#which kind of sentence is it? is it after a preposition? is it this kind of subject or THIS kind of subject? is the moon in alignment?

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

16 year old X: ugh german cases are so difficult, i have to use a different ending or whatever depending where the noun is in the sentence?? i give up on this language

18 year old X: okay i'll study arabic, it has logical but relatively simple grammar!

arabic now:

#FIFTY FOUR FUCKING OPTIONS#for those curious: options are singular dual plural across the top#the three larger boxes are the three cases each of which change depending on masculine/feminine/broken plural#AND then each one is different for definite and indefinite#according to x#languages#x's adventures in arabic#and the most fun part is that most writing doesn't include the small vowels that differentiate these cases#so have fun figuring out if it's talking about two translators or a group of them!#oh and ALSO good luck with the rules for when to use each of them#which kind of sentence is it? is it after a preposition? is it this kind of subject or THIS kind of subject? is the moon in alignment?#and i almost forgot! verbs have a completely different set of cases and rules :))

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Diachronic change in Yuk Tepat

Yuk Tepat is often presented here as a fixed entity - “Classical Yuk Tepat” - but beneath that has undergone evolution like all languages. The following sentences both mean “A man I didn’t know came in.” The first represents the most archaic layer of old Tepat, and the second is a relatively modern colloquial version from the late Conciliarity period.

Ci niw yan-uk syow mi-yat ku hyew.

*[tsi niw ja nuk sju me jat ku hjew]

PAST enter person 1P REL NEG know to room

(Alternately: Ci niw yan syuk mi-yat ku hyew. (syuk = syu + =uk)

Hûq-khal yan i-wat ôl-yat mul nt’ôl-nyul hyew-iw.

[hɯʔ kʰal ja ni wɒ ɾl̩ jat mu ln̩ tl̩ nyɬ çø wiw]

one CLASS person of 1P PAST know NEG 3P PAST enter room CIS

Let’s unpack this. First, a couple of very notable things:

The modern sentence is much longer.

Only three words are the same in both sentences: yan, yat, hyew.

Digging deeper….

Ci was the normal particle expressing past tense in Old Yuktepat, but it has been replaced by ôl in the second sentence.

The second sentence begins with a subject noun phrase Hûq-khal yan i-wat ôl-yat mul, which is normal SVO word order. The equivalent subject noun phrase in the first sentence comes AFTER the verb. In archaic language, this is an acceptable ordering for INDEFINITE subject nouns (but actually, it would still have been unusual for a complex noun phrase like this).

The subject noun yan in the second sentence is modified by a numeral-classifier phrase hûq-khal ‘one.’ This kind of specification of number - such as ‘one’ for any old indefinite noun phrase - is more common in later Yuk Tepat.

The first person pronoun. In the first sentence, there is a clitic form -uk. In later Yuk Tepat, everything has been leveled to the invariable pronoun wat.

The subject contains a relative clause. In the first sentence, it is relativized by syow, in the second sentence it is relativized by i. I also means ‘of’ and has been generalized to all kinds of situations, while specific subordinating particles like syow - which is only used to relativize objects - have fallen out of use.

(Additionally, syow and -uk might occur together as a fused form syuk.)

The negative. The first sentence uses mi before the verb, the second sentence uses mul after the verb.

The second sentence contains a pronoun nat (contracted to nt) which follows the subject noun phrase, before the verb. Kind of like ‘The man I didn’t know, he entered the room.’

Niw and nyul ‘enter.’ Niw and nyul are the same verb basically. Niw is an older intransitive form. Most verb pairs of this sort have been leveled to only one form. In Yuk Tepat, the originally transitive form nyul has taken over everything.

The first sentence has a preposition ku ‘in, at, to.’ This is missing in the second sentence. ‘To’ is considered implicit in the verb nyul. Ku is no longer used except in fixed expressions.

The second sentence ends in a clitic -iw indicating motion toward the speaker. This is derived from the verb khiw ‘come.’

These examples are very different, but the reality may not be that extreme. Although only 3 words are identical, most words in either sentence are found in all stages of the language, although their usage may have shifted. For example past tense ci is still used, but it has a very archaic sound. It is used for DISTANT past, or in say, historical textbooks, but ôl is now the neutral past tense marker. Hence, either (written) sentence should be interpretable to someone from the other time period. Through this we also see one trend of the language’s evolution, that of reducing morphological variants to a single uninflected form.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

quantifier floating and differential object marking in japanese!! (??)

ok ok ok before you say sasha, not everyone has multiple degrees in linguistics, let ME just say, i bet you already know something about what i’m going to talk about here! so don’t be scared!! 全然怖くないから行こう!!

what is quantifier floating?

well, before we get to quantifier floating, let’s take a short detour to quantifiers themselves. you probably already know what these are even if you don’t know this particular name for them: it’s words like 二人 (ふたり), 1匹 (いっぴき), and 5冊 (ごさつ). you may have also heard these words referred to by the name classifiers (especially if you’ve studied a language like mandarin before). anyway, quantifiers are just words that specify an amount of something—in english, they’re words like “some” or “every.” easy!

ok, so what is japanese quantifier floating? compare these two sentences:

先生を二人探しています。

二人の先生を探しています。

if you had to guess, in which one of these sentences is 二人 “floating”? the first one, right? it’s just sort of sitting between を and the verb without any particle indicating what it’s doing there. so this is the phenomenon known as quantifier floating, and there is actually a slight difference between a floating quantifier and a quantifier attached pre-nominally with の, like in the second sentence.

what is differential object marking?

do you speak any spanish? how about hebrew? in these languages and others, there is a grammatical strategy available to speakers that allows them to distinguish between any old noun and nouns that are personally known or familiar to them. compare these two spanish sentences:

busco un profesor de japonés. = i’m looking for a japanese professor.

busco a un profesor de japonés. = i’m looking for this japanese professor...

in sentence 2, the preposition a has been inserted before the object un profesor, ‘a teacher.’ the function of this preposition is to indicate that the speaker already knows this particular professor, almost like saying “i’m looking for my japanese professor.” sentence 1, on the other hand, has no such implication, and the sense is that you are looking for just any professor who would be able to teach you japanese. so, there’s the difference: familiar nouns get “differentially marked” in object position in these kinds of languages.

what do these things have to do with each other in japanese?

now, you probably already know that japanese does not have the kind of differential object marking used in spanish, mostly because there are no articles, definite or indefinite, in japanese. so why am i bringing it up? as it turns out, even though there is no grammatical differential object marking in japanese, there are still strategies available to get a similar semantic idea across. let’s return to the first two example sentences and now translate them:

先生���二人探しています。 = i’m looking for two teachers.

二人の先生を探しています。 = i’m looking for these two teachers...

notice the difference? in japanese, when a quantifier is not floated (i.e., when it’s attached pre-nominally with の), it gives the implication that the speaker is already familiar with the noun being quantified. in other words, quantifier floating reduces quantifiers to their most basic function: as a marker of amount. in sentence 1, it doesn’t really matter who the two teachers are—the speaker is probably just looking to hire any two teachers, so long as they can teach the necessary subject. but in sentence 2, the implication is that the speaker is looking for two particular teachers, maybe who co-teach a class together or who always get coffee after school together. so, while this is not differential object marking in the strict, grammatical sense, japanese uses this quantifier-placement strategy to produce a similar semantic result.

and there you have it!! that wasn’t actually that scary, right? linguistics is not as crazy as everyone says it is, we just have a “terminology problem” that makes stuff sound 10x more complicated than it really is. (seriously, this is an actual issue in the field. people can’t understand each other bc they were trained on different sets of terminology lol. #academia)

anyways, i hope this was clear and helpful, and feel free to send me any asks about grammar or semantics or whatever!! 週末を楽しんでね!!✌️

#langblr#japanese langblr#日本語#linguistics#japanese grammar#sorry i have no actual sources for this but if anyone wants one i will go find some!!#just lmk#sasha.txt#grammar

279 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is This Good Latin? Agatha All Along Editon #6

In the last post from this edition I bring you two spells! And also a confirmation of another spell that wasn't quite apparent the first time. Let's get to it.

