#woolworth fortune

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Farrah Fawcett as Barbara Hutton: Poor Little Rich Girl: The Barbara Hutton Story (1987).

The true story of one of the richest women in America - heiress to the Woolworth fortune. She had vast wealth and seven husbands, but never found lasting love.

IMDb 6,9

#1987#farrah fawcett#barbara hutton#poor little rich girl#The Barbara Hutton Story#true story#drama#movie#film#woolworth#woolworth fortune#seven husbands#seven marriges#socialite#farrah#fawcett#barbara#hutton#mini series

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Frank Woolworths $90,000,000 ABANDONED Mega mansion

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cary Grant and Barbara Hutton, heiress to the Woolworth''s fortune, were married on July 8, 1942. They divorced in 1945.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

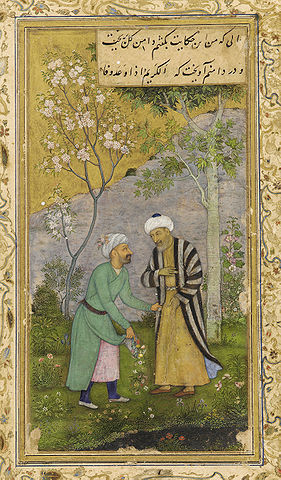

"I cursed the fact that I had no shoes until I saw a man who had no feet."

By Saadi

The quote is not a proverb in Persian and in fact is a part of an important book called Golestan written by Saadi Shirazi. He was a poet who lived between 1210-1291in central Iran.Famous for the deep meaning of his writings, both social and moral.

I have come across several websites that cited the quote: “I cried because I had no shoes until I met a man who had no feet” and its variants.

Sadly, the claims of the origin of this quote vary. Some cite it as Chinese, Indian, Jewish, Irish, etc. Usually, it is quoted as anonymous with source unknown.

In Goodreads, we find two instances of the quote. One says Helen Keller said it and another says it was said by Wally Lamb.

In her book “EFFECTIVE LIVING,” Lois Smith Murray says on page 154:

Tolstoy wrote, “I cried because I had no shoes until I met a man who had no feet.”

In his book “A FOR ARTEMIS,” Sutton Woodfield says on page 44:

Over Goldie’s bed, tacked on the wall, was one of those mottoes you can buy at Woolworths for a bob. This one said, “I cried because I had no shoes until I met a man who had no feet.”

However, the most common claim points to the Persian poet Abū-Muhammad Muslih al-Dīn bin Abdallāh Shīrāzī (Persian: ابومحمد الدین بن عبدالله شیرازی), better known by his pen-name Saʿdī (Persian: سعدی) or Saadi Shirazi or simply Saadi. Born in Shiraz, Iran, c. 1210, he was one of the major Persian poets and prose writers of the medieval period.

.

His best-known works are Bustan (The Orchard) completed in 1257 and Gulistan (The Rose Garden) in 1258.

.

Saʿdī composed his didactic work Gulistan in both prose and verse. It contains many moralizing stories like the fables of the French writer Jean de La Fontaine (1621-95) and personal anecdotes. The text interspersed with a variety of short poems contains aphorisms, advice, and humorous reflections. It demonstrates Saʿdī ‘s profound awareness of the absurdity of human existence.

In Persian lands, his maxims were highly valued and manuscripts of his work were widely copied and illustrated. Saʿdī wrote that he composed Gulistan to teach the rules of conduct in life to both kings and dervishes.

In Chapter III – On the Excellence of Contentment, story 19, Saʿdī wrote:

I never lamented about the vicissitudes of time or complained of the turns of fortune except on the occasion when I was barefooted and unable to procure slippers. But when I entered the great mosque of Kufah with a sore heart and beheld a man without feet I offered thanks to the bounty of God, consoled myself for my want of shoes and recited:

‘A roast fowl is to the sight of a satiated man Less valuable than a blade of fresh grass on the table And to him who has no means nor power A burnt turnip is a roasted fowl.‘

In the case of Helen Keller the quote “I cried because I had no shoes until I met a man who had no feet” derived from Saʿdī ‘s story had been her credo. It helped her overcome self-pity and to be of service to others.

By T. V. Antony Raj

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Fourth of July in New York

It was the fourth of july in new york

and the sun was high in the sky above the east river

a perfect clear day

in the daylight of my life

I was 20 and had never loved America

at least not for a very long time

but wore an American flag halter top under my overalls

and smiled widely

because I knew my good fortune

to be there at all

mingling with the monoliths

and making conversation with history

My boyfriend asked about the buildings that formed the teeth of the jagged skyline

because he knew I had spent hours on Wikipedia

and fashioned myself an expert

I was 20 and beaming into the glistening water

waving to the people on the passing boats

and celebrating a country that did not celebrate its people

a country whose voice could be heard most loudly

in the hateful and broken shouting

of those who claimed to love freedom

but had always loved themselves more

I was 20 and had been born into a post-9/11 world

the city’s crowning jewel stood tall

its spire lit up red white and blue for the occasion

looming high with a watchful eye

reflecting the world below

I pointed to the woolworth building

“That one’s my favorite,” I said

I could have talked about it for hours

as it stood there in all its terracotta glory

but my throat was suddenly tight

and I did not want to talk about anything

I nodded along to “Born in the U.S.A”

and really felt it

for the first time

as the sky began to darken

In many ways, the country I had been born into no longer existed

the sacred right to choose

the veil of civility

pulled back to reveal the truth of Her face

the truth of what She had let Herself become

Her once-bright eyes had grown hollow

and the lines of Her face betrayed Her rage

Her righteous anger

trembling at the gilded altar

before giving Herself away

to a rich man

who does not know the truth of Her soul

The macy’s boat shot color into the sky

and they wed under the fireworks

soundtracked by katy perry and lee greenwood

until it started to rain

And Lady Liberty began to weep.

#poetry#original writing#creative writing#poem#anecdotes#free verse#tumblr poetry#american politics#original poem#poems on tumblr

1 note

·

View note

Text

Are 2 Minute Noodles Bad for You? Exploring Health Implications

In today’s fast-paced world, convenience often trumps nutritional considerations when it comes to meal choices. Among the many quick-fix options available, 2-minute noodles have become a staple for busy individuals seeking a quick and easy meal solution. However, concerns have been raised about the health implications of consuming these convenient noodles regularly. In this article, we’ll delve into the nutritional profile of 2 minute noodles bad for you, explore potential health risks, and discuss alternatives for healthier noodle options.

The Nutritional Profile of 2 Minute Noodles:

2-minute noodles typically consist of pre-cooked deep fried noodles packaged with flavouring sachets containing seasonings and additives. While these noodles offer convenience, they contain very little nutritional content. A typical serving of instant noodles is high in carbohydrates and minimal protein, making them essentially empty calories. However, the real nutritional red flag lies in the high sodium content and the presence of artificial additives and preservatives in the season.

Health Risks Associated with 2 Minute Noodles:

The high sodium content of 2-minute noodles is one of the primary concerns for health experts. Excessive sodium intake is linked to hypertension, heart disease, and stroke. Additionally, the artificial additives and preservatives found in seasoning sachets are likely to have adverse effects on health over time. Some studies suggest a correlation between regular consumption of instant noodles and an increased risk of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and other chronic health conditions.

Are there HEALTHIER ALTERNATIVES?

Fortunately, there are some excellent healthier alternative to noodles to traditional 2-minute noodles that offer better nutritional value and fewer health risks. While Woolworths and Coles are yet to expand their range of healthier options in this category, there are a range of companies that have ventured into the ‘healthy instant noodle’ space. Immi Ramen and Vite Ramen have launched in the US and in Australia our very own brand Wholesome Bowl became available online and in independants in January 2023 to fill an essential gap in the ‘healthy-convenient food’ market.

Wholesome Bowl noodles are a healthy 2 minute noodles alternative where you can forget the nasty stuff. While maintaining the convenience of a quick meal, Wholesome Bowl noodles offer the added benefits of high protein and fibre, and 16 essential vitamins and minerals. The pre-cooked noodles are also air-dried instead of deep-fried, and the seasoning sachet is free from artificial additives.

Simply add some fresh vegetables and lean proteins, and you have yourself a convenient AND nourishing meal! Wholesome Bowl noodles prioritise overall health and wellbeing, providing an option for those who crave the unmatched convenience of instant noodles without compromising their health.

While 2 minutes noodle offer unbeatable accessibility, their nutritional content and potential health risks should not be overlooked. Understanding the nutritional profile of these noodles, acknowledging the associated health risks, and exploring alternatives like Wholesome Bowl noodles are essential steps in making informed dietary choices. With options like Wholesome Bowl, you can enjoy the convenience of 2-minute noodles without compromising your health.

Wholesome Bowl ships Australia wide.

