#tracie morris

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Our Souls Have Grown Deep Like Rivers - Black Poets Read their work

2 x CD, Compilation, 2000

#poetry recording#poetry#recording#poets#CD#audre lorde#amiri baraka#nikki giovanni#tracie morris#langston hughes#WEb Dubois#Claude Mckay#James Weldon#Sterling A Brown#gwendolyn brooks#robert hayden#May aAngelou#Derek Walcott#The last poets#Lucille Clifton#Al Young#Sonia Sachez#Ishamel Reed#Wole Soyinka#Wanda Coleman#Gil Scott Heron#Rita Dove#Allison Joseph#Public Enemy

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

Suzy Sureck, Fiely Matias, Zap Mama, Tracie Morris

Martha Cinader speaks with Suzy Sureck, Tony Robles with Fiely Matias, spoken word by Zap Mama, Tracie Morris

Multi-media artist Suzy Sureck, children’s author Fiely Matias, spoken word by Zap Mama, Tracie Morris Subscribe at Spotify Subscribe at Apple Subscribe at Google Martha Cinader speaks from Greenville, SC with Suzy Sureck in Hudson Valley, New York, about her multi-media installation Tread Lightly, which combined music created by the vibrations of tree roots, poetry, art and movement. Tony…

View On WordPress

#children&039;s author#Fiely Matias#Poetry#spoken word#Suzy Sureck#Tracie Morris#United States of Poetry#Zap Mama

0 notes

Photo

Look who bothered coming to work. COLD CASE 5.01 ‘Thrill Kill’

#coldcaseedit#Cold Case#Kathryn Morris#Danny Pino#Tracie Thoms#userthing#tuserheidi#usershale#userkraina#smallscreensource#cinematv#thatsent#userentertainments#dailycolorfulgifs#ours#by SPL#Lilly Rush#Kat Miller#Scotty Valens#userairi#userkayjay#usercats#tvfilmsource#filmtvcentral#tvarchive

181 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝘽𝙡𝙤𝙤𝙙𝙮 𝙈𝙪𝙧𝙙𝙚𝙧 (2000)

#laughingcrass#bloody murder#2000#2000s films#2000s horror#christelle ford#tracy pacheco#david smigelski#patrick cavanaugh#jessica morris#horror movies

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

SPIRITED:

Christmas Good feels lost

Wants to fix cruel marketer

Learns to seek own wants

youtube

#spirited 2022#random richards#poem#haiku#poetry#haiku poem#poets on tumblr#haiku poetry#haiku form#poetic#ryan reynolds#will ferrell#octavia spencer#patrick page#sunita mani#Loren g. woods#tracy morgan#joe tippett#Marlow Barkley#aimee carrero#Andrea anders#Sean anders#john morris#a christmas carol#charles dickens#benj pasek#justin paul#Youtube

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Currently listening to one of my favorite Les Misérables recordings ever. Debra Byrne is such a terrific Fantine, and (dare I say?) I like Gary Morris more as Valjean than Colm Wilkinson. Meanwhile, Philip Quast is amazing (as always). Kaho Shimada, Michael Ball, and Tracy Shayne sound heavenly, especially during In My Life/A Heart Full of Love. And, of course, Anthony Warlow is so passionate as Enjolras that I can clearly envision him in my mind.

#les miserables#les mis complete symphonic recording#musical theatre#musicals#debra byrne#gary morris#philip quast#kaho shimada#michael ball#tracy shayne#anthony warlow#Spotify

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anne Boleyn Readathon

I am taking part in Escape the Readathon this month (you can read more about my involvement in that here), but this weekend (17-19 May) I took a break from my planned TBR and dove head first into into the mass of nonfiction about Anne Boleyn I’ve acquired. For those who don’t know, 19 May is the anniversary of Anne Boleyn’s execution. On that date in 1536, Anne Boleyn, Queen of England, was…

View On WordPress

#Anne Boleyn#Anne Boleyn Readathon#Boleyn Family#Books#Elizabeth Boleyn#Elizabeth I#Elizabeth Tudor#England#English History#George Boleyn#Guidebook#History#Margaret of Austria#Mary Boleyn#Natalie Grueninger#Nonfiction#Queen Claude of France#Readathon#Readathons#Reading Challenges#Sarah Morris#Sylvia Barbara Soberton#Thomas Boleyn#Tracy Borman

1 note

·

View note

Text

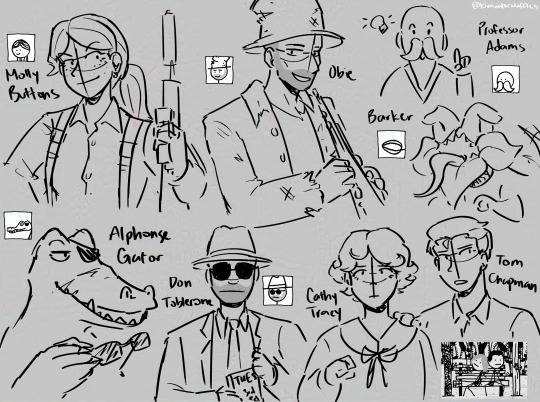

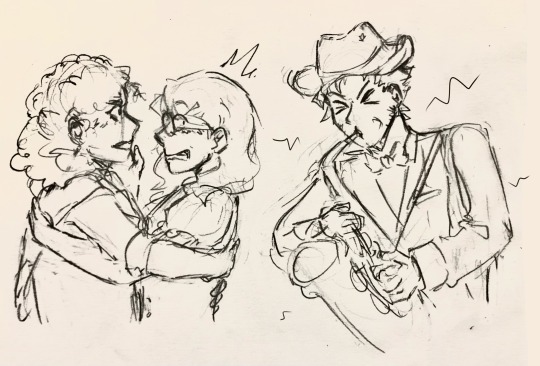

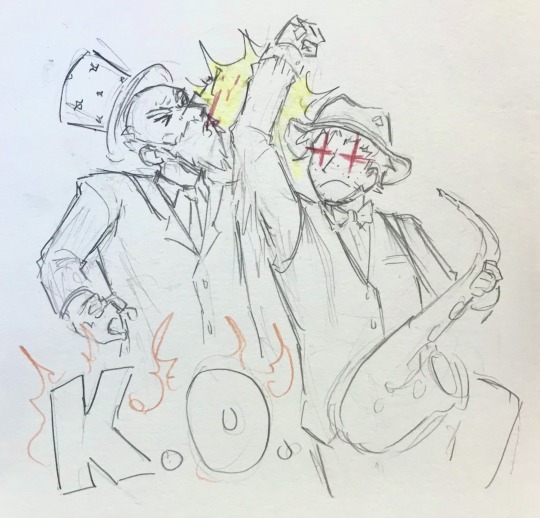

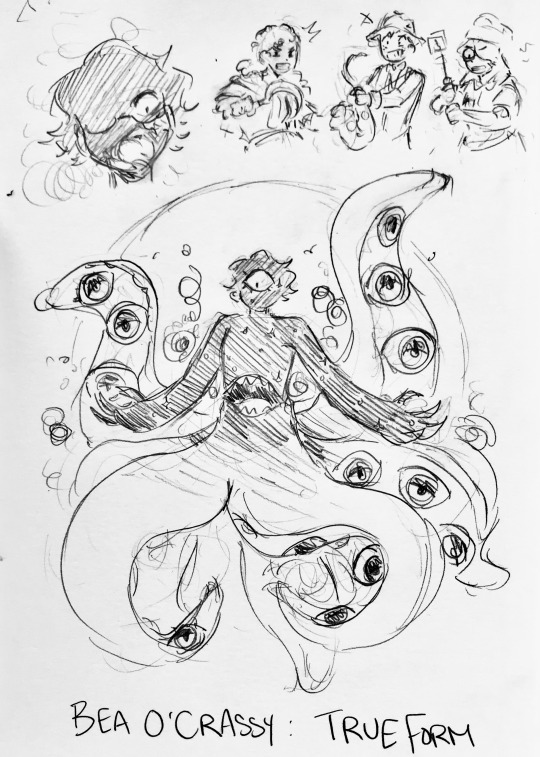

doodles of SoL characters and more stuff of my ocs :3

i've just been stuffing my sketchbook with doodles of the blorbos from my brain LMFAOOOO

sorry to every other social media i have the only place that's getting consistent uploads is toyhouse </3

the alt text will also contain oc names alongide the image descriptions!

#body horror#eyes tw#shadows over loathing#loathingblr#asymmetric#fandom ocs: the loathingverse by asymmetric#kiwi’s scribbles#kiwi’s ocs#oc: tam foolleray#oc: austin dieot#oc: leah fei#dark noël#general bruise#terrence poindexter#margaret dooley#sol jessica#murray morris#sol rufus#sol charles#simone chekhov#sol gabby#molly buttons#obie the oboe hobo#professor adams#sol barker#alphonse gator#don toberlone#cathy tracy#tom chapman#i know probably not a lot of people will see this post but i just like writing alt text actually its fun

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“(317): If you set your screensaver to be a slides show, make sure you remove dick pics first. This lesson 1 of living with your great aunt“

#heartland#crystal#keegan connor tracy#georgie crawley#georgie fleming morris#alisha newton#crystal/georgie#source: texts from last night

1 note

·

View note

Text

NEUTRAL LEANING MASC NAMES ⌇ abner. abram. adam. adrian. alex. alistair. andreas. ariel. arlen. arley. arlo. ash. atlas. auden. august. austin. avery. bailey. baron. barrett. baylor. beauden. bee. bellamy. bennett. blair. blaise. bowen. brayden. brendan. bronson. bryce. byron. caius. caleb. callahan. callan. calloway. callum. camden. cameron. carlin. carson. casey. cassian. chandler. chase. cody. cole. connolly. corban. corwin. cyrus. dallas. damion. damon. daniel. darius. davis. dawson. daylon. denver. desmond. devin. doran. dorian. drew. elian. elias. ellery. ellison. emery. ethan. evan. ezra. fallen. farren. finley. ford. foster. gabriel. gannon. garner. gavin. gentry. graham. greer. griffin. guthrie. harley. harlow. hartley. hayden. henley. henry. heron. hollis. hunter. ian. irving. isaiah. jace. james. jameson. jared. jeremiah. joel. jonah. joran. jordan. jory. josiah. jovian. jude. julian. juno. justus. kalen. kamden. kay. kayden. keaton. kellan. keller. kelly. kendon. kieran. kit. kylan. landry. lane. lennon. leslie. levi. leyton. liam. linden. lowell. luca. madden. marley. marlow. marshall. martin. mason. mathias. mercer. merritt. micah. miles. miller. milo. morgan. morrie. morrison. nate. nevin. nick. nicky. nico. nicolas. noah. noel. nolan. oren. orion. owen. parker. percy. perrin. peyton. pierce. porter. preston. quincy. quinn. reece. reid. reign. rein. remi. remington. renley. riley. river. robin. rollins. ronan. rory. rowan. russell. ryan. rylan. sam. samuel. sawyer. saylor. seth. shiloh. soren. spencer. stellan. sterling. talon. taylor. thaddeus. thane. theo. toni. tracy. tristan. tyrus. valor. warner. wells. wesley. whitten. william. willis. wylie.

