#which is a further pushing of the monolith artist narrative

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

OMGGG the backhanded art comment 💀🤡 I wanted to say thank you sooo much for adding your input because comments like that are the reason why I have the urge to rip my hair out everytime I enter the comment section of an MV/Dance Practice like wdym "it's not dance, it's art" ?? what did you think dance was??? How little do you care about dance then?? You're literally the first person I know to address it which was kind of unexpected but very much needed (Sorry if you can feel the frustration radiating of this ask, but that's how much I despise it)

kljlkjflkjflksda well i did go to a very prestigious art school so i do have the experience to back up my backhandedness. i have to thank @exo-s-victory-lap first bc if they hadn't posted that comment on the birthday dance practice i wouldn't have said anything, bc i never read the comments on any kpop-related videos as i don't need the headache. but you're right it is a thing that very few people talk about, mostly because like i said, there's a mass lack of education around the different types of 'art' beyond painting and sculpture, and what even is 'qualified' to be called art in the first place. to be honest dance gets the most of this pseudo-'complimentary' offensive garbage because the average person in the west just does not interact with dance as an artform like, at all. the most common types of dance at the moment are street dance based/whatever shows up on tiktok and they've become so ubiquitous that people have ceased to see it as a skill and connect it to being worthy of being called 'art'. the convention of what constitutes 'art' in a lot of the general public's eyes is western eurocentric forms that have 'historical' backing, but only those that have been approved by the 'elite' as the ones acceptable. and very very few forms of dance have made that cut, so relatively few people recognize it as such.

#no one is calling pantos art and those things are old as fucking time lol. well not that old. but they are a very old form of anglo theatre#the other thing about street dance is that it was invented by black people! and god forbid anything black people do is artistic!!!!!#as someone who went to an art school where they do high concept contemporary art/the stuff that you see in contemporary galleries/museums:#the whole industry moves like fucking white supremacy and relies on the supression of 'lesser' forms in order to keep the industry running#sometimes there's actual white supremacy. sometimes there isn't. but the structure is exactly the same#there's always artists that say they want to 'deconstruct the white cube space' etc etc etc but very rarely do they actually make an effort#to cross disciplinary boundaries or go into the community/do educational outreach to ACTUALLY deconstruct those spaces#because if they actually did that it would make the entire concept of their practice pointless#the master's tools will never dismantle the master's house!!!!!!!!#n e ways. dont go to art school#text#kpop questions#answers#also there's a bias against kpop in general bc of the branding that's been pushed by western media that it's 'manufactured'#and idols themselves aren't artists bc theyre not 'making the work themselves'#which is a further pushing of the monolith artist narrative#also kr media is super guilty of this too. idols are on a really low rung on the 'artistic' ladder#so a lot of these types of comments from fans come from the desire to 'prove' that idols are worthy of making art#but they end up being insults bc kpoppies are dreadfully offensively and tragically uninformed#jokes on them the whole industry's been making art this whole time! just most of it is bad!

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

REVIEWING THE CHARTS: 27/04/2024 (Taylor Swift's THE TORTURED POETS DEPARTMENT, Drake's "Push Ups", Headie One/Stormzy/Tay Keith)

Let’s talk about Taylor Swift.

#4 - “Down Bad” - Taylor Swift

Produced by Jack Antonoff and Taylor Swift

Yeah, I’m cactus, welcome back to REVIEWING THE CHARTS, blah, blah, blah - I don’t like bending the format of this series, which actually fares quite well for a massive artist who will inevitably debut on top as it ensures a build-up to the big smash hit, but I also like reflecting the culture I write about. Taylor is such a cultural monolith in much of the English-speaking world and outside of it that despite the episode now having to end with her biggest competitor, Drake, he still doesn’t even stain this week’s biggest story, and really, only news story in an industry less and less important, and further removed from the concept of monoculture outside of freak accident white women like Taylor or Barbie than ever. Regardless of my opinions on her output, I may have to respect and reflect her sheer capability to produce discourse, reaction and most importantly, for people to actually give a shit about analysing music.

Now if we’re talking opinions on her output… you can probably get more out of me from looking at my first impressions account of listening to the new Taylor Swift album on RateYourMusic in my 2024 listening log (the account name is exclusivelytopostown). Oh, yeah, if you somehow don’t know, Taylor Swift released an album called The Tortured Poets Anthology and then two hours later, reissued it with the subtitle The Anthology, and naturally, broke all kinds of Spotify records, got a billion streams in a week, what have you. I have less to say about these individual songs than I do about the album, so I’ll try to weave it in but the crux of my takeaway is that this album’s title naturally leads to polarising results and it’s no surprise that she has compelled and practically controlled pop music and celebrity discourse for the entire week… it’s also her worst album attached directly with my favourite piece of full-length work she’s ever released.

Whilst there are plenty of in-depth reasons to compare and contrast the two releases, from here on referred to as ‘sides’ even though I’m not actually sure how the physical releases for this one worked out, the primary reasons for my stark difference in opinion lie in two fundamental components, both of which are not night-and-day between the sides, but have such a detrimental effect on my enjoyment when the two factors are combined that it ends up just as effective.

For “Down Bad”, I’ll focus on the first, and perhaps most important, reason for my preference of The Anthology: lyrics. Do not get me wrong, the second side has its fair share of strange lines and choices, as with any Taylor album, especially in her current obsessive, wordy over-sharing era, and some of its most befuddling are present on this half, making it stand out even more because of the array of lyrical perspectives that are actually on display. The second side lives up to its name, it allows for further exploration of the narrative perspectives Taylor adopts, the subtler details of decidedly unsubtle songs. I’m not saying that Taylor isn’t writing from her own perspective on all 15 tracks - there are 31 in total, of course, thank the Heavens for arbitrary singles chart rules - because she’s absolutely making parallels to if not directly referencing known moments in her life and career. The approach is adventurous, the charm returns to her clumsiness that was my favourite part of Midnights, and there are moments that can be genuinely biting and, well, poetic.

The standard edition is, for lack of a more accurate term, cringe. Again, there are absolutely moments where that is the case for side B, and I’m not claiming there’s a void of good lines… but there kind of is, isn’t there? We will always gravitate to clunkers, but what I’m more bothered by is the deadpan delivery of these lyrics, that don’t feel very Taylor-esque at times yet don’t establish themselves as a separate perspective. This is exemplified in “Down Bad”, which could be written by anyone outside from some Swiftisms in the verses, which really sound more like derivatives of her prior work rather than a signature style at this point, and really, I don’t need to explain to you why Taylor Swift should not have wriitten a song called “Down Bad”. Musically, this album spends much of its time in dull adult contemporary lightened up by Jack Antonoff synth wank that fails to distinguish the record from what came before it, so when the lyrics don’t feel like Taylor outside of when they’re at their worst, most petulant and bratty, which she fails to consistently sell because of said musical backing, it becomes a slow exhaust of four minutes… this song should really not feel this long. Hopefully now, you’ll understand what I mean in how the two components are mediocre by themselves and fail to constitute a complete package. We’ll talk more about the sonics with…

#3 - “The Tortured Poets Department” - Taylor Swift

Produced by Jack Antonoff and Taylor Swift

Musically, the first side of this album feels uninspired, a retread of steps Taylor’s been tracing alongside Mr. Antonoff for years now, with its most unique textures reminiscent of 90s adult contemporary and soft rock… it could work as utter background music if that weren’t a complete misunderstanding of why Taylor Swift works as a singer, songwriter, musician and cultural presence: an imperfect mess that has achieved unbeatable status not through style or character but through ability to craft a narrative regarding herself and everyone involved, or in some cases, allow others to craft that story for her. Taylor, despite me not enjoying a large amount of her catalogue, admittedly never made it off of bad songs: those came after the good songs, and those bad songs - the “Shake it Off”s, “Bad Blood”s, “ME!”s - were risks, paying off not in acclaim or sometimes even notable chart success, but for developing and evolving the mythos. An unstoppable force - of fans, acclaim, criticism, ex-boyfriends, cultural osmosis and Kanye - has finally made her the immovable object, and it sure sounds like it on this first side of the album, especially compared to the organic, risk-taking and more ambitious, often minimal, instrumentation that Aaron Dessner brings to the second, alongside some work from Antonoff that feels more delicate and refined, unless Taylor really wants to bring the punch in because when she takes a swing, she does it with mesmerising grace. When she misses… the album just kind of sounds like twinkly soft-rock ass.

