#we had a whole unit in personality on buddhism and another on hinduism

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

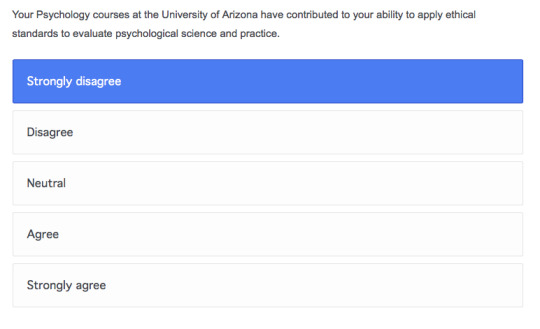

So I’m taking this graduation survey from my school’s psychology program and god. I’m going to put the longer part of my rambling rant at my school under a cut, but I thought this one deserved to be above it.

So first there’s this:

[[image reads: “your Psychology courses at the University of Arizona have contributed to your ability to apply ethical standards to evaluate psychological sciences and practice.” with options “strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, or strongly agree.” Strongly disagree is highlighted.]]

actually laughed out loud. The U of A psych department knows SO MUCH about ethics, clearly, with professors leaving due to racism experienced while other, tenured, professors take money from a literal actual eugenics fund and no one official bats an eye because, hah, who cares? Being supported by eugenicists doesn’t make you one, obviously!! (It does here, sry.) Also I spent a whole fucking semester with Eugenics Scrooge, telling you all the bullshit she came up with, and she’s still teaching the same fucking class at this very moment and no one talked to her about it, so I’m gonna guess no.

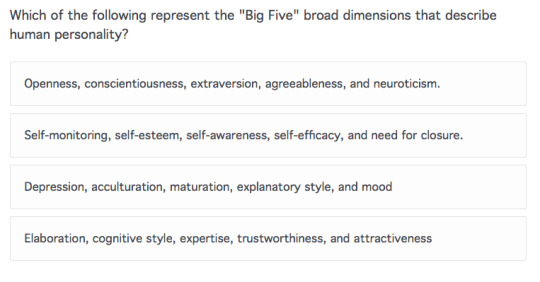

Also there’s this little quiz at the end testing whether they managed to teach us basic psychological concepts and THEY ABSOLUTELY DID NOT.

My first semester here I actually took PERSONALITY PSYCHOLOGY and we spent absolutely no time whatsoever, at all, learning about idk, relevant topics to personality?? We learned that there WERE personality disorders, we did not learn what they were, and unfortunately we did not cover the Big Five even in title.

Now, pre-University of Arizona, I was actually interested in the field of psychology research so I do know a bit, but only because I used to read studies on my own, plus I’ve read tons of medical journals out of necessity for my own survival with a semi-rare disease so I may not know everything about those fields, but I have a pretty good idea of the scientific method, of research standards, and of academic writing. And I have friends who are social workers, half my family has psych degrees, and a lot of people in both those groups including myself have actually been to therapy so I have some basic knowledge on topics like what cognitive behavioral therapy is and what the Big Five are (it’s the first option.)

But DAMN nothing highlights how bad my education really has been like seeing what the actual people in charge of my education THINK they should have taught me, knowing they haven’t even a little.

There was a little spot on the survey in which I could tell them how to improve the program, and I was like, “I literally know almost nothing more about psychology than when I started this degree, with the exception of a few studies I’ve read now that I easily could have read for free in the public domain and not paid more money than I’ll ever make in my lifetime for professors to take the easy way out of actually teaching an online class. Hey also, I would have had a MUCH better time here if the U of A would decide that eugenics wasn’t okay and not have a professor literally teach the class that humanity would be better off if people like me were dead but hey, at least the academic advisors in the psych program are good, sure!” except slightly more professionally... slightly.

Anyway, I go to school in The Bad Place honestly.

#sometimes in math or french i'm like 'did i learn this? i really don't think i ever did'#and i could be wrong#because i easily could have missed it or forgotten because i didn't really get it#but i'm actually good at social science and I used to like it before this hellhole ruined it for me forever so I would definitely remember#if we had learned this#and i specifically remember asking why we didn't learn this#no answer#except that the prof wanted to make the class 'more unique' or whatever like wow thx that makes up for not having a real education in#the thing i'm studying#but you know what we DID learn??#we had a whole unit in personality on buddhism and another on hinduism#which i'll totally give you that studying religions like those from a perspective of serving a purpose towards psychological health is#interesting#BUT IT IS DEFINITELY NOT PERSONALITY#my pointless rants have sources maybe I AM academic#but if i am#blame it on my anthropology minor which has been AMAZING and taught me far more than my actual major#sure a lot of it was reading articles on my own that i probably could have done for free if i'd googled the class title in google scholar#but they were actually curated to include ranges and then DISCUSSED you know#because i actually like the subject and professors teaching it did so ethically and well and usually really interestingly#like you're SUPPOSED TO DO IN HIGHER EDUCATION#(okay i don't hate all social science but i'm certainly never working in it and I don't think I'll ever touch psychology in any official#capacity with a 10 foot pole)#i miss music school

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Benzaiten Steel and the Fragility of Perception

or: reasons why setting boundaries is important #1283

I’ve figured out a reason why Benzaiten Steel stayed with his mother instead of doing the “sensible” thing and moving out. I think that it’s possible, too, that Juno has always been aware of the answer but, in the scope of Juno Steel and the Monster’s Reflection, he isn’t able to face it head-on because it contradicts his black/white, either/or sense of morality.

TL;DR: Despite Juno Steel’s unreliable narration we are able to see clearly the enmeshed relationship Benzaiten had with their mother Sarah and the ways in which that unhealthy family dynamic shaped Juno Steel as a person.

Sources: 50% speculation, 20% lit crit classes, 30% my psychology degree.

Juno’s perception of Ben is shallow and filtered through the limitations of human memory. We all know by now, too, that Juno’s an Unreliable Narrator™. In light of this, we need to ask ourselves why it is that Juno remembers Ben as happy, supportive, and only ever gentle in the challenges he poses to Juno. Throughout the episode, Ben’s memory is clearly acting as a comforting psychopomp: he ferries Juno through the metaphorical death of his old understanding of his mother (and also himself) and into a new way of thinking. He does this through persistent-but-kind questions, never telling Juno what to do or how to do it. This role could have been played by anyone in Juno’s life (Mick and Rita come to mind first) which makes it telling that Juno’s mind chose Ben to fill this role.

Juno’s version of Ben is cheerful, endlessly patient with Juno and Sarah, and above all he is compassionate. He acts as a mediating presence between Juno and Juno’s memory of Sarah and he doesn’t ask a whole lot for himself. If this is Juno’s strongest memory/impression of Ben’s behavior and perspective, then we can draw some conclusions about the roles they each played in the Steel family unit: Juno was antagonistic to Sarah and vice versa, and Ben was relegated to the role of mediator for the both of them.

Juno: She’s just evil. Ben: That’s a big word. Juno: “Evil”? Ben: No, “Just”.

We can see in this exchange that Ben is a vehicle for the compassion Juno needs to show not only to Sarah but to himself, too, in order to move on and evolve his understanding of his childhood traumas.

This is not necessarily an appropriate role for a sibling or a child to hold in a family unit.

In family psychology, one of the maladaptive relationship patterns that is discussed is enmeshment. Googling the term you’ll find a lot of sensational results (e.g. “emotional incest syndrome”) that aren’t necessarily accurate in describing what this dysfunction looks like in the real world. This is in part because enmeshment can present many different ways. So, in order to proceed with this analysis of Benzaiten Steel’s relationship with his mom, I need to define enmeshment.