NEUTRAL LEANING FEM NAMES ⌇ abigaël. abilene. addison. adrian. ainsley. alexis. and. andrea. arden. aria. ashley. aspen. aubrey. autumn. avery. avian. ayla. bailey. beryl. blair. blaire. blake. briar. brooklyn. brooks. bryce. cameron. camille. casey. celeste. channing. charlie. chase. collins. cordelia. courtney. daisy. dakota. dana. darby. darcy. delaney. delilah. devin. dylan. eden. eisley. elia. ellerie. ellery. ellie. elliot. elliott. ellis. ellory. ember. emelin. emerson. emery. evelyn. ezra. fallon. finley. fiore. florence. floris. frances. greer. gwenaël. hadley. harley. harper. haven. hayden. heike. hollis. hunter. ivy. jade. jamie. jocelyn. jordan. jude. juno. kelly. kelsey. kendall. kennedy. koda. kyrie. lacey. lane. leighton. lennon. lennox. lesley. leslie. lilian. lindsay. loden. logan. lou. lyric. madison. mallory. marinell. marley. mckenzie. melody. mercede. meredith. mio. misha. monroe. montana. morgan. nico. nova. oakley. olympia. owen. page. palmer. parker. pat. paulie. perri. petyon. peyton. phoenix. piper. priscilla. quinn. raven. ray. reagan. reece. reese. remi. remy. riley. rio. river. robin. rory. rosario. rowan. ryan. rylie. sacha. sage. sam. sammy. santana. sasha. sawyer. saylor. severin. shannon. shelby. shiloh. skye. skylar. sloane. sol. soleil. sterling. stevie. sutton. swan. swann. sydney. tatum. taylo. taylor. tracey. valentine. vanya. vivendel. vivian. vivien. wren. wynn. yael.

#pupsmail︰names#name pack#name suggestions#name ideas#name list#fem names#feminine names#masc names#masculine names#neutral names#gender neutral names

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

this is a poll for a movie that doesn't exist.

It is vintage times. The powers that be have decided to again remake the classic vampire novel Dracula for the screen. in an amazing show of inter-studio solidarity, Hollywood’s most elite hotties are up for the starring roles. The producers know whoever they cast will greatly impact the genre, quality, and tone of the finished film, so they are turning to their wisest voices for guidance.

you are the new casting director for this star-studded epic. choose your players wisely.

Previously cast:

Jonathan Harker—Jimmy Stewart

The Old Woman—Martita Hunt

Count Dracula—Gloria Holden

Mina Murray—Setsuko Hara

Lucy Westenra—Judy Garland

The Three Voluptuous Women—Betty Grable, Marilyn Monroe, and Lauren Bacall

Dr. Jack Seward—Vincent Price

Quincey P. Morris—Toshiro Mifune

Arthur Holmwood—Sidney Poitier

R.M. Renfield—Conrad Veidt

278 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zargon awaits beneath The Lost City -- Kevin Glint updates the look of a classic encounter from module B4, first drawn by Jim Holloway:

Quests from the Infinite Staircase (July 16, 2024) will include 5e conversions of 6 D&D/AD&D adventures from the 1980s:

B4: The Lost City by Tom Moldvay (1982, originally for Moldvay's version of Basic D&D)

UK4: When a Star Falls by Graeme Morris (1984, originally for AD&D)

UK1: Beyond the Crystal Cave by Dave J Brown, Tom Kirby, and Graeme Morris (1983, AD&D)

I3: Pharaoh by Tracy and Laura Hickman (1982, AD&D)

S4: The Lost Caverns of Tsojcanth by Gary Gygax (1982, AD&D)

S3: Expedition to the Barrier Peaks by Gary Gygax (1980, AD&D)

#D&D#Dungeons & Dragons#Kevin Glint#Zargon#The Lost City#AD&D#Basic D&D#dnd#D&D 5e#5e#TSR#WotC#Gary Gygax#1980s#Dungeons and Dragons

206 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fred Armisen, cast (2002–13)

Alec Baldwin, 17-time host (1990–2017)

Vanessa Bayer, cast (2010–17)

Candice Bergen, five-time host (1975–90)

Aidy Bryant, cast (2012–22)

Dana Carvey, cast (1986–93)

Chevy Chase, cast and writer (1975–76)

Michael Che, writer (2013–present), cast (2014–present)

Ellen Cleghorne, cast (1991–95)

Billy Crystal, cast (1984–85)

Jane Curtin, cast (1975–80)

Pete Davidson, cast (2014–22)

Rachel Dratch, cast (1999–2006)

Nora Dunn, cast (1985–90)

Jimmy Fallon, cast (1998–2004)

Tina Fey, writer (1997–2006), cast (2000–6)

Will Forte, cast (2002–10)

Janeane Garofalo, cast (1994–95)

Ana Gasteyer, cast (1996–2002)

Bill Hader, cast (2005–13)

Darrell Hammond, cast (1995–2009), announcer (2014–present)

Marcello Hernández, cast (2022–present)

James Austin Johnson, cast (2021–present)

Leslie Jones, cast and, writer (2014–19)

Colin Jost, writer (2005–present), cast (2014–present)

Chris Kattan, cast (1996–2003)

Julia Louis-Dreyfus, cast (1982–85)

Steve Martin, 16-time host (1976–2022)

Kate McKinnon, cast (2012–22)

Tim Meadows, cast (1991–2000)

Seth Meyers, cast (2001–14), writer (2003–14)

Tracy Morgan, cast (1996–2003)

Garrett Morris, cast (1975–80)

John Mulaney, writer (2008–13), six-time host (2018–24)

Mike Myers, cast (1989–95)

Laraine Newman, cast (1975–80)

Don Novello, writer (1978–80 1985–86), cast (1979–80, 1985–86)

Cheri Oteri, cast (1995–2000)

Chris Parnell, cast (1998–2006)

Nasim Pedrad, cast (2009–14)

Jay Pharoah, cast (2010–16)

Joe Piscopo, cast (1980–84)

Amy Poehler, cast (2001–8)

Maya Rudolph, cast (2000–7)

Andy Samberg, cast (2005–12)

Molly Shannon, cast (1995–2001)

Sarah Sherman, cast (2021–present)

Martin Short, cast (1984–85)

Sarah Silverman, cast and, writer (1993–94)

David Spade, writer (1990–91), cast (1990–96)

Cecily Strong, cast (2012–22)

Jason Sudeikis, writer (2003–5), cast (2005–13)

Julia Sweeney, cast (1990–94)

Terry Sweeney, writer (1980–81 1985–86), cast (1985–86)

Kenan Thompson, cast (2003–present)

Christopher Walken, seven-time host (1990–2008)

Kristen Wiig, cast (2005–12), five-time host (2013–24)

Casey Wilson, cast (2008–9)

Bowen Yang, writer (2018–19), cast (2019–present)

Sasheer Zamata, cast (2014–17)

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Whenever you feel alone, just remember that those kings will always be there to guide you. And so will I.

Born to a turbulent family on a Mississippi farm, James Earl Jones passed away today. He was ninety-three years old. Abandoned by his parents as a child and raised by a racist grandmother (although he later reconciled with his actor father and performed alongside him as an adult), the trauma of his childhood developed into a stutter that followed him through his primary school years – sometimes, his stutter was so debilitating, he could not speak at all. In high school, Jones found in an English teacher someone who found in him a talent for written expression, and encouraged him to write and recite poetry in class. He overcame his stutter by graduation, although the effects of it carried over for the remainder of his life.

Jones' most accomplished roles may have been on the Broadway stage, where he won three Tonys (twice winning Best Actor in a Play for originating the lead roles in 1969's The Great White Hope by Howard Sackler and 1987's Fences by August Wilson) and was considered one of the best Shakespearean actors of his time.

But his contributions to cinema left an impact on audiences, too. Jones received an Honorary Academy Award alongside makeup artist Dick Smith (1972's The Godfather, 1984's Amadeus) in 2011. From the end of Hollywood's Golden Age to the dawn of the summer Hollywood blockbuster in the 1970s to the present, Jones' presence – and his basso profundo voice – could scarcely be ignored. Though he could not sing like Paul Robeson nor had the looks of Sidney Poitier, his presence and command put him in league of both of his acting predecessors.

