#zoroastrianism explained

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Video

tumblr

Explore the ancient wisdom of Zoroastrianism in our latest video! Uncover the fascinating history, beliefs, and practices of this monotheistic faith that dates back thousands of years. From the teachings of the prophet Zoroaster to the significance of fire in their rituals, this video provides a comprehensive insight into one of the world's oldest religions. Join us on a journey to understand the core tenets of Zoroastrianism and the vibrant community of Zoroastrians. Discover the enduring impact of this ancient faith on the world's religious tapestry. Don't miss out on this enlightening exploration! #Zoroastrianism #Zoroastrians #MonotheisticFaith #ReligiousHistory #AncientWisdom #Zoroaster #FaithAndBeliefs #CulturalHeritage #ReligiousDiversity #HistoricalPerspectives #viral #trending #explore

#zoroastrianism#religion#zoroaster#zoroastrians#what is zoroastrianism#overview of zoroastrianism#Monotheist#zoroastrianism explained#What is Zoroastrianism#Zoroastrianism#Islam#what is zoroastrianism religion#what is the ancient religion zoroastrianism#what kind of religion is zoroastrianism#who is zoroaster#zoroastrianism history#ancient iran#hinduism explained#what is buddhism#what is hinduism#zoroastrianism in iran#Polytheism#viral#trending#Explore More

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

how can you be so controversial and yet so brave

(reposted from Twitter)

Hey so, have I ever told you about the time I was at an interfaith event (my rabbi, who was on the panel, didn't want to be the only Jew there), and there was a panel with representatives of 7 different traditions, from Baha'i to Zoroastrian?

The setup was each panelist got asked the same question by the moderator, had 3 minutes to respond, and then they moved on to the next panelist.

The Christian dude talked for 8 minutes and kept waving off the poor, flustered, terminally polite Unitarian moderator.

The next panelist was a Hindu lady, who just said drily, "I'll try to keep my answer to under a minute so everyone else still has a chance to answer." (I, incidentally, am at a table with I think the only other non-Christian audience members, a handful of Muslims and a Zorastrian.)

So then we get to the audience questions part. No one's asking any questions, so finally I decide to get things rolling, and raise my hand and the very polite moderator comes over and gives me the mic.

I briefly explain Stendahl's concept of "holy envy" and ask what each of theirs is.

(If you're not familiar, Stendahl had 3 tenets for learning about other traditions, and one was leave room for "holy envy," being able to say, I am happy in my tradition and don't desire to convert, but this is something about another tradition that I admire and wish we had.)

The answers were lovely. My rabbi said she admired the Buddhist comfort with silence and wished we could learn to have that spaciousness in our practice. The Hindu said she admired the Jewish and Muslim commitment to social justice & changing, rather than accepting, the status quo.

The Christian dude said he envied that everyone else on the panel had the opportunity to newly accept Jesus.

I shit you not.

Dead silence. The Buddhist and Baha'i panelists are resolutely holding poker faces. The Hindu lady has placed her hands on the table and folded them and seems to be holding them very tightly. Over on the middle eastern end of the table, the rabbi, the imam, and the Zoroastrian lady are all leaning away from the Christian at identical angles with identical expressions of disgust. The terminally polite Unitarian moderator is literally wringing his hands in distress.

A Christian lady at the table next to me, somehow unable to pick up on the emotional currents in the room, sighs happily and says to her fellow church lady, "What a beautiful answer."

anyway I love my rabbi to death and would do anything for her

except attend another interfaith event

22K notes

·

View notes

Text

Explaining the mythological origins and namesake of Mithra (MHYK): a very long and probably unnecessary post by a mhyk obsessed mythology nerd

Let me just preface this by saying that I haven’t gone through any formal education in ancient history or religions (yet) and even if I’ve researched it quite a bit I’m still bound to make plenty of mistakes. Also my expertise lies in grecoroman myth and I only have very surface-level knowledge of the other religions I mention here, although I’ve recently gone down a rabbit hole in regards to specifically their portrayal of the mithraic figure because goddamnit those wizards have me in a stranglehold and if I can’t combine my two current hyperfixations what’s even the point.

As there is gonna be quite a few different Mithras mentioned I will be referring to the fictional Mithra as “Mithra (mhyk)”. If I mention any other Mithra/Mitra/Mithras assume I’m talking about the deity.

Also this text is quite long so read more under the cut:

As you may or may not know if you’ve read through Mithras (mhyk) wiki page he takes his name from persian mythology! However this is a bit of an oversimplification as Mithra actually appears in pre-Zoroastrian Persian myth, Zoroastrianism, Hinduism, Roman myth and Mithraism, although with slight variations in his name and more significant variations in his role and portrayal.

Unfortunately since I have no knowledge of japanese and am entirely basing my interpretation of mahoyaku off the english translations I can’t attest to if the romanji of his name is accurate nor if japanese translations of mithraic texts make any differentiation between the names of Mithra in the different religions in which he’s present, but going off the romanisation i’ve seen used his name is spelled “Mithra” which is the spelling used for the Mithra in persian mythology and zoroastrianism. In roman mythology and mithraism hes called “Mithras”, and in hinduism he’s called “Mitra”, so Mithra (mhyk) using that particular spelling for his name would imply that he’s more based on the pre-zoroastrian and zoroastrian Mithra.

However after reading about all different Mithras from the different religions I can find possible links and references to all Mithras in Mithras (mhyk) writing so I’m gonna talk about all of them anyways! I’m mostly gonna focus on Zoroastrianism and Mithraism tho since those are the ones I’m able to find the most information on!

The first mention of Mithra comes from 1400 BC where he is mentioned as a Vedic deity (gross oversimplification but Vedic religion is a sort of pre-cursor to Hinduism) and referred to as “Mitra”. He then seems to have spread to ancient Persia where he is adopted into the Persian pantheon, and when Zoroastrianism takes over as the dominant religion in Persia he continues to be a prevalent figure.

Zoroastrianism is (is not was because it’s actually still practiced! fun fact Freddie Mercury was a Zoroastrian) a dualistic religion that focuses on the fight between good and evil, with a supreme being commonly referred to as “Ahura Mazda” and an evil spirit referred to as “Angra Mainyu” whom he stands in conflict with. Gods from the earlier pre-zoroastrian religion are incorporated into Zoroastrianism as beings called “ahuras”and “daevas”, with a few divinities called “yazatas” standing directly under “Ahura Mazda”. One of these “yazatas” is Mithra!

Scholars argue whether Zoroastrianism should be considered a monotheistic or polytheistic religion but many choose to refer to yazatas and by extension Mithra as divine beings that are underneath god rather than actual gods (think like angels), with “Ahura Mazda” being the only true god. However wether or not Mithra counts as a god there are still some scholars that believe that he was worshipped kinda like one!

In Zoroastrianism Mithra is the yazata of justice, the sun, light, friendship (“Mitra” actually means friend!!! it can also mean “that which binds” or oath/contract/covenant), pacts, covenants, contracts and most notably for our purposes oaths. Yep, oaths. As in promises. Sound familiar?

As the keeper of oaths he observes the world and makes sure no-one breaks their promises, and if they do they suffer his wrath, which may have caused him to also sometimes be viewed as a god of war according to some scholars. Mithra follows the path of the sun during the day, and during the night he fights evil demons with a spiked club, which is why the sky is red at the break of dawn (as he smashes the demons to pieces). So yeah the deity Mithra doesn’t get any sleep either, although I find this more likely to be a coincidence than intentional lol. Mithra rides a chariot drawn by four horses with no shadows and gold and silver hooves. He’s described to have millions of eyes and ears that can observe any oath-breakers and arms that can stretch and aid his followers all throughout the world (reminds me of Mithras (mhyk) signature teleportation magic a bit).

Mithra is also one of the three judges in the afterlife. When someone dies the zoroastrians believe the soul remains in the body for three days, after which it goes to the Chinwad bridge. Mithra, Srosh and Rashn judges the soul and if it’s deemed to have lived a good life the bridge widens and the soul can pass through with ease, but if it’s deemed to have lived an evil life the bridge becomes narrow and the soul falls down into the abyss below. The associations with death really aren’t as strong in Mithra as they are in Mithra (mhyk), but its still interesting to see that they’re there.

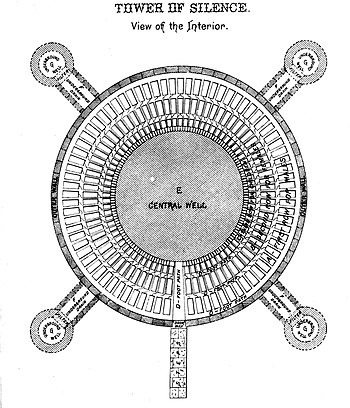

Mithra is also associated with fire and running water, both of which are considered holy in Zoroastrianism. (Old zoroastrians used to dispose of corpses by tying them up and letting birds eat them as the body is considered impure after the soul departs and thus can’t be cremated or risk getting near running water (as fire and running water is holy). thats not really related to Mithra I just think that’s interesting lol.)

Like many other deities Mithra was later picked up by the romans, where he became known as Mithras. Mithras shares very few similarities with the zoroastrian Mithra aside from etymological links and a connection to the sun, and it’s widely agreed that Mithras is simply the case of romans seeing the worship of Mithra and adopting the name rather than any actual zoroastrians spreading their worship to Rome. A lot of the time in antiquity people would make connections between gods that have similar roles from different cultures and associate them with eachother, and because of this Mithras became linked with sun gods such as Helios, Apollo and Sol. He also became known as “Sol Invictus” which means “The undefeated sun god”! Poor Mithra (mhyk) kinda failed the whole undefeated thing..

One of the most famous mystery cults and an early competitor to christianity was actually dedicated to the worship of Mithras. A “mystery cult” in antiquity refers to a cult which only those initiated are allowed to take part in, and “cult” when referring to ancient cults doesn’t have the same connotations as modern day cults and simply means a sub-sect of a bigger religion with it’s own teachings and rites. Although i’m not gonna lie the cult of Mithras is kinda giving me scientology vibes so. Yeah. Maybe it is a cult cult.

The cult of Mithras, commonly referred to as Mithraism by modern scholars, was a popular cult around the first to fourth century CE. Mithraism was mostly popular among soldiers, merchants and slaves and it’s worshippers consisted mainly of men. I’ve seen split opinions among scholars on wether women were allowed in the cult, but even if they were they most likely didn’t have the ability to climb the ranks in the same way men did. Mithraism had a rank system, where members could do work or pay probably (hence the earlier scientology comment) to learn more of the secrets of the cult and gain higher status.

There were 7 different ranks:

Corax (raven), Nymphus (bridegroom), Miles (soldier), Perses (persian), Heliodromus (sun-runner) and Pater (father), and each rank had their own protective planetary god and symbols.

Mithraism had some sort of an initiation ritual, however we don’t know exactly what that ritual entailed. It’s referenced as including both extreme heat and extreme cold, and inscriptions have been found where an initiate into the cult writes about having been “born again”. Christian writers have described the initiation ritual as being extremely brutal, but this likely isn’t true as those sources are incredibly biased with many christians standing in direct conflict with Mithraism.

The worship of Mithras took place in underground temples known as “Mithreums”. These Mithreums were often formed like caves, and had several altars, seats, a place to prepare food and several reliefs depicting Mithras in his various myths. The most central myth to Mithraism seems to have been a tauroctony, or in other words a slaying of a bull. All Mithraums have a depiction of the tauroctony in them.

In the tauroctony Mithras is shown grappling a bull and stabbing it with a dagger, with several animals almost always including (but not necessarily limited to) a dog, a raven, a snake and a scorpion surrounding them. Wheat grows out of the bulls tail, and grapes well out from the open wound in its throat. Watching down on them is Sol (a sun god heavily linked to and sometimes synonymous with Mithras) and Luna (a moon goddess), and two twins named Cautes and Cautopates stand on either side holding torches, with Cautes torch pointing upwards and Cautopates torch pointing downwards.

