intended. I am not in the Deadpool creative team.)

Ryan Reynolds and Hugh Jackman are still sublime as their alter egos. They define these characters for an entire generation. As such, it should go without saying that they are incredible in their roles this time as well. In fact, every actor in this film hits pitch perfect notes on every joke, every line, every stroke. I’d list out the various actors, and their strengths, but some of them feel like spoilers and as a man of my word, I cannot betray your trust. My only personal complaint is the amount of blood and gore in this movie would make a Mortal Kombat fan blush. It was by a wide margin the only thing in the film I thought should be toned down. It was consistently distracting in almost every one of the action scenes to the point that I couldn’t even be sure of what was happening, especially when they really got things going. It made me wish for an “R” rated, light cut of the film. All the language, half the gore. The take away from this should be that the only bad thing about this film was how distracting the gore was. Imagine this horse I just beat to death is an example of how distracting the gore in Ryan & Hugh: BFF4Life was as a whole. Damn, that is a great turn of phrase and critique. Good job me.

I can’t lie to you though. Or maybe I just won’t lie to you. I left the film after this meta-narrative thinking that, while the film was great, it came with a lot of baggage. The fire to this fuel is mostly lit by knowing not just the catalog at Marvel, not just Fox, but the careers of the actors, the artists in the soundtrack, and a never ending myriad of collective popular culture knowledge as well. I can still remember sitting down in the year 2000 to see the first X-Men film in the Fox franchise. It was quaint by today's standards, and while fan service could be found in the film, it wasn’t created to specifically cater to the demands of fans or their knowledge. Its primary focus was to tell the classic X-Men story. Lucky for us, Fox attacked it with a kind of fever no one really expected at the time. Not quite as unique as Tim Burton’s Batman, and not quite as earnest as Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man, but it was grounded without being gritty. It was real. Just before that, Batman & Robin and its 60’s hokey aesthetic had basically closed the door on superhero films for a while, or that was how it seemed. But a slow build was happening adjacent to this with R rated features like Blade, a gorey mess that kept the hinges of that door oiled. Fast forward almost 25ish years and Deadpool & Wolverine turned all these creative successes (and failures) into their showcase for the executives at Marvel. In doing so, they had to throw everything in the entire backlog at us, for us and everyone who worked on those films. They asked fans to light the fire, but in doing so, they ended up having to make a film that relies on people in the future being cultural anthropologists, lighting their own torches as they dive deeper into the dank caves of our popular culture past. I think films should have some amount of presence in the present, but at this point, we are basically asking people in the future to understand an entire lifetime to truly capture the thrust of the film.

And this time tunnel goes both ways. If you are my father’s age, a boomer disconnected with the now, there are a series of synapses that don’t fire. He may know a lot about X-Men, the Marvel Cinematic Universe, the history of mutants, all sorts of nerd culture, but I could see him lost in about every other word out of Ryan’s mouth. He may have been alive, he just wasn’t participating in pop culture beyond his 30’s. He just can’t connect to it. I fear that may be how people perceive this film in the future, and in fact this whole MCU. The MCU as a franchise is an overwhelming excess that rarely touches brilliance across its entire catalog. It's not like it is a new cinematic language either, but rather a recreation of what makes serial comics like those under the Marvel and DC banner so uninviting to newcomers. What I love about films of the past is that they may capture the moment, but not at the cost of the story and not at the cost of the future. It's helpful to know what was happening around the time of films like The Godfather or Apocalypse Now, but the films don’t misfire because of your lack of historical awareness. When Iron Man came out, it was alone. It set a tone for itself and it was completely free to do so. Future generations would better grasp the whole of the film with knowledge of the Iraq, Iran, and Afghanistan wars of its era, but the film doesn’t rely on this knowledge for its story and thus will have a stronger legacy.

That being said, even if it is stuck in the present, all cylinders are firing on this film, even if it's only because I know how the car works. I think it can still run without it, just like starting a car is a simple turn of the key or press of a button, I don’t need to understand how the engine works, but it helps. Ryan and Hugh have completely brought to life Deadpool and Wolverine as they were always intended to be, you’d think they were born to play the roles. I think that here and now, we can call this film a complete creative success, and that is truly set in stone, but I am subtracting a few points in my own cannon simply because I believe films should also preserve their point within the runtime of that single film's arc. They should be able to stand on their own, speaking the human condition without the baggage of complete cultural knowledge. A great film is both universal and timeless. But I can still love a good film. And maybe that’s enough. It's clear that the success of this creative endeavor is shared by the entire team, from the director, the actors, the writers, the camera operators, all the way down to the lowly grips. Maybe that will be clear to new people watching this film in 50 years. Maybe that will ring true across all the baggage, across all the jokes, across all of time. A collective creative success.

****SPOILERS****

The greatest spoiler is that I won’t burden you with any spoilers at all! No, no, I jest. But with a kernel of truth. This film has a never ending slew of celebrity cameos, all playing a few one off jokes, but ultimately, they aren’t really worth talking about in a review because they have very little consequence. The Marvel Universe usually has cameos for the purpose of creating branching paths, but that doesn’t really happen in Deadpool. Not really. It's like an Easter egg hunt where there are hundreds of eggs of all different sizes and colors and it's hard to really tell them apart or make any one of them more important than the other.

So let me share my favorite eggs with you. I really enjoyed the post credit sequence, making the final case for the creative passion that went into Fox's cinematic universe over the years. I really enjoyed seeing Wesley Snipes’ Blade turn the corner and make possibly his last appearance as Blade, with all the original swagger. The riff on Gambit’s accent was fun, and Channing Tattum really hit the mark, but still made you wonder if Gambit really ever stood a chance on the big screen. And finally, seeing most of the original X-Men and X-Men First Class series villains. I think the biggest loss was not seeing Nighcrawler or Mystique. But you can only do so much, and the film acknowledges that. So there we go. Remember to plug yourself like daddy Deadpool likes and thanks for reading!

