#tshombe

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

⛧💋

#tshombe#aesthetic#gothgoth#gothic#original photographers#punk aesthetic#punk rock#underground#vhs aesthetic#vintage fashion#goth model#90s goth#hardcore punk#punk music

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

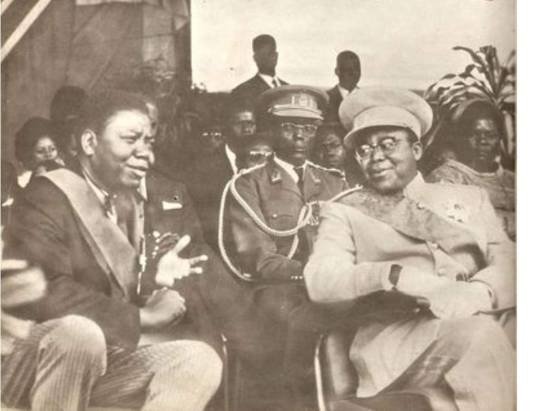

RDC-histoire : Le 13 octobre 1965, le jour où Joseph Kasavabu a crée un incident qui précipitera sa chute en faveur de Mobutu

Le 13 octobre 1965, devant les 2 Chambres réunies, le Président Kasa Vubu révoque son Premier ministre, Moise Tshombe. Comme en sept 1960, Kasa Vubu venait de créer un deuxième incident qui poussera le Général Joseph Désiré Mobutu à faire son deuxième coup d’Etat un mois plus tard (novembre 1965), fatigué, dira-t-il, d’assister aux querelles des politiciens. Ce jour du 13 octobre, le Président…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The Antagonism between the White Settlers and Imperialism

There was nothing new in all this, however. The most difficult struggles of the imperialist countries since the 18th century had not been with the natives in their colonies but with their own settlers. And it should not be forgotten that if England is a second-class power today, this is due to her defeat in a conflict of this type and the subsequent founding of the United States. Without this, North America would now be an ex-colony of Red Indians recently promoted to independence and therefore still exploited by England.

Marx and Engels did not fail to make references here and there to ‘white settlers’, ‘poor whites’, etc, although during the period in which they lived the problem was not acute. But Lenin came out strongly in favour of the Boers in 1900, just as Mao Tse Tung’s China recently gave unexpected support to Biafra and its mercenaries. Finally, the exaggerated schematization in which Marxism was confined after Lenin’s death meant that no place could be made for this uncomfortable ‘third element’ in the noble formulas of the ‘people’s struggle against financial imperialism’.

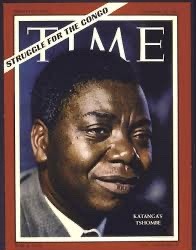

Instead of scientific analysis, we have tenacious myths that no fact, however brutal, will ever shake. This makes for grave misunderstandings and prevents any true dialogue between revolutionary Marxism and the decolonized peoples. To take a recent example, even the most informed Marxists did not hesitate to accept the popular version according to which Tshombe was the puppet of the Union Minière, the Belgian trust companies and international imperialism. Nothing could be further from the truth. Tshombe never represented financial capitalism. He represented the white settlers. And it was in this capacity that he was detested and rejected throughout Africa. For this same reason he was the public enemy number one of the trust companies and of Belgian-American imperialism.

Of course, if by Union Minière one means the local staff of the Katanga company, there is nothing to prevent one from saying that Tshombe was their man. Like the Belgian civil servants and army officers, these people represented the parent country before the independence of the Congo, and as such they were on the other side of the fence. The settlers had always called them ‘n*****-lovers’, the most contemptuous epithet in their vocabulary. But individually, each of them prepared for retirement in the colony, some by buying a share in a plantation, others by investing in real estate, etc. When the umbilical cord linking them to the home country was suddenly severed during the independence troubles, they went over en masse to the settlers’ side.

And what more could these local managers and administrators of the Union Minière ask for? From mere agents, obliged to telephone to the head office in Brussels before they took the slightest decision, with Tshombe and the secession of Katanga they became, from one day to the next, the veritable bosses of the company. And if during the reign of Tshombe the Union Minière was forbidden to distribute the slightest dividend, this did not displease these local men, who had no reason to worry about enriching Belgian shareholders and on the contrary every reason to welcome the accumulation of profits on the spot, which would improve the firm’s potential and hence their own position.