I’m sorry, this song is fundamentally fine, but it is lost both in its production, a meandering piano jog with no compositional drive, and in its lyrical conceit of megastar Taylor having an affair with some nerd from a band I’ve been a proud hater of for years - check the archives - and mirroring Drake’s inability to explain who the fuck Jason is in “Away from Home”. I know who Lucy and Jack are, do I want to? No, do I dig the farfetched historical comparisons? Kind of, it adds texture lyrically, but it’s also as tacky as saying Charlie Puth should be a bigger artist. He’s big enough. He’s fine. I don’t even think HE wants to be a bigger artist. If it’s sarcasm, then it feels mean and if it’s genuine… maybe you should start listening more closely to the art of your friends - if that’s still accurate here - and fellow musicians that you reference in your music. Maybe there’s something there you haven’t fully grasped in all your security as the biggest artist alive: the ability to truly fail. I’m not sure Lucy Dacus, or Charlie Puth, or even Matty Healy, could survive an album as polarising as this, but once again, that mythos, that fanbase, that tree branch connection to every record and radio executive in the damn Anglosphere and beyond, it’s a comfy king-size bed to sleep on. Is the poet really tortured when they can go through the Hell of showbiz and come back to that? I don’t know, but what I do know is that the song fades out instead of ending properly, you fucking cowards.

#1 - “Fortnight” - Taylor Swift featuring Post Malone

Produced by Jack Antonoff and Taylor Swift

Inevitably, it’s her fourth #1, his second, and it has a well-directed video to wrap it all up. Self-directed, too. There’s a relatively solid foundation of this being about her relationships with Joe Alwyn and you know who. I think there’s a fascinating dichotomy that can be made if you interpret the song in different ways: the breakdown of her relationship with Alwyn, or the closing of the distance between her and bitch-face. I think the wham line of “I love you, it’s ruining my life” develops on one of my favourite songs of Taylor’s, “You’re Losing Me”, even if it doesn’t reach the same heights - or realistically, lows - instead going for a typical Antonoff synth pastiche that frankly disappoints. I think Post Malone’s presence, whilst perhaps underused, is best fit to haunting backing vocals to establish that looming male presence, and he sounds great here. The song largely goes nowhere, planting seeds it refuses to grow, but that’s a problem with the production more than anything. Like “Anti-Hero”, it’s a strong-concept, nuanced lead single that I don’t like primarily because of reasons outside of her control, and I’m just glad to wrap it up in a simpler bow that I can compare to her previous album… because Lord knows that’s what the first side of the album really doesn’t want you to do. Seriously though, this is absolutely lethargic, I can assume this felt like the best way to represent emotional numbness but there are much more unique minimal textures and patterns on the back-half, this feels cheap. Perhaps a good lead single, but terrible opener in my opinion, it really set the tone in a frustrating way. Sabrina Carpenter’s “Espresso” is at #5, Hozier’s “Too Sweet” is at #2. Welcome back to REVIEWING THE CHARTS.

Rundown

So other things happened, more than I expected, actually and to be honest, the intention is to be relatively brief. You know what the notable dropouts are but I’ll say that I cover the UK Top 75 anyway and that they are songs exiting out of the region after five weeks or a peak in the top 40, so we bid adieu to “Supersonic” by Oasis, “so american” by Olivia Rodrigo, “Been Like This” by Meghan Trainor and T-Pain, “Never be Alone” by Becky Hill and Sonny Fodera, “Praise Jah in the Moonlight” by YG Marley with uncredited appearances from Ms. Lauryn Hill, “Houdini” by Dua Lipa, “Water” by Tyla, “Asking” by Sonny Fodera, MK and Clementine Douglas, “Cruel Summer” by Taylor Swift and of course, rest in peace, “Lil Boo Thang” by Paul Russell, and welcome back to “Mr. Brightside” by The Killers. Camila Cabello’s “I LUV IT” featuring Playboi Carti is our other re-entry at #65 which is just funny if anything given this week.

As for our gains, there aren’t a ton, but a surprisingly fair few considering the amount of new entries, so I’ll note down the boosts for “Cry” by Benson Boone to #55, “FE!N” by Travis Scott featuring Playboi Carti at #53 - good week to be whatever species Carti is, I suppose - as well as “Never be Lonely” by Jax Jones and Zoe Wees at #50, “Never Lose Me” by Flo Milli at #49, “We Ain’t Here for Long” by Nathan Dawe at #47, “Back to Black” by the late Amy Winehouse at #43, “Good Luck, Babe!” by Chappell Roan at #21, “Tell Ur Girlfriend” by Lay Bankz at #18 and finally, one I’m very happy to see, the scrunkly Shaboozey at #16 with “A Bar Song (Tipsy)”. I can see top five in this one’s future, but speaking of… oh, wait, we’ve already covered it. Seven new songs! Speed round!

New Entries

#69 - “Joga Bonito” - AJ Tracey

Produced by Remedee and Nyge

The bar for cover art is in Hell. That is a PlayStation 2 model of a flag-wearing Brazilian lady showing leg, and that is now a charting single. It’s no surprise to me that Tracey is hopping on Jersey club-influenced beats, particularly with the mellow, filtered R&B sample and incredibly mundane flexes, as whilst he’s always been fun, and occasionally latches onto excellent hooks, he’s ultimately tied very heavily to trends and guest features, and this just feels a bit… empty, without a real “hook” outside of, well, its hook. He’s chatting the girl up, he says that she would look sexy in his merch, and he has the incredible bar of “I like Japan, so do you”. It must be true love. Look, if I’m going to critique Taylor for lazy writing over empty production, I can’t really give this a free pass either, even if it has some vague energy - none of it feels palpable or driving. ‘tis a shame, I tend to like Tracey’s output more consistently than other UK rappers.

#67 - “Pedro” - Jaxomy, Agatino Romero and Raffaella Carrá

Produced by Jaxomy, Agatino Romero, Steffen Harning and Reinhard Raith

Okay, this one might need some explaining. Raffaela Carrá was, and still is, a beloved icon in Italian pop music, LGBT and women’s culture, and seemingly the entire country. I’m not familiar with her at all, but that’s purely my bad: she’s sold millions upon millions of copies internationally, and released a prolific amount of albums worldwide in multiple languages. A gay icon and self-proclaimed Communist, Carrá’s classic hit “Pedro” never made it to the UK charts from release in 1980 until now, long after her passing in 2021. Latin disco by an Italian Communist sounds like I’d adore it, and for the record, I do. The original song is infectious, silly and brimmed with bombast from its obnoxious horn section to percussion so incredibly layered, especially with the snaps and claps, that it feels almost claustrophobic. Whilst far from a bad singer, Carrá brings a childlike clumsiness to the song’s hooks that define the song’s infectious personality. As someone who’s been introduced to this song literally today, it kind of feels like it’s been here for all of my life and that I’ve heard it at like seven school discos. Sicilian DJ Agatino Romero joined forces with Berlin-based Jaxomy for a pretty faithful remix that may pick up the pace and replace its rhythm section with pounding hardcore kicks, but the horns remain, because how couldn’t they? In fact, they sound even more full of life when placed onto much less organic instrumentation, from being just one element of a cacophony to a disco ball shining in your direction whilst you’re on the worst, most pounding, migraine-inducing high in a rave. It doesn’t change the song structure or even its fundamental instrumental texture a ton, probably out of respect, but that one change to the song’s arguably most important component does a lot to flip it on its head and I can really appreciate how skillfully it’s done here. Rest in peace to Raffaella Carrá, and I really hope this ends up sticking around. It’s just too infectious.

#62 - “Starburster” - Fontaines D.C.