#Film#Review#Deadpool#Wolverine#Deadpool and Wolverine#Deadpool & Wolverine#Ryan Reynolds#Hugh Jackman#X men#Marvel#MCU

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Beautiful and Exhausted || Final Fantasy XVI

Since the release of Final Fantasy VIII, there has never been any way to tell what a Final Fantasy game would be like. The reason I point to FFVIII in particular is because, had Final Fantasy VII been less popular or an outlier, we could count it as a once in a series event. But with the release of FFVIII, we could see the beginning of a pattern. This would be even more obvious if you looked at the Squaresoft Playstation 1 lineup as a whole; and even more clear if you look at the Fifth console generation in its entirety (which included the Playstation 1 and Nintendo 64). This was the beginning of the third dimensional era of gaming. A place to turn games into a more cinematic affair. A time to change the way we interact with the media of gaming. It produced blockbusters in the way of fever dreams. It paved the path for gaming today. But across generations, we had franchises like Final Fantasy; a franchise that would come to embrace this experimentation as part of their DNA. This alchemy of gaming and storytelling has led to some of the most memorable moments in the history of this hobby. But experimentation has a downside. More often than not there are failures. You can’t create gold from lead; a hard truth we have had to learn as both fans and developers. Some of us take to fool’s gold as if it were the same; it shines the same but lacks the value. This might not be the most glowing introduction for a review, but I want you to know that Final Fantasy XVI was the desire to return to the days of old while maintaining modern standards. It’s a messy affair, this alchemy. The melding of generations of gaming. Final Fantasy XVI caused me to feel a mixture of frustration and admiration. It made me believe the developers had a desire to lead into gold, but just weren't sure what the recipe should be. In the end, it was all placed on a single protagonist’s shoulders.

Everything leading up to the release of the Final Fantasy XVI led me to believe I wouldn’t like it. That it wasn’t a game built for the fans of Final Fantasy, but the fans of a completely different medium, like television’s Game of Thrones or the worlds of The Witcher. And while I have no aversion to the latter and no love for the former, I still couldn’t help but feel immediately displaced by the look, feel, and direction of all the media. A purchase to be made in favor of a completely different medium. While gaming as a whole seems to be escaping me into the hands of another generation, I thought I could find solace in the old guards from my youth. Squaresoft had an air of measured science. Creating and innovating in a way that favored an entire generation of fans while pulling in new ones with their modifications of play. They built an empire that has long since rested on its laurels. And like every empire unhappy with complacency, they are trying to conquer new lands in spite of the cries from their constituency. But, let me be clear, that doesn’t make Final Fantasy XVI a bad game. It doesn’t make it an experiment gone wrong. What it means is that it’s different. It’s a new battle plan finding its legs. What it means is that, as a long time fan, I had a very strong reaction that led to very nuanced feelings.

This was the first Final Fantasy I thought I wouldn’t buy the moment it came out since the release of Final Fantasy VIII on 9/9/99. But like many stans, the demo changed my mind almost immediately. It was fast, sleek, and brutal. It delivered that delicious vertical slice of everything the game had to offer. It knocked me out of my chair by the end of the demo. A mainline Final Fantasy putting a real blade to the neck of our heroes and drawing real blood? The performances were the perfect mix of melodramatic and serious. Theatrical and operatic. Essentially, I was praising Final Fantasy for actually trying to do outloud what it had always done behind the veneer of a PG-13 rating. Like a fish after a lure, I was hooked. The day I finished the demo, I *dun dun dun* PRE-ORDERED THE GAME! I gave into the beast. Though, to be fair, I already mentioned that I have been doing that for years in the case of this series. Anyway, the demo did its job unlike any ever had. And if this one page introduction wasn’t proof of that I have a lot to say, then the next several pages will. Buckle in. We have the story, the gameplay, the presentation, and the impact to discuss.

The biggest selling point of the demo was the bombastic end. Essentially, what struck me most in the vertical slice was the story. Not necessarily any one part of the story either, but the veritable roux of all of its elements. The characters by themselves are not very compelling, neither is the world of Valestha or the countries that carved up its landscape. The Mother Crystals, the magic, the slaves, the townspeople, all of them are spices awash in a story that at first taste goes beyond quenching your thirst or satiating your hunger. It makes you believe that something profound is going to happen, that you are just at the beginning of a story with depth. The story starts as a portrait of one young man, Clive Rosfeild, first son of the duchy's ruler, and head guard to his younger brother Joshua who was born with the generational gift of a god that appears in the family line. The immediate implication of this familial line is that we are going to get a series of history lessons throughout our game that will enrich the decisions around our characters, but ultimately, the story remains focused on a single character, Clive Rosfield. And from the first moments that we get to control Clive as an adult, we spend several hours focused solely on his need for revenge. The world takes a backseat to Clive’s journey through it. Looking at all the previous games in the series, the world was just as much a character in a Final Fantasy game as any of the people in it. Even in Final Fantasy X, in which Tidus is whisked away to a world he knows nothing about, we get to learn everything about the world through his eyes. And on the other hand, in Final Fantasy VIII, all the characters grew up in the world we are exploring, but each of them have their own opinions, come from different places, and give the world a little more depth than it otherwise would have had. But with Clive, a bit of lone wolf, we don’t get to experience this depth, particularly for two reasons. First, it's not that there are no other cast members, there are plenty and they all come from different places and backgrounds. It's more that, because of the nature of the story, all the places they are from are inaccessible, either because it was destroyed or because it will at some point be destroyed in the near future so that when you arrive, it isn’t the same place anymore. Secondly, the characters we play are all aristocrats and very educated about the world around them, and as such, they don't spend time talking about the world around them beyond the direct nature of what they have to do. This means that Clive bears not only the burden of saving the world, but also holding our undivided attention. Unfortunately, he can do the former, but not the latter.

