#the interesting narrative of the life of olaudah equiano

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

rubynye replied to this post:

Olaudah Equiano: enslaved as a child, bought his own freedom, campaigned eloquently for abolition, his memoir went through nine printings at least. An erudite Black man from before many people think Black people were invented. I can't adequately express how happy seeing him in your list made me.

Equiano is a truly fascinating, compelling figure. His memoir was assigned in a grad school seminar I took on 18th-century British literature focused on various forms of resistance and dialogue among/between/about the oppressed, and it was really intriguing to read abolitionist poetry and tracts mainly by white English people across the political spectrum of their era and then Equiano's Interesting Narrative. The contrast is incredible.

He's in my dissertation for basically one passage—the account of his capture and lifelong separation from his sister. But it's a hell of a passage.

(Now that I'm thinking about it, he was also in the curriculum I designed when I took over my advisor's upper-division 18th-century class for a semester, and my undergrad students loved the Interesting Narrative, way more than the grad students in my own seminar had. Most of my students had no idea he'd even existed and they just really got into it.)

#rubynye#respuestas#olaudah equiano#eighteenth century blogging#ivory tower blogging#cw slavery#the interesting narrative of the life of olaudah equiano#nice things people say to me

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

The strong presence of the sea is grossly under-examined in American literature, doubly so in African American literature. As Elizabeth Schultz observes, "Historically and culturally, the African American experience has been an inland one. Black Americans," she continues, "have not generally turned seaward in their literature." Although she comes to a "however" that adds the observation "the sea is not absent from African American literature," the rhetorical pose imagined in the claim that "the sea is not absent" is that it will take a good deal of searching to find it. And yet, as Jeffery Bolster observes in his ground-breaking 1997 study Black Jacks, "Sailors wrote the first six autobiographies of blacks published in English before 1800". Many of these autobiographies carry clear abolitionist intent and hint at the type of anti-slavery discussions carried on by sailors around the Atlantic world. When scholars of African American literature turn their attention to works written by sailors, like Olaudah Equiano's The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavas Vassa, the African. Written by Himself (1789), most suffer from the misplaced assumption Schultz points to, and thus fail to see the crucial link between sailors and black abolitionism. Indeed, what Crispus Attucks, Paul Cuffee, Robert Smalls, Frederick Douglass, and so many other black revolutionaries in America have in common is that they were all sailors or in some other way directly connected to the maritime trades.

— Matthew D. Brown, 2013. “Olaudah Equiano and the Sailor’s Telegraph: The Interesting Narrative and the Source of Black Abolitionism.” Callaloo: A Journal of African Diaspora Arts and Letters 36 (1): 191–201. doi:10.1353/cal.2013.0059 (Google Drive link)

‘Drunken Sailors’ by John Locker, 1829 (NMM)

#age of sail#black history#black sailors#sailors#naval history#maritime history#atlantic world#abolitionism#black jacks#olaudah equiano#john locker#maritime art#black history month

184 notes

·

View notes

Text

References & Footnote

Abraham, R. C. 1933. The Tiv people. Lagos: Government Printer.

Afigbo, A. E. 1971. ‘The Aro of southeastern Nigeria: a socio-historical analysis of legends of their origins’, African Notes 6: 31–46.

Aglietta, M. and A. Orle´an (eds.) 1995. Souverainete´, le´gitimite´ de la monnaie. Paris: Association d’E´ conomie Financie‘re (Cahiers finance, e´thique, confiance).

Akiga Sai, B. 1939. Akiga’s story; the Tiv tribe as seen by one of its members. Translated and annotated by Rupert East. London: Published for the International African Institute by the Oxford University Press.

Akiga Sai, B. 1954. ‘The “descent” of the Tiv from Ibenda Hill’ (translated by Paul Bohannan), Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 24: 295–310.

Akin, D. and J. Robbins 1998. An introduction to Melanesian currencies: agencies, identity, and social reproduction, in D. Akin and J. Robbins (eds.), Money and modernity: state and local currencies in Melanesia, 1–40. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Bohannan, P. 1954. ‘The migration and expansion of the Tiv’, Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 24: 2–16.

Bohannan, P. 1955. ‘Some principles of exchange and investment among the Tiv’, American Anthropologist 57: 60–7.

Bohannan, P. 1958. ‘Extra-processual events in Tiv political institutions’, American Anthropologist 60: 1–12.

Bohannan, P. 1959. ‘The impact of money on an African subsistence economy’, Journal of Economic History 19: 491–503.

Carrier, J. 2010. Handbook of economic anthropology. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Curtin, P. D. 1969. The Atlantic slave trade: a census. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Dike, K. O. and F. Ekejiuba 1990. The Aro of south-eastern Nigeria, 1650–1980: a study of socio-economic formation and transformation in Nigeria. Ibadan: University Press.

Dorward, D. C. 1976. ‘Precolonial Tiv trade and cloth currency’, International Journal of African Historical Studies 9: 576–91.

Douglas, M. 1951. ‘A form of polyandry among the Lele of the Kasai’, Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 21: 1–12. (As Mary Tew.)

Douglas, M. 1958. ‘Raffia cloth distribution in the Lele economy’, Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 28: 109–22.

Douglas, M. 1960. ‘Blood-debts and clientship among the Lele’, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 90: 1–28.

Douglas, M. 1963. The Lele of the Kasai. London: Oxford University Press.

Douglas, M. 1964. ‘Matriliny and pawnship in Central Africa’, Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 34: 301–13.

Douglas, M. 1966. Purity and danger: an analysis of concepts of pollution and taboo. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Douglas, M. 1982. In the active voice. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. Downes, R. M. 1977. Tiv religion. Ibadan: Ibadan University Press.

Ekejiuba, F. I. 1972. ‘The Aro trade system in the nineteenth century’, Ikenga 1(1): 11–26, 1(2): 10–21. Eltis, D., S. D. Behrent, D. Richardson and H. S. Klein 2000. The transatlantic slave trade: a database. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Equiano, O. 1789. The interesting narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano: or, Gustavus Vassa, the African. New York: Modern Library Edition, 2004.