But if by Union Minière one means the Belgian monopoly holding that was behind the Katanga plant, i.e. the Belgian bank La Société Générale, then things become quite different. For them, for Belgian high finance, and therefore for international imperialism, Tshombe was the man to be eliminated, and they ended up by attacking him physically—first in 1962–3 at Elisabethville, under the flag of the United Nations troops, a second time in 1967 by sending anti-Castro Cuban pilots to bomb his mercenaries in Bukavu, and finally the third time by sending a cia agent to kidnap him personally and deliver him to Algiers.

White-Settler Colonialism and the Myth of Investment Imperialism - Arghiri Emmanuel

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Patrice Lumumba was the first elected Prime Minister of the Congo. He ascended to power in the Congo on June 30, 1960, the date of Congo’ s independence from Belgium. Within ten weeks of being elected, Lumumba’s government was deposed in a coup. He was subsequently imprisoned and assassinated on January 17, 1961 by Western powers (United States, Belgium, France, England and the United Nations) in cahoots with local leaders such as Moise Tshombe and Joseph Desire Mobutu.

Lumumba is a member of the Tetela ethnic group. He was born on July 2, 1925, in Katako-Kombe in the Sunkuru district of the Kasai Province. Growing up, Lumumba attended a Protestant Missionary school as well as a Catholic missionary school and became a part of the educated elite called évolués. Lumumba contributed to the Congolese press through poems and other writings. His occupations included a postal clerk in Kinshasa and an accountant in Kisangani. Lumumba’s organizational involvement were varied. He served as head of a trade union of government employees, he was active in the Belgian Liberal Party and in 1958, Lumumba founded the Congolese National Movement (MNC in French). Also in 1958, he was invited to the first All-African People’s Conference in Accra, Ghana, organized by Kwame Nkrumah. He met nationalists and pan-africanists from various African countries and became a member of the permanent organization set up by the conference.

Lumumba’s party won national elections in May of 1960 which led to his ascendancy to Prime Minister on June 30, 1960. Read more on Lumumba>>

Lumumba’s Independence Day Speech Lumumba’s Last Letter to his Wife

Reading List Congo My Country by Patrice Lumumba Patrice Lumumba: Fighter for Africa’s Freedom by Patrice Lumumba The Assassination of Lumumba by Ludo De Witte Rise and Fall of Patrice Lumumba by Thomas Kanza Lumumba Speaks: The Speeches and Writings of Patrice Lumumba, 1958-1961 Translated by Helen R. Lane. Ed. Jean Van Lierde

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

Africa Addio

A documentary about the end of the colonial era in Africa, portraying acts of animal poaching, violence, executions, and tribal slaughter. Credits: TheMovieDb. Film Cast: Narrator (voice): Sergio Rossi (archive footage): Jomo Kenyatta Himself (uncredited): Gualtiero Jacopetti Himself (uncredited): Julius Nyerere Himself (uncredited): Moïse Kapenda Tshombe Himself (uncredited): Richard Gordon…

0 notes

Text

Prime Minister Moïse Kapend Tshombe (Tshombé) (November 10, 1919 – June 29, 1969) was a Congolese businessman and politician. He served as the president of the secessionist State of Katanga (1960-63) and as prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (1964-65).

CONAKAT won control of the Katanga provincial legislature in the May 1960 general elections. Congo became an independent republic. He became President of the autonomous province of Katanga. Patrice Lumumba was tasked with forming a national government. Members of his party, the Mouvement National Congolais, were given charge of the portfolios of national defense and interior, despite his objections. The portfolio for economic affairs was awarded to a CONAKAT member, but this was undercut by the positioning of nationalists in control of the Ministry and Secretariat for Economic Coordination. Mines and land affairs were placed under separate portfolios. He declared that this diluting of CONAKAT’s influence rendered his agreement to support the government “null and void”.

His nephew, Jean Nguza Karl-i-Bond, served as prime minister (1980-81). #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

0 notes

Text

The Congo Crisis: A Tale of Western Intervention.