This leads me to our roster of characters, some of whom have come under considerable fire for their lack of emotion, while others are lauded for the breadth of their voice. Clive is wrought with feelings of loss and failure. His woes seem to be endless. And yet, he finds a way to be the kind of hero you can get behind. He is the theater of this story. He is constantly in the depths of tears and pain. He is unlike any other character in the Final Fantasy series, possibly because he has a fantastic voice actor and because he got all of the writer’s attention. That being the case, every other character suffers for it. They are merely there to give depth to Clive. They don’t become anymore than who Clive sees them as. And sadly, because Clive is constantly in the midst of pain and responsibility, he only has a few notes, and no matter how many times they play them, he doesn’t make for a more compelling song on his own. But in the accompaniment of his friends and allies, we get a very passable verse that sounds great, but still doesn’t make up for the lack stories lack of awareness of the history of their surroundings, especially because there is both and in-game historian who plays a background role, and because all of our characters are especially privileged and educated. My gripe is that the story writer’s can’t have it both ways; a huge political story and a very centralized character at the heart of that story if neither in turn recognizes the other. In the end, it doesn’t matter how great Cid was or how good of an independent female protagonist Jill was because they only are there to serve the forward momentum of a single character at the cost of the vibrant world the framing tries and fails to establish at almost every turn.

Now we can zoom out and look at the world of Valisthea and the history surrounding it. At best, it is incredibly confusing. From the moment the game shows you the world map and gives you access to the history, you aren’t entirely sure that its trustworthy because it is in constant conflict with its own language and the world at large. Simply reading through the “Active Time Lore” and speaking with Hipocrates “Tomes”, you are never truly sure if Valsithea is the entire world or if it is a smaller offshoot of the world, like a zoomed in map of Australia. It turns out that this is a little of both. Largely because it doesn’t matter to the story that other places exist, but even the people of Valisthea are not entirely sure anyone has been “overseas” despite some people claiming to hail from there. At points in the game, they gesture to Samurai through sword making, and at other points to ingredients from “the West”. The issue I have with this is that the game wants us to take it seriously. That the world of Valisthea and the people in it have a rich history akin to Game of Thrones, but as soon as you go looking, it fails to provide anything more than a mishmash of incomplete speculation and fan service for the player. One could argue that in a world as fractured as Valisthea, the history would also come up short, but this isn’t entirely framed as the case to the player. We are given knowledge from this Lore Menu that their tomes would never have, made up entirely of our current knowledge and flavored with lore from the game. It was meant to outright explain the reality of the game’s world, to help you frame the actions of the people in it, and explain everything happening around you. However, it fails to make clear things that should be. And as a side note, it contradicts itself at times, saying one thing happened and then saying another. For instance, there is a battle between two nations in which two entries say the other won. It could be flavor, if it had been framed correctly, but I think it was simply an honest mistake.

The more you examine the world of the game, you realize it was meant to be smoke and mirrors for Clive’s journey. The various makeup of each of the nations that make up Valisthea seem deep, and admittedly it is more than nothing, but every other Final Fantasy did a whole lot more with a whole lot less. The governments for each are completely different, but it hardly matters to the story as a whole. None of this does anything to alter the course of Clive or his party or how they handle any situation. No one they deal with has any level of political intrigue that interferes with the story, with the exception of Dion, but it only has to do with Dion and simply leads him to do something completely outlandish that ultimately makes this intrigue completely flaccid. One of the best aspects of this game is that it absolutely shocks you. It throws curveballs that you don’t see coming exactly when they need to. But these curveballs undermine the entire purpose of setting up the foundation of the governments and countries of this world. Even attacking the Mother Crystals, the thrust of this games story, are consistently caught with a lack of meaningful defense or even realistic concern for their wellbeing in a world that both relies on and reveres them. Again, only because the game begs us to take it so seriously do I find this to be such an egregious issue. They set up so many things, only to have Clive basically mow down the world around him without ever considering any other way than knocking down the front door. I hate that the various countries amount to nothing, especially when they could have had something to say about our world or even their own. They are simply Legos for Clivezilla to knock over while we play superheroes vs monsters. It’s simply a shame.

The presentation of the game is meant to be in a state of constant forward motion, but the popularization of chapter based gameplay as of late really makes the world feel less like a place you might role play and more like a classic platformer. By that I mean that the game is a series of stages instead wherein you hold right, interchangeably fighting monsters and listening to dialog, until you reach the end of the stage. While this might work in favor of books and film, this really changes the entire frame of an RPG as we classically know them. This design is taken further once you unlock the Arete Stone. This allows you to repeat any of the main stages of the game, from start to finish, collecting points to try and get a high score. It furthers that the main design of the game was around completing scenarios in tight packages, which could have been fine all on its own, but by calling attention to it, I can’t help but feel taken out of the moment. The landscape never feels like a continuous world because we have to be told to stop and recognize a “new” stage or moment is beginning. I like to escape into the world of Final Fantasy and this format ultimately pulls me out of “the world” and back into “the game” instead of the seamless merging of the two in the classic format. And it would have been one thing if it mentioned chapters at big moments, but it does it at every turn. To put it mildly, it puts a damper on the experience as a whole.

While the framing of the game was not exactly to my liking, the gameplay was a fresh change for the series. A fresh change, but not entirely welcome. It felt like this game deserved a subtitle instead of the mainline marquee of the 16th entry. If they had called this Final Fantasy Valisthea, or Final Fantasy Action in the same way Final Fantasy Tactics was to the point, I think it would have matched the fans tastes a little better. No one wants to order pizza, take a bite, and taste fruit punch. This is a hill I would rather not die on, and while I feel this way, it ultimately would not have changed my feelings on the game as whole, but instead is more of a judgment of the decision makers at SquareEnix. On one hand, it’s great for marketing and ensures a certain number of sales and general interest. On the other hand, you are basically walking into the room and asking for fans' forgiveness. “Everyone, I know this isn’t exactly what you expected, but we promise it will be worth your time. Please give it a chance.” I want to point out that the issue isn’t that the game is completely action focused, but rather that the game is comprised of 40 to 80 hours with an entire cast of characters, and you only get to play a single one. Other RPG’s have taken the action route, but most of them have the sense to offer you access to some of the cast. It would be one thing if they didn’t have any good examples of this, but their own Final Fantasy VII Remake gives you access to play, equip, and customize the entire team, all while giving you a complete action based game. And while Final Fantasy XVI gameplay is fun and has some strengths, it has many competitors that did a better job in the current generation (like God Of War) and several that did it better in generations past.