Produced by James Ford

This is Irish indie rock outfit Fontaines D.C. with their new single about accidentally eating the Starburst with the wrapper on. Jokes aside, this is a great song. I’m not particularly invested in Fontaines as I am for some other indie and alt-rock acts that pop up here and there on the charts, in fact, I’m not familiar with their work at all, but it doesn’t mean this can’t stand on its own as one of the leading single for their next record, which I might actually have to listen to if it’s in this vein. I was initially worried given the sprinkle of pianos over lo-fi strings and James Ford production that this would be a late-era Arctic Monkeys rip but as soon as the dejected drums came in alongside that droning lead vocal from frontman Grian Chatten, it became obvious that this would functioning in a hip hop structure through way of indie rock, with Chatten actually rapping, in full Irish accent and all, over the instrumental as if it were a collection of loops instead of a live band with some smoky if typical riffs to back him up. Lyrically, Chatten details several violent analogies that seem to coalesce into sexual desire, or at least some kind of euphoric rush, intended to be purely momentary and necessary, even if it intrudes on others, if there’s a moment of bliss to be found. It’s difficult not to see this as kinky, and I honestly get a lot of mileage out of that interpretation given how its bluntness isn’t relegated to the lyrics, before of course, the strings trickle in for an ethereal bridge about swallowing and following, and Chatten asking for someone to “hit [him] for the day”, before returning to the gnarly mantra of the hook with a sly chuckle. Come on, it’s a sex jam. A weird one, for sure, one wrapped in grotesque metaphor, but I dig this on the smoky, grimed-out level it presents itself as, and maybe I’ll have to listen to whatever comes of this upcoming project.

#58 - “Gata Only” - FloyyMenor and Cris Mj

Produced by Big Cyyu

It’s rare to see Chileans chart anywhere outside of Latin America, let alone the UK, so I do want to give this some more of a chance, especially since the synth-led production at the start is a nice, promising ambiance… that gets immediately washed out by some of the shrillest synths and cheapest reggaeton percussion I’be heard in the genre. I’m not intimately familiar with the scene but I’ve heard plenty with more character, and even reggaeton that’s relaxing and ethereal. That could have been the play for these two auto-crooners, if it wasn’t for… THAT sound they keep repeating. Translating the lyrics, though of course this can lead to miscommunication, we get little of substance to chew on either. The most mush-mouthed appearance here is from Cris Mj, who was criticised by his own fans for his overly-reverbed, robotic performance before other fans convinced him that it was cool, actually, preventing him from deleting the song or at least removing himself from it as promised. I guess it turned out well as this is both acts’ biggest worldwide hit - it’s a massive deal to get a reggaeton song of all genres to cross over to little ol’ England - but if it weren’t for its inexplicable viral success, maybe he had the right idea initially in staying humble and listening to feedback. This is rote and droll in the worst kind of way because it’s in a genre that can be so exciting and weird… yet that stuff wouldn’t dare chart over here so we have these guys. I’m sure they’re nice, talented guys, but this is not compelling in any way. I can weirdly see it growing on me through some kind of subliminal hypnosis… but I don’t see myself revisiting it enough for the brainwashing to have its effect quite yet.

#41 - “Malicious Intentions” - Pozer

Produced by RA Beats

…really? Pozer? Of all possible guys in UK rap to give a second hit, it’s Pozer? The “Kitchen Stove” guy had that much potential? Whilst I have nothing against the guy, and “Kitchen Stove” is completely fine, it’s a viral breakout hit which finds its main appeal in a novel ambient sample flip taking advantage of the Jersey club wave. He does not feel built for another #41 peak, let alone however long this ends up lasting afterwards. Ironically enough, Pozer himself was the most out of place element of that song, and he seems to have understood that. Does that mean he’s changed his flow and delivery to fit a more chill and atmospheric tone? No, not at all. He’s ditched the ambient sample, replacing it with a wave of synth strings that sound pretty triumphant and play off pretty well against incredibly bass-heavy and driven Jersey rhythms less bothered with fancy percussion additions, and more with the sheer intensity of the 808s, slowly and gradually developing into a more traditional drill beat through the eventual addition of enough additional drums, it’s a really cool idea for an instrumental, especially when it reverts to pure numbing intensity for the chorus, and serves well for what Pozer is going for: an incredibly consistent flow delivered much livelier and with a significantly bouncier, funnier grit than before, and bars that really aren’t bad. Pozer also adapts very seamlessly to the changing rhythm of the beat, and his more introspective moments stick out as perhaps surface-level but particularly potent when delivered with the same restlessness as any other bar. Unrelenting feels like a good way to describe the song, always punching and punching a bit beyond its weight and getting reversed back - and that’s the rhythm. Whilst it’s not reinventing the wheel, this is genuinely pretty infectious and difficult to not get excited to, in spite of - or because of - Pozer’s acquired delivery that takes a while to get used to but shares its realm more fairly than you’d think with such great production and a rapper I didn’t think much of until today. Well done, man, this is an unsettling piece of production that is transformed by the confidence of the rapper on it, and for that, I really dig it.

#33 - “Cry No More” - Headie One featuring Stormzy and Tay Keith

Produced by Tay Keith, Pooh Beatz and Tommy Parker

Speaking of promising UK rap, here we have Headie One with yet another single from an upcoming project titled The Last One. Whether this is a full retirement, we can never tell with rappers. But would this be a strong farewell verse? Well, yeah, it’s impeccable for Headie, it feels like a perfect example of what he does well: a cold staccato verse that runs like a train, punctuated by dejected ad-libs and delivery and paranoid, detached bars revolving around gang violence over tight drill percussion and some of the best mixes I’ve heard for a drill beat: it all sounds crisp to me, especially that warping bass. The sample may not be the most interesting melody to go for over this beat, but its sing-songy tone reassures its ability to be both eerie and anthemic, alongside the incredibly clever implementation of Asake’s “Lonely at the Top” - which peaked at #90, though weirdly I did review this one - in Stormzy’s verse. How it doesn’t feel tacky is beyond me, it feels like a genuine shout-out that matches the tone of the song perfectly and leads into the flex in a subtler way than he probably would have done without it. Notably, Stormzy goes for a similar flow to Headie but kind of shelves him in the wordplay and rhyme scheme departments, even if neither are too lyrical here, mostly showcasing a clash between the images they have to maintain and the real people behind them, though some of that may be unintentional given all the flexing that surrounds it, especially in Stormzy’s verse where they’re so well-intertwined. I was expecting to like this, but came back with even more to chew on than I thought I would, so I’m glad that, even if only for that big debut week and a few more, it can land on the chart, this is great stuff. Hyped for whatever forms out of this and “Marvin’s Sofa”, honestly two of Headie’s best singles leading up to this forthcoming record so expectations are high.

#14 - “Push Ups” - Drake

Produced by Boi-1da, Tay Keith, Preme, Fierce, Dramakid and Noel Cadastre

I’m not Kendrick Lamar so who cares what I think about a Drake diss? Genuinely, what purpose would it be for me to sit down and analyse bars that have been thoroughly annotated on Genius already, discussed and taken apart by hip hop podcasters and influencers, if not other rappers, and in some cases, went completely viral? There’s a mix of corny and clever bars here, mostly in the latter which is impressive for late-era Drake, and I hate to say he has some points regarding what seems to be a convenient, preplanned attack on Drake that just confirms his suspicion and contributes to his own narrative. The beat is hard, the mix is rough but it’s a diss track so that is the least of anyone’s concerns. I assume the abrupt beat switch, after a DJ Akademiks meme inserts itself into the song like the leech he is, is a demonstration of Drake having more bars to come, but given there’s only one real punchline in that section, it feels like a long build-up to nothing and a strange decision to include overall as an epilogue. Otherwise, it’s a fun, venomous track with some of Drake’s most well-thought-out and honestly, well-delivered bars in years. It’s crunchy, it’s to the point, and I’m excited for what Kung-Fu Kenny has to say in response.

Conclusion

He’s not getting Best of the Week though. A cool diss doesn’t always equate to a memorable or replayable song, and for me, I think Pozer of all people has the most infectious here, colour me surprised, with the evil-sounding “Malicious Intentions”, but I’ll tie him with the more joyful “Pedro” by Jaxony, Agatino Romero and the late Raffaella Carrá for a more balanced Best of the Week. Hell, there’s enough good stuff here to tie the Honourable Mention up two between Headie One, Stormzy and Tay Keith for “Cry No More” and “Starburster” by Fontaines D.C. As for the worst, it should unsurprisingly fall out quite easily: Taylor Swift has Worst of the Week for “Down Bad”, with the Dishonourable Mention going to “Gata Only” by FloyyMenor and Cris Mj. For what’s on the horizon, I mean, hopefully more good to look forward to but knowing my luck… I don’t know, Bladee? For now, thank you for reading, rest in peace to Mike Pinder, and I’ll see you next week!