This Blog was Originally Published at Wholesome Bowl on April 11th, 2024

0 notes

Text

The most expensive Mom jewelry in the world

https://oragift.shop/collections/mom-jewelry

Mom jewelry is a special category of jewelry that celebrates motherhood and family. It can be personalized with names, initials, birthstones, or photos of loved ones. It can also be symbolic of the bond between a mother and her children, such as a heart, a circle, or a tree. Ora Gift Mom Jewelry can be a meaningful gift for mothers, grandmothers, or any woman who has a maternal role in someone's life.

While mom jewelry is generally sentimental and affordable, some of it is exceptionally rare and expensive. These pieces of mom jewelry are made with the finest materials and craftsmanship, and often have a unique history or significance behind them. Some of them are owned by celebrities, royalty, or collectors, who are willing to pay a fortune for these exclusive pieces. Check out some mom jewelry.

In this blog post, we will explore the most expensive mom jewelry in the world, and what makes it so special. We will also look at some of the other expensive mom jewelry that have been sold or auctioned in the past.

The L'Incomparable Diamond Necklace - $55 Million

The L'Incomparable Diamond Necklace is the most expensive mom jewelry in the world, with a staggering price tag of $55 million. It is also the most valuable necklace in the world, according to the Guinness World Records. The L'Incomparable Diamond Necklace was created by Mouawad, a Swiss luxury jewelry brand, and features a 407.48-carat yellow diamond, the largest internally flawless diamond in the world. The diamond is suspended from a 18-karat rose gold chain that has 230 smaller diamonds, totaling 91.8 carats.

The L'Incomparable Diamond Necklace is a masterpiece of nature and art, and it has a fascinating story behind it. The diamond was discovered by a young girl in the Democratic Republic of Congo in the 1980s, who found it among a pile of rubble from a nearby mine. The diamond was later acquired by Mouawad, who named it L'Incomparable, meaning "the incomparable" in French. The diamond was then set in a necklace that took four years to complete, and was unveiled in 2013.

The L'Incomparable Diamond Necklace is a one-of-a-kind piece, and it is a perfect example of mom jewelry, as it was found by a child and represents the beauty and rarity of motherhood. The necklace was sold to an anonymous buyer in 2013, who reportedly bought it as a gift for his wife. ¹²³

The Cartier Art Deco Diamond Bracelet - $2.5 Million

The Cartier Art Deco Diamond Bracelet is another expensive mom jewelry, which was sold for $2.5 million at a Sotheby's auction in 2015. It is a stunning example of the Art Deco style, which was popular in the 1920s and 1930s, and influenced by geometric shapes, symmetry, and elegance. The Cartier Art Deco Diamond Bracelet was made in 1937, and it features a platinum band with the name "Cartier" spelled out in diamonds. The bracelet has 46.30 carats of diamonds, including a 10.48-carat emerald-cut diamond in the center, and two pear-shaped diamonds on each side. The bracelet also has a hidden clasp, which allows it to be worn seamlessly.

The Cartier Art Deco Diamond Bracelet is a rare and beautiful piece, and it reflects the craftsmanship and prestige of Cartier, a French luxury jewelry and watch brand founded by Louis-François Cartier in 1847. Cartier is known for its elegant and timeless jewelry designs, and has a loyal clientele that includes celebrities, royalty, and aristocrats.

The Cartier Art Deco Diamond Bracelet is a unique and exquisite piece, and it is a great example of mom jewelry, as it was owned by a famous mother and daughter duo. The bracelet was originally owned by Mary Scott, the wife of Woolworth heir Franklyn Laws Hutton, and the mother of socialite and actress Dina Merrill. The bracelet was then inherited by Merrill, who was also a successful businesswoman and philanthropist. Merrill sold the bracelet at a Sotheby's auction in 2015, along with other pieces from her jewelry collection. ⁴

The Tiffany & Co. Schlumberger Sapphire and Diamond Bracelet - $1.5 Million

The Tiffany & Co. Schlumberger Sapphire and Diamond Bracelet is another expensive mom jewelry, which was sold for $1.5 million at a Christie's auction in 2011. It is a magnificent piece of jewelry, featuring a 18-karat gold band with a floral design, adorned with sapphires and diamonds. The bracelet has 27.64 carats of sapphires, including a 14.28-carat oval-cut sapphire in the center, and 14.36 carats of diamonds, including round, marquise, and pear-shaped diamonds.

The Tiffany & Co. Schlumberger Sapphire and Diamond Bracelet is a splendid and versatile piece, and it showcases the style and quality of Tiffany & Co., an American jewelry brand famous for its diamond engagement rings and high-quality innovative designs. The bracelet was designed by Jean Schlumberger, one of the most influential jewelry designers of the 20th century, who worked for Tiffany & Co. from 1956 to 1970. Schlumberger was known for his colorful and whimsical creations, inspired by nature and art.

The Tiffany & Co. Schlumberger Sapphire and Diamond Bracelet is a stunning and unique piece, and it is a wonderful example of mom jewelry, as it was owned by a legendary mother and daughter pair. The bracelet was originally owned by Elizabeth Taylor, one of the most famous and glamorous actresses of all time, who had a passion for jewelry and a collection of over 10,000 pieces. The bracelet was then inherited by Taylor's daughter, Liza Todd, who was also an actress and producer. Todd sold the bracelet at a Christie's auction in 2011, along with other pieces from her mother's jewelry collection.

0 notes

Text

On the first day of January 1931 the department store heir Lee Adam Gimbel jumped from the sixteenth floor of the Yale Club, having seen his fortune disappear with the economic downturn. In February the once-wealthy owner of a shoe company poisoned himself in a downtown hotel. In March a plumbing supply manager jumped from the ninth floor of the New York Athletic Club. In April the broker-husband of heiress Jessie Woolworth killed himself with mercury bichloride. In May a law firm partner dived out of his third-floor room at the Hotel Commodore, dying of a fractured skull.

—The Poisoner's Handbook by Deborah Blum

#writeblr#bookblr#books#book quotes#quotes#the poisoner's handbook#deborah blum#the poisoner's handbook by deborah blum#the poisoner's handbook quotes#jamietukpahwriting

0 notes

Text

Add Color to Your Life: Discover the Cheapest Places to Buy Flowers in Melbourne

Everyone loves the vibrancy and joy that flowers bring. They're a simple, elegant way to liven up any space and can serve as the perfect gift for all occasions. Yet, buying flowers regularly can become quite expensive. But what if you could fill your world with the vivid hues of nature without spending a fortune? Melbourne, known for its cultural diversity and vibrant lifestyle, has numerous places to find beautiful and affordable blooms. This blog post, courtesy of the Best Melbourne Blog, will guide you through the cheapest places to buy cheap flowers in Melbourne. Let's explore and add some color to your life!

Melbourne Flower Market

The Melbourne Flower Market is a great place to find everything related to flowers. You can discover a wide variety of flowers at wholesale prices, including roses and lilies. If you're ever in the mood for a lively Japanese buffet in Melbourne, why not grab some affordable flowers there?

Local Florist Shops

As you wander through the city, take notice of the amazing best formal dress shops in Melbourne that catch your attention. But don't forget to explore the many charming local florist shops throughout the city. These shops often have flowers available at much lower prices compared to high-end florists. Additionally, when you support local businesses, it adds another element of satisfaction to your purchase.

Supermarkets

When looking for cheap flowers in Melbourne, make sure you don't forget about supermarkets. Coles and Woolworths are supermarkets that frequently have reasonably priced flower bouquets available. While they may not offer the same variety as the best Indian restaurant in Melbourne, they are perfect if you're looking for a quick and affordable floral option.

Online Flower Shops

With the advent of the internet, even shopping for flowers has transitioned to the online realm. In Melbourne, you can find plenty of online flower shops that offer affordable flowers. Why not take the opportunity to browse online for affordable flowers while you wait for your cake and balloon delivery in Melbourne?

DIY Flower Picking

If you enjoy pottery classes in Melbourne, you might also enjoy the creative activity of selecting your flowers. Many farms are located on the outskirts of Melbourne, where you can go and pick your flowers at a very reasonable price.

Conclusion

Melbourne, known for its Asian restaurants Melbourne and vibrant city life, also offers a variety of places to buy cheap flowers in Melbourne. From markets to supermarkets, there's a range of options to find cheap flowers in Melbourne. Whether you're sprucing up your home, surprising a loved one, or adding a finishing touch to a dinner party, there's no need to break the bank.

Visit Best Melbourne Blog to discover more about where to find cheap flowers and other must-visit spots in Melbourne, from the best dental clinics in Melbourne to the best kindergarten in Melbourne. With so many options, adding a splash of color to your life in Melbourne has never been easier or more affordable.

