#what kind of religion is zoroastrianism

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Video

tumblr

Explore the ancient wisdom of Zoroastrianism in our latest video! Uncover the fascinating history, beliefs, and practices of this monotheistic faith that dates back thousands of years. From the teachings of the prophet Zoroaster to the significance of fire in their rituals, this video provides a comprehensive insight into one of the world's oldest religions. Join us on a journey to understand the core tenets of Zoroastrianism and the vibrant community of Zoroastrians. Discover the enduring impact of this ancient faith on the world's religious tapestry. Don't miss out on this enlightening exploration! #Zoroastrianism #Zoroastrians #MonotheisticFaith #ReligiousHistory #AncientWisdom #Zoroaster #FaithAndBeliefs #CulturalHeritage #ReligiousDiversity #HistoricalPerspectives #viral #trending #explore

#zoroastrianism#religion#zoroaster#zoroastrians#what is zoroastrianism#overview of zoroastrianism#Monotheist#zoroastrianism explained#What is Zoroastrianism#Zoroastrianism#Islam#what is zoroastrianism religion#what is the ancient religion zoroastrianism#what kind of religion is zoroastrianism#who is zoroaster#zoroastrianism history#ancient iran#hinduism explained#what is buddhism#what is hinduism#zoroastrianism in iran#Polytheism#viral#trending#Explore More

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A while ago I read The Flame Imperishable: Tolkien, St. Thomas, and the Metaphysics of Faerie, which was a very good read (though confusing and I probably missed a lot, as I have no background in philosophy). It’s focused largely on the Ainulindalë and how it relates to Christian (specifically Thomistic) theology on the nature of God, creation, angels, amd the problem of evil.

One of the things that’s odd to me, though, is that while it comares and contrasts Tolkien’s (implicit) philosophy with Aquinas’ and also with various schools of Greek philosophy, Zoroastrian-derived Manichaeism, etc., and makes a case that Tolkien’s metaphysics is overally more in line with Aquinas than the other ones, it seems to never mention Norse/Old English beliefs about creation and evil.

Amd I don���t think is is about a disregard for non-Christian philosophies from the author – like I said, it brings in Greek and Zoroastrian philosophies. And additionally, I’ve got a big textbook (never managed to finish reading it) that’s a summary of the various schools of Western Philosophy over time, and it mentions nothing abput these either – so I think The Flame Imperishable leaving them out is not about religion but about what is defined as philosophy by philosophers.

And sure, maybe the Norse and Old English weren’t calling themselves metaphysicians, but they still had a worldview and a cosmology, they still had thoughts and ideas about creation and evil. And if your book is asking “what were the principle inspirations for how Tolkien wrote about the nature of Eru and creation and angelic beings and the nature of evil in his legendarium,” it seems like inspirations deriving from the culture that Tolkien spent most of his life studying deserve at least a mention.

Just. There seems to be a bit of a divide between “the study of philosophy as a scholarly discipline” and “the study of different ways that humans have thought about fundamental aspects of the world over the years”, and that seems to leading to a pretty important omission here. I get that there are other books on that topic and you’re allowed to have other focuses, but some kind of mention of the scholarship around that seems warranted as context.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

There is no Salvation outside of Christ – all religions agree

One of the dogmas of Christianity is that there is no Salvation outside of Christ, which is a bold claim. However, it is a claim that is consistent with the teachings of all other major religions. After all, no other offers Salvation on the terms and in the form that it is defined in Christianity.

The text below will present the definition of Salvation and its significance in Christianity. After that, I will show how it relates to other, both ancient and contemporary, religions.

Whoever believes in Him shall not perish

What Christianity changed in original Judaism is the introduction of Grace and Salvation. In the Old Law, sins were defined, as well as sacrifices and other actions that needed to be performed for these sins to be forgiven. In this respect, Judaism was not much different from other religions like that of ancient Egypt or those based on the concept of karma.

Christianity is different because all sins can be immediately forgiven if you believe that Jesus Christ died for them and you truly repent (J 3:16-17, Lk 18:9-14). Therefore, if you die in an accident a moment after you decide to repent, you will not be condemned. In old Judaism, if you die before making a sacrifice for your sins, you have a problem.

This is what Grace and Salvation are about. Sins and transgressions are forgiven, despite no equivalent action being performed. This is compared to the forgiveness of an unpaid debt (Mt 18:23-27).

Aside from how Grace affects your fate in the afterlife, it also has a salvific impact on society. In the old system, you can reach a point of no return, after which it is physically impossible to perform all the necessary actions for the forgiveness of your sins. This means reaching a state of certain condemnation, or at least the conviction of it. In this situation, a sinner, having nothing left to lose and nothing that can improve their state, is devoid of reasons to try to improve at all. They are left only with further sinning, further doing evil, to at least enjoy life while they can.

In Christianity, you can always convert and you can always obtain Salvation. Therefore, everyone has a reason and a source of motivation to improve, no matter how badly they acted in the past. And this is what Grace and Salvation in Christianity are about.

It should also be added about a different pathology originating from the other side. If one believes in some kind of balancing of good and bad deeds, a person who has done good deeds may consider that they can afford to do something bad. Such pathology has already been mentioned in the Old Testament (Ez 18:24)

As a side note, Salvation concerns receiving Eternal Life. The state of Sainthood is a separate issue about which I wrote in my previous text.

Weighting hearts and other karmatic things

When it comes to other religions, among those concerned with morality, they have their own systems for reconciling sin/karma/deeds. The Egyptians believed that after death your heart is weighed to determine whether good or bad deeds prevail. If your bad deeds weighed more, your heart would be devoured by Ammit. Salvation does not apply; you must ensure that your good deeds outweigh the bad.

In Zoroastrianism, the virgin-born Saoshyant will lead humanity to the final battle against evil, prevail, and make everyone immortal. This sounds similar to Christianity, but in this religion, salvation depends on the sum of thoughts, words, and deeds, which no holy intervention can change. In short, there is no Salvation in the Christian sense.

Hindu beliefs are diverse, but most believe in karma and reincarnation. If you live a holy life, after death your soul will merge with Brahma, breaking your cycle of reincarnation. If not, you will be reborn according to your karma. If you have done well in life, you may be reborn as a wealthy person. If you have done poorly, you may be reborn as an animal. Salvation does not apply; you must cleanse your own karma. And you must also do this for your previous lives. Apparently, if you are not born wealthy, you have little chance of uniting with the god Brahma.

Buddhism is similar to Hindu beliefs. Reincarnation depends on accumulated karma, and breaking the cycle of reincarnation is the reward for good karma. But there is no union with any god because Buddhists do not believe anything is eternal. Breaking the cycle of reincarnation means the end of your soul's existence, freeing you from the suffering of rebirth. There is no Salvation or even any form of Eternal Life.

The Japanese variant of Buddhism has the mythical Sanzu River, which functions similarly to the weighing of hearts in Egyptian mythology. In Shinto religion, there is a greater emphasis on earthly life than on life after death. The souls of the deceased can live after life as kami and look after their living loved ones, as long as they perform the proper post-mortem rituals and remember them. Exceptional individuals, like members of the imperial family, can achieve divinity after death. Kami do not necessarily have to be good, and the spirit world is neither a counterpart of Heaven nor Hell. Additionally, people who died a violent death, or for other reasons were overwhelmed with negative emotions at the time of death and did not receive proper post-mortem rituals, can become obake – revenge-seeking ghosts. So, there is no Salvation; the dead can become tormented ghosts if the living do not care for them.

