Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

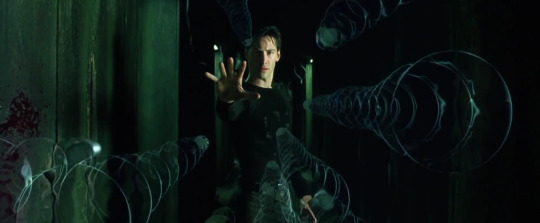

Theme through Exposition (Matrix Reloaded, Revolutions & Resurrections)

This is part 2 of a series looking at the Matrix films. You can read the first part before continuing.

Which brings us to the sequels, Reloaded, and Revolutions. These were made at the same time, and function as two halves of the same story. So I'll look at them as one block. Though in less detail... And I've tagged on a bit about Resurrections at the end to round out the series.

youtube

First, the reviews:

I enjoyed Reloaded and Revolutions a fair bit less than the first film. Of course, there wasn't that gut-punch of a brand new concept to my psyche--that's to be expected. But something about it was qualitatively different to me.

Compared to the small-scale, big-concept of The Matrix... these sequels were all about the big-scale, high-concept. Giant fights (utilising a lot of pure-CGI), in giant places (the dock, and the entire Matrix). While the concepts are less "big," more just... "high."

There was always some philosophy stuff floating around in the Matrix, but the focus was on the Matrix as a concept--rather than discussions on the definition of a word and the abstract impact that definition has on existence itself. Which basically stops the momentum of the story because really nothing is happening.

The bigger scale of the battles and fights is fine by itself. There's a lot of fun sequences in there. But compared to the tighter story-driven fight scenes in the first film, it often felt a bit "and now there's going to be a fight/battle scene." It was easy to get lost regarding why the heroes were doing what they were doing, and what their goal was.

Why is Neo fighting all those Agents if he can just fly away? Why do they need the Key Maker? Where are they trying to get to? What's the stakes?

Interestingly, the film actually comments on that. With the Merovingian telling the heroes they don't know why they are doing things. And the Oracle telling Neo his job isn't to make a choice, but to understand the future choice he's already made. (More on that later.)

Which... okay, that could happen in a story I guess--characters doing what they can but not really knowing what to do. But it means the viewer doesn't understand the motivation of the characters, because the characters don't understand their own motivations... which in turn means it's easy to just not really care about what's going on.

And then the more recent Resurrections. Which, to sum up, is a mess.

youtube

Half Matrix-inspired saturday morning cartoon with a load of colourful one-dimensional characters that do almost nothing (reminded me a lot of some of the Transformers movies in that way). And half meta commentary on the circumstances of making the film, what they thought about the Matrix series and about the suits at Warner Brothers who demanded it be made.

I'm not going to go down the rabbit-hole of the meta stuff about production in this article. You can look into that stuff elsewhere. But watching it with this stuff in mind, and it being so obvious in the subtext (and text) of the movie... it felt like I was watching a mental breakdown as expressed through the medium of film.

But anyway... theme!

The theme of M2 & M3 is Choice... but instead of how "Belief is choice," it's about how "Purpose is choice."

This concept is explored primarily through conversations.

The Oracle tells Neo, "You're not here to make a choice. You're here to understand why you made the choice." [M2 0:45:40] So yes, fate and predestination is real, there is no such thing as real choice. Purpose is a choice already made. Neo should focus on figuring out what his purpose is, not about making free choices.

Which goes against the whole concept of "free your mind" and Neo's free choices being the crux of the whole thing, of being the One in the first place.

Without a lot of work on the viewer's part to untangle the philosophy of it all, it feels very incongruous to the reason they are watching this film... because the loved the first film.

The Merovingian says it is the "why" that has the power. And the gang does not know why they are doing any of this. They are choosing to do what they're told, without understanding why they are choosing to do it. [M2 1:05:22]

Which is totally true. The Oracle said "jump," and they said "how high?"

This is part of why it's not so enjoyable to watch. The viewer doesn't have any idea why they're doing what they're doing either; the characters have no motivation beyond "Oracle told me to do it." That's not an interesting motivation for a character to have.

When they have 3 ships and 3 missions, Morpheus says: "I do not see coincidence, I see providence. I see purpose." [M2 1:41:42]

Though in reality, one of those ships does nothing at all... beyond maybe making the others believe there's purpose and this is the right plan.

There's a lot of chat going on here, interleaved with carrying out the plan. The plan itself isn't that interesting. And we keep cutting back to Morpheus trying to make it all sound grander than it is. There's a lot of bouncing around in time, there's something about the timing of power dropping and when things blow up and when the door disappears and... it's all very confusing. Especially on first-viewing.

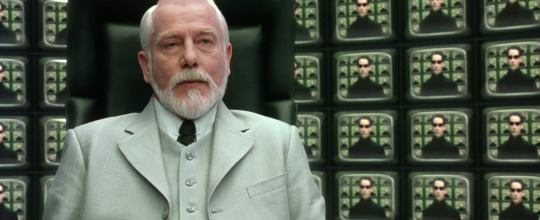

The Architect tells Neo why he exists in the first place, and therefore what his purpose is--why he chose to come here. To decide to let Zion die, make a new Zion with new people from the Matrix, and let the loop keep on looping. [M2 1:54:56]

This is actually quite a cool revelation, but is confusing as all get-out because it's written like an academic paper. It took me a fair bit of studying this scene to figure out what he was actually saying at any point in time.

And it actually turns out none of it was relevant because Neo just decides that's not his purpose, and takes the door no One before him ever took so he could save Trinity. ...Which also doesn't seem to affect anything but the decision in that moment.

The Oracle has changed bodies, because she made a choice. "Since the test of any choice is to make it again, knowing full well what it might cost, I guess I feel pretty good about that choice. Because here I am, at it again." [M3 0:05:38]

This doesn't really fit in with the whole "purpose" idea. It's just more philosophical dialogue.

Morpheus has a crisis of faith, finding out that the prophecy was a lie. He asks the Oracle, "After everything that has happened, how can you expect me to believe you?" Who replies, "I don't. I expect just what I've always expected. For you to make up your own [darn] mind. Believe me or don't." [M3 0:07:00]

She told Neo this in the park, too. And it does fit with M1. Though all the other stuff she told Neo and everything the films are about goes against this idea So... it's just not very cohesive at all, and if you try to figure this stuff out, it comes out as pretty confusing just by itself.

Rama-Kandra speaks to Neo in the station. He's a program who controls recycling at the power plant. "It is my karma. A way of saying 'what I am here to do.' I do not resent my karma. I am grateful for it. Grateful for my wonderful wife, for my beautiful daughter." [M3 0:12:19]

But really his job had nothing to do with those things. He has a purpose. But also some amount of freedom to choose--to have relationships, to create new programs like Sati.

Though programs created for no real reason, like Sati, have no purpose. They exist purely to do whatever they feel like. To make choices. To use their free-will, you could say.

Though the Machines don't like anything to exist that has no purpose. It's just sub-optimal. They want to delete such programs. Which is why Sati is being sent to the Matrix, where such programs can hide from the Machines.

This is cool worldbuilding. Though it's not really explored as part of the story. These facts, and Sati herself, have no effect on what happens. Just more dialogue-only exploration of ideas.

Speaking of whatever he did to the Oracle, Merv says, "Where others see coincidence, I see consequence. Where others see chance, I see cost." What he did to her was business, economics. [M3 0:21:52]

This mirrors what Morpheus said in M2. Though he doesn't see the grandiose purpose and providence, but the mundane consequence and cost--economics in place of fate.

Choice doesn't factor into either of these. Morpheus doesn't believe choice factors in because it's already been decided--similar to how the Oracle thinks. Merv is just cranking the wheel of give and take.

During the finale battle, Smith says "the purpose of life is to end." [M3 1:44:53] Namely by being taken over by him. He aims to take over everything, because he's a virus. And that's a big problem for the Machines.