0 notes

Photo

Women’s History Month: More Nonfiction Recommendations

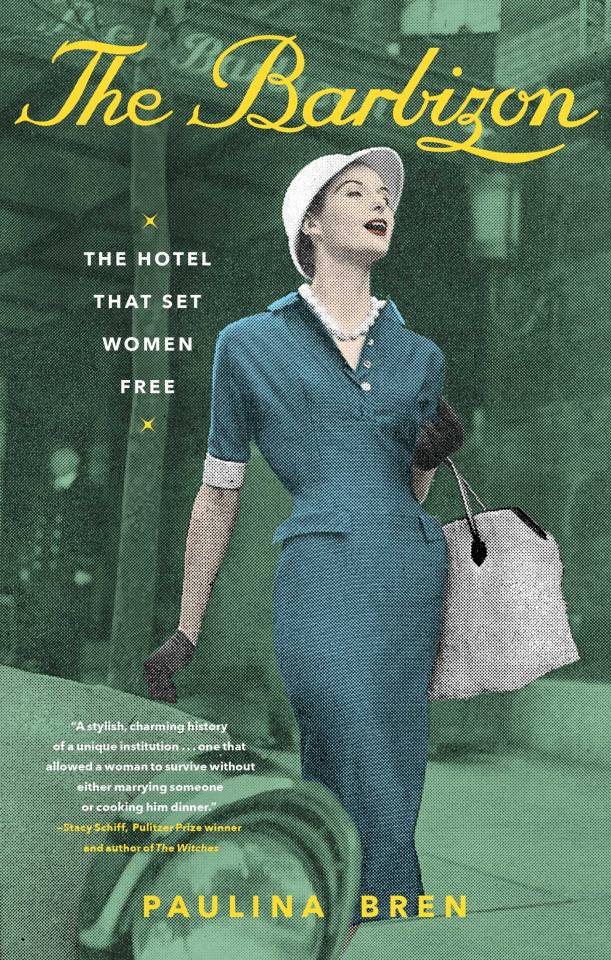

The Barbizon by Paulina Bren

Welcome to New York's legendary hotel for women.

Liberated from home and hearth by World War I, politically enfranchised and ready to work, women arrived to take their place in the dazzling new skyscrapers of Manhattan. But they did not want to stay in uncomfortable boarding houses. They wanted what men already had - exclusive residential hotels with maid service, workout rooms, and private dining.

Built in 1927, at the height of the Roaring Twenties, the Barbizon Hotel was designed as a luxurious safe haven for the "Modern Woman" hoping for a career in the arts. Over time, it became the place to stay for any ambitious young woman hoping for fame and fortune. Sylvia Plath fictionalized her time there in The Bell Jar, and, over the years, it's almost 700 tiny rooms with matching floral curtains and bedspreads housed, among many others, Titanic survivor Molly Brown; actresses Grace Kelly, Liza Minnelli, Ali MacGraw, Jaclyn Smith; and writers Joan Didion, Gael Greene, Diane Johnson, Meg Wolitzer. Mademoiselle magazine boarded its summer interns there, as did Katharine Gibbs Secretarial School its students and the Ford Modeling Agency its young models. Before the hotel's residents were household names, they were young women arriving at the Barbizon with a suitcase and a dream.

Not everyone who passed through the Barbizon's doors was destined for success - for some, it was a story of dashed hopes - but until 1981, when men were finally let in, the Barbizon offered its residents a room of their own and a life without family obligations. It gave women a chance to remake themselves however they pleased; it was the hotel that set them free. No place had existed like it before or has since.

D-Day Girls by Sarah Rose

In 1942, the Allies were losing, Germany seemed unstoppable, and every able man in England was on the front lines. To “set Europe ablaze,” in the words of Winston Churchill, the Special Operations Executive (SOE), whose spies were trained in everything from demolition to sharpshooting, was forced to do something unprecedented: recruit women. Thirty-nine answered the call, leaving their lives and families to become saboteurs in France.

In D-Day Girls, Sarah Rose draws on recently declassified files, diaries, and oral histories to tell the thrilling story of three of these remarkable women. There’s Andrée Borrel, a scrappy and streetwise Parisian who blew up power lines with the Gestapo hot on her heels; Odette Sansom, an unhappily married suburban mother who saw the SOE as her ticket out of domestic life and into a meaningful adventure; and Lise de Baissac, a fiercely independent member of French colonial high society and the SOE’s unflappable “queen.” Together, they destroyed train lines, ambushed Nazis, plotted prison breaks, and gathered crucial intelligence - laying the groundwork for the D-Day invasion that proved to be the turning point in the war.

Heiresses by Laura Thompson

Heiresses: surely they are among the luckiest women on earth. Are they not to be envied, with their private jets and Chanel wardrobes and endless funds? Yet all too often those gilded lives have been beset with trauma and despair. Before the 20th century a wife’s inheritance was the property of her husband, making her vulnerable to kidnap, forced marriages, even confinement in an asylum. And in modern times, heiresses fell victim to fortune-hunters who squandered their millions.

Heiresses tells the stories of these million dollar babies: Mary Davies, who inherited London’s most valuable real estate, and was bartered from the age of twelve; Consuelo Vanderbilt, the original American “Dollar Heiress”, forced into a loveless marriage; Barbara Hutton, the Woolworth heiress who married seven times and died almost penniless; and Patty Hearst, heiress to a newspaper fortune who was arrested for terrorism. However, there are also stories of independence and achievement: Angela Burdett-Coutts, who became one of the greatest philanthropists of Victorian England; Nancy Cunard, who lived off her mother's fortune and became a pioneer of the civil rights movement; and Daisy Fellowes, elegant linchpin of interwar high society and noted fashion editor.

Hidden Figures by Margot Lee Shetterly

Before John Glenn orbited the earth, or Neil Armstrong walked on the moon, a group of dedicated female mathematicians known as “human computers” used pencils, slide rules and adding machines to calculate the numbers that would launch rockets, and astronauts, into space.

Among these problem-solvers were a group of exceptionally talented African American women, some of the brightest minds of their generation. Originally relegated to teaching math in the South’s segregated public schools, they were called into service during the labor shortages of World War II, when America’s aeronautics industry was in dire need of anyone who had the right stuff. Suddenly, these overlooked math whizzes had a shot at jobs worthy of their skills, and they answered Uncle Sam’s call, moving to Hampton, Virginia and the fascinating, high-energy world of the Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratory.

Even as Virginia’s Jim Crow laws required them to be segregated from their white counterparts, the women of Langley’s all-black “West Computing” group helped America achieve one of the things it desired most: a decisive victory over the Soviet Union in the Cold War, and complete domination of the heavens.

Starting in World War II and moving through to the Cold War, the Civil Rights Movement and the Space Race, Hidden Figures follows the interwoven accounts of Dorothy Vaughan, Mary Jackson, Katherine Johnson and Christine Darden, four African American women who participated in some of NASA’s greatest successes. It chronicles their careers over nearly three decades they faced challenges, forged alliances and used their intellect to change their own lives, and their country’s future.

#women's history month#women's history#history#nonfiction#nonfiction books#Nonfiction Reading#Library Books#Book Recommendations#book recs#reading recommendations#Reading Recs#TBR pile#tbr#to read#tbrpile#Want To Read#book blog#library blog#Booklr#book tumblr

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Barbara Hutton

Barbara Hutton, sadly encapsulates another common thread between these “it” girls, a tragic past. Ms. Hutton, mockingly called “poor little rich girl,” had a consistently rocky life (London, n.p.). She is the daughter of Edna Woolworth and Franklyn Hutton, making her an heiress of Woolworth’s five-and-dime stores and E.F. Hutton and Company, her fortune amounting to about $50 million at the time (around a billion now) (Jennings, 17). Barbara found her mother dead at the age of four (Gressor & Cook, 260). Of course, being a high-profile family, the tabloids speculated whether or not Edna’s death was a suicide, following her knowledge of her husband’s affair (Plunkett-Powell, 131). However, even after experiencing such a tumultuous upbringing, her family gave her a lavish debutante ball for her eighteenth birthday where members of the Astor and Rockefeller family were guests and Rudy Valle and Maurice Chevalier were among the entertainment (Lambron, n.p.). While this may have appeased New York’s wealthy, the public was livid. Her ball took place at the beginning of the Great Depression which invited so much public scorn that she had to flee to Europe to avoid the press (New York Social Diary, n.p.). After she turns eighteen, she exhibits another habit of the “it” girl, an affinity for prestigious and/or wealthy men. Hutton had a total of 7 marriages to a plethora of men ranging from princes and barons to Hollywood royalty. Some of the most notable are Cary Grant, Alexis Mdivani, one of the marrying Mdivanis, and Count Kurt Haugwitz-Reventlow, the father of her only child (Heyman, n.p.). A few of her husbands were known to be abusive or after her fortune.. Hutton was notorious for her failed marriages and with her marriage to Porfirio Rubirosa, Phyllis Battelle of the Milwaukee Sentinel wrote, “The bride, for her fifth wedding, wore black and carried a scotch-and-soda." Along with her extremely public, failed relationships, she was known for excessive drug and alcohol use as well as her excessive spending. Barbara Hutton encapsulates the tragic, nepotism baby brand of “it” girl.