#uk singles chart#pop music#song review#taylor swift#the tortured poets department#post malone#drake#push ups#headie one#stormzy#tay keith#raffaella carrà#agatino romero#jaxomy#fontaines d.c.#floyymenor#cris mj#pozer#aj tracey

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

David Michelinie: A Master Storyteller

David Michelinie, a revered luminary in the domain of comic book scripting, stands as a beacon of influence in the vast Marvel Comics realm. Through his exceptional narrative prowess, Michelinie has etched an unforgettable legacy in iconic series like Iron Man and Spider-Man, enchanting readers with his imaginative storylines and character evolution

Marvel Masterworks by David Michelinie

A standout collaboration for Michelinie was with his counterpart Bob Layton on Iron Man, a partnership that exemplified creative synergy at its zenith. Together, they revitalized the character, pushing boundaries and exploring intricate themes that resonated profoundly with audiences. Their work on Iron Man, notably in groundbreaking issues like "Demon in a Bottle" (Iron Man #120-128), showcased Michelinie's talent for delving into profound character arcs and addressing real-world issues within the superhero genre

"Demon in a Bottle" received critical acclaim for its portrayal of Tony Stark's struggle with alcoholism. The storyline was praised for its realistic depiction of the issue and its impact on the superhero genre. It resonated with audiences and even garnered recognition from NGOs dedicated to assisting individuals dealing with alcoholism

Regarding the "Doomquest" story, this arc involves Iron Man and Doctor Doom ending up in Camelot due to time travel. The storyline showcases an intriguing blend of time-travel elements with the superhero narrative, offering readers a unique and captivating adventure featuring two iconic characters in an unexpected setting

"Armor Wars" is a notable storyline in Iron Man comics that was written by David Michelinie and illustrated by Bob Layton. In this storyline, Tony Stark discovers that his technology has been used by others without his permission. This leads him on a mission to reclaim and destroy his stolen technology to prevent it from falling into the wrong hands. The "Armor Wars" storyline not only showcases Tony Stark's determination and resourcefulness but also delves into the consequences of his actions and the ethical dilemmas he faces. Michelinie's storytelling and Layton's artistry in "Armor Wars" further solidified Iron Man's character development and contributed to the complexity and depth of the series

In addition to his contributions to Iron Man, Michelinie played a pivotal role in shaping the world of Spider-Man, another cornerstone of the Marvel Comics universe. His work on storylines after Tom DeFalco's "The Alien Costume Saga" (The Amazing Spider-Man #252-259) would make us see the black symbiote suit evolve into the notorious villain Venom thanks to it finding a new host in Eddie Brock in the Amazing Spider-Man #300. Michelinie's talent for crafting engaging narratives and creating compelling characters solidified his reputation as a master storyteller within the comic book industry

Marvel Masterworks by David Michelinie

Beyond his work on Iron Man and Spider-Man, Michelinie's creative influence extended to a myriad of other Marvel characters, including Daredevil, the Avengers, and the Hulk. His most underrated works are for Marvel's Graphic Novel line in the 80s for which he wrote Avengers: Emperor Doom, The Aladdin Effect featuring the Wasp, Storm, She-Hulk, and Tigra, and The Revenge of the Living Monolith starring the Fantastic Four, the Avengers, and Spider-Man

Through collaborations with esteemed Marvel artists such as Bob Layton, John Romita Jr., Bob Hall, Greg LaRocque, Marc Silvestri, Todd McFarlane, and Mark Bagley, Michelinie brought visual richness to his captivating storylines, seamlessly blending art and narrative to captivate readers

Michelinie's collaboration with Todd McFarlane on The Amazing Spider-Man marked a significant chapter in his illustrious career in the realm of comic book writing. Together, Michelinie and McFarlane worked on key issues like the "Assasin Nation Plot" storyline (The Amazing Spider-Man #320-325), where Spider-Man gets tangled in an international conspiracy to murder a head of state. This arc showcased Michelinie's ability to push the boundaries of traditional superhero storytelling, adding layers of complexity to the character and exploring new dimensions of Spider-Man's abilities and challenges

Additionally, Michelinie's partnership with Todd McFarlane led to the creation of visually striking and dynamic action sequences that captivated readers and solidified their place as a dynamic creative duo within the Marvel Comics universe. For starters, they both created Venom (Eddie Brock)

With Mark Bagley, his biggest highlight would be in the "Maximum Carnage" crossover event in which Michelinie made significant contributions to the Spider-Man series. Firstly, he and Mark Bagley co-created Carnage, a valuable addition to both Spider-Man and Venom's rogues galleries who would then inflict "Maximum Carnage" on New York. The event featured a massive battle involving Spider-Man and other Marvel characters against the villainous Carnage and his team of supervillains. Michelinie's storytelling in "Maximum Carnage" added depth to the Spider-Man narrative and further established his reputation as a skilled writer in the realm of superhero comics. Overall, Michelinie's collaborations with both Todd McFarlane and Mark Bagley further solidified his reputation as a master storyteller and enriched the Marvel Comics universe with memorable and impactful narratives that continue to resonate with fans and readers alike

David Michelinie's enduring legacy in the realm of Marvel Comics stands as a testament to his storytelling prowess and his ability to forge deep connections with readers. His contributions to beloved characters and iconic storylines have left an indelible impact on the comic book landscape, inspiring generations of fans and creators alike. As a visionary architect of the Marvel Universe, Michelinie's work continues to resonate with audiences, ensuring that his legacy will endure for years to come

Marvel Masterworks by David Michelinie

1 note

·

View note

Text

Asians 4 Black Lives: Structural Racism is the Pandemic, Interdependence and Solidarity is the Cure

The COVID-19 pandemic has driven a new surge in violence against Asian communities across the world. Several high-profile instances of anti-Asian racist violence—spurred on by casually racist remarks at every level of government, business, and popular culture—have created a terrorizing climate for many. In San Francisco Chinatown for example, overt xenophobia, combined with the economic impact of shelter-in-place orders, has left immigrants, elders, limited English-speaking people, and poor folks feeling like targets. In San Francisco, where a staggeringly disproportionate 50% of the COVID-19 mortalities are from the Asian and Pacific Islander community, the pandemic has ushered in multiple violences. This has been further exacerbated by pre-existing crises: gentrification, displacement, homelessness, police terror, inequities in education, a drastic uptick in deportations, antagonism against trans and queer people, poverty, and exploitation.

Nationally, Black people are dying from COVID-19 at rates twice as high as other groups, an outcome of deeply embedded structural racism in healthcare, housing, labor, and other policies. Communities are weakened from decades of housing discrimination and redlining, forced denser housing, targeted criminalization and incarceration, larger numbers of pre-existing health conditions, and less access to affordable healthy food. Black communities are more likely to live in places with air pollution, rely on public transit, and be essential workers, so exposure rates increase. When Black people fall ill with COVID-19, racism in the healthcare system means lack of access to quality care, testing kits, or funds for treatment. In some cases, like for Zoe Mungin, they are simply not believed and turned away from treatment, until it is too late.

We must recognize that the scapegoating of Asians as the harbingers of disease and the state violence against Black people (via systemic policing and state response to the pandemic) are two sides of the same coin. This system of oppression is what indicates whether we live or die. This moment makes it even clearer that we must radicalize our communities for cross-racial solidarity.

Asians and Anti-Blackness in the US

Asians in the US are not a monolith. Some of us are first-generation immigrants who came here to work under selective immigration policies that privileged our education and technical skills. Some of us are here through involuntary migrations—fleeing economic and military wars waged in our homelands by the US and other imperial powers. Some of our Asian families have been in the US for generations. Some of us were adopted from Asian countries by non-Asian families. Some of us are mixed-race and of Black and Asian descent. We cannot ignore the varied experiences and distinctions between how our people got to this land, our familial and community histories in the US, and the way in which mainstream American perceptions and portrayals impact us differently. What we do have in common is that we’re incentivized by capitalism and racism, particularly anti-Blackness, to hold up the dual evils of white supremacy and American imperialism.