Thematically, this doesn't really do much. Though it kind of fits into how the fight ends.

Neo gives up and lets Smith take him over. Which allows the Machines to... do... something through Neo I guess? To destroy all of the Smiths? Somehow? [M3 1:52:50]

This could be the choice he didn't understand maybe. Though potentially it could've been the choice he made at the Architect's room--to not create a new Zion, and seemingly allow all of humankind to die.

Apparently he was seeing the door of light in a prophetic dream, though we never saw that so it didn't really have any impact.

Anyway, one of these were this was the choice he didn't understand, that he was destined to make according to the Oracle. Though at the time, it was just pure confusion for the audience.

That's really the problem here, thematically. It was pretty much all talk about the theme, but we saw very little to demonstrate any of it.

There were a lot of "let's sit down and chat" scenes in these films. Technically, the exploration of theme in M1 were also conversations--but those conversations happened because of the story. They were directly related to the story unfolding, they came naturally as a result of what came before. They were direct and relevant.

In M2 & M3, these conversations did not come from what came before. They were not particularly relevant to what was happening. They often meandered and jumped from topic to somewhat unrelated topic--awkwardly setting up aspects that would come into play, but with nothing motivating it being brought up.

One speaker would say something cryptic and the other would understand exactly what they meant and say it--because just a monologue would be too obviously an infodump. Or one speaker would change the subject at random and the other would carry on as if nothing weird just happened.

While there were thematic threads linking to the events--well, pretty much the very final events perhaps--the viewer wasn't in on that. And the conversations were mainly used to worldbuild, exposit at the viewers, talk about philosophical concepts.

Just as in M1, the same concepts were revisited over and over, from different angles. But not in a subtle way that was worked into the story; it felt more like the characters were saying to each other:

ORACLE/ARCHITECT/MERV: Hey, you know how the theme of this movie is fate, or purpose or something? NEO: Yeah? SMITH/MORPHEUS: Isn't it cool? NEO: Uhuh.

The visions didn't really do anything but give the writers an excuse to lead Neo by the nose. We care about Trinity potentially dying, and that piques our interest at the start--that's fine. But it has absolutely no impact on the story whatsoever. She doesn't die, and life carries on.

Or is the idea that the only reason Neo chose not to go along with the "new Zion" door is because he had to save Trinity immediately? If Trinity wasn't falling, he would have left her to die by the Machines instead? I don't buy that, personally. It just doesn't all fit together.

This doesn't mean those chats should all just be ripped out. Imagine if this was done with the finesse of the first film...

For example, we could see the choice Neo would make that was incomprehensible. In the dreams, we see him giving up and dying--something anathema to who he is as the One. We see him taking a door that means the end of all humankind. We see him full-on snogging Persephone.

Maybe just flashes at the start--Neo calmly allowing Smith to attack--to keep some suspense. And as his mind returns to it, the flashes lengthen--we see Smith's black goop ooze over him. Stuff like that.

He's worried. He has self-doubts. He's meant to be this all-powerful thing within the Matrix, this saviour all of Zion has been waiting for. Nothing can stop him. But... is he really going to give up?

We're confused by the dream too, identifying with Neo's response to it. We've got something to think about that we actually care about, that will actually have dramatic impact later on.

Now he has something to talk about, with the dream. Oracle tells him they are choices he will make. That he needs to understand the choice. Now it has meaning, weight. The conversation is now relevant to the story, because the story starts with those visions.

There's the hint of the Machines being this sort of strict dictatorship where if you have no purpose, or become obsolete, you will be killed. And there's an "underground railroad" type of thing going on with the Trainman and the Merovingian.

But that's also purely there to spout theme. It doesn't come into play through the story in any meaningful way.

What if Neo actually helped an escaping program--another thing he couldn't understand the choice to do, perhaps. Running from agents or whatever. Some concrete reason why this is happening more now. Perhaps word of a virus sweeping the Machine City--which turns out to be Smith. We sympathise with "the other side" in this war. If only there was some way for both sides to co-exist. ...Which of course sets up the very end.

There are several indications that the Matrix was intended to be about "the future," a future of humans and machines learning to coexist.

But while it's said at the end of Revolutions that's what happens... I certainly didn't buy it. There's too many questions about how that could possibly work, why the Machines would agree to it--especially as Neo said nothing about it when talking to the nanobot-baby.

That ending felt a lot more like a "blue sky" ending, one where you're not meant to think too hard about it, but just accept the happy ending and move on with your life.

The main issue though is that it wasn't set up in the story. It felt bolted-on. If I was properly prepared by the story for this to be a thing, I could've accepted it as a satisfying and earned conclusion.

And lastly, Resurrections. (sigh)

There's a whole lot going on in this film. A lot of meta themes, a lot of themes about society, random themes thrown in from time to time and never mentioned again...

To save my sanity, I'm just going to focus on the one with the through-line to the Matrix series itself: "You call this a choice?" As in, that's not much of a choice.

Which is linked to the themes and subtext of M1, I think. But with this darker, more twisted tone. Instead of the surface-reading being "Neo is helped by people showing him the truth, and he's going to be the One, yay!" it's "Neo is trapped in a hell no one else can see and there's nothing he can do about it."

"You call this a choice?" and variants of it, is said throughout the film by various characters...

Smith/Morpheus says the choice between a blue pill and a red pill isn't much of a choice. [M4 0:11:22] Bugs agrees, but says it's just an illusion because everyone who is offered the choice is going to pick the red pill. It's offered because the person offering the pills knows what they will pick.

The red pill is there to give the feeling that you are making some sort of choice. But really, as the Oracle put it in M2, "you've already made the choice." In M1, Neo had "already made the choice" to escape the Matrix, by seeking out Morpheus in the first place.

...And then after he was freed, Neo was taught what the Matrix actually is, and so "understood the choice." That's why he went to Morpheus; to understand his "choice" or motivation to "exit" the world. It's a little mind-bendy, but if you squint it sorta works.

Later, Neo, in Thomas-form, is told by Smith, in Boss-form (yeah I knew this was going to be confusing)... that Warner Brothers has offered the choice of make the sequel or watch them make it. [M4 0:19:43] Thomas doesn't want to lose control over something he's worked so hard to make, so they must choose to make that sequel.

This parallels the apparent situation Warner Brothers put the Wachowskis in regarding this movie, in fact. I have no idea how this whole thing made it into Resurrections, to be honest. But there' a lot of meta nods about this in the film.

Neo is locked up by old-curmudgeon-Niobe for reasons, and Morph (what I like to call the slightly odd cartoon-character version of Morpheus in this movie) talks about breaking out.

MORPH: Well, I could tell you that they're standing by, waiting for you to make the choice to remain meekly incarcerated... or bust the [heck] out of here and go and find Trinity. But that ain't a choice.

Which is a little tonally different, but if you're going to the trouble of using very similar phrasing throughout the script, then any instance of it is definitely on purpose.

Morph is telling Neo he has to bust out and save Trinity. Neo has kind of regressed. Both in the fact he's back stuck in the Matrix at the start... but also he's not making any decisions in this film, pretty much. He's just along for the ride.

Which is a shame, considering how far he'd come in M1.

Anyway, they run, do some fighting, and Neo chats to Trinity but comes back empty-handed. Back in the ship, Bugs gets a call from the german guy.

SHEPERD: Check your long-range scans. Squids are combing this area. ... You can stay here and die, or come back and face a court-martial. MORPH: And you call that a choice?

They're not going to choose death. So they must go back and get told off my Granny Niobe.

They go back again. (There's a lot of running back and forth between IO and the Matrix in this film isn't there? Seems pretty redundant.) And for no apparent reason Niobe decides to help them get Trinity out this time.

Sati from M3, now a grown up program, talks with Niobe and Neo. Admits that she knew Neo and Trinity were out there somewhere.