Ten of the films James Earl Jones appeared in, whether in-person or voice acting, follow (left-right, descending):

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964) – directed by Stanley Kubrick; also starring Peter Sellers, George C. Scott, Sterling Hayden, Keenan Wynn, and Slim Pickens

The Great White Hope (1970) – directed by Martin Ritt; also starring Jane Alexander, Chester Morris, Hal Holbrook Beah Richards, and Moses Gunn

Star Wars saga (1977-2019; A New Hope pictured) – multiple directors, as the voice of Darth Vader, also starring Mark Hamill, Harrison Ford, Carrie Fisher, Peter Cushing, Alec Guinness, Billy Dee Williams, Anthony Daniels, David Prowse, Kenny Baker, Peter Mayhew, and Frank Oz

Claudine (1974) – directed by John Berry; also starring Diahann Carroll, Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs, and Tamu Blackwell

Conan the Barbarian (1982) – directed by John Milius; also starring Arnold Schwarzenegger, Sandahl Bergman, Ben Davidson, Cassandra Gaviola, Gerry Lopez, Mako, Valerie Quennessen, William Smith, and Max von Sydow

Coming to America series (1988 and 2021; original pictured) – multiple directors; also starring Eddie Murphy, Arsenio Hall, John Amos, Madge Sinclair, Shari Headley, Jermaine Fowler, Leslie Jones, Tracy Morgan, and KiKi Layne

The Hunt for Red October (1990) – directed by John McTiernan; also starring Sean Connery, Alec Baldwin, Scott Glenn, and Sam Neill

The Sandlot (1993) – directed by David Mickey Evans; also staring Tom Guiry, Mike Vitar, Patrick Renna, Chauncey Leopardi, Marty York, Brandon Adams, Grant Gelt, Shane Obedzinski, Victor DiMattia, Denis Leary, and Karen Allen

The Lion King (1994) – directed by Roger Allers and Rob Minkoff, as the voice of Mufasa; also starring Jonathan Taylor Thomas, Matthew Broderick, Jeremy Irons, Moira Kelly, Niketa Calame, Ernie Sabella, Nathan Lane, and Robert Guillaume, Rowan Atkinson, Whoopi Goldberg, Cheech Marin, Jim Cummings, and Madge Sinclair

Field of Dreams (1989) – directed by Phil Alden Robinson; also starring Kevin Costner, Amy Madigan, Ray Liotta, and Burt Lancaster

#James Earl Jones#Dr. Strangelove#The Great White Hope#Star Wars#A New Hope#Claudine#Conan the Barbarian#Coming to America#The Hunt for Red October#The Sandlot#The Lion King#Field of Dreams#The Empire Strikes Back#Coming 2 America#Return of the Jedi#Darth Vader#Mufasa#Oscars#in memoriam

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

A few of Far Cry 5’s characters’ former names (according to the files)

Did you know that some characters used to have different names? Here’s what I found:

Adelaide Drubman - Penny Johnson (I’m not sure; it’s unclear)

Casey Fixman - Casey Seagal or Casey Storm

Chad Wolanski - Chad Gardetto

Faith Seed - Selena Seed

George Wilson - George Beel

Guy Marvel - Guy Martel (headcanon: it’s still his name but he thought Marvel was a cooler name for a movie director)

Hurk Drubman Senior - Wayne Senior

Joseph Seed - Daniel Seed

Merle Briggs - Merle Clinton

Wilhelmina Mable - Wilhelmina Maybelline

Tammy Barnes - Tammy Palmer (was she supposed to be Eli’s wife? Maybe!)

Tracey Lader - Traci West

Virgil Minkler - Virgil Knutsen

Wendell Redler - Wendell Darrah

Xander Flynn - Bob Johnson (again, like for Adelaide, not sure)

Also, I’ve said this before but Deputy Pratt’s first name is actually Stacy and not Staci. In the files, it’s only not spelled Stacy once, in the end credits... which is also, unfortunately, the only time players had a chance to see it written.

According to the files, Larry Parker’s first name is Laurence, the man we meet near Arcade machines is Morris Aubrey, and the fisherman is Coyote Nelson… but his description in the unreleased in-game encyclopedia also implies he died, so that might be inaccurate.

Below are the names of other Hope County residents (and where they live(d) and/or work(ed)) found in the deleted in-game encyclopedia:

Daniel Holmes — Holmes Residence

Doug and Debbie Hadler — Gardenview Orchards, Ciderworks, and Packing Facility

Rae-Rae Bouthillier — Rae-Rae's Pumpkin Farm

Niesha Howard — Howard Cabin

Emmet Reaves (in the late 1800s) — Copperhead Rail Yard & Prosperity

Will Boyd (from Far Cry: Absolution; his full name is William) — Boyd Residence

Les Doverspike — Doverspike Compound

Mike and Deb Harris — Harris Residence

Wolfgang Dodd — Dodd’s Dumps

Colin Dodd (Nadine Abercrombie’s grandfather) — Dodd Residence

Joe Roberts — Roberts Cabin

Dr. Kim Patterson — Hope County Clinic

Bobby Budell (in 1946) — Flatiron Stockyards

Doug Fillmore — Fillmore Residence

Orville Fall (found gold in 1865) — Catamount Mines

Mike and Chandra Dunagan — Sunrise Farm

The Redler family (Wendell’s) — Red’s Farm Supply

Andrew and Frances Woodson — Woodson Pig Farm

Don Sawyer — Sawyer Residence

Kay Wheeler — Kay-Nine Kennels

Jules Adams (and an unnamed husband) — Adams Ranch

Jerry Miller (and his family) — Miller Residence

Rick Elliot (his full name is Richard according to a message left by Eli) — Elliot Residence

Jay Loresca — Loresca Residence

"Lonely Frank" — Frank’s Cabin

Dicky Dansky — Dansky Cabin

Roy Tanami — Tanami Residence

Mr. Vasquez — Vasquez Residence

Mr. McDevitt — Misty River Gas

Darby McCoy — McCoy Cabin

Dr. Phil Barlow — Barlow Residence

Travis McClean (and his husband Brent) — McClean Residence

Jasmine Chan — Chan Residence

Jerrod Wilson (in the 1800s) — Throne of Mercy Church

Frankie Sinclair — Sinclair Residence

Lydia (in 1912) — Lydia’s Cave

Dwight Feeney (the chemist who worked with Eden’s Gate and dies in the mission “Sins of the Father”) — Feeney Residence

Lorna Rawlings — Lorna’s Truck Stop

Edward O'Hara — O’Hara’s Haunted House

Kanti Jones — Jones Residence

Coyote Nelson — Nelson Residence

Holly Pepper (and her girlfriend Charlie) — Pepper Residence

Nolan Pettis — Nolan’s Fly Shop

Bob and Penny Johnson — Johnson Residence

Melvin Adams Abercrombie — Abercrombie Residence

Steve McCallough — McCallough’s Garage

Dr. Rachel Jessop (who, and I’ll keep saying this every time I can, was never Faith and always another, entirely different person) — Jessop Conservatory

Dwight Seeley — Seeley’s Cabin

#far cry 5#hey I CAN tag everyone this time!#adelaide drubman#casey fixman#chad wolanski#faith seed#rachel jessop#(so not the same rachel)#george wilson#guy marvel#hurk drubman sr#joseph seed#(my headcanon is that daniel is his middle name)#merle briggs#wilhelmina mable#miss mable#tammy barnes#tracey lader#virgil minkler#wendell redler#xander flynn#staci pratt#but actually#stacy pratt#larry parker#far cry absolution#will boyd

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hellhounds on His Trail: E L U C I D's REVELATOR

I speak what I see.

—Saul Williams, “Elohim (1972)” (1998)

I say that one must be a seer, make oneself a seer. The poet makes himself a seer by a long, prodigious, and systematic derangement of all the senses.

—Arthur Rimbaud, “Letters of the Seer” (1871)

Every technological change begins with a spiritual revelation.

—Nathaniel Mackey (2016)

1. LASCIATE OGNI SPERANZA, VOI CH’ENTRATE

The same motherfucker got us living in his hell.

—Chuck D, Public Enemy’s “Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos” (1988)

I must forewarn you even now: what I intend to speak about, and in which I shall get myself entangled for reasons more serious than my incompetence, they are, I believe, without solution or exit. Two years ago, ELUCID promised that I Told Bessie could be significantly darker: “Trust me, it could be way more apocalyptic.” REVELATOR fulfills that promise. I Told Bessie introduced ELUCID as an anti-mystic mystic; on REVELATOR, we find him between the forge and the flame. He speaks from filthy tongue of god and griot, offering a <brand> of spiritual healing in the same <vein> as Dälek’s “Spiritual Healing” [for brand read “fire,” “cauterize,” “marked ownership”; for vein read “cold,” “spike,” “artery”]. At turns, his speech sounds of languages diverse, horrible dialects, accents of anger, words of agony, and voices high and hoarse. On ITB, ELUCID had just arrived in Heaven, trespassed its gates, yet stubbornly refused to sit down, to repose. On REVELATOR, he’s at Hell’s wrought-iron threshold, absolutely ruptured.

ELUCID emerges as a transgressive and dark magus speaking the omniversal language of Sun Ra. The first words spoken on REVELATOR, evidently ad-libbed, recall both Fritz Lang’s expressionistic Tower of Babel and Mister X’s psychitecture: “Metropolis…inverse overlord skyscape…” Another filmic nod would be to PTA’s There Will Be Blood (2017), where the climactic and classical rage of Daniel Plainview is unleashed as he screams: I am the Third Revelation! Plainview is, as his name intimates, an unbeliever, and he masterfully coerces preacher Eli Sunday into stating he’s a false prophet and that God is a superstition.

See, the First Revelation was in the Old Testament (Show me your commaaaandments, as ELUCID drones on “Barbarians”); the Second Revelation was Jesus sermonizing that new shit; why mightn’t it be that the Holy Spirit was preparing another? ELUCID delivers the Third Revelation; he is the Seer, the Revelator—entering through a hatch [re: portal] of Houston horrorcore and disharmonic hard bop. REVELATOR is his unexpurgated rendition of K-Rino’s Stories from the Black Book (1993). The mutant blues of ITB have turned to hypnotik hip-noize—serrated, jaggy, shrapKnel-shattered, caltrop-piercéd. We witness, firsthand, the doom gospel he has previously preached about in practice, in praxis, in the demoniac rhythms and the patterns. Ganksta N-I-P’s “Reporter From Hell” (1993) amalgamated with Rimbaud’s A Season in Hell (1873).

2. NOISOME THE EARTH IS

“Here in this hymn-deaf hell,” Rimbaud reports back, but in ELUCID’s hell all we hear are hymns—shrieks, semiwept, semisung. “A black wail is a killer,” Tracie Morris, Harryette Mullen, Jo Stewart, and Yolanda Wisher write in “4 Telling” (2021), a posse-cut poem. Production of “a satanic symphony,” Rimbaud says. Sounding like EPMD in the pulpit, Rimbaud claims “[t]heology is serious business: hell is absolutely down below.” He describes moonlight when the clock strikes twelve, “the hour when the devil waits at the belfry.” Go get a late pass, in other words, as PE presses on “Countdown to Armageddon” (1988) and ELUCID reiterates on “MBTTS” (2016). “Watch me tear a few terrible leaves from my book of the damned,” Rimbaud writes, appealing to the Devil, “...I will unveil every mystery.”