In order to fight back, we need to be more informed. That means understanding how we’ve been asked to buy into this system and to uphold ideas, policies, and practices that ultimately go against our interests. That also means being active and vocal supporters of Black liberation, and taking responsibility to end our anti-Blackness. We must acknowledge that anti-Blackness is at the core of all racism and that non-Black Asians have benefited—conditionally—from a system of anti-Blackness politically, economically, and socially. See our statement on recent police killings of Black people for more on this. It also means understanding how the history of racial capitalism has impacted all our communities and continues to impact us.

A Shared History of White Supremacy and Imperialism

Today the current administration is seeding a second Cold War with China to protect its financial interests globally and in the Asian Pacific. Stateside, we see results of this expressed as public figures repeatedly call COVID-19 a “Chinese virus” or a “Kung Flu,” directly resulting in vigilante attacks on people of Chinese descent, or people perceived to be of Chinese descent. In the summer, we’re seeing an uptick in COVID-19 cases as states push for “re-opening,” in part so that the state doesn't have to pay the brunt of unemployment benefits. This puts frontline workers (who are disproportionately from communities of color) at further risk—a decision not made off science but because of the drive for profit. In 2014-15, the Ebola outbreak also became a racialized pandemic, sparking widespread fear of African countries and a globalized anti-Blackness by Western countries.

We’ve seen this before: racist rhetoric, scapegoating, and, eventually, military tactics that target and intimidate communities of color to reinforce US capitalist priorities domestically and imperialism abroad. During World War II, fear of military threat by the Japanese government and fear of the economic influence of people of Japanese descent in the US led to the racist mass incarceration of Japanese Americans. Despite this despicable history, racist pundits have recently claimed the incarceration of Japanese Americans actually sets legal precedent for the targeting of other communities of color in the post 9-11 era. US government officials used Southwest Asian, North African, Muslim and South Asian communities as scapegoats during the “War on Terror” which put a huge target on their backs for vigilante violence, created massive surveillance and state-sanctioned harassment programs, and provided a cover for starting endless wars in the Gulf and West Asia for geopolitical dominance. During the rhetoric leading up to the various iterations of Trump’s travel bans we saw xenophobic language like “shithole countries” targeting both Muslim and African countries. We know that within the system of immigration surveillance and detention, Black immigrants are disproportionately targeted and deported.

We also know that the modern US police force was created in the antebellum period as patrols to hunt down people escaping slavery. Their present-day incarnation has been further solidified through continued targeting of Black communities as well as cracking down on unions and workers fighting for fairer wages and decent working conditions. Similarly, prisons are the contemporary progenies of slave plantations. These systems are undergirded by a dominant white supremacist narrative that insinuates Black people are inherently criminal and Black communities and families are irreparably broken. These narratives—built on more than 500 years of slavery, Indigenous genocide, and the theft of Native land—protect white owning-class privilege and power while resulting in death, disempowerment, and suffering, which disproportionately impact Black and Indigenous communities. These dominant systems, and the narratives that support them, have a firm grip on every aspect of contemporary US life. Understanding these critical connections is required political education for all—a more strategic resistance enables growth and strength across multiple communities of struggle. Without this, our communities are more vulnerable to counterproductive responses.

Moving Away from Counterproductive Responses

Unfortunately, in response to the rise in anti-Asian violence during COVID-19, we’ve seen vigilante groups form, bent on taking matters into their own hands. These responses reinforce the violent systems and narratives we want to dismantle. One such group that we’ve learned about in San Francisco Chinatown is composed of some ex-military. They have claimed they would perform citizens’ arrests, and have surveilled people they deem “suspicious,” and called the cops on them. Based on historic biases of the police and military, the folks targeted by this vigilante group have been Black, poor, unhoused, disabled, or a combination of the above. As we’ve seen for decades, police kill Black people at rates six times that of white people. This group has even co-opted language from the movement for Black lives in order to seem more sympathetic. Utilizing policing tactics like “patrols” and engaging in military-style surveillance and harassment of Black and poor people is an escalation and expansion of violence—not successful harm-prevention.

In this moment of the pandemic and uprisings, there is an opportunity to pivot to the future our communities want and need. Rather than attempting to solve the issues we’re facing by using tactics that replicate harm, we ask ourselves and each other: What new systems of support and care can we build and grow so that the world can be better? Asians cannot afford to hold on to the meager protections given to us by white supremacy; we can no longer be conscripted to fight the battles of white supremacy and American imperialism on its behalf while simultaneously being harmed by these systems. We need to recognize that our liberation is tied to our interdependence and solidarity.

Our Liberation is Intertwined

Hyejin Shim, queer Korean and prison abolitionist, poses an essential question: “What are the legacies we’ve inherited, which ones will we choose to protect?” In her piece questioning the limits of Asian American allyship, Hyejin reminds us that as Asian Americans, we have a rich, deep legacy of “Asian American prison abolitionists, anti-war activists, racial justice organizers, disability justice freedom fighters, queer/trans feminists & anti fascists, immigrant rights organizers, housing justice organizers, rape and domestic violence survivor advocates, labor organizers, artists and cultural workers, movement lawyers, and so many more, from both the past & present.” In all of these movements, Asian Americans have struggled alongside their Black siblings, with an understanding that our liberations are intertwined.

Again, Black and Asian solidarity in the face of systemic oppression is not new and we should continue to draw lessons from our vibrant shared history to inform our current and future work organizing for a more just society.

Early 1900s: Black US troops desert to join Pilipino independence fighters.

1969: Black, Asian, and Latinx students at San Francisco State University successfully lead a strike to create the first-ever Ethnic Studies program.

1970s: The Black Panther Party supports Pilipino residents of the International Hotel in their fight against eviction.

2006: After Hurricane Katrina, Black and Vietnamese communities in New Orleans protest the use of their community as a makeshift dump site.

2020: Black and Asian communities in New York lead a movement to Cancel Rent, focused on immigrant, undocumented, and homeless communities.

(For more on the above examples, check out these zines by Bianca Mabute-Louie!)

Grounding in Interdependence and Solidarity

In addition to deepening our understanding of our shared histories, we should deepen our interpersonal relationships—our trust. We should continue to build out the mechanisms through which we tangibly support each other. As Stacey Park Milbern—a dearly beloved queer mixed race Korean comrade and disability justice movement leader who recently passed away—taught us: “We live and love interdependently. We know no person is an island, we need one another to live.”

This month, hundreds of thousands of people flooded the streets, decrying the police murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and so many more. The people are mobilizing to uplift calls from Black organizers to defund the police while imagining and implementing alternatives to policing that actually promote community health and wellbeing. It’s a beautiful sight to behold and we must not forget that this incredible and rapid mass mobilization is a direct result of the tireless and intentional work of organizers who move in between these flashpoint moments: people who do the unsung work of cultivating and deepening interpersonal relationships over decades, holding difficult and educational conversations, supporting members through personal challenges, and creating venues for community to celebrate victories and accomplishments.

Deep, intentional relationship building is central to laying the foundations that make change possible; at the same time, it is not just a means to an end. Trust and interdependence are ends in themselves. As Asians 4 Black Lives, we aim to live out the world we are fighting for, and our deep comradeship and friendship is core to how and why we show up. For example, we have taken up the practice of beginning each of our regular meetings with personal check-ins: Do you have any needs that our community can help you with? Do you have any resources or bandwidth you can offer to community? We are often wrestling with the complexity of what it means to be people of Asian diaspora living in the United States and in joint struggle with our Black, Indigenous, and other comrades of color. This extends our questioning into deeper political territory: What, if any, is our role as US-based Asians in addressing anti-Blackness in Asian communities abroad? What does it mean to be called #Asians4BlackLives when that phrase is being used as a rallying cry for so many who express their solidarity in ways we may not be aligned with? Our work raises important questions that help us sharpen our analysis and build stronger ties with each other and the communities we are accountable to.