Patrice Lumumba, Joseph Kasavubu, and Moïse Tshombe marked the independence for the Democratic Republic of Congo by the powerful yet conflicting visions. Their divergent goals and subsequent clashes laid a fragile and tumultuous foundation for the newly independent state. This fragile foundation was further destabilized by the actions of Joseph Mobutu, whose rise to power was built on the…

0 notes

Text

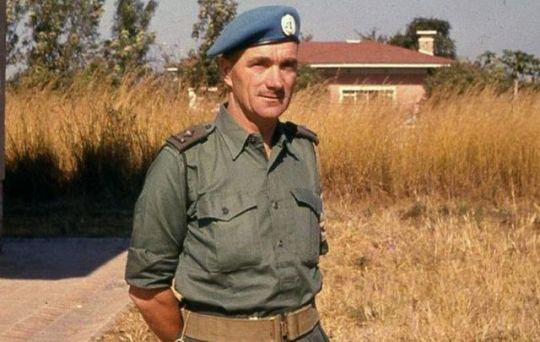

The Brave Peacekeepers of Jadotville

CrystalPlanet: The Brave Peacekeepers of Jadotville

The battle known as the Siege of Jadotville, is an almost unbelievable story of grit, leadership, of unwavering loyalty and courage, of calm, and of extraordinary strategy and tactics; especially in the face of deceit, death, incompetence and betrayal. If you haven’t watched the 2016 movie by the same name, you should. Prior to 1959, Belgium held control of the Congo, with exclusive rights on…

View On WordPress

#Belgians#brave#Commandant Patrick “Pat” Quinlan#Congo#Elizabethville#French mercenaries#Ireland#Irish army#Jadotville#Katanga#Lumumba#Shrutin Shetty#strategy#supplies#Tshombe#UN peacekeeping forces

0 notes

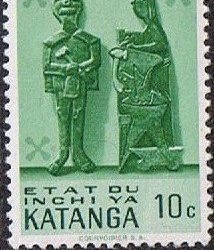

Photo

For a brief time in the early 1960s, the Province of Katanga declared its independence from the (also newly independent) Republic of Congo (Congo-Léopoldville, what was Belgian Congo and what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo) and called itself the State of Katanga. It was never recognized internationally, and even internally was wracked with instability and dissension. The UN eventually stepped in in 1963 and Katanga remains a part of the DRC.

Stamp details: Stamps on top: Issued on: March 1, 1961 From: Élisabethville, State of Katanga MC #52, 57, 64

Issued on: July 8, 1961 From: Élisabethville, State of Katanga MC #66

Recognized as a sovereign state by the UN: No Claimed by: Democratic Republic of Congo Member of the Universal Postal Union: No

#Katanga#State of Katanga#État du Katanga#Inchi Ya Katanga#Republic of Katanga#Democratic Republic of Congo#DRC#stamps#philately#April 6#Province du Katanga#Katanga Province#Shaba Province#Republic of Congo-Léopoldville#Moïse Tshombe

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

love long existed before us or the night sky ever felt its fire before men worshiped the sun it is the breath of all things

—Tshombe Sekou

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

The State of Katanga[a] also sometimes denoted as the Republic of Katanga, was a breakaway state that proclaimed its independence from Congo-Léopoldville on 11 July 1960 under Moise Tshombe, leader of the local Confédération des associations tribales du Katanga (CONAKAT) political party. [...] The Katangese secession was carried out with the support of Union Minière du Haut Katanga, an Anglo-Belgian mining company, and a large contingent of Belgian military advisers.[2] An army the government called the Katanga Gendarmerie, raised by the Tshombe government, was initially organised and trained by Belgium and subsequently, mercenaries of various nationalities.[3] [...] In 1906, the [Anglo-Belgian] Union Minière du Haut-Katanga (UMHK) company was founded and was granted the exclusive rights to mine copper in Katanga.[4][...] In January 1959, it was announced that Belgium would grant independence to the Congo in June 1960. Starting in March 1960, the UMHK began to financially support CONAKAT and bribed the party leader, Moïse Tshombe, into advocating policies that were favorable to the company.[5] [...]