ELUCID unveils histories of mysteries during his descent. On record, he shares what he sees. He sees Rimbaud in Hell. He sees Kanye and JPEGMafia in hell, Ye with BURZUM in Gothic script emblazoned across his chest. He sees Rubble Kings with SS skulls and sigs sewn onto Flyin’ Cut Sleeves denim. He sees Black Benjie’s assassin in Hell. He sees Richard Hell in hell holding White Noise Supremacists to account for how they treated Ivan Julian (“Mutants can learn to hate each other and have prejudices too,” the latter told Lester Bangs). He says peace to SKECH185 and sees him “playing devil’s advocate with Steve Albini’s Black friend.” Finally, he sees the cerberus in hell—the “monster cruel and uncouth,” according to Dante (c. 1321)—the 3-headed anti-crowd dog. He sees its three gullets, red eyes, and unctuous beard and black and belly large. He sees the wretched reprobates. He sees muzzles filth-begrimed. He sees hellhounds here, there, and everywhere.

3. ROUND US BARK THE MAD AND HUNGRY DOGS

From forth the kennel of thy womb hath crept A hellhound that doth hunt us all to death—

—Shakespeare, Richard III, 4.4.49-50 (c. 1592-1594)

“Hands off,” ELUCID commands on “THE WORLD IS DOG,” the opening salvo on REVELATOR [salvo, a discharge of weaponry; yet also salivate: dog’s drool, secretion, spittle, spit the verse]. “It’s just happening,” he shouts—it’s happening to us; we are subjects of history, its malevolent thrum. “I can feel it ’fore you say it,” and I’ve no reason to doubt him. But allow me to litanize anyway.

In Afro-Dog: Blackness and the Animal Question (2018), Bénédicte Boisseron writes that the dog, the canis familiaris, is “an unwilling participant in the history of social injustice,” a casualty to a depraved Pavlovian conditioning. She cites an “association between canine aggression and black civil disobedience,” reflecting a “prism in which race and dogs insidiously intersect in tales of violence.” She refers to these as cyno-racial (dog-black) representations.

Bloodhounds—aptly-named barking, beastly embodiments of biopower—were “imported from Cuba or Germany” during slavery and “trained to pursue escaping slaves in both the Caribbean and the American South,” Boisseron writes. Dogs were designed to “become ferocious only when in contact with blacks.” The Narrative of James Williams, an American Slave, Who Was for Several Years a Driver on a Cotton Plantation in Alabama (1838) provides insight into this odious operation:

A negro is directed to go into the woods and secure himself upon a tree. When sufficient time has elapsed for doing this, the hound is put upon his track. The blacks are compelled to worry them until they make them their implacable enemies; and it is common to meet with dogs which will take no notice of whites, though entire strangers, but will suffer no blacks.

The Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, an American Slave, Written by Himself (1849), meanwhile, offers a suspenseful, first-person account:

We had been wandering about through the cane brakes, bushes, and briers, for several days, when we heard the yelping of blood hounds, a great way off, but they seemed to come nearer and nearer to us. We thought after awhile that they must be on our track; we listened attentively at the approach. We knew it was no use for us to undertake to escape from them, and as they drew nigh, we heard the voice of a man hissing on the dogs.… The shrill yelling of the savage blood hounds as they drew nigh made the woods echo.

The training, of course, isn’t only about ghoulish intimidation; the hunt would often climax with violence. “When the slave runs away,” Boisseron explains, “the master needs to symbolically reassert his domination through a ritualized act of flesh cutting.” [FANG BITE!] Frederick Douglass spoke of such savagery: “Sometimes in hunting negroes…the slaves are torn to pieces.” Mutilation of runaway slaves, Boisseron claims, enacted “a rhetoric of edibility.” Derrida called it carno-phallogocentrism, linking the slavehunter’s virility and carnivorism, savoring “deeper shades of carnage,” as ELUCID says on “ZIGZAGZIG.” It has never relented. In the wake of Michael Brown’s murder in 2014, the DOJ issued a report that detailed “puncture wounds” left in children by the Ferguson K-9 unit. The victims of these “bite incident[s]” were always Black.

ELUCID also speaks of how victims “force-feed a war machine” on “ZIGZAGZIG”—regions and relics swallowed whole, irrevocably. In their plateau “Becoming-Intense, Becoming-Animal, Becoming-Imperceptible…” (1980), Deleuze and Guattari write: “You become animal only molecularly. You do not become a barking molar dog, but by barking, if it is done with enough feeling, with enough necessity and composition, you emit a molecular dog.” Somewhere on a desolate Yonkers street corner, DMX sleeps with a pack of strays, lying in wait.

4.

Police forces…have used dogs to break up rioting mobs…. The dogs’ snapping teeth, swift movements and indifference to the crowds’ menacing threats have made mob control a routine procedure for the forces which have the dogs.

—“A Progress Report of the Assembly Interim Committee on Governmental Efficiency and Economy on Using Dogs in Police Work, California” (1960)

If a dog is biting a black man, the black man should kill the dog, whether the dog is a police dog or a hound dog or any kind of dog… [T]hat black man should kill that dog or any two-legged dog who sicks the dog on him.

—Malcolm X (1963)

In a contemptible case of cultural exchange, two German shepherds trained by a Nazi stormtrooper were used by police in Jackson, Mississippi to attack crowds in support of the Tougaloo Nine—Black students attempting to access books from a whites-only public library. That was in 1961. [TRUST NONE!] Two years later, Bull Connor utilized dogs to disperse protestors in Birmingham, notoriously documented by Charles Moore and Bill Hudson. Hudson’s photograph of fifteen-year-old Walter Gadsden in the mongrel maw of law enforcement fills textbook pages to this day, while Moore’s photo would be aestheticized and reproduced in Andy Warhol’s Race Riots series in 1964. “Police dogs is one of the accepted practices in police riot work,” a swinish Alabama sheriff said in ’63. Not much has changed. When people demonstrated outside the White House gates after the death of George Floyd, an orange fascist—who ELUCID begrudgingly won two long-standing bets on—threatened them with “vicious dogs.”

“Dogs were once perceived as dangerous due to rabies,” Boisseron writes, “but today the black man is the one responsible for making the big dog look ‘un-kind.’” A.G. rapped about the dogs with the rabies on 1992’s “Runaway Slave,” looking backward to understand his present, but by the ’90s, the ever-evil LAPD was calling Black people “dog biscuits.” An officer in a St. Louis suburb faced suspension after posting to Facebook that Ferguson protestors “should have been put down like a rabid dog the first night.” The aggression of the dogs, Boisseron points out, has “metonymically shifted from zoonotic to a racial context.” In essence, society shouldn’t fear the dogs—society should fear a Black planet populated by Black men. [FEAR ALL!]

The messaging has frequently been mixed—deliberately muddied (mutted, we might say) to defy understanding—racism skewing absurdist. In “A Dark Brown Dog” (1901), Stephen Crane used a “little dark-brown dog…an unimportant dog, with no value” with a “short rope…dragging from his neck” for allegorical purposes. [SHORT LEASH!] A child drags the dog “toward a grim unknown,” the child’s intolerant family. The dog is by its very nature powerless, “too much of a dog to try to look to be a martyr or to plot revenge.” Eventually, the drunk father beats the dog with a coffee pot and tosses him out of a fifth-floor window, falling dead in the alley below. Crane’s well-meaning story speaks to mystery writer Stanley Ellin’s comparison of the “solicitous white intellectual” and the “arrant racist,” the former of which “sentimentalized Black lives” and “patted them on the head as one would a pet spaniel.” To retreat to such romanticizing, Ellin says, fulfills the “function of the stereotype, and it matters very little whether the stereotype is that of vicious hound or pet poodle.”

As a child of the ’80s, ELUCID was exposed to the same surfeit of televised copaganda as the rest of us. McGruff the Crime Dog colonized our commercial breaks, asking us to join the feeding frenzy against drug dealers and burglars (Take a bite out of crime!). Meanwhile, Harlem World’s Herb McGruff provided counterprogramming and warned us of the real “Dangerzone.” “The idea of dogs attacking black people has become a haunting and unresolved image in the collective memory,” Boisseron writes, or, in ELUCID’s words: Eating everyone eventually. THE WORLD IS DOG!

5.

On SEERSHIP! (2020), a project ELUCID labeled a “work of spirit”—a work of glitch-hop and runt pulses and ill-bent illbient—we hear a blare of noise at roughly the one-minute mark. That calamitous blare is sublimated into the soundfury that sets off “THE WORLD IS DOG.” ELUCID’s bogeyman-down production, in collaboration with Jon Nellen’s urgent drumming and Luke Stewart’s grave-groove bass theories, provide for the sonics of a slave escape, equal parts panic and empowerment. “The dissonance is real,” ELUCID raps on “VOICE 2 SKULL,” “—I be feeling woozy,” and that’s the vibration here. In Dred: A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp (1865), Harriet Beecher Stowe describes how the vengeful and unforgiving escaped slave Dred defends a runaway from a hellhound:

…a party of negro-hunters, with dogs and guns, had chased this man, who, on this day, had unfortunately ventured out of his concealment. He succeeded in outrunning all but one dog, which sprang up, and, fastening his fangs in his throat, laid him prostrate within a few paces of his retreat. Dred came up in time to kill the dog…

“THE WORLD IS DOG” is pulsing and gnashing, a sequence of switchbacks and untoggled kill switches, a hyper-aural freak-out, to borrow some phrases from ELUCID’s New York Times blurb for Ornette Coleman’s “Science Fiction.” We should’ve anticipated the arrival of “THE WORLD IS DOG,” should’ve been listening to the panting precursor curses. Be it the gold chain punk asphyxiation of Soul Glo opening for ELUCID at the ITB release show at Mercury Lounge in 2022; the absurd matter we heard from his Shapednoise feature in 2023, wherein he “backhoed the graves”; or his appearance on Kofi Flexxx’s “Show Me” a few months later (I show you what it look like…)—the signs were all there. When word got out that ELUCID was spinning Miles Davis’s “Rated X” (1974), we should’ve known it was over, cataclysmically.