Where the game really shines, truly surprises, and earns some forgiveness is in the moments where Clive is pitted against the various Dominants of Valisthea. The game is largely broken into three portions. Clive’s quest for dialog. Clive’s battle through monsters. And Clive’s transformation into the kaiju-like god-beast Ifrit, a being they called an Eikon (which I have to point out begrudgingly is pronounced like icon). This final play style creates bombastic scenes of epic proportions. It feels like 3 separate teams were all given completely different instructions on the tone of the game and that no one at any point during the final construction batted an eye when putting it all together. The Eikon battles are so jarringly different from the rest of the game that, like the chapter style, it completely removes you from your immersion in the world. You are shaken from the dark and dour world one team created and into the Godzilla/Tokusatsu, B-Movie of your dreams. It is both entirely welcome and completely incongruent with the rest of the game. At one point in the game, you could swear they forgot that it wasn’t 2008 or that they weren’t making a Sonic the Hedgehog game. And in another moment, you think they were going for Gundam meets Transformers or that Freeza was about to roll onto the scene. This is just another place where the game further deserved a subtitle instead of the titular 16. And while the actual functionality of the battles as an Eikon are simply mirrors of playing as Clive, replacing his sword with claws and firebreath, knowing that these moments are fleeting is a little disappointing. Unlike your battles in the rest of the story, these are clearly numbered. But it is another feature that kept pushing me through the game and a very powerful Phoenix feather in its cap.

As for playing as Clive outside his Eikon form, from the moment you start training as a young upstart knight, it shows promise. It’s simple with the promise of depth. Playing as Clive and zipping around the battlefield feels right. The game grows to give him a myriad of skills that, when used right, allow you to become the god he truly is. I found early on that it is best to cycle through the various control schemes and decide which one fits you best, as it enhances the game as a whole. Growing your skills is limited by the story, unlocking new abilities as you encounter other human-god hybrids called Dominants and taking their power. You begin to look forward to what kind of abilities you will get next. Looking back, it was the most motivating thing, after the story, that motivated me to continue pushing Clive to the end of the game. And while none of them are entirely disappointing, you will be hard pressed to use many abilities beyond the first two trees unlocked. It’s not that the later skills are useless or even hard to use, there are just too many advantages to the first set to bother experimenting with the others. On the bright side, they allow you to completely change out any skills at any time outside of battle by letting you refund the skillpoint necessary to unlock the skills. This gives you complete freedom to try out any combination of skills as long as you have the necessary ability points.

Still, in the moment to moment play of the game, what you come to realize is that it suffers death by a thousand cuts. On the next stop on our autopsy, we get to dissect beyond the good points because every single choice they made beyond those detracts from any enjoyment the game offers. A series of very common, modern tools and shortcuts are completely absent. The first thing is that there is no mini-map. I can understand that this may have been removed in favor of immersion, but because each area ultimately feels like a stage with a very obvious beginning and end, you end up checking your map just to make sure you explored everything. It’s very easy to keep going the “right way” at all times and miss places to explore, treasure chests, or even battles. You essentially can’t get “lost”, which when well balanced, can make RPG’s very fun to explore. At some points the game offers several paths to get to the same endpoint, but you would have no idea if you weren’t checking the map. I must have hit the map button a million times to make very simple checks that the mini-map could have easily solved and kept me playing instead of pausing.

Another immersion choice I imagine was not letting Clive traverse the game at any other speed than a slow, agonizing crawl. You have no ability to choose your run speed, and only get to “run” outside of towns after having held down forward for 7 or so seconds. And if you stop, get ready to wait for the sprint again. You eventually get a Chocobo, but it doesn’t move any faster than Clive’s run. It simply gives you the ability to use a run button. Inside towns, you can only move at a light jog and you can’t at any point use any of your teleportation battle techniques to traverse any faster or just have fun being weird in the town. And yet, this game has giant monster battles and yells fuck at every awkward moment. You do get fast travel, but another weird point of the game is that it recognizes the points (large stones similar to the Arete Stones) are activated because of Clive’s presence, but then the rest of the game acts like what we are doing is not “teleporting”. This means that everyone walks or rides everywhere in Valisthea, including your own party, even though the game recognizes these points. Another very weird choice, as it would have been better to simply ignore it if the game wanted to be “serious” over being “fantasy”. You even have a boatman at one point that I never spoke with unless I was prompted, found in an entire section of your hideout completely unused after you first meet him. It’s a burden to get to know the people living in the hideout because of how large it is and how slow Clive moves, making you want to skip any conversation I would normally have enjoyed having. The dialog is actually a good point of the game for the most part, not exactly in the content of what is said but rather how it is said.

For the most part, the extra conversations feel natural, if not a little too slow. They have weird pauses in their speech, but that isn’t really an issue of the content as much as the delivery. The real sin is that they frame most conversations in this one on one, switch screen between Clive and the target that feels so shamelessly lazy and boring, you are thankful that at least the words themselves aren’t boring. In these moments they pass each other invisible items that make the same sound no matter what it is. And while every item has some small art and very detailed descriptions that mix lore and colloquialisms, it's a real shame that almost every item has no in-world design. The most obvious place you can feel this is absent is in your gear. The only visible gear is Clive’s sword. He can equip a belt and a bracelet, but these are never visible. There is no menu to view your sword as the 3 dimensional object it is without setting Clive up in the perfect position in the Photo Mode. So many RPG’s at this point allow you to view the in-game model in a special menu so that you can really appreciate it. This became a major point that made the game feel so much cheaper than it was meant to. It almost feels like they went out of their way to remove this feature instead of adding it. It would have been minor if there weren’t so many other issues, particularly these kinds of features that are in other games I always felt were minor, but when they are all absent at once, it's very noticeable.