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

New York has always attracted the wealthy and predatory, dating back at least to our most famous pirate, Captain Kidd. Coming here was seen as a sort of arrival, for individuals and businesses alike. Long a “headquarters town,” as early as 1901 New York was home to sixty-nine of the nation’s two hundred largest corporations. Their owners lined Fifth Avenue with their fairy-tale mansions—some of them later converted into museums or elegant stores—or filled luxury apartment houses such as the Dakota. They hired the most renowned architects to erect gigantic advertisements for their transformative, world-conquering enterprises, including many of the most memorable structures ever built in the city: Grand Central Terminal; the Chrysler, Woolworth, Empire State, and Seagram buildings, among others. Noxious as the old robber barons could be, they at least dropped vast amounts of money into the local economy in the form of property taxes and purchases in elite shops. They employed people in droves—small armies of domestics, vendors, and workers at all levels—to service their needs and businesses. They contributed to the city through their building and philanthropy—Rockefeller Center, Carnegie Hall, the Morgan Library, and the Frick Collection, to name just a few examples. The new rich infesting the city, by contrast, are barely here. They keep a low profile, often for good reason, and rarely stick around. They manufacture nothing and run nothing, for the most part, but live off fortunes either made by or purloined from other people—sometimes from entire nations. The New Yorker noted in 2016 that there is now a huge swath of Midtown Manhattan, from Fifth Avenue to Park Avenue, from 49th Street to 70th Street, where almost one apartment in three sits empty for at least ten months a year. New York today is not at home. Instead, it has joined London and Hong Kong as one of the most desirable cities in the world for “land banking,” where wealthy individuals from all over the planet scoop up prime real estate to hold as an investment, a pied-à-terre, a bolt-hole, a strongbox. For most of a decade now, like lava flowing inexorably from some deadly volcano, the residences of the superrich have moved east from the Time Warner Center to create Billionaires’ Row, the array of buildings on 57th Street and several adjoining streets and avenues that is already dominating much of the Manhattan skyline. These “supertall” skyscrapers are defined as buildings taller than 984 feet: One57, at 157 West 57th Street (1,004 feet); 432 Park Avenue (1,396 feet). Well on their way to being built: 53 West 53rd Street (1,050 feet), 111 West 57th Street (1,428 feet), and 217 West 57th Street (1,550 feet). Finished or not, many of the apartments were—at first—snapped up as soon as they went on the market. The Times used to tick off their record-setting sales in its Sunday real estate section, down to the absurdly exact dollar and cent: one recent lower-end example, $47,782,186.53! Nor are the records these sales set likely to remain for long. A triplex at the forthcoming 220 Central Park South will reportedly be sold for $200 million, and a four-story apartment at the same address is priced to move at $250 million. These would be the largest home sales ever recorded anywhere in the United States. Who spends this sort of money for an apartment? The buyers are listed as hedge fund managers, foreign and domestic; Russian oligarchs; Chinese apparel and airline magnates. And increasingly, to use a repeated Times term, a “mystery buyer,” often shielded by a limited liability company. This is not the benevolent “gentrification” that Michael Bloomberg seemed to have had in mind but something more in the tradition of the king’s hunting preserves, from which local peasants were banned even if they were starving and the king was far away. Or, to use a more urgent analogy, these areas are now the dead zones of New York, much like the growing oxygen-depleted dead zones of our oceans and lakes, polluted with pesticide runoff and deadly algae blooms.

Kevin Baker

41 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I'm so excited! My buddy and I just installed a new display unit in my booth at Woolworth Walk. I'm really fortunate to have generous friends willing to take time out of their day to help me build my display. Thank you, Dave and Stan ! . . . #woolworthwalk #artdisplay #ceramics #pottery #handmade #craterglaze #maker #avlartist #asheville #art #selfemployed #flowervases (at Gerton, North Carolina) https://www.instagram.com/p/CNV8SzujRBa/?igshid=1g5gh76xbgq35

#woolworthwalk#artdisplay#ceramics#pottery#handmade#craterglaze#maker#avlartist#asheville#art#selfemployed#flowervases

1 note

·

View note

Link

(full article under cut:)

The scariest day of Maria Del Carmen’s life started with a phone call that initially cheered her up.

A native of Mexico, she has spent the last 24 years as a housekeeper in Philadelphia and had a dozen regular clients before the pandemic began. By April, she had three. Food banks became essential to feeding herself and her three children. To earn extra money, she started selling face masks stitched on her sewing machine.

So in mid-August, when a once-regular client — a pair of professors from the University of Pennsylvania and their children — asked her to come and clean, she was delighted. No one was home when she arrived, which seemed like a wise precaution, given social distancing guidelines. What struck her as odd were the three bottles of Lysol on the dining room table. She had a routine at every home, and it had never involved disinfectant.

Ms. Del Carmen started scrubbing, doing laundry and ironing. After a few hours, she stepped outside to throw away some garbage. A neighbor spotted her and all but shrieked: “Maria, what are you doing here?!” The professors and their children, the neighbor said, had all contracted the coronavirus.

“I was terrified,” Ms. Del Carmen recalled. “I started crying. Then I went home, took off all of my clothing, showered, got in bed, and for the next night and the next day, I waited for the coronavirus.”

She never got sick, but she still is livid. At 58 and, by her account, overweight, she considers herself at high risk. That is why she never took off her mask while cleaning that day — diligence she thinks might have saved her life.

“There are a lot of people who don’t want to disinfect their own homes,” she said, “so they call a housekeeper.”

The pandemic has had devastating consequences for a wide variety of occupations, but housekeepers have been among the hardest hit. Seventy-two percent of them reported that they had lost all of their clients by the first week of April, according to a survey by the National Domestic Workers Alliance. The fortunate had employers who continued to pay them. The unlucky called or texted their employers and heard nothing back. They weren’t laid off so much as ghosted, en masse.

Since July, hours have started picking up, though far short of pre-pandemic levels, and often for lower wages.

“We plateaued at about 40 percent employment in our surveys of members,” said Ai-jen Poo, executive director of the alliance. “And because most of these people are undocumented, they have not received any kind of government relief. We’re talking about a full-blown humanitarian crisis, a Depression-level situation for this work force.”

The ordeal of housekeepers is a case study in the wildly unequal ways that the pandemic has inflicted suffering. Their pay dwindled, in many cases, because employers left for vacation homes or because those employers could work from home and didn’t want visitors. Few housekeepers have much in the way of savings, let alone shares of stock, which means they are scrabbling for dollars as the wealthiest of their clients are prospering courtesy of the recent bull market.

In a dozen interviews, housekeepers in a handful of cities across the country described their feelings of fear and desperation over the last six months. A few said the pain had been alleviated by acts of generosity, mostly advances for future work. Far more said they were suspended, or perhaps fired, without so much as a conversation.

Scrubbing a fluffy little dog named Bobby

One of them is Vicenta, a 42-year-old native of Mexico who lives in Los Angeles, and who, like many contacted for this article, did not want her last name used because she is undocumented.

For 10 years, she had earned $2,000 a month cleaning two opulent homes in gated communities in Malibu, Calif. This included several exhausting weeks in 2018, when fires raged close enough to cover both homes in ash. Three times a week, she would visit both houses and scrub ash off floors, windows, walls and, for one family, a fluffy little dog named Bobby.

Vicenta received nothing extra for the added time it took to scour those houses during the fires. She would have settled for a glass of water, she said, but neither family offered one.

“It was incredibly hot, and my mouth and throat were really sore,” she recalled. “I should have seen a doctor, but we don’t have health insurance.”

If Vicenta thought her years of service had banked some good will, she was wrong. Early in May, both families called and left a message with her 16-year-old son, explaining that for the time being, she could not visit and clean. There was some vague talk about eventually asking her to return, but messages she left with the families for clarification went unreturned.

“Mostly, I feel really sad,” Vicenta said. “My children were born here, so they get coupons for food, but my husband lost his job as a prep cook in a restaurant last year and we are three months behind on rent. I don’t know what will happen next.”

Housekeepers have long had a uniquely precarious foothold in the U.S. labor market. Many people still refer to them as “the help,” which makes the job sound like something far less than an occupation. The Economic Policy Institute found that the country’s 2.2 million domestic workers — a group that includes housekeepers, child care workers and home health care aides — earn an average of $12.01 an hour and are three times as likely to live in poverty than other hourly workers. Few have benefits that are common in the American work force, like sick leave, health insurance, formal contracts or protection against unfair dismissal.