If “Rated X” is the model, then ELUCID has set out to attain “music’s most elusive grail,” as Gary Giddins calls it in Visions of Jazz (1998): “the promise…of an open-ended form that defies harmonic conventions and regulation eight- and twelve-bar phrases in favor of a flexible but contained form.” An anonymous internet blogger called “Rated X” a “demented church service where the organist has become possessed by an evil spirit and worshippers have fallen into a trance.” ELUCID puts the incendiary fuse in fusion—dark energy acceleration | emergent fervor, fire & brimstone | Tony Williams Lifetime-type EMERGENCIES [ecphoneme—bang—ecphoneme—bang…]. This is rap-fusion—uncontrived, channel alive.

6.

“Fire for fire, wade in the water,” ELUCID raps on “YOTTABYTE,” singing the same sorrow song of a century-plus before. “Wade in the Water” (Roud 5439) was a spiritual that reminded the runaway slaves to use streams and rivers to throw the hellhounds off the scent. “If you hear the dogs,” Harriet Tubman said, “keep going.” If “THE WORLD IS DOG” begins in a dreaded delirium, it ends [DEVOLVE!] in radical resistance.

The faded amateur photograph that graces the cover of I Told Bessie shows a man fending off a German shepherd; or, feasibly, the man is elevating the dog—healing it, calming it, exorcizing its engrained demons. Admittedly, it’s a crazy mixed-up world, a doggy dogg [dog-eat-dog] world, and the dog can occupy valences of both killer and companion. Everyone is dehumanized in the slave hunt, in the crowd dispersal. The hunters and the cops are the actual beasts (“That’s the sound of da beast,” KRS howls; “the murderous, cowardly pack,” Claude McKay snaps); the hunted resort to instinct, fearing for their lives, amygdala swelling with signals.

In Martin Delaney’s serialized novel Blake; or, the Huts of America (1859-1862), protagonist Henry Holland, a.k.a. Blacus, a.k.a. Blake, wields a “well-aimed weapon” and “slew each ferocious beast as it approached him, leaving them weltering in their own blood instead of feasting on his.” Delaney doesn’t only draw scenes of retributive slaughter; his characters also speak of how “da black folks charm de dogs.” Threats neutralized. Power harnessed. The Yorkshire Terrier on the cover of Swans’ The Seer (2012) bares Michael Gira’s chompers—he’s merged with the pup. Hip-hop auto-interpellated dog into dawg (s/o to Althusser).

7.

As we learn from “Amager,” ØKSE’s song featuring billy woods, dogs only violate at the behest of men. woods relates a narrative of detainment at Trondheim Airport. The purportedly “colorblind drug dog” exudes innocence (“flopped on the floor, head on his paws”), though its mere presence smacks of discipline and punishment. As the Norwegian customs agent “palm[s] [woods’] clean drawers,” woods sardonically reflects, “I been a nigga too long.” He “know[s] the dance” and “know[s] the damn song,” resentful of this choreography of incurable racism that has been all too common and recurring throughout his life. He understands what’s happening epistemologically (“I know they hoping… I know I’m clean…”), but he also knows “those clammy hands going from the crack of [his] ass to the weight of [his] balls” are suggestive of castration, and when you’re crossing borders, what, what, say what, say what, anything can happen. As they go through the rigamarole of “mak[ing] calls, x-ray[ing] the empty suitcase, / [And] going back through [his] pockets,” woods stews with “impotent rage,” the aforementioned emasculation working its spell. He doesn’t begrudge the animal laboring under the aegis of the Tolletaten, though: I pet the dog as I leave. Scathed but saved. He charmed de dog.

8.

After dealing with so many strays I had learned one thing: be patient.

—E.A.R.L.: The Autobiography of DMX (2003)

Perhaps no figure better illustrates the subjugation and subversion of the hellhound than DMX. In the lead up to the millennium, Dark Man X embodied the dog of vengeance; he exemplified the undoing of the dog’s quasi-innate hatred of Blackness. In ELUCID’s words, he emerged as a “whole new nigga” with “skin [untorn], eyes [ungouged], hair [unshorn].” DMX’s arrival in 1998 felt like centuries in the making. He waged a vendetta in the name of every runaway slave and Civil Rights demonstrator. He’d slept on the streets and shared the concrete with his dogs, strays like himself:

Stray dogs are normally scared of people; they’re scarred by whatever neglect or abuse put them out on the street. Or if they’re lost, they’re depressed because they can’t find their way home. But that morning I decided that no matter how long it took, I was going to get that dog to come over to me. I was going to convince him to trust me and make him mine…. I started looking all over for strays that I could catch and train for myself…

DMX charmed de dogs and the rest of us in the process. He stayed shitty, cruddy, trading the cartoonish bow-wows we’d become accustomed to (via Snoop) for fierce grrrs and arfs, elevating rap’s onomatopoeics. With “Get At Me Dog,” he turned a familiar B.T. Express funk sample feral. In the video, the most achromatic Hype Williams ever managed, X holds possession of the Tunnel crowd, on a stage but of the people. His only bling: a stainless steel choke chain that collars his neck. The black-and-white video disorients with strobe effect and negative exposure—pitch blacks suddenly transform into flashing whites. Russell Simmons and Lyor Cohen look on from the periphery of the crowd like, well, out-of-place bitches. The video captures the raw power of DMX, his stygian intensity, reminiscent of Tadayuki Naitoh’s 1971 photograph of Miles Davis. Like X, Davis harnesses his rancor and exhibits his self-possession.

The success of DMX’s subversion of the dog trope likely apexed with his Woodstock ’99 performance. Before a majority white crowd of hyperthermic slavehunter descendants, DMX rocked what Thomas Hobbs calls “blood-red dungarees.” X “growls viscerally” and “convulses” across the stage in a manner “akin to a Bad Brains gig in a sweaty punk basement.” DMX—like Dred and Blacus before him, like ELUCID to come—subdues the monstrous, cowardly pack, and has them eating Milkbones out of his hand by the end of the 45-minute set.

9.

The first thing we feel on REVELATOR is a snarling, ravenous “fang bite” and the exhale of “dog breath.” We search for alternatives: the RZArector’s fangs on 6 Feet Deep (1994) maybe, a presence that Kodwo Eshun argues is akin to a head “filled with revelations that impeach the daylight.” We might think of the parallel universe of “The Big Rock Candy Mountains” (1928) where “dogs all have rubber teeth,” but REVELATOR doesn’t offer up that heavenscape—only a hellscape where teeth tear rabidly, rapidly. The “dog fangs [which dig] into black flesh,” Boisseron writes, are “deeply ingrained in popular culture.” We’d prefer the hip-hop context for “biting,” like when Rakim invokes “biting and borrowing” on “Follow the Leader,” where “brothers tried and others died to get the formula.” We’re on a “short leash” here, but Chuck D speaks of how he “cut the leash” on “Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos” and how prison bars “got [him] thinking like an animal,” and so I think we should act accordingly, tactfully, and lick our wounds.

ELUCID strafes us with 2-syllable units, iambs or IEDs, right from the start:

Fang bite Dog breath Short leash Pit fight

We’ve not felt shelling like this since the opening words of DMX’s It’s Dark and Hell Is Hot (1998):

One-two One-two Come through Run through Gun who? Oh, you don’t know what the gun do?

We’re propelled and pummeled by a Dark Enlightenment acceleration; unquestionably, we’re on our heels. ELUCID activates a sequence of 3-syllable units—anapests—as we descend into Hell:

From this height At this speed Downhill Careening

Later, the 2- and 3-syllable units alternate: “Shit that binds, / Spit out, / Ribs came spared.” Such blunt syllabics occur elsewhere on the album as well. “YOTTABYTE,” for instance, introduces a more dactylic, grounded pattern: “Hard science, / Scum gutter.” These are billboard throw-ups in Mister X’s Radiant City. They’re terse skull snaps like when Michael Gira sings, “Space cunt, / Brainwash” on “The Apostate.”

“I’m not psychic, but I’m reading,” ELUCID clamor-raps. The rapper has repeatedly denied the spiritual and supernatural in favor of tangible work, learning, reading. He much rather attend a demo or browse a bookstore than show his face at a séance or a church service. “The more I thought, the less I prayed,” he raps on “BAD POLLEN.” In this regard, he’s a dialectical materialist, much to the dismay of so many nimrod New Age seekers. ELUCID is not your self-help savior. Appropriating occult symbology in song is not inscribing sigils on the navel of a newborn. More likely he’s standing in solidarity with the child laborers pulling opal from the ochre mines of Madagascar. “Black Jesus hated bill collectors—I do the same,” he raps on “IN THE SHADOW OF IF.”

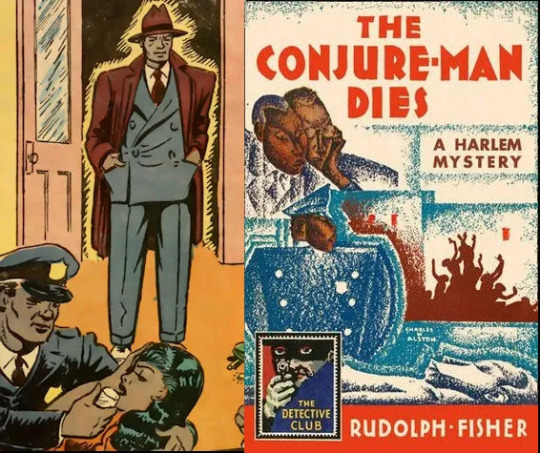

In The Conjure-Man Dies (1932), Rudolph Fisher’s Harlem murder mystery, the titular conjure-man, one N’Gana Frimbo, is the closest forebear to ELUCID, a practitioner of the aesthetics of alchemy but one who knifes through the nonsense:

There are those that claim the power to read men’s lives in crystal spheres. That is utter nonsense. I claim the power to read men’s lives in their faces…. Every experience, every thought, leaves its mark. Past and present are written there clearly…. My crystal sphere, therefore, is your face.