Drawing a protection circle

This one happened a couple episodes ago but without subtitles, it was difficult to catch. Thankfully, Agatha repeated a couple of the previous spells and this one was finally very undestandable. Here goes:

Expelle hoc malum. / Expell this evil.

Completely correct. Good job, moving on...

Letting someone into a protection circle

This is a short sentence with one word possibly missing (no subtitles, just like always), but I think I can manage:

Te accipimus in circulum.

This one fits the context perfectly, as it is granting access to someone's space marked by rocks and stuff. accipimus comes from a verb accipere, which has the exact same meaning one would expect. It is in 1st person plural form: we accept. This verb has an object in accusative case – te (you) – and also a prepositional phrase attached to it – in circulum (into the circle). circulus is a circle in a literal sense and also a gathering or a group. In the scene, I would say it is more literal but I like the double meaning all the same. The word is in accusative case to signify direction. So the translation is:

We accept you (let you) into the circle.

This one is a perfectly good Latin as well! Gif break.

Banishing a ghost

Interestingly enough, this spell was in the subtitles when I was watching, but I don't know if it was in the official ones or if my pirate subtitler decided to get creative, either way, it din't help, because it was complete gibberish. But because this spell kept being repeated over and over again, I think I got it!

Vale ad lucem. Relinque terram. Noli esse phantasma.

It's pretty basic stuff one would think of when creating a spell for getting rid of a ghost. The first part has ad lucem (towards the light – light is lux in its basic form and lucem is an accusative after ad), so you probably already know where this is going. The verb is actually kind of fun, though.

valere (infinitive form) can mean many things but originally it meant "to be strong, powerful" or even "to be healthy". Its imperative form vale was a Roman goodbye, literally "be well", but exactly because it was used to mean "goodbye", the verb gained a new meaning in what we call New Latin (Latin used from 15th century onwards): "to leave, to go away". So the first part is literally:

Go towards the light.

But the vibe is:

Get the fuck out, here's the door.

Now for the second part, once again, nothing unusual. relinquere means "to leave behind", relinque is the imperative and it needs an object in accusative, terram is accusative and it means earth (basic form is terra). Therefore:

Leave the earth.

The last part is silly, to be perfectly honest, but I like its structure. So nolle means "to not want" and its imperative noli ("do not want!") is often used when prohibiting something. esse means "to be" and phantasma is a (originally Greek) word for apparition or a spectre. So to conclude, this whole spell means:

Go towards the light. Leave the earth. Don't be a ghost.

Imagine saying the last part in English. Imagine. Silly. As I said.

Anyhow...

That is it, party people! The last few spells are good Latin! And the show as a whole gets like a B, maybe? Good job! Maybe see you with some other show that dares to use Latin, who knows.

Vale!

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

You are my hero for using the phrase 'perfidious Albion' in your tags. What is the French obsession with Alexandrine meter?

:) Well it's just that for a very long time France considered the 12-syllable verse known as the alexandrine to be the pinnacle of versification. For your poetry or play to be considered high literature it had to be in alexandrines (I was recently reading an English jstor article about translations of Shakespeare in the early 19th century and it went “[French translator] prefers to translate in verse, which means, of course, in alexandrines.” Of course!) We've moved on now and they’re out of style, but we’re still secretly fond of them I think. We were held hostage by alexandrines for so long a lot of French people still have a Stockholm-syndrome preference for their specific flow over other kinds of poetic metre.

They left a strong legacy in our language too—a lot of French sayings / proverbs are alexandrine verses because they’re excerpts from classical theatre and poetry (e.g. “A vaincre sans péril on triomphe sans gloire” from Corneille; “La raison du plus fort est toujours la meilleure” from La Fontaine; “Qui veut voyager loin ménage sa monture” from Racine; “Chassez le naturel, il revient au galop” from Destouches, “Vingt fois sur le métier remettez votre ouvrage” from Boileau...)

The alexandrine had a long golden age, from the Classicists to the Parnassians (mid-17th to late 19th century)—the Romantics in between were advocating for a kind of “free verse” but it still meant alexandrines and pretty rigid ones at that! (Victor Hugo’s “J’ai disloqué ce grand niais d’alexandrin” was subversive—but it’s still an alexandrine.) Their verse was only considered rebellious because it ignored some of the many rules that went into a perfect classical alexandrine (e.g. no overflow, 4 rests per line, rhyme purity must be respected when it comes to mute consonants, no liaison between the last word of an alexandrine and the first word of the next, the hemistiches of two successive alexandrines mustn’t rhyme, no prepositions or other tool words at the end of a hemistich, etc. etc.)

Then in the 19th century we liberated ourselves from the tyranny of the alexandrine after Verlaine shot them dead (insert Rimbaud joke) by doing things like placing the caesura on the 3rd syllable of a 5-syllable word (“WTF”—Racine) or ending an alexandrine in the middle of a word and treating the first half of the truncated word like a legit rhyme, which made all the Classicists roll over in their grave.

I really like alexandrines personally! I admit they can sound plodding after a while especially with classical rhymes, but they have such a soothing flow. I also love that they are often French at its Frenchest. By which I mean, there are some gorgeous alexandrines that are genuinely the French language at its best and most graceful, and then you have those that can’t help but highlight how absurd our syntax can get.

My favourite types of alexandrines are the ones with a diaeresis in each hemistich because saying them normally feels like walking down the street, while saying them as an alexandrine feels like doing a figure skating routine (e.g. in Racine, “La nation chérie a violé sa foi”); the ones with an AB-BA structure (“Et le fuyant sans cesse incessamment le suit”), the ones with a ternary structure (“Je suis le ténébreux, le veuf, l’inconsolé”, “Je renonce à la Grèce, à Sparte, à ton empire”) and the ones where 1 word sprawls over an entire hemistich (“Voluptueusement dans cette paix profonde...”).

The worst alexandrines imo are the ones that force you to acknowledge how many tiny grammatical bricks are involved in the building of a French sentence. Orally we tend to squish them together so we can forget about them but the merciless alexandrine will demand that you mortify yourself pronouncing all of them, e.g. “O nuit, qu’est-ce que c’est que ces guerriers livides ?” (thank you Victor Hugo for this ignominy) (<- here’s an alexandrine), or “Si ce que je te dis ne se dit pas ainsi”... “Ce que je te (...) ne se” is a horrible succession of words by poetical standards but wait I’ve got worse!

Tu m’as pris mon trésor et t’étonnes tout bas De ce que je ne te le redemande pas

“De ce que je ne te le”—see? French at its Frenchest.

#ask#language tag#(french speakers tell me your favourite alexandrine if you have one!)#ce dernier couplet provient d'un livre sur la poésie de hugo qui m'a surtout marquée parce qu'à un moment#l'auteur consacre plusieurs pages à citer des vers dont le contenu terre à terre contraste ridiculement avec#la grandiloquence inévitable de l'alexandrin#et c'est vrai que certains sonnaient plus comme une réplique de trissotin qu'un vers de la légende des siècles#mais quand même t'écris un bouquin sur victor hugo et tu décides de passer 20 pages à lui mettre la honte

485 notes

·

View notes

Note

I just finished The Heart of the World, literally a day after receiving it. It's so good! I love the way that you reinterpreted the characters in the fic so that you can still see them in the characters of the book. I'm also intrigued by Death-who's-not-Lily.

I have a couple questions. First, how and why did you decide on Iff, Theyne, Wheyne, and Annde as the humans' names? Second, Lily doesn't really get along well with Snape, if I remember, so why does she get along with Ilyn now?

And finally, when is the next book coming out???

Oh my god, look at you go! Thank you, I'm very flattered and glad you enjoyed it.

And now, your questions.

The Names

So, a fun fact, I hate naming characters and things. It's generally not something I have that much interest in and am not that attached to. Sometimes, you get a really great name and you're never letting go of it for that character, and sometimes you could honestly call them "Boy with Stick" and be done with it.