Graeber, D. 2001. Toward an anthropological theory of value: the false coin of our own dreams. New York: Palgrave.

Grierson, P. 1977. The origins of money. London: Athlone Press.

Guyer, J. I. 2004. Marginal gains: monetary transactions in Atlantic Africa. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Harris, R. 1972. ‘The history of trade at Ikom, Eastern Nigeria’, Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 42: 122–39.

Herbert, E. W. 2003. Red gold of Africa: copper in precolonial history and culture. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Ingham, G. 2004. The nature of money. Cambridge: Polity Press. Isichei, E. 1976. A history of the Igbo people. London: Basingstoke. Jones, G. I. 1939. ‘Who are the Aro?’, Nigerian Field 8: 100–3.

Jones, G. I. 1958. ‘Native and trade currencies in southern Nigeria during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries’, Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 28: 43–56.

Latham, A. J. H. 1971. ‘Currency, credit and capitalism on the Cross River in the pre-colonial era’, Journal of African History 12: 599–605.

Latham, A. J. H. 1973. Old Calabar 1600–1891: the impact of the international economy upon a traditional society. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Laum, B. 1924. Heiliges Geld: Eine historische Untersuchung ueber den sakralen Ursprung des Geldes. Tu¨ bingen: J. C. B. Mohr.

Le´vi-Strauss, C. 1949. Les structures e´le´mentaires de la parente´. Paris: EHESS.

Lovejoy, P. F. and D. Richardson 1999. ‘Trust, pawnship, and Atlantic history: the institutional foundations of the Old Calabar slave trade’, American Historical Review 104: 333–55.

Lovejoy, P. F. and D. Richardson 2001. ‘The business of slaving: pawnship in Western Africa, c. 1600–1810’, Journal of African History 42: 67–84.

Malamoud, C. (ed.) 1988. Lien de vie, noeud mortel. Les repre´sentations de la dette en Chine, au Japon et dans le monde indien. Paris: EHESS.

Northrup, D. 1978. Trade without rulers: pre-colonial economic development in south-eastern Nigeria. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Nwauwa, A. O. 1991. ‘Integrating Arochukwu into the regional chronological structure’, History in Africa 18: 297–310.

Ottenberg, S. 1958. ‘Ibo oracles and intergroup relations’, Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 14: 295–317.

Ottenberg, S. and P. Ottenberg 1962. Afikpo markets: 1900–1960, in P. Bohannan and G. Dalton (eds.), Markets in Africa, 118–69. Chicago, IL: Northwestern University Press.

Partridge, C. 1905. Cross River natives: being some notes on the primitive pagans of Obubura Hill District, Southern Nigeria. London: Hutchinson & Co.

Price, J. M. 1980. Capital and credit in British overseas trade: the view from the Chesapeake, 1700–1776. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Price, J. M. 1989. ‘What did merchants do? Reflections on British overseas trade, 1660–1790’, The Journal of Economic History 49: 267–84.

Price, J. M. 1991. Credit in the slave trade and plantation economies, in B. L. Solow (ed.), Slavery and the rise of the Atlantic system, 313–17. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rospabe´, P. 1995. La Dette de Vie: aux origines de la monnaie sauvage. Paris: Editions la De´couverte/MAUSS.

Rubin, G. 1975. The traffic in women: notes on the ‘political economy’ of sex, in R. Reiter (ed.), Toward an anthropology of women. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Servet, J.-M. 1981. ‘Primitive order and archaic trade. Part I’, Economy and Society 10: 423–50. Servet, J.-M. 1982. ‘Primitive order and archaic trade. Part II’, Economy and Society 11: 22–59. Sheridan, R. B. 1958. ‘The commercial and financial organization of the British slave trade, 1750–1807’, The Economic History Review, New Series 11: 249–63.

Smith, A. 1776. An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations. Oxford: Clarendon Press (1976 edition).

Tambo, D. C. 1976. ‘The Sokoto Caliphate slave trade in the nineteenth century’, International Journal of African Historical Studies 9: 187–217.

The´ret, B. 1995. L’E´ tat, la finance et le social. Souverainete´ nationale et construction europe´enne (direction de publication). Paris: E´ ditions la De´couverte.

Walker, J. B. 1875. ‘Notes on the politics, religion, and commerce of Old Calabar’, The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 6: 119–24.

Wilson, M. H. 1951. ‘Witch beliefs and social structure’, The American Journal of Sociology 56: 307–31.

[1] Some village wives were literally princesses, since chiefs’ daughters invariably chose to marry age sets in this way. The daughters of chiefs were allowed to have sex with anyone they wanted, regardless of age-set, and also had the right to refuse sex, which ordinary village wives did not. Princesses of this sort were rare: there were only three chiefs in all Lele territory. Douglas estimates that the number of Lele women who became village wives on the other hand was about 10% (1951).

#reading lists#Africa#anthropology#debt#economics#money#violence#african politics#african economics#anarchism#anarchy#anarchist society#practical anarchy#practical anarchism#resistance#autonomy#revolution#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#daily posts#libraries#leftism#social issues#anarchy works#anarchist library#survival#freedom

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

for Juneteenth i recommend Toni Morrison's Beloved. it is of course appropriately intense and is based off of real stories of Black women dealing with/fleeing slavery and the sacrifices they have to make. (be warned, that is putting it lightly)

for 19th century poetry, check out Phillis Wheatley

for a 19th century slave narrative, Harriet Jacobs' autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

for perhaps one of the earliest mass published narratives written by a Black man, Olaudah Equiano's Interesting Narrative is an 18th century autobiographical account

as always essays by Frederick Douglass are an important read, please give me a moment to pare down the catalog and find the ones I'm thinking of, but Ive read a lot of his essays from his time in Ireland which puts a lot of perspective on modern moralized politics if anything

Most of the above (apart from Beloved i believe) are available in the public domain. I know I didn't provide links but having the names to look up may help in breaking into the history of Black narratives written by Black people. My knowledge lies more within the 18th and 19th centuries so thats why there are so many from that time period.