NIOBE: I'm sorry, you knew what happened to him? You knew that he and Trinity both were alive... and you didn't tell me? SATI: There were times I doubted my decision, Niobe. But I/O needed you. The city needed to be built, for your people as well as mine. If I would have told you everything, you would have had a very difficult choice to make. NIOBE: My friends let me make my own choices.

Again, the choice was made for her. She wasn't even offered a fake choice in this case.

In Resurrections, this is actually a step up from M2 & 3. The film has a lot of flaws, but there are no sit-down chats about what choice is as a concept, and what it means to have no choice.

The way the theme--or this theme at least--was written into the story worked just fine in Resurrections. It does make it clear what the theme is, by repeating it with similar phrasing each time. But at least it all fits with the story being told.

(The story being told, I didn't find to be that compelling for many other reasons. But let's not get side-tracked...)

In Reloaded and Revolutions, it was just too high-falutin and wordy. Too much philosophy-major, not enough writing-major (or something). I, and others I'm sure, got a bit bored during the wordy parts... but not because it wasn't 100% action, but because the conversations weren't connecting to the story and therefore we had no reason to be interested.

And the way the theme was used in the story--Neo searching for motivation--left the other parts of the story lacking. Because they literally had no motivation most of the time for Neo's storyline.

But I think the original, The Matrix, really is a shining example of how theme works.

It's not in your face. Could even be that the writers weren't thinking that hard about themes, and they just wrote the story as they saw it... and my analysis of it is just me making connections anyway. But if they did come up with the theme they wanted to explore and then build the story around it, they did such an amazing job that it seemed effortless!

On first viewing the theme went unnoticed to me. Even by the 20th viewing, I knew it was about choice in some abstract way--where Neo essentially "chose" for the bullets to stop, chose to live, chose to save Morpheus, etc. But analysing what's really going on, what's true and untrue, the undercurrent of manipulation--even if used for good--etc... really let me see the depths of the themes here.

As a side-note, just for me, there's a repeating motif the Wachowskis seem to like making in each sequel, which also rubbed me up the wrong way. I won't go in depth now, but progress just kept on being reset over and over again. Power creep and "oh look shiny new thing" slid the world around over time, making it all feel less solid... And worse, those who were really into the worldbuilding were let down by such changes, and by the writers ignoring what was set up in the previous stories, instead of being rewarded for their interest. Ugh.

Anyway... that's enough from me. Maybe I'll speak more on this series. There's a lot to talk about. Or maybe I'll move on to something else to learn from next!

0 notes

Text

Theme through Story (The Matrix)

This is another review/writing article, this time based on the Matrix series, by the Wachowskis. (Stay tuned for the second part.)

The Matrix has always been a favourite movie of mine. When I first saw it, it really blew my mind! Just the core idea of the world not being what you thought it was, the trippy, all-encompassing surreality of it all was super engaging to me as a kid.

youtube

Great effects, some kung-fu, some explosions... great fun.

It was small-scale, big-concept. It's all about a small group, fighting for survival against just 1 - 3 agents, that looked cool with bullet-time and all that. And the idea of living in a simulation and not realising it brought it this weight, and brain-melting quality in the background of the whole thing.

Now... with my review out of the way, the article will begin.

In this two-part series I'm going to go deeper into the themes of each movie, and how they are expressed through the writing. The themes I'm particularly zooming in on are all closely linked between films, so it's a great opportunity to compare different ways of expressing the same (or at least comparable) theme.

scroll down to find out how deep the rabbit hole really goes ���

Bear in mind, this is written for people familiar with the source material--the "Matrices." If you've not watched them, this will spoil all sorts of things with no warning. And what's more, you'll probably not understand what I'm talking about in the first place.

Films are sometimes referred to by the shorthand: M1: The Matrix, M2: Reloaded, M3: Revolutions, M4: Resurrections.

I'll also leave time codes like this [M1 1:20:34] so you can find the clips yourself. I would embed them as youtube videos, but I'm pretty sure they'd be taken down in a heartbeat.

I'll skip to the end and say, the theme is "choice." Choice as a concept runs through all 4 movies, and is explored from different angles, in different ways in each.

EDIT: After thinking about this more, the theme is "manipulation." That's what's happening in each of the scenes I discuss, choice being just one part. But these situations on the whole are manipulations between characters.

What I'm going to delve into is, how the theme is written into the stories themselves, and how that affects the viewing experience.

Everything here is from my subjective opinion. Yours may differ. I hope that you can learn about "theme" from this analysis either way.

The first scene to look at is... Neo's boss tells him off about being late. Bear with me, you'll see why soon. [M1 0:12:04]

BOSS: You have a problem with authority, Mr. Anderson. You believe that you are special, that somehow the rules do not apply to you. Obviously you are mistaken. ... The time has come to make a choice, Mr. Anderson. Either you choose to be at your desk on time from this day forth... or you choose to find yourself another job. Do I make myself clear?

This is not a real choice. The boss doesn't expect Neo to think about it and choose between these options. He is given the choices, with the expectation that only one of them will inevitably be selected.

The framing of the choices is given by the "truths" that preceded them. As if saying, "Given that you're not special and the rules apply to you"... these are your options, but we all know which you should go with.

If believes those "truths," he has no choice but to go with that first option.

Now, this scene doesn't really do much, on the face of it. It establishes the boss's office, and the window washers' platform, both of which come back in the next scene.

But nothing really happens. You could say you should just cut this scene, or else spice it up to make it actually interesting. But that seemingly mundane, unimportant conversation is setting up something very important theme-wise.

Consider the pattern:

He is told about himself. "You believe that you are special, that somehow the rules do not apply to you."

He is told what is real or true. "Obviously you are mistaken." ...As in, the reality is you are not special and the rules do apply to you. Or perhaps, no one is special, the rules apply to everyone.

He is given a choice to make. A) "be at your desk on time," or B) "find another job."

He makes a decision. "Yes Mr. Rhinehart, perfectly clear."

This time around, Neo accepts what he is told and makes the choice they want him to make.

And that is how his character arc is tracked--we see how he responds to these "manipulations" and "choices." How free is his mind from relying on what others say is true, and therefore how capable he is to make his own choices.

In the first film, this same situation comes up over and over again. And it becomes so clear once you know what you're looking for.

Later he is spoken to by Agent Smith in the interrogation room. [M1 0:17:00]

You are a program writer for a respectable software company. You go by the hacker alias "Neo." You wish to do the right thing. You are interested in the future.

Reality: We need your cooperation in bringing a known terrorist to justice. The meek programmer life has a future, the hacker life does not.

Choice: The choice is implicit--which life has a future? The programmer, who helps us, and gets his slate wiped clean. Or the hacker who's locked away for life.

Decision: How about I give you the finger, and you give me my phone call. He chooses the "hacker" life, and imprisonment.

Smith presents those truths, because if Neo believes them he will choose to help them. It's set up to manipulate Neo into effectively doing as he's told. But, as his boss said, he does have a problem with authority.

Neo rejects Smith's truths, and rebelliously chooses to not help the Agents. He's disbelieving what's presented to him in this case, but the choice is still a passive one. He accepts the inevitable, that he's going to jail, and simply wants his right to a phone call.

There's only really one time where Neo expresses his own beliefs. [M1 0:26:47]

MORPHEUS: Do you believe in fate, Neo? ... NEO: No. ... Because I don't like the idea that I'm not in control of my life.

While meekly put, Neo believes--or perhaps wants to believe--that he is in control of his own life.

This is how he rejected the belief from Smith that it was inevitable that he'd give up the hacker life and embrace the programmer life. Because he's in control of his own life.

This core belief of his own is key to the movie.

In that same scene, though, Morpheus pulls the same trick as Neo's boss and Agent Smith does.