I now needed a lot of names and I wanted readers at a glance to be able to know, generally, which character belonged to which group. Which meant I needed themes.

There's a hilarious anecdote to be told where @therealvinelle on editing, wanted to go all out and come up with real, non-existent, but believable names for characters where you can tell a whole lot about their society by naming them.

I, um, said "Uh, these people will have backwards common English names. And these people will have QWERTY keyboard smash names. And these ones... Fuck it, he'll be Questburger."

So as for the human nobility, Lily got her name first, as Iff, the idea being a stupid joke/pun that isn't funny on my end where "iff" in mathematics is short for "if and only if". What it gets at is that Lily, as we see her, is the product of a very particular chain of events, that we're in a very particular world, and that there's something to follow that "if and only if" that is integral but that we're currently missing.

But then I have to come up with names for everyone else. And so we got the House of Prepositions and Conjunctions. Very serious they are.

Theyn was next up, as the next central royal character, and his name has a similar "har har but not really because it's not that funny and kind of weird" theme to it where the idea is he's "then BLAH", you're always waiting on something to occur with Theyn, unwittingly passing over him for the more interesting context in the sentence. He's there to set up something else, and by himself feels incomplete/not that interesting. Poor poor Theyn, even the universe doesn't think he's interesting or important.

Annde was next as he's the next important character we meet from this background after Theyn. Similar joke with him, he's "And... And?" You're waiting for the rest of the sentence with him, you can't end a sentence on "and" nor can you start it on one. He's just there to fill the gaps, to not be that important, and oh look a spoiler.

Wheyn (the regent) was next and was in part because a) I needed a name b) he's a bit of an inevitability in the universe. When one has a shake-up in a monarchy that holds all the power/isn't a constitutional monarchy, there's always going to be backstabbing nonsense and power plays. Wheyn is an unimportant inevitability, one that shocks no one (except Theyn, poor Theyn) and the answer to "When blah happens expect rain".

Which leaves us with, I believe the last, Whye, Lily's father. Him it's a similar gag but three-fold. There's the "WHY?!?!?!?!" in that no one really understands why he gave up the throne, married a sun elf, and scandalized absolutely everybody. Then there's "why?" as Lily's reaction, she's ambivalent about her parents and not sure how she should feel about them, and shields herself from feelings of abandonment by telling herself she's indifferent. As a result, she tends to approach any information about her parents with a "why should I care?" and gets very uncomfortable when anyone brings either of them up (and there's also that every character so far has brought up Lily's mother much more than her father leading to that question of "why are we talking about him?") Then there's the fact that there's a question to be asked that implies he has some kind of an answer to it a "why?" drifting off out there somewhere in the backgrounds.

And that's all the human nobility from our fantasy universe so far. (Elizabeth is noticeably an Elizabeth and sticks out like a sore thumb.)

Lily and Ilyn

The short answer is that Snape and Ilyn are different people fundamentally. They're in similar roles, took similar actions for various reasons, but they're very different as people.

And that goes for a lot of the things in the book. Elements of the fic remained, and some elements of HP, but not as much as people probably suspect even with the things that are very clearly taken over (believe it or not, I would call Elizabeth and Hermione different).

As for the long answer, well, for other people read the book and I hope it's explained.

When Next Book?!

I'm flattered but I don't know yet. Have to write it then edit then cover art and all that jazz.

I'll let people know.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the weirder hot takes you get from grammar prescriptivists is that reinforcing double negatives ("you didn't see nothing") are somehow inherently incorrect or a sign of stupidity.

Incoming: a short rant about linguistic prescriptivism and then an excerpt from the Canterbury Tales.

Firstly, there are more languages than English, and in many of them it is the norm that negatives reinforce, rather than cancel each other out. You might say "yeah but not in English," but you're objectively wrong. Several dialects and sociolects of English use reinforcing double negatives, it's just that you're dismissing the people who use them as either stupid, non-fluent, or both (the idea that a well functioning adult could lack fluency in their own native language is preposterous by the way). The racial dimension is too obvious to even be worth diving into.

However, I think the thing that annoys me the most is the resounding ignorance and arrogance of the people who think like this. Sure, the part where you assume that every language and every dialect follows the same grammatical rules as your own is a common enough mistake, but the irony is that by insisting on this, you're showing your own ignorance of the language with a gesture intended to signal your superior grasp of it.

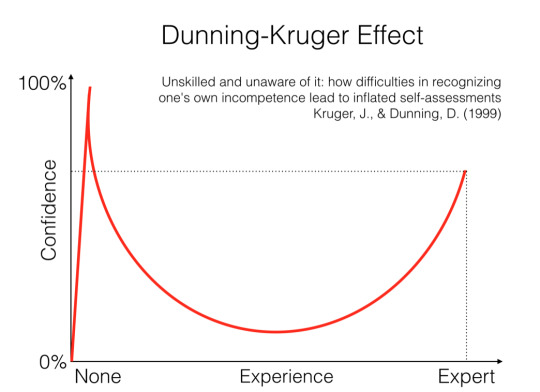

The average linguistic prescriptivist is in my experience not very well educated in language, not its formal rules, not the scientific study of it, and certainly not with its literature. They tend to occupy the "knows enough to think they know something, but not enough to realize how little they know" section of the Dunning-Kruger curve.

Note that this graph is a simple representation of an idea, not the result of a study or anything like that. The numbers and relative positions here are made up. That's how the curve manages to slope back in on itself after the peak.

What I mean is, they tend to know enough to be moderately aware of the formal rules of "standard" English, without any grasp of the real nature of a language (usually conceiving of it as some kind of ideal object that can be "correctly matched with" in an objective way), and even more damning, without a lot of experience actually engaging with that language beyond speech and simple text.

At best, they know some factoids from high school about how you're not supposed to end a sentence with a preposition (it's fine, actually, English is a Germanic language which means it loves shifting word order around) and such.

Anyway, here's a quadruple negative used in a reinforcing manner by Geoffrey Chaucer, arguably the founder of English-language literature, while describing the knight character in the prologue to the Canterbury Tales. A genuinely good writer that, along with Shakespeare and many others, one must presume that these prescriptivists have never read, at least not closely, though they in my experience tend to pretend they have.

At mortal batailes hadde he been fiftene,

And foughten for our faith at Tramissene

In listes thries and ay slain his fo.

This ilke worthy Knight hadde been also

Sometime with the lord of Palatye

Again another hethen in Turkye;

And everemore he hadde a soverein pris.

And though that he were worthy, he was wis,

And of his port as meeke as is a maide.

He nevere yit no vilainye ne saide

In al his lif unto no manere wight:

He was a verray, parfit, gentil knight.

Or, if your Middle English is rusty, here's my rough translation:

He had been at fifteen tournaments to the death

And he had fought for our faith at Tramissene (Tlemcen, Algeria)

In three lists (tournament grounds) and always slain his foe.

This same worthy knight had also been

Some time with the lord of Palatye (the Emir of Balat, Turkey)

Against another heathen in Turkey;

And evermore he had a superior reputation.

And he was every bit as wise as he was bold.

And his demeanor: as meek as a maid.

He never yet no rude thing hadn't said

In all his life to no kind of person:

He was a true, perfect, noble knight.

Anyway, in conclusion, prescriptivists shut the fuck up.

#takes#mini essay#history#linguistics#politics#poetry#geoffrey chaucer#dunning kruger#canterbury tales

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Patterns (Tag game!)

Rules: list the first line of your last 10 (posted) fics and see if there's a pattern!

oh this is fun!!! if i can even remember what my last ten fics were, chronologically, jesus. tagged by @northstarfan, with whom i wrote (*counts*) fully half of these. XD THANKS, BB!!!<3

Hugh’s legs trembled, and sweat beaded on his face, cold and distracting, but he said nothing, only planted his feet a little wider and tried again to lift the weight in front of him. (source)

Hugh makes his way to his and Elnor’s shared quarters after work, bag of pastries in hand, and chimes the door. (source, nsfw)

Lao couldn't get his arms around Liu Kang, couldn't raise them or make them respond. (source; slightly cheating - this is the first sentence after a section break, but it was the first paragraph i wrote.)

