#theology and geometry

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

He looks like a yassified Ignatius Reilly, and based on the time I wound up interacting with him on The App Formerly Known As Twitter, I think he'd take that as a compliment, at least the "Ignatius" part of it. He may not even know what "yassification" is, or wish to know.

(He told me the "human pet" thing was not in fact meant as a metaphor for gender-affirming surgery. I think it's about declawing, which would make it a point on which his sense of theology and geometry matches mine, for all that he and I draw the lines of taste and decency in some very different places.)

#wait this is human pet guy????? he is his own caricature#<< antaresferen#the cybersmith#human pet guy#Ignatius J. Reilly#theology and geometry

330 notes

·

View notes

Text

#esoteric#mystery schools#photon belt#spiritual initiation#theology#spiritual awakening#spiritual journey#self love#higher self#alchemy#sacred realm#sacred geometry#symbols#secrets#self worth#self help#self improvement#communication#consciousness#connection#ancient history#awareness#astrology

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why the Number Zero Changed Everything

Zero: a concept so foundational to modern mathematics, science, and technology that we often forget it wasn’t always there. Its presence in our world today seems obvious, but its journey from controversial abstraction to indispensable tool has shaped entire civilizations.

1. The Birth of Zero: A Revolutionary Idea

The concept of zero didn't exist in many ancient cultures. For example, the Greeks, despite their advancements in geometry and number theory, rejected the idea of a placeholder for nothingness. The Babylonians had a placeholder symbol (a space or two slashes) for zero, but they didn't treat it as a number. It wasn't until Indian mathematicians in the 5th century, like Brahmagupta, that zero was truly conceptualized and treated as a number with its own properties.

Zero was initially used as a place-holder in the decimal system, but soon evolved into a full-fledged number with mathematical properties, marking a huge leap in human cognition.

2. The Birth of Algebra

Imagine trying to solve equations like x + 5 = 0 without zero. With zero, algebra becomes solvable, opening up entire fields of study. Before zero’s arrival, solving equations involving unknowns was rudimentary, relying on geometric methods. The Indian mathematician Brahmagupta (again) was one of the first to establish rules for zero in algebraic operations, such as:

x + 0 = x (additive identity)

x × 0 = 0 (multiplicative property)

These properties allowed algebra to evolve into a system of abstract thought rather than just arithmetic, transforming the ways we understand equations, functions, and polynomials.

3. Calculus and Zero: A Relationship Built on Limits

Without zero, the foundation of calculus—limits, derivatives, and integrals—wouldn’t exist. The limit concept is intrinsically tied to approaching zero as a boundary. In differentiation, the derivative of a function f(x) is defined as:

f'(x) = \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{f(x+h) - f(x)}{h}

This limit process hinges on the ability to manipulate and conceptualize zero in infinitesimal quantities. Similarly, integrals, which form the backbone of area under curves and summation of continuous data, rely on summing infinitely small quantities—essentially working with zero.

Without the concept of zero, we wouldn’t have the means to rigorously define rates of change or accumulation, effectively stalling physics, engineering, and economics.

4. Zero and the Concept of Nothingness: The Philosophical Impact

Zero is more than just a number; it’s an idea that forces us to confront nothingness. Its acceptance was met with philosophical resistance in ancient times. How could "nothing" be real? How could nothing be useful in equations? But once mathematicians recognized zero as a number in its own right, it transformed entire philosophical discussions. It even challenged ideas in theology (e.g., the nature of creation and void).

In set theory, zero is the size of the empty set—the set that contains no elements. But without zero, there would be no way to express or manipulate sets of nothing. Thus, zero's philosophical acceptance paved the way for advanced theories in logic and mathematical foundations.

5. The Computing Revolution: Zero as a Binary Foundation

Fast forward to today. Every piece of digital technology—from computers to smartphones—relies on binary systems: sequences of 1s and 0s. These two digits are the fundamental building blocks of computer operations. The idea of Boolean algebra, where values are either true (1) or false (0), is deeply rooted in zero’s ability to represent "nothing" or "off."

The computational world relies on logical gates, where zero is interpreted as false, allowing us to build anything from a basic calculator to the complex AI systems that drive modern technology. Zero, in this context, is as important as one—and it's been essential in shaping the digital age.

6. Zero and Its Role in Modern Fields

In modern fields like physics and economics, zero plays a crucial role in explaining natural phenomena and building theories. For instance:

In physics, zero-point energy (the lowest possible energy state) describes phenomena in quantum mechanics and cosmology.

In economics, zero is the reference point for economic equilibrium, and the concept of "breaking even" relies on zero profit/loss.

Zero allows us to make sense of the world, whether we’re measuring the empty vacuum of space or examining the marginal cost of producing one more unit in economics.

7. The Mathematical Utility of Zero

Zero is essential in defining negative numbers. Without zero as the boundary between positive and negative values, our number system would collapse. The number line itself relies on zero as the anchor point, dividing positive and negative values. Vector spaces, a fundamental structure in linear algebra, depend on the concept of a zero vector as the additive identity.

The coordinate system and graphs we use to model data in statistics, geometry, and trigonometry would not function as we know them today. Without zero, there could be no Cartesian plane, and concepts like distance, midpoint, and slope would be incoherent.

#mathematics#math#mathematician#mathblr#mathposting#calculus#geometry#algebra#numbertheory#mathart#STEM#science#academia#Academic Life#math academia#math academics#math is beautiful#math graphs#math chaos#math elegance#education#technology#statistics#data analytics#math quotes#math is fun#math student#STEM student#math education#math community

49 notes

·

View notes

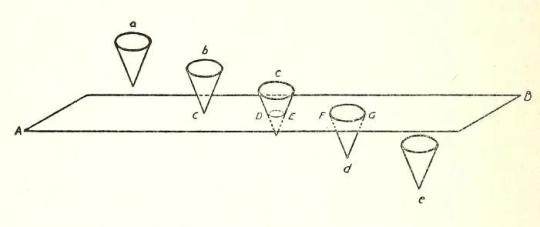

Photo

The Fourth Dimension and the Bible

?!