Taoism has various versions that have different views on what happens after your death. Some believe in reincarnation, others in achieving post-mortem immortality. Zhuangzi, one of the two most important texts in Taoism, considers death a natural part of our existence, just like life, birth, and the state before all life. Generally, in Taoism, you should live a simple life, do what you are given to do, and as a result, you may receive eternity after death and the opportunity to help the living achieve your state. Additionally, there is also the concept of Cheng-Fu, which is similar to karma. It differs, however, in that you can struggle not only with bad Cheng-Fu from your previous lives but also with bad Cheng-Fu inherited from your ancestors and your society. Salvation is not available; you must work out good Cheng-Fu yourself.

In the case of Confucianism, Confucius said little about life after death, considering it, along with spirits and gods, too great an unknown. His philosophy focused on living decently in life, concluding that without mastering this, there would be no decent life after life. So, Confucius did not recognize the concept of Salvation, mainly because he claimed he could not know what awaits us after death.

Cults of material accomplishments

Besides religions focused on morality, one can also mention more primitive religions that ultimately did not stand the test of time. Here, we are talking about religions that justified the power of kings or other types of leaders. Ancient Egyptian religion also falls into this category, as the Pharaoh ruled over you because he was holy, and you knew he was holy because he ruled over you.

In Greek mythology, which was the religion of the one percent elite, most people went to Hades, while only those favored by the gods could find themselves in the Elysian Fields after death. There was no salvation, only favoritism by the gods.

As for Norse mythology, Vikings were afraid to die in their own beds. To get to Valhalla, they had to die in battle. There was no salvation; you had to go to death.

To sum it up

The idea of Salvation and Grace was introduced by Christ and is a unique element of Christianity. In other religions, at best, a system of weighing good and bad deeds is applied. However, this system is flawed, as it can lead to pathologies born from the belief in achieving a state of irrevocable damnation. It can also lead to pathologies born from the belief in having accumulated enough good deeds to afford to do evil.

In Christianity, you can always convert if you believe that Christ died for your sins and you truly regret them. You also cannot exploit the system, as God is ready to restore the requirement to repay your forgotten debt (Mt 18:32-35).

If we reject the idea of the Primordial Chaos, present in many religions, according to which even the power of the gods is not eternal or everlasting, and instead accept the idea that all creation is the work of an omnipotent and all-good God, worthy of judging our deeds, Christian Salvation and Grace better reflect this idea than what is accepted about life after death in other religions.

Considering that other religions do not offer any similar form of Salvation, it becomes undeniable that there is no Salvation outside of Christ.

#christianity#philosophy#philosophy2002#God#Jesus#religion#salvation#afterlife#bible#faith#christian faith#faith in jesus#faith in god

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some fun tidbits about possible real-life inspirations/motifs for Almyran characters, on given names and class names

Claude

His Almyran name is Khalid; and while that's a pretty popular name with a meaning (undying/immortal) that fits with his character + his country's theme (Persian Immortals, amesha spentas in Zoroastrianism translating to "bounteous immortals," etc), one very famous figure from Middle Eastern history with that name was Khalid ibn al-Walid, a general in early Islamic expansion.

Khalid ibn al-Walid, and early Islam in general, is famous for starting out as underdogs from a region that was beset with constant internal feuds, before unifying and dunking on + conquering two more powerful nations (Byzantines and Sassanids) after they were tired out fighting each other in a long stalemate of a war... sounds kinda familiar huh.

Barbarossa is obv from Hayreddin Barbarossa, an Ottoman corsair (basically pirate) and later admiral who established Ottoman dominance in the Mediterranean and was a great military strategist.

Nader

Another popular name but, that name combined with the title "Undefeated" brings Nader Shah to mind. (Nader Shah gets called Napoleon of Persia, but considering the Napoleon did his stuff after Nader Shah, I think the chronologically accurate term would be that Napoleon was the Nader Shah of France lol)

Nader Shah was two things: a really great general and a really terrible ruler. He was very good at fighting and winning battles but he fucking sucked at actually ruling over the territories he conquered. His son, Reza Qoli, didn't like him and criticized him for being a bad ruler, so Nader Shah had Reza Qoli's eyeballs pulled out after suspecting him of being behind an assassination attempt. Anyway Nader Shah was later successfully assassinated after pissing off too many people and the Afsharid dynasty he founded fell apart straight in his grandson's generation.

Our Nader is a lot nicer as a person and sticks just to the general part lol. Also the only offspring he is explicitly mentioned to have is a daughter in Balthus-Claude paired ending.

Shahid

His name means witness in generic, but in wider Islamic usage (and in other religions that came into frequent contact with Islam) it also means martyr. Our Shahid is... not exactly the kind of upstanding guy that widely revered martyrs are, but from his perspective, his choice to die standing instead of surrendering was probably an act of martyrdom.

What's interesting though, is that his name in Japanese is シャハード; shahado, with ha as middle syllable, not hi. Shahad is also a name and a variant of Shahid, but there's also figure in Persian mythology with a similar name who has a similar character/position as our Shahid: Shaghad.

Shaghad was the half-brother of Rostam, and was jealous of Rostam for his renown, so he plotted to kill Rostam by dropping him into a pit of spears and poison. But before he died, Rostam shot Shaghad with an arrow from the pit and killed him, too. Our Shahid gets both the falling to his death and the noscope by his half-brother rip

His class, Gurgan, appears to be from Gorgan, a city in Iran by the Caspian Sea. The etymology of Gurgan/Gorgan itself comes from gorg, Persian for wolf. Pathetic wolfboy Shahid real??

Gorgan also had had the Great Wall of Gorgan nearby, to defend the Sassanid Empire from from northern nomadic invasions. Much to ponder, re: Fódlan-Almyra relations, the real-life inspirations of Almyra, Claude's goal, and what Shahid tried to do...

Just wild speculation on my part, but I also wonder if Gurgan was meant to be Gurkhan but they mixed up a letter along the way or something? It's a Mongolian title meaning "universal ruler," equivalent to khagan, equivalent to king of kings. Certainly fits Shahid's personality/ego and the cultural inspirations.

Cyril

It's Greek name meaning lordly/masterful, and a character from a place based roughly on the Middle East having this name is actually not out of place, considering the places along the Mediterranean have always interacted with and influenced one another.

Of course the in-universe lore is that Fódlan has been isolationist for the past 1000 years, but at the same time, Cyril is from a village close to the border, and it's noted in Hopes that western Almyra and eastern Fódlan share a language. Whether Cyril is a "Fódlani" name or an "Almyran" name in-universe, it still fits.

It's also a very Church-y name. There were lots of popes and patriarchs named Cyril, many being popes or patriarchs of Alexandria/Jerusalem/Constantinople. Our Cyril does have an ending (with Petra) where he becomes a priest, maybe that's a shoutout to this?

Among the Cyrils, maybe one of the most famous is Cyril the Philosopher, who is the namesake behind the Cyrilic alphabet and an evangelizer to Slavs alongside his brother Methodius. Again, interesting considering our Cyril starts out iliterate. (Methodius is also the namesake for Metodey but uhhh I don't think that means too much wrt our Cyril)

(Also I'm not saying all of the above + Leicester-Almyra relationship means that Leicester is the parallel of Balkans/Eastern Europe in the 3H world. But I'm saying Leicester is the parallel of Balkans/Eastern Europe in the 3H world.)