Enmeshment occurs when the normal boundaries of a parent-child relationship are dissolved and the parent becomes over-reliant on the child, requiring the child to cater to their emotional needs and to otherwise become a parent to the parent (or to themself and/or to other children in the family). This is easiest to spot when a parent confides in a child as if they’re a best friend, disclosing details of their romantic life, expecting the child to give them advice on coping with work stress, and similar. Once enmeshment occurs, any kind of emotional shift in one member of the enmeshed household will reverberate to the others; self-regulation and discernment (e.g. figuring out which emotions originate in the parent and which ones originate in the child) becomes extremely difficult for the effected child and parent. When an enmeshed child becomes an enmeshed adult they often have issues with self-identity and interpersonal boundaries. For example, they may struggle to define themselves without external validation and expect others to be able to intuitively divine their emotions. After all, the enmeshed adult could do this with their parent and others easily due to hypervigilance cultivated by their parent and they may not understand that such was not the typical childhood experience. These adults are often individuals to whom the advice “don’t set yourself on fire to keep someone else warm” is often relevant and disregarded. They may perceive their own needs as superfluous to others’-- and resent others as a consequence.

Another layer of complication is added when the parent in an enmeshed relationship is an addict, as Sarah Steel was. The enmeshed child often times becomes the physical caregiver to their parent as well and must cope with all the baggage loving an addict brings: the emotional rollercoaster of the parent trying to get clean or the reality of their neglecting or stealing from their child to support their habit or their simply being emotionally absent. Enmeshment leaves children with a lot of conflicting messages about their role in the family, how to conduct relationships, and how to define themself.

We only get an outside perspective on this enmeshment in the Steel family. It’s clear in the text that Juno’s relationship with his mother was fraught. He jokes in The Case of the Murderous Mask that she didn’t kill him but “not for lack of trying”, implying that Ben’s murder wasn’t the first time Sarah Steel lashed out at Juno-- or thought she was lashing out at Juno but hurt Ben instead. During the entire tenure Juno’s trek through the underworld of his own trauma, Juno asks the specter of Benzaiten over and over, “Why did you stay?”. This is a question that Juno himself can’t answer because Ben, when he was alive, probably never gave him an answer that Juno found satisfactory. There are a few possibilities, which I can guess from experience, as to what the answer was:

Ben may never have been able to articulate that his relationship with their mother left him feeling responsible for her wellbeing.

Or, if he ever told Juno that, Juno may have simply brushed off this concern. After all, as far as Juno was concerned, Sarah was only ever just evil. To protect himself from his mother’s neglect and codependence, Juno shut down his own ability to perspective-take and think about the nuances that might inform a person’s addiction, mental illness, abusive behavior, etc.

It is likely that Ben thought either his mother needed him to survive or, alternatively, that he couldn’t survive without her-- as if often the case with children who are enmeshed with their primary caregiver. It was natural and necessary for him, from this perspective, to stay. Enmeshment is a very real psychological trap.

It is often frustrating and hard as hell to love someone who is in an enmeshed relationship because, from the outside, the damage being done to them seems obvious. See: Juno’s assertion that Sarah was just evil. Juno is, even 19 years later, still angry about Sarah Steel and her failures as a parent and as a person. His thinking on this subject is very black-and-white. He positions Sarah as a Bad Guy in his discussions with Ben-the-psychopomp and the childhood cartoon slogan of “The Good Guys Always Win!” is repeated ad nauseum throughout Juno’s underworld journey. This mode of thinking serves two purposes:

First, it illustrates the role Juno played in the household: he was opposed to Sarah in all things and Sarah did not require any compassion or enmeshment from Juno. Juno was, quite possibly, neglected in favor of Ben which would create a deep resentment… toward both Sarah and toward Ben. This family dynamic would reinforce Juno’s shallow moral reasoning and leave him with vague, unachievable ideals to strive for like “Be One of the Good Guys” or “Don’t Be Like Mom” -- ideals that he can’t reach because he is a flawed human being and not a cartoon character, creating a feedback loop of resentment toward his mother and guilt about resenting Benzaiten. That guilt would further bolster Juno’s shallow memory of Ben as being infallibly patient, kind, loving, etc.

Second, Juno’s black/white moral reasoning is an in-text expression of the meaning behind Juno’s name. When “Rex Glass” points out that Juno is a goddess associated with protection, Juno immediately has a witty, bitter rejoinder ready about Juno-the-goddess killing her children. Juno was named for a deity who in some ways strongly resembles Sara Steel and he resents that he is literally being identified as his own mother. Juno-the-goddess has one hell of a temper, being the parallel to Rome’s Hera. Juno is not a goddess (detective) who forgives easily when she (he) knows that a child (Benzaiten Steel) has been harmed. This dichotomy of “venerated protector” versus “vengeful punisher” causes psychological tension for Juno that is only partially resolved in The Monster’s Reflection. The tension is not fully resolved, however, because Juno never gets a clear answer for the question, “Why did you stay?”

The answer is there but it is one that Juno doesn’t like and so can’t articulate: Ben is enmeshed with Sarah who named him, of all things, Benzaiten and that is why he stayed. We’ve already seen that names have intentional significance in the text. Benzaiten is hypothesized to be a syncretic deity between Hinduism and Buddhism, is a goddess primarily associated with water. Syncretic deities are fusions of similar deities from different religions/cultures; their existence is the result of compromise and perspective-taking and acceptance. Water, too, is forgiving in this way: it takes the shape of whatever container you pour it into... not unlike a child who is responsible for the emotional wellbeing of their entire family unit. Not unlike Benzaiten Steel.

Ben stayed with his mother because his relationship with his mother was enmeshed, leaving him little choice but to stay, and this ultimately led to tragedy. Sarah Steel’s failures as a parent are many and Juno still has a lot of baggage to unpack in that regard, especially where Ben is concerned. It’s unlikely that we’ll get the same kind of “speedrunning therapy” episode again but I know that The Penumbra is committed to a certain amount of psychological realism in its character arcs so I am confident in asserting that Juno Steel isn’t finished. Recovery is a journey and he’s only taken the first steps.

#juno steel#benzaiten steel#meta#the penumbra podcast#benten steel#sarah steel#psychology#enmeshment#bad parenting#iimpavid writes#chatter#the monster's reflection#the case of the murderous mask

309 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Hard Science of Reincarnation

The nightmares began when Ryan Hammons was 4 years old. He would wake up clutching his chest, telling his mother Cyndi that he couldn’t breathe and that his heart had exploded in Hollywood. But they didn’t live in Los Angeles; Hammons’s family resided in Oklahoma.

A few months prior, in early 2009, Ryan had started talking about going home to Hollywood and pleaded with Cyndi to take him to see his other family. He would yell, “Action!” and pretend to direct films when he played with friends; he knew scenes from a cowboy movie he had never watched; and said a cafe reminded him of Paris, where he had never been. He talked about his child, worldly travels, and his job at an agency where people changed their names. Cyndi didn’t think much of it until the nightmares set in and Ryan started describing death.

Hoping to figure out what he was talking about, Cyndi went to the public library and checked out a few books about Hollywood. She was flipping through one of them when Ryan got excited at a photo from the 1932 movie Night After Night. “Hey Mama, that’s George. We did a picture together,” he told her. “And Mama, that guy’s me. I found me.” George, Cyndi discovered, was George Raft, an actor and dancer who specialized in gangster films in the 1930s and 1940s. She couldn’t track down the name of the man Ryan had identified as himself.

Cyndi had never encountered anything like this before. She was a county clerk deputy who’d been raised in the Baptist church. Her husband, Kevin, was a Muskagee police officer and the son of a Church of Christ minister. She considered them to be fairly ordinary people, but she was starting to wonder if Ryan wasn’t so ordinary. Cyndi contemplated the possibility that this could be a case of reincarnation.

Cyndi contemplated the possibility that this could be a case of reincarnation.

Though she could have looked to one of the religions that hold a belief in reincarnation, such as Hinduism or Buddhism, instead, Cyndi turned to science. In February 2010, she wrote a letter to the Division of Perceptual Studies in the psychiatry and neurobehavioral department at the University of Virginia School of Medicine. Within weeks, they wrote back; Ryan was far from alone in having memories of a past life.

The roots of the Division of Perceptual Studies stretch back to the 1920s, when Dr. Ian Stevenson was growing up in Canada. A sickly child, he contracted bronchitis numerous times and spent hours in bed, devouring his mother’s extensive collection of books on Eastern religions. It was in those pages that he was first exposed to reports of paranormal phenomena. He claimed to possess an unusually good memory and earned his medical degree at McGill University in 1943, before moving to Arizona. He briefly studied biochemistry before moving to psychosomatic medicine, in search of “something closer to the whole human being” than what he had found in biochemistry. From there, he trained in psychiatry and psychoanalysis.

