#the guild of master craftsmen

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Maldon Road Garage, Colchester 2019

vintage fuel pumps, a Vauxhall 2-door, MGB 50-years anniversary poster, vintage Colman’s Mustard, Lamberts Teas and Brooke Bonn dividend Tea signs - spend wiseh, save wiseh

#MG MGB#vauxhall#maldon road garage#essex#colchester#colman's mustard#lamberts teas#brooke bonn#the guild of master craftsmen

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Growing flax to make linen was one of the oldest human activities in Europe, particularly in the Rhineland. Archeologists have found linen textiles among the settlements of Neolithic cultivators along the shores of Lake Neuchâtel in the Jura Mountains west of Bern, Switzerland. These were elaborate pieces: Stone Age clothmakers of the Swiss lakeshores sewed pierced fruit pits in a careful line into a fabric with woven stripes. The culture spread down the Rhine and into the lowland regions.

The Roman author Pliny observed in the first century AD that German women wove and wore linen sheets. By the ninth century flax had spread through Germany. By the sixteenth century, flax was produced in many parts of Europe, but the corridor from western Switzerland to the mouth of the Rhine contained the oldest region of large-scale commercial flax and linen production. In the late Middle Ages the linen of Germany was sold nearly everywhere in Europe, and Germany produced more linen than any other region in the world.

At this juncture, linen weavers became victims of an odd prejudice. “Better skinner than linen weaver,” ran one cryptic medieval German taunt. Another macabre popular saying had it that linen weavers were worse than those who “carried the ladders to the gallows.” The reason why linen weavers were slandered in this way, historians suspect, was that although linen weavers had professionalized and organized themselves into guilds, they had been unable to prevent homemade linen from getting onto the market. Guilds appeared across Europe between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries but many of the items they produced for exchange, like textiles and soap, were also produced at home right up through the nineteenth century. The intricate regulations of the guilds—determining who could join, how they would be trained, what goods they would produce, and how these could be exchanged—were mainly designed to distinguish guild work from this homely labor. That linen making continued to be carried out inside of households—a liability for guilds in general—lent a taint to the linen guild in particular.

In the seventeenth century, guilds came under pressure from a new, protocapitalist mode of production. Looking for cheaper cloth to sell on foreign markets, entrepreneurs cased the Central European countryside offering to pay cash to home producers for goods. Rural households became export manufacturing centers and a major source of competition with the guilds. These producers could undercut the prices of urban craftsmen because they could use the unregulated labor of their family members, and because their own agricultural production allowed them to sell their goods for less than their subsistence costs.

The uneasiness between guild and household production in the countryside erupted into open hostility. In the 1620s, linen guildsmen marched on villages, attacking competitors, and burning their looms. In February 1627 Zittau guild masters smashed looms and seized the yarn of home weavers in the villages of Oderwitz, Olbersdorf, and Herwigsdorf.

Guilds had long worked to keep homemade products from getting on the market. In their death throes, they hit upon a new and potent weapon: gender. Although women in medieval Europe wove at home for domestic consumption, many had also been guild artisans. Women were freely admitted as masters into

the earliest medieval guilds, and statutes from Silesia and the Oberlausitz show that women were master weavers. Thirteenth-century Paris had eighty mixed craft guilds of men and women and fifteen female-dominated guilds for such trades as gold thread, yarn, silk, and dress manufacturing. Up until the mid-seventeenth century, guilds had belittled home production because it was unregulated, nonprofessional, and competitive. In the mid-seventeenth century this work was identified as women’s work, and guildsmen unable to compete against cheaper household production tried to eject women from the market entirely. Single women were barred from independent participation in the guilds. Women were restricted to working as domestic servants, farmhands, spinners, knitters, embroiderers, hawkers, wet nurses. They lost ground even where the jobs had been traditionally their own, such as ale brewing and midwifery, by the end of the seventeenth century.

The wholesale ejection of women from the market during this period was achieved not only through guild statute, but through legal, literary, and cultural means. Throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries women lost the legal right to conduct economic activity as femes soles. In France they were declared legal “imbeciles,” and lost the right to make contracts or represent themselves in court. In Italy, they began to appear in court less frequently to denounce abuses against them. In Germany, when middle-class women were widowed it became customary to appoint a tutor to manage their affairs. As the medieval historian Martha Howell writes, “Comedies and satires of this period…often portrayed market women and trades women as shrews, with characterizations that not only ridiculed or scolded them for taking on roles in market production but frequently even charged them with sexual aggression.” This was a period rich in literature about the correction of errant women: Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew (1590–94), John Ford’s ’Tis Pity She’s a Whore (1629–33), Joseph Swetnam’s “The Araignment of Lewde, Idle, Froward, and Unconstant Women” (1615). Meanwhile, Protestant reformers and Counter-Reformation Catholics established doctrinally that women were inherently inferior to men.

This period, called the European Age of Reason, successfully banished women from the market and transformed them into the sweet and passive beings that emerged in Victorian literature. Women accused of being scolds were paraded in the streets wearing a new device called a “branks,” an iron muzzle that depressed the tongue. Prostitutes were subjected to fake drowning, whipped, and caged. Women convicted of adultery were sentenced to capital punishment.

As a cultural project, this was not merely recreational sadism. Rather, it was an ideological achievement that would have lasting and massive economic consequences. Political philosopher Silvia Federici has argued this expulsion was an intervention so massive, it ought to be included as one of a triptych of violent seizures, along with the Enclosure Acts and imperialism, that allowed capitalism to launch itself.

Part of why women resisted enclosure so fiercely was because they had the most to lose. The end of subsistence meant that households needed to rely on money rather than the production of agricultural goods like cloth, and women had successfully been excluded from ways to earn. As labor historian Alice Kessler-Harris has argued, “In pre-industrial societies, nearly everybody worked, and almost nobody worked for wages.” During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, monetary relations began to dominate economic life in Europe. Barred from most wage work just as the wage became essential, women were shunted into a position of chronic poverty and financial dependence. This was the dominant socioeconomic reality when the first modern factory, a cotton-spinning mill, opened in 1771 in Derbyshire, England, an event destined to upend still further the pattern of daily life."

- Sofi Thanhauser, Worn: A People's History of Clothing

#radical feminism#feminism#linen#history of clothing#sexism#female oppression#the rights they TOOK from us#i'm so pissed#i knew there would be misogyny in history of clothing#but this made my blood burn#Sofi Thanhauser

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

Troyan Pottery

Troyan Museum of National Crafts and Applied Arts

(19th century to the late 20th century)

Troyan, Bulgaria

There are three major schools of Bulgarian pottery (that have survived and are practiced in some form to this day) - pottery from Troyan, Veliko Tarnovo and Busintsi. The three styles of pottery are made using different techniques, forms and ornaments.

Troyan pottery is the most recognisable and widely practiced form of pottery in Bulgaria today.

One of the first mentions of a potter's guild in Troyan is from 1852. The craft developed rapidly following Bulgarian Liberation, with the first secondary school for pottery being founded in Troyan 1911. By the middle of the 20th century, the Troyan school of pottery takes shape. Its style is very distinctive and it incorporates old motifs while adapting them to contemporary tastes.

The photos above are from an exhibition titled The Wealth of Troyan Pottery which presents works from the 19th century to the 1970s. It includes works by some of the most famous masters of the craft - Dancho Vasileshki, Nikola Nikolski, Tsocho Kovachev, Bayu Dobrev and Petar Tsankov. It tells the story of the Iovkovi family, who were craftsmen who carried the art across four generations, and Iova Raevska - one of the most important masters who helped develop the art of ceramics in Bulgaria.

#Bulgaria#bulgarian pottery#Ceramics#Bulgarian ceramics#Eastern european ceramics#Eastern European pottery#The Bulgarian Pottery series

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

F.8.3 What other forms did state intervention in creating capitalism take?