You feel like Alice tumbling down the rabbit-hole. You accept what you see because you are expecting to wake up. Reality: you are a slave, in a prison you cannot smell or taste or touch. Take the red pill and I will show you the truth. Choice: Blue pill, or red pill?

Blue pills? Red pills? It's so abstract as to have no meaning, and Morpheus doesn't really inform him to be able to knowingly make this decision in the first place. What Neo is really doing is choosing between believing Morpheus (only symbolised by taking the red pill) or not believing him (symbolised by taking the blue pill).

That's the real choice that Neo is making in all these interactions... whether he believes what he is told, or not. And looking at it from the perspective of choice...

"Believing" can be defined as "choosing to know."

People an believe in things that are proven or unproven, true or false. But they choose that it is true, and live their lives accordingly.

Neo doesn't believe in fate, not because he knows fate isn't real. But because he doesn't like the idea of fate--that he has no control over his life. He chose to know--he believes--that fate is not real.

Of course, here, the fact he'd been searching for Morpheus for who knows how long, and has gone through all the rigamarole to even get to speak to him in the first place... means he believes in Morpheus pretty implicitly at this point.

So this choice is more like a formality. A performance, where Neo pretends he knows what Morpheus is talking about, and goes through the motions of pretending to make the informed choice of taking the red pill.

This is touched on in Resurrections when Bugs speaks of her "pills" offer. "The choice is an illusion. You already know what you have to do." [M4 0:11:22]

You could look at it more like a placebo, a way of preparing his mind to be extracted and accept what is happening without imploding--because he "chose" it to happen in some way. A form of consent, while not really understanding what he is consenting to.

In the dojo, "Morpheus is fighting Neo!" Morpheus tells Neo, "You are faster than this. Don't think you are. Know you are." Reality: "I'm trying to free your mind, Neo." Speed has nothing to do with muscles, in the simulation. [M1 0:52:44]

As they fight, Neo starts to believe that. Starts to "know" he's faster than he thinks.

As Morpheus says at the jump, he is teaching Neo to "let go of fear, doubt, and disbelief." That is how to "free your mind": to believe, separate from anything your senses are telling you, beyond any evidence proving it.

That's his view, anyway. And while it's true to an extent, it's not the full picture.

This situation is made clear with a line from Morpheus in the fight.

MORPHEUS: I can only show you the door. You're the one that has to walk through it.

There's the choice. The only real choice that Neo is presented with again and again.

Morpheus shows him a truth to believe. No one can make someone else believe something by force. Only Neo can choose to believe. Choose to "walk through that door," and choose what options to take as if "knowing" it to be true.

And that is what happens over and over. Doors Neo can take, shown by people who want him to take them.

In Reloaded, the Oracle also shows him to a door--the door of light. Or at least sends him towards it. [M2 0:49:31] And the film is about how Neo gets there, and goes through that door. On the other side, the Architect offers him 2 more doors. [M2 1:56:36] The One always chooses a particular door, so surely Neo will as well? This is meant to just be a formality, like the pills.

Later the Oracle pulls the same maneuver. "You already know what I'm going to tell you." "I'm not the one." Reality: Morpheus or Neo will die. The choice is up to Neo. [M1 1:15:06]

Neo believes the Oracle. Why? Because really she didn't tell him if he was the One or not. She let him decide in that moment. And confirmed whatever he said. So of course he believes her; she only said he was right in whatever he already believes.

And he thinks he's in control of his own life, which she encourages too.

Later, when Morpheus is going to die, he decides Morpheus will live, accepting that Neo himself will die in his place somehow--just as the Oracle said. [M1 1:34:10]

It's funny, the Oracle said to Neo "You don't believe in any of this fate crap. You're in control of your own life, remember?" [M1 1:16:31] But in fact, he's really taken control of his own life because he believes in the "fate crap" she told him. (Stay tuned.)

From here on, Neo is on his own. From what he believes about himself and reality, he considers his own choices, and makes his own mind up on what to do.

Neo is not the One. Reality: Morpheus is going to be killed by pulling the plug, sacrificing himself for Neo because he believes Neo is the One. For the first time he really believes he does have a choice. He believes he can simply choose to save Morpheus and he will do so. This allows him to act, to take proactive action to make what he wants to happen, happen.

Later he sees Trinity go down in the helicopter, knowing she will die if he does nothing. But, believing he has a choice to remove the tether and save himself, or hold on and hope to save her... he decides to save her. [M1 1:50:40]

She chooses to trust in Neo in that moment too, which is part of how she is tied up in him becoming the One.

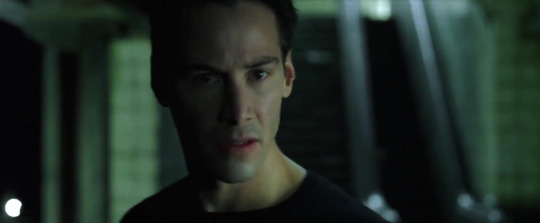

In the subway station, he starts to believe, to know he is the One. He can choose between running from and agent like he's meant to, or fighting. He decides to believe he is the One, and acts accordingly: he stands and fights. [M1 1:54:22]

This rejects Cypher's suggestion that it doesn't matter who you are, you do what they do... "Run! Run your ass off."

Smith tries to manipulate him again on the tracks. He always calls him "Mr. Anderson," telling him over and over that he's just a regular guy who pays his taxes. Reality: "That is the sound of your inevitability. That is the sound of your death." Thomas Anderson has no choice. No one can change the inevitable. [M1 1:57:42]

Neo can choose to accept the inevitable, choose to believe what Smith is saying... or choose that it's not going to happen. He decides with the line: "My name is Neo," rejecting his meek programmer self that goes along with what the world says is true. He hops out the way, Smith is run over. For the first time that anyone knows, someone has beaten an Agent!

And why? Because Neo chose to. Despite the inevitability. Despite what he's been told is true or untrue. He's beyond that now.

Like the Oracle says, "No one can tell you you're in love, you just know it. Balls to bones." [M1 1:14:14] Morpheus can tell Neo he's the One all day until he's blue in the face and it won't do any good. Neo has to just know it, to believe it, independent of any kind of argument or evidence.

"Know thyself." [M1 1:13:54] Believe whatever you want to believe about yourself. Choose to know something is true about yourself.

And now he does.

He knows he needs to exit so the Sentinels don't destroy the ship. This time he chooses to run. [M1 1:58:31]

In the hallway, Neo knows there's way too many bullets coming his way to dodge. Do they hit? He decides they don't with a simple, "No." [M1 2:04:51]

Through all the significant events of the movie, Choice is worked in again and again and again. Neo is told what to believe and given false choices to test whether he believes the "beliefs"truths" or not.

Until he "frees his mind" of what is apparently true, and even what people tell him is true. And makes his mind up, ignoring reality entirely, and essentially deciding what is true.

As Morpheus says, "Your mind makes it real." [M1 0:55:22] Only with Neo, with the One, with someone who has decided that they control what the Matrix does or does not do... it goes beyond the apparent damage to his own body. His mind makes "it" real in the Matrix. "It" being... whatever he chooses is real. He has the ability to "remake the Matrix as he sees fit." [M1 0:45:12] Because he's freed his mind to this superlative degree.

He was dead. That's reality. He--or perhaps Trinity--decided to ignore that and chose to believe he couldn't die. He would not survive three agents firing a ton of bullets at him at once. That's reality. He ignored that reality and choose to believe the bullets would not reach him.

But more than that, the other characters also interact with the theme--in a way that all feeds into the main story line of Neo becoming the One.

Morpheus chooses to know that Neo is the One. Which puts the idea in Neo's head that when he's ready, he won't have to dodge bullets.

Trinity chooses to love Neo, which somehow helps Neo believe. And her kiss saved him, brought him to life, and sort of locked in the fact that he is the One.