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

here are some of the books we had to read in secondary school to add to your reading list if you wanna include some non-american canon: - vanity fair - william makepeace thackeray (social satire) - jamaica inn - daphne du maurier (smuggler thriller/murder mystery) - the interesting narrative of the life of olaudah equiano - olaudah equiano (ex-slave autobiographical novel) - all quiet on the western front - erich maria remarque (semi-autobiographical great war novel) - the forme of cury (this is literally just a cookery book from the 1300s but i remember being fascinated by it) - the canterbury tales - chaucer (social satire of medieval pilgrims) - silas marner - george eliot (miserly hoarder becomes a Better Man) - north and south - elizabeth gaskell (social novel, tradition vs modernity) - far from the madding crowd - thomas hardy (basically just a love story really) - small island - andrea levy (racism in 1940s britain) - richard ii - shakesy (a king un-kings himself after having a breakdown on a welsh beach because his boyfriend got beheaded) (i KNOW you said you wanted to read more, BUT if you don't like reading plays by yourself, i highly recommend watching the 2012 adaptation directed by rupert goold because it's got a lovely rhythm to it that really emphasises the fact the play is written entirely in verse and contains no prose) - oranges are not the only fruit - jeanette winterson (lesbian girl in a very religious community) - the tenant of wildfell hall - anne bronte (female artist falls foul of gossip and scandal)

this is so funny i've read a bunch of these aflakdsjf thank you!! padding out my list... obsessed with the 1300s cookbook???

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

MOGAI BHM- Belated Day 18!

happy BHM! today i’m going to be talking about seminal Black authors! there are way too many to fit into one post, so i’m choosing a few for this post and including more resources at the end for looking further into the subject!

Phillis Wheatley-

[Image ID: A fuzzied portrait-style painting of Phillis Wheatley, a thin Black women. In the painting, she has a somewhat stoic expression on her face, and her hair is up in a crown of braids. She is wearing a pair of dangling earrings, a pearl necklace, and an off-the-shoulder, puffy-short-sleeved white gown. End ID.]

Phillis Wheatley was perhaps the very first Black person to become a famous writer in America. She was enslaved, but her owners believed she was exceptionally smart, so they taught her to read and write. Phillis began writing poetry at a very young age, and at the age of 13, she published her first poem, called “An Elegiac Poem, on the Death of that Celebrated Divine, and Eminent Servant of Jesus Christ, the Reverend and Learned George Whitefield ...”, or the Whitefield Elegy, which elevated her to national fame.

Phillis was rejected by many publishing houses in the North because she was of African descent, so she went to London publishing houses instead. There, she met with many noted abolitionists and activists of the time, including Benjamin Franklin. By the age of 18, she had published 28 poems. Her poem anthology, “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious, And Moral” was the first collection of poems ever published by an African-American person.

Phillis was deeply religious. She often incorporated biblical themes into her writing, and she wrote many elegies, poems about notable people, and poems about her employers. She also wrote poetry about slavery in America, and combined biblical commentary with poetic depictions of slavery to decry the institution. An example of this is her most well-known poem, “On Being Brought From Africa To America”.

It is now believed that Phillis Wheatley wrote around 145 poems, though not all of them were published. She has been both heavily criticized and heavily praised by Black literature critics, but the significance of her poetry and her efforts are undeniable.

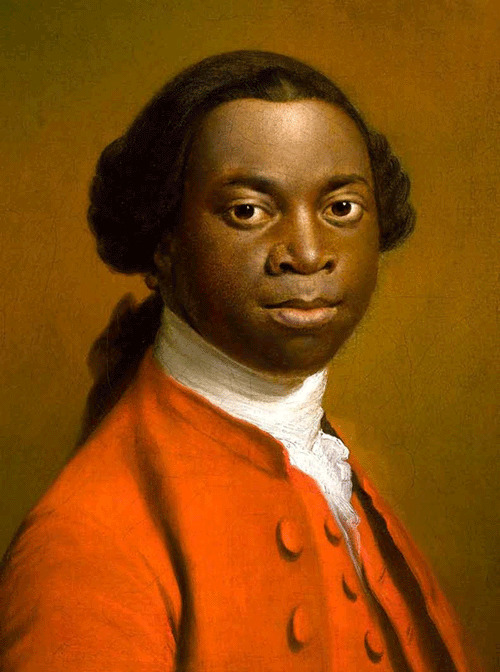

Olaudah Equiano-

[Image ID: A color portrait-style painting of Olaudah Equiano, a thin Black man. The painting has a brown background. In the painting, he is wearing his hair in the style of George Washington’s hair, and he’s wearing a two-layered, red, buttoned overcoat over a fancy white turtle-neck. End ID.]

A contemporary of Phillis Wheatley, Olaudah Equiano was born to Igbo heritage in West Africa. When he was only eleven, he was kidnapped into slavery. After a few years of travelling with his master, learning the mariner’s trade and being sold a few more times, he was allowed to purchase his own freedom, and after he did so, he moved to London, where he joined the abolition and anti-slavery movement active there. There, with a friend named Ottobah Cugoano, he advocated fiercely for the end of the slave trade.

In 1789, Olaudah’s abolitionist efforts culminated in his publishing of his autobiography, called “The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African”. This book was a narrative and exploration of his experiences during his kidnapping, selling, the Middle Passage, and his few years of being enslaved. This autobiography became very popular, and it ushered in a new genre, dubbed the ‘slave narrative’ genre, wherein Black people wrote narratives of their experiences with slavery. This genre helped sustain and advance abolitionist movements.

His narrative was internationally popular. It went through nine editions in some places, was translated into many languages, and became a huge part of abolitionist scholarly work. When he died in 1797, Olaudah hadn’t gotten the chance to see any British action against slavery, but he nonetheless was pivotal in inspiring such action, even posthumously.