Until he heard from a friend about the police chief posting in a sleepy seaside town, Martin Brody had never heard of Amity Island. (source)

Kung Lao had never thought less of Liu Kang because he wasn’t destined to be a champion. (source)

Sunlight was just beginning to slant in the transom above the big picture window of Hugh’s quarters. (source, nsfw; slightly cheating - this is paragraph 4 of the fic, but it was the first paragraph i wrote.)

Elnor peered out through the blazing Coppelius heat, the horizon shimmering to a watery blur, and pushed his sweat-stuck hair off his forehead with the back of his arm. (source, nsfw)

Joe’s shocked almost speechless when he comes to the morgue late one Friday to pick up Fernando for dinner; Fernán had to work a little later than he did, finishing up paperwork in advance of what, apparently, is well-known among medical examiners as the ��Christmas rush.” (source)

The memories are so faint and confused now, and Elnor struggles to recall his father’s face. (source)

An array of green lights burned far overhead like a hundred malicious eyes; pain burned across his skin, and he couldn’t move his arms or legs or even his head, which Elnor realized, as he fought back to consciousness, was because he was restrained, not paralyzed. (source)

honestly, i try to start fics by copying the styles of better writers i've read, and by trying to avoid anything too cliched or over the top. apparently i have a strong preference for starting with pretty straightforward subject/verb constructions rather than prepositional phrases or lines of dialogue. (i feel like i used to open on dialogue a lot more often when i was younger? i think i may have intentionally started steering away from it because it strikes me now as the kind of thing that could get annoying to read over and over.)

tagging @suilesbian, @cactusdragon517, @wolfhalls, @hellolittleogre, and @avi17, as well as anybody else who wants to pick it up and run!

#i write sometimes#genuinely pleasantly surprised that none of these are too ridiculously long or convoluted or tropey#honestly the average length of my starting sentences is like. half of the average length of my sentences overall.#USE MORE PERIODS IDIOT

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Brief Guide to Mewling

Mewling, or as its referred to by the mews as either 'Myukox' if you're a grandpa or 'Ḿaw' if you're a slightly younger grandpa, is my first ever language i've ever made by process of linguistic evolution. So it's weird and at times blaringly novice but it gets the job done. Getting into some linguistic jargon, it's a polysynthetic agglutinative language with free word order. The writing system is a logography (like chinese) that's written top to bottom, left to right. I'm gonna divide everything up for the sake of convenience

Sounds

These are the sounds in it:

you can use this website to specifically hear what each sound sounds like but for the most part everything is BASICALLY pronounced how it's written. For reference of some not immediately intuitive ones (in reference to the perspective of english speakers), ill gloss over those.

/ɸ/ and /β/ are like f and v but instead of using your upper lip and bottom set of teeth, you use both your lips. It's blowing but with a purpose.

/t͡s/ is exactly what it looks like. just a ts sound

/t͡ʃ/ is just ch

/x/ is like the ch in loch or the gh in ugh. that kinda throaty sound you know the one.

/j/ is actually y

/ŋ/ is like the ng in sing (its pretty rare tho in mewling so dw abt it too much)

/ʃ/ is just sh

The syllable structure is (F)CVC where F equals a fricative (s, z, f, v, sh, j, and x), C means any consonant, and V means vowel. The stress pattern is weird but the rule is stress always falls on either the last syllable (in words with only two syllables) or the third syllable from the end (in words with more than two syllables) UNLESS the second syllable from the right ends in a consonant in which that case it will be the one stressed instead.

Syntax

Mewling has free word order meaning that you can shove a word anywhere in the sentence and it would be understood the same. 'the man ate the orange', 'the orange at the man', or 'the man the orange ate' would all be understood to mean the same thing because mewling changes the words based on if its the subject of the sentence or the object. But by default mewling is subject-object-verb, meaning the verb almost always is at the end of the sentence (like in japanese or latin). Adjectives go before nouns, prepositions go after nouns, auxiliary verbs go after the main verb.

Grammar

Mewling is actually kinda fun imo with this. Mewling is agglutinative so when it makes new words it does so by taking smaller words and putting them together. 'ki' (this) + 'mar' (land) = kimar (place). 'ere' (give) + 'tos' (knowledge) = eretos (teach) and so on and so forth. Pretty straightforward. English does this too esp with words w germanic origins: birthday, butterfly, notebook, rainbow, honeycomb, bathroom, etc etc.

Now for nouns, their pronunciation changes depending on their noun case, which is a type of suffix (in this case) that acts kind of like what a preposition does in english. for example:

netal (the tree)

netalotso (at the tree)

netaler (in the tree)

netala (away from the tree)

netalova (towards the tree)

etc etc so on and so forth. Now some noun case do grammar stuff. The subject has no special suffix but it's usually at the beginning of the sentence so it's whatever. The object, the word that's receiving the action of the verb, uses the suffix '-n' or '-on' depending on the word. so in this sentence

Myu miron moraf (the mew eats the fruit)

It goes 'the mew' (subject) 'the fruit' object 'eats' (verb). The fruit is what's being eaten by the mew, it's being affected by the action. Now you could even put the object in front

Miron myu moraf

And it would mean the same thing, because the fruit is still marked as the subject. But if you made the fruit the subject

Mir myon moraf (The fruit eats the mew)

THEN that'd actually change the meaning. english doesn't really do this, we just know which is which because the subject is always before the verb and the object is always after. but doing this allows mewling to be able to change its word order to express different kinds of sentences.

Now verbs were the hardest part to create but GOD is this part fun. the verbs conjugate for tense (time), mood (specific action or meaning), and agree with both the subject AND the object (usually languages will choose one or the other). It has a past, present, and future, and you can add a whole bunch of suffixes to make the verbs specific. for example:

tos (know)

toslan (knew)

tosfas (will know)

and you can make REALLY long words like this

wemokorwanfunolanisolirikorcharaywamapikorusatif (which means something along the lines of "if (this) wouldn't have wanted to accidently been made to need to have started to continue to be able to constantly be improving (by me)" or something like that) tho its rare and more comical than anything to get THIS long. i could talk all day about the verbs but i'll add one more thing.

Mewling has three pronouns: mi (i) pa (you) and yo (they). these are usually changed up with whatever noun case it needs but since the verb changes to show both the subject AND the object the language becomes pro-drop, ie the pronouns can be dropped from the sentence entirely because the verbs make them redundant. for example:

Mi pan maso (I see you) is grammatically correct but more often than not it would be shortened to just 'Moso' because the verb already says that I'm the one seeing you. the pronouns are unnecessary. this in turn allows someone to say an entire sentence in just one word. very useful.

IN CONCLUSION i was really really really REALLY just summarizing cuz i didnt even get into things like relative clauses or sentence reordering for conjunctions or specific cultural notes of the language BUT i hope this'll give at least a smidgen of an idea of how much work i put into this. if you ever want me to translate something don't be afraid to ask too, at this point i could pretty much translate almost anything lol. But for now, sonapatan pafu nenampinon iyer (thanks for reading).

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Сон Амариэ: a breakdown. Part 1

Sooo. Ever since that summer concert performance of Finrod in Moscow i've been obsessed with Сон Амариэ. I've thought a lot about strengths and hiccups of this song, and i really wanna talk about them. Full lyrics han be found here. Unfortunately, stupid Tumblr character limitation won't let me make it a single post so i will have to break it into several. Let's start with a common issue that can be conveniently summed up.

False semantic pairs (and other grammatical oddities)

There is a common problem in this song that if very typical for Finrod's lyrics in general. I am talking about concepts and ideas that are put into an associative pair but actually cannot form one due to a logical error. The first one we encounter early on, in the phrase Лес молчит, словно полк, лишённый короля. Now, granted, a king like Finrod is expected to also be a military commander, and it is natural for regiments to be led by him into battle and to lose their resolve and fall into silence when their king is suddenly gone. (Though i must say, here i read a weird subtext of 'disloyalty to the cause', as if someone is trying to rally this troop, but in response gets only silence. A really weird undertone to describe a still forest which it the only thing that is there to answer you - and it doesn't - when you call out a lover's name. But that might be just me. It's far more likely that Amarië invokes the imagery of Finrod's deeds in Endorë as she imagines them and feels a foreboding dread that he is not there anymore. Of course a forest can look as abandoned as a troop without a commander. It is, after all, a dream.) But still - it is plain that a pairing "regiment - king" is occasional and conditional. The most natural associative pairing for полк would be полководец, командир, офицер.