Unfortunately since Mithraism was a mystery cult there is not much written down about it’s teachings from actual practitioners, and most written sources we have are either heavily biased, written way after Mithraism stopped being practiced, or both. Most of the information we can gather thus comes from these reliefs, so interpreting what the myth is really about is a bit challenging.

Some scholars have interpreted it to be a sort of creation myth (kinda Ymir style if you’re familiar with norse mythology), which could be further cemented by the possible similarities between some iconography in Mithras birth and Orphic (another cult (although not a mystery one) don’t even get me started we’ll be here all day) creation myth.

Speaking of Mithras birth, he gets born out of a rock! Sometimes as a child but usually as a grown man, and often the torch-bearing twins are present at his birth too. This is also gathered from mostly reliefs and short inscriptions so we really don’t know much about it.

There is also reliefs of some sort of water miracle where Mithras shoots a rock with a bow and arrow and summons water from it, depictions of Mithras hunting the bull, a banquet where Mithras and Sol feast on the bull, a handshake between Sol and Mithras, and Sol and Mithras ascending to the heavens in a chariot. There is also a statue of a lion headed god with a snake wrapping around its body that commonly shows up in mithreums, however we don’t really know who this god is.

Mithraism seems to be heavily linked to astrology and many believe the figures in the tauroctony to be representative of different celestial bodies and star signs, however theres a lot of disagreement in regards to which figure represents what. Some even link Mithraism to some sort of astral ascension, but this is hotly debated.

Mithraism is also believed by some to have inspired christianity, with Mithras often being compared to Jesus. I personally don’t really buy this and see other mystery cults such as those surrounding Dionysus to be more likely to have been inspiration for Jesus, but it’s at the very least possible that Mithraism influenced christmas to be on the 25th of December. According to some scholars Mithras birthday was celebrated the 25th of December (others argue it was more a general celebration of the sun) and early christians may have chosen to put christmas on that day to directly compete with Mithraism. Additionally, many mithrean rituals have been compared to christian rituals and were described by christians at the time as evil imitations of christian practices.

When christianity became the state religion in rome Mithraism quickly declined, but during a good while Mithraism was just as widespread and popular as christianity and some believe that had things gone differently Mithraism could’ve ended up being an important world religion still to this day.

Now all of this is really interesting, but if you came here for Mithra (mhyk) it may not be all that relevant. Lemme tell you what’s more relevant tho: The bull is the moon. Or well more accurately, some scholars believe the bull to represent the moon.

Bulls were sometimes a symbol for the moon in antiquity due to their crescent shaped horns and their association with the moon goddess Selene/Luna. This, in combination with the imagery of Sol and Luna on opposing sides of the depictions of the tauroctony has made some believe that the scene depicts Mithras triumph over the moon and by extension death and darkness.

Additionally, Mitra (the Vedic Hindu version of Mithras) actually has a similar bull slaying story in which he reluctantly participates in the sacrifice of the moon god Soma who takes the form of a bull, so yeah multiple Mithras may do moon slaying. Ig Mithra (mhyk) fights the moon in every universe.

There’s obviously a lot more about all these deities I haven’t gone over but finding credible sources is unfortunately a bit difficult and if I continue I may be here for weeks so!! That’s all for now! I doubt Mahoyakus creators actually knew about all this, but I still think its really neat they chose Mithra as the name for their character considering hes such an interesting mythological figure!! Also ig the Cult of Mithras lives on in all the crazy Mahoyaku fans simping over Mithra (mhyk)..

#ik this isnt art but i put hours into researching it and i think tumblr needs to hear it#if anyone wants me to elaborate i can and will do so#mhyk literary references have me in a stranglehold#mahotsukai no yakusoku#mahoyaku#mhyk#promise of wizard#mithra#mithra mahoyaku

57 notes

·

View notes

Note

There is a difference between disrespected and being uncomfy and I appreciate your ability to at least see the nuance.

If you looked at the “show more” tab on the quotation link, it would have given you more options but I didn’t think I needed to explain that 🙃 The semantics of things seems silly after a point but I think we’re both still coming at a place of valid intention.

Similarly to some of my arguments it feels like you still neglect that history is full of things older and outside of the Jewish tradition (like Zoroastrianism, Phoenician/Canaanite tribes that were largely wiped out BECAUSE of tribal conflict that included a WIDE array of Jewish people up until, if I’m not mistaken, basically Babylon and even some of the literature around Ur and the Nile from how human became sentient has some oddly universal stories (forbidden fruit, the allegorical nature of the stars, the fall of man with Cain (farming) and Abel (hunter gatherer).

The point of this whole discussion stems from the argument from tradition which feels fallacious given how no one ACTUALLY claims anything after a certain point so why get your knickers in a twist to point out that, hey, maybe the nuance exists in ways that are legitimately concerning like why the IDF is systemically pulling fascist moves against Palestinians.

I appreciate your input nonetheless and think we largely agree, it’s just the gatekeeping piece that genuinely confuses me because it feels inherently oppressive to people who may think that the 40+ crowd who conveniently seem to be majority if not only men, get to dictate the narrative of how a specific religion operates, ESPECIALLY if that means *checks notes again* chopping a part of a baby’s dick off????

You're right, there is a difference between being disrespected and being un-comfy. I’m not un-comfy.

The “show more” tab under the famously inaccurate Google AI overview? Your argument for the reason that you can use quotes to paraphrase is that a hallucinating AI says so? I just want to be sure that’s your argument before I click the tab and check…

It still doesn’t say that. Like, that’s a bad argument because AI is not a valid counter to actual sources, but it’s also a bad argument because nothing in the link you gave actually said you could do what you did anyway. And then you tried to make me look foolish by implying that you need to explain to me that I just needed to click the “show more” tab. You might think we both have good intentions, but I am seriously doubting yours.

You’re shifting goalposts here. We started talking specifically about Jews and Jewish populations. I’m not neglecting the fact that history is full of things older than Judaism and outside of Judaism, they’re just simply not relevant to the specific conversation we’re having. And I’m not sure what you think I’m arguing from tradition, either. Unless you mean Jewish traditions themselves? I think it’s fair to say that our traditions are our traditions. If they need changing, that is for the Jewish community to decide amongst ourselves, not a conversation that you get to take part in.

I’m sorry you feel gatekept, but not everything in the world is available for you to take. Specifically closed religions, especially closed religions of minority groups, are not available to you. And I think this is a good thing. Jews are outnumbered on this planet 500 to one. If Judaism were an open religion, it would not be hard for a bunch of Christians to declare themselves Jewish, and then change Jewish practice to include Jesus. Like, to be very specific, there are more Evangelical Christian Zionists in the United States than there are Jews in the entire world. If they all declared themselves Jewish, but said they were keeping Jesus, the MAJORITY of Jews would be followers of Jesus. The gatekeeping is to ensure that changes to how we practice our religion and our culture come from us, and not overwhelming outside influences.

Circumcision is part of an important Jewish ritual. If Jews decide to stop observing that ritual, that decision needs to come from Jews, which you are not. Your opinion here simply doesn’t matter. I know that as a cultural Christian you need to feel centered in every conversation, but this one doesn’t involve you. In addition, the way you talk about what is really a beautiful ritual is disrespectful to the point of being dangerous. Christian obsession over circumcision has led to accusations of Jewish pedophilia and Jews doing satanic rituals with the collected foreskins, which have led to attacks against Jewish communities.

I’m sorry you’re not happy with your circumcision, though again, unless it was done as part of the Jewish tradition (and from what you said it seems like it wasn’t) then I’m not sure why you’re so hung up on Jews doing it. Why not start by advocating for non-Jews to stop doing it, as that seems like it would be more relevant to your personal trauma? Your obsession with the Jewish practice is antisemitic; you need to let it go.

#asks and answers#antisemitism#goydacity#my notifications are showing me that a few dozen people are finding this entertaining so we'll let it go for a bit longer

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here's what bugs me about chapter 99 "The Dubloon":

Stubb's perspective is a really interesting device through wich to show other characters' interpretations and I can appreciate what Melville did with that to some degree. However I am still angry that we don't get to see, what Queequeg and Fedallah think about the coin, because Stubb, who is a racist asshole, is blocking the way. The goddamn old Manxman, who by comparison is so much less important of a character, get's his own little monologue, but Queequeg and Fedallah don't get to say a single word.

I feel like we were robbed of two extremely interesting perspectives here.

About Queequeg we at least get to know what he's physically doing, if not what he thinks. He seems to be comparing something about the coin to his tattoos. Stubb of course dismisses this as some kind of superstition and even supposes that Queequeg doesn't really know what a coin is (??????? wtf Stubb!?).

In actuality, what Queequeg is doing isn't even that dissimilar from Stubb's hermeneutics. Both of them try to decifer the coin's meaning by consulting some kind of document as a frame of reference. In Stubb's case that's his almanac and the Massachusetts calendar, but for Queequeg it's his tattoos.

I wish we could have known, what they mean and what Queequeg sees in that coin, but alas, this book and Stubb refuse to tell us. Queequegs thoughts remain a mystery most times just like his tattoos.

And then there's Fedallah.

I could rant for hours about how shittily the entire narrative and all the other characters treat him and this chapter is exemplary of that.

The first thing Stubb does upon seeing Fedallah come up to the dubloon is call him a "ghost-devil" and speculate on how he's supposedly hiding his devil's tail and hooves. We get to know that Fedallah "makes a sign to the sign and bows himself", but Stubb doesn't seem to know that gesture and therefore doesn't care to describe it any further, explaining it away as just some weird thing he does because he's a "fire worshipper" (as far as I know a wildly incorrect term for Zoroastrians) and the're a sun on the coin.

It's wild to me that we do not get even the slightest real glimpse into Fedallah's mind here. He is probably the one person on the ship who gets the most insight into Ahab's thoughts and feelings. He's closest to Ahab and he knows what is going on inside the captain's head and what fate the ship is heading towards. That coin on the mast that signifies Ahab's mission must mean something to him. I bet he has so many interesting thoughts about it and about Ahab, but all we get is Stubb's racist superstitions.

And really, this is what the entire book is like, clncerning this character. Fedallah does nothing objectively wrong, but the rest of the crew constantly regard him with suspicion, going so far as to claim he's the literal devil and the narrative pretty much never lets the man speak for himself about what he thinks of all this.

As you might have guessed, I'm pretty angry about this, because I think there's so many missed opportunities here and they just get thrown overboard because Stubb (the crew, Ishmael as a narrator, the entire narrative) can't be normal about non-white characters.

#moby dick#queequeg#fedallah#chapter 99 “The Dubloon”#stubb#stubb is an asshole#ishmael#herman melville#literary racism#henry rants

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

List of Mythic Creatures

Q: WHAT IS THIS??!

A: This is an alphabetically sorted list of all mythic creatures I could find on Wikipedia. The names are (mostly) identical to the name that will bring up the wiki page.*

Q: All mythic creatures on wikipedia???

A: There are a few omissions: I found there were too many lake monsters so those I didn't exhaustively include. Wikipedia has a lot more information about Greek individual figures than individual figures from other cultures (like Achilles or Glauce or Dioxippe or Ajax) and when those figures are members of a mythic group (amazons, nymphs, etc.) I included them in this list, but the list may skew in favour of Greek mythic women with fewer male figures. Also I have included some gods, goddesses and non-binary deities but just like with the lake monsters, did not include most of the Wiki pages on godheads of the world. But the list should be fairly exhaustive when it comes to heavenly beings (elves of alfheim, gandharvas, horae and so on) who serve the gods in their divine abodes.

Q: Why are hobbits on the list? Tolkien made those up, right?

A: Well technically there are lists of creatures from folklore and one of those lists, which Tolkien came across, lists hobbits. It doesn't explain what hobbits are and they aren't documented anywhere else, but that may be the origin of the word hobbit.