Cypher chooses the Matrix as a better way to live. Which is how the situation was set up for Morpheus to need saving, and for Neo to have a choice to make in the first place.

Smith loves "inevitability," where no choice can have any impact. Which gave Neo a clear thing to reject. He chose that he did have a choice. Which is kind of what encompasses "The One" as a concept.

Which brings us to the Oracle.

Did you notice that what the Oracle said was not true? Neither Morpheus nor Neo died. And Neo was the One. It turns out that she's not telling their futures in the first place.

As Morpheus says after Neo saves Trinity: "She told you exactly want you needed to hear, that's all." [M1 1:51:53] Really what she is doing is the same thing everyone is doing to Neo. She tells people what to believe. Why? So that they make certain choices.

All she needs for this to work is for them to believe what she tells them. And they do because she's "The Oracle." I man... she's called "The Oracle," so she must be right... right?

Morpheus goes on to say... "There is a difference between knowing a path, and walking a path." Those that see the Oracle:

Come away thinking they've been told what their path is. They think they "know the path."

Believing that causes them to behave in accordance with that belief. Moves them to make certain choices they wouldn't have made before.

Those choices naturally lead them to "walk the path" the Oracle wants them to walk down.

It's pure manipulation. Just like the Matrix. Just like most of the characters in this film.

Most of the things people believe in this film simply are not true. Many are false. Some are unproven. But they are believed anyway, and pushed onto Neo to believe them as well.

These "truths," these "beliefs"... they don't free his mind. He still cannot see for himself what is true, he needs someone or something outside of himself--Morpheus, the Oracle, electrical signals piped into his brain--to tell him what reality is.

Looked at a certain way, it's a "prison for his mind" he cannot perceive. People tell him what is true, to make it more inevitable he will make certain choices.

But Neo does get onto the path of eventually becoming the One because of what the Oracle has gotten various people to believe--her manipulations worked.

Finally though, he becomes the One by choosing for himself to be the One. Seeing his own reality, seeing the code around him. Choosing for bullets to stop. Choosing to live. Choosing to fly into Agent Smith, and choosing for Agent Smith to flippin' explode from the inside!

His mind is finally free... of believing what anyone tells him, of relying on others to tell him what is true and what is false, of making choices based on what others decide he should do.

The Matrix is dripping with theme. And there's more to discover along these lines if you look hard enough in just this one film!

But does not beat you round the head with it. At no point is a character just talking about the concept of "Choice" and "Belief" what it all means. It's all-story, all-the-time! And only when you stop and think about it, does it really become clear.

To me, that's the ideal way of exploring theme in a film. Not through exposition, but between the lines of the events of the story itself.

Which brings us to Matrix: RE. (Reloaded, Revolutions, and Resurrections.) Continue reading about the themes of the Matrix.

#The Matrix#the wachowskis#Choice#Belief#Theme#kung-fu#action#sci-fi#mind-bending#cerebral#explosions#bullet-time

1 note

·

View note

Text

How to Satisfy Mystery (Severance, Season 1)

For a little while now, I've been planning on writing in-depth reviews of media. Talking about how the show or movie was written, and what effect that has on a viewer so that we can learn from it as writers.

This aspect works the same regardless of the medium--TV, movie, manga, script, or novel. If there's writing involved, that translates to a reader's (or viewer's) response through the same mechanisms. The "text"--the final form of what happens in the story--gives us a certain experience.

So, hot off the heels of watching season 1 of Severance for the first time, I wanted to give a review.

youtube

First, the spoiler-free version:

The show is intriguing from the start. Are they going to escape? What's really going on? How are their selves going to clash, or otherwise affect each other?

The episodes are well written, and well directed. The core "mechanic" is explored in interesting ways each episode. There's a few twists, but mainly it's focused on the quirks of how the world works for them, and how Severance affects their lives.

The suspense rises to a fever pitch, crescendoing to great heights in the final episode of the season... and then it stops. The season ends on quite a dramatic moment for all our protagonists.

The thing is, that dramatic moment does not satisfy any of the questions raised. The tension that's been building over 9 hours does not get released. So it did not give me any satisfaction by getting to the end of the season.

We are not left wondering "What will happen next?" We're left wondering "What will happen... now? What even did happen? This scene that the whole show was ramping up to... what was it ramping up to?"

It ramped up to whatever happens right after the end of the season. Not what happened at the end of the season. So... nothing happened? It built to nothing?!

And that's my review of Severance, Season 1. But the article doesn't stop here. I'm going to spoil the whole thing, and talk about how the "text" of the show got this reaction out of me. And discuss what we can learn from it.

This is an all-spoilers, no-context kind of article. If you haven't seen the show, this article will both spoil the whole thing and not make much sense. But if you have seen it, it will give you a look into how the writing affects viewers (at least one viewer, anyway), and you can learn some things along the way.

[MAJOR SPOILERS AHEAD]

We start with Helly, a female protagonist who doesn't understand the world of Lumon. Because she can't remember anything. As far as she knows, nothing has happened in her life up to this moment. She doesn't know who she is, or what she is doing here... all she knows is she wants out!

This does a number of things:

1) We're in the same shoes. We don't know what's going on, just as she doesn't know what's going on. The viewer identifies with her. So they care about her story.

Interestingly, she is not the equivalent of the "viewpoint" or "main" character of this story, Mark is. But she still serves as a stand-in for the viewer, someone who needs to learn about this place, and so the viewer can listen in and learn with her.

Through Helly, a mystery is presented: Where is she? Why? What is this place?

So, we have a lack of understanding instilled in the viewer... you could call it confusion. That's what mystery is, for the viewer--seeing something they cannot understand.

The reason any mystery is compelling is not the feeling of confusion. Confusion is easy. Put in random words that mean nothing and you've confused the reader. You can keep throwing random things that mean nothing in there, and never answer it, and keep that confusion rolling as long you want. Good job. They've stopped reading.

It is the expectation of revelation that draws in people. Of finding out where she is, why she's there, and what this place actually is.

A mystery is not a story. A story is made when the mystery is solved.

This thread is developed over the season using various arcs.

Helly is taught how to do her job, which at least appears to be wholly pointless busywork--though this is left open to interpretation. It also seems the management do need their quotas to be met for some reason.

Optics & Design is another department who seem to do equally useless busywork. Ideas of a war between them are stoked by management--though it's indicated that this is to manipulate them and keep them apart.

There are maze-like corridors for no good reason, beyond perhaps making it more difficult for the Severed employees to move around freely.

Punishment comes in the form of the Break Room, where lines are repeated until an observer decides they are genuinely sorry. Likely some level of brainwashing, or "recalibration" going on here.

There's a "Testing Floor." Nothing more to that so far, but the corridor that leads to the elevator for the Testing Floor looks scary, so... there's that.

Goats. There are baby goats. They're not ready yet. Goats.

Each time a new little thing is added to the mystery, it intrigues us more. Why? Because again, we have the assumption that there is an explanation, an answer that makes all of these disparate elements make sense. There is more riding on that revelation. More and more we think "How are they going to pull this off?!"

2) Also she wants out, which is totally understandable. She woke up laying on a conference table--a bizarre situation that grabs your attention from the start. And she is unable to leave. The viewer sympathises with her. They can imagine feeling the same way in that situation. They want her to escape just as much as she does.

While the mystery of what Lumon really is runs in the background... Escape is the main driving force of the show scene to scene.

Helly wants to quit, on her first day, when she finds out that her job is just nonsense. She sends a request to her Outy/original self to resign. This is denied in a way that puts Outys as real people and Innys as very separate but lesser beings entirely.

She tries to get revenge on her Outy self by having her wake up hanging in the elevator, which fails. This is where she gets the Break Room treatment, if memory serves.

She never gives up, but plays along for now.