Чтобы верить, не нужны ни разум, ни глаза. Now, it is a beautiful sentiment that describes faith and trust against all reason and evidence. But there is still a problem, a case of misplaced metonymy! Разум (reason) is a non-material entity that is usually associated with a body part - a head. Глаза (eyes) is very much a material thing, it is a body part which corresponds with an immaterial sense - sight (зрение). The point being made in the lyrics is, in order to have faith, one needs neither to reason nor to see with their own eyes - or, in other words, one believes with neither their head nor their eyes. But the lyrics try to have it both ways, and it doesn't work. The author chooses to use разум instead of голова (or (иметь) глаза instead of видеть), and as a result we get a mismatch.

Ветви, словно руки, сплетают сеть. The logic in this metaphor is again faulty. True, we often compare tree branches to arms or hands, it's very common. (In Russian both arm and hand are called by the same word, рука.) But then this net thing creates a confusion. Branches indeed can interweave, and arms/hands (or rather fingers) can be interlocked. In Russian both these meanings can be expressed with cognate verbs плести, сплетать, переплетать, the root -плет- meaning 'weave'. The problem is that branches do not actually weave any nets of any material - they themselves intertwine in such a way that a net is formed. On the contrary, hands do weave nets, they are not a material, but an instrument for that. Again, there are two conflicting ideas in this sentence, and they cannot be combined into a functional metaphor. Now, i'm gonna add another entry, a bit of a different kind, that does not necessarily describe errors but still is worth mentioning.

В тьме и в свете я тебя по имени зову. A couple of things here. For euphony sake it is customary to use во not в when the preposition is followed by several consonants (во тьме). Here it is not so for the sake of rhythm. (Also it is worth mentioning just for completion sake that there are two words in Russian that both mean 'darkness': темнота and тьма. The latter, the one used in the song, carries more of an elevated, metaphorical meaning along with the literal one.) В свете is a curious thing, and it is a bit of a nitpick. I don't begrudge the author this form, in my opinion it is acceptable in a poetical work, but i feel it is still worth mentioning. The form в свете that appears in the song is actually a locative that is used not for material but immaterial entities. For carrying across a meaning 'in the light', 'being lit by light' one would say на свету or при свете. В свете is a form that belongs to a word that usually has a separate dictionary entry. It is свет as in 'world', '(high) society'. Here is an example from Eugen Onegin: when Tatiana's husband sees that Onegin does not recognise his wife, he tells Onegin, Давно ж ты не был в свете! Charles H. Johnston has it translated as "...you banish yourself too long from social life". Again, in our case this form comes to use for convenience sake and is used for poetical uniformity. Part 2 Part 3 Part 4

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

How does sentence syntax vary between languages? I'm gonna guess that the more closely related languages are, the more similar their sentence structure.

The short answer: Lots.

The longer answer:

Basically every language has its own syntactic structures, but we can broadly (and this is waaayyyy oversimplifying things) break them down into three broad types: (function) configurational, discourse configurational, and non-configurational languages.

(Function) Configurational languages are those languages where the structural position of constituents determines their grammatical functions (such as subject, object, etc.). English is a classic example - excepting a handful of operations like topicalisation, the subject of a predicate will always appear in spec-IP (appearing before any auxiliaries, which appear before the verb); the object will always be the daughter of V' and sister of V; etc.

Discourse configurational languages are those languages where the structural position of constituents determines their discourse functions (such as topic, focus, etc.); grammatical functions are usually determined by morphology (e.g. case inflections, verbal agreement) or inferred from context. Hungarian is a classic example - your basic Hungarian sentence has a structure something like

[Topic] [Quantifiers] [PPP] [Verb] [Postverbal Comment]

Where PPP is the "prominent preverbal position", typically used for the most prominent topic. Importantly, there is no "subject position" or "object position" like in English - you can make some rough predictions (subjects tend to be topics so you're likely to get a few subject-initial sentences), but it's the case marking that does the real "heavy lifting" here.

Then you have non-configurational languages in which there seems to be no fixed word order for sentences - basically the order of constituents has more to do with prosody and vague pragmatic categories like "prominence" than having fixed positions which are always subject/object or always topic/focus etc. A classic example of this kind of language would be the Pama–Nyungan language Warlpiri. In Warlpiri, you have a fixed second position where the inflected auxiliary goes, you have a first position before that where something prominent goes, and then you have everything else in whatever order you fancy after that inflected second position, so you end up with trees that look something like the following, where each X is some kind of constituent (X, X' or XP, not necessarily all the same type).

[ID: Schematic syntax tree in which a single IP dominates a pre-I position marked with X going to ..., and the I' dominates a post-I flat S structure that dominates a series of Xs, each going to ...]

In addition to this tripartite classification, you can further classify languages by the order of constituents and how they relate to each other. For example, you can distinguish between head-initial languages (where you get the head of a phrase followed by any modifiers) and head-final languages (where the modifiers come first, followed by the phrase). And, of course, you can get a mixture as in English - we have (mostly) head-final noun phrases (articles and adjectives come before the head noun) and adjective phrases (adverbs come before adjectives), but we have head-initial adpositions (prepositions rather than postpositions). And that's without getting into stuff around basic word order (e.g. SVO vs SOV vs VSO etc.).

Then, of course, within and across these broad typological categories you have a bunch of languages that do their own thing to varying degrees. German (and several other Germanic languages are similar) is an interesting case study here, as its kind of a mixture of functional configurational and discourse configurational, and also it kinda does its own thing on the side as well.

Basically - and, again, this is very simplified - German sentences have a structure that's:

[Vorfeld] [V1] [Mittelfeld] [V2] [Nachfeld]

Where V1 contains the inflected verbal element (often, but not always, an auxiliary) but everything else verbal, if anything, is pushed to the back of the "sandwhich" to V2. This "sandwhich" structure is referred to as the "Germanic V2" sentence structure.

The Vorfeld position is often the subject, but really it's a topic position (like in discourse configurational languages like Hungarian). So, for example, the difference between

(1) Ich bin heute zu Hause gegangen. (I went home today)

and

(2) Heute bin ich zu Hause gegangen. (Today, I went home)

concerns whether the topic of discussion is the person doing the going (i.e. me) or the time when the going happened (i.e. today). So (1) would be an appropriate answer to "who went home today?", but (2) would be a better answer to "when did you go home?".

The Mittelfeld area is... complicated. If the subject isn't in the Vorfeld, it'll be the first thing here. The direct object will usually be the last thing (immediately before V2), unless its a pronoun, in which case it will typically be the next thing after the subject. Indirect objects are the next thing after any subject and/or pronominal object. Then you get adverbs, especially temporal adverbs. Then everything else. Mostly. Except you can also move all this around for prosodic reasons or for prominence or other pragmatic reasons, and honestly I probably forgot something or got some bit of the order wrong here.

Anyway, main point: German isn't straightforwardly either discourse configurational nor functional configurational (it has bits of both - fixed object positions, but also a fixed topic position), and it also has it's own distinctive structures (the Germanic V2 structure).

And lots and lots of other languages are like this - as or more complicated than the German example.

(I know there are some other linguists who follow this blog so please feel free to sound off in the notes about your favourite languages that have funky or unique sentential syntax!)

Returning to your second question, while it is true that closely related languages tend to have very similar sentential syntax, this isn't a guarantee - e.g. English is very much a Germanic language but the Germanic V2 is only preserved in a handful of English constructions, and Latin had a much flatter sentential syntax than any of the modern Romance languages. So language change, and also flattening effects such as being used as a colonial language (see English, Persian, etc.) can shake that up so it's not a precise metric.