Maya Angelou-

[Image ID: A black-and-white photograph of Maya Angelou, a thin Black woman. In the photograph, she is smiling and her hair is held up in a checkered head scarf. She’s wearing a fancy, intricately patterned dress with flower patterns and checker patterns. End ID.]

Born in 1928, Maya Angelou was many, many things- a singer, an actress, a director (Hollywood’s first Black female one), a teacher, an activist, and a dancer- but she was most famous for her writing. Maya was a humanitarian civil rights activist who worked with both Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, and her writing was a beautiful example of her deep drive for justice. In her civil rights work, she was the northern coordinator of Dr. King’s SCLC.

Maya had a traumatic childhood, which she expressed through her most famous work, the one that promoted her to national and even international fame amongst circles of writers, called “I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings”. In this autobiography, she spoke of her childhood, including the trauma behind how her love for language developed. Maya was a contemporary of another massively famous and important Black author, James Baldwin, who convinced her to write “I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings” after she returned from living in Cairo and Ghana with her son.

Maya Angelou wrote other autobiographies as well- 6 all totaled. These biographies depicted real-life experiences with racism, sexual abuse, sexism, and other deep issues, which have made her autobiographies somewhat controversial to some. In her final autobiography, titled “A Song Flung Up To Heaven”, she discussed the span of four years in which so much racial violence, including the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, had such a deep impact on her and the Black community in America. She spoke about how difficult it was to express that pain, and the impact those events had on her.

Maya Angelou was also an incredibly accomplished poet. Her poetry, including volumes like “Just Give Me A Cool Drink Of Water ‘Fore I Diiie”, was very diverse- she wrote about Black beauty and Black pride, womanhood, Black womanhood, social justice, Black American experiences, sexuality, and anti-war activism, and her poetry is perhaps best known for its unabashed celebration of Black female power.

Maya Angelou also wrote several children's books throughout the 1990s, including “My Painted House, My Friendly Chicken, And Me” and “Mrs. Flowers: A Moment Of Friendship”. She has won many Pulitzer Prizes for her work, and is one of the most prolific and influential Black female writers of all time. She passed away in 2014.

James Baldwin-

[Image ID: A black-and-white photograph of James Baldwin, a thin Black man with short greying, curly black hair. In the photograph, he has his head rested in the palm of his hand and the other arm laying on a table in front of him as he sits, looking to be deep in thought, in front of a crowded bookshelf. He’s wearing two watches and a denim button-up short-sleeved shirt. End ID.]

Born in 1924, James Baldwin grew up in poverty in Harlem. Having always had a passion for Black justice, he grew up feeling like an outsider due to being a Black gay man. Throughout his life, he would write about the intersectionality of Blackness and sexuality, long before terms for the concept of intersectionality were outlined.

Baldwin is most famous for his earlier works, which he published during the 1950s and the 1960s, the heart of the civil rights movement. Baldwin did work closely with notable civil rights activists. His two first novels were two of his most famous- Go Tell It On The Mountain, a semi-autobiographical work about his childhood and Black issues, and Giovanni’s Room, a book that was ahead of its time for depicting the white world but especially for depicting the struggles of a bisexual man. Around the same time, he published his first collection of essays, titled Notes of A Native Son.

He published another book of essays, called Nobody Knows My Name, in 1961, which became a huge part of Black civil rights movement literature and is known for exploring interracial dynamics and relationships during the time period. This theme, coupled with themes of sexuality, also dominated a second book of his, called Another Country.

Baldwin, who lived in Paris for awhile in later commuted back and forth between America and Paris, embraced an outsider’s position. He was able to gain an outside view of America through living in Paris- he felt that he could not truly be a writer in America due to the stress of always having to look over his shoulder and the suppression he faced in the field as a Black gay man. His work reflected an international view of American racial dynamics.

An article about Baldwin on Black Muslim separatist politics, published in a newspaper in the early 1960s, was turned into a best-selling Baldwin work called The Fire Next Time, undoubtedly one of Baldwin’s most famous works. James Baldwin is also known for his plays- one of which, Blues For Mister Charlie, was performed on Broadway.

Throughout his life, James Baldwin forged a unique path for himself, exploring the realms of Black masculinity and Black sexuality and gender- which both ostracized and elevated him. Today, he is rightfully considered one of history’s most influential and seminal Black writers, and he remains the paradigm for Black gay male literature.

Toni Morrison-

[Image ID: A color photograph of Toni Morrison, a heavier Black woman with long, thick, greying dreadlocks tied back in a braid. She’s sitting at a table with her hands folded, and she’s wearing a loose grey cardigan over a black shirt. End ID.]

Undoubtedly one of the most famous, influential, and seminal Black authors of all time, Toni Morrison is perhaps most well-known for her fierce exploration of Black issues in her work, including colorism, slavery, misogynoir, and Black relationships and love. Black culture and storytelling was very formative in her childhood, and influenced the content of her work. An alumnus of Howard University, a famous HBCU, she taught there for several years. In 1993, she won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

In 1970, Morrison released her first book, a novel called The Bluest Eye. A bold novel about beauty standards in the Black community, it told the story of a Black girl who wanted deeply to have blue eyes and was heavily influenced by white beauty standards. This theme of body image issues among Black girls and how colorism affects them, was also echoed in a much later (2015) Morrison work entitled God Help The Child.

Some other seminal works written by Toni Morrison are Beloved, Song of Solomon, and Jazz. Beloved, which won a Pulitzer Prize, tells the tragic true story of an enslaved woman who tried to escape but was recaptured, causing her to kill her infant daughter because she wanted her to escape a lifetime of slavery. Song of Solomon, a tale from the perspective/narration of a Black man trying to find his identity, elevated Morrison to national fame. Jazz, a 1992 novel set in the 1920s, was about passion and violence during the time period.

Toni Morrison has also written several childrens books along with her son, as well as essays and speeches, the latter two of which have been compiled in such volumes as “What Moves at the Margin: Selected Nonfiction” and “The Source of Self-Regard: Selected Essays, Speeches, and Meditations”. In 2005, Morrison won the Coretta Scott King Award for her book Remember, which chronicled the lives of Black children during the fight for school integration during the Civil Rights Movement. In 2019, after passing away at the age of 88, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Honor.