So yeah who knows how much of this was intentional but it certainly is fun to rotate in your head if you are a deranged person like me

#fe3h#fire emblem three houses#fe3h meta#meta#fe3h worldbuilding#claude von riegan#cyril fe3h#cyril fire emblem#nader fe3h#nader fire emblem#shahid#shahid fire emblem#shahid fe3h#nader#cyril#almyra#slotalks

28 notes

·

View notes

Note

i have a religon question. we all have indigenous gods, right? especially in 'the east.' do abrahamic religions see these gods as fake, or just another part of god, or djinn and demons? I know there are people who are jewish or muslim or christian living in places with a large population that follows the kind of religion that respects ancestors and hometown gods; do those people also get to pay respects to those deities? do they get a pass for that because they, too, are technically protected by those indigenous gods even though they technically converted, but they're still of that land?

(could that be applied to earth kingdom spirits, bc there's so many of them?)

Hi! You are going to get a MONSTER response here, and it might not even fully answer your question, so... apologies in advance.

I want to start with your premise about indigenous gods. I think there are two elements that strike me as needing some kind of definition or clarification.

The first is: what does "indigenous gods" mean?

Please keep in mind that I am going to discuss indigenous RELIGION here, not "indigenous" as a political term.

I think there is a faulty assumption often applied to conversations around indigenous vs global religions that assumes that "indigenous religion" is polytheistic and "global religion" is monotheistic. One issue with that, in my opinion, is that "polytheistic" and "monotheistic" just aren't as meaningful as Western academia has historically stated. They are, in my opinion (though not only my opinion!), terms laden with Protestant ideology.

Protestantism and "Polytheism vs Monotheism":

Protestant religious scholarship tends to want to divide religion into the more primal, physical religious expression vs the more otherworldly, spiritual expression. Polytheism is, in Protestant academic mindset - excuse my language here, I'm making a point - a kind of barbaric, pre-enlightened, base form of religious expression. When religion gets more refined and intelligent and articulate, it sheds those earthly elements and ends up being monotheistic. This is Protestant in origin, specifically, because it is not only about how Protestant academics viewed religions like Hinduism or European indigenous religion, it's also about how they felt about Catholics and Jews. Catholics and Jews, from that mindset, might be "monotheistic", but they're holding onto the base, unrefined physicality of the old world. Catholics and Jews like physical rituals, physical prayer, rules around eating, etc. So yes, sure, they're monotheistic, but they haven't quite understood monotheism yet.

This is obviously not a nice thing to think about other peoples, but that's not what is interesting for our purposes. What's interesting is that Protestant academia has left much of the West with the above as their understanding of how religion functions. Even many atheists, by the way, will describe atheism as just the next step on that wrung; religion starts with polytheism, which is steeped in physical ritual and is obsessed with the earth, etc, then people became monotheistic and slowly let go of those earthly things, and then people got truly enlightened and realised there's no God at all. You can hear this in how some atheists will talk about believing in "one fewer god" than monotheists - that sense of the arc of progress and development.

Now, I hope you've already realised that I don't believe that's true. But let's break it down a little:

What is monotheism, and what is polytheism?

Judaism often has ascribed to it being the first monotheists. In some ways, that's true; in some ways, it isn't. There were One-God-isms that occurred elsewhere, too. Famously, in Egypt, the pharaoh Akhenaten led a religious reformation which narrowed worship down to Aten, the sun god. Nobody can agree on exactly what this was, but it was at least a focused religious expression. Likewise, Zoroastrianism was talking about a dual nature of reality in a way that could be read as monotheistic before the Jews were.

And when the Jews began to worship God as One, it wasn't exactly a clean break. It's actually fairly clear that the worship of the one we now just call God was really a slow development of theological focus, which we might now call henotheism: belief that multiple gods exist, but only worshipping one. Then that God slowly came to represent a kind of universality, especially with the experience of worshipping a land-based deity while in exile (first exile, starting c.586BCE).

So the Jewish belief in One God is a bit like Atenism: a focusing in on a particular god. Except this time, instead of one big religious revolution, it was a very slow religious development.

And if we want to divide not only into "monotheist" and "polytheist", but also into "indigenous" and "global", we're in very murky waters.

Indigenous Religion and Global Religion

Noting again that this can get politically tense because classifications of indigeneity are politically fraught. I'm interested in what makes a religion or culture indigenous, not in what that means for us politically.

Indigenous religion is difficult to define in a sentence, and so I will not try to do that. Here are multiple things that come together in indigenous religion in general instead: Indigenous religiosity is not distinguishable from culture itself. It's born of a land and developed over time. It might have its own myths about its origin (it likely will!), but those are often contradictory in some ways, because they are descriptions of important cultural narratives rather than histories. It tends to be uncentralised and is often slightly different depending on where you are in the land. It tends toward agricultural spirituality and concepts of holy soil. It is tied to an ethnic group and is generally uninterested in ideas of conversion (either into the group or out of the group); it may even be hostile to outsiders joining.

Global religions, on the other hand, tend to be much more planned-out. A global religion is born from a person or a group of people. One can see its birthplace and origin. It is devised in order to spread, and therefore is not attached to one land or to one ethnic group (so that it can move both geographically and through conversion of others into the group). It tends toward centralisation in an organisational capacity.

So. Is Atenism indigenous? ... Well, kind of yes, kind of no. Worship of Aten is born from the land of Egypt, but having a specific historical revolution makes it seem a little outside the "indigenous" definition. But it's definitely not global either. So we've immediately located something that doesn't seem to work well in a binary sense.

Is Judaism indigenous? ... Pretty clearly "yes". It's a land-based agricultural religion born of a particular land, with strong ethnic ties, that developed over time (rather than being born of a historical moment), that isn't interested in spreading or converting and wants to be in its holy land, is uncentralised and disorganised in nature, etc. But people don't tend to talk about Judaism that way, because Judaism has survived a 2,000-year exile, which is pretty unheard of. Once you've been kicked out of the land that long, it feels like it should be a global religion. But it doesn't fit any of the critera for that.

I think that Judaism being an indigenous religion that learned to survive outside the land is part of the reason that people have such a hard time understanding what Judaism is. It seems, from the outside, like it should function more similarly to Christianity and Islam. But in most ways, it just doesn't.

(Also, it would be remiss of me not to note: there's also a lot of political discomfort around calling Judaism an indigenous religion, because most indigenous cultures haven't reclaimed sacred land after being colonised, and the Modern State of Israel a) exists and b) is acting as an oppressive force. Some people will define groups as indigenous specifically only if they are currently being oppressed within their land of origin. As an academic, I think that's a poor definition, and it's certainly not helpful for defining indigenous religion. But I understand the political discomfort.)

Hinduism is also a really interesting example of this. Hinduism is similar to Judaism in some ways, as it's an indigenous, land-based religion that learned to exist outside of the sacred land. It often gets miscategorised on the basis that it's spread geographically (and unlike Judaism, that spread was not simply by outside force). In some ways, Hinduism acts like a global religion, but it doesn't really fit the bill.

Therefore:

a) "Indigenous religion" isn't always polytheistic (if that's even a meaningful term)

b) Some religions fit into neither category (such as Atenism)

c) Some religions fit into one category but aren't categorised that way by outsiders for various reasons (such as Judaism)

And to add another point: Buddhism is a great example of a global religion. Born of a historical person and moment, ease to spread and convert, not tied intrinsically to land. But try defining Buddhism according to the Protestant theistic categories. I dare you. So:

d) Global religions aren't always monotheistic

"Monotheism" and Global Religions

With that in mind, let's talk about Christianity and Islam. They are the major religions of the world. Christians make up around 30% of the world, and Muslims make up around 25% of the world. And frankly, the 15% of the world who call themselves secular/atheist/etc... I think meaningfully belong to Christianity and Islam, too. I know people often don't like that, but the idea that you have to believe something to belong to a religion is a specific religious idea that I don't ascribe to.