Beyond being a paymaster for new forms of production and social relations as well as defending the owners’ power, the state intervened economically in other ways as well. As we noted in section B.2.5, the state played a key role in transforming the law codes of society in a capitalistic fashion, ignoring custom and common law when it was convenient to do so. Similarly, the use of tariffs and the granting of monopolies to companies played an important role in accumulating capital at the expense of working people, as did the breaking of unions and strikes by force.

However, one of the most blatant of these acts was the enclosure of common land. In Britain, by means of the Enclosure Acts, land that had been freely used by poor peasants was claimed by large landlords as private property. As socialist historian E.P. Thompson summarised, “the social violence of enclosure consisted … in the drastic, total imposition upon the village of capitalist property-definitions.” [The Making of the English Working Class, pp. 237–8] Property rights, which favoured the rich, replaced the use rights and free agreement that had governed peasants use of the commons. Unlike use rights, which rest in the individual, property rights require state intervention to create and maintain. “Parliament and law imposed capitalist definitions to exclusive property in land,” Thompson notes. This process involved ignoring the wishes of those who used the commons and repressing those who objected. Parliament was, of course, run by and for the rich who then simply “observed the rules which they themselves had made.” [Customs in Common, p. 163]

Unsurprisingly, many landowners would become rich through the enclosure of the commons, heaths and downland while many ordinary people had a centuries old right taken away. Land enclosure was a gigantic swindle on the part of large landowners. In the words of one English folk poem written in 1764 as a protest against enclosure:

They hang the man, and flog the woman, That steals the goose from off the common; But let the greater villain loose, That steals the common from the goose.

It should be remembered that the process of enclosure was not limited to just the period of the industrial revolution. As Colin Ward notes, “in Tudor times, a wave of enclosures by land-owners who sought to profit from the high price of wool had deprived the commoners of their livelihood and obliged them to seek work elsewhere or become vagrants or squatters on the wastes on the edges of villages.” [Cotters and Squatters, p. 30] This first wave increased the size of the rural proletariat who sold their labour to landlords. Nor should we forget that this imposition of capitalist property rights did not imply that it was illegal. As Michael Perelman notes, "[f]ormally, this dispossession was perfectly legal. After all, the peasants did not have property rights in the narrow sense. They only had traditional rights. As markets evolved, first land-hungry gentry and later the bourgeoisie used the state to create a legal structure to abrogate these traditional rights.” [The Invention of Capitalism, pp. 13–4]

While technically legal as the landlords made the law, the impact of this stealing of the land should not be under estimated. Without land, you cannot live and have to sell your liberty to others. This places those with capital at an advantage, which will tend to increase, rather than decrease, the inequalities in society (and so place the landless workers at an increasing disadvantage over time). This process can be seen from early stages of capitalism. With the enclosure of the land an agricultural workforce was created which had to travel where the work was. This influx of landless ex-peasants into the towns ensured that the traditional guild system crumbled and was transformed into capitalistic industry with bosses and wage slaves rather than master craftsmen and their journeymen. Hence the enclosure of land played a key role, for “it is clear that economic inequalities are unlikely to create a division of society into an employing master class and a subject wage-earning class, unless access to the means of production, including land, is by some means or another barred to a substantial section of the community.” [Maurice Dobb, Studies in Capitalist Development, p. 253]

The importance of access to land is summarised by this limerick by the followers of Henry George (a 19th century writer who argued for a “single tax” and the nationalisation of land). The Georgites got their basic argument on the importance of land down these few, excellent, lines:

A college economist planned To live without access to land He would have succeeded But found that he needed Food, shelter and somewhere to stand.

Thus anarchists concern over the “land monopoly” of which the Enclosure Acts were but one part. The land monopoly, to use Tucker’s words, “consists in the enforcement by government of land titles which do not rest upon personal occupancy and cultivation.” [The Anarchist Reader, p. 150] So it should be remembered that common land did not include the large holdings of members of the feudal aristocracy and other landlords. This helped to artificially limit available land and produce a rural proletariat just as much as enclosures.

It is important to remember that wage labour first developed on the land and it was the protection of land titles of landlords and nobility, combined with enclosure, that meant people could not just work their own land. The pressing economic circumstances created by enclosing the land and enforcing property rights to large estates ensured that capitalists did not have to point a gun at people’s heads to get them to work long hours in authoritarian, dehumanising conditions. In such circumstances, when the majority are dispossessed and face the threat of starvation, poverty, homelessness and so on, “initiation of force” is not required. But guns were required to enforce the system of private property that created the labour market in the first place, to enclosure common land and protect the estates of the nobility and wealthy.

By decreasing the availability of land for rural people, the enclosures destroyed working-class independence. Through these Acts, innumerable peasants were excluded from access to their former means of livelihood, forcing them to seek work from landlords or to migrate to the cities to seek work in the newly emerging factories of the budding industrial capitalists who were thus provided with a ready source of cheap labour. The capitalists, of course, did not describe the results this way, but attempted to obfuscate the issue with their usual rhetoric about civilisation and progress. Thus John Bellers, a 17th-century supporter of enclosures, claimed that commons were “a hindrance to Industry, and … Nurseries of Idleness and Insolence.” The “forests and great Commons make the Poor that are upon them too much like the indians.” [quoted by Thompson, Op. Cit., p. 165] Elsewhere Thompson argues that the commons “were now seen as a dangerous centre of indiscipline … Ideology was added to self-interest. It became a matter of public-spirited policy for gentlemen to remove cottagers from the commons, reduce his labourers to dependence.” [The Making of the English Working Class, pp. 242–3] David McNally confirms this, arguing “it was precisely these elements of material and spiritual independence that many of the most outspoken advocates of enclosure sought to destroy.” Eighteenth-century proponents of enclosure “were remarkably forthright in this respect. Common rights and access to common lands, they argued, allowed a degree of social and economic independence, and thereby produced a lazy, dissolute mass of rural poor who eschewed honest labour and church attendance … Denying such people common lands and common rights would force them to conform to the harsh discipline imposed by the market in labour.” [Against the Market, p. 19]

The commons gave working-class people a degree of independence which allowed them to be “insolent” to their betters. This had to be stopped, as it undermined to the very roots of authority relationships within society. The commons increased freedom for ordinary people and made them less willing to follow orders and accept wage labour. The reference to “Indians” is important, as the independence and freedom of Native Americans is well documented. The common feature of both cultures was communal ownership of the means of production and free access to it (usufruct). This is discussed further in section I.7 (Won’t Libertarian Socialism destroy individuality?). As Bookchin stressed, the factory “was not born from a need to integrate labour with modern machinery,” rather it was to regulate labour and make it regular. For the “irregularity, or ‘naturalness,’ in the rhythm and intensity of traditional systems of work contributed more towards the bourgeoisie’s craze for social control and its savagely anti-naturalistic outlook than did the prices or earnings demanded by its employees. More than any single technical factor, this irregularity led to the rationalisation of labour under a single ensemble of rule, to a discipline of work and regulation of time that yielded the modern factory … the initial goal of the factory was to dominate labour and destroy the worker’s independence from capital.” [The Ecology of Freedom p. 406]

Hence the pressing need to break the workers’ ties with the land and so the “loss of this independence included the loss of the worker’s contact with food cultivation … To live in a cottage … often meant to cultivate a family garden, possibly to pasture a cow, to prepare one’s own bread, and to have the skills for keeping a home in good repair. To utterly erase these skills and means of a livelihood from the worker’s life became an industrial imperative.” Thus the worker’s “complete dependence on the factory and on an industrial labour market was a compelling precondition for the triumph of industrial society … The need to destroy whatever independent means of life the worker could garner … all involved the issue of reducing the proletariat to a condition of total powerlessness in the face of capital. And with that powerlessness came a supineness, a loss of character and community, and a decline in moral fibre.” [Bookchin, Op. Cit.,, pp. 406–7] Unsurprisingly, there was a positive association between enclosure and migration out of villages and a “definite correlation … between the extent of enclosure and reliance on poor rates … parliamentary enclosure resulted in out-migration and a higher level of pauperisation.” Moreover, “the standard of living was generally much higher in those areas where labourer managed to combine industrial work with farming … Access to commons meant that labourers could graze animals, gather wood, stones and gravel, dig coal, hunt and fish. These rights often made the difference between subsistence and abject poverty.” [David McNally, Op. Cit., p. 14 and p. 18] Game laws also ensured that the peasantry and servants could not legally hunt for food as from the time of Richard II (1389) to 1831, no person could kill game unless qualified by estate or social standing.