In the meantime, the others don't want to escape. Dyllan enjoys his work. Irving is effectively a zealous follower of Kier--the founder of Lumon. And Mark is just chill and unbothered. And if anything, enjoying his new role as manager of their little team.

Right near the start, the old manager has left. And meets with Mark on the outside. He's even scaped the Severance, reintegrating his Inny and Outy memories--but with complications.

This is what starts Outy Mark on the path to learn more, and perhaps leave Lumon entirely.

Between those characters and situations, we have more questions presented and explored over the season. Why escape? Should we escape? What do we risk if we fail to escape?

People reason about why to stay, why to go. They talk about the obstacles in the way of escape. New things are discovered about how it might be possible. Attempts are made and fail in various ways.

Petey is someone who... has escaped? In some way? Maybe? Only Outy Mark knows about this, but it dangles that carrot in front of the viewer in yet another way.

This isn't a mystery based on not understanding what we've seen, but a different kind of thread. A... geographical thread? They want to be somewhere else (or they don't want to be here at any rate). And the arc is about how they try to do that and if they make it to the other place.

It's engaging because we want to know what happens next. So we keep watching to find out what happens next.

All in all, great stuff! We get new terms we don't understand, which is fun and mysterious, and then makes us feel smart when we learn what they mean. We become "in on it." These act as tiny little mysteries that are solved easily.

We're presented with new ways of seeing the core mechanic of the show--Severance itself. Is it slavery? Are Outys bad people? Why does Lumon do this? What was the true goal of the founder and his descendants? Which keeps us engaged and intrigued with the idea.

We have drama between Innys and management, and between Mark and... just his own life stuff which is affected by Severance in different ways.

The show stays focused on the core concept. It doesn't lull into just straight drama for too long, and what drama is there is humorous and enjoyable anyway. Severance affects everything, every scene. There's not really any fluff where we just have a scene that writers write to fill out some time in an episode.

And then we come the ending, the last episode of the season, the finale.

They eventually cook up a plan to switch themselves--three of them at least--into Inny mode, while their bodies are on the outside. Not so they can learn about themselves, but to find someone and tell them what is going on inside Lumon. About the hell it is for the Innys, and the weird goings on.

They all agree to focus on their mission. No wandering about or checking out their Outy lives because it's interesting. They need to focus and get the word out.

Inside, Dyllan does the computer things. As he does that, we get some establishing of what the Outys are up to. This builds tension. Particularly with Mark, at the reading party, where we find out Cobel is attending in her "nice old lady" form.

We're thinking, "When are they going to wake up? What's going to happen? Will anyone notice?" The suspense is handled really well.

One thing I'd say is, he has to not just turn a switch. Not just turn 2 switches that are an awkward distance apart. But keep them on. Which in-world sorta seems like a weird design choice on the part of Lumon if they want to be able to turn an Inny on for a while, but also they're not that far apart for an average-sized guy to turn them both anyway, as far as I could see.

(Dyllan is a shorter man, which adds to the tension of this situation as he strains to reach between the switches. If Irving had this role, it would've been a piece of cake, pretty sure.)

I did think, though, that such an enterprising man as Dyllan would've grabbed a pencil, a stick... something to cram into one or both of the switches to make the whole thing easier.

Though he did hold out until one of the management, the main hands-on antagonist, rugby-tackled him to the ground and the switches turned off at the end. So in theory the switches would've turned off at that point either way.

It did feel a bit contrived, but you've got to have something going on with Dylan, right? And it does make the other scenes on the outside that much more tense. So fair enough.

Meanwhile, what does Irving do? He checks out his own life for a while--exactly what they agreed not to do. 🤦 He finds out his dad was in the navy. 🤷 He finds out that Outy Irving has been looking into the Severed employees for some reason. Okay. And he sees he's been painting the corridor to the Testing Floor elevator--which we already knew.

(I think they could have held the painting revelation to this moment, and it would've had much more impact. Though they probably wanted that little reveal where they had it, to keep us going through the quieter episodes.)

Anyway, he decides to go find Burt. Knocks on his door. Then Inny Irving is turned off. That's the only thing that happens. He knocks on a door. Which is to say... nothing happens at all.

What does Helly do? She's at a gala where Outty Helly is the star. She's going to give her story of becoming Severed and how great it is, as marketing for the company and the process.

She meets her father, CEO of the company--effectively the big-bad of the show. This is a great revelation, and really pushes that "Innys and Outys are two completely separate people who want different things" concept they developed through the season. Good job!

The man speaks in this odd creepy way. Almost distorted like through a machine? And he mentions his "Revolving" is soon.

I'd like to pause here, to do a bit of theory-crafting... "Severance" is step 1: literally sever the host's mind from their body. Grow the Inny, cleanse it of Tempers (perhaps this is what MDR does) and develop the Qualities through the rules and lore of the company. Perhaps this is the reason for the almost religious indoctrination measures Lumon puts on within the Severed floor. (The Inny is like a larvae growing inside their body that will eventually replace them--by the original never being woken up again--hinted at in one scene.) And "Revolving" is step 2: insert their own mind into the chip, or swap chips, or whatever. Gaining a form of immortality. Maybe this is the master plan, and why they're really there? Anyway...

Helly calms herself down with the "Forgive Me" mantra from the Break Room, which is a pretty chilling moment. And is determined to spill the beans at her speech. Cobel confronts her and threatens her, but Helly starts her speech talking about the hell that is: being Severed at Lumon.

Again, no real hurrying to tell someone. Though she's in a difficult situation--it's clear there is no one she can trust here. So while I felt a little frustrated watching it, it's more understandable here.

What does Mark do? He wanders a bit--but figures out who his sister Devon is and speaks to her. There's some bait-and-switch stuff with going to talk, then not able to talk. Going to see Gemma's face and realise she's in Lumon, then not. Where's the baby? Oh it's there.

...Stringing us along between scenes of the other Innys. Effectively padding out the episode, but also letting the tension build over time as Dyllan is at risk.

Ricken has a dodgy throat (unclear if this is to become "a thing," or just Ricken being his sensitive self and not used to speaking for so long). Mark speaks to him, gushing about how the book changed his life.

I liked this thread. The idea that platitudes that barely make sense and "you can do it if you believe" encouragement actually can help people. The Innys have never heard such platitudes and pun-based encouragement, and it opens up a whole new way of looking at the world for them. That was pretty cool!

Anyway... Mark finally gets to speak to Devon and--off-screen--tells her everything.

This went the best out of the 3. He had the most focus on the task at hand, and actually did it completely. He wasn't rushing as hard as the tension from Dyllan suggested they all should be, which was frustrating. But something (presumably) will actually happen from this that they wanted to happen from this whole plan in the first place. Because he actually said something.

He does finally discover a photo with him and Gemma in it, realises she's still alive and in Lumon. Which actually we already knew from a couple of episodes earlier. So that didn't change anything for the viewer. And Mark never knew her, hasn't been dealing with the grief over her death for years. So... didn't change a whole lot for him either? All he knows is that his Outy's wife is thought to be dead, but is not.

(I can't remember when or how he found out about Gemma's death, but I'm pretty sure it happened at some point somehow.)

And he blurts it out to the room in this pained scream. (I'm not sure if Inny Mark would react so strongly, but Outy Mark would. ANd it's the end of the finale so I guess that's fine just to ramp up the drama if nothing else.)

And... cut to black. That's where the season ends.

Wait... that's where the season ends?!

What happened to the mystery of what is going on at Lumon? The reason we're enjoying the show so much is because of the promise of some sort of reveal to that core mystery.

Even if they didn't answer the whole thing, something was needed. Something was promised.

Remember how a story is a mystery solved? Severance is currently not a story! We did not get a story, or even a chapter of a story, in Severance so far. Nothing was completed, nothing even worked towards answering anything.

There wasn't even a twist at the end with some new mystery!

(Which would have been annoying, but could have been made to answer things and ask things at the same time if they did it right.)