‘A treadmill life’

This underclass status can be traced as far back as the 1800s, historians say, and is squarely rooted in racism. Domestic work was then one of the few ways that Black women could earn money, and well into the 20th century, most of those women lived in the South. During the Jim Crow era, they were powerless and exploited. Far from the happy “mammy” found in popular culture like “Gone With the Wind,” these women were mistreated and overworked. In 1912, a publication called The Independent ran an essay by a woman identified only as a “Negro Nurse,” who described 14-hour workdays, seven days a week, for $10 a month.

“I live a treadmill life,” she wrote. “I see my own children only when they happen to see me on the streets.”

In 1935, the federal government all but codified the grim conditions of domestic work with the passage of the Social Security Act. The law was the crowning achievement of the New Deal, providing retirement benefits as well as the country’s first national unemployment compensation program — a safety net that was invaluable during the Depression. But the act excluded two categories of employment: domestic workers and agricultural laborers, jobs that were most essential to Black women and Black men, respectively.

The few Black people invited to weigh in on the bill pointed out the obvious. In February 1935, Charles Hamilton Houston, then special counsel to the N.A.A.C.P., testified before the Senate Finance Committee and said that from the viewpoint of Black people, the bill “looks like a sieve with the holes just big enough for the majority of Negroes to fall through.”

The historian Mary Poole, author of “The Segregated Origins of Social Security,” sifted through notes, diaries and transcripts created during the passage of the act and found that Black people were excluded not because white Southerners in control of Congress at the time insisted on it. The truth was more troubling, and more nuanced. Members of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration — most notably, the Treasury secretary, Henry Morgenthau Jr. — persuaded congressional leaders that the law would be far simpler to administer, and therefore far more likely to succeed, if the two occupations were left out of the bill.

In the years that followed, Black domestic workers were consistently at the mercy of white employers. In cities like New York, African-American women lined up at spots along certain streets, carrying a paper bag filled with work clothes, waiting for white housewives to offer them work, often for an hour or two, sometimes for the day. A reporter, Marvel Cooke, and an activist, Ella Baker, wrote a series of articles in 1935 for The Crisis, the journal of the N.A.A.C.P., describing life in what they called New York City’s “slave markets.”

The markets’ popularity diminished in the ’40s after Mayor Fiorello La Guardia opened hiring halls, where contracts were signed laying out terms for day labor arrangements. But in early 1950, Ms. Cooke found the markets in New York City were bustling again. In a series of first-person dispatches, she joined the “paper bag brigades” and went undercover to describe life for the Black women who stood in front of the Woolworths on 170th Street.

“That is the Bronx Slave Market,” she wrote in The Daily Compass in January 1950, “where Negro women wait, in rain or shine, in bitter cold or under broiling sun, to be hired by local housewives looking for bargains in human labor.”

That same year, domestic work was finally added to the Social Security Act, and by the 1970s it had been added to federal legislation intended to protect laborers, including the Fair Labor Standards Act. African-American women had won many of those protections by organizing, though by the 1980s, they had moved into other occupations and were largely replaced by women from South and Central America as well as the Caribbean.

A total lack of leverage

Today, many housekeepers are undocumented and either don’t know about their rights or are afraid to assert them. The sort of grass-roots organizations that tried to eradicate New York City’s “slave markets” are lobbying for state laws to protect domestic work. Nine states have domestic workers’ rights laws on the book. Last summer, Senator Kamala Harris introduced the Domestic Workers Bill of Rights, which would guarantee a minimum wage and overtime pay, along with protections against racial discrimination. The bill has yet to pass, and if it did, labor advocates and historians say it would merely be a beginning.

“It’s important to get a federal bill, but it leaves unanswered the question of enforcement,” said Premilla Nadasen, the author of “Household Workers Unite” and a professor of history at Barnard College. “The Department of Labor is overextended and it tends not to check up on individual employers. The imbalance of power between employer and employee has been magnified by the pandemic because millions of people are now looking for work. And xenophobic rhetoric has made women more fearful of being deported.”

The pandemic has laid bare not just the vulnerability of housekeepers to economic shocks but their total lack of leverage. Several workers said they had clients who would not let anyone clean who has had Covid-19; others know clients who will hire only Covid survivors, on the theory that after their recovery, they pose no health risk. Housekeepers are often given strict instructions about how they can commute, and are quizzed about whether and how much they interact with others. But they have no idea whether their employers are taking similar precautions. Nor, in many cases, are they accorded the simple decencies that are part of formal employment.

“It would be nice to have at least two days’ notice when someone cancels on you, either to let you know or compensate you for your time,” said Magdalena Zylinska, a housekeeper in Chicago who helped lobby for a domestic workers’ rights bill that passed in Illinois in 2017. “I think a lot of people don’t realize that if I don’t work, I don’t get paid and I still have to buy food, pay bills, utilities.”

Ms. Zylinska emigrated from Poland more than 20 years ago and has yet to get a week of paid vacation. The closest she came was in 1997, when a couple handed her $900 in cash, all at once — for work she’d just finished, work she would soon do, plus a holiday bonus.

“The couple said, ��Merry Christmas, Maggie,’” she said. “I remember counting that money four times.”

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tales of Ike and Tina Turner:

The world’s greatest heartbreaker

Tina Turner performs on stage with Ike and Tina Turner in Amsterdam, Netherlands in 1971. Gijsbert Hanekroot/Redferbs.

— BEN FONG-TORRES Published 14/OCT/1971

Walk into what, from the outside, looks to be another well-paid, well-kept home in suburban Inglewood, California, and you’re hit: a huge, imperial oil painting of Ike and Tina Turner, dressed as if for a simple, private wedding, circa 1960, modest pompadour and formal mink. A thriller? The killer, honey…

Also in the foyer, under the portrait, a small white bust of John F. Kennedy. Next to him, the Bible, opened to Isaiah 42 – A New Song to the Lord. The smell is eucalyptus leaves and wet rocks; the sound is water, bubbling in one of several fish tanks and, over in the family room, splashing, programmed, is a waterfall.

Two trim young housekeepers stir around the kitchen; dinner is cooking at 4p.m. Ike is asleep upstairs, and Tina is out with a son at football practice. But you cannot just plop down somewhere, adjust yourself, and be comfortable. Next to the waterfall there’s a red velvet sofa, designed around a coffee table in the shape of a bass guitar. Or, in the blue room, the blue couch, whose back turns into an arm that turns into a tentacle. Above that, on the ceiling, is a large mirror in the shape of a jig-saw puzzle piece, and against one wall is a Zenith color TV, encased in an imitation ivory, whale-shaped cabinet.

(Tina, later, will say: “Ike did the house. It was Ike’s idea to have the TV in the whale shape. I thought, ‘Oh wow!’ I felt it was gonna look like the typical entertainer’s house, with the stuff not looking professional. But everything turned out great. I’m very proud of it.”)

It is very personal, but there are all these mail order touches. The neo-wood vertical frame with four bubbles to hold color pictures of the Turners’ four sons. The JFK bust. On the wall, over a mantel, a large metallic Zodiac sunburst, with no clock in the middle. Also, a Zodiac ash tray atop the guitar-shaped table. (Ike showed his refurnishing job off to Bob Krasnow of Blue Thumb Records one day last year, and Krasnow remarked: “You mean you actually can spend $70,000 at Woolworth’s?”)

Atop a white upright piano complete with gooseneck mike, there’s the gold record – not “A Fool in Love,” or “It’s Gonna Work Out Fine,” or “I Idolize You,” but, rather, “Come Together,” the single on Liberty, their seventh or eighth label in ten years. And next to that, some trophies—a couple that the kids have earned, and a couple that Tina has earned. To the sweetest wife and mother, Tina Turnaer. Love’s Yea. Ike Turner and Your Four Sons. Another, larger one, Olympiad, with a small gold-plated angel holding a torch above her, hara-kiri:To Tina Turner. The World’s Greatest Heartbreaker 1966. Love Ike Turner.

Tina’s not back – half an hour late – and now I’m down to the sunlit bookshelf in the corner. A neat junior edition of encyclopedias. A couple of novels – Crichton’s Andromeda Strain; Cheever’s Bullet Park. But the main line appears to be how-to’s, from Kahlil Gibran and astrology to a series of sharkskin suit-pocket hardbounds: How to Make a Killing in Real Estate, How to Legally Avoid Paying Taxes, and How to Scheme Your Way to Fortune. Atop the pile, a one-volume senior encyclopedia: The Sex Book.

***

Someone once called Tina “The female Mick Jagger.” In fact, to be more accurate, one should call Mick “The male Tina Turner.” After all, in 1960, Ike and Tina and the first of God knows how many Ikettes began doing their revue, and, as Tina tells it, “Ike used to move on stage. He was bow-legged and bow-hipped and when he moved from side to side, he had an effect he used to do with the guitar, and I used to do that, ’cause I idolized him so. Before I fell in love with him I’d loved him. We were very close friends. I thought there was nobody like Ike, so I wanted to be like Ike. I wore tight dresses and high heels, and I still moved, and that’s where the side-step came from.”