A lot of the time, the way that religion is conceptualised is therefore through a Christian or Muslim lens. (See: my point just above about "faith" in religion.) This has completely muddied the waters of how we discuss and conceptualise our own religions and cultures, let alone other peoples.

Your original question was about Abrahamic religion, so I'm going to try to address that here, but please keep in mind: in a question about indigenous gods, putting Judaism in the same realm as Christianity and Islam is dodgy territory and we need to walk it carefully.

"we all have indigenous gods, right? especially in 'the east.' do abrahamic religions see these gods as fake, or just another part of god, or djinn and demons?"

Judaism: Judaism is an evolution that occurred within Canaanite religion. It started with narrow worship of a local god and slowly universalised, especially when the Israelites were trying to survive outside the place of the local god. The seeds of that universalisation already existed before the first exile, which is likely why it worked. It had a confused relationship with the other local gods; outright worship of those "other gods" was frowned upon but still existed among the peoples, and that worship kind of melded into the narrow worship of the One God. You can see this in how many of the names of God that appear in the Bible are actually the names of the local Canaanite gods.

After the first exile, Judaism became more solid in its sense of theological universalism. Jonah is a great example of this as a book; Jonah was written post-exile (though set pre-exile), and it starts with an Israelite trying to run away from God. It seems absurd to us now, because we know that the Jewish God is universal, but the character of Jonah seems to honestly think he can escape God by leaving the land. The rest of the book is about Jonah's struggle to understand how his god also has a relationship with the people of Nineveh. It's a great example of the struggle of universalising theology.

(By-the-by, I think "universal theology" is a much more useful term than "monotheism", but that's a rant for another day.)

What began as a narrowing ("henotheism"), which was both pushing out and incorporating other local traditions, then had to contend with the worship of the oppressive forces of outside religion. Assyrians, Babylonians, Greeks, and Romans are all peoples who attacked, colonised, exiled, etc - and they all came in with their gods. The Greeks even instituted worship of their gods in our Temple. Our worship was made illegal by the colonisers. Relationship with "idol worship" was about relationship with those outside forces.

In short, the literature itself is very confused about what those gods actually are. Jews were certainly not supposed to worship them, and should go to great lengths to avoid them. (If we didn't, we probably wouldn't still exist, so: good shout.) Sometimes they get talked about like neighbouring gods, which is a holdover from the narrowing-days (where those other gods existed, but we worshipped our own native land-based god). Sometimes they get talked about as false idols created by people who are either misunderstanding reality or deliberately trying to have control over the divine (which developed more as the God-worship was universalised). The more universalised our theology became, the more we started shrugging of ideas of neighbouring gods that actually existed, and the more it became about the latter.

(Note: When Jews met religions that call a universal God something else, they would then tend to conclude that it's not idol worship. This developed when Judaism met Islam in more peaceful moments. The idea that non-Jewish religions could be something other than idolatry then came to include Christianity - but only kind of, because of the worshipping-a-person issue - and then religions like Sikhism much more easily. It's even arguable that religions like Hinduism aren't exactly "idol worship" for non-Jews, because many Hindus will describe what they believe in in universal terms - Brahman is first cause and all emanates from him - even if their worship includes references to "multiple gods". This does not mean Jews are allowed to worship that way.)

Christianity: Christianity was born in a specific historical moment, utilising previous Jewish and Hellenistic thought. It almost immediately became a religion of conversion (I would put that distinction at the year 50, with the Council of Jerusalem). Since it was born from a universalised theology, it already had the bones of the idea of a universal God; now, it also had the will to spread, both geographically (shrugging off major religious ties to the Holy Land) and religiously (not only could people convert, but people should convert). While Judaism was all about avoiding worship of other gods, Christianity became about converting those peoples.

Islam: Islam was born in a specific historical moment, utilising previous Christian, Jewish, Zoroastrian, and pre-Islamic Arabian thought. It immediately became a religion of conversion. In this sense, it's a lot more like Christianity than anything else, except Christianity developed most significantly after the death of Jesus. Islam got a lot more time in development with Mohammed. In some ways, I think this really benefitted Islam (though that's not to say some things didn't get... complicated, upon his death). It inherited from Christianity the sense that worship of other gods was something to be responded to with conversion.

"I know there are people who are jewish or muslim or christian living in places with a large population that follows the kind of religion that respects ancestors and hometown gods; do those people also get to pay respects to those deities? do they get a pass for that because they, too, are technically protected by those indigenous gods even though they technically converted, but they're still of that land?"

Short answer: no. Jews, Christians, and Muslims do not believe that those deities exist as separate to the universal God.

Longer answer for Judaism, because... well, I know more about lived Judaism than lived Christianity or Islam*:

(I recently said to someone IRL: I do have a degree in Catholic Theology, but I don't know anything about what Catholics ACTUALLY believe.)

It would be absolutely disallowed in Judaism to participate in worship of "other gods". Modern Jews will not believe those gods exist (at least, I've never come across that either IRL or in studies). However, Judaism does still hold that worship is a powerful thing and that Jews are not allowed to participate in worship of "other gods". Many Jews will say it's not worship of "other gods", it's just worship of the one universal God that is understood differently by different cultures. This does not change the fact that Jews are not allowed to participate in it.

(In fact, it's one of the three things a Jew should rather die than participate in. It's a little murkier than this, but basically: even under duress, even on pain of death, a Jew should never murder, commit sexual violence, or worship an idol.)

"(could that be applied to earth kingdom spirits, bc there's so many of them?)"

Yes, I think the Earth Kingdom in ATLA is supposed to function in an indigenous manner, specifically in indigenous religion as it acts over a wide spread of land. That is to say, like Hinduism, or like when you compare different arctic indigenous cultures or African indigenous cultures. There isn't a centralised force (like with the FN); it's local gods - or here, spirits - that have their own myths, etc.

Please note, I have avoided talking about nomadic cultures here on purpose, because this would be twice as long! This is not exhaustive at all. I hope it makes at least some sense.

#jew on main#judaism#christianity#islam#buddhism#hinduism#it's a world religion extravaganza#canaanites#not the kindest post to protestants#atenism

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

id love to read something about the role of "magic" in indian or sinosphere culture. i feel like the notion of "magic" as distinct from licit religion is very old and pretty prominent in like...circum-meditterean greco-semitic (semitic in the language group sense) culture, but doesnt seem to be as much of a thing in the hindu-buddhist tradition? you might argue it was a particular sort of reaction to the notion of the other. my feeling is that the C-M G-S (see previous phrase) culture is veyr fixated on the other, like obviously every culture cares a lot about the other but in particular in the west you see a lot of like...very passionate attempts to cleanly divide yourself from the other. obv jewish and then christian tradition is strongly opposed to syncretism (on an official level, ofc it happens) and the greeks were OBSEESED with the other, the persian, the barbarian. maybe this is just because we have so much writing from them? maybe every culture is super fixated on the other? but it doesnt SEEM that way, from what ive read (i guess japan is pretty fixated but if youre an island nation, "islanders" and "nonislanders" is kind of a real and coherent distinction)

anyway. maybe theres some perfect sanskrit translation for "mageia" but i wouldnt expect so (unless they also have a cognate derogatory term for zoroastrian priests lol)

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

JUSt needed to tell you that thinking about "Profile in Quicksilver" got me through the day 💕💕💕

I also love how you incorporate worldbuilding details seamlessly into the narrative without being overwhelming! I love reading Gale & Draxum talking! Do u have any religion/traditions/custom headcanons that didn't show up in the fic (yet)?

thank you so much for writing!!!