Q: Why are some of these not actual creatures?

A: folktales that make mention of unique mythic creatures have been included. For example "The Red Ettin" is a English folktale that features herds of two-headed bulls and cows. In other cases, Wikipedia has pages like "Aboriginal Australian Creatures" or "Abenaki & Mi'kmaq beings" which are worth looking at because they provide more mythic creatures that don't have individual pages.

Q: Why are some entries styled "Savanello - Salvanello" or "Dwarf - Dwarves"

A: one of the terms is the singular and the other the plural. The list is a bit peculiar, sorry.

Q: How would you recommend this list is used?

A: You can use it any way you like, just keep in mind that some beings on this list are sacred and ideally try to be culturally sensitive about that. For example, some Ojibwe people are not exactly happy that one of their unnameable spirits has been publicly named, misspelled, attached to anti-Native stereotypes (see also here) and then completely misrepresented and trivialized as a horror monster in pop culture and so the "wendigo" comes with all that baggage, as do many other creatures on this list.

Usually if a creature is from a Neolithic / Bronze Age / Iron Age culture like Egypt or North & South Mesopotamia (Akkadian, Assyrian & Sumerian, Babylonian) there is no one who is going to raise valid ethical concerns around the use of your creature.

Similarly, if something is a generic fantasyland creature (elf, dwarf, dragon, ghost, giant, mermaid etc.) or from Greek and Roman sources (sirens, minotaurs, catoblepas) or medieval bestiaries (hydrus, iaculus) you can flesh those out with more research, but I don't think you will run into ethical problems.

But with a lot of other creatures, outreach to that community has value, because otherwise its not just a fantasy work being authored, but also some serious inter-cultural tensions. Stephenie Meyer, who decided to add Qileute shapeshifters into Twilight but never consulted Qileute and doesn't support their community in any way, is a example. There is no need to follow it.

By Region & Culture

Part 1: Indigenous Australians & Indigenous America

Part 2: Settler Colonies & Diasporas of Australia & Americas

Part 3: Europe (Basque, Rome, Viking, Great Britain)

Part 4: Greek

Part 5: East Europe, Northwest Asia

Part 6: Medieval Europe (plus Renaissance)

Part 7: Orthodox Religions (Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Zoroastrianism, Gnosticism, Demon Summoning Books, etc.)

Part 8: Asia and South Pacific

Part 9: Africa

Part 10: Other

Creatures sorted by Type

Letter A

Letters B to Z are in the works.

THE LIST:

This wiki page mentions "a horde of tiny creatures the size of frogs that had spines" https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sea_monster;

9 Mothers of Heimdallr;

Á Bao A Qu; A Hut on Chicken Legs; Aamon; Aana Marutha; Aani; Aatxe; Aayaase; Abaahy; Abaasy; Ababil; Ababinili; Abada; Äbädä; Abaddon; Abaia; Abarimon; Abarta; Abasy; Abath; Abcán; Abchanchu; Abenaki & Mi'kmaq beings; Abere; Abezethibou; Ba (personality); Baak; Baal Berith; Baba Yaga; Babay; Babi ngepet; Babys (a satyr's brother); Bacchae; Bacchantes; Baccoo; Badalisc; Badb; Bael; Bagany; Bahamut; Bahkauv; Bai Baianai; Bai Lung Ma; Bai Suzhen; Bai Ze; Bakasura; Bake-danuki; Bake-kujira; Bakemono; Bakeneko; Bakezōri; Baku; Bakunawa; Bakwas; Balaur; Bal-Bal; Baldanders; Ball-tailed cat; Baloma; Balor; Baloz; Bánánach; Banchō; Bannik; Banshee; Banyoles monster; Bao Si; Baobhan Sith; Baphomet; Bar Juchne; Bar yokni; Barabao; Barbarika; Barbatos; Bardha; Barghest; Barmanou; Barnacle Goose; Barometz; Barong; Barstuk; Barstukken; Baš Čelik; Basa-Andrée; Basadone; Basajaun; Basa-Juan; Basan; Bashe; Basilisco Chilote; Basilisk; Bašmu; Basnak Dau; Basty; Bathin; Batibat; Batraz; Baubo; Bauchan; Bauk; Baykok; Beaman Monster; Bean-nighe; Beansìth; Bear Lake Monster; Bearers of the Throne; Beast of Beinn a' Bheithir; Beast of Bladenboro; Beast of Busco; Beast of Dean; Beast of Gévaudan; Bebryces; Bedivere; Beelzebub; Beerwolf; Befana; Behemoth; Beings of Irkalla or Kur; Beithir; Beleth; Belial; Bell Witch; Belled buzzard; Belphegor; Belsnickel; Bendith y Mamau; Bengali myths; Bennu; Ben-Varrey; Benzaiten; Berbalang; Berberoka; Bergmanli; Bergmönch; Bergsrå; Bernardo Carpio; Berserker; Bessie; Bestial Beast; Betobeto-san; Betram de Shotts; Bhagadatta; Bhargava; Bhoma; Bhoota; Bhramari; Bhringi; Bi Fang bird; Biasd Bheulach; Bichura; Bicorn; Bieresel; Bies; Bifrons (demon); Big Ghoul (dragon); Bigfoot; Bilbze; Billy Blind; Bilwiss; Binbōgami; Binidica; Biróg; Biscione; Bishop Fish; Bisterne Dragon; Biwa-bokuboku; Bixi; Black Annis; Black Arab; Black Dog; Black Dwarfs; Black Hound; Black Panther; Black Shuck; Black Tortoise; Blafard; Blanquettes; Błędnica; Blemmyes; Blodeuwedd; Bloody Bones; Bloody Caps; Bloody Mary; Blud; Błudnik; Blue Ben; Blue Lady of Verdala Palace; Blue Men of the Minch; Blue Star Kachina; Bluecap; Blunderbore; Bobak; Böcke; Bockschitt; Bodach na Croibhe Moire; Bodach; Bodachan Sabhaill; Bogeyman; Boggart; Bogle; Böhlers-Männchen; Boiuna; Bonnacon; Bonnes Dames; Boo hag; Boobrie; Borda; Born Noz; Boroboroton; Boruta; Botis; Boto; Boto_and_Dolphin_Spirits; Bottom (Moerae); Boudiguets; Bøyg; Božalość; Božić; Brag; Bragmanni; Brahmahatya; Brahmarākṣasaḥ; Bramrachokh; Bran and Sceólang; Brazen Head; Bregostani; Bregosténe; Bremusa; Brendan the Navigator; Brenin Llwyd; Br'er Rabbit; Bres; British Wild Cats; Broichan; Brokkr; Brosno dragon; Brown Man of the Muirs; Brown Mountain Lights; Browney; Brownie - Brownies; Broxa; Bruja; Brunnmigi; Bubak; Bucca; Bucentaur; Buckriders; Buda; Buer; Buffardello; Bugbear; Buggane; Bugul Noz; Bukavac; Bukit Timah Monkey Man; Bulgae; Bull of Heaven; Bumba Meu Boi; Bune; Bungisngis; Bunyip; Bunzi; Buraq; Burrokeet; Burryman; Buru; Busaw; Buschgrossmutter; Buschweibchen; Bushyasta; Buso; Busós; Butatsch Cun Ilgs; Butter Sprite; Butzemann; Butzen; Buwch Frech; Bwbach; Bwciod; Byangoma; Byōbunozoki; Bysen;

C' Horriquets; Caballo marino chilote; Caballucos del Diablu; Cabeiri; Caca; Caccavecchia; Cacodaemon; Cactus cat; Cacus; Cadborosaurus; Cadejo; Caelia; Caeneus; Cailleach; Caim (demon); Cain bairns; Caipora; Cakrasaṃvara Tantra; Caladrius; Calafia; Calcatràpole; Caleuche; Calingae; Callicantzaroi; Calliste; Callithyia of Argos; Calydonian Boar; Calygreyhound; Camahueto; Camazotz; Cambion; Camilla; Campe; Cancer; Candelas; Cangjie; Čanotila; Căpcăun; Capelobo; Capkin; Carbuncle; Careto; Carikines; Carman; Carranco; Cas Corach; Catalan Creatures; Catez; Cath Palug; Cathbad; Catoblepas; Cat-sìth; Cattle of Helios; Cauchemar; Caucones; Cauld Lad of Hylton; Caveman; Ceasg; Ceffyl Dŵr; Celaeno; Centaur - Centaurs; Centaur_Early Art; Centaurides; Cerastes; Cerberus; Cercopes; Ceryneian Hind; Cethlenn; Ceto; Cetus; Ceuthonymus; Cha kla; Chai nenesi; Chakora; Chakwaina; Chalkydri; Chalybes; Champ; Chamrosh; Chana and Munda; Chaná myths; Chaneque; Chang; Changeling; Changelings Chervan; Čhápa; Charun; Charybdis; Chasca; Chaturbhuja; Chaveyo; Chedipe; Chemosh; Chenoo; Chepi; Chernava; Cherubim; Cherufe; Chesma iyesi; Chessie; Cheval Gauvin; Cheval Mallet; Chèvres Dansantes; Chi; Chichevache; Chickcharney; Chidambara Rahasiyam; Chilote Creatures; Chilseok; Chimera; Chimimōryō; Chimke; Chinas; Chindi; Chinese guardian lions; Chinese Monkey Creatures; Chinese serpent killed by Li Ji; Chinese Souls; Chir Batti; Chiron; Chitrāngada; Chiwen; Chiyou; Chōchinbi; Chōchin'obake; Choctaw myths; Chol; Chonchon; Choronzon (demon); Chort; Christchurch Dragon; Chromandi; Chronicon; Chrügeli; Chrysanthis; Chrysaor; Chrysopeleia; Chullachaki; Chullachaqui; Chupacabra; Church grim; Churel; Churn Milk Peg; Chut; Chyavana; Cichol Gricenchos; Ciguapa; Cihuateteo; Cikavac; Cimbrian seeresses; Cinciut; Cinnamologus; Cipactli; Cipitio; Cirein-cròin; Cissus; City God; Clíodhna; Clonie (Amazon); Clotho; Clurican; Coblynau; Cocadrìlle; Cock Lane Ghost; Cockatrice; Coco; Cocollona; Cofgod; Coi-coi vilu; Cola Pesce; Colbrand (giant); Colo Colo; Colombian Creatures; Colossus; Colt pixie; Comte Arnau; Conand; Çor; Coribantes; Corics; Cormoran (giant); Cornandonet Dû; Cornflower Wraith; Corrandonnets; Corriquets; Corson (demon); Corus; Corybantes; Courètes; Coyote_Native; Coyote_Navajo; Creatures from Vetala Tales; Creatures of Azerbaijan; Cressie; Cretan Bull_minotaur's sire; Creusa; Crinaeae; Crions; Crocotta; Crom Cruach; Crommyonian Sow; Cryptid whale; Cryptid; Cuegle; Cuélebre; Cula; Culards; Čuma; Cupid; Curetes; Curupira; Cù-sìth; Cŵn Annwn; Cyborg; Cychreides; Cyclops; Cyhyraeth; Cyllarus; Cymidei Cymeinfoll; Cynocephali; Cythraul;