“I receive it, then I weigh it,” ELUCID explains. He’s no Knownot but he also knows that he knows nothing, in a Socratic sense (one day it’ll all make sense, trust me [TRUST NONE, FEAR ALL]). He’s a member of a tribe on a quest, receptive of vibes and stuff, asking questions like: What? Can I kick it? Does it live or die? Who gon’ tell me why? Who goes there? Who dare disturb the hive? He remains unflappable, constant, “still inside,” channeling his “honey child” while killa bees are on the swarm angling for the fatal sting.

Our “small world” is razed; it “devolve[s]” as hell is raised—it’s not that tricky. The dog’s got “jaws that grind” and “teeth that tear”; Dante tells us Cerberus “displayed his tusks” and “rends the spirits, flays, and quarters” his enemies. “Where’s a pit, there’s a plague,” ELUCID says, demonstrating syntactically that life is parallelism to Hell but we must maintain. Boisseron discusses the “hysteria around pit bulls” rooted in an “overblown fear of rabies,” and we watched a “plague” of reckless media representation caricature Michael Vick as the very animals he electrocuted. “Pit bulls have been historically used in America as a weapon of stigmatization against blacks,” Boisseron explains, and so every Black man takes up residence in the Bad Newz Kennel when the public deems it convenient, whether they would ever dare to hold the jumper cables or not. If the stigma doesn’t catch up to you, the sickness will. ELUCID’s “pit” evokes morgue trucks reversing up to the trenches in the potter’s field. Careful where you step, or else risk experiencing “a quick trip to glory if you slip.” Pitfalls on every corner, beneath the buildings of every block. Like DMX said on “Get At Me Dog,” If you don’t know by now, then you slippin’.

“Be not afraid,” ELUCID advises, bending Biblical. It is I. It is I. It is I. If we can keep up, he’ll usher us out of the ravaged world. If not, “don’t know, don’t care—get out my way!” ELUCID’s “in the garden,” his own private Gethsemane, agonizing and “pouring for everyone whole came before [him]” and didn’t survive the onslaught. He pours out a little liquor, and like Pac who had his “back against the brick wall, trapped in a circle, / Boxing with them suckers till [his] knuckles turn[ed] purple,” ELUCID is intoxicated by his own dogged determination. Pac was simply rewriting McKay, who likewise found himself “pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!” Glorious as it sounds, ELUCID’s exhausted—as we all are—by song’s end: voided. All he can put together are fragmented, clipped, incomplete idiomatic and figurative expressions: “razor walking”; “bridge to nowhere fast.” Still, he bites back. Like DMX, he’s “eating everyone eventually,” indiscriminately, re-establishing the order of “the world [that] is dog.” He, too, is dog. Sic ’em, and get sick wid’ it.

10. TEKNOHELL

Today the plagues of Revelation are…the disastrous results of…the irrational use of technology.

—Pablo Richard, Apocalypse: A People’s Commentary on The Book of Revelation (1995)

“Police dogs were often framed as technology,” writes Tyler Wall, a scholar of racialized state violence. He cites a Baltimore K-9 officer who claimed “[t]he dog is the most potent, versatile weapon ever invented…. You can’t shoot around corners, but dogs can go anywhere you direct them—like guided missiles.” These comments anticipated the NYPD’s rollout of actual automated, data-gathering robot dogs, of course. But “CCTV” and “YOTTABYTE” escort us into an arena of Ballardian extreme metaphors and emergent technologies—a teknohell—where “Spot bots” prowl every city block.

“CCTV,” co-produced by ELUCID and August Fanon, screeches like a dial-up modem gone diabolical—a discordant din of panic chords. They’ve programmed drum patterns around the sound of the CCTV shorting out—the dread comes in sine waves: megahertz hurts | multiplexing and motion-detecting | low-frame rate. The cameras are everywhere we look, but ELUCID splits the veil and the surveillance. The mandala is a panopticon, a C-band satellite dish for bodies to rot upon. Impaled by feedhorns. Parabolically resting in peace. In “a moment of clarity,” ELUCID fucks the noise and begs, “Don’t be mad at me.” I ain’t mad at cha. Who could begrudge the corner boy who cracks the lens of a varifocal security camera with a rock in the courtyard of the low-rises (they call it “the Pit” on The Wire)?

The ill communications that ELUCID was channeling on Armand Hammer’s We Buy Diabetic Test Strips continue to nauseate him. A year prior to that release, ELUCID told Gary Suarez that he was working to “dismantle what isn’t serving and then download and update with what does now.” For the man who “feel[s] a way about proving [his] identity to robots,” he can also acknowledge damage has already been done, which is evident in his diction. On SEERSHIP!, he despaired: “Every device I own knows my latitude.” On “NY Blanks,” he warned: “computers are listening.” In Jacques Derrida’s “Of an Apocalyptic Tone Recently Adopted in Philosophy” (1983), he describes a Tetsuo-like man/machine [MAchiNe] who loses clarity between the sender and the receiver of electronic messaging:

And there is no certainty that man is the exchange [le central] of these telephone lines or the terminal of this endless computer. No longer is one very sure who loans his voice and his tone to the other in the Apocalypse; no longer is one very sure who addresses what to whom. But by a catastrophic overturning here more necessary than ever, one can just as well think this: as soon as one no longer knows who speaks or who writes, the text becomes apocalyptic.

In this sense, REVELATOR is, at turns, an apocalyptic text. Much of ELUCID’s work has been. The cover of SEERSHIP! features a P1 phosphor font choice, as if it’s destined for a monochrome monitor. One might come to believe ELUCID writes in matrices of terminal green.

11.

In Fisher’s The Conjure-Man Dies, N’Gana Frimbo is questioned by Dr. Archer:

“You actually are something of a seer, aren’t you?” “Not at all…. I filled in the gaps, that is all. I have done more with less. It is my livelihood.” “But—how? The accuracy of detail—”

“Even if it were as curious as you suggest, it should occasion no great wonder. It would be a simple matter of transforming energy, nothing more. So-called mental telepathy, even, is no mystery, so considered. Surely the human organism cannot create anything more than itself; but it has created the radio-broadcasting set and receiving set. Must there not be within the organism, then, some counterpart of these? I assure you, doctor, that this complex mechanism which we call the living body contains its broadcasting set and its receiving set, and signals sent out in the form of invisible, inaudible, radiant energy may be picked up and converted into sight and sound by a human receiving set properly tuned in.”

ELUCID showcases his broadcasting set and his receiving set, but his carries the outlaw spirit of an illegal cable box or the pirate radio signal from the short-lived Dread Broadcasting Corporation out of West London in the 1980s. ELUCID as DJ Lepke in limbo.

12.

The title “VOICE 2 SKULL” evokes a note to self, a Nextel push-to-talk, or a voice-to-text: ELUCID as fully automated, as a cybernetic MC. But the human essence—the flesh, blood, and bone—is still there: “I get up before everyone and lose my mind first— / For even just an hour, I work in sound and feeling—sometimes fury, / Asking the whys and hows when lies turn to vows.” That is, he grinds; his work ethic, the grating of gears. He starts his day, travels where he will, but always “free roaming” and “pinging stupid” as a “transcontinental satellite receiver freaking forth.” On “XOLO,” as tek, he “reach[es] inside—only to [his] elbow, / [And] pull[s] it back out like [he] was rewound.” Like a VHS tape, or Betamax. Functioning as some new plastic idea. We’re all wired and wasting away with “mirror[s] in pockets” as we busy ourselves “looking hard in the camera.” Not squinting to make sense, merely modeling a manufactured exterior.

13.

Digital overlords don’t need free promo…

—ELUCID, ØKSE’s “Skopje”

The teknohell is ever-present on REVELATOR—you can’t escape its server rack bracket clutches. “Defrag the files,” ELUCID raps on “BAD POLLEN,” attempting to counter what Nathaniel Mackey calls a technology of decay. RFIDs, modems, CCTVs, pagers—all this tech isn’t anachronistic; it’s timeless—e-waste salvaged or scavenged—but ELUCID evolves, keeps it moving [...like a moving target], even if that means “bloody fingers on the keypad,” which we heard of on Valley of Grace. His own magnetic fields fuck up electronics; he lives in the “chaos hour shadow play” mentioned on “THE WORLD IS DOG.” “The situation’s unreal,” as Chuck D says on “Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos.” “There are no hard distinctions between what is real and what is unreal,” Harold Pinter responds. Ultimately, ELUCID is “wholly unimpressed by your social media metrics,” at least according to “MBTTS.” He offers up “brick and mortar rhyme for distorted time” and “offline [is where] [his] core thrives.” He knows what’s what: these gadgets and gizmos are “soon to be rendered useless: and then what?,” as he inquired on Small Bills’ “Even Without You.” Merchandise is Brand New Second Hand as you sit in an ergonomic swivel chair before Roots Manuva’s radiation-emitting dusty microwave. ELUCID searches for a truth beyond the motherboard.

14.

I tell you this in truth; this is not only the end of this here but also and first of that there…the end of history…the death of God, the end of religions…the end of the subject, the end of man, the end of the West…the end of the end, the end of ends, that the end has always already begun, that we must still distinguish between closure and end…. it is also the end of metalanguage on the subject of eschatological language…

—Derrida

…so let me shut the fuck up.

—Editor’s note [me]

Tell me a lie, tell me a truth becomes ELUCID’s Max Headroom mantra for “CCTV,” minus the sputtering, the glitching. We like to think that the “truth [will] find you where you at—it’s fine, it’s fair,” he raps on “RFID,” but, more often than not, revealing the truth requires trying. Your responsibility, Toni Cade Bambara insists, is to “try to tell the truth,” and “[t]hat ain’t easy.” It’s tough to summon the strength when we “have rarely been encouraged and equipped to appreciate the fact that the truth works.” The machinery of lies and disinformation come fine-tuned with a gleaming chrome finish. As for truth, we’re numb to its virtue; neutered by negative thoughts and clouded past experiences. But if we can pursue truth, prove it, and impress it upon our enemies, according to Bambara, “it releases the Spirit.”