Dangerously close to my own theology.

The Fourth Dimension and the Bible (1922) — William Granville’s valiant attempt to explain the more mysterious aspects of the Bible through the rigours of pure mathematics: https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/the-fourth-dimension-and-the-bible-1922

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

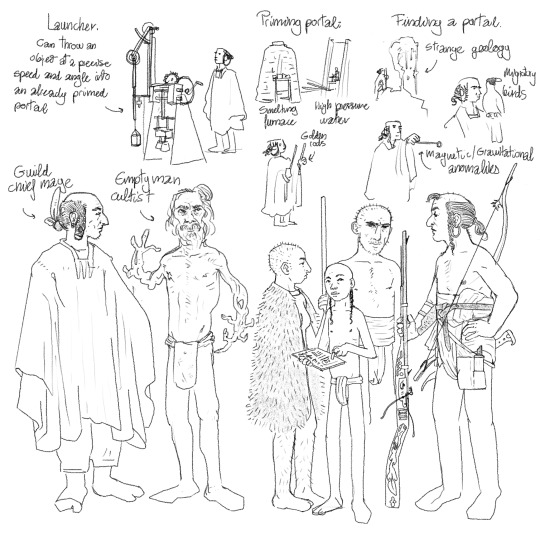

Silly doodles about the people from the Twisted Islands.

I added some goofy sketches about operating portals (I will eventually do a full post about it) and two mages:

-Guild chief mage: mages are at the top of the guild's hirearchy and work as portal operators, traders/acountants and ingeneers. They are people that have spent years since childhood under a strict education program and are very knowledgable about geometry, physics and the Island's theology and philosophy. Not everyone can become a chief mage, and only the apprentices with the most potential undergo the full training. Most mages now use gold rods set at specific angles in tripods to prime a portal and then use a launcher to make an item go through it. Launchers are adjustable polley systems that can be set so that the cargo breaks the speed of sound just at the right spot and at the right angle, so that it can travel through the portal.

Hydraulic systems are often used for bigger cargo, wich apply energy in the form of pressure rather than speed.

All chief mages are part of the guild system and loyal to the Twisted Islands' confederation. They keep their secrets and work for the guild's enrichment.

-Empty man cultists. I won't explain their whole religion here as I will do another post about the world's religion but they are basically a death cult wich follows the teachings of the empty man. The empty man was a prophet wich, influenced by another religion of the continent, seeked to revitalize the values of the old religion of the islands and their old way of life. They practice extreme isolation and poverty and try to further investigate portals, as they believe their use should not only be trade. Many of them practice portal mutilation, wich is to put a certain limb into a portal right when it's going to shut close. The cultist I have drawn has portal wounds in both of his arms. These limbs now become "twisted". Most cultists are former guild mages wich want to know even more about the portals. When an arm is "twisted", it can be used to prime or straight up open a portal if the user has the right training and mental control and the arm was twisted in just the right way. Empty man cultists are shunned by the guild system and many live in remote island monasteries. They run the portal trade black market and are contacted by certain clients to transport items without the knowledge and taxation of the twisted island's federation.

#this was just straight up rambling but I hope you liked it#fantasy worldbuilding#worldbuilding#fantasy art#art#concept art#fantasy#culture#mage#my artwork#magic system#magic#portal#worldbuilding project#yzegem#encounters in the frontier#twisted islands#empty man

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Magnificent desolation" // Enda Kelly

Click below to see a few craters identified and some info about them!

From top left to bottom right:

Clavius crater is named after Christopher Clavius (1538-1612), a Jesuit German mathematician and astronomer. He was one of the members of the commission that approved the Gregorian calendar.

Rutherfurd crater is named after Lewis Rutherfurd (1816-1892), an American lawyer and astronomer, and pioneering astrophotographer. He produced high quality photographs of the Sun, Moon, and the planets, as well as stars and star clusters. Notably, he was one of the founding members of the National Academy of Sciences in 1863.

Cysalus crater is named for Johann Baptist Cysat (c. 1587-1657), a Swiss Jesuit mathematician and astronomer. His most important work was on comets, particularly the comet of 1618, demonstrating that it orbited around the Sun in a parabolic orbit.

Moretus crater is named for Theodorus Moretus (1602-1667), a Flemish Jesuit mathematician who made significant strides in math, geometry, physics, optics, and theology.

#astronomy#astrophotography#solar system#moon#the moon#luna#crater#lunar craters#clavius#rutherfurd#cysalus#moretus#history#etymology

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Socialism: Utopian and Scientific - Part 3

[ First | Prev | Table of Contents | Next ]

"Materialism is the natural-born son of Great Britain. Already the British schoolman, Duns Scotus, asked, 'whether it was impossible for the matter to think?'

"In order to effect this miracle, he took refuge in God's omnipotence — i.e., he made theology preach materialism. Moreover, he was a nominalist. the first form of materialism, is chiefly found among the English schoolmen. "The real progenitor of English materialism is Bacon. To him, natural philosophy is the only true philosophy, and physics based upon the experience of the senses is the chiefest part of natural philosophy. Anaxagoras and his homoiomeriae, Democritus and his atoms, he often quotes as his authorities. According to him, the senses are infallible and the source of all knowledge. All science is based on experience, and consists in subjecting the data furnished by the senses to a rational method of investigation. Induction, analysis, comparison, observation, experiment, are the principal forms of such a rational method. Among the qualities inherent in matter, motion is the first and foremost, not only in the form of mechanical and mathematical motion, but chiefly in the form of an impulse, a vital spirit, a tension — or a 'qual', to use a term of Jakob Böhme's [2] — of matter.