Daayan; Dab; Dactyls; Daemon; Daeva; Dagon; Dagr; Dahu; Dahut; Daidarabotchi; Daikokuten; Daimon; Daitya; Daji; Dajjal; Dakhanavar; Ḍākinī; Daksha yajna; Daksha; Dalaketnon; Dalhan; Damasen; Damballa; Dames Blanches; Dames Vertes; Danava; Dandan; Dando's Dogs; Daniel (angel); Danzaburou-danuki; Daoine Sidhe; Daphnaie; Dark Watchers; Darrhon; Daruka; Datsue-ba; Dawon; Day of the Dead; Dead Sea Apes; Death; Ded Moroz; Deer Lady; Deer Woman; Deianeira; Deildegast; Deity; Delphyne; Dema deity; Demigod; Demogorgon; Demoiselles Blanches; Demon - Demons; Demon (list); Demon Cat; Demons (Ars Goetia) (List); Demons (Christianity and sex); Demons in Mandaeism; Demons of the Dictionnaire Infernal; Dēnglung; Derimacheia; Derinoe; Despoina_Goddess; Destroying Angel; Dev; Deva people; Devak; Devapi; Devas; Devatas; Devil Bird; Devil Boruta; Devil; Dewey Lake Monster; Dhampir; Dharanendra; Di Penates; Di sma undar jordi; Dialen; Dies feminae; Dilung; Dimonis-Boyets; Dingonek; Dioxippe; Dip; Dipsa; Dirawong; Disir; Diting; Div; Div-e Sepid; Dive Ženy; Dive; Djadadjii; Djall; Djieien; Dobhar-chú; Dobrynyna Nikitich; Dodomeki; Dogs in Chinese mythology; Dokkaebi bangmangi; Dokkaebi; Dökkálfar; Doliones; Dolphin; Domovoi; Donamula; Doñas de fuera; Dong Yong and the Seventh Fairy; Donn Cúailnge; Doppelgänger; Dormarch; Dōsojin; Double-headed serpent; Douen; Dǒumǔ; Dover Demon; Drac; Draconcopedes; Dragon of Beowulf; Dragon of Mordiford; Dragon of the North; Dragon turtle; Dragon; Dragons of St. Leonard's forest; Dragon's Teeth; Drakaina; Drake; Drangue; Drapé; Draugr; Drekavac; Drioma; Drop Bear; Droug-Speret; Drude; Drummer of Tedworth; Druon Antigoon; Dryad; Duende; Dulagal; Dullahan; Dumah; Dun Cow; Dungavenhooter; Dunnie; Dunters; Duppy; Durgamasura; Durukti; Dusios; Dvalinn; Dvarapala; Dvipa; Dvorovoy; Dwarf - Dwarfs, Dwarves; Dybbuk; Dysnomia; Dzedka; Dziwożona; Dzoavits; Dzunuḵ̓wa;

Each-uisge; Eagles in Myth; Easter Bilby; Easter Bunny; Eate (Basque god); Ebajalg; Ebu gogo; Echeneis; Echidna; Echtra; Éclaireux; Edimmu; Egbere; Egg Ghost; Egoi; Ehon Hyaku Monogatari; Eidolon; Eikþyrnir; Eingana; Einherjar; Eisenhütel; Eisheth Zenumin; Ekek; Ekerken; Eki (Basque goddess); Ekke Nekkepenn; Ekpo Nka-Owo; El Hombre Caimán; El Naddaha; El Sombrerón; El Tío; Elate; Elatha; Elbow witches; Elder Fathers; Elder Mother; Elegast; Eleionomae; Elemental; Elf - Elfs, Elves; Elf Fire; Elf King's Tune; Elflebceuf; Elfor; Elioud; Ellefolk; Ellemen; Ellén Trechend; Ellert and Brammert (giants); Elli; Ellylldan; Ellyllon; Eloko - Biloko; Elwetritsch; Emere; Emishi; Emmet; Emperor Norton; Empusa; En_Albanian_Deity; Enbarr; Enceladus; Enchanted Moura; Endill; Enenra; Enfield Monster; Enfield; Engkanto; English Fairies; Engue; Enorches; Eoteto; Epiales; Epimeliad; Epiphron; Erchitu; Erdbibberli; Erdhenne; Erdluitle; Erdmännchen; Erdweibchen; Ergene iyesi; Eriboea; Erinyes; Erkenek; Erlking; Erotes; Erymanthian boar; Estonian Creatures; Estries; Ethiopian pegasus; Ethiopian superstition; Ethniu; Etiäinen; Ettin; Euryale; Eurybius; Eurymedon; Eurynome; Eurynomos; Eurypyle; Euxantius; Ev iyesi; Evandre; Ewiger Jäger; Exoticas;

Fachan; Fadas; Fadhas; Fáfnir; Fäies; Failinis; Fainen; Fair Family; Fair Folk; Fair Janet; Fairy - Fairies; Fairy Queen; Fairy story (Northumbria); Falak; Fallen Angel (Book of Enoch); Fallen Angel; Familiar; Fangfeng; Fänggen; Fangxiangshi; Farfadet - Farfadets; Farfarelli; Farisees; Farises; Fasolt; Fastachee; Fata Acquilina; Fata Alcina; Fata Culina; Fata Morgana; Fata Sibiana; Fate Marine; Fates; Father Frost; Fatia; Fatuae; Faun, Faunus - Faunae, Fauni; Faustulus; Fayettes; Fayules; Fear Doirich; Fear gorta; Feathag; Feathered Serpent; Fée de Vertiges; Feeorin; Fées; Féetauds; Feilian; Feilung; Feldgeister; Fenetten; Feng; Fènghuáng; Fengli; Fenodyree; Fenrir; Ferragut; Fetch; Feuermann; Fext; Fiery Flying Serpent; Fiery serpents; Fin; Finfolk; Finvarra; Finzweiberl; Fioles; Fionn mac Cumhaill; Fionnuala; Fions; Fir Bolg; Fir Darrig; Firebird; Fire-Drakes; Firefox; Fish-man of Lierganes; Fjölvar; Fjörgyn and Fjörgynn; Flaming Teeth; Flathead Lake Monster; Flatwoods Monster; Flower Fairies; Flying Africans; Flying Head; Flying Horse of Gansu; Fog Mannikins; Folaton; Folgie; Folklore of the Maldives; Folktales of Mexico; Follet; Folletti; Fomorian; Foras; Forest Bull; Forest Fathers; Forgetful Folk; Forneus (demon); Fort Manoel Ghost; Foryna; Fossegrim; Fouke Monster; Fouletot; Foulta; Fountain Women; Four Perils; Fox Spirit; Frairies; Fratuzzo; Frau Ellhorn; Frau Holle; Frau Holunder; Fraus; Fravashi; French Mythic Creatures and Saints; Freybug; Frohn; Frost Giant; Fuath; Fuddittu; Fuglietti; Fujettu; Fūjin; Fulad-zereh; Funayūrei; Fuochi Fatui; Furaribi; Fur-bearing trout; Furcas (demon); Furfur (demon); Furutsubaki-no-rei; Fury; Futakuchi-onna; Füttermännchen; Fuxi; Fuzanglung; Fuzhu; Fylgiar;

Gaap; Gaasyendietha; Gabija; Gādhi; Gaf; Ga-gorib; Gagoze; Gaizkiñ; Gaja; Gajamina; Gajasimha; Galatea; Gale; Galehaut; Galgemännlein; Gallinipper; Gamayun; Gambara; Gamigin; Gaṇa; Gancanagh; Gandaberunda; Gandharva; Gangcheori; Gangr; Ganna; Gaoh; Gaokerena; Garb mac Stairn; Gargarians; Gargoyle; Garkain; Garmr; Garuda; Gashadokuro; Gasin (house god); Gatipedro; Gaueko; Gavaevodata; Gayant; Gazeka; Gazu Hyakki Yagyō; Gegenees; Gelin; Gello; Gemory; Genius loci; Genius; Gerana; Germakochi; German; Geryon; Ghaddar; Ghillie Dhu; Ghosayatra Parva; Ghost; Ghostly Rider; Ghosts in Chinese culture; Ghosts in Mesopotamian culture; Ghoul; Giane; Giant Water Lily Legend; Giant; Gigantes; Gigelorum; Gillygaloo; Girimekhala; Girt Dog of Ennerdale; Giu; Gjenganger; Glaistig; Glas Gaibhnenn; Glashan; Glashtyn; Glatisant; Glauce; Glawackus; Glenr; Globster; Gloucester sea serpent; Glucksmännchen; Gnome; Go I know not whither and fetch I know not what; Goblin - Goblins; Goblin-Groom; Gochihr; Gog and Magog; Gogmagog; Gohō dōji; Gold Duck; Gold-digging ant; Golden Bear; Golden Goose; Goldenhorn; Golem; Gommes; Gomukha; Gonakadet; Gonggong; Good Folk; Good Neighbors from the Sunset Land; Goodfellows; Goofus Bird; Goram and Vincent (giants); Gorgades; Gorgon - Gorgons; Gorgophone; Gormshuil Mhòr na Maighe; Goryō; Gotwergi; Graeae; Grahana; Grand Grimoire; Grandinili; Graoully; Gration; Green Man; Gremlin; Grendel; Grendel's Mother; Grey Alien; Grey Man; Gríðr; Griffon; Grigori; Grigs; Grimalkin; Grindylow; Groac'h Vor; Groac'h; Grootslang; Grýla and Leppalúði; Guahaioque; Guajona; Gualicho; Guang yi ji; Guardian Angel; Guayota; Gudrun; Guerrionets; Guhyaka; Guivre; Gulon; Gumberoo; Gunungsin; Gurangatch; Guriuz; Gurumāpā; Gusainji Maharaj; Gütel; Guter Johann; Gwagged Annwn; Gwarchells; Gwaryn-a-Throt; Gwazig-Gan; Gwisin; Gwragedd Annwn; Gwrgi Garwlwyd; Gwyllgi; Gwyllion; Gwyn ap Nudd; Gyalpo spirits; Gytrash;

Haaf-Fish; Haagenti; Haakapainiži; Habetrot; Hábrók; Hadas; Hadhayosh; Haesindang Park; Hafgufa; Hag and Mag; Hagoromo (swan maiden play); Hags; Hāhau-whenua; Haietlik; Hainuwele; Hairen; Haizum; Häkelmänner; Hakenmann; Hākuturi; Hakuzōsu; Halahala; Half-elf; Haliurunas; Halizones; Halphas (demon); Haltija; Ham; Hamadryad; Hamingja; Hammaspeikko; Hamsa; Hanako-san; Hanau epe; Hanbi; Hanitu; Hannya; Hans von Trotha; Hantu Air; Hantu Bongkok; Hantu Raya; Hantu Tinggi; Hantu; Haoma; Haosi Namoinu; Härdmandlene; Hare of Inaba; Harionagu; Harpy; Haryashvas and Shabalashvas; Hashihime; Hassan of Basra; Hati Hróðvitnisson; Hatif; Hatsadiling; Hatuibwari; Haugbui; Hausbock; Havfrue; Havmand; Hawakai; Hayagriva; Hayk; Haymon (giant); Hayyot; Headless Horseman; Headless Mule; Hecatoncheires; Ḫedammu; Heerwische; He-He Er Xian; Heidenmanndli; Heidenweibchen; Heikegani; Heikki Lunta; Heimchen; Heinrich von Winkelried; Heinzelmann; Heinzelmännchen; Heinzlin; Hejkadlo; Helhest; Hell Courtesan; Hellhound; Hellmouth; Helloi; Hellusians; Hemā; Hemann; He-Mann; He-Männer; Hemaraj; Hé-no; Henwen; Hercinia; Herdweibchen; Herensuge; Hermaphroditus; Herne the Hunter; Heruka; Hervör alvitr; Hesperides; Hevajra; Hey-Hey Men; Heyoka; Hibagon; Hidden Folk; Hidebehind; Hiderigami; Hidimba; Hieracosphinx; Hiisi; Hildr; Hillbilly Beast of Kentucky; Hille Bingels; Hillmen; Himiko; Hine-nui-te-pō; Hingchabi; Hinn; Hinzelmann; Hippalectryon; Hippe; Hippocampus; Hippogriff; Hippolyta; Hippopodes; Hira; Hiranyakashipu; Hiranyaksha; Hircocervus; Hitodama; Hito-gitsune; Hitotsume-kozō; Hitotsume-nyūdō; Hitte-Hatte; Hittite Goddesses of Fate; Hlaðguðr svanhvít; Hljod; Hlökk; Hồ ly tinh; Hob; Hob-and-his-Lanthorn; Hobbididance; Hobbit; Hob-Gob; Hobgoblin - Hobgoblins; Hob-Thrush Hob; Hodag; Hödekin; Hoihoimann; Holawaka; Holly King and Oak King; Homados; Hombre Gato; Home dels nassos; Homme de Bouc; Hommes Cornus; Homunculus - Homunculi; Honduran Creatures; Hone-onna; Honey Island Swamp Monster; Hong; Hongatar; Hooded Spirits; Hoop Snake; Hooters; Hopfenhütel; Horae; Horned Serpent; Hortdan; Hotoke; Houggä-Ma; Houles fairies; Houpoux; Houri; Hòutǔ; Hoyau; Hræsvelgr; Hrímgerðr; Hrímgrímnir; Hroðr; Hrymr; Hsigo; Hú; Hüamann; Huay Chivo; Huckepoten; Hudson River Monster; Hufaidh; Hugag; Hulde Folk; Hulder; Huldre Folk; Huldufólk; Hulte; Huma bird; Humbaba; Humli; Hun and po; Hundun; Hungry Ghost; Huodou; Hupia; Hurricane children; Husbuk; Hütchen; Hutzelmann; Húxiān; Hyades; Hyakki Tsurezure Bukuro; Hyakki Yagyō_Wild Hunt; Hybris; Hydra; Hydrus; Hyldeqvind; Hylonome; Hyōsube; Hyottoko; Hypnalis; Hyrrokkin; Hyter Sprites;