Whatever the world throws at us, be it interpersonal violence, a novel coronavirus, climate change, or vigilante racism, we know that communities are most resilient when basic needs are met. As others have noted, wealthy, predominantly white communities have much lower rates of policing and longer life expectancies than lower income communities of color. This isn’t because rich people or white people are less predisposed to do harm, or because they are physically or biologically predetermined to be healthier, but rather that these communities are allocated more resources and support structures. These communities are given more chances to address violence without being criminalized, but this often empowers people with privilege to continue causing harm without facing consequences. Instead of this model, we strive for a world where everyone’s needs are met and new systems help us address real issues of health and harm without relying on the carceral state.

The good news is we’re seeing more and more Asian communities move towards redistributing resources of time, money, and energy in this moment. Asian volunteers are phonebanking and getting donations pledged to Black groups—directly. Asians are encouraging each other to speak to their families and communities. Asians are supporting the campaigns and creative direct action efforts of Black-led groups to win the defunding and abolition of police and prisons. Asians are setting up strong alternatives to relying on these systems for safety. It is a powerful moment of mobilization.

As COVID-19 shifts social relations in unprecedented ways and oppressive forces leverage the pandemic to stir up fear and anti-Asian racism for their own benefit, we must resist the temptation to put up walls and isolate ourselves. It’s essential that we be resilient and creative in the ways we stay close. Let us continue to deepen our trust and ground ourselves in our rich legacies of solidarity. Let us leverage our collectivizing strength as we fight for a world that centers humanity, dignity, and the space to thrive.

#Asians4BlackLives#AsiansforBlackLives#BlackLivesMatter#BlackHealthMatters#Pandemic#Solidarity#Public Health#Health#COVID-19#COVID19#Coronavirus#Racism#Interdependence#Asians for Black Lives#Black Lives Matter

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Total Exit: on the Queer Cinema

(Basis for introductory remarks given at QFFxBQFF screening ‘Burning Ones’ at the IMA, March 8, 2018. )

Already, by the 1940s, the feeling was that the cinema had become “a medium of and for bankers,” that the time had passed in which a film could be both commercial and artistic, both public and personal. (Renan 18) Doubly constrained by market concerns and the 1930 Hays code (which forbade depictions of more than thirty unsavoury topics including interracial relationships, childbirth, sexual deviance and mockery of the church), the Hollywood studio system mastered the endless reproduction of tepid, escapist fantasies sure to appease audiences and censors alike. At its peak, the studio system churned out more than five hundred such features every year—and individual screenwriters, directors and actors working in that system understood well that they were replaceable, at a moment’s notice, if they threatened to disrupt either the consistency of the product or the relentless speed of the process.

Against this stultifying current emerged the underground cinema: a loose, international affiliation of artists working totally outside and in opposition to the studio’s production-distribution-exhibition machine. Where Hollywood had perfected filmmaking as the output of a bland and homogenous product, the underground sought to challenge every preconception of what a film could be, to be both radically personal and fearlessly experimental, and to explore any and every idea and subject deemed unfit for public consumption. Underground films could be twenty seconds or twenty hours long, narrative or abstract. Images could be traditionally shot, painted or scribbled right onto the stock. They could re-appropriate footage from other films, advertisements and newsreels; they could even mock the church. In a postwar society that had veered sharply conservative, the underground cinema acted as both a venue and method for exploring new ideas and questioning societal norms without fear of public persecution.

It is no surprise then, that while the movement began as a small group of artists making and screening films almost exclusively for one another, it quickly attracted those whose identities, sexualities, loves, ideas, class or politics excluded them from mainstream representation and mainstream society alike. By the 1950s, the underground had become a vital space, not only for artists to seek new forms of self-expression, but as a meeting place for queers and commies of all kinds—one of the few spaces which permitted open communication, the exchange of ideas and phone numbers, experimentation, exploration and transgression, both on-screen and off-. The commercial film epitomised the double-ideology of the “normal person” and the “normal story”, each reinforcing the other in a perpetual, closed loop. In their works, the underground sought to break entirely from this vicious circle, and it is this exigence of total flight to which all three films on tonight’s program respond.

In Jean Genet’s ‘Song of Love’, a prison guard cruises a dark, one might say mazelike hallway, spying on the prisoners’ various displays physical and sexual release. But there is one prisoner in particular whom the guard truly desires, and his voyeuristic pleasure sours into jealousy when he realises the prisoner yearns for someone else. Two fantasies—the prisoner’s and the guard’s—bleed into one another as the guard bursts into the cell and lashes the prisoner in an ecstatic outburst in which lust and hatred, acknowledgement and punishment become indistinguishable.

For Genet, as is well known, the criminal, poet and homosexual are but a single figure: the prisoners communicate their desires in their own language of smoke of flowers. Though they are physically confined, they exude an unrestrained sexuality in every frame of the film. In Genet’s world, it is the guard, which is to say the state, who wields all the power and yet remains impotent, who cannot join the prisoners. Unable to reconcile his contradictory desires, he (the guard) is the one finally expelled from the prisoners’ erotic liminal space.

Gregory Markopoulos was one of the earliest filmmakers to take up love between men as an explicit and enduring theme. While it is true that his films are intensely personal—so much so that he tried at one point to withdraw them from circulation entirely—their autobiographical details are fragmented, disturbed by, as Renan puts it, “[an] editing technique that obliterate[s] the plot if one [does] not know it.” (87) Even when, as in Swain, Markopoulos draws directly from a literary text, story remains subservient to an almost phenomenological method which conveys above all the experience of queer desire. At a time when homosexual experiences and encounters could exist only in marginal spaces, fleeting moments and coded signals, Markopolous’s films likewise remain hidden in plain sight, unfolding in a discontinuous style in which his characters’ pasts and presents, thoughts, fears and fantasies intermingle. We find in them a yearning for an impossible domesticity—a tranquility shattered, over and over, by intrusive memories and images that spill over the screen almost faster than the eye can catch.

Jack Smith’s ‘Flaming Creatures’ has a history of obscenity trials, clandestine screenings, police raids and arrests so extensive that it would overshadow perhaps any other film. When a Belgian film festival declared it an undeniable aesthetic achievement and banned it from screening in the same sentence, a friend of Smith’s smuggled the film into the country and held packed screenings in his hotel room. When the film had likewise been banned in New York, a vigilante projectionist at a commercial theatre, barricaded himself in his booth and screened the film for as long as he could before authorities cut off power to the entire building. (Benshoff 120)

‘Flaming Creatures’s polarising influence, its history both of outraged suppression and equally fervent support, is well-deserved. Structurally, visually, and thematically, it has almost no precedent. Made a year before Sontag’s famous essay, ‘Flaming Creatures’ was one of the first films to consciously develop what we now call ’camp’, and at the same time pushed that aesthetic further than perhaps any other film since. The result is a shocking farce; kitschy and obscene, consciously—almost studiously—opposed to every dictum of good taste. Visually, it is a pastiche of rococo, orientalist, drag and B-movie aesthetics: humans of utterly ambiguous gender identity frolic about in kimonos, flapper dresses and ball gowns, costume jewellery and tumescent prosthetic noses. Their activities reach a screaming, orgiastic climax until an apocalyptic earthquake kills them all. Then, the whole thing happens again.

In his own life and writings, Smith opposed not only the white, hetero-patriarchal establishment but the so-called ‘assimilationist’ LGBT intellectuals, who argued that the only path to mainstream acceptance was meek compliance with the mainstream status quo. Smith, by contrast, saw quote-unquote normalcy as a restrictive and repressive ideology which should be resisted and lampooned in every possible respect. ‘Flaming Creatures’ is a free and irreverant fuck-you to every preconception, expectation and standard of good taste. It is structurally and visually disorienting, a confounding and ridiculous nightmare, which nonetheless harbours a kind of utopian vision: the film’s characters are truly “creatures” as the title implies—without gender, without boundaries, existing beyond even life and death. Smith himself said of the film that he wanted to explore every conception of beauty, and, once we have acclimated to its style, the film offers just that: a joyous affirmation of both the glamorous and the tacky, of every kind of body, of cheap wigs and jiggly dicks.