The enclosure of the commons (in whatever form it took — see section F.8.5 for the US equivalent) solved both problems — the high cost of labour, and the freedom and dignity of the worker. The enclosures perfectly illustrate the principle that capitalism requires a state to ensure that the majority of people do not have free access to any means of livelihood and so must sell themselves to capitalists in order to survive. There is no doubt that if the state had “left alone” the European peasantry, allowing them to continue their collective farming practices (“collective farming” because, as Kropotkin shows, the peasants not only shared the land but much of the farm labour as well), capitalism could not have taken hold (see Mutual Aid for more on the European enclosures [pp. 184–189]). As Kropotkin notes, ”[i]nstances of commoners themselves dividing their lands were rare, everywhere the State coerced them to enforce the division, or simply favoured the private appropriation of their lands” by the nobles and wealthy. Thus “to speak of the natural death of the village community [or the commons] in virtue of economical law is as grim a joke as to speak of the natural death of soldiers slaughtered on a battlefield.” [Mutual Aid, p. 188 and p. 189]

Once a labour market was created by means of enclosure and the land monopoly, the state did not passively let it work. When market conditions favoured the working class, the state took heed of the calls of landlords and capitalists and intervened to restore the “natural” order. The state actively used the law to lower wages and ban unions of workers for centuries. In Britain, for example, after the Black Death there was a “servant” shortage. Rather than allow the market to work its magic, the landlords turned to the state and the result was “the Statute of Labourers” of 1351:

“Whereas late against the malice of servants, which were idle, and not willing to serve after the pestilence, without taking excessive wages, it was ordained by our lord the king … that such manner of servants … should be bound to serve, receiving salary and wages, accustomed in places where they ought to serve in the twentieth year of the reign of the king that now is, or five or six years before; and that the same servants refusing to serve in such manner should be punished by imprisonment of their bodies … now forasmuch as it is given the king to understand in this present parliament, by the petition of the commonalty, that the said servants having no regard to the said ordinance, .. to the great damage of the great men, and impoverishing of all the said commonalty, whereof the said commonalty prayeth remedy: wherefore in the said parliament, by the assent of the said prelates, earls, barons, and other great men, and of the same commonalty there assembled, to refrain the malice of the said servants, be ordained and established the things underwritten.”

Thus state action was required because labourers had increased bargaining power and commanded higher wages which, in turn, led to inflation throughout the economy. In other words, an early version of the NAIRU (see section C.9). In one form or another this statute remained in force right through to the 19th century (later versions made it illegal for employees to “conspire” to fix wages, i.e., to organise to demand wage increases). Such measures were particularly sought when the labour market occasionally favoured the working class. For example, ”[a]fter the Restoration [of the English Monarchy],” noted Dobb, “when labour-scarcity had again become a serious complaint and the propertied class had been soundly frightened by the insubordination of the Commonwealth years, the clamour for legislative interference to keep wages low, to drive the poor into employment and to extend the system of workhouses and ‘houses of correction’ and the farming out of paupers once more reached a crescendo.” The same occurred on Continental Europe. [Op. Cit., p. 234]

So, time and again employers called on the state to provide force to suppress the working class, artificially lower wages and bolster their economic power and authority. While such legislation was often difficult to enforce and often ineffectual in that real wages did, over time, increase, the threat and use of state coercion would ensure that they did not increase as fast as they may otherwise have done. Similarly, the use of courts and troops to break unions and strikes helped the process of capital accumulation immensely. Then there were the various laws used to control the free movement of workers. “For centuries,” notes Colin Ward, “the lives of the poor majority in rural England were dominated by the Poor law and its ramifications, like the Settlement Act of 1697 which debarred strangers from entering a parish unless they had a Settlement Certificate in which their home parish agreed to take them back if they became in need of poor relief. Like the Workhouse, it was a hated institution that lasted into the 20th century.” [Op. Cit., p. 31]

As Kropotkin stressed, “it was the State which undertook to settle .. . griefs” between workers and bosses “so as to guarantee a ‘convenient’ livelihood” (convenient for the masters, of course). It also acted “severely to prohibit all combinations … under the menace of severe punishments … Both in the town and in the village the State reigned over loose aggregations of individuals, and was ready to prevent by the most stringent measures the reconstitution of any sort of separate unions among them.” Workers who formed unions “were prosecuted wholesale under the Master and Servant Act — workers being summarily arrested and condemned upon a mere complaint of misbehaviour lodged by the master. Strikes were suppressed in an autocratic way … to say nothing of the military suppression of strike riots … To practice mutual support under such circumstances was anything but an easy task … After a long fight, which lasted over a hundred years, the right of combing together was conquered.” [Mutual Aid, p. 210 and p. 211] It took until 1813 until the laws regulating wages were repealed while the laws against combinations remained until 1825 (although that did not stop the Tolpuddle Martyrs being convicted of “administering an illegal oath” and deported to Tasmania in 1834). Fifty years later, the provisions of the statues of labourers which made it a civil action if the boss broke his contract but a criminal action if the worker broke it were repealed. Trade unions were given legal recognition in 1871 while, at the same time, another law limited what the workers could do in a strike or lockout. The British ideals of free trade never included freedom to organise.

(Luckily, by then, economists were at hand to explain to the workers that organising to demand higher wages was against their own self-interest. By a strange coincidence, all those laws against unions had actually helped the working class by enforcing the necessary conditions for perfect competition in labour market! What are the chances of that? Of course, while considered undesirable from the perspective of mainstream economists — and, by strange co-incidence, the bosses — unions are generally not banned these days but rather heavily regulated. The freedom loving, deregulating Thatcherites passed six Employment Acts between 1980 and 1993 restricting industrial action by requiring pre-strike ballots, outlawing secondary action, restricting picketing and giving employers the right to seek injunctions where there is doubt about the legality of action — in the workers’ interest, of course as, for some reason, politicians, bosses and economists have always known what best for trade unionists rather than the trade unionists themselves. And if they objected, well, that was what the state was for.)

So to anyone remotely familiar with working class history the notion that there could be an economic theory which ignores power relations between bosses and workers is a particularly self-serving joke. Economic relations always have a power element, even if only to protect the property and power of the wealthy — the Invisible Hand always counts on a very visible Iron Fist when required. As Kropotkin memorably put it, the rise of capitalism has always seen the State “tighten the screw for the worker” and “impos[ing] industrial serfdom.” So what the bourgeoisie “swept away as harmful to industry” was anything considered as “useless and harmful” but that class “was at pains not to sweep away was the power of the State over industry, over the factory serf.” Nor should the role of public schooling be overlooked, within which “the spirit of voluntary servitude was always cleverly cultivated in the minds of the young, and still is, in order to perpetuate the subjection of the individual to the State.” [The State: Its Historic Role, pp. 52–3 and p. 55] Such education also ensured that children become used to the obedience and boredom required for wage slavery.

Like the more recent case of fascist Chile, “free market” capitalism was imposed on the majority of society by an elite using the authoritarian state. This was recognised by Adam Smith when he opposed state intervention in The Wealth of Nations. In Smith’s day, the government was openly and unashamedly an instrument of wealth owners. Less than 10 per cent of British men (and no women) had the right to vote. When Smith opposed state interference, he was opposing the imposition of wealth owners’ interests on everybody else (and, of course, how “liberal”, never mind “libertarian”, is a political system in which the many follow the rules and laws set-down in the so-called interests of all by the few? As history shows, any minority given, or who take, such power will abuse it in their own interests). Today, the situation is reversed, with neo-liberals and right-“libertarians” opposing state interference in the economy (e.g. regulation of Big Business) so as to prevent the public from having even a minor impact on the power or interests of the elite. The fact that “free market” capitalism always requires introduction by an authoritarian state should make all honest “Libertarians” ask: How “free” is the “free market”?