I Verbti_Albanian_Deity; Iaculi; Iannic-ann-ôd; Iara; Ibaraki-dōji; Iblis; Ibo loa; Ibong Adarna; Ice Mannikins; Ice Queen; Ichchadhari naag; Ichneumon; Ichthyocentaur; Ichthyophagoi; Iði; Idis; Idlirvirissong; Idris Gawr; Iele; Ifrit; Igigi; Ignis Fatuus; Igopogo; Ijiraq; Ikiryō; Iktomi; Ikuchi; Iku-Turso; Ila (Samoan myth); Ila; Ilargi; Ilavida; Ileana Cosânzeana; Iliamna Lake Monster; Illuyanka; Ilomba; Ilvala and Vatapi (asura); Ím (joetunn); Imbunche; Immram; Imp; İn Cin; Inapertwa; Inari Ōkami; Incubus; Indruk; Indus worm; Inguma; Inkanyamba; Inmyeonjo; Intulo; Inugami Gyōbu; Inugami; Ioke; Iphis; Iphito; Ipilja-ipilja; Ipos; Ipotane; Iratxo - Iratxoak; Iravati; Irish Mythic Creatures; Iroquois Myths; Irrbloss; Irrlichter; Irrwurz; Irshi; Isfet; Ishim; Ishinagenjo; Isitwalancenge; Iskrzycki; Islam Mythic Creatures; Isonade; Ispolin; Issie; Issitoq; Issun-boushi; Itbarak; Itsumade; Ittan-momen; Iubdan; Iya; İye;

Jack and the Beanstalk; Jack Frost; Jack in the Green; Jack o' Kent; Jack o' Legs; Jack o' the bowl; Jack o'Lanthorn; Jack the Giant Killer; Jackalope; Jack-In-Irons; Jacques St. Germain; Jaculus; Jahi; Jahnu; Janjanbi; Jann; Japanese Serpent; Jarita; Járnsaxa; Jashtesmé; Jasy Jatere; Jean de la Bolieta; Jean de l'Ours; Jeannot; Jenglot; Jengu; Jenny Haniver; Jentil; Jenu; Jersey Devil; Jetins; Jezinky; Jiangshi; Jiaolung; Jihaguk daejeok toechi seolhwa; Jikininki; Jimmy Squarefoot; Jin Chan; Jinmenju; Jinmenken; Jinn; Jinnalaluo; Jipijka'm; Jiutian Xuannü; Jiutou Zhiji Jing; Jiuweihu; Joan the Wad; Joan-in-the-Wad; Jogah; Joint Snake; Joint-eater; Jok; Jolabukkar; Jonathan Moulton; Jormungandr; Jörmungandr; Jorōgumo; Jötunn; Jubokko; Jüdel; Judys; Jué yuán; Jueyuan; Juggernaut; Julbuk; Jumbee; Jvarasura; Jwalamalini;

Kabhanda; Kabouter; Káchabuké; Kachina; Kae and Longopoa; Ka-Ha-Si; Kaibyō; Kai-n-Tiku-Aba; Kakawin; Kālakeya - Kālakeyas; Kalamainu'u; Kalanemi (asura); Kalanemi (Ramayana); Kalanoro; Kâ'lanû Ahkyeli'skï; Kalaviṅka; Kalenjin Mythic Creatures; Kalevipoeg; Kaliya; Kallana; Kallikantzaros- Kallikantzaroi; Kallone; Kållråden; Kamadhenu; Kamaitachi; Kamakhya; Kami; Kamikiri; Kammapa; Kangiten; Kanglā Shā; Kao; Kappa; Kapre; Karapandža; Karkadann; Karlá; Karnabo; Karura; Karzełek; Kasa-obake; Käsermänner; Kasha; Kasogonagá; Katajatar; Kataw; Katie Woodencloak; Kaukas; Kaupe; Kawas; Kawauso; Kayeri; Kechibi; Kee-wakw; Keibu Keioiba; Ķekatnieki; Ke'le - Ke'let; Kelpie; Kenas-unarpe; Keneō (oni); Keong Emas; Kepetz; Keres; Kerions; Ketu; Keukegen; Khalkotauroi; Khoirentak tiger; Khongjomnubi Nonggarol; Khyāh; Kichkandi; Kidōmaru; Kielkropf; Kigatilik; Kihawahine; Kijimuna; Kijo (folklore); Kikimora; Kikituk; Kilili; Killcrops; Kilmoulis; Kimaris; Kimpurushas; King Father of the East; King Goldemar; King Kojata; King Laurin; Kings of Alba Longa; Kinie Ger; Kinnara; Kinoko; Kirin; Kirkonwäki; Kirmira; Kirtimukha; Kishi; Kitchen God; Kitsune no yomeiri; Kitsune; Kitsunebi; Kit-with-the-Canstick; Kiwa; Kiyohime; Klabautermann; Klagmuhme; Klaubauf; Klaubautermann; Klopferle; Knecht Ruprecht; Knight of the Swan; Knights of Ålleberg; Knocker; Knockerlings; Knocky Boh; Knucker; Koalemos; Koan Kroach; Kobalos; Kobold; Kodama; Kōga Saburō; Koka and Vikoka; Kokabiel; Kokopelli; Komono; Konaki-jiji; Kong Koi; Konjaku Gazu Zoku Hyakki; Konjaku Hyakki Shūi; Konpira Gongen; Konrul; Koolakamba; Kopala; Korandon; Korbolko; Korean dragon; Korean Virgin Ghost; Kormos; Kornbock; Kornikaned; Korn-Kater; Koromodako; Korpokkur; Korred; Korrigan; Korrigans; Korriks; Korrs; Koshchei; Kostroma; Kotavi; Kotobuki; Koto-furunushi; Kouricans; Kourils; Koutsodaimonas; Kōya Hijiri; Krabat; Krachai; Krahang; Kraken; Krampus; Krasnoludek; Krasue; Krat; Kratt; Kratu; Kroni; Krosnyata; Krun; Kṣitigarbha; Kting voar; Kuafu; Kubera; Kubikajiri; Kuchisake-onna; Kudagitsune; Kudan; Kudukh; Kui; Kujata; Kukeri; Kukudh; Kukulkan; Kukwes; Kuli-ana; Kulilu; Kulshedra; Kulullû; Kumakatok; Kuman Thong; Kumbhakarna; Kumbhāṇḍa; Kumi Lizard; Kumiho; Kuṇḍali; Kuntilanak; Kupua; Kurangaituku; Kuraokami (ryu); Kurents; Kurma; Kuro-shima (Ehime); Kurozuka; Kurupi; Kusarikku; Kushiel; Kushtaka; Kutkh; Kuttichathan; Kuzenbo; Kuzunoha; Kuzuryū; Kyanakwe; Kydoimos; Kymopoleia; Kyrkogrimm;

La Bolefuego; La Diablesse; La Encantada; La Guita Xica; La Llorona; La mula herrada; La Sayona; Labbu; Lạc bird; Lachesis; Laddy Midday; Ladon; Lady Featherflight; Laelaps; Laestrygonians; Lagahoo; Lagarfljótsormur; Lahamu; Lai Khutshangbi; Lailah_female_angel_Judaism; Laima; Lajjā Gaurī; Lakanica; Lake Monster; Lake Tianchi Monster; Lake Van Monster; Lake Worth Monster; Lākhey; Lamashtu; Lambton Worm; Lamia; Lamignak; Lampades; Lampago; Lampedo; Lampetho; Lampetia; Landdisir; Landlord Deities; Landvættir; Lang Bobi Suzi; Lang Suir; Lange Wapper; Langsuyar; Lantern Man; Lapiths; Lares Familiares; Lares; Lariosauro; Lauma; Laúru; Lava bear; Lavellan; Lazavik; Lazy Laurence; Le Criard; Le Patre; Le Rudge-Pula; Lebraude; Legendary Horses in the Jura; Legendary Horses of Pas-de-Calais; Legion (demons); Leikn; Leimakid; Leipreachán; Leleges; Lemminkäinen; Lempo; Lemures; Leonard (demon); Leontophone; Leprechaun; Lepus cornutus; Leraje; Les Lavandières; Lešni Mužove; Lešni Pany; Letiche; Leuce; Leucippus; Leviathan; Leyak; Lhiannan-Sidhe; L'Homme Velu; Liban; Lidérc; Lidercz; lietonis; Lietuvēns; Lightning Bird; Likho; Likhoradka; Lilin; Lilith; Lilu; Limnad; Limniades; Limos; Lindwurm; Lip (Moerae); Lisunki; Little Butterflies; Little Darlings; Little People of the Pryor Mountains; Little People; Little Wildrose; Living Puppet - Doll; Lizard Fairy; Lizard Man of Scape Ore Swamp; Ljósálfar; Ljubi; Llamhigyn Y Dwr; Loch Ness Monster; Löfviska; Lohjungfern; Lord Nann; Lord of the Forest; Lord of the Mountains; Lorelei; Lorggen; Lörggen; Losi; Lotan; Lou Carcolh; Loumerottes; Loveland Frog; Loys Ape; Luan; Lubberfiend; Luchtenmannekens; Lucifer; Lucius Tiberies (vs King Arthur); Luduan; Ludwig the Bloodsucker; Lugal-irra; Lugat; Luison; Lukwata; Lulal; Lundjungfrur; Lung; Lungma; Lungmu; Lupeux; Lurican; Lurigadaun; Lurikeen; Lusca; Lutin; Lutins Noirs; Lutzelfrau; Luwr; Ly Erg; Lyeshi; Lygte Men; Lyktgubbe; Lyncetti; Lyngbakr; Lynx; Lysgubbar; Lysippe;