While the pacing of the story is pretty brisk, the disbursement of sidequests is outlandish. Sidequests are a staple of the genre and have increasingly become part of all sorts of games. You would think that a company full of people steeped in the RPG genre would do better in this arena, but this game may rate as one of the worst in both meaningful content and pacing. Most of the quests are not available until the very end of the game, and the ones you play along the way dole out minimal amounts of character content. You do meet and learn more about the characters in the game and the world at large, but none of it feels worthwhile. There are moments where you feel as though you have accomplished something significant, but it makes no difference to the storyline at large. There is no interaction between the quests and main plot, which for a game that is supposed to live in a world of political intrigue, it feels like a completely missed opportunity to deepen the lore. The other facet of the sidequest system are the Hunts. The hunts are largely the standard enemies with extra movesets, hit points, and color changes. They are actually pretty fun for the most part and a fun change on the basic enemy formula. However, the slightly deeper lore and expanded enemies is the only highlight of this whole portion of the game, largely because thats all you really get for doing any of this.

The spoils for quests and hunts are often crafting materials, which already have a limited use. The only person you can equip is Clive, and he can only equip 3 craftable items at a time, and you can’t build accessories. This means that you are constantly getting completely useless materials, that while you can sell, the only thing you can buy are healing items, accessories, or waste on beer and music (which sounds pretty great if this were real life or if it had any effect on Clive and company). The accessories are also largely useless in the grand scheme of the game, as most of them only shorten the rest period of your special moves by minor amount of seconds. You are rarely in need of any special move at any given interval, and simply waiting an extra few seconds for the skill to return is not difficult by any means, especially outside of boss battles. The accessories that increase your stats are also completely invisible. Because of the speed of battle and the general design of the HUD, you can’t really tell how much any stat increases are working in your favor. The HP bar has no numbers visibly attached to it, so when you get hit, you have no real idea how much 50 defense points is really helping, and ultimately it doesn’t really matter anyway. Another staple of RPG’s missing is that Status Effects are almost completely absent in the game, both positive and negative. You can basically up your defense or your attack, but that's about it. Even if they do exist, they must have happened so infrequently, that I hardly found any use for them or was ever hindered by them.

In battle, your only real ally is Torgal, your faithful pup. His abilities are pretty limited and his basic function is to help you continue or finish combos. He also has a heal ability, but it can only heal your most recent set of damage, and by such a small percentage at a time, his heal is largely useless. But not as useless as the rest of the characters feel. You can’t control or request assistance from any other character that works with you throughout the entire game. You don’t have any traditional party aspects. While Jill might be able to freeze enemies, because you can’t control who she is doing it to or when, it’s mere coincidence if it works in your favor. Still, the game shines when you blow away your opponents with your entire arsenal. And maybe in an effort to balance Clive’s overpowered abilities, many of them obstruct the field of battle so completely, that the stronger enemies can still make strikes even though you can’t see them. At times, because of this, the camera is your worst enemy, always focused on Clive’s “sexy little waist” (a line from a completely different review that I can never unread). While your moves continue to destroy the battlefield, the best you can do is dodge around and counter blindly. Clumsy fun is what you might call Final Fantasy XVI’s battle system. It can be easily broken in your favor but that never stops it from being fun.

The backdrop of Valisthea is often a visual treat, but in spurts. Large swaths of the game are simply rock backgrounds or bland terrain. But when you run into ruins or waterfalls, it is quite a sight to behold. Just before XVI came out, I got obsessed with a feature of video games I never thought I would use; Photo Mode. And while Ghostwire: Tokyo was its own special kind of gaming hell, its photo mode was exhaustive. It was like using a real camera and photoshop in a game. I can recall games as recent as Red Dead Redemption 2 have photo modes and graphics so good, they tricked local television stations into thinking they were real photos of their own towns. And this is yet another place that XVI comes in last, with an overly basic photo mode with very minimal options. Hilariously, the camera is not free to move around anything other than Clive, so you have to work really hard to take shots of other people or things. And if you want to remove Torgal or Jill from a shot, tough shit, you can only toggle Clive in and out of pictures, so get ready to maneuver a bit. A quick aside, on the most disappointing aspects to the game is actually one of the most beautiful; the ruins. Throughout the game, ancient societies’ powerful ruins and ships have been hollowed out and used as city centers or bridges or highways. They, at best, get a few lines of dialog explaining them, but never come to fruition beyond that. They are simply pyramids, spectacles hinting at an ancient world, but go nowhere. This might be a little too realistic. The beauty of Final Fantasy and RPG’s is that in most cases, this kind of scenery ends up becoming something other than background information. Another shame because it was not just beautiful, but it looked and sounded interesting. Below you will find an album of every picture I took throughout my time. Seeing it all lined up like that felt like I hadn’t spent 2 months leading Clive through his journey.

As much as I wanted this to be a review, it really turned into a list of grievances. Because the save file doesn’t have an hours played clock, my best guys is what the PS5 recorded as my playtime. I put 88 hours into Final Fantasy XVI, and another 5 or so if you count writing up this article. As I have made clear, Final Fantasy games are an event for me. I look forward to them even if they don’t have a story, setting, or characters that appeal to me. It’s a bit of stockholm syndrome, held hostage by nostalgia. Since the release of Final Fantasy X, I have felt the franchise walk further and further away from me. It made the battles slower and more methodic, added a turn gage, and put a stop to general feeling of exploration. The XIth entry moved online and bloated the experience into a slog with lengthy hours spent leveling up and somewhat trivializing the personal nature of the stories that used to be relegated to a collective cast of characters. In XII, the world of Ivalice brought a broader, impersonal nature to the adventure, giving you deep characters and a wide world, but very little glue keeping all the pieces together. With XIII, we were on rails where there was little strategy in battle, but a bombastic scenery and convoluted story encompassed the cast. The legend of XIV’s epic failure is only encompassed by its meteoric rise from the ashes as one of the best online games still played today, and while it is loved for its story and cast, everyone essentially being the main character in their own right never passed for me. The road trip dramedy of XV and its splintered sales tactics of Anime, Film, and DLC just to keep up with the bland and incoherent story was still blessed with some heartfelt moments between its lead boys. And of all of these games, XVI is the one I have had the hardest time with. There are so many missed opportunities to be a great game, simply by absence of features alone. This game is marked by its absence of not just things that are sacred to Final Fantasy and RPG’s, but by basic gameplay features that would have otherwise elevated and erased this deeply held sentiment expressed before you. This game only treads water on good graces of the old fans and the surprise of new ones. It holds its breath on the talent of its voice cast and how well they express what little they are given. And most of all, makes land on the backs of its grand beast battles which, while tone deaf to the rest of the game, break through the malaise that otherwise would have compromised the game as a whole. Final Fantasy XVI makes land, but only barely. There really is nothing left to say except for, “I forgive you, and I look forward to XVII. Godspeed and Thank You.”