#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#mutual aid#cops#police

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Skyhold Conversation

Bonny Sims

Skyhold Masterpost

Bonny Sims: [Lord/Lady] Inquisitor. Bonny Sims, at your service. I trust good Seggrit was not too coarse? Now that you’ve come to some good fortune, you deserve an upgrade. As master of The Tradesmen, I stand ready to supply your every need.

1 - Dialogue options:

General: “The Tradesmen”? [2]

General: How is business? [3]

General (not all keeps claimed): How can I bring in commerce? [4]

General: Goodbye. [5]

2 - General: “The Tradesmen”? PC: Who or what are “The Tradesmen”?

First time asking Bonny Sims: A following of sympathetic and profit-minded individuals who promote local craftsmen and fair importers. A guild of sorts, although that implies Carta affiliations we are not interested in… crossing.

Bonny Sims (dwarf PC): No offence. Sincerely. We are merely organized merchants at your service. [6]

If asked before Bonny Sims: Our purpose in the Inquisition is legitimate and honorable. You will have what you need at honest prices. [6]

6 - Dialogue options:

General (Seggrit alive): Where is Seggrit? [7]

General (Seggrit died): Sorry about Seggrit dying. [8]

General: What can you do for me? [9]

General: You’re master of your group? [10]

General: Goodbye. [11]

7 - General: Where is Seggrit? PC: Seggrit survived Haven. Where is he? Bonny Sims: About. Doing good work for you and yours. But this position is now more desirable. It was time arrangements were made. I shall make every effort to prove that this is an upgrade. [back to 6] ㅤㅤ ㅤ 8 - General: Sorry about Seggrit dying. PC: It’s a shame Seggrit didn’t survive Haven. Bonny Sims: It is. But one must continue. PC: That’s it? Bonny Sims: He was a shrewd man, but he was none too pleasant. It was time arrangements were made. I shall make every effort to prove that this is an upgrade. [back to 6] ㅤㅤ ㅤ 9 - General: What can you do for me? PC: What do you bring to the Inquisition? Bonny Sims: What you need. And more. It takes great coordination to make a remote location seem… central. ㅤㅤ ㅤ Completed War Table: Opening the Roads Bonny Sims: Many now make the journey to Skyhold. We will ensure they continue to see the benefit. [back to 6] ㅤㅤ ㅤ Have not completed “Opening the Roads” Bonny Sims: While there is no doubt the boutiques of Val Royeaux display the grandest of the grand, they do not travel. At least, not yet. [back to 6] ㅤㅤ ㅤ 10 - General: You’re master of your group? PC: Why are you a mere merchant if you’re the master of this group? Bonny Sims: I wish to avoid the suggestion that I am a posturing commander atop a structure of malcontents. It is better to remain active. Hands on. Do you not agree, Inquisitor? [back to 6]

3 - General: How is business? PC: How are you doing? Good business?

Skyhold not repaired Bonny Sims: It is a struggle, but one worth having. Potential is the most valuable resource. [back to 1]

First set of repairs (leaving and returning to Skyhold) Bonny Sims: Building. Always building. Thanks to you. [back to 1]

Final set of repairs (completing HLtA or WEWH) Bonny Sims: In this gilded fortress? How could we not be? [back to 1]

4 - General: How can I bring in commerce? PC: Skyhold needs a healthy flow of goods. How can I help?

No keeps claimed Bonny Sims: Free the trade routes of obstruction, restore security to the outposts—the keeps—and merchants will find you. [back to 1]

One keep claimed One of the major hubs is freed. Continue on this path, and you're on your way. [back to 1]

Two keeps claimed You've cleared two of the major hubs and restored trade to many. [back to 1]

5 - General: Goodbye. Inquisitor: We’ll speak another time. Bonny Sims: Certainly, [Lord/Lady] Inquisitor.

—

If spoken to after all keeps are claimed Bonny Sims: My [lord/lady] Inquisitor. How gratifying to see you. Your efforts to restore our hubs of commerce have been tremendous. As is the gratitude of The Tradesmen and affiliates.

Bonny Sims: An opportunity, Your Worship. If you've a moment, I would speak to you about a potential partnership.

Dialogue options:

General: You mentioned an opportunity?

PC: You said something about a partnership?

Bonny Sims: The work you've done has presented an opportunity to return trade to the roads. A minimal investment at key points will ensure safe caravans. I'll forward it to your assistants for consideration. We have this opportunity because of you, Inquisitor. And we will all profit.

Activates War Table: Opening the Roads

Upon completion Bonny Sims: All manner of new friends are arriving now that you’ve opened us to merchants of the road. The influx of character is refreshing. I look forward to doing business with all of them.

If spoken to after completing Opening the Roads, HLtA, and WEWH, and unlocking the Short List perk Bonny Sims: A unique issue has arisen, Inquisitor. I pass it to you.

Activates War Table: Not So Bonny Sims

Upon completion Bonny Sims: Of course you resolved the issue, Inquisitor. Well done.

#dragon age inquisition#dragon age#dai#dai transcripts#dai dialogue#dragon age transcripts#dragon age dialogue#dragon age inquisition transcripts#dragon age inquisition dialogue#long post#skyhold#bonny sims

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

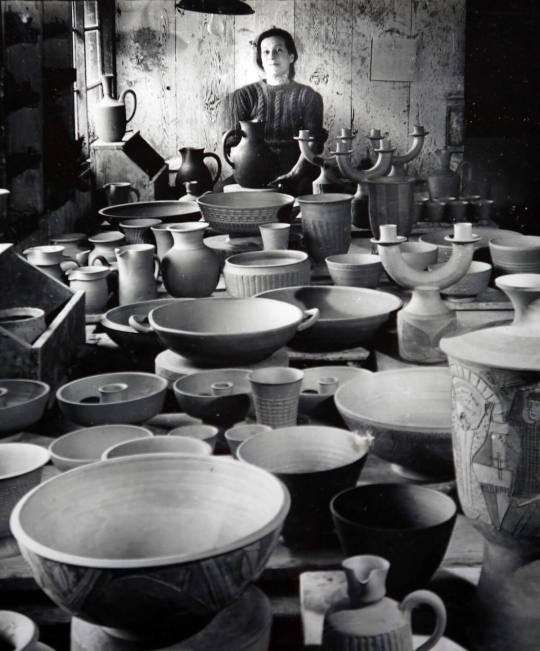

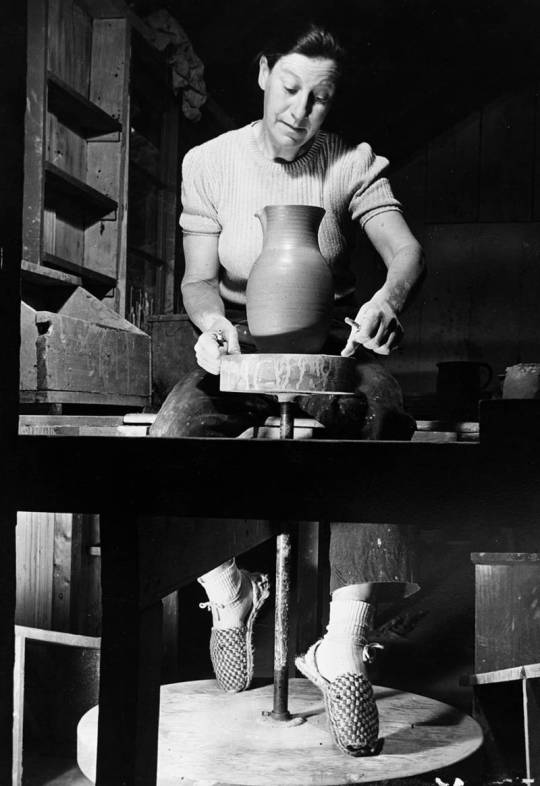

A LOOK AT "THE MASTER IN THE REDWOODS" -- A GERMAN-AMERICAN MASTER POTTER AND HER WORKS.