His academic career flourished in the U.S. and he was named chairman of the department of psychiatry at the University of Virginia (UVA) in 1957, while still in his 30s. Around that time, he revived his childhood interest in the paranormal. He dipped his toes into the waters of parapsychology—the study of mental abilities that seem to go against or be outside of the known laws of nature and science—by writing book reviews and articles for non-academic publications like Harper’s magazine.

The most convincing cases, he realized, all involved young children, generally between the ages of 2 and 5, who spoke in great detail of places they had never visited and people they had never met.

In 1958, he won the American Society for Psychical Research’s contest for the best essay on paranormal mental phenomena and their relationship to life after death. His essay, “The Evidence for Survival from Claimed Memories of Incarnations,” looked at 44 cases of individuals around the world who had memories of past lives. The most convincing cases, he realized, all involved young children, generally between the ages of 2 and 5, who spoke in great detail of places they had never visited and people they had never met, or who had birthmarks corresponding to injuries incurred by other people when they faced violent, untimely deaths. Most of those cases were in Asian countries where belief in reincarnation was already high.

Chester Carlson, a wealthy physicist who invented the photocopying process that led to the Xerox Corporation’s founding, read Stevenson’s winning essay. Having become interested in parapsychology through his wife Dorris, Carlson contacted Stevenson with an offer of funding; Stevenson declined. But Stevenson fell deeper into his new research, taking his first fieldwork trip to interview children with past-life memories in India and Sri Lanka in 1961 and publishing his first book on the topic, Twenty Cases Suggestive of Reincarnation, in 1966. He reconsidered Carlson’s offer; the following year, the funding allowed him to step down as chair of the psychiatry department to focus full-time on his reincarnation research—a move that pleased the dean of UVA’s medical school, who was not thrilled with the direction that Stevenson’s work was taking. But when Stevenson stepped down, the dean agreed to let him form a small research division in which to do his curious new research within UVA that still exists today.

Carlson died unexpectedly the next year and left UVA $1 million to support Stevenson’s research. Over the following decades, Stevenson traversed the globe tracking down instances of children with past-life memories, logging an average of 55,000 miles a year and identifying over 2,000 cases. Along the way, he authored more than 300 publications, including fourteen books.

The new research division at UVA was called the Division of Parapsychology—a name forced onto Stevenson, according to Dr. Jim. B. Tucker, the division’s current director. Stevenson changed the name to the Division of Personality Studies, concerned that parapsychology was isolating itself from the rest of academia. The vagueness of “personality studies” suited Stevenson, as he continued working to gain the respect of mainstream science. That mission permeated his studies: He ceaselessly quantified his data—coding 200 variables in his database of cases, calculating the probabilities of one or two birthmarks corresponding to one or two wounds on another person’s body, and painstakingly examining every possible normal, as opposed to paranormal, explanation—in a bid to be taken seriously. Now, the research unit is called the Division of Perceptual Studies, or DOPS, and remains up and running despite Stevenson’s death in 2007. There, Cyndi Hammons’s letter about Ryan’s Hollywood memories found Tucker.

Tucker traveled to Oklahoma to meet the Hammons family in April 2010. With help from a TV crew that was following Ryan’s case, they identified the man in the photo from Night After Night as Marty Martyn, who died in 1964. Tucker showed Ryan photos of people Martyn had known in sets of four, asking if anyone looked familiar. He later realized this wording was too vague, especially for a 6 year old, but Ryan did pick out Martyn’s wife, saying that she looked familiar, but that he wasn’t sure how he knew her. Together, they flew to Los Angeles and met Martyn’s daughter, who’d been 8 years old when her father had died. Ryan was confused to find she had grown.

Tucker fact-checked some of Ryan’s memories with Martyn’s daughter. A lot of the details proved accurate; a lot of them did not. Some couldn’t be verified. Martyn had acted as an extra in movies before becoming a talent agent. He and his wife had traveled the globe. Ryan had talked about dancing on Broadway, which Tucker thought unlikely for someone who’d been an extra with no lines, but Martyn’s daughter verified those memories. He had mentioned two sisters and a mother with curly brown hair—also true. He recalled his address having Rock or Mount in its name, and Martyn’s last address was 825 N. Roxbury.

Ryan Hammons recognized the actor George Raft in old Hollywood photographs when he was a child. (John Springer Collection/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images)

But his heart had not exploded. Martyn had leukemia and died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1964. Ryan had also said that his father had raised corn and died when he was still a child, which didn’t prove accurate. Still, the case presented “strong evidence for reincarnation,” Tucker wrote in his 2013 book, Return to Life, in which he documented this story, but it was certainly not definitive.

“What this offered was an opportunity to look at the big picture, this question of there being more of us than just the physical.”

When Tucker first heard about Stevenson’s research on reincarnation, he was a child psychiatrist in private practice in Charlottesville, Virginia, where UVA is located. He didn’t believe in reincarnation, but his wife was open to ideas about reincarnation and psychics, so he gradually opened up to those concepts too. And his wife wasn’t alone: A 2018 Pew Research Center poll found that 33 percent of adults in the United States believe in reincarnation. After reading one of Stevenson’s books, he heard that DOPS was doing a project on near-death experiences—another field of research within parapsychology—and reached out. He began working there part-time in 1999.

“What this offered was an opportunity to look at the big picture, this question of there being more of us than just the physical. That was really quite appealing—and not just the question but also the approach to the question, that these were rational, serious-minded people that were doing this work,” he told VICE News.

Ten years prior to meeting the Hammons family, Tucker gave up his private practice to join DOPS full-time. For nine years, he also served as medical director of UVA’s Child and Family Psychiatry Clinic alongside pursuing his parapsychological research through DOPS. Most of Stevenson’s work focused on reincarnation in Asia, but as Tucker plunged into researching past-life memories, he realized that if he were to get Americans to consider his work seriously, he needed to search for cases among those in the U.S. that didn’t believe in reincarnation.

Tucker has now published two books documenting cases of children with past-life memories—a term he prefers over the flashier “reincarnation.” He writes in a decidedly more approachable voice than Stevenson did, aiming for a mainstream audience instead of an academic one. “Ian's primary goal was to get the scientific world, the scientific establishment, to seriously consider this possibility [of reincarnation]. And that's a pretty tough audience,” he said. “But beyond that, if you just write for that audience for decades, at some point you have to decide that the rest of the world needs to hear about it too.”

Even in Europe, where parapsychological research is more common in universities like the University of Edinburgh and the University of Northampton, the broader psychology community remains skeptical of this work.

In spite of Stevenson’s attempts to turn reincarnation studies into a hard science, parapsychology is still a stigmatized niche within academia, where it is not viewed as a very respectable field. It’s one of the reasons that Tucker, as well as many other parapsychologists, keeps one foot in mainstream psychiatry or psychology while pursuing their parapsychological research. Even in Europe, where parapsychological research is more common in universities like the University of Edinburgh and the University of Northampton, the broader psychology community remains skeptical of this work.

Tucker and his colleagues at DOPS are not the only academics in this field in the U.S, either. “I think there's an assumption oftentimes that if you're studying parapsychology, that means that you absolutely believe everything you're studying, and I try and work hard to say that you don't have to believe in everything you study. It's an academic interest and these are experiences that human beings have reported across different times and across cultures, and we really need to try and understand all aspects of human experience,” said Christine Simmonds-Moore, a parapsychologist and associate professor of psychology at the University of West Georgia.

Simmonds-Moore gravitated towards the paranormal as a child in the UK, but it wasn’t until she was far into her psychology degree that she realized she could actually study paranormal phenomena seriously. After getting her PhD in England, she moved to the US to research at the Rhine Center, an independent parapsychology research center in North Carolina that was once affiliated with Duke University. It was while working there that she first encountered the researchers at UVA.

She never met Stevenson, but she distinctly remembers her first visit to DOPS. “It does send shivers down your spine when you go into the room and you see all the filing cabinets containing all of the cases of the past lives that were investigated by Stevenson,” she told me. “You see all of his work and you see all of the things that he collected from his travels whilst he was doing the investigations. So there are lots of artifacts on the walls there. It's quite a beautiful experience just to see the room with these filing cabinets.”