A coalition of CONAKAT politicians and Belgian settlers had made an attempt shortly before that date to issue their own declaration of independence in Katanga, but the Belgian government opposed their plans. CONAKAT was especially concerned that the emerging Congolese government under prime minister Patrice Lumumba would dismiss its members from their positions in the Katangese provincial government and replace them with his supporters.[6]

On the evening of 11 July, CONAKAT leader Moïse Tshombe, accusing the central government of communist leanings and dictatorial rule, announced that Katanga was seceding from the Congo. To assist him, the UMHK gave Tshombe an advance of 1,250 million Belgian francs [5]

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝕿𝖘𝖍𝖔𝖒𝖇𝖊 𝕲𝖗𝖊𝖆𝖙 💋

#tshombe#aesthetic#gothgoth#gothic#original photographers#punk aesthetic#underground#punk rock#vhs aesthetic#vintage fashion#heavy metal#90s grunge#misfits#70s punk#hardcore punk#vintage aesthetic#vintage rock#vintage

1 note

·

View note

Text

RDC-histoire : Le 13 octobre 1965, le jour où Joseph Kasavabu a crée un incident qui précipitera sa chute en faveur de Mobutu

Le 13 octobre 1965, devant les 2 Chambres réunies, le Président Kasa Vubu révoque son Premier ministre, Moise Tshombe. Comme en sept 1960, Kasa Vubu venait de créer un deuxième incident qui poussera le Général Joseph Désiré Mobutu à faire son deuxième coup d’Etat un mois plus tard (novembre 1965), fatigué, dira-t-il, d’assister aux querelles des politiciens. Ce jour du 13 octobre, le Président…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Quote

[T]he philosophy of plunder has not only not been ended, it is stronger than ever. And that is why those who used the name of the United Nations to commit the murder of Lumumba are today, in the name of the defense of the white race, murdering thousands of Congolese. How can we forget the betrayal of the hope that Patrice Lumumba placed in the United Nations? How can we forget the machinations and maneuvers that followed in the wake of the occupation of that country by UN troops, under whose auspices the assassins of this great African patriot acted with impunity? How can we forget, distinguished delegates, that the one who flouted the authority of the UN in the Congo — and not exactly for patriotic reasons, but rather by virtue of conflicts between imperialists — was Moise Tshombe, who initiated the secession of Katanga with Belgian support? And how can one justify, how can one explain, that at the end of all the United Nations' activities there, Tshombe, dislodged from Katanga, should return as lord and master of the Congo? Who can deny the sad role that the imperialists compelled the United Nations to play?

Che Guevara, At the United Nations, 1964

#quote#quotes#socialism#socialist#communism#communist#marxism#marxist#Leninism#leninist#marxism-leninism#marxist-leninist#che#che guevara#theory#politics#political science#philosophy

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Our greatest freedom rest in our ability to expressively create in response to our reality through poem, prayer, portrait, and all that gives us the potential to release that which rest in the silence of our soul.”

—Tshombe Sekou

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

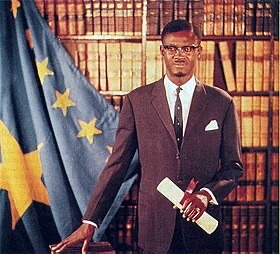

Prime Minister Patrice Émery Lumumba (alternatively styled Patrice Hemery Lumumba; July 2, 1925 – January 17, 1961) was a Congolese politician and independence leader who served as the first Prime Minister of the independent Democratic Republic of the Congo from June until September 1960. He played a significant role in the transformation of the Congo from a colony of Belgium into an independent republic. Ideologically an African nationalist and Pan-Africanist, he led the Congolese National Movement party from 1958 until his assassination.

Shortly after Congolese independence in 1960, a mutiny broke out in the army, marking the beginning of the Congo Crisis. He appealed to the US and the UN for help to suppress the Belgian-supported Katangan secessionists led by Moise Tshombe. Both refused, so he turned to the Soviet Union for support. This led to growing differences between President Joseph Kasa-Vubu and chief-of-staff Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, as well as with the US and Belgium, who opposed the Soviet Union in the Cold War.

He was imprisoned by state authorities under Mobutu and executed by a firing squad under the command of Katangan authorities. Following his assassination, he was seen as a martyr for the wider Pan-African movement. In 2002, Belgium formally apologized for its role in the assassination. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

0 notes