Amiri Baraka-

[Image ID: A black-and-white photograph of Amiri Baraka, a thin Black man with an afro and a beard. In the photograph, he has a stoic expression on his face, and he’s wearing a black cloak of sorts with a necklace over his garments. He’s standing at a podium crowded with several microphones and gripping the side of the podium. End ID.]

Born in 1934, Amiri Baraka was for decades one of the most prominent Black voices in American literature, especially as it pertained to civil rights and racial justice. After attending Howard University, an HBCU, and spending 3 years in the Air Force, he began publishing very incendiary works, like his essays and poetry, which spoke fiercely about racial pride and racial justice, and were often very difficult for white audiences to engage with.

In the 1950s, he aligned himself with beat poetry and beat poets like Allen Ginsburg and Jack Kerouac, and in the 1960s, he became more radical, aligning himself with Black nationalism and the Black Power movement. He is well-known for his poetry about Black politics, which was critical to the literature of the Black Power Movement. In 1965, he ushered in the Black Arts Movement by founding a studio theater for Black artists in Harlem.

Amiri Baraka aligned himself more with third-world movements during the 1970s. His plays and poetry expressed his desires, and though he remains controversial to this day, he is also undoubtedly one of the most important Black writers from the Civil Rights Movement and Black Power eras.

Summary-

Phillis Wheatley, the first famous Black American writer, wrote large amounts of poetry during the 18th century, and was propelled to national and international fame

Olaudah Equiano, a contemporary of Phillis Wheatley, helped largely to promote British abolitionist politics through his internationally famous autobiography which he published in 1789

Maya Angelou was a multitalented singer, dancer, actress, and most famously a writer whose poetry and memoirs detailed civil rights and Black existence in America

James Baldwin was a Black gay man who was active in the Civil Rights Movement and wrote seminal works about Black sexuality

Toni Morrison, who won the Nobel Prize in 1993, explored Black womanhood, Black culture, Black community dynamics, and Black sexuality through her prolific novels and writings

Amiri Baraka was a controversial, nationalist Black artist who wrote incendiary essays and poetry about Black identity and Black power, and helped found the Black Arts Movement

tagging @metalheadsforblacklivesmatter @bfpnola @intersexfairy

Sources-

https://www.britannica.com/art/African-American-literature/Prose-drama-and-poetry

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/phillis-wheatley

https://npg.si.edu/blog/phillis-wheatley-her-life-poetry-and-legacy

https://slaveryandremembrance.org/people/person/?id=PP003

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Olaudah-Equiano

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/maya-angelou

https://www.mayaangelou.com/

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Toni-Morrison

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/amiri-baraka

https://poets.org/poet/amiri-baraka

https://www.britannica.com/biography/James-Baldwin

https://www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/james-baldwin-s-sexuality-complicated-influential-n717706

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Olaudah Equiano (c. 1745 – March 31, 1797) whose father was an Ibo chief, was born in Southern Nigeria. At the age of 11 years, he was captured by African slave traders and sold into bondage in the New World. He was given the name Gustavus Vassa and was forced to serve several masters. While a slave, he traveled between four continents.

He mastered reading, writing, and arithmetic, and purchased his freedom. He presented one of the first petitions to the British Parliament calling for the abolition of slavery.

He became the first person of African ancestry to hold a post in the British Government when he was appointed to the post of Commissary for Stores to the Expedition for Freed Slaves. This abolitionist-supported venture would create the West African nation of Sierra Leone. He soon began to witness fraud and corruption among those responsible for providing supplies for the expedition. His unwillingness to accommodate this malfeasance led to his dismissal.

He continued to work with leading British abolitionists including William Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson who urged Parliament to abolish the Slave Trade. He interjected his history into the struggle when in 1789 he wrote and published his autobiography titled The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vassa the African, Written by Himself. His narrative soon became the first “best seller” written by a Black Briton. He embarked on a lecture tour of England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland to promote his book. He advanced several religious and economic arguments for the abolition of slavery.

He married an Englishwoman, Susanna Cullen (1792) and the couple had two daughters. He died ten years before the slave trade was abolished and 36 years before Parliament outlawed slavery throughout the British Empire. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

List of all the books I’ve read

just wanted to keep a list of what I’ve read throughout my life (that I can remember)

Fiction:

“Where the Red Fern Grows,” Wilson Rawls

“The Outsiders,” S. E. Hinton

“The Weirdo,” Theodore Taylor

“The Devil’s Arithmetic,” Jane Yolen

“Julie of the Wolves series,” Jean Craighead George

“Soft Rain,” Cornelia Cornelissen

“Island of the Blue Dolphins,” Scott O’Dell

“The Twilight series,” Stephanie Mayer

“To Kill a Mockingbird,” Harper Lee

“Gamer Girl,” Mari Mancusi

“Redwall / Mossflower / Mattimeo / Mariel of Redwall,” Brian Jacques

“1984,” and “Animal Farm,” George Orwell

“Killing Mr. Griffin,” Lois Duncan

“Huckleberry Finn,” Mark Twain

“Rainbow’s End,” Irene Hannon

“Cold Mountain,” Charles Frazier

“Between Shades of Gray,” Ruta Sepetys

“Great Short Works of Edgar Allan Poe,” Edgar Allan Poe

“Lord of the Flies,” William Golding

“The Great Gatsby,” F Scott Fitzgerald

“The Harry Potter series,” JK Rowling

“The Fault in Our Stars,” “Looking for Alaska,” and “Paper Towns,” John Green

“Thirteen Reasons Why,” Jay Asher

“The Hunger Games series,” Suzanne Collins

“The Perks of Being a Wallflower,” Stephen Chbosky

“Fifty Shades of Grey,” EL James

“Speak,” and “Wintergirls,” Laurie Halse Anderson

“The Handmaid’s Tale,” Margaret Atwood

“Mama Day,” Gloria Naylor

“Jane Eyre,” Charlotte Bronte

“Wide Sargasso Sea,” Jean Rhys

“The Haunting of Hill House,” Shirley Jackson

“The Chosen,” Chaim Potok

“Leaves of Grass,” Walt Whitman

“Till We Have Faces,” CS Lewis

“One Foot in Eden,” Ron Rash

“Jim the Boy,” Tony Earley

“The Vanishing Act of Esme Lennox,” Maggie O’Farrell

“A Land More Kind Than Home,” Wiley Cash

“A Parchment of Leaves,” Silas House

“Beowulf,” Seamus Heaney

“The Silence of the Lambs / Red Dragon / Hannibal / Hannibal Rinsing,” Thomas Harris