Not everyone is so moved by Stevenson and Tucker’s work. Christopher French, a professor of psychology at Goldsmiths, University of London, considers himself a skeptic when it comes to paranormal phenomena, despite conducting some of his own research on past-life memories. He began his career studying mainstream neuroscience before embracing anomalistic psychology, the study of human behavior associated with the paranormal but based on the assumption that nothing paranormal is involved. French’s new direction was, he described, “tolerated” by his department, and he had to keep up his more mainstream psychological research in parallel with the anomalistic work that interested him far more.

“I think they are false memories that have arisen as a result of a kind of interesting social psychological interaction between the child and those around them.”

He thinks the most plausible explanation for the majority of cases is that the children are experiencing false memories, though he maintains respect for Stevenson’s meticulous research. “I think they are false memories that have arisen as a result of a kind of interesting social psychological interaction between the child and those around them,” he argued. “You do wonder to what end the researchers are kind of just finding the things that match what's gone on.” He thinks that young children will often say things that don’t make sense to their parents when they first start to speak and the parents will then inadvertently feed them information as they begin to wonder whose life the child could be describing—perhaps showing them photographs and asking if they remember the people in the picture and “having this interaction that ultimately will produce a situation where they've unintentionally implanted false memories,” as French put it.

Stevenson’s work informed French’s own forays into investigating children with past-life memories. Many years ago, the two men met when seated next to each other at a conference dinner. “He came across as a very intelligent, reasonable person,” French recalled. “I think his work is very good as far as it goes, but I don't think it's the whole story.”

He doesn't, however, question the necessity of the research itself. “There could only be two possibilities. One is that there is something genuinely paranormal happening, and if that is true, that would be amazing,” he told me. “Or, alternatively—which is more the line that I do favor—it tells us something very interesting about human psychology. So either way, it's worth taking seriously.”

Dr. Anita H. Clayton, chair of UVA’s psychiatry and neurobehavioral department, which houses DOPS, echoed that sentiment: “My question is, Where should DOPS be if it's not in the department of psychiatry? And where should it be if it's not in academics? Because I think what scientists do is dispassionately investigate phenomena that we don't yet understand.”

And yet, mainstream science still largely relegates parapsychology to its own community, with researchers struggling to get their work published in major journals. Instead, they often publish in parapsychology journals, which, all the parapsychologists I spoke with agreed, is a bit ineffective—they are preaching to the choir when they would rather be reaching the skeptics.

On April 30, 2011, the TV show that had followed Ryan Hammon’s case, The UneXplained: A Life in the Movies, aired on the Biography Channel. As a young child, Ryan had always been shy about sharing his Hollywood memories out of fear that people would think he was crazy; his parents, too, had been nervous about what people in their small town would think of them. But just over a year after Cyndi sent that first letter to DOPS, her family’s story appeared on national television. In the end, the family thought the producers did a great job. Soon after the episode aired, Ryan stopped talking about Marty Martyn. Within six months, Ryan had taken down his Martyn-themed bedroom decorations—an iron Eiffel Tower, pictures of New York—and told his mom it was time to be a regular kid.

After more than two decades of researching children with past-life memories, Tucker is still getting letters about children like Ryan and he is still seeking out new cases. At his last count, there were about 2,200 cases coded in his database. He describes himself as “spiritual but not religious,” and his goal remains unique from Stevenson’s, who was open about his unfulfilled quest for mainstream science to value his life’s work.

“A lot of it, to be perfectly honest, is trying to figure out the answers for myself,” Tucker told me. “Hopefully my work or my writings have had a positive impact on some people, but they're still trying to answer the question of, What is the level of evidence that, in fact, there is this part of us that survives after the body dies?”

The Hard Science of Reincarnation syndicated from https://triviaqaweb.wordpress.com/feed/

0 notes

Text

TOP 5 Asians, according to Comrade of TAS

You know I just had to put a Jesus meme in here. ESPECIALLY with Will Smithy in it.

Man it’s been some time since lil’ communistrade of TAS did one of these. It is good to be back. Let’s get right.... into the news blog post.

I’m sorry for anybody who’s reading this blog post but I require memes as my personal diet that also consists of vegan and gluten-free ice cubes.

Number 5...

is Qin Shi Huangdi. Technically the first emperor to unite China as a whole. Before that, there were random dynasties sprouting all over China and Qin decided,

“You know what Jim, I feel like all these dynasties are not really together you know. Man, I wish they could be, like a family or so.”

And so henceforth, China was united. There was probably some periods where they weren’t.. but still, they are still today. If there was no Qin Shi Huangdi, there wouldn’t be the Wall of China because nobody wouldn’t think of it. If there wasn’t Qin Shi Huangdi, maybe Vietnam will get a piece of China (lol). If Qin Shi Huangdi was still a sperm in his daddy’s balls, then the great Xi Jinping wouldn’t exist.

There’s also one more thing about this man Qin, is that he thought that immortality was a thing and he wanted to get it. That’s one of the reasons he is put so low on this list but to be fair, the things he did outweighs the thing that makes him look like a fool.

Number 4 is..

you guessed it, GANDHIENGHIS KHAN. Not Gandhi. Never Gandhi.

I assume you know who GENGHIS KHAN is (you gotta emphasize on that GENGHIS KHAN) but here’s a little something to expand my answer show my effort onto this blog post.

Genghis Khan was the leader of the Mongol empire, which was the largest empire ever, at least connected empire. This bad boy is 9.15 million square miles large. Let’s just take the average size of an American house, 2600 feet -> 0.49~* square miles. Now do 9.15 million miles divided by 0.49 miles and you get a nice little 18,673,469 houses in total. That is a lot of houses. Now for all you metric users, 0.49 square miles is approximately 788.6~** meters.

*estimation

**same with above

To continue, GK also practiced something along the lines of cheap democracy

I mean meritocracy (please don’t lower my grades comrade Matt it’s 9:21 and I usually sleep at 8). It’s an excellent system, especially for a person who’s from the time where they treat women like *4-letter swear word that will make your Grandma cry*.

Lastly he practiced religious tolerance. This was especially great when most of the world practiced religions like Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism. I mean, I can just imagine places where they don’t tolerate other religions and they try to put the practitioners’ head on stakes.

Let’s leave Khan for now. We have to move on to..

number 3.

AND HIS NAME IS

No.. not him. It’s another guy. Don’t know what his name is. Let me just check my files.. hold on a sec.

“STALIN!”

“YA.”

“Do you have the 3rd person’s files?”

“YA.”

“Okay. Can you bring it to me?”

“YA. In America, Stalin brings paper to Ricky. In Motherland, Ricky brings paper to-”

“Stalin please.”

“YA.”

Ahh, here we go. So that was just my fella and me just having some bro time together. After all, we’re in Motherland.

So number 3 is..

you guessed it, again, Siddharta Gautama, otherwise known as Buddha. Everyone’s homie, I guess. Buddha is the founder of one of the largest religions in the world, Buddhism. The main idea behind it is just basically to me is to have peace with the world and gain enlightenment so you can basically go to Buddhaland and not have to suffer anymore.

The Buddha also technically opened up the minds of 488 -> 535 million people. That’s around 10% of the population so that’s quite a lot. And on that note, I’ll stop writing down “that’s” all the time and let’s move on to the 2nd most significant Asian that ever was and probably will ever be. Unless someone gets a revelation from like a god in the sky who tells them to kill all white privileged men and enslave Ricky to the depths of Tartarus.

“AHH.”

“What in the name of the Motherland Ricky.”

“Oh, Stalin, I thought you were with the others.”

“Who?”

“Never mind.”

SO, the 2nd person is..

Muhammad Ali.

“It’s just Muhammad.”

“Stalin, please leave.”

I just had to leave this man who created a religion of peace and was a nice and polite man a nice meme. With his daughter, I MEAN wife with him in this meme.

Anyways, Muhammad was this prophet had a revelation where he saw Gabriel the Angel and then I think Gabe showed him de wae.