Queer popular culture still echoes the innovations of the underground, in its gleeful mockery of conventional gender signifiers, for instance, or in its embrace of camp as a rejection of academic distinctions between ‘high’ and ‘low culture’, or ’serious’ and ‘silly’ art. Yet, as exemplified by RuPaul earlier this week, the ultimate triumph of the assimilationist agenda over the underground’s rejectionist project has come at the cost of a reabsorption of mainstream hegemony into the queer world, and a recodification of social and sexual roles in a community that once strictly opposed performative roles of every kind: As Rees-Roberts argues, “‘Images’ of mainstream integration,“ have disproportionately favoured “conventional, straight-acting, young, white, middle-class gay boys, [reinforcing social hierarchies of] LGBT identities, racial difference, gender inequality, [and] economic privilege.” (1-2) Much of queer cinema, like much of queer culture, has likewise acquiesced to mainstream standards of normalcy and acceptability, but in exchange for an acceptance which is not offered equally to all.

What the underground filmmakers understood, what has often been obscured in subsequent, audience-friendly depictions of safe, queer love, was the urgent need of resistance to the prevailing status quo and all of its social, political, intellectual and economic mechanisms of control. The films come from a time when to be queer already meant to be an intellectual and political adversary of the state; to be experimental or personal as a filmmaker already meant to oppose the monolithic, monopolistic and moralising Hollywood system. The queer underground grasped clearly that, in every case, it is one voice which divides titillation from transgression, the aesthetic from the abhorrent, which in one decree states what is good, what is moral, what is legal and what will sell; one voice which sings the song of a tasteful society of progress and progeny. In the underground there emerged against this voice another one of total dissent, a break so radical that it still eclipses much of what has come since. Here, artists imagined utopian futures which have not yet come to pass, and, if we have truly abandoned the ceaseless critique of our own present, perhaps never will.

Cited:

Benshoff, Harry and Sean Griffin. Queer Images: A History of Gay And Lesbian Film In America. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield 2006.

Rees-Roberts, Nick. French Queer Cinema. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP 2008.

Renan, Sheldon. An Introduction To The American Underground Film. New York: Dutton 1967.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bloog Entire Entry2

Alright so here we go another instalment of talking about stuff I like. It’s been a little while since the first entry in my second attempt at blogging and since then I finished a couple of things I was reading, and I’ve made further developments with my summer film which I will talk about this time.

First off, I finished reading A Princess of Mars by Edgar Rice Burroughs. While I was reading this book I thought it was what someone refers to when they say “pulp fiction”, it’s really not pushing any boundaries in the sci-fi genre, it doesn’t flesh out it’s characters and the hero saves the world and gets the girl with very little difficulty. As the protagonist John Carter is from Earth, once upon Mars the lesser gravity grants him super strength, not only this but the telepathic means of communication used by the martians is no obstacle for him, as he seems to be fully capable of using the ability to a higher level than the martians the moment he arrives on the planet. You never really feel like he is in any true peril, and if the book was much longer it may have gotten a little boring, however as is the theme with pulp fiction the book is a fun read for the short time it takes to read it. A Princess of Mars doesn’t provide grand new ideas or a deeper look human realtionships, but it does give a very dungeons and dragons feeling approach to sci-fi, with monsters, duels, a war between species, dungeons, princesses, tyrants and handsome Conan style protagonist. Now, upon finishing this book I wanted to send a friend a picture of the cover, I looked at the inside cover to find an artist’s name and was frankly shocked to see that this book was first published in 1912, and what I though to be a fairly rudimentary sci-fi was actually crazy ahead of it’s time. Props Edgar.

Just recently I have finished a series I mentioned in my last entry, Akira. Katsuhiro Otomo’s mastapeece spans 6 large books each costing around £15-£20 and can be easily read in one or two sittings, so it’s fair to say Akira is not particularly cheap to read unless you want to read it online which unfortunately grosses me out just thinking about. Frankly I’m glad I splurged and bought the books, Otomo’s work is in my opinion unrivalled in terms of it’s appeal and a must have for any weeb’s manga collection. It never ceases to amaze me when reading any manga that most of what is produced is created by a single person. It seems with most manga, the artists have spent their entire lives becoming intensely skilled in illustration, and a lack of ability in writing good narratives is occasionally present. As I was saying about A Princess of Mars, not every story has to be an incredible feat in storytelling, but in more mangas that not, the narrative comprises of a protagonist who walks around and fights a guy, then finds a stronger guy and beats him, then finds a stronger guy and beats him, and so on. It clearly doesn’t deter me from reading it as there are lots or other elements of creativity outside the overarching narrative, along with incredible artwork, however Akira is the first manga I’ve read that has strayed so far from the norm, juggling many different characters with integral roles in the story, protagonists who’s moral compass is far from perfect, and antagonists with complex motivations. Not one person is solely responsible for any big plot points, and at no point does a character fully understand what has happened or will happen. This juggling of information is reflected in action sequences, often having many different groups, all with different goals colliding together in huge set pieces, there is so much going on at one time that you can’t help but read quickly, and at times it feels like such a clusterfuck, but really that’s probably how it would be in real life. The amount of information in Akira is just handled so well that I never felt lost, it doesn’t fail to answer questions then call it abstract, it is a wholly satisfying read and deserves it’s title of one of the greatest manga ever made...

The film’s pretty good too.

Finally I’ll talk a little bit about my summer project. I decided to make an adaptation of the ending of The Time Machine by H.G. Wells, as a whole the book is good, obviously with historical context this book was a huge jumping off point for story telling, however objectively it doesn’t delve into the possibilities of time travel as much as other more modern stories have done. Effectively a turn of the century scientist in London invents a time machine, travels forward to a point where humans have evolved (or devolved) to a point of being vastly different, he farts around a bit then go’s home. However just before he does so he travels further forward to the Earth’s last years, it’s drifted out of orbit and nothing grows except an algae like plant on the surface of rocks. The sun now only drifts above the horizon, and for some reason there are giant crabs and moths. The description given of the dying Earth was really appealing to me, something about it being at the very end of the story and was unintentionally witnessed by the time traveller made it feel beautiful but a little bit spooky. The evolution of my adaptation has proceeded into the production stages. Quite a few of my visual ideas have just come from making it and things coincidentally happening then deciding to go for it. I am about of third of the way through animating and haven’t made an animatic which I know is a terrible idea but I’m going with it. The found that the longer I’ve gone not sticking to any sort of plan the further away from the original text I’ve gotten, however the key things I liked about it are still there and to be honest I like that it doesn’t look like any other adaptations. From what I’ve done so far there are influences from everywhere, my time machine looks like the monolith from 2001, the rocks look like Junji Ito’s work, the time machine controls are inspired by my keyboard. I know what I still have to do and I have about a month to finish it. The only issue I see in the foreseeable future is sound, as I haven’t done an animatic I have no idea if I’m having any music or not, and what sound effects to use. I’ll probably just wing it in Premier.

0 notes

Text

Some Thoughts About Richard Serra and Martin Puryear (Part 2: Puryear)

Like Serra, Puryear went to Yale’s famed M.F.A. program (1969–71), but he attended five years after Serra had graduated. In fact, Serra and Robert Morris were visiting artists while he was a student there. During his time at Yale, he studied with the sculptor James Rosati and took a course on African art with Robert Farris Thompson and a course on pre-Columbian at with Michael Kampen. Before attending Yale, Puryear had studied at Catholic University of America, Washington D.C. (1959–63), where he got a B.A in Arts; worked in the Peace Corps (1964–66) in Sierra Leone in West Africa; attended the Swedish Royal Academy of Art (1966–68); and took a backpacking trip with his brother in Lapland, above the Arctic Circle. By the time he attended Yale, Puryear was what the poet Charles Baudelaire would have characterized as “a man of the world.”

From the outset of his career, Puryear refused to give up what he knew and studied in order to align his work with the prevailing aesthetic. Some people believe they should do whatever it takes to fit in, while others accept that they will never fit in and do not try. There is the assimilationist who wants to be loved by everyone, and there is the person who knows that this kind of acceptance comes with a price. In Michael Brenson’s article, “Maverick Sculptor Makes Good” (New York Times Magazine, November 1, 1987), this is how Puryear described his response to Minimalism:

I never did Minimalist art. I never did, but I got real close…. I looked at it, I tasted it and I spat it out. I said, this is not for me. I’m a worker. I’m not somebody who’s happy to let my work be made for me and I’ll pass on it, yes or no, after it’s done. I could never do that.