Philip Agee, who was 17 when he first saw them in 1960 in St. Louis, became such a fan that he has put out a book on them – for a seminar course in printing at Yale. Tina Pie is a collection of the colorations of Ike and Tina’s romance and career, tawny browns and flashy reds and moanful yellows and hurtful blues. Silkscreening the act through the dark years and into the fast ones, with even remembrances from Tina’s mother, or various of Phil Agee’s friends and fellow-worshippers.

“Tina came out and up on the stage. Nobody screamed or fainted. We were just real glad to see her. She always wore sparkling dresses and very high-heeled shoes with no backs and holes in the toes. Sometimes she was pregnant, singing with her stomach stuck out, stomping her high-heeled shoes with stiff legs. They would sing special songs when you asked them. Everybody liked ‘A Fool in Love.’ ‘Staggerlee’ was my favorite. When Ike started slow, ‘When the night was clear and the moon was yellow, and the leaves came tumbling down…’ by the time ba-da, ba-da, ba-doo ended, everybody was out on the floor. During their breaks the jukebox played again. Tina disappeared and the men sat at card tables near the stage drinking with their blonde girlfriends. When the men started playing again, Tina appeared for the second show. By 11 it was over. Pat’s dad picked us up and drove me home. We went every Tuesday while they were in St. Louis. “Tina Turner’s part Cherokee and so’s my Mom, so so am I.” — Kathy Klein

By 1966, there was more practiced flash. You learn what works. The Ikettes came storming out of the wings in a train formation, in mini-skirted sequins, haughty foxes thrusting their butts at you and then waving you off with a toss of their long whippy hair. Tina came out, eyes flashing until she became a fire on the stage. And across Broadway, there’s your Motown act, the Marvellettes in their matching long evening gowns or the Tops in pink velvet, doing soul-hula, singing through choreographed smiles. Tina spitssex out to you. And Mick Jagger:

Before that breakthrough tour with the Rolling Stones in 1969, Ike and Tina had worked with them in England in 1966. “Mick was a friend of Phil Spector,” says Tina. “And the time we cut ‘River Deep Mountain High,’ Mick was around. [This is at Gold Star, Phil’s favorite studio in Los Angeles] I remembered him but I never talked to him. He’s not the type to make you feel you could just come up and talk to him. Mick, I guess, thought the record was great, and he caught our act a couple of times. Mick wasn’t dancing at the time…he always said he liked to see girls dance. So he was excited about our show, and he thought it’d be different for the people in England.

“I remember I wasn’t mingling too much – Ike and I were having problems at the time, and we stayed mad at each other – but I’d always see Mick in the wings. I thought, ‘Wow, he must really be a fan.’ I’d come out and watch him occasionally; they’d play music, and Mick’d beat the tambourine. He wasn’t dancing. And lo and behold, when he came to America, he was doing everything! So then I knew what he was doing in the wings. He learned a lot of steps and I tried to teach him like the Popcorn and other steps we were doing, but he can’t do ’em like that.He has to do it his way.”

“River Deep Mountain High.” To hear that song for the first time, in 1967, in the first year of acid-rock and Memphis soul, to hear that wall falling toward you, with Tina teasing it along, was to understand all the power of rock and roll. It had been released in England in 1966 and made Number Two. In America, nothing. “It was just like my farewell,” Phil Spector says. “I was just sayin’ goodbye, and I just wanted to go crazy for a few minutes – four minutes on wax.”

Bob Krasnow, president of Blue Thumb, knew Ike and Tina from their association with Warner Brothers’ R&B label, Loma, in 1964. He was an A&R man there. “Spector had just lost the Righteous Brothers,” he recalls, “and at the same time, Ike was unhappy,” having switched to Kent Records.

“Spector’s attorney Joey Cooper called and said Phil wanted to produce Tina—and that he was willing to pay $20,000 in front to do it! So Mike Maitland [then president at Warners] gave them their release, and they signed with Philles.

“Watching Phil work was one of my greatest experiences,” says Krasnow. It was indeed a special occasion. Only “River Deep” was cut at Gold Star; the other three Spector productions were at United. (There was only one Philles LP ever made with Ike and Tina, which was finally re-released last year by A&M.) And Ike didn’t attend.

“Dennis Hopper did the cover on that LP. He was broke on his ass in Hollywood and trying photography. He said he’d like to do the cover. He took us to this sign company, where there was this 70-foot high sign for a movie, with one of those sex stars – Boccaccio ’70 or something. And he shot them in front of that big teardrop. Then the gas company, had a big sign, and Hooper took them there and shot them in front of a big burner.”

On stage, there may be reason to compare Tina Turner to Mick Jagger; Tina, in fact, is more aggressive, more animalistic. But it is, indeed, a stage:

“I don’t sound pretty, or good. I sound, arreghh! Naggy. I can sound pretty, but nobody likes it. Like I read some article in the paper that Tina Turner had never been captured on records. She purrs like a kitten on record, but she’s wild on stage. And they don’t like a record like ‘Working Together.’ I love that record. I love that River Deep Mountain Highalbum, but nobody likes me like that. They want me sounding all raspy…I have to do what Ike says. “My whole thing,” she once said, “is the fact that I am to Ike – I’m going to use the term ‘doll’ – that you sort of mold… In other words, he put me through a lot of changes. My whole thing is Ike’s ideas. I’ll come up with a few of them, but I’m not half as creative as Ike.”

***

The world’s greatest heartbreaker drives up in her Mercedes sedan and strides in, all fresh and breezy in a red knit hot pants outfit, third button unbottoned, supple legs still very trim at age 32,charging onto 33. (“Everyone thinks I’m in my forties, but I was only around 20 when I started. Born November 26, 1939,” she says, very certain.)

Tina’s hair is in ponytails, tied in brown ribbons; she is wearing brown nail polish and red ballet-type slippers. Here in the living room, of her $100,000 house, she is trying to paint a portrait of the offstage, in-home Tina Turner. There are four bedrooms, she says, four baths, and, let’s see now…13 telephones.

Additional phone cables are employed in the closed-circuit TV system, a system like the one in Ike’s studios less than a mile away. There, Ike can sit in his office and push-button his way around the various studios, the writers’ room, the entrances, the hallways. Just recently, he was laughing about the time he punched up the camera scanning the bedroom in the private apartment he keeps there, and what did he and the people around him (Tina was at home) see but some heavy fucking going on, one of his musicians and a groupie. And everyone’s lapping it up, and finally, when the sideman is caressing one of his nightstand’s firm-nippled breasts, Ike’s bodyguard springs out of the office, and the next you see him, he is piling into the bed, over most of that same station…

Only Schwab Has $0 Commissions and a Satisfaction GuaranteeAt Schwab, $0 Online Stocks, ETFs, and Options Commissions are backed by 45 years of innovation, award-winning service, and a Satisfaction Guarantee.Ad by Charles Schwab See More

But later. Tina Turner is trying to paint a picture here. “I just got rid of the housekeeper. I get housekeepers and they sort of do just things like vacuuming and dusting, and nothing else is done—like the mirrors—and I’m a perfectionist, and that would never be. People think I’m probably one of those that lounge around, but I’m always on my knees—I do my own floors ’cause no one can please me. When I was in the eighth grade I started working for a lady in Tennessee keeping her house; she more or less taught me what I know about housework.”

Tina also tries to do most of the cooking, even if she usually does report to the studios around 4 PM to do vocals. She also likes to do gardening. “Every now and then I get out and turn the dirt…but now I’ve started writing, and Ike, every time I turn around, he says, ‘Write me this song.’ So I went out and bought some plants and when I was in the hospital I got a lot of plants that I really love, and I sort of take care of them like babies.”

“Ike is a very hard worker,” a friend is saying. “He’s such a driver. Last winter Tina was sick with bronchial pneumonia, 104 temperature, in the hospital with her body icepacked to bring the temperature down. And Ike was visiting, and he was going, ‘You get out and sing, or you get out of the house!'”

Tina doesn’t discuss such things, even if her talk is often punctuated by references to Ike as the manager, the brains, the last word; despite his back-to-the-audience stance on stage. But in Tina Pie, Phil Agee’s book, there’s a piece of conversation backstage between Tina and one of Phil’s friends: Pete: I thought maybe you wouldn’t be here tonight. Tina: No, I never miss a performance. The doctor came to the hotel today, brought a vaporizer and that helped it a lot. I haven’t coughed anything up today – so I was kind of worrying if it was okay. I always go on. Whatever’s bothering me – I don’t care how bad it is – I drop it when I go on stage. I hadn’t coughed up anything today. You know that kind of hypnosis – I don’t know what it’s called – where you induce yourself into a trance? (Tina’s friend): Self-hypnosis. Tina: Yeah, that’s it. I hypnotize myself, and I forget the cold and stuff.