PIC(S) INFO: Spotlight on Marguerite Wildenhain (born Marguerite Friedlaender), (October 11, 1896 – February 24, 1985), an American Bauhaus-trained ceramic artist, educator and author, photographed at Pond Farm, Sonoma County, CA, c. early 1950s. Plus assorted pottery works by the late, great Marguerite herself.

OVERVIEW: "Another potter whose career exemplifies the international nature of studio pottery is Marguerite Wildenhain (1896 – 1985). She was born in France, to a British mother and a German Jewish father. At age 18, she started work in a porcelain factory, and fell in love with the wheel. One day in 1919, while riding her bike in the countryside, Marguerite happened upon a poster announcing a new school, to be called the Bauhaus. It would be "a new guild of craftsmen without the class distinctions which raise an arrogant barrier between craftsmen and artists." At the Bauhaus, Wildenhain worked with some of the greatest designers of the early 20th century; in 1925, she became the first woman honored as a German Master Potter. She went on to teach at the Burg Giebichenstein University of Art and Design, while also designing commercial ceramics. When the Nazis came into power, Wildenhain and her husband fled to the Netherlands, where they opened a pottery they called shop called Het Kruikje (“The Little Jug”). In 1940 she had to flee the Nazis yet again, this time to emigrating to the United States

PART II: Wildenhain briefly took a position at the California College of Arts and Crafts, then in 1942, relocated to the new Pond Farm artist’s colony in rural Sonoma County. High on a hill above the Russian River, she planted a garden, built a house, and repurposed an old barn into her pottery studio. Over the next 40 years, Wildenhain would create an extraordinary body of work here, while also teaching students from around the world. Her students learned to throw on the physically-demanding kick-wheel, and started by making a dog dish! In between sessions, they discussed philosophy, natural history, and how to run a business; many went on to become important potters in their own right. Now part of the Austin Creek State Recreation Area, Wildenhain’s studio has been designated a "National Treasure" by the National Trust for Historic Preservation."

-- HAND OR EYE, "What is Studio Pottery?," written by Martin Holden

Source: www.sfomuseum.org/exhibitions/potters-life-marguerite-wildenhain-pond-farm, https://handoreye.com/journal/studiopottery, X, Pinterest, various, etc...

#Marguerite Wildenhain#Bauhaus-trained#Master Potter#Potter#Pottery#Ceramic#Bauhaus School#German Master Potter#Marguerite Friedlaender#Fifties#50s#Photography#1950s#Pottery Design#Ceramics#Pond Farm#Sonoma County#Pond Farm California#Pond Farm CA#Northern California#NorCal#Sonoma

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

As a gift for my mom, I knitted the "Sheepish Look" tea cozy from the book Tea Cozies by the Guild of Master Craftsmen.

Knitted with Schoeller + Stahl Soft Touch yarn and 4 mm needles.

Note: the original pattern stitches the eyes in with satin stitch, I changed that and used a pair of old shirt buttons.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Building a Fabula World, Part 2c

Right, so. Got distracted, forgot what I was doing here. But the world building information must continue, so here we go.

Last time I wrote about the theocratic nation of The Zlota Sovereignty and the lightly comedic city of craftsmen and Switzerland-esque neutrality called Sentoki, The City of Guilds. This time around we've got a couple more:

The Pangolarian Clans- Provided by Richard

Less a nation and more a loose organization of clans that dwell beneath the earth, the Pangolarian Clans are simultaneously a political entity and a unique species of Demihuman. These squat beings with clawed fingers and toes and scaled bodies (yes they are just pangolin people) have built an extensive network of burrows and under-ways that span the length and breadth of the continent. It is there, in their subterranean dominion, that the Pangolarians mine ores, precious metals, and gems from beneath the earth that they then trade for foodstuffs and products of the surface dwellers that they need to support their society. But this trade occurs only on their terms, and only at specific trading outposts built by the clans on the surface. Rarely are surface dwellers ever allowed into the depths.

The clans are somewhat xenophobic towards outsiders and have a tradition of militancy and martial prowess. Encroachment into their territory is met swiftly by the Phalanx, which is a militia force that be raised at a moment's notice if the need is great enough. Direct familial relationships are generally superseded by a culturally instilled loyalty to the Platoon into which you are born, and the hierarchy that comes with it. Every Pangolarian is part of the army, and the army serves to protect all Pangolarians. Still, it is not entirely beyond imagining to see a member of the clans on the surface. Many crimes against the Clans are punished by exile to the surface, rather than by a death sentence, and young Pangolarians are encouraged to take a pilgrimage out into the wider world when they first reach the age of maturity so that they might decide for themselves if they wish to return to their Platoon or strike out on their own.

For Classes we decided to stick close to the somewhat rebranded dwarf tropes, declaring that the Pangolarians should have a higher than average number of Guardians, Weapon Masters, and Commanders while also having a lower than average tendency towards explicitly magical class archetypes.

The Immarian Empire - Provided by Brady

The Immarian Empire is an ancient kingdom that once held sway over a huge swathe of the continent through their mastery of esoteric magic and astrological understanding of the universe. Evidence of the presence can still be found in the form of crumbling outpost ruins, or the very foundations up which modern cities are built. Theirs was a civilization built on Geomancy and a respect for the natural order, though one in which they harnessed the natural order like a tool... or perhaps an unruly pet.

Unfortunately for the empire, the natural order is not so easily controlled, and due to shifts in the leylines that span the continent, their culture has been forced to contract back in on itself, retreating to their capital and most closely guarded cities which occupy a small archipelago just off the coast. Now they find their position in the world challenged by the advent of the magical industrial revolution. Tension exists between this empire and The Alumen Dominion because The Dominion claims that they are the natural inheritors of the seat of power that The Immarians vacated. Even while The Dominion pays lip service to their former rulers as their driving inspiration, it is clear they have no intention to actually restore the decaying empire to its former state of glory.

For now the Immarian Empire remains quiet, cloistered away in their carefully planned cities, which visually evoke the depictions of what the Aztec or Maya might have looked like at the height of their power. They have become like Militant librarians, keepers of old knowledge. If they can no longer rule, then they will at least attempt to insure that no knowledge is lost to the world.

For classes, we decided that the Empire should definitely be really high in magical potential. Elementalists, Envokers, and Entropists all easily fit into this particular kingdom.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

i’m finally getting to those tav asks. thanks everyone who sent one!! the lovely @dragonologist-phd asked for #1, which includes birthplace & family, and i Got To Thinking in too much detail, much too much detail by far, too detailed, so here’s a separate post for just those elements.

jove grew up in baldur’s gate. they did have a clan, but it wasn’t a biological family unit—it was an all dragonborn craftsmen’s guild! most members were copper, brass, red or gold dragonborn who used their fire or acid breath to manipulate metal and glass. jove wasn’t born with that skill. their mother was a vagabond blue dragonborn, and although jove inherited their father’s brassy scales, they also manifested their mother’s electrical breath type, which wasn’t of any use in metalworking. the clan was warm to insiders but highly competitive and proud of their handiwork, and judged members’ worth almost solely by what they could craft. jove knew they’d be fed and cared for, but only tolerated, unless they excelled at a trade.

as a teenager, jove struck up a friendship with ritika estis, a much older gold dwarf metallurgist from a rival crafting guild. estis taught jove how to use a dwarven forge to work with metal, glass, and jewels using tools instead of relying on naturally heatproof hands and melting breath. estis was tough on jove, working them hard and giving praise sparingly, but every compliment meant the world to the young dragonborn. she built up their confidence to apply for a jeweler’s apprenticeship with their clan.