“Cry the Beloved Country,” Alan Paton

“Moby Dick,” Herman Melville

“The Hobbit / The Lord of the Rings trilogy / The Silmarillion,” JRR Tolkien

“Beren and Luthien,” JRR Tolkien, edited by Christopher Tolkien

“Children of Blood and Bone / Children of Virtue and Vengeance,” Tomi Adeyemi

“Soundless,” Richelle Mead

“The Girl with the Louding Voice,” Abi Dare

“A Song of Ice and Fire series / Fire and Blood,” GRR Martin

“A Separate Peace,” John Knowles

“The Bluest Eye,” and “Beloved,” Toni Morrison

“Brave New World,” Aldous Huxley

“The Giver / Gathering Blue / Messenger / Son,” Lois Lowry

“The Ivory Carver trilogy,” Sue Harrison

“The Grapes of Wrath,” and “Of Mice and Men,” John Steinbeck

“The God of Small Things,” Arundhati Roy

“Fahrenheit 451,” Ray Bradbury

“The Night Circus,” Erin Morgenstern

“Sunflower Dog,” Kevin Winchester

‘A Tree Grows in Brooklyn,” Betty Smith

“The Catcher in the Rye,” JD Salinger

“The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian,” Sherman Alexie

“Bridge to Terabithia,” Katherine Paterson

“The Good Girl,” Mary Kubica

“The Last Unicorn,” Peter S Beagle

“Slaughterhouse Five,” Kurt Vonnegut Jr

“The Joy Luck Club,” Amy Tan

“The Sworn Virgin,” Kristopher Dukes

“The Color Purple,” Alice Walker

“Their Eyes Were Watching God,” Zora Neale Hurston

“The Light Between Oceans,” ML Stedman

“Yellowface,” RF Kuang

“A Flicker in the Dark,” Stacy Willingham

“One Piece Novel: Ace’s Story,” Sho Hinata

“Black Beauty,” Anna Seawell

“The Weight of Blood,” Tiffany D. Jackson

“Mulberry and Peach: Two Women of China,” Hualing Nieh, Sau-ling Wong

“The Weight of Blood,” Laura McHugh

“Everybody’s Got to Eat,” Kevin Winchester

“That Was Then, This is Now,” S. E. Hinton

“Rumble Fish,” S. E. Hinton

Non-fiction:

“Anne Frank: Diary of a Young Girl,” Anne Frank

“Night,” Elie Wiesel

“Invisible Sisters,” Jessica Handler

“I Am Malala: The Story of the Girl Who Stood Up for Education and was Shot by the Taliban,” Malala Yousafzai

“The Interesting Narrative,” Olaudah Equiano

“The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks,” Rebecca Skloot

“Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl,” Harriet Jacobs

“The Princess Diarist,” Carrie Fisher

“Adulting: How to Become a Grown Up in 468 Easy(ish) Steps,” Kelly Williams Brown

“How to Win Friends and Influence People,” Dale Carnegie

“Carrie Fisher: a Life on the Edge,” Sheila Weller

“Make ‘Em Laugh,” Debbie Reynolds and Dorian Hannaway

“How to be an Anti-Racist,” Ibram X Kendi

“Maus,” Art Spiegelman

“I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings,” Maya Angelou

“Wise Gals: the Spies Who Built the CIA and Changed the Future of Espionage,” Nathalia Holt

“Persepolis,” and “Persepolis II,” Marjane Satrapi

“How to Write a Novel,” Manuel Komroff

“The Nazi Genocide of the Roma,” Anton Weiss-Wendt

“Children of the Flames: Dr. Josef Mengele and the Untold Story of the Twins of Auschwitz,” Lucette Matalon Lagnado and Sheila Cohn Dekel

“Two Watches,” Anita Tarlton

“The Ages of the Justice League: Essays on America’s Greatest Superheroes in Changing Times,” edited by Joseph J. Darowski

“Shockaholic,” Carrie Fisher

“Breaking Loose Together: the Regulator Rebellion in Pr-Revolutionary North Carolina,” Marjoleine Kars

#books#some of these I read for school assignments and some I read of my own volition#some I read when I was a young teenager many years ago and some I read just this past month#somewhat in order of which I read them#some of these I have read more than once#for the record I work at a library which is how I'm able to access so many books#support your local library#also just because I read these books doesn't necessarily mean that I would recommend all of them to just anyone#don't come at me for reading 'problematic' books please#I was an english major in college and didn't get to choose a lot of what I read#but even the ones I was forced to read I'm glad that I read them#I don't really regret reading any of these; even the one's that I didn't like#I will add to the list whenever I finish a book#annemariereads

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Also: The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano - i.e., the autobiography of an incredible freed slave and abolitionist living in Great Britain in the 1700s? "I am neither a saint, a hero, nor a tyrant"?

Also also: why not read outside the European/USAmerican canon? One Thousand And One Nights? The Tale of Genji?? The freaking Epic of Gilgamesh???

Toni Morrison? Alice Walker? Zora Neale Hurston? Ralph Ellison? James Baldwin? Lorraine Hansbury? Maya Angelou? Octavia Butler? Langston Hughes? Bell Hooks? Many many many many others? Go fuck yourself you lazy, anti-intellectual asshole

37K notes

·

View notes

Text

the interesting narrative of the life of olaudah equiano vs the clones i could make many points between

0 notes

Text

OLAUDAH EQUIANO [GUSTAVUS VASSA] The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African (1789)

It is difficult for those who publish their own memoirs to escape the imputation of vanity; nor is this the only disadvantage under which they labor: it is also their misfortune, that what is uncommon is rarely, if ever believed, and what is obvious we are apt to turn from with disgust.