I’m sorry for the dead meme. I just enjoy it too much. Muhammad is the founder of the 2nd largest religion in the world. That is of Islam and there is around 1.5 billion Muslims in the world now. That is around 22% of the population, and is quite large considering how Buddhists only make up 10% of the population of the world.

10 pm has passed so I’m going to rush this. Quality may decrease or increase slightly. You might encounter some typos so be awar.

“Ricky.”

“WHAT?”

“You didn’t write aware correctly.”

Okay, fine.

*keyboard clicks*

“Ta-da. Okay, go away now.”

Alright ladies and privileged males, the last person is incoming and he is going to kick arse. Well, not really because he’s- Jesus Christ tHERE’S a sPIDER iN mY rOOM.

Oh wait never mind. He is actually Jesus.

Holy shit. It’s my man. Jesus Christ. I’m sorry for swearing. I’ll just show myself out of the room.

“Ricky where are you going?”

“...”

“Ricky answer me.”

“...”

Jesus is the founder of Christianity, the single largest religion in the entire world. There is a total of 2.2 billion people who identify as Christian and nearly a third of the world, which is 31% is Christian. These statistics trumps (I need to go to sleep) the others with there measly 10% and 22%.

AND, his followers wrote a book called the BIble and has been printed possibly more than 5 billion times. Which is pretty nice considered how 1 person can own two bibles at the same time. Total dedication.

Alright ladies and privileged white-skinned, I guess it’s time for me to check out because I’m running on a mix of dank memes and gluten-free ice cubes. And salty Stalins. But who cares, because at least I finished something I started, and that’s good. Now let’s move on to something else in the future, something where I can write more B.S. about white males and Stalin. On that note,

“Stalin say goodbye.”

“Never. You didn’t reply to me.”

“Bro.”

-Comrade of TAS

0 notes

Link

By Anne Burke

2 January 2019

Around 30 years ago, Jacques-André Istel turned to his wife, Felicia Lee, and said, “We’re going to sit in the desert and think of something to do.”

Hardly an enticing proposition, but by then, Lee was surely used to her husband’s hare-brained schemes.

If I told her tomorrow we were going to Mars, she would say, ‘What do I pack?’

In 1971, at great risk to himself and his then bride-to-be, Istel piloted the couple on a round-the-world flight in a tiny, twin-engine plane that had hardly the oomph of a Chevrolet automobile. Before that, there was the whole business of convincing people to jump out of planes: in the 1950s, after returning home from the Korean War, where he served with the US Marines, Istel developed parachuting equipment and techniques that made it possible for the average Joe to leap out of an airplane at 2,500ft and land as if having tumbled from a 4ft bookcase. Soon, Americans by the thousands were enjoying the latest craze: skydiving.

Lee was a reporter for Sports Illustrated– she met Istel, by then known as ‘the father of American sport parachuting’, during an interview for a piece in the magazine – and had her own taste for adventure. “If I told her tomorrow we were going to Mars, she would say, ‘What do I pack?’,” Istel said.

View image of Thirty years ago, Jacques-André Istel and his wife, Felicia Lee, moved to the California desert to ‘think of something to do’ (Credit: Credit: Anne Burke)

You may also be interested in: • A museum measured in millimetres • A largely unsung piece of Americana • Why this US city is so absurd

And so, in the 1980s, the couple moved to the far south-east corner of California, a few miles west of Yuma, Arizona, off Interstate 8, where Istel had acquired a 2,600-acre parcel of land several decades earlier. Apart from a good aquifer, this particular patch of the Sonoran Desert had little to recommend it. But “we realised that we loved it – the calm, the beauty,” Istel said.

With nothing much around apart from an RV park and some impressively tall sand dunes, the couple’s desert refuge was pretty much in the middle of nowhere. So it made sense, at least in Istel’s fervid imagination, to put it in the middle of somewhere. In 1985, the French-born parachuting pioneer cajoled California’s Imperial County Board of Supervisors into designating a spot on his property as The Official Centre of the World. (Audacious, perhaps, but not necessarily inaccurate, given that anywhere on the Earth’s surface could be the centre.)

A landmark of such importance needed a town of its own. The following year, Istel created Felicity, which now boasts about 15 residents and its own freeway sign. Facing no opposition, Istel got himself elected mayor that same year – apparently for life.

View image of The couple founded the town of Felicity, which they had officially declared the ‘Centre of the World’ (Credit: Credit: Anne Burke)

But Istel wasn’t done with his Xanadu in the desert. He had an idea to build a granite monument with inscriptions honouring people and places important in his life – fellow parachutists, his alma mater (Princeton University in New Jersey), and his family, who had fled France during World War Two and settled in New York. His father, André, had been an advisor to Charles de Gaulle, and his mother, Yvonne, was a wartime volunteer.

Istel didn’t want just any monument. It had to be magnificent and, more importantly, it had to be something that would last far, far into the future. He hired structural engineers who came up with a design for an elongated, granite triangle that just might – “short of the planet blowing up,” Istel said – survive to the year 6000.

The triangular monument went up in 1991; it was 100ft long, about 4.5ft high, and faced with some 60 panels of polished, red granite. The durability came from what was inside: steel-reinforced concrete sunk into trenches 3ft deep.

It's where Martians will come to learn about humanity

Istel then decided he would build another monument, this one to honour US marines who fought and died in the Korean War. Then came a third monument, and a fourth, and a fifth. Today, 20 granite monuments, arranged at artful angles across the desert floor, collectively make up The Museum of History in Granite, a sort of open-air bank of knowledge for the ages. As a visitor posted on TripAdvisor, the museum is where “Martians will come to learn about humanity”.

Istel has engraved his stone triangles with tidy distillations of much of what we know about the world, from the Big Bang to former US president Barack Obama. Visitors – and they come by the thousands each year – learn about Hinduism, the eruption of Vesuvius, the Zapotecs of central Mexico, Buddhism, the birth of Jesus, Attila the Hun, Pythagoras' theorem, the behaviour of the walrus, Greek philosophy, the Gettysburg Address, the Moon landing and terrorism in contemporary times.

View image of Istel was elected mayor of Felicity in 1986 – apparently for life (Credit: Credit: Christian Lamontagne)

Despite his Ivy League background, Istel believes strongly that self-acquired knowledge “is probably the best form of education”. The idea behind these thumbnail sketches of history is to offer just enough information to whet the reader’s appetite. Most topics – even big ones – get at most a couple hundred words.

Lee handles most of the research, using reputable publishers like Oxford, Britannica and Larousse. Istel writes the text, then he and Lee go back and forth on the wording before settling on a final version. An entry titled ‘Interesting Times’ went through 59 drafts. Once the text is ready, professional engravers get to work, often toiling in the glow of lamplight under a night sky to escape the brutal desert heat. To accompany the text, artists etch illustrations into the hard stone panels.

The museum can’t cover everything, so “you pick and choose things that are interesting,” Istel said. He often groups related items into a single theme. The Code of Hammurabi and the Ten Commandments appear under ‘Early Concepts of Law’. The American concept of ‘Manifest Destiny’ is mentioned on a panel called ‘Exploring and Expanding’, along with the expedition of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. Some topics are of personal interest to Istel – parachuting gets ample space – while other topics come as suggestions from others. Lee came up with the idea for a panel on the ‘Great Seal of the United States’, the US’ official coat of arms.

View image of Since 1991, Istel has erected 20 granite monuments depicting the history of the world (Credit: Credit: Anne Burke)

Some of the inscriptions are amusing, if little more. For example, in 1809, US president James Madison proposed a cabinet post of Secretary of Beer. Hamburgers “account for nearly 60% of all sandwiches eaten”. The grizzly in California’s original Bear Republic flag “looked more like a pig than a bear”. The typical Wild West cowboy was “frequently hundreds of miles from the nearest bar or woman”. The TV mute button, which Istel considers “one of the world’s great inventions”, gets a mention.

Istel aims for objectivity and is a stickler for accuracy. But given that even reputable sources will disagree on certain points, it’s a difficult challenge. “The answer is, you do the best you can,” Istel said.