but estis also noticed that despite their dogged devotion to learning their father’s trade, jove was much more moved by folk songs and carved wood than any bauble made for a baldurian noble. jewelrymaking made them focus and sweat; music made them tap their foot, twitch their tail, and part their lips to try to taste it. it was a different kind of love. the day jove won their jeweling apprenticeship, estis went to them and, in a rare moment of open encouragement, urged them to forget the forge and learn to make music and instruments instead.

jove took up a secret, second apprenticeship with a human master luthier, learning to craft and repair string instruments and, tentatively, how to play the fiddle with their big, clawed hands. when the clan found out, jove was pressured to choose one trade and master it, instead of burning themself out to fail at both. with the self-assurance they’d learned from estis, jove committed to making instruments. many of their older clanmates were deeply embittered toward ritika and her guild for molding a promising young metalworker just to turn them against the family trade, but jove was happy.

after years of practice under the luthier, jove achieved the rank of journeyman and started to make gold for their clan selling handcrafted string instruments and repair services. they were much better at working on instruments than playing them, but had achieved enough skill on the fiddle to play gigs at local taverns and make passersby smile at them on festival days. they were more than content, and would have lived happily as an amateur musician and aspiring master luthier in the gate for the rest of their days.

and then came the bar fight.

fights weren’t that unusual for the cheaper inns and alehouses jove played music at, but this particular brawl started with a human woman harrassing a tiefling bachelor party, talking loudly about how they brought crime and sour luck on baldur’s gate, and shouldn’t be allowed to marry lest their offspring overrun the city. when she implied they killed and ate human children, one of the prouder and drunker tieflings took a swing at the woman. she reacted as though she’d been attacked, unprovoked, by the whole party, and other non-tieflings sprung to her defense. within seconds, the taproom turned into a battlefield, and within minutes all the celebrating tieflings were senseless on the floor. when the guards arrived, it was the tieflings who were arrested for disturbing the peace.

jove watched the whole thing, their bow sliding uselessly off the strings, unsure what they could do short of belching out a cone of lightning that would hit attackers, tieflings, and bystanders indiscriminately—so they did nothing.

when they told their master what happened, he was unsympathetic to the tieflings, saying that the other humans had taken things too far but that they hadn’t been wrong about the “foulbloods.”

jove got up before sunrise, stole their favorite of the violins they’d crafted and a simple glaive from estis’s forge (she would have given it freely if they’d woken her to ask, but jove couldn’t risk talking to her—if estis was as callous about the tieflings as their other mentor had been, it would break their faith completely), and left baldur’s gate. they’ve been roving the sword coast ever since, a vagabond like their mother, determined to protect strangers’ right to live and celebrate life loudly, especially those from “monstrous” races. this became the foundation of their paladin’s oath.

they’ve gotten rusty on the fiddle. but on the night of celebrating peace between the druids and tieflings, they’re compelled to play again.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Was it the lucky socks I wore? Maybe, but, from now on, I'm happy to say, I can call myself a master artisan. This afternoon I was judged by the Haverford chapter on standards held by the PA Guild of Craftsmen and I passed! Thank you everyone for encouraging me to keep striving for quality work in my designs. #sleepycatjewelry #paguildofcraftsmen #silversmith #metalsmith #jewelryartist #jewelrydesigner #ooakjewelry #opthandmade https://www.instagram.com/p/Cpa2Qp0ujci/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#sleepycatjewelry#paguildofcraftsmen#silversmith#metalsmith#jewelryartist#jewelrydesigner#ooakjewelry#opthandmade

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Understanding the Significance of Masonic Chain Collars in Freemasonry

Freemasonry, a fraternal organization with deep historical roots, is known for its rich traditions, rituals, and symbols. Among the many symbols that hold significant meaning in Freemasonry are the Masonic chain collars. These ornate and often elaborate collars are not merely decorative; they carry profound symbolism and serve important functions within the Masonic Lodge. In this article, we will delve into the history, symbolism, and significance of Masonic chain collars, exploring their role in the rituals and ceremonies of Freemasonry.

The Historical Roots of Masonic Chain Collars

Origins of Freemasonry

To understand the significance of Masonic chain collars, it's essential first to appreciate the origins of Freemasonry itself. Freemasonry traces its roots back to the medieval stonemason guilds of Europe. These guilds were composed of skilled craftsmen who built the great cathedrals, castles, and other monumental structures of the time. Over the centuries, these guilds evolved into a fraternal organization, emphasizing moral and ethical teachings, self-improvement, and mutual support.

Evolution of Masonic Regalia

As Freemasonry evolved, so did its symbols and regalia. The use of ceremonial attire, including aprons, jewels, and collars, became a way to distinguish rank and office within the Lodge. Masonic chain collars, in particular, began to emerge as an essential part of this regalia in the 18th century. These collars were designed to be worn by officers of the Lodge, symbolizing their authority and responsibilities.

The Symbolism of Masonic Chain Collars

The Chain as a Symbol

The chain, as a symbol, carries deep meaning in various cultures and traditions. In Freemasonry, the Masonic chain collar symbolizes the interconnectedness of all members of the Lodge. Just as a chain is composed of individual links, each member of the Lodge is connected to one another, forming a strong bond of brotherhood. This symbolism underscores the Masonic principles of unity, fraternity, and mutual support.

The Collar as a Sign of Office

Masonic chain collars are not merely ornamental; they serve as a sign of office within the Lodge. Each collar is typically adorned with a jewel or emblem representing the specific office held by the wearer. For example, the Worshipful Master's collar may feature a square, symbolizing moral rectitude and fairness, while the Senior Warden's collar might bear the level, representing equality. These symbols serve as a constant reminder of the duties and responsibilities that come with each office.

The Use of Precious Metals

The materials used in the construction of Masonic chain collars also carry symbolic significance. Many collars are made from precious metals such as gold or silver, representing the enduring value of the principles upheld by Freemasonry. The use of these materials also signifies the esteem in which the office and its duties are held within the Lodge.

The Role of Masonic Chain Collars in Rituals and Ceremonies

The Installation of Officers

One of the most important ceremonies in a Masonic Lodge is the installation of officers. During this ceremony, the outgoing officers formally pass their responsibilities to the newly elected officers. Masonic chain collars play a central role in this ritual, as each officer is invested with their collar and jewel, symbolizing the transfer of authority. This ceremony emphasizes the continuity of leadership within the Lodge and the ongoing commitment to the principles of Freemasonry.

Degree Work and Masonic Rituals

Masonic chain collars are also worn during degree work and other Masonic rituals. Each degree in Freemasonry involves specific teachings and symbols, and the officers conducting these rituals wear their collars as a sign of their authority to lead the proceedings. The presence of the collars reinforces the solemnity and significance of the rituals, reminding all present of the profound lessons being imparted.

Public and Private Ceremonies

In addition to their role in private Lodge ceremonies, Masonic chain collars are often worn during public events and parades. When Masons participate in public ceremonies, such as cornerstone layings or memorial services, the officers don their collars as a sign of their office and the Masonic values they represent. This public display of Masonic regalia serves to reinforce the fraternity's commitment to its principles and its role in the broader community.

The Design and Craftsmanship of Masonic Chain Collars

Traditional vs. Modern Designs

Masonic chain collars come in a wide variety of designs, ranging from traditional to modern. Traditional designs often feature intricate links and elaborate jewels, reflecting the craftsmanship and attention to detail that is a hallmark of Masonic regalia. Modern designs, while sometimes simpler, still retain the essential elements of symbolism and dignity that define Masonic collars.

Customization and Personalization

Many Lodges choose to customize their chain collars, incorporating specific symbols or motifs that are significant to their members. This customization allows each Lodge to express its unique identity while maintaining the universal symbols of Freemasonry. The personalization of collars also serves as a reminder of the individual contributions of each member to the collective work of the Lodge.