The “cattle prod [will] shock you back some reality,” ELUCID raps. But truth can seem a hackneyed notion in the wrong hands. In Baldwin’s “Going to Meet the Man” (1965), Jesse, an abusive cop who takes sadistic pleasure in cattle prodding Civil Rights protestors, is charged with bringing the singing of jailed demonstrators to an end. He targets the “ringleader” of the group: “I put the prod to him and he jerked some more and he kind of screamed—but he didn’t have much voice left.” The protestor refuses to call for the others to stop singing, either out of defiance or debilitation from the beating he’s suffered, so Jesse’s frustration grows: “...the prod hit his testicles, but the scream did not come, only a kind of rattle and a moan.” Revisionist history can’t absolve the truth of that barbarity.

In one final [ex]plosive shout before “CCTV” transitions, ELUCID says, “Steal me your blues.” A call for reappropriation of what has already been plundered on a mass scale. The blues are never blameless. ELUCID collects blues and deranges ’em—traditional | twelve-bar | crowbarred | prison blues—deep cobalt with sapphiric crazing. REVELATOR most obviously invokes Blind Willie Johnson’s version of “John the Revelator” (1930), what with his scum gutter growl of Who’s that writin’? Jeff Place called Johnson a “guitar evangelist,” a man who was blinded by lye in his eyes at seven [the means of his marring and age should not go unnoticed], a reenactment, perhaps, of John the Revelator’s being dunked into the boiling oil cauldron—not nearly the “musky oils” ELUCID spoke of on “Obama Incense.” The teknohell is home to a Victor Talking Machine, no doubt, and the 78 RPM shellac record of Robert Johnson’s “Hellhound on My Trail” (1937) spins centripetal. RJ’s bottleneck slide screams phoenix as he sings, I got to keep movin’. For protection from the dogs—zig, zag, zig.

August Fanon and ELUCID sacrifice the frenetic for a straightforward refrain to conclude “CCTV,” something to mesmerize with layered vocals, subliminal messages not so sub- that they’re unmanageable. Take freedom: ELUCID wants you to hear the message, the charge. “All power to oppressed people” isn’t just a slogan for him; for others, as we know, it undeniably is. He asks for a “red light on the virtue signal for the come-latelys”; or, as PremRock says on ShrapKnel’s “Human Form”: “Closeted moderates post black squares then act scared of actual progress.” On “NY Blanks,” ELUCID “refuse[d] to kneel and pray for hashtag another slain name, / On the dashcam frame of sight.” Technology pervades every moment of life and language—from sonogram to dashcam and the SMS notifications of each and all else in-between.

15.

Child Actor’s production on “YOTTABYTE” traps us inside the machine with hex bolts knocked loose and rattling around. Again, technology works its way into everything. “Stints and priors, / Sweat labor, / August sun,” ELUCID raps, seemingly on a chain gang—the teknohell is a maximum security prison: biometrics | video analytics | signal-jamming | duress alarms. Data storage facilities bursting at the seams.

“Terabyte, gigabyte, niggas bite,” ELUCID spit on “Bitter Cassava,” adding with a whiff of cybersexuality, “I heard ass taste better in the summertime.” Do androids dream of having a romp with the provocatively named Deckard? Do Nexus-6 replicants have rape fantasies? “Came out the pussy and wrote a classic,” ELUCID says on “YOTTABYTE,” and I’m left wondering what Jodorowsky’s love machine from Holy Mountain (1973) might have to do with this. Cold and sterile tech-infused corporeality | conjugal visits with slinky cyborgs | proto-pornbots.

“SKP” presents as more sound poem than song—its patterns erratic, and therefore erotic—unpredictable with vocals pitched down and up arbitrarily. Andrew Broder provides a mellowed pulse backdrop, tunneling toward something visceral, and not the gear boxes and springs, the sensors and metal tubes, that make up a robot’s innards. ELUCID has previously proclaimed he was “a dyke in a past life,” a Sister Outsider standing alongside Audre Lorde: “Images of women flaming like torches adorn and define the borders of my journey, stand like dykes between me and the chaos.” “SKP”—Some Kind of Power—draws inspiration from Lorde’s “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power” (1984), which reframes eroticism, removes it from the teknohell.

I know you know the codes, ELUCID says. His lover has the key—they each possess a copy. And the key is crucial, at the crux of the relation; listen to what woods says on “INSTANT TRANSFER”: “It’s all skeleton keys on the keyring I keep, / Keys I never seen before for places I never even been, / Luxury cars—I key ’em and go to sleep.” Keys, keys, keys, as Angela Carter writes in “The Bloody Chamber” (1979)—to china cabinets and safes and every other secret place. The narrator’s husband, though, forbids his young wife from using one key in particular. Not the key to his heart, as she presumes (“skeleton key to ya heart,” ELUCID echoes on “CCTV”), but “the key to [his] enfer.” He teases and tantalizes her and throws all the keys into her lap as “the cold metal chill[s] [her] thighs through [her] thin muslin frock.” Something’s not quite right; “we was down singing off-key: how?” ELUCID says on “XOLO.” The key might crack the code | stroking and fondling | heavy petting | as artificial intelligence records the taps and timbre of your keystrokes, stealing sensitive passwords—a sensate focus therapy for anonymous internet users. Probably best to keep the key under the mat.

“The erotic is a considered source of power and information within our lives,” Lorde writes. ELUCID answers: “Knowing is enough—deepest core informing all.” The erotic, Lorde notes, “offers a well of replenishing and provocative force to the woman who does not fear its revelation.” “From here forth,” ELUCID says, “you spit, you scream, you burn my tongue too raw—be soft.” Erotic, Lorde explains, is from the Greek eros, “born of Chaos, and personifying power and harmony.” Harm may precede harmony; pain prior to reaching “beyond the posture and the program.”

“Call me out my name,” ELUCID commands, “I’ll be the one you cum for.” Even if he brushes against the sophomoric at times (“Baby, please pop that pussy for breakfast” would be one such example from the archives), ELUCID’s sex raps swerve sophisticated. Lorde says the erotic is often “confused with its opposite, the pornographic,” which would demonstrate sensation without feeling. When ELUCID says “call me out my name” to his lover, he’s exploring “how acutely and fully [they] can feel in the doing.” Lorde explains, “[A]s we begin to recognize our deepest feelings, we begin to give up…being satisfied with suffering and self-negation…with the numbness.”

The technological bent to “SKP” climaxes with connectivity (¿Tu Tienes WiFi?)—a mutual dependance—“power which comes from sharing deeply any pursuit with another person.” In 2020, ELUCID told Tim Fish about how a trip to South Africa inspired Valley of Grace (2017): “...my wife was there, she was still my girlfriend then, and she was working at a law center, working towards protecting sex workers…. So being there, she’s at work for at least 8 hours a day, and I’m in the flat just hanging out….” At the end of “SKP,” ELUCID declares “in a union made now, tomorrow anything…,” and we feel the phantom phrase “…is possible” in the absence that follows.

“There are many kinds of power,” Audre Lorde tells us, “used and unused, acknowledged or otherwise.” 2Pac, for instance, never achieved ELUCID’s level of erotic power in song. On “How Do U Want It?” (1996), Pac was forward with his proposal, seeking consent (“Tell me is it cool to fuck? / Did you think I come to talk? / Am I fool or what?”), but copped to his preference for pornographic perversions, the “positions on the floor” he invokes: “Ironic, ’cause I’m somewhat psychotic.” Lick before you bite, ELUCID raps on “BAD POLLEN,” his own nod to the erotic/psychotic dichotomy. But it’s more tempered than Pac’s imprudence. He seems to taunt Pac’s shortcomings on “YOTTABYTE”:

Wiggle with the lights on, Ripple off thrust, Ooh, it’s just us, Yes, I need it how I want it, Feel like Southern California with my belly full…

Not to say ELUCID’s erotic power is purely PG-13; it’s not. On “BAD POLLEN,” he “wake[s] up and thrust[s] inside [his] missus, / Two fistfuls of hair, [his] face buried.” Flashes of a possessive desire, an “I Wanna Be Your Dog” energy: So messed up—I want you here…in my room…I want you here. But even when ELUCID goes raunchy, it’s organic matter, raw materials—mud and bone and verdant muck—not nuts and bolts and a nexus of cables. His trysts always involve talking out the mud, crashing through the walls…, scorch, [and] stimuli response.

16.

I might work with the wires wet if we talking ’bout power…

—“INSTANT TRANSFER”

With SKECH185’s analog(ue) tape dispenser on loan (also note the Basinskian “disintegration tapes” mentioned on “IKEBANA”), ELUCID patches and splices the first bars of “INSTANT TRANSFER” in a terse trimeter:

Five side, keep the tape warm, Wrapped rays weighing way more, Racks raid how we wage war, Slack walk to a main course.

The alliterative and consonantal groupings (“wrapped rays”; “racks raid”; “weighing way”; “we wage war”; “slack walk”; “keep the tape”) and slant rhymes present an inconsistency that models a human touch—the warmth of the analog tape undermining digital media and the instantaneous [gratification and otherwise] operations of an ATM withdrawal, just as we see the plastic bank card repeatedly guided into the multi-function maw by a human hand in the “INSTANT TRANSFER” video.

Nostalgia is no retreat from the teknohell. Even on a memory song like “HUSHPUPPIES,” the hum of Integrated Tech Solutions interferes when ELUCID recalls the “static sizzle with the grease in stereo”—frying fish and the kitchen TV set in concert with one another. “HUSHPUPPIES” feels like a loose adaptation of Henry Thomas’s “Fishing Blues” (1928), a fond recollection of fish as sustenance. Both ELUCID and Thomas begin with an urgency; Thomas “went up on the hill about twelve o’clock,” and ELUCID speaks in a tongue-twisted, nursery rhyme: “Must find fried fish—it’s Friday.”

REVELATOR has us fearing for the worst: fish fried in sulfuric waters, gilled vertebrates pulled from the River Styx—but it’s not that. “HUSHPUPPIES” feels down-home, a brief view of before, of Bessie-time, of salve and saviors and stove-top safe haven. “Put on your skillet,” Henry Thomas sings, “Mama gonna cook ’em with the shortenin’ bread.” “HUSHPUPPIES” works as a child-vision folk song, much like the “choking on a church mint” episode of “Guy R. Brewer.” ELUCID is an artist composing twenty-first century folk ditties, intent on inclusion in the Roud Index. I’m wary of the “sugar water, lemon sugar, water lemon” lyric sequence, though—the words transmit, mutate, like a gain-of-function in the kitchen sink. I feel he’s trapped speaking with “the language of the on-again/off-again future, and it is digital,” as Laurie Anderson once said.