#asks#syntax#linguistics#not a tree#meta#theory#there's so much more I could go on about here#but I will restrain myself because this is already a#long post

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is Tou. His name comes from Greek, which stands for: "Of". Why does his name mean just a preposition? Because his entire name is a complete sentence in Greek; his entire name is: "Opadox Tou (Οπαδοχ του)", which means "Follower Of". Why is he named that way? Simple, because he is a partner of one of my "evil" characters throughout the story. Is he evil too or solely the follower of an evil figure? In the broad sense of the word, he is not intrinsically "evil", what he wants is just survive, but the person who he partners with to fulfill this purpose is (objectively) evil, thus you could say rightly that he is solely follower of an evil person. He decides to leave his values aside to prioritize his survival. He is one of the main secondary characters.

He likes puzzling over explanations for everything (in a logical way), making music and listening to techno music. He also likes being quiet through crowd because he gets overwhelmed when many people make loud noises (this is one of the main reasons why he carries his headphones on almost all along). He is introvert, kind of asocial, and a self-prioritize person when his goals or life are treading through thin ice. But after all, he does feel pity for people he leaves behind when self-prioritizing himself, but he tries not to think through or ponder it too much.

0 notes

Text

What is the Attribute of a Sentence?

The Attribute in English Grammar

In English grammar, an Attribute is a word, phrase, or clause that provides additional information about a noun or pronoun in a sentence. Attributes are modifiers that help describe or characterize the noun or pronoun by answering questions such as what, what kind of, whose, which, how much, and how many. Attributes are essential for adding detail and specificity to language, allowing speakers and writers to convey more precise meanings. Here are some key points about attributes:

Types of Attributes:

Adjective Attributes(attributive adjective) These are single adjectives or adjective phrases that modify a noun. Example: a beautiful flower Noun Attributes: These are nouns or noun phrases that modify another noun. Example: a bookstore owner Prepositional Phrase Attributes: These are prepositional phrases that modify a noun. Example: a house with a red roof Numeral Attributes: Numerals that quantify or specify the number of nouns. Example: three cats, the second chapter, many friends Possessive Attributes: Attributes that indicate possession or ownership. Example: his car, my house, their ideas Demonstrative Attributes: Attributes that point to or identify a particular noun. Example: this book, those flowers, such situations Quantifier Attributes: Words that express quantity or extent. Example: some friends, all students, no time Interrogative Attributes: Words used to form questions, often modifying nouns. Example: which book, what idea, whose laptop Relative Clauses (Adjective Clauses): Clauses that modify nouns and usually begin with a relative pronoun (e.g., who, which, that). Example: The man who is wearing a hat is my neighbor.

Placement of Attributes:

Attributes can appear before or after the noun they modify. The green grass (before) The grass with a fresh scent (after)

Function of Attributes:

Attributes help provide more information, clarify meaning, and paint a more detailed picture of the subject in a sentence.

Use with Pronouns:

While attributive adjectives (attributes) directly modifying pronouns are not as common as with nouns, they can still be used to add detail or context. Additionally, attributive phrases or clauses are often employed with pronouns for more elaborate descriptions.

Attributive Adjective with Pronouns:

Example: She found an interesting book, and she read it eagerly. In this case, interesting is an attributive adjective modifying the pronoun it, providing more information about the type of book.

Attributive Phrase with Pronouns:

Example: I met someone with a fascinating story to tell. Here, the prepositional phrase with a fascinating story to tell acts as an attributive phrase, providing more information about the pronoun someone.

Attributive Clause with Pronouns:

Example: Someone who wore a red dress caught everyone's attention. The relative clause who wore a red dress functions as an attributive clause, modifying the pronoun someone and offering specific details about her.

Diverse Expressions of Attributes

in Language:

Attribute can be expressed by an adjective, the participle, the participle clause, a numeral, a pronoun, a noun in the common case without preposition, a noun in the possessive case, a noun with preposition, the infinitive, the gerund with a preposition Adjective: Adjectives directly modify nouns and answer questions like what kind of? They can be single words or phrases. Example: a happy person Participle: Participles are verb forms used as adjectives. They can be present or past participles. Example: a person eating lunch, a broken cup Participle Clause: Participle clauses provide additional information about a noun. They often start with a present or past participle. Example: a person, who is smiling, in the photograph Numeral: Numerals are used to express attributes related to quantity or order. Example: a book with three chapters Pronoun: Pronouns can act as attributes, providing information about the noun. Example: some friends, my pen Noun in Common Case without Preposition: A noun in the common case (or subjective case) directly modifies another noun. Example: a cat owner Noun in Possessive Case: A noun in the possessive case can function as an attribute. It adds information by specifying the possession or relationship. Example: The student's project was outstanding. Noun with Preposition: A prepositional phrase with a noun provides additional information about the main noun. Example: a student with a talent for music Infinitive: An infinitive can act as an attribute, expressing purpose or intent. Example: a plan to visit the museum Gerund with Preposition: A gerund, a verb form ending in -ing, can be used with a preposition to act as an attribute. Example: a person of doing his best in art

Attribute-a Noun in Opposition

A noun in apposition is a specific type of attribute where a noun or a noun phrase is placed next to another noun to provide additional information about it. This construction is often used for clarification or emphasis. In the example: London, the capital of England, is a very old city-The capital of England is a noun in apposition, adding detail to the noun London. It's a way to identify and describe London more specifically within the sentence.

Placement of Attributes:

In English grammar, the placement of attributes is flexible, but there are general rules that guide their position in relation to the noun they modify. 1.When the defining noun word is expressed by an adjective the attribute usually comes before the noun: Examples: the blue sky a large dog an interesting book 2.When the defining noun word is expressed by a participle, the attribute usually comes before the noun. This structure is often seen in complex noun phrases. Here are examples: Participle as Defining Word: the broken window a shining star the fallen leaves Defining Word with Participle in a Phrase: If the defining noun word is the participle in a phrase then the attribute comes after the noun: a table with a cracked surface the girl with a sparkling personality a story with a twisted ending 3.When the defining noun word is a numeral, the attribute typically comes before the noun. Here are some examples: Cardinal Numbers: two cars five books ten students Ordinal Numbers: the first chapter the third row her second attempt 4.When the defining noun word is a pronoun, the attribute typically comes before the noun. Here are examples: Possessive Pronouns: his big house our favorite restaurant my old car Demonstrative Pronouns: this beautiful flower that interesting book these colorful paintings 5.When the defining noun word is a combination of two adjectives, the attribute typically comes before the noun. Here are examples: Two Adjectives Modifying a Noun: a beautiful, sunny day an old, wooden chair a fast, red car

How to place adjectives (attributive)

in relation to Nouns:

When a noun is modified by two adjectives, the typical order is to place the adjectives in a specific sequence. This sequence is often referred to as the OSASCOMP rule, which stands for: Opinion: Adjectives expressing opinions or judgments (e.g., beautiful, interesting). Size: Adjectives indicating size (e.g., small, large). Age: Adjectives denoting age (e.g., old, new). Shape: Adjectives describing shape (e.g., round, square). Color: Adjectives representing color (e.g., red, blue). Origin: Adjectives indicating origin or nationality (e.g., American, French). Material: Adjectives specifying material (e.g., wooden, metal). Purpose: Adjectives expressing purpose or qualifier (e.g., cooking, running). For example: a beautiful small house- beautiful falls under the category of opinion, small indicates size. Therefore, beautiful comes before small in this sequence. 6.When the defining noun word is a noun in the common case without a preposition, the attribute the typically comes before the noun. Here are examples: Common Noun without Preposition: a blue sky a happy family an interesting story 7.When the defining noun word is a noun in the possessive case, the attribute still typically comes before the noun. Here are examples: Possessive Case Noun: the professor's expertise the company's innovation my friend's advice 8.When the defining noun word is a participle clause, the attribute (or adjectival phrase) typically comes after the noun. Here are examples: Participle Clause as Defining Word: The girl, holding a bouquet of flowers, smiled. The book, written by a famous author, became a bestseller. The car, parked near the entrance, had a flat tire. 9.When the defining noun word is a noun with a preposition, the attribute usually comes after the noun. Here are examples: Noun with Preposition: a book on the shelf a cat under the table a painting of a landscape 10.When the defining noun word is an infinitive, the attribute usually comes after the noun. Here are examples: Infinitive as Defining Word: a desire to travel the world an opportunity to learn a new skill a decision to pursue higher education 11.When the defining noun word is a gerund with a preposition, the attribute typically comes after the noun. Here are examples: Gerund with Preposition: The team discussed the project before starting the presentation. She had no intention of coming back. He is passionate about a career in designing sustainable buildings. What is the Attribute? What is The Object of a Sentence? Subject-Verb Agreement in English What is a predicate? Predicate Types Read the full article

#anouninopposition#adjectivesplacementrelatingtonoun#afternoun#attribute#attributiveadjective#beforenoun#diverseexpressions#function#grammar#howmany?#howmuch?#modifier#noun#nounattribute#ofattributes#osascomp#placementattribute#pronoun#syntax#types#usewithpronouns#what#whatkindof?