#reviews#gaming#review#Final Fantasy XVI#Final Fantasy 16#Clive#Jill#Torgal#Cid#cidolfus telamon#Ifrit

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

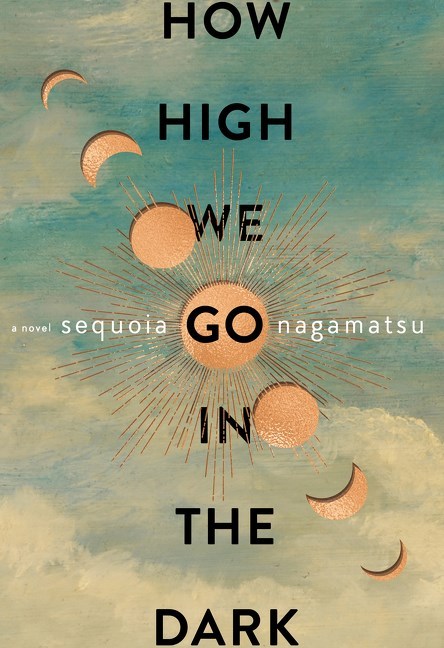

The One That Surprises You || How High We Go In The Dark

I read in spurts. I will do 10 or 15 books in a year for a few years, then none for a few years. I have been in a slump post college. I tend to think of “reading books” as reading Fiction. In the world of Non-Fiction, I mostly read about the American experience, with a focus on Economics and, independent of that, Black and minority lives. Reading Non-Fiction is study, reading fiction is a mixture of all facets of life, of various levels of pleasure and analysis, of the subject and ourselves. When I read Fiction, a film plays in my head. I even read the book as if narrated by a disconnected voice of authority, the characters slowly coming to life as amalgamations of my favorite actors, their voices ranging from classic characters like Sam Malone, Marge Simpson, Darth Vadar, Wednesday Adams, and Spock. The fog in my brain clears and light hits a silver screen, projecting the words of the author turn for turn. That being said, this is my very first book review. I experimented once with music review with The Weeknd’s “Starboy'' and I felt horribly inept at truly understanding what music was trying to accomplish. I fear that this outing might be the same by the end, but in the spirit of the subject of this review, I will tread foriegn ground for, if no one else, myself. “How High We Go In The Dark'' by Sequoia Nagamatsu took hold of me in a way that I have never found in modern literature, and I want to warn you that it isn’t for the faint of heart, but that it is also for people whom’s heart is weakened and needs to grow three sizes.

I am a man that loves nothing more than an introduction. I think context is important, and as such, I want my readers to understand how I came across this literary find. In an effort to help a friend, my group of do gooders started a book club. We decided that each person would submit a book and we would vote on the winner. It should come as no surprise that the person who this was supposed to help never actually won the vote, which is to say, we did our best. Despite that, on our third book this year, the winner ended up not liking their own choice, “Age of Cage: Four Decades of Hollywood Through One Singular Career” by Keith Phillips, and vetoed the book half way, which started a whole new round of voting. In turn, she offered up the subject of our review. Now, I voted for this book knowing only the cover of the book, the author’s name, and its title. I literally judged a book by its cover and little else. I had decided, despite all reason, that my friends were worthy candidates of my entire trust and simply have not read the synopsis to any book I have voted on thus far, which is the “American Way”, for never better and always worse. The exception being in trivial matters like book clubs. Personally, I chose this book because the writer’s name shared reference to a grand tree. Little did I know I would be walking into one of the fastest page turners I had read in years. It may have well read itself.

You can put down your aperitif, it's time for the main course. To continue to write this book’s praises, I should first give you a brief outline. The story revolves around a pandemic that initially attacks the lives of children predominantly, but evolves in waves that ripple out into the entire population of Earth, leading to a change that affects the course of humanity for millenia to come. Uncharacteristically for science fiction, this story is driven entirely by the humans that are actually living (and dying) in this world. The narrative structure is entirely in the perspective of the people experiencing it. It is a first-person perspective of the ingenuity and tenacity of the human spirit during the darkest hours. Reading what I just wrote, I am not sure that I would have read this book knowing what it was about, but I hope you will look past my inability to describe this book from a bird’s eye view any better than this. It's possible I have betrayed the very thing that made this book stand out for me personally, the sheer surprise of it. There is much more in its pages, but it begs to be read to be understood.

I hate to say that I have more concrete examples of what I don’t like about the book than what I do, but to tell you more would be to ruin the experience it provides. Nagamatsu has a style in this book that is so tender, raw, and visceral, you will wonder how someone can speak so universally about the human experience, but be so pointed as to tell a singular experience that is likely completely foreign to the reader. You feel like a spy in a life not your own, but come out the other end calling them your family; reminding you of your mom, dad, uncle, aunt, brother, or sister. Nagamatsu’s strength is in disarming you, alarming you, disturbing you, and comforting you. You will grow by the end of this book, and it's not even “Self-Help”.