Maa-alused; Maalik; Maanväki; Macaria; Macelo (Telchine); Machlyes; Maćić; Maciew; Macinghe; Macrobian; Mada; Madam Koi Koi; Madhu-Kaitabha; Madhusudana; Madre de aguas; Mae Nak Phra Khanong; Mae yanang; Mãe-do-Ouro; Maelor Gawr; Maemaeler; Maenad (wiki); Maenad; Maere; Maero; Maggy Moulach; Magog; Magpie Bridge; Magu; Maha Sona; Mahabali; Mahakala; Mahamayuri; Maharajikas; Mahishasura; Mahjas Kungs; Mahoraga; Mahound; Maighdean Mara; Mairu; Majlis al Jinn; Makara; Makuragaeshi; Malahas; Malay Creatures; Malay ghosts; Malicious Spirits; Malienitza; Malingee; Malkus; Malo (saint); Malphas (demon); Mama D'Leau; Mamalić; Mami Wata; Mammon; Mamucca; Mamuni Mayan; Manaia; Manananggal; Manannán mac Lir; Manasa_Snake_Goddess; Mānasaputra; Manaul; Mande Barung; Mandi; Mandragora; Mandrake; Mandurugo; Maneki-neko; Manes; Maní; Maṇibhadra; Manipogo; Manjushrikirti; Mannegishi; Manohara; Manseren Manggoendi; Mantellioni; Manticore; Manussiha; Maori ghosts; Mapinguari; Mara Daoine; Mara; Mara_Goddess; Mara_Goddess2; Marabbecca; Marantule; Maratega; Mara-Warra; March Malaen; Marchosias; Mare; Mares of Diomedes; Margot the fairy; Margot-la-Fée; Mari Lwyd; Maricha; Marid; Markopolen; Marmennill; Marpesia; Marraco; Martes; Martlet; Marțolea; Maruda; Marui; Mary Lakeland (accused witch); Maryland Goatman; Masovian dragon; Massarioli; Mastema; Master Hammerlings; Master Johannes; Matagot; Matarajin; Matres and Matronae; Matsieng; Matsya; Matuku-tangotango; Maushop; Mavka; Maxios; Mayasura; Mazapegolo; Mazapégul; Mazoku; Mazomba; Mazzamarelle; Mazzamerieddu; Mazzikin; Mbói Tu'ĩ; Mbombo; Mbuti Mythic Creatures; Mbwiri; Medjed; Medusa; Meduza; Meerminnen; Meerweiber; Megijima; Mehen_Board_Game_Snake_God_Egypt; Meilichios; Meitei dragons; Meitei Mythic Creatures; Melanippe; Melch Dick; Meliae; Melinoë; Melisseus; Melon-heads; Melusine; Memegwaans; Memphre; Menehune; Menippe; Menk; Menninkäinen; Menoetius; Menreiki; Menshen; Mephistopheles; Meretseger; Mermaid (wiki); Mermaid of Warsaw; Mermaid of Zennor; Mermaid; Merman; Merrow; Merrows; Merry Dancers; Merwomen; Meryons; Mestra; Metten; Mfinda; Mhachkay; Miage-nyūdō; Michigan Dogman; Mikaribaba; Mikoshi-nyūdō; Milton lizard; Mimas (gigantes); Mimis; Min Min light; Minairó; Minawara and Multultu; Minhocão; Minka Bird; Minoan Genius; Minokawa; Minotaur; Minthe; Mintuci; Minyans; Miodrag; Miri; Miru; Misaki; Mishaguji; Mishihase; Mishipeshu; Misizla; Mixtecatl; Mizuchi; Mo; Moan; Mob (Sleigh Beggey); Moddey Dhoo; Móðguðr; Moehau; Moestre Yan; Mogollon Monster; Mögþrasir; Mogwai; Mohan; Moine Trompeur; Moirai; Moires; Mokele-mbembe; Mokoi; Mokumokuren; Moloch; Molpadia; Momiji; Momo the Monster; Momotarō; Momu; Monachetto; Monachicchio; Monaciello - Monacielli; Moñái; Mongfind; Mongolian Death Worm; Monkey-man of New Delhi; Mono Grande; Monoceros (wiki); Monoceros; Monoloke; Mononoke; Monopod; Monster of Lake Fagua; Monster of Lake Tota; Monyohe; Moʻo; Mooinjer Veggey; Moon Rabbit; Moon-eyed people; Mora; Morag; Morax (demon); Morgan le Fay; Morgans; Morgawr; Morgen; Mormo; Moroi; Moros; Morvarc'h; Moryana; Mōryō; Mo-sin-a; Moso's Footprint; Moss People; Moswyfjes; Mother's Blessing; Mothman; Mound Folk; Mountain God; Mountain Monks; Mouros; Mrenh kongveal; Mṛtyu; Mu shuvuu; Muan; Mucalinda; Muckie; Muc-sheilch; Mudjekeewis; Muelona; Mug Ruith; Muiraquitã; Mujina; Mukasura; Muki; Mukīl rēš lemutti; Muladona; Muldjewangk; Mullo; Muma Pădurii; Mummy - Mummies; Mungoon-Gali; Munkar and Nakir; Munshin; Munsin; Murkatta; Muroni; Muscaliet; Muse; Mušḫuššu; Musimon; Mušmaḫḫū; Mussie; Mützchen; Muut; Muyingwa; Myling; Myōbu; Myrina; Myrmecoleon; Myrmekes; Myrmidon; Myrmidons; Myrto; Mytilene;

Naamah; Naberius (demon); Nabhi; Nachtkrapp; Nachtmännle; Nachtmart; Nachzehrer; Näcken; Nadi astrology; Nafnaþulur; Naga fireballs; Naga people; Naga; Nagaraja; Nagual; Nahuelito; Naiad - Naiads; Naimiṣāraṇya; Naimon; Nain Rouge; Näkku; Nale Ba; Namahage; Namazu; Namtar; Namu doryeong; Nanabozho; Nandi Bear; Nandi; Nang Mai; Nang Ta-khian; Nang Tani; Nanny Rutt; Nanook; Napfhans; Nār as samūm; Narakasura; Narantaka-Devantaka; Narasimha; Nargun; Nariphon; Nasnas; Nasu; Nat; Nataska; Native Fairies; Natrou-Monsieur; Nav; Navagunjara; Nawao; Nawarupa; Neades; Necker; Neckers; Necks; Negafook; Negret; Nei Tituaabine; Nekomata; Nel; Nelly Longarms; Nemean Lion; Nemty; Nëna e Vatrës; Nephele; Nephilim; Nereides; Nereids; Nessus; New Jersey folktales; Nganaoa; Ngariman; Ngen; Nghê; Nguruvilu; Niägruisar; Niamh; Nian; Nickel; Nick-Nocker; Nicnevin; Níðhöggr; Night Folk; Night Hag; Nightmarchers; Nightmare; Nikkisen; Nikkur; Nillekma; Nimble Men; Nimerigar; Nimue; Nine Diseases; Nine-headed bird; Ningen; Ningyo; Ninimma; Ninki Nanka; Ninlaret; Ninurta; Niō; Nion Nelou; Nip the Napper; Nis Puck; Nisken; Nisroch; Niß Puck; Nisse; Nissen god Dreng; Nittaewo; Nitus; Nivatakavacha; Nixen; Nixie; Nixies; Nkisi; Nkondi; Nocnitsa; Noderabō; Nökke; Nommo; Nomos; Nongshaba; Nongshāba; Noon Woman; Noonday Demon; Nootaikok; Noppera-bō; Norea_burn_Noah's_ark; Norgen; Norggen; Nörglein; Nörke; Nörkele; Norns; Norse_Nude_Snake_Witch; North Shore Monster; Nose (Moerae); Nosferatu (word); Nótt; Nouloi; Nüba; Nuberu; Nuckelavee; Nue; Nuggle; Nuku-mai-tore; Nuli; Nuloi; Nûñnë'hï; Nuno sa punso; Nun'Yunu'Wi; Nuppeppō; Nurarihyon; Nure-onna; Nuribotoke; Nurikabe; Nuu-chah-nulth mythology; Nuuttipukki; Nüwa; Nyami Nyami; Nyi Roro Kidul; Nykken; Nymph; Nyūdō-bōzu;

O Tokata; Oaraunle; Obambou; Obayifo; Oberon; Obia; Oboroguruma; Oceanids; Ochimusha; Ochokochi; Odei; Odin; Odontotyrannus; Odziozo; Og; Ogoh-ogoh; Ogopogo; Ogre; Ogun; Oilliphéist; Ojáncanu; Okeus; Oksoko; Ōkubi; Okuri-inu; Old Scratch; Olentzero; Ōmukade; Onchú; One with the White Hand; Ongon; Oni Gozen; Oni; Onibi; Onihitokuchi; Onikuma; Onmyōji; Onnerbänkissen; Onocentaur; Onryō; Ōnyūdō; Onza; Ootakemaru; Oozlum Bird; Ophanim; Ophiotaurus; Ora; Orang bunian; Orang Mawas; Orang Minyak; Orang Pendek; Orchi; Orculi; Orculli; Orcus; Ördög; Oreades; Oreads; Örek; Orgoglio; Orias; Orion; Orithyia; Ork; Orko; Orobas; Orochi; Orphan Bird; Orthrus; Ortnit; Osakabehime; Osaki; Ose; Oshun; Ossetian Myth; Otomitl; Otoroshi; Otrera; Otso; Otterbahnkin; Oukami; Ouni; Ouroborous; Ouroubou; Ovinnik; Owd Lad; Owlman; Oxions; Oxylus; Ozark Howler;

Paasselkä devils; Pahlavas; Pahuanui; Paimon; Painajainen; Pakhangba; Pākhangbā; Palioxis; Pallas (gigantes); Pallas; Palm Tree King; Pamarindo; Pamola; Pan; Panchajanya; Panchamukha; Pandafeche; Pandi; Panes; Pangu; Panhu; Pania of the Reef; Panlung; Panotti; Pantariste; Pantegane; Pantegani; Pantheon_the_creature; Panther; Panti'; Paoro; Papa Bois; Papinijuwari; Para; Paraskeva Friday; Parcae (Moerae); Parcae; Pard; Parzae (Moerae); Patagon; Patagonian Giant; Patasola; Patung; Patupaiarehe; Pavaró; Pazuzu; Peacock Princess; Pech; Pechmanderln; Peg Powler; Pegaeae; Pegasus; Peleiades; Pelesit; Peluda; Penanggalan; Penemue; Penette; Peng; Penghou; Penhill Giant; Penthesilea; People of Peace (Sìth); People of Peace; Perchta; Père Fouettard; Perëndi; Pereplut; Peri; Perria; Persephone; Persévay; Peryton; Pesanta; Petermännchen; Petit Jeannot; Petty Fairie; Phaethusa; Phantom Cats; Phantome (Trinidad, Tobago, Guyana); Phenex; Phi phong; Phi Tai Hong; Philippine Mytic Creatures; Philotes; Phisuea Samut; Phobetor; Phoebe; Phoenix; Pholus; Phooka; Phorcys; Phthisis; Piasa; Pichal Peri; Picolaton; Picolous; Pictish Beast; Pier Gerlofs Donia; Pig Dragon; Pillan; Pillywiggin; Pillywiggins; Pilwiz; Pincoy; Pincoya; Pingel; Pipa Jing; Pippalada; Piru; Pishachas; Pishtaco; Piskies; Pitr; Pitsen; Pitzln; Piuchén; Pixie; Pixies; Pixiu; Płanetnik; Pleiades (wiki); Pleiades; Plusso; Pocong; Polemos; Polemusa; Polevik; Poleviki; Polik-anna; Polkan; Polong; Poltergeist; Poludnitsy; Polybotes (gigantes); Polydora; Pombero; Pomo religion; Ponaturi; Pop (ghost); Pope Lick Monster; Popobawa; Poppele; Poroniec; Portunes; Potamides; Pouākai; Poubi Lai; Poulpikans; Povoduji; Powries; Prahlada; Pratyangira; Preinscheuhen; Prende_Albanian_Deity; Preta; Pricolici; Princess Eréndira; Proctor Valley Monster; Proioxis; Pronomus; Propoetides; Proteus; Proto-Indo-European Myth; Protoplast; Psoglav; Psotnik; Psychai; Psychopomp; Pua Tu Tahi; Púca; Puck; Puck_Shakespeare; Pueblo clown; Pugot; Pukwudgie; Pulao; Pulgasari; Puloman; Pulter Klaes; Pumphut; Pundacciú; Purzinigele; Puschkait; Putana; Putri Tangguk; Putti; Putto; Putzen; Puu-Halijad; Pvitrulya; Pyewacket (familiar spirit); Pygmies; Pyinsarupa; Pyrausta; Pysslinger-Folk; Python;