1 note

·

View note

Note

what concepts would you recommend someone focus on if they’re in the process of learning Spanish and are going abroad in about a year?

It really depends on your level. I'm going to assume you're a beginner but you're really going to want to focus on conversational Spanish not just specific words.

Things like "how much" or "how many" or "where is it?" or "whose is it?"

So some things that might be helpful:

directions

colors

greetings/farewells

formality

agreement in nouns/gender and singular/plural

negatives and the use of no and nadie

the infinitives, -ar verbs, -er verbs, -ir verbs

personality traits, physical descriptions, moods and emotions

some basic idea of sentence structure

pronouns and when to include them or omit them

basic nouns for people, places, and assorted things [this really depends like is it a good thing to know different kinds of birds? yes but like it's better you know the words for hospital and hotel and school... unless you're becoming an ornithologist in which case idk bird stuff would make sense]

telling time and the calendar/seasons

polite requests

question words; who, what, where, when, why, how, how much, how many

weather expressions

present tense

some basic commands or just an understanding of commands and negative commands

really basic verbs

the -go verbs in particular [tener, decir, venir, hacer, poner, salir etc etc]

ser and estar; you don't need to know how to conjugate everything but you should know what the basic concepts are

definite and indefinite articles

saber and conocer especially present tense

clothes, at least some

possibly pero and sino

possibly preterite and imperfect; depends on your level, I would say the three most important tenses are present, preterite, and imperfect... just in general, but especially if you're in A-B levels

transportation vocab

asking for help vocab

some basic idea of what stem-changing verbs are, not that you need to know all of them, but just an idea

though I would say probably be aware of morir and dormir

poder also is very important

a basic understanding of gustar and words like gustar which will help you later with indirect objects

asking for someone's name, last name, numbers etc. and being able to introduce yourself and give information

numbers 1-100 [tbh it's basically 1-30, then understanding how numbers after 30 work and knowing 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, and 100]

ordinal numbers, but primarily 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, and 10th. Everything past that is a little confusing for basic students

cardinal directions; norte, sur, este, oeste but that's just 4 words

ir, dar, ver

not all of por and para but just knowing that they exist and are weird and sometimes different

prepositions a, de, en, con, sin and a handful of others; also being aware of conmigo and contigo

demonstratives

possessives

comparison

mejor and peor

the use of bueno/a vs bien

ir + a + infinitive for short-term future

the use of jugar + a

the use of haber at least in terms of hay for "there is/are"

ordering food and basic food nouns

a handful of idiomatic expressions, but don't worry too much about it if you don't know many

being aware of y, ni, and o... there's some weirdness with y and o as far as spelling rules but don't worry too much if you're a beginner they will explain it to you if you're taking language courses

Like I'm not going to sit here and say you don't need to know subjunctive, but it's usually not your immediate concern unless you're doing polite requests

Plus subjunctive is more advanced so I'm mentioning the basic basic basics

This is also probably all the verbs you need to know if you're a beginner ...a lot to take in all at once, but they're probably some of the most common verbs in all of Spanish

I'd recommend also looking into some grammar lessons like at www.studyspanish.com/grammar which runs you through some of the basics

And if there's any concepts you're confused about or have questions about let me know!

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

I can sum it up pretty well just from drop quoting from your own reblog tbh!

I was never taught grammar properly but something with the way my autism works makes me naturally good at picking up correct sentence structure and duplicating it

You're not alone. There's a whole lot of kids who can learn language innately through mimicry. My autism also makes me good at it, but it also makes me love grammar because I view it like a puzzle. And to an extent this is an evidence based practice; most children (emphasis on most, as in greater than 50%) will be able to pick language up (especially if just 'to an extent good enough to get by') this way, through reading, writing, and mimicry, through hearing and speaking. Because this is a way by which, let's say (pulling this number out my arse) 85% of American children can learn English to an acceptable level, and it's much easier to teach, and it's more enjoyable to the children, you can kind of see the logic of why people would want to teach that way. In fact, if you tell most people they need to learn grammar to be good at English, you'll get a lot of very virulent pushback in the style of "I was never taught that shit and I can speak just fine!!! You don't need to know what a prepositional phrase is to use one!"

However, as you yourself pointed out, it's an incomplete understanding. It leaves people unable to do certain things, such as craft complex but grammatically correct sentences, parse sentences with unusual structure, understand complex metaphor, and, yes, sound out complex medication names. On a more personal level, I also find it robs them of the opportunity to find certain forms of joy in the art of English--writers of poetry and prose alike benefit so much when they understand the lego pieces of what they're working with, just as visual artists benefit from understanding color theory or the properties of light.

For a fuller understanding of the concept behind Whole Language Instruction, I think the article from the person who supports it is a helpful read as well as it explains more of the logic behind WLI, as well as where the people who think a mix would be best (a mix WOULD be best, WLI is great at a secondary school [middle/high] level after a strong phonics based elementary education, IMO, but that's not what we're doing rn) are coming from. It also explains, again IMO, why it doesn't work as well in American classrooms, as we simply do not have the infrastructure or education system to support the concept in public schools.

Quick question, genuine question:

Why on earth does "more than half of US adults under 30 cannot read above an elementary school level" not strike horror into the heart of everyone who hears it?

Are the implications of it unclear????

I'm serious, people keep reacting with a sort of vague dismissal when I point this out, and I want to know why!

If adults in the US cannot read, then the only information they have access to is TV and video, the spaces with the most egregious and horrific misinformation!

If they cannot read, they cannot escape that misinformation.

This obscene lack of literacy should strike fear into every heart! US TV is notoriously horrific propaganda!

Is that???? Not??? Obvious???????

I know this sounds sarcastic, I know it does, but I'm completely serious here. I do not understand where the disconnect is.

21K notes

·

View notes

Text

lonely hearts club (m)

➾ 11k

➾ summary: jeon jeongguk has annoying little brother energy™. you know this deep in your bones. wedding after wedding, you keep running into him at the goddamn singles’ table, and he just won’t leave you alone. until you start to wonder... is he your ticket out of the lonely hearts club?

tdlr: enemies to lovers

➾ warnings: hate sex, public sex (in a photobooth lmao), impregnation role play, oral (f receiving), jk has intensely annoying energy, it gets unbearably cheesy towards the end

➾ a/n: wow, addie is back???? finally??? gosh, even I can’t believe it. please enjoy, and thank you for waiting :)

The first few times, it was lovely. Watching your friends find their partners and get married in holy matrimony, their faces filled with bliss as they walk down the aisle together towards their happily ever after. You tell yourself that you are truly happy for them, and you are. But you can’t deny that deep seated feeling of envy buried within you, and the sense of dread every time you receive a new wedding invitation.

Why’d all of your friends have to be so good at getting their shit together?

Which then begs the question, what are you actually doing here?