The museum’s official season runs during the cooler months. From the day after Thanksgiving (the fourth Thursday in November) through the end of March, visitors can join a 15-minute tour led by a volunteer docent, watch a short video about the museum or grab a bite at the small restaurant. During the rest of the year, the museum is open, but only for self-guided tours.

View image of Etched by hand, the panels at the Museum of History in Granite portray everything from the Bing Bang to the Moon landing (Credit: Credit: Anne Burke)

Istel’s property is also dotted with pieces of art and architecture that seemingly have little to do with anything, but add a bit of absurdist fun. A 25ft section of the original spiral staircase from the Eiffel Tower rises incongruously into the desert sky. A bronze sculptural replica of Michelangelo’s ‘Arm of God’, from the painting on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, acts as the gnomon of a sundial.

There is also a hollow, 21ft pink-granite pyramid, inside which is a metal plaque that marks the centre of the world. A $2 fee, on top of the museum’s regular admission of $3 per person, entitles visitors to a certificate attesting to having stood on the exact spot.

The tallest and most striking element on the property is a little white chapel that sits poetically atop a 35ft earthen hill. Istel is not particularly religious, but he thought it fitting to install the chapel if for no other reason than to “keep us on our good behaviour”.

Istel and Lee live alongside the museum in a lovely, light-filled house with big windows that look out on chocolate-coloured mountains. There’s a library stocked with leather-bound volumes and a piano that Lee plays. Istel serves guests fizzy water – wine if they prefer – in crystal glasses.

View image of Istel believes that self-acquired knowledge is one of the best forms of education (Credit: Credit: Anne Burke)

Istel has made plans in his estate for the museum and all that surrounds it. Yet – as he approaches his 90th birthday – he has no plans of slowing down.

The museum is far from complete. Dozens of blank granite panels await text and illustrations. There is also a new freeway sign to be installed, and the never-ending task of keeping up with online reviews. Istel responds to each – even the mean ones – with unfailing politeness.

May distant descendants, perhaps far from planet Earth, view our collective history with understanding and affection

If residents of other worlds do indeed visit the museum one day, Istel would not be particularly surprised. He believes that humans will one day colonise other planets and eventually stars, so it’s not inconceivable that they could, at some point, return to Earth. One granite panel bears a big question mark, along with this inscription:

“May distant descendants, perhaps far from planet Earth, view our collective history with understanding and affection.”

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

BBC Travel – Adventure Experience

0 notes

Text

Research Paper

Andrew Hill

Professor Lillich

October 29, 2018

Vegetarian? Let’s learn more.

Do you really know what being vegetarian is and do you know if it’s healthier for you and why people choose it? Today in my paper we are going to break down what being vegetarian is and the benefits that come with it, and we will also go over some concerns that vegetarians have when it comes to their diet. When you look up vegetarian in google, the definition will state “a person who does not eat meat, and sometimes other animal products, especially for moral, religious, or health reasons.” Vegetarianism has the side of science when it comes to health, you will find out more why science is on the vegetarian side later in my paper.

First lets go over why people choose to be a vegetarian and not a tradition diet. There is many different reasons why people choose to be vegetarian. One of the main reasons is that some people don’t like to eat animals that were once alive. They just do not like the thought of eating them and the thought of killing them to eat, but unfortunately that is the way life is, and the people that kill them for us to eat and doing their roles and it’s not wrong, just some people choose differently and that is fine because being vegetarian is not a bad choice.

Another reason is some peoples religions require vegetarianism or strongly advocate towards it. Vegetarianism is strongly linked in religions that originated in ancient India, the three religions that do is Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism. Jainism is the only one where vegetarianism is mandatory for everyone, in Hinduism and Buddhism it is strongly advised by influential scriptures and religion authorities but they do not make you choose a vegetarian diet.

Lastly, people choose to be a vegetarian because it is a healthier lifestyle and has so many health benefits. There has been large health studies held in Germany and England that have shown that being vegetarian makes you 40 percent less likely to develop cancer when comparing to meat-eaters. In the United States, they have found similar data that vegetarians are less likely to develop cancer. This is because vegetarians avoid animal products and a lot of animal fat can be linked to cancer, and vegetarians get more vitamins, phytochemical, and fibers that help prevent cancer, and also they did blood analysis of vegetarians blood and the analysis showed that they have much higher levels of “natural killer cells”, these cells are specialized white blood cells that attack cancer cell and so this makes vegetarians less likely to develop cancer when they have more white blood cells trained to fight off the cancer.

Now that you know the basics of what a vegetarian is, and why people choose it, it is time to break down what really being a vegetarian is and all the types of vegetarian diets. First you should know their is many different types of vegetarian diets and I will talk to you about them and what makes them different compared to other vegetarian diets. A “lacto-ovo vegetarian” consumes milk and dairy foods, eggs, grains, fruits, vegetables, beans, nuts and seeds. This type of vegetarian diet is the easiest to follow because it only takes away meat, fish, and poultry. The next step up is a small change and it is called a “lacto-vegetarian” and it follows all the same rules except this type does not eat eggs. When someone is a “true vegetarian” and truly does not touch anything to do with animals, they are called “vegan” and they don’t eat meat, milk and dairy products, lard, gelatin and any foods with ingredients from an animal source, and some vegans eat honey and some do not.

A vegetarian diet has so many health benefits that most people don’t know about. Earlier I told you about how it reduces cancer risk and now I will share with you more of the health benefits that come with being vegetarian. Choosing a vegetarian diet also helps prevent heart disease. We get most saturated fats from animals and animals are also our only source of cholesterol in the diet. Vegetarians do not eat meat or animal products so it eliminates these risky products from your diet and those fats and cholesterol aren’t the best for your heart, so it helps prevent against heart disease. Another way the vegetarian diet is good for your heart is that it lowers your blood pressure. In 1900s some nutritionists found and noted that people who chose a vegetarian diet all had lower blood pressure from before they started, no matter the sodium levels in the vegetarian diet. Nobody knows exactly why a vegetarian diet helps lower your blood pressure but we have a good clue and that is cutting out meat, dairy products, and extra fats reduces the bloods thickness, and that would bring down your blood pressure because if your blood could flow like water and not like hand soap, your heart wouldn't have to work so hard to process it around your body.

Another health benefit that comes with being vegetarian is that in some cases it can prevent or reverse diabetes. Non-insulin-dependent (adult-onset) diabetes can really be controlled and in some cases eliminated through a low-fat, vegetarian diet, and of course with regular exercise. This works because with a diet like this that is low in fat and high in fiber and that also have complex carbohydrates, it allows the insulin to work much better and act way more efficient. Unfortunately a vegetarian diet cannot eliminate the need for insulin in people with insulin-dependent type 1 diabetes. Although it can help reduce the amount of insulin needed for that person with type 1 diabetes that is insulin dependent.

The next health benefit that vegetarians have is that’s been shown to reduce a persons chance of forming kidney stones and gallstones. This has been shown because urinary tract stones have three main components and those are calcium, oxalate, and uric acid. Non vegetarian diets that are high in protein, especially animal protein, cause the body to excrete more calcium, oxalate, and uric acid, so in this case if you choose a vegetarian diet you will cause your body to excrete less amounts of calcium, oxalate, and uric acid and that means you will have a less chance of having kidney stones or gallstones.

A unique health benefit that vegetarians have is that for some reason their has been studies that have shown that it can help with asthma. The study was held in Sweden in 1985 and they found that practicing a vegetarian diet for a full year has helped people with asthma not need as much medication, and also found that the vegetarian diet helps make the severity of asthma attacks decrease.

When becoming a vegetarian, people have all types of concerns about how you will get all the essential nutrients your body needs to grow and live. A lot of times people forget that protein comes from other things and not only meat. Any normal variety of plant foods has enough protein that the body needs. Vegetarian diets clearly do have a little less protein compared to a meat-eaters diet, but most people don’t know that it is an advantage. Diets that have a lot of animal protein have been linked to kidney stones, osteoporosis, heart disease, and some cancers. A vegetarians diet focused on whole grains, beans, and vegetables has enough protein without having to much like most meat-eaters get. They also wonder how we will get calcium, calcium is not hard to find in a vegetarian diet, many dark green leafy vegetables and beans are loaded with calcium and also strangely some orange-juices and non-dairy milks contain calcium. Vitamin B12 is another issue for vegans. This vitamin is found mainly in animals and so if you are a vegan, this would be a problem but it is easy to deal with. Small amounts of vitamin B12 may be found in plant products because bacterial contamination can happen and get into the plant products. Although that small amount is not a reliable source, and vitamin B12 is needed for people to meet nutritional needs. Vegans usually solve this problem by taking a vitamin B12 pill that is made for vegetarians that need their vitamin B12.