People generally think those memoirs only worthy to be read or remembered which abound in great or striking events, those in short which in a high degree excite either admiration or pity: all others they consign to contempt and oblivion.

0 notes

Text

Commonplace Entry 5: Olaudah Equiano [The Middle Passage]

Olaudah Equiano exposed the mind of the enslaved African when he penned his experiences. Wrote Equiano, "I asked if we were not to be eaten by those white men with horrible looks, red faces loose hair" (982).

Thanks to the ability of Equiano to formally and adequately express himself in writing and speak for himself for the first time English, the people of England were able to reflect on their actions more acutely than ever before. What seems for the first time in English literature, white people's humanity is being questioned. It is likely that Equiano's fear for being eaten seemed absurd to those never having been in his shoes. This world view likely would have been violating to the conscience and awake the interest and compassion of the highest Society of readers, particularly those in government positions.

Equiano, Olaudah. The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, The African, Written by Himself, The Norton Anthology of English Literature, 10th Edition, Volume C, The Restoration and The Eighteenth Century, New York, London, W.W. Norton Company, 2018, pp. 982.

#critiqueofcolonialism#critiqueofslavery#18th century literature#Olaudah Equiano#TheMiddlePassage#theother#Liberty

0 notes

Text

Historian and broadcaster David Olusoga has been the face of a decolonial turn in British broadcasting that, in recent years, with series including the Bafta-winning Britain’s Forgotten Slave Owners, A House Through Time and Black and British: A Forgotten History, has inspired new conversations about injustice in the story of Britain and Britishness in living rooms across the country. Anticipating this year’s Black History Month (October), he has contributed a foreword to the republication by Hodder & Stoughton of The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, the memoir of an 18th-century formerly enslaved man that is also widely recognised as a foundational text of Black British literature.

What led you to get behind this republication of Equiano’s memoir? It’s a book I read at university and that has been part of my life for 30 years. I think it’s the most important of the British narratives of people who were enslaved. Equiano is someone who managed to purchase his way out of slavery, to travel the world as a Black person in an age where you could be kidnapped and transported back into slavery. He was a skilled sailor, a political operator. He became a public figure when this country was the biggest slave-trading nation in the North Atlantic. There are many voices that come out of the experience of British slavery but none of them have the same impact as Equiano.

You’ve been a key advocate of Black History Month. Why do we need Black history? And how would you describe the impact of Black History Month in supporting that need? Black History Month in Britain has been an amazing success. It’s an American tradition that began life as Negro History Week. It was brought to Britain in 1987, so not very long ago. Since then we’ve made it into an institution, a part of the British calendar. This is a real achievement. Black people have had their history written out – sometimes deliberately, sometimes systematically – of Britain’s story because it’s the history of slavery and empire and that doesn’t fit in with the comforting island story narrative. Black people were told that they had no history – Hegel said that Africa’s a place with no history – and that double act of erasure and denial meant that Black people had no story to explain why they were in Britain or how their relationship with Britain had been forged. I think it’s both tragic and amazing that those 492 people that got off the Windrush in June 1948 and made their homes in London and Bristol and Liverpool didn’t know that they were making their homes in cities where there had been previous generations of Black Britons – Black Victorians, Black Georgians. Imagine what it might have meant to the Windrush generation, when people said: “What are you doing here, what right do you have to be here, what’s your connection to Britain?”, when they were confronted with racism and told that they belonged in Africa or that they had no right to be here. Imagine what strength they might have drawn from that history had it been known.

What are the top three titles on your Black history reading list? One of the most important books for me personally was Peter Fryer’s book Staying Power, which I read when I was 16. It’s just been republished [by Pluto Press] with a fantastic foreword by Gary Younge. I’m a big admirer of Miranda Kaufmann’s book Black Tudors. Sam Selvon’s novel The Lonely Londoners is an incredibly poignant and meaningful book that I think, more than anything I’ve ever read, can transport you into the experiences of what it was like to be Black in Britain in the early 50s. And I think we should all be reading Paul Gilroy. Books like There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack. Paul is just a giant figure; I fear that we won’t recognise who Paul is until he’s gone. I don’t think many people really got who Stuart Hall was and what his significance was until he had gone, and I think that often happens to Black writers. That they’re understood in retrospect. Paul has been appallingly neglected by TV.

Why do you think that is? I think there’s a subconscious discomfort with the idea of Black intellectuals. If you go to an American university where Henry Louis Gates teaches, or Cornel West, you have to apply in a lottery to get on to those courses. People sneak into those lectures. People like Michael Eric Dyson as well. Nikole Hannah-Jones. They are celebrated as Black thinkers, Black intellectuals. Ibram X Kendi is celebrated. There’s a star feeling around these people. We don’t have that. We’ve never had that.

Isn’t that you? No, I’m a TV presenter.

Who are the contemporary decolonial writers you’re most excited about? One of the great positives of recent years is how many scholars from Indian backgrounds are studying the British empire and transforming the field. Priya Satia, with her book Time’s Monster. Sathnam Sanghera with Empireland. Ian Sanjay Patel with We’re Here Because You Were There. I long to see Black British writers alongside those south Asian writers, alongside people from the Caribbean and African American writers making the Black British experience more global. To take the life of Equiano, for example, you can’t understand Equiano’s life just in Britain. This is someone who was, we think, born in Africa, enslaved in the Caribbean, who travelled the world and would, were it not for a decision he made, have gone to Sierra Leone and possibly died there. This is a global work. He travelled thousands and thousands of miles. He lived much of his life on that great empire of the sea. It’s a global life and indicative and typical of what it is to be Black and British.