They didn't even escape. They took one step towards getting "outside." One step towards maybe escaping or being freed later on.

Now, this thread didn't bother me so much. I guess you could say the promise made by "We want to escape" is something like... we see them and the outside in the same shot.

Whether that's because they escaped fully, or realise it's a much bigger undertaking (for season 2) to actually escape, or it's within reach but they fail or die or something. Even a "from the frying pan into the fire" twist where it turns out that the place they want to be is bad in its own cruelly ironic way.

Any of those would close off (to some degree) the promise of "escape." You know, something big that the characters have accomplished or made progress on.

I'd say that them at least seeing the outside fulfills that well enough for me personally. Though I could see it frustrating some viewers--that's fair enough.

The fact is, I have no idea if the makers of the series know how to end a story. How to solve a mystery satisfactorily. That's the problem.

There are a lot of serialised shows (meaning stories chopped into many sections and shown as episodes) that are also mystery shows... that go nowhere, because they just keep throwing in new weird mysteries and never definitively answering any of them, and never tie them all together so it all makes sense to the viewer.

It's actually pretty easy to do that. It's just one step up from confusing the reader. If you don't need anything to make sense, you can say whatever you want and it's just fine. You can keep that going for years, stringing people along with the promise and implication that there are answers that satisfy all of your questions, and they will come... and then just not giving those at all.

(I'm looking at you, Lost.)

A story can be about many things. It can be about the characters, the drama, the relationships. It can be about the plot, the big-bad, the plans and how things-don't-go-according-to-them. It can be about escape or return, about grand ideas, about slavery, democracy, truth, love... your story can be about anything you can imagine.

Whatever it's about, you tell the reader or the viewer what it's about by how it starts, and what you focus on as it continues. If your first episodes starts with a big mystery, if your show continues to add new mysteries to the pile... you are promising that these mysteries are worth being part of the story; you are saying to those that engage in your story that it's worth thinking about that thing.

If you choose your story to be about mystery, the only way it's worth them thinking about a made-up mystery about a fictional world is... that they will enjoy solving the mystery. That all will be revealed, and their theories will be proven right, or they will be enlightened by the answers. That they will savour the satisfaction of understanding what once seemed impossible to explain.

Remember to actually do that, though. It's your responsibility to let them actually learn new things about the mystery, to help them understand what they've been pondering on for weeks or even years. And it's to your benefit to show that you know how to do that in a satisfying and reasonable way.

If you don't, then while you're having fun throwing in weirder and weirder stuff to your mystery box... you're risking people giving up on it entirely and walking away. Especially those that have been let down by other writers who promised the same things you have.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Experiential Description

As writers, it can be difficult to know what to put in, what to leave out. What to include, what to skip. What is too much detail, what is not enough. We can get carried away describing an object for pages, or setting the scene for what seems like the whole chapter before anything happens. How abstract is too abstract? How concrete is too much?

How can we find the right balance?

Feedback is always a good way of figuring that kind of thing out, dialing things in to balance it just the way we want it. But there's a certain way of looking at writing which gives a whole new dimension to what it means to write, and also helps a lot with this question.

The writer is a transcriber of experience.

Let me explain...

Think about what is happening as a person reads a story. They see text. They turn it into meaning. The meanings string together to form an experience. The experience of being in another world, of observing people doing things, of feeling explosions knock them off their feet, of having their first kiss.

No matter how you look at it, no matter what style we prefer to write in, we are providing the reader with an experience.

Often the experience we want to give is from one of our characters. We call this the "viewpoint" character.

Or it could be from the "viewpoint" of the narrator, a nebulous all-seeing observer from the shadows that only exists for us to see the world through--or more than that if we want to get fancy.

It could even be some theoretical person we imagine in the scene, purely to be able to put ourselves in their place and think about what it would be like to be there--to experience witnessing whatever goes down in the scene.

We want the reader to have that same experience. To know what it's like to be our viewpoint character in this moment, or at least imagine what it would be like to be there in the room when it all goes down.

This is how they immerse themselves in the story; they pretend it's real, and "remember" being there. How? By taking the text and forming such an experience in their own minds.

The better the text reads like an experience the reader could have within your world, the easier it will be to translate the text into an experience. And the easier it will be form them to immerse themselves in the story.

Now, how does that apply to descriptions?

Think about something you have experienced many times: walking into a room.

When you walk into a room, do you pick up on every tiny detail, scan and analyse every "pixel" you see? Or do you glance about and get a general sense for the space? Probably the latter. At least at first.

So which would describe a human experience of entering that room better: a few pages describing every object in the room? Or a brief overview of the space to give the general idea?

It was a small room, lit only by a crack in the curtains at the far end. The walls were dressed in peeling wallpaper of a long out of fashion floral style, and the two armchairs were positioned to try--and fail--to hide old tea stains on the rough carpet beneath.

Now, that might change. If you were stuck in a waiting room for more than a couple of minutes, you'll probably get bored. You could start studying what's around you, looking around for something interesting. Or poking around whatever's there.

There was a mantle on the long wall of the room, covered in plastic nick nacks from cereal boxes and Kinder eggs. Little men with funny hats. Pigs playing golf. A moon with the face of Elvis embossed in it.

So, more detail may come over time. But not as soon as we enter a space.

That's just how human brains generally work. They notice the big obvious things, the things that catch their attention, the things that are different.

A way to sum up this concept is...

What do they notice, and why?

A woman burst into the room, a big floppy yellow hat wobbling about her head as she locked eyes with his.

If there's no reason to notice her shoes, they don't notice her shoes. So don't describe her shoes. Maybe they can't see the bow at the back of her dress. So don't describe the bow.

The temptation is, you've written out a list of details of how this character looks, and you want to use them all. It's easy for that to turn into a list of facts--as it is literally based on your list of facts in your worldbuilding document.

What you want is to step away from that, and think about the experience of the viewpoint character seeing this. Or what the reader would notice if they were in the room.

This woman might be so captivating--or menacing--to the viewpoint character that they just don't take in much else about her in this moment.

Or they may notice only a few smaller details that make her so captivating.

Her steel-grey eyes glared fiercely. It felt like she was boring into his soul with her stare. He gulped.

If she's wearing a lot of jewelry, maybe they notice that. The bigger things are more noticeable, so have them be noticed first. But they don't notice the gun she's holding subtly at her side.

...Unless something brings their attention to it.

She smiled. "With me or without me?" He opened his mouth but couldn't speak. They were hot on his tail, but could he trust her? Who even was she? She tapped a nail on something at her side. He looked down at a small handgun, half hidden in her skirts. Her tone became more urgent. "You coming or what?"

If you want them to notice something, contrive some excuse for them to notice it. Draw their attention to it. Make it enter their experience.

But if there's nothing else that would catch your attention, just stop. That's fine. That's how we work as humans too. We pay attention to what is immediately obviously important, and then our minds wander.

This gives you a nice natural equilibrium for how much detail to put into your descriptions. Match what you'd notice, what you'd care about as the viewpoint character in this moment. Give them that experience through how you describe things.

Another aspect of this is, it is a person's experience. Not the same as the reader's, not the same as the omniscient writer's... it comes from a person within the scene who has their own thoughts and feelings in this moment. And their own thoughts and feelings on what they're observing.

Sure, you can simply describe a sunset in a factual way--"The sun was low, the sky and clouds tinted orange." But if you saw the same sunset when you just proposed and she accepted you'd experience this moment of seeing a sunset very differently to if she'd rejected you.

This is exactly what the idea of "rose-tinted glasses" is all about. The way you feel colours the way you see things.

These thoughts and feelings warp how we see the world, and how we'd describe what we see or even the situation in general. What words would the character use that reflect those inner feelings? Ask yourself...

What does it feel like to see it?

The blood red of the sunset stained the sky. vs The sky blushed as the sun dipped below the horizon.