Thank you! I do try to avoid lore dumps, even if they can be interesting at times. Ideally, people won't realize they're being lore dumped on. It's like, in a dance when you transition to a different blocking, ideally the audience shouldn't even notice you're transitioning, it should just feel like part of the choreography.

And OH FUCKING BOY DO I. Thinking about the background of the Hidden City and the Yokai as a whole has been so much fun. Making it fit with the lore we see in the show and the actual history of New York City has been so much fun-like, it's not that there happens to be a giant monster city under NYC, NYC became NYC because there was a giant monster city already there. And that's why NYC is Like That. Why are all the dark armor pieces in New York? Because that's where most magic is now, magical beings were driven out from everywhere else.

As far as religion, I've been keeping them pretty secular? Mostly because that's just an aspect I don't feel really jives with TMNT. I have a scene later on where Leo and Mikey attend church with April and her parents, but it's more out of curiosity than any real desire to take up religion. They see it as more of a cool cultural thing that an actual system of beliefs. One of the main things I can remember right now is Leo bitching about the smell of incense.

In the background, I think of the Yokai as following a lot of pagan religions. These people haven't been directly colonized or conquered (or more accurately, were ethnically cleansed instead of being colonized or conquered) so Christianity and Islam are much less common. Probably the same with some other religions that spread due to conquest, but I'm not...entirely sure what those religions would be. (Hellenism? Zoroastrianism? Taoism? Do those fit? I'm singling out Abrahamic religions because those are the most common currently) Also Christianity and Islam are pretty young religions. I haven't made a definite timeline, but I'm leaning towards most Yokai communities being established more than 2000 years ago. Leo mentioned in the Christmas chapter that there were a lot of bright reds and lights down in the Hidden City-pretty much everyone has a winter solstice holiday, so officially they're celebrating the solstice instead of any one religious holiday, and everyone's kind of free to celebrate however they want. Not a lot goes down in December, actually. Schools have most of the month off, a lot of workplaces cut their hours or just straight shut up for a few weeks, most people are partying and spending time with family. It's basically like their summer vacation.

Oh! One thing I will probably work in at some point, but the last of the Yokai migrations happened during WW1. The few remaining exclaves in the human world (like the one in Chongqing, where Tigerclaw was living) basically went "fuck it" and packed up shop, even in places where there was no fighting. It was the nail that drove home that they couldn't exist alongside humans, that even if they weren't warring with the humans themselves they would still get roped into human conflicts, and eventually they would be killed off.

And the thing is, up until recently, the Hidden City was still rather closed off from the human world, despite living underneath NYC. You have to get government approval to go topside, so most people were living their entire lives underground without ever stepping foot in NYC proper. It was really with the invention of television and then the internet that bridged the gap from the Yokai's side, and both those things took a lot longer for the Yokai to adopt. So a lot of human stuff that happened from the 1910s to around 1970s-1980s era didn't get a lot of attention down there.

Like. They know WWII happened. Objectively. By that I mean they knew shit was going down, so the Heads pulled down just about everyone who worked up top and they all just bunkered down for several years until they realized the war was over. It was an annoyance for most of them, a period of time where they couldn't get certain products or had their business disrupted because somewhere in their chain was a guy who worked at a human company and he can't do that now. They were able to read about what happened afterwards and knew vaguely of all the genocides, but most of them didn't look into it very hard. Just more humans bent on killing each other, what else was new? Most of them will still refer to WW1 as 'The Great War.'

And I thought of this scene before October, and I feel like I probably shouldn't use it now due to how politically charged it is, but originally I wanted to include a scene where someone mentions Israel and Josh is really confused because the last time he was living aboveground that area was controlled by the Ottomans and was officially part of Syria. Maybe independent Jerusalem, but why would it be Israel? Bella has to pull him aside and explain. He knew about the Holocaust, but he had no knowledge of Mandatory Palestine or the Nakba. The entire time she's talking and his eyes are just bugging out.

On the plus side, India is no longer under British rule, so he was probably pretty happy to find that out?

I had like several other things I rambled about and deleted because they were going entirely off the rails, I might post those at another time. I've thought about this world way too much and I've written far too little down. (also sorry it took so long to respond! I knew I'd go crazy and wanted to get the chapter done first, and the chapter took longer than I expected lol)

#doth asks#i both love and hate info-dumping worldbuilding stuff like i feel like i'm just total stream of consciousness sometimes

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Many times in our work of meditation, of the path of the sacred arcana, we must face many battles against negative forces. Anyone who initiates their spirituality must confront their own mind, but also those entities or beings who constitute what we call the black lodge. They also confront us many times in our efforts, primarily because this kind of work is contrary to their interests, their concerns.

There is always this battle and struggle within religion between Ahura Mazda and Ahriman amongst the Zoroastrians, or Christ and the devil, good and evil, positive negative, light versus darkness. When these forces meet, they form twilight within the initiate, because the person who battles themselves must also confront all the entities of the black lodge, all the demons of that path who wants to pull the student into the internal dimensions, the infernal planes.

This is a very dangerous arcanum, specifically since it is uncertain what the outcome will be. But we know from tradition that all the great heroes who fight very diligently against themselves like Perseus, Theseus against the Minotaur, Aeneas, and many masters of meditation. They are successful, like we witness in the Opera Turandot with Prince Calaf, who faced the twilight of his own mind when he was confronted by all the people of Peking in Act 3, who wanted to steal his light, take from him his powers.

So this arcanum is about the battle between the soul and the ego, both within and without. As we stated there are two lodges: the white and the black, the angels and the devils. In this teaching, we have to define ourselves very specifically, because the outcome of this doctrine, according to Samael Aun Weor, is either an angel or a demon. There is no middle ground. We have to really define who we are and work for what we want.

#tarotreading#tarotcards#tarot course#tarot readings#free tarot#daily tarot#tarot deck#tarot reading#tarot cards#tarot#tarotblr#tarot witch#tarotcommunity#gnosis#chicago gnosis#chicago gnosis podcast#gnostic tradition#gnostic teachings#gnostic#gnostics#gnosticism#samael aun weor#samaelaunweor#samael#spirituality#spiritual#awakening#meditation#consciousness#esoteric knowledge

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

loose theory about temple of silence

im just basically grasping straws but its hoyoverse's fault for not offering lore crumbs 🗿

warning: mention of corpses

Cyno has a strong connection with death because of the Anubis inspiration from egyptian mythology, and we know the spirit is named after the syncretism (the practice of combining different beliefs) with greek god Hermes.

on that note, his name's possible etymology is also from greek, meaning dog.

coincidentally, dogs in zoroastrianism (ancient persian religion that a lot of sumeru's lore is based on) are associated with death in a positive sense as well. they guard the bridge where souls are judged before entering the afterlife.