What are you reading at the moment? Long after everyone else, I’m reading Afropean by Johny Pitts, I’m rereading The Slave Ship by Marcus Rediker, because it’s an absolutely fantastic book. I’ve got Imperial Nostalgia by Peter Mitchell to start and I’m reading Hugh Kearney’s The British Isles. I also have my old copy of The Lion and the Unicorn by Orwell, because I keep quoting from it. It just keeps being horribly relevant and I thought I’d read the whole thing again for the first time in many years. Orwell had this idea that there was a form of leftwing British patriotism that could be reached somehow. I really hope he was right.

The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, with a foreword by David Olusoga, is published by Hodder & Stoughton (£9.99).

David Olusoga: ‘Black people were told that they had no history’

#David Olusoga: ‘Black people were told that they had no history’#David Olusoga#BBC#Blacks from england#Olaudah Equiano

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

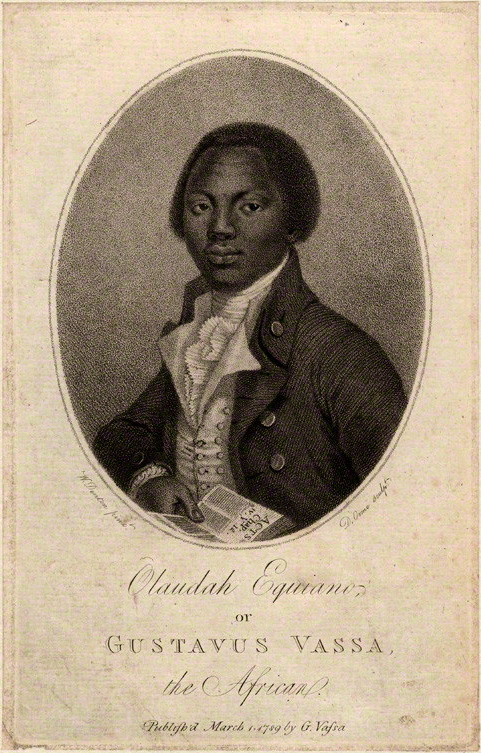

Olaudah Equiano (c. 1745–1797)

You may or may not know about Olaudah Equiano a.k.a. Gustavus Vassa, but this man was a key abolitionist, writer, and overall badass.

Olaudah Equiano was born in the Igbo region in modern Nigeria (some sources indicate that he was from South Carolina, but all seems to be circumstantial, so we’ll go with the info from his autobiography, so Nigeria it is), was enslaved as a child, taken to the Caribbean and sold to a captain of the Royal Navy who renamed him as Gustavus Vassa and with whom he traveled about 8 years. In 1766 he bought his own freedom from an English merchant by trading on his own and carefully saving money. He paid £40, that was about a whole year of a teacher’s salary. Thank god for Vassa’s financial literacy.

Later on he established in London and was part of an abolitionist group called the Sons of Africa (that is considered the first black political organisation in Britain), becoming very active in the 1780s anti-slave trade movement. He wrote his memoirs in 1789 under the title “The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano”, and this was the first book published by a black African writer in Europe. In it he describes the horrors of slavery: from he and his siblings being kidnapped, to the slave ships, and the treatment by white men. The book opens with a preface in which he frames this work as abolitionist literature, meaning that he was sharing all those horrible experiences for those in positions of authority could finally abolish slavery. His book was so successful that the second edition is from that very same year and made him wealthy thanks to the royalties, and it aided passage of the British Slave Trade Act of 1807.

In more personal details, he married Susannah Cullen in 1792, who was one of the subscribers that helped him publish his work (like crowdfunding, but 18th century style!), and he included his marriage as part of his autobiography since the 1792 edition forward. I just love that little detail.

Read more:

A selection from the second edition of “The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano”, from The British Library.

Learn more about him and other 18th century black anti-slavery activists at this site made for the 200th anniversary of the British Slave Trade Act.

The full book at Gutenberg.org

Images from top:

Portrait of Olaudah Equiano, 1789, by Daniel Orme, commissioned by Equiano himself.

Youssou N'Dour as Olaudah Equiano in the film Amazing Grace (2006)

Portrait of an African,ca. 1757-60, Allan Ramsay. This portrait is often used to illustrate new editions of Equiano’s book, but it is not him. It seems lately to be thought to be Igantius Sancho even though it is still not sure that it’s him either. BUT it’s a beautiful portrait, so here it is.

Google doodle for October 16th 2017, celebrating Olaudah Equiano’s 272nd Birthday.

#black history#18th century#Olaudah Equiano#gustavus vassa#joanna vassa#1780s#1790s#1750s#1760s#1770s#1789#The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano#slave trade#british abolition of the slave trade act#1800#1807#the british library#slavery

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Hitherto I had thought only slavery dreadful; but the state of a free negro appeared to me now equally so at least, and in some respects even worse, for they live in constant alarm for their liberty; and even this is but nominal, for they are universally insulted and plundered without the possibility of redress; for such is the equity of the West Indian laws, that no free negro's evidence will be admitted in their courts of justice. In this situation is it surprising that slaves, when mildly treated, should prefer even the misery of slavery to such a mockery of freedom? I was now completely disgusted with the West Indies, and thought I never should be entirely free until I had left them.

Olaudah Equiano, from The Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano

#Olaudah Equiano#The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano#slavery#tw#prose#historical survey of african american literature

1 note

·

View note

Text

What was Olaudah Equiano's real name?

What was Olaudah Equiano’s real name?

I’ll never forget my first black history month. In year eight, whilst learning about the transatlantic slave trade, our teacher introduces us to Olaudah Equiano. Describing him as the incredible Igbo-African man who bought his freedom, travelled worldwide, and contributed to the abolitionist movement to end slavery. Although the Equiano narrative made me feel proud, I couldn’t help but wonder why…

View On WordPress

#earliest voices olaudah equiano#equiano narrative#igbo#life of olaudah equiano#nigeria#Olaudah Equiano#the interesting narrative of olaudah equiano#What was Olaudah Equiano&039;s real name?#who is olaudah equiano

0 notes