Before we get to my general criticisms of the story, I do have one more major praise. I am not Asian or Asian-American, but I really appreciated that many of the characters expressed their disdain when considering living up to stereotypes or their parents expectations. The story focuses on how we pass the torch from generation to generation and how we are often burned by the passing of the baton. I am mixed race, but specifically appear Black (or really any version of Brown and have been mistaken for Egyptian, Iranian, and Puerto Rican in the same day), and living up to both White and Black expectations has always been somewhat of a burden, easier to handle as I have gotten older and more sure of myself, but I still feel pangs of what Nagamatsu’s characters express. To be clear, this isn’t done in a heavy handed way, it’s woven into the story along with all sorts of other aspects to their characters, and it feels done rather deftly.

Now for our dish best served cold, the critique. Truthfully, I have very few bad things to say that aren’t simply personal taste. As I said, the book was easy to swallow and had me coming back for more. However, what had me coming back was something that ultimately went unsatisfied. Chapter after chapter, there is this lingering sense that you are about to stumble into a true adventure, something that will dazzle you; that the characters are one step away from taking on challenges like Indiana Jones or John-Luc Picard. This may be where going into the book blind led me, rapidly lapping up everything in the book, only to be left thirsty afterwards. Is that the mark of a good book? I can only say that its final pages left me without wanting, happy that I found the bottom of the glass. Because at the end, I realized I wasn’t reading the book I always thought it would become, no matter how close to the end I would get. It was like I was under a spell that was removed only when I finished the book. I am not unhappy, but I still wish the book had turned down those adventurous alleys. For instance, the opening chapter shares a very similar tone to John Carpenter’s “The Thing”, and when the chapter was over, and I returned the following day to read the next, I was shocked that we were going a different way. And this continues to happen, over and over, but I still wanted more.

My final thoughts you may want to skip, as I fear it might give away too much, but personally, this did annoy me. Each chapter leads into the next, often indirectly, but leaving behind breadcrumbs for past or future characters to come. It is almost a series of short stories all told in the same universe. However, because the book is largely in first-person, the characters begin chapters using “I” statements and often takes several pages to even learn who is talking, and thus obscures the connective thread from characters in previous chapters until it almost feels silly that you didn’t see it. I wanted the chapter title to simply say who is talking, right beneath it. I just wanted to escape this nagging feeling like I was missing something in plain sight, or that should be in plain sight.

I apologize for being vague, but I do think that this book is best read to be understood. It feels like a monumental feat somehow, like I hadn’t experienced literature in a long time, or at the very least, in my time. All the great books seemed to have come out before I existed, and the ones that have come out since then, maybe I have never fully trusted. In being surprised by “How High We Go In The Dark'', I feel like I can open up to more modern literature, maybe take the practice of “reading books” seriously again. I either have always read for fun or to be moved; reading something superfluous or reading something serious. I haven’t taken Fiction books seriously because the ones I tend to read aren’t trying to move the reader in any obvious way. I have always left that work up to Non-Fiction. Sequoia Nagamatsu may not be the first or the best in this genre or with this type of literature, but he is the first to make me feel this way, and it never would have happened unless I had been willing to be surprised. To go where I hadn’t gone before. It also wouldn’t have happened if he was any less of a writer, so to that end, I would like to thank him. Do yourself a favor, reader, and challenge yourself to this book. It is often sad, heartbreaking, and scary, but more than anything, it is boundlessly hopeful.

#Review#Books#Book Review#How High We Go In The Dark#Sequoia Nagamatsu#Fiction#Pandemic#Sci fi#Science Fiction

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Path to Power || Thoughts on #GitGud Culture

Attaining anything comes with a cost. Time. Effort. Opportunity. Games are no different. We play games because they can take a larger scenario and minimize it, speed it up, and in most cases to further our entertainment purposes, narrate it. We consolidate challenges into bite size playscapes, assign logic and rules, and pass it along to the challenger. Games inherently are assigned stakes, ones that are generally agreed upon by the designer and the player. These stakes can be personal, financial, both, or neither, whatever enhances the player and designers experience. The free form nature of a game's creation is as exciting a place to work in as it is to deliver to another to play in. The interesting distinction is that, much like exchanging foreign currency, the cost of playing a game is completely dependent on what you are willing to spend to play it. And on the other end, the value of that experience isn’t always equal to what you have paid for it. Trading the experience on the open market is also entirely dependent on what you played, how you played it, but not necessarily what it cost you to play it. As a sporting society, we all depend on the rules of play to determine where a challenge belongs in our hierarchy, where we belong amongst each other, and the overall value of your play on the open market. The two questions I will examine are: What is the cost and value of variable difficulty in games? Is a game art, sport, or function?

In accepting the game and the inherent challenge in the designed experience, we enter into a de facto agreement as a player with the designer. This agreement is that at the cost of our time, we will play the game as it was designed. This is assuming of course you aren’t augmenting the game outside of the parameters of the game, which for this discussion, the initial game and any updates released by the designer will be considered the spec for this conversation. The options menu will have a set of parameters to alter the challenge in the way the designer sees fit. In adding a slider that alters the level of difficulty, let's first discuss the cost the designer incurs. In this case, we aren’t really concerned with the time it will take them to add this slider, as when we buy a game, we don’t generally consider the amount of time it takes the designer to make it with respect to the challenge specifically. Keeping that in mind, no matter how many times I have mulled over this, the only cost I can determine is their own artistic vision.

They often say that art isn’t just about the strokes you paint, but also the strokes you don't. Music isn’t just the sounds of the notes, but the silence in between. Basically, outside of the time it would take to implement difficulty changes, it only costs them their art, which most artists would say is everything. If you can’t make the point you want to make the way you want to make it, why even bother? You could argue that if it is important enough, you will compromise, but in the case of art, it is generally understood that the art itself is just as important as the point of the art, if not more so. After all, you could simply explain your point in many other ways. You choose the method of your art because it means something to you. I would rate the cost of this compromise in this case as being high. In this way, both the cost and the value of creating something as you see fit is tied to the creators desire to make that something with or without compromise. Meaning they are essentially equal. Interestingly, as the creation is accepted and lauded by more and more people, the value of the design is increased and thus the cost of altering the design also increases, because the alteration could adversely affect the popularity of the creation, though this is more of a speculative assessment. The creator may not ultimately care if anyone liked their creation, but this just further strengthens the rule, in so much that the cost of making changes stays the same as the value in the case of uncompromising art.