Chinwad Bridge to Heaven is said to be guarded by dogs in Zoroastrian scripture, and dogs are traditionally fed in commemoration of the dead. Ihtiram-i sag, "respect for the dog", is a common injunction among Iranian Zoroastrian villagers.

in addition, dogs are considered to possess spiritual virtues in detecting and driving off daevas (demons), including that of the corpse matter demon Nasu.

in zoroastrianism belief, when a person dies their body is immediately possessed by this demon upon losing consciousness, and their corpse is therefore contaminated. if a living person comes into contact with it, they will also spend their entire lives spiritually contaminated (which is what dogs are used for in detecting and purifying it from the person).

for this reason, their funerary rites are conducted by two specific people instructed on the job, nobody else is allowed to touch the corpse.

zoroastrians believe the elements are sacred creations of their god, so burying, burning or throwing the contaminated corpses into rivers is prohibited. they instead have these two designated people transport the bodies to the top of a tower where scavenger animals will consume them over time. afterwards, the bones are hidden in the bottom.

They shall lay [the corpse] down on earth, over which the corpse-devouring dog or the corpse-devouring bird may certainly know him.

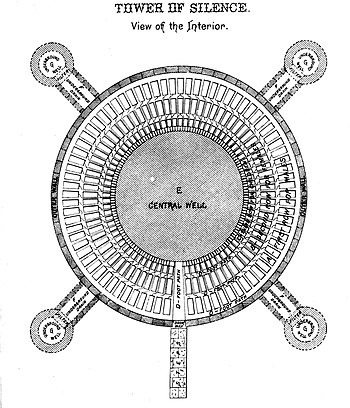

the name of this construction is Tower of Silence

the only information available about the Temple of Silence at the moment (besides the fact Cyno is affiliated to it and the staff knows Alhaitham) is this note found in the desert:

"by order of the Temple of Silence, all machines from Khaenri'ah shall be sealed in accordance with the Revelatory Monument's format"

using the zoroastrian tower as a parallel, and considering the contents of this note, maybe the khaenri'ah machines are under Temple of Silence's jurisdiction the same way the Tower of Silence stores corpses?

now on the realm of making shit up:

the term "Revelatory Monument" in chinese (说法处) and korean (설법처) seem related to buddhism, sort of like a place where the buddha imparted his teachings.

"temple" gives the organization a religious connotation, which is why the buddhism term might have been borrowed in the original text, so translating it as "revelatory" could have been done with the same intention (like bible revelations, the final book of the new testament). perhaps it means some kind of specific teachings or ?? a department with authority within the temple.

we know khaenri'ahns first used azosite (pure elemental energy) to power their machines, but then turned to abyssal energy which could explain why a specialized organization like the Temple of Silence would have to keep them under watch and seal their power.

if that's so, then maybe the so called Revelatory Monument "format" could be something like what Cyno used in the comic to seal the god in Collei's body.

and i mean since it's spoken words maybe alhaitham as a haravatat scholar has been involved in it idk maybe that's deshret script who knows

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

Been reading about a book regarding Zoroastrian religion and the part where it talks about the history of false idols according to the religion kind of explain why Ahriman has fiction rending power.

According to the book, all early idols are created originally to represent Ahura mazda's good creation, but overtime, human imagination (the evil thought / Angra mainyu) corrupts the meaning and gives the symbols new identities, born from fragile imagination and deified them into false gods. Thus bringing fiction into reality.

Hmmmm Does this give a clue what Ahriman rule is

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why do I prefer to say Secularism rather than Laicism?

The word Laicism comes from the French word "Laïcité" and means "Laicism" or "Secularism" in French.

The word secularism comes from English.

“Laicism” and “Secularism” are synonyms for each other.

So why do I say "secularism" and not "laicism"? Let me explain, because the laicism in Turkey has been implemented incorrectly;

1. "Religion does not interfere with the state, but the state interferes with religion." Example; On March 3, 1924, the Presidency of Religious Affairs was established and religion came completely under State control. Only works about the Maturidi school of the Hanafi branch of the Sunni sect are written to the public. This is completely against Secularism because in Secularism "Religion does not interfere with politics and politics does not interfere with religion." There is a principle. However, this was applied incorrectly in Turkey.

2. "The Sunni-Hanafi-Maturidi sect of the Islamic religion is the most correct sect and the others are perversion." This is also a wrong understanding because in the Holy Quran, no sect has any superiority over another sect, nor does any religion have superiority over another religion. In the Quran, there is only one source of the Islamic religion and that is Islam itself. "Those who split their religion into pieces and become groups, you have nothing to do with them. Their matter is up to Allah, then He (Allah) will inform them of what they did." Surah An'am Verse 159

3. "All religious texts and worship must be in Turkish." Writing the Turkish translations of a valuable book like the Holy Quran is a great service, but it is not wise to deny a rich language like Kurdish. If there is Turkish, there should be also Kurdish.

4. "All the people living in the Republic of Türkiye are Hanafi." It's definitely a wrong concept. 50% of the Republic of Türkiye is Hanafi and 50% is Shafi'i. Most of those who belong to the Hanafi sect are Turks, and most of those who belong to the Shafi'i sect are Kurds. "All the people living in the Republic of Türkiye are Muslims." No, 75% Muslim, 0.4% Christian and %? There are Jews, Zoroastrians, Atheists, Deists, Yazidis and other people.

5. "People who belong to the Islamic religion have the right to establish associations. (1950) No religion has the right to establish associations and institutions in any way. (1924)" Yes, people who belong to the Islamic religion have the right to establish associations and foundations after 1950, but people who belong to another religion does not have the right to establish associations and foundations. A member of the public does not have the right to do this. What kind of secularism is this! In American-style Secularism, "persons of any religion have the right to establish associations and foundations." For example; There are Muslim foundations, Christian foundations, Jewish foundations, Atheist foundations, Buddhist foundations and Hindu foundations in the USA. In other words, every religion has associations and foundations in the USA. This is freedom of belief.

6. "Alawite cemevis cannot become temples." This is against secularism, regardless of faith or religion. The place where each individual fulfills his worship and religious duties is called a temple. For example; If a Muslim has a Mosque, a Christian has a Church, a Jew has a Synagogue, a Zoroastrian has a Fireplace, or every religion has a temple. In other words, no matter who prays in which temple, it doesn't matter to us! "1. Say: "O unbelievers!" 2. "I will not serve what you serve." 3. "And you will not serve what I serve." 4. "I will not serve what you serve." 5. " You will not serve what I serve." 6. "Your religion is for you, and my religion is for me." Surah al-Kafirun is an example of this!

7. "When it comes to Muslims, there is freedom, when it comes to Alevis, there is oppression." The more free the Muslim, the more free the Alevi should be.

8. "It is mandatory for all citizens to attend compulsory religion classes." No. Why. A Christian, a Jew, an Alevi, a Zoroastrian, a Yazidi or a person belonging to any other religion does not want this. "La ikrahe fid din." do not forget it!

9. "Islamic religious holidays are celebrated, but religious holidays of other religions are not celebrated." Example; Muslims celebrate Eid al-Fitr, Eid al-Adha and other holidays, but when Christians and people of other religions want to celebrate their own holidays, the state intervenes.

10. This is why I use the word Secularism and not the word Laicism.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Or ancient Persian funereal rites. I’d love to know either or

Okay, so Today You Learned about the Zoroastrian custom for dealing with bodies. I remember thinking about this, because there's a scene in one of the expansions for Assassin's Creed: Odyssey, where Artabanus (a Persian character) plans to bury a defeated enemy who was once his friend before turning evil, and I was like, "Wait, that's not right."

So, for starters, Persia, or Iran, before it was majority Muslim was a Zoroastrian country. The religion still exists today, though there are much fewer adherents. Zoroastrianism is an ancient monotheistic religion that follows the teachings of Zoroaster/Zarathustra. Quite a few people try to claim that Judaism or Christianity is actually some kind of stealth rip-off, which I think is bunk, though I do think it's quite possible that it influenced Judaism, especially in the Babylonian Exile.