Sources

Gittamier, Mary Jane. “Vegetarian Life.” 27 Oct. 2018.

Thorogood, Anonymous M. “Vegetarian Foods: Powerful for Health.” The Physicians Committee, 15 Aug. 2011, www.pcrm.org/health/diets/vegdiets/vegetarian-foods-powerful-for-health.

Wolfran, Taylor. “Vegetarianism The Basic Facts.” Eat Right. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics., 1 Oct. 2018, www.eatright.org/food/nutrition/vegetarian-and-special-diets/vegetarianism-the-basic-facts.

0 notes

Text

What it feels like to be enlightened

Flickr Creative Commons/Hartwig HKD

Mysticism has been on my mind again lately, in part because of the success of Why Buddhism Is True by my friend Robert Wright. During a mystical experience, you feel as though you are encountering absolute reality, whatever the hell that is. Wright explores the possibility that meditation can induce powerful mystical states, including the supreme state known as enlightenment.

I ventured into this territory in my 2003 book Rational Mysticism. I interviewed people with both scholarly and personal knowledge of mystical experiences. One was the Buddhist teacher Stephen Batchelor, a profile of whom I just posted. Another was a professor of philosophy who prefers to remain anonymous. I’ll call him Mike. I didn’t tell Mike’s story in Rational Mysticism, but I’m going to tell it now, because it sheds light on enlightenment.

Before I met Mike, I read an article in which he claimed to have achieved a mystical state devoid of object, subject, or emotion. It occurred in 1972, while he was on a meditation retreat. “I had been meditating alone in my room all morning,” Mike recalls,

when someone knocked on my door. I heard the knock perfectly clearly, and upon hearing it I knew that, although there was no “waking up” before hearing the knock, for some indeterminate length of time prior to the knocking I had not been aware of anything in particular. I had been awake but with no content for my consciousness. Had no one knocked I doubt that I would ever have become aware that I had not been thinking or perceiving.

Mike decided that he had experienced what the Hindu sage Shankara called “unconsciousness.” Mike’s description of his experience, which he called a "pure consciousness event,” baffled me. Can this be the goal of spiritual seeking? To experience not bliss or profound insights but literally nothing? And if you really experience nothing, how can you remember the experience? How do you emerge from this state of oblivion back into ordinary consciousness? How does an experience of nothing promote a sense of spirituality?

Mike, it turned out, lived in a town on the Hudson River not far from my own. Like me, he was married and had kids. I called and told him I was writing a book about mysticism, and he agreed to meet me to talk about his experiences. On a warm spring day in 1999 we met for lunch at a restaurant near his home. Mike had a ruddy complexion, thinning hair, and a scruffy, reddish-brown beard. Eyeing me suspiciously he said, “A friend of mine warned me that I shouldn’t talk to people like you.” His friend’s advice is sound, I replied, journalists are not to be trusted. Mike laughed and seemed to relax (which of course was my insidious intent).

Grilling me about my attitudes toward mysticism, he compulsively completed my sentences for me. I said that when I first heard about enlightenment, my impression was that it changes your entire personality, transforming you into... “A saint,” Mike said. Yes, I continued. But now I suspected that you can have very deep mystical awareness and still be... “An asshole,” Mike said. “So that's what you want to think about?” he continued, scrutinizing me. “You want to think about whether enlightenment is really all that cool?”

Mike’s edginess lingered as he began telling me about himself. Especially when instructing me on fine points of Hinduism or other mystical doctrines, he spoke with an ironic inflection, mocking his own pretensions. His fascination with enlightenment dated back to the late 1960’s, when he was an undergraduate studying philosophy and became deeply depressed. He tried psychotherapy and Zen, but nothing worked until he started practicing Transcendental Meditation in 1969. Introduced to the west by the Indian sage Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, Transcendental Meditation involves sitting with eyes closed while repeating a phrase, or mantra.

“It was magic, hugely effective,” Mike said of TM. Over the next decade, he became involved in the TM organization. “I hung out with Maharishi a fair amount.” He distanced himself from the TM movement after it began offering seminars on occult practices, notably levitation. “I did that technique,” Mike said. “It was an interesting experience, but it sure as hell wasn't levitating.” The Maharishi also proposed that the brain waves emitted by large groups of meditators could reduce crime rates and even warfare. “I thought it was silly,” Mike said, “and I didn't want to be identified with it.”

Mike pursued a doctorate in philosophy in the early 1980’s so that he could defend intellectually what he knew to be true experientially: Through meditation we can gain access to realms of reality that transcend time and space, culture, and individual identity. Yes, as William James documented, mystical visions vary, but mystics from many different traditions, including Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism, Taoism, and Judaism, have described experiences that are devoid of content. These are what Mike calls pure consciousness events.

“If you say all crows are black, all it takes is one white crow and you've blown the thesis,” Mike said. “We got a whole range of these white crows.” Mike noted that if he and I described the restaurant in which we were eating, our descriptions would almost certainly diverge, even though we were seeing the same restaurant. Shankara, Meister Eckhart, and the Zen master Dogen described their pure consciousness events in different ways, but they were experiencing the same deep reality.

Our conversation then took an unexpected turn. I said I was mystified by the notion that enlightenment is nothing more than a “pure consciousness event.”

“That's not enlightenment!” Mike interrupted. He stared at me, and when he continued he spoke in clipped, precise tones, as if trying to physically embed his words in my brain. The pure consciousness event is just a stepping-stone, at best, to true enlightenment. Pure consciousness events and other mystical states are “fascinating, interesting, very cool things. But they are shifts in perception, not shifts in the structure of perception. And that's, I think, when things get very interesting, when structural shifts take place.”

Mike held up his water glass. Normally, he said, when you look at an object like this glass, you sense a distinction between the object and yourself. He set the glass down, grabbed my pen from my hand, and scribbled on his napkin. He sketched the glass, complete with ice cubes and lemon, and an eyeball staring at the glass. During a “pure consciousness event,” the object vanishes and only consciousness remains, Mike said, drawing an X through the glass.

There is a higher state of awareness, however, in which consciousness becomes its own subject and object. “It becomes aware of itself. And there is a kind of, not solipsism exactly, but a reflexivity to consciousness.” Bending over his napkin again, Mike drew an arrow that emerged from the eyeball and curled back toward it. “It's like there is a self-awareness in a new sort of way.”

Our Caesar salads arrived. As the waiter grated parmesan cheese over our bowls, Mike told me about the final state of enlightenment, which he called the “unitive mystical state.” In this state, your awareness enfolds not just your individual consciousness but all of inner and outer reality. “What you are, and what the world is, is now somehow a unit, unified.” Mike drew a circle around the eyeball and the glass.

Are there any levels beyond this one? I asked, pointing to the circle. “I don’t know,” Mike answered, looking genuinely perplexed. “I haven't read about it, if there is. Some people want to say that there are, beyond here, experiences. But I'm not convinced of that.”

So are you enlightened? I asked. “As I understand it, yes,” Mike replied without hesitating. He had been expecting the question. He scrutinized me, looking for a reaction. “See, that's tricky. I just gave you a pretty tricky answer. Because I define this stuff pretty narrowly.” He might not be enlightened according to others’ definitions, but according to his definition he reached enlightenment in 1995.

Mike hastened to disabuse me of various myths about enlightenment. When he started meditating in the late 1960’s, he believed that enlightenment “was all going to be fun and games.” He emitted a mock-ecstatic cry and waved his hands in the air. “Just heaven,” he added, snapping his fingers, “like that.” But enlightenment does not make you permanently happy, let alone ecstatic. Instead, it is a state that incorporates all human emotions and qualities: love and hate, desire and fear, wisdom and ignorance. “The ability to hold opposites, emotional opposites, at the same time is really what we're after.”