Other than celebrating your friend’s wedding, obviously. You crane your neck to look around the large, luxurious ballroom for any sign of Kim Seokjin and his husband, and you think you spot them at one of the tables up front.

You scan the attendees at your table surreptitiously. It goes without saying that anyone can see that this is the singles’ table, it’s obvious enough by the way no one talks to each other and how the host has made the painstaking arrangement to alternate the genders. You have no idea where this tradition of a singles’ table came from, and why you’re relegated to it at every single wedding you attend.

You sniff in indignation as you take a sip at the flat soda in your glass. For all they know, you could have a secret celebrity boyfriend hidden away somewhere. The both of you have decided to keep your relationship under wraps so as not to risk the wrath of the public, so that’s why you can’t bring him to events like this. There. Let that be your saving grace.

It’s embarrassing to be at the singles’ table at a wedding, even more embarrassing when you realise that the faces at the table come and go, all except for yours. In fact, you spot a few familiar faces integrated into other tables, drinking and laughing happily with their significant others by their sides, while you remain a permanent resident of the singles’ table.

This is your fifth wedding in as many months; and at this rate it seems like you’ll never graduate from the singles’ table.

A sudden movement interrupts your moment of drowning in self-pity, and you glance to the side only to realise that the empty seat beside you has been filled. All night long the empty seat had been mocking you, reminding you of what could have been a lovely night in with a few bottles of soju and some chicken, but now it presents you with a new contender to the singles’ table.

And God damn, you can feel the women at the table perk up at his presence, some of them shooting you envious looks because you happen to be seated next to him. The girl on his other side seems to be swooning already, but you staunchly refuse to react. Refuse to even look at his side profile.

Two singles matching up at the singles’ table is practically every host’s wet dream. So much so that you refuse to let it happen. No matter how good looking he is, you won’t let yourself stoop so low.

Are you bitter? Yes.

But are you willing to admit it? Most definitely not.

“No way- Jeon Jeongguk?” The gentleman on your other side stands with his arms spread in what can only be the bro code. “What are you doing here? God damn- I never thought the day would come when I meet Jeon Jeongguk at the singles’ table!”

Wait, why does that name sound so familiar? You can hear the smirk in the newcomer’s voice as he stands as well, and the two men embrace each other in a manner that involves a lot of back slapping and chest bumping.

It’s only then that you unwillingly catch a glance of his face, and immediately an unwanted thought occupies the front of your mind persistently. He is most definitely, without a doubt, the most eligible single man at your table right now.

Jeon Jeongguk looks like the kind of man who is aware that eyes are on him at any given moment and milks every single second of it to show off. His broad shoulders are the first thing that catch your attention, he fills out the jacket of his dark blue suit just right, and yet the tapering of his torso into an impossibly slim waist has you questioning if he’s even real. You stop yourself from going any lower.

His face is a whole other matter, a cocky smirk pasted onto his face, charming doe eyes that lock right onto yours as he sits back down.

“Well, for my first foray into the singles’ club, I can’t say I’m disappointed,” he lowers his voice so that only you can hear it.

Scandalized at how he’s already prepositioning you within minutes of meeting, you make the mistake of turning to face him, witnessing how he adjusts his suit jacket as he makes himself comfortable in his seat, spreading his muscled thighs under the banquet table.

“For someone who’s sole hobby is the gym, I’m surprised your vocabulary range is better than a five-year old’s,” you shoot back at him, immediately annoyed by his very existence itself.

“So you admit you think my body is nice?” He raises an eyebrow and leans into your personal space, causing you to cross your legs and angle your body away from him in response. “You aren’t wrong there, but I could give you a much better idea of what’s under these clothes.”

Your hand tightens around your glass, getting ready to swing your entire body and drench his stupid good looking face with flat, lukewarm soda, but a loud burst of laughter ruins what could have been a perfect moment of humiliation.

“Ah, _______! Jeongguk! I see you two have met!” Kim Seokjin, approaches with Kim Namjoon on his arm, and the two of them look like they are glowing with happiness. “It’s about time, I can’t believe you guys are finally here!”

Finally? What is he on about?

You stand and Seokjin gives you a warm hug, a kiss on the cheek and you immediately feel slightly better, and more than slightly guilty at almost having caused a scene at one of your closest friend’s wedding. Namjoon greets you with a bright smile as well, holding out his arms and embracing you tightly.

Having always been the more sensitive of the couple, Namjoon holds you at arm’s length for a moment. “You alright there?” Namjoon’s gaze wanders over to the table behind you, and it’s like an epiphany strikes him. “God, I’m sorry! I wanted to put you at the table with my parents, seeing as you’re already like a daughter to them, but Jin wanted you to have another chance at…”

“Love,” you grimace as you complete his sentence for him. “I’m used to it by now.”

Namjoon looks like he’s about to say something else, but then Seokjin gets your attention, his arm slung around Jeon Jeongguk’s neck.

“______, as I was saying, I can’t believe you guys only met now. Jeon Jeongguk, meet _____. The sole reason why I managed to graduate from university on time. And ______, meet Jeon Jeongguk, the reason why I almost couldn’t graduate on time.”

Jeongguk snickers and elbows his hyung in the ribs, and you stare in shock at their camaraderie. Seokjin takes in your frozen expression and gestures wildly to get his point across.

“Hello? Remember Jeon Jeongguk?” Seokjin waves his hand in front of your face. “He basically lived in our dorm for a year without even attending our school because he wanted to see what university was like. You always complained about him leaving his cereal bowls in the sink!”

No fucking way. That snot faced brat became… this?

“How you doing, _____?” Jeongguk has the audacity to wink at you. “I see you’ve grown up a little.”

You eye him up and down in shock. From what you remember, Jeon Jeongguk was a scrawny little kid who shadowed Seokjin everywhere, to classes and even to the washroom. He was just a wide-eyed high schooler who worshipped both Seokjin and Namjoon back then, and cowered at your very presence.

“I see you haven’t,” you reply coolly, inwardly praising yourself for thinking of a comeback that quickly. You will not let this stupid brat intimidate you with his looks. Just because he grew up a little and got some muscles doesn’t mean he isn’t the same person who begged to carry your books to class for you.

You remember how he basically lived as a parasite in your dorm that year, irritating the hell out of you with his messy living habits, puppy dog eyes and basically taking turns to follow you everywhere you go. Now the memories are coming back, and so are the teasing laughter from your friends who thought he was your cute little younger brother and doted on him every chance they got, not aware that he’s actually the devil incarnate.

“You guys are getting along right?” Seokjin grins from ear to ear, likely already more than tipsy. “My two bestest friends, and my husband, all in the same place. This calls for a toast!”

“We’re getting along amazingly, aren’t we, ______?” Jeongguk says with a sickening grin as he passes you a champagne flute. “In fact, she was just complimenting me on my workout routine, and I was about to tell her that I’d be more than glad to incorporate her into my home workout too-“

“Toast to the happy couple!” You immediately cut him off, feeling your cheeks burn at his insinuation, raising your glass and avoiding Jeongguk’s gaze. “Congratulations Mr Kims!”

The happy couple moves off, and in your wealth of experience, you know that the night is coming to an end, and so is the event that you dread. You start to gather your things just as everyone starts to rise from their seats to gather in the middle of the ballroom, where a space has been cleared out. Instead of making your way with the crowd, however, you go the opposite direction, ready to make the practiced and unnoticed slip away out into the night.

But this time, a hand on your wrist stops you. It’s Jeon Jeongguk, a slight frown on his handsome features.

“Hey, where are you going? They’re about to do the bouquet toss.”

You pry your arm out of his grasp. “I know.”

And without a single glance back, you slip out of the back entrance of the ballroom, unnoticed by all except one.

*

The next time you see Jeon Jeongguk, it’s at Kim Taehyung’s wedding.

It’s a lovely wedding, a little abstract for your tastes, but totally Taehyung’s style. Expensive paintings worth more than your entire lifetime’s earnings adorn the ballroom, the menu is Italian cuisine, and the wine is exquisite. Him and his blushing bride are gorgeous, the night is perfect, were it not for one tiny little…