***

“Dope?” Bob Krasnow repeats the question, only in a softer voice. “Let me close the door a minute.” (A few weeks before, I asked an ex-Ikette about Ike Turner and sex. “Sex? Oh, my god, that’s another volume,” she’d said. “I’ll have to get a cigarette on that one!”)

Krasnow: “Tina is so anti-dope I can’t tell you. She’s the greatest woman I’ve ever known, outside of my wife. She has more love inside her body than 100 chicks wrapped up together. And she’s so straight, it’s ridiculous. “As for Ike…Ike was not into dope at all until three, four years ago. One night in Vegas we were sitting around and got started talking about coke. He didn’t care about it, and I said – and Ike, you know, is like 40 or so – and I said, ‘One thing that’s great about coke is you can stay hard – you can fuck for years behind that stuff.’ That’s the first time Ike did coke.”

Krasnow can’t help but continue. “That night he made his first deal – bought $3,000 of cocaine from King Curtis, and he bought it and showed me, and I laughed and said, ‘That’s no coke; that’s fucking Drano!’ Since then, he’s learned.”

What – to lighten up on drugs?

“No – to tell what good coke is and what bad coke is.”

Krasnow worked with James Brown at King for years before he joined Warners and signed Ike and Tina to Loma. His evaluation: “Ike is 10 times a bigger character than James Brown. And they’re both fucking animals. How can I put this? Say, whatever you can do…they can do 10 times as much. And Ike – he’s always putting you to the test.

“What I like best about Ike is also what I hate: He’s always on top of you.”

“I find him one of the most fascinating people I’ve met,” says Jeff Trager, who did promotion work at Blue Thumb. “If he knows you he can be real warm, and do whatever he can for you. There’s just no limit to Ike Turner. He’d carry around $25,000 in cash in a cigar box – with a gun. He’d drive around town, man, sometimes to Watts, sometimes Laurel Canyon, in his new Rolls Royce to pick up coke. And he is real sinister-looking.”

“In Las Vegas,” says Krasnow, “I brought some friends into the dressing room, and Ike pulled out this big .45 – just putting them on. Another time he came into the front room at Blue Thumb and threw $70,000 on the floor, in cash, and dared anyone to touch it. Just to blow everybody’s mind.”

“Krasnow and Ike are both crazy,” says Trager. “Ike would storm into the office with a troop of people, six-foot chicks, a bag of cocaine. Really, really crazy. He always came in. He loved Blue Thumb, and he was always saying he’d come back. Krasnow says he couldn’t afford him now.”

Krasnow produced both their Blue Thumb albums and brought “I’ve Been Loving You Too Long” to Turner.

“He hated Otis Redding,” Krasnow says. “He just didn’t think Otis had it.” The Ike and Tina version sold some half million copies. Blue Thumb was also a good showcase of Ike Turner’s fluidity as a blues guitarist, and of the flexibility of the Ike and Tina sound – from “Dust My Broom” and “I Am a Motherless Child” to the stark raving “Bold Soul Sister.”

Ike Turner, who places “River Deep” up next to “Good Vibrations” as his two favorite records, says the Spector production didn’t get airplay because the soul stations said “too pop” and the white stations said “too R&B.”

“See, what’s wrong with America,” he told Pete Senoff, “is that rather than accept something for its value…America mixes race in it. Like, you can take Tina and cut a pop record on her – like ‘River Deep, Mountain High.’ You can’t call that record R&B. But because it’s Tina… But I can play you stuff like Dinah Washington on Tina. I can play you jazz on Tina. I can play you pop on Tina. I can play you gutbucket R&B on Tina like we have on our Blue Thumb record…really blues. I can play you that stuff, then I could play you the Motown stuff.”

Ike and Tina had a showcase at Blue Thumb, but no cross-market success. “Bold Soul Sister” went to number one at KGFJ, the black station in L.A., but Jeff Trager remembers, the program director at light, white KRLA refused to play it. “No matter what. I asked him, ‘What if it went to number one?’ and he said ‘I don’t care; I’ll never play it.'” Whether too R&B or what, the program director at KFRC, the Bill Drake station in San Francisco, wouldn’t play “I’ve Been Loving You Too Long,” which Krasnow, its producer, called a “pop record.” KFRC had to be forced – by its sales – to put the song on the playlist.

What finally carried Ike and Tina through was the 1969 Rolling Stones tour, where the revue broke out with “Come Together,” in its own raw style, Tina snake-snapping across the stage, punching out the John Lennon lyric. Raves everywhere, and the mass magazines were stung to attention. Playboy and Look ended up using the same phrase to characterize Tina’s entrance: “like a lioness in heat.” Vogue did a photo spread. And Ike and Tina got booked into Vegas and both Fillmores. Liberty Records began talking big money, so big that even Krasnow encouraged Turner to go to them as an exclusive artist. “We didn’t have a contract, anyway,” says Krasnow. “It was just on a piecemeal basis.” That’s when Ike refurnished his $100,000 home and began building his lavish studios. Tina is sitting in the “game room” of the studios. The move to interpreting white rock and roll, she says, was quite natural. “We went to a record shop in Seattle, Washington, and someone was buying ‘Come Together,’ and I said, ‘Oh, Ike, I gotta do it on stage, I love that record.’ That’s the thing I think of – the stage – because it’s action, you know. And ‘Honky Tonk Woman,’ that’s me. And then people came to us and said, ‘You gotta record that song, it’s so great.’ And we said ‘What’s so great about it; we’re doing it just like the Beatles or the Rolling Stones,’ and they said ‘No, you have your own thing about it.’ So when we cut the album, we were lacking a few tunes, so we said ‘Well, let’s just put in a few things that we’re doing on stage. And that’s how ‘Proud Mary’ came about. I had loved it when it first came out. We auditioned a girl and she had sung ‘Proud Mary.’ This is like eight months later, and Ike said, ‘You know, I forgot all about that tune.’ And I said let’s do it, but let’s change it. So in the car Ike plays the guitar, we just sort of jam. And we just sort of broke into the black version of it. It was never planned to say, ‘Well, let’s go to the record shop, and I’d like to record this tune by Aretha Franklin’…it’s just that we get it for stage, because we give the people a little bit of us and a little bit of what they hear on the radio every day.

“My mother – her radio was usually blues, B.B. King and all. But rock and roll was more me, and when that sort of music came on, I never could sit down. I’ve always wanted to move.” Tina gave a slightly – shall we say – different account to Changes magazine: Tina: I guess ‘way before the Stones asked us to tour with them, Ike started to get into the hard rock thing, dragging me out of bed to listen to this or that, and at 4 o’clock in the morning. Ike: She didn’t like rock. Tina: Finally, he said ‘You going to have to sing it, so you may as well like it.’ So I started to listen to rock.

***

“They are really making it now,” says Krasnow. “Really. Everytime he plays a place – like last week, Carnegie Hall – it’s sold out a week before. And everybody’s raving about the show.”

But there was a time…”I got pissed at him ’cause we worked our asses off to get him on the Andy Williams Love show. We had dinner afterwards, and I said, ‘This is it! You’ve made it, man!’ He was back playing the bowling alley the next night. I kept saying, ‘Why play for $1,000 a night when you can get $20,000 now?’ I mean, he was just touring himself out.” Ike himself says, “It doesn’t matter to me; we’ve got a living to make.” Recently, he has relaxed the road pace, from six nights a week all year to two or three nights a week. Ike and Tina are now regularly on TV – on variety shows, talk shows, and specials; they were in Milos Forman’s Taking Off and Gimme Shelter, and they helped celebrate Independence Day this year in Ghana. Soul to Soul. And what is now apparent is that in Africa or in Hollywood, in bowling alleys or in the Casino Lounge of the Hotel International, the Ike and Tina Turner Revue, with the Ikettes and the Kings of Rhythm (nine pieces plus Ike) is pretty much the same show: The band member doing the introductions and shameless album plugs; the Kings warming up with a couple of Motown-type power tunes, followed by the Ikettes singing “Piece of My Heart” or “Sweet Inspiration,” then Tina running on, churning through “Shake Your Tail Feather,” then saying a hearty hello and promising “soul music with the grease.”

***

Tina’s recitations and spoken paeans – and Ike’s wise-ass, not-quite-inaudible cracks, are all pre-greased…Mama don’t cook no dinner tonight, ’cause Daddy’s comin’ home with the crabs…

When Tina sings, “I been lovin’ you…too long…and I can’t stop now,” bossman Ike invariably croons, “‘Cause you ain’t ready to die…”

The Otis Redding song is the show-stopper. Back in ’67, Tina was simply breathing heavily over the instrumental passage; by ’69, she was touching the tip of the microphone with both sets of fingers oh, so gently. Now, of course, it’s a programmed gross-out, with Ike slurping and slushing and Tina rigid over the mike doing an unimpressive impression of an orgasm while Ike slams the song to a close, saying “Well, I got mine, I hope you got yours.”