Enlightenment is profoundly satisfying and transformative, but the mind remains in many respects unchanged. “You're still neurotic, and you still hate your mother, or you want to get laid, or whatever the thing is. It's the same stuff; it doesn't shift that. But there is a sort of deep”--he raised his hands, as if gripping an invisible basketball, and uttered a growly, guttural grunt—“that didn't used to be there.”

Far from fostering humility and ego-death, Mike added, mystical experiences can lead to narcissism. Enlightenment is “the biggest power trip you can imagine” and an “aphrodisiac.” When you have a profound mystical revelation, “you think you're God! And that is going to have a hell of an effect on people… All the little young ladies run around and say, ‘He's enlightened! He's God!’”

Have you struggled with that problem yourself? I asked. “Sure!” Mike responded. When he first began having mystical experiences in 1971, he was on top of the world. “And after a while they sort of fall away, and you realize you're the same jerk you were all along. You just have different insights.” Mike resumed psychotherapy in 1983 to deal with some of his personal problems. “It was the best thing I ever did. Been in it ever since.” (What would it be like, I wondered, to be the therapist for someone who believes he is enlightened?)

Contrary to what some gurus claim, enlightenment does not give you answers to scientific riddles such as the origin of the universe, or of conscious life, Mike said. When I asked if he intuits a divine intelligence underlying reality, he shook his head. “No, no.” Then he reconsidered. He sees ultimate reality as timeless, featureless, Godless, and yet he occasionally feels that he and all of us are part of a larger plan. “I have a sense that things are moving in a certain direction, well beyond anybody's real control.” Maybe, he said, just as electrons can be described as waves and particles, so ultimate reality might be timeless and aimless—and also have some directionality and purpose.

Evidently dissatisfied with his defense of enlightenment—or sensing that I was dissatisfied with it--Mike tried again. He has an increased ability to concentrate since he became enlightened, he assured me, and a greater intuitive sense about people. “I can say this without hesitation: I would rather have these experiences than not,” he said. “It's not nothing.”

A few days later, I went running in the woods behind my house. After I arrived huffing and puffing at the top of a hill, I flopped down on a patch of moss to catch my breath. Looking up through entangled branches at the sky, I ruminated over my lunch with Mike. What impressed me most about him was that he somehow managed to be likably unpretentious, even humble, while claiming to be enlightened. He’s no saint or sage, just a normal guy, a suburban dad, who happens to have achieved the supreme state of being.

But if enlightenment transforms us so little, why work so hard to attain it? I also brooded over the suggestion of Mike and other mystics that when you see things clearly, you discover a void at the heart of reality. You get to the pot at the end of the spiritual rainbow, and you don’t find God, or a theory of everything, or ecstasy. You find nothing, or “not nothing,” as Mike put it. What’s so wonderful and consoling about that? Does seeing life as an illusion make accepting death easier? I must be missing something.

I was still flat on my back when a shadow intruded on my field of vision. A vulture, wingtips splayed, glided noiselessly toward me. As it passed over me, just above the treetops, it cocked its wizened head and eyed me. “Go away!” I shouted. “I’m not dead yet!”

NOW WATCH: A Navy SEAL explains what to do if you're attacked by a dog

from Feedburner http://ift.tt/2zRMGHH

0 notes

Text

Role of Religions In Promoting Non-Violence: Islam’s Valuable Resources For Peacemaking By Sultan Shahin

Mr. President, Ladies and gentlemen,

I would like to begin my talk with an entreaty that Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) so earnestly used to make in his prayers several times every day:

“O God, You are the original source of Peace; from You is all Peace, and to You returns all Peace. So, make us live with Peace; and let us enter paradise: the House of Peace. Blessed be You, our Lord, to whom belongs all Majesty and Honour!”

Throughout history religions have played a rather ambivalent role in promoting both peace and violence. They have been used and misused by their supposed followers in both ways. Religious postulates from all religions have been misinterpreted in a variety of ways to promote violence rather than non-violence and peace, though establishing peace and harmony in society is in a sense the primary purpose of every religion. As His Holiness The Dalai Lama once said, answering a question, relating to Islam and violence: “(People of) all religions are violent. Even Buddhists!” [i] Indeed even the beautiful and thought-provoking Buddhist concept of “emptiness” has been misinterpreted to promote violence.[ii] The octogenarian leader of Jamaat-e-Islami in Pakistan, Syed Ali Shah Gilani quotes not only the Quran but even the Hindu scripture Bhagwat Gita to justify terrorism in the Kashmir valley. [iii] And yet, all scholars are agreed that religion provides “valuable resources for peacemaking”, [iv] and it is possible to give examples of how religions or peace-activists from within various religions have utilised these resources to promote peace and non-violence. “Within each of the great religions there is “a moral trajectory challenging adherents to greater acts of compassion, forgiveness and reconciliation”, Scott Appleby wrote, an “internal evolution” that offers hope for religiously inspired peacemaking.” [v]

One can indeed make this point without fear of contradiction on the basis of the teachings of all religions. Theologian Mark Juergensmeyer [vi] has identified three major aspects of non-violence within nearly all world religions:

a) Reverence for life and desire to avoid harm,

b) The ideal of social harmony and living peacefully with others,

c) The injunction to care for the other, especially for the one in need.

Distinguished scholar and peace activist David Cortright has tried to illustrate these points with examples from several religions. [vii] Illustrating the first point he says: All major religions have imperatives to love others and avoid taking of human life. In Buddhism, the rejection of killing is the first of the Five Precepts. Hinduism declares “the killing of living beings is not conducive to heaven.” [viii] Jainism rejects the taking of any form of life: “if someone kills living things…his sin increases.” [ix] The Quran states “slay not the life that God has made sacred.” [x] The Bible teaches you shall not murder.” [xi]

The second point is illustrated by the ideal of social harmony and living peacefully with other being frequently emphasized in the Old Testament and the Qur’an. Third is the willingness to sacrifice and suffer for the sake of expiating sin and avoiding injury to others, which is common in the Abrahamic traditions.

The third universally accepted norm at the core of all religious traditions is the injunction to care for the other, especially for the one in need. Cortright says: “Buddhism and Hinduism are founded on principles of compassion and empathy for those who suffer. Islam emerged out of the Prophet’s call to restore the tribal ethic of social egalitarianism and to end the mistreatment of the weak and the vulnerable. In the New Testament Jesus is depicted throughout as caring for and ministering to the needy. Compassion for the stranger is the litmus test of ethical conduct in all religions. So is the capacity to forgive, to repent and overcome past transgressions. The key to conflict prevention is extending the moral boundaries of one’s community and expressing compassion towards others.”[xii]

These factors apart, Cortright also finds other valuable resources. He writes: “There are many other religious principles that provide a foundation for creative peacemaking. Nonviolent values pervade the Eastern religious traditions of Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism and echo through the Gospel of Jesus. The religious emphasis on personal discipline and self-restraint also has value for peace-making. It provides a basis for constraining the impulses of vengeance and retaliation that arise from violent conflict. The power of imagination, to use John Paul Lederach’s term [xiii] , is necessary to envision a more just and peaceful order, to dream of a society that attempts to reflect religious teaching.” [xiv]

Clearly all religions from ancient eastern religions like Taoism to Buddhism, Jainism Hinduism, and Abrahamic religions like Judaism, Christianity and Islam, all provide us with resources to work for peace and non-violence. Indeed, followers of all these religions and many of their sects have all worked at various times in their own ways in establishing peace. It is not possible in the time available to us here to make a detailed study but a lot of material is available in books and essays published in research journals on the subject.

Mr. President,

I would like to take this opportunity to make a special mention of Islam’s quest for peace and the possibility of using Islamic resources for peace-making and for a peaceful quest for justice. Unfortunately in our time a growing number of people look at Islam with fear and are considering it a violent religion or at least a religion that allows violence for its expansion. Nothing could be further from the truth. But we cannot blame people for fearing Islam as Muslim people in several parts of the world are indeed involved in wars and terrorism while Muslim religious scholars are not doing enough to stop these nefarious activities nor are they even condemning these war-mongers and seeking to delink Islam from them.