When a designer makes a game with a difficulty slider going in all directions, it implies that the point of the game isn’t specifically in the challenge of completing it, that it was meant to be experienced in a number of ways other than just one, like any other parameter the game has to offer. However, the lack of a difficulty slider doesn’t inherently mean the difficulty was integral to the art of the game either, just that it was designed as part of a whole. A painting usually consists of changing tones of color, but the painting can only be called a painting if you put paint on the canvas. A game can only exist as a game if it has a challenge. In both cases, it doesn’t imply that the change of tone or difficulty have anything to do with the artist's intent, it’s just inherent in the creation of the object as we all understand it. With that in mind, not every perceived element of the design is intentional, nor is every perceived absence, however, there is often a sense we, the consumer player, possess at determining which is which. In the case of #GitGud culture, entry requires an understanding of the designed difficulty, a gatekeeping mechanism meant to define what is and isn’t a challenge worthy of participation in their ranks. It has become understood that Soulslike games are made with the intent of being something the average player would struggle with to master and they are created for the sake of overcoming that struggle. So we can continue with the assumption that the game’s difficulty was intended and thus integral to its artistic merit.

When discussing games, how do we define the difference between art, sports, and function? First, when I say function, I mean a mechanism that holds no artistic merit absent abstract observation, like a hammer and nail. The hammer’s function is to hit the nail so as to fasten something to something else. It performs a function. Video games are full of functions, all of which collaborate to create something more, either in the functions that hold the game together, like code calling classes or rendering art, or in the games design like physics or gravity. By themselves, the game’s physics are simply a function that tethers objects to our reality and maintains the laws of the game’s nature in a three-dimensional environment. The art of physics is in how they are applied, how they either differ or maintain distinction from our own real living space. Function is not art, but applying function can be artistic. The way Mario swings Bowser while grabbing his tail as we spin our joystick is entirely function, but the movement Mario makes and the visual of Bowser flying out of the arena is function colliding with art.

Let’s take for example the game Rocket League and the sport Basketball. Rocket League is a hybrid of cart racing and point based sporting within an arena, most popularly a mixture of RC cars and Soccer. The game is made up of hundreds of artistic assets, filled to the brim with different car designs and decorations to personalize your game avatar. The arenas are largely just big square cages in which your personal car is used to nudge a ball into the goal of the opposing team. Like Basketball, the rules that makeup the game, the game itself, is not art. It is a competitive event that pits individuals against each other to see who has the better players and strategy to succeed at getting the most goals by the end of the time frame. Basketball as a concept, its rules, is the reason that the players are gathered together. Rocket League is the reason players are logging in. The competition is entertainment. And in both cases, while they are not art, it was a mixture of art and function that created them. You could argue that the way you play the game is art. But not the game in and of itself. In Rocket League, when the ball explodes when entering the goal, that was an artistic decision, it was conceived by a designer and directly impacts our perception of the game. The same is true of Mario throwing Bowser. It was designed with intention. Someone had to conceive of these flares and implement it. And while these two games have that in common, the aspect that is missing that ties the game more directly to art is narrative.

Games as an art form is like saying painting is an art form. Humans have the tendency to assign narrative to situations that are devoid of them. It helps us connect with whatever has our attention at the moment. Even the most banal of art, say a picture of a lighthouse in a hotel room, is still largely considered art because it emotes, or in this case, it begs us to emote for it. We participate in it, even if only for a moment, we know it tells a story. Even a painting of three squares or maybe even just a line, when framed and given abstract observation is now art. Mario games, however scanty, have a defined narrative. Man trying to save Princess from Lizard. Even if it never spoke a line of dialog, it would be clear to us that we had a goal that had a layer beyond competition. And it's the intent that we understand this that sets it apart from other games that appear to have narrative, like Pac-Man. Yellow discs eating ghosts isn’t a narrative. We do not know his purpose, its abstract nature begs us to pay attention to getting points, not saving the world. It has no beginning and no end. Some games defy narrative entirely, looking instead to focus on competition. Rocket League for example. It has no clear story, no clear abstraction for us to frame, its focus is to get us to play the game. It doesn’t want to distract us from its purpose as a sport. If you watch any modern sport, like Basketball, the story is on the court, and it's about the game, but the narrative is strung together by the personalities of the players, separate from the actual game itself. Their disposition, skill, and injuries affect their play, but the game itself is unaffected, its rules are unchanging. Its rigid structure and consistency are pure function. It is not art, but we still have a desire to make art out of it.

Narrative is the strongest connective tissue between us and the object when viewed as art. We either create it for ourselves, or it is designed for us. In the case of games with narrative, this would be the final piece of the puzzle wherein I would consider the game art. We discussed how some games have no intention of being viewed as art, they are merely competitive in nature, either against yourself, the computer, or someone else. They are made up of artistic assets, the nature of designing a game is art, the way one plays a game can be art, but without direct narrative intent does a video game really ascend to wanting to be viewed as art, where it transcends its competitive function for something more. Pac-man is not trying to make a point. Gallega is not trying to make a point. They wanted you to play a game, solve their problems, and excel in their design. If the game played itself, we might have assigned narrative to Pac-man’s abstract nature, but only if it was framed in that light. Our input turns the object's artistic abstraction into a function. It transitions from art to function. However, when we play as Solid Snake entering Shadow Moses, the transition between our play and the narrative is happening in tandem. It maintains its state as art while we play. As we complete challenges, its cameras switch and sweep, chosen for both its aesthetic location and to further alleviate or elevate challenge. It is designed with the intent of being art. Games are not inherently art but can be framed as such. Art does not denote quality. If I were to pull a random picture from my phone and show it to you, it would not be art. Unless I told you, this is my art and asked you to contextualize it as such. But even this may not be enough for you to accept that. So maybe I print it and put it on the wall. Suddenly, it must be accepted at the very least as art, though it may not be good art. Art has to have the intent of being art, but it also must adhere to the understanding of art abstraction.