Qallupilluit; Qamulek; Qarakorshaq; Qareen; Qianlima; Qilin; Qin (Mandaeism); Qingji; Qingniao; Qippoz; Qiqirn; Qitmir; Qiulung; Qlippoth; Quaeldrytterinde; Queen Mab; Queen Maeve; Queen Mother of the West; Queen of Elfland; Queen of Elphame; Queen of Sirens; Queensland tiger; Querquetulanae; Querxe; Quetzalcoatl; Quiet Folk; Quimbanda; Quinametzin; Quinotaur; Qʼuqʼumatz; Q'ursha; Qutrub;

Rå; Rabisu; Rådande; Rāgarāja; Rahab; Raijin; Raijū; Railroad Bill; Rain Bird; Rainbow Crow; Rainbow Serpent; Rakhsh; Rākshasas; Rakshaza; Rakta Yamari; Raktabīja; Ramidreju; Rangalau Kiulu Phantom; Rannamaari; Rantas; Rarash; Raróg; Rashōmon no oni; Rasselbock; Ratatoskr; Raum; Ravana; Reconstructed Word - Dʰéǵʰōm; Red Cap; Red Ghost; Red Lady; Redcap; Redcombs; Re'em; Reeri Yakseya; Reikon; Remora; Rephaite; Reptilian; Resurrection Mary; Revenant; Reynard; Rhagana; Rhiwallon; Rishabhanatha; Rishyasringa; River Men; River Women; Roane; Robin Goodfellow; Robin Round Cap; Robot; Roc; Rododesa; Roggenmuhme; Rogo-Tumu-Here; Rojenice; Rōjinbi; Rokita; Rokkaku-dō; Rokurokubi; Ro-langs; Romãozinho; Rompo; Rồng - Vietnamese Dragons; Ronove; Root race (theosophy); Rôpenkerl; Rougarou; Roughby; Rozhanitsy, Narecnitsy and Sudzhenitsy; Rübezahl; Rüdiger von Bechelaren; Ruha; Rukh; Rukmavati; Rumpelstiltskin; Ruohtta; Rusalka - Rusalky; Russian superstitions; Ryong; Ryū; Ryūgū-jō; Ryūjin;

Saci; Sack Man; Sadhbh; Sæhrímnir; Sagol kāngjei; Saint Amaro; Saint Nedelya; Sakabashira; Salabhanjika; Salamander; Salbanelli; Salmon of Knowledge; Salvanel - Salvanelli; Salvani; Samael; Samagana; Samaton; Samca; Samebito; Samodiva; Samovila - Samovily; Sampati; Samsin Halmeoni; Samyaza (wiki); Samyaza; San Martin Txiki; Sandman; Sankai; Sanshi; Santa Compaña; Sântoaderi; Sânziană; Sarama; Sarangay; Sarimanok; Sárkány; Sarpa Kavu; Sarutahiko Ōkami; Sarván; Satan; Satanachia; Satori; Satyr; Satyress; Satyrus; Sauvageons; Savali; Sayona; Sazae-oni; Sazakan; Scáthach; Scazzamurieddu; Schacht-Zwerge; Schlorchel; Schneefräulein; Schrat; Schrätteli; Schrecksele; Sciritae; Scitalis; Scorpion men; Screaming skull; Scylla; Scythian genealogical myth; Scythian religion; Scythians; Se’īrīm; Sea goat; Sea Mither; Sea Monk; Sea Monster; Sea Serpent; Sea-Griffin; Sea-Lion; Sebile; Seefräulein (Gwagged Annwn); See-Hear-Speak No Evil; Seelie; Seelkee; Selige Fräulein; Selkie; Selkolla; Selma; Semystra; Sengann; Seonaidh; Seonangshin; Seonangsin; Seps; Seraphim; Seri Gumum Dragon; Seri Pahang; Serpopard; Serván; Servant (Serván); Sessho-seki; Set animal; Setsubun; Seven-headed serpent; Sewer alligator; Sha Wujing; Shabrang; Shachihoko; Shade; Shadhavar; Shadow Person; Shahbaz; Shahmaran; Shahrokh; Sha'ir; Shaitan; Shambara; Shango; Shangyang; Shankha; Shapeshifter; Shapishico; Sharabha; Sharlie; Shatans; Shatarupa; Shdum; She-camel of God; Shedim; Sheela na Gig; Sheka; Shellycoat; Shen; Shen_clam_monster; Shenlung; Shesha; Sheshe; Shetani; Shi Dog; Shibaemon-tanuki; Shichinin misaki; Shidaidaka; Shikhandi; Shikigami; Shikome; Shinigami; Shiranui; Shirime; Shiryō; Shishiga; Shishimora; Shōjō; Shōkera; Shopiltee; Shtojzovalle; Shtriga; Shubin; Shug Monkey; Shuihu; Shuimu; Shukra; Shurali; Shurdh; Shuten-dōji; Sibille; Sidehill Gouger; Sidhe; Sigbin; Signifying monkey; Sihirtia; Sihuanaba; Sila; Sileni; Silenus; Silvane; Silvani; Silvanus; Simargl; Simbi; Simhamukha; Simonside Dwarfs; Simurgh; Sina and the Eel; Singa; Sinoe; Sin-you; Siproeta; Siren; Sirena chilota; Sirena; Sirin; Sisimoto; Sisiutl; Si-Te-Cah; Sìth; Sithchean; Sithon; Six-headed Wild Ram; Siyokoy; Sjörå; Skeleton; Skin-walker; Skogsjungfru; Skogsnufvar; Skogsrå; Skogsråt; Sköll; Skookum; Skougman; Skovmann; Skrat; Skrzak; Skuld (half-elf princess); Skulld; Skunk Ape; Skvader; Sky Fox; Slattenpatte; Slavic Fairies of Fate; Slavic Mythic Creatures; Slavic Pseudo-deities; Slavic Water Spirit; Sleigh Beggey; Sleipnir; Sluagh; Smallpox demon; Smilax; Snake_Worship; Snallygaster; Snipe Hunt; Snow Lion; Snow Queen; Snow Snake; Sockburn Worm; Söedouen; Söetrolde; Soeurettes; Sōjōbō; Solomonari; Solomon's shamir; Soltrait; Somali myth; Sooterkin; Sorei; Sosamsin; Soter; Soteria; Sotret; Soucouyant; Souffle; Soul Components_Finnic Paganism; Sovereignty goddess; Spearfinger; Spey-wife; Sphinx; Spiriduș; Spirit spouse; Spirit Turtle; Spirits; Splintercat; Spor; Spriggan - Spriggans; Springheeled Jack; Sprite - Sprites; Spunkies; Squasc; Squonk; Srbinda; Sreng; St. Elmo's Fire; Stallo; Stendel; Stheno and Euryale; Stihi; Stoicheioi; Stone Sentinel Maze; Stoor worm; Storsjöodjuret; Strashila; Straszyldlo; Straw Bear; Stricha; Strigoi; Strix; Stroke Lad; Strömkarl; Struthopodes; Strzyga; Stuhać; Stymphalian birds; Su iyesi; Suanggi; Suangi; Subahu; Succarath; Succubus; Sudsakorn; Sumarr and Vetr; Sumascazzo; Sunda and Upasunda; Sundel bolong; Sunekosuri; Suparṇākhyāna; Surgat; Surtr; Susulu; Sut; Suvannamaccha; Suzuka Gozen; Svaðilfari; Svartálfar; Swan Maiden; Sweet William's Ghost; Swetylko; Sybaris; Sylph; Syöjätär; Syrbotae;

Ta'ai; Tahoe Tessie; Tailypo; Takam; Takaonna; Takarabune; Talamaur; Talos; Tam Lin; Tamamo-no-Mae; Tamangori; Tamil myth; Tan Noz; Tanabata; Tandava; Tangaroa; Tangie; Tangye; Tanin'iver; Taniwha; Tannin; Taoroinai; Taotao Mo'na; Taotie; Tapairu; Tapio; Tapire-iauara; Tarand; Tarasque; Taraxippus; Tariaksuq; Tarrasque; Tartalo; Tartaruchi; Tata Duende; Tatzelwurm; Taweret; Tawûsî Melek; Te Wheke-a-Muturangi; Teakettler; Tecmessa; Teju Jagua; Teka-her; Teke Teke; Tek-ko-kui; Telchines; Teleboans; Telemus; Ten Giant Warriors; Teng; Tenghuang; Tengu; Tenka; Tennin; Tenome; Ten-ten vilu; Tentōki and Ryūtōki; Tepegöz; Tepēyōllōtl; Teraphim; Termagant; Terrible Monster; Tesso; Tethra; Teumessian fox; Teutobochus; Teuz; Teyolía; Thalestris; Tharaka; Thardid Jimbo; Thayé; The Beast of the Earth; The Beast; The Black Dog of Newgate; The Cu Bird; The Devil Whale; The Elder Mother; The Elf Maiden; The Four Winds; The Giant Who Had No Heart in His Body; The Goose Wife; The Governor of Nanke; The Great Snake; The Green Man of Knowledge; The Heavenly Maiden and the Woodcutter; The Hedley Kow; The Imp Prince; The King of the Cats; The Laidly Worm of Spindleston Heugh; The Legend of Ero of Armenteira; The Lovers; The Mistress of Copper Mountain; The Morrígan; The Nine Peahens and the Golden Apples; The Nixie of the Mill-Pond; The Painted Skin; The Precious Scroll of the Immortal Maiden Equal to Heaven; The Prince Who Wanted to See the World; The Queen of Elfan's Nourice; The Sea Tsar and Vasilisa the Wise; The Silbón; The sixteen dreams of King Pasenadi; The Stinking Corpse (giant); The Swan Queen; The Voyage of Bran; The Voyage of Máel Dúin; The Voyage of the Uí Chorra; The Witch of Saratoga; The Woman of the Chatti; Theli (dragon); Theomachy; Theow; Thermodosa; Thetis Lake Monster; Thiasos; Thiasus; Thinan-malkia; Thiota; Thoe; Thomas Boudic; Þorbjörg lítilvölva; Þorgerðr Hölgabrúðr and Irpa; Thrasos; Three Witches; Three-legged crow; Thriae; Þrívaldi; Throne; Thrones; Thumblings; Thunderbird; Thunderdell; Þuríðr Sundafyllir; Thusser; Thyrsus (giant); Tiamat; Tianguo; Tianlung; Tianma; Tibetan myth; Tibicena; Tiddalik; Tiddy Mun; Tiddy Ones; Tigmamanukan; Tiʻitiʻi; Tikbalang; Tikokura; Tikoloshe; Tilberi; Tilla; Tinirau and Kae; Tinirau; Tintilinić; Tipua; Titania; Titanis; Titans; Titivillus; Tityos; Tiyanak; Tizheruk; Tjilpa; Tlachtga; Tlahuelpuchi; Tlanchana; Toell the Great; Tōfu-kozō; Toggeli; Toho (kachina); Tom Hickathrift; Tomtevätte; Tom-Tit; Tomtrå; Tontuu; Tooth Fairy; Topielec; Torngarsuk; Toyol; Toyotama-hime; Tragopodes; Trahlyta; Trailokyavijaya; Transformer; Trasgo; Trauco; Tree Elves; Tree Octopus; Tree of Jiva and Atman; Trenti; Trentren Vilu and Caicai Vilu; Tréo-Fall; Trickster - Tricksters; Triple-headed eagle; Tripurasura; Trishira; Triteia; Triton; Tritopatores; Troglodytae; Trois Marks (Moerae); Trojan Leaders; Trojan War characters; Troll Cat; Troll; Trow; Tsmok; Tsuchigumo; Tsuchinoko; Tsukumogami; Tsukuyomi-no-Mikoto; Tsul 'Kalu; Tsurara-onna; Tsuru no Ongaeshi; Tsurubebi; Tsurube-otoshi; Tuatha dé Danaan; Tuatha; Tubo; Tuchulcha; Tudigong; Tu'er Shen; Tugarin; Tulevieja; Tulpa; Tulpar; Tumburu; Tunda; Tuometar; Tupilaq; Tur; Turoń; Türst; Turtle Lake Monster; Turul; Tuttle Bottoms Monster; Tutyr; Tuyul; Two-Toed Tom; Twrch Trwyth; Tyger; Tylwyth Teg; Typhon; Tzitzimitl;