[2] "Qual" is a philosophical play upon words. Qual literally means torture, a pain which drives to action of some kind; at the same time, the mystic Bohme puts into the German word something of the meaning of the Latin qualitas; his "qual" was the activating principle arising from, and promoting in its turn, the spontaneous development of the thing, relation, or person subject to it, in contradistinction to a pain inflicted from without. [Note by Engels to the English Edition]

"In Bacon, its first creator, materialism still occludes within itself the germs of a many-sided development. On the one hand, matter, surrounded by a sensuous, poetic glamor, seems to attract man's whole entity by winning smiles. On the other, the aphoristically formulated doctrine pullulates with inconsistencies imported from theology. "In its further evolution, materialism becomes one-sided. Hobbes is the man who systematizes Baconian materialism. Knowledge based upon the senses loses its poetic blossom, it passes into the abstract experience of the mathematician; geometry is proclaimed as the queen of sciences. Materialism takes to misanthropy. If it is to overcome its opponent, misanthropic, flashless spiritualism, and that on the latter's own ground, materialism has to chastise its own flesh and turn ascetic. Thus, from a sensual, it passes into an intellectual, entity; but thus, too, it evolves all the consistency, regardless of consequences, characteristic of the intellect. "Hobbes, as Bacon's continuator, argues thus: if all human knowledge is furnished by the senses, then our concepts and ideas are but the phantoms, divested of their sensual forms, of the real world. Philosophy can but give names to these phantoms. One name may be applied to more than one of them. There may even be names of names. It would imply a contradiction if, on the one hand, we maintained that all ideas had their origin in the world of sensation, and, on the other, that a word was more than a word; that, besides the beings known to us by our senses, beings which are one and all individuals, there existed also beings of a general, not individual, nature. An unbodily substance is the same absurdity as an unbodily body. Body, being, substance, are but different terms for the same reality. It is impossible to separate thought from matter that thinks. This matter is the substratum of all changes going on in the world. The word infinite is meaningless, unless it states that our mind is capable of performing an endless process of addition. Only material things being perceptible to us, we cannot know anything about the existence of God. My own existence alone is certain. Every human passion is a mechanical movement, which has a beginning and an end. The objects of impulse are what we call good. Man is subject to the same laws as nature. Power and freedom are identical. "Hobbes had systematized Bacon, without, however, furnishing a proof for Bacon's fundamental principle, the origin of all human knowledge from the world of sensation. It was Locke who, in his Essay on the Human Understanding, supplied this proof. "Hobbes had shattered the theistic prejudices of Baconian materialism; Collins, Dodwell, Coward, Hartley, Priestley, similarly shattered the last theological bars that still hemmed in Locke's sensationalism. At all events, for practical materialists, Deism is but an easy-going way of getting rid of religion."

Karl Marx The Holy Family p. 201 - 204

[ First | Prev | Table of Contents | Next ]

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

What remains today of Newton's fundamental breakthrough? Modern life, our system of education founded on the requirements of punctuality, scholastic exercises on the charts of train schedules, geographic maps—all this inculcates in us, from childhood, a very Newtonian idea of space and time. This is why we have such difficulty perceiving the absurdity of questions such as"What lies beyond the limits of the universe?" or "What existed before the creation of the world—or before the Big Bang?" We marvel at the apparent modernness of Saint Augustine, who was already addressing similar questions fifteen centuries ago: "Time did not exist before heavens and earth.” But few among us know or have really assimilated the Kantian critique of the concepts of space and time. Kant constructed this critique specifically to chart the boundaries between knowledge and faith, to free science from metaphysical presuppositions, to deliver geometry from the shadow of theology to which Newton had in fact ascribed it. For Kant, space and time are not things in themselves but "forms of intuition”—in other words, they constitute a canvas that allows us to decipher the existence of the world. According to Kant, things "in themselves" are neither in space nor in time. It is the human mind that, in the very act of perception, superimposes these categories, which are its own and without which perception would be impossible. This does not exactly mean that space and time are illusions or pure inventions of the human mind. These frameworks are imposed on us through empirical contact with nature and are not, therefore, "arbitrary.” They no more belong to things in themselves than they belong to the mind alone; rather, they exist because of the dialogue between the mind and things. They are, in the final analysis, an unavoidable product of motion itself by means of which the mind searches to apprehend—to understand—the outside world.

Rémy Lestienne, The Children of Time: Causality, Entropy, Becoming

#quote#Rémy Lestienne#Lestienne#Remy Lestienne#time#science#Kant#Immanuel Kant#St Augustine#theology#Saint Augustine#religion#physics#entropy#causality#space#space-time#spacetime#mind#education#Newton#Isaac Newton#philosophy

174 notes

·

View notes

Note

could you talk more about constantinople university?

Hey, I am sorry for the very late reply. This past week was very difficult. Anyway I assume you are asking about the main educational institution in Constantinople at the times of the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire.

First of all, I should start this by saying a few basic things about the educational system in the Byzantine Empire. The Byzantine Empire had the best primary education in Europe and one of the best in the known world at the time. All peasant children were able to receive education, that is, both boys AND girls, which was unheard of in most other places. As a result peasant men and women attained a satisfactory level of education for the standards of the time.

Higher education was received mainly through private tutoring, which means that this was in fact a privilege of the rich and upper middle classes. Private tutors could also be hired by women who, even though they could not work in professions of a high academic profile (except they could become doctors for women), were still able to educate and improve on themselves just for the sake of it.

The University of Constantinople

When the Roman Empire was spilt in two in 395 AD, the Hellenized eastern part of the empire already had a few famed schools in some of its greatest cities (i.e Academy of Athens, the schools in Alexandria, Antioch, Beirut, Gaza). Those remained the hotspots for higher education for a few centuries, mostly until the Arab conquest in the 7th century.

In 425 AD Emperor Theodosius II founded the state funded Pandidakterion (Πανδιδακτήριον) in the Capitolium of Constantinople, what is supposed to be the original form of the University of Constantinople. According to some sources the concept of this school was actively supported by Theodosius's sister Pulcheria and his empress wife Aelia Eudocia the Athenian. The Pandidakterion was not exactly a university in the modern sense; it initially did not offer courses in various fields of sciences and arts from which students could choose their studies and career. The Pandidakterion's aim was to train specifically those who pursued a career as civil servants for the administration of the Empire and the secular matters concerning the Church. The courses taught were: Greek Grammar, Latin Grammar, Law, Philosophy (students were taught Aristotle and particularly Plato) and Rhetoric (with an emphasis in Greek rather than Latin rhetoric). That last one was considered the most challenging course. Pandidakterion did not teach Theology; this was the responsibility of the Patriarchal Academy. There are sources which list the Pandidakterion indeed as a university though and perhaps it is the closest thing to a university you could have gotten that early in time.

Meanwhile, in Constantinople and other large cities of the empire there were various academies of theology, arts and sciences but those were not universities. Also, as stated above, it was after the 7th century that Constantinople became the center of Byzantine higher education. In the 7th and the 8th century the Byzantine empire was attacked by Slavs, Arabs, Avars and Bulgars, loosening the focus to education. All this and the Iconoclasm seemed to have had adverse yet non permanent effects on the function of the university. The dynasty of the Isaurians (717 - 802) renamed "Πανδιδακτήριον" to "Οικουμενικόν Διδασκαλείον" (Ecumenical School).

The 9th century signifies a new prosperous era for higher education. There are some conflicting sources for that time - according to some the Pandidakterion was moved to the Palace of Magnaura and according to others this is an erroneous conflation of the Pandidakterion in the Capitolium with the new University of the Palace Hall of Magnaura (Εκπαιδευτήριον της Μαγναύρας). Whatever the case is, this renovated or entirely new school was founded by Vardas (842 - 867), uncle of Emperor Michael III. Mathematics, geometry, astronomy and music were added to the courses. The school then was managed by Leon the Mathematician (790 - 869) from Thessaly. Studying there was free.

In the 10th century, Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogennitos promoted the Pandidakterion and supported it financially.

In 1046 Constantine IX Monomachos reformed the actual Pandidakterion of the Capitolium into two large faculties operating in it; the "Διδασκαλείον των Νόμων" (School of Law) and the "Γυμνάσιον" (Gymnasion). The School of Law retained its purpose to train the civil servants whereas the Gymnasion taught all the other sciences (i.e philosophy, mathematics, astronomy, music). At the time Pandidakterion had a clear resemblance to a typical university. The principal of the Law School was called "Νομοφύλαξ" (nomophýlax), Guard of Law. A notable nomophylax was Ioannis VIII Xiphilinos (1010 - 1075) who was an intellectual, jurist and later Patriarch of Constantinople. The principal of the Gymansion was called "Ύπατος των Φιλοσόφων" (Consul of the Philosophers). Notable Gymnasion principals were Michael Psellos (1018 - 1078), one of the most broadly educated people to have lived in the Byzantine empire or the middle ages even. Psellos was a Greek monk, savant, courtier, writer, philosopher, historian, music theorist, poet, astronomer, doctor and diplomat. He was notoriously horrible at Latin although given the extent of his studies it is unclear to modern historians whether his Latin knowledge was genuinely poor or he played it up as an act of disdain (he was totally the type to do that). Another notable principal was Ioannis Italos (John the Italian), a half-Italian half-Greek from Calabria, who was Psellos' student in classical Greek Philosophy.

The function of the Pandidakterion as well as all high education in the Byzantine Empire was ceased after the capture of Cosntantinople by the Crusaders in 1204. The Byzantine royalty did however survive through the small Empire of Nicaea and they supported financially the private tutors. After the liberation of Constantinople by the Byzantines in 1261, there were efforts to restore the higher education institutions. Michael VIII Palaeologos, the emperor who recovered the city, reopened the university and appointed as principals Georgios Akropolitis, a historian and statesman, for the Law School and Georgios Pachymeris, a historian, philosopher, theologist, mathematician and music theorist, for the Philosophy School (Gymnasion).

However, the University never returned to its previous status and smooth function. It slowly passed fully under the Church's management in order to survive, while the rest of the teaching was again done by private teachers. This was the case all the way to the Fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. Only one day after the capture of Constantinople, Sultan Mehmed II founded a madrasa as the primary educational institution of the city. Madrasa is an arabic name for an Islamic higher education religious institution. In 1846, this insitution was reformed into a university in the likes of the typical Western European universities. Until 1930 many old sources referred to this university confusingly as "University of Constantinople" because the city's name had not actually changed until that time. However, this institution was not the same to the Pandidakterion, the university of the Byzantine Age. In 1930, the city's name was officially changed from Constantinople to Istanbul and the university was renamed in 1933 to "Istanbul University" and it operates like this, being the first university of the Republic of Turkey.

What about the Pandidakterion though, the first University of Constantinople? Well, it ceased to exist, unlike the Patriarchal Academy which re-opened one year after the Fall of Constantinople, in 1454, refounded as the Phanar Greek Orthodox College, which operates to this day.

*Forgive any potential inaccuracies, some sources were really conflicting, especially about the possible Pandidakterion and the Magnaura School mix up.

#history#middle ages#byzantine empire#eastern roman empire#byzantine history#greek history#constantinople#anon#ask#long text

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

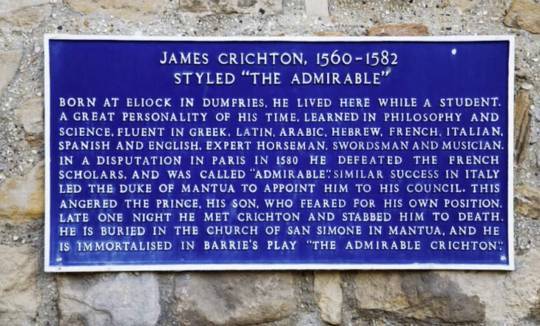

On 19th August 1560 the Scottish scholar and poet, James Crichton, was born.

Soldier, scholar, poet and athlete, he was a graduate of St Andrews University and a tutor of King James VI. James Crichton, known as the Admirable Crichton, was a Scottish polymath, a latin term that translates to “universal man”, basically he was good at everything!

Crichton wasnoted for his extraordinary accomplishments in languages, the arts, and sciences. One of the most gifted individuals of the 16th century, James Crichton of Clunie Perthshire, was the son of Robert Crichton of Eliok, Lord Advocate of Scotland, and Elizabeth Stewart, from whose line James could claim Royal descent.

At the age of eight Crichton’s eloquence in his native vernacular was compared with that of Demosthenes and Cicero. By fifteen he knew “perfectly” Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Arabic, and Syriac; and commanded native conversational fluency in Spanish, French, Italian, “Dutch”, Flemish, and, oh, “Sclavonian”, don’t worry I looked it up for us, it’s basically Slovenian.

That was the mere beginning of Crichton’s admirableness. He was also a champion athlete, a horseman, a fencer, a dancer, a singer of rare voice, and the master of most known wind and string instruments. His St. Andrews professor, Rutherford, a noted commentator, judged him to be one of the leading philosophers of the era.

After sucking all the available education to him in Scotland, it was only natural he should start on mainland Europe, he studied in France at the College of Navarre at the University of Paris. Here the young Scotsman cut a broad swath, though according to his jealous fellows his arenas of greatest activity were the tavernia’s and the whorehouses, rather than the lecture hall. Young Crichton did like the ladies, who in turn found him most–admirable.

He may have been liked by the ladies, but nobody likes a big heid, and that is how Crichton must have come across to many, nowadays he would have been one of the Chasers, or an Egghead on our TV screens, but back in the 16th century there were no such outlets for Crichton to show his big heid off, so he had posters printed up declaring that on a day six weeks hence, at nine in the morning, in the main hall of the College of Navarre, he intended to present himself to dispute with all comers all questions put to him regarding any subject. He had these put up on all the appropriate notice boards and church doors, before disappearing into the red light district to prepare himself for the contest. His adversaries had to quit laughing when on the appointed day Crichton appeared as advertised and bested the greatest local experts in grammar, mathematics, geometry, music, astronomy, logic, and theology.

The Crichton Show, having conquered Paris, moved next to the Italian peninsula. The young Scot performed memorable feats of academic disputation first in Rome and then in Venice. There he became fast friends with the famous scholar-printer Aldus Munitius, who is a credible witness to some of his more amazing intellectual performances. One of his ways of showing off was giving off the cuff instances of Comedic verse, a sort of Stand Up routine, but with that Crichton twist, the odes he told were in Latin!

Tradition has it on the street in Mantua one night he was accosted by four swordsmen, with superb sword play Crichton disarmed them all and forced them to show their faces. One of them, their leader indeed, turned out to be one of his pupils and prodigy, Vincenzo Gonzaga who was the son of The Duke of Mantua. Crichton was in the Duke’s employ and the youngster was jealous of the Scot, Crichton was also romantically linked to Vicenzo’s ex mistress. On seeing Vincenzo, Crichton instantly dropped to one knee and presented his sword, hilt first, to the prince, his master’s son. Vincenzo took the blade and with it stabbed Crichton cruelly through the heart, killing him instantly. James Crichton of Cluny was then in his twenty-second year.

There have been many accounts of Crichton in literature through the years since, mostly fictional but with hints of the story, the most famous is arguably the J M Barrie play, but the title of the play is the only semblance to the story of the Scottish Polymath.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Adoring Angels” by Benozzo Gozzoli (1459)

“Theology and Geometry” book cover, authored by Leslie Marsh (2022)

“Griffith”, by Kentaro Miura (2003-2005)

#christian core#catholic core#medieval core#renaissance#berserk#a confederacy of dunces#kentaro miura#griffith#grifis#ignatius j reilly#myrna minkoff#irene reilly#john kennedy toppe#burma jones#art#renaissance art#benozzo gozzoli#dante#the divine comedy

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Originally, there were seven traditional liberal arts taught in the Middle Ages and throughout the Renaissance, which were later codified in Rome: grammar, logic, rhetoric, arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy. A French painter, Coëtivy Master (Henri de Vulcop?), who was active between 1450 - 1485 and whom historians today still know very little about, painted this piece, Philosophy Presenting the Seven Liberal Arts to Boethius. Boethius was a Roman senator and philosopher from the Middle Ages who wrote about math, music, linguistics, theology, and logic.

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

#esoteric#mystery schools#photon belt#spiritual initiation#theology#spiritual awakening#spiritual journey#self love#higher self#alchemy#sacred realm#sacred geometry#spiritual path#spiritual awareness#awareness#astrology#natal chart#birth chart#astronomy

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Through the Ages

collected notes on a variety of background figures in Boralverse history, listed in chronological order.

Franco Cicala was the console of the maritime republic Jeans [Genoa] from 1119 until either 1122 or 1124 (records differ). The console being an elected position voted on by the local nobility, Franco would be followed intermittently by over a dozen consoli from among his descendants.

Andrew II was a martial-minded king of Markland [~Mercia; the Midlands] in the early fourteenth century. He succeeded his uncle, who is remembered as being far more diplomatic. Andrew II oversaw the Sack of Rexam [Wrexham] in 1301, an act which reignited the on-again off-again conflict between Markland and Wales known as the Mallor Wars. The original medieval building at St Brigid's Abbey was razed during this offensive.

Dewock Barclythe (1452-1539 N) was the Friar of Tremonnow [Monmouth] and for several decades the prime Factor of Records at the Brethin House there. Records of his correspondence with clergy and academics across western Europe have survived to the present day. These include some of the earliest attestations of dart [vector] geometry, and thus the beginnings of the unification of geometry and computation.

Lord Simon, Baron Monçating (b. 1770) was an intellectual, a notorious libertine of the Damvath melee, and an early proponent of Deviance Theology in Borland. He was of Warnine [Guaraní] descent through his mother. His family had been notorious for decades due to a protracted legal battle between his father and second cousin over the Barony of Haubrath. By the age of eighteen Simon could speak Latin, Dutch (and Warnine, according to his defamers), and he could play the clavier and the torriot [a bassoon-like wind instrument].

Marcio Dourao was a Portingale author and rabblerouser best remembered for his work Galatheus, or the Knowledge of Good and Evil. This collection of short stories pastiching Greek mythology was written in 1930 during the decade-long Portingale Anarchy. The title references the story of Galatea and Pygmalion. Galatheus was banned in neighbouring Vascony and Morrack for its background politics and, unofficially, for its throughline of gender exploration; neither polity had quite forgotten their roles in the traditionally-minded Modest Arrangement of the previous century.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

SAINTS&READING: FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 7, 2025

january25_february 7

St GREGORY THE THEOLOGIAN, ARCHBISHOP OF CONSTANTINOPLE (389)

Saint Gregory the Theologian, Archbishop of Constantinople, a great Father and teacher of the Church, was born into a Christian family of eminent lineage in the year 329, at Arianzos (not far from the city of Cappadocian Nazianzos). His father, also named Gregory (January 1), was Bishop of Nazianzus. The son is the Saint Gregory Nazianzus encountered in Patristic theology. His pious mother, Saint Nonna (August 5), prayed to God for a son, vowing to dedicate him to the Lord. Her prayer was answered, and she named her child Gregory.

When the child learned to read, his mother presented him with the Holy Scripture. Saint Gregory received a complete and extensive education: after working at home with his uncle Saint Amphilochius (November 23), an experienced teacher of rhetoric, he then studied in the schools of Nazianzos, Caesarea in Cappadocia, and Alexandria. Then the saint decided to go to Athens to complete his education.

On the way from Alexandria to Greece, a terrible storm raged for many days. Saint Gregory, who was just a catechumen at that time, feared that he would perish in the sea before being cleansed in the waters of Baptism. Saint Gregory lay in the ship’s stern for twenty days, beseeching the merciful God for salvation. He vowed to dedicate himself to God, and was saved when he invoked the name of the Lord.

Saint Gregory spent six years in Athens studying rhetoric, poetry, geometry, and astronomy. His teachers were the renowned pagan rhetoricians Gymorias and Proeresias. Saint Basil, the future Archbishop of Caesarea (January 1) also studied in Athens with Saint Gregory. They were such close friends that they seemed to be one soul in two bodies. Julian, the future emperor (361-363) and apostate from the Christian Faith, was studying philosophy in Athens at the same time.

Upon completing his education, Saint Gregory remained for a certain while at Athens as a teacher of rhetoric. He was also familiar with pagan philosophy and literature.

In 358 Saint Gregory quietly left Athens and returned to his parents at Nazianzus. At thirty-three years of age, he received Baptism from his father, who had been appointed Bishop of Nazianzus. Against his will, Saint Gregory was ordained to the holy priesthood by his father. However, when the elder Gregory wished to make him a bishop, he fled to join his friend Basil in Pontus. Saint Basil had organized a monastery in Pontus and had written to Gregory inviting him to come.

Saint Gregory remained with Saint Basil for several years. When his brother Saint Caesarius (March 9) died, he returned home to help his father administer his diocese. The local church was also in turmoil because of the Arian heresy. Saint Gregory had the difficult task of reconciling the bishop with his flock, who condemned their pastor for signing an ambiguous interpretation of the dogmas of the faith.

Saint Gregory convinced his father of the pernicious nature of Arianism, and strengthened him in Orthodoxy. At this time, Bishop Anthimus, who pretended to be Orthodox but was really a heretic, became Metropolitan of Tyana. Saint Basil had been consecrated as the Archbishop of Caesarea, Cappadocia. Anthimus wished to separate from Saint Basil and to divide the province of Cappadocia.

Saint Basil the Great made Saint Gregory bishop of the city of Sasima, a small town between Caesarea and Tyana. However, Saint Gregory remained at Nazianzos in order to assist his dying father, and he guided the flock of this city for a while after the death of his father in 374.

Upon the death of Patriarch Valentus of Constantinople in the year 378, a council of bishops invited Saint Gregory to help the Church of Constantinople, which at this time was ravaged by heretics. Obtaining the consent of Saint Basil the Great, Saint Gregory came to Constantinople to combat heresy. In the year 379 he began to serve and preach in a small church called “Anastasis” (“Resurrection”). Like David fighting the Philistines with a sling, Saint Gregory battled against impossible odds to defeat false doctrine.

Heretics were in the majority in the capital: Arians, Macedonians, and Appolinarians. The more he preached, the more did the number of heretics decrease, and the number of the Orthodox increased. On the night of Pascha (April 21, 379) when Saint Gregory was baptizing catechumens, a mob of armed heretics burst into the church and cast stones at the Orthodox, killing one bishop and wounding Saint Gregory. But the fortitude and mildness of the saint were his armor, and his words converted many to the Orthodox Church.

Saint Gregory’s literary works (orations, letters, poems) show him as a worthy preacher of the truth of Christ. He had a literary gift, and the saint sought to offer his talent to God the Word: “I offer this gift to my God, I dedicate this gift to Him. Only this remains to me as my treasure. I gave up everything else at the command of the Spirit. I gave all that I had to obtain the pearl of great price. Only in words do I master it, as a servant of the Word. I would never intentionally wish to disdain this wealth. I esteem it, I set value by it, I am comforted by it more than others are comforted by all the treasures of the world. It is the companion of all my life, a good counselor and converser; a guide on the way to Heaven and a fervent co-ascetic.” In order to preach the Word of God properly, the saint carefully prepared and revised his works.

In five sermons, or “Theological Orations,” Saint Gregory first of all defines the characteristics of a theologian, and who may theologize. Only those who are experienced can properly reason about God, those who are successful at contemplation and, most importantly, who are pure in soul and body, and utterly selfless. To reason about God properly is possible only for one who enters into it with fervor and reverence.

Explaining that God has concealed His Essence from mankind, Saint Gregory demonstrates that it is impossible for those in the flesh to view mental objects without a mixture of the corporeal. Talking about God in a positive sense is possible only when we become free from the external impressions of things and from their effects, when our guide, the mind, does not adhere to impure transitory images. Answering the Eunomians, who would presume to grasp God’s Essence through logical speculation, the saint declared that man perceives God when the mind and reason become godlike and divine, i.e. when the image ascends to its Archetype. (Or. 28:17). Furthermore, the example of the Old Testament patriarchs and prophets and also the Apostles has demonstrated, that the Essence of God is incomprehensible for mortal man. Saint Gregory cited the futile sophistry of Eunomios: “God begat the Son either through His will, or contrary to will. If He begat contrary to will, then He underwent constraint. If by His will, then the Son is the Son of His intent.”

Confuting such reasoning, Saint Gregory points out the harm it does to man: “You yourself, who speak so thoughtlessly, were you begotten voluntarily or involuntarily by your father? If involuntarily, then your father was under the sway of some tyrant. Who? You can hardly say it was nature, for nature is tolerant of chastity. If it was voluntarily, then by a few syllables you deprive yourself of your father, for thus you are shown to be the son of Will, and not of your father” (Or. 29:6).

Saint Gregory then turns to Holy Scripture, with particular attention examining a place where it points out the Divine Nature of the Son of God. Saint Gregory’s interpretations of Holy Scripture are devoted to revealing that the divine power of the Savior was actualized even when He assumed an impaired human nature for the salvation of mankind.

The first of Saint Gregory’s Five Theological Orations is devoted to arguments against the Eunomians for their blasphemy of the Holy Spirit. Closely examining everything that is said in the Gospel about the Third Person of the Most Holy Trinity, the saint refutes the heresy of Eunomios, which rejected the divinity of the Holy Spirit. He comes to two fundamental conclusions. First, in reading Holy Scripture, it is necessary to reject blind literalism and to try and understand its spiritual sense. Second, in the Old Testament the Holy Spirit operated in a hidden way. “Now the Spirit Himself dwells among us and makes the manifestation of Himself more certain. It was not safe, as long as they did not acknowledge the divinity of the Father, to proclaim openly that of the Son; and as long as the divinity of the Son was not accepted, they could not, to express it somewhat boldly, impose on us the burden of the Holy Spirit” (Or. 31:26).

The divinity of the Holy Spirit is a sublime subject. “Look at these facts: Christ is born, the Holy Spirit is His Forerunner. Christ is baptized, the Spirit bears witness to this... Christ works miracles, the Spirit accompanies them. Christ ascends, the Spirit takes His place. What great things are there in the idea of God which are not in His power? What titles appertaining to God do not apply also to Him, except for Unbegotten and Begotten? I tremble when I think of such an abundance of titles, and how many Names they blaspheme, those who revolt against the Spirit!” (Or. 31:29).

The Orations of Saint Gregory are not limited only to this topic. He also wrote Panegyrics on Saints, Festal Orations, two invectives against Julian the Apostate, “two pillars, on which the impiety of Julian is indelibly written for posterity,” and various orations on other topics. In all, forty-five of Saint Gregory’s orations have been preserved.

The letters of the saint compare favorably with his best theological works. All of them are clear, yet concise. In his poems as in all things, Saint Gregory focused on Christ. “If the lengthy tracts of the heretics are new Psalters at variance with David, and the pretty verses they honor are like a third testament, then we also shall sing Psalms, and begin to write much and compose poetic meters,” said the saint. Of his poetic gift the saint wrote: “I am an organ of the Lord, and sweetly... do I glorify the King, all a-tremble before Him.”

The fame of the Orthodox preacher spread through East and West. But the saint lived in the capital as though he still lived in the wilderness: “his food was food of the wilderness; his clothing was whatever necessary. He made visitations without pretense, and though in proximity of the court, he sought nothing from the court.”

The saint received a shock when he was ill. One whom he considered as his friend, the philosopher Maximus, was consecrated at Constantinople in Saint Gregory’s place. Struck by the ingratitude of Maximus, the saint decided to resign the cathedral, but his faithful flock restrained him from it. The people threw the usurper out of the city. On November 24, 380 the holy emperor Theodosius arrived in the capital and, in enforcing his decree against the heretics, the main church was returned to the Orthodox, with Saint Gregory making a solemn entrance. An attempt on the life of Saint Gregory was planned, but instead the assassin appeared before the saint with tears of repentance.

At the Second Ecumenical Council in 381, Saint Gregory was chosen as Patriarch of Constantinople. After the death of Patriarch Meletius of Antioch, Saint Gregory presided at the Council. Hoping to reconcile the West with the East, he offered to recognize Paulinus as Patriarch of Antioch.

Those who had acted against Saint Gregory on behalf of Maximus, particularly Egyptian and Macedonian bishops, arrived late for the Council. They did not want to acknowledge the saint as Patriarch of Constantinople, since he was elected in their absence.

Saint Gregory decided to resign his office for the sake of peace in the Church: “Let me be as the Prophet Jonah! I was responsible for the storm, but I would sacrifice myself for the salvation of the ship. Seize me and throw me... I was not happy when I ascended the throne, and gladly would I descend it.”

After telling the emperor of his desire to quit the capital, Saint Gregory appeared again at the Council to deliver a farewell address (Or. 42) asking to be allowed to depart in peace.

Upon his return to his native region, Saint Gregory turned his attention to the incursion of Appolinarian heretics into the flock of Nazianzus, and he established the pious Eulalius there as bishop, while he himself withdrew into the solitude of Arianzos so dear to his heart. The saint, zealous for the truth of Christ, continued to affirm Orthodoxy through his letters and poems, while remaining in the wilderness. He died on January 25, 389, and is honored with the title “Theologian,” also given to the holy Apostle and Evangelist John.

In his works Saint Gregory, like that other Theologian Saint John, directs everything toward the Pre-eternal Word. Saint John of Damascus (December 4), in the first part of his book An Exact Exposition of the Orthodox Faith, followed the lead of Saint Gregory the Theologian.

Saint Gregory was buried at Nazianzos. In the year 950, his holy relics were transferred to Constantinople into the church of the Holy Apostles. Later on, a portion of his relics was transferred to Rome.

In appearance, the saint was of medium height and somewhat pale. He had thick eyebrows, and a short beard. His contemporaries already called the archpastor a saint. The Orthodox Church, honors Saint Gregory as a second Theologian and insightful writer on the Holy Trinity.

MARTYRS FELICITAS OF ROME AND HER SEVEN SONS (164)

The Holy Martyr Felicitas with her Seven Sons, Januarius, Felix, Philip, Silvanus, Alexander, Vitalius and Marcial. Saint Felicitas was born of a wealthy Roman family. She boldly confessed before the emperor and civil authorities that she was a Christian. The pagan priests said that she was insulting the gods by spreading Christianity. Saint Felicitas and her sons were turned over to the Prefect Publius for torture.

Saint Felicitas witnessed the suffering of her sons, and prayed to God that they would stand firm and enter the heavenly Kingdom before her. All the sons died as martyrs before the eyes of their mother, who was being tortured herself.

Saint Felicitas soon followed her sons in martyrdom for Christ. They suffered at Rome about the year 164. Saint Gregory Dialogus mentions her in his Commentary on the Gospel of Saint Matthew (Mt.12:47).

Source: Orthodox Church in America_ OCA

2 Peter 1:1-10

1 Simon Peter, a bondservant and apostle of Jesus Christ,To those who have obtained like precious faith with us by the righteousness of our God and Savior Jesus Christ: 2 Grace and peace be multiplied to you in the knowledge of God and of Jesus our Lord, 3 as His divine power has given to us all things that pertain to life and godliness, through the knowledge of Him who called us by glory and virtue, 4 by which have been given to us exceedingly great and precious promises, that through these you may be partakers of the divine nature, having escaped the corruption that is in the world through lust. 5 But also for this very reason, giving all diligence, add to your faith virtue, to virtue knowledge, 6 to knowledge self-control, to self-control perseverance, to perseverance godliness, 7 to godliness brotherly kindness, and to brotherly kindness love. 8 For if these things are yours and abound, you will be neither barren nor unfruitful in the knowledge of our Lord Jesus Christ. 9 For he who lacks these things is shortsighted, even to blindness, and has forgotten that he was cleansed from his old sins. 10 Therefore, brethren, be even more diligent to make your call and election sure, for if you do these things you will never stumble;

Mark 13:1-8

1 Then as He went out of the temple, one of His disciples said to Him, "Teacher, see what manner of stones and what buildings are here!" 2 And Jesus answered and said to him, "Do you see these great buildings? Not one stone shall be left upon another, that shall not be thrown down." 3 Now as He sat on the Mount of Olives opposite the temple, Peter, James, John, and Andrew asked Him privately, 4 Tell us, when will these things be? And what will be the sign when all these things will be fulfilled? 5 And Jesus, answering them, began to say: "Take heed that no one deceives you. 6 For many will come in My name, saying, 'I am He,' and will deceive many. 7 But when you hear of wars and rumors of wars, do not be troubled; for such things must happen, but the end is not yet. 8 For nation will rise against nation, and kingdom against kingdom. And there will be earthquakes in various places, and there will be famines and troubles. These are the beginnings of sorrows.

#orthodoxy#orthodoxchristianity#easternorthodoxchurch#originofchristianity#spirituality#holyscriptures#gospel#bible#wisdom#faith#saints

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE DESCRIPTION OF SAINT JOHN HENRY NEWMAN The Patron of the Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham in England and Wales Feast Day: October 9

John Henry Newman, the 19th-century's most important English-speaking Catholic theologian, spent the first half of his life as an Anglican and the second half as a Roman Catholic. He was a priest, popular preacher, writer, and eminent theologian in both churches.

Born in London, England, he studied at Oxford's Trinity College, was a tutor at Oriel College, and for 17 years was vicar of the university church, St. Mary the Virgin. He eventually published eight volumes of Parochial and Plain Sermons as well as two novels. His poem, 'Dream of Gerontius,' was set to music by Sir Edward Elgar.

After 1833, Newman was a prominent member of the Oxford Movement, which emphasized the Church’s debt to the Church Fathers and challenged any tendency to consider truth as completely subjective.

Historical research made Newman suspect that the Roman Catholic Church was in closest continuity with the Church that Jesus established. In 1845, he was received into full communion as a Catholic. Two years later he was ordained a Catholic priest in Rome and joined the Congregation of the Oratory, founded three centuries earlier by Saint Philip Neri. Returning to England, Newman founded Oratory houses in Birmingham and London and for seven years served as rector of the Catholic University of Ireland.

Before Newman, Catholic theology tended to ignore history, preferring instead to draw deductions from first principles—much as plane geometry does. After Newman, the lived experience of believers was recognized as a key part of theological reflection.

Newman eventually wrote 40 books and 21,000 letters that survive. Most famous are his book-length Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, On Consulting the Faithful in Matters of Doctrine, Apologia Pro Vita Sua—his spiritual autobiography up to 1864—and Essay on the Grammar of Assent. He accepted Vatican I's teaching on papal infallibility while noting its limits, which many people who favored that definition were reluctant to do.

When Newman was named a cardinal in 1879, he took as his motto 'Cor ad cor loquitur'—'Heart speaks to heart.'

He was buried in Rednal 11 years later. After his grave was exhumed in 2008, a new tomb was prepared at the Oratory church in Birmingham.

Three years after Newman died, a Newman Club for Catholic students began at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. In time, his name was linked to ministry centers at many public and private colleges and universities in the United States.

In 2010, Pope Benedict XVI beatified Newman in London. Benedict noted Newman's emphasis on the vital place of revealed religion in civilized society, but also praised his pastoral zeal for the sick, the poor, the bereaved, and those in prison. Pope Francis canonized Newman in October 2019.

Source: Franciscan Media

15 notes

·

View notes