In 1969 it was a solid salute to sex as a base for communication. Now, the subtleties gone, it’s just another request number to keep the crowd happy. “We cut the song,” says Tina, “and Ike kept playing the tune over and over and I had to ad lib, so I just did that – just what comes into your head. So we started doing it on stage. How could I stand on stage, I felt, and say ‘Oh baby, oh baby, uhh’—I’m just going to stand there, like an actress reading the script without any emotion? So I had to act.

“What I did on the Rolling Stones tour was only what had matured from the beginning. I don’t think it can go any further, because it’s, as they say in New York, it’s getting pornographic. I agree, because like now Ike has changed words, which makes it obvious what that meant when we first started doing it. I was thinking it meant sensually but not sexually.

Sometimes he shocks me, but I have to be cool. Sometimes I want to go, ‘Ike, please.’ I start caressing the mike and he goes, ‘Wait ’til I get you home,’ and I feel like going, ‘Oh, I wish you wouldn’t say that.’ Everything else I feel like I can put up with, but not that. But like I can’t question Ike because everything that Ike has ever gotten me to do that I didn’t like, was successful.

“I think in the early Sixties it would have really been out of bounds – like, I probably would have been thrown off the stage. But today, it’s what’s happening. That’s why I can get by with it.”

***

From Tina Pie, this strange crossfire: “… It could be nice but it would probably turn out awful – especially with that dirty ol’ Ike hounding me. I sat through the first half of the second show with him and he kept telling me he want to give me a fit and just ’cause he had Tina didn’t mean he couldn’t want me, too. He’s got the greatest skin going but that’s about it. -Melinda, New York City

Melinda Who? -Ike Turner, New York City

***

Tina is giving me a tour of Ike’s new main studios – the master control room with the $90,000 board featuring the IBM mix-memorizer (a computer card gives an electronic readout on the mix at whichever point the tape is stopped), a second studio marked STUDIO A (Ike Turner’s, can you guess, is STUDIO AA), a writers’ room, business offices for his various managers and aides, a playroom furnished with a pool table, Ike’s own office, and, inevitably, Ike’s private apartment suite.

Again, it is disgusting, flowers chasing each other up the wall, a Cinerama mural of a couple in embrace next to the breakfast table and refrigerator. Again, sofas, of Ike’s own design, with hard-on arms. White early American drapings and chairs, and a draped, canopied bed so garish that Tina turns to Ike and says, “Can I tell ’em what we call this room? We call it ‘the Whorehouse.'”

There’s a double-door air closet at the entrance to Ike’s private quarters, where he spends so many nights, “because of all the work to be done.” This is the Trap. You bust into Bolic Sound, and all the doors are automatically locked, leading you down the hall, into the stairwell in front of the apartment. The only way to open the door there is by dialing a secret telephone number. And the only word that can get to you will come from above you. Ike’s got a TV camera there, too.

Ike Turner has moved around from label to label for 10 years. Ike and Tina began with “A Fool in Love,” which Ike cut with Tina when the original singer for his composition didn’t show up at a date. That record hit in 1960 and was on a midwest R&B label, Sue. It was followed by “It’s Gonna Work Out Fine,” but the head of Sue delayed its release so long – that he sent the master back three times, said Ike – that he split in 1964, going to Warner Bros.’ fledgling R&B label, Loma, for a pair of live LPs recorded in Ft. Worth and Dallas by “Bumps” Blackwell, now manager of Little Richard.

1963 to 1966 was a dark period for the Revue – they made what they could on the road, and they had no hit records – and Loma records were hard to find. Ike then took his act to Kent, a label he’d worked for in earlier days when he traveled the South scouting and recording, on a cheap Ampex tape recorder, bluesmen like B.B. King and Howlin’ Wolf. This time around, he managed a hit for the Ikettes, “Peaches and Cream.” But, he said, “They tried to steal the Ikettes. They sneaked around and tried to buy the girls from under me.”

Then it was Spector, won over by Ike and Tina’s work as a substitute act in the rock and roll film, T’N’T Show. But after “River Deep” bombed, said Ike, “he got discouraged and went down in Mexico making movies.” Phil recommended Bob Crewe as a producer, a single didn’t hit, and they moved to an Atlantic subsidiary, Pompeii Records. “We were lost among all of Atlantic’s own R&B stuff,” Ike said, and that’s when he ran into Krasnow. With no contract ever signed with Blue Thumb, Ike actually made a deal with United Artists/Liberty in mid-1969, before the Stones tour, through their New York-based R&B label, Minit.

“Spector gave Ike an absolute guarantee of hits forever,” says Bud Dain, then general manager at Liberty. What Minit promised was a $50,000 a year guarantee “plus certain clauses – a trade ad on every release, sensitive timing of releases – but Minit was a mistake. They defaulted on the contract, and Ike was free to break the contract.” Then Ike and Tina toured with the Stones, and the next time Ike talked with Liberty, Liberty was talking about $150,000 a year guarantee, for two albums a year. Ike signed in January, 1970. “The first LP was Come Together, in May,” said Dain. “Now Ike wanted to build his own studios. The option came up again in January, 1971. The album sold well, but we couldn’t exercise the option unless he’d sold 300,000. And he only had one album out that year. But he needed $150,000, and Al Bennett [president at Liberty] believed in him. We gave him the money.”

With the second advance, Ike’s studios were well underway, and he got another hit record, the single on “Proud Mary.” “Then he came in – he needed another $150,000. He got that in June. So there’s a total of $450,000 in advances.”

And that’s why United Artists may yet be Ike and Tina’s final home. Ike Turner must produce those two albums a year, and UA has no choice but to promote its ass off.

***

Ike’s head is on one woman’s lap, his knee-socked feet on another’s. His thin frame is blanketed by a trench coat, a sleeping bridge across the sofa in the dressing room. Tina has her back to them. She’s working her hair into shape for the second show this Friday night, and Ike’s getting the only rest he’s gotten all day. And after the second show, he’ll jump off the revolving stage of the Circle Star Theater in San Carlos, then back to the nearby San Francisco Airport to return to his studios to cut instrumental tracks the rest of the night and into the day, then back up to San Francisco and to the Circle Star mid-Saturday evening. In the hallway, after the second show Friday, he stops long enough to give you a solid shoulder grab – a football coach’s kind of friendly gesture – and a warm hello. He turns to the zaftig lady photographer nearby, glancing right through her tangle of cameras and giving her the onceover. He asks if maybe she wouldn’t fly down with him. “What? You got a boyfriend?”

“This is the critical point of our career; I can’t lighten up now,” he says, and is off to the airport. At 2:30 in the morning, Tina – who doesn’t return to L.A. with him – shows up at a banquet room in her hotel for a photo session. The photographer’s assistant asks, “What’s your advice for people getting into the business?”

Tina, at 3 a.m., is serious: “Have some kind of business knowledge.”

In the dressing room between shows, she had said, “I’m glad I got Ike, ’cause I would’ve quit years ago. I probably would’ve worked for promoters and not get paid. Our policy is to have our money before we go on stage. Even if it’s for the President.”

Just before the Stones tour, Ike and Tina were booked for the Ed Sullivan Show, in September, 1969. “And he got his money in front,” says Jeff Trager. Most promoters say 50 percent deposit, the rest after the show. “So Sullivan comes up to Ike before the show, and Ike hasn’t got his guitar with him, and it’s showtime. Sullivan asks where his guitar is, and Ike tells Ed he needs ‘the key to the guitar,’ the key being the money.” Sullivan paid. “You have to protect yourself,” Tina is saying to the two women on the sofa with Ike.

Road manager Rhonda Graham, a stern, curt white woman, is seated nearby, in front of a rack full of Tina’s costumes and shoes. “In the early Sixties we went through that. If you don’t know these people, some of them just take the gate and leave.”

“Three, four years ago, they were playing a club,” Trager recalls, “and Rhonda had a cigar box at the door. And one dollar would go into the box, one dollar to the club. At Basin Street West he got cash all the time.” But if you are black and in the music business, you get burned until you either quit or learn. Turner learned, through all the different labels and beginning in the late Forties.

In junior high, he says, he’d decided to devote himself to “giving people music sounds that they could really dig, and pat their feet to. I’m not a very good speaker, so I try to express myself when I play.” Turner told Pete Senoff: “I started professionally when I was 11. The first group I played with was Robert Nighthawk, then Sonny Boy Williams. This was like back in 1948-1949. I went to Memphis in about 1952. That’s where I met Junior Parker, Willy Nix, Howlin’ Wolf. I was just playing with different groups all around – playing piano. From Junior Parker, I left Memphis and went to Mississippi, where I met the people from Kent and Modern Record Company. That’s when I started scouting for talent for them. That’s when I started recording B.B. King, Roscoe Gordon, Johnny Ace, Howlin’ Wolf. We were just going through the South and giving people there $5 to $10 or a fifth of whiskey while we recorded over a piano in their living rooms.