The term 'magi' is from the Greek's word for the Zoroastrian priests. National Catholic Register actually had an article about one of their journalists going to a Zoroastrian place of worship in London around the time of Epiphany (as the Three Wise Men are often considered to have been Persian magi, though it's unclear if they actually were).

Anyhow! Traditionally, the dead weren't buried right away; it was believed that a dead person would contaminate what they touched, as corpses were unclean. Fire, water, and earth were in some ways sacred, so they couldn't be used. Instead, the dead were placed on what was called the Tower of Silence, away from settlements, to be exposed (before that, it's indicated that it was exposed by other methods). That way the body would be exposed to the elements, and to carrion animals, who would help break it down/clean it up. What was left, mostly bones, was then prepared (in wax, I think?) and then buried.

There's a reference to this in a Sandman comic? In the story about the Necropolis in World's End, they mention the different methods of funeral rites, including letting the body be fed upon by birds in a high place.

This practice wasn't entirely universal, though--there are tombs of Persian emperors, and Zoroaster himself may have been buried.

It's very different than the funeral practices we generally think of, and while I can't say we should do it, I am a bit surprised I don't see this kind of thing appear more in fantasy or science-fiction. Burying or cremating bodies aren't the only customs that exist, after all.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Refutation of an anti-Zoroastrian Evangelical

A few years ago I was browsing Twitter when I stumbled upon a thread written by a pseudo-intellectual evangelical Christian apologist from Texas by the name of Sir Travis Jackson. In this thread, the evangelical was attacking Zoroastrianism, my ancestral Iranian religion.

As an advocate and defender of the ancient Zoroastrian faith, I didn't hesitate to get into a theological debate with him.

During the debate, I so thoroughly wrecked him, that he deleted the thread and retreated from Twitter to Tumblr so he could continue the debate without me.

He was seething so hard that he had to go on to Tumblr and write a 3,000 word barely coherent polemical rant to refute the Zoroastrian influence on Judaism and Christianity, where he mentions me by name in the first few paragraphs. I didn't even know about it until today. You can read it here: https://www.tumblr.com/sirtravisjacksonoftexas/627024203052433408/did-judaism-and-christianity-borrow-from

In order for this spasticated brainwashed evangelical to cope with the insecurity that he was feeling towards his beliefs, he had to jump through some very impressive mental gymnastics to refute my views. He should get a gold medal for that.

I have lived in Oklahoma my whole life so I have dealt with my fair share of Iranophobic anti-Zoroastrian evangelicals like him in the past. The evangelical christians are well-known for their bigotry, ignorance, judgemental intolerance, hostility, political extremism, incoherency, hypocrisy, and insular close-mindedness towards people of other faiths and ways of life. I have experienced it time and time again. It is a reputation they have thoroughly earned.

The Zoroastrian community, on the other hand, has earned a reputation of being honest, egalitarian, philanthropic, kind, joyous, charitable, industrious, entreprenuerial, and resilient in the face of adversity. The Zoroastrians have maintained their faith and tradition for thousands of years, surviving countless invasions and genocides from various bloodthirsty armies, and have made contributions to the fields of philosophy, science, literature, art, architecture, and jurisprudence. The ancient Zoroastrians literally invented Human Rights under King Cyrus. They are also well known for their rich cultural traditions such as Nowruz and their interfaith cooperation and positive relations with other religious communities. They also gave the world Freddy Mercury.

If you don't believe me, just ask the Hindus what they think of us. They love us. And we love them.

Anyways, here is my refutation to Sir Travis Jackson's refutation:

The argument presented in Travis Jackson's article against the fact that Judaism and Christianity borrowed from Zoroastrianism is weak and lacks evidence. The article argues that the Wise Men or Magi who visited Jesus were astrologers and not Zoroastrian priests. However, the term "Magi" was used specifically to describe Zoroastrian priests, and there is evidence that they were known to travel beyond Persia to conduct religious ceremonies.

Sir Travis Jackson argues that the Syrian Infancy Gospel is too late to be used as evidence that Zoroaster predicted Christ's birth. However, the fact that the text was written in the 6th century AD does not necessarily mean that it did not draw on earlier traditions. Moreover, the author ignores the fact that there are other sources that suggest a connection between Zoroastrianism and Christianity, such as the Acts of Thomas and the Clementine Recognitions.

Travis argues that the Jews did not borrow the concepts of heaven and hell, angels and demons, the devil, and the final resurrection from Zoroastrianism because these concepts were already present in pre-Zoroastrian Iranian religion. However, this argument overlooks the fact that Zoroastrianism played a key role in shaping the development of these concepts in Judaism and Christianity. For example, the Jewish concept of Satan was influenced by the Zoroastrian figure of Angra Mainyu, and the idea of a final judgment and resurrection was taken from the Zoroastrian concept known as Fareshokereti.

While it is true that many cultures and religions had the idea of an afterlife, including a realm of demons or evil spirits, the concept of Heaven and Hell as a binary choice for souls after death is unique to Zoroastrianism. This is not just a general idea of an afterlife, but a specific concept that has similarities to the Christian and Jewish belief in an eternal reward or punishment. Additionally, there is evidence that Jewish and Christian ideas of Heaven and Hell developed after contact with Zoroastrianism, particularly during the Babylonian exile of the Jews in the 6th century BCE, where they would have been exposed to Zoroastrianism.

While it is true that other cultures had similar concepts of lesser spirits or gods, the idea of angels and demons as specific categories with distinct roles is again unique to Zoroastrianism. In Zoroastrianism, there are good and evil spirits that are in constant conflict, which is similar to the Christian and Jewish ideas of angels and demons. While there may be similarities to other cultures, the specific concepts of angels and demons in Christianity and Judaism are likely influenced by Zoroastrianism.

While it is true that other cultures had similar concepts of a devil or evil deity, the specific concept of a single entity that is in constant conflict with God is again unique to Zoroastrianism. The concept of a fallen angel or Satan in Christianity and Judaism is likely influenced by Zoroastrianism, particularly given the similarities in the descriptions of the Christian devil Satan and the Zoroastrian devil Angra Mainyu.

Finally, the article argues that the concept of heaven and hell, angels and demons, the devil, and the final resurrection were not borrowed from Zoroastrianism because the ancient Iranians worshipped gods called "Daevas" that were later considered demons by Zoroaster. However, this argument does not negate the numerous historical occurences of Zoroastrianism making contact and exerting influence on Jewish and Christian beliefs through the Persian Empire, as there are similarities to be found between their religious texts.

Overall, while the article attempts to refute the claim that Judaism and Christianity borrowed from Zoroastrianism, it fails to provide convincing evidence to support its argument.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today's 3H world thoughts and headcanons:

Is Almyra actually less religious than Fódlan?

There are various lines in the game that seem to imply that Fódlan is especially religious compared to other lands, from characters who are both from Fódlan and outside of it. One example is Edelgard after the CF Fódlan's Throat paralogue, another is Claude talking about his attitude towards gods/religions and including that as a part of why he's "an outsider" (to Fódlan and its dominant religion).

Thing is, as far as cultural motifs go: Almyra appears to be based off the Persian Empire (Achaemenid ~ maybe Sassanid?), or West~Central Asia generally. Among them, Zoroastrianism was pretty damn important to Persian Empire, politically and culturally, and there's even in-universe tidbits that point towards Zoroastrianism (or something similar) existing in Almyra.