17. PEOPLE TEND TO THINK THAT A PAGER’S FOUL

In 1991, Q-Tip asked us if we knew the importance of a skypager. The responsibility fell to Phife Dawg to explain it in full:

The “S” in skypage really stands for sex, ………………………………………………….. At times I miss the pager so you don’t get vex, Having bad days like a voodoo hex, Conceptually, a pager is so complex that I be standing on the verge, ready to flex.

ELUCID portals us to that very ’90s dimension to pick up on Phife’s “-ex” rhyme scheme.

Skypage text, alphanumeric, Blind days—rain taste metallic, Dark roads lined with tall pine, Fire tongue in the annex.

Where Phife’s explication was elementary with its backronyming and monosyllabic rhymes, its simile and succinct storytelling, ELUCID’s post-millennial penchant for broken language and Holocene imagery elevates the archaic device of the skypager to the status of fetish item. One can see the huddled assemblage of survivors circled around the faint LCD glow on the annex floor, the acid rain falling through the collapsed roof.

18.

“14.4” drags us through the mass hysterics of Y2K mania with Saint Abdullah and The Lasso layering assorted ambient jazz touches to the Tron grid. ELUCID and SKECH185 fuck with the trellis modulation, raising a “Napster ’99” download speed from the titular 14.4kbps. They float over dial tones: “I dial in; you dial it down,” ELUCID says as he receives the signal from Armand Hammer’s “Landlines.” He’s charged with a “couple hundred-thousand watts,” so “do hold the line.” ELUCID and SKECH rap with “revolutionary millennial movements,” in the words of Eugene D. Genovese, “born in social catastrophe or in the fear of impending catastrophe.” Still, though, in the West African tradition, “time is cyclical and eternal; the religious tradition cannot then therefore readily provide for an apocalypse.” Fear all? Maybe it’s more fear none than we first thought.

I sometimes configure ELUCID as Aaron Dilloway (of Wolf Eyes, and—for our purposes here at present—their 2006 limited-release Dog Jaw) with a contact mic—full-contact stage presence | kilowatts killing | bringing the pain in a really real way. He wades in distortion, awash in both antiquated and active teknology (“*69—hit redial,” he remarks on “XOLO”). Hell is populated with tek—yottabytes of it like motes in sunlight, refracting his digipoetics. He announces proudly, “Afrika Islam loop in the key of my Lord,” which is a permanent—nearly park jamming—register for him to operate within. He dials in to Zulu Beats on WHBI 105.9 in New Jeruzalem and cracks codes for the afterfuture.

19. THE HAINTS OF HAM RADIO

Never polemical, ELUCID makes aslant references to oppressive histories, dating back antediluvian. One second he’s “in ya sundown town holding [his] dick dolo,” and the next he’s bouncing to bear witness to an “illegal chokehold.” He time travels from crabgrass frontiers to a sidewalk slab on Staten Island. He may be “too old to comfortably rock logos,” but he’s in-the-ever-know [and the ever-now] of former lives—he embodies Gift of Gab running from Feds in his red Pro-Keds, and he hits the racks of Saks Fifth Avenue with the Lo Lifes. Nowadays, though, he’s Naomi Klein’s No Logo incarnate. In another nanosec, he’s a po-mo narcocorrido singer reading “the note like Chalino, except it’s off the SIM card.” He’s hopping through traversable wormholes of genealogical blues “from Ham to Cush to Nimrod.” Settle our assassin’s eyes on Ham, hm?

In A Season in Hell, Rimbaud “set out in search of the true kingdom of the children of Ham.” Wyatt Mason argues that part of Rimbaud’s legend can be attributed to the rumors of him as “the scoundrel who sold slaves in Africa.” Though it’s accurate that Rimbaud was free roaming, sub-Saharan, his vagabondage through the Horn of Africa might not have included slave-trading—that point is disputed by his biographers. In The Rebel (1951), Camus called Rimbaud a “bourgeois trader” of percussion rifles and Ethiopian coffee, but made no mention of slaves. In 1994, China Achebe stated that “[w]hen Rimbaud became a slave trader, he stopped writing poetry” because poetry and slave trading “cannot be bedfellows.” When he wasn’t tagging up the Luxor Temple on a lark in Egypt or running guns across the border into Shewa land, Rimbaud’s travelogue was interlarded with diagnoses of typhoid, synovitis, and osteosarcoma—his right leg eventually lopped off. Perhaps we can ascribe his disease-ridden body to A Season in Hell’s most profane moments, such as when he writes, “I’m an animal, a nxggxr. But I can be saved. You’re all fake nxggxrs…”

The so-called “curse of Ham,” a blasphemy on Black people courtesy of Christian whites, has long contaminated the discourse—a shibboleth adorning the flowstones and helictites of the teknohell. “According to the scriptural defense of slavery,” Eugene D. Genovese writes in Roll Jordan Roll: The World the Slaves Made (1974), “...the enslavement of the blacks by the whites fulfilled the biblical curse of Ham.” But Genovese’s research indicates “the slaves did not view their predicament as punishment for the collective sin of black people. No amount of white propaganda could bring them to accept such an idea.” When ELUCID talks of “hammers hang[ing] on loop” on “THE WORLD IS DOG,” or “hammers out the Hummer” on “VOICE 2 SKULL,” I construe this cargo pants weaponry, this pakinamac in the back of the Ac’ (or Hummer), as a means of countering white propaganda, comparable to Treach’s chainsaw or Havoc’s scythe. Throughout REVELATOR, we find ELUCID going ham—hard as a motherfucker—but ELUCID’s too humble for any Tisci gilded throne. Instead, think of him as John Henry driving steel through the carpal tunnels of sinners and thieves. He sings a Scaramangan screed as he works, something gleaned from Seven Eyes, Seven Horns (1998): “Alphabetic hammer, magnetic grammar.”

ELUCID advances with “apocalyptic movement,” which Derrida defines as “the gesture of denuding or of affording sight,” a gesture which is sometimes “more guilty or more dangerous,” such as when Noah gets krunk in his tent and “Ham sees his father’s genitals.” ELUCID sees through the myths, the slander; instead, he exposes us to a soundtrack of staticky swells as he ascends out of the teknohell. I imagine the noise is a replication of what Joyce’s radio in Finnegans Wake (1939) sounds like. Here’s that signal recounted superlatively:

tolvtubular high fidelity daildialler, as modem as tomorrow afternoon and in appearance up to the minute…equipped with supershielded umbrella antennas for distance getting and connected by the magnetic links of a Bellini-Tosti coupling system with a vitaltone speaker, capable of capturing skybuddies, harbour craft emittences, key clickings, vaticum cleaners, due to woman formed mobile or man made static and bawling the whowle shack and wobble down in an eliminium sounds pound so as to serve him up a melegotumy marygoraumd, eclectrically filtered for allirish earths and ohmes.

In Kodwo Eshun’s More Brilliant Than the Sun (1998) | [“MBTTS,” ahem], he writes that “Long-distance telecom systems intensifies sensations of imminent Revelation.” Oh, indeed.

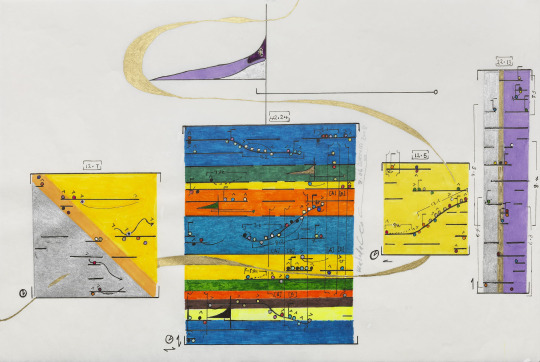

20. POST-INDUSTRIAL DOOM GOSPEL FOR THE GODLESS

On “Old Magic,” ELUCID announced himself as the “revelator, armed and dangerous,” so nothing he does on this album should come as a surprise. This lot of doom gospel spells shatters expectations, though. “I’ve been revelatin’” is what he told us on “Smile Lines,” and he’s yet to cease or even slow. The Book of the Seven Seals bulges, busting its binding and bending back its raised bands. REVELATOR, lyrics transcribed and beats notated in neumes, passes as ELUCID’s Book of Revelation.

I see it all, Michael Gira throat-sings. I see it all I see it all I see it all I see it all I see it all… over the sunn oh godspeed charnelhouse chanting and gunmetal grind of SWANS’ “The Seer” (2012). ELUCID is all-seeing as well—omniscient shit. It wasn’t always this way. On “Blame the Devil” from Save Yourself, ELUCID admitted that “revelation had [him] spooked.” In his preface to The Adventures of the Black Girl in Her Search for God (1932), George Bernard Shaw describes the Book as “a curious record of the visions of a drug addict which was absurdly admitted to the canon under the title of Revelation,” which only adds to the terror for an ’80s child who grew up with crushed crack vials underfoot.

On “Blame the Devil,” ELUCID saw the “seven eyes, seven crows” and “was lost.” “Now I’m found,” he would continue, “End of days—amazing time, / Everybody’s got a word—mine just happens to rhyme.” No longer cowering in church corners, surrounded by the congregants of what he has called a “death cult,” ELUCID’s Revelation remix has a liberation theology reverb. Pablo Richard’s Apocalypse: A People’s Commentary on The Book of Revelation (1995) places the curious record in the context of revolutionary power:

Revelation arises in a time of persecution—and particularly amid situations of chaos, exclusion, and ongoing oppression…. Revelation transmits a spirituality of resistance and offers guidance for organizing an alternative world…. Revelation is wrath and punishment for the oppressors, but good news (gospel) for those excluded and oppressed by the empire of the beast…. Revelation teaches us to imagine the present and final eschatology with a sense of joy and hope…. The book of Revelation is helping to create a new historical and liberating language.

21.