The Role of Artisans and Jewelers

The creation of Masonic chain collars is a specialized craft, often carried out by skilled artisans and jewelers. These craftsmen use traditional techniques to create collars that are both beautiful and meaningful. The quality of craftsmanship in a Masonic collar is a reflection of the esteem in which the office and its responsibilities are held.

The Importance of Masonic Chain Collars in Today's Freemasonry

Upholding Tradition

In an ever-changing world, Masonic chain collars serve as a tangible link to the traditions and history of Freemasonry. By wearing these collars, Masons reaffirm their commitment to the principles that have guided the fraternity for centuries. The continued use of chain collars in Masonic ceremonies helps to preserve the rituals and symbols that define the organization.

A Symbol of Leadership and Responsibility

Masonic chain collars are more than just decorative items; they are symbols of leadership and responsibility within the Lodge. Each time a Mason dons their collar, they are reminded of the duties they have pledged to uphold. This sense of responsibility extends beyond the Lodge, influencing how Masons conduct themselves in their personal and professional lives.

Connecting Past, Present, and Future

The symbolism of the chain collar as a link between individual members also extends to the connection between past, present, and future generations of Masons. By preserving and passing down these symbols, Masons ensure that the teachings and values of the fraternity continue to be relevant and impactful for future generations.

Challenges and Controversies Surrounding Masonic Chain Collars

Modern Perceptions of Freemasonry

In modern times, Freemasonry has sometimes been the subject of misunderstandings and misconceptions. The use of regalia, including chain collars, can be seen as antiquated or overly secretive by those outside the fraternity. However, Masons understand that these symbols carry deep meaning and are an essential part of the rituals that bind the fraternity together.

Balancing Tradition with Modernity

As with any long-standing tradition, Freemasonry must balance the preservation of its rituals with the need to remain relevant in a changing world. While some Lodges have embraced more modern designs for their regalia, others remain committed to traditional styles. This balance ensures that the essential symbols and values of Freemasonry are preserved while allowing for adaptation and evolution.

The Cost and Accessibility of Regalia

The cost of Masonic regalia, including chain collars, can be a barrier for some members, particularly in smaller Lodges or in regions where economic conditions are challenging. However, many Lodges work to ensure that all members have access to the necessary regalia, often through shared resources or donations. This commitment to inclusivity reflects the Masonic principle of brotherhood and support for all members.

Conclusion

Masonic chain collars are more than just a part of the ceremonial attire; they are a profound symbol of the values, traditions, and responsibilities that define Freemasonry. From their historical origins to their role in modern rituals, these collars serve as a tangible link between the members of the Lodge, connecting past, present, and future generations. As Freemasonry continues to evolve, the significance of these collars remains steadfast, reminding Masons of their duty to uphold the principles of brotherhood, leadership, and moral integrity.

By understanding the rich symbolism and importance of Masonic chain collars, we gain a deeper appreciation for the rituals and traditions that have shaped Freemasonry into the organization it is today. Whether worn in private ceremonies or public displays, these collars are a testament to the enduring values of a fraternity that has stood the test of time.

0 notes

Text

During the 1290s, there were several reasons why lessons were considered pensionable for forks, particularly in England.

One of the main reasons was the widespread use of forks in dining. Forks were a relatively new utensil in Europe, and they were primarily used by the wealthy and elite members of society. As such, owning a fork was seen as a symbol of status and luxury, and it was often included in dowries and wedding gifts. This popularity of forks in dining led to an increasing demand for skilled fork-makers, who could create intricate and fashionable designs.

Additionally, the use of forks in dining was also considered more hygienic and sophisticated compared to using one’s hands or the communal knife. During this time, there was a growing awareness of the importance of cleanliness and manners in social interactions, and using a fork to eat was seen as a display of refinement and courtesy.

The demand for fork-makers and the increasing use of forks in dining led to a rise in fork-making apprenticeships and lessons. Fork-makers were highly skilled craftsmen, and they needed to pass on their knowledge and techniques to the next generation. Lessons were pensionable for forks because they were often taught within guilds or apprenticeships, where students paid a fee to learn the trade and the master craftsman would receive a portion of this fee as their retirement fund.

In addition to the financial benefits for the fork-maker, lessons were also pensionable in order to ensure the quality and consistency of fork-making. By carefully selecting and training apprentices, masters could ensure that their craft would continue to be of high quality and that they would have a reliable source of income in their retirement.

Moreover, the 1290s were a time of social and economic stability in England, with a growing wealthy merchant class and the establishment of many trade guilds. As such, there was a significant emphasis on trade and craftsmanship, and fork-making was seen as a valuable skill to pass down.

In conclusion, the popularity of forks in dining, the demand for skilled fork-makers, and the economic and social climate of the 1290s all contributed to why lessons were pensionable for forks. It was a mutually beneficial system, as it ensured the quality and continuation of the craft while also providing a retirement fund for the masters.

0 notes

Text

Echoes of the Ancient War - Lore Summary

Historical Context

Ancient War: Centuries ago, a devastating war between elves and humans erupted. The nature of its onset and conclusion remains unclear, but its aftermath was profound. The humans significantly expanded their territories. In contrast, the elves, devastated by the war, withdrew into seclusion, concealing their once-thriving cities with powerful, arcane magics that remain unseen by modern humans.

Human-Elven Relations

Conscripted Elves: After the war a tradition emerged among elite human houses to keep elven "conscripts". These descendants of captured elves are born into servitude. Trained as warriors or used as status symbols, these elves are living trophies, regulated by strict laws to ensure their loyalty.

Symbols of Power: Possessing an elven conscript is a status symbol, showcasing power and influence. These elves often serve as bodyguards, assassins, enforcers, or shown off as decorative trophies at social events.

The Human Perspective

Rarity of Sightings: Most humans have never seen an elf, free elves are almost unheard of and the conscripts are generally hidden from view kept within the grand homes of the wealthy.

Elite Privilege: For elites, owning an elven conscript signifies dominance. These elves are paraded at events, adding to the mystique and prestige of their owners.

Modern Dynamics

Human Politics: The practice of keeping elven conscripts is controversial. Some human factions advocate for their liberation, citing ethical concerns and the potential for rebellion. Others see it as necessary a tradition that should be upheald. Most citizens, however, feel detached from the issue.

Government Stance: The central government remains largely supportive of the status quo, influenced by political alliances and economic interests. While there have been some measures to address abuses, substantial change is slow.

Magic System

Magical Affinities: Mages are born with affinities for one of four magical schools: Healing and Creation, Elemental, Destruction, and Spiritual. Mastery outside one's affinity is rare.

Healing and Creation: Mending wounds, creating enchantments, etc.

Elemental: Manipulating and creating fire, water, earth, air, and lightning.

Destruction: Offensive spells and combat magic.

Spiritual: Connections to otherworldly entities, divination, etc.

Magic permeates daily life, from healing and agriculture to combat and spiritual guidance.

Other Races

Dwarves: Many dwarves have moved into human cities (mostly working as craftsmen or in the guilds) others work as traveling mercenaries, but there are also dwarven cities in the mountains that appear large and industrial to the outside world. Dwarven society is caste-based, valuing craftsmanship and tradition.

Gnomes: Gnomes are known for their curiosity and innovation, often living in secluded communities focused on technological and magical research - though sgnomes noving into human cities has been becoming more common. They are master tinkerers and inventors. Most gnomes have an affinity for creation magic, though ones with enough power to be considered "true mages" are rare.

Their societies are collaborative and emphasize education and innovation. They often create intricate mechanical devices and enchantments.

Halflings: Halflings are a peaceful, and somewhat isolated people living in close-knit communities and generally staying out of race relations and politics. They value simplicity, family, and tradition.

They are known for their hospitality and village wide celebrations/festivals. Despite being stereotypical a fairly insular society halflings are incredibly social and welcoming to any outsider who arrived at their settlements.