For me, what is interesting is the nimbleness, stubbornness, determination and intelligence with which Puryear negotiated the aesthetic choices available to him in the late 1960s, a veritable minefield that stretched between the entrepreneurial and the confessional, formalist purity and identity politics.

Historically speaking, Puryear studied art in America and Sweden, lived in and traveled through Scandinavia, Europe and Africa, and worked in the Peace Corps in Sierra Leone during the convulsive 1960s. Culturally speaking, during this tumultuous decade of war, assassinations, desegregation and race riots, America witnessed the rise of Pop Art, Minimalism, Color Field Painting, Painterly Realism, Land Art and the Black Arts Movement, which was started by LeRoi Jones in Harlem in 1965, after Malcolm X was assassinated. The Black Arts Movement advanced the view that a Black poet’s primary task was to produce an emotional lyric testimony of a personal experience that can be regarded as representative of Black culture — the “I” speaking for the “we.” I doubt any of this escaped Puryear’s attention. Faced with these choices, his decisions were bold, adamant and, to my mind, inspiring.

According to Robert Storr, in his 1991 essay, “Martin Puryear: The Hand’s Proportion”:

Of major sculptors active today, Puryear is, in fact, exceptional in the extremes to which he goes to remove the personal narrative from the aura of his pieces. Nevertheless, he succeeds in charging them with an intense and palpable necessity born of his absolute authority over and assiduous involvement in their execution. The desire for anonymity is akin to that of the traditional craftsman whose private identity is subsumed in the realized identity of his creations rather than being consumed in the pyrotechnic drama of the artistic ego. As embodied in Puryear’s sculpture, however, this workmanlike reticence allied to an utter stylistic clarity is as puzzling and as evocative as a Zen koan.

Given the choices open to him between 1960 and ‘70, I don’t find Puryear’s “workmanlike reticence” puzzling, but exceptional. Recognizing that neither skill nor ideas were enough, he rejected becoming a formalist using outside sources to make shiny objects, refused to rely purely on his skill, recognized that craft was a storehouse of cultural memory, and chose not to become an “I” speaking for a “we.” Choosing the latter would have likely required that he evoke his ancestry while making art that alleviated liberal guilt. Influenced by Minimalism’s emphasis on primary structures, which were supposedly objective and non-referential, Puryear inflected his pared-down forms with the possibility of a shared or communal state as well as with a marginalized history that is both haunted and haunting.

In Puryear’s work, it is not an “I” using the form to speak, but a diverse and complex “we” speaking through the form. I think that in his devotion to craft (or his “workmanlike reticence”), which he always puts at the service of his forms, Puryear is attempting to draw upon this storehouse of cultural memory, in order to channel all the anonymous workers and history that preceded him. It is their eloquence, tenderness and pain that he wants to tap into because he understands that he cannot speak for them. The work functions as testimony and homage whose meanings (or narratives) don’t necessarily fit neatly together.

I cannot stress this enough. Puryear goes beyond simply remembering those who are invisible or marginalized, a “we” that is pushed to the sidelines; he also enlarges the definition of “we” through his work. As underscored by such titles as “Some Lines for Jim Beckwourth” (1978), “Ladder for Booker T. Washington” (1996) and “Phrygian Plot” (2012), this “we” isn’t defined by a single race, culture or history. (Jim Beckwourth, 1798-1866, who was bi-racial, was freed by his father and master and became a renowned explorer and fur trader; later in his life, he was the author of an as-told-to autobiography (written down by Thomas D. Bonner) about his life among different cultures and races: The Life and Adventures of James P. Beckwourth: Mountaineer, Scout and Pioneer, and Chief of the Crow Nation of Indians [New York: Harper and Brothers; London: Sampson, Low, Son & Co., 1856].) In this regard, Puryear has never been an essentialist in his materials, approach to art, or subject matter. By not following in anyone’s footsteps, aligning himself with a pre-established aesthetic, or branding his work, Puryear has gained for himself what all artists and poets are said to desire most: artistic freedom.

With “Cedar Lodge” (1977), which Puryear built shortly after his studio in the Williamsburg area of Brooklyn burned down on February 1, 1977, he completed the first of what might be defined as a sanctified space. At the same time, “Cedar Lodge” feels temporary. In fact, the artist dismantled and destroyed the piece after it was exhibited at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., perhaps because there was no place for him to store it.

In “Self” (1978), which Neal Benezra describes in his 1993 essay, “’The Thing Shines, Not the Maker’: The Sculpture of Martin Puryear” as “a dark monolithic form,” Puryear is able to convey the illusion of a solid, heavy form “planted firmly in the earth,” and therefore partially hidden. And yet, as one learns from looking at the sculpture, the self is not inherited, a byproduct of nature, but something that is made, created out of what is at hand. According to the artist:

It looks as though it might have been created by erosion, like a rock worn by sand and weather until the angles are all gone. Self is all curves except where it meets the floor at an abrupt angle. It’s meant to be a visual notion of the self, rather than any particular self–the self as a secret entity, as a secret hidden place.

In these early sculptures, Puryear began further defining a path that distinguished him from every movement as well as from his elders and peers; he was on his own path. Central to his decision is a belief in interiority; sacred spaces; a self-created private self; survival and temporariness. At the same time, knowledge of craft, which has cultural roots, and a study of history play a significant role in Puryear’s work. What is deemphasized in these works is the “I” or artistic ego.

Puryear’s philosophical position occupies the opposite end of the spectrum from the influential one taken by Andy Warhol: “If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.”

Or, for that matter, Frank Stella: “What you see is what you see.”

In works such as “Bower” (1980) and “Where the Heart Is (Sleeping Mews)” (1981), which was inspired by a Mongolian yurt, the artist alludes to the movable house, a temporary sanctuary that can be quickly transported from one place to another. At the same time, as Elizabeth Reede notes in a footnote to her essay, “Jogs and Switchbacks” (2007):

"Puns are not uncommon in Puryear’s titles. A mews is a hawk house, and the title Sleeping Mews is a pun on Constantin Brancusi’s Sleeping Muse (1910)."

In using puns, Puryear recognizes that neither language nor meaning is fixed or stable, that everything is contingent. Seemingly mobile, Puryear’s sculptures both critique and share something with Serra’s take on the relationship between viewer and object, which I cited earlier:

"The historical purpose of placing sculpture on a pedestal was to establish a separation between the sculpture and the viewer. I am interested in creating a behavioral space in which the viewer interacts with the sculpture in its context."

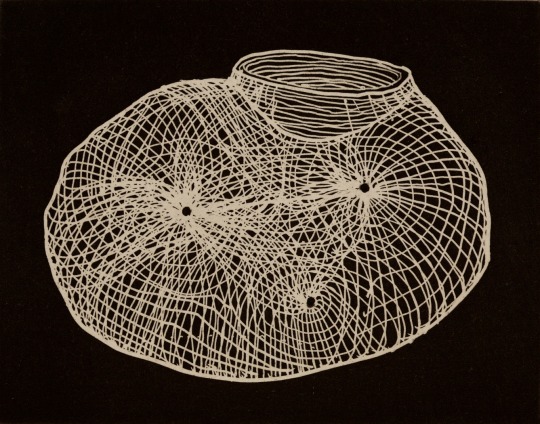

Rejecting the pedestal, Puryear places his works directly on the floor. Often composed of both an exterior form, such as a sensual, layered skin or a skeletal, enclosing structure, and an inaccessible but visible interior space, the sculptures invite the viewer’s interaction; they evoke a behavioral space in which a possible intimacy can occur. Whereas Serra’s space tends to privilege an authoritarian shepherding of the viewer through a carefully designed, architectonic structure, Puryear’s work seems to invite the viewer’s speculation as it creates a space of reflection. Made at the beginning of a decade dominated by the “death of the author,” the denigration of craft and skill, the promotion of entrepreneurship, and the elevation of appropriation, Puryear’s “Bower” and “Where the Heart Is (Sleeping Mews)” represented a direct challenge to mainstream art and thinking.