Ubagabi; Ubume; Ucchusma; Uchchaihshravas; Uchchaishravas; Uchek Langmeitong; Udug; UFO; Ugallu; Uhaml; Uhlakanyana; Ullikummi; Ulmecatl; Ulupi; Umamba; Umang Lai; Umi zatō; Umibōzu; Umū dabrūtu; Unclean Force; Unclean Spirit; Undine; Undines; Ungaikyō; Ungnyeo; Unhcegila; Unicorn; Unners-Boes-Thi; Unterengadin; Untüeg; Untunktahe; Unut_Egypt_Rabbit-Snake-Lion_Goddess; Upamanyu; Upelluri; Upiór; Ur; Uraeus; Urayuli; Ureongi gaksi; Uriaș; Uridimmu; Urisk; Urmahlullu; Ursitoare; Ursitory; Ushi no toki mairi; Ushi-oni; Usiququmadevu; Ušumgallu; Uwan; Uylak; Uzuh;

Vadavagni; Vadleány; Vaettir; Vættir; Vahana (Mount of a Deva); Vainakh religion; Vairies; Vajrakilaya; Vajranga; Vajrayakṣa; Valac (demon); Valefar; Valkyrie; Valravn; Vâlvă; Vampire folklore worldwide; Vampire pumpkins and watermelons; Vampire; Vanapagan; Vanara; Vanir; Vanth; Vântoase; Varaha; Varahi; Vardivil; Vardøger; Vardögl; Vardöiel; Vardygr; Vassago; Vasuki_Naga_King; Vattar; Vazily; Vazimba; Ved; Vedmak; Veðrfölnir; Vegetable Lamb of Tartary; Vegoia; Vel; Veleda; Vellamo; Vemacitrin; Venediger Männlein; Ventolín; Verechelen; Verlioka; Vermillion Bird; Vesna; Vetala; Viðfinnr; Vidyadhara; Vidyādhara; Vihans; Vila; Vilenaci; Vileniki; Vili Čestitice; Vine (demon); Viprachitti; Viradha; Vishala; Vishap; Vision Serpent; Vitore; Vittra; Vivani; Vivene; Vjesci; Vodni Moz; Vodyaniye; Vodyanye; Vǫrðr; Vörnir (joetunn); Vosud; Vouivre; Vritra (dragon); Vritra; Vrukodlak; Vrykolakas; Vyaghrapada; Vyatka;

Waalrüter; Wadjet; Wag at the Wa'; Waira; Waitoreke; Wakinyan; Wakwak; Waldweibchen; Waldzwerge; Walgren Lake Monster; Walter of Aquitaine; Waluburg; Wampus Cat; Wandjina; Wangliang; Wani; Wanyūdō; Warak ngendog; Warlock; Wars and Sawa; Watatsumi; Water Bull; Water Horse; Watermöme; Wati kutjara; Wawel Dragon; Wayob; Wechselbalg; Wechuge; Weiße Frauen; Wekufe; Welsh Dragon; Welsh Giant; Wendigo; Werecat; Werehyena; Wereleopard; Werewolf; Werewolves of Ossory; Wewe Gombel; Whakatau; Whiro; White dragon; White Ladies; White Lady (wiki); White Lady; White River Monster; White Tiger; White Women; Whowie; Wicht; Wichtel; Wiedergänger; Wight; Wihwin; Wild Haggis; Wild Hunt (wiki); Wild Hunt; Wild Hunter; Wild Man of the Navidad; Wild Man; Wild Men; Wild Women; William of Lindholme; Will-o'-wisp; Willy Rua; Wind Folletti; Wind Horse; Winged cat; Winged Lion (St. Mark); Winged lion; Winged Unicorn; Wirnpa; Wirry-cow; Wisdom King; Witch; Witches of Anaga; Witege; Witte Juffern; Witte Wieven; Witte Wijven (Moerae); Witte Wiver; Wives of Rica; Wolpertinger; Wolterken; Wolves in heraldry; Woman in Black (supernatural); Wood Folk; Wood Maidens; Wood Men; Wood Trolls; Wood Women; World Elephant; World Turtle; Worm of Linton; Wrathful deities; Wulver; Wurdulac; Wurm; Wutong Shen; Wuzhiqi; Wyvern;

Xana; Xanthippe; Xanthus; Xaphan (demon); Xeglun; Xelhua; Xezbeth; Xhindi; Xian; Xiangliu; Xiao; Xicalancatl; Xiezhi; Xingtian; Xirang; Xiuhcōātl; Xtabay;

Y Ladi Wen; Yacumama; Yacuruna; Yahui; Yako; Yakseya and Yakka; Yaksha; Yakshini; Yakusanoikazuchi; Yale; Yali; Yallery Brown; Yalungur; Yam; Yama; Yamabiko; Yamabito; Yamaduta; Yamainu; Yamajijii; Yamantaka; Yamata no Orochi; Yama-uba; Yamawaro; Yanari; Yan-gant-y-tan; Yao Grass; Yāoguài; Yara-ma-ya-who; Yarthkins; Yarupari; Yashima no Hage-tanuki; Yateveo (Plant); Yato-no-kami; Yawyawk; Yazata; Yee-Na-Pah; Yehasuri; Yeii; Yekyua; Yelbeghen; Yellow Lung; Yemọja; Yenakha Paotapi; Yer iyesi; Yeren; Yernagate; Yer-sub; Yeti; Yinglung; Yobuko; Yōkai; Yokkaso; Yōsei; Yosuzume; Yotsuya Kaidan; Youkai; Yowie; Ypotryll; Ysätters-Kajsa; Ysbaddaden; Ysgithyrwyn; Yuki-Onna; Yule cat; Yum Kaax; Yumboes; Yume no seirei; Yūrei; Yuxa;

Zabaniyah; Zahhāk; Zahreil; Žaltys; Zana; Zână; Zaqar; Zār; Zaratan; Zarik; Zartai-Zartanai; Zashiki-warashi; Zȃzȇl; Zburător; Zduhać; Zelus; Zemi; Zennyo Ryūō; Zhenniao; Zheuzhyk; Zhu Bajie; Zhulung; Zhytsen; Zilant; Zimbabwe Bird; Ziminiar; Zin Kibaru; Zin; Zinselmännchen; Zipacna; Zitiron; Ziz; Zlydzens; Zmaj; Zmei (aka Zmei Gorynich); Zmeoaică; Zmeu; Zojz_Albanian_Deity; Zombie; Ztrazhnik; Zuhri; Zuibotschnik; Zuijin; Zulu religion; Zumbi; Zwerg; Zwodziasz;

#mythic creatures#mythic creature list#legendary creatures#legendary creature#legendary being#legendary beings#creature list#legendary creature list#monster list#list of monsters#worldbuilding#mythological creature list#mythic beings#mythic monsters

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

So what is the deal with Feminine Tishtrya in Sogdia? Lilla Russell-Smith in her paper on the "Sogdian Daena" painting says that Tishtrya is depicted as feminine in Sogdian art up until Islamization, but I'm having a hard time finding those examples. I know of some Sogdian influenced Chinese astrological icons that depict a Tish-influenced Mercury as feminine, but none from Sogdia itself

Great question, as usual. I’ve been obsessed with the supposed attestations of feminine Tishtrya for a bit over a year by now, so thanks for giving me an opportunity to talk more about this topic. I feel obliged to let you know right away there’s no major conclusion to draw, though.

To begin with, ultimately there is only a single indisputable depiction of more or less feminine Tish(trya)/Tir(iya), and it’s Kushan rather than Sogdian. On a coin of Huvishka only known from a single exemplar, a feminine figure armed with a bow is labeled as Teiro (TEIPO):

The feminine Teiro on a coin, British Museum (note the catalog erroneously identifies the deity as Nana despite the inscription clearly reading TEIPO…); reproduced here for educational purposes only

More under the cut.

Michael Shenkar (Intangible Spirits and Graven Images, p. 149) notes that this version of Tir/Tishtrya (I’ll try to stick to gender neutral terms through the response if you don’t mind) has been variously compared with the iconography of Artemis, Apollo and Nana(ya), and that the last of these three deities offers the closest parallel overall. However, he suggests this unusual image might simply reflect the association with Apollo attested further west, and that the deity is meant to be a youthful man, not a woman (p. 151).

Matteo Compareti (Literary and Iconographical Evidence for the Identification of the Zoroastrian Rain God Tishtrya in Sogdian Art, p. 117) doesn’t mention Apollo as an option, though, and concludes the iconography was evidently borrowed from Artemis. Harry Falk goes even further and suggests the Teiro coin was in fact recut from a Nanaya one of the Artemis-like variety (Kushan rule granted by Nana: the background of a heavenly legitimation, p. 290). The example he uses as evidence is indeed remarkably similar, and similarly was minted during the reign of Huvishka:

Nana on a coin of Huvishka, British Museum; reproduced here for educational purposes only.

Of course, this raises a question of how the relationship between Nana and Teiro was imagined. Based on the attested equivalence between their western counterpart and Nabu it is generally accepted they formed a couple, but this doesn’t really explain why they would be depicted so similarly, especially given that character-wise Nanaya has very little in common with them. As far as I am aware no serious attempts have been made to explain this, though I’ll return to this matter for a bit later on.

While I don’t necessarily think Shenkar is wrong to be skeptical about the gender of Teiro, I will note a difference in gender between western and eastern versions of an Iranian deity would not be unparalleled - Vanant is male in the Avesta, and I’m pretty sure the same holds true for Middle Persian sources, but on Kanishka’s coins the cognate name “Oanindo” (OANINΔO) pretty clearly designates a goddess visually patterned after winged Nike (Intangible spirits, p. 151-152). Drvaspa’s eastern counterpart Lrooaspo (ΛPOOACPO), on the other hand, is male in contrast with the female Avestan version (p. 96-97). Shenkar himself admits that “it is easy to envisage the same divinities being perceived not only as having different functions, but also being of different sex” (p. 97).

That’s essentially it for the Kushan evidence.

As for Sogdia - there’s quite a large repertoire of deities in Sogdian art who appear fairly consistently, but are not provided with any textual identifications, in contrast with Kushan art where everyone is neatly labeled.It’s probably safe to assume that some depictions of Tish are available to us already, and simply have yet to be identified with certainty. An argument in favor of this would be Tish’s popularity reflected in theophoric names - if Nanaya, Weshparkar or Sraosha can serve as parallels for comparative purposes, it does seem popular devotion translated into being commonly depicted in art as well.

For specific candidates, I’ll go back to Literary and Iconographical Evidence (...), since it's the most recent I have. The core criteria for identifying depictions of Tish in Sogdian art Compareti uses is fairly sound. Based on the commonly accepted assumption that they were closely associated with Nana(ya), armored figures holding objects which might be arrows (an attribute of Tish as a divine archer) appearing alongside her in paintings, ossuaries etc. are identified as Tish (p. 111-115). While the state of preservation and quality of reproductions in literature often leave a lot to be desired, I do think it’s fair to speak of the companion of Nana as a distinct entity iconographically, and I’m not aware of any identification with an equal number of supporters as Tish. Therefore, it seems safe to say these examples listed by Compareti are indeed them: