#the medieval period as represented in A Knight's Tale

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

we discussed why Ridley Scott's film is unlikely to be the way we would like it to be

so I have a question: what films/series about Napoleon more or less correctly represent real history? or just good in your opinion

oh man, I'm a bit of a picky person when it comes to Napoleonic films/series, but not in a logically consistent manner so people get a little confused sometimes. Which is fair.

I'll give you two rec's:

My favourite Napoleon movie is Monsieur N. I think what makes it work is that it's a historical AU, basically, and fills all my favourite tropes. Premise is that Napoleon, through a weird magic (?) thing, switches fates with his valet/spy Cipriani and manages to escape St. Helena.

As one can guess, it's only loosely, loosely based in history. The ages of some people are altered (Betsy Balcombe is aged up significantly so she can be an appropriate love interest for Napoleon; Barry O'Meara is in his late thirties/early forties for no apparent reason etc.). I feel like Albine got shafted in being cast as a bit of the Conniving Courtesan. Montholon is positioned as a poisoner, even though by the time the film was made that theory/story had been pretty heavily debunked. They omit Napoleon's crap treatment of Fanny Bertrand after she rebuffed his advances. Napoleon's still played too seriously - but that's a fault in literally almost every production ever.

That said, I love Bertrand in this. Gourgaud makes a rogue appearance and is suitably chaotic. I like Sir Hudson Lowe as well - I feel that Richard Grant was cast perfectly. The visuals are beautiful. It's just gorgeously filmed (I love the first confrontation/meet scene between Napoleon and Lowe - the playing with light, the choice of clothes, the switching through languages etc. it's masterful).

The historical inaccuracy aside, I actually liked the relationship between Napoleon and Betsy. I'm just like "clearly it's another Betsy Balcombe. Funny that two people have the same name on this small island!"

(Obviously, in reality, she was a literal child when she knew Napoleon. He was an uncle/older brother figure to her and she was clearly a surrogate daughter/niece to him. They pranked each other and teamed up to prank Lowe on the regular alongside playing silly games and mucking about.)

I love that it's a multi-lingual production so you have English, French and Corsican being spoken, as appropriate for the characters/people. The sound track is fitting. It's appropriately atmospheric.

So yeah, I am very fond of the film. But it's just a fun, stupid romp.

You can't go in expecting a Real Historical And/Or Accurate Account of Napoleon on St. Helena. Thankfully, the film never positions itself as such a thing. It's very clearly a What If + Fanfiction. I recommend going in and treating it like a slightly more serious Knight's Tale in its approach to history (vibes & essence over facts). If you do that, you'll have a blast. If you go in looking for Historical Napoleon or whatever, you'll hate it.

I also may or may not have a Thing for Philippe Torreton (who plays Napoleon). So. That might also inform my affection for this dumb film.

-----

I remember enjoying the 2002 French miniseries Napoleon (with Christian Clavier and Isabella Rossellini). As with all series and films, it has its issues (there are definite inaccuracies), but I liked it overall. I feel they hit the emotional beats between Napoleon and Josephine really well.

(While she's not older than him in it, at least the actors the same age and she's not like 16 years younger than Napoleon /eye roll.)

The scene when she reams him out during their divorce is powerful (she does this great thing about how he always wanted to make it clear that he's separate from the ancien regime and Not Like Those People but what is he doing now? He's marrying one of Marie Antoinette's relatives. And like, she is calling him out for his political inconsistency, and making the point that it's a bad decision in terms of Optics, but it's also so clearly much more than that. It's well done). Napoleon's reaction when he learns that she's died is heart breaking and well rendered/believable.

There is also humour and convivial moments that are often lacking in historical biopics with him, which I appreciate (love the "you need to take the Austrian uniform off the scarecrow or we'll have an International Incident on our hands" scene).

There's a rogue Coulaincourt who makes an appearance! Nice to see him. Same with Lannes - glad he makes an appearance. Though there's no Duroc or Junot, unfortunately. (Granted, I understand the need to keep the cast to a reasonable amount of people.)

So yeah, it's an entertaining series. It's a bit of a "classic" in the sense that I feel like anyone who has gone through a Napoleon Phase watches it.

----

Truly, the best representation of Napoleon is in Bill and Ted's Most Excellent Adventure. You're welcome.

----

I hope this helps!

#thank you for the ask!#napoleon bonaparte#there's the Marlon Brando film that a lot of people like as well#I thought it was fine#Napoleon#that 1970s or 80s Waterloo movie is meh imo#ask#reply#monsieur n#napoleon (2002)#film#I remember being on a date with someone who saw Monsieur N & they kept going on about how they hated it bc they felt it was inaccurate#and I was like: You do realize it's a historical AU that's not meant to be accurate right? It's like complaining about the inaccuracy of#the medieval period as represented in A Knight's Tale#that's what you sound like right now. Like someone complaining about the rendering of Chaucer in the pop culture hit A Knight's Tale#Monsieur N was never meant to be a Serious Film. It's beautifully filmed and a lot of fun but it's not History#napoleon in film

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deep dives into folklore: Arthurian legend

The Arthurian legends are a captivating tapestry of myth, history, and literary invention that have evolved over centuries to become a cornerstone of Western literature and culture. Rooted in Celtic and medieval traditions, these legends center around the legendary King Arthur, his Knights of the Round Table, and the magical world of Camelot. The evolution of Arthurian legends reflects the dynamic interplay between historical events, oral storytelling, and written narratives. This week we long awaitedly explore the multifaceted transformation of Arthurian legends from their origins to their modern interpretations in the first part of this deep dive.

The origins of Arthurian legends are shrouded in mystery, with some historians speculating that they may have been inspired by a historical figure or composite of several leaders from early medieval Britain. The earliest references to Arthur can be traced to Welsh sources such as the "Historia Brittonum" and the "Annales Cambriae," both of which date back to the 9th and 10th centuries. In these texts, Arthur is depicted as a warrior who defended Britain against invading forces.

However, it was Geoffrey of Monmouth's "Historia Regum Britanniae" in the 12th century that provided the Arthurian legend with a significant boost in popularity. Geoffrey's work portrayed Arthur as a legendary king who established a prosperous kingdom in Britain and fought against both Saxon and Roman invaders. This narrative laid the foundation for subsequent Arthurian literature.

The Arthurian legends underwent a remarkable transformation during the High Middle Ages, particularly in the 12th and 13th centuries. This period saw the emergence of Arthurian romances, which focused less on historical accuracy and more on themes of chivalry, courtly love, and quest. One of the most influential authors of this era was Chrétien de Troyes, whose works, including "Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart" and "Perceval, the Story of the Grail," introduced iconic characters like Lancelot and the quest for the Holy Grail.

These romances introduced a new dimension to the legends, emphasizing the moral and ethical aspects of knighthood. The knights of Arthur's court became exemplars of chivalric virtues, setting the standard for medieval conduct. The character of Guinevere and her adulterous affair with Lancelot added complex layers to the stories, exploring the tension between personal desire and societal expectations.

Sir Thomas Malory's "Le Morte d'Arthur," written in the 15th century, is perhaps the most famous compilation of Arthurian stories during this period. Malory's work consolidated various legends and romances into a single narrative, emphasizing the tragic aspects of Arthur's rule and the dissolution of the Round Table.

The Arthurian legends experienced a resurgence in popularity during the Victorian era. Writers such as Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and Sir Walter Scott created their own versions of Arthurian tales, emphasizing themes of national identity, heroism, and the importance of preserving a mythical past. Tennyson's "Idylls of the King" reimagined Arthur as a symbol of Victorian ideals, with his reign representing an idyllic and noble past.

The 20th and 21st centuries have witnessed a continued fascination with Arthurian legends, with numerous adaptations in literature, film, and television. T.H. White's "The Once and Future King" (1958) is a notable modern retelling of the Arthurian saga, exploring themes of leadership, war, and the human condition.

Arthurian legends have also been featured in popular films like John Boorman's "Excalibur" (1981) and in television series like "Merlin" (2008-2012) and "Camelot" (2011). These adaptations often reinterpret the legends to suit contemporary audiences, blending elements of fantasy, romance, and adventure.

The evolution of Arthurian legends is a testament to their enduring appeal and adaptability. From their obscure origins in ancient Celtic and Welsh folklore to their transformation into tales of chivalry and romance during the Middle Ages, and their revival and reinterpretation in the modern era, these legends have continually captured the imagination of generations. The Arthurian legends remain a rich source of inspiration, reflecting the ever-changing values and concerns of the societies that have embraced them. Whether viewed as historical accounts or imaginative fables, the legends of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table continue to hold a special place in the literary and cultural heritage of the Western world. Next week I will be talking about the real life mark that arthurian legends had on britain, more specifically wales.

Taglist (reply or reblog to be added):

@axl-ul @crow-flower @thoughts-fromthevoid @alderwoodbooks @harleyacoincidence @tuberosumtater @sonic-spade @theonlygardenia @holymzogynybatman @nulliel-tres

#writeblr#writers of tumblr#bookish#writing#booklr#fantasy books#creative writing#book blog#ya fantasy books#ya books#folklore#deep dives into folklore#books#literature#merlin#king arthur#bbc merlin#merlin bbc#merlin emrys#arthur pendragon#guinevere#morgana pendragon#gaius

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unveiling the Timeless Masterpiece: The Canterbury Tales - A Window into Medieval Life

The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer is one of the greatest literary works of the Middle Ages and is considered a masterpiece of English literature. Written in the late 14th century, this enlightening work of fiction provides readers with a unique window into life during Medieval England. This collection of 24 stories is written in verse and is set in the context of a pilgrimage to Canterbury. The stories are told by a group of travelers, who are on their way to visit the shrine of Saint Thomas Becket in Canterbury. We will now explore the historical context of The Canterbury Tales, delve into some of the most famous tales, and the impact that the work has had on literature and culture. So, come join us on this journey as we explore the Canterbury Tales.

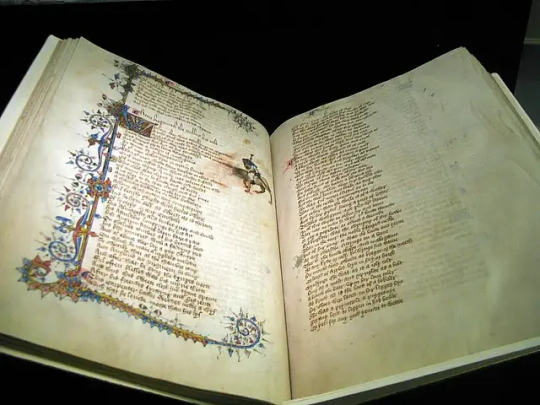

Canterbury tales volume set and Jeffery Chaucer. Photo by the British Library. THX News.

Context of Medieval England

Political Context Medieval England was characterized by a feudal system where the king held supreme power and granted land to nobles in return for their loyalty and military service. The peasantry, which comprised the majority of the population, worked on the lands of the nobles in exchange for protection and a share of the produce. The political instability of the period, due to frequent wars and disputes over the throne, led to growing dissatisfaction among the common people. The Canterbury Tales reflect this political context in several ways. The tale of the Knight, who is an embodiment of chivalry and loyalty, represents the idealized image of the nobles. The Pardoner, on the other hand, who cheats people for money, is a critique of the corrupt practices of the Church and State officials. Social Context The rigid social stratification of the Medieval period placed the aristocracy at the top and the peasantry at the bottom of the social ladder. Medieval society was patriarchal, and women had limited opportunities for education and employment. The Church played a significant role in the social structure and exerted its influence over all aspects of life, including education, law, and morality. Chaucer’s work reflects this social context in significant ways. The Miller and the Reeve, who are portrayed as buffoons, represent the lower classes, and their crude behavior contrasted with the refined and cultured qualities of the Monk and the Nun’s Priest. Religious Context Religion played a crucial role in the medieval society of England. The Church was viewed as the moral authority and was responsible for providing spiritual guidance to the people. Religious festivals, pilgrimages, and prayer were an integral part of everyday life. Christianity was the dominant religion, and other faiths were not tolerated. The Canterbury Tales reflects this religious context through the character of the Parson, who embodies the virtues of Christianity and represents the ideal spiritual guide. At the same time, the Friar and the Pardoner, who were both connected with the Church, are depicted as greedy and corrupt individuals who exploit the faith of the people for their own benefit.

A highlight of Decorated Gothic art the outer north porch c.1325 of St Mary Redcliffe, Bristol, England. Photo by Spencer Means. Flickr.

Overview of The Canterbury Tales

Historical Background The Canterbury Tales was written in a time that saw a significant transformation of English literature. In the late 14th century, English replaced Latin and French as the main language of literature. It was due in part to the efforts of writers like Chaucer, who sought to make literature accessible to all, regardless of their social status and education. Chaucer’s work marked the emergence of English as a literary language, which further contributed to the English language’s development. Themes and Style The Canterbury Tales is a complex work that incorporates various themes. The tales told by the characters bring out fundamental human endeavors, such as love, greed, and power. Chaucer’s views on social hierarchy and morality also permeate the tales. Humor and satire are other striking elements of the work, which add to its appeal. Each character’s tale is narrated in a distinct style that reinforces their characterization, making The Canterbury Tales a prime example of the art of characterization in literature. The Structure of The Canterbury Tales The structure of The Canterbury Tales is crucial to its style and thematic content. The work comprises 24 stories in total, broken down into tales told by twenty-three pilgrims, along with two tales told by the host. The pilgrims are representative of various sections of medieval society, from the high-ranking aristocrats to the working-class characters like the plowman and the miller. This range of characters and their tales effectively portrays medieval English society.

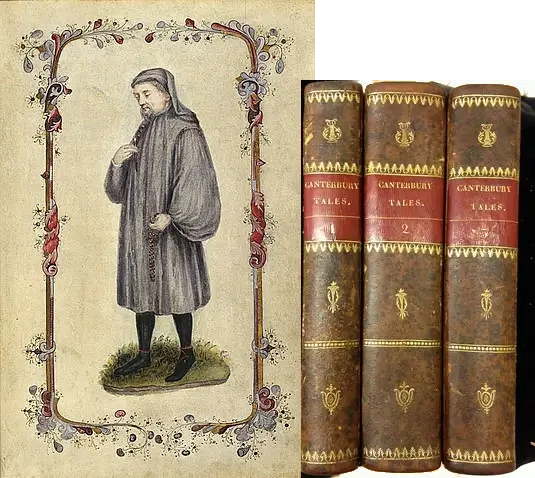

The Knight of The Knight's Tale. Photo by Ben Sutherland. Flickr.

Characters

The Knight The first character that comes to mind is the Knight, who is the epitome of chivalry and honor. He is described as "a worthy man" and has fought in many battles over the course of his life. His tunic bears the emblem of St. George, suggesting that he is a devout Christian. The Knight's tale is one of adventure and romance, and it explores the themes of love and loyalty. The significance of the Knight's character lies in his representation of the ideal of chivalry, which was highly valued during the Middle Ages. The Wife of Bath Another memorable character is the Wife of Bath, who is a self-proclaimed expert on marriage and love. She has been married five times and is not ashamed of it. In fact, she sees marriage as a means of achieving control over men. The Wife of Bath's tale is a feminist retelling of the story of King Arthur and his queen, and it explores the themes of power and gender roles. The significance of the Wife of Bath's character lies in her representation of unorthodox views on marriage and women's rights, which were radical in the Middle Ages. The Miller The Miller is another colorful character in The Canterbury Tales. He is a rude and vulgar man, who enjoys drinking and stealing. He is described as having a "red beard" and a "wide nostril" and is always ready to pick a fight. The Miller's tale is a bawdy one, which involves a love triangle and a lot of sexual innuendo. The significance of the Miller's character lies in his representation of the lower classes, who were often overlooked in Middle English literature. The Pardoner The Pardoner is a fascinating character, who is both repulsive and alluring. He is a religious figure who sells indulgences, which are supposed to reduce the time spent in purgatory. However, the Pardoner is a fraud, and he often makes up stories to convince people to buy his wares. He is described as having "hair as yellow as wax" and a "smooth, hairless face." The Pardoner's tale is a moral one, which explores the themes of greed and corruption. The significance of the Pardoner's character lies in his representation of the corruption within the Church. The Summoner The final memorable character we will discuss is the Summoner, who is a repulsive and grotesque figure. He is a religious official whose job is to summon sinners to appear before the Church courts. However, he is corrupt and often accepts bribes to let people off the hook. He is described as having a "fierce red face" and a "face full of pimples." The Summoner's tale is a scathing critique of the corruption within the Church, and it explores the themes of hypocrisy and greed. The significance of the Summoner's character lies in his representation of the corruption and moral decay within the Church.

The Two Noble Kinsmen, Palamon and Arcite. Photo by Ben P L from Provo, USA. Wikimedia.

Themes

Social Hierarchy Social hierarchy was a prominent aspect of medieval society. As a result, Chaucer subtly incorporated it into his writing. In the story, The Knight's Tale, the character of Theseus is used to provide us with a glimpse into medieval royalty. He is portrayed as a respected and noble leader that people look up to. His social status gives him power, but also adds a weight of responsibility to his actions. The Boy's Tale is another story that presents us with the importance of social position. This tale focuses on the story of two friends, Arcite and Palamon. The two men are both in love with Emelye, but because Arcite is of nobler birth, his aspirations to marry her are more likely to be approved. The story shows how social status played a role in love and marriage during medieval times. Morality Morality plays a central role in many of the tales in the Canterbury Tales. Chaucer is seen as a master of his craft, capable of dealing with complex moral conundrums in a way that is relatable to readers. In The Pardoner's Tale, we see how greed can drive men to do terrible things. The tale exposes the corrupt nature of humans, who are always tempted by material things. The Wife of Bath's Tale teaches us about the importance of trust and compromise in relationships. She emphasizes how important it is to listen to each other's needs and desires. The tale also portrays a woman who has control over her own life. This was a revolutionary notion during the medieval era, when society was deeply patriarchal. Religion Religion is prevalent throughout the Canterbury Tales. People during the medieval era were devout believers and religion played a central role in everyday life. In The Man of Law's Tale, we see the story of a converted Jew who converts to Christianity. The story shows how religion can change a person's life and beliefs. The Friar's Tale, on the other hand, focuses on the immoral nature of some religious figures. The friar is portrayed as a corrupt individual who uses his position in the church for personal gain. This tale teaches us about the dangers of trusting those who claim to be religious simply because of their position.

Structure

The Canterbury Tales is a frame narrative, with the frame being the pilgrimage to Canterbury. The narrative framework of the tales is a crucial element as it sets the stage for the stories and binds them together. The pilgrims represent all sections of medieval society, from the nobility and the religious to the commoner, making it a unique representation of contemporary medieval life. The structure of the pilgrimage narrative is partly designed to encourage us as readers not merely to observantly read, but to actively participate in the journey. The stories in The Canterbury Tales have multiple levels of meaning, serving as both entertainment and social critique. The tales range from the high-minded Knight's Tale, which deals with questions of honor, courage, and justice, to the bawdy Miller's Tale, which serves as a very down-to-earth contrast. As the tales come to us, we are passive listeners who are participants in the journey, and the storytellers invite us to join the discussion. The tales also reveal a great deal about the people who are telling them, providing rich character studies. For instance, the character of the Wife of Bath is revealed in her story as she justifies her lustful tendencies. Classic Story Telling The story-telling structure is also a characteristic feature of the book's structure. The tale-tellers are introduced in the General Prologue, which provides a brief profile of each pilgrim. As the journey continues, each pilgrim tells one tale, resulting in 24 tales. However, it is the tale-telling structure that makes this book one of the most significant literary works of all time. The structure of the tales is both entertaining and educational, capturing the essence of medieval life. The tales in The Canterbury Tales exemplify the medieval genre of fabliaux, which means "little stories" in old French. Each story is a self-contained narrative, and the tales vary in length and complexity. Some reflect the traditions of romantic courtly love, while others satirize religious and secular institutions. The tales are all very different, and their distinctive storytelling style. The tales reveal the conditions of various medieval groups and offer insights into medieval ethics, morals, and religion. The variety of stories is a reflection of the wide diversity of society, which is a crucial feature of the overall narrative.

FLINT, William Russell 1880-1969. Chaucer's 'The Canterbury Tales', Frontispiece, 1928.. Photo by Halloween HJB. Flickr.

Significance to Literature and History

First and foremost, The Canterbury Tales is considered significant because it is considered a seminal work in the development of English literature. It was written in Middle English, which was the language spoken in England during the 14th century. The stories reflect the cultural and social norms of the time, allowing readers to get a glimpse into medieval life. This historic context provides a unique and insightful interpretation of one of the most significant pieces of English literature. Moreover, The Canterbury Tales is also considered significant for the way it challenges societal norms and the status quo. Chaucer’s works were known for being ‘bawdy’ and controversial. The Canterbury Tales, in particular, features characters who challenge societal norms, such as the Wife of Bath, who was seen as a feminist figure. The words and actions of the various characters in the stories also reflected a range of personalities and themes, providing a more nuanced interpretation of the medieval period. The English Religious and Socio-political Views of the Time The Canterbury Tales were also a reflection of the religious and socio-political situation of England. During the 14th century, English society was undergoing a period of transformation. England was transitioning from a feudal society to a more centralized government. The book includes a commentary on the corruption within the clergy and the institutionalized practices of the church. Chaucer uses his fictional stories to provide social commentary on the injustices of his time, and this provides a unique perspective on a tumultuous period in English history. The Canterbury Tales is a treasure trove of historical information that can be studied and dissected for years to come. The tales provide ample insight into the cultural, religious, social, and economic aspects of medieval life. The figures in the book reflect the interests, conflicts, and priorities of the medieval people, and understanding these figures provides insight into the complex lives of those who lived in these times.

Conclusion

The Canterbury Tales is a timeless classic that has endured for centuries and continues to influence literature, art, culture, and history. It serves as an important reminder of the values of Medieval England while also providing readers with insight into human nature. Through its tales of chivalry and romance, The Canterbury Tales offers us a glimpse into the lives of characters from all walks of life during this period in time. Those who read it come away with a better understanding of how society was structured during medieval times as well as what people valued most then. Whether you are looking for historical context or just want to get lost in some captivating stories, The Canterbury Tales will not disappoint! Sources: THX News & British Library. Read the full article

#CanterburyTales#Chaucer'scharacters#Englishliterature#Historicalcontext#MedievalEngland#Religioninmedievalsociety#Significancetoliteratureandhistory#Socialcritique#Socialhierarchy#Storytellingstructure

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Art Theory and Criticism - Journal reflection 11

The origins and analysis of Romanticism

When analysing a specific movement and period, one must understand what influenced the artists of the movement from their previous masters of the time and style that came before them. Whether the new style was developed to reject a previous ideology, thus becoming a consequence of the era that came before or was simply adopted based on new discoveries and observations, it is certainly evident that the history of art evolves but always with references. A movement that has a deep history and origin is the Romanticism period. Aside from the movement spreading across all of Europe and later the United States, it did not only involve the visual arts, but also music, literature and even branches of philosophy (Wilder, 2021.)

The origins of the Romanticism movement boil down to the word ‘romantic’ varying from definitions of describing several intermingling languages spoken around Rome during the Classical period along with the associated fantastical stories of knights saving the damsel in distress princess from the dragon (Alliterative, 2016.) further analysing the origins of the Romantic period came the inspiration from the Grimm brothers gathering various German folk tales and huge Gothic architecture with pointed arches directing the eye up to the sky which indicated the heavens.

Figure 1: The Kiss, Francesco Hayez, c. 1859.

According to Alliterative (2016) inspiration from Edmund Burke’s 18th century treatise on aesthetics concerning Sublime represented in the visual arts and landscape painting, made for a breakthrough in rejecting the neo-classical period that came before Romanticism. This rejection stems from the Neo-classical period embracing logic and rationality, which the Romantics replaced with passion, expression, and the individual’s moral qualities. This sparked further reference to the sublime, fairy-tale folklore and fantastical elements of medieval stories that was present in the previous centuries.

Figure 2: John Constable, Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows, exhibited 1831.

However, this knowledge came only to the privileged, as only the wealthy could realistically have time to think about these things and fantasise about them, while also delving into the literature, music and visual arts that broadened their horizons on the matter. Which is why it is very ironic that this class of people would sympathise with these famous stories of the period like Victor Hugo’s ‘The Hunchback of Notre Dame’, ‘Les Misérables’, and Mary Shelly’s ‘Frankenstein, as stated by Wilder (2021):

All three works are outcries against man's inhumanity to man. To drive home the point, the writers magnify the inhumanity so we can see it better. They do this by directing it against outcasts: a hunchback, an ex-convict, and a manmade monster. The more of an outsider someone is, the more people abuse that person.

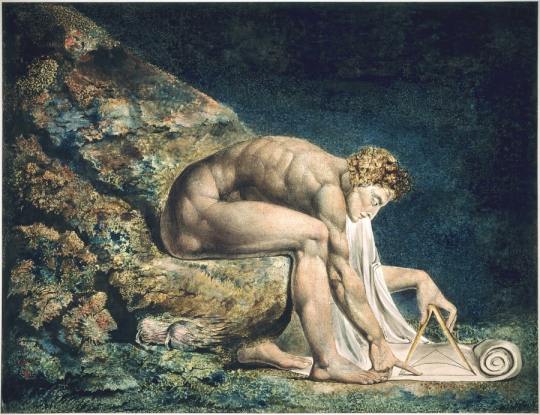

Figure 3: Newton, William Blake, c. 1804-1805.

Figure 4: Liberty Leading the People, Eugène Delacroix, c. 1830.

Figure 5: John William Waterhouse, The Lady of Shalott, 1888.

Overall, it was a positive movement that gave hope to its followers by encouraging the belief of one’s morals and the goodness of man that can be hidden under trauma, rejection, and disastrous events. Many of the revolutions and political crises that dragged along in struggle for decades was still fresh in these people’s minds. They wanted to enjoy the bright side of life along with appreciating nature’s sublime quality that reminded them of man’s insignificance of his fruitless struggles in war. In a way, this was their escapism from the darker times that still haunted them, along with humanity's dark side that creeps out in due time.

Reference list:

Alliterative, 2016. Sublime: The Aesthetics & Origins of Romanticism. YouTube. Available at: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=au-z2jVaTNk> [Accessed 7 January 2024].

Wilder, J.B., 2021. Defining Romanticism in the Arts. [online] dummies. Available at: <https://www.dummies.com/article/academics-the-arts/art-architecture/art-history/defining-romanticism-in-the-arts-200515/> [Accessed 7 January 2024].

1 note

·

View note

Text

Sorry for the extreme rambling, but this is something I also noticed upon my first reading of The Consequence of Audience.

This is an amazing close-reading from @vqtkufi

As a uni student of Theology & Literature, I remember writing my term paper for a poetry class a few semesters ago about this very topic. The way that epics (Gilgamesh, Odyssey, Illiad) of classical antiquity begin is always in the midst of action: Aneas carrying Anchises over his shoulder, fleeing from burning Troy. The homoerotic wrestling match between Gilgamesh & Ekidu.

These epic tales were written by victors for victors ABOUT victors. So as we move from Ancient Greece to the early modern period with Dante, it matters that he starts the Inferno with the protagonist waking up & finding himself in “a dark wood” (i.e. The Great Dark)

ALSO ALSO ALSO, let it matter that before Dante, the writers of those aforementioned ancient epics had no imperative to place themselves in their tales of triumph & catharsis. It simply wasn’t done. But Dante gives us something new! Dante self-inserts into the narrative because he wants readers of his time to see themselves in the Everyman representing humanity as a whole rather than an individualist hero or a larger-than-life divine being because what’s real to Dante as a Catholic & a politician isn’t that anyone can go from zero to hero——more so, that we are a foul brood of violence & sin & all equally find ourselves traversing these “great dark” woods.

It’s funny that that’s the case because those authors of the Greek epics (Virgil, Aeschylus, Homer) are also characters within Dante’s venture & the “dark wood” likely a product of the poet’s imagination recollecting the Greeks’ ideas. These include the medieval Platonic image of chaotic matter——unformed, unnamed——as a type of primordial wood (silva); the forest at the entrance to the classical underworld (Hades) as described by Virgil; Augustine's association of spiritual error (sin) with a "region of unlikeness"; the dangerous forests from which the wandering knights of medieval Romances must extricate themselves. In an earlier work (Convivio) Dante imagines the bewildering period of adolescence--in which one needs guidance to keep from losing the "good way"--as a sort of "meandering forest”

Dante, I believe, was very familiar with the concept of “the great dark” as unraveled by Hayden. Im sure Dante would also be pleased to learn that we are calling it “the Great Dark” he would love that ♡

Dante definitely lived most of his adult life in Apathy…

I can't help but find the beginning of 'Dante's Inferno' and 'The Consequence of Audience' to be quite strikingly similar. Both beginning in what seems to be a somewhat dull overgrown woodland/tunnel of trees. Dante is described to be astray from the path. Likewise, The protagonist in Hayden's text seems to be somewhat separated from The Great Dark, before being ‘thrust upon the rocky expanse’. Both texts begin with the subject being adrift or detached in some sense. I may very well be misunderstanding a lot of details so forgive me lmao

@mothercain

I have no clue if this was intentional or I am in fact a little deranged.

(forgive my rambling, its late and I cant sleep...)

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Middle ages' literature, well, a bit about it

Question: Ever wondered about the captivating tales that unfolded during the Middle Ages, shaping our understanding of language, storytelling, and the human experience? Join me as we unravel the tapestry of medieval literature, a period spanning from the fall of the Western Roman Empire in AD 500 to the dawn of the Renaissance. Let's explore the works of literary giants like Dante Alighieri, Geoffrey Chaucer, and the anonymous author of Beowulf, and uncover the rich cultural legacy that continues to resonate in our modern world.

I. Key Contributors to Medieval Literature

Dante Alighieri and "The Divine Comedy": Dante's epic poem, "The Divine Comedy," takes readers on a profound journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven. Its allegorical nature explores themes of sin, redemption, and the divine, making it a masterpiece of world literature.

Geoffrey Chaucer and "The Canterbury Tales": Chaucer's collection of stories, "The Canterbury Tales," offers a vivid portrayal of 14th-century English society. The diverse narratives showcase the multifaceted nature of medieval life, from bawdy comedies to moral fables.

Anonymous Author of Beowulf: The Old English epic poem "Beowulf" narrates the heroic deeds of Beowulf as he confronts monstrous foes, emphasizing the struggle between good and evil and the significance of honor and heroism.

Thomas Malory and "Le Morte d'Arthur": Malory's compilation of Arthurian legends has left an indelible mark on English literature, captivating readers with tales of King Arthur, his knights, and the quest for the Holy Grail.

Christine de Pizan: Christine de Pizan, a notable medieval writer, significantly contributed to literature with her influential prose works, offering insights into the social and intellectual milieu of the time.

Julian of Norwich: As a Christian mystic, Julian penned the first book written in English by a woman, "Revelations of Divine Love," providing spiritual insights and a unique contribution to medieval literature.

Margery Kempe: Kempe's autobiographical work, considered the first example of autobiography in English, offers a rare glimpse into medieval life from a woman's perspective, contributing to the understanding of personal narratives.

II. Key Works of Medieval Literature

"The Divine Comedy" by Dante Alighieri: Dante's journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven explores profound themes, influencing subsequent literary and artistic traditions.

"The Canterbury Tales" by Geoffrey Chaucer: Chaucer's tales, representing a cross-section of medieval society, provide a vibrant snapshot of life in 14th-century England, showcasing diverse storytelling styles.

"Beowulf" (Author Unknown): An essential work of Old English literature, "Beowulf" explores heroic deeds, loyalty, and the inevitability of fate, shaping the foundation of medieval storytelling.

"Le Morte d'Arthur" by Thomas Malory: Malory's work weaves the tales of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, contributing to the enduring legacy of Arthurian literature.

III. Key Aspects and Elements of Medieval Literature

Religious Writings: Christianity heavily influenced medieval literature, giving rise to religious writings that encompassed saints' lives, sermons, and devotional poetry.

Secular Works: Alongside religious writings, secular works in various genres, such as epics and romances, flourished, offering diverse perspectives on life, love, and morality.

Vernacular Literature: The shift from Latin to vernacular languages democratized literature, making it more accessible to a broader audience.

Epic and Romance: Epic poetry and romance literature, typified by heroic deeds and tales of chivalry, played a crucial role in shaping the medieval literary landscape.

Allegory and Symbolism: Many medieval works were characterized by allegory and symbolism, with authors using symbolic elements to convey deeper moral or religious meanings.

Diverse Genres: Medieval literature embraced a multitude of genres, reflecting the complexity and richness of the literary traditions during this period.

Influence of Classical and Christian Thought: The synthesis of classical and Christian thought formed the basis of medieval interpretation, shaping the symbolic understanding of life and literature.

IV. Distinctive Features of Medieval Literature

Chivalry, Courtly Love, and Pursuit of Honor: Medieval literature often celebrated the ideals of chivalry, courtly love, and the pursuit of honor, exemplified in tales of knights and noblewomen.

Allegory and Religious Themes: Allegory and religious themes permeated medieval literature, with authors conveying moral and spiritual messages through symbolic narratives.

Epic and Heroic Elements: Medieval literature, particularly in epic poems, highlighted heroic elements and explored the struggle between good and evil.

Vernacular Literature: The rise of vernacular literature democratized access to literary works, fostering a more inclusive literary culture.

Impersonality/Anonymity and Derivative Stories: Middle English literature often featured impersonal or anonymous authorship, reflecting the oral tradition and the influence of earlier works.

Religiosity and Oral Quality: The religiosity of medieval literature, combined with an oral quality, underscores the cultural and spiritual influences that shaped literary expression.

V. Influence of Medieval Literature on Society

Modern Imagination: The Middle Ages continue to inspire modern imagination, evident in various art forms, literature, photography, film, immersive reenactments, and video games.

Language and Storytelling: Medieval literature's diverse styles, languages, and themes have left an enduring mark on modern storytelling, influencing language development and narrative techniques.

Religion and History: Medieval literature serves as a vital source for understanding religious beliefs and historical contexts, providing insights into universal human experiences.

Development of Secular Works: The printing press played a pivotal role in making literature more accessible, fostering the development of secular works during the Renaissance.

Imagination: Medieval literature, with its remarkable individuals and intellectual history, continues to inspire and provoke the imagination, contributing to the richness of human creativity.

Conclusion: As we conclude our exploration of medieval literature, we marvel at the enduring impact of the works crafted during this transformative period. From the divine realms of Dante's "The Divine Comedy" to the earthly tales of Chaucer's pilgrims, medieval literature has bequeathed us a cultural legacy that transcends time. Its influence on language, storytelling, religion, and history is palpable in our modern society, serving as a testament to the profound and timeless power of the written word. In the intricate tapestry of medieval literature, we find not only stories of knights and epic quests but also a reflection of the human condition—a mirror through which we glimpse our shared past and the boundless possibilities of the imagination.

0 notes

Text

I was thinking about why the inaccuracies in Bridgerton and A Knight’s Tale don’t aggravate me in how they try to be modern. And I think it’s because of a couple of reasons.

One, they aren’t lazy in modernising. They don’t use a basic period template, strip it off everything interesting or old fashioned, wipe it clear of detail and throw in some ‘relatable’ modern stuff instead. The aesthetics are thought out and carried through and make a cohesive world. Not accurate, but immersive and believable.

Second, its because they’ve incorporated elements of modern life that echo realities in the past.

Bridgerton doesn’t have accurate hats and bonnets. It has a regency twist on fascinators. Fascinators are generally associated with fancy events and British upper classes, which is appropriate for the world of Bridgerton, which takes place among the aristocracy during the social season. Using the imagery of modern upper classes to help capture the spirit of the Regency aristocracy, showing that even though this piece is set in the past the underlying drive to fit into this world and advance your family and the class consciousness is still pervasive today,. And while some of the colours, materials and fabrics are not accurate, their intricacy, their obvious expense, is fitting for characters on parade. The clothes are allowed to matter to the characters and make sense for the world they live in.

Furthermore, even though the clothes aren’t accurate, they show signs of research. The dropping off the hems, Eloise’s ribbons, the Queen’s fashions being behind the times, the lighter colours for unmarried girls and the darker tones of the married ladies, all show signs of research. And then the designers take these historical elements, and have fun with them. And instead of toning down interesting historical detail to make the fashions ‘relatable’, they turn the colours and excess right up to make it fun. As a history fan, you can look at the costumes and recognise the influence of regency fashions, even if they aren’t recreated to life. Bridgerton designs are almost a homage, respectful and inspired by regency fashions, as opposed to an attempt to scrub them clean and make them palatable for modern audiences,

A Knight’s Tale recreates the modern sporting world in Medieval Europe, which captures the excitement and thrill of jousting. It merges modern and historical showing how the emotions and passion of competitive sport, the dreams these sports represent, are a constant part of the human experience.

So these works are basically not saying, we want to make a period piece but old fashioned stuff is boring so we’re just going to modernise it. They’re saying that the themes and experiences and; most of all, the people in these works are at heart the same as they were in the past as they are in modern day, so we will blend these worlds together to make a new world to show the timelessness of these themes.

75 notes

·

View notes

Photo

It simply isn't an adventure worth telling if there aren't any dragons.

- J.R.R. Tolkien

Not until the fall of the Roman Empire and the Rise of Christendom does the dragon in western civilization begin to take on the familiar form we know today in bestiaries and myths. It is perhaps the story of Adam and Eve in the old testament and the appearance of Satan in the form of a serpent that first transfixes the medieval imagination. For nearly a thousand years, the dragon represents evil and becomes synonymous with demons. The dragon is also used by medieval knights emblazoned on their shields and standards to strike fear into the hearts of their enemies. Throughout the epics and romantic stories of this period dragons show up to be slain by the virtuous heroes of folklore, legend and religion.

In the epic of Beowulf (ca. 1000 AD.) the great Scandinavian king slays a monstrous fire-breathing dragon and dies in its arms.

Icelandic tales in the Volsungasaga (1250 AD.) transforms the dwarf prince Fafnir into a dragon to be slain by Seigfried.

The Welsh Epic of The Mabinogion (1400 AD.) depicts the great Red Dragon of Wales battling a White Dragon and causing earthquakes.

In the Christian faith Satan routinely appears a dragon to tempt the saints. The Golden Legend (1200 AD.) illustrates St. George and St. Margaret as well as several other saints, confronted by dragons.

By 1500 ad. the mystical apex of catholicism combined with the ever-increasing craft of the visual artists finds the archetypal fire-breathing dragon in its full splendor. This is well documented when Edmund Spenser describes his titanic monster in The Fairie Queene (1590)

After the Protestant Reformation and the advent of the Age of Reason the dragon becomes more a creature of entertainment rather than of spiritual belief. Protestant artists are prohibited from depicting scenes from the bible and the stories of the saints are abandoned as idolatry. Dragons and other beasts take on a decorative nature, and as subjects of classical illustration. During this period it is the first evidence that the dragon is being treated as a fantasy creature.

The 19th century sees a resurgence in the dragon as archeologists, historians and the stories of the “Pre Raphaelite” age are studied and adopted as acceptable subject matter, through Bullfinch, The Brother’s Grim and new translations of the classics and folklore. Throughout this period the dragon stories of the dark past are fodder for artists and writers alike. By the second half of the nineteenth century the neo-isms (Neoclassical, neo-gothic, neo-egyptian, neo-romanesque) of the beaux-arts academic style return to using the dragon as a decorative embellishment.

With the dawn of the Industrial Age twentieth century science and technology usurps romantic notions of the arts, pushing the stories of dragons into the genre of mythology and the realm of children’s stories. Painting and literature had embraced Realism and analytical minimalism throwing off all superstitions of the past to try to make a New kind of art. Any depiction’s of dragons during this period (and there are few) become an outward representation of the artist’s inner psyche. Psychology has replaced the dragon with the Id and the Ego.

By the 1970’s, however the art world was ready to once again re-embrace spirituality, mythology and the dragon. Post-Modern artists found the writings of J.R.R. Tolkein and Joseph Campbell. The mythologies they had drawn from had a renaissance.

In 1976 TSR introduced Dungeons and Dragons to a world hungry for fantasy and monsters, becoming a popular phenomenon. McCaffery’s Dragonriders of Pern 1970, Dragonslayer 1981 were all introduced to a mesmerized audience. Since then the dragon has entered into the popular consciousness in a way not seen since the Middle Ages. Everything from Harry Potter to World of Warcraft and Skyrim have adopted the dragon as their go-to monster to inspire awe and magic.

What is it about the dragon that has captivated us for all of civilization? Is it the sheer power of nature that cannot be tamed. Is it a psychological metaphor for primal fear? Is it perhaps a innate memory of our long lost primitive prehistory? Whatever the reason, in all cultures around the world the dragon , in all its forms has haunted our minds and our imaginations and will continue to do so in the century to come.

**Medieval artwork of a leaf from Harley’s Bestiary, made from Gerald of Wales’ topography in around 1250–1350AD.

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

“During the years of Eleanor of Aquitaine’s captivity, 1174–89, she disappears almost entirely from sight. According to one account, Henry II ordered her confined in “well guarded strong places”; and she was first housed under close supervision in the royal castle at Sarum, or Old Salisbury, although later she can be located occasionally at other royal castles in southern England. As a woman, Eleanor received more lenient treatment than men captured while taking part in an armed rebellion; and Henry may have chosen Salisbury Castle for her detention as a gesture of leniency, for its residential quarters, a large quadrangle next to the keep, had been one of her favored abodes during her earlier years as queen.

According to a chronicler at Limoges, Henry imprisoned his queen at Salisbury Castle, “on guard against her reverting to her machinations.” The king’s fear was Eleanor’s continued involvement in the intrigues of their quarrelsome sons, and he tried to ensure that no communication passed between them. Yet he could not afford to treat her too harshly, for that would only have added to the hatred that Young Henry, Richard, and Geoffrey already felt for him. Earlier, both Anglo-Norman monarchs and counts of Anjou had not hesitated to imprison defeated nobles, including near-relatives, for years, often under such harsh conditions that they lost their health, if not their lives.

A queen’s long captivity was startling, but imprisonment of great ladies was not unprecedented. In medieval vernacular literature, tales were not uncommon of aristocratic ladies locked away for years, many of them by their own families, and history records many noble maidens whose fathers were forced to turn them over to their lords as hostages. Henry II could have made other choices for ridding himself of the threat presented by Eleanor to the stability of his rule. She could simply have disappeared during her captivity at Chinon, but young Arthur of Brittany’s mysterious disappearance from Rouen Castle later during John’s reign shows that such a solution would have created more problems than it solved.

Rumors that John had murdered his nephew with his own hands quickly spread, and it sapped his subjects’ loyalty to him, crippling him in his contest with his archenemy Philip of France. Certainly rumors of Eleanor’s death while in Henry’s hands following his suspected role in the murder of Becket would have had a similar effect. His wife’s murder would have aroused revulsion throughout Europe, and it would have so enraged the Poitevins that Plantagenet rule over them would have been impossible. In any case, Henry’s character had little in common with that of the insecure and overly suspicious John, and although severe and vengeful, he lacked his youngest son’s depraved cruelty that surfaced once he was king.

An option that great men had often chosen in earlier centuries for dealing with wayward or unwanted wives was immuring them in convents. Henry II considered such a step in 1175–76, when his adulterous affair with Rosamund Clifford was at its most passionate stage. A contemporary writer claimed that Henry, having imprisoned his queen, no longer tried to hide his adultery, and publicly displayed as his mistress, “not a rose of the world (mundi rosa) . . . , but more truly might be called the rose of an impure husband (immundi rosa).”

Apparently Henry was not worried that dissolution of his marriage to Eleanor would threaten his authority over her duchy of Aquitaine. Despite Louis VII’s loss of Aquitaine as a result of his divorce, Henry seemed confident that Richard’s formal installation as duke of Aquitaine and count of Poitou would keep Eleanor’s lands safely in Plantagenet hands. Henry saw an opportunity to secure a divorce from Eleanor at the time of a mission to England by a papal legate, sent from Rome to settle one of the endless quarrels between the kingdom’s two archbishops. On the papal representative’s arrival in England in autumn 1175, the king received him with honor, showering him with gifts and flattery.

Henry assumed that the cardinal would agree readily to a dissolution of his marriage on grounds of consanguinity, since Louis VII had won a divorce for that reason, and Henry’s kinship to Eleanor was even closer than her relationship to her first husband. The English king allegedly offered his queen release from her captivity during his Easter court at Winchester in 1176, if she would agree to enter a religious house, no doubt Fontevraud Abbey, probably with the prospect of becoming abbess there. The abbey had a reputation as a residence for noble ladies seeking refuge from wordly affairs, but Eleanor was unwilling to join them, not even if installed as abbess, and she and her sons resisted Henry’s plan.

She even appealed to the archbishop of Rouen against being packed off to Fontevraud, and he refused to give his consent to Henry’s plan. As the archbishop of Rouen’s role shows, the Church’s opposition was another obstacle to Henry in ridding himself of Eleanor, and his projected divorce was not to be easily accomplished. After Becket’s martyrdom, the English king had little credit with the papacy or with churchmen in England or elsewhere in Europe. He was in no position to pressure a pope firmly opposed to approving a divorce, particularly one who was doubtless aware of rumors that he desired the divorce in order to marry his mistress.

Whatever the possibility of Henry II setting his queen aside and taking Rosamund Clifford as his wife, events intervened to prevent it, for his beloved mistress died late in 1176 or in 1177. His fair Rosamund was buried at Godstow Priory in Oxfordshire only a few miles from their trysting place at Woodstock. Around the time of Rosamund’s death the patron of Godstow, an Oxfordshire baron, assigned his patronage rights over the house to Henry in order that it should be held “in chief of the king’s crown, as the Abbey of Saint Edmund and other royal abbeys throughout the kingdom of England are constituted.” This elevation in Godstow’s status reflects Henry’s deep feelings for his mistress, a desire to honor the convent that housed her tomb and to place the nuns watching over it under royal protection.

In the years following Rosamund’s death, Henry showed great generosity to the Godstow nuns, making them cash grants and giving them timber for their building projects. Soon gossip was circulating that Henry II’s desire for an annulment of his marriage was not in order to wed Rosamund Clifford, but so that he could marry instead the sixteen-year-old Alix of France, a maiden whom he had already “unchastely, and with too much want of faith, dishonored.” Alix’s father Louis VII had betrothed her to Richard at the Montmirail settlement of 1169, and he had handed her over to be raised at her future father-in-law’s court.

Henry’s ravishing of young Alix was far more shameful to contemporaries than his affair with Rosamund Clifford, for he had taken advantage of a girl entrusted to him as his ward when she was only nine to remain in his household until she reached the proper age for marrying Richard. In taking her to his bed, he had not only violated her trust, but also the trust of her father, his lord the French king, as well as that of his own son. This affair had begun during the queen’s absences from court, but given the rapid circulation of rumors from the royal court, Eleanor heard of the scandal almost at once, whether still in Poitou or sequestered in England later.

The queen would learn that Henry did not limit his adulterous affairs to Alix of France while she was in captivity. He sired another illegitimate son by a Welsh woman, Nest, married to one of his knights from southwestern England. He acknowledged the boy, named Morgan, who became a cleric and eventually was named provost of Beverley, Yorkshire, a lucrative ecclesiastical living that English kings often granted to high-ranking royal servants. News of the king’s liaison with Alix must have left Eleanor appalled, for the king’s conduct not only grossly violated aristocratic standards of honorable behavior, but also betrayed and humiliated her favorite son.

It gave both Eleanor and Richard yet another grievance against Henry. According to a courtier’s hostile account, the king hoped by means of new heirs born to his new favorite that he might “be able effectually to disinherit his former sons by Eleanor, who had troubled him.” The story of Henry II’s seduction of Alix is not simply another scurrilous tale told by his enemies, for several sources corroborate it. Henry was curiously reluctant to carry out the princess’s long-delayed marriage to Richard, despite periodic protests from Louis VII and Philip II and from high-ranking churchmen including the pope complaining on their behalf.

Strongest evidence for the accusation’s accuracy, however, is Richard Lionheart’s own resistance to marrying Alix. Roger of Howden, a chronicler with access to court circles, records Richard’s excuse offered to Philip, her half-brother, for refusing to marry his betrothed of many years at the outset of the Third Crusade. He quotes Richard as telling the French king, “I do not reject your sister; but it is impossible for me to marry her, for my father had slept with her and had a son by her.” Richard then added that he could present many witnesses capable of testifying to the truth of his statement.

At the time, the English king was in the embarrassing position of preparing to take a Spanish princess as his bride, and he needed a potent excuse for breaking off his engagement to Alix. The Lionheart’s most respected modern biographer finds it difficult to discount Howden’s “explicit statement.” Furthermore, the Lionheart need not have lodged such a bitter accusation against his own father in order to justify his rejection of Alix; he could simply have declared that she had borne another man’s child without naming the father.

…As years passed Eleanor was allowed to make sojourns at other castles, certainly to Winchester and Windsor and perhaps as far west as Devonshire, where she had held substantial lands. Within Winchester Castle was a series of buildings that together formed the equivalent of a royal palace; and during Henry II’s reign repairs and additions to the residential quarters were constantly under way. At Winchester, the queen probably encountered her daughter-in-law, Margaret, wife of the Young King, who was a frequent visitor there, for works undertaken in 1174–75 included construction of an addition “where the young queen hears mass.”

In 1176, Robert Mauduit received a payment of almost three pounds by the king’s order, apparently for Eleanor’s expenses during Henry’s Easter court held that year at Winchester. That court marked the last time that she would see all four of her sons together. Richard and Geoffrey had crossed from France for the feast, and they returned to the Continent with their father. Henry the Young King and his queen also left England after Easter, and he would be away from the kingdom for three years before returning for another Easter court at Winchester.

The dullness of Eleanor’s life was brightened by the betrothal of her youngest daughter Joanne in 1176. The captive Eleanor had no voice in negotiations for the eleven-year-old girl’s hand, but she would have been filled with pride at Joanne’s selection as the bride of William II, king of Sicily. William’s kingdom was the creation of eleventh-century Norman adventurers incorporating both Sicily and the southern Italian mainland and heir to traditions of the island’s previous occupiers, Greeks, Romans, and Arabs.

Years earlier Eleanor had seen first-hand the island’s splendors at their height under King Roger II, when her ship from the Holy Land, blown off course, landed her at the cosmopolitan city of Palermo in 1149. By the time William succeeded to the throne, however, Sicily’s greatness was fading into a sort of “Indian summer.” Henry II had sought a Sicilian marriage for one of his daughters earlier, and the project was revived in May 1176, when ambassadors from the Sicilian royal court came to England. They were entertained at Winchester, where Joanne was residing and where Eleanor had remained for a time after the Easter court.

The young princess’s beauty impressed the envoys, and Henry agreed to her betrothal to the young Sicilian ruler. English emissaries set off for Sicily to negotiate the marriage settlement, arriving at Palermo in early August. Perhaps the queen helped in readying her daughter’s trousseau and prepared her for life at the Sicilian royal court by recalling her own visit there years earlier. After Joanne’s departure for her new home, her mother could not have expected to see her ever again, but chance would reunite them on two occasions many years later. In September 1176 Joanne left Winchester for Palermo, loaded with clothing, gold and silver plate, and other impressive gifts to take to her new island home; the cost of one of her robes, no doubt her wedding dress, was over £114.25

In February 1177 in the Palatine Chapel at Palermo, she married William, a young man of twenty-two, and her coronation as his queen quickly followed. Joanne’s Sicilian marriage aroused greater interest among the English than had her two elder sisters’ marriages earlier to foreign princes. English adventurers journeyed south to seek their fortunes, attracted by accounts of the island kingdom’s riches. Artistic and literary inspiration flowed northward from Sicily; mosaics in Sicily’s Byzantine-style churches influenced English wall-paintings and manuscript miniatures, and the Sicilian kingdom became a setting for English romances.”

- Ralph V. Turner, “A Captive Queen’s Lost Years, 1174–1189.” in Eleanor of Aquitaine: Queen of France, Queen of England

#eleanor of aquitaine#eleanor of aquitaine: queen of france queen of england#henry ii of england#alys of france#joan of england#high middle ages#history#medieval#richard i of england#ralph v. turner

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

I saw the Green Knight last night! (spoiler-ish discussion towards the end)

What a great big pile of stuff to think about. I haven’t been this surprised by a movie in a long time. It’s a very strange movie in almost every single way, incredibly interesting, and it’s received really glowing critical reviews. I’m torn though. Although it is a striking, strange movie, I feel a lot of the strangeness is style over substance, and amounts to strangeness for the sake of being strange, and I don’t think the movie is able to tie its themes up in the end to make a really emotionally coherent journey. It felt a bit like watching a student film (with a big budget), where it’s this totally fresh, exuberantly experimental thing that is so interesting and different… but needs a bit more polish on the plot to make it an actual story in its own right and not just a stylish experiment. A basic summary: if you want to see something totally different, this movie is for you, just don’t go in expecting an easy, polished Hollywood thriller.

Setting: gorgeous. It’s anachronistic medieval England, and despite the fact that it’s not trying to be historically accurate at all, oddly I feel it captures a better medieval vibe than anything else I’ve seen, period movie or medieval fantasy. At least in terms of the supernatural aspects??? The location: gorgeous. Absolutely gorgeous, haunting shots of trees and forests and countryside. (why are there so many shots that are way too dark though?) Sound design: Amazing. Beautiful. I can’t remember a movie that made as much or as effective use of quiet. The scoring is incredibly strange, a mix of haunting vocals of medieval songs, and spooky thrumming sound design. Quite striking. Quite interesting. (the intertitles are an interesting idea but I think they could be more effectively integrated, especially in a movie with so much visual creativity - thinking of, for instance, the subtitle joke in The Man who Killed Don Quixote)

But let’s emphasize one thing very clearly: this movie is in a surrealist style, and that’s not going to be for everyone, it just isn’t. I think it either “clicks” with you, or it simply doesn’t, and that’s ok. I like surrealism. My brain gets it. It’s a fantastic way to tell a story, and creates ambiguity that means everyone who watches it takes away something different. And here, a surreal approach is SO suitable because it’s based on this very old… story, mythology, fairy tale, whatever you want to call it. These old stories do have a strange, absurd, surreal quality to them. It’s perfectly fine when a modern adaption smooths out the strange corners of a story into something that feels more familiar to a modern audience. But it is DELIGHTFUL to watch a movie instead try to embrace that strangeness. I’ve never seen a movie that felt as much like an old fairy tale as this one does. It’s delightful.

HOWEVER.

As I said I’m not 100% sure it all works in the end. It’s a movie that looks absolutely gorgeous, certainly. It’s a movie that is different in almost every way from every single Hollywood movie I’ve seen in years and years, certainly. But without a stronger focus and ESPECIALLY a much tighter ending, I feel it really loses itself in its own strangeness sometimes, and becomes a series of very cool scenes that are fun to think about… but not really a solid story that people will go away talking about. And that is a huge, huge shame, because there IS a strong story in there that wanted to be told, that could have been told with just a little bit more finesse.

And here’s my last big surprise with this movie (spoiler discussion below):

This movie subverts the plot of the original story in an extremely interesting way, but here’s the dealio: I think this movie relies on the audience being familiar with the original plot. Although I don’t know for sure, I would be willing to bet that a significant portion of the audience will not be. I would say probably even the majority. The only reason I actually know the plot of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is that it was a story included in a book I bought for my kids a few years ago. So like. First of all, how can you effectively subvert a story, if a portion of the audience doesn’t even know how it differs? Maybe that’s fine in the end. Even if that’s fine though, there’s like. Great! Big! Huge! Plot points!!! that do not get explained or addressed! There will be a lot of people who have no idea that in the original story, the lord Gawain stays with is actually the Green Knight, who has been transformed by magic. His entire stay there is going to have an ENTIRELY different context to someone who has no familiarity with the story. The Lady’s brilliant and disturbing monologue about how she hates green and what the colour represents to her will have an extra layer of significance for a viewer who knows she is talking about her husband, and what that says about their relationship. The belt! The freaking green belt!!! It is extraordinarily surprising that Gawain decides to take it off at the end! If a viewer doesn’t understand exactly what the belt is supposed to do, that it DOES really, literally protect him and he absolutely WOULD survive the axe blow with it, would they understand how significant it is that he decides to take it off?

I think you COULD make a movie that doesn’t require the audience to know the story… I think you COULD make a movie where the two audience groups will have two very different experiences and each experience will be satisfying in its own way… I just think they didn’t pull it off in this case.

So.

I think there’s a really great story hiding in here about what makes an honorable man, what makes a meaningful life, and how a real man may or may not compare to a fairytale hero. I think there is a very very interesting and very different movie here that was really delightful to see, in a time when movie studios are churning out the same slick and safe formulaic crap. I think it has great performances, great production values. I just can’t necessarily say that it is a *good* movie.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deep dives into folklore: Gwaine and the green knight

The tale of Gawain and the Green Knight is a captivating narrative deeply rooted in medieval literature, encompassing elements of chivalry, honor, temptation, and redemption. Written anonymously in the late 14th century, it stands as one of the finest examples of Arthurian legend, rich with symbolism and moral complexity. Through a deep dive into its themes, characters, and historical context, we unravel the layers of this timeless story.

To understand Gawain's journey, it's essential to grasp the historical backdrop of the Middle Ages, characterized by feudalism, courtly love, and the code of chivalry. Arthurian legend was particularly popular during this period, serving as a moral compass for knights and nobles. Written in Middle English, Gawain and the Green Knight emerged within this milieu, reflecting the societal norms and values of its time.

The story begins with a mysterious figure, the Green Knight, challenging the knights of King Arthur's court to a game. Gawain, Arthur's nephew and a paragon of chivalry, accepts the challenge. He beheads the Green Knight, who then picks up his severed head and reminds Gawain of their agreement: in one year, Gawain must seek him out to receive a blow in return. The narrative follows Gawain's journey to fulfill his promise, encountering various trials and temptations along the way.

Themes:

Chivalry and Honor: Gawain's adherence to the code of chivalry is central to the narrative. He embodies virtues such as courage, loyalty, and honesty, striving to maintain his honor even in the face of adversity. The Green Knight's challenge tests Gawain's commitment to these ideals, presenting him with moral dilemmas that reveal the complexities of knighthood.

Temptation and Redemption: Gawain's encounter with Lady Bertilak and her attempts to seduce him add layers of psychological depth to the story. The exchange of kisses and the gift of a magical girdle challenge Gawain's fidelity and integrity. His moment of weakness underscores the human struggle between virtue and temptation. However, Gawain's confession and acceptance of the green girdle as a symbol of his fallibility demonstrate his capacity for redemption.

Nature and the Supernatural: The Green Knight's otherworldly nature blurs the boundaries between reality and the supernatural. His resilience after being beheaded and his association with nature suggest a deeper connection to the natural world. This mystical element heightens the sense of wonder and mystery surrounding the narrative, inviting interpretations that transcend the confines of reality.

Characters:

Gawain: As the protagonist, Gawain embodies the ideals of knighthood while also grappling with his humanity. His journey from valor to vulnerability showcases the complexities of his character, making him a relatable and compelling figure for audiences across generations.

The Green Knight: A symbol of the unknown and the enigmatic, the Green Knight serves as a catalyst for Gawain's quest. His unconventional appearance and supernatural abilities challenge conventional notions of heroism, adding an element of intrigue to the narrative.

Lady Bertilak: Lady Bertilak represents both temptation and agency within the story. Her seductive allure tests Gawain's resolve and complicates his moral journey. Despite her role as a temptress, she is also a fully realized character with her own desires and motivations.

Gawain and the Green Knight endures as a timeless masterpiece of medieval literature, captivating readers with its rich tapestry of themes, characters, and symbolism. Through its exploration of chivalry, honor, temptation, and redemption, the story resonates with audiences across cultures and generations, inviting reflection on the complexities of human nature and the eternal struggle between virtue and vice.

#writeblr#writers of tumblr#writing#bookish#booklr#fantasy books#creative writing#book blog#ya fantasy books#ya books#fiction writing#how to write#writers#writblr#writers on tumblr#writerscommunity#am writing#fantasy writer#female writers#story writing#teen writer#tumblr writers#tumblr writing community#writer problems#writer stuff#writerblr#writers community#writers corner#writers life#writerscorner

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Backlisted) Danielle Babbles About Books - The Life and (Medieval) Times of Kit Sweetly by Jamie Pacton

Rating: 5/5 stars

Sensitive content: I don’t remember a lot but it is written about and for people around 16-20 so, proceed with a little caution if you’re younger.

Review: Oh this was darling. It’s been over a year and a half but this book definitely earned its rating which, if you know me, I rarely give out. (The rest of this review was written for an assignment last year and then lost in the endless stream of work and avoiding work.)

Jamie Pacton’s debut novel The Life and (Medieval) Times of Kit Sweetly begins with several conflicts being set up. The first, and most important, is a moral and legal conflict: Kit, the main character, organizes with coworkers to fight for women in her theater dinner workplace to be allowed to work as “knights,” thereby allowing them the opportunity to hold positions with higher pay. This starts with her having to fill in for her older brother, who has the knight job she covets, on the fly. Her display during and after that performance winds up going viral on social media, giving her the momentum to start the fight. Her obstacles are the manger (her uncle), a couple of sexist coworkers, and the corporate board who set the rules in the first place.

There are also several contributing subplots put into play. There’s a conflict over where Kit should go to college – if she gets in anywhere – because her family’s financial situation makes both funding a college education and keeping her mother afloat nearly impossible. Her family’s dire financial straits have to do with her father’s abandoning the family some years before. Kit is also in love with her best friend and regrets a compact to never date him.

The novel doesn’t stray far from many well-worn tropes in the Young Adult genre. Kit is a highly motivated young woman who takes far too much responsibility upon herself. I’d find it unbelievable if I hadn’t known so many girls with similar resolve when I was that age. Kit has a few close friendships and has to make more friends for her dream of knighthood come true. As a teenager and a person there are some problems she can solve with creativity and hard work. And there are other problems that she can’t solve herself. She faces opposition to her attempts to change her workplace’s rules, family issues and emergencies, and the consequences of her own actions varying from chapter to chapter.

I came in worried that this story would be full of heavy-handed performative feminism but was pleasantly surprised. While I still question the validity of many of Kit’s claims about the medieval period in Europe being less rampantly sexist than is popularly believed, it’s useful for the plot. The story also goes well beyond that simplistic idea that girls should be able to do whatever boys do and brings intersectionality into the tale. Kit’s close friends are both people of color. The band of employees who get together to train for a demonstration in order to put greater pressure on the company to change the policy is diverse, representing not just the right of white women to participate in the same activities as white men, but equality for all genders, sexual orientations, and ethnicities. The characters are fleshed out and believable. It’s a delightful book and I look forward to reading more of Pacton’s work in the future. (I have read Lucky Girl now and it’s also great.)

Favorite Quote: can’t find one because my copy is 5,000 miles away and nobody’s pulled or posted quotes.

#the life and medieval times of kit sweetly#jamie pacton#danielle babbles about books#my reviews#book reviews#booklr#backlisted reviews

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Absurd Person #1 - Monkey D. Luffy (kid)

Let’s start with not only the main protagonist of One Piece but also the first character to give Luffy any sort of injury...

...his dumb, seven-year-old self...

*Disclaimer: I don’t own this image - screenshot from Episode of East Blue

The last time I wrote this, I forgot to hit save and my browser just reloaded the page and lost everything. After that I just went “I’m done” and rage quit Tumblr for the night (which I normally don’t do). That’s how my Sundays usually go😒🥴

Now Onward!

Basic Classifications

Real World Ethnicity/Nationality: Brazilian

Class: farm / country / lower class

Culture (the one he grew up around): Dawn Island - Sea-side village

Fishing community

Farming / Ranching community

Hard work ethic

Small and close community members; relatively friendly; little to non-existent conflict

Selective mix of being open towards strangers (especially with merchant vessels for better trading opportunities) and weariness towards those they expect to be harmful (likes Pirates; I’d imagine the people of Windmill Village were understandably unnerved with the Red-Haired Pirates first showing up).

Core values (personal to Luffy): pride, physical strength, adventures on and outside his home village,