Reading a description of the same thing makes you the reader feel those different things, doesn't it?

What would you think about what you're seeing?

They were running out of time--the sun was already setting! vs It was so calm here above the canopy, so peaceful as the sun set. There was no way to tell there was a war raging below.

This is a good way of working exposition into the prose, while also grounding the description to something that matters to the story.

What do they notice, and why?

Hills wave across the horizon, villages of people gathering in the crooks of forests. vs The older towns looked run down from here, showing their wear. How many would survive what was to come?

Different characters may notice different things, too. An architect student may dwell on the Elizabethan decorations at the head and foot of the columns nearby. A world weary con man may pick up on the interactions and power plays between people as he passes them by.

There's a classic exercise to practise writing in this way...

Write about one of your characters walking through a space, and then write about a different character walking through the same space. How does their individual interest change how it's written, what they point out? But you can take it a step further. Have characters with different backgrounds or areas of expertise. But also characters in a different frame of mind. Feeling different things. What happened just before that affects how they see their hometown? What are they anticipating will happen when they reach the end of the street? What is happening as they move through the market that makes some things more important to them than others?

As a personal aside, I really like using light in my descriptions. For setting the vibe of a scene:

A brightly lit ballroom in the sun vs A dark gargantuan ballroom, lit by nothing but a sputtering candle

And also for directing attention:

Light glinted off a blade, as he threw a knife that seemed to come out of nowhere!

A cool thing about this whole writer-reader relationship is... they are involved too. We're writing text that they are interpreting into their own version, their own experience.

So while we can't (and shouldn't) give every detail of everything they would sense if they were in our scene... they have their own experiences, their own real memories to draw on. They will naturally fill in the gaps.

We tell them about a run down music hall... and even if we don't explicitly describe it, they can fill in the texture of the wood floor, the sound footsteps make in the empty hall, the smell of decades of parties and dancing sticking to the walls.

And that actually makes it more real to them. Because part of that completely fictional place is made up of completely real places they know.

Those gaps may be filled a little differently. If I say "sports car" you'll easily conjure an image of a sports car, even if it has a different colour, different shape... maybe you have a specific brand or model in mind that I don't.

But whatever they're visualising in their head is way more real than anything you could describe in the text. It has real world physical lighting and reflections, the undulations of the body panels are perfect and beautiful, the colour has a brilliant vibrance in the sunlight, or moonlight, or whatever place the reader put that car in.

And they'll do that for you, make the world more real for you... for free!

There's a saying in horse riding: "Give the horse its head." When terrain is tricky and hard to navigate through when there's a horse in the way so you can't see it... remember that the horse knows how to walk. The horse can see what's down there, and knows how to move over tricky terrain. So don't try to control every step, by pulling their head this way and that... give them some slack, let them do their thing, give the horse its head.

(Note, this is my understanding of it, but I'm not a trained rider.)

The reader knows how to imagine things. The reader knows what a sports car looks like. Don't hold onto their brains so tightly that they get bored of the over-detailed descriptions. Give the reader their head. Let them fill in the gaps.

Now, if you later assume certain things about this sports car, like it's yellow and has a spoiler on the back... it's going to be real awkward for the reader if they've imagined something different when you gave them some wiggle room.

Their brain, even if it's fast and subconscious, has to rewind and playback the scenes with a yellow sports car instead of the red sports car they had in mind. That takes them out of the flow, it breaks the reality of what they were experiencing.

So, don't just leave it wide open to whatever they fancy--define what needs defining, if you rely on some unspoken context be sure to plant it earlier when you first showed them that detail.

(Read more about the idea of context and continuity.)

But also, it's okay for there to be gaps. Let them fill those in with their own imagination and experiences to the table. Let them make it real for themselves.

Metaphor can get to the heart of the vibe.

Descriptions can use metaphor and simile to help indicate these more abstract "vibes."

The car crouched in the old garage, as if ready to spring to life at any moment despite the dirt and dust sheets that covered it. Beside her, her husband snored like an agitated hippo.

Though using metaphor simply to describe the thing isn't so useful.

The car was as red as a rose.

What is that even trying to say? A rose can be red. A car can be red, like a rose can be red. But it's not clear there's anything meant by the metaphor beyond that.

If the meaning you're going for is "it's red," then you can just say that rather than imply there's some deeper meaning that makes the reader scratch their heads trying to interpret it.

In theory you can twist it to have some meaning if you wanted to, with some more context around the description. But without that, it'll only serve to confuse the reader and waste time.

Make sure a metaphor adds to the experience, not just reiterates it.

Verb choice can describe more than the action itself, too. Actions can include metaphor.

Light sliced through the room. Light poured in through the open curtains. Light beat down upon them, making them squint and squirm.

The verbs "sliced," "poured," and "beat" don't really make literal sense. Light "shines," and that's kind of it I guess? But we understand that the light is shining... in a "slicing" kind of way, and so on. These metaphorical verbs give very different impressions of the light, how it feels to see it, or be in it. The verb itself "describes" that feeling, describes an emotion. Makes the action more experiential.

These ideas apply just as well to any description, any scene, any situation really. Think in terms of the experience of being there, and try to give the reader that.

This actually means a more "lossy," incomplete representation than you may think. A representation "tainted" with the person's biases, feelings, all of that stuff--that's what makes it feel like a real experience. Seeing it through their lens. The slight wonkiness we bring to the table as subjective beings.

Real, hard facts don't make it feel more real. It's the ways reality bends to our perception that makes it feel real and grounded. Or to look at it another way, our goal isn't to make the world feel real and concrete, but to...

Make the experience of the world feel real

...by giving the reader concrete details, in the way a person seeing them would see them.

Seeing such descriptions as more than descriptions, as character, as history, as emotion... makes the descriptions part of the story, part of the experience. It has more meaning than a list of facts.

It becomes worth writing, worth studying and finessing. And it becomes worth reading, worth experiencing for the reader. Worth reading.

#light#description#adjective#verb#action#experience#emotion#feeling#thought#lense#lens#rose tinted#notice#immersion#observe#sense#metaphor#simile#exercise

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tense and Timing

Have written, wrote, write, will write.

The "tense" of a word shows when an event happens in relation to "now." Past tense happened before now, future tense happened after now, and present tense happened... right now in this moment.

There are lots of complex tenses, but I'm talking in this article about writing fiction stories. So I will focus on what's useful to writers in that area--hopefully in a way that is easy to understand and put into practise.

People generally pick up on how various tenses work just by everyday reading. And we all generally do fine, even with the nuances and caveats. But when we come to take writing more seriously, to think about how things work grammatically, we can start to get muddled up and unsure of ourselves.

That's because there's an extra little wrinkle for prose. In our everyday conversations, we all know the reference point now, the present. Anything we are saying is happening "now" is happening in the present. So that has the present tense. Before now is the past, after now is the future. Simple.

But in a story the "now," the [current time], might be written in a different tense. Usually present tense or past tense, for most fiction. Because it's a decision we are making on how our story is written, we start consciously deciding on how other parts of the text uses different tenses.

We wonder, this looks like the wrong tense, but is it? If it is, how do I fix it? And which tense should I choose? What's the difference between them anyway?

We'll start with the basics. Past, present, and future...

"I eat" [present] tells you that in the present something is in my mouth being chewed.

Past

Say I'm telling you in the present that I ate before now. I would say "I ate" [past] instead. Eating happened in the past, so I use the past tense form of the verb.

If I'm telling you that I slept before I ate, then from the eating reference point the sleeping happened in the past. From the time I'm speaking from, we go further into the past to eating [past], and even further into the past to sleeping [past + past]. Double-past! 👀

Although "sleep" doesn't have a double-past form. Verbs just don't have a version that indicates [past + past]. You can go back in time to "slept," (or "sleeped") but that's as far as you can go... without help!