Orcs: Orcs are a warrior race known for their honor and traditions. They typically live in tribal societies within harsh environments and are often perceived as aggressive. Orcs prize strength, courage, and martial skill, and their relations with other races vary significantly between clans. Many orcs also exhibit an affinity for destructive magic.

Elves: Very little is known about elven culture due to their extreme reclusiveness. What is known is that all elves possess a slight elemental affinity - connected to emotions and manifesting as an innate part of their being. While elven mages do exist, their prevalence is unknown because of the elves' isolation from the broader world.

Echoes of the forgotten war posts master list

0 notes

Text

Landscape Installation Dubai

Landscape Installation Dubai

Beautify your gardens with Green Creation Landscaping Installation services in Dubai, UAE. We specialize in Landscape Design, Stonework, Tree Installation, and Maintenance. With over a decade of hands-on field experience, we offer a fresh and interesting approach to landscape design in Dubai. Our extensive experience in the field gives us the insight to create the landscape of your dreams. Green Creation expert will first meet with you to discuss the needs and wants of your outdoor space. After meeting and creating a design, we will present our ideas to you. The reward for our hard work! We love to impress our clients with our creative, unique, and artistic designs! We strive to use your thoughts and ideas and combine them with our design expertise and construction knowledge to present the best possible plan for your property. We want our clients to feel connected and invested in their green space. To achieve this, we make sure to personalize the landscape design for each of our clients, matching their personal style and spirit, and producing unique gardens of their dreams.Green Creation is a team of highly experienced, comprehensive landscaping experts who provide every aspect of landscaping including design, construction, installation, and maintenance works for residential, commercial, and public properties in Dubai, UAE.

Landscaping in Dubai

With over 14 years of extensive expertise, we are masters in bespoke design, paving, block paving, driveways, groundworks, and all other landscaping services. Green Creation strives for continuous growth and improvement, relishing any chance to explore the latest developments in landscape design and materials throughout Dubai and other emirates. We are very passionate about landscaping, and we understand the potential value added to properties and the importance our clients place on their outdoor areas. We care about our clients and we love delivering impressive, unique landscaping works that create harmonious and pleasant spaces for friends, family, and large businesses. Therefore, we hire only the best professionals in the landscaping trade.

Landscape Design Dubai

Green Creation Landscape Design specializes in creating and transforming your outdoor space, making sure we work closely to meet your needs and maximize your budget. We take pride in going the extra mile and ensuring each job is done professionally, within budget, and on schedule. Innovative landscape design for Dubai gardens, terraces, courtyards, and rooftops. We design install and maintain gardens in Dubai and all of UAE for private residences, hospitals, hotels, parks, and offices. Let us bring a touch of nature to your urban outdoor and indoor space. At Green Creation, we offer the advantage of working with one team from the conception to the completion of your project. We will guild you through the design process, plan the installation of the project, and install every detail of the design. This allows our team of designers, craftsmen, and professional gardeners the ability to work together bringing creativity, quality, and precision to all phases of your project.

Our techniques vary from others, and that's the main reason we are the leading landscaping company in Dubai, UAE. From the initial concept through to the final design and installation, we are on hand every step of the journey to ensure that we always exceed your expectations. Green Creation is a team of friendly management and staff, who always work to an affordable budget and our design team can source a wide range of materials and products to realize your project's vision. So whether you're preparing to embark on an ambitious new project or just looking to repair/renovate your existing landscape, you're in safe hands with Green Creation Landscaping.

0 notes

Text

Chapter 8: Mutual Aid Amongst Ourselves (continued)

Labour-unions grown after the destruction of the guilds by the State. — Their struggles. — Mutual Aid in strikes. — Co-operation. — Free associations for various purposes. — Self-sacrifice. — Countless societies for combined action under all possible aspects. — Mutual Aid in slum-life. — Personal aid.

When we examine the every-day life of the rural populations of Europe, we find that, notwithstanding all that has been done in modern States for the destruction of the village community, the life of the peasants remains honeycombed with habits and customs of mutual aid and support; that important vestiges of the communal possession of the soil are still retained; and that, as soon as the legal obstacles to rural association were lately removed, a network of free unions for all sorts of economical purposes rapidly spread among the peasants — the tendency of this young movement being to reconstitute some sort of union similar to the village community of old. Such being the conclusions arrived at in the preceding chapter, we have now to consider, what institutions for mutual support can be found at the present time amongst the industrial populations.

For the last three hundred years, the conditions for the growth of such institutions have been as unfavourable in the towns as they have been in the villages. It is well known, indeed, that when the medieval cities were subdued in the sixteenth century by growing military States, all institutions which kept the artisans, the masters, and the merchants together in the guilds and the cities were violently destroyed. The self-government and the self-jurisdiction of both, the guild and the city were abolished; the oath of allegiance between guild-brothers became an act of felony towards the State; the properties of the guilds were confiscated in the same way as the lands of the village communities; and the inner and technical organization of each trade was taken in hand by the State. Laws, gradually growing in severity, were passed to prevent artisans from combining in any way. For a time, some shadows of the old guilds were tolerated: merchants’ guilds were allowed to exist under the condition of freely granting subsidies to the kings, and some artisan guilds were kept in existence as organs of administration. Some of them still drag on their meaningless existence. But what formerly was the vital force of medieval life and industry has long since disappeared under the crushing weight of the centralized State.

In Great Britain, which may be taken as the best illustration of the industrial policy of the modern States, we see the Parliament beginning the destruction of the guilds as early as the fifteenth century; but it was especially in the next century that decisive measures were taken. Henry the Eighth not only ruined the organization of the guilds, but also confiscated their properties, with even less excuse and manners, as Toulmin Smith wrote, than he had produced for confiscating the estates of the monasteries.[295] Edward the Sixth completed his work,[296] and already in the second part of the sixteenth century we find the Parliament settling all the disputes between craftsmen and merchants, which formerly were settled in each city separately. The Parliament and the king not only legislated in all such contests, but, keeping in view the interests of the Crown in the exports, they soon began to determine the number of apprentices in each trade and minutely to regulate the very technics of each fabrication — the weights of the stuffs, the number of threads in the yard of cloth, and the like. With little success, it must be said; because contests and technical difficulties which were arranged for centuries in succession by agreement between closely-interdependent guilds and federated cities lay entirely beyond the powers of the centralized State. The continual interference of its officials paralyzed the trades; bringing most of them to a complete decay; and the last century economists, when they rose against the State regulation of industries, only ventilated a widely-felt discontent. The abolition of that interference by the French Revolution was greeted as an act of liberation, and the example of France was soon followed elsewhere.

With the regulation of wages the State had no better success. In the medieval cities, when the distinction between masters and apprentices or journeymen became more and more apparent in the fifteenth century, unions of apprentices (Gesellenverbände), occasionally assuming an international character, were opposed to the unions of masters and merchants. Now it was the State which undertook to settle their griefs, and under the Elizabethan Statute of 1563 the Justices of Peace had to settle the wages, so as to guarantee a “convenient” livelihood to journeymen and apprentices. The Justices, however, proved helpless to conciliate the conflicting interests, and still less to compel the masters to obey their decisions. The law gradually became a dead letter, and was repealed by the end of the eighteenth century. But while the State thus abandoned the function of regulating wages, it continued severely to prohibit all combinations which were entered upon by journeymen and workers in order to raise their wages, or to keep them at a certain level. All through the eighteenth century it legislated against the workers’ unions, and in 1799 it finally prohibited all sorts of combinations, under the menace of severe punishments. In fact, the British Parliament only followed in this case the example of the French Revolutionary Convention, which had issued a draconic law against coalitions of workers-coalitions between a number of citizens being considered as attempts against the sovereignty of the State, which was supposed equally to protect all its subjects. The work of destruction of the medieval unions was thus completed. Both in the town and in the village the State reigned over loose aggregations of individuals, and was ready to prevent by the most stringent measures the reconstitution of any sort of separate unions among them. These were, then, the conditions under which the mutual-aid tendency had to make its way in the nineteenth century.