And even if it's not as intense or literal as in Fódlan, where the supposed "ruling legitimacy" provided by the goddess is engrained in your blood, religion is still a very useful tool for rulers. No way kings in other lands didn't use "I can rule because a divine entity chose me" for advertisement.

So, my personal theory regarding whether Almyra is actually less religious than Fódlan is: yes and no/kind of.

I think Almyra is probably a lot more diverse in religion than Fódlan is, considering, again, the cultural/geographic motif mentioned above. West and Central Asia was/is a crossroad to all kinds of faiths, from Zoroastrianism to Abrahamic religions to Buddhism, Tengrism, so on. Following that, even if there is a specific religion that the king/ruling class uses for their legitimacy, they probably (by necessity) tolerate other religions more than Fódlan does, so to outsiders it would probably give the impression that they're not as dedicated to one specific religion overall, hence what Edelgard thinks.

At the same time, for Claude in specific, it's quite possible that it's actually the fact he grew up in Almyra that makes him underestimate how religious it is, because a lot of things that originate from/relate to religion is also just a part of the majority/mainstream culture. Like Christianity for many parts of Europe ~ Americas, or Buddhism for East Asia. And in return, while Fódlan is definitely pretty religious, the fact he's not familiar with the Church of Seiros probably makes the religious aspects stand out more to him compared to those who grew up there.

(Case in point: I'm Korean, not religious and wasn't raised religious, but stuff like Yeondeunghoe never registered to me as being overwhelmingly religious just because it's also considered a general part of Korean traditions. But when I think about it it's like... oh yeah that's actually a Buddhist thing right.)

In conclusion, if stuff about Church of Seiros got to Almyra at any point, then Seiros is probably included in the scripture of 3H world's Manichaenism alongside Zoroaster, Jesus, and Buddha.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Life of The Prophet Muhammad(pbuh): Calling the Tribes to Islam, the Allegiances of Aqaba and Migration to Madinah

Adhan is Determined

(1st year of the Hijrah / AD 622)

While in Mecca, Muslims used to pray secretly and perform salah in places out of everyone’s sight. Therefore, it was out of question to call people to prayer openly there.

However, the picture totally changed in Medina. There was religious freedom, then. Muslims could perform their prayers and worship freely. Their faith and conscious were not under pressure. Polytheists’ cruelty, oppression and insults were out of question.

Masjid an-Nabawi was built. However, a way of calling Muslims to come together in prayer times was not decided yet. So, Muslims used to come and wait for the prayer time and perform prayer when it was the time.

The Prophet’s Consultation with the Companions

One day the Honorable Messenger gathered his companions and consulted with them “what kind of a calling they needed to decide on.” Some companions suggested that they tolled a bell like Christians did; some suggested that they blew a horn like the Jews did and some suggested that they made a fire like Zoroastrians and took it up to somewhere high in prayer times.

The Prophet did not like any of these suggestions.

Then, Hazrat Umar took the floor and said: “O Messenger of Allah! Why do you not send a man to call people to prayer?”

The Honorable Messenger found Hazrat Umar’s suggestion appropriate and said to Hazrat Bilal: “Stand up, O Bilal, call out for prayer!”

.Upon this; Hazrat Bilal wandered streets of Medina, calling Muslims to prayer, shouting “As salah! As salah!” for a while.

Abdallah b. Zaid’s Dream

Abdallah bin Zaid from the Companions had a dream after a while. In his dream, he was taught the adhan the way it is today.

Hazrat Abdallah went up to the Prophet happily and told his dream as soon as the morning broke. The Honorable Messenger approved the call saying, “Inshaallah, this is a true dream!

Hazrat Abdallah taught the adhan (call to the prayer) to Hazrat Bilal by the order of the Honorable Messenger. Hazrat Bilal began to fill Medina skies with the adhan with his strong and loud voice:

Hazrat Umar Has the Same Dream

Having heard this voice echoing in Medina skies, Hazrat Umar got out of his house and appeared before the Honorable Messenger. When he learnt about the situation, he said: O Messenger of Allah! I swear by Allah who has sent you with the true religion that I saw the same dream as Abdallah!”

The Prophet praised Allah because two people had seen the same dream.

We can see that what a natural and decent religion Islam is from the determination of the way of call to prayer, too. The difference between tolling bells - so spiritless, meaningless, emotionless and flat -, blowing a horn or making a fire and “the adhan” - so meaningful and divine - which declares the divine truth of “tawhid” on earth, exclaiming the prophethood of the Honorable Messenger and therefore announcing all fundamentals of the belief to people is so great that they cannot even be compared.

Just as there are two sort of rights, ‘personal rights’ and ‘general rights,’ which are considered to be a sort of ‘God’s rights,’ so too are there two kinds of matters concerning the Shari‘a: Matters concerning individuals, and matters concerning the public; the latter ones are called ‘the marks of Islam.’

One of the greatest Islamic signs is the adhan which was legalized in the first year of the Hijrah and which declares the fundamentals of the religion. Badiuzzaman Said Nursi has got very significant explanations and evaluations on “Islamic Rules.” In the 29th Letter of his work named The Letters, he says: “There are certain matters of the Shari‘a concerning worship which are not tied to the reason, and are done because they are commanded. The reason for them is the command. There are others which have ‘reasonable meaning.’ That is, they possess some wisdom or benefit by reason of which they have been incorporated into the Shari‘a. But it is not the true reason or cause; the true reason is Divine command and prohibition.

Instances of wisdom or benefits cannot change those matters of ‘the marks of Islam’ which pertain to worship; their aspect of pertaining to worship preponderates and they may not be interfered with. They may not be changed, even for a hundred thousand benefits. Similarly, it may not be said that “the benefits of the Shari‘a are restricted to those that are known.” To suppose such a thing is wrong. Those benefits may rather be only one out of many instances of wisdom and purposes.” And then he records the following about the adhan which is an important mark of Islam:

“For instance, someone may say: “The wisdom and purpose of the call to prayer is to summon Muslims to prayer; in which case, firing a rifle would be sufficient.”

However, the foolish person does not know that it is only one benefit out of the thousands of the call to prayer. Even if the sound of a rifle shot provides that benefit, how, in the name of mankind, or in the name of the people of the town, can it take the place of the call to prayer, the means to proclaiming worship before Divine dominicality and the proclamation of Divine Unity, which is the greatest result of the creation of the universe and the result of mankind’s creation?”

#allah#god#islam#revert#convert#reverthelp#muslim#pray#quran#prayer#revert islam#convert islam#revert help team#help#islamhelp#conevrthelp#how to convert to islam#convert to islam#welcome to islam

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

I thought that “Jews got their ideas from Zoroastrians during the Babylonian Captivity” was no longer the consensus (I’ve always had difficulties with the idea regardless, at least in the way it’s usually presented)

Well, Jews definitely had to learn about what kind of thing their “god” is from someone who actually had a philosophical inquiry into Being, which is entirely absent from their own native metaphysics and not even very prominent in Egyptian. (Actually I don’t even know if Egypt had a philosophical ontology of any kind before Alexander brought the Greek kind.) Before the Babylonian captivity brought them to people, the Zoroastrians, who had some concept of the Absolute, Jews almost certainly thought Ha-Shem was just the best example of the same category as Marduk—even if they thought he was the only real one and were technically “monotheist” with regard to what they still took for a small-T theos. When he is actually Zerâna-Akerana, Infinite Being.

Zoroastrians were to those Jews as Platonism was to Philo and Aristotle was to Maimonides: the people whose philosophical framework they borrowed to explain and refine their own religion’s ideas.

3 notes

·

View notes